Abstract

This study focuses on improving the fatigue strength and overall performance of sustainable biopolymer polylactic acid (PLA) components manufactured via Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) additive manufacturing process. PLA, as a biodegradable and renewable polymer derived from natural resources, represents a promising alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics in engineering and research applications. The influence of key FDM process parameters—layer height, infill density, and number of perimeters—on critical performance indicators such as filament consumption, printing time, and fatigue strength (number of cycles to failure) was systematically analyzed using the Taguchi L9 orthogonal array. Subsequently, Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) was applied as a multi-objective optimization technique to identify the parameter settings that achieve an optimal balance between mechanical durability and resource efficiency. The obtained results demonstrate that a proper combination of process parameters can significantly enhance the mechanical reliability and sustainability profile of FDM-printed PLA parts, contributing to the broader adoption of eco-friendly materials in additive manufacturing.

1. Introduction

Fused deposition modelling (FDM) is one of the most widely used additive manufacturing processes. In 1992, the US company Stratasys launched the first series of devices on the market [1], based on a process developed by S. Scott Crump in the late 1980s [2]. The basic principle of the fused deposition process consists of extruding and depositing the building material layer by layer, resulting in three-dimensional objects. The devices used vary in size and range from table-sized devices to massive industrial equipment [3]. The building material, often called filament or wire, is wound onto a spool. The printer guides the filament into a thermally controlled nozzle for melting and deposition. The material leaves the nozzle in a viscoelastic state and is deposited on the working surface according to the data obtained from the CAD model. Because the material solidifies very quickly, it is commonly printed inside heated chambers or on heated substrates to ensure stable deposition. Once the layer has solidified, the work surface is lowered by the layer thickness, and a new layer is applied in the same way, which then bonds with the previous one. When printing products with complex geometry, it is necessary to provide support structures. Some FDM systems employ a dual-nozzle setup in which one nozzle prints the main part while the other deposits dedicated support material (often wax or another easily removable substance). However, most 3D printers operate with a single nozzle, using the same material for both the part and its support structures. Due to the weak bond between the part and the support structures, the latter can be easily removed with a water jet [4].

In the FDM process, several parameters significantly influence the quality and performance of the printed parts [5,6]. One of these parameters is the air gap, which refers to the distance between neighbouring filament threads and influences the quality of the bonding. The extrusion temperature, which is determined by the material and the desired printing speed, controls the thermal state of the filament during deposition. Another important factor is the build orientation, which describes the spatial arrangement of the part in relation to the x, y and z axes of the build plate. The inner structure, known as the infill, can be printed with different infill patterns, with hexagonal, circular and linear configurations being the most common. The outermost layers or perimeter are usually printed solid and more elastic to ensure the stability of the part. The raster width, which depends on the nozzle diameter, defines the width of the deposited filaments, while the raster angle determines the direction of filament deposition, which is usually aligned along the x-axis. The proportion of solid material inside the printed geometry—commonly referred to as infill density—largely defines how heavy the final component will be. Similarly, the thickness of each deposited layer, which is limited by the nozzle setup, indicates the incremental build step in the vertical z direction. The printing speed, defined in mm/s, governs how fast the nozzle travels across the xy-plane and directly affects the total time required to complete a print. To improve adhesion between the layers, the build plate can be heated to an optimum temperature depending on the material. Finally, the printing resolution, which is usually between 0.05 and 0.5 mm, depends largely on the chosen material and process settings; higher resolutions (i.e., smaller values) result in greater surface detail and smoother surfaces.

Compared to other 3D printing processes, FDM is considered user-friendly and cost-efficient [7]. With FDM, complex shapes and structures can be produced with high precision and without unnecessary material waste [8]. The production process is fast and therefore enables faster product development cycles with minimized costs for defective products [9]. The materials used in this process are diverse, mostly thermoplastic polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG), polycarbonate (PC), and nylon [10]. Parts produced with FDM do not necessarily have to be post-processed, e.g., by heat treatment, chemical surface modification or mechanical processing [8].

Parts produced with FDM usually have lower strength and fatigue life due to voids, poor interlayer bonding and material degradation caused by improperly set process parameters [11]. The quality of the printed part is highly dependent on the printing parameters, which makes optimizing the process parameters necessary and complex [12,13].

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a thermoplastic aliphatic polyester that is synthesized from renewable biomass sources such as corn starch or sugar cane, making it a sustainable alternative to petroleum-based polymers. In the context of additive manufacturing, PLA has become the dominant material for fused deposition modelling (FDM) due to its favourable processing properties, including low glass transition (45–65 °C) and melting temperatures (140–180 °C), minimal deformation upon cooling and excellent printability without a heated chamber [14,15,16]. Although PLA offers advantages in terms of dimensional stability and environmental compatibility, it has significant limitations in mechanical performance, especially fatigue strength, due to its semi-crystalline molecular structure, limited ductility and poor interlayer bonding under tensile and cyclic loading [10,17,18].

Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) is a quantitative method suitable for the analysis of complex systems with limited or uncertain data. It is particularly effective for multi-objective optimization and decision making and is therefore well suited for improving the fatigue strength of FDM-printed PLA parts. By systematically evaluating the influence of interdependent process parameters, GRA enables reliable optimization even when experimental information is incomplete or inaccurate [7].

