Abstract

The article presents a quantitative analysis of the influence of selected material and structural parameters on the results of the life cycle assessment of a tunnel lining. The aim of the study was to evaluate the potential for reducing environmental impacts by decreasing the amount of concrete and reinforcing steel or by modifying the concrete mix composition. The analysis was conducted for two tunneling technologies: TBM and ADECO–RS (14 variants in total). The results indicate that concrete is the dominant factor shaping the environmental impact of the reinforced concrete lining, while reinforcing steel plays a supplementary role, depending on the adopted material variant (4–19%). Despite structural differences, both technologies show a similar level of environmental impacts, which confirms the need for full life cycle analyses and highlights a significant optimization potential within each technology. In the ADECO–RS method, increasing the concrete class did not contribute to reducing environmental impacts, whereas in the TBM method, the use of higher-strength concrete compensated for its higher unit impact by reducing the volume of structural materials. Differences in rankings between indicators confirm the relevance of a comprehensive, multi-criteria analysis in environmental impact assessment.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

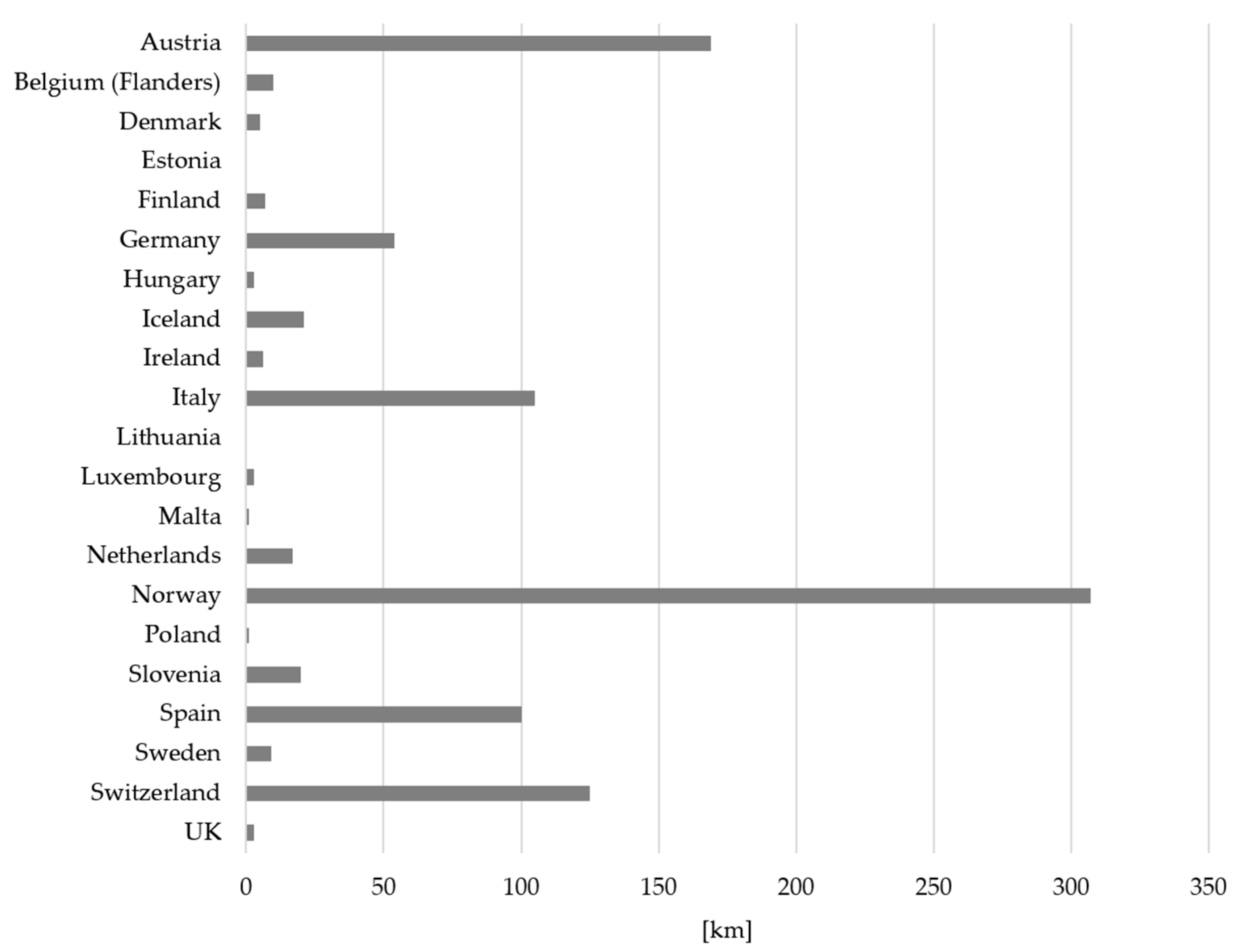

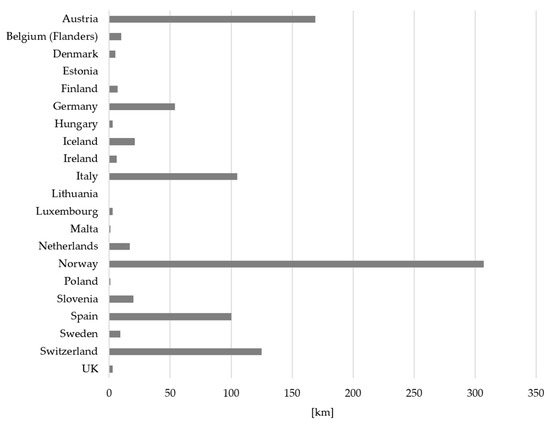

In recent decades, the development of underground infrastructure has become one of the key components of European transport policy. As highlighted in the European Commission report Standardisation needs for the design of underground structures [1], tunneling projects in Europe constitute a significant share of the infrastructure market, and the demand for tunnels remains consistently high [2]. Tunneling plays an essential role in ensuring the continuity and capacity of transport networks, particularly in mountainous regions, cross-border corridors, and densely urbanized areas [3]. In the context of the European transport network, it is worth referring to data from the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN–T), which presents the lengths of road tunnels (over 0.3 km) in individual countries (Figure 1). The dynamic development of tunnel investments is further confirmed by numerous projects carried out in recent years within the TEN–T framework, including both the modernization of existing facilities and the construction of new ones.

Figure 1.

Length of the TEN–T (Roads) network comprising tunnels (2019 r.). Own elaboration based on [4].

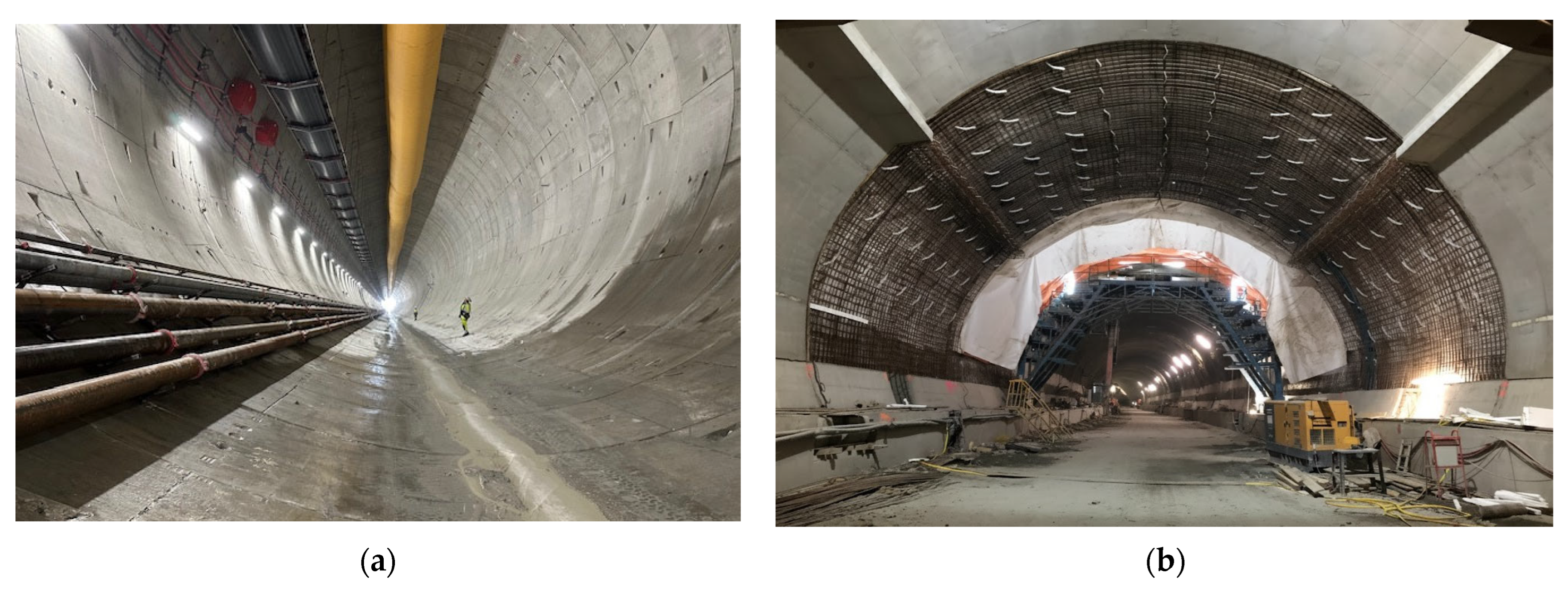

In engineering practice, various tunneling methods are employed, and their selection depends primarily on geological conditions, excavation depth, and the availability of specific technologies [5]. Commonly applied techniques include TBM (Tunnel Boring Machine) [6], NATM (New Austrian Tunnelling Method) [7], ADECO–RS (Analysis of Controlled Deformation in Rocks and Soils) [8], and the Cut-and-Cover method [9]. Among the available technologies, the TBM method is distinguished by a high degree of mechanization and automation of the excavation process. The TBM machine (Figure 2a) [10,11,12], in turn, contrasts with the ADECO–RS technique (Figure 2b), which relies on the controlled use of ground deformations to ensure excavation stability [13]. Despite their structural differences, both techniques are widely used in infrastructure projects and constitute an important component of modern underground construction.

Figure 2.

View of tunnel construction for (a) TBM and (b) ADECO–RS technologies. Own elaboration.

1.2. Environmental Context and Life Cycle Assessment in Tunneling

Contemporary tunneling methods, regardless of the technology applied, must now be evaluated not only in terms of technical efficiency [14,15] and safety, but also in relation to their compliance with the principles of sustainable development and the minimization of environmental impact [16]. In recent years, the European Union’s policy has consistently moved towards integrating environmental considerations into the design and construction of engineering structures. These objectives have been reflected in strategic documents such as the European Green Deal [17] and the Circular Economy Action Plan [18]. A continuation of these initiatives was the adoption of Directive 2022/2464/EU (CSRD—Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) [19], which initially imposed on large enterprises the obligation to disclose non-financial information, including environmental, social, and economic aspects. Consequently, the construction sector, as one of the major emitters, is increasingly required to apply tools that enable the quantitative assessment of environmental impacts, including Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [20,21]. Importantly, sustainability reporting requirements extend not only to large economic entities but also to their suppliers and subcontractors, who form part of the broader value chain. In practice, this translates into the growing relevance of standardized environmental assessment methods, which make it possible not only to identify key emission sources and evaluate the effectiveness of mitigation measures, but also to ensure the comparability and reliability of reporting results. The absence of unified principles leads to inconsistencies in data interpretation and complicates the evaluation of actual progress in the area of sustainable development [22,23]. In response to these requirements, LCA has been increasingly applied to tunneling projects; however, existing studies vary substantially in scope, indicators, and system boundaries, which complicates benchmarking and design-oriented decision making.

