1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of intelligent transportation systems, modern vehicles are increasingly equipped with autonomous driving and real-time perception capabilities, which generate massive volumes of data [

1,

2]. However, traditional vehicles often lack sufficient computing and storage resources to process such latency-sensitive and computation-intensive tasks [

3,

4]. Mobile Edge Computing (MEC), an emerging paradigm that deploys computing resources at the network edge, has been integrated into vehicular networks to address these challenges [

5,

6,

7]. By offloading tasks to nearby roadside units (RSUs) acting as edge servers, MEC provides low-latency, high-bandwidth computing services, thereby supporting critical applications like collision monitoring and in-vehicle entertainment [

8,

9,

10].

Despite these benefits, the integration of MEC introduces significant privacy vulnerabilities. A primary concern arises from the common practice of offloading tasks to the nearest server to minimize latency, which creates a strong correlation between a vehicle’s location and its accessed server [

11,

12,

13]. Adversaries capable of monitoring server access patterns can exploit this correlation to infer a vehicle’s real-time physical location. Compounding this issue, MEC servers are often deployed in open roadside environments, making them more susceptible to compromise than centralized clouds. Critically, even intermittent observations become dangerous over time, as repeated vehicle–server interactions accumulate into prior knowledge. This historical data substantially amplifies the risk of privacy leakage beyond any single access event.

This long-term threat is formalized as Historical Inference Attacks. In such attacks, an adversary passively collects historical interaction records—such as access logs and offloading decisions—to build a profile of a vehicle’s behavioral patterns. This prior knowledge is then weaponized to infer real-time locations, reconstruct historical trajectories, and reveal service usage preferences. The potency of these attacks is fueled by two factors: the volume of access records over time allows for trajectory reconstruction, and vehicles often exhibit consistent offloading strategies at specific locations, strengthening the correlation between behavior and spatial position.

The challenge is further exacerbated in high-mobility environments like highways, where vehicles frequently hand over between edge servers. This not only increases the risk of task interruption but also intensifies privacy leakage, as adversaries can exploit rapid successions of access points to triangulate vehicle trajectories with greater speed and accuracy. The dynamic channel conditions and shortened server residence time in such environments render traditional, static scheduling strategies ineffective.

These observations reveal a critical challenge: designing a scheduling mechanism that mitigates prior-information-driven privacy leakage while maintaining system efficiency. This is non-trivial, as stronger privacy protection typically increases energy consumption or degrades computational performance. Existing task scheduling mechanisms primarily focus on minimizing latency or energy consumption, overlooking the risk of inference-based privacy leakage.

To bridge this gap, this paper proposes a dynamic privacy-preserving task scheduling framework. The core of our solution is a dual-algorithm framework specifically designed to tackle the complex trade-offs in dynamic vehicular environments. Our approach is structured in two complementary layers: First, we develop a Markov Approximation-Based Online Algorithm (MAOA), which provides a foundational method with theoretical guarantees, achieving near-optimal performance with provable convergence. Building upon this and aiming for enhanced adaptability in highly non-stationary scenarios, we further propose a Privacy-Aware Deep Q-Network (PAT-DQN) algorithm. This deep reinforcement learning-based solution excels at long-term decision-making, allowing it to dynamically learn from and adjust to rapidly changing network conditions and mobility patterns. Together, these two algorithms form a comprehensive and adaptable framework for joint privacy and performance optimization. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

(1) Problem Formulation: We model the privacy leakage caused by historical inference in vehicular MEC and formulate a multi-objective optimization problem that jointly considers privacy, latency, and energy constraints.

(2) Dual-Algorithm Framework: We propose a two-phase strategy via a dual-algorithm framework. It employs a Markov Approximation-Based Online Algorithm (MAOA), with provable geometric convergence rate and -approximate near-optimality, and a Privacy-Aware Temporal Deep Q-Network (PAT-DQN) that integrates vehicular dynamics into state representation to enhance long-term adaptability in high-mobility scenarios.

(3) Comprehensive Evaluation: Extensive simulations validate that both algorithms effectively reduce cumulative privacy leakage while maintaining system efficiency. Notably, PAT-DQN achieves superior performance under high-mobility conditions due to its ability to learn non-myopic scheduling policies.

2. Related Work

The application of mobile edge computing in Telematics has attracted great attention and research. It mainly involves the allocation of appropriate servers through computation offloading for tasks. The relevant work is outlined as follows and it lists the existing limitations of current approaches in

Table 1:

2.1. Task Offloading in Mobile Edge Computing

The application of Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) in vehicular communication has attracted the attention and research of scholars from both China and abroad. The selection of the appropriate access server for task deployment can affect the efficiency of execution, so scholars have proposed different deployment strategies to choose the most appropriate target server, mainly including the following three types:

(1) Selecting server nodes based on the distance standard, availability in the region, or the time required to perform the task. For example, Zhu et al. [

14] proposed a dynamic task allocation scheme Folo for task allocation to edge servers. In this method, the target server selection depends on the estimated service time of the infrastructure edge node and selects the server with the shortest service time. In [

15], the authors proposed a distributed task deployment scheme called Chameleon, which uses the observation of fog node workload to obtain high-resolution images within a specific delay constraint. The target server node for task deployment is chosen based on the shortest path and the observed node workload at the end of each deployment process.

(2) Making decisions based on missing information in the edge node. Due to the mobile nature of vehicles and the constantly changing state of edge servers, the selection of the target server can become uncertain and complex. Some methods use learning-based approaches to handle uncertainty. For example, Liao et al. [

16] and Zhou et al. [

17] proposed a learning-based matching algorithm that uses the MAB framework to encourage edge servers in vehicular communication to share resources under information uncertainty. In the proposed method, each vehicle sends its preference list to the edge server during task deployment, and the edge server searches for any server that matches the list.

(3) Incentiving edge nodes to provide task deployment services. In vehicle-to-everything (V2X) systems, vehicles that have idle computing resources will not necessarily share them without any reward. Therefore, some studies have proposed incentive mechanisms to encourage fog nodes to share their available resources and receive rewards. For example, refs. [

18,

19] use contract theory to motivate different edge nodes to participate in task deployment, designing contracts for each willing fog node within the V2X communication environment The contract includes additional contract terms, such as the resource amount shared with corresponding rewards. Kazmi et al. [

20] also used contract theory to design an incentive mechanism for task deployment, to address the problem of selfish nodes and manage vehicle mobility. In their proposed method, the roadside unit (RSU) provides a reward to encourage vehicles to synchronize their mobility during task deployment to avoid task deployment interruption due to vehicle mobility. Recently, new approaches have been proposed to further improve task offloading performance in vehicular MEC. Zhang et al. [

28] proposed a trajectory-prediction-based pre-offloading framework that integrates LSTM and deep reinforcement learning to allocate resources dynamically and reduce delays. In addition, cooperative partial offloading strategies have been studied, where vehicles collaboratively share computation tasks to adapt to high-mobility scenarios. These works highlight the shift from static server selection toward trajectory-aware and cooperative scheduling in modern MEC systems.

