Abstract

Despite growing emphasis on sustainability across engineering disciplines, empirical evidence on how structured interventions shape students’ sustainability knowledge and understanding remains limited. This study introduces and evaluates a set of purposefully designed sustainability modules integrated into an architectural engineering design studio. It addresses a persistent gap in student knowledge due to insufficient and non-coherent integration of sustainability topics. Noting the increased necessity to tackle complex sustainability challenges by systems thinking and applied design, the modules were designed to support learning across five progressive steps: foundational concepts, specialization and peer teaching, hands-on assessment, project-based integration, and reflective synthesis and future implementation. Using a mixed-methods approach, the modules were tested through pre- and post-intervention assessment, supported by statistical analysis (t = 41.92, p < 0.001) and qualitative feedback from students and instructors. The findings suggest significant improvements in students’ sustainability knowledge and in-depth engagement when incorporating active and collaborative learning strategies. Similarly, project-based learning and peer learning exercises were seen as most effective in fostering comprehension and applied understanding. The iterative approach of refining module’s content and delivery based on students’ feedback—such as incorporating reflective prompts in later sessions—improved conceptual clarity and strengthened student learning needs and relevance to the study topic. By addressing the gaps in knowledge and curriculum integration, this exploratory study offers a transformative framework to integrate sustainability into engineering curricula and highlights the importance of pedagogical strategies in promoting sustainability competencies within engineering.

1. Introduction

With a rapid increase in global sustainability concerns, the associated challenges are also increasing exponentially, prompting higher education institutions to put increasing emphasis on equipping students—particularly those in engineering disciplines—to meet these demands. This shift necessitates rethinking academic programs and their curriculum to provide students with the skills, knowledge, and values needed to address the multifaceted environmental, economic, and societal issues. At the intersection of building systems, structural design, mechanical systems, construction, and environmental performance, Architectural Engineering (AE) offers a unique opportunity to blend sustainability principles into real-world applications.

Architectural Engineering operates at the junction of multiple scientific and professional domains, representing an inherently interdisciplinary field connecting the physical sciences of building performance with the social dimension of design practice and learning. The present work approaches sustainability education not only as a traditional pedagogical challenge but also to explore how cross-interdisciplinary collaboration, cognitive engagement, and systems thinking can improve students’ understanding of sustainable design. Incorporating sustainability within the engineering field that has an interdisciplinary nature establishes a broader scientific foundation from which the subsequent research questions emerge. For example, Moradi-Aliabadi & Huang [] explored the importance of incorporating sustainability into engineering curricula to train future engineers in creating innovative solutions. Despite sustainability’s broad recognition and potential importance as a viable learning outcome within engineering education [], existing programs remain inadequate in embedding sustainability as a core component [,]. This disconnect between sustainability’s recognized importance and its fragmented representation in teaching practices has led to persistent knowledge gaps among graduates.

Recent global investigations demonstrate that sustainability education in design and engineering programs is receiving increased attention across diverse educational contexts. For example, Schiano-Phan [] emphasizes the need for design studios to routinely incorporate environmental checks, Ahmad [] reports on student perceptions of sustainability practices in architecture programs, Hendawy [] presents SDG integration across architecture curricula, and Alhassani [] provides a global review of sustainability frameworks in engineering education. These international efforts highlight a growing consensus that sustainability must be embedded as a core pedagogical dimension rather than treated as an elective add-on. Collectively, they indicate that sustainability education has evolved from isolated coursework into an essential pedagogical framework across institutions, reflecting a shared global movement toward reforming design education.

Several studies [,] highlight that while students are exposed to sustainability, there remains a disconnect in fostering meaningful engagement among students that promotes critical thinking and informed decision-making. Curriculum can shape how students learn and approach engineering problems; however, in many cases, sustainability is introduced through isolated lectures detached from the curriculum’s core design []. A comprehensive framework and thorough approach are instrumental in reforming how sustainability is integrated into the engineering curriculum. Design studios are one of the solutions that can be treated as a central hub, providing a powerful space for sustainability integration. It emphasizes iteration, problem-based learning, and synthesis of technical and creative processes. Yet many traditional studios and course formats suppress sustainability teachings and often relegate sustainability to a secondary consideration [], presenting them as a missed opportunity in engineering education.

To bridge this gap, a shift towards sustainability-focused approaches emphasizing active learning and interdisciplinary collaboration is required. This will enable students to gain knowledge through engagement and peer learning while transitioning through real-world challenges [,]. These approaches are well-positioned with regard to sustainability education, fostering not only technical knowledge but also adhering to the interdependencies and their long-term impacts. In addition, many accredited institutes and professional organizations, such as the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) and the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), promote sustainability as a core competency for future engineers. Also, the “Triple Bottom Line" framework that emphasizes the balance between environmental, social, and economic factors aligns with their definitions. It reinforces the value of preparing students with a holistic and responsible mindset for the future [].

While there is growing institutional support, there is still limited evidence concerning sustainability-integrated interventions within the context of AE design studio []. This study evaluates the preliminary implications of embedding sustainability-integrated modules in AE design studios by bridging the gap in existing curricula and improving understanding of sustainability concepts and design decision-making. Specifically, this work explores the viability of interventions, student engagement, feedback, and design decision-making improvement, in essence, with the current sustainability practices. The interventions were implemented as sustainability modules embedded within existing studio courses, capturing a closer observation of students’ interactions, reflections, and learning outcomes. As a broader research initiative focusing on transforming engineering education through sustainability integration, this exploratory study represents a foundational step toward identifying effective pedagogical strategies for design studios. The findings will inform the development of a more comprehensive and thorough curriculum transformation, contributing to the ongoing efforts of sustainability education within built environment disciplines.

