1. Introduction

Accurate and real-time temperature monitoring of gain media is crucial for stable and efficient laser operation [

1,

2,

3]. Temperature fluctuations inside laser crystals can lead to thermal lensing, wavelength shifts, and reduced laser efficiency or even damage to the crystal [

4,

5,

6]. While conventional thermal measurement techniques involve direct contact sensors or thermal cameras, such methods may not accurately reflect the internal temperature of the active region, especially during lasing operation. Optical thermometry, particularly based on the temperature-dependent fluorescence spectra, offers a non-invasive alternative [

7,

8].

Among various gain materials, chromium-doped fluoride crystals such as Cr:LiCAF have attracted interest due to their broad tunability and potential use in ultrafast and visible laser sources [

9,

10]. However, there exists a noticeable gap in the literature when it comes to temperature-dependent fluorescence studies of Cr:LiCAF, especially under continuous-wave (CW) lasing conditions. This study focuses on the development and implementation of a contactless optical temperature estimation method based on fluorescence peak shifts in Cr:LiCAF crystals.

Optical thermometry techniques have been widely employed for non-contact temperature measurements in laser systems. These techniques rely on temperature-induced spectral changes such as peak shifts, bandwidth broadening, intensity ratios, and lifetime variations to infer the thermal state of laser materials [

11,

12,

13]. The peak shift method is particularly favored for its simplicity and direct correlation with lattice vibrations and phonon interactions [

14]. Although thermal cameras provide surface temperature information, they lack precision in detecting subsurface crystal heating during lasing. Therefore, combining optical thermometry with thermal imaging enables a more reliable temperature assessment by correlating internal fluorescence shifts with external temperature distributions.

Laser crystals such as Yb:YAG [

15], Yb:YLF [

16], and Nd:YVO4 [

17] have been extensively studied under varying thermal loads. Demirbas et al. [

18,

19] systematically compared different optical thermometry techniques for cryogenic Yb:YAG and Yb:YLF crystals and demonstrated that spectral-based temperature probing can achieve sub-degree accuracy under controlled conditions, while also identifying major sources of uncertainty such as spectral noise and detector stability. Sui et al. [

20] showed that precise thermal monitoring is crucial for preventing performance degradation in high-energy cryogenically cooled Yb:YAG laser systems. Püschel et al. [

21] investigated the influence of rare-earth doping on thermal effects in Yb:YLF and demonstrated how temperature gradients directly affect laser cooling efficiency. These studies collectively emphasize that reliable temperature diagnostics are essential for both performance optimization and long-term operational stability of solid-state laser systems. In the case of chromium-doped gain media, studies have largely focused on Cr:LiSAF, Cr:LiSGaF, and to a limited extent Cr:LiCAF [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Okuyucu et al. [

26] recently provided a comparative temperature-dependent study of emission cross-sections in these fluoride crystals. However, these studies mostly consider passive heating or cryogenic operation, lacking real-time feedback from actively lasing media.

Recent advances in spectrometer design and data acquisition systems have enabled high-resolution spectral tracking at sub-degree thermal steps [

27]. Integrated setups with thermal cameras and synchronized excitation sources have also improved the calibration reliability [

28]. Machine learning-based thermometry models are also emerging, offering improved robustness against noise and positional drift [

29]. While the temperature dependence of fluorescence peak shifts in laser crystals is a well-established phenomenon, prior studies have predominantly focused on conventional gain media such as Yb:YAG or Nd:YVO

4, often under pulsed or static thermal conditions. In contrast, the behavior of Cr:LiCAF under active, diode-pumped continuous-wave (CW) operation remains underexplored. This work contributes to the literature by introducing a systematic, high-resolution calibration protocol specifically tailored for Cr:LiCAF, implemented under both lasing and non-lasing conditions. A fine-step thermal sweep (10–100 °C, 181 data points) and corresponding fluorescence shifts were modeled via linear regression, revealing a robust and quantifiable temperature–emission relationship. Furthermore, experimental validation was achieved through synchronized thermal imaging using a calibrated FLIR E75 camera. By comparing the internal temperatures inferred from spectral data with external surface readings, we demonstrate the consistency and accuracy of the proposed optical thermometry technique. This hybrid approach not only enhances the reliability of contactless diagnostics but also fills a practical and methodological gap in the application of real-time, non-invasive thermal monitoring for Cr-doped fluoride laser systems. The dual-condition design and cross-verification strategy collectively represent a novel and applicable framework for future laser diagnostics and system integration.

The paper is organized as follows. The Introduction provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature on optical thermometry techniques and prior work involving Cr-doped fluoride crystals. The Experimental Setup section describes the instrumentation and methodology used to perform fluorescence calibration of Cr:LiCAF crystals under controlled thermal conditions. The Experimental Results section presents emission measurements under both lasing and non-lasing regimes and includes spectral shift analysis to evaluate temperature sensitivity. Finally, the Discussion and Conclusion summarize the key findings and discuss their implications for real-time optical diagnostics and thermal feedback in diode-pumped laser systems.

