Abstract

To address the contradiction between the widespread prevalence of selenium deficiency and the growing demand for selenium-enriched fruits, this study utilized phosphate tailings (industrial solid waste), wood vinegar (a by-product of forestry processing), biochemical fulvic acid, and alginic acid (renewable biomass resources) to construct an organic–inorganic composite soil selenium activator. This formulation enhances the mobilization of inherent selenium in the soil without relying on exogenous selenium supplementation, thereby improving selenium bioavailability while mitigating the environmental pollution and resource depletion associated with external selenium inputs. Through field experiments, we systematically evaluated the influence of varying activator dosages on soil physicochemical properties, available selenium content, selenium distribution in different citrus organs, and fruit quality. The results demonstrated that the application of the compound activator at 600 g/plant significantly increased (p < 0.05) soil available selenium and fruit selenium content by 21.26% and 21.06%, respectively. During the fruit expansion stage of Sugar Orange, soil available selenium was elevated by 21.8%, which corresponded to a 21.09% increase in fruit selenium content. Regarding fruit quality parameters, Sugar Orange exhibited increases in soluble solids (35.8%), citric acid (20.3%), solid-to-acid ratio (77.8%), and selenium content (223.3%). In Rock Sugar Orange, significant enhancements were observed in soluble solids (46.1%), vitamin C (45.3%), total soluble sugars (73.4%), solid-to-acid ratio (156.6%), and selenium content (69.7%). Structural equation modeling revealed that soil available selenium, soil properties, and selenium content in citrus organs collectively exerted positive regulatory effects on fruit quality. Specifically, juice selenium content showed significant positive correlations with fruit shape index, individual fruit weight, soluble solids content, and solid-to-acid ratio. This strategy achieves the synergistic reuse of industrial solid waste and agricultural biomass resources, offering a green and sustainable pathway to enhance selenium content and quality in citrus fruits.

1. Introduction

Selenium is an essential trace element for the human body and is crucial for maintaining health. Selenium deficiency affects up to 2 billion people across vast regions worldwide [1]. Many regions in Africa, such as Malawi and Ethiopia, face widespread risks of selenium deficiency [2]. Selenium-deficient regions also exist in the United States, Finland, New Zealand, and parts of Europe [3]. China is one of the countries with the most heterogeneous distribution of soil selenium globally, containing extensive low-selenium areas. A low-selenium belt with soil selenium concentrations below 0.125 mg/kg stretches from Heilongjiang Province in northeastern China to Yunnan Province in the southwest. Approximately 51% of the soil nationwide is classified as selenium-deficient [4]. Currently, approximately one billion people worldwide face the risk of selenium deficiency, as the low bioavailability of soil selenium restricts its bioaccumulation capacity in crops [5,6]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to enhance the development of selenium-enriched agricultural products, particularly selenium-fortified fruits and vegetables. To address selenium deficiency in agricultural products, the primary approaches adopted both domestically and internationally involve exogenous selenium application, such as soil selenium fertilization [7] and foliar selenium spraying [8]. Only a small portion of selenium applied to soil can be utilized by plants, with the majority remaining in the soil. Some of this residual selenium may be lost through volatilization, leaching, or surface runoff, posing potential risks to environmental ecosystems [9]. Selenium applied through foliar spraying can be directly absorbed by leaves, resulting in high utilization efficiency and precise control of the final selenium content in crops. Additionally, this method effectively prevents selenium from being fixed by soil, thus having minimal impact on the soil ecosystem. However, foliar selenium application requires specialized equipment such as sprayers and must be carried out during critical growth stages of the crops. Furthermore, foliar fertilization generally requires more frequent applications compared to soil fertilization. These factors contribute to the need for specialized equipment and labor inputs, which may lead to significant costs for fuel, equipment maintenance, and labor in large-scale agricultural production [10,11].

Selenium exists in soils primarily in four valence states: selenides (Se2−), elemental selenium (Se0), selenite (SeO32−), and selenate (SeO42−). The solubility and mobility of selenium generally increase with rising redox potential [12]. The transport capacity of selenium is a complex process governed by multiple factors including soil pH, texture/structure, organic matter content, iron/aluminum oxides, redox conditions, and microbial activity. Under acidic conditions, iron and aluminum oxides in the soil adsorb selenite ions, strongly immobilizing them and significantly reducing selenium mobility, whereas under alkaline conditions, selenium primarily exists as highly soluble selenate, exhibiting substantial mobility [13]. Clay soils, containing more iron/aluminum oxides and clay minerals, exhibit a significantly stronger capacity to adsorb and immobilize selenium than sandy soils. Consequently, selenium presents higher migration risks in sandy soils. Dissolved organic matter can form soluble organic–selenium complexes (particularly with selenite), enhancing its mobility in soil solution compared to free selenium ions. Under aerobic (oxidizing) conditions, selenium tends to be oxidized to soluble selenate (SeO42−) [14], which is highly mobile. Under anaerobic (reducing) conditions (such as in flooded paddy fields), microorganisms utilize selenate and selenite as electron acceptors, reducing them to insoluble elemental selenium (Se0) or selenides (Se2−), thereby immobilizing them in the soil [15]. Some microorganisms convert inorganic selenium into volatile dimethylselenide ((CH3)2Se), enabling selenium transfer from soil to the atmosphere through gaseous pathways; sulfate-reducing bacteria can reduce selenate/selenite to Se0, which can be applied in bioremediation. Certain chemolithoautotrophic bacteria can oxidize Se0 or Se2− to SeO42−, reactivating selenium mobility [16].

Plants exhibit significant differences in their capacity to absorb and translocate selenium. Based on their selenium accumulation levels, plants are generally categorized into three types: selenium hyperaccumulators, selenium accumulators, and non-accumulators [17]. Selenium hyperaccumulators (such as Brassicaceae species (e.g., Brassica juncea) and certain Astragalus species) often possess unique physiological mechanisms, including efficient selenium uptake systems and the ability to convert selenium into less toxic organic selenium compounds [18]. The vast majority of crop species, such as rice, corn, wheat, soybean, tomato, and lettuce, are classified as non-accumulators. These plants generally exhibit relatively low capacity for selenium absorption and translocation, and are susceptible to toxicity under high selenium concentrations [17].

The bioavailability of soil selenium is highly dependent on its chemical speciation. Soluble selenium (SOL-Se) and exchangeable selenium (EX-Se) are directly available for plant uptake. In contrast, residual selenium (RES-Se) exists in a highly stable form with minimal bioavailability, making it largely inaccessible to plants. However, RES-Se serves as a crucial reservoir and source in soils [19]. The low bioavailability of soil selenium limits the development of selenium-rich crops [5]. Humans primarily obtain selenium through plant-derived foods [20]. The accumulation characteristics of selenium in different crop organs vary depending on plant species, soil selenium content, selenium speciation, and environmental conditions [21]. The forms of selenium that enter the human body through edible plant parts mainly include inorganic selenium (such as selenite and selenate) and organic selenium (such as selenomethionine and selenocysteine), with organic selenium species generally exhibiting higher bioactivity and lower toxicity [22]. Therefore, converting stable selenium into bioavailable forms is central to enhancing selenium bioavailability [23].

In this context, the organic–inorganic composite activation strategy has emerged as a highly effective approach. This method combines the benefits of both organic and inorganic activators, enhancing selenium absorption efficiency while balancing environmental sustainability and economic feasibility. Such compound activators have demonstrated efficacy in the agronomic biofortification of crops such as rice [24] and potatoes [25]. For instance, the addition of humic acid to selenium solutions has been shown to promote selenium uptake and translocation in plants [25]. Selenium compound activators promote the growth of specific microbial taxa beneficial for selenium transformation by modifying the soil environment (e.g., pH, moisture status, and nutrient availability) [26,27]. Following the alterations in microbial community structure and selenium speciation induced by the compound activator, subsequent changes in soil physicochemical properties may in turn affect microbial activity and further selenium transformation, forming a complex feedback loop [28]. Despite these advances, a comprehensive understanding of selenium biofortification specifically for the edible parts of fruit crops remains lacking.

As one of the most extensively consumed fruits worldwide, citrus is valued for its diverse content of essential trace nutrients. However, substantial variation in nutritional traits exists among cultivars. Research has demonstrated that the Tomorrow variety accumulates notably higher levels of total soluble sugars compared to other citrus varieties [29], a characteristic that makes it a relevant model for studying quality improvement through agronomic practices such as selenium biofortification. To address dietary selenium requirements, the production of selenium-enriched citrus offers a viable pathway to elevate daily selenium intake while mitigating the potential risks associated with excessive consumption from mineral supplements. However, few studies have examined the application of compound activators in citrus cultivation, and their impacts on fruit quality indices and nutritional composition remain incompletely understood. To address these challenges, this study employed an organic–inorganic compound activator designed to mobilize soil selenium through multiple synergistic mechanisms. Specifically, humic acid promotes the competitive adsorption and desorption of selenium fixed by iron/aluminum oxides; Phosphorus tailings facilitate the release of interlayer selenium from clay minerals through anion exchange; and microbial metabolites contribute to the degradation of organic matter-selenium complexes, thereby enhancing selenium bioavailability [30]. Furthermore, humic acid enhances root development and increases the selenium bioconcentration factor (BCF), while rhizosphere microorganisms secreting ACC deaminase activate the expression of phloem selenium transporters [31]. These effects collectively improve the transport factor (TF) and optimize source–sink distribution efficiency. Nevertheless, the optimal application dosage for such compound activators remains inadequately studied, representing a critical knowledge gap for their effective field implementation.

