Abstract

The increasing demand for sustainable and clean-label foods has intensified the search for natural preservatives that are capable of replacing synthetic additives. In this study, an exploratory assessment of two distinct spruce needle aqueous extracts were conducted—an aqueous extract of Picea pungens (NWE-1) and an aqueous extract of Picea abies obtained after prior supercritical CO2 treatment (NWE-2)—and both were investigated as potential bioactive ingredients for plant-based meat analogues. Using UPLC–MS, both extracts were comprehensively characterized, revealing a diverse array of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and glycosides. Even though NWE-2 contained a broader range of bioactive compounds, NWE-1 exhibited superior antibacterial performance (total microbial count (TMC)—4.94 log CFU/g), effectively limiting microbial contamination and ensuring product stability for up to 16 days of storage below the typical spoilage threshold (6.0–7.0 log CFU/g). Sensory analysis indicated that the model plant-based meat analogue matrix tolerated up to 3% (w/w) inclusion of NWE-1 and 5% (w/w) inclusion of NWE-2 before significant degradation of flavor and overall acceptability occurred. By utilizing conifer needles as an underexploited side-stream biomass, this work offers an approach for the valorization of conifer needle material through combined green extraction and food application, contributing to circular and resource-efficient processing concepts. The study provides an exploratory perspective on the potential role of forest-derived resources in the development of natural preservatives and their possible contribution to more sustainable food preservation strategies within a circular bioeconomy framework.

1. Introduction

The sustainable utilization of natural resources has become a global priority in response to environmental degradation, food security challenges, and the growing demand for clean-label products. Within this framework, the recovery of bioactive compounds from renewable plant materials plays a critical role in advancing both circular bioeconomy principles and the development of eco-friendly preservation strategies [1,2,3]. The search for natural alternatives to synthetic additives is particularly relevant in modern food systems, where consumers increasingly seek products that are safe, minimally processed, and derived from sustainable sources [4,5].

Conifer needles represent a renewable biomass resource within forest ecosystems and are rich in diverse bioactive compounds, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, lignans, terpenoids, and organic acids, many of which exhibit antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities [6,7]. Previous studies on spruce (Picea spp.) and pine (Pinus spp.) needle extracts have demonstrated strong free radical scavenging capacity, as well as inhibitory effects against common foodborne pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli [8,9,10,11]. In addition to their bioactivity, conifer needles have attracted increasing attention for their sensory properties and traditional applications, including fermented beverages and extracts [7,12]. Although conifer needle products were traditionally primarily used in home-based products, their high phenolic diversity and pronounced antioxidant activity indicate substantial potential for application in modern food systems [6]. Consequently, the valorization of conifer needle biomass through approaches that integrate traditional knowledge with green extraction strategies may support the development of clean-label preservation concepts and sustainable food products while enhancing product stability.

The extraction strategy strongly influences the recovery, concentration, and functional properties of bioactive compounds from plant materials. Aqueous extraction of the different biomass provides an opportunity to recover the remaining polar metabolites, which may become more accessible after CO2 treatment due to structural disruption of plant matrices or redistribution of bound phenolics. Emerging evidence suggests that supercritical CO2 pre-treatment can enhance the extractability of water-soluble compounds, resulting in more concentrated and biologically active aqueous fractions [13]. Ensuring microbiological safety remains one of the most critical challenges in plant-based meat analogues, as their higher water activity and protein content provide a favorable environment for spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms [14]. The incorporation of natural antimicrobial extracts could therefore serve a dual purpose—extending shelf life while reducing reliance on synthetic preservatives. Conifer needle extracts, with their complex mixture of phytochemical compounds, may act as multifunctional agents that are capable of inhibiting microbial proliferation and delaying quality deterioration during storage [9,15]. However, the detailed effects of sequential extraction order on the chemical composition and antimicrobial functionality of conifer needle extracts remain insufficiently characterized.

In addition to the growing demand for sustainable food preservation strategies, this study aimed to investigate the chemical composition and antimicrobial potential of spruce needle aqueous extracts from (Picea pungens) and (Picea abies). Accordingly, the inclusion of two spruce species reflects the broader context of valorizing underutilized conifer needle residues originating from both forestry operations (Picea abies) and ornamental or domestic sources (Picea pungens), thereby enabling a wider perspective on potential biomass streams for value-added applications. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS) was applied to identify and characterize bioactive compounds, while antibacterial assays were performed to assess the inhibitory effects against selected foodborne pathogens. Additionally, sensory evaluation of plant-based meat analogues enriched with these extracts was conducted to evaluate their impact on product quality and consumer acceptability. This work contributes to the advancement of green extraction technologies and the development of natural preservative systems for sustainable, clean-label food products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Spruce Needles

The blue spruce (Picea pungens) needles used in this study originated from branches collected in February 2024, which were designated for disposal at green waste composting facilities. Prior to collection, the trees had been cultivated for approximately 15 years at a local family-owned tree nursery located in the southwestern region of Lithuania. The general morphological and compositional characteristics of these needles have been described in our previous studies [9]. Freshly cut branches were rinsed with tap water to remove surface impurities and air-dried at room temperature (~20 °C) for 12 h. Subsequently, the needles were manually separated from the twigs and ground using an IKA Batch Cutting/Impact Mill (Eppingen, Germany). Each milling session lasted 3 min at a rotational speed of 25,000 rpm. The milled biomass was then air-dried for 24 h at an ambient temperature (23 ± 2 °C), and the process was repeated until all collected material had been processed.

