Abstract

Soil degradation threatens agricultural sustainability by impairing soil structure, hydrological function, and ecosystem services. While conservation tillage and cover cropping have been extensively studied, the role of perenniality remains underexplored, particularly regarding its impacts on soil physical and hydraulic properties. This review addresses three key objectives: (1) assessing the effects of perenniality on soil structure and hydrology, (2) synthesizing its contributions to water quality, soil conservation and climate mitigation, and (3) identifying barriers to its adoption in agricultural systems. This study synthesized over two decades of interdisciplinary evidence from peer-reviewed literature across diverse agroecosystems to understand how perennial crops influence soil systems. Findings indicate that perennial crops restore soil structure through continuous root activity and organic matter inputs, enhancing aggregate stability, reducing compaction, and stabilizing pore networks. These structural improvements enhance water infiltration capacity, increase soil water retention, and reduce erosion, thus contributing to improved water quality and climate mitigation through reduced nutrient losses and greater carbon sequestration. Despite these benefits, perenniality adoption is constrained by agronomic, economic, and policy barriers. Continued long-term, multidisciplinary research is essential to guide management decisions and support broader adoption of perennial agriculture.

1. Introduction

Soil degradation represents one of the most critical environmental challenges of the 21st century, affecting approximately 24% of the global land area—equivalent to nearly 35 million square kilometers [1]. Soil degradation leads to the deterioration of its physical, chemical, and biological properties, thereby limiting agronomic productivity. It may result from multiple interacting stressors such as compaction, acidification, waterlogging, erosion, and nutrient deficiencies that operate concurrently or in succession. In interaction with topographic and climatic factors, it compromises ecosystem function and ultimately jeopardizes long-term food security. The primary drivers of soil degradation include rapid population growth, widespread deforestation, industrial expansion, urban sprawl, unsustainable farming practices and the escalating effects of climate change all of which undermine soil health and functionality [2]. Globally, conventional plow-based agricultural practices result in soil erosion rates that are 1–2 orders of magnitude greater than rates of natural soil formation, erosion under native vegetation, and long-term geological erosion [3]. Worldwide, an estimated 75 billion tons of fertile topsoil are lost each year from agricultural lands due to erosion, with approximately 80% of the world’s agricultural land experiencing some degree of soil erosion—from mild to severe [4]. In the United States, while soil erosion rates declined by 34% between 1982 and 2007, they still far exceed the natural rate of soil regeneration from parent material. As a result, much of the nation’s cropland continues to lose soil faster than it can be replenished, leading to significant productivity losses estimated at $37.6 billion annually in the U.S. and around $400 billion globally [4,5]. Although the erosion process removes nutrient-rich topsoil and transports sediment-bound nutrients into water bodies, it represents just one aspect of the broader soil degradation crisis.

Other detrimental processes such as soil compaction through heavy machinery, excessive nitrogen fertilization leading to acidification, and the depletion of organic matter from intensive tillage can also impair soil structure, reducing its capacity to infiltrate and store water, cycle nutrients, and sustain microbial life [6,7,8]. These degradation processes are further exacerbated by land-use changes, particularly the conversion of perennial ecosystems such as grasslands and forests to annual cropping systems, which disrupt soil hydro-physical conditions, long-term soil stability and amplify losses in organic carbon, biodiversity, and hydrological function. A striking example of this degradation is observed in the widespread conversion of perennial grasslands to annual croplands across the U.S. Between 2008 and 2012, grasslands accounted for 77% of all land converted to cropland, leading to the conversion of 5.7 million acres [9]. The consequences of this shift are profound. Zhang et al. [10] found that between 2008 and 2016, the transformation grasslands to croplands in U.S. Midwest led to environmental consequences, including a 7.9% rise in soil erosion, 3.7% more nitrogen loss, and increased soil organic carbon (SOC) loss by 5.6%. In Illinois, long-term prairie-to-cropland conversion over 167 years depleted SOC stocks by up to 50% [11], while in Minnesota, just two years of cultivation after grassland conversion reduced SOC by 18.6 Mg ha−1 in the top one meter of soil and significantly reduced water infiltration rates and soil sorptivity [12]. Such rapid deterioration in soil properties weakens agricultural resilience and also intensifies non-point source pollution.

The extensive use of chemicals (fertilizers and pesticides) in agriculture is recognized as a major contributor to water pollution [13]. Nutrients, heavy metals and chemical pollutants from non-point sources (e.g., runoff from agricultural fields) often bind to eroded soil particles and are transported into aquatic systems, increasing sediment loads and contributing to eutrophication of water bodies. In the U.S. Midwest, nutrient losses from croplands are particularly pronounced in systems dominated by annual crops such as corn (Zea mays L.), due to its intensive nutrient requirements and significant water movement across the landscape during the non-growing season in temperate regions [14]. The increasing cultivation of corn has been associated with higher risk of phosphorus export to marine environments [14]. Intensified corn cultivation in the Upper Mississippi River Basin has been associated with increased risks of phosphorus and nitrogen delivered to the basin's outlet [15]. In a 55-year analysis, Paudel and Crago [16] assessed the effects of nitrogen fertilizer application on U.S. water quality, revealing that a doubling of nitrogen fertilizer use in the Lower Mississippi water resource region increases the size of the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico by approximately 8777 km2 accounting for nearly 40% of the total area of the dead zone. Given these systemic consequences of soil degradation from diminished soil quality and agronomic productivity to aquatic ecosystem collapse, there is an urgent need to transition from conventional, extractive practices to regenerative agricultural systems that rebuild soil health and restore soil functionality. While conservation agricultural approaches (e.g., conservation tillage, cover cropping, crop diversification, crop-livestock integration, crop residue retention, organic amendments such as manure, compost, biochar and biosolids applications) provide important protection against soil degradation, complementing these approaches with perennial vegetation systems offers unique advantages for regenerating soil health.

Perennial vegetation systems, encompassing perennial grains, agroforestry, pasture systems, and native prairie integrations, offer a transformative solution to soil degradation by maintaining continuous living roots and ground cover. Perennial species exhibit multi-year life cycles characterized by repeated vegetative growth and reproductive phases across seasons. Once established, they can be harvested annually over several growing seasons without the need for replanting. This biological persistence enables perennial crops to produce harvestable yields annually while maintaining continuous living root systems. Unlike annual cropping systems that necessitate frequent soil disturbance, perennials leverage deep root architectures to stabilize soils, access subsoil nutrients (from up to 2.5 m depth), and create biopores that enhance water infiltration [17,18]. Their extended growing seasons and higher root-to-shoot ratios contribute greater carbon inputs to soils compared to annuals [19], increase biomass of soil microbial communities [20], reduce soil loss by 69% [21], while simultaneously reducing nitrate leaching [22]. These traits directly address the interconnected crises of erosion, SOC loss, and water pollution documented in intensive annual systems. When integrated as buffer strips, cover crops, biofuel crops or dual-use forage systems, perennials create spatial and temporal continuity that mimics natural ecosystems. For the purpose of this review, ‘perenniality’ is defined as growing plant species that persist for multiple growing seasons without annual replanting, maintaining continuous living roots in the soil. Globally, there is growing momentum towards integrating perennial species into agricultural systems to enhance long-term sustainability, resilience, and ecological function [23,24]. Despite increased attention to perenniality, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding their effects on soil physical and hydraulic properties and the ecosystem services they provide. A deeper understanding of these interactions is essential for optimizing soil function and harnessing the full potential of perennial-based systems. Therefore, this review aims to: (1) synthesize current evidence on how perenniality influences key soil physical and hydraulic properties; (2) evaluate the role of perennial systems in improving water quality and mitigating climate change; and (3) identify persistent barriers to the broader adoption of perennial-based cropping systems.

