Abstract

Urban environments, particularly university campuses, are increasingly exposed to thermal discomfort due to the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect and intense solar radiation. This study evaluates the effectiveness of passive and hybrid cooling strategies, specifically sun-sail shading and mist cooling, in enhancing outdoor thermal comfort (OTC) in a university courtyard. The Van Dyck courtyard at the American University of Beirut, located on the East Mediterranean coast, was selected due to its heavy use between 10 am and 2 pm during summer, when ambient temperatures ranged between 32 and 36 °C and relative humidity between 21 and 33%. Thermal variations across four seating areas were analyzed using ENVI-met, a high-resolution microscale model validated against on-site data, achieving Mean Absolute Percentage Errors of 4% for air temperature and 5.2% for relative humidity. Under baseline conditions, Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) exceeded 58 °C, indicating severe thermal stress. Several mitigation strategies were evaluated, including three shading configurations, two mist-cooling setups, and a combined system. Results showed that double-layer shading reduced PET by 17.1 °C, mist cooling by 1.2 °C, and the combined system by 20.7 °C. Shading minimized radiant heat gain, while mist cooling enhanced evaporative cooling, jointly bringing thermal sensations closer to slightly warm–comfortable conditions. These cooling interventions also have sustainability value by reducing dependence on mechanically cooled indoor spaces and lowering campus air-conditioning demand. As passive or low-energy measures, shading and mist cooling support climate-adaptive outdoor design in heat-stressed Mediterranean environments.

1. Introduction

Outdoor thermal comfort (OTC) in university campuses is a critical component of environmental quality, directly influencing student health, performance, and use of outdoor spaces [1]. As campuses promote outdoor learning and social interaction, thermally responsive open areas become essential for maintaining student engagement throughout the year [2]. However, many campuses in hot or warm-temperate climates experience thermally stressful microclimates due to poor shading, high surface exposure, and insufficient passive cooling strategies [3,4].

Campus morphology often intensifies the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, with large paved surfaces, compact buildings, and limited vegetation raising local air temperatures above regional norms [5,6,7]. Materials such as asphalt and concrete, characterized by low albedo and high thermal capacity, further increase surface heat and longwave radiation [8]. As a result, studies across Mediterranean and warm-climate campuses report PET values exceeding 40 °C in exposed areas during summer, while shaded or vegetated zones demonstrate PET reductions of 6–12 °C and markedly improved comfort [9,10,11]. Passive cooling strategies such as vegetation, shading elements, and reflective pavements are widely used to mitigate heat stress [6,8,12]. Tree canopies and tensile shading structures effectively reduce mean radiant temperature, providing relief in circulation and seating areas [13]. Similarly, sun-sail shading systems have been shown to substantially reduce radiant load and improve thermal comfort in educational courtyards, highlighting their efficacy as practical passive cooling interventions in hot climates [14]. Green roofs, grassy courtyards, and cool pavements further enhance evapotranspiration and limit surface heating [8,11]. However, vegetation is not always feasible in dense courtyards where structural and irrigation constraints limit large-scale planting, making shading systems or hybrid cooling approaches more practical [15].

Water-misting systems offer a complementary cooling intervention by releasing fine droplets that evaporate, lowering the air temperature [16]. Under favorable wind and humidity conditions, courtyard misting installations have reported PET reductions of 6–8 °C [17], though performance depends strongly on local microclimatic conditions [18]. Recent work shows that combining shading with misting yields greater cooling than either strategy alone, as shading reduces solar load and improves droplet persistence [19]. For example, a courtyard at Xi’an University recorded PET reductions up to 14.4 °C using combined sun sails and misting nozzles [20]. System parameters such as nozzle height, spacing, and wind alignment strongly affect cooling extent [20,21], yet field-validated studies in campus settings remain limited.

Microclimate modeling tools like ENVI-met are widely used to evaluate campus cooling strategies before implementation. Prior studies report strong agreement between ENVI-met predictions and field measurements, with RMSE less than 1.5 °C and R2 greater than 0.85 [22,23]. These tools support the testing of shading layouts, green infrastructure, paving materials, and mist-cooling placement under consistent meteorological conditions [10]. Thermal comfort is commonly quantified using PET, UTCI, or SET, with PET being the most widely adopted in campus studies due to its compatibility with ENVI-met and its straightforward interpretation [15,24,25].

Although shading and misting have both been examined in previous outdoor thermal comfort studies, their combined performance has rarely been evaluated in Mediterranean university courtyards, and existing work often lacks validation against field-measured microclimatic conditions. For instance, Su et al. assessed various courtyard cooling measures on an arid-hot campus in China [26]. Their work has not considered hybrid shading–misting systems and the simulations were not calibrated against observed PET values, limiting the transferability of the findings to coastal Mediterranean climates, where humidity, sky-view factors, and radiative loads differ substantially. The present study addresses this gap by applying a fully validated ENVI-met model to quantify how artificial shading and evaporative misting interact under realistic site conditions, demonstrating their synergistic influence on PET rather than treating them as separate interventions. By evaluating performance both courtyard-wide and at seated user locations, this work provides evidence-based guidance on the spatial optimization of hybrid cooling strategies tailored specifically to Mediterranean university settings. Enhancing outdoor thermal conditions also carries broader sustainability implications for university campuses. When courtyards and semi-open spaces become thermally tolerable, occupants are less likely to retreat to mechanically cooled indoor environments, thereby reducing air-conditioning demand and associated energy use. Passive and hybrid cooling strategies, such as shading and evaporative misting, offer low-energy, low-carbon solutions that mitigate local heat stress while strengthening the resilience of public outdoor spaces. By quantifying the magnitude of cooling that can be achieved through these non-mechanical interventions, this study provides evidence supporting their role in reducing campus-wide cooling loads and advancing environmentally sustainable microclimate design.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Description: Van Dyck Courtyard

The American University of Beirut (AUB), located on the eastern Mediterranean coast (33.9° N, 35.5° E), serves over 10,000 students and features a compact campus composed of traditional sandstone and concrete buildings, paved courtyards, and tiered vegetation between upper and lower quadrants. The built environment includes extensive asphalt roads and brick walkways, which intensify solar heat gain and reduce surface cooling during summer.

