Abstract

Despite growing research on sustainable aviation, multi-airport systems, and environmentally constrained capacity allocation, critical gaps persist. Existing studies often treat passenger choice, airline competition, and airport regulation in isolation, or evaluate environmental policies such as carbon taxation only as macro-level constraints. Consequently, the endogenous feedback among pricing, capacity reallocation, and regulatory intervention in shaping equilibrium outcomes within multi-airport systems remains underexplored, particularly within a unified dynamic framework that links low-carbon policies to operational decision-making. This study develops such a dynamic framework to support the sustainable transition of carbon-constrained multi-airport regions. Focusing on the Beijing–Tianjin multi-airport system and China’s “Dual Carbon” goals, we construct a three-layer iterative equilibrium game integrating passenger airport choice (modeled using a multinomial logit specification), airline capacity reallocation (formulated as an evolutionary game internalizing carbon taxes), and airport slot regulation (implemented through a multi-objective mechanism balancing economic revenue, hub connectivity, and environmental performance). An agent-based simulation of the Beijing/Tianjin–Nanchang route demonstrates robust convergence to a stable systemic equilibrium. Intensified competition reduces fares and improves accessibility, while capacity shifts from higher-cost Beijing airports to Tianjin Binhai Airport, whose market share rises from 10.6% to 34.0%. Airport utilization becomes more balanced, total airline profits increase slightly, and both total and per-passenger CO2 emissions decline, indicating improved carbon efficiency despite demand growth. The results further identify a range of carbon-tax levels that jointly promote emission reduction and traffic rebalancing with limited profit loss.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth in air transportation demand has led to the emergence of multiple representative cases of Multi-Airport Systems (MAS) across various countries, including London in the United Kingdom, New York in the United States, and the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region in China [1,2]. MAS play a crucial role in alleviating traffic congestion and enhancing regional hub capacity. Taking the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei airport cluster as an example, Beijing Capital International Airport, Beijing Daxing International Airport, and Tianjin Binhai International Airport jointly constitute a typical MAS serving the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration. These airports, on the one hand, assume differentiated functions such as international hubs, transfer nodes, and regional hubs, while on the other hand, they engage in intense competition for passengers and route resources in several overlapping markets [3]. Major multi-airport regions in China, such as the Greater Bay Area, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, have exhibited notable differences in competitive–cooperative relationships, network topology evolution, and sustainability pathways [4]. Existing studies from the perspectives of air transport network structure and airport green efficiency suggest the presence of a potential “Matthew effect” within MAS, characterized by the agglomeration of stronger airports and the marginalization of weaker ones. Nevertheless, under appropriate policy environments and functional positioning, small and medium-sized airports may still achieve “catch-up” in terms of green efficiency and network roles [5].

Meanwhile, carbon emissions from the aviation sector have increased rapidly, accounting for approximately 3% of the 15% contributed by the transport sector [6], and global emissions are projected to continue rising through 2026. Existing studies indicate that, if current trends persist, global aviation CO2 emissions are unlikely to align with the temperature control targets set forth in the Paris Agreement [7]. Scenario analyses for China’s civil aviation sector further suggest that large-scale adoption of sustainable aviation fuels, accelerated fleet renewal with next-generation energy-efficient aircraft, and improvements in operational efficiency may enable the sector to reach a peak in emissions and subsequently achieve substantial reductions around the mid-21st century [8].

The primary objective of this study is to develop a unified analytical framework for examining capacity allocation and regulatory interaction in a multi-airport system under low-carbon policy constraints. Rather than predicting the operational outcomes of specific routes, this research focuses on capturing the interaction mechanisms and co-evolutionary dynamics among passenger airport choice, airline capacity allocation, and airport slot regulation.

The novelty of this study is threefold. First, it proposes a three-layer iterative equilibrium game model that integrates passenger behavior, airline decision-making, and airport regulatory responses within a closed feedback loop. Second, environmental policy objectives are embedded directly into the operational decision mechanisms, allowing carbon regulation to influence strategic behavior rather than being treated as an exogenous outcome. Third, the framework is designed to analyze system-level coordination and policy trade-offs in multi-airport regions, extending existing studies that typically address these components in isolation.

Overall, the proposed framework provides a systematic approach to identifying the unique systemic equilibrium in terms of prices, capacity allocation, and slot outcomes under the dual objectives of market efficiency and carbon reduction, thereby offering managerial and policy-relevant insights into sustainable resource configuration in multi-airport systems.

2. Literature Review

A growing body of literature has examined the overall evolution and sustainability of Multi-Airport Systems (MAS) from the perspectives of competitive landscapes, system compatibility, and regional resilience. Xin Chen et al. demonstrated through a multi-stage dynamic game model that differentiated subsidy strategies can significantly enhance the alignment between airport network configurations and functional positioning within airport clusters [9]. Sun et al. conducted a systematic review of the concept, development patterns, and research challenges of Multiple Airport Regions (MARs), emphasizing that, under increasingly stringent environmental constraints and rising social equity concerns, multi-airport governance has shifted from simple capacity expansion toward a comprehensive balance among efficiency, resilience, and sustainability [10]. Studies employing panel spatial models further indicate that airports within the same MAR exhibit significant spatial correlations and spillover effects in terms of passenger flows, route distribution, and economic outputs [11]. Research adopting topological and complex network perspectives has revealed that China’s multi-airport region networks display pronounced “small-world” and “scale-free” characteristics, with key hub nodes exerting dominant influence over system robustness and congestion risks [12]. From a developmental perspective, Wu et al., using evolutionary game theory, uncovered a nonlinear relationship between subsidy intensity and coordinated development among airports under homogeneous competitive environments [13]. Sun et al. proposed the Multi-Airport Region Resilience Index (MARRI), which evaluates the performance of cross-airport systems under disruptions from the dimensions of structure, operation, and recovery capability, providing a framework for assessing the integrated resilience of MAS in regions such as Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei [14].

Regarding flight scheduling and capacity allocation under capacity constraints, existing research has developed a variety of optimization and game-theoretic models at the levels of single airports, airport networks, and multi-airport systems. Ribeiro et al., based on the IATA Worldwide Slot Guidelines, proposed a single-airport slot optimization model consistent with “grandfather rights,” providing a mathematical foundation for resource allocation under traditional regulatory frameworks [15]; Zografos and Jiang introduced a bi-objective slot scheduling model that incorporates both total slot displacement minimization and fairness in allocation among airlines, thereby depicting the efficiency–equity trade-off frontier at congested airports [16,17]. In the context of coupling slot scheduling with environmental constraints, Feng et al. formulated a bi-objective slot scheduling model considering both scheduling efficiency and noise mitigation, as well as an integrated slot allocation model designed for noise reduction in the “temporal–spatial” dimension [18,19], Subsequent work by Feng and Hu further incorporated carbon emissions, noise, and taxi–takeoff–landing coordination into a unified gate–runway joint scheduling framework [20]. In response to the capacity constraints and demand imbalance observed at Chinese airports, Hu et al. conducted a quantitative assessment of airport capacity and air transport demand in China, noting that traditional single-airport-centered capacity management is insufficient for the holistic optimization needs of multi-airport systems [21]; Follow-up studies developed an “efficiency–equity” trade-off model under given airspace and airport capacity conditions at the MAS level, offering theoretical foundations and numerical evidence for cross-airport capacity and traffic allocation [22]. Building upon this foundation, Liu and Hu, from the perspectives of airport networks and multi-airport systems, respectively, constructed network slot allocation models that incorporate capacity uncertainty, connectivity requirements for connecting flights, and cross-airport coordination constraints, further underscoring the importance of unified slot and route allocation at the MAS level [23,24].

From a micro-level game-theoretic perspective, frequency competition and strategic interactions among airlines within a multi-airport system also constitute key mechanisms influencing the spatial distribution of routes and capacity. Zhang et al. developed a flight frequency competition model for airlines within a coordinated airport network, illustrating how carriers adjust their flight frequencies and network configurations in response to given slot structures and coordination rules [25]. Related studies indicate that under conditions involving grandfather rights, use-it-or-lose-it rules, and imperfect competition, airlines may employ strategies such as slot hoarding and marginal flight adjustments to influence slot allocation outcomes, thereby exacerbating resource imbalance and operational inefficiencies within a multi-airport system [17,26]. Meanwhile, the commissioning of newly built airports (e.g., Beijing Daxing International Airport) reshapes bilateral airport–airline relationships, route division, and welfare distribution. Using the case of Beijing’s new airport, Hou et al. examined changes in prices, frequencies, and welfare within a multi-airport system and highlighted that properly designed capacity allocation schemes and incentive mechanisms can help reconcile efficiency and social welfare objectives in MAS operations [27].

Under the constraints of the national “dual-carbon” targets, the carbon reduction mechanisms in the civil aviation sector and the behavioral responses of industry stakeholders have become prominent research topics in recent years. Zhang et al. developed an evolutionary game model involving the government, major airlines, and small- and medium-sized airlines to analyze the evolutionary pathways and stable strategies of emission-reduction behaviors under a hybrid carbon trading–carbon tax mechanism, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for the design of mixed policies [28]. Subsequent studies, based on stochastic evolutionary game frameworks, incorporated policy uncertainty and carbon price volatility to explore feasible pathways for achieving emission-reduction targets in the aviation sector under hybrid regulatory mechanisms [29]. Other research focusing on the promotion of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) constructed an evolutionary game model between the government and airlines to examine the incentive effects of carbon trading and subsidy policies on SAF adoption [30]. From the perspectives of emission accounting and environmental performance evaluation, Zhu et al. and Jia et al. conducted a series of studies examining the spatial distribution characteristics of aircraft CO2 emissions across different airports, along with the uncertainties and driving factors involved in emission assessment [31,32]. These findings provide essential parameter support for explicitly incorporating emission costs into route and capacity allocation models.

