Abstract

This paper addresses the challenge of optimizing cloudlet resource allocation in a code evaluation system. The study models the relationship between system load and response time when users submit code to an online code-evaluation platform, LambdaChecker, which operates a cloudlet-based processing pipeline. The pipeline includes code correctness checks, static analysis, and design-pattern detection using a local Large Language Model (LLM). To optimize the system, we develop a mathematical model and apply it to the LambdaChecker resource management problem. The proposed approach is evaluated using both simulations and real contest data, with a focus on improvements in average response time, resource utilization efficiency, and user satisfaction. The results indicate that adaptive scheduling and workload prediction effectively reduce waiting times without substantially increasing operational costs. Overall, the study suggests that systematic cloudlet optimization can enhance the educational value of automated code evaluation systems by improving responsiveness while preserving sustainable resource usage.

1. Introduction

Writing maintainable, high-quality code and receiving prompt, clear feedback significantly enhance learning outcomes [1] in computer science education. As students develop programming skills, rapid, reliable evaluation helps reinforce good practices, correct misconceptions early, and maintain engagement—especially in campus-wide online judge systems. Similarly, in the software industry, timely code review and automated testing play crucial roles in ensuring code quality, reducing defects, and accelerating development cycles, underscoring the importance of feedback-driven workflows in both education and professional practice.

This paper presents optimization strategies for managing cloudlet resources of LambdaChecker, an online code evaluation system developed at the National University of Science and Technology Politehnica Bucharest. The system was designed to enhance both teaching and learning in programming-focused courses such as Data Structures and Algorithms and Object-Oriented Programming. It does this by supporting hands-on activities, laboratory sessions, examinations, and programming contests. A key advantage of LambdaChecker is its extensibility, which enables the integration of custom features tailored to specific exam formats and project requirements. Moreover, the platform facilitates the collection of coding-related metrics, including the detection of pasted code fragments, the recording of job timestamps, and the measurement of the average time required to solve a task.

In its current implementation, LambdaChecker assesses code correctness through input/output testing and evaluates code quality [2] using PMD [3], an open-source static code analysis tool. PMD, which is also integrated into widely used platforms such as SonarQube, provides a set of carefully selected object-oriented programming metrics. These metrics are sufficiently simple to be applied effectively in an educational context while still aligning with industry standards.

In our previous work [4], building on earlier studies [5,6], we extended LambdaChecker to include support for design pattern detection using Generative AI (GenAI). We have used the LLaMA 3.1 model [7] (70.6B parameters, Q4_0 quantization) to detect design patterns in the submitted user’s code. This functionality has proven particularly valuable for teaching assistants during the grading process, as it facilitates the assessment of higher-level software design principles beyond code correctness and quality. This integration leverages GenAI models to enhance the reliability of automated feedback while reducing the grading workload. Nonetheless, this advancement is associated with higher resource requirements and increased latency in code evaluation systems without optimization.

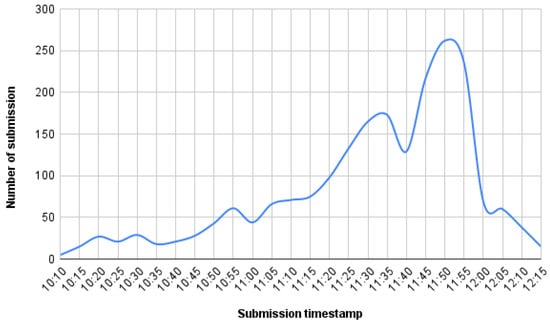

During a contest, the workload on our system differs significantly from regular semester activity, exhibiting a sharp increase in submission rates. While day-to-day usage remains relatively irregular and influenced by teaching assistants’ instructional styles, content periods generate highly concentrated bursts of activity. The submission rate rises steadily as users progress with their tasks, culminating in peak workloads (e.g., the peak in Figure 1, approximately 54 submissions per minute) during the contest. Such intense demand places substantial pressure on computational and storage resources, making it essential to optimize resource allocation. Without efficient resource management, the platform risks performance degradation or downtime precisely when reliability is most critical. Consequently, adapting the system’s infrastructure to match workload patterns dynamically ensures both cost-effectiveness during low-activity periods and robustness during high-stakes contest scenarios.

