Abstract

This study investigates emergency response strategies for sudden pollution incidents in long-distance water diversion tunnels. The tunnel section of the Yin Chao Ji Liao Project in Inner Mongolia is used as a case study. A one-dimensional hydrodynamic water quality model was developed in Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) to analyze pollutant transport characteristics in the tunnel under various operating conditions. Based on the actual engineering conditions, control scenarios with multiple flow rates and multiple gate combinations were set up. Emergency control strategies for sudden pollution events were developed to address extreme pollution scenarios. The feasibility of scheduling gate operations according to pollutant transport response time for effective pollution mitigation was evaluated. On this basis, an expression for calculating gate-operation timings for emergency pollution control was derived. The results indicate that the peak concentration in the tunnel shows a decreasing trend as the flow rate increases, and the change process shows a stage-by-stage characteristic. Accounting for the response time of water discharge can improve pollution disposal efficiency by 4.34–52.14%. The efficiency gains become increasingly pronounced at higher flow rates, indicating that this strategy can effectively enhance water discharge efficiency. Installing water quality monitoring instruments near the drainage gate section helps improve the precision of regulation and effectively enhances the timeliness and accuracy of operations, and provides a theoretical reference for on-site emergency regulation and control.

1. Introduction

As a critical measure to optimize water-resource allocation and alleviate regional water scarcity, long-distance water diversion projects play a pivotal role in ensuring local water-supply security and supporting sustainable socioeconomic development [,,]. However, because of the long transmission distance and the extensive water-receiving area, a sudden water-pollution incident would not only compromise water quality but could also precipitate widespread supply interruptions or excessive water releases if improperly managed, thereby inflicting severe impacts on residents’ livelihoods and agricultural production and potentially undermining the region’s sustainable economic and social development [,,,,]. Therefore, analyzing the migration patterns of pollutants during water transfer and formulating scientific and efficient emergency control strategies are of great significance for enhancing the risk prevention and control capabilities of long-distance water diversion projects [,,].

At present, based on the successful operation of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project and many other water transfer projects, research on the transfer and diffusion of pollutants in sudden water pollution incidents in water transfer projects has received much attention [,,], and fruitful research results have been achieved [,,]. Benziada et al. [] employed phenol as a tracer and combined online sampling with photometric analysis to investigate the evolution of lateral and vertical concentration profiles of pollutant plumes under varying flow rates and boundary-roughness conditions in an isosceles-trapezoidal open-tunnel model. They revealed pollutant transport and dispersion characteristics within the tunnel, providing an experimental basis for understanding pollutant movement mechanisms in conduits and for informing pollution-control strategies []. Tang et al. [] developed a one-dimensional hydrodynamic and water-quality model for the Beijing–Shijiazhuang section of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. They simulated pollutant transport and dispersion under varying contamination levels, source locations, and pollutant types, and qualitatively assessed the influence of these parameters on peak pollutant concentrations []. Qiao et al. [] developed a real-time emergency decision-support system based on the analytic hierarchy process and gray fixed-weight clustering. They simulated gate operating timings and velocities to systematically analyze pollutant migration distances, spatiotemporal concentration distributions, and dilution characteristics in gate-controlled long-distance water-conveyance tunnels []. Existing research mainly focuses on constructing a sudden water pollution model under normal water supply conditions for a single water supply tunnel, and analyzing the pollution transfer law through numerical simulation. Considering that the water supply project has little change along the same section and the hydrodynamic conditions are stable during the water supply period, it is possible to obtain relatively accurate results by conducting research on the sudden pollutant transfer and diffusion laws under normal water supply and gate regulation based on numerical models.

In addition, in order to effectively respond to sudden water pollution incidents, many scholars have conducted relevant research on emergency control strategies of water pollution [,,,]. For sudden water pollution incidents in a single water supply tunnel, its prevention and control mainly focus on limiting the spread of water pollution. Li et al. [] constructed an emergency decision-making model that integrates case-based reasoning and prospect theory for the possible sudden water pollution incidents in the middle route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. The model retrieves similar historical cases and combines the decision-makers’ psychological preferences for risk and loss to achieve intelligent screening and optimization of emergency control plans in stages []. Xue et al. [] constructed a hydrodynamic water quality model for the open tunnel of the middle route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project based on the coupling of the one-dimensional Saint-Venant equation and the convection-diffusion equation. They systematically evaluated the effects of emergency sluice closure control strategies on pollutant migration, tunnel emptying rate, and water level fluctuations under different gate arrangements during sudden pollution accidents, providing decision support for rapid response and safe scheduling of water transfer tunnels []. Xu et al. [] proposed a real-time and rapid emergency control model for sudden water pollution accidents in long-distance water diversion projects. The model can quickly predict key control parameters such as gate closing time and pollution impact range by classifying pollutant characteristics, thus achieving timely response and effective control of accidents []. In the event of a sudden water pollution incident, if the gate control method cannot be quickly and effectively determined, the control plan will deviate, delaying the rescue opportunity. Many scholars have also established some emergency control decision-making models for sudden water pollution incidents [,].

However, although predecessors have conducted extensive research on the transport and diffusion laws of pollutants in water transfer projects, there is less research on long-distance closed water transfer tunnel projects. In addition, compared with open water transfer tunnels, which can be used to purify water quality by externally injecting specific substances, closed water transfer tunnels can only isolate polluted water flows through gate regulation, thereby achieving pollution emergency regulation. Therefore, it is necessary to study the emergency control measures for closed water transfer tunnels to deal with sudden water pollution.

In summary, sudden pollution incidents in long-distance water diversion projects pose a significant challenge to their stable operation. Although numerous studies have been conducted on the mechanisms of pollution diffusion and emergency control methods, most have focused on open-tunnel water diversion projects, and research on sudden pollution control in long-distance closed water diversion tunnels remains limited. In addition, when the water source in the receiving area is single, the water supply guarantee capacity of the water transfer project has an important impact on the sustainable development of the regional economy [,,]. Moreover, the operation timing of the gate will significantly affect the actual water supply. Therefore, it is necessary to accurately regulate the gate to maximize the water supply efficiency while achieving effective treatment of sudden pollution. However, existing studies have rarely considered the impact of the gate regulation timing on the emergency regulation effect.

This paper investigates emergency control strategies for sudden pollution incidents, using the water diversion tunnel of the Yin Chao Ji Liao Project as a case study. Utilizing the SWMM, we simulated water quality variations within the tunnel, analyzed pollutant transport patterns under different flow rates, developed emergency control strategies based on these characteristics, and derived empirical formulas for gate operating times under varying water diversion conditions. This approach aims to provide a theoretical basis and technical support for the emergency control of sudden pollution incidents in the project.

