Abstract

The Former General Electric Utility in Japan is a major participant in the electricity market. The integrated operational capabilities of these power companies have significant impacts on the stable development and sustainability of the power industry. This study evaluates the comprehensive operational capabilities of these power companies from 2003 to 2015 and analyzes the indicators that may affect their operational capabilities. Establishing an evaluation index system comprising five subsystems, namely profitability, management, solvency, growth, and scale, and optimizing it using principal component analysis. The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution was utilized to calculate the relative closeness of each company, with a score representing the integrated operational capabilities. Furthermore, coupling coordination and grey correlation analyses were conducted to assess the internal coordination among subsystems and to identify critical drivers of sustainable performance. The results show that (1) the Kyushu Electric Power Company and Tohoku Electric Power Company have strong integrated operational capabilities. (2) The five evaluation subsystems of integrated operational capability during the period of 2003–2015, fluctuated between moderate and high levels. (3) The top 5 indicators with the highest average grey correlation are as follows: “Hydropower capacity factor”, “Operating cash flow to current liabilities ratio”, “Operating profit growth rate”, “Net profit growth rate”, “Total capital utilization”. This study contributes to the sustainable management of the electricity industry by providing a systematic and data-driven assessment framework. The findings offer practical insights for optimizing corporate governance, enhancing energy efficiency, and formulating policy measures that support the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of Japan’s power utilities.

1. Introduction

The electric power industry is an important pillar of the national economy and people’s lives. Since Japan revised the “Electricity Business Act” in 1995 [], the power system has undergone five reforms. The electric power market was deregulated; this introduced competition in stages and was fully liberalized in 2016 []. Therefore, competition among electric power companies has also intensified. In the current era of energy resource scarcity, the efficient management of electricity providers and the enhancement of their competitiveness have become pressing issues. As the demand for electricity continues to rise and traditional energy sources face challenges, electricity providers must find innovative ways to optimize their operations, adopt sustainable practices, and explore alternative energy sources to meet energy needs.

The Former General Electric Utility in Japan (FGEUJ) comprises companies primarily engaged in electricity transmission and distribution within its supply area through the ownership and operation of the following electrical facilities: Hokkaido Electric Power Company (HEPCO), Hokuriku Electric Power Company (RIKUDEN), Okinawa Electric Power Company (OKIDEN), Tohoku Electric Power Company (TOHOKU), Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO), Kansai Electric Power Company (KEPCO), Kyushu Electric Power Company (KYUDEN), Shikoku Electric Power Company (YONDEN), Chubu Electric Power Company (CHUDEN), and Chugoku Electric Power Company (ENERGIA). In 2016, with the full liberalization of the electricity market in Japan, the distinctions between general electricity utility and specified scale electricity utility were abolished and the term former general electricity utility began to be used. Evaluating and analyzing the comprehensive operational capabilities of FGEUJ can provide vital references and a basis for the management and decision-making of power companies, facilitating the promotion of sustainable development and transformation in the power industry, leading to an improved understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, and allowing for the formulation of targeted development strategies and measures [].

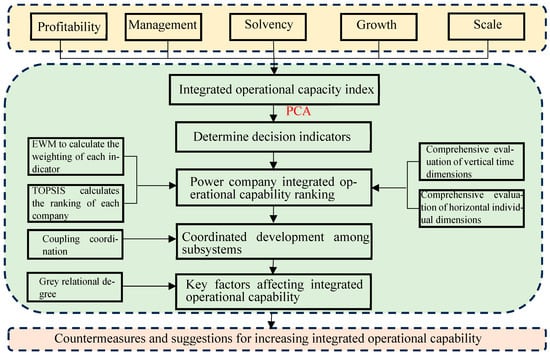

Against this backdrop, this study focuses on 10 FGEUJ members, which are major power companies in Japan. Addressing the issue of subjective evaluation methods prevalent in some studies, a five-subsystem evaluation framework is established by considering multiple evaluation indicators. Principal component analysis (PCA) is used to eliminate indexes that have high relevance but low interpretability to avoid redundancy in evaluation. The study utilizes the entropy-TOPSIS method to calculate the relative closeness of each electricity provider to the positive and negative ideal points, which serves as their comprehensive operational capability score, thereby ensuring a more objective and exhaustive assessment of operational capabilities. This approach is designed to reducing the impact of personal views and preferences. Additionally, the coupling coordination and grey correlation degree models are combined to provide a comprehensive assessment of the operational capabilities of each electricity company (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

2. Literature Review

The following literature review (Table 1) appears following multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) and the evaluation of power companies.

Table 1.

Overview of the MCDM literature.

2.1. Research on MCDM

As for comprehensive evaluation methods, data envelopment analysis (DEA), analytic hierarchy process, Delphic, entropy weight method (EWM), fuzzy evaluation method and technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) method are commonly used and a large number of practical problems have been solved.

Hashemi et al. [] proposed an integrated green supplier selection model that considers economic and environmental criteria. The model incorporates the analytic network process to handle interdependencies among the criteria and introduces an improved version of grey relational analysis (GRA) to address uncertainties in supplier selection decisions. Dai and Niu [] proposed combination weighting method with improved group order relation method and entropy weight method to evaluate the sustainable development of power grid enterprises. Alizadeh et al. [] focused on the performance evaluation of complex electricity generation systems using a dynamic network-based DEA approach. Considering the dynamic nature of the interconnected components, they proposed a novel method to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of electricity generation systems. Nguyen et al. [] utilized exploratory factor analysis and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling approach to investigated the influence of organizational learning and network involvement, along with contextual factors, on the innovation capability and operational performance of power generation businesses in Vietnam. Shuai et al. [] incorporated the projection pursuit technique and the TOPSIS model to assess the international competitiveness of renewable energy products exported from the United States, China, and India. Zhang et al. [] proposed a novel hybrid model integrated the Bayesian best–worst method (BWM) and the multi-attribute ratio to evaluate the market-oriented business regulatory risk of power grid enterprises. The objective is to provide a comprehensive and reliable assessment of business regulatory risk from a market-oriented perspective. Yuan and Song [] employed the entropy TOPSIS method for the assessment of solar cell companies’ technology innovation capabilities, which allowed the consideration of multiple criteria in the evaluation process. Liu et al. [] developed a system comprising 16 sub-indicators aimed at quantifying a composite energy vulnerability index (EVI). They utilized entropy weightings to compute the average EVI for each country from 2000 to 2019. MCDM methods have also been widely applied across environmental and resource-related studies. Prior research has used PCA for ecological assessments [], AHP and entropy weighting for hydrogen technology selection [], and TOPSIS for optimizing energy systems []. Additional applications include groundwater evaluation [], urban livability assessment [], sustainable machining optimization [], and ecological vulnerability analysis []. These studies highlight the broad applicability of MCDM in supporting sustainability-oriented decision-making.

2.2. The Evaluation of Power Companies

Chatzimouratidis and Pilavachi [,] conducted a comprehensive evaluation of 10 different types of power plants considering their technological, economic, and sustainability aspects using analytic hierarchy process. Nine end node criteria are hierarchically structured and evaluated, with subjective criteria weighting determined through pairwise comparisons. Zheng et al. [] proposed a comprehensive model for evaluating the operational capacity of regional power grid companies. The model incorporates an evaluation index system based on information entropy theory to determine objective weights and employs the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method for assessment. The research aims to enhance supervision, management, and safety while ensuring efficient and high-quality network operations. Zhao et al. [] proposed a novel hybrid framework for evaluating the performance of thermal power enterprises from a sustainability perspective. Initially, the evaluation criteria are determined based on the principle of a sustainability balanced scorecard, encompassing environmental and sustainable perspectives to address corporate social responsibility concerns. Considering the ongoing electricity market reform in China, You et al. [] utilized BWM to determine criteria weights and applied TOPSIS to rank the performance of power grid enterprises. The evaluation index system is based on sustainability, comprising three criteria, economy, society, and environment. Huang et al. [] established an index system focused on four aspects, for evaluating the sustainable development capability of six representative electric power enterprises. Notably, using only four indicators may not provide a comprehensive and scientifically rigourous assessment of sustainable development capability. Considering economic and environmental criteria simultaneously, Alao et al. [] utilized the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method to select the optimal waste-to-energy technology for electricity generation in Lagos, Nigeria. The technique effectively ranked technological options based on waste stream analysis in Lagos, Nigeria, and revealed the most favourable waste-to-energy technology solution.