Research Questions

This study explores the preliminary impact and feasibility of integrating sustainability modules within the AE design studio courses. Based on the interdisciplinary foundation outlined earlier, this work considers how sustainability education within AE fosters an integrative learning experience. The primary aim is to understand how interdisciplinarity and experiential learning methods strengthen students’ sustainability knowledge and their ability to apply these principles in design contexts. The research is mainly guided by the following questions:

- To what extent does the integration of sustainability modules influence student understanding of sustainability concepts and improve their skills?

- Does the incorporation of sustainability-focused interventions improve students’ academic performance?

These research questions arise from the broader scientific perspective that recognizes sustainability education within engineering as not just extending beyond technical knowledge, but is inherently shaped by social, cognitive, and collaborative aspects. By linking the research questions to these interdisciplinary and scientific considerations, this work seeks to capture both measurable educational outcomes and qualitative aspects of learning, reflection, and teamwork that foster sustainability-focused design education.

2. Methodology

2.1. Overview of Research Approach

This research adopted a multifaceted methodological approach to assess and improve students’ knowledge. It aimed to develop and implement innovative interventions that can help improve sustainability education. The following methodology reflects a carefully structured process to enhance future engineers’ sustainability competencies. It progresses through the design and adaptation of knowledge assessment instruments to gauge and benchmark students’ baseline sustainability knowledge and improve students’ prior knowledge.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of AE and sustainability education, the research methodology combines empirical rigor with pedagogical reflection. The use of a mixed-methods approach was specifically chosen to capture both quantitative learning outcomes and qualitative dimensions such as collaboration, reflection, and systems thinking. By doing so, the research procedure aligns well with the study’s scientific premise: that sustainability learning is shaped by interactions between cognitive, social, and technical factors. This premise justifies the need for a rigorous, interdisciplinary methodological design.

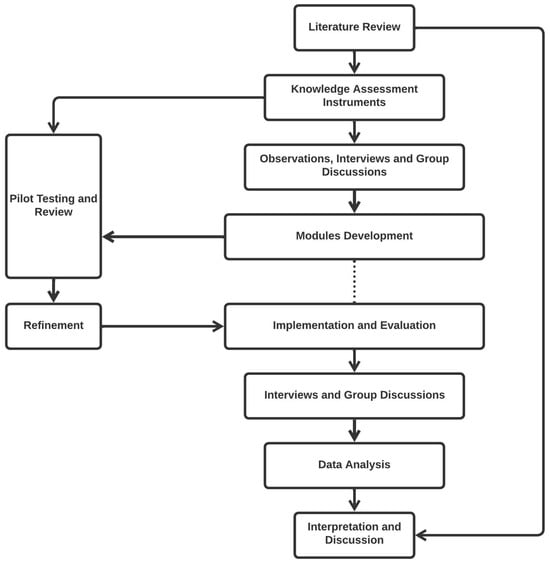

By describing each step of the research process, from the initial assessment of existing knowledge to the interpretation and discussion for future inquiry, the approach reflects the research strategies and outlines a detailed roadmap for the study. Figure 1 shows the complete flowchart of the design methodology, providing context and highlighting the significance of each step, offering a structured overview of how the research was conducted. It reflects an iterative and integrated design-based approach: identifying gaps in student sustainability knowledge, designing and refining targeted interventions, implementing a pilot study, and conducting structured assessment and evaluation. The feedback from each stage informs the following stage, allowing the interventions to be adapted with time. The following subsections describe this process in detail, from module development and piloting to participant recruitment, data collection, and analytical strategy.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Research Methodology.

This study adopts a mixed-method approach for data collection and analysis. The quantitative data comprises surveys and knowledge assessment tests, emphasizing objective measurements and analyses of data collected using statistical methods to highlight characteristics and trends in the data. In contrast, the qualitative data, consisting of observations, reflections, open-ended questions, group discussions, and interviews, guides the researcher in understanding where a student’s knowledge is lacking and what areas need improvement. These qualitative methods are adept at uncovering underlying reasons, opinions, and motivations, offering a deeper understanding of the research subject [].

2.2. Intervention Design: Sustainability Modules—Development and Implementation

The design of practical educational modules for AE design studio students requires a blend of theoretical knowledge and practical or hands-on application, particularly regarding sustainability. The modules ensure that the study goals and objectives were met, providing the preliminary feedback collected in informing the design process, consisting of interactive workshops, collaborative group sessions, and crits with regular checkpoints for feedback and adjustments. The module development process involves a series of systematic steps that ensure the new modules are tailored to meet the current study’s specific educational objectives.

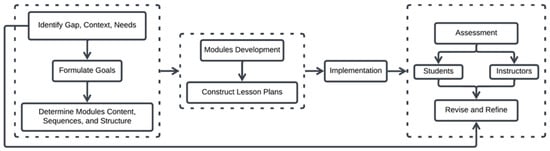

Figure 2 presents a structured approach for the modules’ design, development, and implementation. The first step is the identification of gaps, needs, goal formulation, and module structure, followed by the development of modules and lesson planning. These modules are then implemented and assessed later by the instructors and the students. Lastly, the modules were revised and refined based on the feedback collected to go through an iterative process that compares with the initial gaps identified, ensuring they are aligned with learning goals and adaptable to feedback.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Development Approach for Sustainability Modules.