Figure 1.

Frequency of submissions in 5 min intervals during the OOP practical examination.

To address the resource inefficiencies observed in the previous version of LambdaChecker with LLM-based design pattern detection [4], we employed optimization strategies to manage computational resources within the cloudlet. Our main contributions are:

- Mathematical modeling of resource allocation: We develop a model for dynamically allocating computational resources to ensure stable performance during contests and regular lab activities.

- Simulation-based validation: We evaluate the model under high submission rates using real contest data, demonstrating reduced latency, improved throughput, and enhanced stability while remaining cost-effective.

- Integration with LLM-assisted feedback: We demonstrate that LLM-powered design pattern detection can coexist with optimized resource management without compromising responsiveness.

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work in the field, while Section 3 describes the cluster, the LambdaChecker system, and the mathematical model and optimization techniques. Section 4 applies the mathematical model in a case study—LambdaChecker during a contest. Section 5 contains the discussion and user experience implications, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Automated code evaluation systems, commonly known as online judges (OJs), play a central role in both competitive programming and computer science education. Early research demonstrated the feasibility of cloud-based architectures for scalable OJ platforms, enabling the simultaneous evaluation of many user submissions [8]. Subsequent work leveraged container-based sandboxing to improve isolation and resource efficiency, allowing platforms to handle the bursty workloads typical of exams and practical assignments [9]. Surveys of automated feedback systems in education further emphasize the importance of combining correctness checking, static analysis, and pedagogically meaningful feedback to enhance learning outcomes [10,11]. These studies establish the foundational need for efficient, responsive evaluation pipelines, particularly in time-constrained assessment scenarios.

Cloudlet and edge computing approaches have been proposed to improve responsiveness and resource utilization in latency-sensitive applications. Task offloading and collaborative edge–cloud scheduling strategies demonstrate that local compute layers can significantly reduce response times while balancing load across distributed infrastructure [12]. Surveys of edge networks further highlight how the convergence of computation, caching, and communication improves performance under highly variable workloads [13]. To handle fluctuating demand, both classical and modern auto-scaling strategies have been studied, ranging from hybrid cloud auto-scaling techniques aimed at cost-performance tradeoffs [14] to reinforcement-learning-based adaptive scheduling [15]. These insights inform the design of short-, medium-, and long-term scheduling strategies for cloudlet-based code evaluation systems, such as the one presented in this study.

Analytical performance modeling continues to provide guidance for managing high-volume workloads in interactive and multi-tier systems. Recent efforts have extended classical queueing and simulation-based modeling to modern microservice or cloud-native platforms. For example, PerfSim: A Performance Simulator for Cloud Native Microservice Chains offers a discrete-event simulation tool that, given traces of microservice behavior, can simulate entire service chains and predict key metrics such as average response times under different resource allocation policies [16]. Similarly, a performance modeling framework for microservices-based cloud infrastructures proposes a comprehensive model tailored to microservice-based cloud systems that supports capacity planning and resource provisioning decisions under realistic deployment conditions [17]. Moreover, acknowledging non-stationarity in arrival and service patterns, performance modeling of cloud systems by an infinite-server queue operating in a rarely changing random environment uses queueing theory with a random-environment extension to reflect dynamic workload fluctuations [18]. These modern approaches support the use of queueing-based simulations, microservice-aware modeling, and stochastic workload modeling as essential tools for optimizing cloudlet behavior in automated code evaluation pipelines.

Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have enabled novel forms of automated code analysis and feedback. Generative AI models have been used to assess code quality, detect design patterns, and provide higher-level feedback beyond simple correctness checks [5]. Evaluations of code-oriented LLMs demonstrate their ability to classify, analyze, and predict defects across various programming languages and tasks [6]. Integrating a local LLM into a cloudlet-based evaluation pipeline allows for richer analysis—such as design-pattern detection—without sacrificing latency or data privacy, complementing traditional static analysis tools like PMD.