1.3. State of the Art and Research Gap

In the context of tunneling engineering, a gradual increase in the application of the LCA method can be observed, although the scope of analyzed indicators and the assumptions adopted remains highly diverse. To clarify the positioning of this study, Table 1 summarizes ten representative tunnel LCA studies published since 2015, distinguishing between different tunneling technologies and presenting, among others, their system boundaries, indicator sets, and key methodological assumptions.

Table 1.

Overview of publications on the environmental impact of different tunnel excavation technologies. Own elaboration.

A comparison of available results indicates that various groups of environmental indicators are considered in the literature. A persistent trend is the simplification of assessments to carbon footprint analysis, a phenomenon also widely observed in other construction sectors (e.g., [34,35]). It is worth noting that in some studies—including review papers [36,37] the concept of Environmental Impact is interpreted more broadly, encompassing not only emissions and resource use but also nuisances associated with the construction process, such as noise, dust generation, or odorous emissions. Most LCA studies focus on stages A1–A5, while the phases related to operation and maintenance, B, are included only sporadically, as in [25].

In most of the analyzed publications, there is no explicit description of the concrete used, including its class or composition. One of the few exceptions is reference [29], in which the concrete classes are stated directly (C45/55 and C80/95). In the study by Rodríguez et al. [30], the authors do not specify concrete classes but propose a model in which the compressive strength is determined as a function of tunnel parameters and rock mass properties. The model-derived value of compressive strength subsequently forms the basis for estimating material demand, which directly translates into the calculation of the carbon footprint. In contrast, the reviewed studies tend to provide a much higher level of detail regarding the excavation process itself, including precise information on machine productivity, fuel consumption, and energy demand, whereas information on the concrete applied in the tunnel lining is typically presented in a more limited or aggregated form. Design-oriented investigations of concrete mix composition (e.g., cement type, SCMs, recycled aggregates) and the role of high-strength concrete in reducing overall impacts through material savings are still limited.

A review of the literature indicates that in the majority of studies concerning the environmental assessment of tunnels, construction materials—particularly concrete and reinforcing steel—remain the primary sources of environmental impacts. In most analyses focused on the carbon footprint, these materials account for the dominant share of the total environmental impact. The literature review also shows that despite the growing interest in life cycle assessment of engineering structures, there is still a lack of consistent and comprehensive studies addressing the full spectrum of environmental impact categories in the context of tunnel construction. Furthermore, only a limited number of publications provide comparisons of different tunneling technologies—particularly the TBM and ADECO–RS methods—within a unified LCA methodological framework. Research on the influence of concrete mix composition on life cycle assessment outcomes in underground construction is also scarce.

In the context of increasingly stringent requirements for sustainable construction, it becomes justified to seek solutions that reduce material-related impacts already at the design stage. The literature identifies various approaches to lowering the environmental footprint of structures and construction materials [38,39,40], including, among others, reducing the quantity of materials used as well as substituting them with materials of lower environmental impact, often originating from recycling [41] (e.g., wind turbine components [42]) or from industrial by-products (e.g., Fluidized Bed Furnace Bottom Ashes [43]). In the case of tunneling projects, additional attention is given to the potential for reusing excavated material from tunnel boring as a component of concrete mixes or as backfilling and bedding material [44].

The identified research gap concerns the lack of comprehensive analyses of material optimization in tunneling, encompassing not only GWP–total but also other environmental impact categories. Addressing this gap would enable a more complete assessment of material-related impacts and support the identification of solutions with the greatest potential for their reduction.

In this article, a quantitative analysis of the influence of selected material and structural parameters on LCA results is conducted. The aim of the study is to evaluate the potential for reducing the environmental impact associated with the use of reinforcing steel and concrete in the final lining of a tunnel by limiting their quantities or substituting selected components of the concrete mix with materials of lower environmental impact. In addition to assessing material efficiency, the study provides insights into how the choice of design solutions and materials in selected tunneling technologies (TBM and ADECO–RS) can contribute to achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal and sustainable infrastructure policy.

Unlike most existing tunnel LCA studies, which focus primarily on excavation processes or single indicators such as GWP, the present study explicitly integrates structural design decisions (concrete class, lining thickness, reinforcement demand) with detailed concrete mix optimization within a harmonized LCA framework. This design-oriented perspective enables the quantification of trade-offs between material efficiency and unit environmental impacts, which remains insufficiently addressed in the current literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Models and Scope of Analysis

The analysis was carried out for a representative tunnel characterized by variable geological conditions along its alignment. It should be emphasized that the geometry and thickness of the tunnel lining are strongly dependent on the quality and type of the rock mass—under conditions of low-strength rocks or highly fractured formations, the structural parameters of the lining may undergo significant modifications [8,13]. Based on field and laboratory investigations, as well as an analysis of geotechnical borehole logs, the tunnel alignment was divided into sections with differing rock mass properties. The total length of the analyzed structure was approximately 1919 m, and along its route, several segments with distinct lithological and geomechanical characteristics were identified (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline the Rock Mass Rating (RMR) and the Geological Strength Index (GSI) Classification Values in the Individual Lining Sections. Own elaboration.

The geological profile of the analyzed tunnel consisted primarily of sandstones as well as mudstones and clay shales, characterized by varying degrees of weathering and fracturing. Based on the results of field and laboratory investigations, the tunnel alignment was classified as geologically complex, which was reflected in lithological variability and local reductions in strength parameters.

The RMR classification values ranged from 35 to 63, corresponding to rock mass classes II–V according to Bieniawski, while the GSI values were within the range of 30–57.

Along the tunnel route, six geotechnical sections (1A, 1B, 2, NP, 3, SP) were distinguished and considered homogeneous for the purposes of further design analysis. The variability of lithological and geomechanical parameters along the alignment constituted the basis for defining the types of structural cross-sections and selecting the appropriate lining variants (Table 3).

Table 3.

Geomechanical parameters used to determine the load acting on the tunnel lining. Own elaboration.

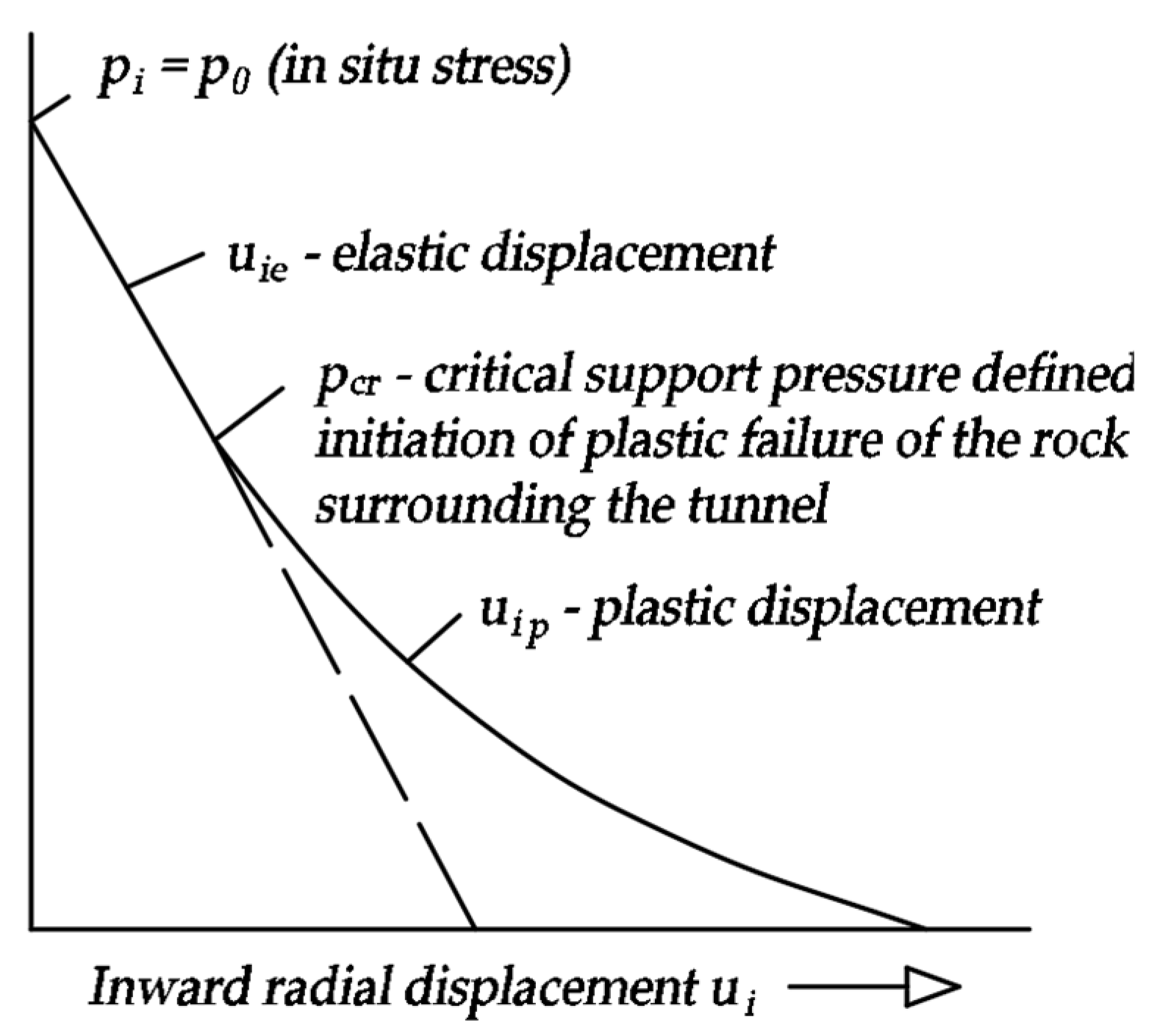

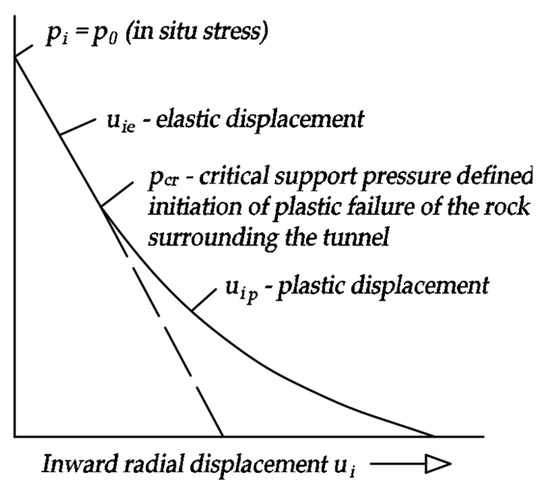

The load acting on the tunnel lining was determined using the ground reaction curve method with the Hoek–Brown failure criterion, which is commonly applied to tunnels excavated in rock masses with varying degrees of fracturing. It is assumed that the rock mass response is elastic–plastic–brittle, accompanied by an increase in volume due to plastic deformation. The stress–strain response is considered elastic until the peak strength is reached, after which an immediate drop to the residual strength is observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ground reaction curve illustrating the relationship between support pressure and tunnel convergence. Own elaboration.

