Abstract

Amid escalating climate change and delayed political measures to prevent them, questions of how individuals negotiate the tension between collective climate protection and personal disaster preparedness have become increasingly urgent. This study explores these dynamics by examining the biography of ‘Lukas Sandner’, a sustainability activist whose trajectory reflects a shift from collective climate action to personal adaptation. Using a reconstructive biographical analysis based on a biographical narrative interview and the documentary method, the study reconstructs the interpretive frameworks and orientations that shape his actions and that situate him within this tension. The analysis shows that transformative learning was triggered by a disorienting event—particularly a severe heavy rainfall event—which redirected his focus from collective prevention efforts towards individual preparedness. His strategies include stockpiling, technical measures, and gardening understood as a hybrid practice linking ecological ideals with precautionary foresight. These shifts are dialectical, shaped by earlier experiences of concealment and reframing. The findings illustrate how personal trajectories intersect with broader social dynamics, showing how biographical experiences, structural conditions, and collective discourses converge to shape preparedness, highlighting the interplay between collective responsibility and private resilience. The reconstruction of Sandner’s biography may provide clues to underlying societal trends toward individualised adaptation and risk prevention strategies in industrialised societies in response to growing disillusionment about the possibility of preventing climate change.

1. Introduction

Climate change and the resulting increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters result in significant challenges to societies around the world. Extreme weather events such as floods, storms, droughts and heatwaves are becoming increasingly common and pose an existential threat to human life, ecosystems and socioeconomic stability [1,2]. Consequently, enhancing disaster resilience while promoting sustainable development (SD) has become a critical global political priority [3,4].

However, what consequences do the observable effects of climate change have on individual orientations? While concern for sustainability and ecological preservation has grown steadily, the intensity and form of individual commitment often seem to shift at critical junctures. These moments may represent turning points where awareness transforms into action, or conversely, where engagement gives way to resignation.

This article explores environmental commitment as a dynamic process situated at the crossroads of two fundamental orientations: risk prevention and climate adaptation. Preventive strategies emphasise mitigating environmental damage before it occurs, whereas adaptive strategies focus on coping with the consequences of ecological change. The tension and interplay between these orientations can reveal important insights into how individuals negotiate their roles, responsibilities, and capacities in the face of environmental challenges.

The relationship between disaster risk reduction (DRR) and sustainable development (SD) have been widely debated at political and academic levels [3,5,6]. Both concepts share a commitment to risk-informed and future-oriented approaches that emphasise reducing vulnerability and enhancing resilience [3]. For example, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) explicitly states that DRR is essential for achieving sustainable development. It reduces the need for preventive measures aimed at minimising the impact of disasters and fostering sustainable societies [7].

However, despite these convergences, there are notable divergences between DRR and SD, particularly regarding their underlying orientations and priorities. DRR often necessitates immediate, practical interventions aimed at safeguarding lives and property, such as technical flood barriers or fire prevention measures. These interventions may conflict with the longer-term ecological objectives inherent in sustainable development initiatives [4]. Such conflicts arise when rapid disaster response measures have a negative impact on ecosystems, biodiversity and overall environmental sustainability.

Furthermore, scholarly discussions primarily focus on macro- and meso-level analyses, examining governance strategies, policy frameworks, and institutional responsibilities [4,8]. However, individual-level orientations and behaviours have received considerably less attention in this discourse. Despite the significance of individual decisions and practices for achieving both sustainability and disaster resilience, little research has explored how individuals negotiate the tensions and contradictions inherent in combining sustainable behaviour with disaster preparedness at a personal level [9,10].

Observations suggest a phenomenon whereby individuals are increasingly shifting their focus from prevention-oriented sustainability measures to disaster preparedness strategies. This shift can be interpreted as a transition from collective, future-oriented prevention to more individualised, immediate adaptation. Hence, understanding why this shift occurs, how individuals negotiate these orientations, and the learning processes involved constitutes the central objective of this article.

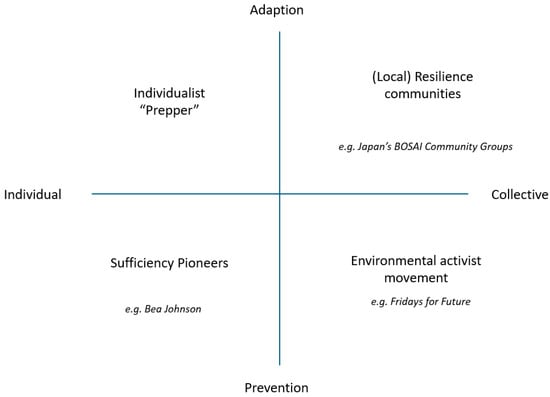

This study advances existing research on DRR, climate adaptation and sustainable development by shifting the analytical focus from policy frameworks and institutional strategies to the micro level of individual orientation. By reconstructing the biographical processes through which an individual negotiates the tension between collective climate protection and personal disaster preparedness, the study shows how macro-level discourses are interpreted, reframed or resisted in everyday practice. The proposed analytical matrix (individual/collective × prevention/adaptation) (see Figure 1) provides a new conceptual framework for identifying and understanding hybrid practices and learning processes that are largely overlooked in current research.

Figure 1.

Analytical matrix of environmental and disaster-preparedness commitments (individual/collective × prevention/adaptation) with illustrative examples.

In this study, we therefore use this shift from collective climate engagement to individual disaster preparedness as the central analytical lens through which the broader dialectic between prevention and adaptation is examined. By analysing how one individual navigates this tension, the study clarifies how macro-level discourses on sustainability and DRR are interpreted, negotiated, and transformed at the micro level.

Addressing this research gap, the article investigates how individual orientations develop and transform within the intersection of sustainability and disaster preparedness. Specifically, it examines how individuals negotiate the tensions between preventive, sustainability-oriented behaviours and adaptive, security-oriented actions. To understand these complex processes, the study employs Transformative Learning Theory [11], which conceptualises significant shifts in worldview triggered by critical life events, deep reflection, and cognitive restructuring. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the analysis relies on an in-depth, single-case design that aims for analytical, rather than statistical, generalisation. Therefore, the purpose of the case is not to claim representativeness, but rather to reveal the mechanisms and orientation structures that may also occur in comparable situations. The strength of the biographical approach lies in its ability to demonstrate how sustainability and DRR discourses are subjectively interpreted and negotiated, providing theoretical insights that can inform future comparative or multi-case research.

Using a biographical narrative approach [12], the study provides in-depth insights into how individuals balance collective sustainability aspirations with personal disaster preparedness demands. By reconstructing an individual’s orientation frameworks [13], the article clarifies how specific experiences of disasters can result in transformative learning processes that shift personal attitudes from collective sustainability action to individual disaster adaptation.

First, to establish the analytical foundation for this individual-level investigation, the theoretical overlaps and tensions between DRR and SD at the political-conceptual and institutional levels (macro- and meso-levels) will be examined. Subsequently, the focus shifts to the micro level, analysing individual negotiation processes to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the relationships and conflicts between sustainability and disaster preparedness.

