Abstract

This study examines the motivations, socio-demographic profiles, and behavioural orientations of residents in Northern Italy toward mountain and forest visitation, with a focus on their propensity to engage in forest-based health and wellness activities. The analysis draws on a large stratified survey conducted between December 2023 and January 2024, involving 1218 respondents, of whom 976 reported regular forest visitations. Exploratory factor analysis identifies two main attitudinal dimensions: “Health and Wellness-Driven Forest Engagement”, centred on psychophysical restoration, and “Comfort-Oriented Forest Use”, related to accessibility and low physical effort. Regression models show that wellness-oriented engagement is strongly associated with psychological well-being, walking and hiking habits, and gender, while comfort-oriented use reflects seasonal patterns and preferences for easily accessible forests. A small subset of respondents reports discomfort in forest environments, forming a distinct attitudinal barrier. Overall, the results indicate substantial potential for forest-based wellness tourism to support healthier lifestyles and diversify mountain economies. Policy implications highlight the need for accessible infrastructures, targeted communication, and the integration of wellness-oriented services into regional development strategies.

1. Introduction

Wellness and health-focused experiences are becoming an increasingly strategic component of contemporary leisure consumption. This trend reflects rising stress levels, greater attention to preventive health practices, and a shift toward lifestyles oriented to mental balance and well-being. Wellness tourism, understood as mobility motivated by physical, emotional, and mental health, is now widely recognised as a resilient sector with potential to support territorial development [1,2]. As travellers increasingly seek restorative experiences, nature immersion, and meaningful encounters with landscapes, mountain regions have gained particular relevance as destinations for health and well-being-oriented tourism [3].

Mountain environments provide distinctive natural resources that support health and wellness experiences. Clean air, extensive forests, biodiversity, silence, and strong landscape identity contribute to their restorative potential, encouraging visitation for well-being purposes and supporting positive physical and mental health outcomes [4,5]. These attributes are not only aesthetically appealing but are also empirically linked to measurable health benefits, including reductions in stress and improvements in cognitive and emotional functioning [6,7]. In a period marked by rapid urbanisation and increasingly sedentary lifestyles, mountain territories represent accessible spaces for psychological renewal and engagement in physical activity, reinforcing their role within the wellness tourism economy.

However, mountain regions also face persistent socio-economic challenges. Demographic decline, youth out-migration, limited diversification of employment, and dependency on seasonal income sources contribute to territorial fragility [8,9]. Tourism has historically played a central role in sustaining mountain economies, but in many regions it remains highly seasonal or overly dependent on winter sports, a sector increasingly exposed to climate variability and environmental change [10]. These dynamics highlight the necessity of diversifying tourism products, developing new market segments, and creating year-round tourism opportunities that can support stable local livelihoods [11].

Within this framework, wellness and health tourism—closely intertwined with nature-based tourism—offers promising development pathways. Nature-based tourism encompasses a wide spectrum of activities associated with outdoor environments, such as hiking, wildlife observation, landscape appreciation, and leisure experiences in forested areas [12,13]. Wellness and health tourism intersects with this field by focusing on experiences that foster psychophysical well-being, frequently facilitated through immersive contact with natural settings [14,15]. Given their symbolic association with purity, elevation, and solitude, mountain environments are particularly well suited to these forms of tourism.

Forest environments play a central role in this emerging landscape. Forest ecosystems deliver essential ecological services—including carbon storage, biodiversity conservation, and soil protection—while simultaneously providing cultural and recreational benefits that are fundamental to human well-being [16,17]. Beyond their ecological value, a growing body of research has shown that forest environments are particularly effective in promoting restorative experiences, by reducing mental fatigue, supporting attentional recovery, and fostering feelings of tranquility and vitality. Empirical studies have further documented a range of physiological and psychological benefits associated with forest exposure, including reductions in cortisol levels and blood pressure, improvements in immune function, and enhanced emotional and cognitive states. Evidence of these effects has been observed across diverse population groups and forest contexts, including university students, individuals with depressive tendencies, and older adults, among others, e.g., [18,19,20].

These findings underpin the growing popularity of Shinrin-yoku, a practice involving guided or self-directed immersion in forest environments to promote psychophysical well-being [21,22]. Forest therapy and forest bathing have gained substantial international visibility and are increasingly incorporated into tourism strategies, public-health initiatives, and regional development policies across Europe and Asia. In mountain regions, where forests are extensive and landscape identity is particularly strong, these practices offer a distinctive opportunity to develop a year-round, low-impact tourism product capable of generating economic, social, and health benefits.

While the supply-side potential of forest-based wellness tourism is relatively well documented, significant gaps remain on the demand side. In particular, limited evidence exists on who visits mountain and forest environments, what motivates them, and to what extent they are inclined to participate in wellness-oriented practices such as forest therapy [23]. Motivations for visiting natural settings are multifaceted and may include escaping urban stress, engaging in physical activity, appreciating landscapes, pursuing cultural interests, strengthening social relationships, and seeking tranquility [24,25,26].

