Abstract

This study explores the impact of sustainable leadership (SL) on environmental performance (EP), focusing on the mediating role of employee well-being (EW) and the moderating role of eco-anxiety in green companies in Turkey. The framework is founded on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) paradigm and is enhanced by Sustainable Leadership Theory, Bottom-Up Spillover Theory, and Terror Management Theory. Data were collected from 289 employees at five environmentally sustainable enterprises in Turkey, using a standardized questionnaire to evaluate characteristics through validated multi-item scales. Structural equation modeling (SEM) with SmartPLS4 was employed to assess reliability, validity, and the suggested correlations. The study’s findings demonstrate that SL has a substantial and favorable impact on EP, both directly and indirectly, through the enhancement of staff well-being. Furthermore, research indicates that eco-anxiety mitigates the association between SL and well-being, suggesting that increased eco-anxiety diminishes the beneficial effects of leadership. These findings underline the significance of robust, SL and proactive management of eco-anxiety to enhance employee well-being and optimize corporate environmental results. The outcomes indicate that firms should allocate resources to leadership development initiatives and staff support frameworks to alleviate climate-related anxiety and enhance resilience. The study advances Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) by demonstrating how psychological health and leadership synergize to enhance environmental performance. It also offers practical implications for sustainable workplace practices.

1. Introduction

Sustainability involves developmental strategies that aim to fulfill the current environmental, social, and economic needs of societies and ecosystems without jeopardizing their future resources [1]. The origins of sustainability date back to the 20th century, when there was a growing concern over environmental degradation and resource depletion. It was at that time that influential works like The Limits to Growth [2] and the Brundtland [3] was published in pursuit of sustainable development through the implementation of a “global agenda for change”. However, over time, this concept has acquired broader content than its original dimensions.

Recent research now recognizes the importance of psychological well-being as a vital component of a sustainable quality of life [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Subsequently, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainability was initiated by the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in 2015, at which 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were established, emphasizing the enhancement of health and well-being [7]. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has become a global priority in various contexts, including organizational practices, social initiatives, and academic environments, where promoting engagement and well-being is recognized as the foundation for sustainable outcomes [4,5,10,11].

Numerous studies [12,13,14] indicated that adopting sustainable practices leads to increased environmental and organizational performance in contemporary businesses. As a result, these sustainable workplace practices are now widely valued in various fields, including industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology, as a powerful tool for creating a healthier and more supportive work environment where employees can truly grow and maintain their engagement over the long term [15]. I-O psychologists seek to promote sustainability by integrating sustainable practices into key organizational areas. Their work touches upon human resource management, employee well-being initiatives, organizational change processes, workplace culture, and leadership [7,16,17,18,19]. Firms are pointedly reliant on the mental well-being of the workers, and those with very high performance in operations demonstrate 88% of their staff have good mental well-being [20]

A significant body of research confirms that sustainable leadership practices result in a wide range of positive outcomes, such as enhanced employee well-being, improved performance, increased trust and empowerment, greater engagement and innovation, higher resilience, and stronger environmental performance [21,22]. As a result, sustainable leadership is increasingly valued for its capacity to cultivate a workplace culture that successfully emphasizes environmental sustainability while prioritizing employee well-being as a key driver of long-term environmental performance [21,23]. Avery and Bergsteiner [24] also supported this, arguing that Sustainable leadership necessitates a long-term perspective in decision-making, promoting systematic innovation to enhance customer value, developing a talented, loyal, and highly dedicated staff, and providing high-quality products, services, and solutions.

Given that the United Nations’ SDGs focused on promoting well-being and engagement, sustainable leaders today are expected to develop initiatives that enhance employee wellness. This focus is strongly supported by research, which consistently indicates a significant positive correlation between employees’ subjective well-being and stronger workplace performance [25,26,27,28].

The need for sustainable practices becomes even more critical when we consider external environmental stressors. Factors such as climate change and extreme heat have a direct impact on employees’ psychological and physical well-being, underscoring the importance of robust organizational sustainability measures for employee well-being [29,30].

According to the World Health Organization [31], the environmental crisis produces a wide range of psychological consequences, including psychological strain, difficulties in emotional regulation, bereavement, and behavioral disturbances. A growing body of research examines eco-anxiety, defined as the distress experienced in response to ecological crises, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, deforestation, extreme weather events, and rising sea levels [32]. Anxiety related to climate change can be driven by concerns about economic stability, worries for future generations, and fears of potential catastrophic consequences, often leading to feelings of helplessness and psychological distress [33].

Additionally, environmental stressors such as extreme heat may impair employee performance, increase accident risk, reduce work capacity, and decrease economic productivity [26,34,35,36]. Therefore, contemporary organizations and sustainable leaders must implement sustainable practices and incentives that help employees manage eco-anxiety, thereby safeguarding their psychological well-being and maintaining high environmental performance [37,38].

While prior research has consistently shown that SL enhances employee well-being and broader organizational outcomes by fostering resilience, promoting green innovation, and encouraging psychological empowerment [21,23,39,40] relatively little is known about the role of psychological stressors in this process. In this regard, the moderating effect of eco-anxiety on employee well-being, in particular, has not yet been examined. Thus, this study seeks to fill this gap by investigating eco-anxiety as a mediator of the relationship between SL and employee well-being. Additionally, existing studies have not fully integrated psychological demands such as eco-anxiety into their theoretical frameworks, leaving an important gap to understand how emotional distress may affect the effectiveness of sustainable leadership practices. The interaction among these variables is anticipated to mitigate the influence of sustainable leadership on environmental performance. This study enhances the literature on sustainable leadership and environmental performance by offering new insights into the psychological processes and contextual elements that affect leadership effectiveness in modern organizations. It also develops current theoretical models through the inclusion of both mediating and moderating psychological mechanisms that have been largely overlooked in prior research.

This study is primarily based on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory [41,42]; however, to create a more comprehensive understanding, we also complemented it with the theory of sustainable leadership [43], the bottom-up spillover theory of well-being [44], and the Terror Management Theory (TMT) [45,46].

