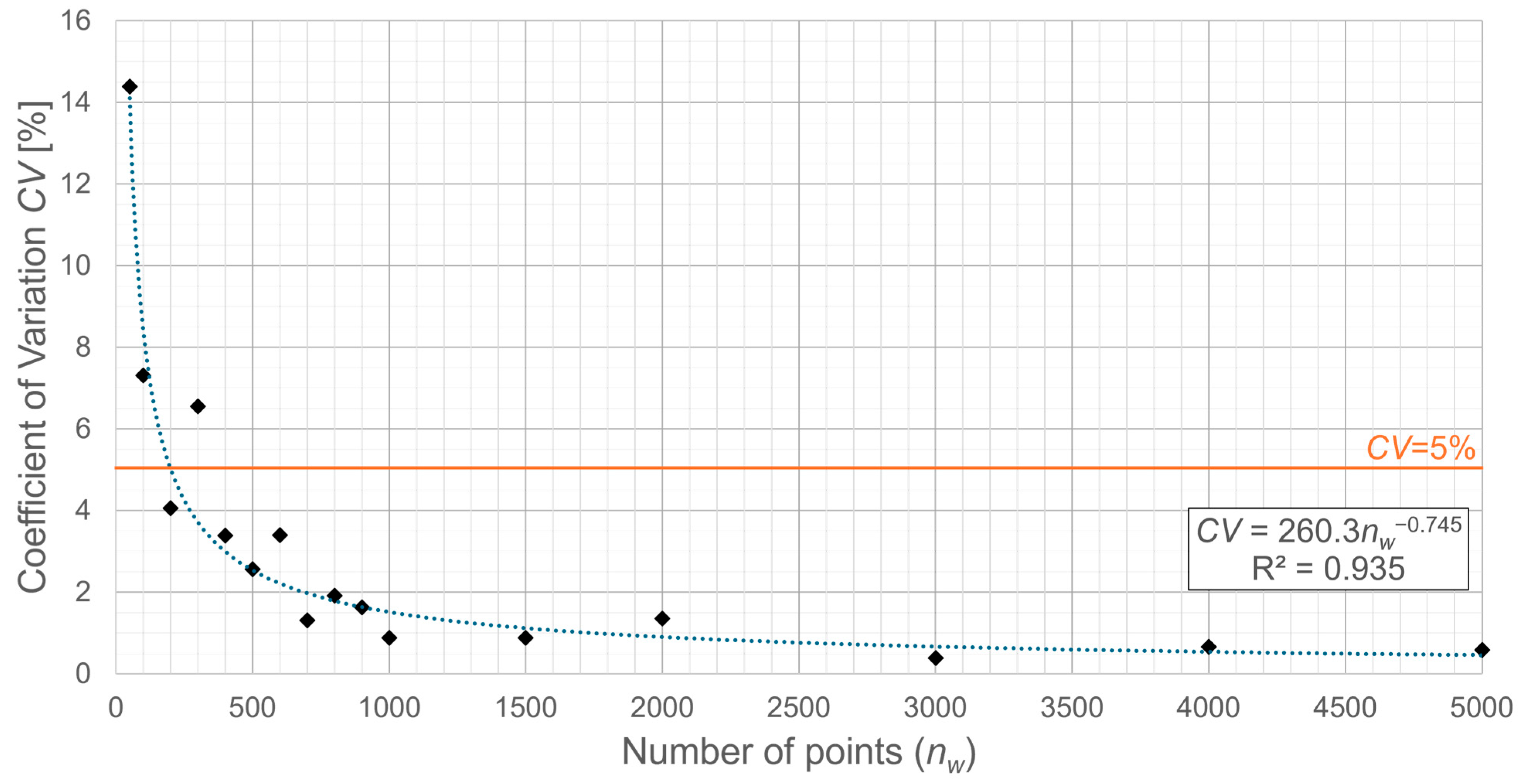

3.1. The Minimum Number of Points for Which the Rfr Values Are Concentrated Around the Mean (Condition I)

The results of the

CV calculations, which are the basis for assessing the clustering of

Rfr values around the mean, are presented in

Table 6. A clear decreasing trend in the

CV values with increasing the number of points forming the structures was observed for all HLSs groups. The maximum