In the ADECO–RS method, the load acting on the final lining is reduced through controlled deformation of the rock mass, which is directly described using the ground reaction curve concept. Allowing a certain degree of tunnel convergence prior to the installation of the final lining results in part of the initial stresses being absorbed and dissipated within the rock mass. Consequently, the pressure transferred to the final lining is lower, and the lining primarily serves a stabilizing and sealing function rather than acting as an element resisting the full geostatic load. In contrast, in the TBM method, the segmental lining is installed immediately after excavation, effectively limiting the development of rock mass deformations. As a result, a significantly larger portion of the ground pressure is directly transferred to the lining, leading predominantly to higher compressive forces in the structural elements. This fundamental difference in the lining–rock mass interaction explains the observed higher axial forces in TBM linings, despite simultaneously lower bending moments compared to the solutions applied in the ADECO–RS method.

It should be emphasized that, in order to assess the stability conditions for a given type of tunnel lining and to determine the load using the ground reaction curve method, it was necessary to refer to mechanical properties at the rock mass scale, which, depending on the conditions, may differ significantly from the properties of intact rock determined at the laboratory scale (Table 3).

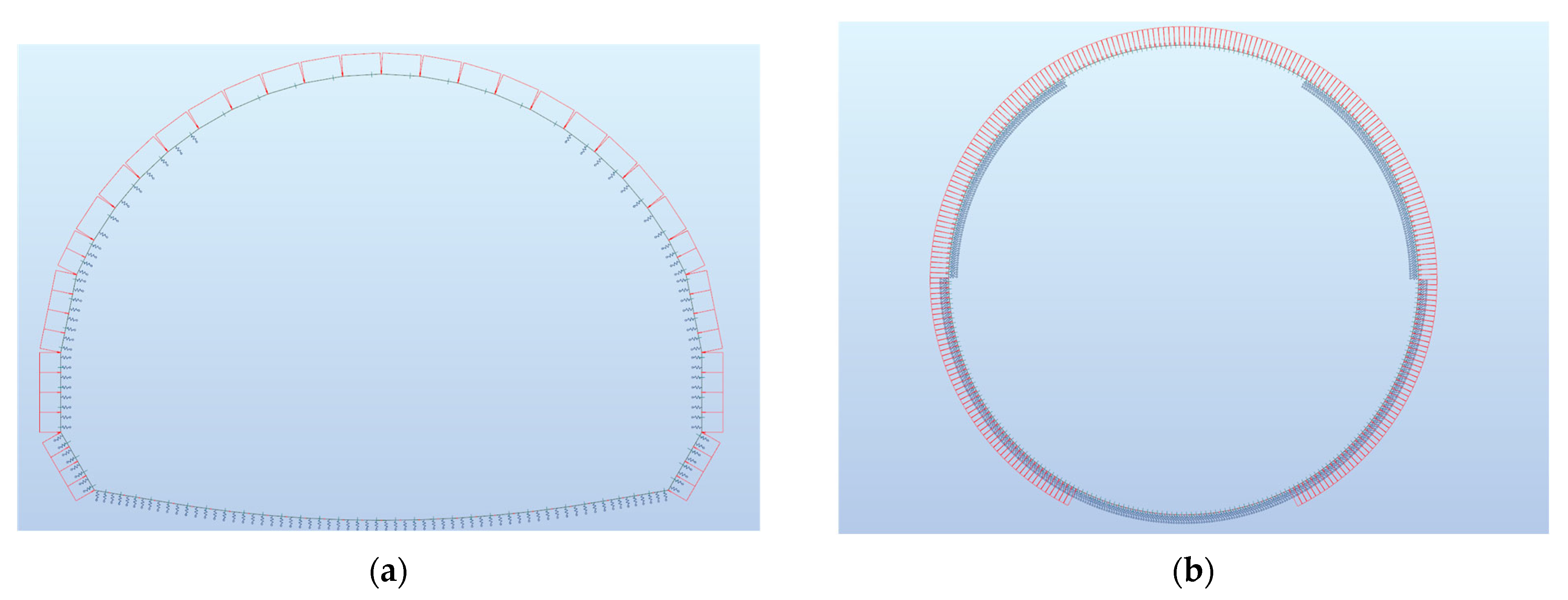

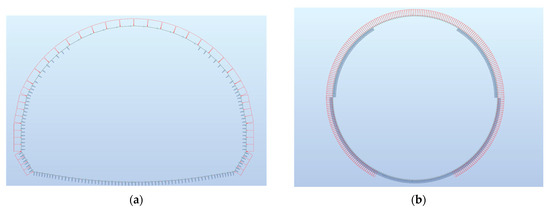

Figure 4a presents the adopted loading scheme of the final lining in the ADECO–RS method. The ground load is non-uniform and reflects the reduced pressure acting on the lining as a result of allowing controlled tunnel convergence prior to the installation of the final lining. The applied load distribution accounts for partial stress redistribution within the rock mass, in accordance with the ground reaction curve concept, leading to a lower level of loads transferred to the lining structure.

Figure 4.

Loading schemes of the final lining in the methods (a) ADECO–RS methods, (b) TBM methods. Own elaboration.

Figure 4b illustrates the loading scheme of the final lining in the TBM method. In this case, the load is more uniformly distributed along the entire perimeter of the cross-section and corresponds to a situation in which the segmental lining is installed immediately after excavation. Under these conditions, the development of rock mass deformations is significantly limited, resulting in a larger portion of the ground pressure being directly transferred to the lining.

In the performed calculations, both the ground pressure acting on the final lining and the self-weight of the lining were taken into account. The self-weight of the structure was introduced as a permanent load, resulting from the adopted lining geometry and material density, and was considered in all analyzed variants. Due to the absence of groundwater along the analyzed tunnel alignment, hydrostatic water pressure and seepage-induced loads were not considered in the structural calculations. Furthermore, seismic actions were not included, as the tunnel is located in a region of low seismicity. This approach allows for a comprehensive assessment of the lining load state, including both external actions originating from the surrounding rock mass and loads resulting from the structural self-weight. In both the ADECO–RS and TBM models, an elastic rock mass reaction was assumed and modeled using appropriate elastic supports, simulating the interaction between the lining and the surrounding ground. This approach enables a realistic representation of the lining–rock mass interaction and the influence of ground deformability on the distribution of internal forces within the structure.

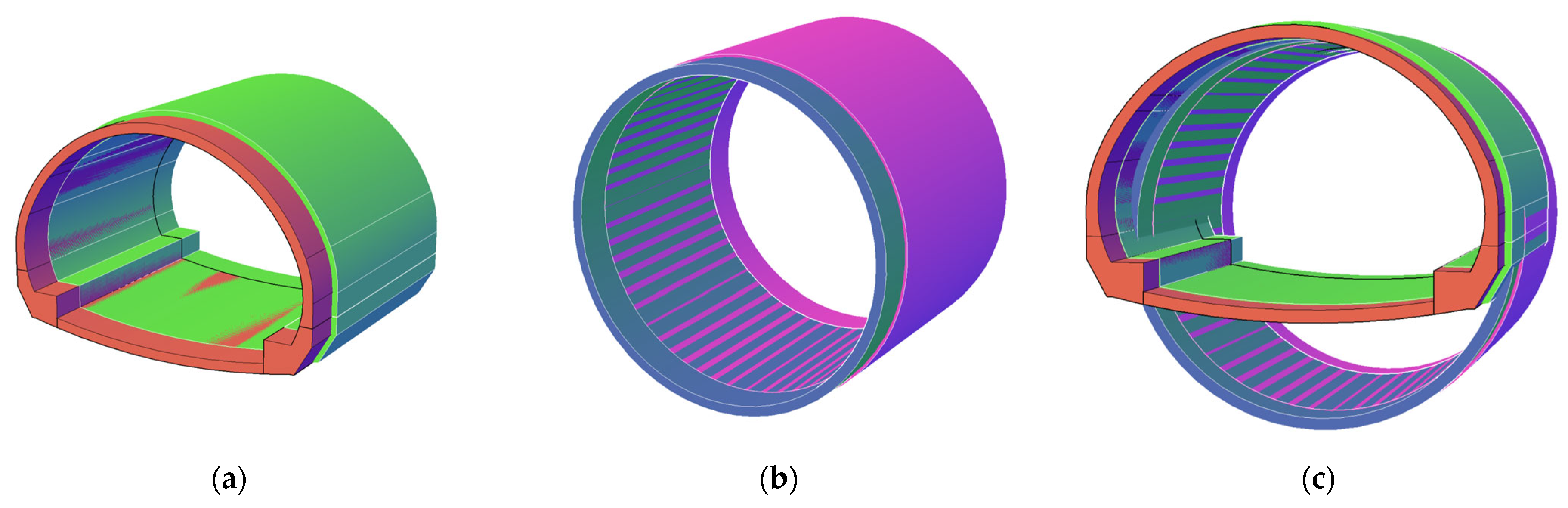

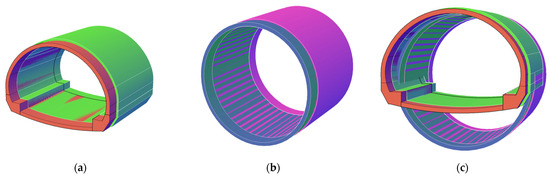

Subsequently, two tunnel construction variants—the TBM method and the ADECO–RS method—were compared (Figure 5). For each technology, an appropriate set of computational models was developed to enable the analysis of the influence of lining geometry, concrete class, and thickness of structural elements on tunnel performance under varying geological conditions. Figure 5c does not represent an additional design solution but rather a conceptual reference model illustrating the target state of structural–material optimization. It highlights the potential overlap between the ADECO–RS and TBM solutions when geometry, concrete class, and lining thickness are selected in a coordinated manner to achieve comparable structural performance under different excavation philosophies.

Figure 5.

Comparison of tunnel lining geometries: (a) ADECO–RS tunnel, (b) TBM tunnel, and (c) superimposed view of both variants. Own elaboration.

For the TBM method, the analysis focused on the selection of concrete class and segmental lining thickness in relation to the geological conditions of each section. The design variants are presented in Table 4, including, among others, a comparison of concrete volume and reinforcement mass for combinations of concrete classes C30/37–C80/95 and lining thicknesses ranging from 50 to 60 cm.

Table 4.

Variants analyzed for the TBM tunneling method. Own elaboration.

Analogously, for the ADECO–RS method, three variants of the monolithic final lining were analyzed, differing in concrete class (C30/37–C80/95) and in the thickness of the crown and invert (from 50 to 75 cm) (Table 5). These variants were developed with consideration of the specific deformation behavior of the rock mass and the face reinforcement principles characteristic of the ADECO–RS approach.

Table 5.

Variants analyzed for the ADECO–RS tunneling method. Own elaboration.

The structural and strength calculations were performed under the assumption of a constant tunnel geometry and continuous structural cross-sections within each section. The determination of material demand for the individual structural–material variants was also carried out assuming a comparable level of compressive stresses in the concrete and tensile stresses in the reinforcing steel. This approach ensured comparable structural performance conditions in each analyzed variant and enabled the assessment of the influence of concrete class and lining thickness solely in terms of material efficiency, without altering the global stress state in the tunnel lining.

The design of the individual structural elements was carried out in Autodesk Robot Structural Analysis 2023, in accordance with the applicable standards and construction regulations. The computational model included permanent loads associated with the self-weight of the structure as well as loads induced by the surrounding rock mass.

The calculations performed for all load cases made it possible to determine the maximum (positive and negative) values of internal forces in the respective elements. The design of the reinforced concrete sections of the tunnel linings was conducted in accordance with the requirements of Eurocode 2 (PN-EN 1992-1-1) [45]. The computations included an analysis of the interaction between axial forces and bending moments. Based on this analysis, the diameters and number of reinforcing bars were selected to ensure adequate load-bearing capacity and operational safety.