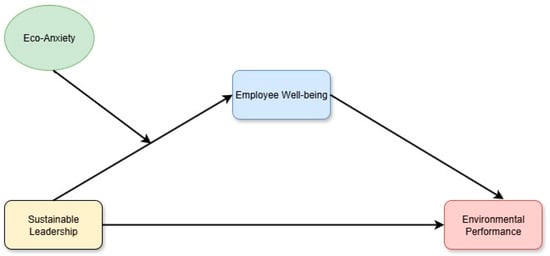

Together, these frameworks provide a basis for examining how sustainable leadership and eco-anxiety interact to influence the well-being of the employees and, in turn, environmental performance. Therefore, the conceptual model (Figure 1) illustrates the direct relationship between SL and organizational performance, the mediating effect of psychological well-being, and the interaction effect of Eco-anxiety.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model. Source: Developed by authors.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

This study draws its theoretical foundation primarily from the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, which offers a broad insight for examining how different aspects of the work environment, including leadership practices, affect employees and, by extension, organizational outcomes [41,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

The JD-R model assumes that the equilibrium between job demands and job resources fundamentally determines the well-being of employees and performance. Thus, within this study, we conceptualize sustainable leadership as a vital job resource, one that furnishes employees with essential support, ethical guidance, operational clarity, and a meaningful long-term purpose. It is therefore expected that the interaction between these variables improves employee well-being, which in this case will act as a mediator between leadership practices and environmental performance. This claim aligns with the JD-R proposition that resources stimulate positive outcomes by positively influencing psychological well-being.

The JD-R framework is also notable for its ability to integrate the moderators into the research variables. Accordingly, eco-anxiety is conceptualized as a significant job demand in the present study. We thus propose that higher levels of eco-anxiety may reduce employees’ psychological resources and increase stress, thereby undermining the beneficial effects of sustainable leadership practices. This conceptualization is consistent with prior evidence showing that eco-anxiety produces emotional strain, disrupted sleep, muscle tension, and disrupts employees’ ability to utilize available job resources fully [54,55]. Our proposal aligns with the principles of the JD-R model, emphasizing the critical influence of job resources in fostering positive individual and organizational outcomes. Within this framework, SL functions as a resource that motivates employees, whereas eco-anxiety serves as a demanding environmental stressor that can weaken this motivational pathway; thus, eco-anxiety moderates the magnitude of leadership’s impact.

To develop a more comprehensive framework, this research combines various insights from several interconnected theories. First, the Sustainable Leadership Theory [24,43] highlights the ethical responsibility of leaders to promote long-term sustainability. Second, the Bottom-Up Spillover Theory of Well-being [44] describes how improvement in employee well-being can lead to positive spillover effects, fostering environmentally responsible behaviors and enhancing overall work performance. Third, Terror Management Theory [45,46] offers a valuable framework for understanding eco-anxiety by defining it as a profound psychological response to the existential threats posed by environmental crises. Utilizing the JD-R model as a foundation, this integrated theoretical framework demonstrates the dynamic interplay between sustainable leadership, functioning as a resource, and eco-anxiety, operating as a demand. It is then proposed that the interplay between these factors jointly influences employee well-being, which subsequently affects the environmental performance.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Sustainable Leadership and Environmental Performance

As urgent environmental issues such as climate change, pollution, and depletion of resources become more pressing, an increasing number of organizations worldwide are integrating sustainability principles into their core strategic agenda [56]. In this context, sustainable leadership is recognized as a vital force driving positive organizational outcomes. This leadership style not only cultivates employee-centered behaviors but also contributes directly to improved environmental performance [21,57,58,59]. By consistently integrating environmental considerations into organizational strategies, sustainable leaders make substantial contributions to tackling these critical global challenges [60].

Sustainable leadership, at its core, is a pledge to long-term stability that weaves together social and economic imperatives. In practice, leaders who truly embody this approach advocate for responsible resource management while actively curbing the most harmful industrial impacts, such as pollution, deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity loss [21,61,62]. Despite the growing attention to sustainability, a significant gap still lingers in the literature. A substantial portion of the literature has yet to elucidate the specific mechanism through which practices improve environmental performance, particularly in terms of reducing ecological footprints and integrating sustainable practices across diverse industry sectors [63].

Campos et al. [64] conceptualize an organization’s performance as its knack, defined by its ecological imprint through measures such as pollution control, heightened energy efficiency, and waste reduction. Within this framework, leaders function as catalysts. By embodying sustainable behaviors, they promote eco-conscious practices across the workforce. That creates a ripple effect that ultimately improves the organization’s overall environmental performance [65,66,67,68].

A growing body of research has highlighted leadership as a key element that determines the way organizations address and mitigate the environmental degradation from industrial activities [21,58,69,70].

Although recent research has provided valuable insights into sustainable leadership and environmental performance, the existing body of evidence remains fragmented and is frequently limited to specific national contexts or particular industry sectors. Illustrative examples include studies focusing on IT companies in Denmark [21], tourism companies in Portugal [65], and textile manufacturing firms in developing countries [66]. A systematic review of the literature reveals a pronounced geographical bias in this field of research, with very little scholarly attention devoted to countries like Turkey [71]. Furthermore, a significant gap persists in research concerning green enterprises, those organizations founded with sustainability as their core principle. This gap persists despite the growing and critical role these enterprises play in driving the transition towards sustainable economies.

This research aims to fill existing gaps by exploring how sustainable leadership impacts environmental performance in green enterprises within Turkey. This approach broadens the empirical research into a new geographical area as well as an organizational framework [72]. From this perspective emerges the following hypothesis:

H1.

Sustainable leadership has a significant and positive effect on the environmental performance of green enterprises.

2.2.2. Employee Well-Being as a Mediator

Recent studies underscore the crucial role of employee well-being as a significant mediator within the relationship between sustainable leadership and environmental performance. Sustainable leadership, characterized by long-term vision, ethical governance, and an inclusive operating environment, fosters a culture that enhances employee well-being and demonstrates a commitment to environmental sustainability [61]. Considerable research evidence supports this mediating effect. For example, Ahsan and Khawaja (2024) [21] indicate that sustainable leadership promotes well-being, which, through increased engagement and pro-environment behaviors, positively affects environmental performance. Similarly, in their investigations, Piwowar-Sulej and Iqbal [73] found that well-being played a facilitating role in the connection between leadership sustainability and pro-environmental innovation. They emphasized the importance of having an environment conducive to promoting good working conditions. Demir et al. [74] buttressed the model, revealing that green transformational leadership promotes working through the combined mediating effects of fostering the well-being of the staff while driving innovation.