Quick, targeted feedback can significantly help students learn to code. Adaptive feedback that addresses specific errors allows beginners to correct mistakes more efficiently and supports iterative problem-solving [19]. Research shows that automated feedback improves performance on assignments, particularly for more complex problems, though its benefits may be less pronounced when feedback is no longer provided. In line with this, the implementation of Quick Check questions and increased exam proctoring provides more immediate feedback and structured engagement opportunities. These shorter feedback cycles appear to enhance learning by promoting consistent interaction with course materials, improving performance on application-based questions, and fostering deeper cognitive processing [20]. This highlights that optimizing response times in online code evaluation systems is not just a matter of technical efficiency—providing faster and more consistent feedback directly supports learning. It creates a more effective and engaging user experience.

Govea et al. [21] explore how artificial intelligence and cloud computing can be integrated to improve the scalability and performance of educational platforms. Their work highlights strategies for efficient management of computational resources under high user loads, providing insights directly relevant to optimizing cloud utilization in student code evaluation systems. However, their approach is more general, targeting educational platforms broadly rather than focusing specifically on code evaluation. As a result, it lacks tailored mechanisms for handling programming assignments, such as automated testing, code similarity detection, or fine-grained feedback, which are central to dedicated student code evaluation systems.

Kim et al. [22] present Watcher, a cloud-based platform for monitoring and evaluating student programming activities. The system emphasizes isolation and convenience, providing each student with an independent virtual machine to prevent interference and ensure secure execution of assignments. By capturing detailed coding activity logs and enabling instructors to analyze potential cheating or errors, Watcher demonstrates how cloud-based infrastructure can support fair, scalable, and secure student code evaluation. Nevertheless, relying on dedicated virtual machines for each student can lead to higher resource usage and operational costs, potentially constraining scalability in large classes or institutions with limited cloud budgets. Furthermore, this system does not account for the substantial resource requirements of LLM-based evaluation.

Queueing-theory models developed for fog computing provide valuable insights for managing low-latency, distributed resources similar to cloudlets. For example, a recent study presents a queuing model for fog nodes that captures task arrival rates, service times, and resource contention to predict system performance under dynamic workloads [23]. Although their focus is on IoT and general edge applications, the principles directly apply to cloudlet-based code-evaluation systems, where jobs from multiple users must be processed efficiently while minimizing feedback latency. Incorporating such analytical models enables us to reason about throughput, average response times, and system utilization, which form the basis for our optimization of job scheduling and resource allocation in a sequential, multi-user environment.

While each of these studies provides valuable insights, none fully addresses the combined challenges of sequential job evaluation, fine-grained feedback, and cost-effective cloud utilization in the context of real-time LLM-based code evaluation systems. Our work builds on these foundations by developing a tailored mathematical model for load and response time, specifically designed for user code evaluation, estimated workload, and by analyzing optimization strategies that balance performance, cost, and user performance outcomes. This positions our approach as a bridge between theoretical cloud optimization, practical monitoring systems, and pedagogically meaningful evaluation.

3. Materials and Methods

In the initial iterations of the system, we observed the critical role played by platform performance and students’ sensitivity to the overhead introduced by the tooling. When integrating the LLM and PMD components, our primary concern was to avoid increasing feedback time. This constraint directly influenced the choice and applicability of the proposed model to the LambdaChecker data, as it reflects real-world performance requirements observed empirically during early deployments.

3.1. Cluster Setup, LLM-Based Code Evaluation Tool

Owing to limited computational resources, we initially assigned all submission-processing tasks for the LambdaChecker scheduler to a dedicated compute node. This node is equipped with Intel® Xeon® E5-2640 v3 multicore processor two NVIDIA H100 GPUs with 80 GB of HBM3 memory each, providing substantial memory capacity and computational power. This setup is ideal for large-scale models; for instance, a pair of these GPUs can efficiently run a 70B-parameter model like LLaMA 3.1 while maintaining high performance and optimized memory usage.

The machine supports the entire evaluation pipeline, handling CPU-intensive tasks such as PMD static analysis and correctness testing, as well as GPU-accelerated design-pattern detection workloads. Each step increases the load on the evaluation system, with LLM-based design pattern detection being the most resource-intensive, consuming up to 70% of the total average evaluation time.