2. Experimental Setup

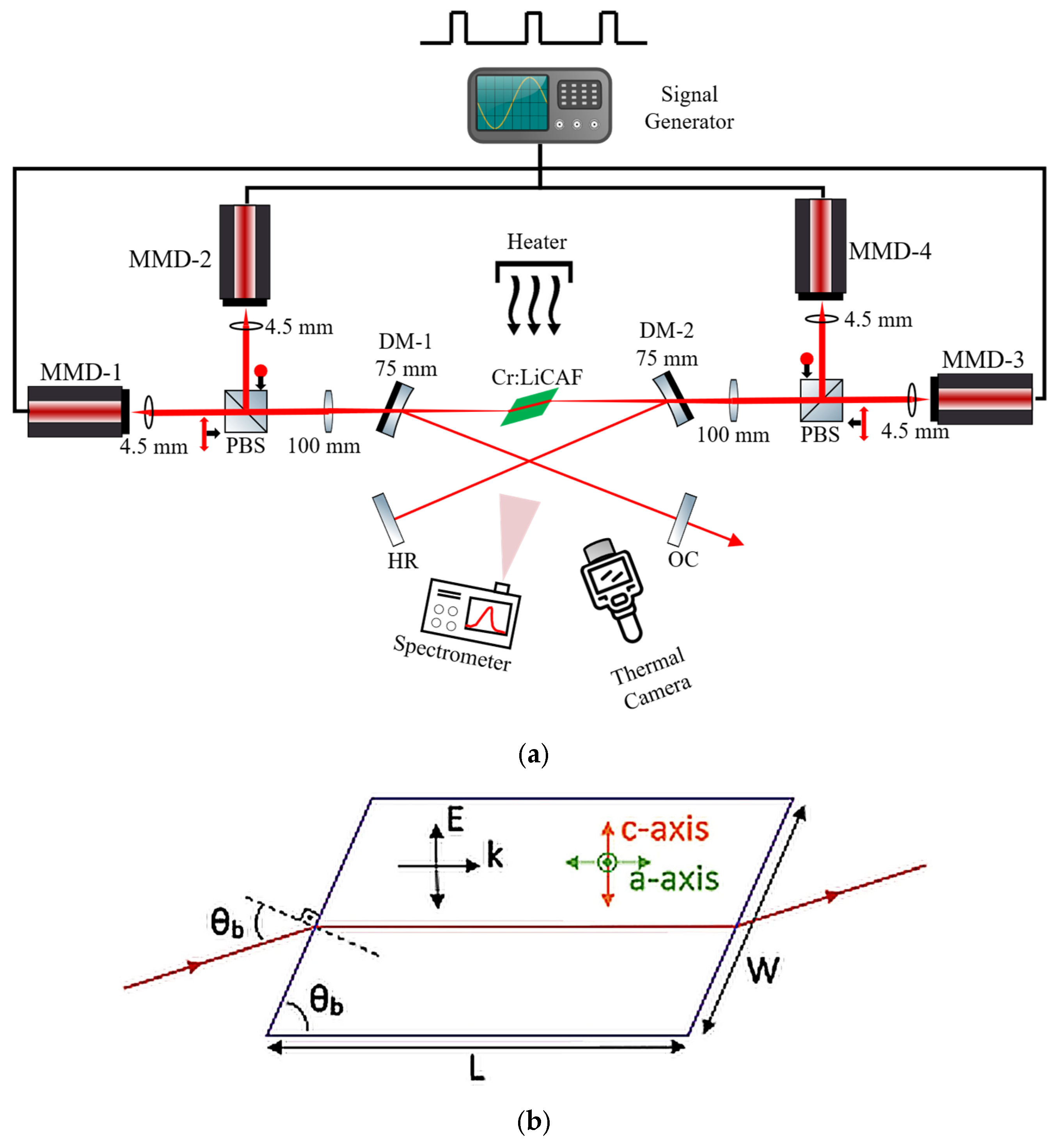

To estimate the temperature inside the gain medium, we employed a standard X-folded cavity setup with both optical and thermal diagnostics as shown in

Figure 1. A Cr:LiCAF crystal (1.25% Cr-doped, 15 × 7 × 2 mm

3) was mounted in a water-cooled copper holder stabilized at 15 °C. Four 660 nm multimode laser diodes (MMD-1 to MMD-4) were used as pump sources. Each diode output was first collimated using 4.5 mm focal-length aspheric collimation lenses. The pump beams were then combined by means of polarizing beam splitters (PBSs) and subsequently focused into the crystal using achromatic doublet lenses with a focal length of 100 mm, resulting in an approximately 25 × 65 µm pump spot size at the crystal. Two dichroic cavity mirrors (DM-1 and DM-2), highly transmissive at the pump wavelength (660 nm) and highly reflective around the laser emission wavelength (~800 nm), were used to separate the pump radiation from the resonator mode and to fold the cavity arms. The optical cavity further included a high-reflector mirror (HR) and an output coupler (OC) to guide and extract the laser radiation along the folded resonator geometry during alignment and diagnostic measurements. The pump diodes were operated in pulsed mode (1 Hz repetition rate, 10 ms pulse duration) to generate a peak pump power of 1.7 W while minimizing thermal loading during calibration procedures. Fluorescence emission spectra were collected using an Ocean Optics HR4000 spectrometer (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) with a spectral resolution of 0.25 nm. The spectrometer position was carefully optimized to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio and minimize geometric distortion. The crystal temperature was increased in 0.5 °C increments using a controllable heat blower, while real-time temperature monitoring was performed simultaneously with a FLIR E75 thermal camera (Wilsonville, OR, USA) and an additional thermal sensor mounted directly on the copper holder. In addition to spectrometer-based emission analysis, thermal images were captured at various diode current levels (0 A, 1.5 A, 2.0 A, and 2.5 A) to compare surface temperature variations with internal temperature predictions. Each measurement was performed after thermal stabilization to ensure accurate correlation between the spectral data and thermal camera output. Calibration data were acquired across 181 temperature points between 10 and 100 °C.