These various studies demonstrate the diverse methodologies and evaluation frameworks used to assess the performance, sustainability, and competitiveness of power sector. The integration of various evaluation methods and criteria helps in promoting sustainable development, optimizing resource allocation, and making informed policy decisions for the future growth and success of the electricity sector. But the current design of comprehensive evaluation criteria system has not yet formed a unified standard.

The innovations of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- The construction and optimization of the evaluation indicator system

To comprehensively evaluate the integrated operational capacity of the power company, it is essential to consider not only economic efficiency indicators but also other sustainable development indicators, such as scale and growth. In this paper, the evaluation indicator system for integrated operational capacity of power company is constructed from the five dimensions of profitability, solvency, management, growth, and scale. Considering the possibility of multicollinearity between indicators, which affects the evaluation results, we use PCA to remove invalid indicators.

The dynamic assessment is conducted on panel data across longitudinal time and horizontal individual dimensions using the entropy weight method

For the evaluation of the integrated operational capacity, the dynamic assessment is conducted on panel data across longitudinal time and horizontal individual dimensions using the entropy weight method. The entropy weighting method provides an entirely objective approach to calculating the weights of evaluation indicators, devoid of reliance on subjective expert experience. This approach allows evaluations to be conducted even without the involvement of relevant decision-makers. The evaluation process, which does not rely on expert subjective opinions, provides convenience for those who may have difficulty accessing experts or relevant decision-makers. This includes organizations, researchers, and institutions conducting assessments in remote areas, industries with limited expert availability, or in situations where time constraints or budget limitations make expert consultations impractical.

The assessment of the level of coordination and development among evaluation subsystems is conducted using coupling coordination model

In order to evaluate the integrated operational capacity, power companies should not only ensure the composite score but also analyze the coordination and development levels among various subsystems. The coupling coordination model aids in quantifying the coordinated development across various evaluation subsystems within electric power companies.

The methodology and outcomes of this research provide vital references and a basis for the management and decision-making of power companies, facilitating the promotion of sustainable development and transformation in the power industry. Evaluating and analyzing the comprehensive operational capabilities of power companies can lead to an improved understanding of their strengths and weaknesses and allow the formulation of targeted development strategies and measures

In summary, this study aims to focus on the key elements that impact the operational capabilities of electricity providers and achieve the goal of sustainable development by promoting coupling coordination among various subsystems.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Indicator System Construction

Grounded in the balanced scorecard [,], the resource-based view [], and the dynamic capabilities framework [] foundational theoretical perspectives, this study constructs a multidimensional evaluation system comprising five subsystems: profitability, management, solvency, growth, and scale. Subsystems profitability and solvency directly reflect traditional economic and financial health objectives and form the basis for assessing both short-term and long-term returns on investment. Management captures firms’ internal business processes and operational efficiency, consistent with the balanced scorecard’s emphasis on process optimization. Scale highlights strategic positioning and firms’ resource commitments to future sustainability transitions, linking financial scale to structural shifts in low-carbon development. Growth evaluates the firm’s ability to continuously adapt and reconfigure its resource base, which is a central concept within dynamic capabilities theory. Meanwhile, further subdivision of the influencing factors revealed several indicators under each subsystem. Considering the possible correlation between secondary factors, PCA is applied to the dimension reduction of indicators, yielding the final 26 secondary indicators for electric power company evaluation. Table 2 describes and analyzes the 5 major indicators and 26 secondary indicators [].

Table 2.

Evaluation index system for the assessment of integrated operational capability of power companies.

The correlation coefficient matrix of six profitability indicators: ROA, Return On Equity (ROE), EBITDA, Operating Profit Margin, Pre-Tax Profit Margin, and Net Profit Margin, for the 10 general electric companies is shown in Table 3. The table reveals that ROA has a significant positive correlation with Operating Profit Margin and Pre-Tax Profit Margin. ROE also shows a high correlation with Net Profit Margin, and Operating Profit Margin has a strong correlation with Pre-Tax Profit Margin.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Profitability.

The intercorrelations among evaluation indicators should not be excessively high to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the integrated operational capabilities of each electric power company and to avoid redundant evaluations. Therefore, PCA is used to reduce the dimensionality of the indicator variables based on the principal component loadings. The PCA results are shown in Table 4; the contribution rate of the first principal component is 80.94%, exceeding 80%, and containing most of the variable information. Table 5 presents the principal component loadings, indicating the correlation between the principal components and each indicator variable. Large absolute loadings represent significant contributions of the corresponding indicator variables to the principal components, thus demonstrating high explanatory power.

Table 4.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on Profitability.

Table 5.

Load of the first principal components on the original index of Profitability.

Based on the magnitudes of the loadings and considering the intercorrelations among indicator variables, ROA, EBITDA, Pre-Tax Profit Margin, and Net Profit Margin are ultimately selected as the evaluation indicators for the profitability evaluation dimension.

Overall, a similar approach is applied to reduce the evaluation indicators for other evaluation subsystems. The results of PCA are shown in the Appendix A. The indicators for the growth capability subsystem show weak correlations; therefore, PCA is not required. The installed capacity and capacity factor of power generation equipment reflect the unique characteristics of the operations of each electric power company compared to others. Therefore, they are included in the evaluation indicator system. In addition to the installed capacity of each power generation equipment, the scale subsystem also selects the Total Capital Employed as the evaluation indicator. This process results in a comprehensive evaluation index system comprising 26 indicators across five subsystems.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Principal Component Analysis

PCA is a statistical data dimensionality reduction method that involves performing an orthogonal transformation on a set of original variables, recombining them into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components. These components capture as much of the original variable or indicator information as possible. The selection of a reduced set of indicators that reflect the main influences on the comprehensive operational capabilities of electric power companies is possible via PCA.

The use of STATA17 software for PCA allows for the reduction of multidimensional variables, helping to identify the key indicators having the most significant impact on the operational capabilities. This approach enables researchers to focus on electricity companies’ most relevant and meaningful indicators while effectively avoiding redundant evaluation [].

The procedure is as follows.

Step 1: Calculate the matrix. The m samples n indicators represent the Z-score standardized data matrix as shown below:

Step 2: Calculate the correlation coefficient matrix.

where is the average value and is the correlation coefficient of the original variables and .

Step 3: Solve characteristic equation (E is the identity matrix) to obtain initial eigenvalues and arrange them in descending order of size as λ1 ≥ λ2 ≥ … ≥ λp ≥ 0.

Step 4: Compute the eigenvectors corresponding to the eigenvalues from the following equation:

where should satisfy the condition .

The selection of principal components is implemented in accordance with the accumulative contribution rate Q:

Generally, m (m ≤ p), which corresponds to Q ≥ 80%, is the recognized number of principal components.

3.2.2. Entropy-TOPSIS Method

In 1948, Shannon introduced the concept of entropy in information theory as a means to represent the uncertainty of information []. This approach considers the properties of information entropy and the transmission characteristics of information, allowing for the comparison of the amount of information contained in each indicator. Different units for various evaluation indicators may be available when evaluating the operational capabilities of electric power companies, making direct comparisons challenging. For example, total capital may be measured in million yen, while equipment capacity may be measured in kilowatts. Thus, data normalization and entropy weighting are commonly used to calculate the weightings of indicators to address this issue.