Consequently, leaders who actively promote sustainability secure favorable environmental outcomes by simultaneously fostering innovation and enhancing employee well-being.

Overall, this body of literature suggests that employee well-being occupies an indirect mediating role in the relationship between sustainable leadership and eco-friendly performance. Accordingly, organizations wishing to enhance their environmental performance would be advised to incorporate activities that improve employee well-being into their leadership practices. We therefore hypothesized:

H2.

Employee Well-being mediates the relationship between Sustainable Leadership and Environmental Performance in green enterprises.

2.2.3. Moderating Effect of Eco-Anxiety

A constant concern for the future of the Earth and the welfare of future generations characterizes eco-anxiety. It is defined as feelings of helplessness, sadness, and rage related to environmental pollution and climate change [75]. This moderating effect can be explained by the psychological strain associated with eco-anxiety. Eco-anxiety can predict mental health problems and psychological well-being. It can adversely affect mental health and eventually cause tension and anxiety, specifically among children and young people [76]. Eco-anxiety is a significant predictor of mental health issues in a variety of contexts, according to many domain experts [75,76,77] the psychological depletion explains why the beneficial effect of sustainable leadership on employee well-being becomes significantly weaker under conditions of high eco-anxiety.

While the previous discussion establishes the connection between SL, EP of organizations, and well-being, the degree of this effect is likely to be highly influenced by the psychological state of the employees concerned. Eco-anxiety is such an important variable in this context, for it has been recognized as a mental health issue and a serious workplace problem that directly impacts the productivity and performance effectiveness of organizations [78].

On the other hand, earlier studies focusing on the behavioral effect of climate-related anxiety suggest that this does not translate easily into a linear relation with pro-environmental behavior, but rather a non-linear strategy [79]. Accordingly, climate-related anxiety does not appear to have a uniform impact on pro-environmental behavior, as moderate levels of concern may foster collective action and information-seeking, whereas excessive anxiety is often linked to withdrawal, paralysis, or a reduced capacity for goal-directed engagement [80,81,82,83,84]. According to McCombs and Williams [85], individuals experiencing high levels of eco-anxiety often face lower psychological well-being, along with decreased feelings of efficacy, and struggle to translate their environmental concerns into actionable steps. These insights imply that increased eco-anxiety may undermine the explicit connection between sustainable leadership and sustainable performance.

Even when sustainable leaders and resources provide guidance on engaging in meaningful environmental activities, the success rate may fall short because employees cannot effectively communicate their philosophical engagement in meaningful workplace behavior. Therefore, for sustainability initiatives to succeed, leaders may need to address climate-related distress directly. This can be achieved by offering psychosocial support, creating empowerment initiatives, and bolstering employees’ sense of efficacy—thereby establishing the necessary conditions for sustained pro-environmental engagement. Therefore, proactively addressing eco-anxiety may be essential for preserving the effectiveness of sustainable leadership. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3.

The positive effect of sustainable leadership on psychological well-being diminishes under higher levels of eco-anxiety.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure

The approach used in this research was a quantitative style that focuses on hypothesis testing and examination [86]. Contributors to this study were selected from 5 green, environmentally oriented companies in Turkey, recruited from major industrial regions in the country. The companies were specifically chosen as they represent the growing trend of organizations incorporating sustainability into their core policies. The skill of these organizations in adapting and implementing innovation presents a perfect opportunity to examine the delicate associations between employee well-being, sustainable leadership, and performance within the environment. The selected respondents are employed in departments considered to possess a comprehensive understanding of green business plans and operations within the organization. The sampling technique employed was a simple random sampling process, thereby providing everyone an equal opportunity to be selected.

3.2. Procedure and Data Collection

The data was sourced by implementing a questionnaire, which was distributed online. Sample size was calculated by means of G*Power 3.1 for a linear multiple regression model with two predictors and considering a small effect size (f2 = 0.1). The further indicators are selected cautiously (α = 0.01, 1 − β = 0.95). Consequently, the software proposed a minimum of 212 participants (Figure S1). The primary data were collected through structured questionnaires from participants who held a variety of job titles, including engineers, technicians, environmental consultants, product designers, and other positions within the company. The survey utilized a 5-point Likert scale, varying from “Strongly Disagree” to Strongly Agree” to value the participants’ opinions of the variables. To select organizations, we initially identified several large-scale green companies in Turkey with more than 50 employees to ensure the minimum sample size required by G*Power. After contacting multiple firms, five companies agreed to participate in the study, which enabled us to obtain a final sample of 289 valid responses out of 400. As a result, the response rate is accepted at 72%. A prior pilot study was conducted to ensure that the questionnaire was clear and understandable, thereby preventing confusion.

3.3. Measurement

Scales designed in prior studies were used to create the questionnaire, measuring the construct. Eco-anxiety (ECO) was evaluated with 13 items adapted from the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale [32]. This scale highlights four dimensions: (1) Affective Symptoms (4 items), (2) Rumination (3 items), (3) Behavioral Symptoms (3 items), and (4) Personal Impact Anxiety (3 items). SL is assessed using 14 items, as proposed by Ahsan and Khawaja [21], which incorporate sustainability principles into organizational leadership. EW was advanced by Ahsan and Khawaja [21] with 14 items that focus on the psychological and emotional aspects of employees’ practices in the workplace. EP was calculated using five items, as developed by Ahsan and Khawaja [21], which measure environmental practices and their impact on the quality of processes and production (See Table S1).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

To test the study hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using SmartPLS 4. The survey employed in this research was separated into three areas: demographic, outer model, and structural model tests. Testing the outer (measurement) model is necessary to assess the observed variables. Inner (structural) models evaluate the latent variables that comprise several organized steps. The outer model evaluation comprises reliability and validity, discriminant validity, and model fit assessment. The inner model encompasses path coefficient evaluation and significance testing.