The Cr:LiCAF crystal was Brewster–Brewster cut and mounted such that the laser beam propagated along the a-axis of the crystal. The polarization of the propagating light was TM polarized with the electric field vector parallel to the crystallographic c-axis (E//c), as illustrated in

Figure 1b. This orientation ensures maximum pump absorption and efficient fluorescence collection. To assess measurement reliability, the thermal imaging protocol included acquisition of three independent images at each diode current level after thermal stabilization. The region of interest (ROI) was defined as a centered area on the crystal surface corresponding to the pump spot location, and temperature values were averaged within this region to minimize edge effects and thermal gradients. The standard deviation across repeated measurements was consistently below ±0.3 °C, confirming the stability of the thermal imaging methodology.

For spectral measurements, the primary focus was on establishing a comprehensive calibration dataset across a wide temperature range. The spectrometer resolution of 0.25 nm and the calibration slope derived from linear regression (approximately 0.20 nm/°C) suggest a peak detection uncertainty on the order of ±0.5–1 °C. This is consistent with the observed agreement between optical temperature estimates and thermal camera measurements, where deviations remained within ±1.5 °C across all validation points.

After collecting temperature-dependent emission data, a calibration curve was constructed based on the emission peak shifts. Subsequently, the system was operated in continuous-wave (CW) lasing and non-lasing conditions for validation. During lasing, diode currents were incremented, and corresponding emission spectra were recorded. To minimize parasitic oscillations around 790 nm, stringent spectral-filtering measures were implemented. The temperature-induced emission peak shifts were then systematically evaluated under both lasing and non-lasing conditions to elucidate the influence of thermal loading on the spectral response. Observed changes in emission intensity and peak wavelength were used to estimate the internal temperature of the gain crystal under operational conditions.