2. Methodology

A comprehensive search for peer-reviewed studies on responses of soil physical and hydraulic attributes to perenniality was deployed. The Web of Science and Google Scholar databases were searched for relevant literature published from 1997 to 2025 using topic terms and keywords. Search terms included combinations of “perennial crops”, “perennial agriculture”, “perenniality”, “perennial grasses”, “bioenergy crops”, “soil physical properties”, “soil hydraulic properties”, “water retention”, “water infiltration”, “bulk density”, “soil organic carbon”, “total nitrogen”, “aggregate stability”, “soil pores”, “porosity”, “soil health”, “annual crops”, and “ecosystem services”. To identify additional relevant research, reference lists of key articles and review papers were screened manually. Only peer-reviewed journal articles published in English language were considered. Studies were included if they examined the effects of perennial vegetation or perennial–annual comparisons on soil physical and hydraulic properties. Experimental designs included long-term field trials, short-term field and observational studies directly addressing soil responses to perennial systems. Exclusion criteria removed studies that: (i) were not peer-reviewed; (ii) focused solely on plant physiology without soil-related outcomes; (iii) investigated horticultural and woody perennial crops (e.g., orchards, agroforestry, and silvopastoral systems); (iv) lacked sufficient methodological detail; or (v) addressed perenniality only conceptually without empirical results. Although the integration of short-term non-perennial crops (e.g., in crop rotation or as cover crops) contributes to crop diversification and soil benefits, these systems fall outside the scope of this review. Additionally, the term ‘perenniality’ in this review does not imply complete replacement of annual crops, but rather encompasses both systems that compare perennial and annual crops, as well as those that integrate perennials into annual cropping systems. All included studies were evaluated for relevance to soil physical quality and hydraulic behavior provision associated with perennial cropping systems. The resulting literature formed the basis for the synthesis presented in this review. Data on key soil variables including aggregate stability (water stable aggregates and mean weight diameter), bulk density, pore size distribution (macroporosity, coarse mesoporosity, fine mesoporosity, microporosity and total porosity), soil water movement (water infiltration rate and saturated hydraulic conductivity), soil water retention (water contents at saturation [θSAT], field capacity [θFC], permanent wilting point [θPWP]), plant available water, SOC and TN were extracted from the selected literature to quantify the impact of perenniality on these variables. Data were sourced directly from published tables and text or, when necessary, digitized from figures using the open-source software Plot Digitizer (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net). The percentage change for each variable associated with perenniality was calculated. The compiled dataset was subsequently categorized based on soil texture, and results were summarized by the magnitude of change for each variable with perenniality. Visualizations were generated using the ggplot2 package Wickham et al. [25] in R. This review first examines the influence of perenniality on soil attributes such as aggregation, bulk density, and porosity and hydraulic functions including infiltration, saturated hydraulic conductivity, water retention, and SOC and TN (Section 3). These findings are discussed in the context of underlying biological and physical explanatory mechanisms, along with critical gaps in literature. Section 4 links improvements in soil function to ecosystem services, focusing on water quality enhancement and climate change mitigation potential. Section 5 addresses socio-economic and agronomic constraints that limit perennial system adoption at a large scale, and Section 6 and Section 7 present conclusions and future perspectives, respectively.

3. Impacts of Perenniality on Soil Physical and Hydraulic Attributes

3.1. Soil Aggregate Stability

Perenniality plays a crucial role in enhancing soil aggregate stability, which is fundamental for maintaining soil physical quality and ecosystem function. Highly stable aggregates resist decomposition, thereby enhancing long-term carbon storage and preserving soil structure [26]. This stability plays a critical role in creating a favorable environment for root growth and microbial activity, which further supports aggregate formation. Perennial root systems penetrate deeper into the soil, promoting the formation of stable aggregates through the physical binding of soil particles and the biochemical processes facilitated by root exudates. A comprehensive dataset of studies reporting water-stable aggregates and mean weight diameter under perennial and comparison systems was compiled and reported as Supplementary Table S1. In this review, 21 out of 25 studies found that perennial crops improved soil aggregation, while two found mixed effects (positive or neutral) and two found no effect (Table S1). Perenniality consistently improved soil aggregate stability across all soil textures (Table 1). Water-stable aggregates and mean weight diameter increased with perenniality, with percentage increases ranging from 6% to over 400%. The most pronounced and frequent improvements were observed in silt loam soils. Very few studies reported no significant change in soil aggregation with perenniality [27], but no studies reported a decrease in aggregate stability. Most studies focused on fine- and medium-textured soils, with relatively few examining coarse-textured soils. This highlights the need for more comprehensive research across different soil textural classes to better understand how perenniality influences soil aggregate properties.

Table 1.

Impact of perenniality on water stable aggregates and mean weight diameter across different soil textures.

Experimental evidence from long-term trials provides further support for the positive effects of perenniality on soil structure. Soils under perennial crops tend to have larger and more stable aggregates compared to those under annual or fallow systems. Ghosh et al. [45] studied the long-term (15 yr.) effects of perennial grasses on soil quality and found that the mean weight diameter (MWD) of aggregates significantly increased by 70% compared to the no grass cover with continuous cultivation, indicating improved soil aggregation and stability. They also noticed higher percentage of water stable aggregates from perennial grass treatments. Bonin and Lal [52] reported that soils under switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) and willow plantation had 50% more large macroaggregates and fewer small microaggregates than that under corn. Similarly, other researchers observed increases in aggregate stability with perenniality [33,35,40,53]. The formation of soil aggregates is enhanced in perennial systems due to the abundant microbial biomass in the rhizosphere, and high amounts of polysaccharide and root exudates which act as binding agents, along with the enmeshing action of grass roots and their associated mycorrhizal hyphae [54]. In addition to root contributions, soil fauna such as earthworms act as ecosystem engineers, significantly influencing aggregate formation through their burrowing and casting activities. Studies have shown that perennial crops support greater earthworm abundance and diversity due to reduced soil disturbance, continuous organic matter inputs, and stable microclimates. For example, Emmerling et al. [55] reported higher biomass and diversity of earthworm populations under perennial energy crops compared to annual silage corn across nine sites in Germany. Similarly, Forster et al. [56] found that perennial intermediate wheatgrass (IWG) supported significantly greater earthworm abundance, biomass, and diversity compared to annual wheat across sites in Europe. These findings, along with reports from Hoeffner et al. [57] and Rodriguez et al. [58], highlight the consistent positive impact of perennial systems on earthworm communities. Furthermore, continuous cover provided by perennial crops also reduces soil disturbance, further contributing to the stability of soil aggregates and minimizing erosion risks.

3.2. Bulk Density

Perenniality can significantly influence soil bulk density by reducing compaction and improving soil structure, although results vary depending on management practices and site conditions. Soil bulk density is a key indicator of compaction, with lower values generally reflecting improved soil structure and reduced compaction. Optimal bulk density for crop production varies by both natural factors such as soil texture, mineral composition, depth, and human activities, including land use and crop management. Compacted soils are known to hinder water, air, and heat flow; limit nutrient and water uptake; restrict root development; and ultimately reduce crop yields [59]. Integrating perennial crops into crop rotations can influence bulk density (Figure 1) and soil compaction. Table S2 summarizes findings from 48 studies examining the effects of perenniality on bulk density. Of these, 31 reported a reduction in bulk density, 3 reported an increase, 9 found no effect, and 5 showed mixed effects (either a decrease or no change). Some studies reported reductions in bulk density primarily in the upper soil layers following the inclusion of perennial crops [60,61]. The majority of studies across all soil textures showed a decrease or no change in bulk density with perenniality, with reductions of up to 34% (Table 2). Soils with sandy loam and silt loam textures most consistently exhibited these improvements. The reduction of soil bulk density in perennial systems is a result of synergistic effect of biological and physical processes (Figure 1). The development of deep, extensive root systems physically displace soil particles during growth. As these roots senesce and decompose, they leave behind persistent, tubular macropores (biopores) that form stable, continuous voids within the soil matrix [62]. Perennial plant systems are more effective at establishing stable and continuous biopores compared to annual systems [63]. Their roots are more adept at penetrating compacted soil due to their thick and deep rooting ability [64]. Concurrently, the continuous input of labile soil carbon from root exudates prime microbial activity [65]. This enhances microbial biomass, and shifts the community towards a higher fungal:bacterial ratio [66]. Mycorrhizal fungi hyphae enmesh soil particles, which are then cemented together by bacterial gums and root mucilages to form water-stable aggregates. This reorganizes the soil fabric from a compacted, massive state into a porous, granular one, wherein the pore space exists between these aggregates. Thus, the reduction in bulk density is fundamentally a transition from a particle-dense arrangement to an organo-mineral complex defined by its structural porosity, engineered by the sustained biological activity of the perennial system.