2. Method

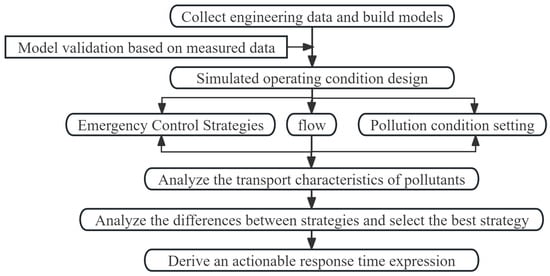

In order to explain the simulation process of this study in detail and to help better understand the work done by the institute, the research route description is given below, and the process introduction of the simulation operation of this study is given in the form of a flow chart, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of simulation operation process.

- Collect basic data of the project, including length, cross-sectional dimensions, roughness, elevation, etc. Use modeling software to build a numerical model and verify the reliability of the model based on the actual operation data of the project.

- The operating condition design is carried out according to the actual project conditions (operating flow, control gate position and opening and closing method, and pollutant type).

- Calculate the design conditions, analyze the transport characteristics of pollutants based on the model results, design a control strategy based on the hydraulic response time, compare the disposal efficiency with the conventional control strategy, and find the optimal strategy.

- Organize the data through simulation results and fit the hydraulic response time formula for flow.

2.1. Study Area

The Yin Chao Ji Liao Project is among the 172 flagship water conservation and supply initiatives designated by the State Council during China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, serving as a pivotal component of the national water network. It stands as the largest water conservancy project in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The project diverts water from the Chaoer River—a tributary of the Nenjiang River—to Tongliao City in the lower reaches of the Xiliao River, supplying eight county-level cities and ten industrial parks along its route. The designed water supply flow is 15.48 m3/s, with a multi-year average transfer volume of 4.54 × 108 m3. This project improves agricultural irrigation conditions in the lower reaches of the Chaoer River, mitigates over-exploitation of groundwater in Tongliao City, and plays a significant role in promoting the sustainable economic and social development of eastern Inner Mongolia. It also enhances production and living conditions in ethnic minority areas and contributes to the restoration of the regional ecological environment.

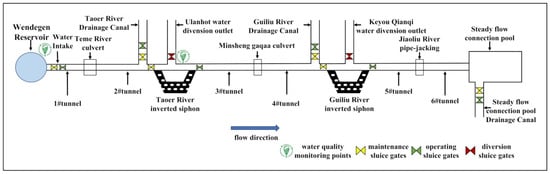

The project consists of two parts: the water source project and the water transmission project. The water source project is the Wendegen Reservoir, and the water transmission project is approximately 391.036 km long, consisting of a 183.590 km tunnel section and a 207.446 km pipeline section. The tunnel section starts from the water intake and consists of 1#tunnel, Teme River culvert, 2#tunnel, Taoer River inverted siphon, 3#tunnel, Minsheng Gaqaa culvert, 4#tunnel, Guiliu River inverted siphon, 5#tunnel, Jiaoliu River pipe-jacking, and 6#tunnel. The end of the tunnel section is connected to the pipeline section through a steady flow connection pool. There are two water diversion outlets, namely the Ulanhot water diversion outlet and the Keyou Qianqi water diversion outlet, with designed water diversion flow rates of 2.92 m3/s and 0.38 m3/s, respectively, located at two inverted siphons. The project adopts a closed water supply throughout the project, with only water discharge chambers installed at the Taoer River inverted siphon, Guiliu River inverted siphon and steady flow connection pool. The water discharge gates are all closed under normal circumstances and are only opened to discharge water in emergencies and during project maintenance. The maximum water discharge capacity at each location is 18.58 m3/s, 7.08 m3/s, and 14.61 m3/s, respectively. To monitor the project’s water quality, two water quality monitoring points are located in the tunnel section: the water intake and the Ulanhot water diversion outlet. When water quality is detected to be contaminated, wastewater can be discharged through drainage structures. The locations of the structures and water quality monitoring points along the tunnel are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the locations of buildings and water quality monitoring points along the tunnel.

2.2. Model Building

2.2.1. Introduction to the SWMM

SWMM, short for Storm Water Management Model, was developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and is an open-source tool for simulating rainfall runoff, drainage system hydraulic processes, and water quality changes in urban areas [,]. This study used SWMM version 5.2., the simulation only involves simple tunnel runoff and water quality evolution. The core equations of its hydraulic and water quality modules are described as follows []:

Hydraulic Simulation Equations

SWMM software is used to simulate hydraulics and water quality when conveying water through a tunnel using unpressurized gravity flow. Water movement includes infiltration, evaporation, and runoff. Runoff outflow is calculated using the Manning equation. Outflow enters the junction. The Manning equation expresses the relationship between flow rate (), cross-sectional area (), hydraulic radius (), and slope ():

where is the Manning roughness coefficient, which ranges from 0.012 to 0.017 depending on the construction section and cross-section shape.

Based on the laws of conservation of mass and momentum, we can derive the continuity equation and equation of motion for the system flow, known as the Saint-Venant equations:

Continuity equation:

Momentum equation:

where is the distance; is the time; is the flow cross-sectional area at ; is the flow rate at ; is the hydraulic head of water in the conduit at ; is the friction slope; and is the acceleration of gravity.

A pressurized condition will be formed at the bottom pipe of the inverted siphon. For circular pressurized pipes, the Hazen–Williams or Darcy–Weisbach formula is used instead of the Manning formula:

Hazen–Williams:

Darcy–Weisbach:

where is the Hazen–Williams coefficient, a cross-sectional parameter that varies with the inverse of the roughness coefficient. For turbulent flow, the Colebrook–White formula is used to determine the wall roughness height and the Reynolds number of the fluid.

Water Quality Simulation Equations

For a storage node, assuming the storage volume is completely mixed, the uniform concentration within the node is governed by the mass conservation equation, which is

where is the storage volume at the node, is the flow rate at the end of pipe segment entering node , is the flow rate at the beginning of pipe segment leaving node , is the mass flow rate of any external source entering node , and is the reaction rate term, which in this study is the attenuation term. See below for its values.

For conduits, these are represented as completely mixed reactors connected to each other at junctions or completely mixed storage nodes. The spatial variation in concentration along the length of the conduit is calculated using the following equation:

where is the volume of the reactor, is the concentration in the reactor, is the concentration of any influent to the reactor, is the volumetric flow rate of that influent, is the volumetric flow rate out of the reactor, and is a function that determines the loss rate due to the reaction. The result is obtained internally by giving the r value.