2.2. Optimization of Concrete Mix Designs

In the subsequent stage of the study, the influence of concrete mix composition on the potential to reduce environmental impacts was analyzed. For each concrete class, two variants were considered:

- variant a: mix with Portland cement (CEM I),

- variant b: mix with cement containing secondary (waste-derived) components (CEM II and CEM III).

In variant b with multi-component cement, additional modifications were introduced, including a reduction in cement content, the use of fly ash, and—for classes lower than C80/95—the incorporation of recycled aggregates. The applied recycled aggregate corresponded to Type A, defined as an aggregate consisting of at least 90% crushed concrete. According to PN-EN 206+A2:2021-08 [46], the maximum substitution rate of natural aggregate with recycled aggregate is 50%. For concrete class C80/95, recycled aggregates were not included due to the limited feasibility of achieving high strength parameters when they are used [47,48]. The compositions of the concrete mixes are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Analyzed concrete mix compositions. Own elaboration.

All analyzed concrete mixes met the requirements for resistance to the anticipated environmental conditions, including the expected aggressiveness of the soil–water environment, which allows their use in tunnel structures in accordance with the applicable standards and design guidelines.

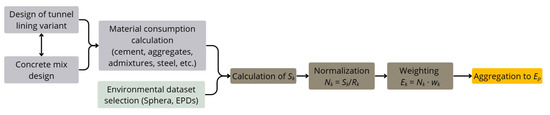

2.3. LCA Methodology—Scope and Data Sources

For engineering structures, the key methodological frameworks for life cycle environmental assessment are defined in the standards EN 15804+A2 [49] and EN 17472:2022 [50]. The assessment was carried out using the core and additional impact categories in accordance with these standards (Table 6).

The analysis was performed using the EF 3.1 (Environmental Footprint) method developed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission, which defines the normalization values [51] and weighting factors [52] for the respective impact categories (Table 7), enabling their comparison in the context of overall environmental impact (according to Equation (1)).

where

k—categories of impact;

Nk—standardized result;

wk—weighting factor assigned to impact category k;

Sk—the characteristic value of environmental impact;

Rk—reference value.

The scope of the analysis covered stages A1–A3, corresponding to the „ cradle-to-gate”, and was limited exclusively to the materials used in the tunnel lining, i.e., the components of the concrete mix and reinforcing steel. The environmental impact assessment of the individual components was carried out based on data obtained primarily from the Sphera database [53], for chemical admixtures and fly ash, data from available Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) were used. The Sphera dataset represented values characteristic of the European region and the last 5 years. For reinforcing steel, the dataset assumed production using the electric arc furnace (EAF) method with 100% steel scrap, which is common for reinforcing bars [54]. For recycled aggregate, “the polluter pays principle” was applied, in accordance with EN 15804+A2, whereby environmental burdens are attributed to the process generating the waste rather than to the process of its reuse.

Based on the material consumption results for each structural variant, the environmental impact values for each impact category were determined. These values constituted Sk and were subsequently used in the normalization and weighting process in accordance with Equation (1).

This approach yields a single aggregated environmental impact indicator value Ep, representing a dimensionless measure of the total impact of the analyzed variant (in this study—the tunnel lining over its entire analyzed length). This value constitutes the main outcome of the assessment, allowing for comparison among all variants.

Table 7.

Normalization and weighting factors for environmental impact categories. Own elaboration based on [49,51,52].

Table 7.

Normalization and weighting factors for environmental impact categories. Own elaboration based on [49,51,52].

| Impact Category (Indicator) | Normalization Factors Rk | Unit | Weighting Factors wk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change—total (GWP–total) | 7.55 × 103 | kg CO2 eq./person | 2.11 × 10−1 |

| Ozone depletion (ODP) | 5.23 × 10−2 | kg CFC–11 eq./person | 6.31 × 10−2 |

| Acidification (AP) | 5.56 × 101 | mol H+ eq./person | 6.20 × 10−2 |

| Eutrophication aquatic freshwater (EP–freshwater) | 1.61 × 100 | kg P eq./person | 2.80 × 10−2 |

| Eutrophication aquatic marine (EP–marine) | 1.95 × 101 | kg N eq./person | 2.96 × 10−2 |

| Eutrophication terrestrial (EP–terrestrial) | 1.77 × 102 | mol N eq./person | 3.71 × 10−2 |

| Photochemical ozone formation (POCP) | 4.09 × 101 | kg NMVOC eq./person | 4.78 × 10−2 |

| Depletion of abiotic resources—minerals and metals (ADP–minerals & metals) | 6.36 × 10−2 | kg Sb eq./person | 7.55 × 10−2 |

| Depletion of abiotic resources—fossil fuels (ADP–fossil) | 6.50 × 104 | MJ/person | 8.32 × 10−2 |

| Water use (WDP) | 1.15 × 104 | m3 water eq of deprived water/person | 8.51 × 10−2 |

| Particulate matter emissions (PM) | 5.95 × 10−4 | disease incidences/person | 8.96 × 10−2 |

| Ionizing radiation, human health (IRP) | 4.22 × 103 | kBq U–235 eq./person | 5.01 × 10−2 |

| Eco–toxicity (freshwater) (ETP–fw) | 5.67 × 104 | CTUe/person | 1.92 × 10−2 |

| Human toxicity, cancer effects (HTP–c) | 1.73 × 10−5 | CTUh/person | 2.13 × 10−2 |

| Human toxicity, non–cancer effects (HTP–nc) | 1.29 × 10−4 | CTUh/person | 1.84 × 10−2 |

| Land use-related impacts/soil quality (SQP) | 8.19 × 105 | dimensionless/person | 7.94 × 10−2 |

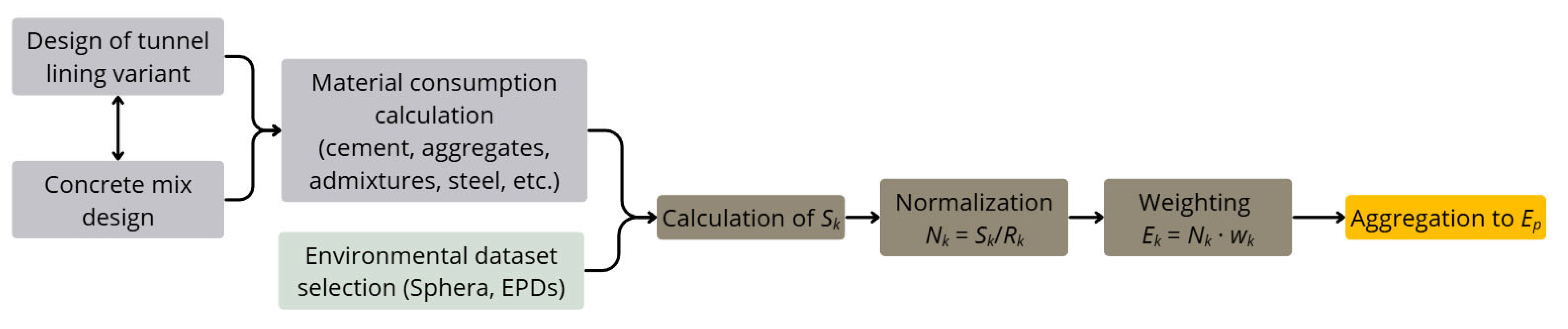

The assessment procedure for evaluating environmental impacts is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flowchart illustrating the step-by-step procedure used to obtain the aggregated environmental performance indicator Ep. Own elaboration.

3. Results and Discussion

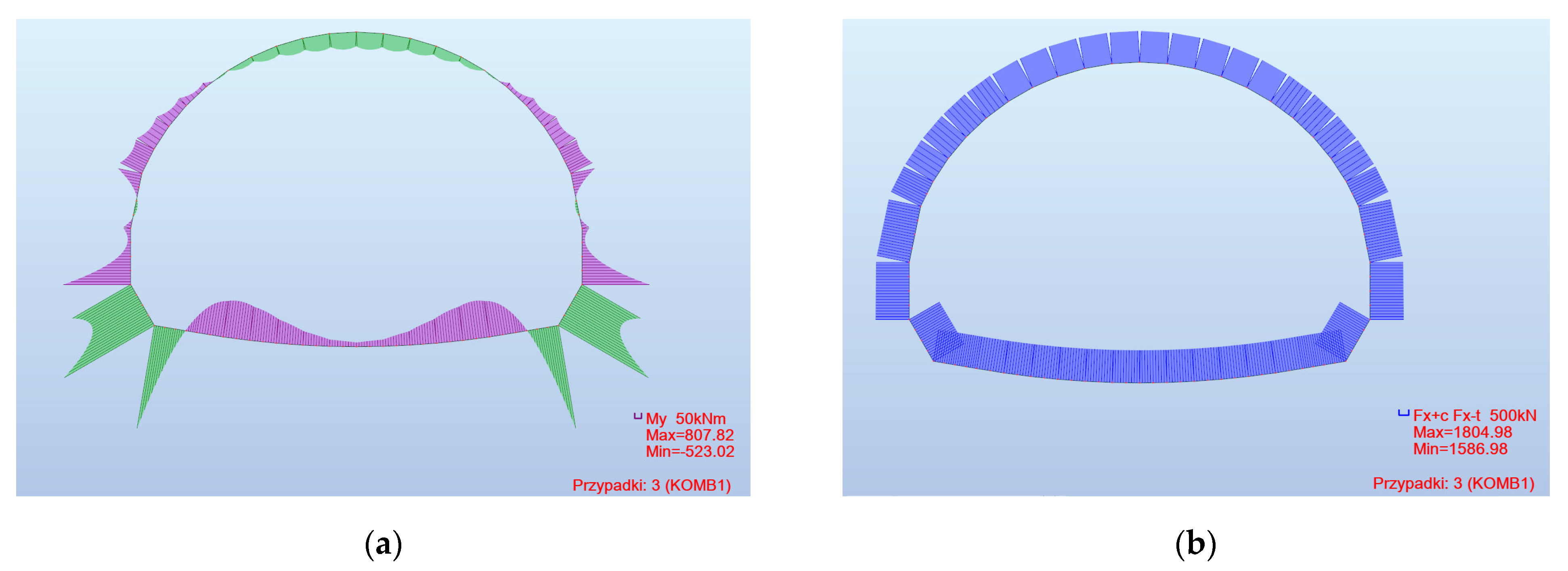

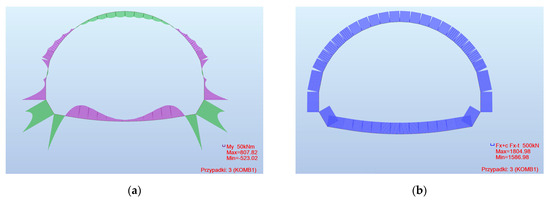

Figure 7 presents the distribution of internal forces in the tunnel lining constructed using the ADECO–RS and TBM technologies for a selected example segment of Section 2. A summary of the maximum bending moments and axial forces in the final lining for the ADECO–RS and TBM methods is provided in Table 8.

Figure 7.

Distribution of internal forces in tunnel linings for ADECO–RS and TBM technologies in a representative section: (a) bending moments in the ADECO–RS lining, (b) axial forces in the ADECO–RS lining, (c) bending moments in the TBM lining, and (d) axial forces in the TBM lining. Own elaboration.

Table 8.

Summary of maximum bending moments and axial forces in the final lining for the ADECO–RS and TBM methods. Own elaboration.