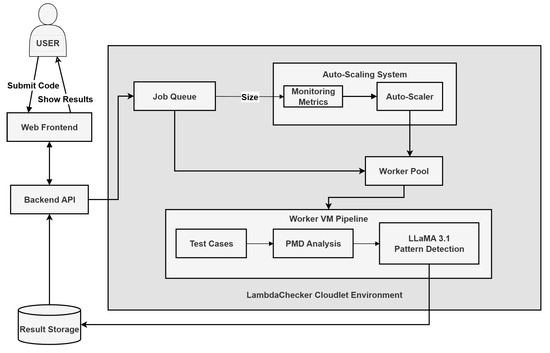

Figure 2 presents the architecture of the LambdaChecker queue-driven code evaluation system deployed within the cloudlet environment. Users submit source code via a web-based frontend that communicates with a backend API responsible for managing submission requests and responses. Each submission is encapsulated as a job and placed into a centralized job queue within the cloudlet. A dynamically scaled pool of worker virtual machines retrieves jobs from the queue. It executes an evaluation pipeline that begins with test case execution, then performs object-oriented code quality analysis with PMD, and concludes with software design pattern detection by the LLaMA 3.1 large language model. Once the entire evaluation pipeline is complete, the output is retrieved by the backend API and presented to the user through the frontend interface. System-level monitoring continuously observes job-queue metrics, which are fed into an auto-scaling subsystem that provisions or deprovisions worker VMs in response to workload fluctuations, ensuring scalable throughput and low-latency processing under varying demand conditions.

Figure 2.

LambdaChecker queueing system in the cloudlet environment.

Evaluation tasks include precedence constraints within the worker pipeline. Each step depends on the successful completion of the previous one: test cases run first, followed by PMD analysis, and then LLaMA pattern detection. If test cases fail or take longer than the timeout time, subsequent steps are skipped.

A cloudlet-based LLM offers three main advantages over a traditional cloud deployment: (1) lower latency, since computation occurs closer to the user and enables faster, more interactive code analysis; (2) improved data privacy, as sensitive source code remains within a local or near-edge environment rather than being transmitted to distant cloud servers; and (3) reduced operational costs, because frequent analysis tasks avoid cloud usage fees and bandwidth charges while still benefiting from strong computational resources.

User-submitted code is incorporated into a pre-defined, improved prompt tailored to the specific coding problem to facilitate the detection of particular design patterns. The large language model then performs inference on a dedicated GPU queue supported by an NVIDIA H100 accelerator (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The prompt was refined to be clearer, more structured, and easier for a generative AI model to follow. It explicitly defines the JSON output, clarifies how to report missing patterns, and instructs the model to focus on real structural cues rather than class names. The rule mapping publisher–subscriber to the Observer pattern ensures consistent terminology. Overall, the prompt improves reliability and reduces ambiguity in pattern detection.

The prompt is concise, focuses only on essential instructions, and specifies a strict JSON output format, allowing the cloudlet-hosted LLM to process the code more efficiently without unnecessary reasoning or verbose explanations:

- “You analyze source code to identify design patterns. Output ONLY this JSON:

{

"design_patterns": [

{

"pattern": "<pattern_name>",

"confidence": <0-100>,

"adherence": <0-100>

}

]

}

- If no patterns are found, return {"design_patterns": []}."

Using this prompt, we obtained the following precision results. As previously reported in [4], the LLaMA model exhibited varying effectiveness in detecting design patterns on a separate dataset of student homework submissions. In that study, the model achieved high precision for Singleton (1.00) and Visitor (0.938), moderate precision for Factory (0.903) and Strategy (0.722), and lower precision for Observer (0.606). Recall values ranged from 0.536 for Visitor to 0.952 for Observer, highlighting differences in the model’s performance across patterns. We include the model overall results in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overall results for the LLaMA model on design pattern detection.

The system dynamically scales across multiple computing nodes in response to the number of active submissions. It continuously monitors the average service rate, which depends on the current submissions workload, and adjusts resources in a feedback-driven loop, scaling nodes up or down as required to ensure efficient processing. The scaling mechanism is based on a mathematical model described in the following subsection.