Moreover, socio-demographic characteristics play an important role in shaping recreational behaviours and attitudes toward nature-based wellness activities. Factors such as age, gender, educational attainment, environmental values, and place of residence influence how individuals perceive the benefits of forest environments and how they incorporate nature into their leisure routines [27,28].

For mountain regions, policies that promote forest-based wellness tourism can generate multiple co-benefits: they may support the diversification of local economies, help counteract demographic decline, and reinforce the perceived value of forest ecosystems [29,30,31]. To design such policies effectively, however, it is essential to base them on robust evidence regarding the attitudes, preferences, and needs that shape individuals’ willingness to visit forests for health and well-being purposes.

The study addresses these gaps through an exploratory analysis of residents in Northern Italy, a region characterised by extensive forest cover, prominent mountain landscapes, and rapidly evolving tourism dynamics. Accordingly, the research is guided by the following questions:

RQ1. What are the main attitudinal dimensions that characterise individuals’ orientations toward forest environments for health and wellness purposes?

RQ2. Which socio-demographic characteristics, motivations, and recreational behaviours influence individuals’ engagement with forest-based health and wellness activities?

In addressing these questions, the study provides evidence-based insights to inform policy design and support sustainable mountain development strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Questionnaire Survey

This study forms part of a broader research initiative dedicated to analysing the demand for forest-based health and wellness tourism across Northern Italy. A comprehensive account of the study area and the survey design is offered by Visintin et al. [29]. Here, we summarise the key aspects of that framework which are shared with this investigation.

Three macro areas were examined: northwestern Italy (Lombardy, Piedmont, Aosta Valley, Liguria), northeastern Italy (Veneto, the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano), and Friuli Venezia Giulia, which is also the primary focus of the iNEST “Spoke 1” project on Mountain Innovation. Together, these areas cover nearly 98,000 km2 and host approximately 20 million inhabitants. The research considers residents within the selected territories as actual or potential tourists, allowing the analysis to encompass both current visitors and individuals who may engage in forest-based tourism in the future. Stratified sampling generated three demographically balanced panels, structured by age and gender to ensure representativeness across the resident populations.

A questionnaire was developed and adapted within the framework of a broader research project aimed at exploring the demand for wellness-related activities in the Italian Alpine regions [29]. While not based on a single validated instrument, its design was informed by established literature on wellness, nature-based well-being, and forest-related recreational practices, and was tailored to the specific objectives and territorial context of the study (see Section 1).

The questionnaire was organised into four thematic sections. The first section addresses the frequency and modalities of mountain visitation with a particular focus on: the seasons in which respondents visit mountain areas; the purposes of these visits (touristic, recreational, or sporting activities; visiting relatives or friends; work; residence; other); the preferences in visiting mountains (physical well-being, psychological well-being, cultural enrichment, discovering the typical gastronomic specialties), and the activities undertaken (e.g., mountaineering, hiking, trekking, forest bathing/therapy). The second section is devoted to forest visitation, in particular: whether forests were visited in mountain, hillside, or lowland environments; the frequency of visitation and respondents’ attitudes toward visiting forests. The third section examined the recreational value attributed to forests and the perceived psychophysical well-being associated with their use. The final section collected socio-demographic information necessary for constructing the socio-economic profile of the subjects in the sample (see Section 2.2).

In particular, one question in the second section of the questionnaire (D16) was designed to assess respondents’ attitudes toward visiting forests, with a specific focus on motivations related to well-being and health (see Section 2.3).

The questionnaire was administered online with the support of a specialised statistical survey firm experienced in managing panel-based studies. Distribution was carried out via the mailing list of Demetra opinioni.net Srl, a national provider of data collected through telephone interviews and online panels. The sample design allocated 384 respondents to each sub-sample, corresponding to a 5% margin of error at a 95% confidence level. Prior to full implementation, the instrument was validated through a pilot test involving 50 panelists. The survey was conducted between December 2023 and January 2024, yielding a total of 1218 completed questionnaires. As this article focuses on the investigation of different aspects related to forest visitation, 976 questionnaires were selected and used in the subsequent analyses, including only respondents who answered “yes” to the item “Do you visit forests?”, intended to capture habitual rather than occasional visitation.

All questionnaires were stored in a Microsoft Excel file, and statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 4.4.2), a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics [32].

2.2. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 reports the socio-demographic characteristics of the 976 respondents. The gender distribution is fairly balanced: 52.8% male and 47.2% female. The age distribution shows a higher representation of individuals aged 30–44 (24.6%) and 45–54 (23.6%), while the youngest (18–29) and oldest (65–75) groups are less represented, at 15.8% and 15.0%, respectively.

Table 1.

Frequency distributions of respondents by their socio-demographics characteristics (N = 976).

With respect to education, more than half of the respondents have completed high school (53.4%), followed by those with a college or university degree (30.8%). Fewer respondents hold a master’s or PhD degree (7.2%) or have less than a high school diploma (8.6%).