Alparslan et al. [8] investigated the effects of different layer heights and infill patterns on the mechanical properties of PLA parts. They found that the optimal mechanical properties of PLA parts were achieved at a layer thickness of 0.15 mm and a hexagonal infill pattern, while the worst performance was observed at 0.35 mm layer thickness in combination with a triangular pattern. When the layer height was increased, the specimens exhibited lower tensile and yield strengths together with reduced elongation. The broken surfaces displayed smooth morphology with evident layer separation, indicating that failure was mainly governed by weak bonding between adjacent layers [8].

The work of Ahmed and Susmel [19] focused on assessing the effect of raster orientation on the mechanical performance and mode of fracture of PLA components produced by FDM under static loading conditions. The research revealed two mechanisms of static failure, namely the initial shear stress-controlled debonding between neighbouring filaments and the subsequent normal stress-controlled fracture of the filaments themselves. The results indicate that the influence of raster angle on the overall strength and fracture resistance can be neglected with little loss of accuracy. Müller et al. [11] demonstrated that infill density is a critical parameter for maintaining mechanical performance after cyclic loading. The study assessed how altering the nozzle opening (0.4 mm vs. 0.6 mm) and adjusting the infill ratio (100%, 80%, 60%) affect the low-cycle fatigue characteristics of PLA materials enhanced with bamboo filler. The results showed that after 1000 load cycles there was an increase in tensile strength of between 0.2% and 9.4% compared to the static test values, indicating cyclic strengthening of the material. The highest increase in strength was observed in samples with 100% infill density and a 0.4 mm nozzle. With decreasing infill density, the tensile strength decreased significantly after fatigue—by up to 29.6% at 60% infill. A similar trend was observed with the larger 0.6 mm nozzle. Hsueh et al. [20] investigated the effects of different FDM printing parameters on the fatigue behaviour of PLA. The study indicates that a 0° raster angle, a honeycomb infill pattern with an infill density of 75%, a higher layer height and lower printing temperatures (180 °C) result in the highest fatigue resistance in rotating bending. Horasan and Sarac [21] investigated the influence of raster angle and printing speed on the fatigue behaviour of 3D-printed PLA samples, which were tested in rotational bending fatigue tests under different forces. As the printing speed increased, the fatigue life of all specimens decreased. The highest fatigue life was achieved at a 30° raster angle. A comprehensive parameter study by Minh et al. [22] assessed how adjustments in multiple FDM settings—ranging from layer-height control and first-layer design to infill structure, nozzle temperature, and shell construction—impact the flexural and cyclic-load performance of PLA. It was found that higher values of fatigue strength and a higher number of cycles were obtained with a higher first layer thickness, rectilinear infill pattern, a higher number of solid layers on top and a higher perimeter value. The fatigue strength has an inverse U-shaped relationship with perimeter value. Dadashi et al. [23] performed high-cycle rotational bending tests on PLA samples that were 3D printed at different printing speeds, printing temperatures and nozzle diameters. Increasing the nozzle diameter generally reduced fatigue resistance. Lower printing temperatures led to a higher fatigue life. The influence of printing speed on fatigue life varied depending on other parameters. Reza Vanaei et al. analyzed the effects of extruder temperature, loading amplitude, and frequency on the fatigue behaviour of FDM-printed PLA and found that at low amplitudes, extruder temperature significantly affects fatigue life and at high loading amplitudes, increasing the frequency leads to a significant decrease in fatigue life [24]. Azadi et al. [25] investigated the effect of printing direction (horizontal and vertical) on the high cycle bending fatigue properties of PLA and ABS polymers produced using the FDM process. The fatigue strength of 3D printed samples in the horizontal direction was consistently higher than that of samples printed in the vertical direction for both PLA and ABS materials. The effect of printing direction was more pronounced at lower stress levels. The fatigue strength exponent (slope of the S-N curve) was more negative for vertically 3D printed samples, indicating a shorter fatigue life at lower stress levels. Gomez-Gras et al. [26] investigated the effects of infill patterns, layer height, nozzle diameter, infill density and printing speed on the fatigue properties of PLA parts produced using the FDM process. Honeycomb infill patterns consistently enabled a longer service life compared to rectilinear infill patterns. Infill density was found to be the most influential parameter on fatigue life, and with an increase in the infill density, there was an exponential increase in fatigue life. Nozzle diameter and layer height were the next two influential parameters, although their relative importance varied depending on the infill pattern. Printing speed showed no significant effect on the fatigue life of PLA samples. Kargar and Ghasemi-Ghalebahman reported higher fatigue life at 75% infill density than samples with 50% infill density at all raster angles in high-cycle fatigue testing under bending load [27].

In this paper, in order to optimize fatigue strength of PLA parts manufactured by FDM 3D printing process, comprehensive investigation combined by experimentations as well as mathematical modelling and optimization procedures was performed. In this work, based on fatigue strength (number of cycles to failure), two additional process responses were analyzed: filament usage and printing time. A multi-objective optimization was performed using the grey relational analysis approach to determine the process parameter values that best satisfy all three conflicting objectives. The findings presented in this paper provide valuable insights into the operating conditions under which PLA components produced by the FDM process achieve the highest fatigue durability, while simultaneously ensuring minimal consumption of material and time resources.