TOPSIS is primarily used to solve multi-objective decision-making problems. In this methodology, solutions are evaluated using positive ideal solutions and negative ideal solutions. The positive ideal solution is considered the optimal solution and is the one with the best attribute values of the alternatives. In other words, the positive ideal solution has the highest values for all attributes. By contrast, a negative ideal solution is the worst; that is, it has the lowest attribute values. The negative ideal solution has the lowest values for all attributes.

TOPSIS calculates the Euclidean distance between the evaluation data and the positive and negative ideal solutions: the solution performs effectively when the distance is close to the positive ideal solution, and the solution is less desirable when the distance is farther from the negative ideal solution. Therefore, the optimal solution is the one closest to the positive ideal solution and farthest from the negative ideal solution. The relative ratings of each electric utility are calculated and ranked using TOPSIS, and their operational capabilities are evaluated.

The specific steps can be described as follows.

(1) Standardization

The data matrix of indicators selected after PCA dimensionality reduction to study the issue of comprehensive business capacity of electric utilities is shown below:

where represents the benefit or cost indicators.

For each evaluation indicator, high and low values of the benefit and cost indicators, respectively, indicate superior performance. However, each evaluation indicator may have different units; thus, a direct comparison of the actual values is impossible. Therefore, standardization of the original data is necessary to increase the comparability of indicators and ensure a fair evaluation []. Maximum–minimum standardization was adopted in this study. The standardized formula for benefit indicators is as follows:

The standardized formula for cost indicators is as follows:

where and represent the maximum and minimum values of the same indicator in each scheme, respectively.

(2) Information entropy of criteria

The entropy of the j-th index is

When , is meaningless, is changed to 0 and its consistency with the entropy meaning.

(3) Calculation of weights

Based on entropy, the entropy weight of the j-th valuation indicator is defined as

(4) Calculation of the attribute matrix

Once the entropy weights have been determined, they can be added to the standardized matrix to obtain the index attribute matrix A.

(5) Calculation of positive and negative ideal points

If the positive ideal point is and the negative ideal point is , then according to the definition of an ideal point,

If the j-th indicator is of the benefit type, then the formulas for calculating positive and negative ideal points are Equations (15) and (16), respectively.

If the j-th indicator is of the cost type, then the formulas for calculating positive and negative ideal points are Equations (17) and (18), respectively.

(6) Calculation of the Euclidean distance between the evaluation data and the positive and negative ideal points

Assuming that the distances from each scheme evaluated to the positive and negative ideal points are and , the following is obtained:

An evaluation scheme is optimal when the distance to the positive and negative ideal points is the closest and farthest, respectively. However, in actual evaluation and selection, schemes that satisfy both conditions are often unavailable. Therefore, a relative proximity is defined. is the ratio of the distance to the negative ideal point to the sum of the distances to the positive and negative ideal points.

(7) Calculation of relative closeness

A large degree of proximity leads to superior general management capabilities.

3.2.3. Coupling Coordination Model

This paper divides the evaluation system for the comprehensive operational capabilities of electric power companies into five evaluation subsystems. The degree of coordinated development between different evaluation subsystems can be measured by calculating the coupling coordination degree. High values of the coupling coordination degree indicate a close and coordinated relationship between the evaluation subsystems, while low values indicate a weak or less coordinated relationship between the subsystems. The model is as follows []:

where D denotes the coupling coordination degree; C is the coupling degree; T represents the comprehensive coordination index; represent the comprehensive evaluation value of each evaluation subsystem; and are the undetermined coefficients that satisfy the following condition: . In this case, each evaluation dimension is considered equally important. Thus, the coefficients are set to be .

3.2.4. Grey Relational Degree Model

This study uses the GRA model to calculate the correlation degree of each evaluation indicator to evaluate their impact on the integrated operational capabilities and identify the most critical factors. A high correlation degree indicates a strong influence of that indicator on the integrated operational capabilities of electric power companies. The calculation steps are presented as follows [,]:

(1) Normalize the variables to be dimensionless.

(2) Calculate the correlation coefficients.

where denotes the reference series (herein refers to the integrated operational capabilities score), denotes the comparison series (herein refers to the data of each evaluation index), and denotes the discrimination coefficient. The range of values is [0, 1] and is often taken as 0.5.

(3) Calculate the grey correlation r.

4. Results

The capacity factor of the power supply equipment of power companies is no longer recorded by the Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan (FEPC) after the full liberalization of the electricity sector in 2016. Thus, the capacity factor of various power supply equipment, which is calculated on the basis of the electricity generated as reported in the annual securities reports of each electric power company, may reflect the actual situation inaccurately, thus leading to significant discrepancies. Therefore, considering the availability of the indicator data, this paper selects the data of 10 FGEUJ from 2003 to 2015.

4.1. Evaluation of Power Companies’ Integrated Operational Capability: TOPSIS Approach

Based on information entropy theory, the weights of 26 indicators are calculated, as shown in Table 1, in accordance with Equations (5)–(11).

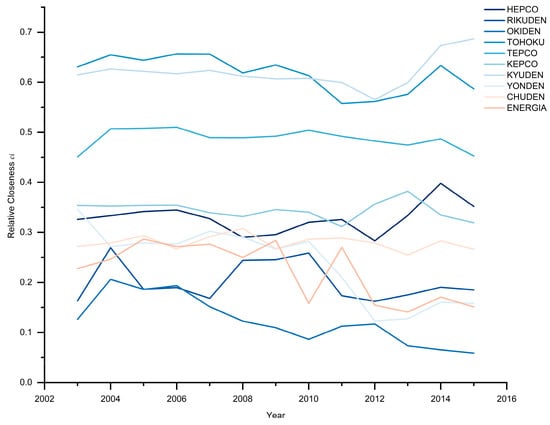

4.1.1. Dynamic Evaluation of the Competitiveness of Power Company Integrated Operational Capability

The relative closeness of the integrated operational capabilities of the 10 FGEUJ from 2003 to 2015 was calculated in accordance with Equations (12)–(21). A high calculated value indicates a relatively high level of integrated operational capability among the 10 electric power companies. A longitudinal time dimension comparison was conducted to analyze the variations in companies’ operational capabilities and further explore the dynamic changes in their integrated operational capabilities. The results are shown in Figure 2. These values indicate the level of relative closeness between each company in the evaluation. High values indicate better performance or a stronger integrated operational capacity compared to other companies. Conversely, low values suggest relatively weaker performance or less integrated operational capacity compared to the top-performing companies.

Figure 2.

Trends of relative closeness from 2003 to 2015.

The integrated operational capability scores of KYUDEN, TOHOKU, and TEPCO are significantly better than those of other power companies. Moreover, TOHOKU and TEPCO showed a downward trend in scores because of the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, while KYUDEN has demonstrated rapid growth since 2011. The total capital employed index of TEPCO is higher than that of other power companies in terms of scale; however, its integrated operational capability scores after considering the installed capacity of each power source and the capacity factor of each power supply equipment have moved from the first place, where it had an advantage, to the third place. This finding is due to the dominant positions of Kyushu and Tohoku Electric Power considering hydro/new energy capacity factor and installed equipment utilization, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Capacity factor of TEPCO, TOHOKU, and TOHOKU from 2003 to 2015.