For each method, the bending moment and axial force diagrams were determined, enabling a comparison of the structural behavior under varying geotechnical conditions. In the case of the ADECO–RS technology, a greater variability of bending moments is observed in the crown and invert regions, reflecting the influence of non-uniform rock mass deformations and local stiffness variations in the temporary support. For the TBM technology, the distribution of forces exhibits a more symmetrical pattern, with axial forces dominating in the precast lining rings, which results from the geometric regularity of the cross-section and the uniform transfer of loads onto the segmental lining.

The higher axial compressive forces observed in the TBM variant (Figure 7d) are an inherent characteristic of segmental linings and result from the predominantly uniform load transfer and the high geometric regularity of the circular cross-section. From a structural perspective, such compressive force levels do not pose a limitation, as concrete exhibits very favorable performance under compression. At the same time, the TBM lining is characterized by significantly lower bending moments compared to the ADECO–RS solution (Figure 7c vs. Figure 7a), which reduces the demand for tensile reinforcement associated with flexural behavior. In contrast, the ADECO–RS method, due to its greater structural deformability and the non-uniform interaction with the surrounding rock mass, leads to higher bending moments in the lining. As concrete has limited tensile capacity, this bending-dominated response necessitates a substantially higher amount of reinforcement to ensure structural safety. Consequently, although the TBM lining is subjected to higher compressive forces, its favorable stress state in terms of bending explains the lower reinforcement demand observed in the segmental lining variants.

To compare the material efficiency of the two methods, a quantitative analysis was carried out for the concrete and reinforcing steel requirements across the different lining variants. The calculations were performed for the entire tunnel, with a total length of 1919.44 m, divided into sections characterized by varying geotechnical conditions (Table 9 and Table 10).

Table 9.

Variants analyzed for the ADECO–RS tunneling method. Own elaboration.

Table 10.

Variants analyzed for the TBM tunneling method. Own elaboration.

The results of the structural calculations performed for the various tunnel lining variants made it possible to assess the influence of geometry, concrete class, and construction technology on the structural behavior under different geological conditions. The analysis of bending moment and axial force distributions showed that the tunnel lining is subject to significant variations in stress levels depending on the quality of the rock mass and the adopted material parameters. The most highly loaded zones—regardless of the technology used—were the crown and the lateral parts of the lining, which is consistent with the typical behavior of circular and oval cross-sections. In the invert zone, compressive forces predominated, confirming the correct pattern of load transfer to the ground.

The summary of maximum bending moments and axial forces clearly confirms the different structural behavior mechanisms of the final lining in the ADECO–RS and TBM methods. In the ADECO–RS solutions, the axial force values are relatively low and similar across all analyzed variants, reaching approximately 1.8 MN in Sections 1–2 and about 4.5 MN in Sections 3, NP, and SP. At the same time, very high bending moments are observed, ranging from approximately 800–860 kNm in Sections 1–2 to about 1490–1540 kNm in sections characterized by less favorable geotechnical conditions. This indicates that, in the ADECO–RS method, the lining predominantly works in a bending-dominated state, which is a consequence of the higher deformability of the system and the non-uniform distribution of rock mass actions.

Increasing the concrete strength class in the ADECO–RS variants does not lead to a significant reduction in bending moments or axial forces, confirming that the level of internal forces is governed primarily by the lining–rock mass interaction scheme and the load distribution, rather than by the material strength itself. As a result of bending-dominated behavior, substantial amounts of reinforcement are required, since concrete—despite its favorable compressive strength—exhibits limited capacity to resist tensile stresses.

A different structural behavior is observed in the TBM variants. In this case, the maximum axial forces are several times higher than those obtained for the ADECO–RS method, reaching values of approximately 5.1–5.3 MN in Sections 1–2 and 12.7–12.9 MN in Sections 3, NP, and SP. At the same time, the bending moments are significantly lower, amounting to approximately 140–190 kNm in Sections 1–2 and 560–700 kNm in sections characterized by less favorable geotechnical conditions. This indicates that the TBM segmental lining predominantly works in a compression-dominated state, which is particularly advantageous from the perspective of the mechanical properties of concrete.

Reducing the thickness of the segmental lining in the TBM W2 variant, combined with the use of a higher concrete strength class, leads to a further reduction in bending moments with only a slight decrease in axial forces. This confirms that, in the case of TBM, increasing the concrete strength class can effectively compensate for the reduction in element thickness without an unfavorable increase in bending-related demands. Consequently, the reinforcement demand in the TBM variants is significantly lower than in the ADECO–RS solutions, despite the occurrence of higher axial forces.

The obtained results indicate that the key factor determining the level of internal forces in the final lining is not the magnitude of the ground pressure itself, but rather the manner in which it is transferred and the degree of rock mass deformation allowed prior to lining installation. These differences have a direct impact on material demand and, consequently, on the subsequent results of the environmental analyses.

The comparison of results for both methods revealed clear differences in load-transfer mechanisms and material utilization. Linings constructed using the ADECO–RS method exhibit greater structural deformability, which promotes a more uniform stress distribution, whereas TBM segmental linings—despite their higher stiffness—are more sensitive to changes in thickness. The analysis nevertheless showed that all variants satisfy the load-bearing and serviceability criteria, with the differences between them relating primarily to material efficiency and the potential for reducing environmental impacts.

With regard to the material efficiency analysis for the TBM method, two design variants were adopted, differing in concrete class and segmental lining thickness:

- Variant TBM–W1: lining with a thickness of 60 cm, made of concrete class C30/37 in sections 1–2 and C50/60 in sections 3, NP, and SP. For this variant, the total concrete volume amounted to 59,126 m3, while the reinforcement mass reached 3,432,120 kg.

- Variant TBM–W2: lining with a thickness of 50 cm, made of concrete class C50/60 (sections 1–2) and C80/95 (sections 3, NP, SP). In this case, the concrete volume was 48,970 m3 and the reinforcement mass was 2,511,404 kg.

In a similar manner, three variants were analyzed for the ADECO–RS method, differing in concrete class and in the thickness of the structural elements (crown and invert):

- Variant ADECO–RS W1: crown thickness 50–75 cm, invert thickness 50–60 cm, concrete class C30/37. The total concrete volume amounted to 54,381 m3, and the reinforcement mass reached 2,501,226 kg.

- Variant ADECO–RS W2: crown and invert thickness 50 cm, concrete class C50/60. The total concrete volume decreased to 51,417 m3, and the reinforcement mass was 2,085,591 kg.

- Variant ADECO–RS W3: crown and invert thickness 50 cm, concrete class C80/95. A concrete volume of 51,417 m3 was obtained, along with a reinforcement mass of 1,738,915 kg, indicating a reduction in steel demand compared with variant W1.

The analysis of material efficiency for both technologies revealed clear differences in the demand for concrete and steel, resulting from both the geometric parameters of the lining and the adopted concrete classes. In the TBM method, reducing the segment thickness from 60 cm to 50 cm, combined with the use of higher concrete classes, yielded significant material benefits. The concrete volume decreased by 17.17%, while the reinforcement mass was reduced by as much as 26.82%. This indicates that increasing the concrete class in TBM segmental linings can be an effective strategy for compensating for a reduction in element thickness without compromising structural safety. At the same time, variant W2 demonstrates greater environmental and economic potential, making it a more efficient option in the context of sustainable design.

In the case of the ADECO–RS method, a similar trend is observed, although the extent of material reduction is smaller than in the TBM technology. Increasing the concrete class from C30/37 to C50/60 while maintaining a constant lining thickness reduced the concrete volume by 5.45% and decreased the reinforcement mass by 16.63%. Transitioning to concrete class C80/95, with identical geometric parameters of the lining, resulted in a further reduction in the reinforcement mass to 1,738,915 kg, representing a 30.47% decrease compared with variant W1. The analysis indicates that in the ADECO–RS technology, the greatest material savings stem from optimizing the concrete class, while the influence of geometric modifications is less significant than in TBM segmental linings.

When comparing the two technologies, it becomes evident that TBM segmental linings are more sensitive to changes in thickness, yet they exhibit a greater potential for reducing material consumption. In the ADECO–RS technology, the use of higher concrete classes results in a substantial reduction in reinforcement demand, which is particularly important from the perspective of carbon footprint reduction. Consequently, both approaches offer opportunities for significant material optimization, although the mechanisms behind these benefits differ depending on the technology. These findings highlight the necessity of an individualized approach to the selection of lining parameters, taking into account both the geotechnical conditions and the objectives related to sustainable development.

Combining the structural and material variants made it possible to develop a set of options analyzed in the further part of the study—six for the ADECO–RS method and eight for the TBM method (Table 11).

Table 11.

Summary of analyzed variants for ADECO–RS and TBM technologies. Own elaboration.