2. Materials and Methods

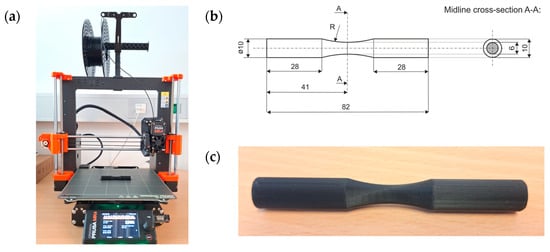

Experimental specimens were fabricated using a Prusa MK4 FDM/FFF 3D printer (Figure 1a), following the dimensional specifications illustrated in Figure 1b. The filament material used was PLA Strongman Black (Azurefilm, Sežana, Slovenia) with a diameter of 1.75 mm. The printing process parameters were defined and managed through the PrusaSlicer software (version 2.9.4.), according to the Taguchi L9 orthogonal array design. Within this experimental framework, three key parameters—layer height, infill density, and number of perimeters—were varied at three distinct levels. The selected process parameters and their respective levels are summarized in Table 1. Process parameters that were kept constant are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup: (a) FDM/FFF 3D printer Prusa MK4, (b) sample dimensions, and (c) printed sample.

Table 1.

Overview of process parameters and level settings.

Table 2.

Constant process parameters.

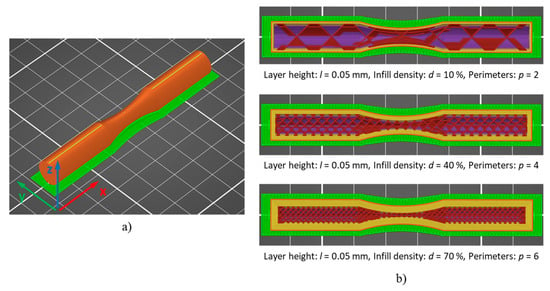

An example of a printed specimen corresponding to one particular combination of process parameter levels, as defined by the Taguchi L9 experimental plan, is shown in Figure 1c. The printing orientation of the samples on the build plate is depicted in Figure 2a, while Figure 2b qualitatively illustrates how the selected printing parameters, especially infill density and perimeter count, shape the longitudinal cross-sectional morphology of the produced components.

Figure 2.

Visualization of manufactured samples: (a) sample orientation at build plate; (b) sample cross-sections at various process parameters levels (infill density, perimeters).

To investigate the fatigue behaviour of the tested 3D printed samples, number of cycles to failure were measured. The analysis considered fatigue failure, incorporating contributions from both crack initiation and crack propagation mechanisms.

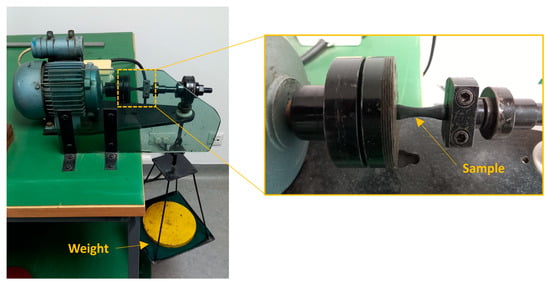

A fatigue strength testing machine was introduced to test samples of a specific geometry for fatigue strength (Figure 1c). The unnotched samples were specially designed for the corresponding analogue laboratory testing machine (Figure 3) and mounted into rotating chucks. Tests were conducted using repeated rotational (tension–compression) and flexural (bending) loading. The bending force was set at 20 N, and the electric motor speed was 2700 rpm. The bending force remained constant and was applied to one side of the fatigue testing machine with a 20 N weight disc (Figure 3). The test samples were replaced manually. All tests were performed under identical laboratory conditions at room temperature.

Figure 3.

Fatigue strength testing machine.

Due to the applied load, fatigue failure occurred in the samples over time, with crack formation and propagation leading to failure, accompanied by a significant change occurring in cross-sectional area.

The number of cycles to failure (N) is measured for each sample as a product of time to failure (t) and electric motor speed (ne):

N = ne·t

The experimental results in Table 3 are the mean values from three repetitions of each trial. The appearance of fractured samples from the trials set is shown in Figure 4. As expected from a fractographic perspective, fracture appearance varied between samples due to different, previously defined 3D printing parameters. Fractures in all samples indicate a certain resistance of the material and a ductile fracture appearance. However, in sample 1, a material delamination fracture is observed due to a specific combination of 3D printing parameters. This highlights the complexity of the 3D printing process and the need for parameter optimization, which is discussed further in this work.

Table 3.

Experimental results.

Figure 4.

Fractured specimens.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results Modelling

After obtaining the experimental measurements, regression analysis was employed to establish mathematical relationships between the process input parameters and output responses, thereby enabling the prediction of outcomes for specific parameter values. The developed regression models, based on the obtained experimental data, quantitatively describe the influence of individual process variables on the corresponding responses [28]. Moreover, the regression models provide a solid basis for visualizing the effects of process parameters on the analyzed responses through the response surface methodology (RSM) [29,30]. The obtained regression models for all three process responses are presented in Equations (1)–(3).