3. Results

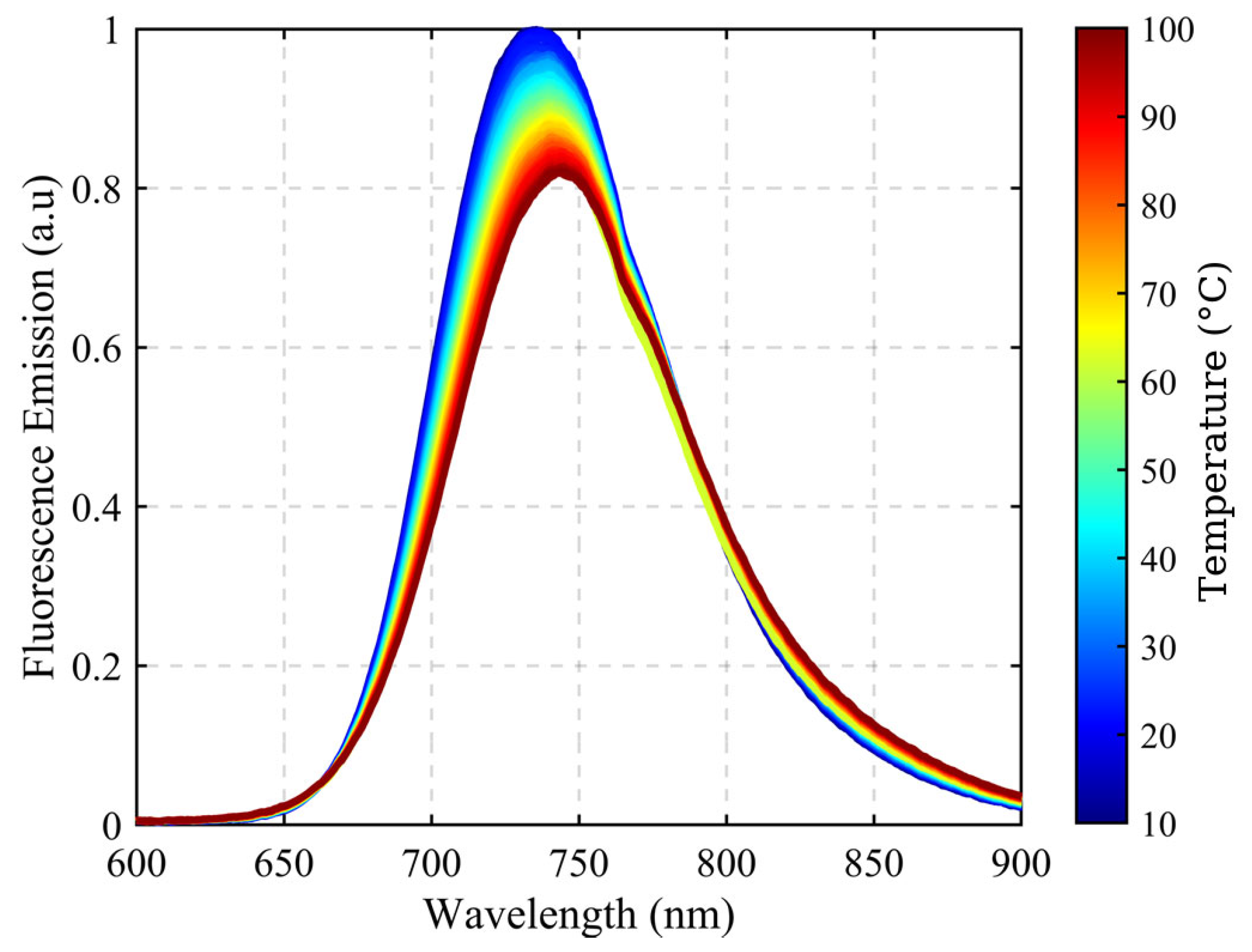

Figure 2 shows the measured emission spectrum of Cr:LiCAF at the temperature between 10 and 100 °C in normalized units. The collected emission data shows that Cr:LiCAF crystal has an emission peak around 740 nm. It is clearly observed that with the upraised temperature on the crystal, the emission lines broaden and shift near the peak due to increased phonon interactions. The blue lines indicate fluorescence emission at 10 °C and the central wavelength of around 730 nm, while the red curves represent crystal temperatures above 90 °C. The central wavelength shift between 90 °C is clearly seen. Moreover, this results in the expected intensity decrease. Building on previous studies, we constructed a reference curve for temperature estimation [

18]. The spectral change caused by the temperature change is the best option for this purpose. There are different reported techniques based on this change (Peak method, FWHM method, differential luminescence thermometry (DLT), dip method) [

19]. This study is focused especially on the peak method, where the emission peak is shifted because of temperature change. A weak secondary emission band at 760–765 nm is also observed in the spectra, which originates from higher-order vibronic transitions of the Cr

3+ ions. However, this band remains significantly weaker than the dominant fluorescence peak centered near 740 nm. In the peak extraction procedure, a constrained single-peak fitting algorithm was applied only to the dominant 740 nm band, and the influence of the secondary band on the extracted peak position was verified to be negligible within the spectral resolution of the system.

In this method we have used, emission peaks around 740 nm for Cr:LiCAF crystal, with a variation in the temperature change each emission peak extracted.

