Abstract

This study examines public awareness and acceptance of Hyperloop technology in Poland as a potential low-emission and energy-efficient mode of future transportation. Based on a survey of 1000 respondents, this study examines five key dimensions: general openness to next-generation transportation solutions, awareness of the Hyperloop concept, perceived need for innovation in the transportation sector, willingness to use Hyperloop, and expectations regarding environmental benefits. The study results indicate that Polish society generally holds positive attitudes toward innovative transportation, encompassing attitudes, needs, willingness, and environmental perceptions. However, awareness of Hyperloop remains relatively low at only 15%. Differences between groups are statistically significant but small in terms of effect size, indicating that the overall attitude is generally positive across the population. This article contributes to the literature on the social acceptance of transportation innovations, providing a foundation for further communication and educational initiatives that support sustainable mobility. This study emphasizes the importance of targeted communication strategies, particularly for groups with low awareness, and highlights the role of the environmental context in promoting public acceptance. These findings contribute to understanding public readiness for sustainable transport innovations.

1. Introduction

The transportation sector is at the forefront of international efforts toward a sustainable energy transition, driven by the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The transportation sector is among the highest energy-consuming industries, contributing significantly to CO2 emissions and almost one-third of global final energy consumption, particularly in high-income countries [1]. Despite improvements in energy efficiency in some sectors, overall energy demand for transport continues to rise due to growing mobility demands, expanding logistics networks, and the use of fossil fuels as a primary energy source. These dynamics underscore the need for systemic innovation at the intersection of energy policy and mobility, posing a significant obstacle to decarbonization strategies [2].

Energy efficiency, zero emissions, and low environmental impact are key goals for future transportation systems; ideally, these should be achieved without sacrificing accessibility or economic competitiveness. Radical technological changes are necessary to achieve these goals, particularly those that decouple transportation from fossil fuels and integrate renewable energy sources more broadly [3]. Hyperloop technology, as a concept for ultrafast terrestrial mobility, is increasingly being considered in this context. This is due to its impact on energy consumption and efficiency in long-distance travel, as well as its potential to revolutionize passenger and freight transport [4,5].

Innovative transportation solutions employ a diverse range of technologies designed to reduce CO2 emissions and enhance energy efficiency. Key among these are electric and autonomous vehicles equipped with advanced energy management and route optimization systems, which dramatically reduce energy consumption, thereby minimizing waste from energy sources and exhaust emissions. Trucking and maritime transport are increasingly experimenting with hydrogen propulsion technologies as one of several low-emission alternatives to conventional fuels, particularly in segments where electrification remains challenging [6]. The aviation industry is developing aviation biofuels and hybrid electric aircraft, which can dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of this type of transportation [7]. Renewable energy-powered urban rail and tram systems are becoming increasingly important in urban areas, contributing to the decarbonization of public transport [8]. Furthermore, demand for passenger cars could be declining, while ultra-light electric urban vehicles, such as e-bikes and e-scooters, are gaining popularity. The Hyperloop project has garnered increasing attention and prominence in the scientific and technical communities in recent years, and research on this technology is advancing rapidly, indicating the growing potential of this groundbreaking transportation solution for the future [9].

Using magnetic levitation to propel the capsules through low-pressure vacuum tubes, the Hyperloop system can reach speeds of up to 1200 km/h while significantly reducing rolling resistance and aerodynamic drag. Compared to traditional forms of transportation, this special configuration provides considerably lower energy consumption per pkm. Current projections suggest that Hyperloop systems could operate with an energy intensity of just 10–50 Wh/pkm, which is significantly lower than commercial aviation and high-speed rail [10]. Furthermore, regenerative braking technology lowers operating costs and net energy demand while increasing energy efficiency [11]. Hyperloop’s compatibility with renewable energy systems is one of its most promising features. Energy-sufficient infrastructure can be built using integrated solar panels, wind farms, or hydrogen storage [12]. In this sense, Hyperloop contributes to energy security, diversification, and a broader transition to clean and decentralized energy systems, while also addressing the need for decarbonization. These features make Hyperloop an innovation in transport and energy, highly compatible with national and European energy transition initiatives.

Janić [5] indicates that the total energy consumption of Hyperloop capsules increases linearly with the distance of the journey. Hyperloop is more energy-efficient than air passenger transport and some intercity rail systems, particularly over longer distances and with higher passenger loads. Furthermore, the energy efficiency of Hyperloop can be improved by increasing passenger capacity, optimizing propulsion and levitation, and utilizing low-emission energy sources, e.g., solar panels, which can reduce CO2 emissions. Walker [13] also highlights the potential of powering the Hyperloop with renewable energy, suggesting that the system could be self-sufficient. However, such an approach is likely unrealistic in regions with higher latitudes or less sunny climates, such as the UK.

However, beyond technical potential, public opinion, political will, and social engagement will be crucial for the successful implementation of Hyperloop. According to recent research, public acceptance is crucial for the widespread adoption of energy-efficient and low-carbon technologies, particularly in areas with significant infrastructure impacts and high social visibility [14,15]. Public support influences policy direction, investment attractiveness, and whether innovations become widely accepted and commercially viable. Even the most energy-efficient technologies may encounter opposition or be omitted from political priorities in the absence of social legitimacy [16].

Although public opinion is crucial for the energy transition and for emerging concepts like Hyperloop—particularly in terms of how societies perceive them and their role in transforming transportation—little is known about how people view new low-emission transport technologies from an energy and environmental perspective. Previous research has primarily examined public acceptance of more mature sustainable transport technologies, such as electric, hydrogen, and autonomous vehicles, identifying factors including perceived safety, affordability, trust in technology, and environmental awareness as key determinants of adoption [17,18]. Studies have also shown that acceptance is strongly influenced by socio-cultural context, with factors such as institutional trust, environmental concern, and familiarity with innovation playing important roles [19,20]. However, empirical evidence remains limited when it comes to emerging concepts like Hyperloop, particularly regarding how societies perceive their energy efficiency, ecological benefits, and alignment with broader sustainability transitions. Most studies to date have focused on Western European or Asian contexts, leaving Central and Eastern Europe underexplored in this regard [21].

These differences stem from the region’s distinctive developmental trajectory and socio-technical conditions. Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, including Poland, have historically relied on coal-based energy systems, which have shaped both public discourse and institutional approaches to decarbonization. The legacy of centralized planning and delayed infrastructure modernization has contributed to uneven public trust in large-scale technological projects and a cautious approach toward disruptive innovations. Moreover, limited exposure to advanced transport systems, combined with relatively lower levels of public participation in energy and infrastructure decision-making, affects how citizens perceive and evaluate new low-emission technologies. These contextual factors make the CEE region a particularly relevant case for studying the social acceptance of emerging sustainable transport solutions, such as the Hyperloop.

Moreover, most current research focuses on technological or financial feasibility, often overlooking the complex aspects of social acceptance, including environmental awareness and concern, emotional readiness, perceived usefulness, and the values associated with innovation. There is a lack of reliable information on how different demographic groups evaluate innovative transportation technologies in terms of their environmental potential, usefulness, and overall societal demand for innovation. This is particularly evident in Poland, where systemic decarbonization is ongoing, and public discussion about advanced transportation systems is limited.