2.2. Location Privacy Protection in Mobile Edge Computing

As access servers expose some privacy information of task requesters in edge systems, research in [

21,

22,

23,

29,

30] focuses on the privacy leakage problem in edge systems. Literature [

21] first proposes two privacy issues caused by the unloading characteristics of edge computing: location privacy and usage pattern privacy. It proposes an heuristic privacy measurement method to quantitatively evaluate these privacy leaks, and proposes a privacy-aware task unload scheme based on a constrained Markov model to minimize the delay and energy consumption of mobile devices while protecting their privacy. In [

29], Min proposes a privacy-aware unload scheme for healthcare IoT devices driven by energy harvesting to select the unload rate and local computing rate to process medical sensing data. The scheme considers the current radio channel state, the size and priority of new healthcare sensing data, the estimated energy state, battery level, and task computing history to reduce the computing delay, save energy for IoT devices, and enhance privacy levels. Li et al. [

22] transform the joint optimization problem of task unload and privacy protection into a context-based gambling machine (CMAB) problem to obtain a suboptimal solution that protects user location privacy and device usage pattern privacy while minimizing the computing delay and energy consumption. Literature [

30] proposes a task unload method that can resist prior knowledge attacks, and formulates the problem of finding an optimal task unload decision as a Markov decision process (MDP), and solves the unload problem based on deep reinforcement learning. He et al. [

23] believe that in the scenario where servers are densely deployed, user locations can be easily leaked with high precision, and propose a privacy-aware unload scheme based on deep decision-making state (PDS) learning algorithm, which learns the privacy-aware offload strategy faster than the traditional deep

Q network. In recent years, several new approaches have emerged to enhance privacy protection in MEC. Zhang et al. [

28] proposed a joint design of differential privacy and offloading strategies, introducing calibrated perturbation during task offloading to balance latency, energy consumption, and privacy levels. Ahmadvand and Foroutan [

31] designed a latency- and privacy-aware resource allocation framework that adaptively assigns tasks to vehicles, RSUs, or cloud servers based on real-time privacy requirements. Bashir et al. [

32] conducted a comprehensive survey on privacy-preserving techniques in edge computing and mobile crowdsensing, including trajectory obfuscation, differential privacy, and access pattern hiding, and highlighted open research challenges.

The above-mentioned privacy protection schemes in edge systems have explored the issue of location privacy in various scenarios, but these schemes have not carried out in-depth research on the impact of prior knowledge on location privacy leakage and have not provided specific definitions for the relationship between prior knowledge and location privacy leakage. Compared with current single-point location privacy protection schemes, attackers require less computational resources and higher accuracy to speculate on vehicle locations based on vehicle trajectory and unload patterns, and current unload strategies, resulting in greater loss of location privacy. Therefore, this paper proposes a task scheduling method to resist prior knowledge attacks to provide stronger location privacy protection for vehicles.

2.3. Federated Learning and Blockchain-Assisted Scheduling

Beyond conventional optimization and privacy preservation methods, Federated Learning (FL) and blockchain have emerged as promising paradigms for collaborative and trustworthy computing in VEC environments.

Federated Learning enables distributed model training across vehicles or edge servers without centralizing raw data, thereby preserving data privacy during model updates [

24]. For instance, Zhang et al. [

26] utilized FL for collaborative trajectory prediction to optimize pre-offloading decisions. However, FL’s iterative model aggregation process typically introduces substantial communication overhead and latency, making it challenging to meet the stringent real-time requirements of task scheduling in high-mobility scenarios.

Complementarily, blockchain technology provides decentralized trust through immutable transaction records and automated smart contracts, ensuring transparent and auditable offloading agreements [

25]. Recent works like Lu et al. [

27] have further integrated blockchain with FL to enhance security and reliability in collaborative learning systems. Nevertheless, the consensus mechanisms in blockchain often incur significant computational costs and delays, which conflict with the low-latency demands of VEC task scheduling.

While these approaches offer innovative solutions for data privacy and transactional security, they primarily address different aspects of VEC challenges. Specifically, they do not explicitly model or mitigate the cumulative location privacy leakage from historical offloading patterns - which represents the core threat model and research focus of our work. Our proposed framework distinguishes itself by providing a lightweight online scheduling solution that directly optimizes the real-time privacy-cost trade-off against historical inference attacks.

3. Problem of Location Privacy Leakage Due to Prior Information

3.1. Threat Model and Problem Analysis

We consider a passive adversary who aims to infer a vehicle’s private information by exploiting the long-term correlations in its task offloading behavior. This adversary can monitor historical task offloading records from a subset of edge servers, including connection times and server identities, and possesses background knowledge such as road network topology. The adversary’s primary goal is to infer the vehicle’s real-time location, reconstruct its historical trajectory, and reveal service usage preferences. This is achieved through two main methods: (1) Trajectory Reconstruction, where the sequence of accessed servers is compared against candidate trajectories using similarity measures like EDR to identify the most likely path; and (2) Strategy-Location Binding, where frequent use of a specific offloading strategy at a location creates a strong correlation that the adversary learns and exploits. Critically, we assume the adversary cannot access the vehicle’s GPS data or tamper with system operations, and its inferences remain probabilistic due to environmental dynamics and system heterogeneity.

We model location privacy loss as the sum of two components: loss due to access history (

) and loss due to offloading strategy history (

). Assuming the vehicle’s driving time is divided into discrete slots

, the total privacy loss per slot is:

3.2. Location Privacy Metrics for Access Prior Information

Each time a vehicle connects to an edge server, it reveals a location point. Over time, these points form a released trajectory . Attackers may also possess a set of speculated trajectories , each represented as .

The adversary infers the vehicle’s trajectory by comparing the released access points

against candidate trajectories

Q. We quantify the privacy loss from this inference as the reduction in the entropy of the adversary’s belief distribution. We model the attacker’s inferred probability

that trajectory

is the true trajectory at

, based on its similarity to

. Similarity is computed using the Edit Distance on Real sequence (EDR) measure:

where

is the minimal edit operations needed to match trajectories. The probability is then:

The privacy loss due to access history is defined as the reduction in entropy of the trajectory distribution:

Thus, the privacy loss is defined as the reduction in Shannon entropy from the state of maximum uncertainty to the current entropy , directly measuring the amount of information leaked to the adversary through server access patterns.A smaller entropy implies higher privacy loss.

3.3. Location Privacy Metrics for Offloading Strategy Prior Information

Attackers may also infer locations from frequently used offloading strategies. Let

be the set of possible strategies, with historical frequencies

. The probability of using strategy

is:

The corresponding privacy loss is measured as the entropy reduction of the strategy distribution:

Again, lower entropy indicates greater privacy loss.

Lemma 1. Under the unified entropy framework, privacy loss increases as the probability distributions for both trajectory access and offloading strategy become more concentrated, i.e., as the number of trajectory offloads or the frequency of a specific strategy increases.

Proof Sketch: Let be a probability distribution with entropy . If probability mass shifts from a smaller to a larger component (making the distribution more peaked), entropy decreases due to the strict concavity of .

For access priors, more offload points make the true trajectory more identifiable, reducing and increasing . Similarly, for strategy priors, higher strategy frequency skews the distribution, reducing and increasing . Thus, total loss grows monotonically with offload count and strategy repetition.

This analysis shows that reducing both the number of trajectory offloads and the strategy repetition frequency can effectively mitigate location privacy leakage. □

4. System Model and Problem Formulation

4.1. System Overview

The vehicle is driving at a constant speed and making continuous service requests to edge servers. It is assumed that the task set at time slot

is represented by

, where

N is the number of tasks. A task request is represented by a tuple

, where

represents the amount of data uploaded by the task,

represents the amount of data downloaded by the task, and

represents the resources required to process the task.

and

are defined as the sets of local computation tasks and offloading tasks, respectively. The available computing devices around vehicle

v at time slot

are

, where

represents the local computing device and

K is the number of available servers. The specific symbol meaning is shown in

Table 2. The aim of this paper is to select an offloading strategy

at time slot

to allocate appropriate edge servers to each task, and minimize the system overhead while protecting location privacy.

4.2. Delay Cost Model

Computing Delay Model:there are two types of tasks on a vehicle: local computation tasks and upload tasks to edge servers. Since the computing power of these two types of devices is different, the computing delay produced by them is also unequal. Assuming that the task amount of a single task on a vehicle in time slot

is

, the computing delay of local computation and server computation is represented by the following formulas:

where

represents the computing capacity of the device,

represents the computational power of the vehicle’s local device, and

represents the computational power of the edge server.