Based on the hydraulic module of SWMM and combined with actual engineering monitoring data, the hydraulic processes of the model can be simulated and verified, as detailed in Section 2.2.3. As for the verification of the water quality module, since there is currently no actual monitoring data for the water quality process, according to the one-dimensional advection-dispersion equation (Equation (8)), the diffusion process of pollutants can be verified through the hydrodynamic model. The decay coefficient, based on relevant literature, indicates that the decay coefficient for ammonia nitrogen pollutants ranges from 0.071 to 0.350 per day, and that the corresponding decay coefficient decreases with decreasing temperature []. Considering that the project is situated in the cold region of northern China, a decay coefficient of 0.10 day−1 was adopted for this study.

where is the pollutant concentration, is the longitudinal diffusion coefficient, is the decay coefficient, is the pollutant concentration generated by point source pollution, and is the input flow rate of point source pollution.

2.2.2. Model Abstraction

A one-dimensional hydrodynamic water quality model was constructed using SWMM. The model domain’s upstream boundary was the project’s water intake, and its downstream boundary was the steady flow connection pool. 133 sections, including the connections of each tunnel section, gradient sections, inverted siphon inlets and outlets, were selected as nodes to generalize the water diversion tunnel.

The parameters set for each node include the node location coordinates, bottom elevation, maximum water depth, etc.; the parameters set for the connecting pipe section include the cross-sectional shape, roughness, inlet and outlet loss coefficients, etc.; the orifice is used to simulate the gate and the gate operating process in the actual project is simulated by setting control rules; the Simulation Options settings include simulation time of 10 days, calculation Time Steps of 1 min, Reporting Step of 1 min, Horton is selected as the Infiltration Model, Dynamic Wave is selected as the Routing Model, Flow Routing and water Quality are selected in the Process Models, and Allow Ponding are selected in the Routing Options.

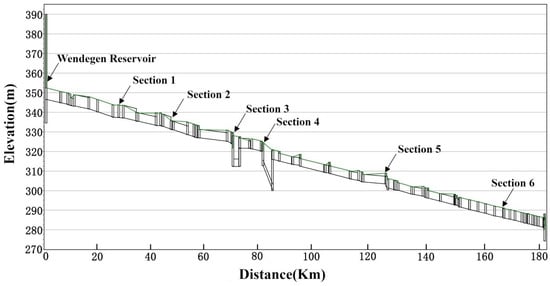

The abstracted model and key sections are shown in Figure 3. After parameter adjustment, the maximum Continuity Error in the Flow Routing Continuity in the model simulation results is 0.004%, and the maximum Continuity Error in the Quality Routing Continuity is 1.265%, which meets the calculation requirements.

Figure 3.

Overview of the Tunnel Section Model and Diagrams of Key Sections. (The "Section X" refers to the tunnel section).

2.2.3. Model Results Verification

To evaluate the reliability of the model constructed in this paper and ensure that the model simulation results accurately reflect the engineering scheduling and operation process, six automated monitoring points within the tunnel were selected, and analog data were compared with observed data during the engineering flushing process. The results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of measured data and SWMM analog data.

The model accurately captures the hydraulic response time of each key section, and the subsequent water level rise process is consistent with the observed changes. The basic fitting indicators for data analysis include R2 (coefficient of determination), RMSE (root mean square error), MAE (mean absolute error), etc. Root mean square error (RMSE) is used as the accuracy verification indicator []. The RMSE values of each section are between 0.014 and 0.042, indicating that the SWMM can better reflect the hydraulic characteristics in the tunnel and can be used to analyze the changes in water quality during water conveyance.

2.3. Design of Operating Conditions

2.3.1. Design of Water Diversion Flow Rate

According to the engineering design report and the technical specifications for dispatching and operation, without considering the water supply conditions of the project branch line, the maximum water diversion flow rate that the tunnel can withstand is 12.18 m3/s. This study uses a gradient interval of 1 m3/s and sets a total of 12 water diversion flow rates ranging from 1 to 12 m3/s, covering key node values such as the tunnel flushing flow during the trial operation phase (3 m3/s) and the maximum flow during the trial operation (12 m3/s), providing data support for revealing the impact of flow changes on the migration and diffusion of pollutants and the effectiveness of emergency regulation.

2.3.2. Selection of Pollution Sources and Pollutant Parameters

Typically, common pollutants in sudden pollution incidents in long-distance water transfer projects include: soluble inorganic salts (such as nitrates and chlorides), nutrients (ammonia nitrogen and phosphorus), organic matter (petroleum hydrocarbons, pesticides, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), heavy metals (lead, cadmium, arsenic, etc.), suspended solids, and biomacromolecules. Different pollutant types are closely related to the environmental and geological conditions of the project. Because the project case in this study is located in a high-latitude and cold region, there are unfavorable geological sections along the water transfer line, such as seasonal permafrost, strong fracture zones, and highly permeable layers. Some tunnel sections experience groundwater infiltration. Therefore, the intrusion of external water carrying pollutants is one of the factors that need to be considered when affecting the water quality safety of the project water transfer. Considering that the surface of the tunnel is often covered by villages, farmland, and farms, this study uses the infiltration of groundwater containing ammonia nitrogen pollutants as a sudden pollution incident.

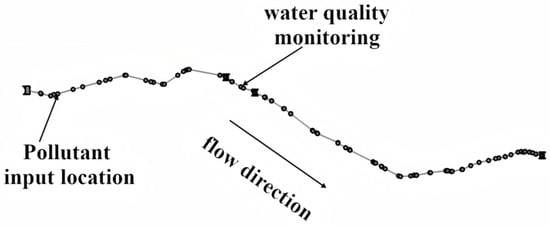

To investigate the pollutant transport characteristics during the entire tunnel section, and considering the project’s actual conditions and the increased likelihood of external water infiltration due to changes in tunnel cross-sectional shape and the proximity of different construction sections, a groundwater infiltration event was assumed to begin at the 72nd hour of simulation at the entrance of tunnel Section 2, continuing for 48 h. The maximum contamination concentration occurred at the 96th hour, with a linear progression from that hour onward. Furthermore, to establish a universal pattern for this type of pollution input event, two pollution input intensities were set, with maximum concentrations of 100 mg/L and 200 mg/L, respectively, and a tunnel infiltration rate of 0.1 m3/s. The pollutant input locations and water quality monitoring locations are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of water quality monitoring location, pollutant input location.