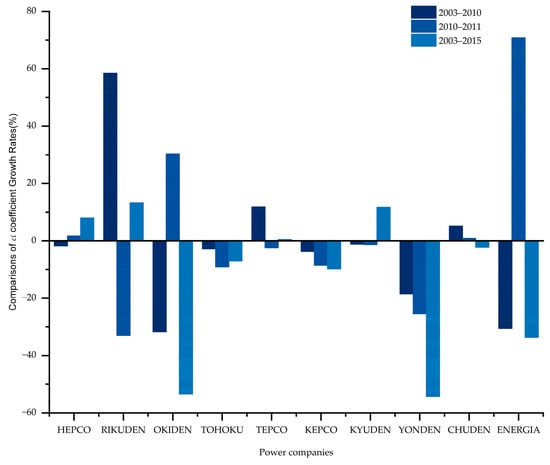

This study calculated the growth rate of the integrated operational capability scores for each company from 2003 to 2015 to compare the development trends of the integrated operational capabilities among the electric power companies in this study. Considering the significant impact of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake on TEPCO and TOHOKU, the years 2010 and 2011 were identified as key time points, and the growth rates for the periods 2003–2010 and 2010–2011 were calculated separately. The results are shown in Figure 3. The growth rate of TEPCO and TOHOKU from 2003 to 2015 was significantly lower than that from 2003 to 2010 because of the impact of the earthquake.

Figure 3.

Growth rates of the integrated operational capability of power companies.

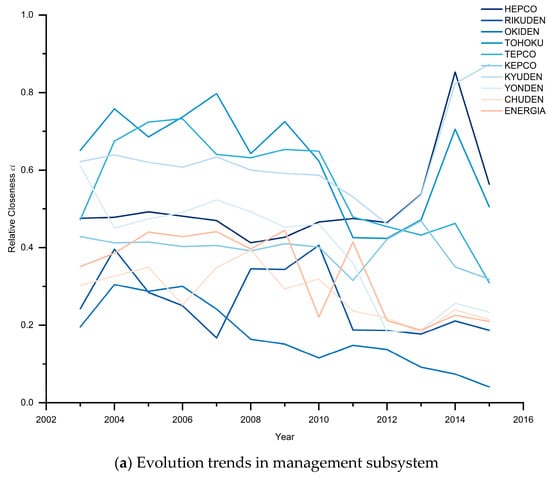

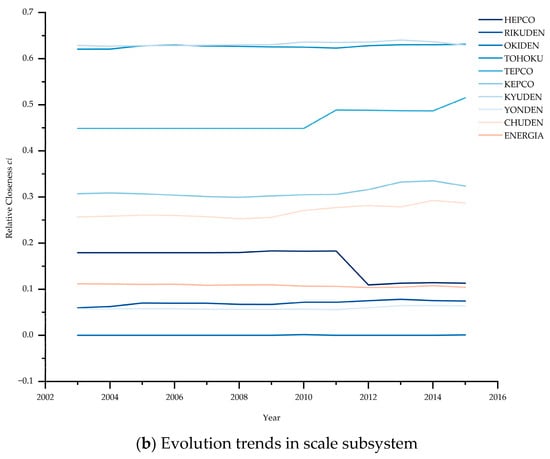

This study calculated the changes in relative closeness of the five evaluation subsystems to further analyze the trends in the various evaluation subsystems of integrated operational capabilities, as shown in Figure 4. The profitability, solvency, and growth subsystems, which are highly correlated with the economy indicators, showed significant variations and did not exhibit a clear pattern from 2003 to 2015. By contrast, the management and scale subsystems showed certain regularities.

Figure 4.

Evolution trends in different evaluation subsystems.

First, in the management subsystem, which includes the capacity factor of each power source, KYUDEN and TOHOKU have shown rapid growth since 2011, while TEPCO has demonstrated a downward trend. These trends are mainly due to the high capacity factor of new energy and hydropower equipment from KYUDEN and TOHOKU, respectively. In the scale subsystem, TEPCO has a high Total Capital Employed. However, KYUDEN and TOHOKU have a dominant position when considering overall scale because of their high share of new energy and hydropower installed capacity.

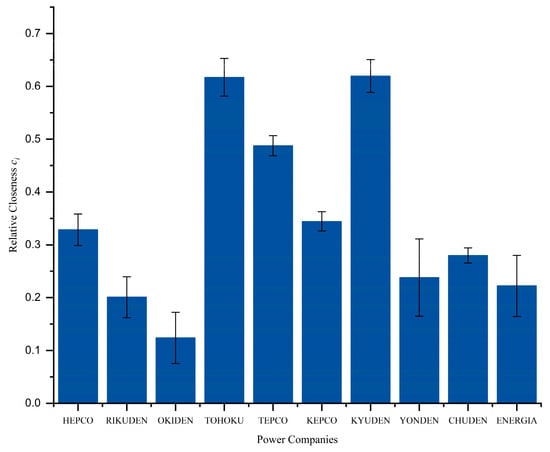

4.1.2. Horizontal Individual Dimension Evaluation and Analysis

By comparing the integrated operational capability of the 10 FGEUJ power companies in the horizontal individual dimension, their individual differences are analyzed to explore ways to improve integrated operational capability from an individual perspective. The mean value of the evaluation of the integrated operational capability of FGEUJ from 2003 to 2015 is plotted, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Average results of the power companies’ integrated operational capability from 2003 to 2015.

Figure 5 shows that the top three companies in the quantitative calculation of integrated operational capacity are KYUDEN, TOHOKU, and TEPCO, and the values of relative closeness of integrated operational capacity are 0.6196, 0.6172, and 0.4876, respectively.

The Kyushu region possesses abundant geothermal resources, and KYUDEN has capitalized on this advantage by actively promoting geothermal power generation projects. Renewable energy and technical innovation can improve sustainability []. By leveraging these rich geothermal resources, KYUDEN has contributed to the development of renewable energy and the transition toward sustainable energy.

TOHOKU is exceptional when considering the hydropower capacity factor. Being the electricity supplier in the Tohoku region of Japan, the company benefits from the abundant hydro resources in that area. TOHOKU has also made notable progress in the field of renewable energy by actively utilizing hydropower equipment, and its advantage in terms of the hydropower capacity factor is particularly evident. As one of the largest electric power companies in Japan, TEPCO provides electricity supply services in Tokyo and its surrounding areas. The size and market share of TEPCO contribute to its role as a major participant in the Japanese power industry.

4.2. Coupling Coordinated Analysis

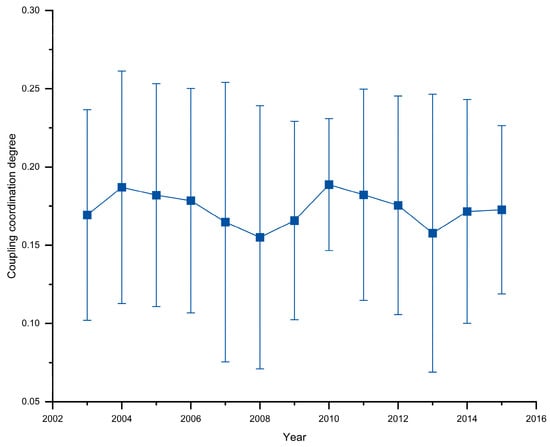

After conducting longitudinal and horizontal individual dimension evaluation and analysis of the integrated operational capabilities of the 10 FGEUJ power companies and establishing a coupling coordination model, the level of coordination and development among C1, C2, C3, C4 and C5, for the FGEUJ during 2003–2015 was studied. The coupling coordination degrees for each evaluation subsystem were calculated using Formulas (22)–(24), as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Coupling coordination degree of the integrated operational capability evaluation subsystem.

Wang et al. [] revealed that the coupling coordination degree of subsystems 0.40–0.49 and 0.50–0.79 is medium and high coupling coordination, respectively. The five evaluation subsystems of integrated operational capability during the period of 2003–2015, namely, profitability, management, solvency, growth, and scale, fluctuated between moderate and high levels. No trend of extreme coupling coordination development was observed before 2015. The evaluation value of profitability is considerably higher compared to the other subsystems, indicating strong performance in this aspect. By contrast, the evaluation values of the solvency capacity and scale subsystems are notably lower than the other subsystems, indicating weak performance in these areas. Therefore, a large deviation exists in the coordinated relationship between the subsystems, demonstrating a highly significant impact on the overall coordinated development among the five subsystems.