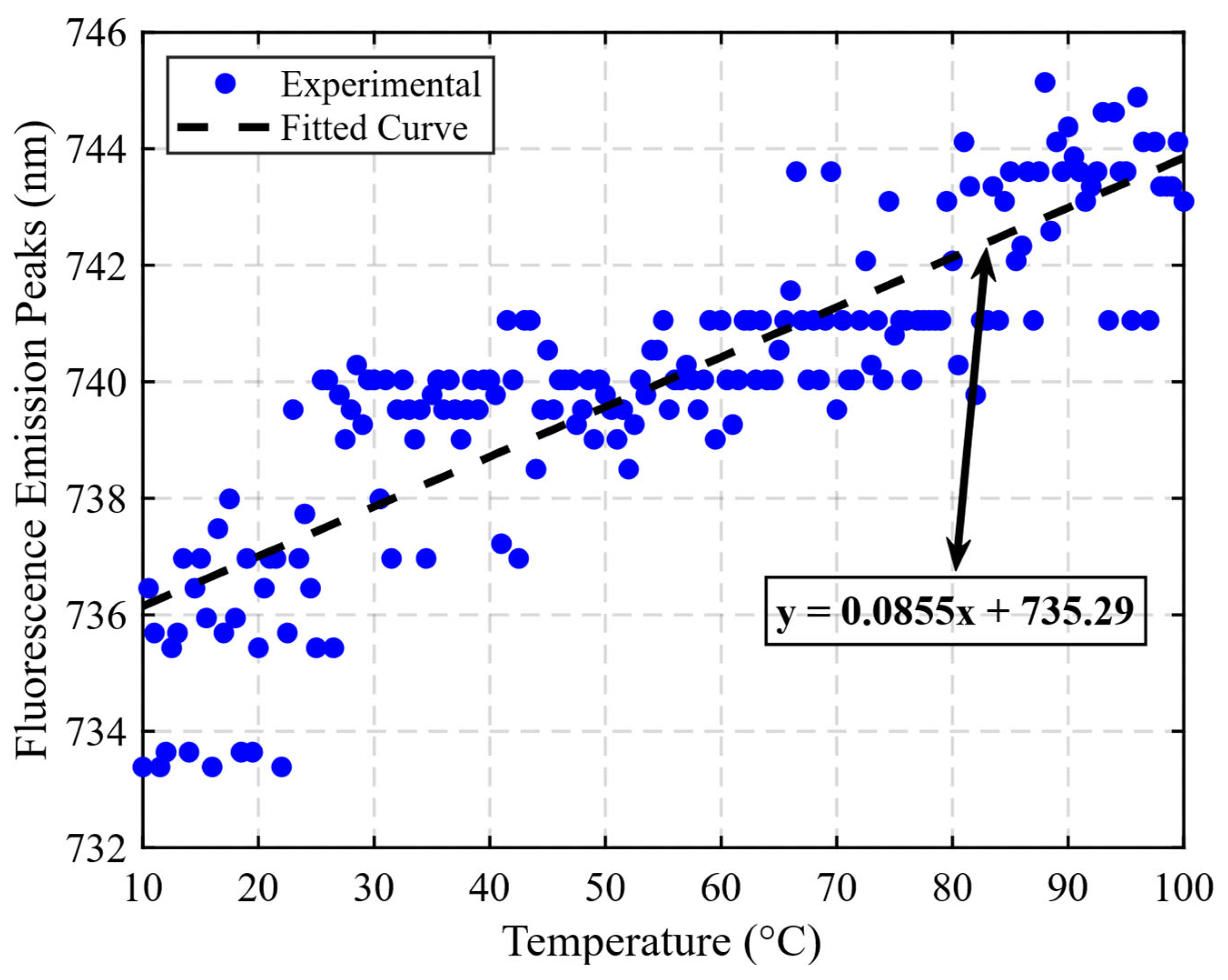

Figure 3 shows the extracted emission peaks from the reference emission curves. In here we have 181 data points, relating the increments of temperature as a step of 0.5 °C between 10 and 100 °C. Some emission peaks are identical in multiple data points due to minimal temperature differences. However, it is clear that, with an increased temperature, the emission peak transitions into higher wavelength observed. For the temperature estimation the linear regression model was implemented. A linear curve fit was plotted based on the distribution of emission peaks. The

of the linear curve for this dataset is around 0.73, which shows good agreement for the temperature estimation model.

Although the coefficient of determination ( = 0.73) is slightly below the ideal threshold for a purely statistical prediction model, this limitation mainly originates from the finite spectral resolution of the spectrometer (0.25 nm), small temperature stabilization fluctuations, and the presence of weak overlapping emission components. Importantly, the practical accuracy of the model was independently validated through thermal camera measurements, yielding a much higher agreement ( = 0.993 and MAE = 0.775 °C). Therefore, despite the moderate R2 value of the calibration fit, the model demonstrates high practical reliability for internal temperature estimation under real operating conditions.

The stability of the data acquisition system is critical for consistent spectral measurements. During measurements, all optical components must remain stable. Even small shifts in spectrometer position may alter the collected data. This can be easily understood from the intensity ratio change. When it got closer to the spectrometer, there were changes observed. Here, we would like to mention that some of the collected data curves have the same emission peaks. This can be seen in two distinct intervals, Where the temperature of the crystal is between 30 and 70 °C and where it is between 60 and 90 °C. This is possibly caused by small changes in temperature. When we look at the emission cross-sections within a smaller temperature change, this slight change in peak positions could be expected [

26]. The observed scatter of several data points around the linear fit is mainly attributed to the combined effects of spectrometer resolution limits, temperature stabilization fluctuations at small thermal steps (0.5 °C), and the influence of weak overlapping emission components. Nevertheless, the overall monotonic trend of the peak shift with temperature remains clearly preserved, validating the applicability of the linear approximation within the investigated temperature range.