These modules were evaluated through assessment criteria of different surveys and tests to determine the modules’ effectiveness. This systematic approach ensures the enhancement of student sustainability knowledge while preparing them to apply these principles in practical design projects. The process within the context of the modules’ development and implementation phase is described in the following sections.

2.2.1. Review and Development

A review of existing educational modules or frameworks, instruments, and research studies was conducted, and successful models and approaches were identified. The developed modules, dissected into five sessions, aim to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes, ensuring their alignment with the evolving needs of AE students and the sustainability objectives. These sessions incorporate conceptual foundation and exploration, specialization and peer teaching, practical applications, project-based sustainability analysis, reflections, and future applications. They also aim to gradually build students’ awareness of sustainability concepts using teaching strategies that involve active and reflective learning. Additionally, the interdisciplinary learning approaches ensure the modules encourage active participation from students in interactive workshops, incorporate hands-on projects, and develop forums for discussion and collaboration, promoting interdisciplinary learning and collaboration between students from different subdisciplines within AE.

2.2.2. Pilot Study

The researcher explored the feasibility of conducting a pilot study to improve an educational design studio course in the AE department. It broadens the research goals to integrate sustainability in the design studio and identifies sustainability outcomes and elements to support future learning. This study aimed to determine what improvements are needed to understand the course dynamics. It was designed for pedagogical purposes, with the primary objective of developing modules, conducting structured and unstructured interviews, and analyzing the data. Before proceeding, the researcher carefully considered the purpose of the study, how to collect data for identifying gaps or lack of student knowledge, understanding design studio dynamics, and how to comply with the other aspects, such as students’ learning and gathering preliminary data analysis results, which form the basis of the study.

In addition, the researcher adhered to the guidelines of the intent and use of data, ensuring confidentiality and minimizing potential participants’ risks per the approved Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol. Feedback from students and instructors addressed content relevance, engagement level, perceived impact on sustainability understanding, and logistical feasibility. Before adaptation began, the researcher met with potential instructors to present the existing instruments and research findings. The goal was to gather initial thoughts on relevance, applicability, and possible challenges in the AE studio context and make necessary adjustments based on feedback, adjusting the modules’ structure to better align with student learning patterns.

2.2.3. Assessment and Improvement

The research study aims to enhance sustainability education in a comprehensive and multi-phased endeavor. It aims to assess and improve sustainability education through three phases of inquiry. The initial phase evaluates students’ prior knowledge through tests and surveys about their perceptions and understanding of sustainability and interviews with faculty to analyze how sustainability concepts are currently integrated. The goal is to understand the students’ baseline knowledge from which improvements can be made. The intermediate phase builds upon the previous phase’s findings, where the initial assessments’ insights are utilized to create a comprehensive guide or framework aimed at helping and teaching students to learn and apply sustainability concepts.

The final phase evaluates the effectiveness of integrating the newly developed sustainability modules or guides. This assessment focuses on understanding how these changes in the curriculum and teaching methods impact student learning and knowledge acquisition. The key aspects of this assessment include measuring improvements in students’ sustainability knowledge, their ability to apply sustainability principles in design projects, and changes in attitudes or perceptions towards sustainable design. This phase involves pre- and post-intervention studies, student feedback, project evaluations, and a comparison with groups that did not receive the new sustainability-focused education.

The goal is to gauge the effectiveness of new educational interventions and identify areas for further improvement. Sustainability in AE should integrate environmental, social, and economic considerations into the design process, where sustainability is not just an add-on but an integral part of the design process. The study systematically assesses the students’ prior knowledge, implements targeted educational modules and methods, and evaluates the outcomes, aiming to improve student knowledge and foster a generation of professionals well-equipped to contribute to sustainable development in their field.

2.2.4. Implementation and Evaluation

The fully developed and refined modules were implemented as part of the AE design studio. A process was adopted to evaluate the modules’ effectiveness, including regular updates based on student feedback. This approach is in parallel with the existing frameworks within sustainability and engineering education, highlighting that focused interventions integrated within design courses have shown considerable improvement in students’ conceptual understanding and interpretations []. Similarly, many works have indicated that the embedding of sustainability and its core principles through iterative, feedback-based studios promotes deeper and more enriched learning outcomes and collaboration skills [,,]. Incorporating these pedagogies promotes the validity of the designed modules and situates them within the growing field of sustainability-education research.

This development process ensures that the designed modules are based not only on proven effective practices but are also customized to meet the specific needs and objectives of the AE program. By doing so, it not only leverages existing knowledge but also fosters innovation and continuous improvement in sustainability education. Building on this, the modules (sessions) outlined below were designed to guide students through a progressive learning journey, from foundational understanding to applying sustainability principles in their design projects. In this study, Alhassani developed the modules, and the details are available in [].

Session 1: Conceptual Foundation and Exploration The first session was designed to lay the groundwork for understanding sustainability within an AE context. By starting with a broad conceptual exploration, students could define sustainability in their own terms, which was essential for building a personal connection to the subject matter. Including minute papers and concept maps was strategic; it encouraged immediate engagement and allowed students to visualize the interconnectedness of various aspects of sustainability.