CV value corresponded to

nw = 50 for nearly all HLSs, except HF2 and HH5, for which it was

nw = 100. The difference between the

CV value at

nw = 50 and the maximum was 3.53% and 1.39% for HF2 and HH5, respectively. The minimum

CV values for most HLSs corresponded to

nw = 5000. For HF1, HF4, and HH6, the minimum

CV occurred at

nw = 4000, with the difference of only 0.02%, 0.03%, and 0.06%, respectively, compared to the

CV value at

nw = 5000. For HH2 and HH3, the minimum

CV was observed at

nw = 3000, also with a very small difference compared to the

CV at

nw = 5000 (0.11% and 0.27%, respectively). Considering all the values presented in

Table 6, the highest

CV = 14.39% occurred for the HH3 structure with

nw = 50, while the lowest

CV = 0.01% was for the HH5 structure with

nw = 5000.

The

CV(

nw) relationship proved to be a strictly decreasing function only for HF3. For the remaining structure groups, some deviations occurred, though the general decreasing trend was preserved. An example plot of the

CV(

nw) relationship with the trend line for the HH3 structure group is shown in

Figure 3.

Among the tested functions, the power trendline provided the best fit (

Table 7). The values of the coefficient of determination

R2 were large for the vast majority of structure groups:

R2 > 0.9 for 7 out of 12 structure groups,

R2 less than but close to 0.9 for 2 groups, and

R2 = 0.77 for one group. These large

R2 values confirmed at least a satisfactory fit (very good in most cases) of the power trendline to the

CV(

nw) relationship. Unsatisfactory

R2 values (0.5 <

R2 < 0.6) were obtained for HF2 and HH5, where the maximum

CV was reached at

nw = 100 (not at

nw = 50). After excluding the structures with

nw = 50 from the correlation analysis, a good and very good fit of the power trendline was achieved—

R2 > 0.8 for HF2 and

R2 > 0.9 for HH5.

Inserting

CV = 5% into the trend line equation made it possible to calculate the minimum number of points

satisfying condition I. The calculation results of

are presented in the last two columns of

Table 7. The highest rounded value of

was 200 (for 3 structure groups), and the lowest was 50 (also for 3 structure groups). For half of the analyzed HLSs (6 structure groups),

= 100. It is worth noting that regardless of whether the structure consisting of 50 points was excluded when determining the trend line equation or not,

= 200 and

= 50 were obtained for the HF2 and HH5 structures, respectively. In summary,

satisfies condition I.