Beirut’s hot Mediterranean climate is characterized by long, dry summers and mild, wet winters. During the summer, when outdoor areas are heavily used, ambient temperatures on campus range between 32 °C and 36 °C, while relative humidity varies between 21% and 33%, creating considerable heat stress for students and faculty in unshaded spaces.

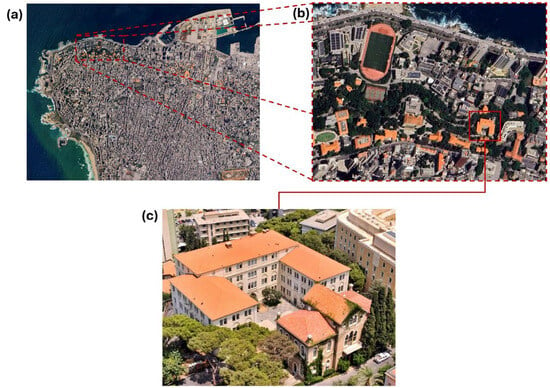

Many outdoor areas on campus are semi-enclosed and located near buildings, where limited airflow and direct solar radiation contribute to thermal discomfort. These zones, including courtyards and transitional paths, are actively used by students for circulation and outdoor breaks. One such space is the Van Dyck courtyard, which is surrounded by buildings on three sides and situated at a central campus node. This courtyard experiences stagnant air, strong solar exposure, and limited shading, making it both socially and thermally significant. Figure 1 shows the Van Dyck courtyard.

Figure 1.

(a) Satellite view of Beirut (b) satellite view of the AUB campus highlighting the Van Dyck courtyard and (c) Van Dyck courtyard.

This study, therefore, focuses on the Van Dyck courtyard as a reference case to evaluate passive and hybrid outdoor cooling strategies. Using a validated high-resolution ENVI-met model calibrated with on-site meteorological data, seven scenarios are tested, including three shading configurations, two misting layouts, and one ideal combined system. Thermal comfort is assessed at a pedestrian height of 1.7 m, representing the standard level for evaluating human thermal exposure while standing, consistent with prior studies [27]. The goal is to identify spatially optimized, low-energy strategies that can enhance outdoor thermal comfort (OTC) in hot-dry Mediterranean educational settings.

2.2. Overall Methodological Framework

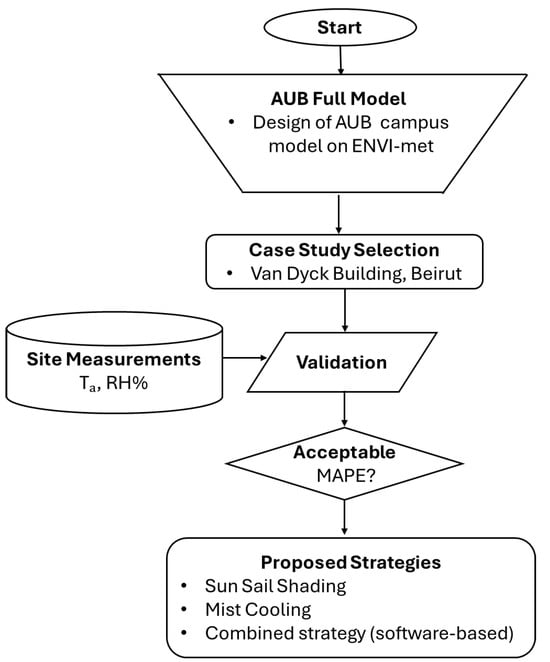

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of passive and hybrid cooling strategies in enhancing OTC at (AUB), this study adopts ENVI-met (version 5.6.1), a high-resolution three-dimensional microclimate simulation tool widely validated for urban environments. The methodology is structured into five key phases, as outlined in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Summary of the methodological workflow used in the study.

- Campus-wide simulation: A full-scale ENVI-met model of the AUB campus is developed to simulate microclimatic variables under typical summer conditions. Based on preliminary simulation, outdoor zones with high student circulation, particularly those with semi-enclosed geometry or limited ventilation, are identified. The Van Dyck courtyard is then selected for detailed analysis due to its exposure to direct sunlight, constrained airflow, and central location on campus.

- Numerical modeling and validation of the Van Dyck courtyard: A detailed ENVI-met model of the Van Dyck courtyard is constructed using accurate geometric, material, and vegetation parameters. To validate the model, on-site microclimatic data, air temperature (Ta), and relative humidity (RH), are recorded using a Davis Vantage Vue 6250UK weather station (Davis Instruments Corporation, Hayward, CA, USA). Measurements are taken at 1.7 m height to align with the pedestrian evaluation level. The recorded values are compared with ENVI-met simulation outputs, and the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) is calculated to assess the accuracy of the model under typical daytime conditions.