2.3.3. Design of Simulated Operating Conditions

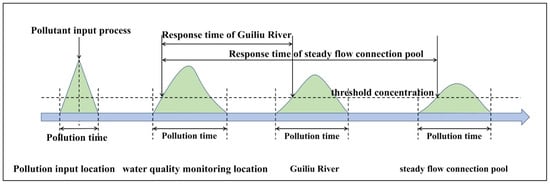

The water supply target of this project is urban production and domestic water, with Class III water as the judgment standard. According to the basic item limits of the “Environmental Quality Standards for surface water” [], the ammonia nitrogen concentration limit of Class III water is 1.0 mg/L. Therefore, 1.0 mg/L is set as the threshold concentration, and the moment when the ammonia nitrogen concentration at the water quality monitoring point reaches the threshold concentration is taken as the start time of the reaction. The moment when the ammonia nitrogen concentration at the inlet of the Guiliu River and the inlet of the steady flow connection pool reaches the threshold concentration is recorded. This period of time is used as the hydraulic response time to adjust the inlet gate and the water discharge gate of the inverted siphon of the Guiliu River and the steady flow connection pool. The response time is shown in Figure 6. In addition, this study performed gate operations based on hydraulic response time, with the goal of achieving the fastest pollution disposal through the fastest gate response. Therefore, the principle of all gate operations in the working conditions is to complete the opening and closing operations in the shortest time while ensuring engineering safety.

Figure 6.

Diagram of Response Time.

Based on the maximum discharge capacity and location of the drainage structures in the tunnel and the response time concept defined in this study, five gate control strategies were designed (see Table 1). Taking into account the 12 water flow rates mentioned above, a total of 36 simulation operating conditions were obtained. Considering that there are many working conditions and they are difficult to describe simply, this study uses working condition vectors to represent them. The definition of the operating condition vector is shown in Formula (9), and the simulated operating conditions details are shown in Table 1.

where represents the simulated operating condition vector, represents the water flow rate, and represents the gate control strategy.

Table 1.

Detailed Description of Simulation Operating Conditions.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Characteristics of Pollutant Concentration Transport in Open Tunnel Flow

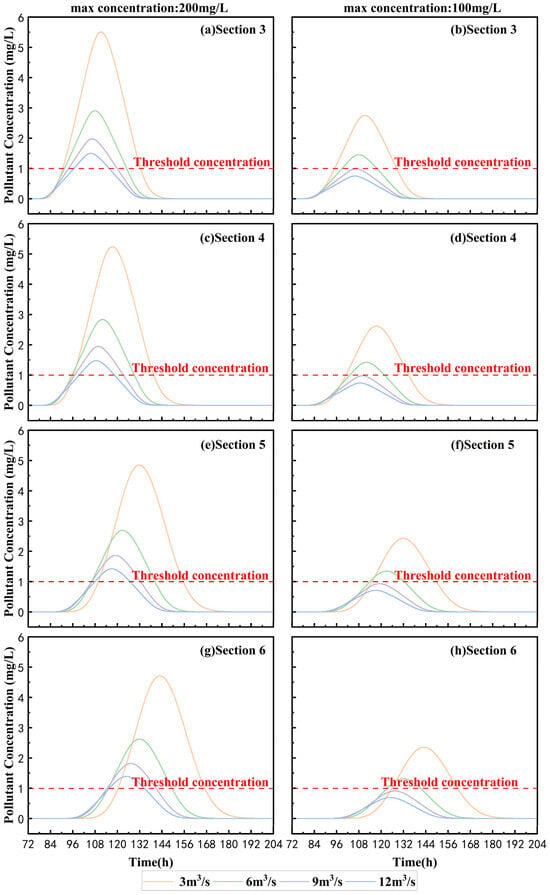

Four typical flow conditions of 3 m3/s, 6 m3/s, 9 m3/s, and 12 m3/s were selected to analyze the pollutant transport characteristics, providing a reference for the subsequent formulation of emergency pollution control strategies.

Figure 7 shows the concentration changes in pollutants in Sections 3–6 under four typical flow conditions. The results show that when only the maximum pollutant input concentration is changed, and the pollution input changes in the same way, the pollutant concentration changes in this case show the same pattern, with only the concentration values varying. Therefore, the emergency control strategy research is only conducted for a single pollution input, and the results can be extended to a class of situations that meet the requirements of this pollution input. To avoid duplication of work, the analysis, control strategy design, and gate emergency control response time pattern are only conducted for the operating condition with a maximum input concentration of 200 mg/L.

Figure 7.

Pollutant Concentration Changes at Key Sections under Four Typical Flow Conditions.

In the same section, the peak pollutant concentration is higher at low flow rates, the pollution exceeds the threshold time is longer, and the dilution effect is enhanced as the amount of water flowing increases during the flow rate growth. The pollutant concentration and the time exceeding the threshold value decrease significantly, and this downward trend becomes smaller as the flow rate increases. Taking Section 3 as an example, the peak concentrations at these four flow rates are 5.51 mg/L, 2.90 mg/L, 1.98 mg/L, and 1.50 mg/L, respectively, and the pollutant concentration exceeds the threshold time is 41.93 h, 33.45 h, 26.18 h, and 18.97 h. When the flow rate is 3 m3/s, the peak concentrations of each section are 5.51 mg/L, 5.24 mg/L, 4.85 mg/L, and 4.71 mg/L, respectively. The duration of pollutant concentration exceeding the threshold value is 41.93 h, 43.25 h, 45.63 h, and 46.68 h. At this time, as the water flows backward, due to the dilution effect, the peak concentration of pollutants shows a decreasing trend as the section moves backward, but the duration of pollution increases. The peak concentration moment at a small flow rate is significantly shifted backward compared to that at a large flow rate, indicating that the migration speed of pollutants is slower at a small flow rate, and there is a longer response time to ensure water supply. The data records of peak concentration, exceeding threshold concentration time and reaching threshold concentration time at the four key sections are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data records at four key sections.