The Norway spruce (Picea abies) [16] obtained from the Biomass Technology Centre (BTC) at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Umeå, Sweden, was used for supercritical CO2 extraction followed by water extraction. The fractionation process is described in detail by Tienaho et al. (2024) [16]. Green needles were separated from branch material in three steps. First, branches were chipped to allow feeding into a pilot cyclone, where the airflow impact separated needles from the remaining material. The resulting fraction was then mechanically sieved, and particles ≤4 mm were collected for further processing. Fresh material was sealed in an airtight plastic bag and stored at −20 °C until further processing.

2.2. Preparation of Spruce Needles Water Extract (NWE)

For two types of samples, distilled water was used as the extraction solvent at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 20 L/kg. The extraction was carried out at 100 °C for 300 min under continuous stirring in a thermostat reactor. The detailed preparation of the extracts is given below:

Sample NWE-1: Obtained from untreated (Picea pungens) spruce needles.

Detailed extraction is discussed in our previous work [9]. After extraction, the solution was cooled down to room temperature (20–22 °C) for 30 min. First, the solution was filtered through a Whatman filter paper. After large particle separation, the extract was filtered through a glass filter filled with zeolite to remove the precipitated particles. The resulting water extract, designated as sample NWE-1, was stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Sample NWE-2: Obtained from (Picea abies) spruce needles after supercritical CO2 extraction.

Prior to supercritical CO2 extraction, the needle-rich fraction was air-dried, and the final solids content of the dried material was determined to be 94.2%. A batch of 938.7 g (dry weight) was loaded into the reactor of a supercritical fluid pilot plant (Chematur Ecoplanning, Pori, Finland). The reactor pressure was gradually increased to 350 bar, the temperature was set to 50 °C, and the supercritical CO2 flow rate was approximately 0.5 L/min. Wax fractions were collected every 15 min and weighed. The total extraction time was 90 min, yielding approximately 2.5% wax. Following CO2 extraction, the nearly wax-free residue was subjected to water extraction. The spruce needles were extracted in a 2 L Büchi Glas Uster stirred autoclave (Büchi AG, Uster, Switzerland). The resulting water extract, designated as sample NWE-2, was stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Identification of Bioactive Components Using the Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography—Mass Spectrometry (UPLC–MS)

A non-targeted screening strategy was employed to identify bioactive compounds using ultra-high-resolution quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHR-Q-TOF-MS). Chromatographic separation was carried out on an Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, CT, USA) in tandem with a Bruker maXis Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) [17]. For analysis, an Acquity BEH C18 column (1.7 µm, 100 × 2.1 mm), maintained at 40 °C, was utilized. Mobile phase A consisted of 0.4% formic acid in water, and mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The gradient program was as follows: 0–6 min, 98% A; 6–14 min, 98–70% A; 14–16 min, 70–30% A; 16–17 min, 0% A; and at 17 min, re-equilibrated to 98% A. The flow rate was set at 0.4 mL/min, with a 2 µL injection volume.

Mass spectrometric data were acquired using an electrospray ionization (ESI) source in negative ion mode, scanning an m/z range of 100–1500. Instrument settings included a capillary voltage of +4500 V, nebulizer pressure of 2.0 bar, and nitrogen gas flow at 10 L/min. Full scan data were recorded at a rate of 2 Hz. System control, data acquisition, and processing were performed using Compass 1.3 (HyStar 3.2 SR2) software. Compound identification was achieved by matching accurate m/z values to molecular formulas in the ChemSpider database.

2.4. Agar Well Diffusion Method

The antimicrobial properties of the extracts were assessed using the agar well diffusion technique against several common foodborne pathogens. For testing, extracts were diluted with water at ratios of 1:0, 1:1, and 1:3. The initial extract concentrations were 16 mg/mL, and after dilution, 8 and 4 mg/mL, respectively. Sterile plate count agar was inoculated with a 0.5 McFarland standard suspension of each pathogen, poured into Petri dishes, and allowed to solidify. Wells of 6 mm diameter were aseptically punched into the agar and filled with 50 µL of the prepared extract solution.

Samples inoculated with E. coli ATCC 8739, S. aureus subsp. aureus ATCC 25923, S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028, and L. monocytogenes ATCC 13932 were incubated at 37 °C, while those containing B. cereus ATCC 11778 were incubated at 30 °C. After 24 h, antimicrobial activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the wells and the surrounding inhibition zones [18]. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviations.

2.5. Model Plant-Based Meat Analogue Matrix Preparation

The model meat analogue matrix was prepared from three principal components: 35% textured soy protein (TSP), 45% water, and 20% refined rapeseed oil. The samples were prepared by first mixing the water with the TSP and allowing it to fully hydrate. The mass was held for 40 min at approximately 20 °C before incorporating the rapeseed oil. Samples (Figure 1) were subsequently formed into 120 g portions that were pressed into a 9 cm diameter patty shape, suitable for burgers, using a mold with a removable base.

Figure 1.

Plant-based meat analogues prepared for cooking. (A) control sample, (B) sample with 5% NWE-1, and (C) sample with 5% NWE-2.