This study, which examines public awareness and acceptance of the Hyperloop concept in Poland, focuses on perceptions of environmental and energy issues, thereby filling a gap in the existing literature. The study examines the attitudes of different demographic groups to better understand how energy issues and sustainability values shape public opinion, unlike previous studies that lacked demographic diversity. Integrating public perceptions with energy innovations in the transportation sector contributes to the study’s knowledge base. Although Hyperloop has often been analyzed from a technical or infrastructure perspective, the study highlights how public openness and environmental expectations significantly impact the feasibility of implementing energy-efficient transportation systems. This study expands our understanding of the social factors that facilitate or hinder the implementation of innovative low-carbon technologies by situating public opinion within the broader context of sustainable mobility and energy transition, particularly in the under-researched region of Central and Eastern Europe. Policymakers and industry stakeholders seeking to link technological progress with social support and long-term sustainability goals will find this contribution particularly relevant.

The article follows a conventional structure typical of empirical research papers, comprising the following sections: Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges and the Need for Innovation in the Transport Sector Within the Framework of Sustainable Development

While playing a pivotal role in economic development, the transport sector simultaneously has significant consequences for the natural environment [22]. The necessity of reconciling the growing demand for mobility with the requirements of sustainable development forces this sector to face various challenges [23]. Factors such as the rapid pace of urbanization, the intensification of global freight flows, and climate change compel a transformation of traditional transport models toward more efficient, low-emission, and socially acceptable solutions.

One of the fundamental challenges is reducing the negative environmental impacts of transportation, for which modern technologies may provide an adequate response [24]. Electric vehicles, AI-driven traffic management systems, and vacuum-based transport concepts, such as Hyperloop, are becoming increasingly desirable and indispensable.

At the same time, social and organizational innovations are gaining importance, focusing on equitable access to transport services, reducing mobility-related exclusion, and supporting public participation in infrastructure planning processes [25]. Thus, what is required is not only a technological revolution but also a paradigm shift in the perception of mobility as a public service that considers the needs of diverse social groups. In this context, implementing innovative transport solutions should be preceded by a comprehensive assessment of their environmental, economic, and societal impacts. Only a holistic approach (integrating ecological, economic, and social objectives) can ensure the long-term sustainability and acceptance of new mobility models.

2.2. Environmental Implications of Hyperloop Transportation Systems

The dynamic development of technological innovations in the transport sector creates new opportunities for modifying, optimizing, and implementing advanced solutions within existing transportation systems. Contemporary approaches to vehicle design increasingly rely on interdisciplinary applications of the latest scientific advancements, both in enhancing existing systems and in shaping entirely new concepts of mobility. The growing interest in automation, electromobility, zero-emission systems, and digital integration signals a strong trend toward developing sustainable, intelligent, and highly efficient modes of transportation. However, developing these technologies requires technical innovation and appropriate adaptation to modern technical, economic, and environmental requirements.

Rail transport is often presented as the long-distance mode with the lowest greenhouse gas emissions. However, this impact depends on the energy source that powers the railway (diesel or electricity) and the vehicle’s occupancy rate. In general, trains transport goods and passengers with a limited environmental footprint compared to other long-distance transport modes [26,27,28]. However, railways have limited capacity, and increasing or introducing high-speed rail often requires constructing new lines, which has a significant impact on the landscape and environment [29,30].

According to the United States Department of Energy [31], Hyperloop systems may influence energy consumption in the transportation sector in two ways: first, through modal switching, in which passenger or freight demand may move to Hyperloop from existing modes such as road, air, rail, or maritime transport; and second, through induced or additional demand, whereby new passenger trips or freight movements may emerge due to increased capacity, improved service quality or reliability, or lower costs of the latest systems compared to alternatives.

Beckert et al. [28] conducted a life cycle analysis (LCA) of the Hyperloop system, indicating that it is an energy-efficient and low-emission option for high-speed passenger transport. Based on the LCA, which encompassed the construction, operation, and end-of-life phases, it was shown that Hyperloop can have very low greenhouse gas emissions (<8 g CO2/pkm), provided that the electricity comes from low-emission sources and passenger occupancy rates are relatively high. Hyperloop’s environmental performance is comparable to that of railways, providing similar transport services. Compared to air transport, its environmental impact is significantly lower (<5% of the climate change impact of conventional airplanes). These conclusions remain valid despite uncertainties related to technical characteristics and design decisions arising from the current stage of Hyperloop technology development. This system has the potential to combine the speed of airplanes with the low environmental footprint and capacity of railways, filling a significant gap in future transport networks and supporting climate goals in the transport sector. However, potential limitations need to be considered and clarified, including the technical feasibility of the proposed capacity and possible safety risks. Despite operating in near-vacuum conditions, Hyperloop still consumes a significant amount of energy, although far less than airplanes. Hyperloop generates limited particulate matter and requires less land than major competitors, such as long-distance trains and planes. When there is a need to increase transport capacity, especially at higher speeds, the question arises whether traditional transport systems can provide it or whether new, more sustainable alternatives should be considered.

Duda et al. [21] identified a series of technical and non-technical conditions that determine the development of high-speed vacuum train technology, using a technological road mapping method. This approach was used to analyze the planned implementation process of this technology in Poland. As a result of the analysis, 65 conditions were identified, grouped into four categories: legal, technological, economic, and social, and linked to 20 development pathways. These conditions were visualized on a roadmap that illustrates the process of developing high-speed vacuum train technology. The analysis showed that technical factors related to track infrastructure, stations, and vehicles play a dominant role; however, the development of technology is also determined by legal, economic, and social conditions. The study revealed that effective technology implementation requires managing all determining factors and minimizing the impact of those that can limit the development of other areas. The losses resulting from construction work should be considered in terms of the environmental impact. Still, due to the low emissions characteristic of this technology, significant environmental benefits are expected, including a substantial reduction of CO2 and a balance between benefits and environmental costs. Additionally, the development of high-speed vacuum train technology will impact the national R&D infrastructure, encompassing universities and research centres. Key milestones in this area include the establishment of a research consortium that brings together companies, universities, and research institutes, as well as the introduction of specialized training programmes that prepare personnel to operate the technology.

As part of a systematic review of the literature on Hyperloop technology, Premsagar and Kenworthy [9] examined technical, environmental, economic, and social implications, as well as the impact on urban planning and transport policy.

Regarding environmental impacts, the authors note that experience with conventional high-speed rail suggests that Hyperloop can create “barrier effects” in cities and limit the use of urban space, including green areas, if the development of areas around stations is not carefully planned. Adverse effects on agriculture near cities may also occur, which is particularly important in the rapid industrialization of urban agglomerations. They also point to technical limitations. According to the cited researchers, the literature suggests that a realistic Hyperloop speed is approximately 500 km/h, due to engineering constraints and passenger comfort considerations. Hyperloop vehicles have a limited capacity, with a theoretical maximum of 3360 passengers per hour at 30 s intervals. However, for safety reasons, the intervals may be extended to 80 s, reducing the capacity to 1260 passengers. Attention is also drawn to the high costs of construction and maintenance.

2.3. Public Awareness and Information Dynamics of Innovative Transport Technologies

The contemporary development of transport technologies generates significant changes in infrastructure and logistics, social perceptions, and the communication of innovations. In this context, social awareness refers to citizens’ knowledge, acceptance, and readiness to adopt new technological solutions in their everyday lives.

Research indicates that many individuals are unaware of the sustainable transport options available, which often leads to a habitual reliance on conventional means of transport, thereby forgoing more environmentally friendly alternatives [18]. Conversely, other studies suggest that individuals familiar with innovative technologies demonstrate higher levels of acceptance regarding their practical application [17,19].