Occupational profiles indicate that administrative and office workers form the largest group (38.4%), followed by blue-collar/manual labour workers (16.4%) and self-employed professionals (11.6%). Smaller proportions are found among self-employed workers (8.4%), teachers (8.2%), managers/executives (6.5%), and contributing family workers (5.2%). Smaller shares include entrepreneurs, home-based subcontracted workers and cooperative members.

The economic sectors represented reflect a concentration in personal services and the third sector (40.1%), with public administration or public enterprises (20.6%) and trade/finance/transport/business services (19.9%) also well represented. Industry, including construction, accounts for 16.6%, and agriculture is minimally represented (2.9%).

Income distribution is skewed to the lower classes, as 56.6% of the respondents have less than €30,000, while only 2.7% earn €75,000 or more. Notably, 14% of respondents either did not disclose or were unsure about their income.

More than half (55.2%) of the respondents live in medium-sized municipalities (<30,000 inhabitants), 56.7% live in plain areas, 27.3% reside in hilly areas, and 16.1% in mountain areas.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To explore attitudes toward forest-based health and wellness activities, we analysed Question D16, a sixteen-item scale measuring well-being and health motivations for forest visitation (Table 2). Respondents rated each item on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree), with an additional option (0) for those unwilling to provide an evaluation. The 1–10 response scale was adopted because it aligns with the standard grading system used in Italian primary and secondary education. This familiarity facilitates comprehension, reduces respondents’ cognitive burden, and supports more accurate self-assessment.

Table 2.

Attitudes toward visiting forests (D16).

A multistage analytical procedure was applied. First, descriptive statistics were computed for all sixteen D16 items to identify general response patterns. Next, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on a subset of items to extract latent attitudinal dimensions. Factor scores obtained from EFA were then used as dependent variables in multiple regression models assessing the influence of socio-demographic, behavioural, and contextual characteristics on attitudinal orientations. Finally, a set of logistic regression models was estimated for a subset of items representing discomfort or avoidance behaviours. These items were first recoded into binary variables to identify patterns of strong negative attitudes and to examine the characteristics associated with respondents expressing such discomfort.

3. Results

This section outlines the results emerging from the multistage statistical analysis of the data.

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

Before conducting the factor analysis, a preliminary descriptive examination of the sixteen items in question D16 was carried out in order to characterize the distributional properties of the responses. Graphical representations of the frequency distributions (bar charts) and summary statistics (means, medians, standard deviations) were computed for each item to characterize respondents’ attitudes toward forest-based health and wellness motivations. These descriptive outputs refer exclusively to the ordinal part of the scale (1–10), as the “0” option represents a non-evaluative response that does not belong to the underlying attitudinal continuum.

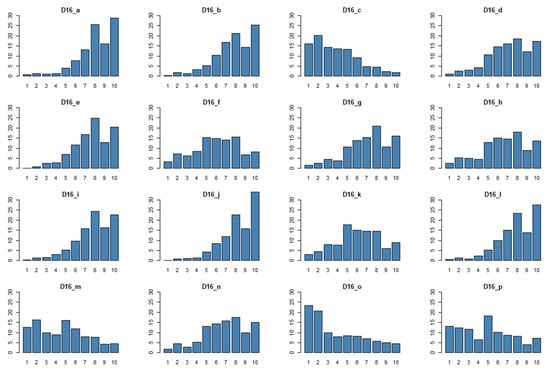

Figure 1 presents the percentage frequency distributions of the responses in the 1–10 scale for each of the sixteen items, while Table 3 reports their means, medians, standard deviations and two additional columns indicating the percentage of valid cases (responses in the 1–10 scale) and the percentage of “0” responses.

Figure 1.

Percentage frequency distribution of 1–10 responses for each item in D16.

Table 3.

Summary statistics (1–10 responses), and percentage of 0 responses for each item in D16.

The descriptive statistics of the sixteen D16 items reveal a strong agreement of forest-related health and wellness aspects (D16_a, D16_b, D16_d, D16_e, D16_i, D16_j and D16_l). Across these items, the mean and median values fall between 7 and 8 on the 1–10 scale, with relatively low standard deviations (around 1.8–2.4), indicating that respondents consistently expressed moderate to high levels of agreement with positive motivations. This pattern suggests a coherent attitudinal structure and limited polarization: the distributions are concentrated on the upper end of the scale. Then there is a set of items (D16_f, D16_g, D16_h, and D16_n) related to comfort in visiting the forest environment, which show a lower level (even if positive) of agreement and a higher level of variability. Only a small subset of items (D16_c, D16_m, D16_o, and D16_p) show substantially lower means (around 3–5), reflecting their thematic focus on discomfort, barriers, or negative experiences associated with forest visits. These items exhibit higher variability (standard deviations above 2.5 for some items), suggesting greater heterogeneity in respondents’ perceptions and experiences.