The nutritional parameters of the model matrix were as follows (per 100 g): 20.42% fat (of which 2.55% saturated fatty acids), 9.45% carbohydrates (of which 3.01% sugars), 3.08% dietary fiber, 17.15% protein, and 0.0035% salt.

In the samples containing the investigated extracts, the water component was proportionately replaced by the extract based on mass. The extract concentrations in the final samples were 0.5%, 1%, 3%, and 5% (w/w) of the total final mass, covering a range that was selected to evaluate both antimicrobial performance and upper sensory acceptance thresholds that were relevant for potential multifunctional ingredient applications.

For microbiological analysis, the weighed and formed samples were vacuum-sealed and stored at +4 °C. Samples intended for sensory evaluation were formed, cooked at 180 °C for 10 min, and presented to the expert evaluators after preparation, ensuring microbiological safety for sensory assessment. The matrix containing only water served as the control sample.

2.6. Sensory Evaluation Methodology

For the assessment of sensory attributes, a product sensory profile was developed, evaluating the intensity of the attributes according to the descriptive analysis method (ISO 13299:2016) [19]. A panel of expert assessors analyzed the presented samples of the model plant-based meat analogue matrix, evaluating the intensity of selected attributes. A 9-point scale for attribute intensity was chosen to identify even minor differences between the samples.

Using the data obtained during the evaluation and applying methods of mathematical statistics, a sensory profile showing the intensity of each attribute was constructed for every product. Due to the specific nature of the product under investigation, the study focused on evaluating the following product attributes: overall appearance acceptability, overall odor acceptability, overall flavor acceptability, overall texture acceptability, overall aftertaste acceptability, overall product acceptability, odor intensity, flavor intensity, bitter flavor intensity, and off-flavor intensity. A crossover presentation design was used when constructing the sensory profile. The intensity of each attribute in the tested products was evaluated on a 9-step graded numerical scale: 1—attribute not perceived, 5—moderately expressed, and 9—attribute perceived at maximum intensity. The testing involved a panel of 12 expert assessors. The assessors were selected and trained in accordance with the (ISO 8586:2012) standard [20]. The evaluation was conducted under blind conditions in the sensory analysis booths, which are equipped according to the requirements of (ISO 8589:2007) [21]. For the evaluation of the results, the data were statistically processed using the software package “Fizz Calculations”.

2.7. Methods of the Microbiological Analysis

Microbiological safety was evaluated for both the spruce needle extracts and the meat-analogue samples that were stored for 14 days. The total aerobic mesophilic count (TAMC) was determined according to the ISO 4833-1:2013 [22].

2.8. Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Average values and standard deviations were calculated using MS Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corp, Albuquerque, NM, USA), while statistical analysis was performed using the Statgraphics Centurion 19 statistical package. One-way analysis of variation (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test, was performed to determine significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. UPLC–MS Profile of Bioactive Compounds in Conifer Needle Aqueous Extracts

Spruce needles are a rich source of organic acids, flavonoids, and other phenolic compounds that can provide valuable functional properties when applied in food systems. Picea pungens and Picea abies were chosen as model species, differing in geographical origin and composition of biologically active compounds. This approach allowed us to assess how both the botanical origin of the spruce needles and the applied processing method influence the properties of the resulting aqueous extracts. In this study, two distinct spruce needle extracts were evaluated: an aqueous extract of Picea pungens prepared without prior treatment (NWE-1), and an aqueous extract of Picea abies obtained after supercritical CO2 extraction (NWE-2). The chemical composition and bioactive potential of both extracts were characterized using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS).

This analysis enabled the identification of both primary metabolites and polyphenolic derivatives that were responsible for the functional properties of the extracts. The identified bioactive constituents and their distribution in both extracts are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Non-targeted analysis UPLC-Q-TOF data of the main constituents of NWE-1.

Table 2.

Non-targeted analysis UPLC-Q-TOF data of the main constituents of NWE-2.

In both spruce needle extracts, several of the same compounds were identified, including malic acid (C4H6O5), shikimic acid (C7H10O5), quinic acid (C7H12O6), citric acid (C6H7O7), caffeoyl-glucoside (C15H18O8), proanthocyanidin (C30H26O12), pungenin (C14H18O8), vanillin (C8H7O3), and disuccinoyl-caffeoylquinic acid (C26H33O13). These compounds comprise a combination of organic acids and polyphenolic derivatives that form the core bioactive composition of Pinea plant extracts [6,23]. The presence of malic, shikimic, quinic, and citric acids reflects typical primary plant metabolites involved in organic acid and phenylpropanoid pathways, contributing to the overall stability and mild antimicrobial properties of the extracts [24]. Phenolic constituents such as protocatechuic acid, caffeoyl-glucoside, and proanthocyanidin are well-known for their antioxidant and radical-scavenging capacity, supporting the extracts’ oxidative stability potential. Pungenin [25], a characteristic of coniferous species, contributes insecticidal, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects [26], while vanillin provides additional aromatic and preservative functionality [27]. The consistent occurrence of these bioactive molecules across both extraction techniques demonstrates a stable phytochemical profile that is characteristic of Picea genus plants’ extracts, which has antioxidant and antimicrobial efficiency and supports their potential use in functional food formulations.