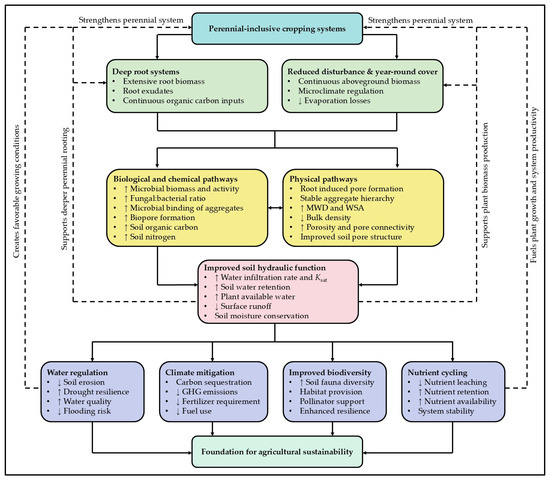

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating mechanisms and feedbacks linking perenniality with soil structural improvements, hydrological function, and ecosystem services. Solid arrows indicate the direction of influence and dashed arrows represent feedback loops. MWD = Mean weight diameter, WSA = Water stable aggregates, Ksat = Saturated hydraulic conductivity.

Table 2.

Impact of perenniality on soil bulk density across different soil textures.

While perenniality often reduces bulk density, this outcome is not consistent across all studies. Alagele et al. [93] studied the effects of switchgrass and agroforestry buffers on soil properties and found significantly lower bulk density compared to row crops (corn and soybean). Several researchers have reported reduction in bulk density with perennial crops such as Old World bluestem (Bothriochloa bladhii), alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and switchgrass, super Napier fodder [67,98,99]. This reduction in bulk density is attributed to continuous root growth and organic matter accumulation, which help maintain soil structure and prevent compaction. Benjamin et al. [63] evaluated the long-term effects of cropping intensity on soil physical conditions on a silt loam soil in Colorado and reported that soils under perennial grass management experienced a more rapid and large decline in bulk density compared to annually cropped systems and attributed it to increased pore volume. However, the relationship between cropping systems and bulk density is not uniform, as management practices and site-specific conditions can lead to different outcomes. For example, Jokela et al. [37] reported higher bulk density in alfalfa-based systems compared to grain-based systems, linking it to infrequent tillage that failed to alleviate compaction on a silt loam soil in Wisconsin. Despite such variations, lower bulk density creates favorable conditions for root exploration within the soil profile, promoting healthier plant growth and overall soil health.

3.3. Pore Size Distribution

Perenniality influences soil pore size distribution by enhancing total porosity and macroporosity, although its effects on microporosity remain inconsistent. Soil pore size distribution is critical for regulating the movement and storage of water and gases within the soil. The arrangement and connectivity of pores influence essential physical and hydraulic processes at the soil–plant and soil–atmosphere interfaces, including diffusion, mass flow of water and nutrient uptake by plant roots [100]. Perennial cropping systems demonstrate significant potential to increase soil porosity (Figure 1), though their effects vary across pore size classes. A comprehensive dataset of studies reporting macroporosity, coarse mesoporosity, fine mesoporosity, microporosity and total porosity under perennial and comparison systems was compiled and reported in Supplementary Table S3. Perenniality significantly altered soil pore structure, primarily by enhancing larger pore fractions. Macroporosity showed increases or no significant changes with perenniality across different soil textures (Table 3). Coarse and fine mesoporosity also frequently increased, particularly in silt loam soils. In contrast, microporosity exhibited minimal change, with slight increases or decreases depending on soil texture. Total porosity increased with perenniality in most studies across textures, with the largest gains observed in loam and silt loam soils (Table 3).

Table 3.

Impact of perenniality on soil pore size distribution across different soil textures.

These observations align with broader evidence indicating that perennial systems generally enhance soil porosity, particularly macroporosity and total porosity, across a range of soil textures. Multiple studies show that perennials consistently improve macroporosity and total porosity compared to annual systems or bare soil. For instance, switchgrass increased total porosity in silty clay loam [98], while prairie grass mixture including Andropogon gerardi enhanced coarse and fine mesoporosity in silt loam soils [86,87]. Furthermore, McCallum et al. [103] investigated the effects of perennial pastures (lucerne and Phalaris aquatica) on soil structure and observed that the treatments significantly influenced pore size distribution, with perennial pastures leading to an increase in macroporosity. Phalaris resulted in a greater number of pores in the 0.3 mm size range, attributed to the higher density of roots in that diameter range. Lucerne formed stable network of biopores that persisted even after two cropping cycles following its removal, although the average pore size decreased with time [103]. A more recent study by Cercioglu et al. [90] examined the effects of biofuel crops (Miscanthus × giganteus and switchgrass) and cover crops on soil pore characteristics measured using computed tomography on silt loam soil. The findings revealed that soil under Miscanthus exhibited significantly higher macroporosity (0.049 m2 m−2) and a larger maximum pore area (89.70 mm2) compared to the row crops without cover cropping. Earlier research on native grasslands and restored prairies has also shown that perennial vegetation enhances soil profile characteristics, including total porosity, macroporosity, and coarse mesoporosity [93,95,96,98,101]. These studies attribute these enhancements in soil porosity to the deep root systems of perennial vegetation, increase in soil organic matter pool, extended growing seasons, and reduced soil disturbance [104]. However, some studies showed no significant changes in macroporosity [72,97]. Rachman et al. [94] reported that while coarse mesoporosity (60–1000 µm effective pore diameter) in switchgrass and corn systems was similar at the 0–10 cm depth, notable differences emerged at 10–20 cm, highlighting a combined influence of vegetation type and soil depth on pore size distribution in Iowa’s silt loam soils. Further, Bacq-Labreuil et al. [105] argued that the effect of perenniality on porosity and pore connectivity can vary depending on soil texture, increasing it in clay soil but potentially decreasing it in sandy soil, while increasing pore size diversity in both. In this review, the effects of perenniality on microporosity appeared variable. While Alagele et al. [93] reported increased microporosity under a Lotus corniculatus L., Bromus spp., and Agrostis gigantea Roth grass mixture compared to a corn-soybean rotation, other studies reported no significant changes in microporosity under perennial systems [60,94]. These findings collectively indicate that perenniality tends to improve total porosity and macroporosity, primarily through root-driven soil structural changes. However, the majority of studies report no significant changes in microporosity, suggesting that this pore size class may be less responsive to perennial management or more strongly influenced by site-specific factors such as soil texture, rooting depth, and plant species composition.

3.4. Water Infiltration

Perennial vegetation enhances water infiltration by improving soil structure and promoting the development of stable macropore networks. The improvements in soil physical properties directly translate to a significant influence on soil hydraulic properties, which govern water movement and storage in saturated and unsaturated soils. A comprehensive dataset of studies reporting water infiltration rate under perennial and comparison systems was compiled and reported as Supplementary Table S4. Table 4 shows the influence of perenniality on water infiltration by soil texture. Perenniality increased water infiltration, with changes ranging from 32% to 141% across different soil textures. However, no study reported a decrease in water infiltration with perenniality.

Table 4.

Impact of perenniality on water infiltration rate and saturated hydraulic conductivity across different soil textures.