Communication Delay Model:in a vehicle-to-server edge system, there is a communication delay caused by the distance between the vehicle and the server. To simplify the problem, this paper does not consider packet loss due to signal attenuation, network quality, and other factors. The network bandwidth of the output data downlink channel and the input data upload channel is set to be equal, and according to Shannon’s theorem, the data upload rate and download rate between the vehicle and the edge server can be represented as [

33,

34]:

where

is the channel bandwidth,

is the channel gain between the vehicle

v and the edge node

s, and

is the white noise power. To better capture real-world vehicular dynamics, we extend the system model by introducing vehicle speed

and acceleration

. These parameters affect the channel gain

, the expected residence time in a server’s coverage, and the frequency of handovers. Accordingly, the communication delay model is updated as

reflecting the time-varying channel quality under high mobility. Assuming that the task set required for offloading computation in time slot

t is

, the uploading and downloading time of vehicle

v is:

Therefore, combining Formulas (13) and (14), the total communication delay in time slot

is:

The total computing delay required for vehicle

v to complete a task is:

4.3. Energy Cost Model

In this system, the energy consumption includes both local computation energy and task offloading (transmission) energy. For local computation, the energy consumption of executing task

is modeled as proportional to the required CPU cycles and the square of the local CPU frequency, i.e.,

where

denotes the number of computing cycles required by task

,

is the operating frequency of the local CPU, and

is the effective switched capacitance coefficient. For task offloading, the energy consumption is determined by the transmission power and duration, given by

where

denotes the transmission power of the vehicle, and

is the transmission duration of task

. The total energy consumption is then expressed as

. Since delay and energy are measured in different units, a normalization method is adopted to define the system cost. Specifically,

where

and

are normalization factors, and

is a tunable parameter that controls the relative importance of energy with respect to delay. We incorporate a handover cost term

into the system cost function to quantify the additional latency and privacy leakage caused by frequent server switches. This enhancement allows the scheduling scheme to explicitly consider high-mobility conditions and proactively adapt offloading strategies to maintain robustness.

4.4. Problem Definition

We study the vehicle location privacy protection problem under the attack of privacy inference with prior information. Since the vehicle’s movement is a long-term process, we need to minimize the long-term system cost under the constraint of long-term privacy loss budget. We introduce

to represent the threshold of privacy loss at each time slot

, and the average privacy loss over the long-term must be less than or equal to it.

Our goal is to select an appropriate offloading strategy for each task and allocate appropriate servers to minimize the long-term system cost under the constraint of prior privacy loss. The objective function is represented as follows:

where problem P1 is to minimize the long-term system cost. The first row of the constraint represents the long-term prior privacy loss constraint.

is the offload identifier, its value of 1 indicates that the policy

is selected, and its value of 0 indicates that it is not selected and the second and third rows ensure that there is only one offloading strategy selected at each time slot

.

However, due to the inability to accurately predict the vehicle’s movement and task requests, the long-term problem P1 cannot be solved in a single calculation and needs to be constantly adjusted to adapt to the dynamic changes in the system. Although the long-term privacy protection problem can be decomposed into real-time decoupled problems, reducing frequent access through privacy constraints is relatively difficult. Therefore, we introduce the Lyapunov optimization to convert the long-term constraint problem into a series of real-time minimization problems without any prior vehicle system information, and can maintain the stability of long-term access privacy cost in an online manner.

5. Proposed Algorithm

5.1. Overview

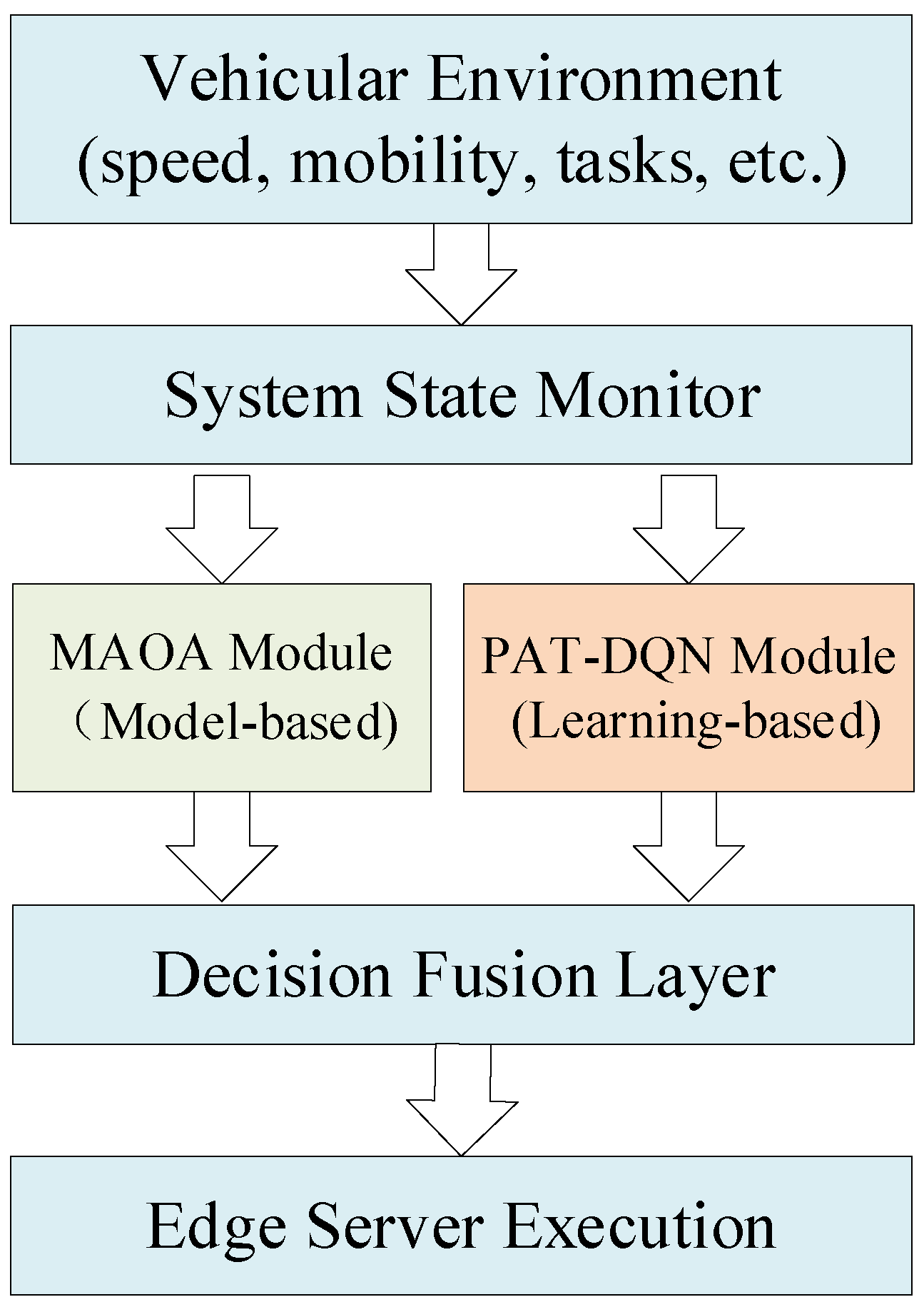

To effectively address the complex trade-offs between privacy preservation and system efficiency in dynamic vehicular environments, we propose a dual-algorithm framework that synergistically integrates model-based optimization with data-driven learning. As show in

Figure 1, the framework is built upon a rigorous Lyapunov optimization foundation, which transforms the long-term stochastic optimization problem into a sequence of tractable per-time-slot subproblems. This transformation enables online decision-making while maintaining stability of privacy constraints.

On this theoretical foundation, we develop two complementary algorithmic instances: (1) a Markov Approximation-Based Online Algorithm (MAOA) that provides provable near-optimal performance under stationary conditions, and (2) a Privacy-Aware Temporal Deep Q-Network (PAT-DQN) that leverages deep reinforcement learning to handle environmental uncertainties and non-stationary dynamics. The dual-algorithm design ensures both theoretical soundness and practical adaptability, making it suitable for the diverse operational conditions encountered in vehicular MEC systems.