Sustainability assessment frameworks for airports and multi-airport systems provide essential tools for integrating green development objectives into capacity and traffic management. Jia et al. developed a composite Airport Sustainability Evaluation Index (ASEI) covering environmental, operational, economic, and social dimensions, revealing the trade-offs among these aspects in multi-airport case studies [33]. Their subsequent review highlighted inconsistencies in indicator design, limited triple-bottom-line integration, and weak cross-airport comparability in existing research. For tourism-dependent regions, Karagkouni et al. proposed an evaluation framework linking airport environmental performance with regional tourism reliance [34]. Although studies on sustainable airport development have grown rapidly, truly holistic assessments integrating economic, environmental, and social dimensions remain scarce, particularly those examining how multi-airport systems can achieve green transition through coordinated capacity and traffic allocation [35].

Prior research in transportation has systematically explored emission accounting and reduction assessment methods. For urban public transit, Owais developed an emission accounting framework for mass rapid transit, integrating service levels and travel substitution effects to enhance practicality and comparability [36]. From a regulatory perspective, Owais also optimized network layouts for remote sensing monitoring to improve detection of high-emission vehicles [37]. Although air transport differs in system boundaries and emission structures, these studies offer methodological insights—particularly in baseline-project comparison and embedding governance objectives—that inform this paper [36,37].

Existing literature has established a foundation for understanding the operational mechanisms and green governance of Multi-Airport Systems (MAS) across competitive structures, capacity optimization, and sustainability evaluation. However, critical research gaps persist:

- Most capacity/slot models focus on single or abstract airport networks, lacking systematic analysis of cross-airport route-capacity coordination for typical MAS (e.g., Jing-Jin-Ji), especially under the Dual Carbon Goals and market-based mechanisms.

- Evolutionary Game Theory studies on civil aviation carbon reduction are macro-focused, often failing to couple with specific MAS coordination decisions or seeking the unified optimum of efficiency, equity, and emission reduction.

- MAS-level capacity and route planning lack full integration of sustainability metrics; green goals are largely treated as constraints rather than being embedded in the objective function.

To address these gaps, this paper studies the Jing-Jin-Ji MAS within the dual context of the “Dual Carbon” goals and aviation market reform. We construct a multi-agent game model, integrating capacity constraints, carbon costs, and environmental targets into a route-capacity coordination framework. The aim is to find the optimal synergy between efficiency, equity, and emission reduction.

This study bridges the disconnect between MAS structural analysis and specific capacity-fleet decision models, offering an actionable theoretical basis for green governance and policy design in China’s MAS by coupling carbon reduction policies with market-based slot allocation mechanisms.

3. Methodology: A Three-Layer Iterative Equilibrium Game Model

To address these challenges, this research establishes a Three-Layer Progressive Iterative Equilibrium Game Model for route-level capacity configuration. This model systematically deconstructs the complex operational process into three coupled, progressive stages, creating a complete “Prediction—Decision—Regulation—Feedback” analytical loop. The inherent complexity is rooted in the strategic interactions of multiple agents: Passengers, whose cross-regional choices are driven by Generalized Travel Cost (fare + ground access); Airlines, who maximize profits by balancing capacity deployment with network planning and MAS cost structures; and Airport Managers, who must guide slot allocation—via market or administrative means—to align with capacity limits and strategic, revenue, and green development goals.

The model is structured across three primary layers:

Layer 1 (Passenger Choice and Dynamic Pricing Equilibrium) focuses on market demand formation by using fine-grained geographical zoning and competitive pricing simulation to endogenously determine equilibrium prices and differentiated passenger flows.

Layer 2 (Competitive Capacity Allocation Game Among Airlines) is a non-cooperative game where airlines simultaneously seek optimal, profit-maximizing capacity deployment given the Layer 1 market environment.

Layer 3 (Multi-Objective Elastic Slot Allocation Mechanism) represents the airport manager’s regulatory role, performing a unified, multi-objective allocation prioritizing short-term revenue, long-term strategy, and environmental performance. Crucially, the introduction of the Iterative Equilibrium System allows the supply outcome from Layer 3 to feed back into the Layer 1 pricing mechanism, realistically simulating dynamic market response. The system iteratively solves for a Fixed Point where all participant strategies stabilize. This framework’s breakthrough innovation is its first-time integration of fare formation, capacity migration, and green regulation within a unified dynamic system.

3.1. Basic Assumption

To ensure the logical rigor and analytical focus of the model, this study proposes the following fundamental assumptions and defines all key symbols in Table 1.

Table 1.

Table of Key Symbol Definitions for the Model.

Fundamental Assumptions:

H1.

Rationality of Participants: Airlines and airports are assumed to be rational economic entities, aiming to maximize their total profit and composite utility, respectively.

H2.

Information Structure: Key parameters in the game process (e.g., airport charges, capacity, and scoring rules) are treated as common knowledge.

H3.

Passenger Heterogeneity and Choice Behavior: Market passengers are spatially heterogeneous, originating from different “geographical zones.” Furthermore, passengers make decisions based on maximizing their travel utility, and their choice set includes all operating airports plus an “external option,” which ensures the elasticity of the total air transport demand.

H4.

Green Policy Embedding: The carbon tax is internalized into the airlines’ operational costs.

H5.

Iterative Equilibrium: The model assumes that the iterative process converges to a stable equilibrium point within a short-term operational cycle.

H6.

Step-wise Adjustment: Referencing the 2023 Annual Report of the China Civil Aviation Operation Control Center (p. 21), airlines’ single capacity adjustment is constrained to be no more than 30% of their total capacity.

In this study, aviation carbon emissions are quantified using the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standard accounting methodology. For each route, per-flight fuel consumption is estimated based on great-circle distance and representative aircraft type, employing ICAO’s empirically calibrated fuel-burn functions, which incorporate typical operational conditions such as average load factors and aircraft performance.

CO2 emissions per flight are derived by applying the ICAO emission factor of 3.16 kg CO2 per kilogram of jet fuel. Route-level emissions are aggregated by multiplying per-flight emissions by the scheduled frequency, and system-wide emissions are obtained by summing across all routes.

This widely accepted approach ensures consistency with international carbon accounting standards [40]. In the proposed three-layer game model, the calculated emissions are embedded into airline cost functions via a carbon tax and serve as a key criterion in airport slot allocation, thereby endogenously linking emission outcomes with airline operational decisions and airport regulatory responses.

3.2. Model Building

3.2.1. First Layer: Passenger Choice and Generalized Travel Cost

This layer is modeled as a multi-actor non-cooperative Accessibility–Price Game. For modeling convenience, we treat the representative fare at each airport as an airport-level decision variable reflecting the joint outcome of airport–airline interactions for ticketing services, while passengers choose among PEK, PKX, and TSN based on fare levels, ground accessibility, and flight availability, following individual utility maximization.

It should be noted that passenger choice is modeled at an aggregate behavioral level. Fare and generalized travel time (including ground accessibility and perceived congestion) are selected as core explanatory variables because they are observable, quantifiable, and widely recognized in the literature as dominant drivers of airport choice. Other subjective and heterogeneous factors—such as individual preferences regarding transfers, waiting time, or comfort—are implicitly captured through the utility function and its sensitivity parameters, rather than being modeled as explicit decision criteria.

Any fare adjustment by one airport affects passenger utility through the choice model, thereby reshaping competitive dynamics. For example, if PKX adopts a lower-fare strategy relative to PEK, travelers from southern Beijing or Langfang—facing shorter ground travel times—are more likely to shift to PKX, reducing demand and revenue at PEK. Through price competition, airports influence passengers’ generalized travel cost, and the resulting passenger distribution feeds back to airline revenue and capacity utilization, forming a typical non-cooperative Nash game.

The passenger layer is modeled using a Multinomial Logit (MNL) framework grounded in Random Utility Theory. The model assumes that travelers select the airport offering the highest overall utility among available alternatives, with choice outcomes expressed as explicit probabilities. Here, “highest overall utility” refers to expected utility maximization under the Random Utility Theory framework at an aggregate level. This does not imply that individual travelers consciously evaluate all alternatives in a fully rational manner. Instead, the utility-maximization assumption serves as a behavioral approximation that links observable service attributes to probabilistic choice outcomes within the multinomial logit formulation.

Owing to its analytical tractability and smooth differentiability, the MNL model is well suited for iterative interaction with the subsequent airline capacity-adjustment module. By incorporating an outside option (e.g., “no travel”), the model also captures demand elasticity, allowing some travelers to exit the market when generalized travel costs increase. This design ensures that the passenger-demand outputs remain economically consistent and form a closed feedback loop with the upper-layer game.

To ensure theoretically coherent behavioral evolution within the multi-layer framework, the following assumptions are imposed at the passenger layer:

H7 (Rationality and Utility Maximization).

Travelers behave as rational decision-makers and choose the airport that maximizes expected utility, consistent with Random Utility Theory.

H8 (Preference Heterogeneity and Independent Errors).

Unobserved preference terms ε are i.i.d. and follow a Gumbel distribution, ensuring the validity of the MNL structure.

H9 (Information Availability and Immediate Response).

At each iteration, travelers make decisions based on posted fares , perceived capacity signals , and ground access cost ; fare changes immediately affect next-round choice probabilities.

H10 (Outside Option).

A “no-travel/alternative mode” option with baseline utility is included, allowing some travelers to exit the market when utilities of all airports decline, thereby preserving demand elasticity.

These assumptions, together with the iterative solution procedure and stochastic perturbations, ensure that passenger choice probabilities evolve smoothly across iterations and feed directly into airline decision-making. As travelers evaluate fares, perceived congestion, and ground accessibility—and as capacity exhibits diminishing marginal perceived benefit—the deterministic utility of airport for passengers in zone is defined as , specified in Equation (1):

In this study, the multinomial logit model is employed as the baseline passenger choice model due to its transparency and computational efficiency. Given the iterative nature of the three-layer game framework, this parsimonious choice structure is essential to ensure stable convergence and to clearly interpret the feedback effects among passengers, airlines, and airports. Here, denotes the intrinsic attractiveness of airport ; represents its currently available capacity, and is the designed capacity benchmark. The probability that travelers in zone z choose airport i, denoted as , follows the standard logit formulation:

Because the population size varies across zones and short-term economic fluctuations may influence travel demand, the monthly demand allocated to airport i is computed as the probability-weighted sum of regional demands. The aggregate demand is therefore obtained as:

where is the population of zone z and is an economic disturbance factor ranging between 0.98 and 1.02.