The findings presented here aim to deepen theoretical understanding and provide valuable insights for policymakers, educators, and practitioners seeking to foster integrated DRR and sustainability approaches at individual and community levels. Finally, our analysis focuses on education, arguing that the negotiated tensions between preventive sustainability and adaptive preparedness offer children and young people concrete opportunities to learn and to contribute to building resilience and fostering sustainable practices within their families, schools, and communities. Everyday practices such as household preparedness planning and kitchen garden cultivation not only promote sustainability but also enhance food security and autonomy in times of crisis. These practices can serve as opportunities for intergenerational learning within families, schools, and local communities, thereby converging Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR).

2. On the Relationship Between Sustainability and Disaster Risk Reduction

2.1. Similarities and Intersections

The comparison of SD and DRR requires clarification of the core ideas and interfaces of both concepts. DRR and SD are complex terms that are interpreted in different ways. The definition of interfaces and boundaries therefore depends heavily on what is understood by the individual terms. A general and very common definition of SD comes from the Brundtland Report (“Our Common Future”). It defines SD as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [14] (para. 3). This report already applies the broad understanding of SD in relation to environmental protection, economic and social development, which was taken up in the “Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development” [15] and presented by Giddings et al. [5] in the well-known integrated three circles diagram.

Although the Brundtland definition has played a foundational role, the concept of sustainable development has evolved substantially over the past few decades. Subsequent global frameworks, including Agenda 21, the Millennium Development Goals and, most notably, the 2030 Agenda with its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), have broadened the concept of sustainable development, making it more operational, multidimensional and governance-oriented [7,15]. This evolution is reflected in academic discourse through expanded interpretations that emphasise ecological limits, social equity, and integrative socio-ecological approaches [5,16,17].

The United Nations also provides a common definition of DRR, linking it to SD: “Disaster risk reduction is aimed at preventing new and reducing existing disaster risk and managing residual risk, all of which contribute to strengthening resilience and therefore to the achievement of sustainable development” [18]. DRR encompasses the practice of reducing disaster risks through systematic efforts to (a) analyse and address the causes of disasters and (b) reduce the vulnerability of people and property through improved preparedness [19] (p. 10–11).

SD and DRR therefore have two points of contact: On the one hand, SD is aimed at minimising risks to people and the planet resulting from unsustainable behaviour. From a DRR perspective, this corresponds to a reduction in the causes of disasters. In this sense, SD is a measure of disaster prevention. On the other hand, the focus is on reducing the consequences of disasters through disaster management measures such as preparedness. Against the backdrop of the increasingly noticeable effects of climate change, these aspects are also gaining importance in discussions on sustainable development. Or as [20] describes it: “everyday-life preparedness focuses more on the notion of ‘disaster reduction’ that appreciates the benefits of nature and to minimise possible damage, than the notion of ‘disaster prevention’ that controls the power of nature” [21] (p. 10).

In a broader sense, economic sustainability also plays a role, e.g., when poverty increases the risk of being affected by disasters, or social sustainability when a lack of social cohesion has a negative impact on the resilience of the population. The Sustainable Development Goals [7] can be used to illustrate the links between SD and DRR. “There are 25 targets related to disaster risk reduction in 10 of the 17 SDGs, firmly establishing the role of disaster risk reduction as a core development strategy” [22] (p. 2). DRR is described here as a necessity for sustainable development, as disasters have a massive impact on equal living conditions, nutrition, education, equality, and other areas. Therefore, DRR is essential for minimising the consequences of disasters. On the other hand, SD contributes to reducing poverty (SDG 1), improving health (SDG 3), providing good education (SDG 4), ensuring clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), and reducing inequality (SDG 10), thereby also contributing significantly to enhancing resilience in the event of disasters. These relationships between SD and DRR are also evident in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [7] and the United Nations Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 [3]. Kitagawa [23] summarises: disaster risk reduction (DRR), climate change adaptation (CCA) and sustainable development (SD) pursue the common goals of reducing risk, strengthening resilience and promoting sustainability.

2.2. Differences and Divergences

In the history of disaster preparedness, nature was seen as a danger that had to be tamed by human intervention [24]. River straightening and drainage were measures aimed at protecting people from flooding and epidemics, rather than protecting nature. This raises the question of whether conflicts also exist between DRR and SD. Such tensions can be observed in areas outside the interfaces, as well as in different prioritisations of the same objectives. DRR and SD can only be harmonised if corresponding compromises are made at the expense of the respective objectives. Conflicting objectives between DRR and SD can be identified, for example, in the following areas:

- (a)

- Technical flood protection measures, such as dyke construction, river straightening, and flood barriers can lead to destruction of floodplain landscapes and wetlands, as well as to the loss of biodiversity.

- (b)

- Fire prevention measures, such as firebreaks or controlled burning, can lead to the loss of habitats and species, soil erosion, and the impairment of air quality.

- (c)

- Infrastructure projects for hazard defence, such as the construction of protective dams, retention basins, emergency roads or other protective structures, can lead to sealing of soils, interference with biotopes, and fragmentation of landscapes and migration corridors for animals.

- (d)

- Coastal and erosion protection measures, such as breakwaters, coastal dams, and concrete walls, can lead to the destruction of dunes, salt marshes, and mangroves, as well as to the alteration of natural sedimentation processes.

Conflicting objectives especially arise when rapid risk minimisation (e.g., for people or property) is perceived as more important than long-term ecological sustainability. However, even with long-term measures, the protection of people and the protection of the environment are weighed against each other.

In addition to these areas, the availability of resources is also a potential area of conflict. This applies to the state level, as well as the institutional and individual areas. Ideally, expenditure can be combined, for example, by focussing expenditure on the aforementioned interfaces between DRR and SD, as also emphasised in the political statements on expenditure for DRR. It is already apparent that between 2010 and 2019 only four percent of disaster relief spending has been invested in preventive measures [25] (p. 8). In particular, it has become obvious that short-term responses to disasters undermine long-term strategies for financing environmental and climate protection [26]. With the increasing frequency of catastrophic events, there is a risk that this trend will become entrenched.

So far, the similarities and differences between DRR and SD have been discussed at the level of governance. This is also reflected in the academic debate on this topic. In contrast, there is hardly any consideration of the relationship between individual orientations toward disaster prevention and sustainable behaviour (e.g., environmental protection). Solidarity and social attitudes unquestionably form a basis for sustainable behaviour. They can also be found in disaster management and relate not only to transnational support in the event of disasters, but also to community-orientated approaches to disaster preparedness, which are common in many countries. In addition, there are thousands of volunteers in many countries who are active in disaster management. Studies also confirm solidarity-based behaviour during disasters [27].