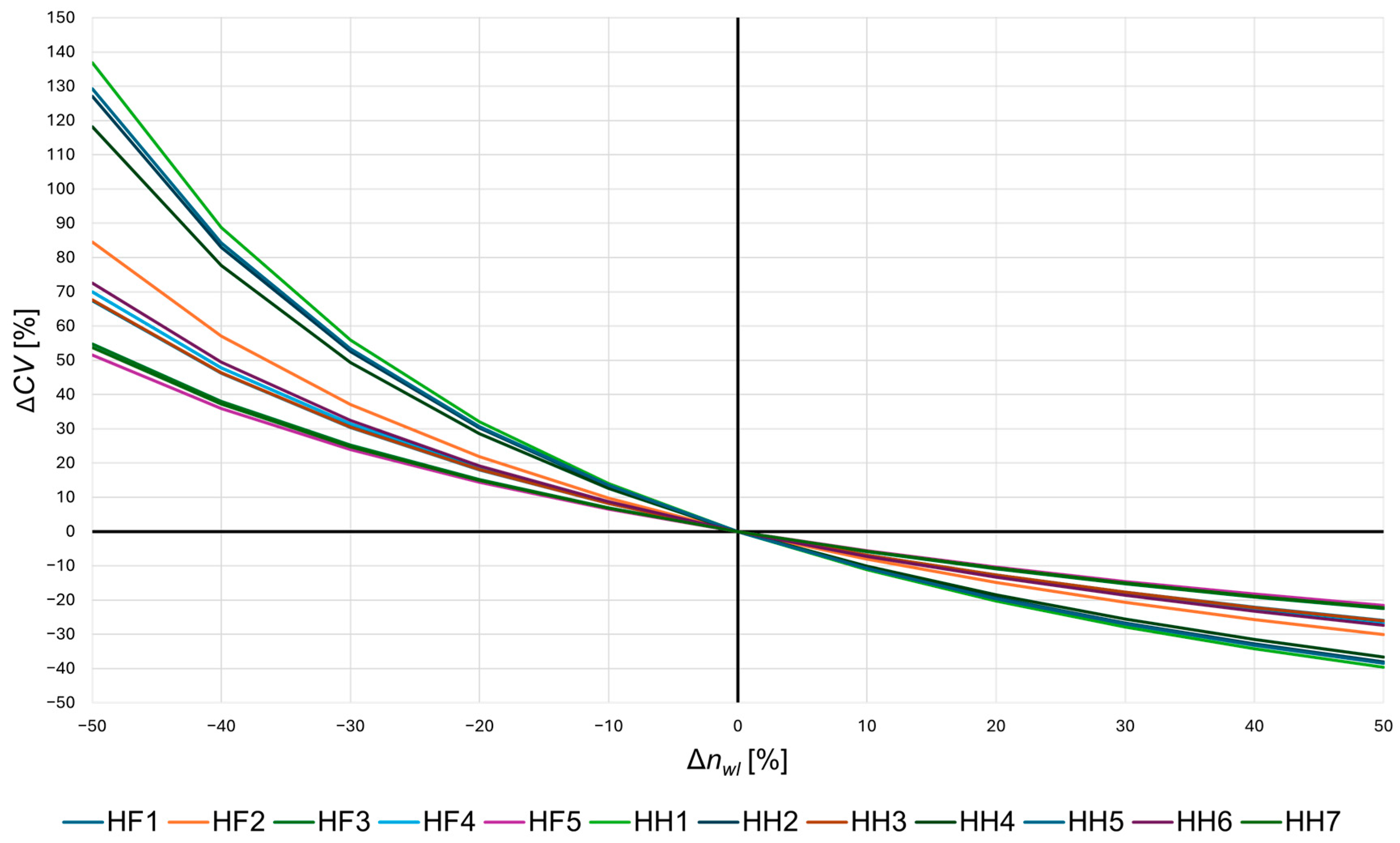

The correctness of the obtained

values was confirmed by the sensitivity analysis of the

CV coefficient of the parameter

Rfr to small variations in

(

Figure 4). A decrease in

results in a clearly larger change in

CV than an increase by the same percentage. For example, reducing

by 50% causes a 2.4–3.5 times greater change in the

CV value than increasing

by 50%. Since the

CV(

) relationship is a decreasing function, lowering

leads to an increase in

CV, indicating a greater dispersion of the

Rfr parameter values. The results of the analysis therefore confirm that the determined

values are indeed the smallest

values satisfying condition I.

3.2. The Minimum Number of Points for Which the Mean Values of Rfr Remains Almost Constant with Increasing nw (Condition II)

The values of unit differences

, calculated according to Equation (1), are presented in

Table 8. The highest absolute values of

were observed for the HF5s structure group; however, these values remained close to zero, ranging from 2.6 × 10

−4 for

= 3000 (omitting 0 for

= 5000) to 25.03 × 10

−4 for

. For the remaining HLSs, the absolute values of

were even lower: from the values of the order of 10

−7 (HH5s), 10

−6 (HF3s, HH1, HH2, HH7), or 10

−5 (HF1, HF2s, HF4s, HH3s, HH4s, HH6s) for

, to the values of the order of 10

−3 for

.