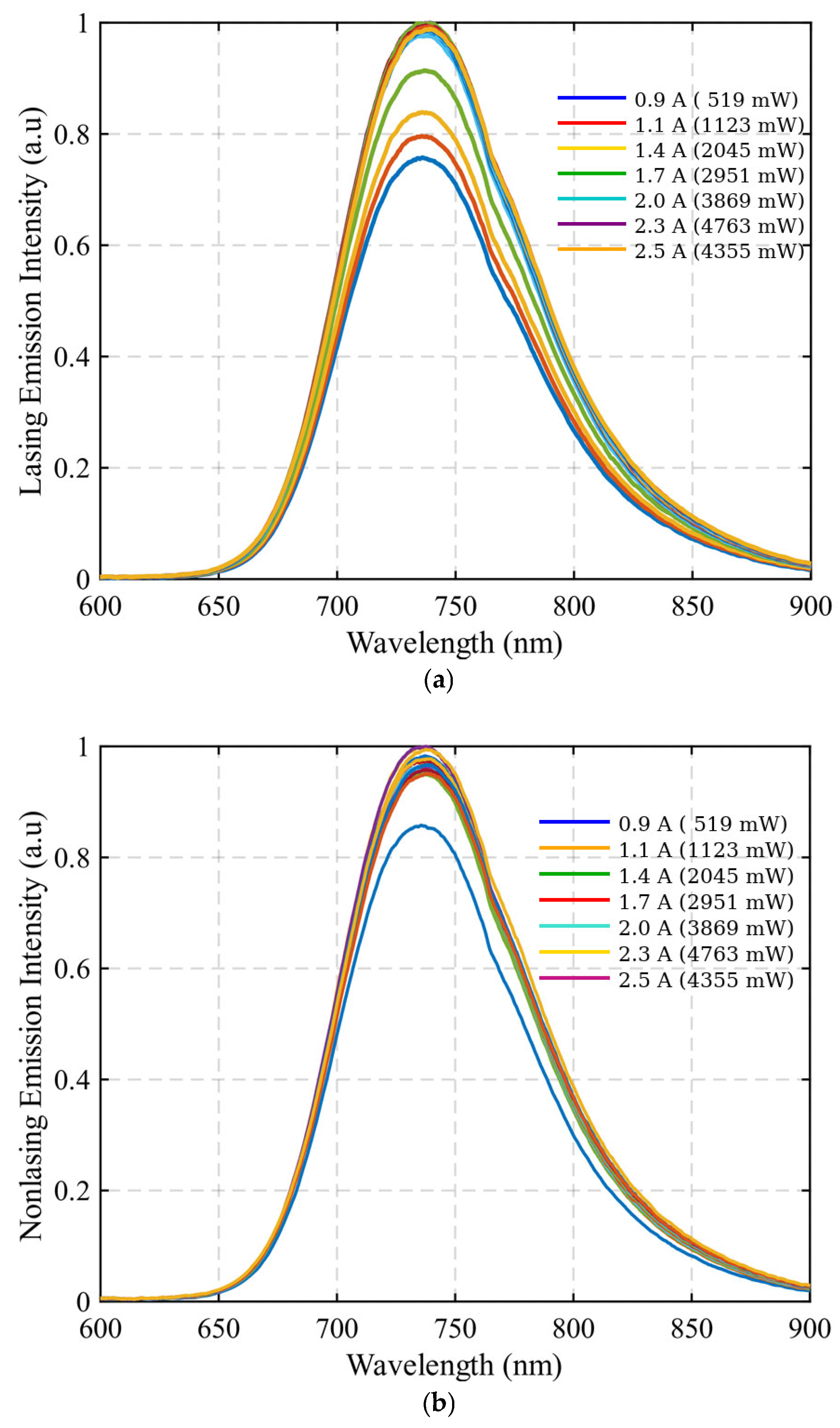

As a next step, to perform the temperature measurements from the reference curve, we have employed two different conditions. In the first part, using the same setup and operating conditions, the system was configured to operate under lasing conditions. The temperature of the crystal holder is set to 15 °C to not damage crystal. While the cavity is in continuous-wave lasing, emissions data with respect to diode currents is collected. The obtained curves are prepared for the peak extraction with post-processing. Note that, during cw lasing the peak emission collected from the lasing region of Cr:LiCAF is 800 nm. To be more precise, we removed the monochromatic lasing component through spectral post-processing. During measurements, the four diodes of the cavity are actively used to maximize the thermal load within the limitations of our laboratory setup.

Figure 4 shows the measured emission spectrum of Cr:LiCAF while active lasing creates additional thermal effects. In other cases, we have blocked the output coupling to prevent the lasing. For both cases, to estimate the temperature inside the crystal, the same method is employed. For all spectra shown in

Figure 4, the Cr:LiCAF crystal was mounted in a temperature-stabilized copper holder at 15 °C. The diode current was varied at 0.9, 1.1, 1.4, 1.7, 2.0, 2.3, and 2.5 A, corresponding to incident pump powers of 519 mW, 1123 mW, 2045 mW, 2952 mW, 3869 mW, 4763 mW, and 5355 mW, respectively. These operating points were used to induce controlled thermal loading under both lasing and non-lasing conditions.

The peak positions of the emission curves were extracted. Moreover, when we look at the intensity ratio of the emission curves for each case, there is a different scenario. During lasing, the fluorescence intensity increases due to higher pump power. This is expected because the increase in the incident power affects the emission strength. However, for the non-lasing case, since there is an active photon, this starts the transition for lasing and the general emission intensity is almost the same.

Figure 5a shows the emission peaks for the lasing case and

Figure 5b gives non-lasing emission peaks. As can be seen from the figure, the lasing peaks varied with respect to applied diode current. The increase in the current provides much more power to the laser crystal. In this way, even small changes in the emission peak positions became observable.