To validate these theoretical advantages, this study conducted field experiments in citrus orchards (cultivating ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ cultivars) in Yuxi City, Yunnan Province, systematically analyzing the following: (1) the regulatory effects of different application rates of compound activators on soil available selenium and soil properties; (2) the relationship between selenium enrichment and translocation factors in different organs of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’; and (3) the enhancement effects of selenium biofortification on the external and internal quality attributes of the fruits. Based on the experimental results, the influence of the activator on selenium uptake, fruit quality, and nutritional composition was comprehensively evaluated across these two citrus varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

The field experiment was carried out at the Citrus Research Park of Yunnan Dingcheng Agricultural Science and Technology Co., Ltd., located in Yuxi City, Yunnan Province, China (23°53′35″ N, 101°41′35″ E). The tested plant materials consisted of perennial plants of Citrus reticulata Blanco (‘Ponkan’) and Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck (‘Bing Tang Cheng’). Based on previous orthogonal experiments, the optimal formulation of the compound activator was determined as bioactive fulvic acid, seaweed acid, wood vinegar, and Phosphorus tailings in a ratio of 2.5:2:5:3. The soil selenium compound activator used in the study was formulated by blending wood vinegar (supplied by Yunnan Soil Fertilization and Pollution Remediation Engineering Center), biochemical fulvic acid and alginic acid (both provided by Wuzhoufeng Agricultural Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Yantai, China), and Phosphorus Tailings (obtained from Yunnan Yuntianhua Co., Ltd., Kunming, China) (Table 1). The content of critical heavy metals (such as cadmium, lead, mercury, arsenic, etc.) in the phosphorus tailings is well below the threshold limits set by both domestic and international regulations, including the “Soil Environmental Quality Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land (Trial)” (GB 15618-2018 [32]). Soil activator: Single activator 1 (Stanley Agricultural Group Co., Ltd., Linyi, China); soil activator: Single activator 2 (Anhui Lingwo Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hefei, China). These components primarily contain organic acids and phenolic compounds, fulvic acid, alginic acid, and calcium sulfate dihydrate. The baseline soil properties of the experimental site were as follows: pH 7.02, soil organic matter (SOM) 50.83 g/kg, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen 132.75 mg/kg, available phosphorus (AP) 162.17 mg/kg, available potassium 312.50 mg/kg, and total selenium 0.43 μg/g.

Table 1.

Composition of Phosphorus Tailings.

2.2. Experimental Design

Field experiments were subsequently conducted using a randomized block design with six treatments for each citrus variety: for ‘Ponkan’, treatments included a control without activators (WGCK), single activator 1 at 400 g/plant (WG1), single activator 2 at 400 g/plant (WG2), and compound activator at 200 (WG200), 400 (WG400), and 600 (WG600) g/plant; similarly for ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, with corresponding treatments CZCK, CZ1, CZ2, CZ200, CZ400, and CZ600. The experimental layout comprised 36 plots in total, with each ‘Ponkan’ plot containing approximately 3 plants (36 m2) and each ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ plot containing 2 plants (25 m2); all treatments were replicated three times and separated by buffer rows. Application method of activator: Four radial trenches (20–40 cm deep, 30–50 cm wide) were dug along the direction of horizontal root growth under the plant canopy projection. The activator was thoroughly mixed and evenly applied into the trenches before backfilling. sampling based on plant developmental stages: Soil and plant samples of ‘Ponkan’ were collected at four BBCH stages, 71–73, 77, 81, and 89, while those of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ were collected at three BBCH stages: 71–73, 77, and 81. Soil Sample Collection: Soil samples were collected from the root zone of each fruit tree at a depth of 0–20 cm. Stones and plant residues were removed. The collected soil was mixed, and approximately 1 kg of representative sample was obtained using the quartering method. The samples were air-dried in a shaded area, ground, passed through a 100-mesh nylon sieve, and stored in sealed bags for later use. Plant Sample Collection: Roots, stems, leaves, and fruits of mature ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ plants were collected separately. The root systems were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to remove surface soil. The roots, stems, leaves, and fruits were then placed in a 105 °C air-drying oven for 30 min to deactivate enzymes, followed by drying at 70 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The dried samples were pulverized using a grinding instrument, passed through a 60-mesh sieve, and stored in sealed bags for later use.

2.3. Test Items and Analytical Methods

The available selenium content in soil and the total selenium content in plant tissues were quantified using atomic fluorescence spectroscopy (AFS). Specifically, the soil available selenium (including water-soluble and exchangeable forms) was determined according to the T/HNNMIA 4—2023 [33] standard method “Determination of Available Selenium Content in Soil—AB-DTPA Extraction-Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry”. The detailed measurement steps for the samples are as follows: Accurately weigh 10.00 g (precise to 0.01 g) of the prepared soil sample into a dry and clean 150 mL conical flask. Precisely add 20.0 mL of AB-DTPA extraction solution (soil-to-liquid ratio of 1:2). Cap the flask and place it in a constant temperature oscillator at 25 °C, oscillating at 180 r/min for 2 h. The entire extraction process must be protected from light. Immediately after oscillation, filter the extraction solution through medium-speed quantitative filter paper into a dry and clean polyethylene test tube. Discard the initially turbid part of the filtrate and collect the clear filtrate, which is the test solution for soil available selenium. Due to potential interference from organic components and salts in the AB-DTPA extraction solution with subsequent determination, the extraction solution requires digestion treatment to convert selenium into its inorganic form. Precisely pipette a specific volume, 10.00 mL, of the aforementioned extraction filtrate into a 50 mL conical flask. Add 5 mL of high-purity nitric acid to the solution, cover with a watch glass, and heat on an electric hotplate at low temperature (approximately 120 °C) until nearly dry, ensuring it does not dry out completely. If the solution color remains dark, add an additional 1–2 mL of nitric acid and continue heating until the solution becomes clear or the color stabilizes. After cooling, add 5 mL of 6 mol/L hydrochloric acid solution, warm briefly to reduce hexavalent selenium to tetravalent selenium. After cooling again, quantitatively transfer the entire solution to a 25 mL colorimetric tube or volumetric flask, dilute to the mark with ultrapure water, mix thoroughly, and let it stand for clarification before analysis. Prepare reagent blank solutions simultaneously.

The total selenium content in various organs (roots, stems, leaves, and fruits) of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ was determined according to the Chinese National Standard GB 5009.93-2017 [34] “Determination of Selenium in Foods”. We employed a microwave digestion method for sample digestion. Specifically, 0.6 g (accurate to 0.001 g) of the solid sample was weighed and placed into a digestion tube. Then, 10 mL of nitric acid and 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide were added. The mixture was shaken thoroughly to ensure homogeneity. Digestion was carried out in a microwave digestion system using the following recommended program: Step 1: Ramp from room temperature to 120 °C within 6 min and hold for 1 min. Step 2: Further increase to 150 °C within 3 min and hold for 5 min. Step 3: Finally, increase to 200 °C within 5 min and hold for 10 min. After completion of the digestion and subsequent cooling, the digest was transferred to a conical flask. A few glass beads were added, and the solution was heated on an electric hotplate until nearly dry, ensuring it was not taken to complete dryness. Then, 5 mL of hydrochloric acid solution (6 mol/L) was added, and heating continued until the solution turned clear and colorless, accompanied by the appearance of white fumes. After cooling, the solution was transferred to a 10 mL volumetric flask. Then, 2.5 mL of potassium ferricyanide solution (100 g/L) was added, and the volume was made up to the mark with water. The solution was mixed thoroughly and was ready for measurement. A reagent blank test was conducted simultaneously. SOM was measured by potassium dichromate oxidation-spectrophotometry [35], and AP was analyzed colorimetrically. Soil pH was determined in a 1:25 (w/v) soil-to-0.01 M calcium chloride suspension.

Fruit quality assessments were conducted on the day of harvest: individual fruit weight was measured using an electronic balance. Fruit morphological and quality parameters were measured using standardized methods. The longitudinal diameter (L) was measured from the base to the apex using a ruler, and the transverse diameter (T) was determined at the upper third of the fruit with a digital caliper. The fruit shape index was calculated as the ratio of L to T. Determination of soluble solids content: Flesh tissues (10 g) from eight fruits were juiced using a domestic juice extractor. The juice was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was then dropped onto a handheld digital refractometer for measurement [36]. Determination of vitamin C content: The vitamin C content was measured according to the method described by Hipólito Hernández-Hernández Contreras-Calderón et al. [37]. Specifically, 5 g of citrus fruit juice was mixed with 15 mL of a 2% (w/v) oxalic acid solution and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. Then, 10 mL of the supernatant was titrated with a 0.1% (w/v) 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol solution until a persistent pink color appeared. The vitamin C content was calculated based on the titration volume of the 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol solution and expressed as milligrams per 100 g of fresh weight. Citric acid content was determined by indicator titration, and soluble sugar content was assessed using the anthrone-sulfuric acid method [38]. Peel-to-fruit ratio was calculated as the peel weight divided by the whole fruit weight. Edible rate was expressed as the flesh weight as a percentage of the whole fruit weight. Flesh content was determined as the flesh weight divided by the total weight of the peeled fruit.

2.4. Data Processing

2.4.1. Data Analysis

Data processing and preliminary statistical analysis, including calculation of means and standard deviations, were performed using Microsoft Excel 2021. Statistical analyses, such as analysis of variance (ANOVA), correlation analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and dimension reduction analysis, were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Multiple comparisons among groups were evaluated with Duncan’s test, and differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to reduce the dimensionality of three soil properties, four selenium forms in plant organs, and six quality indicators, with one principal component extracted for each category. The detailed procedure included the following: (1) data standardization; (2) establishing a correlation coefficient matrix to examine inter-variable relationships; (3) computing the covariance matrix; (4) calculating eigenvalues and eigenvectors; (5) determining the contribution rate and cumulative contribution rate of principal components; (6) selecting principal components. Based on the dimensionality reduction results, a structural equation model was constructed using IBM SPSS Amos 29 Graphics software, with parameters estimated through maximum likelihood estimation. The model was evaluated using multiple goodness-of-fit indices including χ2/df, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. Finally, bar charts were generated using Origin 2021, and Spearman correlation analysis was applied to create heatmaps visualizing relationships among soil properties, organ selenium content, and quality indicators.