A critical aspect of this preliminary phase concerns the additional response option “0,” which explicitly captures a non-evaluative choice (i.e., the respondent does not wish to express a judgment). As such, “0” does not lie on the ordinal continuum defined by the 1–10 Likert scale and cannot be interpreted as an attitudinal position. For these reasons, we will consider “valid responses” only the responses in the 1–10 range and the value 0 as “non-response”, i.e., not a valid value on the scale and considered as a missing value. As shown in the last two columns of Table 3, in a group of items, such as D16_a, D16_b, D16_d, D16_e, D16_g, D16_i, D16_j, D16_l, the level of non-responses was very low, less than 2%, showing excellent item clarity and high perceived relevance. A second group of items, such as D16_f, D16_h, D16_k, D16_n, showed moderate non-response levels (3–7%), meaning that they may be slightly less relevant or respondents may perceive them as optional. In contrast, a subset of four items—D16_c, D16_m, D16_o, and D16_p—exhibited markedly high proportions of “0” responses, ranging from 29.3% (D16_c) to 58.3% (D16_o). These items are thematically linked to discomfort, barriers, or negative experiences associated with visiting forests, and their elevated non-response rates suggest that many participants either lacked personal experience with these situations or felt unable or unwilling to express a judgment.

Because the prevalence of these non-responses varies substantially across items and appears systematically associated with a set of items describing a particular latent construct, e.g., discomfort, barriers, or unfamiliarity, it is unlikely that they satisfy the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption. Instead, the observed pattern is more consistent with a Missing Not at Random (MNAR) mechanism, where the probability of opting out is itself related to the unobserved attitude the item is intended to measure. Given the extent of missingness and its likely MNAR nature, these four items were excluded from the factor analysis to avoid distorting the factor structure and to preserve comparability across respondents. However, patterns of zeros may still offer valuable insights, as such items can be relevant for specific subpopulations.

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Regression Analysis

EFA was conducted on the 12 items with a high response rate. Given the very low proportion of missing values (0–7%) and their distribution consistent with MAR assumptions. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion. This choice is appropriate given the very low proportion of missing values and ensures the use of a single, internally consistent covariance matrix. Pairwise deletion was avoided because it may lead to inconsistent or non-positive definite covariance structures and estimation artefacts [33,34,35]. After applying listwise deletion to the 12 items with low non-response, a total of 805 complete cases were available for EFA. This sample size is well above established recommendations for EFA adequacy [36,37] and ensures stable and reliable factor extraction as 805/12 = 67 > 10 units per item. The overall value of Cronbach’s Alpha, for internal consistency, is 0.86, indicating a good internal consistency, well above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70.

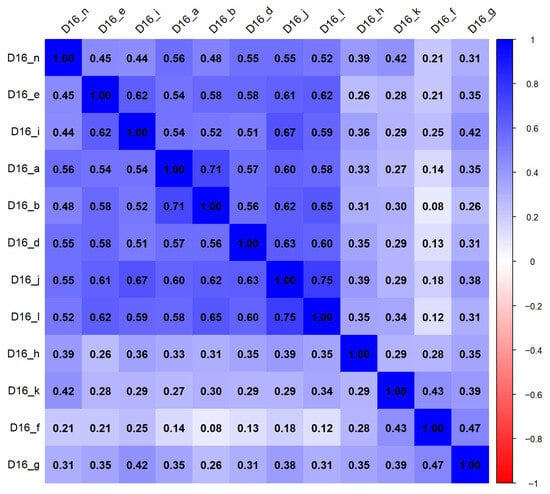

The exploratory factor analysis was conducted on a polychoric correlation matrix. This choice is motivated by the ordinal nature of the 1–10 response scale. Polychoric correlations assume that the observed item responses arise from discretized realizations of underlying continuous latent variables, and are therefore recommended for factor analysis of ordinal data [38,39].

Figure 2 displays the correlogram of the polychoric correlation matrix for the twelve D16 items. The values in each cell represent polychoric correlations, and the color scale reflects the direction and magnitude of associations (dark blue = strong positive correlation; light blue = weak positive correlation; white = near zero). All correlations are positive. Items are ordered using hierarchical clustering, which groups together variables with similar correlation patterns. Clusters of darker cells along the diagonal highlight sets of items that are more strongly interrelated, providing preliminary visual evidence of the underlying factor structure later examined through EFA.

Figure 2.

Correlogram of the clustered polychoric correlations among the twelve D16 items.

The cluster grouping together items D16_j, D16_l, D16_d, D16_a, D16_b, D16_e, D16_i, shows moderate to strong correlations (0.50–0.75). These items form a block, suggesting they may load on the same latent factor. A second cluster that regards items D16_h, D16_k, D16_f, and D16_g shows weaker correlations, suggesting the possibility of a second factor.

The suitability of the data for factor analysis was assessed using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 4913.22, df = 66, p < 0.001), suggesting that correlations between items were sufficient for factor analysis. The Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) was excellent overall (MSA = 0.91), with individual item MSAs ranging from 0.75 to 0.95, confirming the adequacy of the sample for factor extraction.