3.2.2. Second Layer: Airline Evolutionary Game for Capacity Reallocation

This layer represents a multi-player capacity (flight frequency) allocation game involving three airlines K∈{A,B,C}. Because airlines in practice exhibit bounded rationality and adjust their decisions gradually through learning—rather than solving for a fully rational global optimum in one step—and because the simulation adopts an iterative mechanism (“target share → adjustment speed → approval-history correction”), this layer is modeled as an evolutionary game. It can also be interpreted as a repeated non-cooperative game with imitation, learning behavior, and adjustment inertia. In the airline capacity allocation game, flight carbon emissions are incorporated into the airline’s flight operating cost function in the form of a carbon tax. Consequently, carbon emissions no longer serve as an ex-post evaluation indicator but endogenously influence airlines’ capacity allocation decisions and strategic evolution across different airports through the cost mechanism. The main assumptions are as follows:

H11 (Total Resource Constraint).

Each airline k has a fixed number of deployable flights , which must be allocated across the three airports.

H12 (Gradual Adjustment).

Airlines do not overhaul their schedules in a single step. Instead, they adjust slowly toward an “ideal” allocation based on a predefined adjustment speed, reflecting operational rigidity and risk-control considerations.

H13 (Approval-Rate Memory).

Airlines form expectations about future approval probabilities at each airport based on past approval outcomes and adjust their application volumes accordingly.

H14 (Mixed Objective Function).

When determining target shares, airlines consider both demand distribution and per-flight profitability. Early iterations emphasize market coverage (weights 0.6/0.4 for demand/profit), while later iterations prioritize profitability (0.3/0.7), capturing learning and strategy convergence. This transition point (after iteration 15) reflects simulation results showing that supply–demand gaps typically fall below 5% after 15 iterations.

It should be noted that this paper adopts an evolutionary game framework at the airline level, which is designed to capture airlines’ day-to-day capacity allocation adjustments under given policy constraints and airport capacity conditions. The focus is on the incremental decision-making process at the flight-operation level, rather than on corporate-level strategic behaviors such as expansion, mergers and acquisitions, or market entry and exit. The latter typically occur over longer time horizons and are influenced by factors such as capital structure, regulatory approvals, and market access, which fall outside the analytical scope of this model. Therefore, the assumptions of bounded rationality and gradual adjustment employed in this study are more applicable to analyzing capacity allocation decisions in routine operational contexts within multi-airport systems.

Given bounded rationality and gradual adaptation, this layer is better characterized as an evolutionary or adaptive non-cooperative game rather than a one-shot Nash game. The simulation iteratively updates strategies until changes in allocations, prices, and utilization levels become negligible, at which point the system is interpreted as having reached an evolutionary equilibrium.

At each iteration t, airline k chooses an application vector across airports . The objective is to airlines adjust capacity applications according to a behavioral rule that jointly considers market coverage and per-flight profitability maximize subject to the total-flight constraint . Airline strategies are jointly influenced by demand signals, per-flight profitability, historical approval experience, and adjustment inertia. The per-flight profit is defined as ticket revenue minus operating cost, including fuel, crew, maintenance, airport charges, and carbon tax:

Because airlines allocate capacity in response to the relative market size and passenger demand at each airport, the airport-level demand is first normalized into a weight (Equation (5)). Airlines then evaluate their willingness to increase flights based on normalized per-flight profitability—assigning equal weights when all profits are zero—resulting in the profit-based weight (Equation (6)). To reflect behavioral randomness and the shift from demand-oriented to profit-oriented strategies over time, the final target weight is constructed with a small stochastic disturbance (Equation (7)).

Airlines also adapt their applications based on past slot-approval outcomes, summarized by the approval-rate memory term , in Equation (7). This approval history modifies the airline’s effective application preference, yielding an adjusted share , (Equation (8)). Multiplying this adjusted share by the total available flights produces the ideal allocation , (Equation (9)). Thus, in each period t, airports receive applications , from all airlines and determine the approved frequencies subject to remaining capacity constraints. The approved quantities are recorded by airlines and used to update their approval memory , which then shapes the next-period application decisions .

It should be noted that airlines’ capacity reallocation decisions in the second layer do not directly maximize operational efficiency at the expense of passenger satisfaction. Instead, their impacts on passenger welfare are endogenously constrained through the first-layer passenger choice model. Any capacity shift that increases passengers’ generalized travel cost, such as longer access time, higher congestion, or reduced service attractiveness, will be reflected in lower utility and reduced demand in subsequent iterations. Therefore, airline adjustment strategies that significantly deteriorate passenger satisfaction are penalized by market demand responses and cannot persist in equilibrium.

3.2.3. Third Layer: Airport Multi-Objective Slot Allocation Mechanism

Building on the outcomes of the first two layers, the third layer simulates how airports allocate slots once airlines submit capacity applications. Unlike the previous strategic games, this layer is not a participatory game; rather, the airport acts as the capacity allocator and evaluates each airline’s application through a multi-objective decision mechanism. Approval shares are determined by a composite score reflecting economic value, hub connectivity, and environmental cost. During the airport slot allocation phase, airport decisions are influenced not only by capacity constraints and service fee revenues but also by environmental evaluation factors related to flight carbon emission intensity. Specifically, under the premise of satisfying safety and capacity constraints, airports grant certain approval priority to flights with lower carbon emission intensity or higher passenger load factors. Thereby, they steer the system toward a low-carbon direction by adjusting flight structure rather than simply reducing flight volume.

It should be noted that the slot-allocation mechanism in this study is designed to represent the regulatory outcome of airport coordination rather than the detailed negotiation process among airlines. By abstracting from bilateral bargaining and historical precedence, the model focuses on how policy-oriented approval criteria under capacity constraints systematically affect airlines’ capacity reallocation decisions.

This mechanism not only fulfills the airport’s role as a public resource manager but also embeds environmental policies (e.g., carbon taxation) and hub-coordination objectives into the approval process, thereby influencing upstream airline behavior and downstream passenger flows. As airports pursue revenue while also bearing hub-coordination and environmental responsibilities, the slot-approval rule incorporates three objectives simultaneously. The economic component captures short-term revenue contributions through landing and service charges, weighted by coefficients . The connectivity component accounts for the airline’s network value at the airport, incentivizing carriers with stronger hub effects. The environmental component reflects the airport’s carbon responsibility in operations, such that higher carbon taxes increase environmental penalties and reduce approval priority. Upon receiving applications , from all airlines in period t, the airport decides the approved frequencies , ensuring that total approvals do not exceed the remaining available capacity:

In the approval process, airports balance three dimensions—economic contribution, hub value, and environmental cost. These are represented, respectively, by the economic term , the connectivity term , and the environmental term :

Under capacity constraints, the airport’s multi-objective decision problem can be written as a composite utility maximization:

This formulation captures the airport’s multidimensional trade-offs: the economic component encourages approving more flights, the connectivity component prioritizes airlines that strengthen hub performance, and the environmental component penalizes high-emission operations. The weight vector determines the relative importance of these objectives.

An increase in carbon tax amplifies the airport’s green sensitivity, shifting approvals toward lower-emission and more efficient carriers. This mechanism constitutes a core innovation of the model, as it enables quantitative assessment of how environmental policies reshape capacity allocation outcomes.

It should be emphasized that environmental priority in the third layer does not imply unconditional approval of additional flights for the greenest carriers. Slot allocation is conducted under explicit capacity constraints and multi-objective evaluation criteria, where carbon emission intensity is considered jointly with operational efficiency and system-level balance.

Therefore, an airline cannot sustain unlimited expansion simply by paying carbon taxes. Excessive capacity expansion is simultaneously constrained by increasing emission costs, diminishing marginal demand due to congestion effects, and stricter competition for limited slots. The resulting equilibrium reflects a regulated balance in which environmental advantages provide relative—not absolute—priority, preventing the emergence of pay-to-pollute outcomes.

The proposed three-layer iterative equilibrium game model offers several advantages for analyzing route-level capacity allocation in multi-airport systems. First, it provides an integrated and dynamic framework that explicitly links passenger choice, airline capacity decisions, and airport regulatory behavior through endogenous feedback mechanisms. This structure enables the model to capture co-evolutionary dynamics and systemic equilibrium outcomes that cannot be observed in single-layer or static approaches. Second, environmental policy objectives are embedded directly into operational decision-making processes, through carbon taxation in airline cost functions and emission-weighted criteria in airport slot allocation, allowing for the assessment of low-carbon policies within a unified game-theoretic framework. Third, the iterative solution procedure ensures convergence to a stable equilibrium that reflects bounded rationality and adaptive behavior, making the model suitable for short- to medium-term operational analysis.

At the same time, several limitations and constraints should be acknowledged. The passenger choice module adopts a multinomial logit structure, which provides analytical tractability but abstracts from richer forms of preference heterogeneity. Airline behavior is represented as an evolutionary adjustment process based on observed profitability and approval outcomes, rather than fully forward-looking strategic optimization, which may not capture disruptive competitive strategies. In addition, the model focuses on route-level capacity reallocation under given fleet and infrastructure conditions and therefore does not explicitly account for long-term investment decisions such as fleet renewal or airport expansion.

Accordingly, the proposed framework is best suited for analyzing short-term and medium-term capacity coordination and policy impacts in multi-airport systems under relatively stable institutional settings. The results should be interpreted as system-level behavioral tendencies and comparative policy effects, rather than precise forecasts of specific operational outcomes.