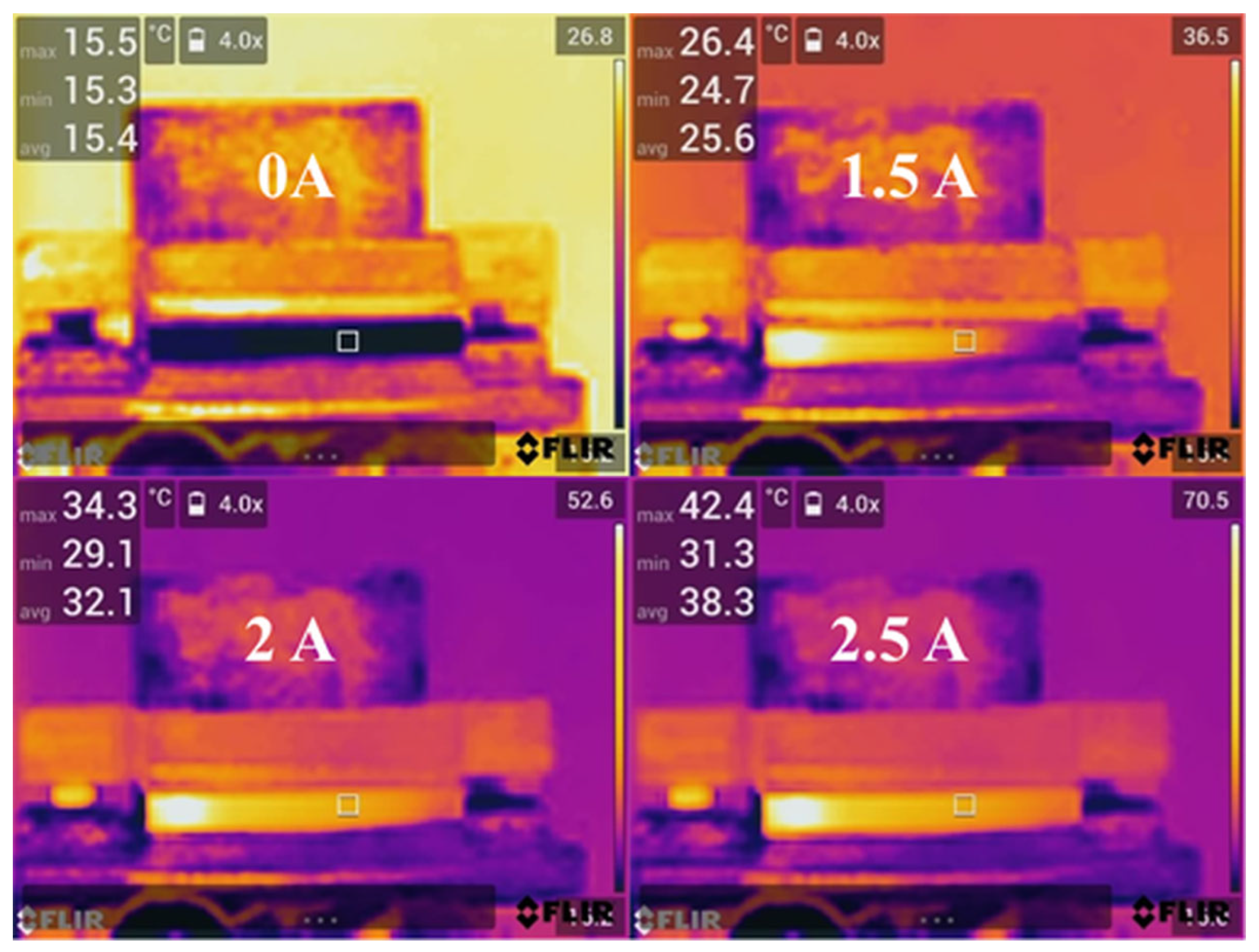

To validate the temperature estimation model derived from fluorescence peak shifts, we conducted complementary measurements using a FLIR E75 infrared thermal camera (thermal sensitivity < 0.05 °C, accuracy ± 2 °C). Thermal images were acquired at four diode current levels (0 A, 1.5 A, 2.0 A, and 2.5 A), with each condition allowed to reach thermal equilibrium before recording. Emissivity was calibrated at ε = 0.95 for the Cr:LiCAF crystal to ensure accuracy. The camera was aligned perpendicular to the crystal surface, and environmental conditions were monitored to minimize background noise and reflections. As shown in

Figure 6, a white box was defined as the region of interest (ROI), centered on the pumped area of the crystal where the maximum thermal load occurs due to direct optical excitation. This ROI was deliberately selected to represent the most thermally stressed region of the crystal. Averaging the temperature values within this ROI ensured the minimization of peripheral cooling effects and enhanced measurement stability. Although thermal gradients exist across the crystal, this central region provides the most consistent and relevant feedback under diode-pumped excitation. To ensure repeatability measurement, three independent thermal images were acquired under each operating condition. The observed standard deviation in temperature within the ROI was consistently below ±0.3 °C, confirming the robustness of the measurement protocol. The resulting values are summarized in

Table 1. These operating points represent increasing thermal loads inside the crystal, simulating the temperature rise during continuous-wave lasing and validating the accuracy of the contactless spectroscopic thermometry approach.