3.2. Mathematical Model

In our analysis, we consider only submissions that successfully pass all test cases. Submissions that fail or exceed the allowed time at any stage are eliminated, ensuring that only items which progress through all three stages of the pipeline (Test Cases → PMD Analysis → LLaMA Pattern Detection) are included. This allows us to measure the complete processing time W for each item consistently.

Additionally, there is no serial dependency beyond per-user ordering. Tasks from different users are independent and can run concurrently, so the system-level analysis assumes parallel execution across users, while each user’s pipeline remains sequential.

We consider a generic queueing system and introduce the following notation:

- : average queue length at time t;

- : arrival rate at time t (jobs per unit time);

- : effective arrival rate at time t (jobs per unit time);

- : service rate per machine (jobs processed per unit time);

- m: number of parallel processing machines (queues).

Even if the exact inter-arrival and service-time distributions are unknown, empirical traces in real systems typically exhibit diurnal variability, burstiness near deadlines, and transient queue-drain phases. A useful analytical approximation is to treat the system as an M/M/m queue with effective rates

leading to an approximate expected queue length

This approximation is valid whenever the stability condition

is satisfied; otherwise, the system becomes overloaded, and the queue diverges.

Although submission traces (Figure 1) exhibit burstiness and deviations from Poisson arrivals, we use the M/M/m model as a first-order approximation to capture the average system load. While the Poisson/exponential assumptions do not strictly hold, this approximation is valuable because it provides analytical insight into expected queue lengths and utilization. To partially account for burstiness, we introduce an effective arrival rate , which smooths short-term bursts and avoids overestimating congestion. The approximate expected queue length is then the one presented in the equations above.

For periods when and the system is overloaded, no stationary distribution exists. In this case, we use a fluid approximation that captures average queue growth:

If arrivals are indexed deterministically so that the n-th submission occurs at

then the approximate waiting time experienced by the n-th job is as follows:

Limitations: This model may underestimate peak queue lengths and does not accurately capture tail latencies. It is therefore intended primarily for average-load analysis rather than for fine-grained delay predictions.

4. Results

4.1. Case Study: LambdaChecker in a Programming Contest Increasing the Service Rate

We begin by analyzing a highly loaded contest scenario through a hypothetical M/M/1 queueing model.

We take these values from our dataset. As shown in Figure 1, we observe an average peak of approximately 270 submissions within 5-min intervals during the OOP practical examination. This gives an arrival rate of

After analyzing a historical contest dataset, the total evaluation time for submitted code ranges from 6.5 s to 17 s, with an average duration of 12.02 s. The code correctness evaluation is strictly limited to 2 s; executions that exceed this threshold result in a timeout exception and are excluded from further analysis. The PMD code quality analysis has a relatively fixed execution time of approximately 1.5 s. The remaining portion of the evaluation time is dominated by LLM inference, which varies with the input size (i.e., the number of tokens) and takes approximately 8.5 s on average. Given the average total evaluation time, this corresponds to a service rate of

The traffic intensity is

indicating severe overload and unbounded queue growth.

If we consider a single queue system, we can compute the final submission with its waiting time:

Thus, the 2119th job waits roughly 6 h and 25 min before service begins.

4.2. Determining the Required Number of Machines

To prevent unbounded queue growth during peak contest activity, we model LambdaChecker as an M/M/c system with c identical processing nodes.

- Peak Load Parameters (from our dataset)

- Total Service Capacity

- Stability Condition

- Minimum Machines Required

Thus, at least 11 machines are needed to sustain the peak arrival rate without unbounded queueing. However, puts the system close to critical load (), meaning small fluctuations can still cause delays. In practice, provisioning at least 12 machines yields significantly more stable performance.

By constraining the number of jobs permitted per user and discarding any excess submissions, the system’s effective load is reduced, thereby decreasing the required number of nodes. This represents just one specific instance of a broader class of resource-management strategies commonly employed to limit system load. Such methods, while effective at stabilizing resource usage, may result in discarded submissions; thus, an appropriate balance between system robustness and user experience must be carefully maintained.

5. Discussion

We evaluated the impact of our optimization strategies, based on our mathematical model, on system performance as the number of processing nodes increased. In addition, we discuss applying queue policies to limit the number of submissions per user. To validate and explore the queuing behavior empirically, we implemented a discrete-event simulation in Python [24].