Education and information campaigns, therefore, play a crucial role in building public trust in autonomous technologies and digital transport systems. Information dynamics in transport innovation are characterized by high variability and rapid dissemination. Media outlets, digital platforms, and mobile applications are becoming the primary communication channels, enabling society to access up-to-date data on traffic conditions, service availability, and the functionalities of emerging technologies. Nevertheless, research suggests that public attitudes toward innovative transport technologies tend not to shift rapidly [32].

However, the significance of safety concerns displays notable regional variation. European research [19,20] identifies perceived risks related to technical failure, high speed, and automation as key barriers to acceptance, while the Indian study [33] indicates that safety is less of a concern, which may reflect distinct risk perceptions and transport familiarity in different markets. Furthermore, Polish research [34] highlights how advanced engineering knowledge and awareness of current transport shortcomings can foster a more critical stance toward innovative technologies. This evidence suggests that technology acceptance is influenced by demographic characteristics, stakeholder professional backgrounds, and technical literacy, highlighting the importance of targeted communication and educational strategies for diverse social groups.

2.4. Socio-Technical Acceptance of Hyperloop: Environmental and Technological Perceptions

The aim of the study conducted by Duda [21] was to identify the technical and non-technical conditions influencing the development of vacuum-tube high-speed train technology. The author employed technological road mapping as the methodological approach. Using this method, the study analyzed the planned development process of vacuum-tube high-speed train technology in Poland. Duda et al. [21] (p. 416) note in their analysis of high-speed vacuum train technology development that it will have a significant positive social impact; however, its effective implementation requires achieving certain milestones. In particular, it is necessary to determine passengers’ permissible psychophysical burdens and determine the optimal level of the granularity of the network (distances between stations and frequency/circulation that together determine a capsule’s velocity). This technology should be perceived as a safe and widely accessible means of transport, capable of reducing travel time on specific routes by approximately two-thirds and decreasing commute time, thus contributing to increased workforce mobility. The researchers emphasize that expanding the transport network will promote the development of peripheral regions. Furthermore, they predict that the process of implementing the new transport technology will also foster business collaboration through intensified cooperation between companies within industries, closer cooperation between firms and universities, the creation of technology parks and development centres, the establishment of economic zones focused on vacuum train technology, and the formation of industrial clusters centred on this technology. At the same time, potential risks must be considered, including the country’s strong centralization resulting from a centralized transport network and the high environmental costs associated with building the entire infrastructure, which can limit the efficiency of technology implementation.

On the other hand, Premsagar and Kenworthy [9] point out that, from a social perspective, high ticket costs limit accessibility for the broader population. They also highlight limited travel comfort, potential terminal pollution, and a lack of integration with existing public transport, which can affect social acceptance.

Fajczak-Kowalska and Kowalska [35] view Hyperloop technology as an attractive alternative that could replace existing modes of transport. They emphasize the advantages of implementing this technology, highlighting the innovativeness of the solution, safety and collision avoidance, environmental friendliness, energy self-sufficiency, and provision of a high level of mobility. They state that Hyperloop may be the most effective means of transport, both economically and ecologically, and may offer a solution to contemporary transportation-related problems.

The reviewed literature highlights significant progress in understanding the technological and environmental potential of sustainable transport solutions, including the Hyperloop concept. Previous studies have consistently emphasized the advantages of such systems in terms of energy efficiency, emission reduction, and integration with renewable energy sources. They have also identified key determinants of public acceptance—such as safety perception, cost, environmental awareness, and trust in technological innovation.

Despite this progress, the literature remains heavily focused on technical feasibility and economic performance, while the social dimension of sustainable transport innovation has received much less empirical attention. In particular, there is limited evidence on how societies perceive new low-emission technologies from an environmental and energy perspective, as well as how demographic or contextual factors influence these perceptions.

Furthermore, most studies have been conducted in Western Europe or Asia, resulting in Central and Eastern Europe being underrepresented in research on the public acceptance of disruptive transport technologies. This region’s unique historical, infrastructural, and cultural characteristics—such as its dependence on fossil fuels, uneven modernization, and differing levels of public trust in large-scale innovations—make it a compelling context for exploration.

Addressing these gaps, the present study investigates public awareness and acceptance of the Hyperloop in Poland, examining how perceptions of innovation, environmental benefits, and energy transition interrelate. By situating the analysis within a Central and Eastern European context, the study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the societal factors that facilitate or hinder the adoption of sustainable transport technologies.

At the heart of the research process are research questions, which provide purpose and direction for the study. In addition to framing the research, a well-defined research question determines the research methodology, data collection techniques, and how the results will be interpreted. Creswell [36] argues that good research questions articulate the precise objectives of the study and address gaps in the existing literature. This study is therefore framed around several research questions aimed at examining:

- What is the general public attitude toward next-generation transport technologies, including Hyperloop, and how does it vary by socio-demographic factors?

- What is the current level of public awareness of Hyperloop technology, and which demographic groups are more or less aware?

- How do perceptions of the need for innovation in the transport sector influence public willingness to adopt Hyperloop technology?

- What is the relationship between environmental expectations and the willingness to use Hyperloop as a sustainable transport solution?

- How do environmental perceptions, general attitudes, and perceived need interact in shaping public acceptance of Hyperloop technology?

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. Research Gap and Research Questions

Using five key dimensions—(1) general openness to new transportation technologies, (2) awareness of the Hyperloop concept, (3) perceived need for innovation in the transportation sector, (4) individual willingness to use such a system, and (5) environmental expectations related to future mobility solutions—this study presents a survey-based assessment of public awareness and acceptance of Hyperloop in Poland to bridge this gap. The study aims to nuance public attitudes toward energy-efficient transportation innovations and their perceived role in achieving technological and environmental progress by capturing these interconnected elements.

These insights are crucial for policymakers, investors, and technology developers aiming to align social values and sustainability goals with the expansion of transportation infrastructure. In addition to guiding more targeted policy interventions and communication campaigns, a deeper understanding of societal readiness can support national decarbonization efforts by enhancing the credibility and long-term sustainability of energy-resilient solutions, such as Hyperloop.

This study aims to fill this gap by examining public awareness and acceptance of the Hyperloop concept in Poland, with a focus on environmental and energy perceptions. Using a survey-based methodology, the study examines the level of familiarity with the technology, perceived risks and benefits, and overall willingness to support its development. The study analyzed data from various demographic groups to determine how energy concerns, sustainability values, and technological optimism influence public attitudes toward energy. This contrasts with much of the literature, which does not differentiate attitudes based on demographic groups. The findings aim to guide information initiatives, investment plans, and policies to promote inclusive and energy-efficient transportation transformations.

3.2. Research Sample

The survey produced 1000 responses from adults in Poland. Consistent with the analytic plan, cases with missing values on key outcomes were removed listwise, leaving 974 observations for inferential analyses. The age range was from 18 to 80 years (M = 47.7, SD = 15.1). The sample was 51.6% women and 48.4% men. By age band, the percentages were 6.3% for the 18–24 age group, 17.4% for the 25–34 age group, 20.8% for the 35–44 age group, 17.8% for the 45–54 age group, 22.3% for the 55–64 age group, and 15.4% for the 65+ age group. Educational attainment was 35.7% below secondary, 37.1% secondary, and 27.2% higher. Place of residence comprised 44.3% rural/small towns (≤20 k), 22.5% mid-sized cities (20–100 k), and 33.2% large cities (>100 k). Employment status included 57.1% in regular employment (including self-employment), 7.4% in part-time/contract work, 27.6% retirees/pensioners, 3.0% unemployed, 1.8% students/pupils, with the remainder on parental/other leave. For the cohort structure, 27.7% were Baby Boomers (born 1945–1964), 29.9% were Generation X (born 1965–1981), 25.5% were Generation Y (born 1982–1994), and 16.9% were Generation Z (born 1995–2007). These distributions provide adequate heterogeneity for the planned subgroup comparisons.