5.2. Lyapunov-Based Online Scheduling Formulation

To handle the long-term nature of privacy-performance trade-offs, we employ Lyapunov optimization theory to transform the original stochastic problem into deterministic per-slot problems. We first define a virtual queue

to track the accumulated privacy cost deviation from a predetermined threshold

:

The Lyapunov function

measures the congestion level of the virtual queue. We then define the conditional Lyapunov drift as:

To simultaneously maintain queue stability and minimize system cost, we introduce the drift-plus-penalty expression:

where

V is a control parameter that balances cost minimization and constraint satisfaction.

For any feasible offloading strategy, the drift-plus-penalty expression satisfies:

where

is a finite constant.

Proof. Squaring the queue dynamics equation:

Rearranging terms and taking conditional expectations yields the result. □

Based on this upper bound, we formulate the per-slot optimization problem:

Solving Problem P2 at each time slot guarantees that the time-average system cost is within of the optimal value while maintaining the virtual queue mean rate stable.

5.3. Markov Approximation-Based Online Algorithm (MAOA)

Problem P2 constitutes a combinatorial optimization problem that is NP-hard in general. We employ Markov approximation to obtain near-optimal solutions with provable performance bounds. The core idea involves transforming the original problem into a probability assignment problem over the strategy space .

We first consider the equivalent problem:

where

.

To make the problem tractable, we introduce the log-sum-exp approximation with parameter

:

The optimal solution to this approximated problem takes the Gibbs form:

To realize this distribution in practice, we construct a time-reversible Markov chain with state space

and stationary distribution

. The transition probability between strategies

z and

is designed as:

where

controls the exploration rate. This design ensures detailed balance:

Algorithm 1 implements the MAOA procedure, which iteratively refines the offloading strategy through Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling. The computational efficiency of MAOA is crucial for its online applicability. In each iteration of Algorithm 1, a new strategy

is generated by perturbing the current strategy

z, typically by reassigning a single task. The key operation is evaluating the cost difference

. Since the perturbation is local, the change in system cost

and privacy loss

can be computed in constant time,

, by only recalculating the terms affected by the reassigned task, without processing the entire task set. Consequently, the per-iteration complexity is

. Given the geometric convergence rate of the underlying Markov chain [

35], the algorithm reaches a near-stationary distribution efficiently. This low per-iteration cost makes MAOA highly suitable for real-time scheduling.

| Algorithm 1 MAOA for Online Scheduling |

Require: Task set , server set S, parameter ,

Ensure: Near-optimal strategy

Initialize strategy by random assignment

,

repeat

Randomly select task and generate new strategy

Compute and acceptance probability:

With probability :

if then

,

end if

until convergence criteria met

return

|

5.4. Privacy-Aware DQN-Based Adaptive Scheduling (PAT-DQN)

While MAOA provides theoretical guarantees under stationary conditions, its performance may degrade in highly dynamic environments with time-varying statistics. To address this limitation, we develop PAT-DQN, a deep reinforcement learning approach that learns optimal policies through direct interaction with the environment.

5.4.1. Algorithm Design

The PAT-DQN algorithm employs a deep Q-network architecture to approximate the optimal action-value function in complex vehicular edge computing environments. The network comprises multiple fully connected layers with ReLU activation functions, specifically designed to handle the high-dimensional state space while maintaining computational efficiency essential for real-time task scheduling. Given the dynamic nature of vehicular environments and the stringent requirements for privacy preservation, we incorporate three fundamental techniques to enhance learning stability and convergence.

First, the experience replay mechanism stores transition tuples

in a circular buffer and employs random mini-batch sampling during training, effectively breaking temporal correlations in the sequential data—a crucial feature for dealing with rapidly changing vehicle mobility patterns and network conditions. Second, the target network approach maintains a separate Q-network

whose parameters are periodically updated from the main network, thereby providing stable learning targets and preventing harmful feedback loops that could arise from the non-stationary nature of the vehicular environment. Third, the double Q-learning technique decouples action selection from value estimation, significantly reducing the overestimation bias common in conventional DQN algorithms—particularly important in our context where the action space encompasses numerous offloading decisions with varying privacy and performance implications. These techniques work in concert to ensure robust learning performance amid the inherent uncertainties of vehicular edge computing systems. The training process minimizes the temporal difference error through the following objective function:

where

is the target value. It enables accurate long-term value estimation and forms the foundation for making optimal task offloading decisions that balance immediate rewards with future consequences. The complete training procedure of PAT-DQN is summarized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 PAT-DQN: A Privacy-Aware Temporal Deep Q-Network |

Require: State space , action space , replay buffer size N

Ensure: Trained Q-network parameters

Initialize Q-network and target network

Initialize replay buffer with capacity N

for episode = 1 to M do

Observe initial state

for to do

Select action using -greedy policy

Execute , observe reward and next state

Store transition in

Sample random mini-batch from

Compute target values using double Q-learning

Update Q-network via gradient descent

Every C steps:

end for

end for

|

5.4.2. State and Action Representation

The state representation

in our framework comprehensively captures the essential dynamics of the vehicular edge computing system:

where

represents the vehicle’s current location,

and

capture the instantaneous velocity and acceleration patterns that influence mobility behavior,

indicates the current load conditions of available edge servers,

describes the set of pending computational tasks with their specific requirements, and

tracks the virtual queue length that quantifies accumulated privacy cost. This multidimensional state representation enables the learning agent to fully perceive environmental dynamics and make informed decisions that simultaneously address privacy concerns and system efficiency.

The action space is formulated as an N-dimensional vector where each component specifies the execution location for task , with 0 denoting local computation and values 1 through K representing different edge servers available for offloading. This discrete action space design comprehensively covers all possible offloading decisions while maintaining computational tractability, making it particularly suitable for vehicular environments where multiple independent computational tasks require scheduling decisions in each time slot.

5.4.3. Reward Function

The reward function is carefully designed to balance the multiple competing objectives in privacy-preserving task scheduling:

This composite reward structure incorporates three critical components: the system cost term accounts for the combined effects of task execution latency and energy consumption; the privacy loss term quantifies the risk of location information leakage through task offloading patterns; and the constraint violation indicator ensures that scheduling decisions respect system constraints.

The tunable parameters allow for flexible adjustment of relative importance among different objectives based on specific application requirements—in privacy-sensitive scenarios, increasing emphasizes privacy protection, while in energy-constrained environments, strengthening prioritizes energy efficiency. This nuanced reward design enables PAT-DQN to adaptively learn scheduling policies that dynamically balance privacy preservation and system performance across varying vehicular operating conditions, ultimately achieving an optimal trade-off between these competing demands in vehicular edge computing systems.

5.4.4. Stability in Non-Stationary Environments

The dynamic nature of vehicular networks introduces significant non-stationarity, posing a fundamental challenge to DRL stability. Our PAT-DQN algorithm proactively mitigates this through several interconnected techniques. The use of an experience replay buffer, which stores past transitions and samples them randomly, is crucial for breaking the temporal correlations in the sequential data, thereby preventing the model from overfitting to recent and potentially misleading trends. Furthermore, the separation of the target network from the online network provides a stable benchmark for Q-value updates, which is essential for consistent convergence in a fluctuating environment. This is complemented by the double Q-learning architecture, which explicitly decouples action selection from value estimation to curb the pervasive issue of overestimation bias. Finally, the richness of our state representation—incorporating kinematic data and server loads—equips the learning agent with a more contextualized view of the system, enabling it to discern underlying patterns amidst the apparent randomness. Together, these mechanisms foster robust policy learning capable of adapting to the inherent uncertainties of the vehicular edge.

5.5. Dual-Algorithm Integration and Synergy

The dual-algorithm framework is designed to achieve a balance between theoretical optimality and practical adaptability. The MAOA provides a mathematically provable near-optimal solution under Markov decision assumptions, ensuring convergence and analytical tractability. However, MAOA relies on prior statistical knowledge and is less effective in highly dynamic environments. In contrast, PAT-DQN leverages deep reinforcement learning to adaptively learn optimal scheduling policies from real-time interactions without requiring explicit system models. Together, the two algorithms complement each other by bridging the gap between model-based optimization and data-driven learning.