In contrast to a commitment to environmental protection, such as purchasing sustainable products or avoiding waste, self-protection in the context of disaster prevention tends to be self-centred and asocial. Even if exceptions exist, such as forms of social prepping, individual disaster preparedness usually remains focused on the family environment, since the primary concern is the protection of one’s own life and private possessions. These orientations are especially evident among preppers. As a rule, they prefer not to be identified as such, fearing that in an emergency they might be attacked and robbed of their supplies. At the same time, many preppers, especially those in the “Doomer” subculture, assume that crises will lead to chaotic conditions and adopt a survivalist mindset in which everyone is considered a potential enemy. In this perspective, community is imagined only as a survival unit whose sole purpose is mutual protection. Even direct experience of a natural disaster does not necessarily lead to more environmentally friendly behaviour [10].

By comparison, sustainable behaviour does not lead to a direct benefit, but can be understood as a contribution to solidarity. It means acting in a socially responsible way. The likelihood of fulfilling a good life depends on the actions of the entire global community, as our individual actions have no directly tangible effect. At the same time, sustainable action is also associated with restrictions in one’s own life (more costs, e.g., for train journeys, organic food, sustainable clothing). In this sense, sustainable action bears traits of altruism, of selflessness, as the hope for personal benefits is low but at the same time individual disadvantages are accepted for the sake of a better life for society.

Environmental protection, such as the fight against climate change, only makes sense if there is hope of prevention. Or as Franzen put it in a well-known essay: “All-out war on climate change made sense only as long as it was winnable” [28]. The focus is therefore shifting increasingly towards adaptation, both collectively and individually, as efforts to prevent climate change prove, or are likely to prove, unsuccessful.

The question now arises as to how individual orientations develop as a result of the increase in disasters and thus the importance of self-protection, and how interfaces and contradictions between DRR and SD are negotiated. We address this question using a qualitative case study and draw on the theory of transformative learning [11] to conceptualise individual ‘turning points’ as disorienting dilemmas at the level of personal meaning perspectives, in contrast to systemic ‘tipping points’ that mark environmental, social, or epistemic thresholds of change (see Section 3 Theoretical Framework below). Our aim is to trace these negotiation processes at an individual level to gain a deeper understanding of how individuals respond to current developments.

2.3. Analytical Matrix of Environmental and Disaster-Preparedness Commitments

Building on existing work on environmental activism, sufficiency practices, and disaster preparedness, we conceptualise commitments to environmental sustainability and disaster preparedness within a two-dimensional space defined by (a) individual versus collective orientations and (b) prevention versus adaptation (see Figure 1).

The four quadrants indicate prototypical constellations, ranging from individualised “prepping” to sufficiency pioneers, environmental activist movements and (local) resilience communities.

3. Theoretical Framework: Perspectives from Transformative Learning Theory

Transformative Learning Theory, developed by Jack Mezirow [11,29,30], explains how individuals revise their meaning perspectives when confronted with experiences that challenge their established assumptions. A central concept of this approach is the ‘disorienting dilemma’—a critical or disruptive event that prompts individuals to question their previously unquestioned beliefs and engage in critical reflection [11,30,31]. Through this reflective process, new frames of reference may emerge and become integrated into one’s actions and worldview. Subsequent scholars building on Mezirow have highlighted that transformative processes are not purely cognitive, but are also shaped by emotional, embodied and relational dimensions [32,33]. These perspectives emphasise the importance of emotional responses, personal histories and social interactions in facilitating or hindering transformation. When applied to sustainability and disaster preparedness, transformative learning provides a useful framework for examining how individuals navigate the tensions between preventive and adaptive approaches [34,35]. Severe weather events or disaster-related experiences can function as disorienting dilemmas that redirect attention from collective, future-oriented sustainability efforts towards more immediate, individualised preparedness practices [36]. Understanding these dynamics provides insight into how learning and behavioural shifts unfold in the context of climate disruption, informing educational and policy strategies aimed at strengthening resilience and fostering sustainable action.

4. Materials and Methods

After having examined the macro and meso levels of the intersections between sustainability and disaster preparedness—both at the policy-conceptual and the scholarly level—the focus of the empirical study now shifts to the individual level. At this level, the two concepts are often considered separately [9,37] and are primarily investigated using standardised questionnaires or semi-structured interviews to assess risk perceptions, self-efficacy beliefs and other explicit attitudes in these areas [38,39,40].

From the perspective of Praxeological Sociology of Knowledge [13], these studies foreground ‘communicative knowledge’ [41] (p. 289)—knowledge that is consciously accessible, reflects normative action frameworks, and corresponds to common-sense theories that can be compared and evaluated across actors for their factual and normative validity [41] (p. 88), [42] (p. 120), [43] (p. 203), [44] (p. 743). This form of knowledge does not refer to actors’ personal intentions, but to the ‘objective social configuration’ [45] (p. 46) that exists independently of their individual motivations and characteristics [46].

For the present research question, however, ‘atheoretical knowledge’ is central [47]. This tacit, pre-reflective knowledge shapes everyday practice through routine action [48] (p. 15). Although difficult to articulate theoretically, actors can nevertheless draw upon it in their behaviour [43] (p. 198). At the same time, this implicit knowledge connects individuals through shared practices and experiences, forming collectively shared orientations among those with similar backgrounds [46], which creates a ‘conjunctive space of experience’ [41] (p. 216).

To systematically reconstruct these implicit orientations in the context of sustainability and disaster preparedness—and thus move beyond general common-sense knowledge [46]—this study foregrounds individuals’ situated practices within their biographies and milieus. The empirical basis is a biographical narrative interview, conducted according to [12] with ‘Lukas Sandner’, an individual who self-identifies as engaged in disaster preparedness. Lukas Sandner is a pseudonym; all personal identifiers and context details that could enable re-identification (e.g., workplace, municipality, specific organisational affiliations) were anonymised in accordance with the data protection agreement. This case study forms part of a broader qualitative research project examining biographical learning and educational processes among individuals engaged in disaster preparedness in Germany. This particular case was selected because it reveals pronounced shifts between collective sustainability engagement and individual preparedness, making the underlying negotiation processes analytically traceable. The ethics committee of RPTU confirmed in writing that no formal vote was required for this study. To ensure reliability and reflexivity, the analysis adhered to the systematic, multi-step procedure of the documentary method [13,49] and was supported by collaborative interpretation sessions within the research team. These sessions helped to maintain transparency and minimise researcher bias. The biographical narrative interview format begins with an open, non-directive prompt, inviting the interviewee to recount his or her life story in his or her own way [12]. By enabling respondents to speak freely about any aspect of their life, narrative interviews allow extended experiential periods or even complete biographies to be captured from the interviewee’s perspective [46]. In this study, this approach enabled Lukas’ formative experiences and key life stages to emerge according to their personal relevance, rather than following a pre-set chronological sequence. Consequently, we gain profound insights into his habitual modes of action, implicit attitudes, and the contextual factors that influence his decisions and practices in disaster preparedness and sustainability. The interview took place at Lukas Sandner’s home at the end of November 2024. It was conducted in German (the interview quotes in this article have been translated into English) and lasted 89 min. After transcription, the data was prepared and processed in accordance with the data protection agreement. The data was analysed using the documentary method, developed by Ralf Bohnsack as a research methodology [13], also referred to as Praxeological Sociology of Knowledge, which we have previously mentioned in this article. Bohnsack has also developed a practical evaluation method [50], which Nohl further developed for evaluating narrative interviews [44]. Implementing the Documentary Method’s two interpretation steps of formulating interpretation (FI) and reflective interpretation (RI) made it possible to capture the ‘objective meaning’ [46] (p. 201) by reconstructing what Lukas said about the topics (FI). In the RI, the ‘how’ Lukas talks about the topics was interpreted to reconstruct the ‘documentary meaning’ [46] (p. 201) along with his implicit orientations. Although the documentary method usually involves a comparative analysis of cases, both within and across them [46], our study uses a single-case design. We contextualise Lukas Sandner’s interview findings against insights from prior research—an approach analogous to evaluating initial interviews in larger studies [46]. This approach has limitations, particularly with regard to the generalisability of our results, and requires critical reflection on our own perspective. Nevertheless, we consider this method appropriate, as it enables us to trace individual perspectives within their collective experiential framework, providing valuable insights into our research question.