Perennial vegetation generally leads to improved soil hydraulic properties compared to conventional or annual cropping systems. The denser and more stable macropore networks created by perennial roots as a result of improved soil aggregation facilitate increased water infiltration into the soil. Alfalfa roots, specifically, have been noted as important for increasing infiltration rates by reforming channels that might be destroyed by tillage in annual systems. For instance, Huang et al. [74] found that the soil water infiltration capacity was greatest in a seven-year-old alfalfa grassland, followed by four- and two-year-old grasslands, each significantly exceeding that of a corn field in a sandy clay loam soil under a temperate sub-humid climate. It was indicated that alfalfa cultivation enhanced soil infiltrability, with improvements becoming more pronounced with increase in grassland age. Similarly, Guo et al. [92] observed a 31.8% increase in the steady infiltration rate of alfalfa grassland compared to bare land on silt loam soil, attributing this improvement to root channels formed by decaying alfalfa roots, which enhanced soil water infiltration and availability under semi-arid conditions. A fourfold increase in water infiltration in a heavily compacted sandy loam soil by alfalfa was also reported by Meek et al. [110]. The presence of root channels also promotes preferential flow pathways, allowing water to move more rapidly into deeper soil layers. Zaibon et al. [108] measured water infiltration in a degraded silt loam soil in Missouri, using ponded infiltrometers and reported that switchgrass systems exhibited higher quasi-steady infiltration rates compared to row crop management. After 12 years of management on claypan soils, Jung et al. [42] observed that perennial cropping systems significantly increased water infiltration parameters compared to annual cropping systems. The enhancement in infiltrability likely results from the gradual formation of macropores such as root channels, desiccation cracks, and animal burrows, which typically develop over several years following the transition from cultivation to perennial grasses [111]. In alignment with this, Vaupel et al. [112] reported that perennial flower strips across 46 sites in Germany significantly increased earthworm densities, including a 2263% rise in epigeic species compared to adjacent croplands, underscoring the critical role of soil fauna in creating and maintaining macropore networks in perennial systems.

3.5. Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity

A comprehensive dataset of studies reporting saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) under perennial and comparison systems was compiled and reported as Supplementary Table S4. The impact of perenniality on Ksat was variable (Table 4). While the majority of studies showed improvement, a few reported no change in Ksat with perenniality [73,90]. A single decrease was reported in a sandy loam soil (Table 4). Perenniality has shown strong potential to improve Ksat, a key indicator of water movement in soils that exhibits both temporal and spatial variability [113]. To assess how land use influences this key hydraulic property, multiple studies have examined the effects of perennial cropping systems. Fifteen out of 23 studies found that perennial crops increased Ksat, while four found mixed effects (positive or neutral) and four found no effect (Table 4). Studies indicate that soils under perennial vegetation exhibit greater Ksat than those managed under annual cropping systems. For example, Rachman et al. [94] reported that switchgrass hedges improved Ksat to 668 mm hr−1—six times greater than that of the row crop systems (115 mm hr−1). The improvements in water transmission properties are largely influenced by the formation of continuous and well-connected pore networks, which are critical for water and air flow in soil. Singh et al. [32] observed that native grasslands with perennial grasses showed significantly higher connected porosity, connection probability, and macroporosity, which contributed to enhanced Ksat compared to corn–soybean systems. Similarly, Zaibon et al. [96] found that soils under switchgrass exhibited 73% higher Ksat than those under row crop management. In Michigan’s loamy soils, alfalfa roots increased Ksat by 57% [47]. Benjamin et al. [41] also reported that grass plots (a mix of smooth brome, pubescent wheatgrass, and alfalfa) had consistently greater Ksat at all measured depths (2–37 cm) than annually cropped plots under wheat–corn–millet or wheat–fallow rotations in a semi-arid climate, which was attributed to improved pore continuity. However, a few studies showed no effect of perenniality on Ksat [61,73,90], suggesting that responses can vary with site conditions, species composition, and management history. Overall, the evidence supports the potential of perenniality to improve soil hydraulic behavior, particularly by improving water movement through improved pore structure and increased soil permeability, which plays a vital role in reducing soil erosion risk and conserving both soil and water.

3.6. Soil Water Retention

A comprehensive dataset of studies reporting volumetric water content at saturation (θSAT), volumetric water content at field capacity (θFC), volumetric water content at permanent wilting point (θPWP), and plant available water (PAW) under perennial and comparison systems was compiled and reported as Supplementary Table S5. The impact of perenniality on soil water retention varied across soil textures (Table 5). Water content at saturation and θFC showed neutral to positive trends, with the most consistent increases in sandy loam soils (up to 30%). However, θPWP responses were mixed, particularly in silt loams where it frequently decreased with perenniality. Consequently, PAW generally increased from 13 to 73% across different soil textures (Table 5), demonstrating a key hydrological benefit of perenniality. Perennial-inclusive systems can significantly influence soil water retention by altering soil structure, porosity, and the distribution of water across different tensions. The structural improvements in soil pore networks not only facilitate rapid water transmission but also influence soil water retention, field capacity and plant available water. The ability of the soil to retain water is regulated by pore size distribution which can be altered with agricultural management practices. The total amount of water the soil can hold when all pores are filled, represented by θSAT, was generally found to be higher under perennial systems compared to annual systems, as observed in studies conducted in South Dakota [32], Texas [67], and Alberta [73]. This suggests that perennial systems may improve soil structure and increase total porosity. The amount of water retained in the soil after gravitational drainage, represented as θFC, was also reported to increase under perennials in some cases [67,77], while other studies showed no effect [87]. Abu [77] evaluated soil physical quality indicators on sandy loam soils under different long-term land uses, including perennial pasture grasses, continuous cultivation fields, and natural fallow. The study revealed that fields under continuous cultivation had the poorest soil physical quality, with the highest bulk density and lowest porosity, θFC, and available water capacity. In contrast, fields with perennial grasses exhibited significantly greater soil physical quality, with higher organic carbon, porosity, water retention, and Ksat, outperforming fields under continuous cultivation and, in some cases, natural fallow fields.

Table 5.

Impact of perenniality on volumetric water content at saturation (θSAT), volumetric water content at field capacity (θFC), volumetric water content at permanent wilting point (θPWP), and plant available water (PAW) across different soil textures.

Seobi et al. [97] studied the impact of grass and agroforestry buffer strips on an Alfisol and found that these treatments increased soil water storage by 9 mm and 11 mm, respectively, compared to a row crop system, primarily due to enhanced total and coarse mesoporosity. Further, Zaibon et al. [96] found that soil water content was generally higher under switchgrass compared to row crop management at higher water potentials, indicating that perennial vegetative management can improve soil water retention at potentials that are primarily influenced by soil structure and root activity. The permanent wilting point, the threshold below which plants can no longer access water, often decreased under perennials [61,87], suggesting reduced water retention at high tensions, while some studies showed mixed [77,93] or no effect [96]. Plant available water, calculated as the difference between θFC and θPWP, increased under perennial systems in the studies conducted in Nigeria [77] and India [45], suggesting better soil moisture conditions for plant growth. While these findings demonstrate how perennials influence water retention and availability in the rhizosphere, their impact on broader soil water dynamics, particularly water extraction patterns and recharge, varies across climates and plant species. For example, in a study on water balance involving perennial and annual bioenergy crops in a humid subtropical climate, Yimam et al. [115] found that soil water content under perennial grasses was generally lower than under biomass sorghum, especially at greater soil depths. Likewise, Ferchaud et al. [116] monitored soil water use by different perennial and annual energy crops for over seven years and found that perennials such as Miscanthus × giganteus and switchgrass captured a greater proportion of water from deeper soil layers compared to the annual crop Sorghum bicolor. Conversely, Gaiser et al. [117] reported that using alfalfa as a preceding crop promotes deeper and denser root development in subsequent spring wheat, improving its ability to access moisture from deeper soil layers during extended dry periods. The study concluded that incorporating alfalfa into crop rotations could serve as a cost-effective strategy for enhancing drought resilience. These contrasting findings underscore the importance of considering climate, species selection, and rooting depth when evaluating the effects of perennial vegetation on soil water dynamics.