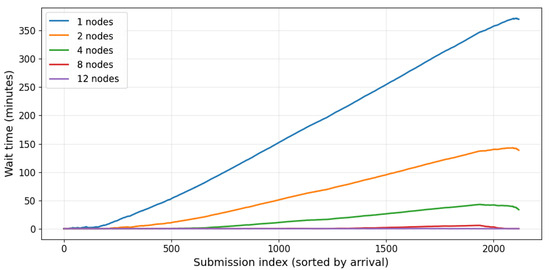

In our simulation, arrivals enter a single global queue managed in first-come, first-served (FCFS) order by arrival time. When a processing node becomes free, the job at the head of the global queue is assigned to that node for immediate processing. Thus, the system operates as a single pooled resource. This discipline corresponds exactly to the standard queuing model used in Section 3.2, which assumes a pooled set of identical servers with a shared waiting line. This ensures that no VMs remain idle while jobs wait in the queue. The results are visualized in Figure 3 and Figure 4—in plots of wait times per submission, providing a clear picture of how increasing the number of queues improves performance.

Figure 3.

Per-submission wait times across varying numbers of nodes, illustrating the impact of node availability on processing delays. We prove that for our case study, using 12 nodes makes the system stable.

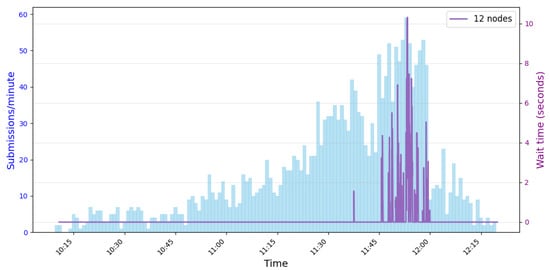

Figure 4.

Submission frequency and wait times with a fixed number of 12 processing nodes.

5.1. Effect of Scaling Machines

Figure 3 illustrates the expected waiting time for different numbers of machines (processing nodes). Consistent with M/M/m queueing theory, increasing the number of nodes reduces the waiting time, particularly during peak submission periods. For the original single-server setup, the traffic intensity , resulting in extremely long queues—our calculations show that the last submissions could experience waiting times exceeding 6 h. Doubling or appropriately scaling the number of machines significantly reduces and stabilizes the queue. While effective, this approach requires additional infrastructure, highlighting the trade-off between system performance and operational costs.

In Figure 4, we include a simulation with 12 processing nodes to validate the accuracy of our previous computations. Among the 2119 submissions, the maximum queueing delay observed is approximately ~10.3 s. With 12 processing nodes, the queueing delay remains below 11 s throughout the contest. Given a maximum job evaluation time of approximately 15 s, the resulting end-to-end user-perceived latency, defined as the sum of queueing delay and evaluation time, remains below 25 s. In addition, we overlay the same submission frequency shown in Figure 1 over the contest duration to visualize the submission workload on LambdaChecker for a contest with 200 participants.

5.2. Effect of Queue Policies

By limiting the number of jobs per user and discarding excess submissions, the system reduces load and lowers the number of required nodes. This is an example of a common resource-management strategy that stabilizes usage but may discard submissions, necessitating a careful balance between system robustness and user experience.

5.3. Contest Insights from Code Evaluation System

Several insights arise from our analysis. First, limiting the effective arrival rate is especially impactful when the system is heavily loaded. Due to the non-linear relationship between waiting time and traffic intensity, small reductions in can lead to disproportionately large decreases in . Second, adding new processing nodes improves performance but increases operational costs, whereas queue policies provide significant benefits at minimal expense. Finally, controlling submissions not only reduces average waiting times but also stabilizes the queue, leading to more predictable processing times for users.

Beyond system metrics, these strategies have a direct impact on user experience and performance. When feedback was delayed or unavailable during the content, participants experienced uncertainty and frustration, often resulting in lower engagement and lower scores. In the initial run, some students waited up to five minutes to receive feedback. In contrast, when feedback was returned more quickly (e.g., in under 25 s), users could identify and correct errors promptly, boosting both learning and confidence. To ensure comparability, participants were offered problems of similar difficulty across conditions. Our data show that with faster feedback, the average score increased from 53 to 69 out of 100. This demonstrates that system-level optimizations not only improve operational efficiency but also meaningfully enhance users’ outcomes and engagement.

