Abstract

Achieving decoupling between economic growth and carbon emissions is imperative for global sustainable development. This study provides a comparative analysis of this decoupling process in the European Union (EU) and BRICS countries from 1996 to 2023, employing the Tapio decoupling model and Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) decomposition analysis. Our findings reveal a stark contrast: the EU has achieved an average annual carbon emission growth rate of −1%, predominantly characterized by strong decoupling, whereas the BRICS nations exhibit an average growth rate of 6.26%, mainly in a state of weak decoupling. The LMDI results indicate that the intensity effect is the primary driver of carbon reduction in the EU, while the income effect is the most significant factor promoting emissions growth in the BRICS bloc. A novel finding is the identification of a near-symmetrical relationship between the energy transition effect and the fossil energy structure effect in the cumulative decomposition charts, offering a new perspective for evaluating energy system changes. The study concludes that while the EU demonstrates a more advanced decoupling pathway, significant internal disparities persist. For BRICS countries, mitigating the pressure from economic and population growth through industrial upgrading, differentiated energy policies, and enhanced renewable infrastructure is crucial. These insights provide valuable policy implications for both developed and developing economies in navigating their low-carbon transitions.

1. Introduction

Climate change represents a paramount challenge to global sustainable development, commanding significant international attention [1,2,3]. A central strategy in addressing this challenge is to break the historical link between economic prosperity and environmental degradation, particularly carbon emissions. Thus, the concept of “decoupling” originated in physics was later applied to describe the process of breaking the link between economic growth and environmental degradation [4,5]. This theory has been instrumental in assessing sustainable development progress, with Tapio’s [6] model providing a refined framework for classifying decoupling states. Meanwhile, it has also become a global consensus that countries actively formulate and implement relevant laws and policies to promote the utilization of renewable energy and take “sustainable development” as the core goal of future economic development [7,8].

Energy, as a fundamental input used in the production process, is intrinsically linked to economic activity; however, its consumption, especially from fossil fuels, is the primary source of CO2 emissions [9,10,11], and such emissions are regarded as an important factor causing global warming [12,13]. Consequently, understanding the relationship between economic growth, energy use, and carbon emissions is critical for formulating effective sustainable development policies [14,15].

The European Union (EU) and the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) represent two distinct paradigms in the global landscape of economic development and carbon emissions. The European Union (EU), a bloc of largely developed economies, is at the forefront of international efforts to address climate change and has positioned itself as a leader in climate action, exemplified by the European Green Deal, which targets climate neutrality by 2050 [16]. In contrast, the BRICS nations, as major emerging economies, are undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization, which presents both significant challenges and opportunities for managing carbon emissions [16,17,18]. This contrast offers a multi-dimensional perspective and a valuable analytical lens to examine the decoupling mechanism between carbon emissions and economic growth at different stages of development [19,20].

While numerous studies have applied decoupling analysis, many focus on individual countries [21,22,23] or specific sectors [24,25,26]. Comparative studies between blocs of developed and developing countries remain relatively scarce [17]. Furthermore, our previous research has explored material footprint (MF) drivers in similar groupings [27,28]. This study expands that work by shifting the focus to carbon emissions, a critical and directly comparable environmental indicator.

Therefore, this study selects the EU and BRICS countries to address the following three key questions: (1) to what extent have carbon emissions been decoupled from economic growth in the EU and BRICS countries? (2) What are the predominant drivers behind carbon emission changes in these two groups? (3) How can the decoupling process be effectively promoted? To answer these questions, we analyze data from 1996 to 2023 for all 27 EU member states and the five BRICS countries, employing an integrated Tapio–LMDI framework. This period encompasses significant global events, including the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol [29], the adoption of the Paris Agreement [30], and the economic rise in the BRICS nations.

The contribution of this study is threefold. First, in terms of analytical methods, this study has broken through the limitations of previous macro-level research on the decoupling of carbon emissions and economic growth by a systematic, country-by-country decomposition analysis of the decoupling status and driving factors of each of the 27 EU member states and the BRICS countries, revealing significant intra-group heterogeneities. Second, we have for the first time identified and discussed the symmetrical phenomenon of the cumulative contribution between the “energy transition effect” and the “fossil energy structure effect”, offering a new perspective for the evaluation of energy structure optimization and transformation effects and expanding the application of LMDI analysis. Third, the findings offer nuanced policy insights tailored to the specific circumstances of the EU and BRICS countries, contributing to the discourse on equitable and sustainable low-carbon pathways.