The substantial difference in evaluation values among the subsystems can lead to imbalanced development, where a few aspects excel while others lag. This imbalance can hinder the overall coordinated development of the power companies. The power companies must focus on improving the coordination and synergy among the five evaluation subsystems to further enhance the overall integrated operational capacity and achieve highly stable, sustainable development. Therefore, efforts to improve and enhance the performance of the solvency and scale subsystems are crucial to achieving a harmonious and well-rounded development of the integrated operational capabilities in the power industry.

In recent years, the comprehensive development of the operational capability of power companies has evolved beyond only focusing on profitability indicators. Emphasis on sustainable development, which includes initiatives such as the development and utilization of renewable energy sources and increasing the capacity factor of various power generation equipment while prioritizing environmental conservation, is growing. Therefore, the integrated operational capabilities are expected to exhibit a highly coupled and coordinated development trend, reflecting the integration of various sustainable practices and strategies.

4.3. Grey Relational Analysis

Based on the established GRA model, the study analyzed the influence of the 26 selected evaluation indicators on the integrated operational capabilities of the 10 electric power companies. The GRA model helps in assessing the degree of correlation and relevance between the evaluation indicators and the integrated operational capabilities of the companies. The calculation of the grey relational degree is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Grey relational degree of integrated operational capability evaluation indexes.

The average relevance of each indicator across the 10 electric power companies was computed and ranked, and the top 5 indicators with the largest impact are as follows: the indicator “Hydropower capacity factor” of the “Management” subsystem has a relevance degree of 0.613; the indicator “Operating cash flow to current liabilities ratio” of the “Solvency” subsystem has a relevance degree of 0.624; the indicators “Operating profit growth rate” and “Net profit growth rate” of the “Growth capacity” subsystem have relevance degrees of 0.629 and 0.619, respectively; and the indicator “Total capital utilization” of the “Scale” subsystem has a relevance degree of 0.601.

These relevance degrees represent the impact of each indicator on the comprehensive management capabilities of the electric power companies. A high relevance degree indicates the substantial influence of the respective indicator on the overall performance of the companies. By focusing on indicators with high grey relational degrees, the companies can prioritize actions to address specific aspects of their operations and drive overall performance improvements.

5. Discussion

To further address the potential influence of the weighting process, we conducted a series of robustness checks to verify the reliability and scientific validity of the entropy-based objective weights used in this study. Based weighting schemes such as equal weighting, experience-based weighting, familiarity weighting, or hybrid AHP–TOPSIS frameworks can systematically quantify subjective preferences [,]. However, the primary purpose of this study is to avoid the potential bias introduced by expert judgement and to ensure that the ranking of power companies reflects data-driven, objective information. Therefore, objective entropy weights were adopted as the baseline. To validate the stability of this choice, two robustness strategies were implemented: (1) we altered the weights of each evaluation subsystem to simulate alternative weighting scenarios, and (2) we replaced the TOPSIS model with an alternative multi-criteria decision-making method (CODAS).

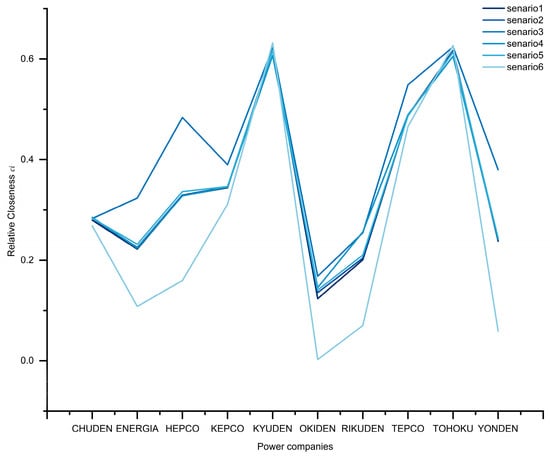

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis

To thoroughly verify the validity and scientific reliability of the evaluation indicator system, it is essential to adjust the weights of the indicators and perform a comprehensive sensitivity analysis. Scenario 1 is created with the current weight of the evaluation system. Scenarios 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 are obtained by increasing 100% the evaluation subsystem weights of C1, C2, C3, C4 and C5, respectively. The TOPSIS relative closeness ranking process can be recalculated to observe how the changes in weights impact the final ranking of alternatives. After performing the recalculations, Figure 7 presents the results of the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis graphs.

In a sensitivity analysis, altering the weights of the indicators had no impact on the evaluation results. The Spearman rank correlation coefficients between the weighted rankings and the initial rankings were 1.00, 0.94, 0.96, 1.00, and 0.95, respectively. Indicating a high degree of consistency and confirming that variations in subsystem weights do not materially affect the overall ranking pattern. The TOPSIS evaluation consistently shows that KYUDEN, TOHOKU, and TEPCO outperform other power companies. This suggests that the evaluation model is robust, meaning that the final outcomes are stable and not significantly influenced by variations in the assigned weights of the criteria. It should also be noted that because of the higher weight given to the ‘scale’ subsystem, the results of scenario 6 observed deviation with other scenario. This could be because the case company has not yet reached maturity in terms of greenness and managers still have greater emphasis on economic criteria compared to environmental criteria. Since C5 carries a large proportion of the total weight in this scenario, any changes in the subsystem significantly impact the final rankings. It also highlights the importance of carefully assessing the appropriateness of weights assigned to each indicator to ensure balanced and fair evaluation results.

5.2. Result of CODAS

To validate the decision-making process using the TOPSIS method and ensure the accuracy, consistency, and robustness of the obtained results, a comparison with the results based on CODAS method was conducted.

CODAS method is a MCDM technique that is particularly effective in solving complex decision-making problems with a focus on improving the differentiation between alternatives by considering both the Euclidean distance and the Taxicab distances from the Negative Ideal Solution (NIS). The alternative with the largest distance from the NIS is considered the best, as it indicates that the alternative is furthest from the worst-case scenario. Table 8 presents a comparison of the results obtained from the CODAS and TOPSIS methods.

Table 8.

Comparison of the results obtained from the CODAS and TOPSIS methods.

The ranking results derived from the CODAS method exhibited a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.95 with those obtained through the entropy-based TOPSIS model, indicating that both methods yield consistent conclusions when addressing this decision-making problem. This consistency enhances the credibility of the findings and suggests that the decision-making process is robust across different evaluation frameworks.

5.3. Methodological Limitations

Table 8 reports the TOPSIS results obtained using z-score normalization. The comparison with the baseline min–max approach indicates that the choice of normalization method materially affects ranking outcomes: the Spearman rank correlation between the two sets of results is 0.673, demonstrating only moderate concordance. This sensitivity arises because different scaling logics shape the dispersion structure of the indicators and thus influence both entropy-derived weights and the geometric characteristics underlying distance-based rankings. Specifically, z-score standardization centres variables and amplifies deviations from the mean, making it more responsive to outliers and heteroskedasticity, whereas min–max normalization maps values to a bounded interval and preserves proportional differences. Given that the entropy method relies on the probabilistic distribution of normalized values and TOPSIS depends on Euclidean distances to ideal solutions, these variations translate directly into non-trivial rank shifts.

For methodological coherence, the present study adopts min–max normalization as the primary preprocessing strategy. Min–max scaling yields non-negative, bounded values, which are more compatible with entropy calculations and provide stable distance metrics for TOPSIS. Accordingly, it aligns well with the integrated entropy–TOPSIS framework and ensures the consistency of indicator interpretation across subsystems.