Session 2: Specialization and Peer Teaching Building upon the foundational knowledge from the first session, the second session focused on specialized themes within sustainability. By assigning students to become ‘experts’ in a particular area, the session leveraged peer-to-peer learning, a powerful pedagogical tool that reinforces learning through teaching. This session aimed to deepen students’ understanding by encouraging them to synthesize and present information to their peers, fostering a collaborative learning environment.

Session 3: Practical Application The third session transitioned from theoretical understanding to practical application, a critical step in AE education. The group work in this session reflected the collaborative nature of the AE field, allowing students to practice sustainability assessments in a controlled academic setting and preparing them for similar tasks they would face as professionals.

Session 4: Project-based Sustainability Analysis This session was the most hands-on, requiring students to integrate sustainability principles into their ongoing design projects. It was crucial for bridging the gap between classroom learning and practical application and provided students with frameworks that solidified the modules’ hypothesis that experiential learning is essential for effective education.

Session 5: Reflection and Future Application This session served as a capstone for the modules, allowing students to reflect on their learning journey and envision how they would apply sustainability principles in their future careers. This session was critical for reinforcing the modules’ learning outcomes and ensuring that students left with a comprehensive understanding of sustainability and were committed to incorporating these principles into their work as architects and engineers.

Each session was designed with specific goals and educational strategies to build competency and foster a sustainable mindset among students. The progressive structure of the modules was intentional; each session built upon the previous one, gradually increasing in complexity and engagement with the material. This approach was based on the pedagogical principle that active, applied, and reflective learning is most effective. The chosen format for the sessions reflects a balance between individual work, group collaboration, and class discussion, imitating the variety of interactions professionals will experience. The sessions encourage knowledge acquisition, critical thinking, creativity, ethical consideration, and innovation—skills paramount for future leaders in sustainable architectural engineering.

2.3. Study Context and Data Collection

To gauge knowledge retention and understanding of pre- and post-surveys and tests, bi-weekly or monthly surveys were conducted during the semester to track the evolution of sustainability understanding. These surveys were complemented by qualitative interviews and focus groups, offering deeper insights into participants’ experiences and perceptions [,]. Quantitative analyses used parametric and non-parametric techniques such as the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test [] and Mann-Whitney U test [] to compare pre- and post-survey scores for knowledge retention assessment, and a longitudinal analysis approach was used to understand the progression of sustainability understanding over time. Qualitative data undergo thematic analyses to highlight contextual factors influencing knowledge retention and understanding evolution []. Using this mixed-methods approach [] and analyzing the data through tools such as SPSS and NVivo, the researcher could effectively measure the impact of different team-based learning environments on students’ sustainability knowledge and perceptions. This approach offers a deeper understanding of the educational process and its outcomes.

2.3.1. Participants

The target population includes students enrolled in the specified courses at the University Park Campus of Penn State, particularly those from the Architectural Engineering Department and the College of Arts and Architecture. This study examines sustainability education within the AE curriculum at Penn State, and efforts were made to improve student sustainability learning in two specific courses: (1) ARCH 441- Architecture Design Analysis, and (2) Mission-Driven Integrated Design Studio (MDID). The design studio (ARCH 441) is intended to be completed during the 4th year, although some students take the course later in their programs since it is not a prerequisite course and is attended solely by AE students. Also, the students should take the MDID design studio during their 4th or 5th year. It is a collaborative studio course that utilizes integrative project design and delivery to address a mission-driven real-case project working in teams of interdisciplinary areas, bringing together students from different disciplines—Architecture (ARCH 491), Landscape Architecture (LARCH 414), and Architectural Engineering (AE 497/498). Each team includes one architecture student, one landscape architecture student, and four or more architectural engineering students from the same class or group.

2.3.2. Recruitment Strategy

Recruitment was facilitated through faculty members teaching MDID studio and ARCH 441 courses, whose support and endorsement helped encourage student participation. At the beginning of the semester, brief presentations were given to the students, providing an overview of the project, its objectives, research goals, and the significance of students’ involvement. Following this, detailed communication that outlines the research goals, time commitment, and incentives offered was carried out, ensuring transparency and clarity. Consent forms were also given to participants to guarantee they understood the study’s purpose and their right to withdraw and voluntarily participate. The research outlines data collection methods and study protocols that received approval from the University’s IRB, highlighting the procedures and recruitment strategy involved for human subjects under the Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) for the STUDY00023850.

2.3.3. Data Collection Methods

The data collection involves a multi-layered approach to improve the extensive research design, focusing on assessing students’ knowledge and understanding of sustainability that evolves by implementing interventions. These interventions are implemented bi-weekly and/or monthly in addition to the pre- and post-surveys and tests, serving as intermediate checkpoints to gather students’ insight over time []. Additionally, the self-reflection exercises helped students to introspect on their thought processes and how their knowledge acquisition and retention can be improved. By incorporating different data collection techniques, the study informs students’ comprehension of sustainability, which can be used to improve different pedagogical strategies in engineering education.

2.4. Data Analysis Methods

Following data collection, data analysis is an important next step in evaluating and assessing the effectiveness of sustainability modules on students’ understanding and knowledge. The combination of these methods allows the study to leverage the strength of both quantitative rigor and qualitative depth to address the research objective effectively and to provide a more comprehensive and holistic understanding []. Overall, this methodological framework can serve as a transferable model for researchers and educators seeking to embed sustainability within other engineering and design programs. By uniting quantitative measurement with qualitative insight and iterative feedback, the approach ensures both scientific validity and practical adaptability, making it suitable for diverse interdisciplinary educational contexts. It allows and facilitates hypothesis testing and explores relationships between dependent and independent variables. This mixed-methods approach ensures a comprehensive and deeper understanding of participants’ insights, assisting in developing effective teaching strategies for sustainability.