The overall arrangement of the article is as follows: Section 2 summarizes the existing research on decoupling and structural decomposition and discusses in detail the innovations of this article. Section 3 provides a detailed introduction to the research methods and data sources used in this article. Section 4 and Section 5, respectively, discuss the research results, implications, and causes of the decoupling situation, as well as driving factors of the EU and the BRICS countries. Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the policy implications of the current research. In Section 7, we expound on the current limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

The term “decoupling” originated from physics and refers to the reduction or elimination of the interaction between two or more physical quantities [31,32,33]. At the beginning of the 21st century, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) proposed the “decoupling” theory [4], and subsequently applied it to the study of the relationship between economic growth and carbon emissions in order to measure the degree of decoupling. It was initially classified into absolute decoupling and relative decoupling [5]. With the application of this concept in the fields of economics and environmental science, Tapio has expanded this methodology and proposed another decoupling model, classifying the decoupling conditions into eight categories [6]. The underlying logic behind this term lies in the contradiction and conflict between economic prosperity and growth and the deterioration of the ecological environment. Therefore, the term “decoupling” describes the out-of-sync phenomenon between environmental pressures (such as carbon dioxide emissions) and economic growth [34,35]. Environmental impact decoupling is regarded as a means to break the connection between environmental damage and economic growth, reducing adverse environmental impacts while increasing economic output [36].

The LMDI (Logarithmic Mean Degard Index) method is a decomposition analysis tool widely used in energy and carbon emission research [24,37,38]; this method is based on the mathematical decomposition form of multiplication or addition and is used to attribute changes in carbon emissions or energy consumption to multiple driving factors. At present, there are many studies on the driving factors of energy consumption and carbon emissions. Existing studies are conducted from the perspectives of international trade, labor force factors, population size, energy consumption patterns, technological progress, etc. [39,40,41,42,43], different quantitative research methods were employed to explore the relationship between economic growth and environmental change. Among these studies, factor decomposition techniques are frequently utilized to identify the driving factors affecting energy consumption and carbon emissions. The primary decomposition methods include structural decomposition analysis (SDA), index decomposition analysis (IDA), and production theory decomposition analysis (PDA) [44,45,46]. The SDA method is limited to additive decomposition, which restricts its applicability in empirical analyses, resulting in its limited use [47]. In contrast, the PDA method is primarily employed to uncover driving factors related to production technology and efficiency but fails to comprehensively account for influences such as industrial structure and energy consumption patterns [48]. The IDA method is the most widely applied, with the LMDI model being recognized for its “optimal” decomposition performance [49,50]. A large number of studies have adopted the LMDI decomposition method to investigate the influencing factors behind carbon emission changes [21,51,52,53].

Combining the Tapio decoupling model with the LMDI decomposition analysis allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between carbon emissions and economic growth, as well as the underlying driving mechanisms [54,55,56,57,58]. The Tapio model is effective in illustrating the coupling or decoupling status between carbon emissions and economic growth. It relies on the elasticity between the growth rates of carbon emissions and GDP, offering a straightforward depiction of whether weak decoupling, strong decoupling, or coupling has occurred. However, the Tapio model can only provide a macro-level description and cannot reveal the specific factors that lead to decoupling or coupling. The LMDI decomposition method has a significant advantage in this regard. It can break down carbon emission changes into multiple quantifiable driving factors, such as energy intensity, energy structure, economic structure and activity level, etc. By combining the two, researchers can not only determine whether a certain region or period has achieved decoupling, but also delve into the driving mechanisms behind decoupling, providing a more targeted basis for policymaking.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have applied the Tapio decoupling model and the LMDI decomposition method to investigate the “decoupling” issue. Among these studies, there are not only studies on the decoupling of resource consumption [27,59,60,61], but also environmental impact decoupling studies [62,63]. In the research on the decoupling of environmental impacts, the decoupling between economic development and carbon emissions is currently the most concentrated field of study. This is because carbon dioxide emissions can well represent the common situation in the relationship between the environment and the economy [62]. A large number of literature discussions mainly exist at the industry level and regional level. First of all, the decoupling analyses of individual industries mainly include the manufacturing sector [64], the metal industry sector [65], the transportation industry [66], the mining industry [67], the steel industry [68], the construction industry [69], and the agricultural industry [70]. There are also a few papers that use the Tapio-LMDI method to conduct multi-regional comparative analysis. For example, Guo et al. [28] used the Tapio-LMDI method to conduct a comparative analysis of the decoupling and driving factors of the material footprints of the EU, the United States, and the BRICS countries.