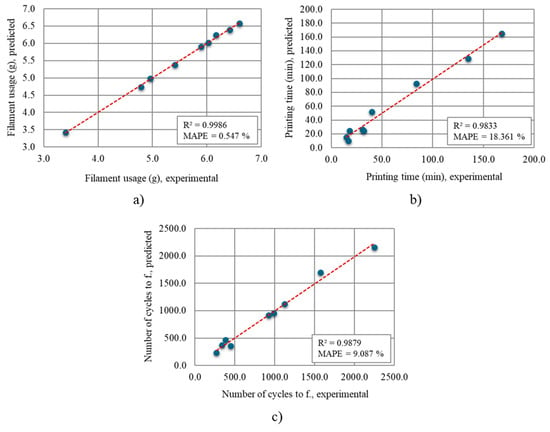

Once the regression-based mathematical modelling of the 3D printing process responses was completed, the developed models needed to be validated. In this step, a comparison was conducted between the responses predicted by the mathematical models and those obtained experimentally. Model accuracy was quantified using standard validation indicators, namely the coefficient of determination (R2) and the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). An overview of how the predicted responses align with the experimental results, along with all computed validation measures for the considered FDM printing conditions, is provided in Figure 5. The obtained values of R2 and MAPE confirm the high prediction accuracy of the developed models. Therefore, the defined regression equations can be further utilized to analyze the effects of process parameters on the output responses through the application of response surface methodology (RSM).

Figure 5.

Experimental values versus regression-based predictions for (a) filament usage, (b) printing time, and (c) number of cycles to failure responses.

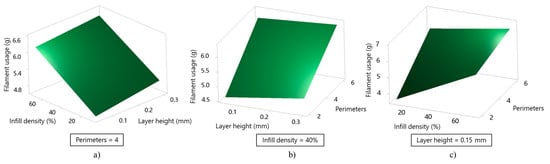

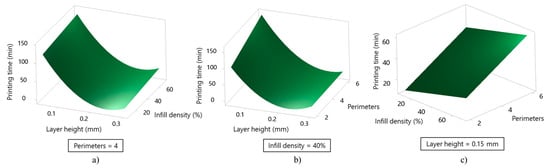

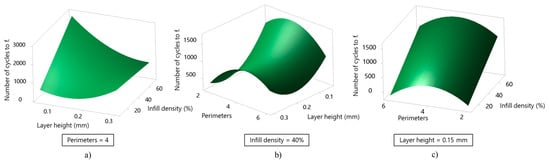

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 present 3D surface plots illustrating the effects of variable process parameters on the fused deposition modelling (FDM) process responses, including filament usage, printing time, and the number of cycles to failure. Each surface plot depicts the interaction effects between two process parameters, while the third parameter was fixed at its intermediate value.

Figure 6 illustrates the influence of process parameters on the filament usage response. The interaction between infill density and layer height (Figure 6a) shows that an increase in infill density strongly increases filament usage due to the larger volume of deposited material. It is also evident that a higher layer height slightly increases filament usage, as a thicker extruded layer results in a greater volume of material deposited per printing path, which outweighs the overall reduction for having fewer printed layers. The interaction between layer height and the number of perimeters (Figure 6b) confirms the slight influence of layer height on material consumption, while a higher number of perimeters significantly increases filament usage by adding additional wall contours. Figure 6c further confirms that infill density and the number of perimeters have a cumulative effect on filament usage: denser infill increases the internal volume, whereas more perimeters add material to the outer shell, resulting in the highest filament consumption at their upper levels.

Figure 6.

3D surface plots of filament usage response affected by parameter interactions: (a) layer height–infill density, (b) layer height–perimeters, and (c) infill density–perimeters.

Figure 7 presents the influence of process parameter interactions on the FDM printing time response. Figure 7a shows that an increase in layer height significantly decreases printing time, as thicker layers reduce the total number of layers required to build the part. In contrast, increasing infill density only slightly increases the overall printing time because higher printing speeds are applied for infill deposition, and the infill region occupies a smaller portion of the total printing volume compared to the overall part geometry. Therefore, the influence of layer height on printing time is considerably greater than that of infill density. Figure 7b shows a similar trend, where increasing layer height reduces printing time, while a higher number of perimeters slightly extends it due to the longer printing path required for additional wall contours. Finally, Figure 7c demonstrates that infill density and number of perimeters cumulatively contribute to longer printing times: higher infill density increases the internal infill volume, whereas more perimeters extend the external wall paths. Consequently, the maximum printing time is observed when both parameters are set to their upper levels.

Figure 7.

3D surface plots of printing time response affected by parameter interactions: (a) layer height–infill density, (b) layer height–perimeters, and (c) infill density–perimeters.