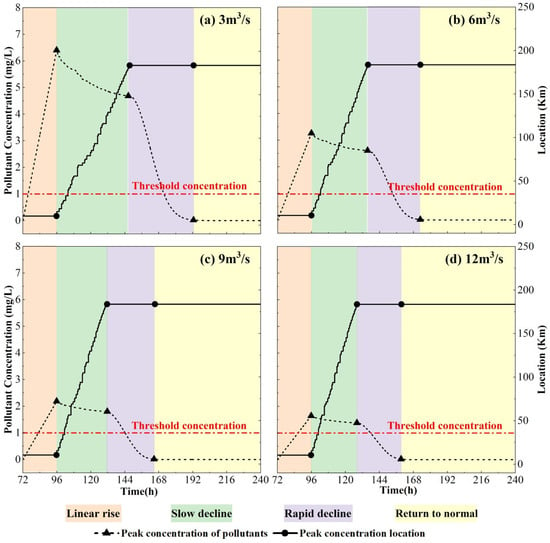

Figure 8 shows the peak concentration change curve of pollutants in the tunnel and the corresponding appearance position curve. Under different working conditions, the peak concentration change process shows the same change trend, which can be divided into four stages as a whole: linear rise, slow decline, rapid decline and return to normal. The linear rising stage corresponds to the rising process of the pollutant input process. Combined with the pollutant appearance position curve, the concentration change process during this period is the concentration change process at the pollutant input point over time. Since it has not yet been diluted during the transport process, it shows a linear rising feature and reaches the maximum value at the 96th hour. The slow decline stage corresponds to the peak concentration transfer process in the tunnel. At this time, the peak concentration starts from the input point and gradually moves downstream to the steady flow connection pool. The concentration drop is mainly affected by the dilution effect, and the smaller the flow rate, the more obvious the dilution effect. This process is consistent with the decrease in the peak concentration as the cross-section position moves backward in the curve in Figure 7. During the rapid decline stage, the peak concentration has reached the steady flow connection pool. The curve change process is the concentration change process at the steady flow connection pool. The subsequent peak concentrations all appear at the steady flow connection pool (183 km), indicating that this curve is the decline process curve after the pollutant concentration at the steady flow connection pool section reaches its peak. Due to the influence of dilution during the transport process, the decline process at this time is no longer a linear change, but decreases from slow to fast to zero in the form of a parabola. After that, the tunnel returns to normal.

Figure 8.

Peak concentration of pollutants and their locations.

3.2. Analysis of Pollution Treatment Effects of Different Control Strategies

According to the analysis results in Figure 7, the concentration peak moment at low flow rates is significantly shifted backward compared to that at high flow rates, indicating that pollutant migration is slower at low flow rates, and there is a longer response time to ensure water supply. However, since the pollution lasts longer, it will lead to a longer water abandonment time, and it cannot be guaranteed that less water will be abandoned at low flow rates. Moreover, as the flow rate increases, the time that the pollutant concentration exceeds the threshold concentration decreases, which may lead to a decrease in the concentration of pollutants exiting at large flows. Therefore, it is necessary to quantify the amount of discharged water and the quality of removed pollutants under different working conditions in order to analyze their effects under different control strategies.

According to the different water withdrawal time and removed pollutant quality under different Operating Conditions, the abandoned water volume and exit pollutant quality are compared and analyzed, and the minimum discharged water volume and the maximum removed pollutant quality are used as reference indicators for selecting the control strategy.

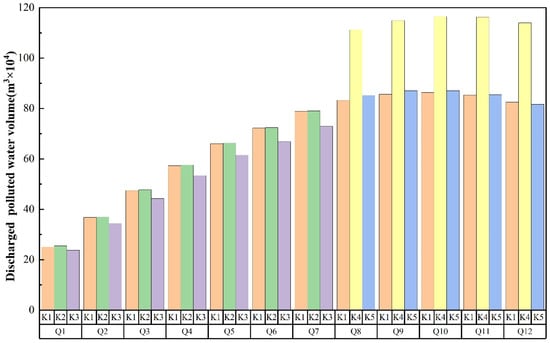

Figure 9 shows the amount of water discharged under different flow rates and control strategies. Under different flow rates, when the intake flow does not exceed the discharge limit of the Guiliu river (7.08 m3/s), the amount of water discharged under the same control strategy increases as the flow rate gradually increases, reaching a maximum at 7 m3/s, with the amounts of water discharged being 78.91 × 104 m3, 79.03 × 104 m3, and 72.89 × 104 m3, respectively. This is because water is only discharged through the drainage tunnel of the Guiliu River at this time, and its maximum flow capacity has not yet been reached. Therefore, the amount of water discharged is only affected by the overflow flow rate. When the flow exceeds the Guiliu River discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), the amount of water discharged under the same control strategy first increases and then decreases as the flow increases, reaching the maximum amount of water discharged at 10 flow rates. The maximum values under different strategies are 86.3 × 104 m3, 116.46 × 104 m3, and 87.05 × 104 m3, respectively. Because the flow has exceeded the Guiliu River discharge limit at this time, the water flow is naturally diverted when passing through the Guiliu River. The amount of water discharged is affected by both the overflow flow and the diversion coefficient at the Guiliu River.

Figure 9.

Comparison of water discharged under different operating conditions and flow rates.

Under the same flow rate, when the water intake flow does not exceed the Guiliu River’s water discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), the water discharged volume of is significantly smaller than that of and . The maximum difference occurs at 7 m3/s, which is 6.13 × 104 m3. The water discharged volume of and is basically the same because performs gate regulation based on the response time, ensuring a shorter water abandonment time. Although and have different withdrawal locations, their withdrawal time and flow rate are basically the same, so the water discharged volume is basically the same.

After exceeding the Guiliu River’s water discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), the water discharge of and is basically the same, while the water discharge of is abnormally higher than the former two. The maximum difference occurs at 7 m3/s, which is 32.35 × 104 m3.

Although the control strategies of and are different, the water withdrawal time of the Guiliu River and the steady flow connection pool in does not overlap. Therefore, the overall water withdrawal time can be simply regarded as the superposition of the two water withdrawal time periods. Without considering the weak influence caused by transport and diffusion, this period is basically the time when the pollutant concentration exceeds the threshold concentration, which leads to the water discharge amount under the two working conditions being basically the same, while only considers safety factors and opens the water withdrawal gate between the Guiliu River and the steady flow connection pool too early, resulting in a significant increase in the water discharge amount.