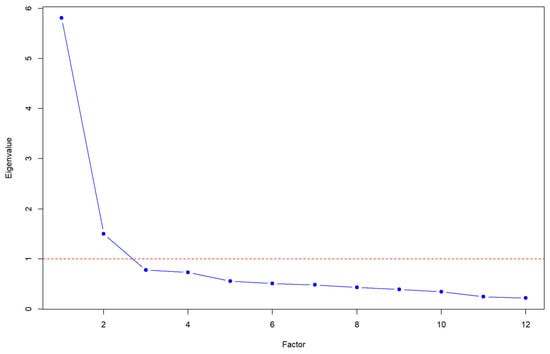

The initial eigenvalue distribution is depicted in the scree plot (Figure 3). The elbow in the curve suggests a two-factor solution that is the same if we consider the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue > 1) as the eigenvalue of the first factor is 5.81, while that of the second factor is 1.50, confirming the initial suggestion given by the polychoric correlation matrix.

Figure 3.

Scree plot of the eigenvalues from the polychoric correlation matrix (blue line) and the Kaiser criterion threshold (eigenvalue =1; red dashed line).

Starting from this point, after some attempts, we decided to adopt the principal axis factoring with Varimax rotation. The extracted two-factor model produced a clear and interpretable structure (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rotated Factor Loadings (Loadings > 0.30) and communalities.

Cells corresponding to loadings < |0.30| are left blank, as these values indicate that the item does not meaningfully contribute to that factor. The first factor aggregated most items with substantial loadings (0.60–0.81), while the second factor captured a smaller group of items with moderate to high loadings (0.54–0.77). Item D16_h showed moderate cross-loadings but remained interpretable within the overall structure. Based on the pattern of loadings, the first factor was interpreted as “Health- and Wellness-Driven Forest Engagement” (D16_a, D16_b, D16_d, D16_e, D16_i, D16_j, D16_l, D16_n), capturing motivations related to physical and psychological well-being. The second factor was labelled “Comfort-Oriented Forest Use” (D16_f, D16_g, D16_h, D16_k), reflecting a preference for low-effort, accessible, and comfortable forest experiences. Factor 1 explains 37.9% of the total variability, while Factor 2 explains 15.4%. The communalities, which represent the proportion of variance in each observed item that is explained by the extracted factors, are over the accepted threshold of 0.3 [40] except for the item D16_h. The two factors together explain 53.3% of the total variance, which is acceptable for psychological and social science constructs measured with ordinal items. Overall, the results indicate a robust and well-defined two-factor structure, supporting the presence of two underlying latent dimensions measured by the items.

With the aim of detecting if the characteristics and the behaviour of the respondents have an impact on the factors obtained, we will use the scores of the two factors obtained with EFA as dependent variables in regression models. Table 5 reports the results of the multiple regression analysis. Among the sociodemographic variables initially considered, only gender showed a statistically significant association with the dependent variables. Other sociodemographic variables—mostly categorical or ordinal—were tested but excluded from the final specification, as their inclusion increased model complexity without improving goodness of fit. While several predictors retained in the final model are not individually statistically significant, they were included because they represent conceptually relevant dimensions of mountain and forest use (seasonality, motivations, activities, and spatial context). Excluding these variables did not improve model fit and would have reduced interpretability.

Table 5.

Results of the two multiple regression models.

The regression model for Factor 1 (“Health and Wellness-Driven Forest Engagement”) explains 61% of the variance. Women report higher wellness-oriented engagement than men, and winter mountain visitors score slightly lower on this factor. Strong appreciation for mountain visits, together with motivations linked to physical and psychological well-being, significantly increases engagement. Walking, hiking, and cultural activities also have positive effects. Notably, respondents who visit mountain forests—whether occasionally or frequently—show lower wellness-oriented engagement than those who never visit them, suggesting that health and wellness-driven practices may be more common in more accessible forest types, such as lowland or foothill settings.

The model for Factor 2 (“Comfort-Oriented Forest Use”) explains 19% of the variance, indicating a weaker attitudinal structure. Men are less comfort-oriented than women, while summer mountain visitors score higher on this factor. Preference for trekking activities and for thermal parks or spas is positively related to comfort-oriented forest use, as is visiting forests in the plains.

Overall, wellness-oriented engagement (Factor 1) is strongly associated with well-being motives and physically active behaviours, whereas comfort-oriented use (Factor 2) is more closely linked to leisure preferences, seasonal patterns, and easily accessible forest environments.

The next step is devoted to the analysis of the four items D16_c, D16_m, D16_o and D16_p. In order to focus on individuals expressing particularly strong forms of discomfort or unwillingness in relation to forest environments, a subset of items measuring fear of access, avoidance of activities, discomfort with contact with nature, and non-participation in forest sports was recoded into binary outcomes.

The original items were measured on a 1–10 scale, with higher values indicating increasing levels of discomfort or unwillingness. Rather than applying a mid-point threshold, which would capture moderate and heterogeneous attitudes, we adopted a high-cut threshold in order to isolate respondents located at the upper tail of the distribution. Specifically, responses equal to or higher than 8, corresponding approximately to the 90th percentile of the empirical distributions, were coded as 1, indicating high discomfort/unwillingness, while lower evaluative responses (1–7) were coded as 0.