While this case study focuses on an adult biography, the documentary reconstruction of tacit orientations also provides insights relevant to youth learning. By highlighting everyday practices and environments through which implicit knowledge is transmitted across generations, entry points for disaster preparedness and sustainability education can be created.

5. Results

5.1. Family Background, Early Childhood and First Encounters with Preparedness

Lukas Sandner was 60 years old at the time of the interview. He grew up in the 1960s and 1970s with his parents and brother. In retrospect, he describes his childhood as “normal” (l. 22). Similarly, he glosses over his school years in just two lines (ll. 23–24), suggesting that he does not view that time as pivotal to his biography. Nevertheless, his childhood ‘penchant’ (l. 25) for stockpiling supplies reveals an early interest in security, which he attributes to the debates about nuclear war during that era. As a young teenager, he took his first precautionary measures by hiding tins of peas in his playroom—an act that both demonstrated his preparedness instinct and hinted at his awareness that this habit might cause conflict with his family in the future.

Even then, he was convinced that “you have to keep a supply” (ll. 28–29), a belief reinforced by his maternal grandmother, with whom he had a close relationship (“good rapport”, ll. 30–31), and who repeatedly urged him to eat “before bad times come” (ll. 32–33). He found her warnings “annoying” (l. 32) as a child but now regards them as a “formative influence” (l. 34), contrasting her first-hand memories of two world wars and the hunger years in between with his own upbringing in peace and prosperity (ll. 34–38). He dimly recalls his paternal grandmother running a large garden, yet he still credits it as an early “pre-conditioning” (l. 43). He cannot fully explain why he focused so much on disaster preparedness at that age, but he suspects it is “somehow in the genes” (ll. 116–117).

5.2. Adolescent Sensitization: Cold-War Debates and Civil-Defense

When the rearmament debate peaked in the 1980s, his interest “manifested” (l. 119). On the one hand, films about a nuclear attack on England, especially ‘The Day After’, acted as “amplifiers” (l. 138); on the other hand, a constant stream of alarming information, a civil defence course at his school, and the booklet he “devoured” (l. 144) heightened the “great fear” (l. 125) in society, which he believed to be legitimate, making him ever more “sensitised” (l. 126).

He identifies two resulting orientations. First is individual preparedness, which he pursued far less vigorously at that time, due to limited resources and a lack of interest among his peers (ll. 129–131). Second is the political route of peace activism and climate protection, which he prioritised at that time, in order to “make sure it doesn’t come to that” (ll. 132–133). His preparedness interests conflicted with those of his family: his brother was “not into it at all” (l. 44), and both his parents dismissed his efforts as ‘nonsense’ (l. 128), with his father calling him “crazy” (l. 148). Even among friends, he found himself “alone” (l. 158) on the topic of disaster preparedness, in contrast to debates about peace politics, environmental protection, climate protection, and the energy transition, which would shape his subsequent biography.

5.3. Professionalisation in Environmental Protection

He joined a nature conservation association, quickly rose to its board and oriented his university studies in spatial planning toward these themes. He then took up a professional position with the state-level environmental and conservation organisation in his home region. After meeting his future wife in 1995, he relocated to Karlsruhe, started a family, and continued his volunteer climate and environmental work, simply swapping local chapters and social circles as he moved. His private contacts were shaped by his activism.

Professionally, he progressed from a scientific post at the university to a position with the City of Ludwigshafen and ultimately to an executive leadership role in a consortium of environmental associations. He then held various energy management positions before taking up his current role in his municipality’s climate protection office, which he still holds. His career demonstrates a steady professionalisation in environmental protection. Up until 2018, he viewed his commitment as a biographical constant—“my topic from the beginning, even as a teenager” (ll. 50–51).

5.4. The Disorienting Dilemma: Basement Flooding as a Catalyst for Disaster Preparedness

However, the year 2018 proved to be the starting point of a disorienting dilemma. A heavy rainfall event flooded Lukas’ basement and, with it, something in him “switched” (l. 77). He was “pretty angry” (l. 260) when he realised that the climate protection work he had devoted thirty years to had not been given sufficient attention. It was no longer “theoretical” (ll. 258–259)—he had to act. Although he had long resisted adaptation measures—“I thought we’d already lost” (ll. 266–267)—the flooding made disaster preparedness his central focus, prompting him to conclude, “Now I’ve lost here; I’ve got to do it myself” (ll. 267–268). He made a “pretty brutal pivot” (l. 268) from collective sustainability—community action to avert disaster and secure a livable environment for current and future generations—to individualist civil protection, focusing on safeguarding his property and family.

5.5. Balancing Personal Readiness with Community Engagement

He concentrated on structural measures, stockpiling, and mental planning, guided by scenarios of gradual climate collapse and a blackout. Although he had volunteered for climate protection since his youth, he initially remained a solitary figure on his informational journey and in his concrete disaster-preparedness actions: he read specialist books, passively consumed various prepper forums, calculated his family’s needs himself and became sceptical of state-led preparedness. He operated in “camouflage” (l. 783), was criticised by his family, yet persevered even when feeling “a bit embarrassed” (l. 396).

Another turning point arrived when, during the 2020–22 energy crisis caused by the 2020–22 pandemic, his household experienced the independence afforded by his adaptations. In 2022, drawing on his newly acquired expertise and his engagement with the local food council, he returned to the political arena, “daring” (l. 423) to address disaster preparedness and the question of food supply in a crisis in a collective forum.