Although all

values turned out to be close to zero, they were clearly higher (by 2–3 orders of magnitude) for lower

nw values compared to the highest

nw. Analyses using Student's

t-test showed that for each HLSs group, there exists a structure of size

for which statistic

, meaning there is no basis to reject the hypothesis that

= 0. An example illustrating the determination of the lowest

for which

(

) for the structures HF1s is presented in

Table 9, while the values of

for all structures are provided in

Table 10. The highest value of

was

= 1000, obtained for half of the HLSs groups (6 out of 12). For three HLSs groups, the smallest possible values were obtained—

=

(50 or 100). It can thus be stated that the values of

vary considerably among the various HLS groups—therefore, one common value of

cannot be assumed for all HLSs.

3.3. Determination of the Radius of the Water Outflow Zone

The

values determine representative structures, based on which the radius of the water outflow zone following a failure of an underground water pipeline (

RWOZ) can be identified. According to the methodology (

Section 2.3), the

RWOZ radius was adopted as the

Rfr values determined for the representative structures, scaled to real-world conditions (

RRC) and rounded to the nearest 0.5 m (

Table 11). Final values of

RWOZ ranged from 3.5 to 5.5 m.

The

RWOZ radius can be expressed mathematically as follows:

where

denotes the entier (the foor function) of

.

Taking into account that

RRC is the product of

Rfr and the inverse of the scale at which the laboratory tests were conducted, and that

Rfr is the product of the fractal dimension of the structure (

) and the distance (in the laboratory scale) of the point forming the structure that is farthest from the origin of the coordinate system ((

Rw)

max), the

RRC radius can be expressed as follows:

where

s denotes the scale of the laboratory model,

Rfr [m],

Db, and (

Rw)

max [m] are values of a representative structure.

Fractal (box-counting) dimension is defined as [

39]:

where

is a non-empty, bounded subset of a finite-dimensional Euclidean space (in the presented investigations:

= HF1, …, HF5, HH1, …, HH6 or HH7),

is the box-counting dimension of the set

, and

is the smallest number of sets of diameter

δ (in the presented investigations: square of side

δ) which can cover

.

The distance (

Rw)

max can be expressed as:

where

Rw [m] is the distance in the laboratory scale of any point creating the HLS from the origin and

is the set of natural numbers.

Substituting Equations (6) and (7) into Equation (5), the following expression is obtained:

Equations (4) and (8) form a system of equations that provides a mathematical description of the RWOZ radius, based on fractal geometry.