3.7. Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen

A comprehensive dataset of studies reporting soil organic carbon (SOC) and total nitrogen (TN) under perennial and comparison systems was compiled and reported as Supplementary Table S6. Perenniality significantly enhanced SOC and TN across most soil textures (Table 6). For SOC, increases from 6% to 188% were observed, with the most consistent gains in silt loam and clay loam soils. TN followed a similar trend, with gains up to 211%. Some studies reported no significant change in SOC and TN with perenniality [73,118,119]. Overall, the data demonstrated a strong potential for perennial systems to boost soil carbon and nitrogen sequestration, with soil texture influencing the magnitude of the response. Perennial-inclusive systems have a significant impact on SOC and TN dynamics, generally enhancing their storage compared to annual cropping systems. Soil organic carbon plays a critical role in maintaining soil quality, agricultural productivity, and environmental quality, as it influences key physical, chemical, and biological properties, such as soil water retention, nutrient cycling, gas exchange, and root development [120]. Preserving and increasing SOC is greatly influenced by sustainable management practices, particularly maintaining adequate biomass inputs through crop residues or perennial vegetation. Wienhold and Tanaka [121] reported that converting perennial grass-legume systems to annual cropping led to a rapid loss of 1.25 Mg C ha−1 from the topsoil (0–5 cm depth) within just two growing seasons. Their study concluded that annual crop biomass inputs were insufficient to maintain SOC levels under any management strategy compared to retaining perennial vegetation on a loamy soil in North Dakota. Perennial vegetation, with its extensive root systems and continuous ground cover, has been shown to significantly enhance SOC accumulation compared to annual cropping systems. Most studies reported significant increases in SOC in various systems, e.g., switchgrass in loam and silt loam soils [71,122], alfalfa in silt loam [44], and Miscanthus × giganteus in sandy loam soils [123] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Impact of perenniality on soil organic carbon and total nitrogen across different soil textures.

Long-term studies have demonstrated that perennial grasses and agroforestry systems increase SOC stocks by promoting deeper carbon sequestration and reducing soil disturbance [88,138,139]. A 30-year study by Dietz et al. [140] on a silt loam soil found that while annual cash-grain systems lost SOC at a rate of 0.80 Mg C ha−1 yr−1, alfalfa-based systems showed slower carbon loss (0.54 Mg C ha−1 yr−1). Perennial systems like prairies and managed pastures, however, maintained stable SOC levels over the study period. Similarly, TN often increased with perenniality, particularly with legume-containing systems like alfalfa [37,44] and grass-legume mixtures [43,127]. Baldwin-Kordick et al. [141] reported that a diversified 4-year rotation (corn–soybean–oat–alfalfa) with cattle manure increased SOC by 29% and TN by 17% numerically over 15 years compared to a conventional corn–soybean system, highlighting the potential of extended rotations and perennial forages to enhance soil carbon and nitrogen storage. These findings align with a broader meta-analysis by King and Blesh [24], who evaluated 169 cropping systems across 27 sites and reported that perennial-inclusive rotations increased carbon inputs by 23% and SOC concentrations by 12.5% compared to grain-only systems. The study emphasized that functional diversity in rotations, particularly those incorporating perennials, enhances SOC primarily when it increases total carbon inputs, as these systems exploit temporal niches (e.g., extended growing seasons) that would otherwise remain unproductive [24]. In an earlier study, Liebig et al. [142] compared 42 paired switchgrass and cropland sites across the Northern Great Plains and Corn Belt and reported significantly higher SOC in switchgrass stands, particularly at 0–5 cm, 30–60 cm, and 60–90 cm depths. The differences were most notable in deeper layers due to switchgrass’s extensive root biomass below 30 cm. This deeper carbon storage is less vulnerable to mineralization, highlighting switchgrass’s potential for long-term SOC retention. Recent studies indicate that switchgrass cropping systems typically achieve SOC accumulation rates above 0.25 Mg C ha−1 yr−1, which exceeds the threshold needed for carbon neutrality in agricultural systems [143]. The accumulation of SOC is influenced by complex interactions among soil characteristics, topography, climate, and biological and management factors, with the duration of perennial establishment emerging as an important factor. For example, Ma et al. [144] found that while nitrogen application, row spacing, harvest frequency, and switchgrass cultivar had no effect on SOC in the first 2–3 years after establishment, a 10-year switchgrass cultivation led to SOC increases of 45% at 0–15 cm and 28% at 15–30 cm compared to adjacent fallowed soil, indicating that long-term perennial growth is essential to achieve meaningful carbon sequestration. However, recent studies highlight that SOC accrual under perennial systems can vary significantly depending on site-specific conditions. Perry et al. [145] found that, after 13 years of cultivation on a loamy soil in a humid continental climate, switchgrass did not lead to any change in surface soil carbon compared to corn, likely due to already elevated baseline carbon levels resulting from earlier manure applications. Similarly, in a 10 year field study on sandy loam soil under a temperate climate, Zong et al. [84] observed minimal differences in topsoil SOC between perennial tall fescue and annual crops, despite higher root biomass in the perennial system. This was attributed to greater SOC turnover driven by increased enzyme activity in perennial system. In this review, the responses of SOC and TN to perenniality varied by system and soil type as some studies reported no change in SOC [119,129] or TN [35,119] with perenniality (Table 6). In contrast, Chen et al. [146] found that tall fescue significantly increased both SOC and nitrogen at 0–20 cm depth in loamy sand soils while maintaining high biomass yield, though no consistent relationship emerged between biomass yield and soil carbon changes. These studies indicate that while perennials generally enhance SOC and TN, outcomes depend on interactions among root dynamics, soil texture, climate, microbial processes, management intensity, and duration of perennial cover. Overall, these findings suggest that perenniality has potential to serve as a sustainable land-use strategy for enhancing SOC and TN and mitigating climate change through improved carbon sequestration.

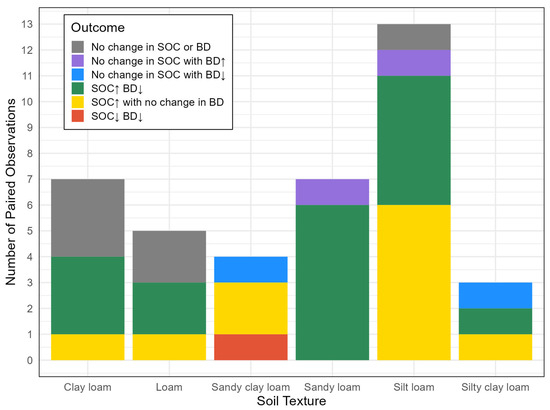

While these general patterns highlight the benefits of perenniality, the magnitude and direction of SOC and bulk density (BD) responses also vary with soil texture. Figure 2 illustrates texture-specific variation in the frequency and direction of paired SOC and BD responses to perenniality across studies (including only studies that reported both SOC and BD as response variables). The outcomes were categorized according to the direction of change in SOC and BD due to perenniality. Among the textures represented, silt loam soils exhibited the highest number of paired observations, with a mix of outcomes including SOC increases accompanied by either decreases or no change in BD. Loam and sandy loam soils also showed diverse responses, with both favorable (SOC↑, BD↓) and neutral outcomes. Silty clay loam soils had fewer paired observations, but SOC increases and BD reduction were still evident. Overall, Figure 2 demonstrates that the direction and magnitude of SOC and BD responses to perenniality differ among soil textures; however, all texture classes except sandy clay loam exhibited instances where increases in SOC were accompanied by reductions in BD, indicating that concurrent improvements in soil carbon and structure can occur with perenniality across a range of soil types.

Figure 2.

Distribution of paired soil organic carbon (SOC)-bulk density (BD) responses to perenniality across soil textures. Only studies that reported both SOC and BD as response variables are shown. Categories represent combinations of SOC-BD outcomes. ↑ = increase, ↓ = decrease.