5.6. The Kitchen Garden as Hybrid Strategy for Scarcity and Trust

His approach to food security now combines a rotating larder of fresh stock to minimise waste, with a kitchen garden driven by the foresight that some produce will become scarcer and more expensive. He refers to the kitchen garden as an “approach where I can do something” (l. 96) and “life insurance” (l. 480) in a crisis. Starting with an area of 30 m2, he and his wife now cultivate 350 m2 in total, combining their gardening expertise and passion with disaster preparedness. He also exercises his old missionary zeal through public talks on gardening and maintains a website called “Kitchen Garden in the Age of Global Warming” (ll. 530–531). Although he intends to expand his disaster preparedness outreach through lectures and newsletters, he fears that he may be “shooting himself in the foot” (l. 787) if a disaster were to strike. This illustrates both Sandner’s desire to share his knowledge and create a safer world for all, as well as his heightened awareness of his own assets and certain mistrust of others. Although he regards climate protection as his profession, he privately believes that “the train has already left the station” (l. 1031). Thus, Sandner’s biography traces a transformation—from early disaster preparedness and political activism, through environmental protection professionalisation, to individual disaster preparedness, and ultimately a hybrid of collective and individual strategies—illuminating the dialectic of prevention and adaptation, collective responsibility versus individual security, and self-efficacy versus institutional trust. Furthermore, it clearly demonstrates how current political discourse and geopolitical events can influence individuals’ actions and associated orientations.

5.7. Reconstructed Orientation Frameworks: Between Withdrawal and Contribution

A reconstructive analysis of Lukas Sandner’s biographical narrative reveals the frameworks that inform his approach to the relationship between sustainability and disaster preparedness. One prominent pattern is the shift from a collectively oriented sense of responsibility—shaped by earlier political engagement and sustainability ideals—towards a more individualised, pragmatically framed notion of self-responsibility. This shift represents not merely a biographical development but also reflects a documentary pattern of meaning, in which responsibility is primarily located where subjective control seems possible, i.e., in one’s own actions.

A pivotal moment in this reorientation was marked by a recent period of heavy rainfall, which Sandner describes as a turning point that shattered his previous belief in the long-term efficacy of climate protection efforts. His assertion that “we’d already lost” (ll. 266–267) encapsulates a profound sense of disillusionment and the perceived futility of sustainability measures aimed at mitigation. In its stead, a new orientation emerges, prioritising adaptation and personal readiness over systemic change. This reorientation can be viewed as a critical incident that triggered a profound restructuring of his interpretive framework.

This turning point illustrates how Sandner’s orientation shifted from mitigation to adaptation: the collapse of confidence in systemic solutions coincided with a reframing of resilience as an individual responsibility. Rather than continuing his engagement in collective climate movements, he focused his efforts on personal disaster preparedness, expressed through technical measures, stockpiling, and self-sufficiency practices. This is followed by a phase of highly individualised action: Sandner calculates his household needs, installs technical infrastructure, cultivates a substantial garden, and maintains a mental catalogue of emergency scenarios—all primarily carried out independently, without consultation or collaboration. His preparedness becomes an almost solitary practice, “camouflaged” (l. 783) to avoid misunderstanding or ridicule, driven by an ethic of competence and a lack of trust in public institutions. This pattern also echoes earlier stages of his biography: as a child and adolescent, his interest in stockpiling provoked derision, leading him to conceal his behaviour. However, at that time, this tendency was gradually reframed through collective environmental activism, enabling him to ‘mask’ his preparedness within a preventive, future-oriented commitment to sustainability. Seen in this light, his current approach is less a rupture than a dialectical return: a reactivation of earlier individual strategies, now embedded in a broader context of disillusionment with collective efficacy.

At the same time, however, traces of collective orientation remain. He resumes public communication efforts via talks and a gardening website, yet maintains ambivalence toward openly sharing knowledge. Such moments point to a hybrid approach: while his actions become more individualized, his desire to contribute to broader resilience persists, albeit in a cautious and controlled manner. This tension between collective ideals and individualized responses is central to the reconstructed framework.

For example, Sandner interprets his heavy rainfall event experience as a pivotal event in which he perceived institutional promises of protection (e.g., from municipal authorities) as unreliable. He describes detailed technical measures for self-protection, such as pumps and structural precautions, and explicitly distances himself from others who relied on external support. The way in which he narrates this experience, marked by self-efficacy, technical control, and a critical stance towards collective solutions, reveals an orientation framework that conceptualises resilience as the result of individual preparation.

This orientation is further illustrated by Sandner’s intensive engagement with his kitchen garden, which he describes as a space of autonomy and self-sufficiency. Here, gardening is not only a practical form of food production, but also a symbolic act of reclaiming control in an increasingly unpredictable world. The garden thus developed into a material and emotional resource for navigating uncertainty, representing a personalised adaptation strategy grounded in technical knowledge and ecological practice. At the same time, its very form reveals a hybrid orientation: while the garden serves as a precautionary resource for crisis situations, it is also firmly grounded in ecological care and a deep connection to nature. Gardening therefore serves as a practice through which individual preparedness and sustainability-oriented values are integrated both materially and symbolically.

Sandner’s approach is characterised by a high degree of individualisation. Rather than seeking renewed forms of collective engagement in response to experienced crises, he doubles down on personal responsibility and control. Evidence of this appears in his disaster preparedness practices, his sceptical view of public institutions and his emphasis on competence and foresight as protective assets. His actions remain largely self-referential and localised, reinforcing the idea that security and resilience can be achieved primarily at an individual level.

These shifts are accompanied by a gradual withdrawal from collective action contexts, such as the environmental movement or political engagement in earlier life phases. Practices such as stockpiling, gardening, and using solar technology are not merely practical measures, but reflect a broader worldview that seeks security through self-regulation and independence.

Comparing Sandner’s past and present orientations suggests that transformative learning processes were triggered by a disintegration of expectations regarding collective action. In Mezirow’s terms [11,30], this shift can be understood as the outcome of a disorienting dilemma—in this case, an experience of profound disillusionment that necessitated a re-evaluation of previous assumptions. The reconstructed orientation patterns are also shaped by milieu-specific influences, such as Sandner’s technical education and his involvement in earlier sustainability discourses, which provide a context for learning and interpretation.

These patterns offer deeper insight into the current tension between sustainability and disaster preparedness: while sustainability-oriented narratives emphasise collective action and systemic transformation, crisis experiences tend to evoke increasingly individualised, risk-averse interpretive patterns. In Sandner’s case, however, these patterns are not contradictory or irrational, but rather meaningful within the orientation framework formed through biography, reflecting specific experiences of safety, control, and responsibility. His routines, particularly those related to the kitchen garden, can also provide opportunities for intergenerational learning, enabling children and young people to develop practical skills and an awareness of ecological issues.

6. Discussion

6.1. Transformative Learning Reconsidered

Sandner’s shift from engaging with collective sustainability to preparing for individual disasters can be interpreted through the lens of transformative learning. According to Mezirow [11,30], the 2018 heavy rainfall event experience acted as a disorienting dilemma—an existential crisis that challenged prior meaning structures and provoked critical reflection. Sandner’s statement that ‘we have already lost’ marks a turning point at which the importance of mitigation decreases and that of adaptation increases. His subsequent behavioural changes—constructing physical safeguards, stockpiling resources, and cultivating food—illustrate a reorientation in both content and epistemology: the locus of action shifts from systemic change to individual control.