This coding strategy is consistent with the analytical aim of identifying a distinct subgroup of respondents exhibiting pronounced barriers to forest engagement, rather than general or moderate forms of unease. By focusing on extreme responses, the resulting binary indicators capture individuals for whom fear, discomfort, or avoidance is likely to translate into concrete behavioural outcomes, such as unwillingness to do forest activities or sports participation.

Non-evaluative responses originally coded as zero were treated separately and excluded from regression analyses, as these responses do not convey information about the intensity of discomfort. The resulting binary variables, therefore, represent a conditional probability of expressing strong discomfort, given an evaluative judgment.

This approach allows for a more targeted exploration of the factors associated with severe discomfort profiles, enhancing the interpretability of the subsequent logistic regression models and ensuring coherence with the study’s focus on practical barriers to engagement with forest and mountain environments.

Given this recoding strategy, binary logistic regression models were estimated to identify the individual and contextual characteristics associated with a higher probability of expressing strong disagreement for each of the four discomfort-related outcomes. Separate logit models were fitted for fear, discomfort with contact with nature, avoidance of forest activities, and non-participation in forest sports. The models quantify how and if socio-demographic factors, attitudes, and contextual variables are related to the likelihood of belonging to the subgroup of respondents exhibiting high levels of discomfort, as defined by the upper-tail threshold.

Table 6 presents the Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) from four logistic regression models estimating the probability of reporting (1) Fear, (2) No Activity, (3) Discomfort, and (4) No Sport in forest environments. AMEs represent the change in predicted probability associated with a one-unit increase in continuous predictors or a change from the reference category for categorical predictors.

Table 6.

Average Marginal Effects and significance of the four logistic regression models.

Gender and age show no statistically significant association with any of the four outcomes. Educational attainment also shows limited influence. Respondents with a Master’s or PhD are significantly less likely to report No Activity (AME = −0.204, p = 0.015), but education levels do not significantly predict fear, discomfort, or avoidance of sport-related activities. Income exhibits a more heterogeneous pattern. Individuals in upper-middle income categories (€45,001–€60,000 and €60,001–€75,000) show a higher probability of reporting fear (AME = 0.176 and 0.353, respectively; p < 0.05). The direction of the effect suggests that fear may be more prevalent among higher-income respondents. In contrast, respondents who did not disclose their income (“Prefer not to disclose”) or who were unsure about their income show significantly lower probabilities of No Activity (AME = −0.164, p = 0.015; AME = −0.241, p < 0.001) and significantly lower discomfort (AME = −0.109, p < 0.001). These findings likely reflect systematic differences in disclosure preferences or uncertainty rather than income itself and should be interpreted with caution.

Effects related to municipality size are generally modest. Living in a very large urban area (>250,000 inhabitants) increases the probability of No Activity (AME = 0.141, p = 0.019), indicating that residents of major cities are more likely to avoid forest activities altogether. No other municipality-size effect is statistically significant. Residential altitude (Hill, Mountain, Plain) does not significantly predict any of the four outcomes, suggesting that everyday exposure to different terrain types does not directly translate into fear, discomfort, or activity patterns in forests. Also, the propensity to visit mountains is not significant for the four models.

Patterns of forest visitation show clearer associations with the outcomes. Visiting forests in plain areas is positively associated with discomfort: respondents who visit plain forests “Rarely” or “Often” exhibit significantly higher probabilities of reporting discomfort (AME = 0.138 and 0.195, both p < 0.001), while no significant effects emerge for fear or sport avoidance. Visiting forests in hill areas shows a more complex pattern. Frequent visitors (“Always/Exclusively”) display a lower probability of fear (AME = −0.210, p = 0.006), consistent with the idea that familiarity reduces perceived risk. Conversely, they are more likely to report No Activity (AME = 0.299, p = 0.024), potentially indicating selective participation in only certain types of forest activities. They also show lower discomfort (AME = −0.289, p = 0.007), suggesting that increased exposure improves ease but does not necessarily translate into higher activity engagement. Visiting forests in mountain areas does not significantly predict any outcome, possibly reflecting the smaller sample size for this domain.

The four dimensions—fear, discomfort, no activity, and no sport—are strongly interrelated. Fear significantly increases the probability of No Activity (AME = 0.184, p < 0.001), Discomfort (AME = 0.094, p = 0.007), and No Sport (AME = 0.107, p = 0.027). No Activity has one of the strongest effects in the entire table, markedly increasing No Sport (AME = 0.226, p < 0.001) and Discomfort (AME = 0.182, p < 0.001). Discomfort significantly predicts Fear (AME = 0.073, p = 0.078, weak evidence) and No Sport (AME = 0.105, p = 0.041). No Sport also predicts higher Fear (AME = 0.095, p = 0.013) and No Activity (AME = 0.197, p < 0.001). These consistent cross-effects confirm that fear, discomfort, and behavioral avoidance form a mutually reinforcing cluster, where affective responses and behavioral choices interact to shape individuals’ relationships with forests.

All four models exhibit substantial improvements from null to residual deviance, and AIC values indicate satisfactory model fit. The model for Discomfort (AIC = 212.28) performs particularly well, likely reflecting the relatively higher number of events for this outcome.