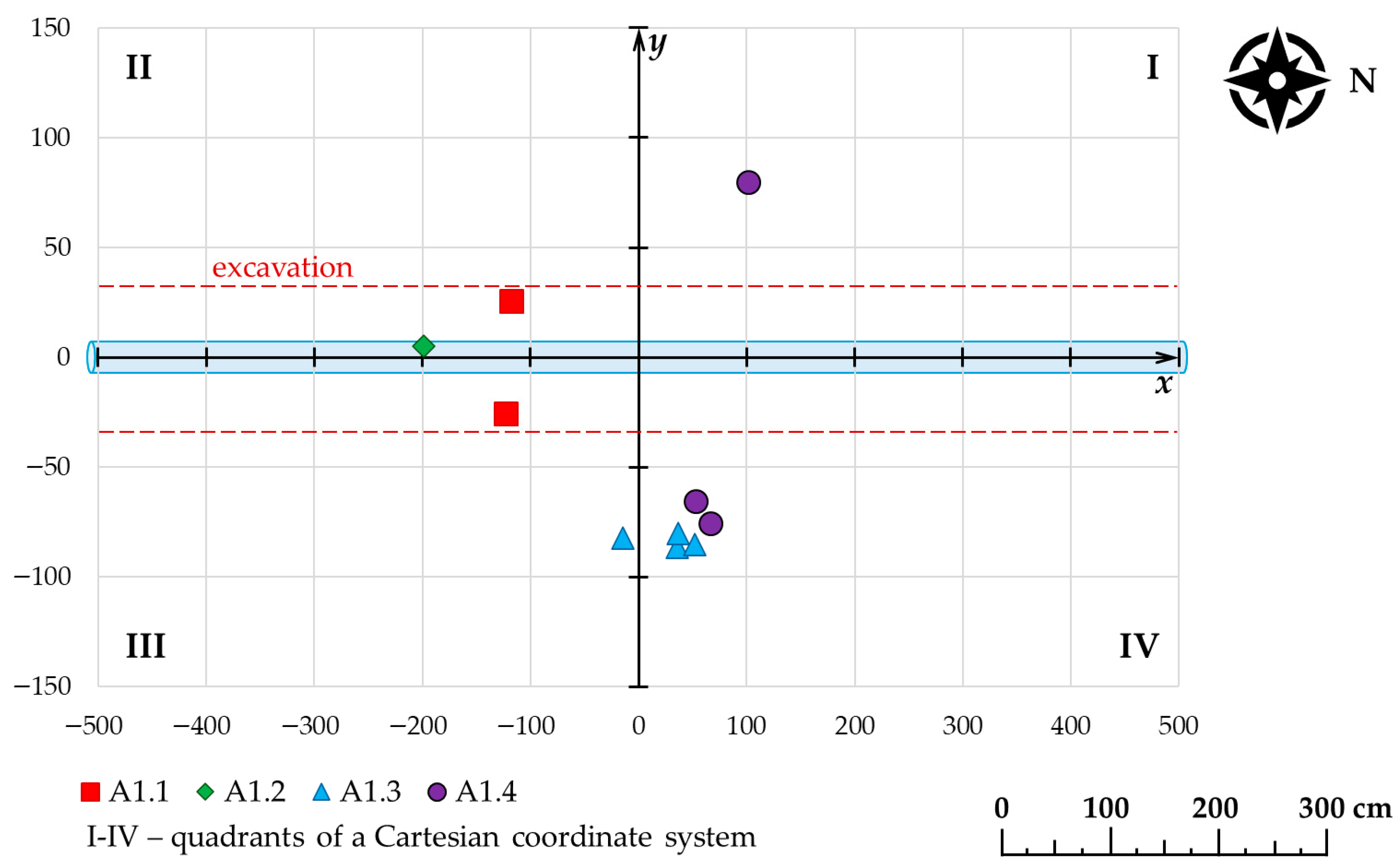

3.4. Field Tests Results

As a result of the controlled waterpipe failure in tests A1.1–A1.4, water outflowed at the ground surface through a total of 10 suffosion holes. As many as seven of these occurred during tests A1.3 and A1.4, where sand was used for backfilling the trench. Detailed results of field test experiments A1.1–A1.4 are presented in

Table 12 and

Figure 5. One outflow hole was observed in the first quadrant of the coordinate system according to drawing 4 (at setup A1.4), two in the second quadrant (at stations A1.1 and A1.2), and two in the third quadrant (at stations A1.1 and A1.3), with by far the most—five—occurring in the fourth quadrant (at stations A1.3 and A1.4). At station A1.2, only one suffosion hole formed—right next to the vertical section of the test pipe. Most likely, the water found a so-called path of least resistance outflow along the pipe. At stations A1.1 and A1.2, the water outflow occurred only within the excavation area, whereas at the other two stations, it extended beyond the excavation boundaries. The average time for water to reach the surface at location A, measured from the start of the experiment, was 18.77 s across all test setups. For tests A1.1 and A1.2, the difference between the outflow times was 3.89 s, with an average of 15.33 s. For setups A1.3 and A1.4, the difference was 6.35 s, and the average time was 22.2 s. Significant differences were therefore observed in the number and location of outflow points, as well as in the time of outflow, when comparing tests with natural soil versus sand backfilling.