During the extraction of spruce needles, it was observed that several phenolic compounds previously identified in the primary samples, such as protocatechuic acid glucoside (C13H16O9), salicylic acid glucoside, pungenin dimer (C13H16O8), lignan pentoside (C24H32O11), epicatechin-rhamnosyl-hexoside (C25H34O12), veronicastroside (C27H30O15), and cynaroside (C27H30O15), were not detected in the aqueous extract obtained after supercritical CO2 extraction. The absence of these compounds in the aqueous extract is likely related to the two-stage extraction. Supercritical CO2 extraction, especially when ethanol is used as a co-solvent, can transfer some of the polyphenolic and acylated flavonoid glycosides to the non-polar phase, leaving little for further extraction with water [13]. It can be assumed that the complete absence of the aforementioned compounds in the aqueous extract after CO2 extraction is a complex phenomenon related to their chemical instability, botanical origin, and solubility differences, as well as the effect of the previous extraction step on the sample composition.

After performing a supercritical CO2 extraction of Picea abies spruce needles (Table 2) and subsequently obtaining an aqueous extract, it was found that compounds appeared in it that were not detected in the extracts obtained by using only aqueous extraction of Picea pungens.

Among these compounds, several biologically active metabolites have been identified: rhamnosyl-rhamnose (C12H22O9), epigallocatechin (C15H14O7), salicylic acid (C7H6O3), p-coumaroylquinic acid (C16H18O8), catechin (C15H14O6), lignan (C18H20O5), polygalic acid (C29H44O6), asperuloside (C27H38O13), isorhamnetin-O-hexoside (C22H22O12), and phenylpropanoid glycoside (C22H38O10). The appearance of these compounds only after CO2 extraction indicates that supercritical conditions change the structure of the plant matrix and the availability of the compounds. During CO2 extraction, lipophilic components (terpenes, waxes, chlorophylls) are removed, which increases the permeability of the cell walls and facilitates the subsequent diffusion of polar metabolites—flavonoids, iridoids, phenolic acids, and glycosides—into the aqueous solvent [28]. In addition, high pressure and temperature during CO2 extraction can initiate chemical transformations (e.g., hydrolysis of glycosides or esterification reactions), leading to the formation of new, more polar derivatives, such as catechin (C15H14O6) or salicylic acid (C7H6O3). Therefore, it can be argued that the effect of supercritical CO2 extraction results in both an increase in the structural permeability of the plant matrix and the transformation of certain compounds into more water-soluble forms that are not detected during direct aqueous extraction without implying a direct enhancement of bioactivity [29]. In a study [30] conducted on Eryngium maritimum, researchers compared several eco-friendly extraction techniques, including conventional water and ethanol reflux extraction and alternative green technologies, such as supercritical fluid extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasound-assisted extraction, and combined ultrasound–microwave extraction. The extracts were evaluated according to their extraction yield, chemical composition, and biological activities such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-collagenase, and anti-tyrosinase effects. The authors found that supercritical fluid extraction produced the strongest biological activities, followed by water reflux extraction, suggesting that different techniques preferentially extract distinct groups of metabolites. Despite variations in composition, water reflux extraction was considered to be the most balanced and sustainable approach, providing an optimal compromise between extraction efficiency, energy consumption, and biological performance. Other authors have also compared different aqueous and supercritical CO2 extraction methods to assess their impact on the recovery of biologically active compounds. Alwazeer et al. [31] found that they did not observe a significant difference in the total amount of phenolic compounds between simple aqueous and CO2 extraction. In addition to differences arising from botanical origin, the results indicate that the extraction approach itself plays a crucial role in shaping the qualitative composition of the obtained fractions. Although higher concentrations of biologically active compounds are often associated with CO2-based extraction methods, optimization of extraction parameters may lead to comparable overall extraction efficiency across different methods, while still yielding extracts that differ qualitatively in their chemical profiles.

Studies comparing aqueous extraction performed after prior CO2 treatment of plant biomass are scarce, particularly for conifer needles. Although the present study examined different conifer species, these initial findings nevertheless provide valuable information on how processing strategies may influence extract composition. This highlights the importance of conducting more focused investigations on conifer needles of the same botanical origin, where such effects could be evaluated without interspecies variability, thereby enabling a clearer understanding of processing-related differences and their relevance for food applications.

3.2. Antimicrobial Properties of Blue Spruce Needle Water Extracts

In recent years, growing consumer demand for clean-label and naturally preserved foods has driven the search for effective plant-based antimicrobial agents. In this work, spruce NWE were tested for antimicrobial activity against the most common food pathogens—Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp. (Table 3)—in the context for application in replacing common food preservatives in novel food production.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of the spruce needle aqueous extracts.

In this investigation, both extracts show antimicrobial properties that are mostly against Gram-positive bacteria, notably against S. aureus subsp. aureus ATCC 25923 and B. cereus ATCC 11778. Single-step extract NWE-1 displays stronger antimicrobial characteristics compared to two-steps extract NWE-2. Given the high concentration of the extracts, consideration of the dilution factor is essential for evaluating their practical and economically efficient application. In comparing the characteristics of the two extracts, the dilution factor exhibited a relatively minor role for NWE-1 compared to NWE-2. Notably, 1:1 dilution produced only slightly reduced inhibition zones for Gram-positive strains, while the 1:3 dilution lost effectiveness solely against S. aureus subsp. aureus. Notably, even the most concentrated extract samples did not inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, although NWE-1 extract had a minor antimicrobial effect on Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028.