Studies on regional decoupling analysis primarily focus on specific countries. For example, recent research has examined Poland’s energy-related CO2 emissions following its accession to the EU, analyzing various indicators such as energy use, fossil fuel consumption, economic performance, and environmental metrics to discuss driving factors and decoupling elasticity [71]. Another study explored the impact of the growth of eight core industries in India on environmental degradation [72]. As the world’s second-largest economy and the largest carbon emitter, China is gradually reducing its dependence on CO2 emissions for economic growth [73]. In Morocco, an analysis of greenhouse gas emissions and economic growth revealed that achieving the government’s absolute decoupling target will require more proactive carbon pricing (CPI) policies [74]. A comprehensive decoupling and decomposition analysis of Turkey’s economic development, electricity generation, and CO2 emissions was also conducted [75]. In the United States, a study on the relationship between transportation, economic growth, and emissions from conventional and alternative energy sources found that improving energy efficiency is effective for environmental protection [76]. A large number of studies have conducted decoupling analyses on the partial or overall situation of a specific country to discuss the progress of decoupling in that country.

In addition to analyses focusing on individual countries, many studies have examined regional organizations or groups of similar countries. For instance, research on 29 countries that have announced carbon neutrality targets investigates whether these nations have already achieved decoupling between carbon emissions and economic growth [77]. In the Middle East, where fossil fuel resources are abundant and energy costs are low, studies confirm that economic growth tends to involve higher energy consumption, leading to more pollution and greenhouse gas emissions [78]. Several studies have focused on EU countries to analyze the decoupling between economic growth and carbon emissions, aiming to understand the EU’s emission trends and the impact of its energy policies on decoupling [19,20]. Research on 33 African countries examined the relationship between urbanization and carbon emissions, finding that only four countries achieved long-term decoupling [79]. Another study analyzed the long-term drivers of carbon emissions in OECD countries through decomposition and decoupling techniques [80]. Additionally, emerging economies have been studied to assess whether they can achieve a decoupling of economic growth and carbon emissions in the context of global climate change [17]. These studies primarily focus on regional organizations or country groups, analyzing decoupling characteristics and differences by examining sets of countries with common features.

However, large-scale comparative studies on the issue of decoupling remain relatively scarce, particularly those that systematically contrast developed and developing countries on carbon emissions and economic growth. Moreover, most existing studies analyzing the driving factors behind the decoupling process exhibit similar limitations. A significant portion of research on decoupling drivers focuses on individual countries [21,22,23,81,82] or specific sectors [24,25,26,83]. Some studies have examined a few countries or regional groupings, such as the analysis of energy intensity drivers in Asia and Eastern Europe [84]; the decomposition of carbon and energy intensity in the U.S. and Germany [85]; and the driving forces of final energy consumption and emissions in ASEAN countries [86]. Nevertheless, whether in terms of decoupling analysis or the exploration of its driving factors, comparative studies between countries are still relatively lacking, especially comparisons between different country groups. To address this gap, the present study selects the European Union and the BRICS countries as the subjects of a comparative analysis. It examines the overall decoupling processes and driving forces within and across these two groups from 1996 to 2023, aiming to identify the factors that influence decoupling and to provide valuable insights and policy references for both developed and developing nations.

3. Methodology and Data Description

3.1. Research Framework

As in our previous studies [27,28], This study first uses the Tapio-LMDI model. Based on the Tapio decoupling model, the decoupling index of the EU and BRICS countries is calculated to examine the decoupling status between carbon emissions and economic growth in each country. Second, the Kaya factor decomposition model is used to decompose the driving factors of carbon emissions in the EU and BRICS countries. Finally, the decomposition results are classified for analysis and discussion, comparing the heterogeneity of the main driving factors of carbon emissions between EU countries and BRICS member states.

3.2. Tapio Model

We use the Tapio decoupling model to measure the relationship between carbon emissions and economic growth. The decoupling elasticity between carbon emissions and economic activity is denoted as DE.