- Parametric simulation of cooling strategies: The validated model is used to test various interventions at the Van Dyck courtyard, including sun-sail shading, mist cooling, and a combined strategy integrating both. Simulations are conducted to assess the impact of each strategy on reducing PET under typical peak summer conditions.

2.3. Numerical Model

ENVI-met v5.6.1, a validated high-resolution microclimate model designed for urban environments, was used to simulate airflow, radiation, and thermal interactions across the AUB campus [23,28,29]. The model captures exchanges between buildings, vegetation, soil, and atmospheric conditions, making it well suited for evaluating outdoor thermal comfort.

Default ENVI-met formulations for turbulence, radiation, and soil–vegetation processes were adopted, as commonly applied in similar studies [22,30,31]. Simulations were conducted using a 1 m × 1 m × 1 m grid to resolve spatial variability around shading and mist-cooling interventions.

Shading structures were represented as single-wall elements positioned to block peak solar exposure, while mist emitters were defined as point sources using a 5 µm droplet size, consistent with prior research demonstrating high evaporative efficiency at this scale [23,27,32]. Evaporation was modeled through ENVI-met’s latent-heat exchange mechanism, allowing air temperature reductions to respond dynamically to wind speed, humidity, and turbulence.

The modeled domain (110 m × 91 m × 100 m) included refined near-ground layers to better resolve vegetation drag, radiative effects, and pedestrian-level airflow. Two standard ENVI-met input files were used: (1) a configuration file defining meteorological forcing and boundary conditions, and (2) a 3D geometry file specifying material properties, vegetation, and intervention layouts.

2.4. Research Site Thermal Map

To identify the most thermally stressed zones across campus, a preliminary ENVI-met simulation was conducted using version 5.6.1. The simulation covered the entire AUB campus using a horizontal domain size of approximately 214 m × 140 m and 55 m in height, with a spatial resolution of 4 m × 4 m × 3 m. A summary of key input parameters used in the simulation is provided in Table 1. Microclimatic variables simulated included air temperature (Ta), relative humidity (RH), wind velocity (Va), and Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET).

Table 1.

ENVI-met Model input parameters for the preliminary campus-wide simulation.

The results of this preliminary simulation were used to identify thermally vulnerable areas across the campus. Based on this, the Van Dyck courtyard emerged as the most critical hotspot and was selected for the second stage of the study, which involved constructing a high-resolution simulation domain focused exclusively on this area. Given its geometric exposure, persistent thermal stress, and functional importance as a heavily used circulation and seating space, the courtyard was chosen as the experimental site for evaluating the passive and hybrid cooling strategies—sun-sail shading, evaporative misting, and their combined implementation—under typical summer microclimatic conditions.

2.5. ENVI-Met Model Configuration

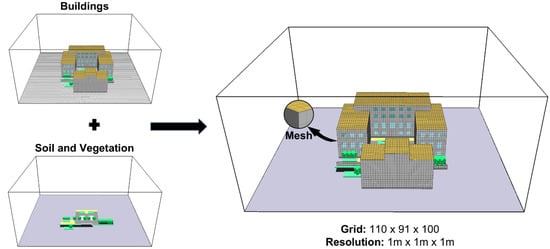

ENVI-met v5.6.1 was used to replicate the physical characteristics of the Van Dyck courtyard and evaluate the impact of sun-sail shading and mist-cooling strategies. The computational domain (110 × 91 × 100 m) was discretized using a 1 m resolution grid (110 × 91 × 30 cells), ensuring sufficient spatial detail to capture pedestrian-level microclimatic variations as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

ENVI-met 3D model of the Van Dyck courtyard with building geometry and ground materials.

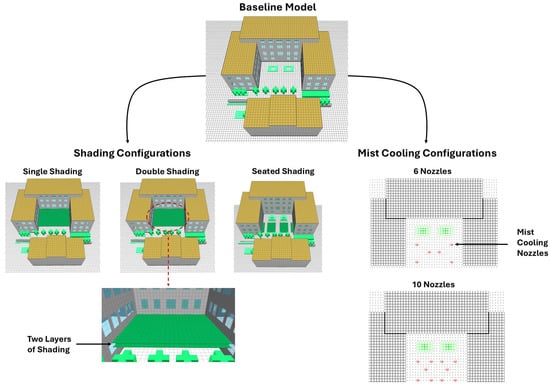

Sun-sail shading structures were elevated above seating zones to block direct solar exposure while allowing natural ventilation. Mist cooling was implemented using point-source emitters (6- and 10-nozzle systems, 0.9 L/min per nozzle) with a 5 μm droplet size selected for high evaporative efficiency under Beirut hot summer conditions. These configurations are consistent with previous studies demonstrating effective microscale cooling using similar misting densities and flow rates.

Validation simulations used a 24 h dataset collected from the weather station at the Raymond Ghosn Building (RGB) on the AUB campus. Parametric intervention simulations used representative summer boundary conditions from Beirut–Rafic Hariri International Airport. The courtyard consists of paved surfaces, sandstone façades, clear-glass windows, and tiled roofs that enclose the space on three sides, limiting ventilation and increasing radiant heat exchange. The ground includes asphalt, light and dark concrete, and brick pavements, all characterized by low to moderate albedo that contributes to midday heat buildup. Vegetation is sparse and includes grass patches, 2 m hedges, and several small to medium palm trees and an olive tree.