Overall, the findings highlight that individual experiences and behavioral patterns related to forest use—rather than demographic characteristics—play the most substantial role in shaping fear, discomfort, and activity avoidance, suggesting that interventions aimed at increasing familiarity and positive engagement with forest environments may be more effective than demographic targeting.

4. Discussion

This study provides new insights into attitudes, behaviours, and socio-demographic profiles associated with health and wellness-oriented forest use among residents of Northern Italy. Overall, the results indicate that motivations related to psychophysical well-being constitute the strongest drivers of forest engagement, supporting earlier research showing that stress reduction, cognitive restoration, and emotional balance are central incentives for nature visitation [5,6]. The identification of a robust latent dimension—“Health and Wellness-Driven Forest Engagement”—confirms that forest environments are perceived as spaces offering tangible restorative and health-enhancing experiences, thereby aligning with the international evidence on forest therapy and Shinrin-yoku [21,22].

The second latent dimension—“Comfort-Oriented Forest Use”—sheds light on a different attitudinal profile, emphasising accessibility, low physical effort, and ease of movement. This suggests that for a portion of the population, participation in forest-related activities is conditional on environmental comfort and logistical simplicity. Such findings resonate with broader tourism studies showing that perceived accessibility, safety, and low physical demands influence participation rates in nature-based recreation, especially among older adults, families, or individuals with limited outdoor experience [12].

Regression analyses clarify the drivers of these two orientations. Women show stronger wellness-oriented forest engagement, consistent with evidence that they display higher affinity for well-being and restorative nature activities [15]. Psychological well-being motives and the enjoyment of walking and hiking are strong predictors of this first factor, underscoring the experiential nature of wellness-oriented forest use. By contrast, the comfort-oriented profile is weaker and less predictable, suggesting that comfort-seeking behaviours depend more on contextual elements—such as seasonality or forest type—than on socio-demographic attributes.

One of the more intriguing findings concerns the negative association between visiting mountain forests and health/wellness-driven engagement. This may reflect that wellness-oriented forest activities—such as slow walking, sensory immersion, or guided therapeutic sessions—are perceived as more suitable in lowland or accessible environments than in steep or rugged mountain terrains. This interpretation is consistent with the growing literature suggesting that forest therapy programmes are usually implemented in easily accessible and gently sloping forest settings to ensure inclusivity and reduce physical fatigue [19].

The logistic regression on discomfort-related items provides additional nuance. Although only a small proportion of respondents reports strong discomfort, fear or avoidance, those who do express such feelings tend to display consistent patterns across multiple dimensions, suggesting a coherent attitudinal barrier rather than isolated or situational aversions. Importantly socio-demographic variables, including education, have limited explanatory value, indicating that discomfort in forest environments may be driven more by personal attitudes, familiarity with nature, and past experiences than by structural characteristics. This interpretation aligns with evidence that nature familiarity—rather than socio-economic status—plays a key role in shaping ease and confidence in natural settings [27].

Taken together, these findings have several implications for policy and destination planning. First, forest-based health and wellness initiatives should prioritise interventions that leverage the strong demand for restorative, health-enhancing experiences. Programmes grounded in the evidence of psychological benefits—such as guided forest-therapy sessions, mindfulness trails, or multi-sensory interpretive routes—are likely to attract a broad segment of the population. Second, ensuring accessibility and comfort remains essential: well-maintained paths, clear signage, rest areas, and low-gradient trails can reduce barriers for comfort-oriented users. Third, communication strategies should target specific population segments, emphasising stress reduction and emotional well-being for women and younger adults, while addressing safety and accessibility concerns for those exhibiting discomfort or low familiarity with forest environments.

Finally, the study underscores the value of integrating demand-side evidence into mountain development strategies. Forest-based wellness tourism has the potential to support year-round visitation, diversify mountain economies, and generate employment in peripheral areas—outcomes increasingly recognised as essential for resilient mountain development [3].

5. Conclusions

The implications of this study align closely with several targets of the United Nations 2030 Agenda. In particular, forest-based wellness tourism can contribute to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) by encouraging preventive health practices; SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by enhancing the liveability and attractiveness of mountain settlements; SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by promoting low-impact recreational models; and SDG 15 (Life on Land) by reinforcing the socio-cultural value of forest ecosystems and supporting their sustainable management.

Some limitations and directions for future research are inherent to the overall investigative framework and have already been outlined by Visintin et al. [29]. Beyond these considerations, future studies could examine additional dimensions that influence individuals’ propensity to visit mountain and forest environments for health and well-being purposes. Several aspects not addressed in the present work warrant particular attention, including the role of past outdoor experiences and nature connectedness in shaping willingness to participate in forest-based activities; the influence of digital information, social media, and destination communication strategies on expectations and motivations; and the effects of cultural norms, lifestyle orientations, and environmental value systems on the adoption of wellness practices in natural settings.