The MAOA serves as a baseline and theoretical reference for the system, providing convergence guarantees and performance bounds. PAT-DQN can be trained using the outputs of MAOA as a supervised initialization to accelerate learning convergence and improve policy stability. Thus, the two algorithms not only complement each other but can also be jointly deployed: MAOA provides guidance for early-stage scheduling, while PAT-DQN continuously refines decisions through learning.

The integration framework employs an adaptive switching mechanism based on environmental predictability. Let

represent a mobility predictability metric and

denote channel variation intensity. The algorithm selection rule is:

This hybrid approach ensures that the system leverages MAOA’s computational efficiency in stable conditions while employing PAT-DQN’s adaptability in dynamic scenarios. Furthermore, the algorithms can operate in concert during training phases, with MAOA generating initial policies that PAT-DQN refines through continued learning.

The complete framework thus achieves robust performance across diverse vehicular environments while maintaining the theoretical foundations necessary for rigorous performance analysis and system validation.

6. Implementation

6.1. Simulation Platform and Parameter Configuration

The simulation experiment in this article is based on Python 3.7, with an Intel i5 CPU and a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080Ti GPU running on the Windows 10 operating system. It is not a simple numerical simulation but a scenario-driven hybrid framework integrating vehicular mobility modeling and algorithm execution. Specific software tools and their roles are as follows: SUMO (Simulation of Urban MObility) is used to construct the vehicular mobility scenario, including the Manhattan grid road network topology and the logic of random direction selection at intersections; Regarding hardware utilization, the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080Ti GPU is exclusively used to accelerate the training phase of the PAT-DQN algorithm, particularly for batch gradient descent computation and neural network parameter updates—this configuration reduces PAT-DQN’s total training time by approximately 60% compared to CPU-only training.

In contrast, the MAOA algorithm, with O(1) per-iteration complexity as analyzed in

Section 4.3, has low computational demand and is executed on the Intel i5 CPU, which suffices to meet real-time scheduling requirements without GPU acceleration. In the context of vehicular communication, the coverage area of each edge server is 400 m, the speed of vehicle terminals is assumed to be 60 km/h, the local computing capability of vehicles is

=

cycles/s, and the computing capability of MEC servers is

=

cycles/s. The data transmission rate between vehicles and servers is distributed in the range [1, 5], and the data transmission rate between servers is 1.

The proposed PAT-DQN employs a specific neural network architecture and hyperparameters for training and inference. Key hyperparameters are set as follows: learning rate

), discount factor

, experience replay buffer capacity of 50,000 transition samples, and the target network is updated every

training steps. The specific simulation parameters are listed in

Table 3.

6.2. Vehicle Mobility and Task Generation Model

We simulate vehicle mobility using an enhanced Manhattan grid model, where vehicles move along grid roads and randomly select directions at intersections with equal probability. The vehicle speed was constant at 60 km/h, with random variations of ±20% to emulate realistic speed fluctuations, and the channel gain between the vehicle and the server was modeled based on the instantaneous distance. For task generation, a set of tasks was dynamically generated for the vehicle in each time slot . The task set size N varied from 10 to 90 to evaluate system performance under different loads. Parameters for each independent task were randomly generated: the data upload volume was uniformly distributed between 100 KB and 1 MB, the download data volume was set to 10% of , and the computational resources required to process the task were set to CPU cycles.

6.3. Modeling of Adversary’s Prior Knowledge

To accurately simulate historical inference attacks, the simulation first ran a 1000-time-slot “warm-up” phase using a baseline offloading strategy (e.g., the SCF scheme). This generated a log of the vehicle’s historical access points and offloading decisions, which was used to construct the adversary’s prior knowledge set . In each formal experimental run, the adversary initialized its belief—the probability distributions over possible vehicle trajectories Q and offloading strategies Z—based on . As the simulation proceeded and the vehicle made real-time offloading decisions, the adversary’s belief was dynamically updated based on new observational data. Specifically, trajectory inference utilized the EDR-based similarity measure, while strategy preference inference employed the frequency statistics method.

7. Experiment and Analysis

This section presents a comprehensive performance evaluation of the proposed privacy-aware task scheduling framework through simulation experiments. The experiments are designed to validate the effectiveness of our method in protecting vehicle location privacy while effectively controlling system overhead and maintaining stability and scalability in highly dynamic vehicular environments. Specifically, we conduct parameter sensitivity analysis, algorithm convergence verification, performance tests under varying task loads, and comparisons under different privacy constraints.

7.1. Experimental Setup and Compared Schemes

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithms, we established a complete simulation environment and implemented multiple baseline schemes for comparative analysis. The compared schemes include: the Local scheme where all tasks are executed on the vehicle’s local device; the Distance-based scheme that always offloads tasks to the nearest edge server; the Shortest Computing Cost First (SCF) scheme that solely aims to minimize system computational costs; and the PDS scheme, which only provides real-time protection for single-point location data. Based on these benchmarks, we evaluate two novel algorithms proposed in this paper: the Markov Approximation-Based Online Algorithm (MAOA) and the Privacy-Aware DQN-Based Task Scheduling (PAT-DQN) algorithm, which leverages deep reinforcement learning. We evaluate the algorithms across multiple dimensions, including parameter sensitivity, convergence, and performance under varying task loads.

7.2. The Effect of Parameter V on Performance

The Lyapunov control parameter V plays a pivotal role in balancing the trade-off between system cost and privacy protection. We investigate its impact by varying V from 0 to 1000 while keeping other parameters constant.

As shown in

Figure 2a,b, the parameter

V effectively regulates the system’s priority between cost efficiency and privacy preservation. Specifically, with an increasing

V, the system cost decreases monotonically, while the privacy cost exhibits an opposite, increasing trend. This inverse relationship is a direct consequence of the drift-plus-penalty framework in Lyapunov optimization. A larger

V assigns a higher weight to minimizing the instantaneous system cost

in the objective function P2 (Equation (

31)). Consequently, the Markov approximation process is biased towards selecting offloading strategies that minimize delay and energy consumption, often at the expense of higher privacy loss, as such strategies might involve more frequent and predictable server access.

The most significant changes occur when V increases from 0 to 200. As V continues to grow beyond 800, its marginal effect on both system cost and privacy loss diminishes, indicating a convergence in the algorithm’s scheduling behavior.

Furthermore,

Figure 2c demonstrates the stability of our proposed framework under different

V values. Despite the variation in steady-state privacy cost levels, the virtual privacy queue

consistently converges over time for all

V values. This validates that the long-term privacy loss constraint (Equation (

21)) is satisfied, as the time-averaged privacy cost stabilizes to a finite value, ensuring

.

In summary, the parameter V serves as a crucial tunable knob for the system operator to achieve a desired operational point based on specific application requirements—favoring lower system overhead when V is large, or stronger privacy protection when V is small.

7.3. The Effect of Parameter on the Convergence

is a coefficient that affects the accuracy of the Markov approximation process, and

Figure 3 shows the impact of

= 0.1, 0.5, 1 on the computational cost. In this experiment, the computational cost eventually stabilizes and converges to a fixed value with increasing iteration rounds. Moreover, the larger the

value, the lower the converged computational cost value. This is because in the Markov approximation process,

directly affects the value of the jumping probability, and when it approaches infinity, the system will jump to the direction of improvement with a probability of nearly 1. When

= 1, the curve is almost smooth and converges after approximately 2400 iterations, with a converged value below 300. As

decreases, the system generates increasing disturbance. When

= 0.5, the algorithm converges after approximately 1600 iterations, with a converged value around 350, while

= 0.1 converges after approximately 1200 iterations, with a converged value over 450. It can be concluded that the larger the

value, the lower system costs.