4. Case Study: Beijing–Tianjin Multi-Airport Region and the Beijing–Nanchang Route

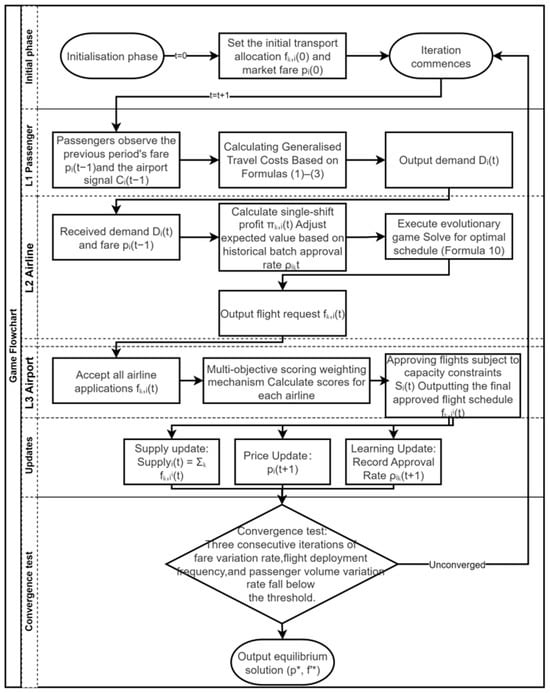

This chapter reports the numerical results of the three-layer iterative game model (passengers–airlines–airports) developed in Section 2 for the Beijing–Tianjin multi-airport system. Using the “Beijing/Tianjin–Nanchang” route as a representative case, the model is simulated with real operational data and cost parameters. An agent-based iterative algorithm is implemented in MATLAB R2024a to trace the system’s dynamic evolution and identify the resulting equilibrium.

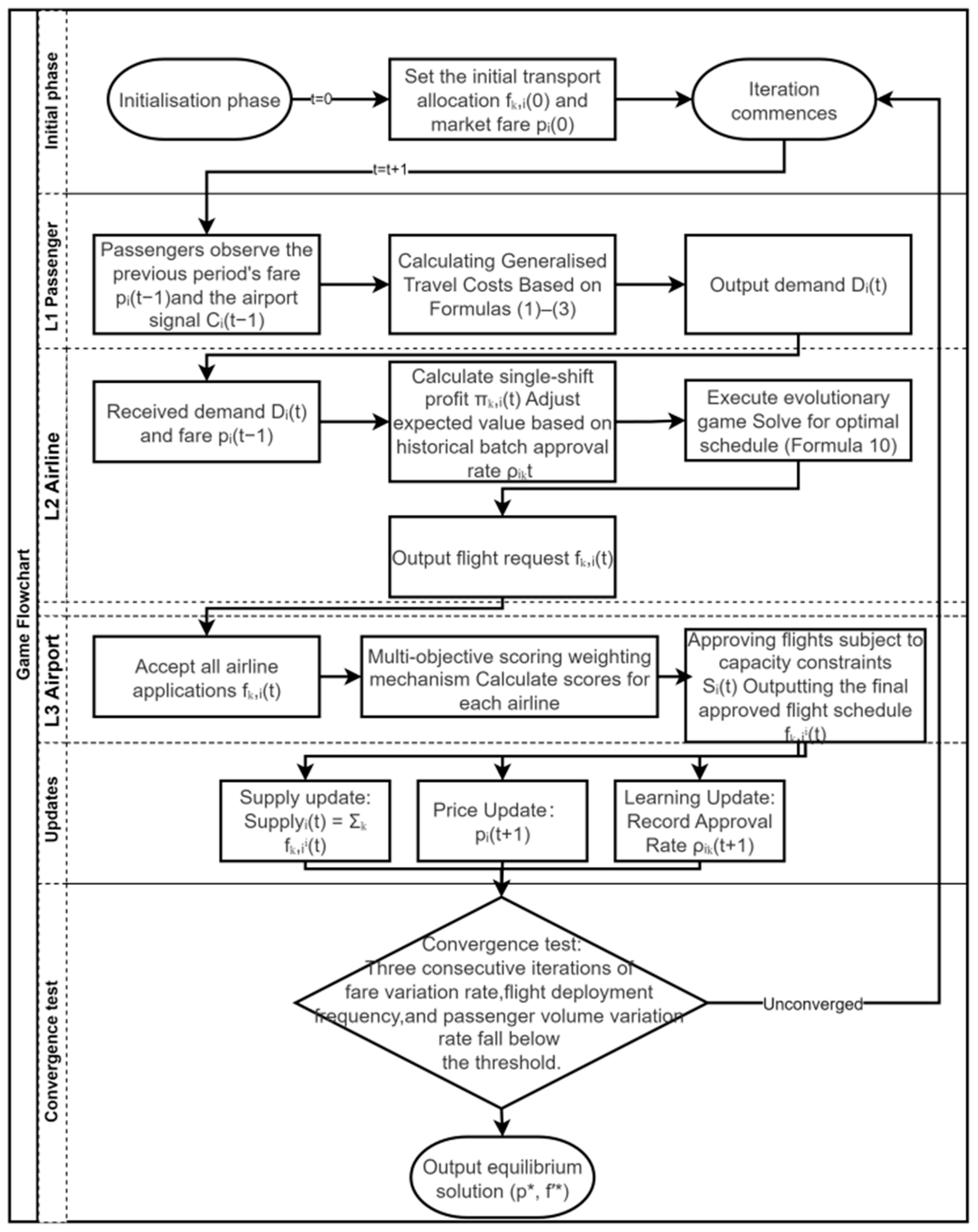

The core of the solution lies in capturing the closed feedback loop among pricing decisions, airline capacity reallocation, and airport slot approval. Starting from a non-equilibrium initial state (t = 0), the system evolves through repeated adjustment cycles, during which passengers, airlines, and airports make adaptive and myopic decisions based on the outcomes of the previous iteration. Through this process, the system gradually converges toward a stable configuration. The overall algorithmic procedure and information flow are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Algorithm Flowchart. “*” indicates equilibrium values.

1. Initialization (t = 0). The simulation starts from a non-equilibrium initial state, which represents the baseline capacity allocation and fare conditions observed in actual operations. Three representative airlines—Air China, China Eastern, and Jiangxi Air—are considered, with initial flight allocations of [117, 85, 0], [0, 122, 21], and [0, 62, 25] across Beijing Capital (PEK), Beijing Daxing (PKX), and Tianjin Binhai (TSN), respectively. Aggregated at the airport level, the initial numbers of flights are 117 for PEK, 269 for PKX, and 46 for TSN.

Initial ticket prices are taken from average market fare data reported by the Flight Master platform, ensuring consistency with observed pricing levels. The carbon tax rate γCO2 is set at 60 RMB per ton, which approximates the current conditions of China’s domestic carbon market and serves as the baseline policy parameter in the simulation.

2. Iterative adjustment (t = t + 1): Passenger response. In each iteration, passengers observe the fare levels and service-related signals determined in the previous round. Based on Equations (1)–(3), they evaluate the generalized travel cost associated with each airport, which includes ticket price, ground access cost, and congestion-related service utility, and then make probabilistic airport choices accordingly. This process generates the updated passenger demand distribution for the current period.

Ground access costs are measured using average ride-hailing expenses between major urban high-speed rail stations and each airport, while time costs are calculated based on the average hourly wage level in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Relevant intercity travel parameters are obtained from the China Railway 12306 platform and Gaode Map, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Travel Cost Parameters for the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei.

In this study, a systemic equilibrium is reached when the iterative process converges to a stable fixed point. Specifically, equilibrium is defined as the state in which the changes in passenger demand distribution, airline capacity allocation, and airport slot approval outcomes between two consecutive iterations fall below a predefined convergence threshold. This condition indicates that all agents have no further incentive to adjust their strategies given the prevailing decisions of other participants.

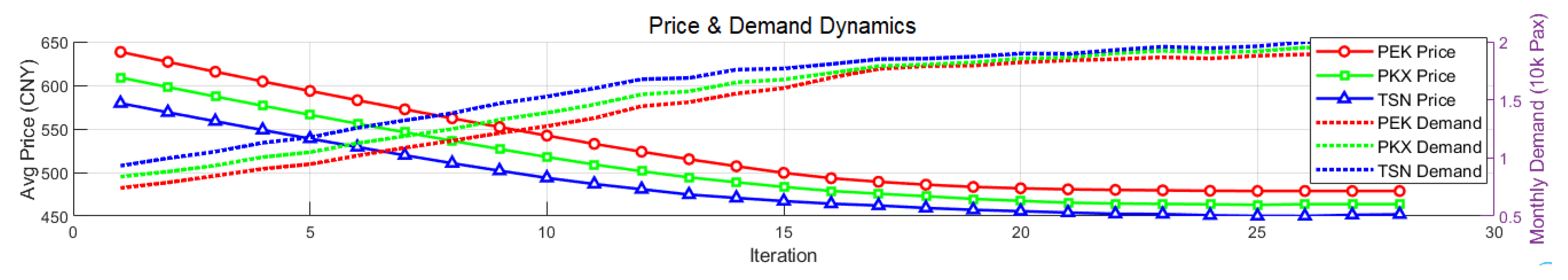

4.1. Layer 1 Results: Evolution of Ticket Prices and Demand

Layer 1 reflects the dynamic feedback between market supply–demand conditions and price formation. As shown in Figure 2, when the three-layer game begins, the initial supply (432 flights per month) is far below potential demand, resulting in a large negative supply–demand gap (approximately –33,000 passengers in iteration 1). Consequently, fares remain high across all airports (PEK = 650 RMB, PKX = 620 RMB, TSN = 590 RMB).

Figure 2.

Price and Demand Dynamics.

As the game progresses, airline capacity adjustments (Layer 2) and airport slot approvals (Layer 3) gradually reshape market supply. The intensified competition drives fares downward, with the price evolution jointly determined by the Layer-1 price update mechanism and the supply response from the lower layers. The system ultimately converges at iteration 22,The observed convergence reflects the diminishing marginal adjustments induced by the closed feedback loop among passengers, airlines, and airports. As strategy updates are incremental and bounded, the system gradually settles into a stable configuration rather than oscillating or diverging, with equilibrium fares of (PEK, PKX, TSN) = (481.6, 465.8, 453.8) RMB.