3.3. Data Collection Method and Statistical Analysis

The measurement strategy employed a combination of binary and ordinal indicators. Awareness of the Hyperloop concept was assessed using a simple yes/no question (auditory). This allowed for a clear distinction between respondents who were familiar with and those who were unfamiliar with Hyperloop technology. The remaining four constructs—general attitudes toward next-generation transportation technologies, perceived need for innovation, willingness to use Hyperloop, and environmental expectations—were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (negative/strongly disagree) to 5 (positive/strongly agree). This design captured not only the direction but also the intensity of opinions. Data were collected in June 2025 using the CAWI technique. An external professional research agency distributed a standardized online questionnaire to members of a nationwide panel of adult Polish residents (aged 18 and above). A total of 1000 responses were collected, of which 974 were retained after quality checks (including consistency in completion time and detection of patterned responses). The sample was obtained from an online research panel and should be treated as a convenience sample. It is not fully representative of the Polish population. Post-stratification weights were not applied, as the study’s aim was not to generate population estimates but to conduct descriptive and comparative analyses across respondent subgroups. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as reflecting patterns within the surveyed sample rather than precise population parameters.

During data preparation, we standardized labels, created age bands and generational groups, harmonized place-of-residence and employment categories, and retained the binary awareness indicator. Likert variables were treated as ordinal (not interval). Missing data were handled by deletion.

Descriptive statistics are presented in a manner that balances statistical rigour with interpretability. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are provided for Likert scores, supplemented with simplified three-column distributions (1–2 negative, 3 neutral, 4–5 positive) to enhance readability. Proportions of awareness were calculated with 95% Wilson confidence intervals to ensure accurate coverage.

Awareness was cross-tabulated with demographic variables to examine group differences and was tested using Pearson’s χ2 for multilevel tables and Fisher’s exact test for 2 × 2 comparisons (gender). Effect sizes were presented using Cramér’s V to ensure a consistent measure of the association’s strength. For Likert scores, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis omnibus tests were used for group comparisons, which are appropriate for ordinal data and robust to non-normal or unequal variances. When significant effects were detected, post hoc Mann–Whitney tests with Holm’s correction were used, and Cliff’s delta was used to indicate both the magnitude and direction of the differences.

Associations between the four Likert constructs were further analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ), which reflects monotonic relationships without assuming linearity. Inferential statistics were performed with α = 0.05 (two-sided). However, emphasis was placed on reporting effect sizes and confidence intervals to avoid overreliance on p-values and to emphasize the significance of the results.

Effect sizes were interpreted using conventional benchmarks. For Cramér’s V, values around 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 were regarded as small, medium, and large, respectively. For Cliff’s δ, values of approximately 0.15, 0.33, and 0.47 were taken to indicate small, medium, and large effects, respectively. For Spearman’s ρ, values around 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 were interpreted as small, medium, and large associations.

Each of these four constructs was measured using a single self-report item rather than a multi-item scale, reflecting the need to maintain a concise questionnaire suitable for an online panel. While single-item indicators can capture clear, concrete attitudes, they generally provide lower reliability and are more susceptible to random measurement error than multi-item scales. All responses were self-reported and may have been influenced by social desirability or acquiescence bias, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

Respondents who indicated they were unfamiliar with Hyperloop technology were provided with a clear and concise explanation before taking the survey. In addition to the text, respondents were also shown a simple illustration of the Hyperloop tunnel, capsule, and low-pressure environment to ensure a clear understanding of the concept.

4. Results

4.1. General Attitude Towards Next-Generation Transport Technologies

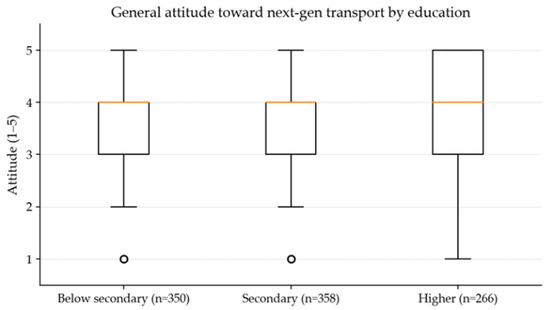

Respondents view next-generation transport technologies favourably, with a median rating of 4 (IQR 3–4, N = 974). Differences in education and place are statistically reliable yet small (Table 1). Respondents with higher education and those living in cities (especially >100 k) express more positive attitudes than below-secondary and rural/small-town respondents (Kruskal–Wallis p ≤ 0.015; ε2 ≈ 0.006–0.010; post hoc Cliff’s δ ≈ 0.10–0.14; Table 1). The sex effect is also small (men > women; p = 0.004; ε2 ≈ 0.007; δ ≈ 0.10). No differences are detected by age band, generation, or employment.

Table 1.

Kruskal–Wallis omnibus tests for Likert outcomes (significant rows).

Figure 1 shows that medians are similar across groups, but the upper quartile extends further for the Higher Education group, consistent with the findings in Table 2.

Figure 1.

General attitude toward next-generation transport by education (boxplots).

Table 2.

Post hoc contrasts (Holm < 0.05) with Cliff’s δ.

Table 1 shows that the most consistent contrasts occur for education and place across attitude, perceived need, and willingness (all with small ε2 values). Sex differences are limited to attitude and are small. Age/generation, as well as employment, are mostly null at the omnibus level, indicating broadly similar central tendencies on Likert constructs across these factors.

Table 2 shows where omnibus tests are significant, direction is stable: Higher > Below secondary and City >100 k > Rural/≤20 k for attitude, need, willingness; Men > Women for attitude. Effect sizes are small (|δ| ≈ 0.10–0.16), signalling practically modest but statistically reliable gradients.

Table 3 shows that willingness aligns strongly with general attitude (ρ ≈ 0.74) and moderately with both need and eco (ρ ≈ 0.57). The constructs are coherent (all positive associations), supporting the interpretation that general receptivity and perceived system need to underpin stated willingness.

Table 3.

Spearman correlations among Likert outcomes.

4.2. The Level of Awareness of the Existence of Hyperloop Technology

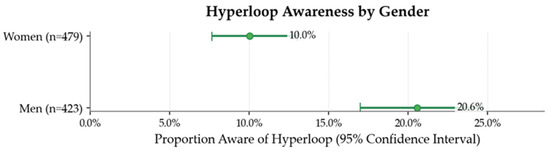

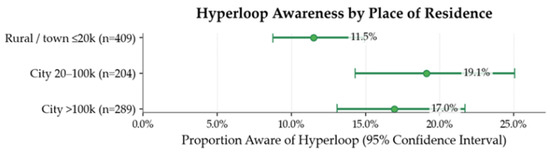

Awareness is low but informative for segmentation, at 15.0% (135/902; Wilson 95% CI 12.8–17.4%) (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This low score suggests that Hyperloop technology is still in the early stages of gaining public awareness in Poland and represents a significant barrier to mass acceptance. It is higher among men, young adults (18–24), higher-educated, city residents, and students/pupils, and lower among women, 65+, below-secondary, rural/small-town, and the unemployed (all factor tests p < 0.05; Cramér’s V small to small–moderate; Table 1). Generation, as labelled, is not significant.

Figure 2.

Awareness by sex—dot with 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Awareness by place—dot with 95% CI.