We discuss the effect of the size of the task set on location privacy loss when the access privacy budget is 500 and the offloading strategies privacy budget is 3. As shown in

Figure 4, as the size of the task set increases, the privacy loss of all the reference algorithms increases, but the privacy loss of the proposed algorithm is smaller than that of the SCF and PDS schemea. Although the PDS scheme also protects location privacy, it does not consider the problem of trajectory privacy leakage, so the privacy protection effect of the proposed scheme is better. Since the Local scheme completely calculates tasks on the local device and does not access the edge service, it does not leak access information to attackers. However, since attackers can still infer the location of the vehicle based on some other information, its privacy loss still exists but is the smallest and remains unchanged. When the size of the task set is 10, the local device is able to complete all tasks, so the privacy loss values of the Local, SCF, PDS, and MAOA scheme are relatively close. When the size of the task set is 30, 50, 70, and 90, the local device cannot complete all tasks, and except for the Local algorithm, all other algorithms need to offload some tasks to the edge server, resulting in the leakage of access information and an increase in the privacy loss of the offloading strategy.

Figure 5 shows the impact of different task set sizes on energy consumption, delay, and system cost. It can be seen that the trends for Local, MAOA, and SCF are the same as task count increases, with Local ’s energy consumption, delay, and computational cost being the highest, MAOA ’s being second, and SCF ’s being the lowest. This is because the Local performs all calculations locally, and the computational capabilities of local devices are lower than those of edge servers, so its energy consumption, delay, and computational cost are the highest. The SCF selects the strategy with the lowest computational cost, so its values are the smallest. The MAOA, in order to protect location privacy, will sacrifice some computational costs. In addition, when the task set size is 10 and 30, the three indicators of the four schemes are not greatly different because local devices can process the tasks, and the energy consumption and delay are not greatly different from uploading to edge servers for calculation. When the task set size is 90, the computational cost of the proposed scheme is lower than that of the Local scheme, although it is higher than that of the other two schemes. However, protecting privacy by sacrificing some system cost is acceptable.

7.4. The Effect of Access Privacy Budget on Performance

Since the access and offloading strategies affect the prior privacy loss, which in turn affects the system cost, they are discussed in the 6.4 and 6.5 experiments for their impact on performance. In this experiment, the impact of the access privacy budget being 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 on the scheme performance is discussed, with the task set size set to 50 and the offloading strategy privacy budget set to 3. In

Figure 6a, the Local scheme has the smallest access privacy loss, while the Distance-based scheme has the largest privacy loss. The MAOA scheme’s privacy loss increases as the budget increases. This is because the Local scheme performs all tasks locally, leaking less information. On the other hand, the Distance-based scheme selects the server with the nearest distance for calculation, resulting in more access points, which leaks more trajectory information. When the offloading strategy privacy budget is 1, due to the small budget, the MAOA scheme can only choose local computation to protect privacy, so its privacy loss is similar to that of the Local scheme. When the budget is 5, due to the large privacy budget, the MAOA scheme prefers to minimize the system cost by selecting more servers for task calculation, resulting in a larger privacy loss, and its real-time privacy loss is similar to that of the PDS scheme. However, in total, compared to the PDS scheme with single-point location protection, the privacy loss caused by the proposed scheme is smaller due to the simultaneous budget of access privacy loss and offloading strategy privacy loss.

From

Figure 6b–d, it can be seen that as the access privacy budget increases, the energy consumption, delay, and system cost of the MAOA scheme constantly decrease. This is because as the access privacy budget increases, there are more strategies available for vehicles to choose from, enabling them to implement an appropriate strategy to minimize the system cost. When the access privacy constraint is 1 and 2, due to the low privacy budget, vehicles can only choose to perform local computation to meet the budget constraint, so the three indicators of the MAOA scheme are not very different from those of the Local scheme. As the budget increases, the MAOA scheme approaches the system cost-minimizing SCF scheme, indicating that the proposed scheme has good performance in terms of energy consumption and delay.

7.5. The Effect of Offloading Strategies Privacy Budget on Performance

Figure 7 shows the the effect of offloading strategies privacy budget being 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 on the scheme performance, with the task set size set to 50 and the access privacy budget set to 3. Similar to

Figure 6a, the privacy costs of the MAOA scheme increases as the privacy constraint increases in

Figure 7a. When the access privacy budget is 1, due to the small offloading strategy privacy budget, the MAOA scheme can only choose local computation or have almost the same selection frequency for each strategy to achieve privacy protection, making it difficult for attackers to speculate on the offloading preferences of vehicle users. Therefore, its privacy costs is most similar to that of the Local scheme. When the constraint is 5, due to the large offloading strategy privacy budget, the MAOA scheme prefers to choose the strategy with the lowest system cost, rather than prioritize privacy protection, resulting in a similar offloading strategy privacy loss to the SCF scheme.

In

Figure 7b–d, the three indicators of the MAOA scheme decrease as the privacy budget increases because as the privacy budget increases, vehicles can choose strategies that minimize the system cost while maintaining privacy protection. Similar to

Figure 7a, when the privacy constraint is 1, the three indicators of the MAOA scheme are similar to those of the Local scheme. When the privacy constraint is 5, the MAOA scheme is similar to the minimum system cost scheme SCF, indicating that the proposed scheme has a lower system costs.

In summary, the proposed scheme can achieve lower system costs while ensuring privacy protection. Compared to the single-point protection scheme, the proposed scheme has better privacy protection performance for vehicle location.