Declining fares stimulate a substantial increase in total market demand: monthly demand rises from roughly 24,800 passengers in iteration 1 to about 58,100 at equilibrium. This pattern illustrates passengers’ behavioral response to changes in generalized travel cost (fare + ground access cost). As shown in the figure, once fares fall below a threshold of approximately 540 RMB, the slope of the demand curve steepens, indicating stronger marginal utility of fare reductions and a pronounced increase in passengers’ propensity to travel.

3. Layer 2 (Airline Capacity Adjustment): Using the airport-level demand generated in Layer 1 and the previous period’s fare , airlines compute the per-flight profit , They then update their expectations based on historical approval rates , and engage in an evolutionary adjustment process to determine their ideal flight allocations according to Equation (10), producing the new set of applications . The airport service differs across the three airports, PEK (1.2) > PKX (1.0) > TSN (0.8) (million RMB per flight), making TSN the lowest-cost operating option. This reduces the marginal cost of operating at TSN and naturally shifts airline incentives toward reallocating more flights to TSN in the second-layer capacity-allocation game.

4. Layer 3 (Airport Slot Approval):Upon receiving all airline application , airports apply the multi-objective scoring and proportional allocation mechanism described in Section 3.2.3. Based on the composite score and subject to capacity constraints, each airport determines the approved flights for the current period. To reflect the functional differentiation and policy orientations within the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei hub system, the weighting schemes for economic value, connectivity, and environmental performance are set as PEK = [0.5, 0.3, 0.2], PKX = [0.4, 0.3, 0.3], TSN = [0.3, 0.3, 0.4], As a mature international hub, PEK prioritizes economic performance (weight 0.5). PKX, a newer large-scale hub, adopts a more balanced profile. Under China’s “dual-carbon” goals, improving carbon efficiency—transporting more passengers with lower emissions per revenue unit—is central to high-quality aviation development. Given fixed routes and aircraft types, higher load factors are the most direct means of reducing per-passenger emissions. According to the 2023 Civil Aviation Statistical Bulletin and industry data, TSN has demonstrated strong potential to achieve higher load factors due to its market positioning and cost advantages. The Tianjin–Nanchang route, for example, records an average load factor of 89.5%, notably higher than comparable services at PEK and PKX. Reflecting this role, TSN is assigned the highest environmental weight (0.4) and the lowest economic weight (0.3), highlighting its intended contribution to greener and more coordinated regional development.

5. Feedback and Updating: First, the system updates the actual market supply using the approved flights . Second, by comparing demand and supply in the current period, the equilibrium fare for the next iteration is adjusted based on market elasticity. Finally, each airline records its submitted and approved flights, and , to update the approval-history term for the following period.

6. Convergence Check: The system is considered converged when changes in fares, flight allocations, and passenger volumes remain below predefined thresholds for three consecutive iterations. Otherwise, the algorithm returns to Step 3 for the next update cycle.

The model is implemented in MATLAB R2024a with a maximum of 50 iterations and a convergence tolerance of 0.005.

The Beijing/Tianjin–Nanchang route is selected as the case study for three main reasons. First, its structure is representative: a multi-airport competitive origin paired with a single-destination airport, which allows a clear examination of cross-airport capacity allocation and shifting behavior. Second, the route is policy-sensitive, with stable traffic and strong responsiveness to fares and ground access costs, making it suitable for testing the impact of Logit-based passenger choice and approval-weight parameters on airline relocation. Third, the case has practical relevance: redirecting part of Beijing’s hub traffic toward regional hubs such as Tianjin aligns with the policy goals of coordinated development in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and enables clear demonstration of the effectiveness of differentiated approval and capacity policies.

Through the combined effects of differentiated airport charges (cost side), approval weights (regulatory side), and capacity flexibility (supply side, the model successfully simulates policy intervention in market dynamics and reproduces a substantial reallocation of capacity from PKX to TSN. This yields simultaneous improvements in market efficiency, passenger welfare, and environmental performance. According to the simulation logs, the system converges at iteration 22, with supply–demand gaps and other key indicators stabilizing; this equilibrium solution forms the basis of the subsequent analysis.

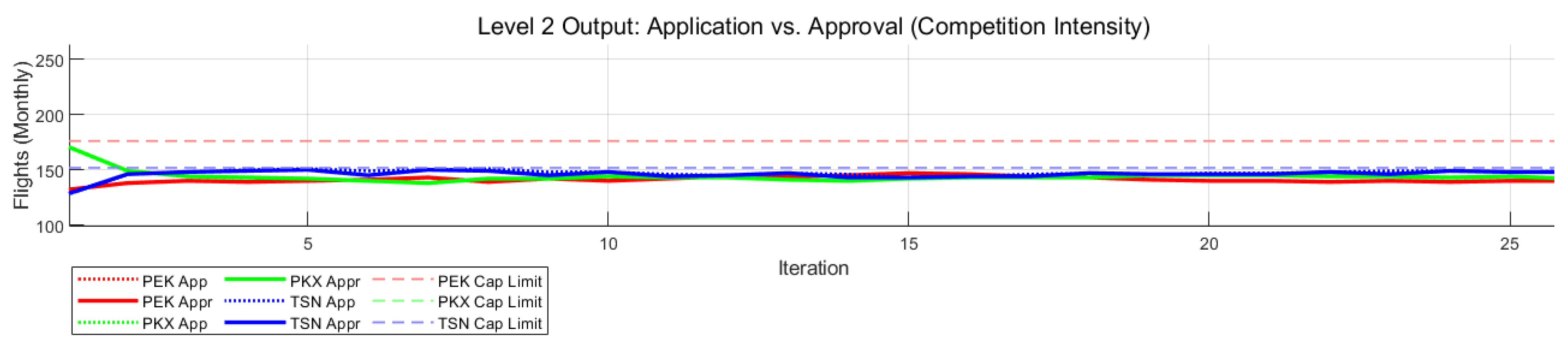

4.2. Layer 2 Results: Airlines’ Capacity Transfer Game

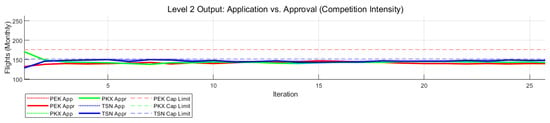

Layer 2 outputs the airlines’ capacity allocation strategies. As shown in Figure 3, the evolution of flight volumes at each airport and the corresponding market shares of the three airlines exhibit clear, convergent dynamics. During the iterative process, capacity is gradually reallocated from saturated or high-cost airports toward the more cost-efficient and synergistic hub (TSN). This redistribution leads to a stable competitive equilibrium in which capacity utilization across airports becomes more balanced.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Flight Applications and Approvals.

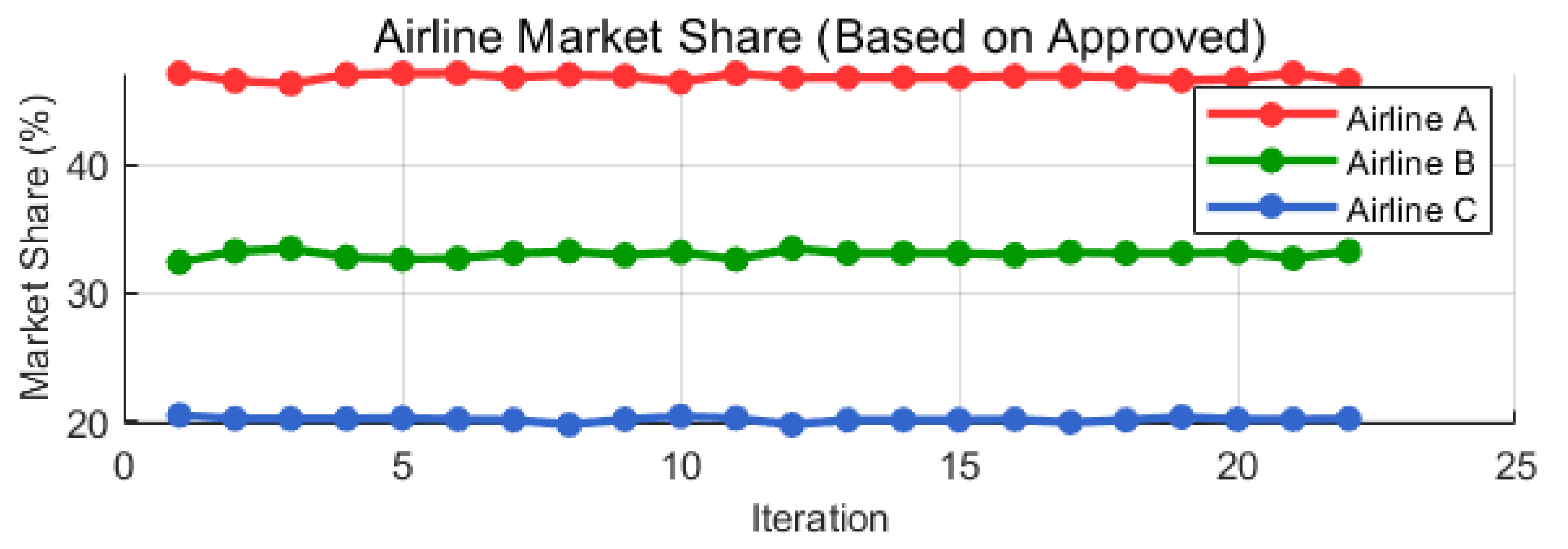

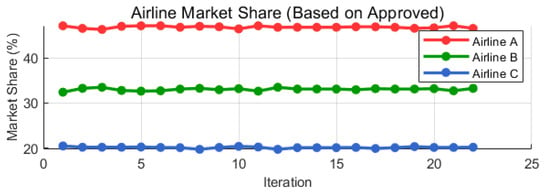

As illustrated in Figure 4, the market shares of the three airlines fluctuate slightly during the adjustment phase, reflecting the fixed total fleet size, but quickly converge to a stable structure. At equilibrium, Airlines A, B, and C hold approximately 46.5%, 33.3%, and 20.2% of the market, respectively. The stability of these shares indicates that, following price adjustments and capacity reallocation, passenger choices and airline supply decisions align to form a new proportional equilibrium.