2.4.2. Calculation Formula

- Standardization of Positive and Negative Indicators

Positive indicators were normalized as follows:

Negative indicators were normalized as follows:

In the formula, Uij and Vij, respectively, represent the converted positive and negative index values. Xji—denotes the original value of the jth indicator for the ith sample. Xminj represents the minimum value among the jth indicator data points, and Xmaxj represents the maximum value among the jth indicator data points.

Comprehensive Fruit Quality Score:

In the formula, S stands for the final score, Qn stands for the score of the nth factor, Tn stands for the variance contribution rate of the nth factor, and T stands for the cumulative variance contribution rate of the eigenvalue greater than 1.

Citrus Selenium Enrichment Coefficient (BCF):

In the formula, BCF represents the Bioconcentration Factor (also known as the bio-enrichment factor); “Selenium concentration in plant organs” refers to the selenium content in specific plant parts (roots, stems, leaves, and fruits); “Total selenium concentration in the soil” denotes the overall selenium content in the soil where the plants are cultivated. When BCF > 1, it indicates that the plant has elevated selenium concentrations in the specified organ to levels exceeding those in the soil, demonstrating significant selenium enrichment capability. When BCF < 1, it reflects a limited capacity of the plant to accumulate this element.

Translocation Factor (TF):

In the formula, TF represents the Translocation Factor; “Selenium concentration in plant organs” refers to the selenium content in specific above-ground parts (stems, leaves, and fruits); “Root selenium concentration” denotes the selenium content in the plant root system. If TF > 1, it indicates that the selenium concentration in the target organ exceeds that in the roots, demonstrating efficient translocation of selenium from the root system (as a transit hub) to the final sink organs (e.g., fruits).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Compound Activator on Soil Available Selenium and Physicochemical Properties