Modeling relied on field observations and available campus information to reproduce building geometry, vegetation, and material properties. Approximations were applied where detailed architectural data were unavailable. The Van Dyck building was modeled using sandstone walls, clear float glass windows, and clay tile roofing, based on AUB building documentation and ENVI-met material library. Emphasis was placed on accurately representing thermophysical properties such as absorptivity, emissivity, and thermal conductivity, as shown in Table 2. Surrounding pavements (asphalt, concrete, brick) were assigned to typical albedo and emissivity values consistent with local construction practices as in Table 3.

Table 2.

Building material properties used in the Van Dyck model.

Table 3.

Surface and soil properties near Van Dyck courtyard.

Vegetation Representation

Vegetation was represented in ENVI-met based on site observations and scaled measurements of height and canopy structure. Grass, hedges, and palm trees were modeled as 3D vegetation types (Table 4), using standard parameter values from the ENVI-met database for albedo, emissivity, plant height, and root depth.

Table 4.

Vegetation types and their thermophysical characteristics.

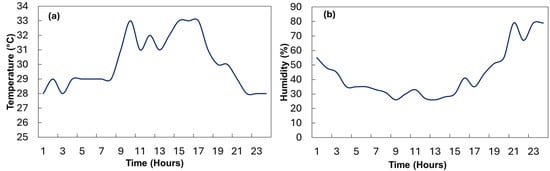

2.6. Boundary Conditions

Atmospheric boundary conditions were defined using a forcing file specifying hourly air temperature, wind speed, wind direction, and relative humidity for the selected simulation day. Validation runs used on-site data from the Raymond Ghosn Building (RGB) weather station, while parametric simulations used representative summer conditions from the Beirut–Rafic Hariri International Airport, located 8 km from the study site—a common approach when extended on-site records are unavailable. Parametric simulations were performed for a full 24 h period on 18 August 2018, representing typical hot summer conditions in Beirut. Wind speed was set to an average of 3 m/s, and wind direction was fixed at 270°, capturing the dominant westerly flow. The Simple Forcing method in ENVI-met v5.6.1 was applied, as widely used in urban microclimate studies [33]. Baseline inputs used across all scenarios are summarized in Table 5. The temporal variation in air temperature and relative humidity applied in the parametric runs is shown in Figure 4.

Table 5.

Baseline configuration in the ENVI-met simulation.

Figure 4.

Input boundary conditions used in the simulations: (a) hourly air temperature profile and (b) hourly relative humidity profile for a representative summer day in Beirut.

2.7. Cooling Strategy Simulation Scenarios

To evaluate the performance of different passive and hybrid cooling strategies at the Van Dyck courtyard, seven simulation scenarios were developed using the validated ENVI-met model. These scenarios test a range of interventions, including shading types and misting densities, both individually and in combination. Figure 5 summarizes the simulated cases (not including the combined case).

Figure 5.

Overview of the simulated artificial shading and evaporative mist-cooling configurations tested in the Van Dyck courtyard, including the three shading layouts and the two misting scenarios.

Shading and misting systems were modeled in ENVI-met as previously described. In this phase, simulations focused on assessing the performance of the double-layer sun-sail configuration (4 m and 3 m heights) and its combination with full misting coverage (10 nozzles, 5 μm droplets) to evaluate their synergistic cooling effects during peak hours (11:00–15:00 h).

The set of shading and misting configurations evaluated in this study was restricted to solutions that can be realistically implemented in the Van Dyck courtyard. The courtyard geometry, its limited capacity to accommodate additional vegetation, structural constraints, and installation feasibility all conditioned the number and type of scenarios that could be tested. As a result, the simulation set focuses on a targeted group of applied, site-specific interventions, rather than on an exhaustive parametric optimization exploring hypothetical design variations that may not be feasible in practice.

All cases used the same meteorological inputs, ground conditions, and simulation period to ensure consistent comparison.

2.8. Validation

Boundary Conditions and Field Measurements

To validate the reliability of the ENVI-met (v5.6.1) model in simulating the microclimate conditions of the Van Dyck courtyard, field measurements were conducted using the Davis Vantage Vue 6250UK weather station. The station was positioned at a designated high-PET location identified in the preliminary simulation, selected for its prolonged exposure to solar radiation and minimal shading. Mounted at 1.7 m height to approximate the human biometeorological reference level, the station recorded air temperature (Ta), relative humidity (RH), and wind direction at 1 min intervals, which were then averaged over 1 h periods to match the temporal resolution of the ENVI-met simulation outputs. For the validation run, the model’s boundary conditions were taken from a nearby weather station located at the American University of Beirut, ensuring that the simulation inputs reflected the same meteorological conditions recorded during the measurement campaign.

Measurements were carried out on 18 February, from 9:00 to 17:00 h, respectively. Sensor specifications are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Sensor specifications for on-site weather measurements.

The validation was conducted by comparing the ENVI-met simulation outputs for Ta, and RH with the field measurements. To quantify model performance, the MAPE was employed as the primary accuracy metric. MAPE was computed using the formula:

where MAPE measures the average percentage absolute error between the simulated () and experimental () values across data points and i represents the index of each data point in the dataset, ranging from 1 to n, where n is the total number of observations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Validation Results

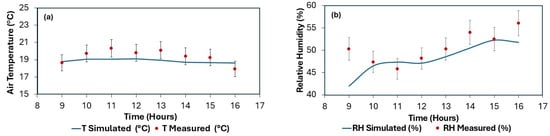

The ENVI-met simulation demonstrated strong agreement with the field data. For air temperature, the hourly comparison between measured and simulated values yielded a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 4%, confirming the model’s ability to reproduce daily temperature variation with high accuracy (Figure 6a). For relative humidity, the average MAPE was 5.2%, with slightly higher discrepancies in early morning hours due to condensation effects and rapid RH fluctuations (Figure 6b). These low error margins affirm the model’s reliability in simulating thermal and humidity conditions in the courtyard.