Lastly, although the robustness checks performed in this study confirm that the main findings remain stable across alternative weighting schemes and evaluation models, a more comprehensive investigation of normalization-induced uncertainty represents a valuable direction for future research. Such work would deepen understanding of how preprocessing decisions, may influence policy-relevant rankings and thereby enhance the transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigour of operational capability assessment.

5.4. Implications

These findings have several important implications for decision-making.

Overall, based on the data from 2003 to 2015, the electricity system reform had an impact on the operational capabilities of electric power companies in Japan. Some companies achieved significant growth, while others faced challenges and declines. This trend reflects the intensifying market competition, the introduction of new business models, and the increasing importance of sustainable development in the Japanese power industry. Electric power companies must adopt proactive strategies and measures for internal reforms and organizational optimization to adapt to the new market environment and competitive demands.

When considering the growth rate of the integrated operational capabilities of each company from 2003 to 2015, KYUDEN, RIKUDEN, and HEPCO show high growth rates. TEPCO also has a positive growth rate, but it is relatively low. The rest of the companies exhibit negative growth rates. These differences may be attributed to the electricity system reform, which intensified market competition and introduced new business opportunities. The reform encouraged electric power companies to invest and develop in areas such as renewable energy development, energy efficiency improvement, and new technology applications. KYUDEN, RIKUDEN, and HEPCO might have made significant progress in these areas, better adapting to and leveraging the opportunities introduced by the reform, thereby enhancing their management capabilities.

In particular, KYUDEN superior trajectory is closely linked to its favourable geothermal and renewable resource base, and TOHOKU advantage is associated with abundant hydropower potential and correspondingly high capacity factors. Crucially, these natural endowments yielded lasting performance dividends only where firms exercised effective managerial choices. Reallocating investment toward high-utilization assets, improving maintenance and dispatch practices, and deploying technologies that raise asset productivity. Institutional shocks and policy shifts, notably the regulatory and market adjustments following the 2011 earthquake, further shaped firms’ incentives to adapt and thus magnified cross-company divergence in outcomes.

The evaluation framework developed in this study offers three concrete policy applications. First, it can inform the design of performance-based incentives: multi-indicator scores enable regulators to reward high utilization of renewable and low-carbon assets and to target support where it most effectively reduces emissions. Second, the framework supports benchmarking under market liberalization by providing comparable, time-consistent rankings that adjust for regional resource heterogeneity and thus facilitate targeted regulatory interventions for persistently underperforming firms. Third, the model allows for integration of renewable-generation metrics into regulatory assessment, since indicators such as hydropower, geothermal, nuclear and new-energy capacity factors are explicitly incorporated and can serve as measurable progress indicators toward carbon-neutrality goals.

Overall, the proposed system is more than a diagnostic instrument: it is a policy-relevant tool that can guide strategic planning, strengthen corporate governance, and help align utility performance with long-term decarbonization and sustainability objectives.

6. Conclusions

This study established an evaluation index system for the integrated operational capabilities of electric power companies and evaluated the integrated operational capabilities of FGEUJ from 2003 to 2015 based on the entropy-TOPSIS method. Additionally, the coupling coordination degree of evaluation subsystems was determined and the factors influencing the integrated operational capabilities that electric power companies should aim for in achieving sustainable development were identified.

(1) The integrated operational capability should include multiple factors, such as profitability, solvency, management, growth, and scale. A comprehensive evaluation index system for integrated operational capability is established, and PCA is applied to reduce dimensionality and eliminate indicators with high correlation but low explanatory power to avoid redundant evaluations. The EWM is used to calculate the weights of evaluation indicators, mitigating the impact of subjective understanding differences and the one-sidedness of objective data on the weights.

(2) The longitudinal analysis results (Figure 2) revealed that KYUDEN and TOHOKU have strong integrated operational capabilities, with KYUDEN showing rapid growth since 2012 and demonstrating significantly higher growth capability than other electric power companies. By contrast, OKIDEN and YONDEN are experiencing a declining trend. The remaining companies are mostly in a balanced development mode. The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake had varying degrees of impact on TOHOKU, TEPCO, and HEPCO, with TOHOKU experiencing a significant turning point.

(3) From the horizontal individual dimension analysis (Figure 5), the top three companies with the highest comprehensive evaluation scores are KYUDEN, TOHOKU, and TEPCO, demonstrating significantly higher average scores from 2003 to 2015 than other electric power companies.

(4) As can be seen from the level of coordinated development among the subsystems (Figure 6), to achieve extreme coupling coordination development goals in the power industry requires a shift from solely focusing on profitability indicators to a highly comprehensive consideration of overall management capabilities, especially in terms of sustainable development. Power companies should actively invest in and develop renewable energy projects, such as solar, wind, and geothermal, to reduce reliance on traditional fossil fuels; promote the use of clean energy; and minimize their impact on the environment. Additionally, improving the utilization of various power generation equipment is crucial. Such an improvement includes optimizing equipment operation plans, implementing excellent maintenance strategies, and reducing downtime. Companies can effectively utilize resources, improve power generation efficiency, and enhance economic performance by improving equipment utilization.

(5) Analyzing the correlation of various indicators (Table 7), the key indicators that have a significant impact on the integrated operational capabilities of the 10 power companies in this study include the following: the hydropower capacity factor, the operating cash flow to current liabilities ratio, the growth rates of operating profit and net profit, and the total capital utilization. Power companies can assess their operational status, solvency, profitability, and capital utilization efficiency by analyzing and monitoring these critical factors that influence integrated operational capabilities. Based on this assessment, they can develop corresponding strategies and propose corrective measures toward the achievement of sustainable transformation and development goals.

The sensitivity analysis and the comparative analysis of the CODAS results both indicate the reliability of the proposed indicator system and decision-making process. However, this study still has some limitations that will be addressed in future work in the following areas:

First, obtaining additional operational data from a large number of electric power companies after the electricity liberalization is desirable. Further research on management capabilities is needed to reflect the post-liberalization scenario accurately. Second, due to the lack of consistently reported and comparable environmental and social data across all companies and years, this study is limited to financial and operational indicators, with future work needed to incorporate standardized ESG metrics for a more holistic sustainability assessment. Thirdly, regarding the weighting of evaluation indicators in the evaluation system, verifying a highly scientific method by combining objective and subjective approaches is essential. The current method using the entropy approach is generally considered reasonable. However, developing a highly objective and reliable weighting method is crucial. These improvements can provide reliable results in the study of the operational capabilities of electric power companies, contributing to the industry’s overall development and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.; Methodology, B.M.; Software, B.M.; Validation, S.O.; Formal analysis, B.M.; Resources, S.O.; Writing—original draft, B.M.; Writing—review & editing, B.M.; Visualization, B.M.; Supervision, S.O.; Project administration, S.O.; Funding acquisition, S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Management.

Table A1.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Management.

| Asset Turnover Ratio | Equity Turnover Ratio | Value-Added Ratio | Operating Income to Operating Expenses Ratio | Operating Profit to Capital Employed Ratio | Capacity Factor of Hydropower | Capacity Factor of Thermal Power | Capacity Factor of Nuclear | Capacity Factor of New Energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 1 | ||||||||

| Equity Turnover Ratio | 0.4880 * | 1 | |||||||

| Value-Added Ratio | −0.2806 * | −0.4039 * | 1 | ||||||

| Operating Income to Operating Expenses Ratio | −0.3113 * | −0.3700 * | 0.8392 * | 1 | |||||

| Operating Profit to Capital Employed Ratio | −0.1778 | −0.3653 * | 0.8828 * | 0.9210* | 1 | ||||

| Capacity Factor of Hydropower | −0.1698 | −0.0068 | 0.0158 | −0.0315 | 0.0163 | 1 | |||

| Capacity Factor of Thermal Power | 0.3313 * | 0.4481 * | −0.4884 * | −0.5387 * | −0.5004 * | 0.2975 * | 1 | ||

| Capacity Factor of Nuclear | −0.4287 * | −0.4532 * | 0.4207* | 0.4784 * | 0.4450 * | 0.2432 | −0.4840 * | 1 | |

| Capacity Factor of New Energy | −0.0814 | 0.2689 | −0.1819 | −0.1949 | −0.2114 | 0.2226 | 0.0851 | 0.1067 | 1 |

Note: * indicates the Pearson correlation coefficient, significant at the 95% confidence level.