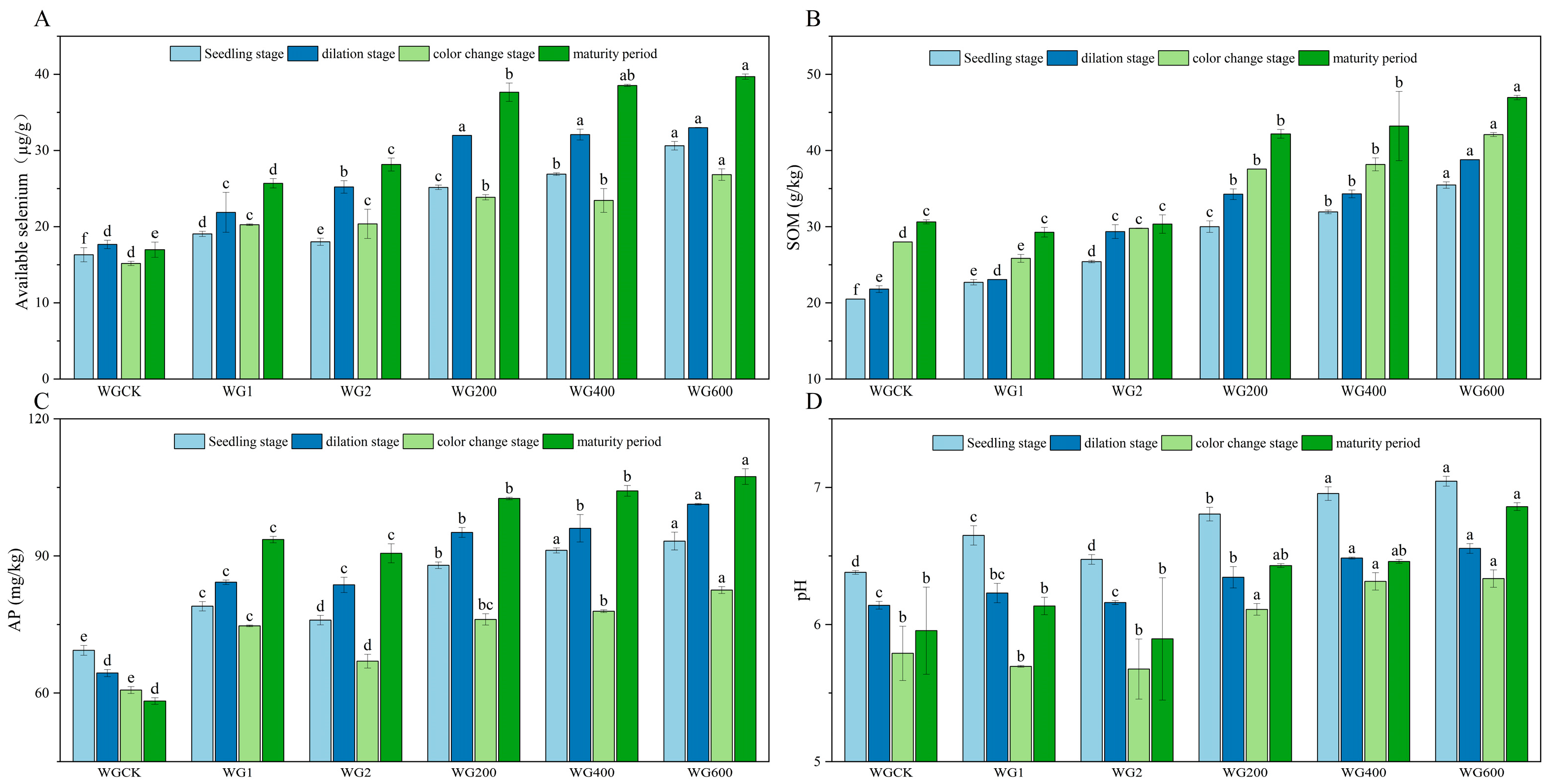

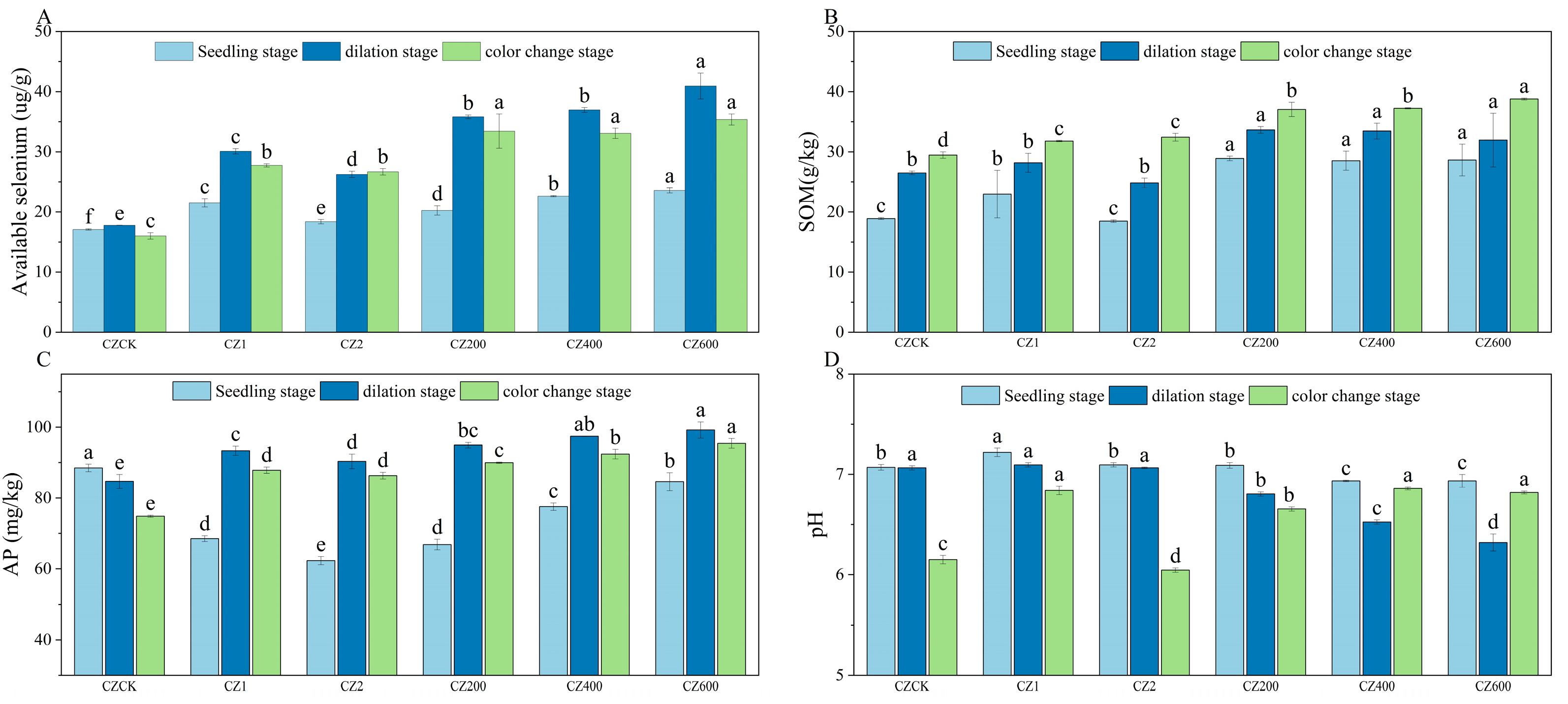

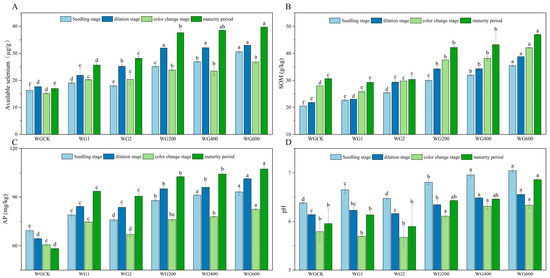

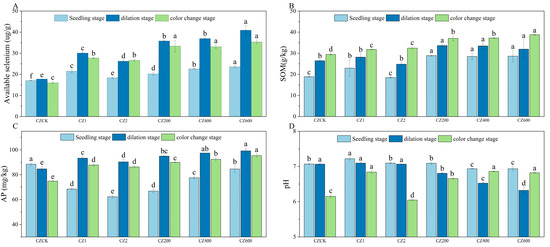

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, compared with the control (CK), the application of activators significantly enhanced soil available selenium content and improved soil physicochemical properties in both ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. All activator treatments resulted in a significant increase (p < 0.05) in soil available selenium across all growth stages for both citrus varieties. Furthermore, the compound activator demonstrated consistently superior performance compared to the individual activators (WG 1, WG 2, CZ 1, and CZ 2) throughout the entire growth cycle. Soil available selenium content increased sharply during the young fruit stage and peaked at maturity. Among all treatments, the application rate of 600 g per plant resulted in the most pronounced enhancement in available selenium. The activator also significantly elevated SOM content (p < 0.05) across all growth stages in both varieties. The compound activator consistently outperformed the single-activator treatments in promoting SOM accumulation, with the highest SOM levels observed at maturity. Furthermore, the 600 g/plant application rate led to significantly higher SOM content compared to the 400 g/plant treatment. Compared to the control (CK), the application of the activator significantly increased AP content across all growth stages, with the 600 g/plant treatment yielding the highest values. Furthermore, in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, the compound activator applied at 600 g/plant showed the most pronounced effect on AP content during the fruit expansion and color change stages. Regarding soil pH, the compound activator applied at 600 g/plant resulted in the highest pH values in ‘Ponkan’, significantly differing from both CK and single-activator treatments (400 g/plant). Overall, the compound activator, particularly at the 600 g/plant dosage—demonstrated the most consistent and significant improvements in soil available selenium, organic matter, and AP content (observed across all growth stages in ‘Ponkan’ and key stages in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’), while also effectively regulating soil pH. These results indicate its superior comprehensive potential for soil quality enhancement compared to single-component activators.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of soil available selenium, SOM, AP, and pH during the field trial in ‘Ponkan’ under different treatments. (A): Soil available selenium content across treatments in ‘Ponkan’; (B): SOM content across treatments; (C): AP content across treatments; (D): soil pH values across treatments. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of soil available selenium, SOM, AP, and pH in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ under different treatments. (A): Soil available selenium content across treatments in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’; (B): SOM content across treatments; (C): AP content across treatments; (D): soil pH values across treatments. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the p < 0.05 level.

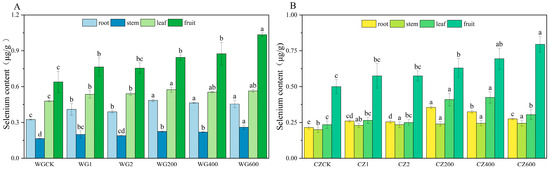

3.2. Total Selenium Content in Citrus Organs

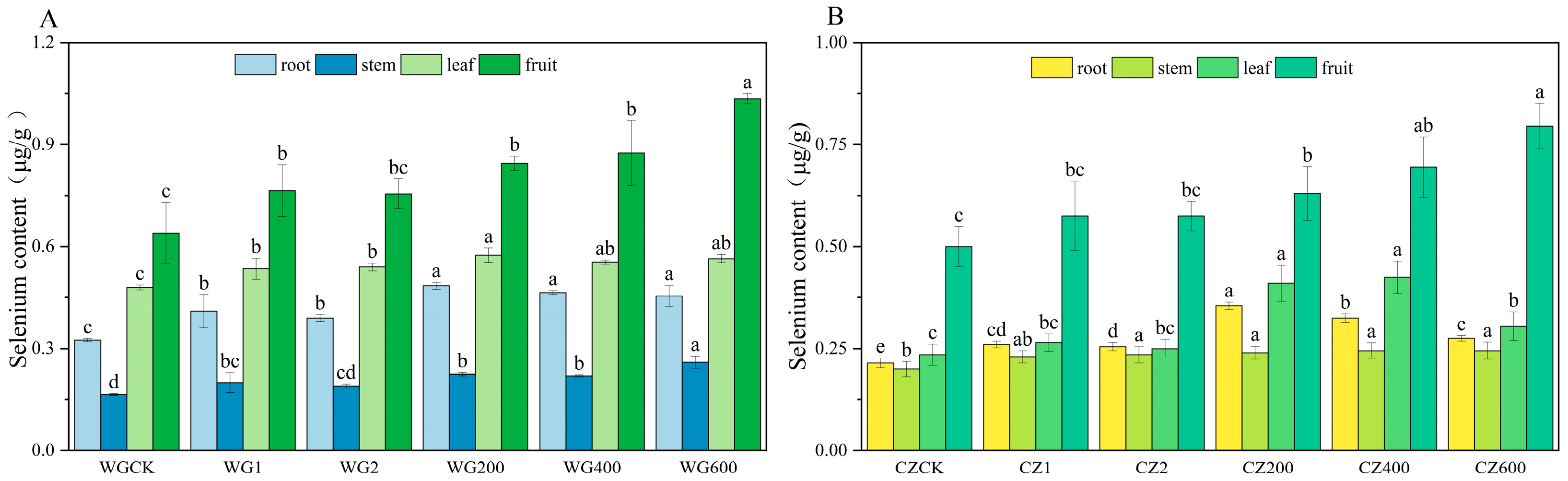

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of selenium in different organs of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ and ‘Ponkan’ citrus at maturity, revealing significant varietal differences and dose-dependent effects. In ‘Ponkan’, selenium content followed the order: fruit (1.035 μg/g) > leaves (0.575 μg/g) > roots (0.485 μg/g) > stems (0.26 μg/g), with significant differences (p < 0.05) between organs. In contrast, ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ accumulated the highest selenium content in fruits (0.795 μg/g), while no significant differences were observed among roots, stems, and leaves, indicating limited selenium translocation from vegetative organs to fruits. Figure 3 demonstrates that the compound activator significantly enhanced selenium content in the fruits of ‘Ponkan’ compared to the CK and both single-activator treatments (p < 0.05), with significant differences also observed in roots and leaves. Among all application rates, 600 g per plant yielded the highest selenium accumulation. Similarly, in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, the compound activator significantly increased selenium concentrations across all organs relative to the CK. The measured ranges were 0.14–0.325 μg/g in roots, 0.04–0.245 μg/g in stems, 0.175–0.425 μg/g in leaves, and 0.195–0.795 μg/g in fruits. These results indicate that the application of the compound activator at 600 g per plant most effectively promoted selenium accumulation in the edible fruits of both ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’.

Figure 3.

Selenium Content in Roots, Stems, Leaves, and Fruits of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. (A): Selenium content in roots, stems, leaves, and fruits of ‘Ponkan’; (B): selenium content in roots, stems, leaves, and fruits of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the p < 0.05 level.