4. Impacts of Perenniality on Water Quality, Soil Conservation and Climate Change Mitigation

4.1. Water Quality

Agricultural water quality is a critical factor in sustainable land management, as runoff and leaching from farmlands can transport sediments, nutrients, and agrochemicals into waterways and groundwater, contributing to both offsite downstream pollution and underground water contamination, ultimately leading to ecosystem degradation. Intensive annual cropping systems and monoculture, with frequent tillage and high fertilizer inputs, often exacerbate these issues by increasing soil erosion and nutrient leaching [14]. These concerns have led to growing interest in alternative cropping systems that can help improve water quality. A four-year study by McIsaac et al. [147] quantified inorganic nitrogen leaching under different cropping systems. The results showed that switchgrass and miscanthus reduced nitrate leaching by 96.5% and 92.5%, respectively, compared to a conventional corn-soybean rotation on a silt loam soil in Illinois. Likewise, Smith et al. [148] reported that perennial crops (miscanthus, switchgrass, and prairie) rapidly reduced nitrate leaching at a 50 cm soil depth, as well as nitrate concentrations and loads from tile drainage systems compared to corn-corn-soybean rotation. It was observed that within four years, tile nitrate concentrations declined from initial levels of 10–15 mg N L−1 to less than 0.6 mg N L−1 across all perennial crop treatments. Further evidence highlights the water quality benefits of diverse perennial systems. For instance, incorporating alfalfa into crop rotations significantly reduces nitrate leaching potential compared to continuous corn systems [22]. Similarly, a study by Studt et al. [149] measured N leaching under Miscanthus × giganteus and corn at two clay loam sites in Iowa and found that while juvenile Miscanthus (1–2 years old) showed similar leaching rates to corn, mature stands (3–4 years old) reduced N leaching by 42% and 88% compared to corn under fertilized and unfertilized conditions, respectively. The mechanisms behind reduced nitrogen loss could be reduced nutrient runoff, increased nitrogen uptake through longer growing seasons of perennial crops, increased arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization, or release of root exudates that inhibit nitrification [150]. More recently, Huddell et al. [151] reported reduced nitrate leaching in intermediate wheatgrass (IWG), with losses of 0.1–3.1 kg N ha−1 yr−1 in its third and fourth years, compared to 5.6 kg N ha−1 yr−1 in annual wheat and 41.0 kg N ha−1 yr−1 in fallow systems. These findings align with earlier work by Culman et al. [152], who observed that perennial Kernza® (IWG) reduced both soil moisture at lower depths and total nitrate leaching by 86% or more compared to annual wheat in its second growing season. It was concluded that perennial root systems more effectively utilize soil water and capture applied fertilizers. The remarkable efficiency of perennial systems is further supported by modeling studies; Jungers et al. [153] used the DNDC model to show that switchgrass and IWG could reduce annual nitrate leaching by 83% and 99%, respectively, when compared to conventional corn systems. Similarly, Schulte et al. [154] found that integrating prairie strips into cropping systems reduced total water runoff from catchments by 37%, while retaining 20 times more soil and 4.3 times more phosphorus compared to conventional corn and soybean systems. However, the water quality benefits of perennial systems may vary depending on system maturity and legacy nutrient effects. In early establishment years, perennial systems have been shown to leach more nitrate than annual crops [155], although nitrate losses decreased substantially over a 7-year period. Notably, Hunt et al. [156] found that while diversified rotations (3-year corn-soybean-oat/clover and 4-year corn-soybean-oat/alfalfa-alfalfa systems) reduced total nitrogen and phosphorus runoff by up to 39% and 30%, respectively, in comparison to a 2-year corn-soybean system, nitrate leaching losses showed no significant change among cropping systems. Furthermore, Hussain et al. [14] reported that phosphorus leaching rates showed no significant differences among various cropping systems (including no-till corn, hybrid poplar, switchgrass, miscanthus, native grasses, and restored prairie) over a seven-year period. It was observed that soil phosphorus stocks from previous agricultural practices (legacy phosphorus) may buffer against changes in leaching regardless of crop type. Nevertheless, the perennial cropping systems can offer significant long-term benefits for water quality by reducing nitrate leaching through deep root systems and extended growing seasons (Figure 1). While establishment-phase losses and persistent phosphorus challenges exist, mature perennials such as Miscanthus, switchgrass, and Kernza® consistently outperform annual crops in nutrient retention. Their integration into agricultural landscapes represents a sustainable solution for mitigating nutrient pollution, though site-specific management remains crucial for optimal results. Beyond their role in improving water quality, perennial crops also contribute significantly to soil conservation.

4.2. Soil Conservation and Erosion Control

Perennial crops provide substantial soil conservation benefits through multiple mechanisms that protect against erosion and degradation. Their year-round ground cover and deep, extensive root systems work synergistically to: (1) stabilize soil aggregates, (2) maintain continuous vegetative protection, and (3) enhance water infiltration, collectively reducing vulnerability to both water and wind erosion (Figure 1). Unlike annual tilled systems that experience regular soil disturbance, perennial vegetation forms a permanent protective barrier that intercepts raindrop impact and dissipates wind energy at the soil surface. These protective mechanisms have been quantified across various agroecosystems. Cosentino et al. [157] documented that alfalfa reduced annual soil loss by 97% and perennial giant miscanthus by 99% compared to a wheat-wheat-fallow rotation in Mediterranean environments. Similarly, Visconti et al. [158] reported that Arundo donax L. reduced soil losses by 78% relative to fallow, matching the erosion control capacity of permanent meadows through effective soil coverage during peak rainfall periods. Furthermore, Grunwald et al. [159] observed that cup plant and perennial grass systems reduced both water runoff and soil erosion to near-zero levels, while adjacent corn plots lost up to 1.5 Mg ha−1 year−1 of sediment. This was attributed to the perennial systems' enhanced infiltration rates and earthworm activity that improved soil structure. Modeling and field studies have consistently shown that perennial systems can significantly reduce soil and water losses. For example, a SWAT modeling study by Nelson et al. [160] in the Delaware Basin of northeast Kansas demonstrated that converting cropland to switchgrass reduced surface runoff by 55% and nearly eliminated edge-of-field erosion, achieving a 98% reduction. Another modeling study by Wang et al. [161] showed that replacing row crops with perennial warm-season grasses like switchgrass on sloped lands across the Midwest significantly reduced water runoff (by 3.2–12.1%) and soil loss (by 43.7–95.5%), with the greatest benefits on steeper slopes. These findings suggest that strategically planting switchgrass on marginal lands can enhance soil conservation while also providing economic benefits. Similarly, Osterholz et al. [162] showed that interseeding alfalfa into corn silage production reduced losses of total suspended solids by 49–87%, total nitrogen by 37–74%, and total phosphorus by 37–81% during rainfall simulations. Supporting these findings, Qin et al. [163] reported that alfalfa grasslands reduced soil loss by 50% and tripled soil retention capacity compared to annual cropland, largely due to an extended vegetative cover period of about 80 additional days each year. Furthermore, Helmers et al. [164] evaluated the effectiveness of prairie filter strips in reducing sediment loss using twelve small watersheds in central Iowa under corn-soybean rotation. Over a four-year period, watersheds with prairie filter strips had a mean annual sediment yield of 0.36 Mg ha−1, compared to 8.30 Mg ha−1 in those without prairie filter strips indicating a 96% sediment trapping efficiency. These benefits arise not only from the physical binding of soil by roots but also from their interaction with the soil biological community, driven by carbon inputs from root exudates and residues [165]. However, results from Acharya et al. [166] indicate that the effectiveness of perennial grasses in reducing runoff, sediment, and nutrient losses may be site-specific. On an eroded soil in southwestern Iowa, no differences in sediment and nutrient losses were observed between switchgrass and no-till corn, while at a pivot corner site in Nebraska, perennial grasses significantly outperformed corn, reducing sediment and phosphate losses by up to fivefold. These studies highlight the significant role of perennial vegetation in soil conservation. While prairie strips and deep-rooted grasses can dramatically reduce erosion, their performance depends on factors such as topography, soil type, and management history. Integrating perennial systems into agricultural landscapes with site-specific management particularly in erosion-prone areas can provide soil conservation benefits. In addition to enhancing soil conservation, perenniality offers climate-related co-benefits that are integral to sustainable land management strategies.