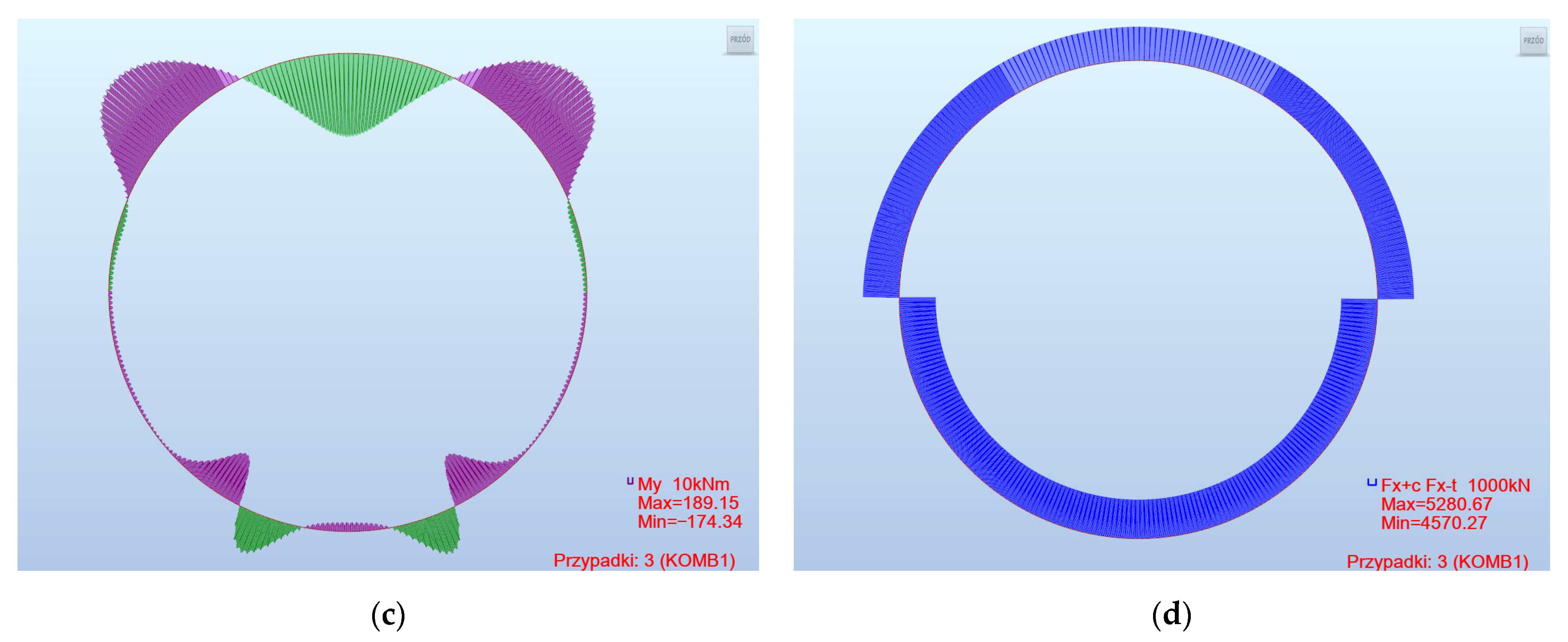

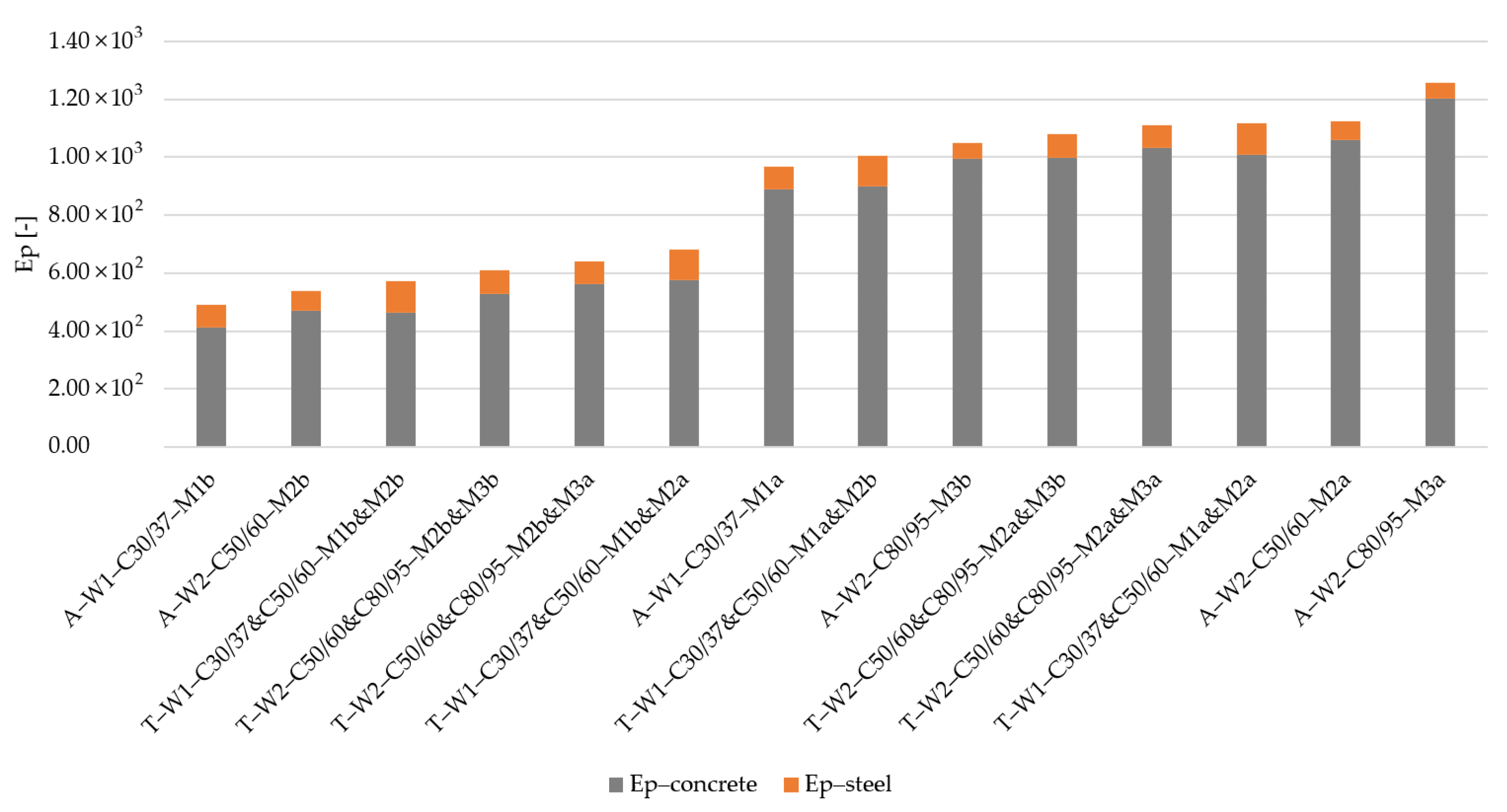

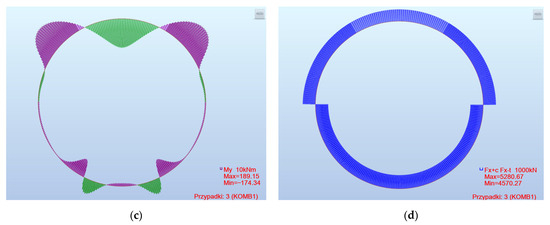

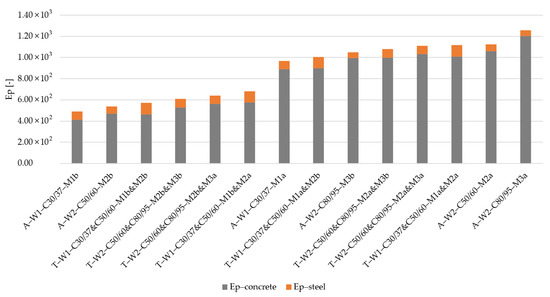

Figure 8 presents the aggregated environmental indicator (Ep) for all analyzed variants, derived from the quantities of concrete and reinforcing steel determined in the structural calculations. The contributions of concrete and steel are shown separately, allowing their relative influence on the overall result to be assessed.

Figure 8.

Environmental performance (Ep) of the analyzed structural–material variants, shown with separate contributions from concrete (grey) and reinforcing steel (orange). Own elaboration.

The analysis of the contribution of lining materials to the total environmental impact indicator Ep shows that reinforcing steel accounts for between 4% and 19% of the overall impact. The remaining share is attributed to concrete, which is the dominant contributor in all cases. Despite differences in structural assumptions, the minimum and maximum Ep values exhibit comparable results for both technologies (ADECO–RS and TBM), indicating that similar levels of environmental performance can be achieved with an appropriate selection of concrete class and concrete mix composition. However, it should be noted that for tunnels, technical conditions play a decisive role in determining the construction method. Nonetheless, the conducted analysis demonstrates a significant potential for reducing environmental impacts within a single technological approach—the difference between the variants with the highest and lowest Ep values amounts to 61% for the ADECO–RS technology and 49% for the TBM technology.

In the case of the ADECO–RS technology, the Ep value increases with the concrete class. The use of higher-strength concrete was intended to reduce the amount of materials (concrete and reinforcing steel), which could potentially offset the higher unit impact associated with producing such concrete. The literature indicates that, per cubic meter of concrete, environmental impact increases with concrete strength class [55,56]. However, study [57] shows that when analyzing an entire structure, the conclusions may differ: increasing the concrete class can reduce the overall impact if it enables a significant reduction in material quantities within the structure. In the analyzed variants (e.g., A-W1–C30/37–M1a compared with A–W2–C80/95–M3a), this effect proved insufficient (a reduction of only about 5.45% in concrete volume)—the increase in concrete class led to an increase in total environmental impact. A comparison of variants within the same concrete class shows that optimizing the mix composition (e.g., A–W1–C30/37–M1a relative to A–W1–C30/37–M1b) enables a lower Ep value to be achieved (by 17% to 51%). Similar trends were observed in publication [26], in which—although only the carbon footprint was assessed—a reduction of up to approximately 70% was demonstrated as a result of modifying the concrete mix composition.

In the case of the TBM technology, the use of higher-strength concrete resulted in a reduction in the total environmental impact (Ep). Unlike in the ADECO–RS method, increasing the concrete class in this case was associated with a substantial decrease in the quantities of construction materials—both the concrete volume (17.17%) and the reinforcement mass (26.82%)—which translated into a lower Ep value. The variants with higher concrete classes T–W2–C50/60&C80/95–M2b&M3b and T–W2–C50/60&C80/95–M2b&M3a, achieved values of Ep that were comparable to (as in T–W1–C30/37&C50/60–M1b&M2b) or lower than those of the variants with lower concrete classes (e.g., T–W1–C30/37&C50/60–M1b&M2a).

Similarly to the ADECO–RS technology, the (b) variants exhibited lower environmental impacts compared with the corresponding Portland-cement variants (a), e.g., (T–W1–C30/37&C50/60–M1a&M2a and T–W1–C30/37&C50/60–M1b&M2b).