Table 4 also shows that overall awareness is low (15%), but it is unevenly distributed across the groups. The most significant relative gaps are observed by sex (Men > Women), age (18–24 years old is the highest, 65+ years old is the lowest), and employment status (Students have the highest, Unemployed Individuals have the lowest). Education and place show urban/education gradients (Higher and cities > Below secondary and rural). Cramér’s V values are minor to moderate, indicating statistically significant yet modest segmentation suitable for targeted outreach.

Table 4.

Awareness by subgroup.

4.3. Perception of the Need for Transport Innovation in Poland

The majority of respondents clearly believe in the need for innovation in transport. This is indicated by a median score of 4 on a five-point Likert scale (with an interquartile range of 3–5; N = 974), meaning that the dominant attitude is one of agreement or strong agreement with the need for new solutions. Variation again follows education and place (KW p = 0.001–0.014; ε2 ≈ 0.007–0.011), with higher and city groups more likely to score in the positive range (Table 1). Post hoc contrasts confirm Higher > Below secondary and City >100 k > Rural/≤20 k (δ ≈ 0.12–0.16; Table 2). Importantly, other demographic variables—such as gender, age/generation, and employment status—did not significantly differentiate the perceived need for innovation. This suggests that the belief in the need for transport modernization is widely held, and differences primarily stem from the level of educational capital and living conditions in urban environments.

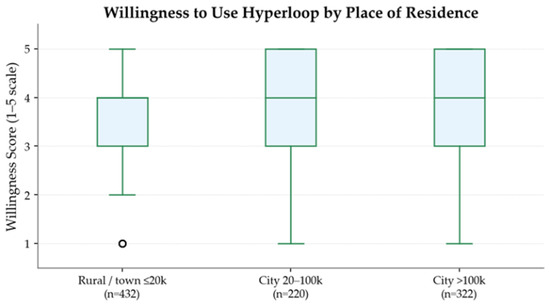

4.4. Hyperloop Readiness (Total and Subgroups)

Respondents’ declared willingness to use Hyperloop technology was clearly positive (median 4; IQR 3–5; N = 974) and is strongly aligned with general attitudes and moderately with perceived need and environmental beliefs (Spearman ρ ≈ 0.741 and ρ ≈ 0.567–0.573; all p < 0.001; Table 3). This suggests that acceptance of Hyperloop aligns with a coherent system of attitudes, in which openness to innovation and environmental sensitivity mutually reinforce the willingness to adopt new solutions.

Subgroup patterns mirror attitudes and needs: education and place show minor but reliable differences (KW p = 0.009–0.019; ε2 ≈ 0.006–0.008), with higher education and cities more willing than below-secondary and rural/small-town (δ ≈ 0.13; Table 2). These differences, although small, are statistically reliable (Figure 4). In contrast, gender, age/generation, and employment status did not demonstrate a significant impact on willingness to use this technology (Table 1), suggesting that positive attitudes toward Hyperloop are quite widespread in this regard.

Figure 4.

Willingness by place—boxplots.

4.5. Conviction of the Ecological Advantage of Hyperloop over Traditional Means of Transport

Beliefs about environmental advantage are generally positive (median 4; IQR 3–5; N = 974), with little segmentation: omnibus tests by sex, education, place, employment, and generation are not significant at α = 0.05 (Table 1). The lack of significant differences in this respect is an unexpected result, suggesting that the positive perception of the ecological attributes of Hyperloop is uniform across different demographic groups. A single adjusted age-band contrast (65+ > 25–34) was previously observed, but the omnibus age effect is marginal; we treat the overall pattern as flat. The construct correlates moderately with willingness and attitude (ρ ≈ 0.57; p < 0.001; Table 3).

4.6. Demographic Differences: Gender, Age, Education

Examining demographic differences, education, and place of residence reveals that two demographic variables consistently differentiate attitudes toward the Hyperloop. In the case of general attitudes, perceived need for innovation, and willingness to use the technology, individuals with higher education and residents of large cities were more likely to express more positive assessments than respondents with lower levels of education or those living in rural areas and small towns. It is worth emphasizing, however, that the effect sizes (ε2 in Kruskal–Wallis tests and δ in post hoc analyses) remain small, meaning that the differences are statistically significant, but their practical significance is moderate.

Analysis by gender reveals that the most significant differences occur in awareness of the Hyperloop, with men being significantly more likely than women to have heard of this technology. The Cramér V value indicates a small to moderate effect size. Regarding the remaining variables (attitudes, need, and willingness), the differences between men and women were very small and limited to general attitudes.

Age proved to be significant primarily for the awareness variable. The highest awareness of the concept was observed among young people (18–24 years old), and the lowest in the oldest group (65+). For constructs measured using Likert scales (attitudes, needs, readiness, and environmental perception), the effects of age and generational affiliation were weak or non-significant. This suggests relatively consistent attitudes across generations.

Employment status differentially affected awareness of the Hyperloop. The highest awareness of the Hyperloop was observed among school and university students, while the lowest was among unemployed individuals. Employment status had no significant effect on the remaining variables: attitudes, need, readiness, and environmental beliefs. Therefore, acceptance of new transportation technologies does not significantly depend on employment status.

5. Discussion

This study aimed (in line with the research objectives) to assess public awareness and acceptance of Hyperloop technology in Poland, with a particular focus on perceptions related to energy and the environment. The study’s findings confirm the overall positive willingness of Polish society to adopt transport innovations, which constitutes a significant contribution to the literature on acceptance in the Central and Eastern European region. The results demonstrate that acceptance of Hyperloop is not merely a reaction to technical promises but stems from a “coherent mechanism” of attitudes, in which openness to innovation, the perceived need for transport modernization, and ecological expectations reinforce one another.

This pattern of acceptance highlights that the implementation of sustainable transport innovations within the energy transition depends not only on technical feasibility but also on psychological and social factors.

Public openness to the Hyperloop system is primarily influenced by technological knowledge, the perceived need for innovation, and ecological sensitivity.

The environmental perspective—especially the reduction in emissions and the pursuit of more sustainable forms of transportation—emerges as a significant driver of social acceptance. However, the concept itself remains burdened with significant uncertainty regarding the actual costs, capacity, and operational safety.

Some groups exhibit low technological awareness or reluctance toward radical innovations, underscoring the need for targeted informational and educational activities [37]. Moreover, given the very low level of general awareness of Hyperloop (only 15% of respondents), it can be assumed that part of the declared positive attitude is not based on a thorough understanding of the technology, but rather on general innovation optimism and positive associations related to ecology and speed. Such “acceptance based on low awareness” is an important factor that should be analyzed in future models, as it may potentially distort the relationship between actual knowledge and willingness to adopt innovation.

Our findings largely align with previous studies, which have shown generally positive attitudes toward next-generation transport technologies [19,20]. At the same time, the relatively small effect of age and generation contrasts with prior work that reported stronger cohort differences, which may indicate increasing uniformity of perceptions in the Polish context.

Surprisingly, environmental beliefs show very limited variation across demographic groups [38]. These observations suggest that environmental arguments may currently resonate more broadly than in previous years, which has implications for communication strategies promoting sustainable transport.

To answer the research questions regarding public attitudes toward next-generation transport technologies and the factors shaping the acceptance of Hyperloop, the following summary conclusions based on the research findings and their discussion are presented:

- “What is the general public attitude toward next-generation transport technologies, including Hyperloop, and how does it vary based on socio-demographic factors?”

The findings indicate that the general public’s attitude toward next-generation transport technologies, including Hyperloop, is generally positive.