4.3. Climate Mitigation and Resilience

Perennial cropping systems offer promising pathways for mitigating climate change through enhanced carbon sequestration and reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Figure 1). While agroecosystems can contribute to climate adaptation by storing carbon in soils and biomass, they may also act as sources of GHGs due to practices such as fertilizer application and soil disturbance. Whether an agroecosystem functions as a net carbon sink or source depends on climatic factors (e.g., precipitation and temperature), non-climatic natural factors (e.g., soil property, landforms, and biomes), human-related agricultural management practices [167] and their interactions. The most profound mechanism is the enhanced drawdown and long-term storage of atmospheric carbon (Figure 1). Compared to annual or short-rotation systems, diverse perennial plant communities, with their deep and permanent root systems, typically store more carbon, especially when strategically placed in landscape positions that enhance carbon sequestration. Grassland vegetation, in particular, is effective in depositing organic matter deeper in the soil, where it is less susceptible to decomposition, allowing it to be sequestered for decades rather than being quickly released back into the atmosphere. Kim et al. [168] compared CO2 fluxes between a perennial rye system (Secale cereale L. × S. montanum Guss., cv. ACE-1) and an annual rye system (S. cereale L., cv. Gazelle). Their results showed that the perennial crop acted as a much stronger net sink for atmospheric carbon, with a growing-season net ecosystem CO2 uptake of 556 g C m−2 yr−1, compared with only 89 g C m−2 yr−1 in the annual system. Sainju and Allen [169] compared the carbon footprint and balance of perennial bioenergy crops (intermediate wheatgrass, smooth bromegrass, and switchgrass) with annual spring wheat and found that spring wheat losing more carbon as carbon dioxide (CO2) flux and remained carbon negative compared to perennial bioenergy crops. This demonstrates the substantially greater capacity of perennial vegetation to draw down and retain atmospheric CO2 within the agroecosystem.

Another operational mechanism is the substantial reduction in on-farm fossil fuel consumption. The perennial nature of crops eliminates the need for annual tillage, seeding, and other repetitive field operations required for annual systems. This reduces the number of tractor passes across the field, leading to a direct and significant drop in fuel combustion. Consequently, this lowers the associated CO2 emissions from farm machinery, making the entire production system less reliant on fossil fuels and more energy-efficient. Adler et al. [170] used life cycle analysis to quantify the net effect of perennial bioenergy cropping systems on GHG emissions and reported that ethanol and biodiesel from switchgrass reduced emissions by 115%, compared with 40% for corn, relative to the life cycle emissions of gasoline and diesel. These substantial GHG savings align with the findings of Whitaker et al. [171], who emphasized that the most favorable GHG balance for perennial crops is achieved through strategic management, such as cultivating those on low-carbon soils and applying conservative nutrient management, which also co-benefits water quality. Species identity and functional traits also influence sequestration outcomes, and several studies highlight how perennial systems can influence nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, a potent GHG, relative to annual cropping systems. For instance, a 3-year field study by Abalos et al. [172] in Ontario showed that a perennial grass-legume mix (Phleum pratense L. and alfalfa) emitted significantly less N2O (6 g N2O-N ha–1 d–1) than a corn monoculture (15 g N2O-N ha–1 d–1). The improved soil structure from higher root biomass and organic matter in the perennial system likely reduced anaerobic microsite formation, thereby reducing N2O production. Similarly, Christenson et al. [173] observed higher N2O emissions in continuous corn systems compared to switchgrass and smooth bromegrass treatments, largely due to the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. Likewise, a 94% reduction in perennial grains compared to annual grains was reported by Daly et al. [174]. This is consistent with findings by Drewer et al. [175], who reported that perennial bioenergy crops emit less GHGs than annual crops only when they receive little to no nitrogen fertilizer, further emphasizing the critical role of nutrient management in reducing emissions from perennial systems. Oates et al. [176] similarly found that cumulative N2O emissions over a three-year period were 142% greater in annual cropping systems compared to perennials, with fertilized perennials emitting 190% more N2O than the unfertilized. Perennial bioenergy crops during their establishment phase were found to emit less N2O than annual crops, particularly in the absence of fertilization. It was concluded that the extended active growth period of perennials can reduce the amount of residual nitrogen in the soil available for microbial conversion to N2O. Likewise, Sainju et al. [177] compared several perennial species, including intermediate wheatgrass, smooth bromegrass, and switchgrass, to spring wheat and found that intermediate wheatgrass notably reduced GHG emissions both per unit area and per unit of crop yield. While many studies support the climate benefits of perennials, findings are not always consistent. McGowan et al. [178] reported no significant differences in N2O emissions among annual and perennial crops in Kansas, though miscanthus generally had the lowest emissions. Similarly, Kemmann et al. [179] found no significant differences in N2 or N2O emissions between soil cores from cup plant and corn systems, indicating limited GHG mitigation potential under perennial biomass crops. On the other hand, Lee et al. [180] reported significantly higher cumulative N2O emissions from miscanthus soils than from corn, primarily due to high legacy nitrogen inputs, while contemporary nitrogen applications had no notable effect. Overall, while perennial systems may not universally reduce emissions, their integration into agricultural landscapes, especially when combined with conservation practices such as no-till or in rotation with annual crops, offers a promising strategy for enhancing carbon storage, reducing GHG emissions in the long term, and improving regional climate [181,182,183].

5. Challenges to Perenniality in Agricultural Systems

The inclusion of perennial crops in cropping systems encounters challenges related to crop management, financial feasibility, and prevailing policy structures, despite their potential to reduce soil degradation. Asbjornsen et al. [184] postulated that perennial vegetation can intensify pest issues by serving as an alternative host to the pests; e.g., buckthorn (Rhamnus spp.) in hedgerows can support soybean aphid populations near soybean fields in the Midwestern USA. Similarly, Soto-Gomez and Perez-Rodriguez [185] pointed out that perennial crops, including perennial wheat, can act as long-term reservoirs for diseases due to the inability to implement crop rotations as a pest management strategy. A deeper, species-specific understanding is needed to clarify how individual perennials affect pest dynamics and natural enemy populations and ultimately crop yields. In addition to pest and disease concerns, water management presents another limitation. Vico and Brunsell [186] noted that perennials often have variable water demands and lower water productivity than annuals, which may impact yield stability and water-use efficiency under changing climatic conditions. Similarly, Twerdoff et al. [187] observed that higher evapotranspiration from perennials led to greater depletion of surface soil moisture (0–7.5 cm) compared to annuals early in the growing season, though soil moisture levels between the two systems later became similar. Likewise, Entz et al. [188] reported that in Northern Great Plains region of U.S. and Canada, where water severely limits crop productivity, the inclusion of perennial forages into cropping systems can lower subsequent crop yields by depleting soil moisture. However, conservation tillage techniques can help partially address the negative impact of perennials in water-limited environments. Despite such challenges, studies have shown that perenniality can enhance crop yields under certain conditions. For example, Franco et al. [189] found that alfalfa and alfalfa–grass mixtures improved yields of no-till annual crops after at least two years, while de Camargo Santos et al. [190] reported that crop rotations including perennials consistently produced higher yields than both corn monocultures and corn–soybean rotations, and also mitigated yield losses commonly associated with transitions to no-till systems. While research demonstrates the potential of perennial systems to overcome agronomic limitations, their wider implementation faces significant structural hurdles particularly in economic and policy frameworks. Mosier et al. [191] identified global food demand as a key driver perpetuating annual cropping on degraded lands, while policy frameworks, particularly in the U.S., reinforce this trend through crop insurance programs that favor low-diversity, high-input systems over ecological management. The absence of robust markets for perennial crops, such as cellulosic bioenergy or diverse grain systems further discourages farmers leaving them with few economic incentives to transition away from conventional practices. These findings align with the observations of Mattia et al. [192], who reported that while some landowners are motivated to adopt multifunctional perennial systems for ecosystem benefits such as improved soil health and biodiversity, widespread adoption is hampered by weak economic incentives, limited technical knowledge, and underdeveloped markets. Government policies and regulations could play a pivotal role in overcoming these barriers, and aligning financial support with sustainable land management. Without significant policy reforms and market development, the transition toward perennial-based agriculture will remain slow, locking farmers into annual systems despite their long-term ecological drawbacks. Addressing these multifaceted barriers will require coordinated efforts across research, policy, and supply chains to make perenniality a viable alternative.