Needle water extracts’ notable effectiveness against foodborne pathogens can be attributed to multiple mechanisms of action, often working in combination, driven by the specific compounds identified within the extract. Effectiveness against Gram-positive bacteria can be partially explained by their cell wall structure, as peptidoglycan is the primary structural component of these cell walls and lacks the protective outer membrane found in Gram-negative species [32].

Phenolic compounds such as protocatechuic acid and caffeoyl-glucoside (Table 1 and Table 2) have a capacity to disrupt the bacterial cell membrane, thus impairing it by increasing its permeability, leading to leakage of ions and intracellular contents. It also interferes with membrane-bound enzymes, compounding its antimicrobial effect. Their antioxidant properties also contribute to oxidative stress within bacterial cells, further enhancing their antimicrobial action. Proanthocyanidins-condensed tannins bind to membrane proteins and lipids, disrupting membrane integrity. They can cause cell lysis by weakening the structural cohesion of the bacterial envelope. These effects are particularly potent against Gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Bacillus cereus [33,34,35].

Specific flavonoids such as epicatechin-rhamnosyl-hexoside, proanthocyanidins, and cymaroside have demonstrated inhibitory effects against common food pathogens [36]. Notably, their antimicrobial effects arise from multiple, often synergistic, mechanisms that target essential bacterial structures and processes. One of the primary modes of action is membrane disruption [37]. Flavonoids like catechin, epicatechin, and proanthocyanidins can integrate into bacterial lipid bilayers, altering membrane fluidity and permeability [38]. Beyond membrane effects, flavonoids are known to inhibit DNA and RNA synthesis by targeting enzymes like DNA gyrase and RNA polymerase, which are critical for bacterial replication and transcription [39]. Some flavonoids also bind to ribosomal subunits, blocking protein synthesis and halting bacterial growth [40]. These multi-targeted actions make flavonoids particularly effective against Gram-positive bacteria and are more susceptible to structural and metabolic disruption. This varied composition of extracted phytochemicals with different pathways for cell disruptions has potential as a substitute for synthetic food preservatives.

3.3. Impact of Extracts on Sensory Characteristics of a Model Plant-Based Meat Analogue

Since spruce needles are rich in polyphenols and terpenes, which are known to cause bitterness or astringency, the main issue for industrial application could be the deterioration of sensory properties. According to the data obtained in the study [12], depending on the extraction method, coniferous extracts may also have a positive effect on the sensory properties of the product, imparting the aroma that is characteristic of aromatic herbs. In this study, it was important to determine the maximum concentration of the extracts studied in the model matrix that would not have a negative effect on its sensory properties: the intensity of the bitter taste and the intensity of the off flavors are particularly important. It is important to mention that although the resulting extracts gain a characteristically specific color, their inclusion, even at the highest concentration, did not yield an eye-observable difference in the product, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

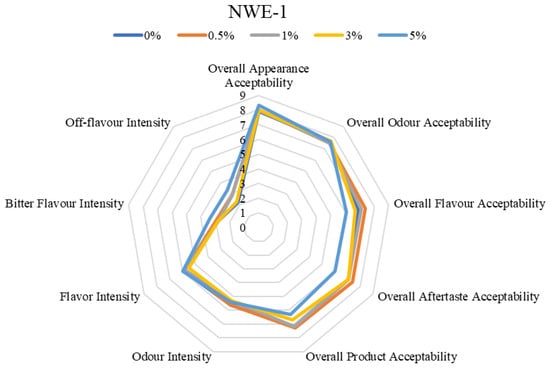

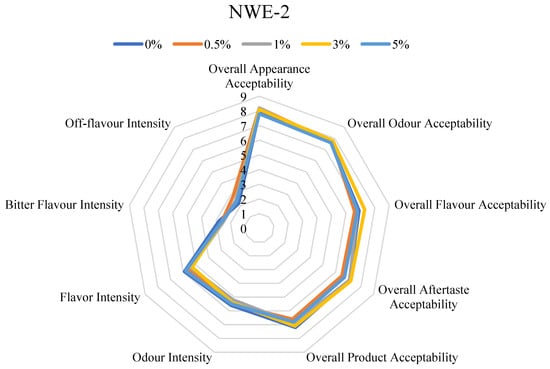

Among all formulations studied, overall appearance acceptability and odor acceptability remained high at ≥7.5 (Figure 2). It can be noted that the addition of the extracts in the meat analogues, regardless of their concentration, did not have an effect on the visual appeal. However, differentiation emerged when evaluating the flavor-related attributes and overall product acceptability. Sample NWE-1 demonstrated a drop in overall flavor acceptability at the 5% concentration 6.1 ± 2.4. Further, the overall product acceptability also fell to 6.3 ± 2.3 at 5% concentration. The overall aftertaste acceptability in both extracts (NWE-1 and NWE-2) fluctuated between values of 7–8, regardless of concentration, and coincided with the control sample (Figure 2). Despite that, a notable variance was observed in NWE-1 at 5% concentration, as its overall aftertaste acceptability decreased to 6.0. The decrease in acceptability, which ultimately limited the inclusion levels, was primarily driven by changes in off-flavor intensity and bitter flavor intensity, which are typical challenges when incorporating coniferous plant-derived functional compounds [41].

Figure 2.

Sensory characteristics of model meat analogue sample.