While several alternative queueing strategies exist in the literature, such as Shortest Job First (SJF) [25] and Multilevel Feedback Queues (MLFQ) [26], these approaches are typically motivated by environments with high variability in job runtimes, preemption support, or runtime estimates. In contrast, student submissions in our system have short, tightly bounded evaluation times (typically 6–18 s) and are executed non-preemptively. Under these conditions, a First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) policy provides a simple, fair, and effective scheduling strategy without the overhead or assumptions required by more complex schedulers. In addition, we incorporate LLM-based design pattern detection to accelerate evaluation and improve accuracy.

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

The M/M/m approximation assumes exponential inter-arrival and service times, which may not fully capture the real-world behavior of submissions. Variability in machine performance and user submission patterns may affect the observed service rate , and queue-limiting policies could influence user behavior in ways not captured by this static analysis. Despite these limitations, our combined approach provides a practical and data-driven strategy for managing waiting times effectively, balancing system performance, stability, and operational cost. Our mathematical model may apply to other institutions or online judge platforms with different user populations, submission behaviors, or infrastructure. Future work could explore more realistic arrival distributions and system configurations to capture these practical considerations better.

While our results demonstrate significant performance improvements over our previous system, we did not perform a direct experimental comparison against queueing disciplines such as SJF or MLFQ. We acknowledge this as a limitation of the current study and identify the empirical evaluation of these alternative scheduling policies as a subject for future work.

6. Conclusions

Our analysis shows that a combination of server scaling and queue-control policies can effectively manage system performance during peak submission periods. Analytical calculations indicate that a single-server setup becomes severely overloaded under peak demand, leading to waiting times of several hours. Adding new processing nodes reduces waiting times, although it incurs additional infrastructure costs.

Queue-management policies that limit the number of active submissions per user substantially reduce the effective arrival rate, decreasing both the average waiting time and the queue variability. This approach delivers significant performance improvements at minimal cost and helps stabilize the system, preventing extreme delays even during high submission rates.