4. Result

4.1. Demographic Distribution

Males (54.3%) represent the majority of respondents as opposed to females (45.7%). Most of the respondents were younger, aged between twenty-five and forty years (76.9%), with 7.3% being under 25 and only 5.5% being over 46. In the occupational category, engineers and technicians were the highest (32.9%), followed by project managers (24.2%), researchers and developers (15.9%), product designers (12.5%), environmental consultants (8.3%), and other roles (6.2%). In terms of work experience, 11.8% had less than one year of experience, whereas 54% possessed 1–6 years, 24.2% had 7–9 years, and 10% indicated more than 10 years. In educational terms, 37.7% achieved a bachelor’s degree, 29.8% just achieved a high school diploma or lower, 13.5% possess a vocational degree, 10.7% received a master’s degree, and 8.3% received a PhD or higher (See Table S2).

4.2. Outer Model Assessment

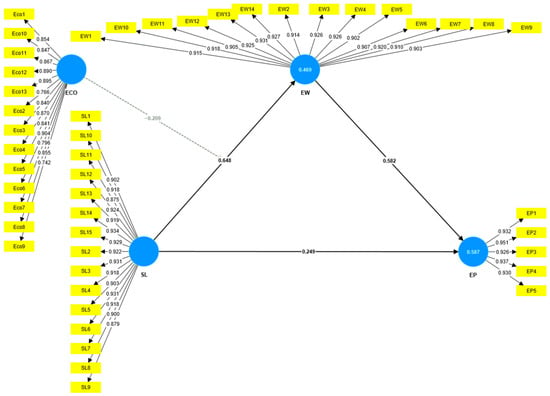

The outer model is being analyzed using SmartPLS4. The model demonstrates hypothesized relations concerning SL and environmental performance, whilst highlighting the mediation effect of employees’ well-being and the moderating impact of eco-anxiety between SL and EW (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Outer model coefficients. Source: author’s analysis. Note: Eco = Eco-Anxiety, SL = Sustainable Leadership, EP = Environmental Performance, EW = Employee Well-being.

Table 1 illustrates an outline of the items associated with each variable. The outer loadings of each item were assessed to appraise the outer model. To assess convergent validity, the authors further measured Cronbach’s alpha, Composite reliability, and AVE (average variance extracted).

Table 1.

Outer loadings, construct validity, reliability, and AVE.

Cronbach’s alpha (>0.7) and Composite reliability (>0.7) values were determined to be within the acceptable threshold values. Furthermore, the reliability and validity test results indicated that all the ACE values were more than 0.5. As a result, the convergent validity was valid (See Table 1).

The HTMT criterion was applied to appraise discriminant validity. If the HTMT is lower than 0.9, discriminant validity can be ascertained. In numerous practical situations, a threshold of 0.85 consistently distinguishes between pairs of latent variables that are discriminantly valid as opposed to those that are not [87] (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Herterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) Matrix.

The HTMT ratios in Table 2 remain below the conservative threshold of 0.85, thereby reaffirming that each construct is empirically distinct from the others and that the constructs are valid.

The Fornell-Larcker test is a statistical method utilized in structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate the discriminant validity of constructs [88]. For the discriminant validity to be recognized, the square root of AVE should be higher than its correlation with any other construct in the model [89].

Based on Table 3, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was satisfied, as the square roots of the AVE were higher than the corresponding correlations between the constructs.

Table 3.

Fornell and Larker.

Table 4 indicates the SRMR value of 0.051 drops considerably below the recommended limit of 0.08, thereby demonstrating an acceptable fit to the model. Likewise, the NFI value of 0.930 surpasses the required threshold of 0.90, thereby demonstrating that the model accomplishes a satisfactory level of comparative fit [90]. As a result, model fit statistics highlight that the measurement model is satisfactory.

Table 4.

Model Fit Statistics.

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

The inner model is confirmed through smart PLS4 using bootstrapping (5000 resamples). We reported path coefficients, mean STDEV, T-statistics, and p-values via Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypothesis Testing.

4.3.1. Direct Effects

Using PLS-SEM with bootstrapping, the structural model demonstrates that sustainable leadership holds a positive and statistically significant impact on environmental performance, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1 (β = 0.249, t = 4.933, p < 0.001). This suggests that stronger sustainable leadership is linked to improved environmental performance.

4.3.2. Mediation Analysis

Table 5 suggests an indirect pathway from green leadership to environmental performance, well-being of employees (H2). The mediation influence is positive and significant (β = 0.377, t = 8.956, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the effect of green leadership on ecological performance is partially achieved through enhancements in employee well-being. Therefore, sustainable leadership enhances employee well-being, which leads to improved environmental performance. The result suggests a significant indirect contribution.

4.3.3. Moderation Analysis

Table 5 posited that eco-anxiety weakens the positive links between sustainable leadership and employees’ well-being (H3). The interaction term is negative and significant (β = −0.209, t = 3.449, p = 0.001). It confirms that higher levels of eco-anxiety dampen the beneficial effect of sustainable leadership on employee well-being. Practically, when eco-anxiety is elevated, the capacity of leadership to boost well-being is reduced considerably.

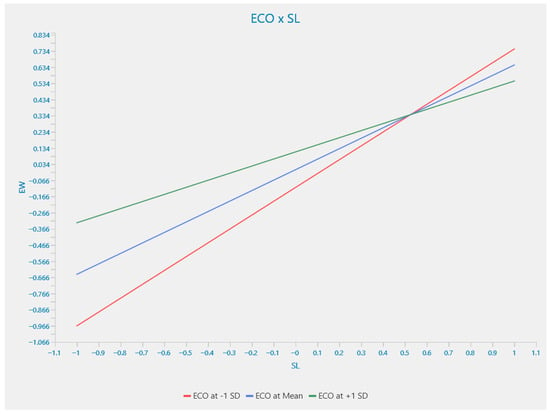

Figure 3 illustrates that the positive impact of green leadership on EW varies according to the level of eco-anxiety. When eco-anxiety is low, sustainable leadership produces the most substantial improvements in well-being. At average levels of eco-anxiety, the positive effect remains but is weaker, while at high levels of eco-anxiety, the effect is considerably diminished. This pattern suggests that eco-anxiety may limit how sustainable leadership can positively impact employee well-being.

Figure 3.

Simple slope analysis. Source: author’s analysis.