Although small differences were observed between social groups, these were minor in magnitude. Overall, this suggests that positive attitudes toward innovative transport technologies are broadly shared across the population, with only modest variation by socio-demographic characteristics.

In the context of existing literature, the results of the present study confirm that the general public holds a positive attitude toward next-generation transport technologies, including Hyperloop, with relatively small differences between social groups. Consistent with previous studies [19,20,39,40], demographic factors such as gender and age have a limited influence on attitudes, whereas education level and place of residence appear to play a more significant role. Our findings further extend these insights by highlighting the importance of individual knowledge about the technology, as well as perceived benefits and risks, in shaping acceptance of innovative transportation solutions. Thus, the current results not only corroborate prior research but also identify additional factors that contribute to public attitudes toward the Hyperloop.

Public attitudes toward modern transportation technologies vary across socio-demographic groups. Research indicates that younger individuals and those with higher levels of education are more likely to adopt innovative transportation solutions, as they tend to have a greater appreciation for technological advancements and their potential benefits [41].

The results indicate that the general public’s attitude toward next-generation technologies, including Hyperloop, is positive, with minor differences between social groups. Similar conclusions are drawn from the study by Abouelel et al. [20], who found that the Hyperloop was frequently chosen in the study sample. The attributes of the service itself, such as travel time, cost, and safety, were more crucial than most demographic characteristics. The authors noted that while income, a driver’s licence, and access to a car influenced transportation choices, other variables, including gender, played a lesser role in shaping these choices. Notably, the study showed that psychological factors—such as openness to new technologies and self-confidence—differentiated attitudes toward Hyperloop more strongly than standard demographic characteristics. This suggests that positive attitudes are generally prevalent, and intergroup differences are relatively limited.

A study in the Netherlands by Planing et al. [19] found similarly positive overall acceptance of the Hyperloop. However, attitudes also differed by gender and age, with men and younger individuals being more likely to accept the technology. Furthermore, prior knowledge of the Hyperloop concept was shown to increase acceptance.

A study of Kang et al. [39] conducted among 600 residents of Busan, South Korea, found that perceived risk plays a key role in shaping public support for Hyperloop development. The study also examined whether age, gender, and level of knowledge about Hyperloop trains could moderate the relationship between perceived risk and support for this mode of transportation. The results indicated that higher perceived risk significantly decreased support for Hyperloop development. Age and gender were not found to be significant moderators, while knowledge about Hyperloop strengthened the relationship between perceived risk and support and was itself a positive predictor of support. These findings have substantial implications for city policymakers and public transportation planners seeking to implement Hyperloop services in metropolitan areas.

Another study by Kang [40] indicates that the development of hyperloop infrastructure in Korea, despite massive investment, could bring significant benefits to local communities; however, it also raises questions about public acceptance of the technology. A study conducted among 592 residents of Gyeongnam Province examined how the perceived benefits of hyperloop influence perceptions, the value attributed to the technology, support for the project, and intention to use hyperloop trains. The results showed that higher perceived benefits translate into a more positive image and higher value for hyperloop among residents, which in turn increases their support for the development of this infrastructure and their willingness to use it. These findings offer valuable insights into the public’s perceptions of innovative transportation technologies, supporting decision-makers in planning and communicating hyperloop projects in urban areas.

- 2.

- “What is the current level of public awareness of Hyperloop technology, and which demographic groups are more or less aware?”

The results show that awareness of Hyperloop technology in the general population is relatively low, varying by age, gender, education, and place of residence. A similar pattern is observed in the study by Abouelela et al. [20], in which as many as 70% of respondents had heard of Hyperloop, but only 9% declared extensive knowledge about it. Furthermore, men demonstrated significantly greater familiarity with and interest in this technology than women, which is reflected in our results. However, the authors emphasize that their study sample comprised primarily young and well-educated participants, meaning that awareness levels are likely even lower in the broader population.

Previous research by Planing et al. [19] indicates that more than half of respondents (55.8%) had never heard of Hyperloop. It also found that those with prior knowledge were significantly more likely to accept the technology. The authors suggest that expanding knowledge (e.g., through visualizations or VR experiences) may foster acceptance.

At the same time, research [42] indicates that social media, particularly YouTube content, plays a significant role in shaping trust in Hyperloop and intentions to use this technology. A study conducted with 760 participants in a video experiment demonstrated that trust transfers from the accounts presented in the videos to perceptions of the Hyperloop transportation system, which in turn increases the intention to travel by this mode. Attitudes toward Hyperloop mediated the relationship between trust in video content, perceived risk, and travel intention. These results underscore the importance of awareness of technology and trust in information sources in shaping public perceptions of innovative transportation modes.

- 3.

- “How do perceptions of the need for innovation in the transport sector influence public willingness to adopt Hyperloop technology?”

The results demonstrate that the perceived need for innovation in the transport sector clearly increases the willingness to use Hyperloop. The stronger the belief that transport requires modernization, the greater the openness to adopting new solutions.

Our own research confirmed that the perceived need for innovation in the transportation sector strengthens the willingness to accept Hyperloop. According to Abouelel et al. [20], this mechanism is reflected in the degree of positive attitudes toward new technologies and willingness to use them (affinity for technology)—respondents who were more open to new solutions were more likely to declare their willingness to choose Hyperloop. The authors also showed that user self-confidence was a significant factor in early adoption of this technology. This indicates that both the subjective assessment of the need for modernization and individual psychological predispositions shape social readiness to use modern means of transportation.

Comparing with other studies in this area [19], it is essential to note that performance expectancy was identified as a significant predictor of acceptance—that is, benefits such as speed, comfort, and environmental advantages. This finding is consistent with current research, which suggests that a belief in the need for innovation is associated with high expectations regarding the performance of new technology.

- 4.

- “What is the relationship between environmental expectations and the willingness to use Hyperloop as a sustainable transport solution?”

Respondents who perceive potential environmental benefits are more likely to declare their willingness to adopt Hyperloop as a sustainable mode of transportation, as confirmed by the moderate positive correlation between these variables (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.001; see Table 4). This finding indicates that environmental awareness and perceived ecological advantages significantly contribute to public readiness to adopt low-carbon mobility solutions. Notably, these pro-environmental beliefs are widely shared and do not vary substantially across demographic groups, suggesting that environmental sensitivity represents a broadly common value in shaping attitudes toward next-generation transport technologies.

The relationship between environmental expectations and willingness to use the Hyperloop as a sustainable mode of transportation largely depends on environmental awareness and concern. Exposure to sustainable practices and an understanding of the benefits of reducing carbon dioxide emissions are crucial in this context. Tanwir and Hamzah [43] indicate that the greater an individual’s environmental knowledge, the more likely they are to use eco-friendly transportation alternatives. This means that increased awareness of the negative environmental impact of traditional transportation increases the willingness to implement innovative, energy-efficient solutions, such as the Hyperloop, that reduce carbon footprints. Furthermore, Waqas et al. [38] emphasize that environmental concern mediates the acceptance of sustainable transportation options. Research shows that individuals aware of the environmental and social benefits of sustainable transportation, as well as the problems associated with traffic and pollution, are more likely to support eco-friendly innovations. Consequently, higher environmental expectations are associated with greater willingness to use the Hyperloop as an energy-efficient and eco-friendly mode of transportation.

Our research demonstrates that positive environmental expectations associated with Hyperloop are closely linked to willingness to use this technology. Other findings [20] confirm the importance of this issue, with approximately 60% of respondents citing environmental impact as an essential factor when choosing a mode of transportation. Furthermore, in their literature review, the authors emphasized that Hyperloop is perceived as an energy-efficient, quiet, and low-emission solution. Although environmental considerations were not explicitly incorporated into choice models, the researchers suggest that communicating the potential environmental benefits can significantly increase public acceptance of this mode of transportation.