In the B2.1–B2.4 series at location B, a total of 9 outflow holes were recorded. Detailed results of field test experiments B2.1–B2.4 are presented in

Table 13 and

Figure 6. Significantly fewer holes appeared at the stations where the leakage area was smaller (smaller pipe diameter). Only one hole formed in the first quadrant of the coordinate system (station B2.3), three holes in the second quadrant (one each at stations B2.1, B2.2, and B2.4), and five holes in the third quadrant (at stations B2.3 and B2.4). No water outflow hole was observed in the fourth quadrant. The average time for water to reach the ground surface in the B2.1–B2.4 test series was 95.78 s. At stations B2.1 and B2.4, the outflow times were comparable, the difference was only 3.19 s. The average times at stations B2.1 and B2.2, and B2.3 and B2.4, were 127.31 s and 101.65 s, respectively.

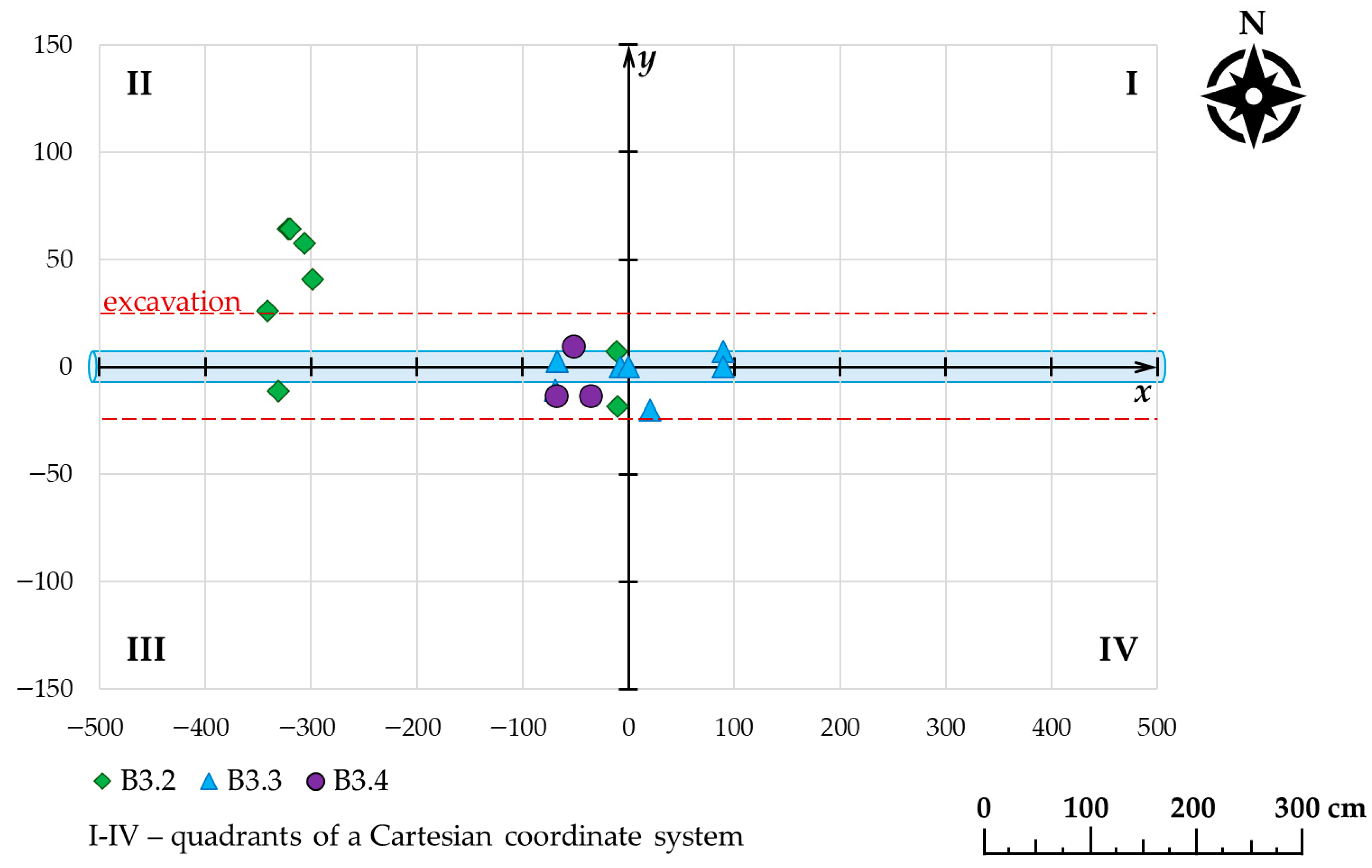

In the B3.1–B3.4 series of tests at location B, no water outflowed at station B3.1. The experiment was terminated after 660 s. The most likely reason for the lack of outflow was that the water found a so-called path of least resistance in the form of an underground corridor. At the remaining stations, water emerged in a total of 18 holes. Detailed results of field test experiments B3.1–B3.4 are presented in

Table 14 and

Figure 7. Station B3.3 was the only one where three water outflow holes were observed directly above the damaged water pipe. Among the other locations, one outflow point was found in both the first and fourth quadrants of the coordinate system (both at station B3.3), eight in the second quadrant (stations B3.2–B3.4), and five in the third quadrant (stations B3.2–B3.4). Excluding station B3.1, the water outflow times in the series B3.1–B3.4 were significantly more varied compared to series B2.1–B2.4. The difference between the longest outflow time (B3.4) and the shortest (B3.3) was 433.81 s, which was nearly twice the average outflow time for stations B3.2–B3.4, amounting to 217.72 s. Only at station B3.4 the outflow time in series B3.1–B3.4 was shorter than in series B2.1–B2.4.