5. Discussion

This research paper’s results support the hypothesis of the research (H1) by appraising the impact of SL upon the EP (β= 0.249, p value= 0.000). This supports previous research results highlighting the value of sustainable leadership in creating the organizational environment and its results [21,86,91,92]. The progressive impact of SL and environmental performance stems from leaders who support and promote sustainability initiatives, resulting in improved environmental practices both within and outside their companies [21]. Leaders who are oriented towards sustainability tend to concentrate not just on short-term profit but also consider the environmental impacts, eventually allowing the organization’s performance to improve in the long term [23]. Green organizations, specifically in Turkey, should sponsor and implement programs for leadership development to promote sustainability ideas.

Secondly, the well-being of employees mediates the correlation between EP and SL (H2). The mediation analysis thereby provides robust support for H2 (β = 0.377, p < 0.000), suggesting that the well-being of employees plays a central role in achieving organizational environmental performance. The study’s findings are inconsistent with those of a previous study conducted by Ahsan and Khawaja [21] and Queyu Ren et al. [58] Employee well-being is a crucial pathway through which green leadership influences ecological performance. This highlights the holistic effect of SL on organizational outcomes, most particularly the mediating impact of staff comfort, which underscores its influence.

Thirdly, this research examined the moderating role of eco-anxiety, thereby lessening the positive effect of green leadership on the well-being of employees. The results confirm that eco-anxiety moderates the negative connection of green leadership and EP (β = −0.209, p < 0.001). This finding supports Hypothesis 3 and contributes to a growing body of literature emphasizing the role of eco-anxiety as a main hindrance within green organizations. These adverse findings align with those scholars who have identified eco-anxiety as a significant barrier to employee well-being development [77,93,94,95]. Individuals experiencing eco-anxiety may find their everyday activities unenjoyable and endure constant stress. They have experienced poor sleep and a sense of ineffectiveness in the world due to eco-anxiety and concern. They lack the autonomy to determine their own activities. They perceive themselves as hopeless, experiencing depression and misery, while their self-esteem is consistently deteriorating [77].

To sum up, the current research presents strong empirical evidence emphasizing the crucial role of employee well-being and SL in predicting environmental performance. Our study findings add to the body of literature by demonstrating how psychological factors such as eco-anxiety diversely affect the health of the employees. The findings support the necessity of organizations to give psychological well-being as a top priority when developing sustainability-driven leadership strategies. This study thus contributes to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3), which aims to support employees’ Good Health and Well-being. It demonstrates how organizational leadership and workforce well-being interact to advance environmental sustainability in practice.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings of our study offer several important theoretical contributions. Firstly, the extension of Job Demand-Resources theory (JD-R) [41] highlights eco-anxiety as a relevant job requirement that moderates the correlation between SL and EW. Although previous research has concentrated on more established workplace triggers, our findings propose that climate-impacting anxiety has a comparable effect on how employees benefit from leadership-provided resources. Our findings further enhance the JD-R framework by highlighting that environmental stressors are linked to a broader classification of job demands.

Secondly, by connecting SL [7] with eco-anxiety [96,97], this paper contributes to the growing body of research linking leadership studies with environmental psychology. Past research has highlighted that SL advances environmental performance by fostering innovation and support within the organization [21]. The present study contributes to existing knowledge by demonstrating that employee well-being serves as an essential mediator in the relationship between SL and sustainable outcomes, with eco-anxiety moderating the extent to which this pathway is reinforced. These findings demonstrate that SL must consider both ecological imperatives and the psychological needs of employees.

This research also contributes to the sustainable work environment literature by emphasizing the psychological components of sustainability. Previous research on sustainability concentrated on social, economic, and ecological areas [2,3] as opposed to more recent investigations that have added quality of life for humans and psychological well-being [4,5]. Our results indicate that this trend will continue by highlighting that the effectiveness of leadership within the context of sustainability depends not only on the organization’s policies but also on how employees manage environmental distress [23,78].

5.2. Practical Implications

Furthermore, this paper offers practical suggestions for organizational leaders and decision-makers. The development of leadership through programs must equip managers with the appropriate skills to address and assist with eco-anxiety among employees. Sustainable leaders can provide psychosocial support, initiate empowerment policies, and create opportunities for participation in decision-making training to enhance employees’ self-awareness and efficiency, aiding in the challenges of environmental change [59,78,98]. These opportunities safeguard employee well-being [98,99] and create conditions that generate positive environmental workplace actions [78,98].

Companies must evolve complete employee support networks to tackle climate-initiated distress. Schemes like eco-anxiety counseling, training for resilience, or colleague support groups will assist employees in channeling their climate-related concerns into more constructive activities [100]. This tactic reduces eco-anxiety from developing a pro-environmental obstacle and enables it to become a positive force on sustainable enterprises [59]. The current research underlines the significance of inserting sustainability into companies’ plans and HRM practices. Green human resource management [58] and incentives for positive environmental performance can enhance staff involvement and align personal ideas with the organization’s goals. This approach aligns with leadership aims by creating a support network that fosters environmental positivity and encourages behaviors rewarded for sustainable activities.

Finally, our results propose that tackling eco-anxiety can directly impact the strength of the organization and its functioning. If ignored, climate-related anguish could wear down the well-being and performance of employees [78,98]. When managed with supportive leadership and organizational practices, eco-anxiety can become proactive engagement, safeguarding employee well-being and enhancing environmental performance.

In total, companies can implement several targeted strategies to improve worker wellbeing and lessen eco-anxiety. Sustainable leaders can reduce feelings of helplessness by implementing systematic climate-anxiety awareness programs that help staff understand and place environmental risks in context. Workshops on resilience-building, mindfulness exercises, and stress-management training may provide employees with coping skills that lessen the psychological effects of eco-anxiety.