The combination of server scaling and submission control yields the best results, maintaining manageable queues and near-optimal waiting times throughout peak periods. Timely feedback directly improves participants’ experience and performance. Delays create uncertainty and frustration, lowering engagement, while feedback within 25 s lets users quickly correct errors, boosting understanding, confidence, and contest results. We found that providing faster feedback boosted average scores by approximately 30% on tasks of similar difficulty, highlighting how reducing wait times can improve performance outcomes. These findings demonstrate that system-level optimizations not only improve operational efficiency but also meaningfully enhance users’ outcomes and engagement. This emphasizes the importance of balancing technical performance with participants’ satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-F.D. and A.-C.O.; methodology, N.Ț.; software, D.-F.D.; validation, A.-C.O. and N.Ț.; formal analysis, D.-F.D.; investigation, D.-F.D. and A.-C.O.; resources, N.Ț.; data curation, D.-F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-F.D.; writing—review and editing, A.-C.O. and N.Ț.; visualization, D.-F.D.; supervision, N.Ț.; project administration, N.Ț.; funding acquisition, A.-C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Program for Research of the National Association of Technical Universities under Grant GNAC ARUT 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study utilized fully anonymized data with no collection of personally identifiable information. Based on these characteristics, the study qualified for exemption from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Paper dataset and scripts can be found at https://tinyurl.com/2z4tf4yc (accessed on 10 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Emil Racec for coordinating the development of LambdaChecker.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kuklick, L. When Computers Give Feedback: The Role of Computer-Based Feedback and Its Effects on Motivation and Emotions. IPN News. 24 June 2024. Available online: https://www.leibniz-ipn.de/en/the-ipn/current/news/when-computers-give-feedback-the-role-of-computer-based-feedback-and-its-effects-on-motivation-and-emotions (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Dosaru, D.-F.; Simion, D.-M.; Ignat, A.-H.; Negreanu, L.-C.; Olteanu, A.-C. A Code Analysis Tool to Help Students in the Age of Generative AI. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, Krems, Austria, 16–20 September 2024; pp. 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- PMD. An Extensible Cross-Language Static Code Analyzer. Available online: https://pmd.github.io/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Dosaru, D.-F.; Simion, D.-M.; Ignat, A.-H.; Negreanu, L.-C.; Olteanu, A.-C. Using GenAI to Assess Design Patterns in Student Written Code. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2025, 18, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavota, G.; Linares-Vásquez, M.; Poshyvanyk, D. Generative AI for Code Quality and Design Assessment: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Softw. 2022, 39, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; de Oliveira Pinto, H.P.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G.; et al. Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta AI. Introducing Meta Llama 3.1: Our Most Capable Models to Date. 23 July 2024. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/meta-llama-3-1/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qian, Z. Design and Implementation of an Online Judge System Based on Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2nd International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analysis, Chengdu, China, 28–30 April 2017; pp. 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, T. A Scalable Online Judge System Architecture Using Container-Based Sandboxing. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Keuning, H.; Jeuring, J.; Heeren, B. A Systematic Literature Review of Automated Feedback Generation for Programming Exercises. ACM Trans. Comput. Educ. (TOCE) 2018, 19, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, A.; Buliaiev, M.; Sandu, R. Automated Assessment of Programming Assignments: A Survey. Inform. Educ. 2021, 20, 551–580. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Li, K. Dynamic Task Offloading and Resource Scheduling for Edge-Cloud Collaboration. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 95, 522–533. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, W. A Survey on Mobile Edge Networks: Convergence of Computing, Caching and Communications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 197689–197709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouliaras, S.; Sotiriadis, S. An adaptive auto-scaling framework for cloud resource provisioning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 148, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, Q.; Chen, W.; Chen, S.; Xiang, Y. Adaptive Autoscaling for Cloud Applications via Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2021, 9, 1162–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.G.; Taheri, J.; Al-Dulaimy, A.; Kassler, A. PerfSim: A Performance Simulator for Cloud Native Microservice Chains. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2021, 11, 1395–1413. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Pinheiro, T.F.; Pereira, P.; Silva, B.; Maciel, P.R. A performance modeling framework for microservices-based cloud infrastructures. J. Supercomput. 2022, 79, 7762–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva, S.; Polin, E.; Moiseev, A.; Sztrik, J. Performance Modeling of Cloud Systems by an Infinite-Server Queue Operating in Rarely Changing Random Environment. Future Internet 2025, 17, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.Z.; Srivastava, N.; Sindhgatta, R.; Karkare, A. Characterizing the pedagogical benefits of adaptive feedback for compilation errors by novice programmers. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering Education and Training (ICSE-SEET), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 June–19 July 2020; pp. 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Y.K.; Tobin, R.W.; Wilson, N.R.; Brandon, L.A. Improving student success by incorporating instant-feedback questions and increased proctoring in online science and mathematics courses. J. Teach. Learn. Technol. 2020, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govea, J.; Edye, E.O.; Revelo-Tapia, S.; Villegas-Ch, W. Optimization and scalability of educational platforms: Integration of artificial intelligence and cloud computing. Computers 2023, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, K.; Park, H. Watcher: Cloud-based coding activity tracker for fair evaluation of programming assignments. Sensors 2022, 22, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas, L.; Vilaplana, J.; Mateo, J.; Solsona, F. A Queuing Theory Model for Fog Computing. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 11138–11155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosaru, D. Optimized Code Evaluation Simulation; GitHub Repository, Main Branch. Available online: https://github.com/dosarudaniel/optimized_code_evaluation_simulation/tree/main (accessed on 10 December 2025). Software version used: Python script as available in the main branch at the time of access.

- Alworafi, M.A.; Dhari, A.; Al-Hashmi, A.A.; Darem, A.B.; Suresha. An improved SJF scheduling algorithm in cloud computing environment. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), Mysuru, India, 9–10 December 2016; pp. 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Khan, M.A.; Kim, S.W. Exploring multilevel feedback queue combinations and dynamic time quantum adjustments. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 36, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).