Table A2.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on Management.

Table A2.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on Management.

| Component | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comp1 | 3.99214 | 0.4436 | 0.4436 |

| Comp2 | 1.52153 | 0.1691 | 0.6126 |

| Comp3 | 1.1245 | 0.1249 | 0.7376 |

| Comp4 | 0.928124 | 0.1031 | 0.8407 |

| Comp5 | 0.548401 | 0.0609 | 0.9016 |

| Comp6 | 0.377023 | 0.0419 | 0.9435 |

| Comp7 | 0.298325 | 0.0331 | 0.9767 |

| Comp8 | 0.154822 | 0.0172 | 0.9939 |

| Comp9 | 0.055137 | 0.0061 | 1 |

Table A3.

Load of the first three principal components on the original index of Management.

Table A3.

Load of the first three principal components on the original index of Management.

| Variable | Comp1 | Comp2 | Comp3 | Unexplained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asset Turnover Ratio | −0.2507 | −0.4213 | 0.4036 | 0.2957 |

| Equity Turnover Ratio | −0.3225 | −0.0965 | 0.4809 | 0.3107 |

| Value-Added Ratio | 0.434 | −0.1122 | 0.2974 | 0.1296 |

| Operating Cash Flow Ratio | 0.4476 | −0.1226 | 0.2731 | 0.09336 |

| Operating Profit to Capital Employed Ratio | 0.4376 | −0.1577 | 0.3688 | 0.04485 |

| Hydropower Facility Utilization Rate | −0.0013 | 0.5892 | 0.4082 | 0.2844 |

| Thermal Power Facility Utilization Rate | −0.3582 | 0.1009 | 0.3212 | 0.3561 |

| Nuclear Power Facility Utilization Rate | 0.3365 | 0.3782 | −0.0636 | 0.3259 |

| New Energy Facility Utilization Rate | −0.1069 | 0.5102 | 0.1815 | 0.5213 |

Table A4.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of solvency.

Table A4.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of solvency.

| Current Ratio | Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Operating Cash Flow to Current Liabilities Ratio | Debt Ratio | Fixed Asset Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | 1 | ||||

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | 0.4693 * | 1 | |||

| Operating Cash Flow to Current Liabilities Ratio | −0.3544 * | −0.5463 * | 1 | ||

| Debt Ratio | 0.4690 * | 0.9559 * | −0.5251 * | 1 | |

| Fixed Asset Ratio | 0.3975 * | 0.9520 * | −0.5130 * | 0.9961 * | 1 |

Note: * indicates the Pearson correlation coefficient, significant at the 95% confidence level.

Table A5.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on solvency.

Table A5.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on solvency.

| Component | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comp1 | 3.57855 | 0.7157 | 0.7157 |

| Comp2 | 0.743783 | 0.1488 | 0.8645 |

| Comp3 | 0.619403 | 0.1239 | 0.9883 |

| Comp4 | 0.0575075 | 0.0115 | 0.9998 |

| Comp5 | 0.000761701 | 0.0002 | 1 |

Table A6.

Load of the first two principal components on the original index of solvency.

Table A6.

Load of the first two principal components on the original index of solvency.

| Variable | Comp1 | Comp2 | Unexplained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | 0.3124 | −0.8747 | 0.08163 |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | 0.5085 | 0.1892 | 0.04803 |

| Operating Cash Flow to Current Liabilities Ratio | −0.3555 | 0.245 | 0.5032 |

| Debt Ratio | 0.5126 | 0.2162 | 0.02476 |

| Fixed Asset Ratio | 0.5046 | 0.3038 | 0.02006 |

Table A7.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Growth.

Table A7.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Growth.

| Total Capital Growth Rate | Revenue Growth Rate | Gross Profit Growth Rate | Operating Profit Growth Rate | Pre-Tax Profit Growth Rate | Net Profit Growth Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Capital Growth Rate | 1 | |||||

| Revenue Growth Rate | 0.195 | 1 | ||||

| Gross Profit Growth Rate | 0.1435 | 0.3842 * | 1 | |||

| Operating Profit Growth Rate | 0.0125 | 0.2114 | 0.0822 | 1 | ||

| Pre-Tax Profit Growth Rate | −0.0809 | −0.0621 | 0.01 | −0.3199 * | 1 | |

| Net Profit Growth Rate | −0.0903 | 0.0279 | 0.0231 | −0.0174 | 0.4246 * | 1 |

Note: * indicates the Pearson correlation coefficient, significant at the 95% confidence level.

Table A8.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Scale.

Table A8.

Correlation coefficient matrix between the variables of Scale.

| Total Capital Employed | Total Generation Capacity | Research and Development Expenses | Electricity Revenue | Hydropower Facility Capacity | Thermal Power Facility Capacity | Nuclear Power Facility Capacity | New Energy Facility Capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Capital Employed | 1 | |||||||

| Total Generation Capacity | 0.9896 * | 1 | ||||||

| Research and Development Expenses | 0.9033 * | 0.9072 * | 1 | |||||

| Electricity Revenue | 0.9472 * | 0.9448 * | 0.8215 * | 1 | ||||

| Hydropower Facility Capacity | 0.9264 * | 0.9449 * | 0.8649 * | 0.8802 * | 1 | |||

| Thermal Power Facility Capacity | 0.9662 * | 0.9843 * | 0.8571 * | 0.9409 * | 0.8964 * | 1 | ||

| Nuclear Power Facility Capacity | 0.9546 * | 0.9414 * | 0.9340 * | 0.8705 * | 0.9038 * | 0.8742 * | 1 | |

| New Energy Facility Capacity | 0.0063 | −0.038 | −0.0676 | 0.0174 | −0.127 | −0.0245 | −0.0279 | 1 |

Note: * indicates the Pearson correlation coefficient, significant at the 95% confidence level.

Table A9.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on Scale.

Table A9.

Eigenvalue and cumulative contribution rate of each component variance on Scale.

| Component | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comp1 | 6.5059 | 0.8132 | 0.8132 |

| Comp2 | 1.01451 | 0.1268 | 0.9401 |

| Comp3 | 0.234049 | 0.0293 | 0.9693 |

| Comp4 | 0.108098 | 0.0135 | 0.9828 |

| Comp5 | 0.0733184 | 0.0092 | 0.992 |

| Comp6 | 0.0557311 | 0.007 | 0.999 |

| Comp7 | 0.0083911 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Comp8 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Table A10.

Load of the first principal components on the original index of Scale.

Table A10.