6. Limitations and Recommendations

Even though this paper provides valuable experience in the impact of SL upon the sustainable functioning of green organizations in Turkey, it offers some limitations that offer areas to explore for future research. First, the sample was restricted to specific job categories in green companies in Turkey, potentially limiting the findings’ generalizability. Future research may include different sectors in green-adapted companies in other countries, such as those in Europe or the US. The second potential limitation pertains to the study’s cross-sectional design, which involved gathering data through a survey tool. Therefore, Additional longitudinal studies must be undertaken to enhance the validity of outcomes in future research. Using the longitudinal method, researchers can better identify causal relationships by tracking the interactions among the variables over time. Thirdly, the dependence on self-reported data could offer some forms of bias. Therefore, future studies may utilize multi-source data collection techniques to augment the reliability of the findings. Fourthly, Turkey’s cultural background may influence how respondents interpret and respond to the survey questions, shaping their views on leadership, environmental attitudes, and manifestations of eco-anxiety. Therefore, it would be beneficial to conduct cross-cultural comparative research to determine whether these linkages function similarly across institutional, cultural, and environmental contexts. Fifthly, the study model ultimately incorporated eco-anxiety as a moderating variable. As a result, further study should examine additional variables that could impact the relationships between EP, leadership, and EW, offering a more balanced comprehension of the following: resilience, employee engagement, and organizational climate. Last but not least, eco-anxiety may vary by gender and degree of education; specifically, it may manifest differently in men and women. However, these factors were not taken into consideration in our model. This variation in eco-anxiety across demographic groups warrants further investigation; therefore, researchers should examine these disparities in the future.

7. Conclusions

To conclude, this research examined the delicate relationships involving green leadership and EP from the perspective of green companies in Turkey. The mediating impact of EW on the relationship between SL and EP was examined. The study also analyzed the negative role of eco-anxiety as a moderator of the study. Theoretically, these findings enrich existing knowledge by integrating Terror Management Theory (TMT) [45,46] and the JD-R model into a unified explanatory framework. Unconscious defenses identified by TMT can block and promote rational responses to global climate change [101]. At the same time, the JD-R model captures how SL, as a vital organizational resource, interacts with eco-anxiety to shape employee well-being, which in turn influences EP. SL uniquely emphasizes the growth and well-being of its followers. Based on the study’s findings, SL has a direct and significant positive effect on EP (H1). EW plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between SL and EP (H2). Eco-anxiety weakens the impact of SL on EW, in that way reducing its indirect impact on sustainability outcomes (H3).

Practically, sustainable leaders within green companies are expected to encourage organizations to operate positively, impacting local communities, cultural preservation, and wise management of natural resources [102]. Sustainable leaders are supposed to use strategic organizational resources to generate distinctive abilities that are complicated for competitors to copy, improving the company’s sustainable performance [86]. This study fulfills the primary purpose of the study, focusing on employee welfare and how it affects the environmental performance in green businesses. The research contributes to the theoretical understanding of how leadership interacts with employee psychological states to affect environmental results. Practically, the study provides clear recommendations for organizations, highlighting climate-related challenges and employee well-being as crucial components of successful sustainability-driven leadership practices.

In conclusion, by integrating leadership, environmental performance, and well-being, this research contributes to the broader United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, specifically SDG 3, which promotes the health and well-being of employees. Therefore, organizations must ensure that they safeguard the health and engagement of their workforce while also meeting environmental targets.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172410989/s1, Figure S1. Gpower; Table S1. Questions and resources; Table S2. Demographic Characteristics. References [21,32] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.; methodology, N.S.D. and P.F.; software, N.S.D.; validation, P.G.K. and A.V.; formal analysis, N.S.D.; investigation, P.F.; resources, A.V.; data curation, N.S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G.K. and N.S.D.; writing—review and editing, P.F. and N.S.D.; visualization, A.V.; supervision, P.F.; project administration, N.S.D. and P.G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Arucad Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design (2024-2025/006) dated at 26 September 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents participating in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruggerio, C. Sustainability and Sustainable Development: A Review of Principles and Definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report to The Club of Rome (1972); Potomac Associates: Potomac, MD, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Anshari, M.; Syafrudin, M.; Fitriyani, N.L.; Razzaq, A. Ethical Responsibility and Sustainability (ERS) Development in a Metaverse Business Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Duarte, F.; Tordera, N.; Rodríguez, I. Overcoming Virtual Distance: A Systematic Review of Leadership Competencies for Managing Performance in Telework. Front. Organ. Psychol. 2025, 2, 1499248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Innovation as an Attribute of the Sustainable Development of Pharmaceutical Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Peiró, J.M. Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to Promote Sustainable Development and Healthy Organizations: A New Scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, I.; Gulzar, F. Thrive, Don’t Survive: Building Work-Life Balance with Family Support, Grit and Self-Efficacy. IIMT J. Manag. 2025, 2, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madero-Gómez, S.M.; Rubio Leal, Y.L.; Olivas-Luján, M.; Yusliza, M.Y. Companies Could Benefit When They Focus on Employee Wellbeing and the Environment: A Systematic Review of Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehbi, A.; Farmanesh, P.; Solati Dehkordi, N. Nexus Amid Green Marketing, Green Business Strategy, and Competitive Business Among the Fashion Industry: Does Environmental Turbulence Matter? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanesh, P.; Vehbi, A.; Solati Dehkordi, N. AI Literacy in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: The Interplay of Student Engagement and Anxiety Reduction in Northern Cyprus Universities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, E.; Tunca, S.; Cetinkaya, G.; Balcıoğlu, Y.S. Exploring the Roles of Work Engagement, Psychological Empowerment, and Perceived Organizational Support in Innovative Work Behavior: A Latent Class Analysis for Sustainable Organizational Practices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanesh, P.; Solati Dehkordi, N.; Vehbi, A.; Chavali, K. Artificial Intelligence and Green Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Competitive-Advantage Drive Toward Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Mollah, M.A.; Choi, J. Sustainability and Organizational Performance in South Korea: The Effect of Digital Leadership on Digital Culture and Employees’ Digital Capabilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, T.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, R.; Dias, Á.; da Costa, R.L. Sustainable Practices Impacting Employee Engagement and Well-Being. Prog. Ind. Ecol. Int. J. 2022, 15, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Çağlar, S. Contribution of Psychology to Sustainable Development Goals: A Bibliometric Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 9911–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Cooper, C.L. Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development in Organizations; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024; ISBN 9781000934083. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.; Wang, L. Introducing Entropy into Organizational Psychology: An Entropy-Based Proactive Control Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühner, C.; Hüffmeier, J.; Zacher, H. Environmental Sustainability at Work: It’s Time to Unleash the Full Potential of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2025, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Dyrka, S.; Kokiel, A.; Urbańczyk, E. Sustainable HR and Employee Psychological Well-Being in Shaping the Performance of a Business. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.J.; Khawaja, S. Sustainable Leadership Impact on Environmental Performance: Exploring Employee Well-Being, Innovation, and Organizational Resilience. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, M.S.; Anggara, S.; Yuniarsih, T.; Sobandi, A. Strategic Planning and Organizational Performance in Food Business: The Role of Organizational Trust and Pandemic Planning. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2024, 43, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Sustainable Leadership, Environmental Turbulence, Resilience, and Employees’ Wellbeing in SMEs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 939389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable Leadership Practices for Enhancing Business Resilience and Performance. Strategy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Singh, S.; Mikkilineni, S.; Ribeiro, N. A Positive Psychological Approach for Improving the Well-Being and Performance of Employees. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024, 73, 2883–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, B. Responsibility Driving Innovation: How Environmentally Responsible Leadership Shapes Employee Green Creativity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, Z.; Sutton, A.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D. Environmental Sustainability and the Happy-Productive Worker: Examining the Impact on Employee Well-Being and Work Performance in Educational Institutions. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2025, 39, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel-Fitzgerald, C.; Millstein, R.A.; Von Hippel, C.; Howe, C.J.; Tomasso, L.P.; Wagner, G.R.; Vanderweele, T.J. Psychological Well-Being as Part of the Public Health Debate? Insight into Dimensions, Interventions, and Policy. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khayat, M.; Halwani, D.A.; Hneiny, L.; Alameddine, I.; Haidar, M.A.; Habib, R.R. Impacts of Climate Change and Heat Stress on Farmworkers’ Health: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 782811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinaccio, A.; Gariazzo, C.; Taiano, L.; Bonafede, M.; Martini, D.; D’Amario, S.; de’Donato, F.; Morabito, M.; Worklimate Working Group. Climate Change and Occupational Health and Safety. Risk of Injuries, Productivity Loss and the Co-Benefits Perspective. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidance for Climate-Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutar, C.; Wand, A.P.F. Understanding the Spectrum of Anxiety Responses to Climate Change: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Greenberg, N. Climate Change Effects on Mental Health: Are There Workplace Implications? Occup. Med. 2023, 73, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sario, M.; de’Donato, F.K.; Bonafede, M.; Marinaccio, A.; Levi, M.; Ariani, F.; Morabito, M.; Michelozzi, P. Occupational Heat Stress, Heat-Related Effects and the Related Social and Economic Loss: A Scoping Literature Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1173553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, S.; Ondoa, H.A. Climate Shocks and the Labour Market in Sub-Saharan Africa: Effects on Youth Employment and the Reallocation of Labour Supply. Int. Labour Rev. 2025, 164, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, K.; Benner, A. The Racialized Landscape of COVID-19: Reverberations for Minority Adolescents and Families in the US. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 52, 101614. [Google Scholar]