Planing et al. [19] confirm that expected environmental friendliness (sustainability) is a performance expectancy and significantly increases Hyperloop acceptance. However, the authors note that safety factors (perceived danger—e.g., fear of technology failure, lack of windows, or low-pressure environments) may simultaneously weaken the willingness to use.

- 5.

- “How do environmental perceptions, general attitudes, and perceived need interact in shaping public acceptance of Hyperloop technology?”

The study demonstrates that acceptance of Hyperloop results from the interplay of several key factors. A general positive attitude toward technology is the most critical element that directly influences readiness to adopt it, as confirmed by a strong positive correlation between attitude and willingness (ρ = 0.74, p < 0.001; see Table 4). At the same time, the perceived need for innovation in transportation (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.001) and environmental expectations (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.001) reinforce this attitude, creating a coherent mechanism that fosters acceptance. Therefore, the more respondents perceive the need for modernization and the environmental potential of Hyperloop, the stronger their positive attitudes, which then translate into openness to this technology.

Research findings indicate that Hyperloop acceptance is not driven by a single factor but rather a combination of several elements: a generally positive attitude toward the technology, a belief in the need for innovation in transportation, and expectations related to environmental benefits. Similar conclusions were reached by Abouelela et al. [20], who noted that respondents’ choices depended not only on the characteristics of the service itself, such as travel time, cost, and safety, but also on psychological attitudes—openness to new solutions or concerns about innovation. The authors also indicated that individual characteristics, such as gender and self-confidence, played a role in early adoption. All of this demonstrates that Hyperloop acceptance is shaped by a complex interplay of beliefs, experiences, and expectations, which mutually reinforce one another, increasing the willingness to use this technology.

Comparatively, previous results [19] suggest that the Hyperloop acceptance model is primarily explained by two factors: performance expectancy (benefits, including speed, comfort, and environmental aspects) and perceived danger (safety concerns). Thus, positive attitudes stemming from expected benefits are crucial; however, interactions may be limited by safety concerns. This extends our conclusion by adding the risk dimension as a counterbalancing factor.

Meanwhile, another study [44] indicates that Hyperloop promotional videos can influence travellers’ pro-environmental behaviour and their willingness to use this technology as a sustainable transportation option. The results showed that awareness of the issue, a sense of responsibility, and attitudes toward travel play a role in shaping pro-environmental intentions. The study highlights the importance of the perception of Hyperloop’s environmental value in shaping public acceptance of modern transportation.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study show that Polish society is generally favourable to next-generation energy-efficient transportation technologies, such as Hyperloop. This is indicated by positive ratings across all survey dimensions: attitudes, perceived need for innovation, willingness to use rail, and environmental expectations. Furthermore, it is noticeable that willingness to use Hyperloop strongly depends on general attitudes toward innovation and, to a lesser extent, on perceived environmental benefits and the need for changes in transportation. Therefore, greater emphasis could be placed on increasing awareness of the energy efficiency and positive environmental impact of this mode of transportation.

Poles are favourably disposed toward next-generation transport, with medians at 4 for attitude, need, willingness, and environmental expectations, and 15% already recognize Hyperloop by name. Segmentation is present but modest: education and urbanicity consistently predict more positive attitudes, stronger perceived need, and greater willingness (KW p < 0.05; ε2 small; post hoc δ ≈ 0.10–0.16). Willingness is tightly coupled with general attitude and moderately with need and eco (all ρ significant), suggesting a coherent acceptance structure.

For policy and communication, the most significant gains likely come from awareness building (especially among women, older adults, rural/small-town residents, and the unemployed) and from messages that frame Hyperloop within broader innovation needs and environmental expectations. Effects are statistically reliable yet small, advising proportionate expectations and targeted, equity-minded outreach.

No study is free from limitations. First, the sample was not designed to be nationally representative. The study used a quota-based online panel rather than a probability sample. As a result, the findings cannot be fully generalized to the entire Polish adult population. Next, the current study has at least several significant research limitations. This cross-sectional design makes it impossible to capture changes in attitudes toward the hyperloop over time. Future research should therefore replicate and extend these findings in longitudinal studies. Furthermore, the study relies on respondents’ subjective opinions, which may bias responses toward socially desirable outcomes or conceal a lack of subject knowledge. A specific limitation may also be the lack of comparison between Hyperloop and other means of transport, such as high-speed rail or air transport, which would allow for a more comprehensive assessment of its advantages. A key limitation is the omission of measures for risk perception (e.g., perceived safety, comfort, and consequences of failure) and cost expectations (e.g., ticket price, value of time, and cost relative to alternatives). These are well-known, critical determinants of technology adoption, and their absence limits the explanatory power of the current correlational models. It should be noted that this study was conducted without parallel measurements of acceptance and preference for existing transportation alternatives (i.e., high-speed rail, air travel, or intercity buses). This prevents a direct assessment of the relative advantage of Hyperloop technology in the eyes of respondents compared to currently available options. In the context of the Diffusion of Innovations Theory, relative advantage is a key factor in the adoption of new technology. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to further investigate the comparison with other modes of transportation to assess the competitive advantage of Hyperloop in the transportation market.

The authors would also like to suggest directions for future research in this area. Firstly, future studies employing probability sampling or post-stratification weighting would enable population-level inference. To deepen the research, a triangulation method is planned, combining quantitative and qualitative research approaches. This will help expand on the current study, which captured general trends and statistical differences in attitudes toward the Hyperloop system based on demographic characteristics. However, this quantitative research did not provide insight into the motivations, concerns, or uncertainties that respondents had when providing their answers, which could be further explored in a qualitative study, such as through in-depth interviews. This seems particularly important for capturing differences in Hyperloop acceptance across demographic groups. Future quantitative research will also extend the present findings by developing multivariable models to more accurately predict Hyperloop acceptance. This is essential for understanding the complex interplay of factors. Crucially, these models will integrate measures of perceived risk (safety, comfort, and system failure) and cost expectations (e.g., fare sensitivity and time-saving valuation) to assess their moderating and mediating roles alongside general attitude, perceived need, and environmental beliefs. Including these dimensions will significantly enhance the predictive and explanatory power of the acceptance model. Therefore, it is expected that the use of triangulation will enhance data consistency, as interpretations and assessments from qualitative research will further strengthen the results of the statistical analysis of quantitative data. This is also important for capturing the motivations, concerns, and uncertainties (including safety fears and cost sensitivity) that underpin the quantitative responses, especially among less-aware or more cautious demographic groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R., A.M., M.O., A.W.-H. and S.F.; methodology, R.R., A.M. and M.O.; validation, R.R. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, R.R., A.M., M.O., A.W.-H. and S.F.; resources, R.R. and A.M.; data curation, R.R. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R., A.M., M.O., A.W.-H. and S.F.; writing—review and editing, R.R., A.M., M.O., A.W.-H. and S.F.; visualization, A.M.; funding acquisition, R.R., A.M. and A.W.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the AGH University of Krakow through resources allocated for the development of the research capacity of the Faculty of Management, as part of the “Excellence Initiative—Research University” programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it involved anonymous survey data collected by a professional research company.