3.5. Empirical Verification

In accordance with the adopted methodology, the results obtained for representative structures HF1–HF3 and HH2–HH4 (i.e.,

RWOZ = 4.0, 4.5 and 5.0 m) were selected for empirical verification (

Table 15).

The verification results are shown in

Figure 8a–c. The outflow zones with a radius

RWOZ of 4.0 m and 5.5 m fully covered all corresponding actual water outflow points observed on the soil surface during the field tests. In the case of the zone with

RWOZ = 4.0 m, 12 out of 18 points were situated no further than 1 m from the pipe leakage location, while the remaining six were no more than 1 m from the theoretical boundary of the zone. The point farthest from the leakage location was located 0.58 m from the zone boundary (

Figure 8a). Among the points in the zone with 5.5 m, 8 out of 20 were no further than 1 m from the leakage location, and only one was located no further than 1 m (0.82 m) from the theoretical boundary of the zone (

Figure 8c).

The only zone that did not cover all actual points was the one with

RWOZ = 4.5 m. All points outside this zone (3 out of 29) corresponded to suffosion holes that formed during the failure simulation at location B: one in series B2.1 (located 0.18 m beyond the theoretical zone boundary) and two in series B2.4 (located 0.37 m and 0.13 m beyond the boundary, respectively). One of the points (also from series B2.4) was located exactly on the zone boundary. Most of the points (18 out of 29) were no further than 1 m from the pipe leakage location (

Figure 8b).

The summary of the verification results is presented in

Table 16. Two theoretically determined zones provided 100% coverage of the actual points corresponding to suffosion holes, and one provided 90% coverage. Taking into account all analyzed points, 3 out of 67 were located outside their respective zones, which represents only 4%. The overall result of the empirical verification of the proposed method for determining the WOZ radius was therefore considered positive.