Figure 8 illustrates the influence of process parameter interactions on the number of cycles to failure in the FDM process. Figure 8a shows that higher infill density increases the number of cycles to failure, as denser internal structures provide improved load-bearing capability and reduce the presence of voids that act as stress concentrators. In contrast, increasing layer height decreases fatigue life because thicker layers produce rougher interlayer surfaces and weaker bonding between layers, enabling earlier crack initiation under cyclic loading. Figure 8b demonstrates that parts printed with a larger number of perimeters exhibit higher fatigue resistance. Additional outer walls enhance structural stiffness and delay crack propagation from the specimen surface, while increasing layer height again leads to a gradual reduction in fatigue life due to poorer interlayer adhesion quality. Figure 8c confirms that both infill density and number of perimeters positively affect fatigue performance. A higher infill density improves internal material continuity, whereas more perimeters strengthen the external shell and promote more uniform stress distribution. The best fatigue life is achieved when both parameters are set to their upper levels, resulting in a more homogeneous and dynamically stable structure.

Figure 8.

3D surface plots of number of cycles to failure response affected by parameter interactions: (a) layer height–infill density, (b) layer height–perimeters, and (c) infill density–perimeters.

3.2. Multi-Objective Optimization

In this stage, a multi-objective optimization procedure was carried out to determine the optimal combination of input parameters that yield the most favourable FDM process responses. The objective was to simultaneously minimize filament usage and printing time while maximizing fatigue life, expressed as the number of cycles to failure. To ensure a balanced evaluation of these three criteria, equal weights were assigned in the Grey relational analysis (GRA). This choice was made to avoid bias toward any single objective and to reflect their comparable importance from both an engineering and sustainability perspective: reducing material consumption and printing time improves resource efficiency, while maximizing fatigue life enhances the functional performance and durability of printed components. Accordingly, a combined Taguchi–Grey relational analysis approach was applied. This hybrid method enables the conversion of multiple performance characteristics into a single grey relational grade, allowing the overall optimization of process parameters. The main advantage of this approach lies in its simplicity, as it avoids the use of complex mathematical algorithms and provides a clear identification of optimal parameter levels without requiring intermediate estimations [31].

First step in multi-objective optimization procedure is to calculate S/N ratios from observed responses data. S/N ratios need to be calculated depending on specific response objective function. In this case the objective of filament usage and printing time responses is their minimum and their S/N ratios were calculated following Equation (4). Conversely, the number of cycles to failure response needs to be maximized and accordingly its S/N ratios were derived following Equation (5).

where n = number of replications, yij = observed response value where i = 1, 2,…, n; j = 1, 2,…, k.

The Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) approach is used to examine data obtained from multiple experimental outputs and to determine how closely each output aligns with its corresponding ideal target. This similarity is expressed through the Grey Relational Coefficient (GRC), which quantifies the closeness between the measured and ideal values. A GRC value of 1 signifies that the experimental result perfectly matches the ideal response. To enable multi-objective optimization, the individual GRCs corresponding to different responses are aggregated into a single value known as the Grey Relational Grade (GRG). The objective of optimization within the GRA framework is to maximize the GRG, regardless of whether individual response goals involve maximization or minimization. The highest GRG value corresponds to the combination of input process parameter levels that simultaneously lead to the optimal process outputs [32].

To conduct the multi-objective optimization using GRA, the procedure follows a series of defined steps. The initial step consists of normalizing all experimental responses to the interval [0, 1] in order to reduce variability and make the datasets mutually comparable. In this study, normalization was applied to the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios of each response. Depending on the objective of a specific response, the appropriate normalization equation was selected. For responses where the goal was minimization (i.e., filament usage and printing time), normalization was performed according to Equation (6). Conversely, for the response where the goal was maximization (number of cycles to failure), normalization was carried out following Equation (7). The calculated normalized values for all three responses are summarized in Table 4.

where is the original sequence, is the sequence after data pre-processing (normalization), is the largest value in , and is the smallest value in .

Table 4.

Responses to S/N ratios and normalization results.

The second step in GRA multi-objective optimization procedure is calculation of grey relational coefficient for each response. The GRCs were calculated following Equation (8).

are calculated using Equations (9)–(11).

where is the distinguishing coefficient in the range of (in general, ), is the deviation sequence for the reference sequence, is the reference sequence ( is number of responses), and is the specific comparison sequence.

In the final step, the Grey Relational Grade (GRG) was calculated according to Equation (12). This equation is applicable when equal weights are assigned to all analyzed responses. The calculated Grey Relational Coefficients (GRCs), the corresponding GRG values, and the resulting rankings, where the first rank represents the experimental trial with the highest GRG value and the last corresponds to the lowest, are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of GRC calculations, overall GRG evaluation, and ranked performance outcomes.