However, the process appears less dialogic than Mezirow’s ideal of rational discourse suggests. Instead, it is shaped largely by biographical sedimentation and practical, embodied knowledge [32], indicating a combination of affective and cognitive transformation. While Mezirow emphasises intersubjective validation through discourse, Sandner’s transformation largely unfolds in solitude and is embedded in his life history. The learning observed here aligns with Cranton’s [33] description of self-directed yet emotionally embedded transformation, where personal history, existential threat and practical agency converge. This raises the question of whether such solitary, pragmatic reorientations should still be considered ‘transformative’ in the strong, communicative sense, or rather as adaptive learning shaped by affective experience.

Additional perspectives from the field of transformative learning can help to further illuminate these dynamics. For example, Brookfield’s work on ideology critique emphasises that transformations often occur under conditions of institutional constraint, disillusionment and the breakdown of collective meaning structures [51,52]. This resonates with Sandner’s interpretation of political inaction and institutional unpreparedness, which intensifies his sense of personal responsibility. Illeris’s three-dimensional learning model, which integrates cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions, helps to conceptualise how emotionally charged experiences—such as fear, frustration, or feeling overwhelmed—can disrupt existing meaning structures and enable new orientations to emerge [53,54]. Furthermore, Dirkx’s understanding of transformative learning highlights the importance of emotion, imagination, and unconscious processes [55,56], providing a useful perspective through which to view Sandner’s trajectory as being shaped more by embodied, affective, and imaginal forms of sense-making than by rational deliberation. Together, these perspectives broaden the analytical scope beyond Mezirow’s rational–discursive approach, highlighting the multifaceted emotional and experiential dynamics at play in Sandner’s learning trajectory.

When this perspective is applied to young people, existing research suggests that transformative processes in sustainability and disaster preparedness are typically shaped by social contexts rather than solitary reflection. Drawing on praxeological notions of conjunctive spaces of experience [13,41], young people are likely to negotiate disorienting events through family, school, and peer interactions, where tacit orientations are collectively formed and reshaped. Everyday practices such as gardening, household preparedness planning, or school-based resilience projects may therefore serve as experiential entry points, enabling youth to co-construct meanings that connect ecological care with practical preparedness actions [23,35,57].

Taken together, these reflections also highlight the need to more closely understand how different theoretical perspectives illuminate Sandner’s learning trajectory. Transformative Learning Theory helps to conceptualise the severe rainfall event as a disorienting incident that prompts a re-evaluation of previous assumptions. In contrast, the epistemology of practice sociology—serving as the overarching methodological framework—highlights how such reinterpretations are shaped by tacit, embodied and collectively shared orientations that have developed throughout Sandner’s life. The documentary method, as the instrument of this epistemology, reconstructs these implicit, collectively shared orientations by distinguishing between formulated and documentary meanings in the narrative. From this perspective, learning is understood as both a process of conscious reflection and the activation, negotiation and transformation of habitualised, socially embedded stocks of practical knowledge. Combining these frameworks therefore provides a more comprehensive account of Sandner’s trajectory, revealing how transformative shifts unfold at the intersection of reflective meaning-making and deeper biographical and collective dispositions that guide action beneath the level of explicit awareness.

In addition to these transformative learning perspectives, Sandner’s experiential shift can be understood through the lens of coping and resilience theory. From a coping perspective, his adoption of individually controlled preparedness strategies resembles problem-focused coping, which is aimed at regaining agency in uncertain conditions [58]. At the same time, his gradual reorientation can be linked to dynamic understandings of resilience, which conceptualise adaptation as an ongoing process of reorganising one’s practices and sense of efficacy in response to disruption rather than as a return to balance [59]. Integrating these perspectives reveals that Sandner’s learning trajectory encompasses cognitive and emotional reinterpretation, as well as adaptive efforts to restore a sense of control and continuity amidst perceived institutional inadequacies.

6.2. From Collective Visions to Individualized Responsibility: Structuring Contexts

The individualised orientation that emerges from Sandner’s narrative is not simply a personal choice, but is shaped by broader meso- and macro-level conditions. At the macro level, the perceived erosion of political efficacy, delayed climate action, and institutional unpreparedness fuel deep scepticism towards public solutions [34,60]. Sandner’s narrative reflects these disillusionments, shifting from ‘the state will not protect me’ to ‘I must protect myself’.

This case also illustrates how disillusionment at the macro level—such as the perceived failure of climate governance—does not simply demobilise engagement, but catalyses new, albeit fragmented, forms of learning and adaptation. These shifts highlight the need to understand transformative learning as both a psychological process and a relational phenomenon shaped by systemic structures and their breakdown.

At the meso level, Sandner’s long-standing involvement with environmental organisations and municipal climate offices demonstrates how institutional proximity can enable and restrict learning. Although these networks initially reinforced collective sustainability narratives, they eventually failed to provide practical responses to imminent threats. Due to the absence of integrative educational or civil protection infrastructures, he was compelled to undertake preparations by himself. Thus, his case illustrates a learning process that unfolds amid the tension between collective frameworks and individual agency, a tension exacerbated by institutional fragmentation. Schools, youth groups, and municipal programmes can help counteract institutional fragmentation by creating co-learning spaces where (young) people rehearse collective preparedness while taking household realities into account.

6.3. Hybrid Orientations and the Limits of Self-Reliance

While Sandner’s actions since 2018 are characterised by withdrawal and self-protection, they do not represent total disengagement. His gardening website and local advocacy efforts demonstrate his ongoing commitment to contributing, albeit cautiously. This hybrid orientation, balancing autonomy and solidarity, mirrors broader societal shifts in resilience thinking [36,61]. It challenges the binary opposition between the individual and the collective, instead illustrating the negotiated and ambivalent pathways that individuals traverse in the face of climate disruption.

The kitchen garden, in particular, becomes a site of this negotiation; it embodies both pragmatic foresight and ethical commitment, serving as a material space where self-sufficiency and public education intersect. Sandner’s reluctance to fully ‘go public’ with his preparedness plans reflects a deeper ambivalence: he values sharing knowledge but remains wary of the personal risks involved. This highlights the limitations of adaptive self-reliance as a purely private strategy. At the same time, his concealment reflects a dual logic that was already evident earlier in his biography. It arises partly from a desire to avoid potential ridicule and partly from a precautionary approach reminiscent of prepper cultures, where secrecy is used as a protective measure against social or material vulnerability.

6.4. Reciprocal Dynamics Between Individual and Collective Action

Lukas Sandner’s trajectory illustrates how individual and collective orientations exist as interwoven dimensions of learning and action, rather than as mutually exclusive categories. Although his preparedness practices initially took place in solitude after the heavy rain in 2018, they remain deeply entangled with the collective contexts that shaped his earlier biography. His long-standing involvement in environmental organisations, municipal climate initiatives, and political networks provided the interpretive frameworks that have guided his environmental commitment for decades. Therefore, his shift towards individual preparedness does not represent a departure from collective responsibility, but rather a response to the perceived erosion of collective efficacy and institutional reliability.