Figure 4.

Changes in airline market share.

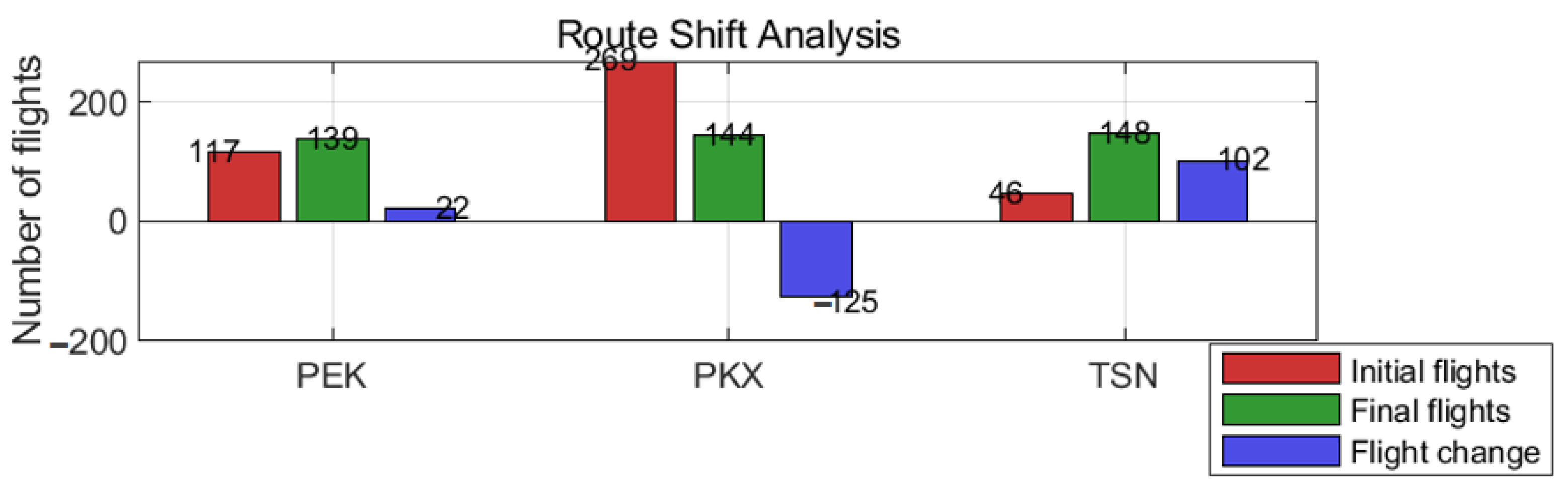

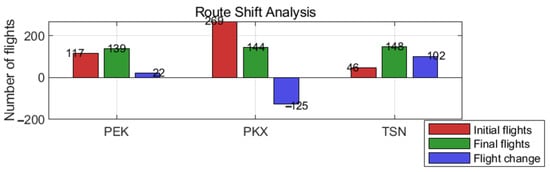

A more pronounced outcome emerges in the cross-airport redistribution of flights. As shown in Figure 5, the equilibrium results reveal a substantial restructuring of traffic across the three airports:

Figure 5.

Route Shift Comparative Analysis.

PKX: decreases from 269 to 144 flights (−125).

TSN: increases from 46 to 148 flights (+102).

PEK: increases slightly from 117 to 139 flights (+22).

These shifts clearly indicate a large-scale reallocation of capacity from PKX toward TSN. This movement is primarily driven by the profit-maximizing dynamics in Layer 2: TSN offers the lowest marginal operating cost (lowest airport charge) and benefits from a favorable approval mechanism in Layer 3. As a result, when airlines jointly consider demand, per-flight profitability, carbon tax costs, and historical approval rates, they gradually redirect capacity toward TSN, where the overall expected return is highest.

From the perspective of the payoff matrix (airline profitability), the simulation logs indicate that while PKX initially provides higher operating profits, the per-flight profits across the three airports converge toward similar levels at equilibrium. Compared with the initial state (total profit of 3.07 million RMB per day), the system ultimately reaches a higher aggregate airline profit of 3.102 million RMB per day—a net increase of 33,000 RMB. Specifically, the daily profits of Airlines A, B, and C increase by 12,300, 16,500, and 3900 RMB, respectively.

These results show that the evolutionary adjustment is not a zero-sum process; instead, the reallocation of capacity leads to a more efficient configuration that raises the overall system payoff (Table 3).

Table 3.

Initial payoff Matrix.

The Layer-2 simulation shows a clear pattern of capacity reallocation as airlines balance demand, per-flight profit, approval probability, and shifting costs. The substantial transfer of flights from PKX to TSN indicates that, under the given airport charges, hub value scores, and approval-weight settings, lower-cost and approval-friendly airports are more attractive for reallocation. This restructuring improves the overall balance of resource utilization, although it leads to a short-term reduction in benefits for certain airports, particularly PKX.

4.3. Layer 3 Results: Airport Share and Revenue Analysis

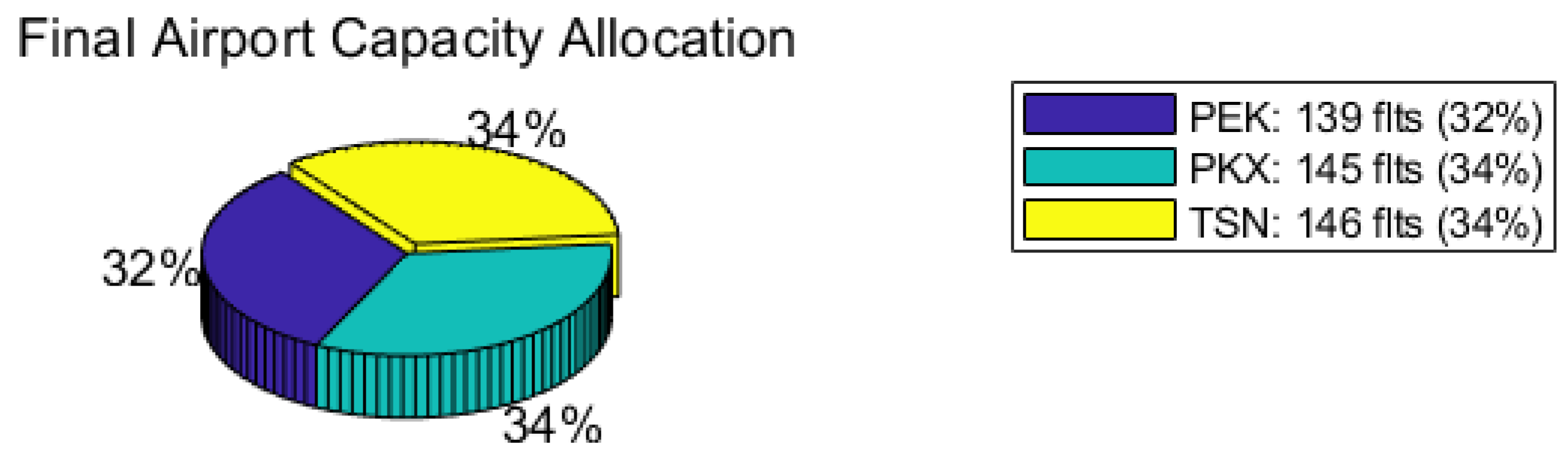

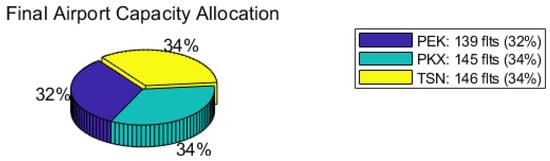

The regulatory role of airports in Layer 3—through slot approval and multi-objective scoring—ultimately shapes the market equilibrium.

As shown in Figure 6, the equilibrium distribution of flight capacity across the three airports is 32% for PEK, 34% for PKX, and 34% for TSN. Passenger market shares display a similar pattern, with PEK, PKX, and TSN accounting for 32.3%, 33.7%, and 34.0%, respectively, with TSN achieving the highest share.

Figure 6.

Final Airport Capacity Allocation Chart.

Compared to the initial distribution (PEK 27.1%, PKX 62.3%, TSN 10.6%), the shift is substantial. TSN’s market share rises from 10.6% to 34.0%, while PKX’s share declines sharply from 62.3% to 33.7%. This confirms the effectiveness of differentiated policy instruments in guiding capacity reallocation across airports.