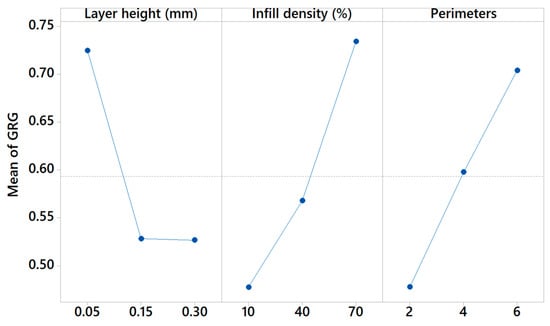

To gain a deeper understanding of the effects of input process parameters on the calculated Grey Relational Grade (GRG) values and to assess the significance of each parameter, a main effects plot for GRG was generated, as shown in Figure 9. Based on the slope of the plotted blue lines, it is evident that all three parameters exert a noticeable influence on the GRG output. The main effects plot can also be utilized to identify the optimal process parameter levels that correspond to the highest GRG values, i.e., the most favourable overall process responses. Accordingly, the blue points representing the highest mean GRG values indicate the optimal parameter levels. In this study, the maximum GRG value was obtained for the following process settings: layer height = 0.05 mm, infill density = 70%, and number of perimeters = 6. The results summarized in Table 6 further confirm these findings. Bolded values in the table denote the process parameter levels that yield the optimal mean GRG values. The final column in Table 6 shows the relative importance of each factor, determined from the difference between their maximum and minimum average GRG values. Based on this evaluation, infill density emerges as the dominant parameter, followed by the number of perimeters, whereas layer height, although still relevant, has the smallest influence on the overall optimization result.

Figure 9.

Main effects plot for grey relational grade (GRG).

Table 6.

GRG evaluation response table.

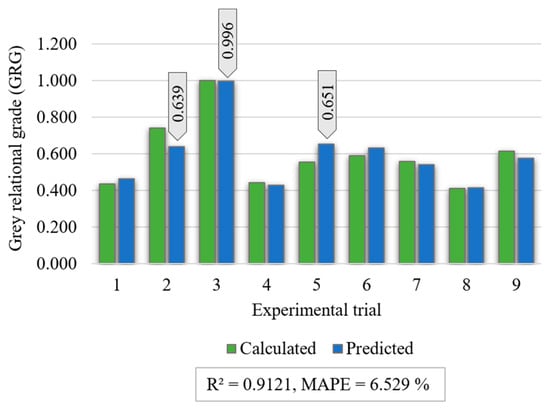

To gain deeper insight into how interactions among the printing parameters influence the Grey Relational Grade (GRG) and to identify the optimal operational window of the FDM process, a regression model was constructed based on the computed GRG values. The corresponding predictive expression is given in Equation (13). The prediction accuracy of the developed GRG regression model was verified by comparing the calculated GRG values (Table 5) with those predicted by the mathematical model. The comparison results and the corresponding validation metrics, R2 = 0.912 and MAPE = 6.529%, are presented in Figure 10, confirming the high predictive capability of the developed regression equation and justifying its use for further analysis of parameter interaction effects. Figure 10 also marks the three trials that achieved the greatest predicted GRG values. These cases represent parameter settings that satisfy a Pareto-efficient trade-off among the objectives of reducing filament usage (F), shortening printing time (T), and increasing the number of cycles to failure (C). The highest predicted GRG value was obtained for the third experimental trial, corresponding to the following parameter settings: layer height = 0.05 mm, infill density = 70%, and number of perimeters = 6. These results are consistent with the findings presented in Table 5 and Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Comparison between calculated and regression predicted GRG values.

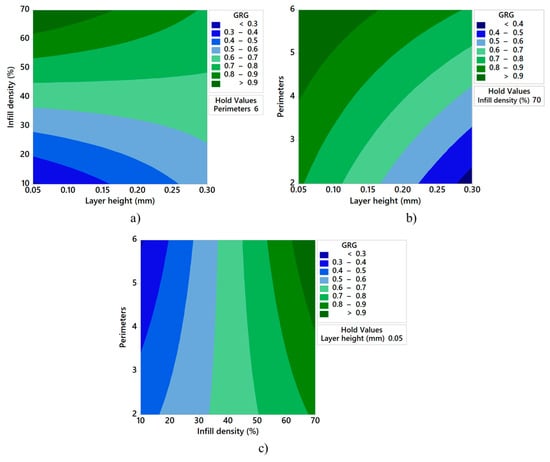

Contour diagrams, shown in Figure 11, were produced to visualize the Pareto-optimal region and to pinpoint the most effective areas of the 3D printing parameter space. In these diagrams, two factors change concurrently, whereas the third parameter is kept constant at a selected value. The darkest green areas highlight the optimal process window, indicating conditions that provide the highest fatigue performance with minimal material usage and printing duration.

Figure 11.

GRG response influenced by parameter interactions: (a) layer height–infill density, (b) layer height–perimeter count, and (c) infill density–perimeter count.

Finally, an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the relative contribution of each process parameter to the modelled GRG output. Although none of the factors reached statistical significance at the 95% confidence level, the ANOVA trends shown in Table 7 indicate that infill density has the largest relative influence on the GRG, while layer height and the number of perimeters show comparatively lower, but still observable, effects within the experimental design.

Table 7.

ANOVA-based assessment of the GRG response.