Figure 6.

Model validation results comparing simulated and measured microclimatic variables at the Van Dyck courtyard at 18 February 2024. (a) Hourly air temperature profile showing simulated and measured values, (b) Hourly relative humidity profile showing simulated and measured values.

3.2. Baseline Thermal Characterization

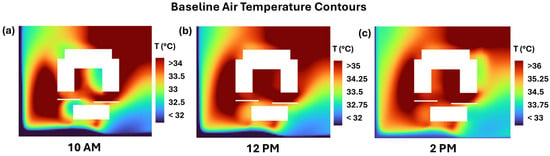

The baseline simulation shows that the Van Dyck courtyard experiences substantial heat stress during summer, with potential air temperature reaching 34–35 °C in exposed zones by midday (Figure 7). Cooler pockets (31–32 °C) appear only along shaded façades, indicating that localized shading offers limited thermal relief in the absence of broader coverage.

Figure 7.

Contours for Potential Air Temperature of the baseline case at (a) 10 AM, (b) 12 PM, and (c) 2 PM.

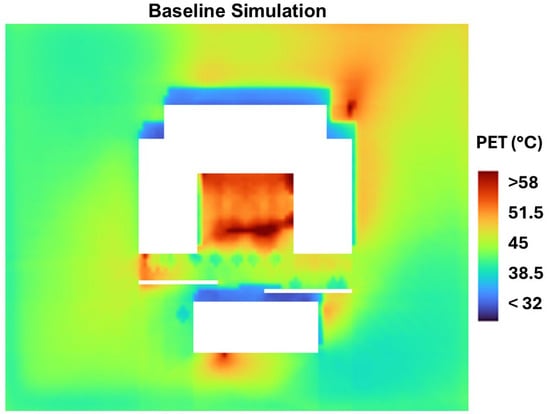

However, PET distributions reveal a much more severe thermal condition than air temperature alone suggests. At 12:00 PM, PET exceeds 51 °C and reaches nearly 58 °C in the southern exposed region (Figure 8), placing the courtyard in the extreme heat stress category. This contrast reinforces a key microclimatic principle: mean radiant temperature (MRT) is the dominant driver of thermal discomfort in sun-exposed courtyards, while air temperature plays a secondary role.

Figure 8.

PET distribution for baseline case at 12:00 PM.

The enclosed geometry of the courtyard, combined with low vegetation density and stagnant airflow, further amplifies heat accumulation, consistent with previous findings on the influence of urban form and sky-view factor on outdoor thermal comfort [34]. These baseline findings establish the physical context for assessing interventions: strategies must primarily target radiative load reduction and secondarily air-temperature moderation to meaningfully improve outdoor comfort.

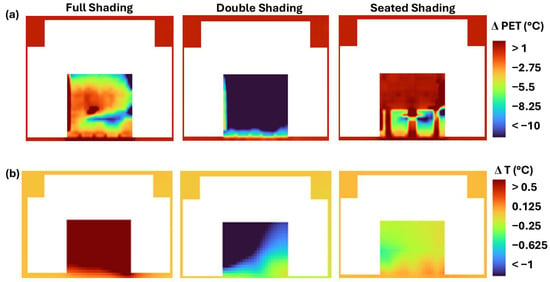

3.3. Performance of Artificial Shading Strategies

The shading interventions generated distinct modifications to the courtyard microclimate (Figure 9a,b). In the full-shading configuration, potential air temperature increased slightly by approximately 0.5 °C (Figure 9b), while PET decreased by 2–5 °C (Figure 9a). This response illustrates the predominance of mean radiant temperature (MRT) in shaping outdoor thermal comfort, as reductions in radiative exposure can outweigh minor increases in air temperature. Similar findings have been reported in Mediterranean courtyard studies where MRT was identified as the dominant predictor of PET under summer conditions [14,23].

Figure 9.

(a) PET distribution, (b) Potential air temperature distribution for shading cases at 12:00 PM.

The double-shading configuration produced the most substantial thermal improvement. PET reductions exceeded 12 °C across much of the courtyard (Figure 9a), accompanied by a modest decrease in air temperature of approximately 1 °C (Figure 9b). The enhanced performance can be attributed to the dual-layer geometry, which increases solar obstruction, reduces heating of the shading fabric, and limits longwave re-radiation toward the pedestrian level. Such multi-layer shading systems have previously been shown to offer superior radiative attenuation in semi-enclosed outdoor spaces [32,35].

In contrast, the seated-shading configuration provided only localized cooling directly beneath the shading footprint, with minimal influence on PET or air temperature elsewhere (Figure 9a,b). Because this intervention modifies the radiative field only within a small area, the broader courtyard remains exposed to direct and reflected solar radiation. This outcome aligns with other studies where small-scale shading structures were found to have limited spatial reach and negligible courtyard-wide impact on MRT [23].