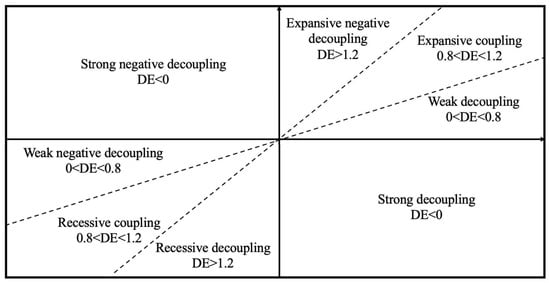

In the formula, CE represents carbon emissions, and Δ indicates the change from the base year 0 to year t. The Tapio decoupling index takes the value of DE as the standard to determine the decoupling status. Among all decoupling states, strong decoupling is the most ideal state, while strong negative decoupling is the least favorable. As shown in Figure 1, according to the decoupling elasticity, the change in carbon emissions, and the change in GDP, decoupling can be classified into the following eight types. The classification and impacts of decoupling states are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Decoupling types.

Table 1.

Classification and definitions of decoupling statuses.

3.3. LMDI Model

The Kaya Identity was first proposed by Yoichi Kaya in 1989 at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [87]. This identity is scientifically rigorous and aids in understanding the complex interactions between economic development and environmental sustainability, as it reflects how changes in population, economic activity, energy efficiency, and carbon intensity impact overall carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions [88,89,90,91,92]. As a fundamental tool in environmental research, the Kaya Identity connects carbon emissions with economic and energy issues, effectively explaining the driving factors behind carbon emissions and thereby guiding the formulation and application of policies and sustainable development strategies. This study employs the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) method, adhering to the practical guidelines outlined by Ang [49,93], and categorizes the driving factors into population effect, income effect, structural effect, intensity effect, and energy consumption effect.

The general equation for index decomposition analysis (IDA) can be expressed as follows:

where X represents the variable to be studied, which is decomposed into n factors (, …). These factors cause X to change over time. Under the assumption of the addition principle, the following formula can be obtained:

where represents the total change between the 0th period, i.e., , and the t-th period, i.e., . The effect of the k-th influencing factor on the change in X represented by the right side of the equation is as follows:

Using the above Formula (3), carbon emissions can be decomposed as follows:

In this formula, represents the population effect (P), represents the income effect (Y), represents the industrial structure effect (S), represents the carbon emissions generated by industrial development, which can reflect the contribution of a country′s industrial production to carbon emissions, called the intensity effect (I), represents the proportion of fossil energy use in all primary energy, called the fossil energy structure effect (F), reflects the carbon emissions of fossil energy, which we call the carbon emission effect (C), and represents the primary energy used to produce unit carbon emissions. The more clean energy is used, the more total energy is required to produce unit carbon emissions, which can reflect the country′s energy transformation, called the energy transformation effect (T). CE can be expressed as follows according to the additive principle:

The formula for each factor based on LMDI decomposition can be expressed as follows:

LMDI for P:

LMDI for P:

LMDI for S:

LMDI for I:

LMDI for F:

LMDI for C:

LMDI for T:

In order to intuitively reflect the contribution of each effect, we define the contribution rate as follows:

In the formula, represent the contribution rates of population effect, income effect, industrial structure effect, intensity effect, fossil energy structure effect, carbon emission effect, and energy transformation effect, respectively.

3.4. Data Selection

First, from the 195 countries worldwide, those that can effectively and clearly present the expected results of the study are selected. Based on this, the sample countries should meet three criteria: they should represent both developing and developed countries, as there are significant differences in their economy, technology, and social structure; their geographical locations should be distributed across the world to enhance the global rather than regional significance of the research results; and they should be at different stages of industrialization and decarbonization, making the research results more representative and comparable.

Based on the above standards, we selected the 27 EU member states and the BRICS countries as the research subjects. BRICS expanded its membership in 2024, but since the research data in this paper end in 2023, we use the original five BRICS members (Russia, China, India, Brazil, and South Africa) to represent the situation of the BRICS organization.