At the same time, the results show that Sandner’s individual strategies generate experiential knowledge that subsequently re-enters collective spaces. His involvement with the local food council during the 2020–2022 energy crisis (ll. 400–402) and his public gardening talks and educational website (ll. 529–533) exemplify this process of recollectivisation. These activities demonstrate how expertise acquired through household-level preparedness can inform and enrich communal debates about food security, resilience, and local sustainability. In this sense, individual action becomes a laboratory for testing adaptive strategies that may later be shared, translated, or politicised in collective settings.

The case reveals a dialectical relationship: collective contexts shaped Sandner’s early orientations, experiences of systemic failure triggered an individualisation of responsibility, and individual adaptive capacities eventually flowed back into collective discourse. Rather than a linear movement from the collective to the individual, the findings point to cyclical processes in which personal and collective orientations mutually influence one another. Recognising these reciprocal dynamics is crucial for understanding how disaster preparedness and sustainability education can support both individual agency and collective capacity building.

This reciprocal movement also clarifies how Sandner’s trajectory embodies the broader dialectic between climate protection and disaster preparedness. His biographical shift from collective, prevention-oriented engagement to individually controlled adaptation practices reflects the changing balance between mitigation and preparedness in the face of climate disruption. However, this shift does not entail a simple replacement of one orientation by another: core value commitments to solidarity and collective responsibility remain remarkably stable and continue to inform how he interprets and enacts adaptation. Individual preparedness here appears less as a withdrawal into self-interest than as a reconfiguration of solidaristic orientations under conditions of perceived institutional fragility. This suggests that broader collective value orientations can cut across the prevention–adaptation divide and shape how both are lived in practice. Such a perspective is particularly relevant for debates on ‘social prepping’. In psychological research, this term refers primarily to beliefs about competition, social threat, and breakdown of cooperation under conditions of crisis [62]. The present case, however, suggests that preparedness can also be grounded in more enduring solidaristic value orientations, opening up a more collective understanding of social prepping in which individual adaptive practices are explicitly linked to mutual aid and communal responsibility. Thus, the case shows how the tension between prevention and adaptation is negotiated not only at the policy or societal level, but also experientially and interpretively across an individual’s life course, and how macro-level discourses on sustainability and risk reduction are translated, reframed, or resisted at the micro level.

To contextualise these findings within the contribution of the study, this case also demonstrates how the proposed analytical matrix (individual/collective × prevention/adaptation) (see Figure 1) helps to capture hybrid orientations that evolve in response to climate disruption. By tracing how individual practices are shaped by—and in turn feed back into—collective frameworks, the analysis illustrates how macro-level sustainability and DRR discourses are translated and reconfigured at the micro level. This highlights the study’s broader contribution: offering an empirically grounded perspective on how individuals negotiate the tension between climate protection and disaster preparedness, thereby advancing research that has predominantly examined this relationship from institutional or policy-oriented perspectives.

6.5. Implications for Education and Civic Resilience

Sandner’s case suggests that transformative learning in the context of climate adaptation requires more than individual reflection; it depends on supportive learning environments being available. Adult education and civic learning infrastructures must engage with the realities of disillusionment and institutional mistrust, while also fostering spaces for critical exchange and re-collectivisation. As Kagawa and Selby [35] and Taylor and Cranton [33] argue, sustainability education must address both the ‘what’ of content and the ‘how’ of orientation, i.e., how individuals locate themselves in relation to collective futures.

Educational approaches that bridge the micro and meso levels—personal readiness and community engagement—may help to reconnect individual agency with broader democratic and ecological visions. In this regard, Sandner’s journey offers a cautionary yet hopeful perspective: transformation is possible, but it requires relational infrastructures that can encompass complexity, ambivalence, and action.

7. Conclusions

The case of Lukas Sandner illustrates the dynamics described in the title of this article, namely diverging responses to climate disruption. His learning trajectory exemplifies a shift from a prevention-oriented, collective approach to risk towards a more adaptation-focused, individualised one. It also reveals how such shifts are shaped by biographical experience and systemic disillusionment, and how these factors influence individual learning processes in the context of climate disruption. His transition from collective involvement to personal preparedness reflects an affective, embodied, and ambivalent learning trajectory that partially aligns with transformative learning theory [11], while also challenging its assumptions about discourse and rationality.

His hybrid approach, characterised by personal preparedness and selective civic engagement, raises important questions for sustainability education. How can learning spaces be created that acknowledge institutional mistrust without reinforcing isolation? How can individual and collective resilience be meaningfully connected?

The case of Sandner elicits the question of whether tendencies towards political despair about climate change [63] and climate-oriented burnout [64] are not turning into pragmatic decisions to adopt individual strategies of self-protection. Limited personal resources, especially the time available for civic engagement, appear to support this shift from collective, long-term goals to concrete, short-term goals whose successes are immediately visible. As Sandner’s trajectory shows, it can involve a gradual shift from preventive measures to adaptive practices in response to the consequences of climate change and related natural disasters. This illustrates a rebalancing between collective and individual goals, accompanied by a reduced commitment to collective climate protection. While the combination of prevention and adaptation may appear pragmatic at the political level, it fails to capture the contradictory tendencies evident at the individual level. While these insights cannot be generalised from a single case, they resonate with broader dynamics, in which political disillusionment and resource constraints can encourage people to withdraw from collective climate protection efforts.

Beyond the adult case presented here, conceiving preparedness and sustainability as a dynamic matrix (individual/collective × prevention/adaptation) (see Figure 1) suggests how orientations may be shaped across life stages. This perspective also indicates potential educational opportunities for children and young people, where intergenerational, practice-based learning can help connect individual agency with collective resilience.

From a methodological perspective, the case study design allows for an in-depth reconstruction of implicit orientations and does not aim at generalisability. The results are preliminary explanatory approaches that serve as a basis for further theoretical considerations and empirical studies to validate them, or for further studies with contrasting cases and comparative settings that examine how such orientations arise in different social environments. Nevertheless, Sandner’s biography illustrates how individual life paths reflect the tensions between prevention and adaptation, revealing the ways in which biographical experiences and structural conditions intersect to shape preparedness strategies. More broadly, the case study reflects a broader transformational process in which limited resources at the individual and collective levels can undermine solidarity-based prevention measures and encourage individualised adaptation strategies, thereby producing polarising tendencies. This highlights the need to conceptualise climate-related learning as a dialectical process shaped by disillusionment, structural constraints, and the search for resilience, rather than merely as a matter of individual agency.

Taken together, the case demonstrates that the negotiation between collective climate protection and individual disaster preparedness is not merely a personal shift, but embodies the broader tension between prevention and adaptation. Sandner’s trajectory illustrates how disillusionment with collective structures, transformative experiences such as flooding, and long-standing personal beliefs converge to reshape environmental commitment. By tracing the reinterpretation of collective, prevention-oriented ideals into individually enacted adaptation strategies, the study shows how macro-level discourses on sustainability and disaster risk reduction are translated, reframed, or resisted at the individual level. These findings emphasise the importance of integrated educational and policy approaches that recognise this interplay, supporting individuals and communities in navigating the complex relationship between collective responsibility and private resilience.