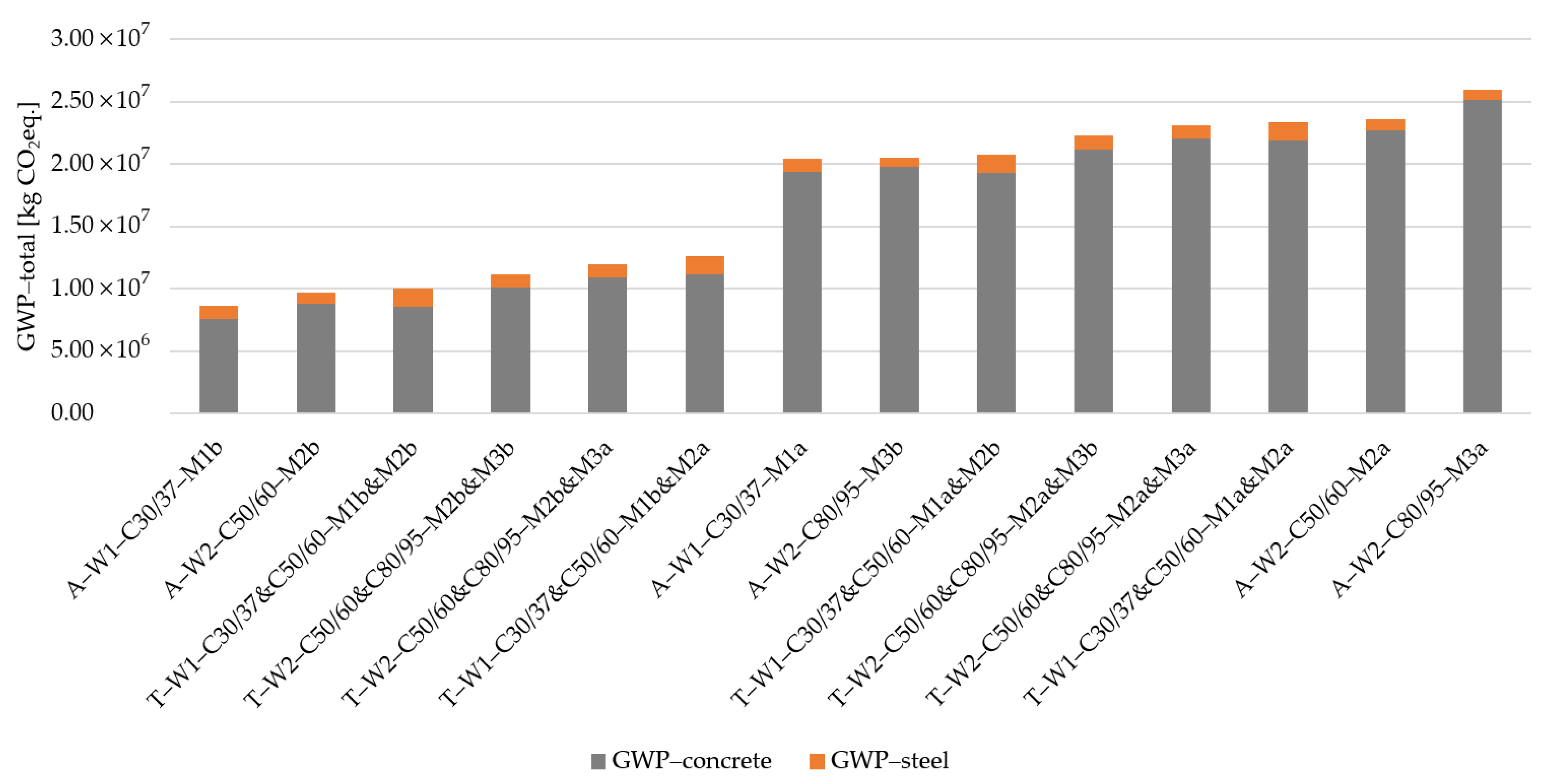

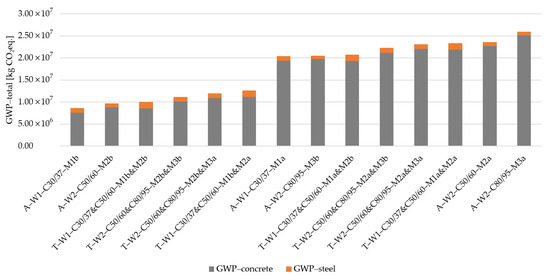

Given the continued importance of the carbon footprint in environmental policy and current regulations, the results are also presented (Figure 9) with respect to this indicator alone. The ordering of the variants for the GWP–total indicator is similar to that obtained for the Ep indicator; however, it is not entirely identical. The differences concern mainly the variants with intermediate values, while the variants with the lowest and highest environmental impacts retain the same position in both analyses. A similar relationship is reported in study [58], which shows that a ranking of concrete mixes based solely on carbon footprint does not always fully reflect the ranking obtained for the remaining environmental impact categories.

Figure 9.

GWP–total of analyzed tunnel lining variants. Own elaboration.

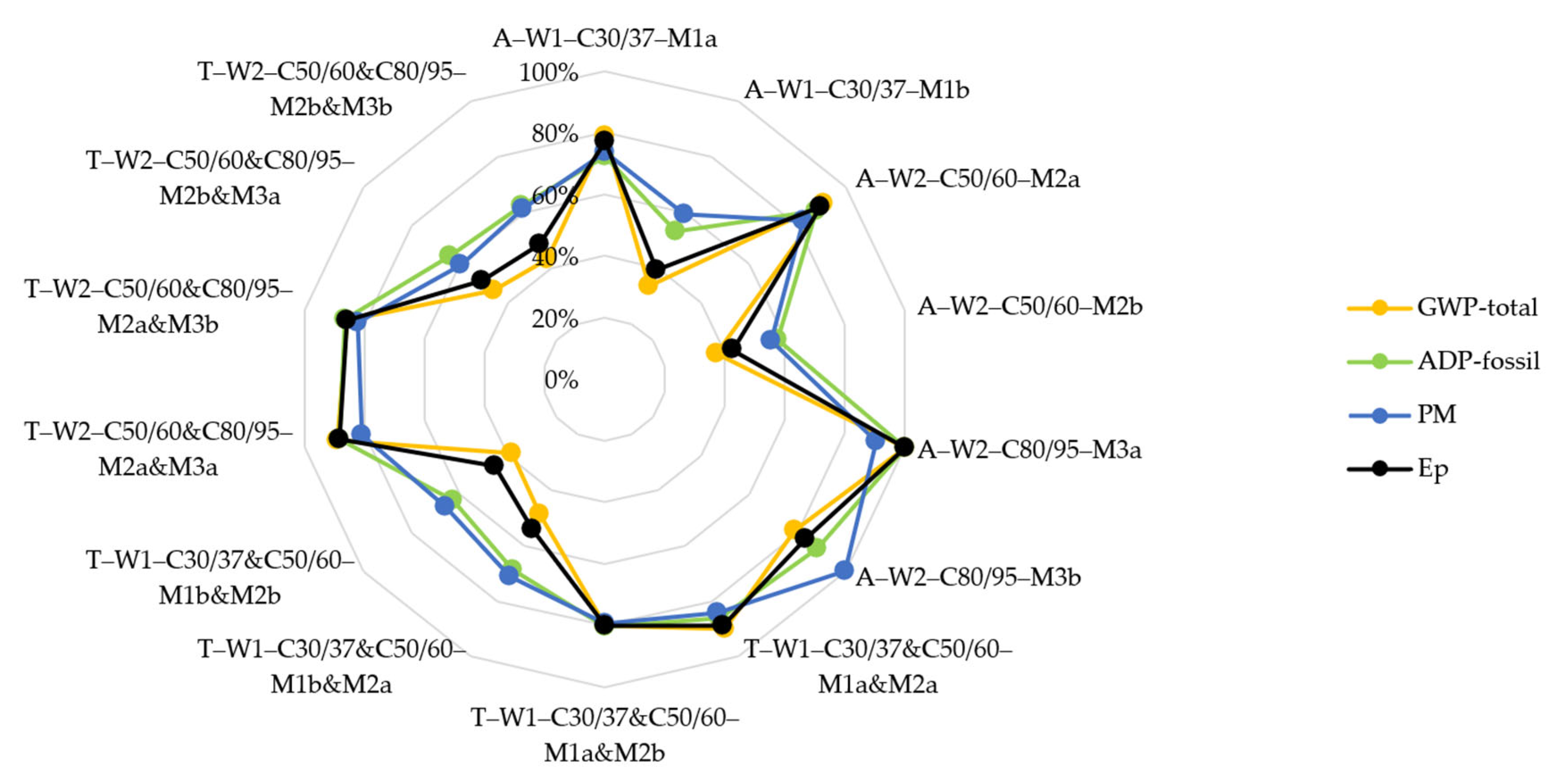

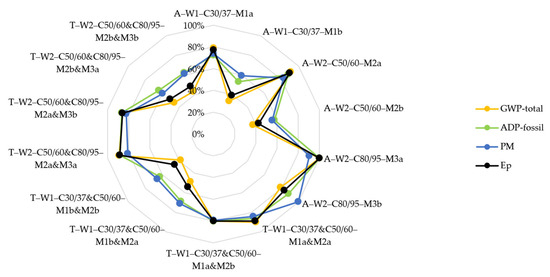

To more accurately assess the degree of consistency between the environmental categories, a comparison was performed for the three indicators with the largest contribution to the Ep value (a combined 79–80%): GWP–total, ADP–fossil, and PM. The values for each indicator were normalized within the range of 0–100% relative to the maximum value in the given category and presented in a radar chart (Figure 10), which made it possible to determine the relationships between the variant rankings. The results confirm that, despite the general consistency of trends, the individual impact categories do not exhibit full agreement, particularly in the case of ADP–fossil and PM. This highlights the need for multi-dimensional environmental assessments that include more than one impact category. Similar conclusions were also reported in the literature, e.g., in ref. [59], where it was emphasized that analyses should include not only GWP–total but also ADP–fossil.

Figure 10.

Comparison of environmental impact indicators (GWP–total, ADP–fossil, PM, Ep) for the analyzed variants of ADECO–RS and TBM technologies. Source: Own elaboration.

4. Conclusions

This study applied a harmonized Life Cycle Assessment framework in accordance with EN 15804+A2 and EN 17472:2022 to evaluate the environmental performance of tunnel linings designed using the TBM and ADECO–RS tunneling methods. The analysis directly linked the structural behavior of the tunnel lining with material demand and concrete mix composition, thereby addressing a research gap in existing tunnel LCA studies, which typically focus on individual environmental indicators and on the assessment of a single specific design solution, without considering the potential for optimization.

The results confirm that the environmental performance of tunnel linings is governed primarily by the interaction between structural working mechanisms and material parameters rather than by the choice of tunneling technology alone. TBM segmental linings are characterized by a predominantly compression-dominated stress state, with high axial forces and relatively low bending moments, whereas ADECO–RS linings exhibit bending-dominated behaviour associated with controlled deformation of the surrounding rock mass prior to final lining installation. These fundamentally different structural responses directly affect lining thickness, reinforcement demand, and the feasibility of using higher concrete strength classes, which in turn determine material consumption and environmental impact.

Across all analyzed variants, concrete was identified as the dominant contributor to environmental impact, accounting for approximately 81–96% of the aggregated environmental performance indicator (Ep), while reinforcing steel contributed between 4% and 19%. This finding indicates that strategies aimed at reducing concrete volume or lowering its unit environmental burden are more effective than optimization measures focused exclusively on reinforcement reduction. At the same time, the relative share of steel remains important in bending-dominated systems, such as ADECO–RS linings, where reinforcement demand is structurally driven.

The study demonstrates that the effectiveness of increasing the concrete strength class is strongly dependent on the adopted tunneling concept. In the ADECO–RS method, higher-strength concrete does not lead to a net reduction in environmental impact, as the resulting decrease in material quantities is insufficient to offset the higher unit impact of high-strength concrete. In contrast, for TBM segmental linings, the use of higher-strength concrete enables a meaningful reduction in lining thickness and reinforcement mass, leading to an overall decrease in environmental impact. This highlights the necessity of evaluating concrete strength class in direct relation to achievable geometric and structural optimization rather than treating it as an isolated material parameter.

Independent of the tunneling technology, optimization of concrete mix composition proved to be one of the most effective measures for reducing environmental impact. The application of multi-component cements (CEM II and CEM III), reduced clinker content, and—where applicable—recycled aggregates consistently resulted in lower environmental impacts across all assessed categories. In several variants, concrete mix optimization alone led to reductions in the aggregated environmental indicator of several tens of percent compared with reference mixes based on Portland cement, without compromising structural performance requirements.

A comparison between the aggregated environmental performance indicator (Ep) and individual impact categories, particularly GWP–total, ADP–fossil, and particulate matter emissions, revealed that rankings of design variants are not fully consistent across indicators. While carbon footprint remains a key metric in regulatory and design practice, these discrepancies demonstrate that reliance on a single indicator may obscure relevant trade-offs between material efficiency, resource depletion, and emission-related impacts. The use of a multi-indicator assessment, therefore, provides a more robust basis for environmentally informed design decisions.

From an engineering perspective, the results indicate that environmental optimization of tunnel linings should be integrated into the structural design process at an early stage. This requires explicit coupling of lining geometry, concrete strength class, and concrete mix design, with particular attention to whether higher-strength materials enable a sufficient reduction in material quantities. Regardless of the tunneling method applied, concrete mixes with reduced clinker content and multi-component binders represent a low-risk and effective strategy for improving environmental performance, provided that durability and underground exposure requirements are satisfied.

The scope of the study was limited to the material production stage (A1–A3). Transport, construction, operation, and maintenance phases were not included and may influence the relative importance of individual contributors, particularly under region-specific energy mixes and supply-chain conditions. In addition, geological parameters were treated as deterministic input values; future research should therefore incorporate probabilistic approaches to evaluate the sensitivity of structural response, material demand, and environmental performance to geological uncertainty.