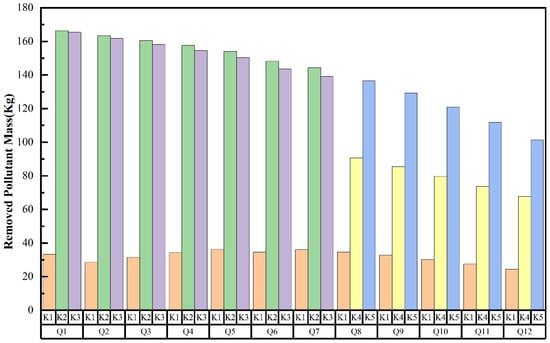

Figure 10 shows the removed pollutant mass under different flow rates and control strategies. Under the same strategy at different flow rates, except for , the removed pollutant mass decreases with increasing flow rate. After exceeding the Guiliu River discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), the rate of decrease increases slightly. This is because as flow rate increases, the time for pollutant concentration to exceed the threshold concentration gradually decreases. The increased flow rate leads to an enhanced dilution effect, which delays the time it takes for the monitored concentration to reach the threshold, resulting in a reduction in drainage time and removal of pollutant mass. As the flow rate increases, the change in pollutant mass of has no obvious pattern and is far less than other control strategies. This is because this strategy only considers safety from a safety perspective, without considering the impact of response time and pollutant transfer time. In addition, the time it takes for pollutants with different flow rates to reach the steady flow connection pool is different, resulting in poor pollutant withdrawal effect.

Figure 10.

Comparison of removed pollutant mass under different operating conditions and flow rates.

Under different strategies with the same flow rate, when the water intake flow does not exceed the Guiliu River discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), the mass of pollutants discharged from is the largest, slightly higher than and much higher than . The maximum difference can reach 1330.26 kg. Although does not take response time into account, the water quality monitoring point is very close to the Guiliu River discharge gate. From the perspective of the discharge pollutant quality, the response time has little impact. In this case, the discharge produces a better effect. When the water discharge limit of Guiliu River is exceeded (7.08 m3/s), discharges the most pollutants, followed by , and discharges the least. The maximum difference can reach 1017.77 kg. This is because takes into account the pollutant transfer factor, while and only consider safety factors, resulting in the water withdrawal period not coinciding with the peak pollutant concentration period, and the removed pollutant mass is very small.

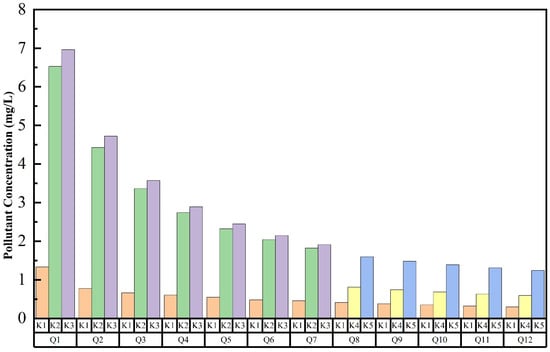

Taking the two indicators of discharged water volume and removed pollutant quality into consideration simultaneously, the control effect under different working conditions is analyzed by calculating the ratio of removed pollutant quality to discharged water volume. According to the results shown in Figure 11, under different flow rates, as the flow rate at the water intake increases, the average concentration of pollutants contained in the discharged water gradually decreases, and the overall efficiency is significantly reduced. This is because the increase in flow rate is accompanied by an enhanced dilution effect, and the water quality monitoring point detects the threshold concentration later. Combined with the pollutant concentration change process in Figure 6, the duration of exceeding the threshold concentration is significantly shortened under large flow rates. The simultaneous influence of the two leads to a gradual decrease in the quality of the removed pollutants.

Figure 11.

Comparison of pollutant concentrations in discharged water.

Under the same flow rate, when the water intake flow does not exceed the Guiliu River discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), taking 1 m3/s as an example, the highest and lowest comprehensive efficiencies are 6.96 mg/L and 1.33 mg/L, respectively. The efficiency difference caused by different strategies can reach 5.63 mg/L. In this case, the selection of (i.e., considering the hydraulic response time and giving priority to discharge through the Guiliu River) has the best effect; its efficiency can be increased by 4.34–6.21%. When the water discharge limit of the Guiliu River is exceeded (7.08 m3/s), taking 8 m3/s as an example, the highest and lowest comprehensive efficiencies are 1.60 mg/L and 0.42 mg/L, respectively.mg/L respectively. The efficiency difference caused by different strategies can reach 1.18 mg/L. At this time, the best effect is achieved by selecting (i.e., considering the hydraulic response time and withdrawing water in steps through the Guiliu River and the steady flow connection pool). Its efficiency can be increased by 49.12–52.14%. With the increase in flowincrease of flow, its treatment efficiency gradually improves. After the water intake flow exceeds the limit of Guiliu River, the efficiency of the strategy is more obvious. Among the most effective control strategies, the lowest pollutant concentration in the discharged water was 1.24 mg/L, and the highest was 6.96 mg/L, both higher than the threshold concentration, indicating that the response time considered in this study can effectively improve the water withdrawal efficiency.

3.3. Response Time Law of Gate Emergency Control

In order to facilitate the guidance of on-site personnel to accurately control the gates and effectively respond to sudden pollution, this section intends to apply the calculation results of the above model to derive the response relationship between the gate adjustment time and the water flow rate. After regression analysis, the response relationship between the adjustment time of the Guiliu River discharge gate and the steady flow connection pool discharge gate and the water flow rate is shown in Equations (10) and (11). The formula fitting errors are shown in Table 3.

where is the response time (min) for the pollutant concentration to reach the Guiliu River from the water quality monitoring point; is the response time (h) for the pollutant concentration to reach the steady flow connection pool from the water quality monitoring point; and is the flow rate at the water intake (m3·s−1).

Table 3.

Absolute error record of formula results.

Compared with the simulation calculation results, the error range of the response time of the Guiliu River discharge gate is 0.11–2.65 min, and the error range of the response time of the steady flow connection pool discharge gate is 0.48–0.82 h. The error results are small and within a reasonable range. The accuracy of the fitting formulas was verified using indicators such as R2, RMSE, and MAE. The values of the three indicators for formula (9) were 0.998, 1.288, and 0.999, respectively; and the values of the three indicators for formula (10) were 0.988, 0.705, and 0.694, respectively. The R2 of both formulas was very close to 1, and the values of RMSE and MAE indicated that the deviation was small, indicating that the fitting formulas were highly accurate.

To further evaluate the applicability of the formula under different flow rates, this study selected four flow conditions of 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.18 m3/s to simulate and verify the response time. The simulation results are shown in Table 4. The results show that the errors are all within the error range of the fitting formula. The R2, RMSE and MAE indicators are used to verify the fitting accuracy of the formula. The three indicator values of formula (9) are 0.998, 0.808 and 0.56, respectively; the three indicator values of formula (10) are 0.977, 0.731 and 0.73, respectively, proving that the formula is suitable for calculating response time under any flow rate condition between 0 and 12.18 m3/s. This formula can assist on-site personnel in achieving precise gate control and ensuring water quality safety.

Table 4.