Future research should build on this single-case analysis by adopting comparative or multi-case designs to capture a broader range of biographical trajectories, social environments and regional contexts. Such studies could help to identify common patterns in how individuals negotiate the tension between collective climate protection and individual preparedness, as well as divergences shaped by social position, institutional trust or disaster experiences. Longitudinal and youth-focused studies would further deepen our understanding of how these attitudes evolve throughout life and across generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and S.L.; methodology, S.L.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation/interview, S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and S.L.; supervision, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as a non-interventional, minimal-risk qualitative interview study involving adult participants, in which no sensitive personal or medical data are collected and all participants provided written informed consent including data protection information, by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences at RPTU University of Kaiserslautern-Landau.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for anonymized publication of the data was also obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Participants had agreed to their data being used anonymously in publications, but not for general data sharing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jessica Matvienko and Aron Schady for their support in proofreading and checking the formal requirements of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction: Resilience Pays: Financing and Investing for Our Future; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi, N.; Arévalo, P.; Pamies, S. The Fiscal Impact of Extreme Weather and Climate Events: Evidence for EU Countries; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Wen, J.; Wan, C.; Ye, Q.; Yan, J.; Li, W. Disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation and their linkages with sustainable development over the past 30 years: A review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, economy and society: Fitting them together into sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Sardar Khan, A. Integrating sustainable development goals with the management of natural and technological hazards and disaster risk reduction. In Geospatial Technology for Natural Resource Management; Kanga, S., Meraj, G., Kumar Singh, S., Farooq, M., Nathawat, M.S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 83–131. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Disaster Risk and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/drr-focus-areas/disaster-risk-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Forino, G.; von Meding, J.; Brewer, G.J. A conceptual governance framework for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction integration. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2015, 6, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Fang, M.; Liu, L.; Chong, H.; Zeng, W.; Hu, X. The development of disaster preparedness education for public: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüttenauer, T. More talk, no action? The link between exposure to extreme weather events, climate change belief and pro-environmental behaviour. Eur. Soc. 2023, 26, 1046–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, F. Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. Neue Prax. 1983, 13, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Praxeologische Wissenssoziologie; (UTB Erziehungswissenschaft, Sozialwissenschaft: Bd. 8708); Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- United Nations (UN). Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development; United Nations: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1992; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Hopwood, B.; Mellor, M.; O’Brien, G. Sustainable development: Mapping different approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Azeiteiro, U.; Alves, F.; Pace, P.; Mifsud, M.; Brandli, L.; Caeiro, S.S.; Disterheft, A. Reinvigorating the sustainable development research agenda: The role of the sustainable development goals (SDG). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. 2017. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/terminology/disaster-risk-reduction (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. 2009. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Yamori, K. Promoting Everyday-Life Preparedness; Nakanishiya: Kyoto, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, K. Situating preparedness education within public pedagogy. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2017, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/46052_disasterriskreductioninthe2030agend.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Kitagawa, K. Connecting Disaster Risk Reduction, Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Transforming Universities for a Changing Climate. Working Paper Series, 2. 2021. Available online: https://www.climate-uni.com/_files/ugd/8240a4_602602131bb04c139e5a332452279b30.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Hannig, N. Kalkulierte Gefahren: Naturkatastrophen und Vorsorge Seit 1800; Wallstein Verlag: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). International Cooperation in Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/media/74265/download (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Allan, S.; Baylay, E. Opportunity Cost of COVID-19 Budget Reallocations: Cross-Country Synthesis; Centre for Disaster Protection: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sasse-Zeltner, U. The revival of solidarity in disasters: A theoretical approach. Cult. Pract. Eur. 2021, 6, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, J. What if we stopped pretending? The New Yorker, 8 September 2019. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-if-we-stopped-pretending (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1997, 1997, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.W.; Cranton, P. (Eds.) The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice; Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dirkx, J.M. Transformative learning theory in the practice of adult education: An overview. PAACE J. Lifelong Learn. 1998, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cranton, P. Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning: A Guide for Educators of Adults; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didham, R.J.; Ofei-Manu, P. Adaptive capacity as an educational goal to advance policy for integrating DRR into quality education for sustainable development. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 47, 101631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, F.; Selby, D. Ready for the storm: Education for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation and mitigation. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R. Sustainability learning: An introduction to the concept and its motivational aspects. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2873–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. Promoting sustainability: Towards a segmentation model of individual and household behaviour and behaviour change. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-S.; Feng, J.-Y. Residents’ disaster preparedness after the Meinong Taiwan earthquake: A test of protection motivation theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyosawa, J.; Takehashi, H.; Shimai, S. Structure of disaster preparedness motivation and its relationship with disaster preparedness behaviors. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2024, 66, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. Strukturen des Denkens. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft: Bd. 298; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Orientierungsschemata, Orientierungsrahmen und Habitus. In Qualitative Bildungs- und Arbeitsmarktforschung; Schittenhelm, K., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 119–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffer, B. Dokumentarische Methode: Einordnung, Prinzipien und Arbeitsschritte einer praxeologischen Methodologie. In Handbuch Qualitative Erwachsenen- und Weiterbildungsforschung; Schäffer, B., Dörner, O., Eds.; Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2012; pp. 196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nohl, A.-M. Interview und Dokumentarische Methode; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. On the interpretation of Weltanschauung. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Kecskemeti, P., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 33–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nohl, A.-M. Narrative interview and documentary interpretation. In Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method in International Educational Research; Bohnsack, R., Pfaff, N., Weller, W., Eds.; Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2010; pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, K. Wissenssoziologie: Auswahl aus dem Werk. In Soziologische Texte: Band 28; Wolff, K.H., Ed.; Luchterhand: Munich, Germany, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Qualitative Bild- und Videointerpretation: Die dokumentarische Methode, 2nd ed.; UTB Erziehungs- und Sozialwissenschaft; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2011; Volume 8407. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Documentary method and group discussions. In Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method in International Educational Research; Bohnsack, R., Pfaff, N., Weller, W., Eds.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2010; pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung: Einführung in qualitative Methoden, 10th ed.; UTB Erziehungswissenschaft, Sozialwissenschaft; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2021; Volume 8242. [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield, S. Transformative learning as ideology critique. In Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Mezirow, J., Associates, Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield, S. The Power of Critical Theory: Liberating Adult Learning and Teaching; Open University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Illeris, K. Towards a contemporary and comprehensive theory of learning. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2003, 22, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illeris, K. Transformative learning and identity. J. Transform. Educ. 2014, 12, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, J.M. The power of feelings: Emotion, imagination, and the construction of meaning in adult learning. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2001, 2001, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, J.M. Engaging emotions in adult learning: A Jungian perspective on emotion and transformative learning. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2006, 2006, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, K. Learning and teaching of climate change, sustainability and disaster risk reduction in teacher education in England and Japan. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2023, 25, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughter, P. Unmaking Disasters: Education as a Tool for Disaster Response and Disaster Risk Reduction. UNU-IAS Policy Brief No. 6. United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability. 2016. Available online: https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5705/PB6.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).