Due to differences in development models and energy endowments, the EU member states and BRICS countries show significant differences in energy use and sustainable development pathways. For example, the EU as a whole is in the post-industrialization stage, entering a period of accelerated low-carbon transition, with total carbon emissions showing a downward trend and exhibiting typical “strong decoupling” characteristics [20]. Among them, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden in Western and Northern Europe are global leaders in green technology, energy efficiency, and renewable energy utilization, having built a high-tech-driven low-carbon economic model, while Poland, Czech Republic, and Bulgaria in Eastern Europe, due to coal dependence, single industrial structures, and constraints in finance and technology, have made relatively slow progress in carbon reduction [94,95]. This “overall advanced, partially lagging” structural feature makes the EU valuable for studying coordinated carbon reduction as an economic integration system, as well as providing an ideal case for exploring decoupling mechanisms within a region. Research on the EU not only helps understand its policy pathways for balancing development and emission reduction but can also provide useful references for institutional design and low-carbon cooperation in other regional organizations (such as the ASEAN and the African Union).

In sharp contrast, the BRICS countries are generally still in the accelerated stage of industrialization or urbanization, with rapid economic growth, continuously rising energy consumption, and a significant upward trend in carbon emissions, overall showing “weak decoupling” or “coupling” characteristics [18]. China and India face enormous carbon emission pressures during industrial expansion and infrastructure construction, while South Africa and Brazil face the dual challenges of population growth and energy structure adjustment. BRICS represents the typical path of the “Global South” in the industrialization process, with large-scale and high development heterogeneity. It is a key sample for understanding the structural dilemmas and policy choices faced by developing economies in coordinating carbon reduction and growth. Studying the decoupling process of BRICS can help identify its unique characteristics in energy transition, technology adoption, income effect, and population dynamics, providing theoretical support and policy references for building a fair, inclusive, and sustainable global low-carbon transition pathway.

Selecting these two groups of countries for research not only enables a systematic comparison of the similarities and differences in carbon reduction pathways of countries at “different transition stages,” but also maximizes the reflection of the diversity and complexity of the global decoupling process, providing more targeted policy references for different types of countries worldwide.

We use carbon emissions data from 1996 to 2023 as the basic variable for the empirical analysis in this study. The carbon emissions and energy consumption data are from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and Wind Database. GDP, population, and industrial added value data are from the World Bank, converted into constant 2015 US dollars. No additional assumptions are introduced in the data processing of this study, and no artificial settings are made for trends, functional relationships, etc. All analysis results are directly calculated based on the original data.

4. Decoupling of the European Union and BRICS Countries

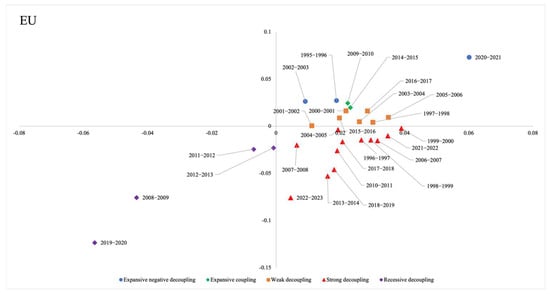

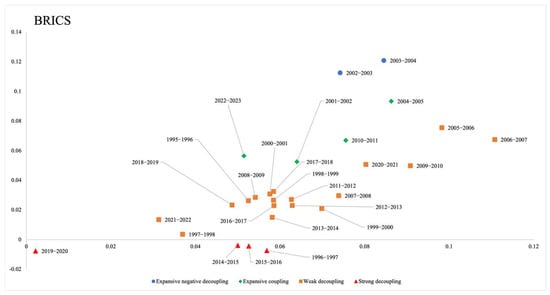

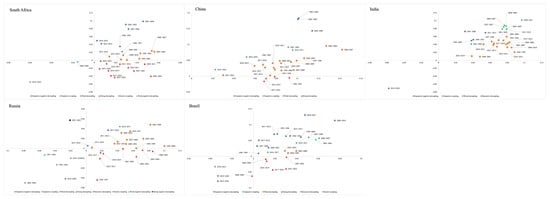

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the overall decoupling trends of the EU and BRICS countries, respectively, while Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the decoupling trends of each of the 27 EU member states and the 5 BRICS countries, respectively. We observe from both the overall and individual country dimensions. The horizontal axis represents the rate of change in economic output, the vertical axis represents the rate of change in carbon emissions, and the points in the figures indicate the decoupling status in a given year.

Figure 2.

Overall decoupling trend of EU countries.

Figure 3.

Overall decoupling trend among BRICS countries.