Informed Consent Statement

The participants were individuals included in the research company’s panel database. Their enrollment in the panel was voluntary and based on informed consent, and they knowingly and voluntarily agreed to take part in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- aus dem Moore, N.; Brehm, J.; Gruhl, H. Driving Innovation? Carbon Tax Effects in the Swedish Transport Sector. J. Public Econ. 2025, 248, 105444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksenofontova, T.; Velikopolskaya, E.; Yuan, M. Interrelation of Levels of Development of Innovation Potential and Transport Ecosystem of Regions. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 383, 03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P.H.; Degano, M.; Gerada, C. Radical Technology Innovations for High-Speed Transport; ePlanes to Replace Rail? Electr. Syst. Transp. 2023, 13, e12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevrlý, V.; Redutskiy, Y.; Poul, D.; Šomplák, R. Incorporating Rail Transport into the Waste Flow and Processing Chain for Sustainable Waste Handling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 296, 129055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janić, M. Estimation of Direct Energy Consumption and CO2 Emission by High Speed Rail, Transrapid Maglev and Hyperloop Passenger Transport Systems. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 15, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Hydrogen: Seizing Today’s Opportunities; IEA: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9e3a3493-b9a6-4b7d-b499-7ca48e357561/The_Future_of_Hydrogen.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Dong, S.; Song, Z.; Meng, Z.; Liu, Z. Biofuel–Electric Hybrid Aircraft Application—A Way to Reduce Carbon Emissions in Aviation. Aerospace 2024, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Villa, M.-G.; Flores-Vázquez, C.; Álvarez-Vera, M.; Cobos-Torres, J.-C. Toward Sustainable Urban Transport: Integrating Solar Energy into an Andean Tram Route. Energies 2025, 18, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premsagar, S.; Kenworthy, J. A critical review of Hyperloop (ultra-high speed rail) technology: Urban and transport planning, technical, environmental, economic, and human considerations. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 842245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeck, D.; Janke, F.; Gatta, F.M.; Nicolau, J.A.; Semino, G.; Hofmann, T.; Jocher, A. Case Study of an Integrated Design and Technical Concept for a Scalable Hyperloop System. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeverden, K.V.; Milakis, D.; Janić, M.; Konings, R. Analysis and Modelling of Performances of the HL (Hyperloop) Transport System. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2018, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernyuy, A. Impact of Technological Advancements on Human Existence. Int. J. Philos. 2024, 3, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Bailey, G. Hyperloop: Cutting Through the Hype; Transportation Research Laboratory: Crowthorne, UK, 2018; Report No. ACA003; Available online: https://www.trl.co.uk/uploads/trl/documents/ACA003-Hyperloop.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Agaton, C.B.; Guno, C.S.; Villanueva, R.O.; Villanueva, R.O. Diesel or Electric Jeepney? A Case Study of Transport Investment in the Philippines Using the Real Options Approach. World Electr. Veh. J. 2019, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Betancourt, R.; Galvis, B.; Mendez-Molano, D.; Rincón-Riveros, J.M.; Contreras, Y.; Montejo, T.A.; Rojas-Neisa, D.R.; Casas, O. Toward Cleaner Transport Alternatives: Reduction in Exposure to Air Pollutants in a Mass Public Transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7096–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Miao, H.; Bayram, A.; Yu, M.; Chen, X. Optimal Routing of Multimodal Mobility Systems with Ride-Sharing. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 28, 1164–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei, F.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Paz, A.; Bunker, J. Individual predictors of autonomous vehicle public acceptance and intention to use: A systematic review of the literature. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.J.; Pan, S.-Y.; Lee, I.; Kim, H.; You, Z.; Zheng, J.-M.; Chiang, P.-C. Green transportation for sustainability: Review of current barriers, strategies, and innovative technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planing, P.; Hilser, J.; Aljovic, A. Acceptance of hyperloop: Developing a model for hyperloop acceptance based on an empirical study in the Netherlands. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 38, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelela, M.; Al Haddad, C.; Islam, M.A.; Antoniou, C. User Preferences towards Hyperloop Systems: Initial Insights from Germany. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1336–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.; Kusa, R.; Rumin, R.; Suder, M.; Feliks, J. Identifying the determinants of vacuum tube high-speed train development with technology roadmapping—A study from Poland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouni, M.; Abdallah, K.B.; Ouni, F. The nexus between indicators for sustainable transportation: A systematic literature review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 95272–95295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelti, F.; Allouhi, A.; Tabet Aoul, K.A. Transition paths towards a sustainable transportation system: A literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Transportation carbon reduction technologies: A review of fundamentals, application, and performance. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 11, 1340–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzin, A.; Rabadjieva, M.; Emmert, S. Social Innovation: Driving Force of Social Change. In Final Report: Social Innovation in Mobility and Transport. Main Results. Deliverable 8.4; Technische Universität Dortmund: Dortmund, Germany, 2017; pp. 106–109. Available online: https://www.si-drive.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SI-DRIVE-D8_4-Final-Policy-Field-Report-Mobility-and-Transport.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Rail; IEA: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-rail (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- EEA. Decarbonising Road Transport—The Role of Vehicles, Fuels and Transport Demand (EEA Report No. 2/2022); European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/transport-and-environment-report-2021 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Beckert, P.; Pareschi, G.; Ehwald, J.; Sacchi, R.; Bauer, C. Fast as a plane, clean as a train? Prospective life cycle assessment of a hyperloop system. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 17, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfeldt, A. Railway Capacity Analysis: Methods for Simulation and Evaluation of Timetables, Delays and Infrastructure; Technical Report; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Railway-capacity-analysis%3A-methods-for-simulation-Lindfeldt/133f870ec8eff2dc39ec210a8d5728e77aac58cf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Tuchschmid, M.; Knörr, W.; Schacht, A.; Mottschall, M.; Schmied, M. Carbon Footprint and Environmental Impact of Railway Infrastructure; Technical Report; International Union of Railways: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://www.uic.org/IMG/pdf/uic_rail_infrastructure_111104.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Effect of Hyperloop Technologies on the Electric Grid and Transportation Energy; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2021/02/f82/Effect%20of%20Hyperloop%20Technologies%20on%20the%20Electric%20Grid%20and%20Transportation%20Energy%20-%20Jan%202021.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Bongaerts, R.; Kwiatkowski, M.; König, T. Disruption Technology in Mobility: Customer Acceptance and Examples. In Phantom ex Machina; Khare, A., Stewart, B., Schatz, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, R.; Skaria, S.; Kurian, T.G.; Kuruvilla, R. Study on Acceptability of Hyperloop in Kerala. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2021, 9, 120–124. Available online: https://www.ijert.org/research/study-on-acceptability-of-hyperloop-in-kerala-IJERTCONV9IS09029.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Trzoński, K.; Ostenda, A.; Mikulski, J. Hyperloop One, aspekty techniczne i społeczne [Hyperloop One: Technical and Social Aspects]. Transp. Probl. 2017, 12, 194–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fajczak-Kowalska, A.; Kowalska, M. Innovation in transport as the answer to contemporary communication problems. J. Mod. Sci. 2019, 43, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, I.A. Hyperloop transport technology assessment and system analysis. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2020, 43, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Dong, Q.; Ahmad, N.; Zhu, Y.; Nadeem, M. Understanding acceptability towards sustainable transportation behavior: A case study of China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.E.; Kim, H.; Chung, N. Do urban residents support Hyperloop development? Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 39, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.E.; Chung, N.; Lee, K.; Erul, E.; Han, S. Residents’ support for Hyperloop development and their travel intention: A case study of Gyeongnam Province, South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, K. Impact of Accidents Involving Autonomous Vehicles on the Perceived Benefits and Concerns. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering (ICCSTE 2023), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 4–6 June 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]