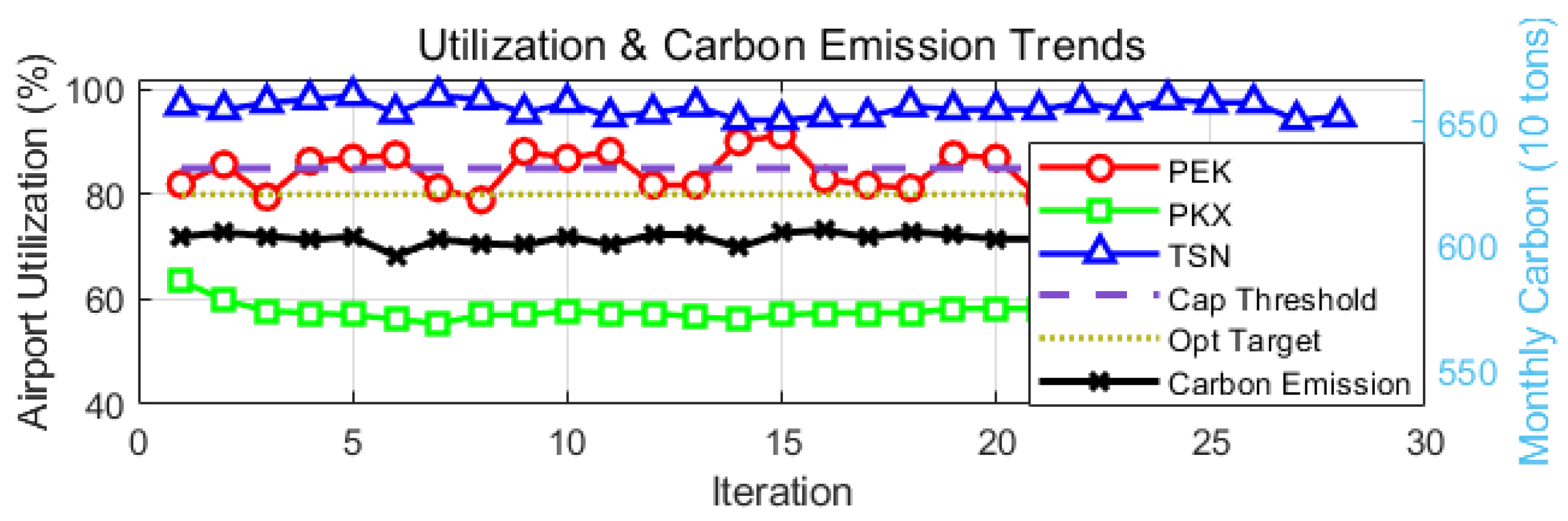

As shown in Figure 7, under the equilibrium outcome, both PEK (86.3%) and TSN (96.2%) maintain high slot utilization rates, while PKX drops to 58.2%. Total monthly carbon emissions decrease from 6119 tons to 6013 tons (a reduction of 106 tons), and per-passenger emissions fall from 104.92 kg to 103.63 kg. Given the carbon tax level of 60 CNY/ton, and considering that carbon charges represent only a small share of airline operating costs compared with fares, fuel, and crew expenses, the emission reduction observed here reflects a marginal rather than a structural improvement.

Figure 7.

Airport Utilization Rates and Carbon Emissions Trends.

The black curve in the figure illustrates the gradual decline in monthly system-wide emissions, decreasing from approximately 6400 tons to 6100 tons per month—an overall reduction of about 4.7%. This pattern is consistent with the relatively weak policy constraint implied by the low carbon tax level. Importantly, the decline in emissions is not inconsistent with TSN’s high utilization rate: although TSN handles more flights in the final equilibrium, its higher operational efficiency and higher average load factors reduce carbon intensity per passenger, contributing to a modest reduction in total emissions.

Overall, these results indicate that under the current parameter setting—characterized by a low carbon tax and moderate environmental weighting—the slot approval process primarily emphasizes economic efficiency, with environmental improvements emerging as secondary, marginal effects.

From a system-wide perspective (Table 4), the variance of airport utilization rates decreases substantially from 0.1233 to 0.0388, indicating a more balanced allocation of capacity across the three airports. In terms of market performance, the total profit of airlines increases modestly (+33,000 CNY per month). Passenger welfare improves significantly as equilibrium fares decline (e.g., PEK dropping from 650 CNY to 481.6 CNY), leading to a substantial rise in total demand.

Table 4.

Final payoff matrix.

Regarding environmental outcomes, despite the sharp increase in total passenger volume (the denominator), system-wide carbon emissions (the numerator) still exhibit a net decrease of 106 tons per month. As a result, per-passenger carbon emissions fall from 104.9 kg to 103.6 kg. This indicates that the reallocation of capacity, driven by differential costs, slot approval priorities, and efficiency advantages, enhances the system’s carbon efficiency while improving both market outcomes and resource utilization (Table 5).

Table 5.

Initial vs. Final Key Performance Indicators.

In summary, the simulation results confirm that the proposed three-layer iterative game model converges to a unique system-wide equilibrium. At equilibrium, intensified market competition drives down fares and improves passenger welfare. Simultaneously, capacity is reallocated from PKX toward TSN under the joint influence of cost differentials and policy-based slot approval mechanisms, leading to a substantial rise in TSN’s market share and a more balanced distribution of resources across the multi-airport system. Notably, despite the significant increase in total passenger volume, the system achieves an improvement in carbon efficiency, demonstrating that coordinated policy incentives and adaptive airline behavior can enhance both operational performance and environmental outcomes.

4.4. Scenario Analysis of Carbon Tax Policy

To evaluate the impact of carbon-neutrality policies, a set of carbon-tax gradient simulations was conducted (0/60/120/240 CNY per ton). The key indicator variations are shown in Table 6. The simulation results reveal a three-fold impact mechanism of the carbon tax within the Beijing–Tianjin multi-airport system.

Table 6.

Carbon Tax Gradient Scenario Simulation.

First, the market share of Tianjin Binhai Airport () responds strongly and positively to the carbon-tax intensity. When increases from 0 to 240 CNY/ton, rises by 13.8 percentage points, indicating that stricter environmental regulation drives airline capacity toward more efficient nodes. Second, system-wide carbon emissions decrease exponentially with the tax rate. At , monthly emissions fall to 5483 tons, an 11.6% reduction, demonstrating the marginal abatement effectiveness of the carbon tax. Third, airline profitability exhibits only weak elasticity. Even at the highest tax rate, total profits decline by merely 4.7%, highlighting the sector’s strong resilience in absorbing environmental costs.

The analysis identifies a policy-efficient threshold in the range of where cost–effectiveness is maximized: each additional unit of carbon tax generates 3.73 tons of emission reduction and 0.095 percentage-point growth in TSN’s market share, while profit losses remain below 1.5%. Accordingly, the study recommends that medium-term policy design prioritize this interval, leveraging structural reallocation of traffic to activate a self-reinforcing decarbonization mechanism.

The simulation results indicate that, under existing route demand scales and airport capacity constraints, the carbon tax policy has a relatively limited effect on reducing the overall carbon emission level of the system. This outcome does not imply that carbon policies are ineffective; rather, it reflects the limited short-term potential for achieving deep emission reductions solely through capacity reallocation within the air transport system. In contrast to directly reducing the number of flights, the carbon policy in this model primarily contributes to emission reduction by improving capacity allocation efficiency and increasing passenger load factors. This aligns with the real-world low-carbon transition pathway of the air transport system, which is primarily driven by efficiency improvements.

Overall, the results presented in this section directly address the research questions raised in the Introduction. The Layer 1 results demonstrate how passenger choice and airline pricing jointly shape demand distribution in a multi-airport system. The Layer 2 analysis shows that carbon taxation affects airlines’ capacity transfer decisions in a non-uniform manner, interacting with airport costs and regulatory constraints rather than inducing simple traffic reduction. Finally, the Layer 3 results confirm that airport-level slot regulation with environmental considerations can mitigate homogeneous competition and promote a more balanced and sustainable capacity allocation across airports.

4.5. Robustness Analysis: Multiple Overlapping Routes from the Beijing–Tianjin MAS

To verify the applicability and robustness of the constructed three-layer iterative equilibrium game model under different route conditions, on the basis of the original analysis of the Beijing–Tianjin–Nanchang route, this paper further selects three domestic overlapping routes jointly served by the Beijing–Tianjin multi-airport system (Beijing Capital Airport, Beijing Daxing Airport and Tianjin Binhai Airport) as extended research objects, namely the Beijing–Tianjin–Yinchuan Hedong, Beijing–Tianjin–Lijiang Sanyi and Beijing–Tianjin–Qiqihar Sanjiazi routes.

These routes exhibit significant differences in flight distance, demand scale and travel purpose. Specifically, the Beijing–Tianjin–Yinchuan route is a typical medium-haul northwest route, where the market is highly sensitive to ticket prices and operational costs; the Beijing–Tianjin–Lijiang route features a longer flight distance and distinct tourism-oriented characteristics, with relatively high passenger demand elasticity; the Beijing–Tianjin–Qiqihar route has a relatively shorter flight distance, yet its overall demand scale is limited and stable, representing small and medium-sized markets in the northeastern region. By introducing these heterogeneous routes, this study can systematically verify whether the equilibrium mechanism of the model remains consistent under varying operational environments.

In terms of model specification, all routes adopt the same three-layer game structure and parameter calibration method as the benchmark case. Only objective parameters including flight distance, basic ticket price, flight operational cost and carbon emission level are adjusted across different routes, while other behavioral assumptions and policy mechanisms remain unchanged.

Under the same policy scenarios and game rules, iterative simulations are conducted for each of the four routes separately to obtain the equilibrium operation results of each route. Table 7 summarizes the changes in key indicators of different routes under the system equilibrium state, including the changes in market share of Tianjin Binhai Airport, average ticket price, passenger demand, and carbon emissions per passenger.

Table 7.

Equilibrium Outcomes across Multiple Routes.

It can be seen from the comparative results that although the magnitude of changes in equilibrium outcomes varies across different routes, the overall direction of change is highly consistent, exhibiting relatively stable systematic characteristics.

Specifically, the market share of Tianjin Binhai Airport has increased to varying degrees across all route scenarios, indicating that under the combined effects of airport charges, slot allocation mechanisms and carbon emission constraints, airlines tend to shift part of their capacity from Beijing Capital Airport and Beijing Daxing Airport—where operational costs are relatively higher—to Tianjin Binhai Airport. Meanwhile, intensified competition among multi-airport systems has prompted airlines to adopt more competitive pricing strategies, leading to a general decline in average ticket prices and thus driving the overall expansion of passenger demand.

In terms of environmental performance, carbon emissions per passenger have shown a downward trend across all routes. This is mainly attributed to the improved flight load factors and enhanced allocation efficiency of route resources following capacity reconfiguration. However, the magnitude of carbon emission reduction varies across routes: routes with higher demand density are more likely to achieve lower per-unit emissions through economies of scale, whereas routes with limited demand scale exhibit relatively moderate emission reduction effects. Synthesizing the simulation results of multiple routes, it is found that the three-layer iterative equilibrium game model constructed in this paper does not rely on the parameter settings of specific routes, and its core equilibrium mechanism can stably manifest under different conditions of flight distance, demand structure and market scale. This indicates that what the model depicts is not a special phenomenon of individual routes but a structural equilibrium result in the operation of the Beijing–Tianjin multi-airport system.