2.4.1. Quantitative Data Analyses

This study used SPSS software to conduct quantitative data analyses for hypothesis testing and statistical tests, such as paired t-tests. It provides sophisticated analysis models to curate the data and manage large datasets, allowing efficient organization, transformation, and data cleaning. The descriptive statistics provide an overview of the data, helping to identify patterns, outliers, or potential areas of interest, calculating mean, median, and standard deviation, and providing dispersion and central tendency about the data distribution []. In addition, cross-tabulation analysis is valuable for observing relations and patterns between different variables. Also, it offers advanced analytical models and techniques for complex and larger datasets. This work focuses on using such a method to explore relationships between variables and similar data points in a group and provide a deeper understanding of sustainability knowledge.

This research used paired t-tests to evaluate the effect of the modules on participants’ knowledge levels. The test assessed whether there was any statistically significant change in the knowledge level before and after the interventions, such as pre- and post-assessment []. Using this approach, the shift in the participant’s knowledge level was examined over time, giving a more thorough picture of the intervention’s impact over time. In addition, the impact of team-based learning interventions on students’ knowledge was evaluated by inferential tests to deduce the effectiveness of the educational modules. By incorporating the statistical tools for advanced analyses and hypothesis testing, this approach is instrumental in understanding how different educational modules influence sustainability knowledge acquisition and the reforms that need to be implemented among teaching strategies to enhance student sustainability knowledge.

2.4.2. Qualitative Data Analyses

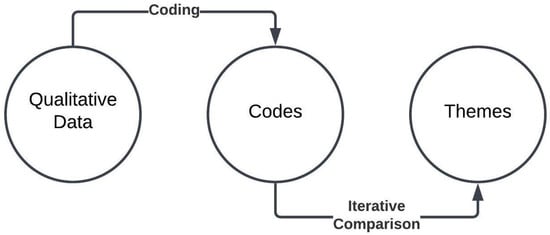

To extract significant themes and meaningful information, data must be analyzed qualitatively following a systematic approach. The methodology for analyzing the qualitative data was performed using the ‘thematic analysis’ approach, as shown in Figure 3. The process of thematic analysis consists of a systematic framework of coding and iterative comparison for identifying, organizing, and interpreting patterns and trends within the data. This work adopted the procedure of Creswell [] to organize, transcribe, and analyze the data to identify patterns and themes. The transcriptions were precisely kept, preserving the meaning of participants’ responses, and were given a unique identifier to make them anonymous while maintaining data integrity and organization. The responses were analyzed ‘sentence-by-sentence’ during the initial coding round of data that represents the themes, moods, and particular keywords [] into distinct codes. Later, these codes were improved and organized into more hierarchical groups depending on similarities and connections, helping to develop more overarching themes and patterns that emerged from thematic analysis.

Figure 3.

A Thematic Analysis Approach for the Qualitative Data.

The study objectives and participant viewpoints were aligned with the themes that were improved and established using NVivo software. This analysis seeks to produce deep, complex insights that comprehend the study topic thoroughly. The integration and collection of multiple perspectives ensured that the analysis was grounded in the participants’ actual experiences and the researcher’s observations. This systematic methodology allowed for a deeper insight into the study’s impact on participants’ understanding of sustainability while identifying improvement areas. By rigorously coding and analyzing the data, the qualitative findings contributed to a rich, detailed understanding of the modules’ effectiveness, identifying opportunities for improving the format and content within the modules.

3. Results

This section presents the findings of the study derived from both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The quantitative analysis measures the impact of interventions on students’ knowledge and comprehension, while the qualitative analysis captures students’ reflections, experiences, and their perception of understanding. Together, these findings provide a holistic and detailed understanding of how integrating sustainability modules impacts the learning capabilities of students within architecture or engineering design studios.

3.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

The data gathered, including the descriptive statistics and statistical analyses, provides an initial understanding of the effectiveness of the exploratory study conducted. It delved into the demographics and sought to understand the diverse characteristics of the participants, including age, gender, origin, and years of study. Also, parametric tests such as paired t-tests were conducted to infer statistical significance for hypothesis testing.

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

The gender statistics showed the distribution of male and female to be 60% and 40%, respectively, which was further composed into two groups, i.e., control and experimental, depending on the interventions provided to them. The age analysis reveals that the most frequent (62%) participants are 21 years old, while less than 38% are of other ages. The descriptive analysis reveals that the average age of participants in this study was 21.37 years, with a standard deviation of 0.905. Following this, the origin distribution within the study population reveals that ∼ of participants were from the United States, with minor distributions from China, India, and Nicaragua. Lastly, the year of study indicates that the majority (∼) of participants were in their 4th year, with notably less from the 3rd and 5th years, collectively accounting for 22%. The descriptive analysis reveals that participants’ average year of study is 3.95 years, with a standard deviation of 0.468. Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic data among each class.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants.