It can be assumed that NWE-1 has more biologically active compounds at a higher concentration [7] that can be associated with objectionable aromas and flavors in foods (e.g., proanthocyanidins [42]) compared to NWE-2. To confirm this hypothesis, extract profiling should be performed not only qualitatively but also quantitatively, followed by a repeat sensory study. This analysis directly supports the choice of 3% for NWE-1 and 5% for NWE-2 as optimal concentrations for antimicrobial activity testing in the model food matrix, balancing functional ingredient inclusion with sensory quality maintenance.

3.4. Model Plant-Based Meat Analogue Microbial Dynamics Assessment Throughout Storage

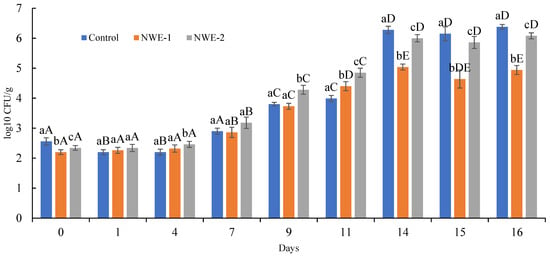

The effectiveness of water-based needle extracts NWE-1 and NWE-2 in preserving the microbiological safety of the plant-based meat analogue was assessed by monitoring the main foodborne pathogens, as well as the total microbial count, over a 16-day storage period. Although throughout the testing period, no food pathogens were detected, the total microbial count proliferation was tracked. These data are detrimental in estimating the products’ shelf stability and verifying the potential antimicrobial action indicated by the extracts.

The initial microbial counts (Figure 3) were relatively low, ranging from 2.20 to 2.56 log CFU/g across all samples. This trend kept up to day 7; microbial growth remained minimal, with counts not exceeding 3.18 log CFU/g. A notable increase in microbial proliferation was observed from day 9 onward, which was particularly evident by day 11, when the NWE-2-enriched sample reached 4.85 log CFU/g and the control sample reached 3.99 log CFU/g. By day 14, the control exhibited a sharp escalation to 6.28 log CFU/g, staying within the typical spoilage threshold (6.0–7.0 log CFU/g) [43], while the NWE-1 and NWE-2 samples maintained lower values of 5.04 and 6.00 log CFU/g, respectively. This pattern continued through to day 16, with microbial loads of 6.38 log CFU/g for the control, 4.94 log CFU/g for NWE-1, and 6.08 log CFU/g for NWE-2. These findings clearly indicate that both plant extracts effectively delayed microbial proliferation compared to the untreated control, with NWE-1 demonstrating superior inhibitory activity throughout the storage period.

Figure 3.

Meat analogue microbial dynamics assessment. Different lowercase letters (a–c) indicate statistically significant differences among the control and the two extracts within the same storage day (p < 0.05). Different uppercase letters (A–E) indicate statistically significant differences among different storage time points within the same sample (p < 0.05).

Previous work [9] has suggested that needle extracts can be effectively employed as natural preservatives due to their high content of bioactive compounds, such as phenolics, flavonoids, and proanthocyanidins, which possess well-documented antimicrobial properties. These compounds are known to disrupt microbial cell membranes, interfere with enzymatic activity, and inhibit oxidative degradation processes that contribute to product spoilage. Building on this evidence, the present study further supports the preservative potential of such extracts, as NWE-1 demonstrated a clear capacity to delay microbial growth in the plant-based meat analogue during storage, reinforcing the role of conifer needle extracts as promising natural alternatives to synthetic preservatives in extending the shelf life of perishable, plant-based food systems.

3.5. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

This study provides preliminary knowledge on the potential application of conifer needle extracts as natural preservatives for food systems. In addition to chemical and antimicrobial evaluation, particular attention was given to sensory evaluation and acceptability, which represents a critical factor for practical food applications and supports the future relevance of this study. Although exploratory in nature, the results indicate promising prospects for further development and potential industrial applicability of conifer needle-derived extracts. In the present work, aqueous extraction conditions were selected based on our previously published studies, in which the extraction process was systematically optimized [9]. In contrast, the supercritical CO2 pretreatment that was applied for the preparation of the NWE-2 extract was guided by recent scientific reviews, rather than experimental optimization [44]. Therefore, future studies should focus on optimizing the primary supercritical CO2 pretreatment conditions in order to further refine extract composition and functional performance. The critical factor that warrants further investigation is the influence of conifer species variability. In future research, harmonizing plant material selection by applying identical pretreatment and extraction strategies to different conifer species would enable improved comparability and a more robust assessment of species-dependent effects. The present exploratory findings establish an essential foundation for understanding the potential of conifer needle extracts as natural food preservatives. Despite process and raw material optimization, one of the most promising future research directions should be focused on toxicological and safety assessments that could become a solid basis for the industrial and legal applicability of plant extracts.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that spruce needle extracts obtained from Picea pungens and Picea abies, despite differences in preparation approach, exhibit a consistent, genus-specific bioactive compound profile that is predominantly composed of organic acids and polyphenolic derivatives, confirming the strong potential of Picea needle biomass as a functional ingredient source for food systems. Antimicrobial evaluation of both extracts revealed notable activity against Gram-positive foodborne pathogens, particularly S. aureus and B. cereus. The NWE-1 extract exhibited superior antimicrobial efficacy and more effectively delayed microbial proliferation in a model plant-based meat analogue over a 16-day storage period.