Overall, the comparative performance of the three configurations reinforces the principle that the spatial extent and radiative behavior of shading systems are the primary determinants of their thermal effectiveness in high-radiation environments. The present results are consistent with observations from Mediterranean and hot-arid courtyards, where broad-coverage shading solutions have been shown to produce the largest PET

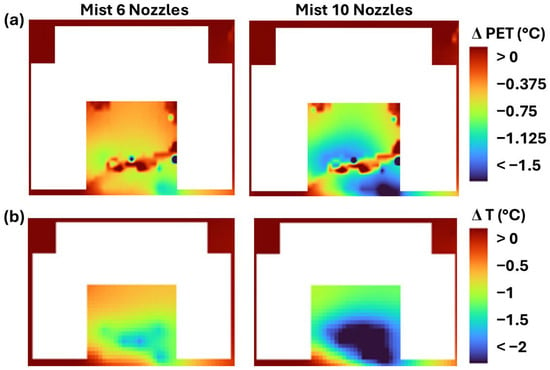

3.4. Cooling Effectiveness of Evaporative Misting

The evaporative misting strategies produced localized but modest improvements in thermal comfort and air temperature (Figure 10a,b). At 12:00, the 6-nozzle system decreased potential air temperature by about 1–1.3 °C compared to baseline (Figure 10b), while PET reductions were more limited, at roughly 0.5 °C concentrated near the nozzles (Figure 10a). Expanding to 10 nozzles achieved a greater cooling effect: potential air temperature decreased by about 2 °C, with PET reductions of around 1–1.2 °C that extended across a broader footprint. The higher mist density enhanced evaporative heat loss and maintained localized cooling for a longer duration.

Figure 10.

(a) PET distribution, (b) Potential air temperature distribution for mist cooling cases at 12:00 PM.

The limited overall effectiveness of mist cooling in terms of PET can be explained by its physical mechanism. While misting reduces air temperature and increases relative humidity, it has little effect on mean radiant temperature (MRT), which is the dominant driver of PET in sun-exposed courtyards. As a result, mist cooling alone cannot substantially reduce PET.

These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that misting systems in open courtyards rarely achieve more than 1–2 °C PET reduction unless combined with shading [23,32]. When shading first reduces MRT, misting becomes more effective because the body is more sensitive to changes in air temperature [17,36]. Accordingly, mist cooling is best regarded as a supplementary strategy, enhancing comfort in shaded areas rather than as a stand-alone courtyard-wide intervention.

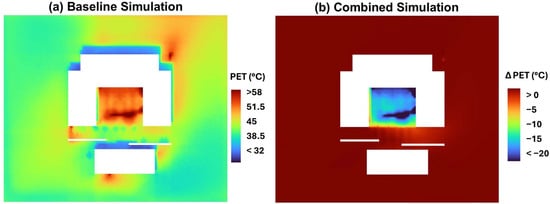

3.5. Combined Cooling Strategy: Double Shading + 10 Nozzles

The combined strategy, integrating double shading with a 10-nozzle misting system, achieved the largest overall PET reduction among all interventions (Figure 11). At 12:00 PM, the ΔPET map shows reductions exceeding −15 °C across most of the courtyard compared to baseline PET, representing the most significant improvement in thermal comfort.

Figure 11.

(a) PET distribution (°C) under baseline simulation at 12:00 PM, (b) ΔPET (°C) distribution for combined shading +10 nozzles compared to baseline at 12:00 PM.

The effectiveness of this combined strategy can be explained by its complementary physical mechanisms. Shading primarily reduces mean radiant temperature (MRT) by blocking direct solar radiation and lowering surface heat gains. Since MRT is the dominant driver of PET in outdoor spaces, this reduction forms the basis of the cooling effect. Misting, meanwhile, lowers air temperature through evaporative cooling and increases relative humidity. While mist alone has a limited influence on PET under direct sun, its effect is amplified in shaded conditions, where the reduced radiant load makes occupants more sensitive to changes in air temperature.

Together, shading and misting act synergistically: shading first minimizes radiant heat stress, and misting then enhances comfort by cooling the air in those shaded zones. This explains why the greatest improvements occurred in partially shaded areas, where misting provided additional relief beyond shading alone.

The pronounced PET reductions observed under the combined configuration indicate a clear microclimatic synergy between the two cooling mechanisms. Shading substantially reduces MRT, the primary determinant of outdoor thermal stress in Mediterranean courtyards, thereby lowering the radiative heat load on the human body. Once MRT is suppressed, the relative contribution of air temperature to thermal perception increases, enabling evaporative mist cooling to deliver a much larger PET reduction than when applied alone. This explains why misting by itself produces only localized cooling, whereas in the shaded configuration the same misting system yields PET reductions of 15–21 °C across the seating areas. This synergistic interaction, in which radiative suppression enhances evaporative efficiency, represents an important mechanistic insight consistent with previous findings on combined passive–hybrid cooling systems in hot-arid and Mediterranean climates [23,32,35].

These results are consistent with benchmarks in the literature. Previous studies have reported that shading alone can reduce PET by 6–12 °C, while misting rarely exceeds 1–2 °C. When combined, however, PET reductions of 8–15 °C have been documented in Mediterranean and hot-arid courtyards [23,35]. This confirms the importance of adopting integrated passive cooling strategies to maximize thermal comfort in outdoor university settings.