The majority (60%) of participants had not previously taken courses related to sustainability design. In the control group, the distribution between those who have taken sustainability courses and those who have not is approximately equal (i.e., 52.3% vs. 47.7%). Conversely, the experimental group predominantly consists of participants who have not previously taken sustainability design courses (79.3%). This comparison highlights variations in the level of prior sustainability education among students across control and experimental groups, suggesting that while a significant proportion of both groups have prior exposure to sustainability design courses, the experimental group stands out for its higher percentage of participants lacking such previous education. This difference may influence their perceptions or responses to the study’s interventions or outcomes.

To address this, different learning methods were explored to enhance students’ understanding of sustainability, and the results are shown in Table 2, which was later measured through targeted assessments. There was a significant consensus among participants, with acknowledging “Project-Based Learning” as the most influential method for understanding sustainability. This method involves hands-on engagement with projects, providing immersive learning experiences. Close behind, “hands-on workshops” emerge as the second most influential methods, recognized by of respondents for their significance in fostering sustainability understanding.

Table 2.

Preferred Learning Approaches Among Students.

3.1.2. Statistical Analysis

Following the descriptive overview, inferential analysis was conducted to explore the statistical significance of observed differences between the control and experimental groups. While the descriptive statistics provided a general overview of the participants and their responses, inferential analysis enabled a deeper understanding of whether the interventions significantly impacted students’ sustainability knowledge, attitudes, or engagement.

Data Normality: As normality is a prerequisite before conducting any statistical tests (parametric or non-parametric), it is important to test whether the data is normally distributed or non-normal. Depending on the data normalcy, the choice of parametric tests, such as t-test, ANOVA, etc., or non-parametric tests, such as Wilcoxon Signed-Rank or Mann-Whitney U-test, etc., must be performed. Kolmogorov-Smirnov [], a well-known data normalcy test, was used to test and validate whether the data was distributed normally. Given this study’s sample size, the results show that the data was normal, as indicated in Table 3, showing the p-value to be larger than the significant threshold ( = 0.05) for all three hypotheses (see Table 4 for reference).

Table 3.

Summary of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for data normality.

Table 4.

Research Questions and Associated Null Hypotheses.

Parametric Analysis: The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test validated the normality assumption; therefore, parametric statistical analyses such as paired t-tests were deemed appropriate for hypothesis testing. Table 4 indicates the research questions and their corresponding hypotheses formulated for testing and validating this study.

RQ1 discusses the relationships and effects of sustainability modules and educational approaches and whether students’ skills and understanding improve, allowing insights into the effectiveness of such approaches. To address this research question, and were analyzed through paired t-test analysis, and the results are reported in Table 5. For , it is evident from the results that, for both pre-and post-tests, the p-value is below the significant threshold, i.e., ; therefore, the null hypothesis can be rejected. Similarly, the test statistics reported a higher t-score for the post-test, i.e., 41.92, compared to the pre-test, i.e., 26.48. Similarly, for , the statistical results indicated a significant difference as the pre-test results reported a p-value of 0.11, higher than the significant threshold, while the post-test results indicated the p-value to be falling below the significant threshold. Therefore, the null hypothesis is retained for the pre-test, while the post-test results rejected the null hypothesis, proving that there is a statistically significant difference between control and experimental groups following sustainability interventions. This proved that sustainability interventions successfully taught students the necessary skills and confidence needed for understanding sustainability concepts.

Table 5.

Summary of the t-tests performed between pre-and post-test.

RQ2 discusses the effect of sustainability interventions on students’ academic performance between control and experimental groups. To address this research question, was analyzed through paired t-test analysis, and the results are reported in Table 6. For , it is evident from the results that, for both project-1 and project-2, the p-value is below the significant threshold, i.e., ; therefore, the null hypothesis can be rejected. Interestingly, the p-value for project-1 is 0.008 while project-2 yields a p-value, highlighting students’ performance that increased over time as project two was carried out in the second half of the semester. Furthermore, the projects’ scores for the control group were significantly lower (M = 15.8 and 30, respectively) than those for the experimental group (M = 17.50 and 36.17, respectively). This also explained the effect of sustainability interventions and teachings on students, who gained deeper knowledge, resulting in better academic performances between the control and experimental groups.

Table 6.

Summary of the t-tests performed between pre-and post-test.

3.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

The qualitative analysis focuses on and analyzes participants’ experiences, feedback, observations, and reflections to explore the dynamics of sustainability education. Through qualitative analysis, actionable insights can be identified [] to enhance the modules’ contribution to sustainability education. To identify themes among individual participants’ responses through interviews and focus group discussions, the combing and reduction procedures were performed during the interview and review process []. The methodology for analyzing the qualitative data was performed using the ‘thematic analysis’ approach, as shown in Figure 3. The process of thematic analysis consists of a systematic framework of coding and iterative comparison for identifying, organizing, and interpreting patterns and trends within the data. Table 7 presents the qualitative findings for the research questions and their associated themes, sub-themes, and key findings.

Table 7.

Thematic Mapping of Research Questions to Emergent Themes.

Thematic Analysis

RQ1 explores the impact of sustainability-integrated modules and their influence on students’ understanding and skills improvement. The data collected from the students’ observations revealed that most participants stated, “Modules play a critical role in enhancing decision-making skills.” They are essential for preserving concentration on the major objectives and guaranteeing that the project stays on course. P13 mentioned that “these modules help redirect towards core concepts outlined in the beginning, helping to stay focused.” Similarly, most participants noticed their learning journey was improved, and one of the participants stated, “going through the sustainability modules deepened the roots of my understanding of sustainability.” Student learning was further enriched with interdisciplinary collaboration, introducing diverse ideas and perspectives, fostering holistic thinking, and addressing multidisciplinary viewpoints as multiple participants highlighted that “Collaboration allows for different perspectives and viewpoints” (P2), and “these can enhance sustainability because more people with different disciplines is a great way to hear new and different ideas” (P20), respectively.