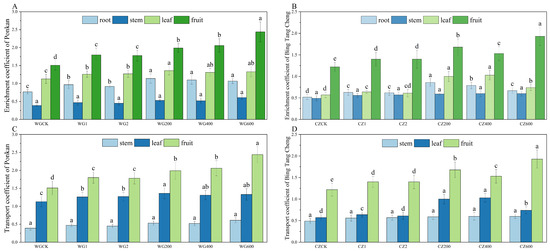

3.3. Citrus Enrichment and Transport Characteristics

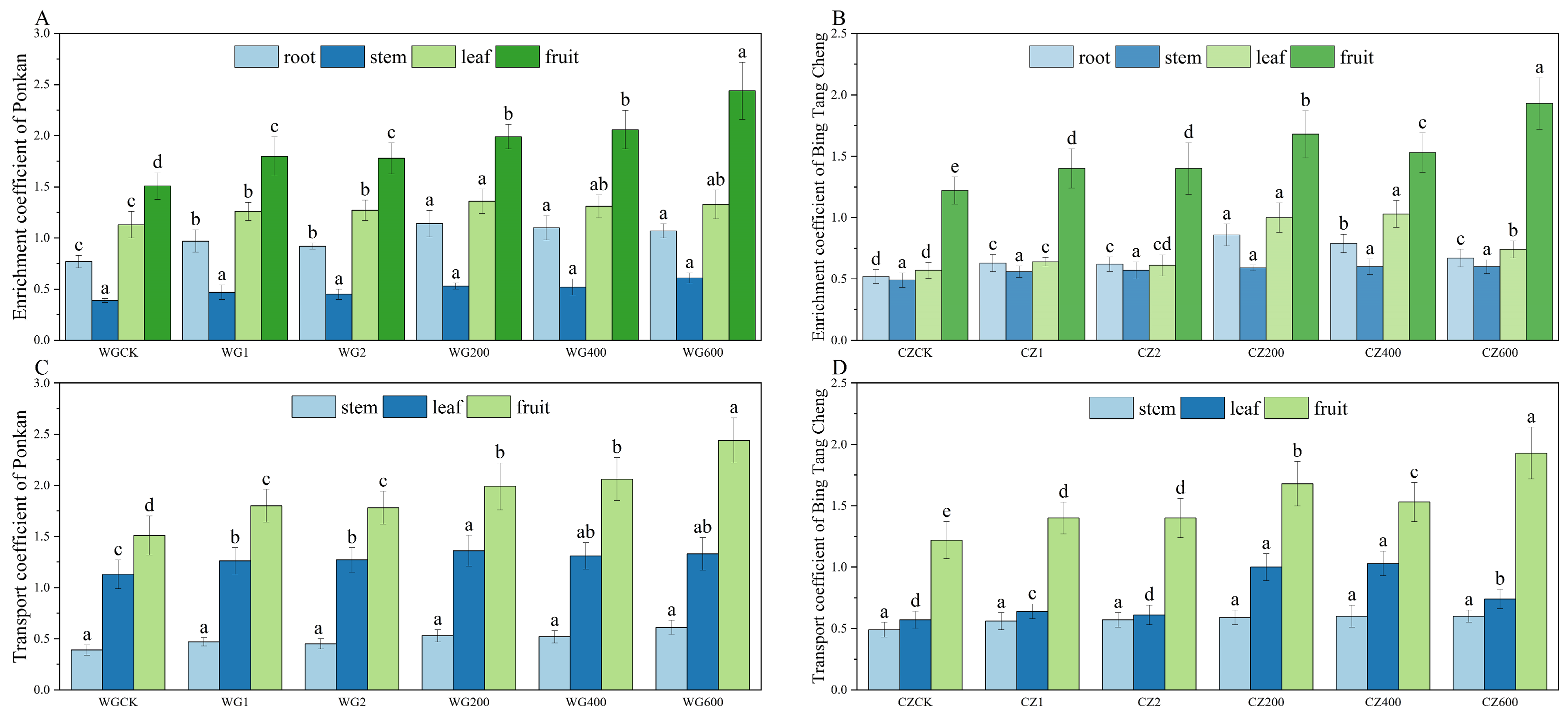

Figure 4 illustrates the characteristics of selenium accumulation and translocation in different organs of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. Under the treatment with the compound activator at 600 g/plant, the bioconcentration factor (BCF) of roots, stems, leaves, and fruits all significantly exceeded 1 (p < 0.05), with the fruit exhibiting the highest BCF value (2.44), demonstrating its superior capacity for selenium uptake from soil. These results confirm that the compound activator effectively mobilizes soil selenium and promotes its accumulation in various citrus organs. Compared to the CK and the two single activators, the compound activator significantly enhanced the bioconcentration factors (BCFs) in roots, leaves, and fruits of ‘Ponkan’ (exhibiting the highest BCF value (2.44), demonstrating its superior capacity for selenium uptake from soil. These results confirm that the compound activator effectively mobilizes soil selenium and promotes its accumulation in various citrus organs. Compared to the CK and the two single activators, the compound activator significantly enhanced the bioconcentration factors (BCFs) in roots, leaves, and fruits of ‘Ponkan’ (p < 0.05). The 600 g/plant dosage demonstrated the most pronounced effect, yielding BCFs significantly (p < 0.05). The 600 g/plant dosage demonstrated the most pronounced effect, yielding BCFs significantly higher than those in the 200 and 400 g/plant treatment groups (p < 0.05). In ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, BCFs greater than 1 were observed only in leaves (under the 200 and 400 g/plant treatments) and in fruits (under the 600 g/plant treatment), with the highest fruit BCF also achieved at the 600 g/plant application rate. The compound activator significantly enhanced the bioconcentration factor (BCF) in both leaves and fruits of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ compared to the CK and single-activator treatments (p < 0.05). In ‘Ponkan’, the compound activator markedly improved leaf-to-fruit translocation efficiency (TF leaf-fruit > 1). The strong root sequestration capacity (BCF > 1) ensured efficient selenium uptake, which, coupled with effective phloem-mediated leaf-to-fruit transport, collectively promoted substantial selenium accumulation in fruits. In contrast, ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ exhibited limited leaf-to-fruit translocation (TF leaf-fruit < 1), leading to considerable selenium retention in stems and leaves. This phenomenon was attributable to both restricted root absorption (BCF < 1) and a bottleneck in leaf-to-fruit selenium translocation, which together constrained the final selenium enrichment in fruits.

Figure 4.

Organ-specific selenium BCF and inter-organ TF in ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. (A): Selenium BCF in roots, stems, leaves, and fruits of ‘Ponkan’; (B): selenium BCF in roots, stems, leaves, and fruits of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’; (C): selenium TF in stems, leaves, and fruits of ‘Ponkan’; (D): selenium TF in stems, leaves, and fruits of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the p < 0.05 level.

3.4. Citrus Fruit Quality Analysis

The appearance and internal quality indicators of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. Compared to the control (CK), the fruit shape index of ‘Ponkan’ (1.23) exhibited an oblate shape. The compound activator (WG600) treatment significantly increased the fruit shape index to 1.34 (p < 0.05), which aligns better with the standard morphology of high-quality ‘Ponkan’ fruits. However, no significant differences were observed between the WG 600 treatment and either the WG400 treatment or the two individual activator treatments. Notably, no significant differences were detected between WG 600 and WG 400, or between the two single activators. Similarly, in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, the compound activator also significantly improved the fruit shape, resulting in a form more closely approximating a sphere. The compound activator significantly improved multiple fruit quality parameters in both varieties. In ‘Ponkan’, the WG 600 treatment significantly reduced peel thickness, decreasing the peel-to-fruit ratio from 20.59% to 17.61% (p < 0.05) and concurrently increasing the edible ratio by 3%. Similarly, in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, the CZ 600 treatment significantly enhanced flesh content and reduced the peel-to-fruit ratio compared to the CK. Furthermore, the compound activator significantly increased the single-fruit weight in both varieties. In summary, the application of 600 g per plant effectively promoted fruit growth and improved commercial quality attributes in both ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’.

Table 2.

Appearance quality of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ fruits. Lowercase letters in the table indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the p < 0.05 level.

Table 3.

Internal quality of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ fruits. Lowercase letters in the table indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the p < 0.05 level.

According to Table 3, compared to the control (CK), the application of the compound activator (600 g per plant) significantly increased (p < 0.05) the soluble solids, citric acid, solid–acid ratio, selenium content, and yield of ‘Ponkan’ by 35.8%, 20.3%, 77.8%, 223.3%, and 30.11%, respectively. Furthermore, the soluble solids, vitamin C, and citric acid reached their maximum values, showing significant differences compared to the application of the compound activator at 400 g per plant. Notably, it reduced the total soluble sugar content by 23.1%, while no significant effect was observed on vitamin C. Meanwhile, the application significantly increased the soluble solids, vitamin C, total soluble sugar, solid–acid ratio, selenium content, and yield of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ by 46.1%, 45.3%, 73.4%, 156.6%, 69.7%, and 53.43%, respectively. The soluble solids, vitamin C, total soluble sugar, and selenium content all reached their highest levels, demonstrating significant differences compared to the application of the compound activator at 400 g per plant. In contrast, citric acid content was significantly reduced by 42.2%. When compared to single-activator treatments, the compound activator led to a significant increase in soluble solids, vitamin C, and the solid-to-acid ratio in ‘Ponkan’, while also reducing the total soluble sugar content. In ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, the compound activator significantly increased the contents of soluble solids, vitamin C, total soluble sugars, solid-to-acid ratio, and selenium, while reducing the citric acid content. Overall, the compound activator improved the intrinsic quality of citrus fruits more effectively than the single-component activators. These results demonstrate that the application of the compound activator at 600 g/plant (WG 600) simultaneously achieved desirable appearance traits (such as thinner peel and larger fruit size) and substantial intrinsic selenium enrichment (with selenium content increased by 223%), representing the optimal dosage for integrated fruit quality enhancement.