Load of the first principal components on the original index of Scale.

| Variable | Comp1 | Unexplained |

|---|---|---|

| Total Capital Employed | 0.3886 | 0.01751 |

| Total Generation Capacity | 0.3902 | 0.009664 |

| Research and Development Expenses | 0.3652 | 0.1321 |

| Electricity Revenue | 0.3722 | 0.09881 |

| Hydropower Facility Capacity | 0.3731 | 0.09428 |

| Thermal Power Facility Capacity | 0.379 | 0.06551 |

| Nuclear Power Facility Capacity | 0.3764 | 0.07827 |

| New Energy Facility Capacity | −0.0178 | 0.9979 |

References

- Taniguchi, M. The Impact of Liberalization on the Production of Electricity in Japan. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 5, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibune, H. Regulatory Reform of Energy and Economic Growth in Japan. Int. J. Econ. Policy Stud. 2019, 13, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Le-Anh, T.; Nguyen, T.X.H. Factors Influencing Innovation Capability and Operational Performance: A Case Study of Power Generation Fields in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.H.; Karimi, A.; Tavana, M. An Integrated Green Supplier Selection Approach with Analytic Network Process and Improved Grey Relational Analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 159, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Niu, D. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Sustainable Development of Power Grid Enterprises Based on the Model of Fuzzy Group Ideal Point Method and Combination Weighting Method with Improved Group Order Relation Method and Entropy Weight Method. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J. Renewable Energy Product Competitiveness: Evidence from the United States, China and India. Energy 2022, 249, 123614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Ye, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Sun, J. A Hybrid MCDM Model for Evaluating the Market-Oriented Business Regulatory Risk of Power Grid Enterprises Based on the Bayesian Best-Worst Method and MARCOS Approach. Energies 2022, 15, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Song, W. Evaluating Technology Innovation Capabilities of Companies Based on Entropy- TOPSIS: The Case of Solar Cell Companies. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 23, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, K.; Jiang, Q. Assessing Energy Vulnerability and Its Impact on Carbon Emissions: A Global Case. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Yan, C.; Feng, Z.; Zhou, S. Evaluation and Dynamic Monitoring of Ecological Environment Quality in Mining Area Based on Improved CRSEI Index Model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; He, B.; Zhang, B.; Ren, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yun, P.; Mi, Y. Intraday Energy Management Strategy for Wind-Hydrogen Coupled Systems Based on Hybrid Electrolysers. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, 2403494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, M.; Gholizadeh, M.; Deymi-Dashtebayaz, M. The Optimization of a Low-Temperature Geothermal-Driven Combined Cooling and Power System: Thermoeconomic and Advanced Exergy Assessments. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Gaur, S.; Ohri, A. Analysing the Effectiveness of MCDM and Integrated Weighting Approaches in Groundwater Quality Index Development. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2024, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, E.; Hosseinali, F.; Najafi, M.M.; Sharifi, A. A GIS-Based Evaluation of Urban Livability Using Factor Analysis and a Combination of Environmental and Socio-Economic Indicators. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2024, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.A.; Junejo, F.; Amin, I. Optimizing Sustainable Machining for Magnesium Alloys: A Comparative Study of GRA and TOPSIS. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2308986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.; Behera, B. Geospatial Assessment of Ecological Vulnerability of Fragile Eastern Duars Forest Integrating GIS-Based AHP, CRITIC and AHP-TOPSIS Models. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2330529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimouratidis, A.I.; Pilavachi, P.A. Multicriteria Evaluation of Power Plants Impact on the Living Standard Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1074–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimouratidis, A.I.; Pilavachi, P.A. Technological, Economic and Sustainability Evaluation of Power Plants Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, C.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, G. Evaluation Research of Regional Power Grid Companies’ Operation Capacity Based on Entropy Weight Fuzzy Comprehensive Model. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 4626–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, P.; Guo, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, H. Operation Performance Evaluation of Power Grid Enterprise Using a Hybrid BWM-TOPSIS Method. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.S.; Zeng, S.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, T.K.; Huang, Q.S.; Zeng, S.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, T.K. Evaluation of Sustainable Development Capability of Electric Power Enterprises Based on Entropy Weight-COPARS. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, M.A.; Ayodele, T.R.; Ogunjuyigbe, A.S.O.; Popoola, O.M. Multi-Criteria Decision Based Waste to Energy Technology Selection Using Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS Technique: The Case Study of Lagos, Nigeria. Energy 2020, 201, 117675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, N. Evaluating the Performance of Thermal Power Enterprises Using Sustainability Balanced Scorecard, Fuzzy Delphic and Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision Making Approaches for Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talal, M.; Tan, M.L.P.; Pamucar, D.; Delen, D.; Pedrycz, W.; Simic, V. Evaluation and Benchmarking of Research-Based Microgrid Systems Using FWZIC-VIKOR Approach for Sustainable Energy Management. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 166, 112132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Li, Z. Suitability Evaluation Method for Preventive Maintenance of Asphalt Pavement Based on Interval-Entropy Weight-TOPSIS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 134098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Xue, J.; Qu, Y.; Shi, Y. Evaluation of China’s Digital Economy: A Case Study Using Entropy and TOPSIS. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 242, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, N.; Shen, Z. Evaluation of the Water Quality Monitoring Network Layout Based on Driving-Pressure-State-Response Framework and Entropy Weight TOPSIS Model: A Case Study of Liao River, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yi, Y. Distribution of Geothermal Resources in Eryuan County Based on Entropy Weight TOPSIS and AHP-TOPSIS Methods. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Shi, X.; Zhou, X.; Leng, S.; Huang, J.; Peng, S. Comprehensive Natural Resources Evaluation from Multi-Category Aggregation: A Case Study of Huanggang. Earth 2024, 36, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefe, İ.; Evci, S.; Kefe, İ. Data on the Financial Performance of Companies on BIST Sustainability 25 Index: An Entropy-Based TOPSIS Approach. Data Brief 2024, 57, 110959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wu, S. Performance Analysis of a Novel Movable Exhaust Ventilation System for Pollutant Removal in Industrial Environments. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, P.-D.; Nguyen, L.-T.; Tran, B.-Q. Assessing Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Performance of Global Electronics Industry: An Integrated MCDM Approach-Based Spherical Fuzzy Sets. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2297509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, C.O.; Diemuodeke, E.O.; Briggs, T.A.; Ojapah, M.M.; Okereke, C.; Okedu, K.E.; Kalam, A. Low/Zero Carbon Technology Diffusion and Mapping for Nigeria’s Decarbonization. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, 2317146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, F.; Kazemi, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Mishra, P. Prioritizing Industrial Wastes and Technologies for Bioenergy Production: Case Study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, F.; Equbal, A.; Khan, O.; Yahya, Z.; Alhodaib, A.; Parvez, M.; Ahmad, S. Assessment and Ranking of Different Vehicles Carbon Footprint: A Comparative Study Utilizing Entropy and TOPSIS Methodologies. Green Technol. Sustain. 2025, 3, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, R.; Gharizadeh Beiragh, R.; Soltanisehat, L.; Soltanzadeh, E.; Lund, P.D. Performance Evaluation of Complex Electricity Generation Systems: A Dynamic Network-Based Data Envelopment Analysis Approach. Energy Econ. 2020, 91, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Balanced Scorecard-Measures That Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review, January–February 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Green Balanced Scorecard: A Tool of Sustainable Information Systems for an Energy Efficient Business. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/16/18/6432 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Ou, Y.; Fu, Y.; Bian, X. A Novel Decision-Making System for Selecting Offshore Wind Turbines with PCA and D Numbers. Energy 2022, 258, 124818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Liang, X.; Xiao, C.; Wang, G. Integration of GIS, Improved Entropy and Improved Catastrophe Methods for Evaluating Suitable Locations for Well Drilling in Arid and Semi-Arid Plains. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Ravi, V. Supplier Selection in Resilient Supply Chains: A Grey Relational Analysis Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeqiraj, V.; Sohag, K.; Soytas, U. Stock Market Development and Low-Carbon Economy: The Role of Innovation and Renewable Energy. Energy Econ. 2020, 91, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Sun, C.Z.; Zou, W. Coupling Relation Analysis between Water Poverty and Economic Poverty. China Soft Sci. 2011, 12, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, R.; Almutairi, S.; Bansal, P. Emerging Energy Economics and Policy Research Priorities for Enabling the Electric Vehicle Sector. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, P.; Cai, W.; Shi, Z.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, W.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Identifying Administrative Villages with an Urgent Demand for Rural Domestic Sewage Treatment at the County Level: Decision Making from China Wisdom. Sustainability 2025, 17, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).