Sensory analysis further demonstrated that flavor attributes (bitterness and off-flavor intensity) were the primary factors limiting the extract inclusion levels in the meat analogue. NWE-2 could be incorporated at up to 5%, whereas NWE-1 remained acceptable only up to 3% without compromising the overall product quality.

In conclusion, the integration of antibacterial activity assessment, chemical profiling, and sensory evaluation demonstrates that conifer needle extract provides antimicrobial properties while maintaining an acceptable sensory profile at concentrations that are relevant for application as natural preservation agents for sustainable alternative protein systems. While no safety assessments were conducted in the present study, the available literature indicates that none of the identified antimicrobial compounds associated with spruce needle extract have been reported to exhibit toxic effects in humans. The preliminary studies of the two different extracts presented in the work provide a promising basis for further studies, which require further standardization of extraction conditions and conifer species in order to optimize the process for further industrial applicability and regulation. The findings of this study provide evidence that extraction technology selection can be strategically utilized to modulate the spectrum of bioactive compounds and sensory tolerance, thereby enabling subsequent research stages focusing on quantitative metabolite profiling and scale-up assessment under industrial conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ž.G., R.K., and K.A., Methodology: Ž.G., D.Č., A.Z., R.K., and K.A., Formal analysis and investigation: K.A.; Writing—original draft preparation: Ž.G. and K.A.; Writing—review and editing: Ž.G., R.K., L.T., D.Č., and K.A. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Ž.G., D.Č., A.Z., R.K., and K.A. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ž.G. and K.A. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2021–2027 Interreg Baltic Sea Region Program project “Innovation in forestry biomass residue processing: towards circular forestry with added value products” (CEforestry) grant No. C023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involved a trained panel of expert assessors who evaluated food samples according to standardized descriptive sensory analysis procedures. According to the regulations of the authors’ institution, sensory evaluation studies of this type are exempt from formal ethics committee review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