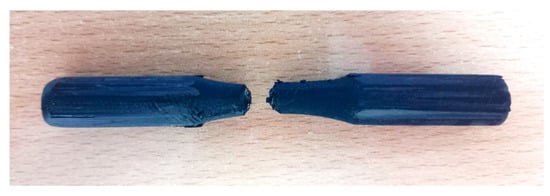

To evaluate the improvement achieved after identifying the optimal FDM process parameter settings, the GRG values obtained for the initial and optimal conditions were compared. The results indicated an increase of approximately 65% in the GRG value, demonstrating a clear enhancement in overall process performance. To further validate these findings, a confirmation experiment was conducted using the optimal parameter combination. In this experiment, a new specimen (Figure 12) was printed and tested under the optimized settings to verify whether the predicted improvement would be reproduced experimentally. As illustrated in Figure 12 and outlined in Table 8, the results of this confirmation experiment verified the outcomes of the multi-objective optimization procedure and confirmed the effectiveness of the defined optimal FDM 3D printing process parameters.

Figure 12.

Confirmation experiment for optimal conditions.

Table 8.

Outcomes of the validation experiment.

4. Conclusions

The main aim of this study was to investigate the influence of FDM 3D printing process parameters, layer height, infill density, and number of perimeters on key process responses: filament usage, printing time, and fatigue life (i.e., number of cycles to failure). The experimental work was performed using biodegradable PLA material according to the Taguchi L9 orthogonal array design. From the conducted evaluations, the key findings can be summarized as follows:

- Regression-based mathematical modelling proved to be an effective approach for describing the relationships between input FDM process parameters and the analyzed responses. This was confirmed by the good agreement between experimental and predicted values, with high R2 and low MAPE values. Furthermore, the developed models enabled the creation of response surface plots, which provided additional insight into the effects of FDM process parameter interactions on the defined responses.

- Filament usage was primarily influenced by infill density, while layer height had only a minor effect. A simultaneous increase in infill density and number of perimeters led to the highest material consumption due to a larger internal volume and additional outer contours.

- Layer height had the most significant influence on printing time, as greater layer heights considerably reduced the total build time. In contrast, infill density and number of perimeters had a smaller but cumulative effect, with higher values of both parameters leading to longer printing durations.

- Higher infill density and a greater number of perimeters significantly improved fatigue life, owing to enhanced structural integrity and more uniform stress distribution. Conversely, increasing layer height reduced fatigue performance due to weaker interlayer bonding and increased surface roughness.

- The Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) supported by the Taguchi method proved to be an effective and practical approach for conducting multi-objective optimization. It successfully defined FDM process parameter levels that simultaneously minimize material and time consumption while maximizing the durability of printed parts.

- The optimal process parameter settings obtained from GRA multi-objective optimization are layer height = 0.05 mm, infill density = 70%, and number of perimeters = 6.

- The main effects plot for the Grey Relational Grade (GRG), contour plots, and ANOVA results revealed that infill density had the most significant influence on the GRG, while layer height and number of perimeters showed slightly lower but still meaningful contributions to the overall optimization outcome.

- The multi-objective optimization resulted in a 65% improvement in the overall GRG value, confirming a substantial enhancement in process performance. The confirmation experiment validated the reliability of the optimization procedure and the effectiveness of the defined optimal FDM process parameters.

- Moreover, the results of this study identify specific parameter configurations that achieve a favourable balance between fatigue performance, filament usage, and printing time. This constitutes the primary novelty and scientific contribution of the work, demonstrating that mechanically reliable PLA components can be produced with reduced material and energy input, thereby supporting more sustainable and environmentally responsible FDM manufacturing practices.

- Future work will focus on including additional process parameters, considering other mechanical and functional properties as output responses, and extending the study to advanced and composite 3D printing materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and N.Č.; methodology, I.P., N.Č., K.A. and P.Lj.; software, I.P.; validation, I.P., K.A. and P.Lj.; formal analysis, I.P., P.Lj. and N.Č.; investigation, I.P., N.Č. and P.Lj.; resources, I.P. and K.A.; data curation, I.P. and N.Č.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P., K.A. and P.Lj.; writing—review and editing, I.P., N.Č. and P.Lj.; visualization, I.P. and P.Lj.; supervision, I.P. and N.Č. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABS | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CAD | Computer-aided design |

| GRA | Grey Relational Analysis |

| GRC | Grey Relational Coefficient |

| GRG | Grey Relational Grade |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modelling |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| PC | Polycarbonate |

| PETG | Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

References

- Godec, D.; Šercer, M. Aditivna Proizvodnja; FSB: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015; 376p. [Google Scholar]