RQ2 discusses students’ performance and the influence of interventions on their academic conduct. In general, students highlighted a variety of indicators that helped them improve their academic performance, such as teamwork and collaboration. P16 mentioned that “teams were able to find more intelligent implementation techniques and reconcile divergent points of view.” Collaborative sessions promote inclusive participation, idea-sharing, and peer learning for efficient problem-solving and decision-making. Additionally, one of the participants (P15) highlighted that “those approaches allow us to consider everything before moving forward.” These cooperative methods guarantee that projects gain from various perspectives, resulting in more thorough solutions. The participants further suggested the need for ongoing reinforcement of those modules and approaches to ensure deeper alignment and improved academic performance to help students collaborate, share ideas, and improve group comprehension and communication. These reinforcements may support effective group decision-making, enable insightful discussion topics for further research, and help structure design thinking within a collaborative workspace.

The synthesis of quantitative and qualitative findings provides a detailed understanding and perspective of the sustainability modules in engineering education. The statistically significant improvements in students’ sustainability knowledge and performance (as evidenced in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) were further supported by the qualitative reflections highlighting the impact of experiential learning activities. For instance, the observed increase in post-test scores aligns with student observations describing how hands-on workshops and collaborative design tasks enhanced their ability to connect theoretical sustainability concepts with real-world design decisions. Similarly, the preference for project-based learning, as reflected in survey results (Table 2), corresponds with focus group discussions where participants emphasized teamwork, peer learning, and the relevance of engaging directly with design problems. This alignment between quantitative gains and qualitative experiences underscores that active, practice-based learning approaches not only improve measurable academic outcomes but also strengthen reflective understanding and motivation toward sustainable design practice.

4. Conclusions

This exploratory study provides insights into evaluating the feasibility and pedagogical impact of integrating sustainability-focused modules within architecture and engineering design studios. Through the development, assessment, and implementation of these targeted interventions, the present work seeks to understand how interdisciplinary and experiential learning approaches promote deeper engagement with sustainability principles among engineering students.

Addressing the research questions directly, the findings indicate that incorporating sustainability modules within course curricula improved students’ comprehension and their ability to apply these concepts in design decision-making. The quantitative findings reflect the statistical significance and improvements in students’ knowledge and understanding, while the qualitative findings demonstrate students’ collaborative, communicative, and critical thinking abilities. Students highlighted that sustainability modules helped them to link theory with practice, promoting self-confidence in addressing sustainability challenges and fostering a broader, system-oriented perspective towards design and problem-solving.

The key contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- It introduces a structured, evidence-based framework for integrating sustainability interventions within architectural engineering design studios, adaptive to similar programs such as construction, structural engineering, civil engineering, urban planning, and allied disciplines.

- Combining project-based, peer-driven, and reflective exercises leads to measurable improvement in learning and comprehension capabilities among students.

- The proposed framework bridges the gap between theory and practice, offering a strategic teaching model that aligns with the traditional learning-by-doing and project-based learning approaches.

- The mixed-methods approach is validated in assessing cognitive and behavioral learning outcomes, contributing to the existing body of knowledge and emerging works in the literature on sustainability literacy.

- Actionable insights are provided for practitioners and course instructors seeking to align architectural engineering programs with accreditation standards (such as ABET), highlighting sustainability as a core competency for future engineers.

A significant contribution of this work is its demonstration of incorporating sustainability education within studio-based, interdisciplinary settings, fostering not only technical proficiency but also ethical consciousness, teamwork, and creativity. This supports the idea that sustainable design education should extend beyond traditional lectures or courses, promoting students in practical, problem-solving settings that reflect actual professional experiences. These findings suggest that educators and curriculum designers should integrate sustainability modules directly within design studios, emphasize collaborative learning, and employ reflective assessments to strengthen sustainability literacy.

However, several challenges were identified during practical implementation that constitute the following: (1) time limitation in existing studio courses can prohibit in-depth exploration of sustainability, (2) some students with prior knowledge of sustainability principles led to differences of opinion and additional instructor coordination, and (3) sustainability integration among different disciplines requires careful facilitation to maintain consistency in learning outcomes. While these challenges were expected in exploratory research, they provided significant insights into guiding adjustments that needed to be made in the module’s design and implementation.

The outcomes of this work extend beyond architectural engineering education, and the findings could inform other disciplines within the built environment, such as civil, environmental, and mechanical engineering, where it’s crucial to integrate sustainability concepts into hands-on courses. The work also contributes to the broader discourse on reshaping engineering education to adopt a more human-centered, systems-oriented approach that prioritizes sustainability literacy as an essential professional competency. Future research will expand upon the current work by including larger and more diverse cohorts, multidisciplinary collaborations, and longitudinal data collection to evaluate long-term knowledge retention and behavioral change. Moreover, subsequent studies should explore additional sustainability dimensions, including social equity, circular economy practices, and environmental justice, to ensure that sustainability education remains holistic and socially relevant.