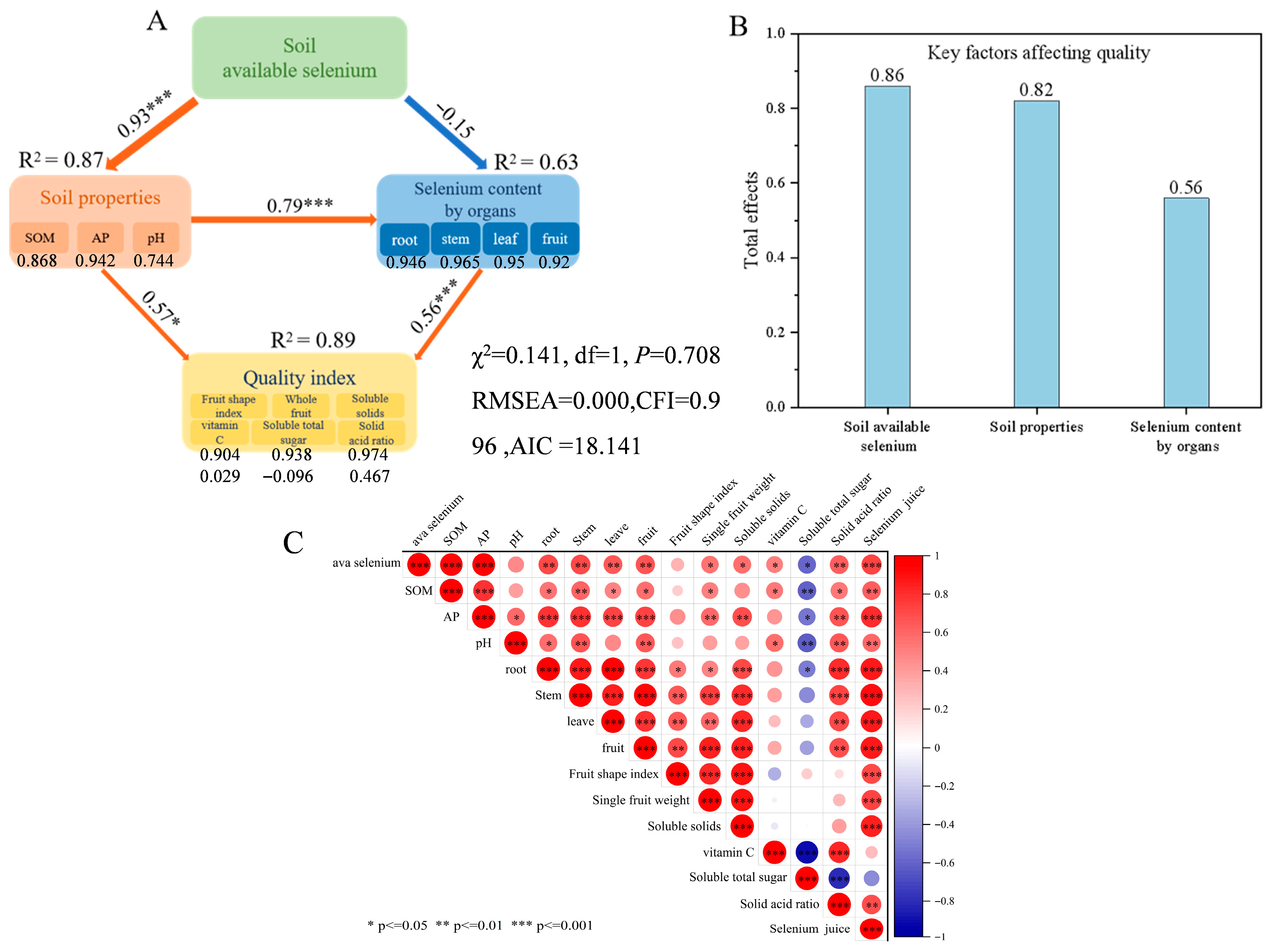

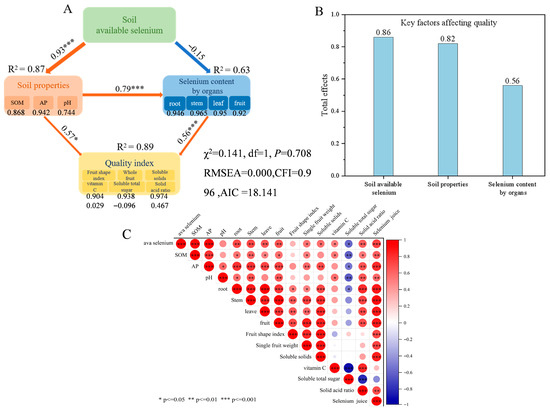

3.5. Correlation Between Available Selenium and Factors Influencing Citrus Quality

The structural equation model exhibited a good fit to the data, with χ2/DF = 0.141 (p = 0.708 > 0.05), RMSEA = 0.000, and CFI = 0.996 (Figure 5A), meeting standard criteria for model acceptability. These results support the hypothesized pathway “soil available selenium–selenium in citrus organs–fruit quality” as consistent with observed data. The standardized path coefficient from soil available selenium to soil properties (SOM, AP, pH) was 0.93 (p < 0.001) (R2 = 0.87), indicating that soil available selenium significantly and positively drives changes in soil properties, with the model explaining 87% of the variation in available selenium. According to the correlation heatmap (Figure 5C), SOM and AP showed highly significant positive correlations (p < 0.001) with available selenium among soil properties. However, the effect of soil available selenium on selenium content in various citrus organs was negative but weak, with a small coefficient (–0.15), and the model explained 63% of the variation. A path coefficient of 0.79 (p < 0.001) demonstrated that soil physicochemical properties positively influenced selenium uptake by citrus organs. Based on Figure 5C, AP exhibited highly significant positive correlations with selenium content in roots, stems, leaves, and fruits of citrus. The path coefficient of 0.56 (p < 0.001) indicated that selenium content in citrus organs had a highly significant positive regulatory effect on quality indicators, suggesting that increased selenium content in organs can enhance citrus quality. Correlation analysis (Figure 5C) further revealed that selenium content in each organ was significantly positively correlated with soluble solids and the solid-to-acid ratio, showed no significant correlation with vitamin C, and was significantly negatively correlated with total soluble sugar content. Soil available selenium plays a pivotal role in the “soil properties–fruit quality” pathway (total effect value: 0.86), demonstrating its central importance in enhancing citrus quality through selenium augmentation.

Figure 5.

Relationships among soil properties, organ-specific selenium content, fruit quality indicators, and soil available selenium. (A) Structural equation model (SEM) illustrating the pathways linking soil available selenium, soil properties, selenium content in plant organs, and fruit quality indices. The model was constructed using the first principal component derived from principal component analysis (PCA) of soil properties, organ selenium levels, and quality parameters. Arrow width reflects the strength of the relationship; red and blue arrows denote significant positive and negative paths, respectively (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001). Numbers adjacent to arrows represent standardized path coefficients, and R2 indicates the proportion of variance explained. (B) Total effects of soil available selenium, soil properties, and organ selenium content on fruit quality. (C) Correlation heatmap depicting the relationships among soil available selenium, soil properties, selenium contents in various plant organs, and external and internal quality attributes. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the associations between soil available selenium, soil properties, selenium contents in plant organs, and quality indicators. Correlation coefficients, ranging from negative to positive, are represented by a color gradient from blue to red. Parameter definitions in the figure are as follows: Root: selenium concentration in roots; Stem: selenium concentration in stems; Leaf: selenium concentration in leaves; Fruit: selenium concentration in fruits. Significance levels are denoted by asterisks (* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

Total selenium in soil defines its selenium supply capacity, while available selenium content is a critical factor governing selenium mobility and crop uptake. The level of available selenium directly influences whether selenium deficiency or excess occurs in agricultural systems. In this study, the compound activator significantly increased the available selenium content in soils under both citrus varieties. This finding aligns with previous reports showing that organic soil conditioners enhance available selenium in selenium-enriched wheat and Chinese cabbage, enabling the latter to meet selenium-rich standards [39]. Organic acids enhance selenium availability by degrading clay minerals and dissociating selenium–organic complexes through chelation, thereby releasing water-soluble and exchangeable selenium fractions and increasing the content of available selenium [40]. In this study, bioactive fulvic acid served as the primary source of such organic acids. It facilitates the formation of soluble selenium–fulvate complexes, which reduces the adsorption and fixation of selenium in the soil matrix and thereby elevates the level of plant-available selenium [41]. Meanwhile, the activator also enhances the soil SOM content, likely because the applied compound activator (containing approximately 30% SOM in its bioactive fulvic acid and seaweed acid components) serves as a direct exogenous input that elevates soil SOM levels. The activator also significantly increased AP content. Given the structural and uptake pathway similarities between phosphorus and selenium in plants, elevated AP levels may further promote selenium absorption [42]. The possible reason is that phosphorus tailings are rich in alkaline substances such as calcium (CaO) and magnesium (MgO) [43], which can effectively neutralize soil acidity and increase the pH of the rhizosphere microzone [44]. This is consistent with the findings that organic amendments (such as vermicompost) improve melon fruit quality by enhancing soil properties and microbial communities [45].

The results revealed significant differences in selenium accumulation and translocation between ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. These varietal disparities may be attributed to differences in root system architecture, which influence the soil–root contact area and consequently affect selenium absorption efficiency [46]. Another possible explanation is that the observed differences may be related to variations in root exudate composition, particularly the types and concentrations of low-molecular-weight organic acids (e.g., citric acid, malic acid) [47]. Additionally, the compound activator might enhance selenium translocation from roots to fruits by potentially improving rhizosphere nutrient availability (thus promoting root growth) or modulating the levels of endogenous hormones such as auxins and cytokinins [48]. The chemical form of selenium also influences its mobility within plants; for instance, selenate is generally more readily transported than selenite. Key transporters including SULTR3;5 and SULTR2;1 have been shown to mediate the transport of selenate from roots to the xylem [49]. Additionally, rhizosphere microorganisms play a regulatory role: certain fungi can enhance selenium retention in roots and limit its translocation to shoots [50], highlighting the complex interplay between microbial communities and selenium allocation in plants.