Verify the absolute error record of the flow.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Factors Affecting Peak Concentration During Pollutant Transport

The main factors influencing peak pollutant concentrations vary at different water flow rates. When the flow rate is low, the water depth and velocity in the tunnel are shallow, prolonging the contact time between pollutants and the water. Initial input concentration becomes the dominant factor, and weak water dynamics hinder effective dilution and transport, leading to localized accumulation of pollutants and resulting in high concentrations. Under high flow conditions, however, the flow rate increases significantly, turbulence intensifies, and pollutant transport accelerates, which can promote rapid diffusion of pollutants. At this stage, the flow rate becomes the primary factor determining the peak concentration. Overall, under low-flow conditions, pollutant transport is primarily governed by the pollutant input concentration, whereas at high flow rates, dilution and dispersion mechanisms predominate.

4.2. Enlightenment from Emergency Control of Sudden Pollution in Water Diversion Projects

This study uses data from a water quality monitoring point in the water diversion tunnel to make early warning judgments and regulate different gates downstream based on the pollutant transfer time, thereby achieving the purpose of emergency regulation of sudden pollution incidents in the water diversion tunnel. The results show that in the process of emergency control of sudden pollution in long-distance water diversion projects, the timing of gate control is an important factor affecting the effectiveness of emergency control. Since the selection of operation timing is closely related to water quality observation data, the scientific layout of water quality monitoring points can provide a more accurate decision-making basis for emergency control []. Considering the uncertainty of pollutant transport, the two water withdrawal locations selected in this study were analyzed. When the water quality measuring point is close to the water withdrawal gate, such as the water quality measuring point and the return water withdrawal gate of the river, the measuring point can be regarded as being located at the outlet. According to the results in Figure 10, the mass of pollutants exiting conditions and is basically the same, and whether or not the response time is considered has little effect on the actual results. When the distance between the two is far, such as the water quality measuring point and the steady flow connection pool water withdrawal gate, the measuring point can be regarded as being located in the middle of the tunnel. At this time, when the response time is not considered, the mass of pollutants exiting condition shows a cliff-like decline compared with with the response time considered, and the amount of discarded water also increases significantly, seriously affecting the water discard efficiency. This indicates that water quality measuring points should be arranged near the gate to improve the timeliness and accuracy of operation.

In addition, during emergency control of long-distance water diversion projects, the pollution disposal efficiency can be significantly improved by combining operations between different gates downstream. In this study, when the water flow exceeds the Guiliu River discharge limit (7.08 m3/s), by considering the pollutant transfer process, the discharge gates of the Guiliu River and the steady flow connection pool are opened step by step to discharge the water. For example, under the operating condition , the results of the water discharge volume and the discharged pollutant concentration are significantly better than those under the operating condition , that is, the discharge gates of the Guiliu River and the steady flow connection pool are opened simultaneously.

4.3. Sustainable Benefits of Emergency Response to Sudden Pollution

As a core vehicle for optimizing cross-regional water resource allocation, long-distance water diversion projects offer significant sustainable benefits through their emergency response to sudden water pollution. By developing effective and scientific emergency response strategies, we can maximize the continuity of domestic and industrial water supplies in the receiving areas, reduce direct and indirect economic losses caused by pollution, and strengthen the resilience of these projects in supporting regional water security.

In this study, different gate operation timings resulted in significant differences in pollution treatment effectiveness and wastewater volume. Given the project’s location in a relatively water-scarce region of northern China, minimizing wastewater impacts should be prioritized to enhance the sustainability of the disposal strategy. Precise wastewater control can reduce impacts on residential, agricultural, and industrial water use, thereby enhancing the project’s risk management capabilities and promoting sustainable regional economic and social development.

4.4. Limit and Future Research

This study employed a control strategy that took response time into account for sudden pollution incidents. Compared to simple water withdrawal, this strategy, by capturing the peak concentration at the time it reaches the water discharge gate, can prevent large amounts of water from being discharged while discharging the vast majority of pollutants from the tunnel, improving withdrawal efficiency. However, because this study set the threshold concentration as a fixed value and failed to consider the dilution effect of high flow rates on pollutants, the efficiency of pollution discharge was significantly reduced under high-flow conditions. Therefore, subsequent work may consider setting threshold concentrations according to gradients at different flow rates, and further analyze the treatment effects between different threshold concentrations at the same flow rate, in order to improve the efficiency of emergency treatment.

In addition, the response time is set by monitoring whether the threshold concentration reaches the water discharge gate. This process does not take into account the diffusion of pollutants during the water diversion process. At this time, simply monitoring by threshold concentration will result in a shorter actual water discharge time. Therefore, by studying the decreasing trend of pollutant concentration during the transfer and diffusion process under different flow rates, we can predict the corresponding diluted concentration when the threshold concentration reaches the water discharge gate, carry out water discharge treatment at this concentration, and then optimize the response time mechanism.

5. Conclusions

This paper uses the water diversion tunnel of the Yin Chao Ji Liao Project as the research object. Based on SWMM, a one-dimensional hydrodynamic water quality model is established, and its reliability is verified. The variation patterns of pollutant concentrations under different flow rates are analyzed. The emergency control strategy of the water diversion project under sudden water pollution is studied. The response time formula of the gate combination control under different flow rates is derived. The main research conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The SWMM can better reflect the hydraulic characteristics of the engineering water diversion tunnel. The RMSE value of the model calculation results is between 0.014 and 0.042, which can be used to analyze the changes in water quality during the water diversion process.

- (2)

- As the flow rate gradually increases, the peak concentration in the tunnel shows a decreasing trend. The peak concentration change process presents a stage-by-stage characteristic, and the main influencing factors are different in each stage. In the early stage, the peak concentration is affected by the pollutant input process and shows the same change trend as the pollutant input process. In the later stage, it is mainly affected by the dilution of water flow and gradually decreases at different rates.

- (3)

- Taking the response time into consideration when operating the gate can, on the one hand, effectively remove pollutants, and on the other hand, avoid large amounts of water being discharged. Under different flow rates, its pollution disposal efficiency can be improved by 4.34–52.14% compared with basic water discharge measures.