Overall, the study demonstrates that the environmental performance of tunnel linings is not a direct function of tunneling method selection, but rather the outcome of coupled structural and material design decisions. The presented results provide a quantitative basis for material-efficient and environmentally informed tunnel lining design, bridging structural engineering practice with life-cycle-based sustainability assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M.; methodology, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M.; formal analysis, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M.; investigation, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M.; visualization, D.W., J.J.-L. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TBM | Tunnel Boring Machine |

| NATM | New Austrian Tunnelling Method |

| ADECO–RS | Analysis of Controlled Deformation in Rocks and Soils |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| RMR | Rock Mass Rating |

| GSI | Geological Strength Index |

References

- Athanasopoulou, A.; Bezuijen, A.; Bogusz, W.; Bournas, D.; Brandtner, M.; Breunese, A.; Burbaum, U.; Dimova, S.; Frank, R.; Ganz, H.; et al. Standardisation Needs for the Design of Underground Structures; Athanasopoulou, A., Bogusz, W., Bournas, D., Dimova, S., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasopoulou, A.; Bogusz, W.; Boldini, D.; Brandtner, M.; Brierley, R.; Dimova, S.; Franzen, G.; Ganz, H.; Sousa, M.L.; Van Seters, A.; et al. Prospects for Designing Tunnels and Other Underground Structures in the Context of the Eurocodes—Support to Policies and Standards for Sustainable Construction; Athanasopoulou, A., Dimova, S., Franzen, G., Van Seters, A., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ustaoglu, A.O.; Unutmaz, B.; Gokceoglu, C. Seismic Fragility and Risk Assessment of Transportation Tunnels in Marmara and Aegean Regions of Türkiye. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, J.; Group, S.; Limbach, R.; Kerbler, L.; Mannisto, V.; Balazs, H.; Pier, J.; Cartolano, P.; La, S.; Van Der Velde, M.J.; et al. Trans-European Road Network, TEN-T (Roads): 2019 Performance Report; CEDR’s Secretariat-General: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; ISBN 979-10-93321-54-7. Available online: https://www.cedr.eu/news-data/1499/CEDR-publishes-TEN-T-2019-Performance-Report (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Majcherczyk, T.; Pilecki, Z.; Niedbalski, Z.; Pilecka, E.; Blajer, M.; Pszonka, J. The Influence of Geological Engineering and Geotechnical Conditions on Parameter Selection of the Primary Lining of a Road Tunnel in Laliki. Gospod. Surowcami Miner.—Miner. Resour. Manag. 2012, 28, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, S.; Bilim, N.; Deresal, D.G.; Kekeç, B. The Most Commonly Used TBM Types and Their Suitability for Hard and Soft Grounds. Min. Rev. 2025, 31, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyla, M.; Vojtasik, K.; Hrubesova, E.; Stolarik, M.; Nedoma, J.; Pinka, M. Approach for Optimisation of Tunnel Lining Design. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vydrová, L.Č. Comparison Of Tunnelling Methods NATM and ADECO-RS. Civ. Eng. J.-Staveb. Obz. 2015, 24, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, J.L. Cut-and-Cover Tunnel Structures. In Tunnel Engineering Handbook; Bickel, J.O., Kuesel, T.R., King, E.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 320–359. ISBN 978-1-4613-0449-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, R.K. Experiences and Lessons from the Use of TBM in the Himalaya—A Review. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 57, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, E.A. Systematic Review of Innovative Approaches in Tunnel Construction and Design. AJCBM 2024, 8, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Abdullah, R.A. A Review on Selection of Tunneling Method and Parameters Effecting Ground Settlements. EJEG 2016, 21, 4459–4475. [Google Scholar]

- Blajer, M. Tunnel Lining Design Using Convergence Confinement Method. Mater. Bud. 2023, 609, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Huang, L.; Liang, Y.; Du, F. Uneven Longitudinal Deformation Analysis of Prefabricated Subway Station Considering Nonlinear Behavior of Joints. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zheng, B.; Shen, J.; Chen, X.; Kong, H.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Cui, H. Intelligent Technologies for Tunnel Construction and Maintenance: A State-of-the-Art Review of Methods and Supporting Platforms. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 168, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huymajer, M.; Woegerbauer, M.; Winkler, L.; Mazak-Huemer, A.; Biedermann, H. An Interdisciplinary Systematic Review on Sustainability in Tunneling—Bibliometrics, Challenges, and Solutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission The European Green Deal. COM/2019/640 Final; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- European Commission A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. COM/2020/98 Final; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0098 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of 14 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02022L2464-20250417 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Cao, R.; Hao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liao, W. Emerging Trends in Lifecycle Assessment of Building Construction for Greenhouse Gas Control: Implications for Capacity Building. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossche, C.; Boel, V.; De Corte, W. Use of Life Cycle Assessments in the Construction Sector: Critical Review. Procedia Eng. 2017, 171, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, S.; Sigurjonsson, T.O. A Need for Standardized Approaches to Manage Sustainability Strategically. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korca, B.; Costa, E.; Bouten, L. Disentangling the Concept of Comparability in Sustainability Reporting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 815–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzentruber, L.D. Life Cycle Assessment Applied to the Construction of Tunnel. In Proceedings of the “SEE Tunnel: Promoting Tunneling in SEE Region” ITA WTC 2015 Congress and 41st General Assembly; Lacroma Valamar Congress Center: Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Bohne, R.A.; Bruland, A.; Jakobsen, P.D.; Lohne, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Norwegian Road Tunnel. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarast, P.; Bakhshi, M.; Nasri, V. Carbon Footprint Emissions of Different Tunneling Construction Methods. In Expanding Underground—Knowledge and Passion to Make a Positive Impact on the World- Proceedings of the ITA-AITES World Tunnel Congress, WTC 2023; Benardos, M., Ed.; CRC Press/Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 65–73. ISBN 9781003348030. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, R.; Pérez, F. Carbon Foot Print Evaluation in Tunneling Construction Using Conventional Methods. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 108, 103704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Cheng, H.; Zeng, T.; Deng, Z.; Lei, J. Carbon Emission Analysis of Tunnel Construction of Pumped Storage Power Station with Drilling and Blasting Method Based on Discrete Event Simulation. Buildings 2025, 15, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucal-Poyac, L.; D’alpos Schwartzentruber, L.; Fresnet-Féraille, A.; Subrin, D. Life Cycle Assessment of Tbm Tunnelling: Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analyses. 2025. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5291516 (accessed on 12 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.; Bascompta, M.; García, H. Carbon Footprint Evaluation in Tunnels Excavated in Rock Using Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM). Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 22, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lu, D.; Ji, G.; Liang, X.; Lin, Q.; Lv, J.; Du, X. A Lifecycle Carbon Emission Evaluation Model for Urban Underground Highway Tunnel Facilities. Undergr. Space 2025, 24, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, B.W.; Hoxha, E.; Scherz, M.; Heichinger, H.; Kreiner, H.; Passer, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Tunnel Structures: Assessment of the New Austrian Tunnelling Method Using a Case Study. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1078, 012117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Kou, L.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Evaluating Carbon Emissions during Slurry Shield Tunneling for Sustainable Management Utilizing a Hybrid Life-Cycle Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wałach, D.; Mach, A. Effect of Concrete Mix Composition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions over the Full Life Cycle of a Structure. Energies 2023, 16, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, A.; Szczygielski, M. Carbon Footprint Analysis throughout the Life Cycle of the Continuous Deep Mixing Method (CDMM) Technology. Energies 2024, 17, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A.R. Review on Tunnel Construction Method and Environmental Impact. IJATIR 2022, 4, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, F.S.; Ghafari, H.; Dianati, A. New Model for Environmental Impact Assessment of Tunneling Projects. J. Environ. Prot. 2014, 5, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolchandani, K. Industrial Byproducts in Concrete: A State-of-the-Art Review. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ye, X.; Cui, H. Recycled Materials in Construction: Trends, Status, and Future of Research. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvizu-Montes, A.; Guerrero-Bustamante, O.; Polo-Mendoza, R.; Martinez-Echevarria, M.J. Integrating Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for Optimizing the Inclusion of Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) in Eco-Friendly Cementitious Composites: A Literature Review. Materials 2025, 18, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, A.; Sagan, J.; Radziejowska, A. The Estimated Quantities of Building Demolition Waste. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2019, 65, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kępys, W.; Tora, B.; Václavík, V.; Jaskowska-Lemańska, J. The Effect of Recycled Wind Turbine Blade GFRP on the Mechanical and Durability Properties of Concrete. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, G.P.; Wałach, D. New Insights into Cement-Soil Mixtures with the Addition of Fluidized Bed Furnace Bottom Ashes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharghi, M.; Jeong, H. The Potential of Recycling and Reusing Waste Materials in Underground Construction: A Review of Sustainable Practices and Challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 1992-1-1:2008; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. Available online: https://wiedza.pkn.pl/wyszukiwarka-norm?p_auth=6gYIn8NS&p_p_id=searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_pos=1&p_p_col_count=2&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_standardNumber=PN-EN+1992-1-1%3A2008P&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_javax.portlet.action=showStandardDetailsAction (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- PN-EN 206+A2:2021-08; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://wiedza.pkn.pl/wyszukiwarka-norm?p_auth=6gYIn8NS&p_p_id=searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_pos=1&p_p_col_count=2&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_standardNumber=PN-EN+206%2BA2%3A2021-08P&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_javax.portlet.action=showStandardDetailsAction (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Sadowska-Buraczewska, B.; Grzegorczyk-Frańczak, M. Sustainable Recycling of High-Strength Concrete as an Alternative to Natural Aggregates in Building Structures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadesh, P.; Karthik, K.; Kalaivani, P.; Karalar, M.; Althaqafi, E.; Madenci, E.; Özkılıç, Y.O. Examining the Influence of Recycled Aggregates on the Fresh and Mechanical Characteristics of High-Strength Concrete: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 15804+A2:2020-03; Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations—Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://wiedza.pkn.pl/wyszukiwarka-norm?p_auth=6gYIn8NS&p_p_id=searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_pos=1&p_p_col_count=2&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_standardNumber=PN-EN+15804%2BA2%3A2020-03P&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_javax.portlet.action=showStandardDetailsAction (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- PN-EN 17472:2022-07; Sustainability of Construction Works—Sustainability Assessment of Civil Engineering Works—Calculation Methods. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://wiedza.pkn.pl/wyszukiwarka-norm?p_auth=6gYIn8NS&p_p_id=searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet&p_p_lifecycle=1&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_pos=1&p_p_col_count=2&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_standardNumber=PN-EN+17472%3A2022-07P&_searchstandards_WAR_p4scustomerpknzwnelsearchstandardsportlet_javax.portlet.action=showStandardDetailsAction (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Sala, S.; Crenna, E.; Secchi, M.; Pant, R. Global Normalisation Factors for the Environmental Footprint and Life Cycle Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-79-77214-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, S.; Cerutti, A.K.; Pant, R. Development of a Weighting Approach for the Environmental Footprint; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 9789279680410. [Google Scholar]

- Sphera. Available online: https://lcadatabase.sphera.com/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Hundt, C.; Pothen, F. European Post-Consumer Steel Scrap in 2050: A Review of Estimates and Modeling Assumptions. Recycling 2025, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Tae, S. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment Method for Concrete. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 27611–27632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, D. Economic and Environmental Assessment of New Generation Concretes. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 042013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameer, H.; Weber, V.; Mostert, C.; Bringezu, S.; Fehling, E.; Wetzel, A. Environmental Assessment of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete Using Carbon, Material, and Water Footprint. Materials 2019, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Ebid, A.M.; Riofrio, A.; Soleymani, A.; Baykara, H.; Kontoni, D.P.N.; Mahdi, H.A.; Jahangir, H. Global Warming Potential-Based Life Cycle Assessment and Optimization of the Compressive Strength of Fly Ash-Silica Fume Concrete; Environmental Impact Consideration. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 992552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Ahn, Y.H.; Tae, S.H. Proposal of Major Environmental Impact Categories of Construction Materials Based on Life Cycle Impact Assessments. Materials 2022, 15, 5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).