The compound activator (particularly at 600 mg/plant) demonstrated significant effects in improving both the external appearance and internal quality of ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ sweet oranges, which aligns with findings from multiple studies indicating that external interventions can enhance fruit quality [51]. In terms of external attributes, WG 600 promoted a fruit shape in ‘Ponkan’ that more closely conformed to the ideal morphology for high-quality produce, underscoring the efficacy of the compound activator [52]. The compound activator (WG 600) notably improved the fruit shape of ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, promoting a more spherical morphology, while significantly reducing peel thickness and peel-to-fruit ratio in ‘Ponkan’, thereby increasing edible yield by 3% [53]. In addition, the treatment significantly increased the average fruit weight in both citrus varieties. These results demonstrate that key appearance traits—including fruit shape, peel thickness, and fruit weight—can be effectively optimized through appropriate agronomic strategies, ultimately enhancing the commercial value of the produce [54]. Fruit quality indicators (such as sugars, acids, and vitamin C) typically change significantly with maturity [55]. In this study, all samples were uniformly harvested at the commercial maturity stage, so the observed differences between treatments are primarily attributed to the effects of the activator treatment. Regarding internal quality, soil application of the compound activator significantly increased the levels of soluble solids (TSS), citric acid, solid-to-acid ratio (TSS/TA), and selenium in citrus fruits. This effect was most pronounced in ‘Ponkan’ treated with WG 600 and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’ receiving CZ 600, consistent with previous observations in pomegranates [56], tomatoes [57], cucumbers [58], and Chinese cabbage. Meanwhile, we also observed that the WG 600 treatment significantly reduced the soluble sugar content in ‘Ponkan’. This reduction might be attributed to WG 600 accelerating the conversion of simple sugars such as fructose and glucose into secondary metabolites, thereby leading to a decrease in their detectable levels as “total soluble sugar”. (For instance, in kiwifruit during ripening, ethylene treatment also induces changes in primary and secondary metabolites, including alterations in sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose), organic acids, amino acids, fatty acids, and antioxidant compounds.) [59]. During the treatment process, the formed selenium nanoparticles or selenium-containing compounds may complex with sugar molecules. Such complexes could alter the conformation or reactivity of the sugar molecules, thereby inhibiting or diminishing their dehydration reaction with concentrated sulfuric acid and/or affecting their condensation reaction with anthrone [60]. As a result, the actual sugar content may not be fully detected, leading to a measured apparent value of “total soluble sugar” that is lower than the true value. Concurrently, vitamin C content was significantly elevated in ‘Bing Tang Cheng’, aligning with earlier studies [61,62]. The application of selenium has been documented to significantly enhance the quality of various agricultural products, including apples [63] and tomatoes [64]. In the present study, the compound activator proved more effective than single-component activators in improving the internal quality of citrus fruits. Specifically, the WG 600 treatment not only optimized fruit appearance producing larger fruits with thinner peel, but also substantially enhanced internal quality, most notably through selenium enrichment, which increased by 223%. These improvements are of particular relevance in the context of growing consumer demand for nutritious and health-promoting foods [65]. This is consistent with previous studies on increasing strawberry selenium content and quality through foliar selenium fertilizer application [66], improving apple quality by enhancing soil fertility via reduced nitrogen application combined with organic fertilizers [67], and the systematic improvement of citrus fruit quality, leaf physiology, and soil fertility through field inoculation of AMF [68]. In conclusion, the application of 600 g per plant of the compound activator (WG 600) represents the optimal dosage for enhancing fruit quality in both ‘Ponkan’ and ‘Bing Tang Cheng’. This treatment simultaneously improved external fruit attributes and significantly increased selenium content. Such comprehensive improvements are of considerable importance for the sustainable development of the citrus industry, as they help enhance both the market competitiveness and nutritional value of the fruit [69].

Soil properties are key factors regulating the availability of selenium in soil. The structural equation model indicated that soil SOM, AP, and pH collectively explained 87% of the variation in soil available selenium. Both SOM and AP showed a significant positive correlation with available selenium (p < 0.001). These relationships can be attributed to several mechanisms: SOM influences selenium mobility through chelation and by stimulating microbial activity; pH modulates selenium bioavailability by altering its speciation and adsorption behavior [70]; the relationship between “selenium content” and “quality index” arises through a mediation effect, where “soil properties” influence “selenium content,” thereby explaining 89% of the variation in quality. Selenium biofortification has been demonstrated to significantly improve tomato fruit quality and enhance its nutritional value [57]. In the present study, the total effect value of soil available selenium on citrus quality was 0.86, indicating that soil available selenium improves fruit quality by modifying the soil environment and promoting the conversion of organic selenium into quality-related components. This mechanistic understanding is further supported by research in tea cultivation, where the inoculation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens combined with sodium selenite application significantly promoted selenium uptake and growth of tea seedlings. This approach was shown to enhance the quality and selenium content of spring tea by modulating the rhizosphere bacterial community [71]. In this study, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to systematically elucidate the interrelationships and interactions among soil properties, soil available selenium, selenium accumulation in citrus organs, and final fruit quality. The findings provide a valuable theoretical basis for formulating effective selenium biofortification strategies and producing high-quality, selenium-enriched citrus.

5. Conclusions

Studies have demonstrated that the application of an organic–inorganic compound activator (comprising biochemical fulvic acid, alginate, phosphorus slag, and wood vinegar) promotes selenium accumulation in citrus. An application rate of 600 g per plant proved optimal, enhancing soil available selenium, SOM, and AP content, while improving selenium absorption and translocation in citrus. This treatment also increased fruit selenium concentration and optimized key quality indices such as fruit shape, single-fruit weight, sugar–acid composition, and solid–acid ratio. The recommended dosage provides a feasible agronomic practice for producing selenium-enriched citrus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z.; methodology, Z.L.; software, X.Z.; validation, N.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, Y.W.; resources, L.B.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, L.G.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, N.Z.; funding acquisition, N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Innovation guidance and cultivation plan of science and technology enterprises (Nos. 202404BI090011).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Naiming Zhang from Yunnan Agricultural University for experimental design guidance. We also thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their great support.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhizong Liu was employed by the company Yunnan Hanzhe Science & Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dai, H.; Wei, S.; Twardowska, I. Biofortification of Soybean (Glycine max L.) with Se and Zn, and Enhancing Its Physiological Functions by Spiking These Elements to Soil during Flowering Phase. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 139648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, R.; Siyame, E.W.P.; Young, S.D.; Chilimba, A.D.C.; Joy, E.J.M.; Black, C.R.; Ander, E.L.; Watts, M.J.; Chilima, B.; Gondwe, J.; et al. Soil-Type Influences Human Selenium Status and Underlies Widespread Selenium Deficiency Risks in Malawi. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, J.E. Risks and Benefits in Agricultural Uses of Selenium. Environ. Geochem. Health 1992, 14, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, Q.T.; Cui, Z.; Huang, J.; Tran, T.A.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Zhou, F.; Wang, M.; Yu, D.; Liang, D. Selenium Distribution in the Chinese Environment and Its Relationship with Human Health: A Review. Environ. Int. 2018, 112, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, M.L.; Durán, P.; Acuña, J.; Cartes, P.; Demanet, R.; Gianfreda, L. Improving Selenium Status in Plant Nutrition and Quality. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2015, 15, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, G.H.; van Rotterdam, A.M.D.; Bussink, D.W.; Bindraban, P.S. Selenium Fertilization Strategies for Bio-Fortification of Food: An Agro-Ecosystem Approach. Plant Soil 2016, 404, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Tejoprakash, N.; Reddy, M.S. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Ameliorate Selenium Stress and Increase Antioxidant Potential of Zea mays in Seleniferous Soil. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 3392–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, W.; Guo, A.; Qi, Z.; Chen, J.; Huang, T.; Yang, Z.; Gao, Z.; Sun, M.; Wang, J. Combined Foliar and Soil Selenium Fertilizer Increased the Grain Yield, Quality, Total Se, and Organic Se Content in Naked Oats. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 100, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, D.; Peng, Q.; Cui, Z.; Huang, J.; Lin, Z. Interaction between Selenium and Soil Organic Matter and Its Impact on Soil Selenium Bioavailability: A Review. Geoderma 2017, 295, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimahesvari, D.S.; Harish, S.; Karthikeyan, G.; Kannan, M.; Kumar, K.K. Advancements in dsRNA-Based Approaches: A Comprehensive Review on Potent Strategies for Plant Disease Management. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Liu, K.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, X. Difference of Selenium Uptake and Distribution in the Plant and Selenium Form in the Grains of Rice with Foliar Spray of Selenite or Selenate at Different Stages. Field Crops Res. 2017, 211, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, L.H.E.; Vriens, B.; Jones, G.D.; Schneider, L.S.; Pilon-Smits, E.; Bañuelos, G.S. Selenium Cycling across Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Interfaces: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4199–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabos, M.B.; Goldberg, S.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Modeling Selenium (IV and VI) Adsorption Envelopes in Selected Tropical Soils Using the Constant Capacitance Model. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 2197–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.P.; Johnsson, L. The Association between Selenium and Humic Substances in Forested Ecosystems—Laboratory Evidence. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1994, 8, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasekara, H.M.I.P.; Rajapakshe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Papelis, C. Microbial Co-Reduction of Selenate and Selenite in Zeolite-Packed Columns in the Presence of Sulfate and Nitrate: Effects on Removal Efficiency and Transformation of Microbial Community Structure. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, J.F.; Basu, P.; Santini, J.M.; Oremland, R.S. Arsenic and Selenium in Microbial Metabolism*. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Shrift, A. Selenium: Toxicity and Tolerance in Higher Plants. Biol. Rev. 1982, 57, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trippe, R.C.; Pilon-Smits, E.A.H. Selenium Transport and Metabolism in Plants: Phytoremediation and Biofortification Implications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Tullo, P.; Pannier, F.; Thiry, Y.; Le Hécho, I.; Bueno, M. Field Study of Time-Dependent Selenium Partitioning in Soils Using Isotopically Enriched Stable Selenite Tracer. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 562, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.J. Selenium Accumulation by Plants. Ann. Bot. 2016, 117, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyrzynska, K.; Sentkowska, A. Selenium in Plant Foods: Speciation Analysis, Bioavailability, and Factors Affecting Composition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1340–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangjaidee, P.; Swedlund, P.; Xiang, J.; Yin, H.; Quek, S.Y. Selenium-Enriched Plant Foods: Selenium Accumulation, Speciation, and Health Functionality. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 962312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wang, M.; Zhou, F.; Zhai, H.; Qi, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Ma, Y.; Huang, J.; et al. Selenium Bioavailability in Soil-Wheat System and Its Dominant Influential Factors: A Field Study in Shaanxi Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 144664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Tang, Z.; Zeng, R.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Ei, H.H.; Ye, X.; Jia, X.; Zhu, J. Accumulation, Mobilization, and Transformation of Selenium in Rice Grain Provided with Foliar Sodium Selenite. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2892–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, V.; Arcioni, A.; Filippini, P.; Pifferi, P.G. Foliar Application of Selenite and Selenate to Potato (Solanum tuberosum): Effect of a Ligand Agent on Selenium Content of Tubers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 4749–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Wu, C.; Zhang, H.; Cao, L.; Wei, T.; Guo, J. Biochar-Induced Changes in Soil Microbial Affect Species of Antimony in Contaminated Soils. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Khan, W.-D.; Hamid, Y.; Farooq, M.A.; Naeem, M.A.; Nadeem, F. Interaction of Pristine and Mineral Engineered Biochar with Microbial Community in Attenuating the Heavy Metals Toxicity: A Review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 175, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Pascual, A.; Rodriguez, L.C.; Han, X.; Casas-Ruiz, J.P.; Ferriol-Ciurana, J.; Donhauser, J.; Jordaan, K.; Allison, S.D.; Frossard, A.; Priemé, A.; et al. Soil Functions Are Shaped by Aridity through Soil Properties and the Microbial Community Structure. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 213, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zheng, Y.-J.; Wu, D.-T.; Du, X.; Gao, H.; Ayyash, M.; Zeng, D.-G.; Li, H.-B.; Liu, H.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y. Quality Evaluation of Citrus Varieties Based on Phytochemical Profiles and Nutritional Properties. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1165841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, B.; Qiu, R. Selenium-Induced Enhancement in Growth and Rhizosphere Soil Methane Oxidation of Prickly Pear. Plants 2024, 13, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estarriaga-Navarro, S.; Goicoechea, N.; Plano, D.; Sanmartín, C. Selenium Biofortification: Integrating One Health and Sustainability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 15618-2018; Soil Environmental Quality—Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land (Trial). Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- T/HNNMIA 4—2023; Determination of Available Arsenic Content in Soil—AB-DTPA Extraction-Atomic Fluorescence Spectrophotometry. Henan Nonferrous Metals Industry Association: Zhengzhou, China, 2023.