Meanwhile, the differences in the magnitude of changes in equilibrium outcomes across routes reflect the impacts of route-specific factors such as demand elasticity, flight distance and carbon emission intensity on the system adjustment effects. These heterogeneous results further demonstrate that when formulating policies for the coordinated development and low-carbon regulation of multi-airport systems, it is necessary to implement differentiated policy tools tailored to the characteristics of different routes, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all uniform scheme.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the persistent issues of unbalanced capacity allocation and homogeneous competition within the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei multi-airport system by developing a three-layer iterative equilibrium game model. The proposed framework integrates passenger airport choice, airline capacity allocation, and airport slot regulation into a unified dynamic system, capturing the co-evolution of decisions through a closed feedback loop of “pricing → reallocation → approval”.

Using the “Beijing–Tianjin–Nanchang” route as a representative case, numerical simulations demonstrate that the system converges robustly to a unique systemic equilibrium. The equilibrium outcomes exhibit several key characteristics shaped jointly by market competition and regulatory intervention. First, intensified airport competition leads to a substantial reduction in equilibrium fares and a notable expansion of passenger demand, thereby improving overall passenger welfare. Second, differentiated airport charges and green-oriented slot-approval preferences induce a structural reconfiguration of capacity: Beijing Daxing Airport (PKX) experiences a net outflow of flights, while Tianjin Binhai Airport (TSN) emerges as the primary recipient, reflecting its comparative economic and regulatory advantages. Third, the reallocation process enhances system-wide coordination, as evidenced by a marked decline in the variance of airport utilization rates and a modest increase in total airline profits, suggesting that coordinated development can generate positive-sum outcomes rather than zero-sum competition.

From an environmental perspective, the introduction of carbon taxation leads to marginal reductions in both total and per-passenger CO2 emissions under the current policy setting, confirming the effectiveness of embedding green regulatory objectives directly into the slot-approval mechanism. Although the magnitude of emission reduction remains limited, this result reflects the constrained short-term mitigation potential of capacity reallocation under existing demand and infrastructure conditions, while highlighting the scope for stronger environmental gains under stricter carbon-pricing regimes.

It should be emphasized that the proposed model is not intended to precisely predict the operational outcomes of specific routes but rather to elucidate the interaction mechanisms among passengers, airlines, and airports in multi-airport systems and their dynamic evolution under low-carbon policy constraints. Carbon taxation is therefore modeled as a representative operational policy instrument that can be directly integrated into airline and airport decision-making. Other long-term measures—such as subsidies for sustainable aviation fuels, fleet renewal incentives, and investments in low-carbon airport infrastructure—are recognized as important complementary policies operating over longer planning horizons.

From a practical implementation perspective, the proposed framework is not confined to the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Its applicability to other multi-airport systems depends primarily on data availability and institutional comparability rather than region-specific assumptions. The key inputs required by the model—passenger demand, airport accessibility, airline operating costs, capacity constraints, and carbon-emission parameters—are routinely collected by aviation authorities and airport operators, allowing the framework to be recalibrated and extended to other multi-airport regions.

In terms of governance, the balancing mechanisms identified in this study operate across multiple regulatory levels. Carbon taxation and emission-related regulations are typically designed and enforced at the national level, reflecting overarching climate policy objectives. In contrast, differentiated airport charges and green-oriented slot-approval rules are more appropriately implemented by regional aviation authorities or airport operators, who possess detailed operational information and regulatory discretion. Airlines act as market participants that respond endogenously to these policy signals through capacity allocation and route-adjustment decisions. Effective coordination across these governance levels is therefore essential for translating the model’s insights into practical capacity-management strategies.

Overall, the findings indicate that differentiated airport charges, green-oriented slot-approval rules, and coordinated capacity-management policies can steer multi-airport regions away from homogeneous competition toward functional complementarity and sustainable development. The proposed iterative equilibrium game model provides both a novel analytical framework and a practical decision-support tool for regional air transport planning under sustainability objectives. By extending the analysis to multiple overlapping routes with heterogeneous characteristics, the robustness of the core equilibrium mechanism is further verified, partially mitigating the limitations of a single-case study. Future research may further enhance the model’s policy relevance by incorporating additional multi-airport regions and richer empirical data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; Software, Y.W.; Validation, Y.W.; Investigation, Y.W.; Resources, Y.W.; Data curation, Y.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.W.; Writing–review and editing, Y.L.; Visualization, Y.L. and Y.W.; Supervision, Y.L.; Project administration, Y.L.; Funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Youth Fund Project of Humanities and Social Sciences”, grant number [21YJCZH075]; “Joint Funds of the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin—General Project”, grant number [25JCLMJC00530]; “Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research of Central Universities, Civil Aviation University of China Special Project”, grant number [3122024055]. And The APC was funded by Yafei Li.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morton, C.; Mattioli, G. Competition in Multi-Airport Regions: Measuring airport catchments through spatial interaction models. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2023, 112, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neufville, R.; Odoni, A.R.; Belobaba, P.P.; Reynolds, T.G. Airport Systems: Planning, Design, and Management, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Wu, H. A System Dynamics Model of Multi-Airport Logistics System under the Impact of COVID-19: A Case of Jing-Jin-Ji Multi-Airport System in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Cao, X.; Li, S. Competition and Sustainability Development of a Multi-Airport Region: A Case Study of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Huang, M.; Zhang, J.; Witlox, F. On the Matthew effect in a multi-airport system: Evidence from the viewpoint of airport green efficiency. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2023, 106, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Air Transport Action Group (ATAG). Aviation Benefits Beyond Borders; Air Transport Action Group: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aviation Industry Plans for Growth ‘Irreconcilable’ with Europe’s Climate Goals. Available online: https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles/aviation-industry-plans-for-growth-irreconcilable-with-europes-climate-goals (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Yan, R.; Tang, B.-J.; Hu, Y.-J.; Ji, C.-J.; Lin, K.-B.; Shen, M. Sustainable Aviation Fuel and Next-Generation Aircraft: Low-Carbon Pathway for China’s Civil Aviation Industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xuan, C.; Qiu, R. Evolutionary Analysis of Airline Networks under Different Airport-Provided Subsidy Regimes in the Context of Multiple Airport Systems. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 119, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zheng, C.; Chen, X.; Wandelt, S. Multiple Airport Regions: A Review of Concepts, Insights and Challenges. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 120, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.K.-Y.; Wong, W.-H.; Zhang, A.; Wu, Y. Spatial panel model for examining airport relationships within multi-airport regions. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 133, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Zhang, N. Topology and Robustness of Weighted Air Transport Networks in Multi-Airport Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Lin, Z.; Wang, X. Evolutionary Game of Subsidy Strategies on Multi-Airport Route Networks Under Homogeneous Competition. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2025, 51, 3392–3404. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Cong, W.; Wang, K.; Mu, J.; Chen, X.; Wandelt, S. MARRI: Towards a Multiple-Airport Region Resilience Index. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.A.; Jacquillat, A.; Antunes, A.P.; Odoni, A.R.; Pita, J.P. An Optimization Approach for Airport Slot Allocation under IATA Guidelines. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2018, 112, 132–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zografos, K.G.; Jiang, Y.A. Bi-Objective Efficiency–Fairness Model for Scheduling Slots at Congested Airports. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 102, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.A.; Jacquillat, A.; Antunes, A.P.; Odoni, A.R. Improving Slot Allocation at Level 3 Airports. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 127, 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Androutsopoulos, K.N.; Manousakis, E.G.; Madas, M.A. Modeling and Solving a Bi-Objective Airport Slot Scheduling Problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 284, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Hu, R.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C. Bi-Objective Airport Slot Scheduling Considering Scheduling Efficiency and Noise Abatement. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 115, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Hu, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. An Integrated Slot Allocation Model for Time–Space–Dimensional Noise Reduction. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 119, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Feng, H.; Witlox, F.; Zhang, J.; O’Connor, K. Airport Capacity Constraints and Air Traffic Demand in China. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 103, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Hu, R. Equity and Efficiency Trade-Off in Allocating Airport and Airspace Capacity in a Multiple Airport System. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 181, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, S.; Hu, M.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y. Allocating New Slots in a Multi-Airport System Based on Capacity Expansion. Aerospace 2024, 11, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Wang, D.; Feng, H.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X.; Deng, S. Joint Gate–Runway Scheduling Considering Carbon Emissions, Airport Noise and Ground–Air Coordination. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 112, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ding, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L. Emission Reduction with Hybrid Mechanisms in Civil Aviation: An Evolutionary Game Approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1138931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, Q. A Simultaneous Optimization Model for Airport Network Slot Allocation under Uncertain Capacity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Zhang, A. Airport–Airline Relationship, Competition and Welfare in a Multi-Airport System: The Case of New Beijing Daxing Airport. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 2022, 56, 156–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Ding, R. How to Achieve Carbon Abatement in Aviation with Hybrid Mechanism? A Stochastic Evolutionary Game Model. Energy 2023, 285, 129349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Jia, T.; Wang, S.; Hao, Q.; Yang, J. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Promotion. Energy 2025, 322, 135723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Witlox, F. Spatial Characteristics of Aircraft CO2 Emissions at Different Airports: Some Evidence from China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Hu, R.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J. Uncertainty and Its Driving Factors of Airport Aircraft Pollutant Emissions Assessment. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 94, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Buyle, S.; Macário, R. Developing an Airport Sustainability Evaluation Index through Composite Indicator Approach. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2023, 113, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Macário, R.; Buyle, S. Expanding Horizons: A Review of Sustainability Evaluation Methodologies in the Airport Sector and Beyond. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagkouni, A.; Dimitriou, D. Sustainability Performance Appraisal for Airports Serving Tourist Islands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, J.; Baltazar, M.E. Sustainable Airport Development: A Literature Review Based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Methodology, Using Open Alex Database. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owais, M. Emission reduction calculations for mass rapid transit: Theory, methodology, and practical application. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owais, M. Location Strategy for Traffic Emission Remote Sensing Monitors to Capture the Violated Emissions. J. Adv. Transp. 2019, 2019, 6520818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2023; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023.