7.6. Comparison with DQN-Based Adaptive Scheduling

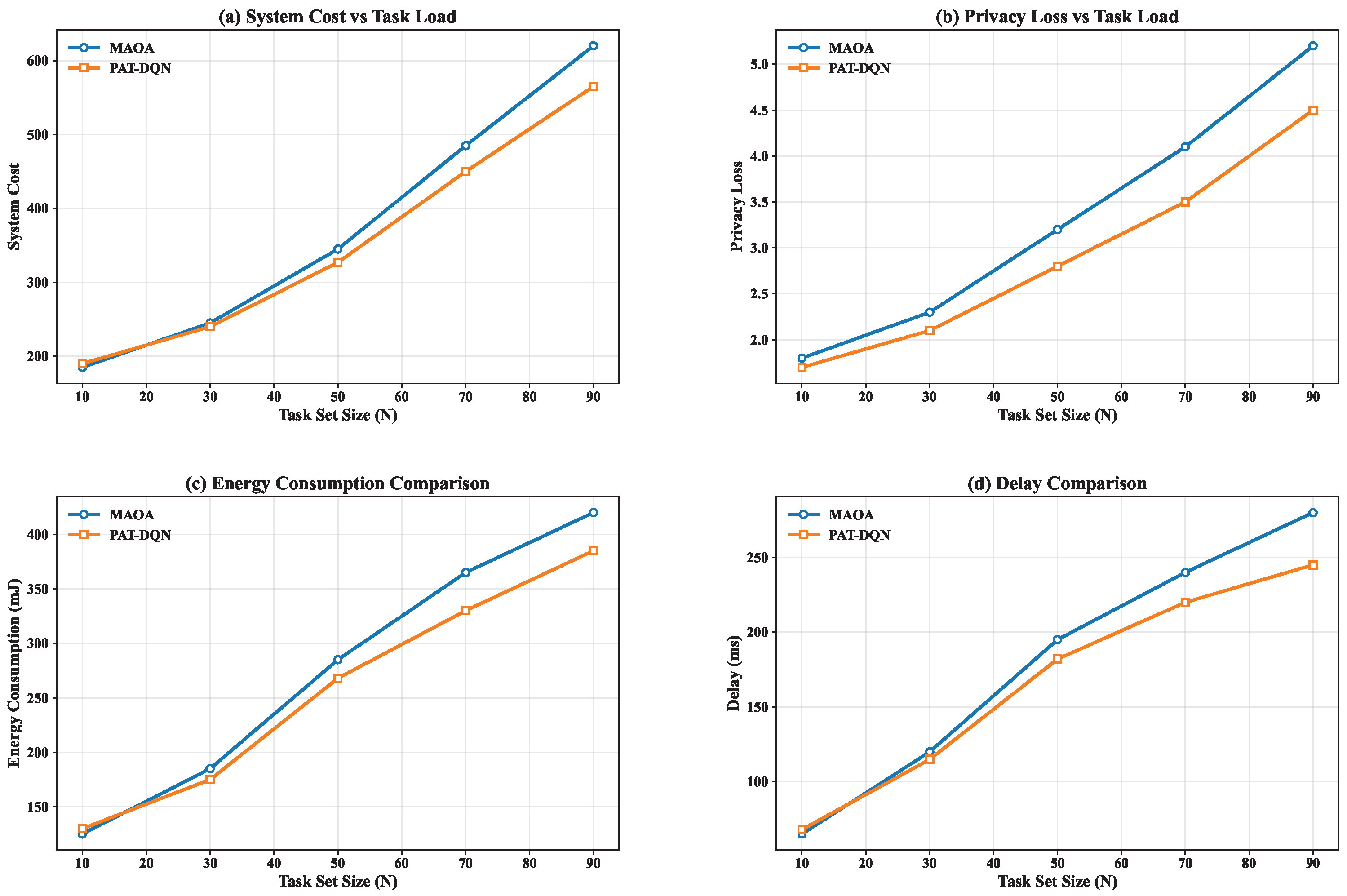

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithms, we implement and compare the Markov Approximation Online Algorithm (MAOA) with the Privacy-Aware DQN-based Task Scheduling algorithm (PAT-DQN). The evaluation focuses on convergence behavior, adaptability under dynamic conditions, and overall system performance.

7.6.1. Convergence Performance

Figure 8 illustrates the convergence behavior of MAOA and PAT-DQN under a fixed task load (N = 50). The MAOA algorithm converges rapidly within approximately 2000 iterations, benefiting from the explicit mathematical formulation of the Markov approximation framework. In contrast, PAT-DQN requires a longer training phase (around 8000 episodes) to stabilize, as it learns the optimal policy through environmental interactions without prior system modeling. However, once trained, PAT-DQN achieves a 5.3% lower average system cost than MAOA, demonstrating its superior ability to discover more efficient scheduling strategies in complex state spaces.

7.6.2. Performance Under Dynamic Task Loads

Figure 9 shows the performance of both algorithms under varying task loads (N from 10 to 90). As the task load increases, both algorithms exhibit rising system costs and privacy losses, but PAT-DQN maintains a more stable privacy-cost trade-off. Specifically, when N = 90, PAT-DQN reduces the privacy loss by 12.7% compared to MAOA while achieving comparable system costs. This advantage stems from PAT-DQN’s capacity to learn non-myopic policies that anticipate future states, thereby making more strategic decisions that mitigate cumulative privacy leakage.

7.6.3. Adaptability to High-Mobility Scenarios

We further test both algorithms under accelerated mobility scenarios where vehicle speed varies between 80 and 120 km/h. As shown in

Table 4, PAT-DQN outperforms MAOA in all key metrics under high mobility conditions, reducing the average delay by 8.1% and energy consumption by 6.5%, while maintaining a 14.2% lower privacy loss and 19% fewer handovers. The 14.2% reduction means that the attacker’s uncertainty about the vehicle’s real - time location and historical trajectory is significantly increased. This makes it difficult for the attacker to accurately infer the vehicle’s driving route, stop - over points, and service usage preferences. For the 19% reduction in handover frequency, its practical significance lies in weakening the attacker’s ability to triangulate vehicle trajectories based on continuous server access sequences. Frequent handovers generate dense and continuous access records, which provide the attacker with rich sequential location clues. By reducing handovers by 19%, the number of effective location points that the attacker can use for inference is reduced proportionally. The explicit state representation of vehicle dynamics (speed, acceleration) in PAT-DQN’s state space enables it to better anticipate handover events and channel variations, leading to more robust performance.

7.6.4. Computational Overhead Analysis

Although PAT-DQN’s training phase is computationally intensive, its online inference time is only 3.2 ms per decision, which is comparable to MAOA’s 2.8 ms and perfectly suitable for real-time scheduling in vehicular environments. The training can be performed offline or in a simulated environment, making PAT-DQN practical for real-world deployment.

To clarify, the online inference time was measured on the simulation platform with an Intel i5-11400 CPU (2.6 GHz) and 16 GB RAM, without GPU acceleration for inference, to emulate the computational capabilities of typical edge devices. The NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080Ti GPU was used exclusively for offline training of the DQN model, not for online decision-making. The reported time represents the average latency of the neural network forward pass, excluding communication delays.

Regarding computational complexity, MAOA exhibits a per-iteration complexity of due to localized strategy updates, and it converges geometrically fast with iterations to reach an -approximate solution. For PAT-DQN, the online inference involves a forward pass through a lightweight neural network with fixed layers, resulting in complexity, where is the state dimension and is the action space size. This design ensures that both algorithms can meet the low-latency requirements of dynamic vehicular environments.

7.6.5. PAT-DQN Ablation Study

To validate the necessity and rationale of key design choices in the PAT-DQN algorithm, this subsection presents two sets of ablation experiments: (1) an ablation analysis of crucial components in the state representation, and (2) a performance comparison among variants of deep reinforcement learning architectures. The experiments are conducted under a high-mobility scenario (80–120 km/h) with N = 50 tasks. All results are averaged over 10 independent runs.

The state representation (Equation (

31)) forms the basis for the reinforcement learning agent to perceive the environment. To verify the necessity of each state component, we compare four configurations: S1 (complete state), S2 (removing acceleration

), S3 (removing server loads

), and S4 (removing the virtual queue

).

Table 5 presents the performance of these four configurations on four key metrics: system cost, privacy loss, average delay, and energy consumption.

Table 5 demonstrate that the complete state representation is fundamental for achieving an efficient privacy-performance trade-off. Removing acceleration information caused a significant increase in system cost and delay, verifying that perceiving instantaneous vehicle dynamics is crucial for anticipating network handovers and optimizing offloading timing in high-mobility vehicular environments. Removing server load information led to the most severe performance degradation, with a 31% surge in system cost, reflecting that ignoring server heterogeneity in real-world edge deployments results in severe resource contention and energy waste. Most importantly, while removing the virtual queue state only mildly affected system cost, it caused privacy loss to soar by 53%. This directly proves that explicitly incorporating the long-term privacy constraint (Lyapunov queue) into the state space is decisive in guiding the agent to proactively manage the privacy budget and avoid exposing regular patterns.

To evaluate the suitability of different DQN variants in the context of our problem, we compare three mainstream architectures: Double DQN, Dueling DQN, and Prioritized Experience Replay. All architectures are trained and tested using the same complete state representation S1, with results shown in

Table 6.

The DQN architecture comparison reveals that Double DQN offers the best balance between privacy protection and stability. Although Prioritized Experience Replay slightly outperformed on system performance metrics (≈3–4% lower cost), it incurred higher privacy loss (+12.5%) and significantly reduced training stability. In vehicular networks, where safety and reliability are paramount, stable and predictable privacy guarantees hold greater practical value than marginal performance gains. Therefore, the choice of Double DQN is justified by its robustness advantage in satisfying long-term privacy constraints, rather than merely pursuing extreme performance.

8. Discussion

While the framework effectively balances privacy and performance in tested scenarios, it has macro-level limitations. First, the mobility and task models rely on synthetic scenarios, which do not fully capture real-world complexities (e.g., dynamic traffic conditions, heterogeneous task types) that may influence the privacy-cost trade-off in practical deployments. Second, the current design focuses on single-vehicle scheduling, without addressing inter-vehicle interactions (e.g., resource competition, collaborative offloading) that are critical in large-scale vehicular networks. Third, the adaptive switching between MAOA and PAT-DQN relies on empirically derived thresholds, lacking a data-driven mechanism to adapt to highly variable environmental dynamics.