To sum up, this work underscores that sustainability education in architectural engineering should not be treated as an add-on, but rather as a central and core framework that shapes how future engineers think, design, and act. By integrating empirical analysis with educational innovation, the research presents a pathway for reimagining engineering education as a driver for sustainable development—equipping graduates to lead with integrity, creativity, and a forward-looking vision in the built environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.; methodology, F.A.; software, F.A. and M.R.S.; validation, F.A.; formal analysis, F.A. and M.R.S.; investigation, F.A.; data curation, F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A. and M.R.S.; writing—review and editing, F.A. and M.R.S.; visualization, F.A. and M.R.S.; supervision, F.A.; project administration, F.A.; funding acquisition, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors therefore acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for providing technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocols received approval from the University’s IRB, highlighting the procedures and recruitment strategy involved for human subjects under the Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) for the STUDY00023850.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to King Abdulaziz University for providing academic support and research resources throughout the development of this study. They also express their gratitude to the students and faculty who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moradi-Aliabadi, M.; Huang, Y. Decision Support for Enhancement of Manufacturing Sustainability: A Hierarchical Control Approach. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4809–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, H.; Hirsh, J. Toward the Development of Robust Learning for Sustainability Core Competencies. Sustainability 2016, 9, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azapagic, A.; Perdan, S.; Shallcross, D. How Much Do Engineering Students Know About Sustainable Development? The Findings of an International Survey and Possible Implications for the Engineering Curriculum. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, Y. Cultural Dynamics for Sustainability: How Can Humanity Craft Cultures of Sustainability? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 29, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiano-Phan, R.; Soares Gonçalves, J.C. Sustainability in Architectural Education—Editorial. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Stephan, A.; Purwaningrum, R.D.A.; Gulzar, S.; De Vecchi, R.; Ahmed, M.; Candido, C.; Sadek, A.H.; Qrayeiah, W. Practices contributing to building sustainability: Investigating opinions of architecture students using partial least squares structural equation modeling. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendawy, M.; Junaid, M.; Amin, A. Integrating sustainable development goals into the architecture curriculum: Experiences and perspectives. City Environ. Interact. 2024, 21, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassani, F.; Saleem, M.R.; Messner, J. Integrating Sustainability in Engineering: A Global Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, A.M. Links Between The Pillars Of Sustainable Development. Ann. Univ. Craiova—Econ. Sci. Ser. 2012, 1, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Belu, R.; Chiou, R.; Tseng, T.L.; Cioca, L. Advancing Sustainable Engineering Practice Through Education and Undergraduate Research Projects. ASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Expo. 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.K.; Pelkey, J.; Noyes, C.; Rodgers, M.O. Using Kolb’s Learning Cycle to Improve Student Sustainability Knowledge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsec, S.; Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M. Investigating Possibilities of Developing Self-Directed Learning in Architecture Students Using Design Thinking. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, T.; Hernandez, R.J. Thirty Years of Design for Sustainability: An Evolution of Research, Policy and Practice. Des. Sci. 2021, 7, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamón, L.A.S.; Martinho, A.P.; Ramos, M.R.; Aldaz, C.E.B. Do Spanish Students Become More Sustainable after the Implementation of Sustainable Practices by Universities? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Snelgrove, S. Theme in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.K.; Barrella, E.; Wall, T.; Noyes, C.; Rodgers, M. Comparing Measures of Student Sustainable Design Skills Using a Project-Level Rubric and Surveys. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callewaert, J. Sustainability Literacy and Cultural Assessments. In Handbook of Sustainability and Social Science Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassani, F. Instructional Resources for Sustainability Modules. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 31, pp. 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–488. [Google Scholar]

- Doorn, J.V.; Ly, A.; Marsman, M.; Wagenmakers, E.J. Bayesian Rank-based Hypothesis Testing for the Rank Sum Test, the Signed Rank Test, and Spearman’s ρ. J. Appl. Stat. 2020, 47, 2984–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, L.M.; Schmidt-Kraepelin, M.; Treiblmaier, H.; Sunyaev, A. The Influence of Gamified Workshops on Students’ Knowledge Retention. In Proceedings of the GamiFIN Conference, Pori, Finland, 21–23 May 2018; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, S.; Power, J.; Blom, N.; Tanner, D. Engineering Students’ Perceptions of Problem and Project-based Learning (PBL): Comparing Online and Traditional Face-to-Face Environments. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fàbregues, S.; Sakakibara, R. Visuals in Joint Displays to Represent Integration in Mixed Methods Research: A Methodological Review. Methods Psychol. 2021, 5, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L.G.I.; Clavijo, F.V.; Robles-Gómez, A.; Pastor-Vargas, R. A Sustainable Educational Tool for Engineering Education Based on Learning Styles, AI, and Neural Networks Aligning with the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timans, R.; Wouters, P.; Heilbron, J. Mixed Methods Research: What it is and What it Could Be. Theory Soc. 2019, 48, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, R.; Miller, S.R.; Simpson, T.W.; Meisel, N.A. The Earlier the Better? Investigating the Importance of Timing on Effectiveness of Design for Additive Manufacturing Education. In Proceedings of the ASME 2018 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 26–29 August 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skukauskaite, A. Constructing Transparency in Designing and Conducting Multilayered Research in Science and Engineering Education—Potentials and Challenges of Ethnographically Informed Discourse-based Methodologies. In Theory and Methods for Sociocultural Research in Science and Engineering Education, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018; pp. 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, Y. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).