- Topčić, A. Aditivna Proizvodnja—Pregled Stanja, Izazovi i Mogućnosti Primjene. In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on the Significance of the Development of Technique, Technology, Innovation, Innovation and Information Technologies INN&TECH 2022, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 16 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.M.; Rahman, T.T.; Pei, Z.; Ufodike, C.O.; Lee, J.; Elwany, A. Additive manufacturing using agriculturally derived biowastes: A systematic literature review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.S.; John, S.; Roy Choudhury, N.; Dutta, N.K. Additive manufacturing of polymer materials: Progress, promise and challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, V.; Rajurkar, S.; Awari, G.; Yelamasetti, B.; Shelare, S. Influence of FDM process parameters on tensile strength of parts printed by PLA material. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 19, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Lai, M.K.; Ismail, K.I.; Yap, T.C. The effect of printing temperature on bonding quality and tensile properties of fused deposition modelling 3D-printed parts. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1257, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almehairi, E.H. A Taguchi-Grey Relational Analysis of FDM Printed PLA. Master’s Thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY, USA, 28 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alparslan, C.; Bayraktar, Ş.; Gupta, K. A comparative study on mechanical performance of PLA, ABS, and CF materials fabricated by fused deposition modelling. Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, R.; Kandasamy, M.; Raja, V.; Balasubramani, S.; Vijayakumar, M.K.; Mahadevan, R. Experimental investigation on process parameter optimization to enhance tensile strength in FDM—3D printing process with PLA material. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advancement in Manufacturing Engineering (ICAME 2022), Islamabad, Pakistan, 25 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; Eagle, I.N.R.; Yodo, N. A review on filament materials for fused filament fabrication. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Jirků, P.; Šleger, V.; Mishra, R.K.; Hromasová, M.; Novotný, J. Effect of infill density in FDM 3D printing on low-cycle stress of bamboo-filled PLA-based material. Polymers 2022, 14, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Cai, J. Effects of fused deposition modeling process parameters on tensile, dynamic mechanical properties of 3D printed polylactic acid materials. Polym. Test. 2020, 86, 106483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, I.; Popović, M.; Dučić, N.; Stepanić, P.; Marinković, D.; Ćojbašić, Ž. Improving the mechanical characteristics of the 3D printing objects using hybrid machine learning approach. Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jem, K.J.; Tan, B. The development and challenges of poly (lactic acid) and poly (glycolic acid). Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2020, 3, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, A.; Ashour, F.H.; Hakim, A.A.A.; Bassyouni, M. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijarimi, M.; Ahmad, S.; Rasid, R. Mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of PLA/PP melt blends. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agriculture, Chemical and Environmental Sciences (ICACES 2012), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 6–7 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fico, D.; Rizzo, D.; Casciaro, R.; Corcione, C.E. A review of polymer-based materials for fused filament fabrication (FFF): Focus on sustainability and recycled materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaidi, A.A.M.A.; Al-Gawhari, F.J.J. Types of polymers using in 3D printing and their applications: A brief review. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2023, 1, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Susmel, L. Additively manufactured PLA under static loading: Strength/cracking behaviour vs. deposition angle. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2017, 3, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, M.-H.; Lai, C.-J.; Chung, C.-F.; Wang, S.-H.; Huang, W.-C.; Pan, C.-Y.; Zeng, Y.-S.; Hsieh, C.-H. Effect of printing parameters on the tensile properties of 3D-printed polylactic acid (PLA) based on fused deposition modeling. Polymers 2021, 13, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horasan, M.; Sarac, I. The fatigue responses of 3D-printed polylactic acid (PLA) parts with varying raster angles and printing speeds. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 47, 3693–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son Minh, P.; Nguyen, V.T.; Uyen, T.T.; Do, T.T.; Duong Thi Van, A.; Nguyen Le Dang, H. The effects of 3D printing designs on PLA polymer flexural and fatigue strength. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2024, 34, 065004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, A.; Azadi, M. Optimization of 3D printing parameters in polylactic acid bio-metamaterial under cyclic bending loading considering fracture features. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaei, H.R.; Shirinbayan, M.; Vanaei, S.; Fitoussi, J.; Khelladi, S.; Tcharkhtchi, A. Multi-scale damage analysis and fatigue behavior of PLA manufactured by fused deposition modeling (FDM). Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 27, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, M.; Dadashi, A.; Dezianian, S.; Kianifar, M.; Torkaman, S.; Chiyani, M. High-cycle bending fatigue properties of additive-manufactured ABS and PLA polymers fabricated by fused deposition modeling 3D-printing. Forces Mech. 2021, 3, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gras, G.; Jerez-Mesa, R.; Travieso-Rodriguez, J.A.; Lluma-Fuentes, J. Fatigue performance of fused filament fabrication PLA specimens. Mater. Des. 2018, 140, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, E.; Ghasemi-Ghalebahman, A. Experimental investigation on fatigue life and tensile strength of carbon fiber-reinforced PLA composites based on fused deposition modeling. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peko, I.; Marić, D.; Nedić, B.; Samardžić, I. Modeling and Optimization of Cut Quality Responses in Plasma Jet Cutting of Aluminium Alloy EN AW-5083. Materials 2021, 14, 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrsalović, L.; Čatipović, N.; Gudić, S.; Kožuh, S. Beneficial effect of Cu content and austempering parameters on the hardness and corrosion properties of austempered ductile iron (ADI). Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2025, 23, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perec, A.; Radomska-Zalas, A.; Fajdek-Bieda, A.; Pude, F. Process optimization by applying the response surface methodology (RSM) to the abrasive suspension water jet cutting of phenolic composites. Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2023, 21, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čatipović, N.; Peko, I.; Grgić, K.; Periša, K. Multi Response Modelling and Optimisation of Copper Content and Heat Treatment Parameters of ADI Alloys by Combined Regression Grey-Fuzzy Approach. Metals 2024, 14, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peko, I.; Crnokić, B.; Čulić-Viskota, J.; Matić, T. Hybrid Grey–Fuzzy Approach for Optimizing Circular Quality Responses in Plasma Jet Manufacturing of Aluminum Alloy. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).