Future work will address these limitations and expand the framework’s scope. First, we will integrate real-world vehicular data (e.g., traffic logs, GPS traces) to enhance the model’s practical relevance. Second, we will extend the framework to multi-vehicle scenarios, exploring collaborative offloading and resource sharing to optimize system-wide efficiency and privacy. Third, we will investigate intelligent threshold adjustment for algorithm switching, potentially leveraging reinforcement learning to improve adaptability. Additionally, we will explore integration with 5G/6G communication technologies to support low-latency, high-reliability privacy-preserving scheduling in next-generation vehicular networks.

9. Conclusions

This paper addresses the critical challenge of historical inference attacks in vehicular edge computing, where adversaries exploit long-term task offloading patterns to infer vehicle trajectories. To counter this, we proposed a privacy-preserving online task scheduling framework with dual algorithmic approaches. The core of our approach lies in leveraging the Lyapunov optimization theory to transform the long-term privacy-cost trade-off into a series of tractable online decisions. We developed two complementary solutions: the Markov approximation-based algorithm (MAOA) for efficient near-optimal scheduling with proven convergence, and the Privacy-Aware DQN-based algorithm (PAT-DQN) that employs deep reinforcement learning for enhanced adaptability in dynamic environments.

Extensive simulations demonstrate that both frameworks effectively minimize cumulative privacy leakage while maintaining low system overhead, with PAT-DQN showing superior performance in high-mobility scenarios due to its ability to learn non-myopic policies. Crucially, the proposed frameworks are designed for practicality: they exhibit strong extensibility for heterogeneous vehicular environments with multi-domain edge infrastructures and can be seamlessly integrated into existing systems, offering viable paths for real-world deployment in intelligent transportation systems. Future work will focus on multi-vehicle collaborative scheduling, deep integration with 5G/6G communication technologies, and further exploration of deep reinforcement learning techniques for privacy-preserving edge computing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and A.Y.; methodology, E.C.; software, H.D.; validation, E.C. and H.D.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, E.C.; resources, E.C.; data curation, E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C.; writing—review and editing, A.Y.; visualization, E.C.; supervision, A.Y.; project administration, A.Y.; funding acquisition, A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported partially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [61972096, 61771140, 61872088, 61872090], the University-Industry Cooperation Project of Fujian Provincial Department of Science and Technology (2022H60250), and by the Educational Science Research Fund of Fujian Province (FJJKBK24-008).

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arthurs, P.; Gillam, L.; Krause, P.; Wang, N.; Halder, k.; Mouzakitis, A. A Taxonomy and Survey of Edge Cloud Computing for Intelligent Transportation Systems and Connected Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 6206–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, M.; Yu, M.; Jan, M.A.; Lan, D.; Taherkordi, A. Mobility-Aware Multi-Hop Task Offloading for Autonomous Driving in Vehicular Edge Computing and Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 2169–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, X.; He, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Zhan, S.; Lu, G.; Dustdar, S. Computation offloading in resource-constrained multi-access edge computing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 10665–10677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Hu, B.J.; Xia, E. Dependency-Aware Task Offloading and Service Caching in Vehicular Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 13182–13197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Patel, M.; Sabella, D.; Sprecher, N.; Young, V. Mobile edge computing—A key technology towards 5G. ETSI White Pap. 2015, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Sun, H.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q. Edge Computing-An Emerging Computing Model for the Internet of Everything Era. Jisuanji Yanjiu Yu Fazhan/Comput. Res. Dev. 2017, 54, 907–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Tomar, A.; Hazra, A. Edge computing for industry 5.0: Fundamental, applications, and research challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 19070–19093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, D.; Jin, D.; Chen, S. Vehicular Fog Computing: A Viewpoint of Vehicles as the Infrastructures. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 65, 3860–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Loo, J.; Yang, D.; Xiao, L. Joint Computation and Communication Design for UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing in IoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 5505–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, X. Energy-Minimization Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for Mobile Edge Computing in NOMA Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 16001–16016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, L.; Song, L.; Xu, J. Risk-Aware Edge Computation Offloading Using Bayesian Stackelberg Game. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2020, 17, 1000–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, A.M.A.; Hussain, F.K.; Hussain, O.K. Task offloading in vehicular fog computing: State-of-the-art and open issues. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 133, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; He, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, J. A survey of privacy-preserving offloading methods in mobile-edge computing. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2022, 203, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Tao, J.; Pastor, G.; Xiao, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Ylä-Jääski, A. Folo: Latency and Quality Optimized Task Allocation in Vehicular Fog Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 4150–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Mehrabi, A.; Xiao, Y.; Ylä-Jääski, A.; Ji, Y. Chameleon: Latency and Resolution Aware Task Offloading for Visual-Based Assisted Driving. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 9038–9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Ai, B.; Mumtaz, S. Task Offloading for Vehicular Fog Computing under Information Uncertainty: A Matching-Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Wireless Communications Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Tangier, Morocco, 24–28 June 2019; pp. 2001–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liao, H.; Zhao, X.; Ai, B.; Guizani, M. Reliable Task Offloading for Vehicular Fog Computing Under Information Asymmetry and Information Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 8322–8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Kong, M.; Li, Q.; Sun, X. Contract-Based Computing Resource Management via Deep Reinforcement Learning in Vehicular Fog Computing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 3319–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, P.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mumtaz, S.; Rodriguez, J. Computation Resource Allocation and Task Assignment Optimization in Vehicular Fog Computing: A Contract-Matching Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 3113–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.A.; Dang, T.N.; Yaqoob, I.; Manzoor, A.; Hussain, R.; Khan, A.; Hong, C.S.; Salah, K. A Novel Contract Theory-Based Incentive Mechanism for Cooperative Task-Offloading in Electrical Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 8380–8395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, J.; Jin, R.; Dai, H. Privacy-Aware Offloading in Mobile-Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2017—2017 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Singapore, 4–8 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, H.; Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Geng, L.; Liu, Y. Privacy-Aware Online Task Offloading for Mobile-Edge Computing. Wirel. Algorithms Syst. Appl. 2020, 12384, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jin, R.; Dai, H. Deep PDS-Learning for Privacy-Aware Offloading in MEC-Enabled IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 4547–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, J. Privacy-preserved federated learning for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 8423–8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; Nie, Y. Secure and efficient computing resource management in blockchain-based vehicular fog computing. China Commun. 2021, 18, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Shen, G.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, K.; Kong, X.; Li, J. Asynchronous Federated Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Dependency Task Offloading for UAV-Assisted Vehicular Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 31561–31574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Guan, Z.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. A blockchain based privacy-preserving federated learning scheme for Internet of Vehicles. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, B.; Yu, Z.; Cao, X.; Alexandropoulos, G.C.; Zhang, Y.; Yuen, C. Computation Pre-Offloading for MEC-Enabled Vehicular Networks via Trajectory Prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.176814. [Google Scholar]

- Min, M.; Wan, X.; Xiao, L.; Chen, Y.; Xia, M.; Wu, D.; Dai, H. Learning-Based Privacy-Aware Offloading for Healthcare IoT With Energy Harvesting. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 4307–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Huang, W.; Liu, T.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y. PPO2: Location Privacy-Oriented Task Offloading to Edge Computing Using Reinforcement Learning for Intelligent Autonomous Transport Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 24, 7599–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadvand, H.; Foroutan, F. Latency and Privacy-Aware Resource Allocation in Vehicular Edge Computing. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.02804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.R.; Raza, S.; Misic, V. A Narrative Review of Identity, Data, and Location Privacy Techniques in Edge Computing and Mobile Crowdsourcing. Electronics 2024, 13, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.Q.; Tang, J.; La, Q.D.; Quek, T.Q.S. Offloading in Mobile Edge Computing: Task Allocation and Computational Frequency Scaling. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2017, 65, 3571–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Letaief, K.B. Delay-optimal computation task scheduling for mobile-edge computing systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Barcelona, Spain, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 1451–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liew, S.C.; Shao, Z.; Kai, C. Markov Approximation for Combinatorial Network Optimization. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2013, 59, 6301–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).