- GB 5009.93-2017; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Selenium in Foods. State Food and Drug Administration, National Health and Family Planning Commission: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Luo, J.; Huang, F.; Wang, P.; Xiao, R. Cd and Pb Immobilisation with Iron Oxide/Lignin Composite and the Bacterial Community Response in Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A. Pheno-Physiological Revelation of Grapes Germplasm Grown in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2011, 13, 791–795. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Hernández, H.; Quiterio-Gutiérrez, T.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Ortega-Ortiz, H.; Hernández-Fuentes, A.D.; Cabrera de la Fuente, M.; Valdés-Reyna, J.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Impact of Selenium and Copper Nanoparticles on Yield, Antioxidant System, and Fruit Quality of Tomato Plants. Plants 2019, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Dinh, Q.T.; Anh Thu, T.T.; Zhou, F.; Yang, W.; Wang, M.; Song, W.; Liang, D. Effect of Selenium-Enriched Organic Material Amendment on Selenium Fraction Transformation and Bioavailability in Soil. Chemosphere 2018, 199, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xing, G.; Tang, S.; Pang, Y.; Yi, Q.; Huang, Q.; Huang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, P.; Fu, H. Improving Soil Selenium Availability as a Strategy to Promote Selenium Uptake by High-Se Rice Cultivar. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 163, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, Q.T.; Li, Z.; Tran, T.A.T.; Wang, D.; Liang, D. Role of Organic Acids on the Bioavailability of Selenium in Soil: A Review. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, J. The Transformation and Migration of Selenium in Soil under Different Eh Conditions. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 2935–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Du, C. Leaching of Phosphorus from Phosphate Tailings and Extraction of Calcium Phosphates: Toward Comprehensive Utilization of Tailing Resources. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Q.; Wu, S.; Southam, G.; Robertson, L.; You, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Saha, N.; Webb, R.; Wykes, J.; et al. Acidophilic Iron- and Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria, Acidithiobacillus Ferrooxidans, Drives Alkaline pH Neutralization and Mineral Weathering in Fe Ore Tailings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 8020–8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Yu, R.; Guo, S.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Du, H.; Liang, J.; Zhang, X. Effect of Vermicompost Application on the Soil Microbial Community Structure and Fruit Quality in Melon (Cucumis melo). Agronomy 2024, 14, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgonà, A.; Cacco, G. Linking the Physiological Parameters of Nitrate Uptake with Root Morphology and Topology in Wheat (Triticum durum) and Citrus (Citrus volkameriana) Rootstock. Can. J. Bot. 2002, 80, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngullie, E.; Singh, A.K.; Sema, A.; Srivastava, A.K. Citrus Growth and Rhizosphere Properties. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2015, 46, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ling, L.; Peng, L.; Chun, C. Differences in Fruit Quality between Jinqiu Shatangju Tangerine (Citrus reticulata Jinqiu Shatangju) Grafted on Two Types of Rootstocks and the Relationship with Absorption, Distribution, and Utilization of Nitrogen. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; Gao, H.; Qiu, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, P.; Peng, C.; Jiao, Y.; et al. Long-Term Fertilizer Application Induces Changes in Carbon Storage and Distribution, and the Consequent Color of Black Soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, S.; Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Cheng, S.; Cheng, H. Molecular Mechanism of Exogenous Selenium Affecting the Nutritional Quality, Species and Content of Organic Selenium in Mustard. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Awasthi, M.K.; Xing, W.; Liu, R.; Bao, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, F. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Increase the Bioavailability and Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Uptake of Selenium in Soil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 150, 112383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, L.; Shani, M.Y.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Aziz, R.; Abbas, S.M.; Shahzad, B.A.; Hassannejad, S.; Mastinu, A.; Rahimi, M. Practical Implications of PGRs in Improving Fruit Juice Quality of Citrus reticulate. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 72, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.D.T.; Chaliha, M.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Netzel, M.E. Nutritional Characteristics and Antimicrobial Activity of Australian Grown Feijoa (Acca sellowiana). Foods 2019, 8, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jue, D.; Sang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Q.; Tang, J. Determination of the Effects of Pre-Harvest Bagging Treatment on Kiwifruit Appearance and Quality via Transcriptome and Metabolome Analyses. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.; Hussain, S.B.; Anjum, M.A.; Naseer, M.; Ahmad, R.; Ziogas, V. Effects of Harvest Time on the Fruit Quality of Kinnow and Feutrell’s Early Mandarins (Citrus reticulata blanco). Agronomy 2023, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Daneshvar Hakimi Meybodi, N.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Foliar Application of Selenium and Nano-Selenium Affects Pomegranate (Punica granatum Cv. Malase Saveh) Fruit Yield and Quality. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 124, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, J.; Cui, J.; Lin, A. Effects of Selenium Fertilizer Application and Tomato Varieties on Tomato Fruit Quality: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Tian, J.; Yan, X. Effects of Mineralization Degree of Irrigation Water on Yield, Fruit Quality, and Soil Microbial and Enzyme Activities of Cucumbers in Greenhouse Drip Irrigation. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.R.; Baek, M.W.; Cheol, L.H.; Jeong, C.S.; Tilahun, S. Changes in Metabolites and Antioxidant Activities of Green ‘Hayward’ and Gold ‘Haegeum’ Kiwifruits during Ripening with Ethylene Treatment. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, A.; Passos, C.P.; Brandão, E.; Teixeira, N.; Alves, T.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Revisiting Spectrophotometric Methods in the FoodOmics Era: The Influence of Phytochemicals in the Quantification of Soluble Sugars in Plant-Based Beverages, Drinks, and Extracts. Foods 2025, 14, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Hu, C.; Kong, Q.; Shi, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhai, H.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, X. Chitin Combined with Selenium Reduced Nitrogen Loss in Soil and Improved Nitrogen Uptake Efficiency in Guanxi Pomelo Orchard. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Wang, P.; Gao, W.; Wu, S.; Huang, B. Effects of Foliar Spraying with Different Concentrations of Selenium Fertilizer on the Development, Nutrient Absorption, and Quality of Citrus Fruits. Hortscience 2021, 56, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Ran, X.; Zeng, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Mao, C.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Yang, G. Effects of Sodium Selenite Spray on Apple Production, Quality, and Sucrose Metabolism-Related Enzyme Activity. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, P.; Roosta, H.R.; Khodadadi, M.; Torkashvand, A.M.; Jahromi, M.G. Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract, Silicon, and Selenium on Fruit Quality and Yield of Tomato under Different Substrates. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jin, H.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liao, W.; Chen, L.-S.; Guo, J. Fruit Quality Assessment Based on Mineral Elements and Juice Properties in Nine Citrus Cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1280495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Gao, L.; Fu, G.; Du, S.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Wan, Y. Interactive Effects between Zinc and Selenium on Mineral Element Accumulation and Fruit Quality of Strawberry. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.-J.; Wang, Y.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Wu, Q.-S. Positive Changes in Fruit Quality, Leaf Antioxidant Defense System, and Soil Fertility of Beni-Madonna Tangor Citrus (Citrus nanko × C. amakusa) after Field AMF Inoculation. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Bai, R.; Yu, Q.; Bao, Y.; Yang, W. The Effect of Nitrogen Reduction and Applying Bio-Organic Fertilisers on Soil Nutrients and Apple Fruit Quality and Yield. Agronomy 2024, 14, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Huang, T.; Yu, X.; Hong, Q.; Xiang, J.; Zeng, A.; Gong, G.; Zhao, X. The Effects of Rootstocks on Performances of Three Late-Ripening Navel Orange Varieties. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszto, K.; Biskup, L.; Korona, K.; Marcinkowska, W.; Możdżan, M.; Węgiel, A.; Młynarska, E.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Selenium as a Modulator of Redox Reactions in the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Luo, L.; Zhan, J.; Raza, A.; Yin, C. Combined Application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Sodium Selenite Promotes Tea Seedling Growth and Selenium Uptake by Regulating the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025, 61, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).