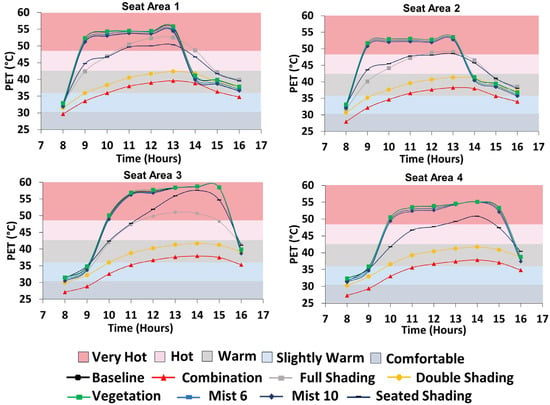

3.6. Seated Area Thermal Comfort Analysis

To assess user-relevant thermal conditions, PET was evaluated at four seating points (S1–S4) throughout the day under all intervention scenarios (Figure 12). Baseline PET values were slightly warm in the morning (≈32–33 °C) but exceeded 50–58 °C between 9:00 and 13:00, indicating extreme heat stress. The combined double-shading +10-nozzle configuration produced the largest improvements, reducing PET by 15–21 °C during these peak hours (Table 7). These reductions shifted thermal sensation from very hot to slightly warm or warm, demonstrating substantial comfort gains.

Figure 12.

Hourly Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) trends at the four seating locations (S1–S4) under all simulated cooling strategies.

Table 7.

Change in PET (ΔPET, °C) at the four seating points (S1–S4) between 8:00 and 16:00.

Cooling effectiveness varied spatially. The most exposed locations, S3 and S4, showed the greatest improvements (up to 21 °C), reflecting their high baseline MRT. Locations receiving partial building shade (S1 and S2) exhibited smaller but still meaningful reductions (15–19 °C). Afternoon cooling (≈2–5 °C) was more modest but continued to shift thermal sensation toward more tolerable levels.

Overall, the seated-area analysis confirms that the hybrid intervention is most effective during midday, when radiant load is highest, and highlights the importance of targeting high-exposure seating zones in courtyard design.

3.7. Discussion

The results confirm that thermal discomfort in the Van Dyck courtyard is driven primarily by high radiant loads, reflected in baseline midday PET values exceeding 50 °C. Among the individual interventions, shading produced the largest improvement because reducing mean radiant temperature directly lowers PET across the courtyard. Misting alone generated only modest and highly localized cooling, consistent with its limited influence on radiant heat. The combined double-shading and 10-nozzle misting strategy delivered the most substantial comfort enhancement, demonstrating that lowering MRT first enables evaporative cooling to produce stronger reductions in air temperature and PET. Spatial differences between the seating points further highlight the role of geometry: areas with higher exposure benefited most from the hybrid intervention, whereas partially shaded locations showed smaller reductions because their baseline radiative load was already lower. Overall, the findings reinforce that integrated shading–misting systems provide the most effective relief during peak heat periods in compact Mediterranean courtyards. These microclimatic improvements also translate into broader sustainability benefits. By reducing extreme radiant loads in highly exposed spaces, such passive and hybrid interventions can decrease the tendency for occupants to migrate to air-conditioned interiors, thereby lowering building cooling demand during peak hours.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This study quantified the effectiveness of shading, misting, and hybrid cooling strategies in improving outdoor thermal comfort in the Van Dyck courtyard at the American University of Beirut, a compact Mediterranean site strongly influenced by Urban Heat Island conditions. Using validated ENVI-met simulations, baseline results confirmed extreme midday heat stress with PET values above 50 °C. The main findings were:

- Among the tested interventions, double-layer shading produced the greatest single-mechanism improvement

- Misting alone yielded only localized cooling.

- The combined double-shading and 10-nozzle system demonstrated the strongest overall performance, reducing PET by up to 20–21 °C and shifting thermal sensation from very hot to slightly warm, underscoring the synergistic interaction between radiative and evaporative cooling.

The above findings provide practical and transferable guidance for designing climate-resilient outdoor spaces on dense university campuses. Future work should extend this analysis to additional hybrid strategies such as shading + misting + high-albedo pavements or enhanced vegetation, assess water-use efficiency and droplet dynamics in mist systems, and conduct multi-season validation across varied courtyard geometries. Broader sensitivity analyses, including variations in nozzle configuration, wind patterns, and shading materials, would further support generalizable recommendations and inform optimization under projected climate-change scenarios.

From a sustainability perspective, the demonstrated reductions in PET illustrate how passive and hybrid outdoor cooling strategies can reduce reliance on energy-intensive indoor air-conditioning, thereby contributing to lower campus energy use and improved climate resilience.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Z.D., H.K. and N.G. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Z.D. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Munib and Angela Masri Institute of Energy and Natural Resources at the American University of Beirut] grant number [104379].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the undergraduate Final Year Project (FYP) team, Salman Al Masri, Muhammad Badreddine, Roy Bou Nasreddine, and Mohammad Fawaz, for their assistance in data collection and site measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Ta | Air temperature (°C) |

| RH | Relative Humidity (%) |

| Va | Air velocity (m/s) |

| PET | Physiological Equivalent Temperature (°C) |

| MRT | Mean Radiant Temperature (°C) |

| Q | Heat flux (W/m2) |

| ΔPET | Change in Physiological Equivalent Temperature (°C) |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (%) |

| dp | Droplet diameter (µm) |

| Λ | Latent heat of vaporization (J/kg) |

| Ε | Emissivity |

| A | Absorptivity/Albedo coefficient |

| K | Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) |

| cp | Specific heat capacity (J/kg·K) |

| Ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| H | Convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2·K) |

| Greek Symbols | |

| ε | Emissivity of surface or material |

| α | Solar absorptivity |

| λ | Latent heat of vaporization |

| Abbreviations | |

| AUB | American University of Beirut |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| OTC | Outdoor Thermal Comfort |