- De Oliveira, P.R.S.; Da Silva, K.C.A.; Amorim, G.A.; Yamaguti, S.T.; Saloni, D.; Pereira, A.K.S.; Júnior, A.F.D. Agro-industrial waste as a potential raw material for multiple products and promotion of a circular economy. In Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Zárate, P.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Abraham, A.R.; Haghi, A.K. The Food-Energy-Water Triangle for Sustainable Development; Apple Academic Press eBooks: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonaitytė, K.; Kruopienė, J. Towards Circularity in Agriculture: A Case of Bioactive Compound Recovery from Sea Buckthorn Residual Leaves and Twigs. Processes 2025, 13, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Abidin, M.R.Z.; Wong, J.X.; Dong, H.; Karim, S.A. Are Food Additives Utilized Judiciously? Novel Insights into Health Risks, Benefits, and Ethical Boundaries. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, B.; Rajinikanth, V.; Narayanan, M. Natural plant antioxidants for food preservation and emerging trends in nutraceutical applications. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavins, L.; Almonaitytė, K.; Šalaševičienė, A.; Zommere, A.; Spalvis, K.; Vincevica-Gaile, Z.; Korpinen, R.; Klavins, M. Strategy of Coniferous Needle Biorefinery into Value-Added Products to Implement Circular Bioeconomy Concepts in Forestry Side Stream Utilization. Molecules 2023, 28, 7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidelis, M.; Tienaho, J.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pihlava, J.; Rudolfsson, M.; Järvenpää, E.; Imao, H.; Hellström, J.; Liimatainen, J.; Kilpeläinen, P.; et al. Spruce, pine and fir needles as sustainable ingredients for whole wheat bread fortification: Enhancing nutritional and functional properties. LWT 2024, 213, 117055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandulovici, R.C.; Gălăţanu, M.L.; Cima, L.M.; Panus, E.; Truţă, E.; Mihăilescu, C.M.; Sârbu, I.; Cord, D.; Rîmbu, M.C.; Anghelache, Ş.A.; et al. Phytochemical Characterization, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity of the Vegetative Buds from Romanian Spruce, Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. Molecules 2024, 29, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaižauskaitė, Ž; Klavins, L.; Almonaityte, K. Optimised extraction of bioactive compounds from spruce needles for sustainable applications. Waste Manag. 2025, 201, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, M.; Houde, R.; Stevanovic, T. Non-wood forest products based on Extractives-A new opportunity for Canadian Forest industry Part 2- Softwood forest species. J. Food Res. 2013, 2, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kang, H.K.; Cheong, H.; Park, Y. A Novel Antimicrobial Peptides From Pine Needles of Pinus densiflora Sieb. et Zucc. Against Foodborne Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 662462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumail, A.; Girard, F.; Tanaka, K.H.; Frøst, M.B.; Turgeon, S.L.; Perreault, V. Sensory characterization of conifer-based extracts for culinary uses. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 39, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzyk, F.; Piłakowska-Pietras, D.; Korzeniowska, M. Supercritical Extraction Techniques for Obtaining Biologically Active Substances from a Variety of Plant Byproducts. Foods 2024, 13, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dušková, M.; Dorotíková, K.; Bartáková, K.; Králová, M.; Šedo, O.; Kameník, J. The microbial contaminants of plant-based meat analogues from the retail market. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 425, 110869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziedziński, M.; Dziedziński, M.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Wilk, R.; Ludowicz, D. Antioxidant potential, mineral composition and inhibitory effects of conifer needle extract on hyaluronidase-prospects of application in functional food. J. Elem. 2022, 27, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienaho, J.; Fidelis, M.; Brännström, H.; Hellström, J.; Rudolfsson, M.; Das, A.K.; Liimatainen, J.; Kumar, A.; Kurkilahti, M.; Kilpeläinen, P. Valorizing assorted logging residues: Response surface methodology in the extraction optimization of a green Norway spruce Needle-Rich fraction to obtain valuable bioactive compounds. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienaitė, L.; Pukalskas, A.; Pukalskienė, M.; Pereira, C.V.; Matias, A.A.; Venskutonis, P.R. Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Defatted Sea Buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides L.) Berry Pomace Fractions Consecutively Recovered by Pressurized Ethanol and Water. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2015, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13299:2016; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance for Establishing a Sensory Profile. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 8586:2012; Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Assessors. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ISO 8589:2007; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Design of Test Rooms. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- ISO 4833-1:2013; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms—Part 1: Colony-Count at 30 °C. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Ilek, A.; Błońska, E.; Miszewski, K.; Kasztelan, A.; Zborowska, M. Investigating water storage dynamics in the litter layer: The impact of mixing and decay of pine needles and oak leaves. Forests 2024, 15, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsämuuronen, S.; Sirén, H. Bioactive phenolic compounds, metabolism and properties: A review on valuable chemical compounds in Scots pine and Norway spruce. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 623–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porth, I.M.; De La Torre, A.R. The Spruce genome. In Compendium of Plant Genomes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageroy, M.H.; Jancsik, S.; Yuen, M.M.S.; Fischer, M.; Withers, S.G.; Paetz, C.; Schneider, B.; Mackay, J.; Bohlmann, J. A Conifer UDP-Sugar Dependent Glycosyltransferase Contributes to Acetophenone Metabolism and Defense against Insects. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, G.H.; Andac, M. Recent advances in sustainable biopolymer films incorporating vanillin for enhanced food preservation and packaging. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 2751–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, B.; Kander, R. Supercritical CO2 technology for biomass extraction: Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Erşatır, M.; Poyraz, S.; Amangeldinova, M.; Kudrina, N.O.; Terletskaya, N.V. Green Extraction of Plant Materials Using Supercritical CO2: Insights into Methods, Analysis, and Bioactivity. Plants 2024, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traversier, M.; Gaslonde, T.; Lecso, M.; Michel, S.; Delannay, E. Comparison of extraction methods for chemical composition, antibacterial, depigmenting and antioxidant activities of Eryngium maritimum. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2019, 42, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwazeer, D.; Elnasanelkasim, M.A.; ÇiÇek, S.; Engin, T.; Çiğdem, A.; Karaoğul, E. Comparative study of phytochemical extraction using hydrogen-rich water and supercritical fluid extraction methods. Process Biochem. 2023, 128, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquina-Lemonche, L.; Burns, J.; Turner, R.D.; Kumar, S.; Tank, R.; Mullin, N.; Wilson, J.S.; Chakrabarti, B.; Bullough, P.A.; Foster, S.J.; et al. The architecture of the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall. Nature 2020, 582, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojković, D.S.; Živković, J.; Soković, M.; Glamočlija, J.; Ferreira, I.C.; Janković, T.; Maksimović, Z. Antibacterial activity of Veronica montana L. extract and of protocatechuic acid incorporated in a food system. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhong, K.; Huang, Y.; Qi, H.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, H. Antibacterial Activity and Membrane-Disruptive Mechanism of 3-p-trans-Coumaroyl-2-hydroxyquinic Acid, a Novel Phenolic Compound from Pine Needles of Cedrus deodara, against Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2016, 21, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menikheim, C.B.; Mousavi, S.; Bereswill, S.; Heimesaat, M.M. Polyphenolic compounds in the combat of foodborne infections–An update on recent evidence. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 14, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Plant-Derived antimicrobials and their crucial role in combating antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reygaert, W.C. The antimicrobial possibilities of green tea. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitichalermkiat, A.; Katsuki, M.; Sato, J.; Sonoda, T.; Masuda, Y.; Honjoh, K.; Miyamoto, T. Effect of epigallocatechin gallate on gene expression of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, H.S.; Dinore, J.M.; Alrabie, A.; Thulasiram, H.V. Antimicrobial flavonoid: In silico targeting Escherichia coli DNA gyrase adeptly. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 39, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizumi, Y.; Oishi, M.; Taniguchi, T.; Goi, W.; Sowa, Y.; Sakai, T. The flavonoid apigenin downregulates CDK1 by directly targeting ribosomal protein S9. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karklina, K.; Ozola, L. Sensory assessment and consumer acceptability of confectionery products made with pine cones. Agron. Res. 2025, 23, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Brandão, E.; Guerreiro, C.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; De Freitas, V. Tannins in Food: Insights into the Molecular Perception of Astringency and Bitter Taste. Molecules 2020, 25, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmettler, K.; Waser, S.; Stephan, R. Microbiological quality of plant-based meat-alternative products collected at retail level in Switzerland. J. Food Prot. 2024, 88, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisca, A.; Tanase, C. Approaches to Extracting Bioactive Compounds from Bark of Various Plants: A Brief Review. Plants 2025, 14, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.