- (4)

- During the operation of long-distance water diversion projects, the water quality safety of the project can be effectively guaranteed by setting up water quality monitoring points near the gates and using different gates for combined operating.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z., J.L. and S.Q.; Methodology, B.Z., J.L. and S.Q.; Software, C.J.; Validation, C.J.; Formal analysis, B.Z. and S.Q.; Investigation, C.J.; Resources, J.L.; Data curation, C.J.; Writing—original draft, C.J.; Writing—review & editing, B.Z., J.L. and S.Q.; Visualization, B.Z., J.L. and S.Q.; Supervision, M.L., H.B., X.X. and W.H.; Project administration, M.L., H.B., X.X. and W.H.; Funding acquisition, M.L., H.B., X.X. and W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Project (YC-KYXM-14-2024), Information Technology Project (YC-XXH-SG-01-2021) of China Inner Mongolia Yin Chao Ji Liao water supply Co., Ltd., and Science and Technology Project (HNKJ22-H107) of China Huaneng Group Co., Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the study are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Meiling Li, Haipeng Bi and Xiaodong Xu were employed by the company Inner Mongolia Yin Chao Ji Liao Water Supply Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Fan, F.M.; Fleischmann, A.S.; Collischonn, W.; Ames, D.P.; Rigo, D. Large-scale analytical water quality model coupled with GIS for simulation of point sourced pollutant discharges. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 64, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fan, T.; Cui, Y.; Nie, X. Diagnosis of key safety risk sources of long-distance water diversion engineering operation based on sub-constraint theory with constant weight. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 168, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien Bui, D.; Talebpour Asl, D.; Ghanavati, E.; Al-Ansari, N.; Khezri, S.; Chapi, K.; Amini, A.; Thai Pham, B. Effects of Inter-Basin Water Transfer on Water Flow Condition of Destination Basin. Sustainability 2020, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lei, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y. Integrated Assessment Method of Emergency Plan for Sudden Water Pollution Accidents Based on Improved TOPSIS, Shannon Entropy and a Coordinated Development Degree Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qin, Y.; Huang, M.; Sun, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Yu, C. SD–GIS-based temporal–spatial simulation of water quality in sudden water pollution accidents. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.; Ferra, I.; Gonçalves, I.; Marques, A.M. A Risk Assessment Model for Water Resources: Releases of dangerous and hazardous substances. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 140, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, P.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Du, X.; Fei, X. Evaluation of Water Network Construction Effect Based on Game-Weighting Matter-Element Cloud Model. Water 2023, 15, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Guan, Q. Effects of water transfer on improving water quality in Huancheng River, Chaohu City, China. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 206, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Wu, H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, T. Environmental Risk Assessment of Accidental Pollution Incidents in Drinking Water Source Areas: A Case Study of the Hongfeng Lake Watershed, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollason, E.; Sinha, P.; Bracken, L.J. Interbasin water transfer in a changing world: A new conceptual model. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2022, 46, 371–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. Inter-basin water transfer and water security: A landscape sustainability science perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Ren, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Yimin, H. The traceability of sudden water pollution in river canals based on the pollutant diffusion quantification formula. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1134233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-khafaji, F.; Al-Zubaidi, H. Numerical Modeling of Instantaneous Spills in One-dimensional River Systems. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2024, 23, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Wu, C.; Jiang, C.; Hu, S.; Liu, Y. Simulating the Impacts of an Upstream Dam on Pollutant Transport: A Case Study on the Xiangjiang River, China. Water 2016, 8, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Liu, D. Simulation of Sudden Water Pollution Accidents in Hunhe River Basin Upstream of Dahuofang Reservoir. Water 2022, 14, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, N.; Jamil, N.R.; Looi, L.J.; Yap, N.K. A management framework for sudden water pollution: A systematic review output. Water Environ. Res. A Res. Publ. Water Environ. Fed. 2024, 96, e11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yi, Y.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, X. Water pollution risk simulation and prediction in the main canal of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benziada, S.; Kettab, A.; Lagoun, A.M. Physical simulation of an active pollutant dispersion in a trapezoidal channel. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 5951–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Lei, X.; Long, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chang, W. Fast and optimal decision for emergency control of sudden water pollution accidents in long distance water diversion projects. Water Supply 2020, 20, 1356–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Long, Y.; Ma, C. A real-time, rapid emergency control model for sudden water pollution accidents in long-distance water transfer projects. Water Supply 2016, 17, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Lin, F.; Tao, Y.; Wei, T.; Kang, B.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Research on the Optimal Regulation of Sudden Water Pollution. Toxics 2023, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Early Warning of Sudden Water Pollution Accident Risks Based on Water Quality Models in the Three Gorges Dam Area. Water 2024, 16, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Mu, X.; Chen, W.; Stephens, T.A.; Bledsoe, B.P. Emergency Control Scheme for Upstream Pools of Long-Distance Canals. Irrig. Drain. 2019, 68, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, P.; Huang, X.; Sun, J.; Li, Q. Emergency Decision-Making for Middle Route of South-to-North Water Diversion Project Using Case-Based Reasoning and Prospect Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.L.; Wu, H.M.; Liao, W.; Lei, X.; Xu, H. Emergency Control Strategy for Unexpected Water Pollution Accidents in the Middle Route Open Channel of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1030–1032, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Ma, C. Emergency regulation for sudden water pollution accidents of open channel in long distance water transfer project. J. Tianjin Univ. 2013, 46, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Xu, G.; Ma, C.; Chen, L. Emergency control system based on the analytical hierarchy process and coordinated development degree model for sudden water pollution accidents in the Middle Route of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 12332–12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Luan, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, T.; Wu, P. Alleviating Pressure on Water Resources: A new approach could be attempted. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattel, G.R.; Shang, W.; Wang, Z.; Langford, J. China’s South-to-North Water Diversion Project Empowers Sustainable Water Resources System in the North. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.C.; Li, X.-Y.; Ma, Y.-J.; Smith, A.T.; Wu, J. A Review of the Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts of China’s South–North Water Transfer Project: A Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Gui, H. Comparative assessment of pollution control measures for urban water bodies in urban small catchment by SWMM. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1458858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Woo, W.; Park, Y.S. A User-Friendly Software Package to Develop Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) Inputs and Suggest Low Impact Development Scenarios. Water 2020, 12, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. Storm Water Management Model Reference Manual Volume II Hydraulics; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, J.; Li, Z.-L.; Sun, J. Modelling and Analysis of Hydrodynamics and Water Quality for Rivers in the Northern Cold Region of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriasi, D.; Gitau, M.; Pai, N.; Daggupati, P. Hydrologic and Water Quality Models: Performance Measures and Evaluation Criteria. Trans. ASABE (Am. Soc. Agric. Biol. Eng.) 2015, 58, 1763–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. China Environment Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/shjbh/shjzlbz/200206/W020061027509896672057.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Li, Y.; Chu, J.; Wei, G.; Jin, S.; Yang, T.; Li, B. Robust Placement of Water Quality Sensor for Long-Distance Water Transfer Projects Based on Multi-Objective Optimization and Uncertainty Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).