| PET | Physiological Equivalent Temperature |

| MRT | Mean Radiant Temperature |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| ADI | Alternating Direction Implicit |

| URANS | Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| ENVI-met | Environmental Meteorology Simulation Tool |

| RGB | Raymond Ghosn Building |

| ΔPET | PET reduction compared to baseline |

| Subscripts | |

| a | Air |

References

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Hussein, S.W.; Nayel, M. The impact of outdoor shading strategies on student thermal comfort in open spaces between education building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 58, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E. Outdoor thermal comfort and outdoor activities: A review of research in the past decade. Cities 2012, 29, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, J.; De Dear, R. A field study of thermal comfort in outdoor and semi-outdoor environments in subtropical Sydney Australia. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deilami, K.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Liu, Y. Urban heat island effect: A systematic review of spatio-temporal factors, data, methods, and mitigation measures. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 67, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Using cool pavements as a mitigation strategy to fight urban heat island—A review of the actual developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, H. Field survey on local thermal comfort of students at a university campus: A case study in shanghai. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Berardi, U.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Al-Obaidi, K. Analyzing the thermal comfort conditions of outdoor spaces in a university campus in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 1327–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.M.; Othman, E.; Mohamed, A.F.; Ragab, A. Quantifying the impacts of courtyard vegetation on thermal and energy performance of university buildings in hot arid regions. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.A. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies for Enhancing Student Thermal Comfort in the Educational Buildings of Sohag University. Buildings 2025, 15, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.C.; Weng, J.; Liu, K.; Hang, J. The effects of shading devices on outdoor thermal and visual comfort in Southern China during summer. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgheznawy, D.; Eltarabily, S. The impact of sun sail-shading strategy on the thermal comfort in school courtyards. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebsafa, S.; Taheri Shahraeini, M.; Yang, X.; Rabiei, M. Impact of providing shade on outdoor thermal comfort during hot season: A case study of a university campus in cold semi-arid climate. Renew. Energy Res. Appl. 2023, 4, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ulpiani, G. Water mist spray for outdoor cooling: A systematic review of technologies, methods and impacts. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z. Assessment of combined passive cooling strategies for improving outdoor thermal comfort in a school courtyard. Build. Environ. 2024, 252, 111247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Okumiya, M.; Tsujimoto, M.; Harada, M. Study on cooling effect with water mist sprayer: Measurement on global loop at the 2005 world exposition. In Architectural Institute of Japan Congress; Architectural Institute of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, E.; Zheng, X.; Wood, C.J. Numerical and experimental validations of the theoretical basis for a nozzle-based pulse technique for determining building airtightness. Build. Environ. 2021, 188, 107459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyogoku, S.; Takebayashi, H. Experimental verification of mist cooling effect in front of air-conditioning condenser unit, open space, and bus stop. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, R.; Kale, S.; Dhar, P. Heat and mass transfer processes between a water spray and ambient air–I. Experimental data. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhou, B. Optimizing Vegetation Configurations for Seasonal Thermal Comfort in Campus Courtyards: An ENVI-Met Study in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Climates. Plants 2025, 14, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe, E.; Ulpiani, G.; Cancellieri, C.; Di Perna, C.; D’Orazio, M.; Zinzi, M. Numerical modelling and experimental validation of the microclimatic impacts of water mist cooling in urban areas. Energy Build. 2021, 231, 110638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendritzky, G.; De Dear, R.; Havenith, G. UTCI—Why another thermal index? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, W.; Qin, Z.; Mu, T.; Ge, Z.; Dong, Y. Evaluating thermal comfort indices for outdoor spaces on a university campus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, W. UTCI assessment of outdoor thermal comfort in Arid-Hot university campuses during summer. Energy Build. 2025, 351, 116683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachmar, H.; Younes, J.; Ghaddar, N. Effectiveness of outdoor windcatcher and mist cooling in mitigating urban heat and improving pedestrian thermal comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 132, 106838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, T.; Li, Q.; Mochida, A.; Meng, Q. Study on the outdoor thermal environment and thermal comfort around campus clusters in subtropical urban areas. Build. Environ. 2012, 52, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabawi, M.H.; Hamza, N.; Dudek, S. Numerical modelling evaluation for the microclimate of an outdoor urban form in Cairo, Egypt. HBRC J. 2015, 11, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, H.; Toparlar, Y.; Blocken, B.; Hensen, J. Simulating the cooling effects of water spray systems in urban landscapes: A computational fluid dynamics study in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Middel, A.; Fang, X.; Wu, R. ENVI-met model performance evaluation for courtyard simulations in hot-humid climates. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G.; Di Giuseppe, E.; Di Perna, C.; D’ORazio, M.; Zinzi, M. Thermal comfort improvement in urban spaces with water spray systems: Field measurements and survey. Build. Environ. 2019, 156, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eingrüber, N.; Korres, W.; Löhnert, U.; Schneider, K. Investigation of the ENVI-met model sensitivity to different wind direction forcing data in a heterogeneous urban environment. Adv. Sci. Res. 2023, 20, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Emmanuel, R. The influence of urban design on outdoor thermal comfort in the hot, humid city of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2006, 51, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.H.; Tan, C.L.; Kolokotsa, D.D.; Takebayashi, H. Greenery as a mitigation and adaptation strategy to urban heat. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.M.A.; Abdallah, A.S.H. Assessment of outdoor shading strategies to improve outdoor thermal comfort in school courtyards in hot and arid climates. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).