Further research would also benefit from longitudinal and comparative approaches, including cross-regional studies within and beyond alpine contexts, to capture temporal dynamics and territorial variability. Moreover, integrating economic impact assessments and geospatial modelling would support a more comprehensive understanding of how forest-based wellness tourism contributes to sustainable mountain development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P. and I.B.; methodology, formal analysis, L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P., I.B. and R.D.; writing—review and editing, L.P., I.B. and R.D.; supervision, I.B. and L.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU, in the framework of the consortium iNEST—Interconnected Nord-Est Innovation Ecosystem (PNRR, Missione 4 Componente 2, Investimento 1.5 D.D. 1058 23/06/2022, ECS_00000043—Spoke1, RT2, CUP I43C22000250006). The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union, nor can the European Union be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Institution Institutional Committee due to Legal Regulations. This study involved nonsensitive, anonymized socioeconomic data and did not include clinical procedures or vulnerable populations. The research was conducted in full compliance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation—GDPR) and national data protection laws, ensuring the anonymity and voluntary participation of all subjects. Therefore, ethical approval was not required according to institutional and national guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.2 for English language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AME | Average Marginal Effect |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| MAR | Missing at Random |

| MNAR | Missing Not at Random |

| MSA | Measure of Sampling Adequacy |

References

- Liao, C.; Zuo, Y.; Xu, S.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Dimensions of the health benefits of wellness tourism: A review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1071578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Težak, D.A. Wellness and healthy lifestyle in tourism settings. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, R.Y.M.; Huang, X. Sustainable Mountain-Based Health and Wellness Tourist Destinations: The Interrelationships between Tourists’ Satisfaction, Behavioral Intentions, and Competitiveness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.B.; Bhaumik, A.; Ojha, S.K.; Dhungana, B.R.; Chapagain, R. Mountain Route Tourism and Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Nature tourism and mental health: Parks, happiness, and causation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Zhu, S.; Lu, D.; Ieong, C. A Bibliometric and Visualization Analysis of Forest Therapy Research: Investigating the Impact of Forest Environments on Human Physiological and Psychological Well-Being. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 7, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debarbieux, B.; Rudaz, G. The Mountain: A Political History from the Enlightenment to the Present; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlik, M. The Spatial and Economic Transformation of Mountain Regions: Landscapes as Commodities; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, R.; Scott, D.; Abegg, B.; Pons, M.; Aall, C. A critical review of climate change risk for ski tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1343–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, T.; Gartner, W.C. Winter tourism in the European Alps: Is a new paradigm needed? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Tyrväinen, L. Frontiers in Nature-Based Tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor Recreation, Nature-Based Tourism, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Gon Kim, W. Emerging trends in wellness tourism: A scoping review. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.; Pforr, C. Wellness Tourism: A Destination Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020—Key Findings; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. European Forest Ecosystems: Key Allies in Sustainable Development; European Environment Agency–EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; An, C.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H. The Relationship between the Restorative Perception of the Environment and the Physiological and Psychological Effects of Different Types of Forests on University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Takayama, N.; Katsumata, M.; Takayama, H.; Kimura, Y.; Kumeda, S.; Miura, T.; Ichimiya, T.; Tan, R.; Shimomura, H.; et al. Impacts of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) in Female Participants with Depression/Depressive Tendencies. Diseases 2025, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanpong, J.; Tsao, C.; Yin, J.; Wu, C.D.; Huang, Y.C.; Yu, C.P. Effects of forest bathing and the influence of exposure levels on cognitive health in the elderly: Evidence from a suburban forest recreation area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 104, 128667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, B. The Mediation Effect of Outdoor Recreation Participation on Environmental Attitude-Behavior Correspondence. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, I.; Deotto, V.; Pagani, L.; Iseppi, L. Forest Therapy as an Alternative and Sustainable Rehabilitation Practice: A Patient Group Attitude Investigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.T.O.; Fok, L. The motivations and environmental attitudes of nature-based visitors to protected areas in Hong Kong. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 21, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Uysal, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Nature-Based Tourism: Motivation and Subjective Well-Being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S76–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.H. Nordic in nature: Friluftsliv and environmental connectedness. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 19, 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangeland, T.; Aas, Ø.; Odden, A. The Socio-Demographic Influence on Participation in Outdoor Recreation Activities—Implications for the Norwegian Domestic Market for Nature-Based Tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 13, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, F.; Bassi, I.; Deotto, V.; Iseppi, L. The Demand of Forest Bathing in Northern Italy’s Regions: An Assessment of the Economic Value. Forests 2024, 15, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W. How demand-side incentive policies drive the diffusion of forest wellness tourism products: An agent-based modeling analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 174, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Damdinsuren, M.; Qin, Y.; Gonchigsumlaa, G.; Zandan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Forest Wellness Tourism Development Strategies Using SWOT, QSPM, and AHP: A Case Study of Chongqing Tea Mountain and Bamboo Forest in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L.; Howard, B.L. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. Determining Sample Size Requirements in EFA Solutions: A Simple Empirical Proposal. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2024, 59, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Structural Equation Modeling with Ordinal Variables Using LISREL. 2005. Available online: www.ssicentral.com/lisrel/techdocs/ordinal.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Revelle, W. R Package, version 2.4.3. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2024.

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.