- Sunny, C.T.T.; Muttungal, P.; Davidson, B.G. Greening the Workplace: Can Sustainable Practices Reduce Anxiety and Enhance Meaningful Work Engagement? Northeast J. Complex Syst. (NEJCS) 2025, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A.; Eweje, G.; Raziq, M.M. Sustainability Leadership: An Integrative Review and Conceptual Synthesis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 2849–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Lee, S.W.; Xu, J. Role of Organizational Resilience and Psychological Resilience in the Workplace—Internal Stakeholder Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Fried, Y. Work Orientations in the Job Demands-Resources Model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.; More, T.; Chair, B.; College, B.; Fink, D. The Seven Principles of Sustainable Leadership. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 61, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J. Towards a New Concept of Residential Well-Being Based on Bottom-up Spillover and Need Hierarchy Theories. In A Life Devoted to Quality of Life: Festschrift in Honor of Alex C. Michalos; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 60, pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S. The Causes and Consequences of a Need for Self-Esteem: A Terror Management Theory. In Public Self and Private Self; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S.; Greenberg, J. Thirty Years of Terror Management Theory: From Genesis to Revelation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 52, pp. 1–70. ISBN 9780128022474. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HO, H.C.Y. A One-Year Prospective Study of Organizational Justice and Work Attitudes: An Extended Job Demands-Resources Model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2025, 40, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Yuan, Y. Evolving the Job Demands-Resources Framework to JD-R 3.0: The Impact of after-Hours Connectivity and Organizational Support on Employee Psychological Distress. Acta Psychol. 2025, 253, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Mansouri, M.; Santisi, G.; Zammitti, A. Psychological Flexibility as a Resource for Preventing Compulsive Work and Promoting Well-Being: A JD-R Framework Study. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 33, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; Hussain, S. Towards a Sustainable Workforce: Integrating Workplace Spirituality, Green Leadership, and Employee Adaptability for Green Creativity. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udin, U.; Fitriani, K.; Dananjoyo, R. Linking Empowering Leadership and Work Environment with Employee Performance: The Mediating Role of Job Stress. WORK 2025, 81, 2415–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winarno, A.; Gadzali, S.S.; Kisahwan, D.; Hermana, D. Leadership and Employee Environmental Performance: Mediation Test from Model Job Demands-Resources Dan Sustainability Perspective in Micro Level. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2442091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuchamy, V.; Palanichamy, T. Unravelling the Knots: A Narrative Review on Eco-Anxiety, Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Mental Health. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 12, 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, M.; Gousse-Lessard, A.-S.; Legris, N.H. Towards a Unified Conceptual Framework of Eco-Anxiety: Mapping Eco-Anxiety through a Scoping Review. Cogent Ment. Health 2025, 4, 2490524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Yang, X.; Can, M. Natural Resources Depletion, Financial Risk, and Human Well-Being: What Is the Role of Green Innovation and Economic Globalization? Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 167, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, H.U.H.; Khan, S.N. Linking Green Transformational Leadership and Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Role of Intention and Work Environment. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Li, W.; Mavros, C. Transformational Leadership and Sustainable Practices: How Leadership Style Shapes Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, C.; Zhang, J.; Akhtar, M.N. Positive Leadership and Employees’ pro-Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 31405–31415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeske, J. Leadership towards Sustainability: A Review of Sustainable, Sustainability, and Environmental Leadership. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Boechat, A.C. How Sustainable Leadership Can Leverage Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; ud Din, M.; Khan, M.F.; Almurad, H.M.; Hasnin, E.A.H. Unleashing the Power of Green HR: How Embracing a Green Culture Drives Environmental Sustainability. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencsik, A.; Berke, S. Sustainable Leadership in Practice in Hungary. In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, London, UK, 23–24 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, L.M.S.; De Melo Heizen, D.A.; Verdinelli, M.A.; Cauchick Miguel, P.A. Environmental Performance Indicators: A Study on ISO 14001 Certified Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, G.; Ortega, E.; Semedo, A. Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.R.; Malik, F.; Khan, M.R.; Khan, I.; Ghouri, A.M. Organizational Sustainability: The Role of Environmentally Focused Practices in Enhancing Environmental Performance—An Emerging Market Perspective. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Xing, L. The Impact of Green Culture on Employees’ Green Behavior: The Mediation Role of Environmental Awareness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y. Eco-Leadership in Action: Integrating Green HRM and the New Ecological Paradigm to Foster Organizational Commitment and Environmental Citizenship in the Hospitality Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, B.F.; Ghias, W.; Mahmood, S. Sustainable Leadership’s Impact on Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Employee Green Behavior and the Moderating Influence of Environmental Knowledge. Rev. Appl. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2025, 8, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resanovich, S.L.; Hopthrow, T.; de Moura, G.R. Growing Greener: Cultivating Organisational Sustainability Through Leadership Development. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawter, L.; Garnjost, P. Green Human Resource Management and Organizational Performance: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makumbe, W. Green Human Resources Management and Green Performance: A Mediation–Moderation Mechanism for Green Innovation and Green Knowledge Sharing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Iqbal, Q. Sustainability-Focused Leadership and pro-Environmental Behavior in SMEs: Through the Lens of Conservation of Resources Theory. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Akdemir, M.A.; Kara, A.U.; Sagbas, M.; Sahin, Y.; Topcuoglu, E. The Mediating Role of Green Innovation and Environmental Performance in the Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Bhullar, N. Eco-anxiety: How Thinking about Climate Change-related Environmental Decline Is Affecting Our Mental Health. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 1233–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Newman, D.B. Eco-Anxiety in Daily Life: Relationships with Well-Being and pro-Environmental Behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Ramish, M.S. Predictive Effect of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Change Anxiety towards Mental Health Problems and Psychological Well-Being among Entrepreneurs. OBM Neurobiol. 2024, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayassamy, P.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Workplace Eco-Anxiety: A Scoping Review of What We Know and How to Mitigate the Consequences. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1371737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, M.; Valdrighi, G.; Guazzini, A.; Duradoni, M. Eco-Sensitive Minds: Clustering Readiness to Change and Environmental Sensitivity for Sustainable Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becht, A.; Spitzer, J.; Grapsas, S.; van de Wetering, J.; Poorthuis, A.; Smeekes, A.; Thomaes, S. Feeling Anxious and Being Engaged in a Warming World: Climate Anxiety and Adolescents’ pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 65, 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, Z.; Brown, S.; Kelly, M. Understanding Climate Anxiety and Potential Impacts on Pro-Environment Behaviours. J. Anxiety Disord. 2025, 114, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, Z.; Kelly, M.; Brown, S. The Relationship between Climate Anxiety and Pro-Environment Behaviours. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, F.; Fernández de la Cruz, L.; Wahlund, T.; Andersson, E.; Åhlén, J.; Fuso Nerini, F.; Akay, H.; Mataix-Cols, D. Climate Worry: Associations with Functional Impairment, pro-Environmental Behaviors and Perceived Need for Support. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Wu, Q.; Bi, C.; Deng, Y.; Hu, Q. The Relationship between Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Future Self-Continuity and the Moderating Role of Green Self-Efficacy. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, K.; Williams, E. The Resilient Effects of Transformational Leadership on Well-Being: Examining the Moderating Effects of Anxiety during the COVID-19 Crisis. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, I.; Rahardjo, K.; Abdillah, Y.; Riza, M.F. The Influence of Sustainable Leadership, Organizational Culture, and Digital Marketing on Sustainable Performance: A Study on Tourism Sector Companies in Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-1744-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretzko, D.; Siemund, K.; Sterner, P. Evaluating Model Fit of Measurement Models in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2024, 84, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Al-Khaldy, D.A.W.; Anas, A.M.; Alrefae, W.M.M.; Salama, W. Impact of Green Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Environmental Performance in the Hotel Industry Context: Does Green Work Engagement Matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althnayan, S.; Alarifi, A.; Bajaba, S.; Alsabban, A. Linking Environmental Transformational Leadership, Environmental Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Organizational Sustainability Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Kar, J.; Bagchi, E.; Mukhopadhyay, U. Eco-Anxiety in Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health. In Climate Crisis, Social Responses and Sustainability: Socio-Ecological Study on Global Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Part F2915; pp. 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Watsford, C.R.; Walker, I. Clarifying the Nature of the Association between Eco-Anxiety, Wellbeing and Pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.A.; Lutz, P.K.; Howell, A.J. Eco-Anxiety: A Cascade of Fundamental Existential Anxieties. J. Constr. Psychol. 2023, 36, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Aruta, J.J.B.R.; Aylward, B.; Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.; Berry, H. A Global Perspective on Climate Change and Mental Health. In Climate Change and Mental Health Equity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From Anger to Action: Differential Impacts of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Depression, and Eco-Anger on Climate Action and Wellbeing. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Gao, C.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, M. Can Empowering Leadership Promote Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behavior? Empirical Analysis Based on Psychological Distance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 774561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mughal, M.F.; Cai, S.L.; Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behavior: Mediating Role of Green Self Efficacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Allen, A.; Schaffer, V.; Kannis-Dymand, L. Nature Relatedness May Play a Protective Role and Contribute to Eco-Distress. Ecopsychology 2024, 16, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.L. The People Paradox: Self-Esteem Striving, Immortality Ideologies, and Human Response to Climate Change. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M.; Perramon, J.; Bagur-Femenias, L. Leadership Styles and Corporate Social Responsibility Management: Analysis from a Gender Perspective. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).