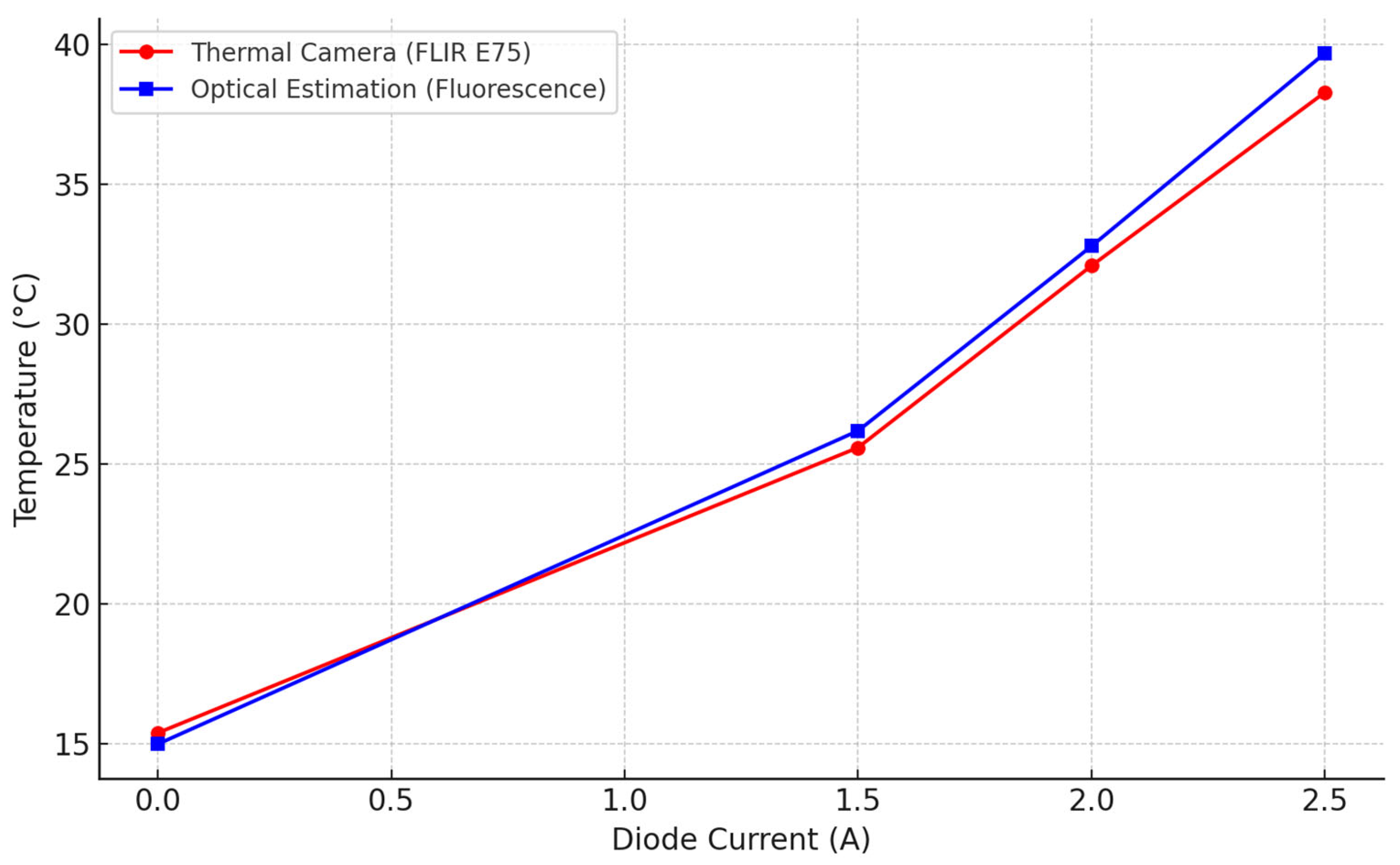

Simultaneously, the fluorescence emission spectra were collected for each current level, and the peak wavelengths were extracted. The corresponding optical temperature estimations showed strong agreement with the thermal camera results, with deviations within ±1.5 °C across all measurement points. For instance, at 2.5 A diode current, the spectral shift suggested an internal crystal temperature of ~39.7 °C, closely matching the 38.3 °C measured externally.

To quantify the agreement between the internal temperatures estimated via fluorescence peak shifts and those measured by the FLIR E75 thermal camera, a mean absolute error (

) analysis was conducted [

30]. The resulting

value was 0.775 °C, with a maximum deviation of 1.4 °C observed at the highest current setting (2.5 A). Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (

R2) between the two datasets was calculated to be 0.993, indicating an excellent linear correlation. These results confirm that the optical thermometry method provides reliable estimates of internal crystal temperature, closely matching the surface readings of infrared thermography.

is simply calculated as Equation (1):

The coefficient of determination (

) is given by Equation (2):

Here, is the internal temperature estimated from fluorescence peak shifts, is the corresponding surface temperature measured by the thermal camera, and n is the total number of measurement points.

Figure 7 illustrates the comparison between temperature values measured via a FLIR E75 thermal camera and those estimated through fluorescence peak shifts in Cr:LiCAF crystals at various diode current levels. As the current increases, both measurement methods consistently show a rise in temperature. The close alignment of the two datasets, with deviations remaining within ±1.5 °C, confirms the accuracy and reliability of the spectrometer-based optical thermometry method. This agreement highlights the feasibility of using fluorescence peak shifts for real-time, non-invasive internal temperature monitoring in diode-pumped solid-state laser systems.