Recent policy analyses further expand on these structural needs. Scott et al. [193] postulated that a meaningful transition to perennial agriculture requires an integrated federal strategy that lowers financial risk for producers, rewards ecological benefits, builds market demand, and strengthens long-term research. They emphasized the need for a supportive agricultural safety net—one that offers direct payments for transition costs, tailored crop insurance options to mitigate the financial risks of adopting perennial systems, and updated farming practice standards to help farmers shift toward perennial systems. They also highlighted the importance of recognizing the ecological services of perennials and prioritizing these practices in conservation programs and increasing technical assistance resources to support perennial agriculture. To secure long-term viability, there is a need to stimulate market demand by developing supply chains, updating procurement policies to favor perennial agricultural products, and promoting their benefits through nutritional guidance [193]. Finally, they stressed that sustained research funding investment is essential, calling for longer-term grants, dedicated programs, and expanded institutional support to accelerate perennial crop development and unleash their environmental and agricultural potential. In addition to policy reforms, economic instruments can further motivate perennial adoption. Payments for ecosystem services can play a pivotal role in encouraging the adoption of perennial cropping systems by recognizing and rewarding the broader suite of benefits these systems provide beyond biomass yield. Findings from Kiefer et al. [194] showed that when ecosystem services such as climate regulation, nutrient cycling, erosion control, and recreational value were monetized, perennial systems such as wild plant mixtures became economically competitive with high-yield annual crops, despite producing less biomass. This illustrates how valuing non-market services can narrow or even close the revenue gap that often discourages farmers from adopting perennial options. Complementing this, Li and Zipp [195] demonstrated that payments for ecosystem services or similar financial incentives can stimulate land-use shifts toward perennial energy crops by compensating farmers for environmental benefits that are otherwise unpriced. They indicated that the effectiveness of payments for ecosystem services depends on factors such as land-specific ecological potential and the long-term persistence of perennial species, highlighting the need for multi-year contracts and carefully designed policy horizons. Viewed together, these approaches demonstrate that thoughtfully designed policy and economic frameworks can overcome market barriers, accelerate the adoption of perenniality, and ultimately reinforce the ecological and economic resilience of agricultural systems.

6. Conclusions

The intensification of agriculture to meet global food, fuel and fiber demands has led to widespread soil degradation, characterized by erosion, structural decline, loss of biodiversity, and nutrient pollution. This review synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that the integration of perennial vegetation into agricultural systems presents a viable strategy to address these challenges. The literature reported that perennial-inclusive systems enhance soil organic carbon sequestration, improve water retention and infiltration, reduce bulk density, and mitigate sediment and nutrient loss. These improvements in soil physical and hydraulic properties contribute to the long-term sustainability and resilience of cropping systems while also enhancing key ecosystem services such as water quality improvement, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration. However, despite these benefits, the widespread adoption of perennial-based systems remains limited by crop management, economic viability, and policy-related hurdles. A major gap in literature is the lack of large-scale data on the economic viability of perennial-based systems. In addition, limited understanding exists regarding the impacts of perenniality on crop yield across varying production systems. This synthesis underscores the need for future research to focus on optimizing perennial cropping strategies, with particular attention to their performance across diverse soil types and climatic conditions, as well as their effects on crop yield and farm profitability. Furthermore, policy support is essential to enable broader adoption. Financial strategies such as subsidies for perennial establishment and carbon credit programs could help bridge the economic and adoption gaps. Enhanced federal and state-level investment in research and outreach is also critical to advance the knowledge of the climate and soil conservation benefits of perenniality. Ultimately, perenniality offers a promising pathway to reverse soil degradation, enhance ecological resilience, and achieve a more sustainable model of agricultural productivity for future generations.

7. Future Perspectives

Advancing the perenniality in agricultural systems will require coordinated, long-term research efforts that capture the full complexity of soil–plant–climate interactions. Establishing long-term field experiment networks across diverse soil types, climatic regions, and management contexts is essential for generating robust, comparable datasets that reveal temporal changes in soil physical properties, ecosystem service delivery, and crop performance. Integrating remote sensing technologies including satellite-based vegetation monitoring, hyperspectral imaging, and thermal sensing into these networks would provide scalable, continuous assessment of perennial vegetation dynamics, water use, and landscape-level soil conservation outcomes. Future research should also expand the use of process-based models to simulate how perennial systems affect hydrological processes, carbon and nutrient cycling, and crop performance under varying climate scenarios. Such studies are critical for identifying optimal perennial crop species, management strategies, and landscape placements that maximize both ecological benefits and farm profitability. Additionally, deeper investigation into soil–plant–atmosphere interactions is needed to clarify how perennial root systems, microbial communities, and soil structure respond to climate extremes such as prolonged drought, heat stress, and shifts in seasonal precipitation patterns. Given the growing focus on climate mitigation, there is also a pressing need for more comprehensive life-cycle assessment studies to quantify the net climate benefits of perennial cropping systems. Expanded life cycle analysis efforts would provide stronger evidence regarding greenhouse gas reductions, energy efficiency gains, and long-term carbon sequestration potential. Collectively, these research priorities will help build the understanding and predictive capacity necessary to guide management decisions, refine economic assessments, and inform policy frameworks that support the widespread adoption of perennial agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172410988/s1, Table S1: Perenniality impacts on water stable aggregates and mean weight diameter across different studies; Table S2: Perenniality impacts on soil bulk density across different studies; Table S3: Perenniality impacts on soil pore size distribution across different studies; Table S4: Perenniality impacts on water infiltration rate and saturated hydraulic conductivity across different studies; Table S5: Perenniality impacts on volumetric water content at saturation (θSAT), volumetric water content at field capacity (θFC), volumetric water content at permanent wilting point (θPWP), and plant available water (PAW) across different studies; Table S6: Perenniality impacts on soil organic carbon and total nitrogen across different studies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- FAO. ITPS Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR)—Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kraamwinkel, C.T.; Beaulieu, A.; Dias, T.; Howison, R.A. Planetary Limits to Soil Degradation. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R. Soil Erosion and Agricultural Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13268–13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Burgess, M. Soil Erosion Threatens Food Production. Agriculture 2013, 3, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D. Soil Erosion: A Food and Environmental Threat. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2006, 8, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.P.; Feng, Y.; Githinji, L.; Ankumah, R.; Balkcom, K.S. Impact of No-Tillage and Conventional Tillage Systems on Soil Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2012, 2012, 548620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Flury, M.; Neely, H.; Bary, A.; Akin, I.; LaHue, G.T. Compaction of a Sandy Loam Soil Not Impacted by Long-Term Biosolids Applications. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 253, 106648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalvi, H.N.; Rafiya, L.; Rashid, S.; Nisar, B.; Kamili, A.N. Chemical Fertilizers and Their Impact on Soil Health. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers, Vol 2; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-3-030-61009-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lark, T.J.; Salmon, J.M.; Gibbs, H.K. Cropland Expansion Outpaces Agricultural and Biofuel Policies in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lark, T.J.; Clark, C.M.; Yuan, Y.; LeDuc, S.D. Grassland-to-Cropland Conversion Increased Soil, Nutrient, and Carbon Losses in the US Midwest between 2008 and 2016. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 054018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhou, S.; Margenot, A.J. From Prairie to Crop: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Surface Soil Organic Carbon Stocks over 167 Years in Illinois, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strock, J.S.; Johnson, J.M.F.; Tollefson, D.; Ranaivoson, A. Rapid Change in Soil Properties after Converting Grasslands to Crop Production. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, P.K.; Algoazany, A.S.; Mitchell, J.K.; Cooke, R.A.C.; Hirschi, M.C. Subsurface Water Quality from a Flat Tile-Drained Watershed in Illinois, USA. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 115, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.Z.; Hamilton, S.K.; Robertson, G.P.; Basso, B. Phosphorus Availability and Leaching Losses in Annual and Perennial Cropping Systems in an Upper US Midwest Landscape. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]