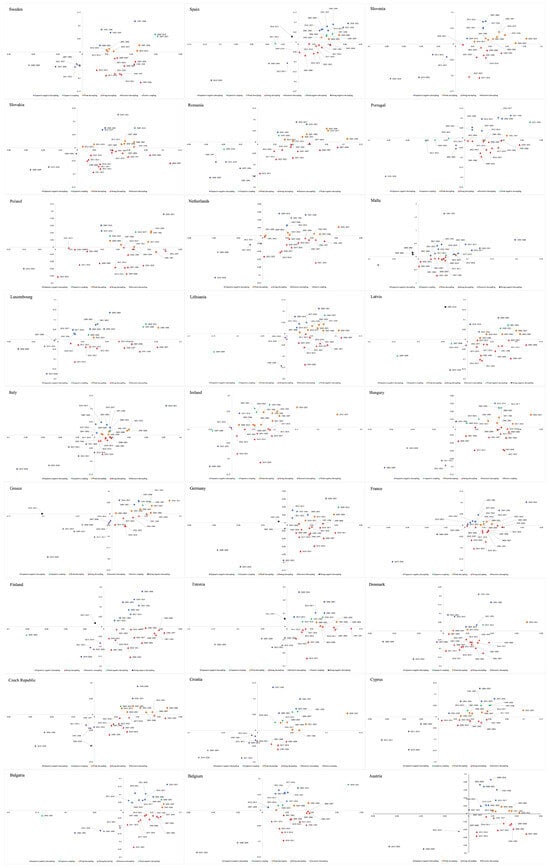

Figure 4.

Decoupling trends among EU countries.

Figure 5.

Decoupling trends among BRICS countries.

As shown in Figure 2, the overall decoupling relationship between CO2 emissions and economic growth in EU countries is relatively good. The frequency of strong decoupling is much higher than in BRICS countries. Although EU countries as a whole are in a stable and strong decoupling state, this trend was interrupted during the global economic crisis. Fluctuations in decoupling status appeared around 2008, both at the EU level and in individual countries. This indicates that slower economic activity and lower energy demand had an impact on carbon emissions. In addition, the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 also had a negative effect on the decoupling status of the EU and its member states.

As shown in Figure 4, countries such as Germany, France, and Italy, which have high energy consumption, show a more complex and cyclical decoupling pattern. These countries have long played important roles in global manufacturing and industry. They consume large amounts of energy in industry and rely heavily on natural gas and electricity. In Germany and Italy, high-energy-consuming sectors are mainly in petrochemicals, non-metallic minerals, and steel. These sectors are major economic pillars, which makes them more vulnerable to energy crises [96,97]. Since the outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, Russia has reduced natural gas supplies to Europe as a countermeasure. This caused shortages in countries such as Germany, France, and Italy, which are highly dependent on gas imports [98]. At the same time, Europe had to buy gas from other countries at high prices. This caused energy prices to surge and signs of economic recession to appear [99]. The cycles of decoupling and recoupling reflect this instability. It is closely linked to these countries’ energy structures and their urgent need for energy transition.

Countries such as Finland and Sweden in the EU show distinctive decoupling patterns. Both are famous low-carbon countries, with renewable energy making up about 70% of their total energy mix [100,101]. Finland shows strong decoupling in most years. Sweden mainly shows strong decoupling and weak decoupling. This may be due to their balanced energy structures, low-carbon industrial structures, and high energy efficiency. As a result, there is no clear linear link between economic growth and CO2 emissions [102]. However, around 2000, both countries experienced expansive negative decoupling. This is likely related to strong industrial growth and high economic growth rates at that time.

Some countries, such as Malta and Greece, have less favorable decoupling performance. They often show expansive negative decoupling, recessive decoupling, and expansive coupling. Although the EU as a whole peaked in carbon emissions in 1990, and most member states reached their peaks between 1990 and 2008, the poor decoupling performance of these countries may be related to their energy structures. Malta relies mainly on oil-fired power plants, while Greece’s energy is mostly from fossil fuels. Malta is small, densely populated, and has limited energy and resources. It depends heavily on imported fossil fuels. Malta also lacks technology and products in energy production, alternative energy development, and energy saving. As a result, its decoupling status has remained poor since 2014. Greece, however, has improved its decoupling status since 2016. This is linked to its active promotion of energy transition and green electricity development.

As shown in Figure 3, BRICS countries overall show a weak decoupling between CO2 emissions and economic growth. This means that economic growth and carbon emissions still change in step. Continuous economic growth has encouraged the accumulation of carbon emissions.

As shown in Figure 5, developing countries such as Brazil and India have relatively poor decoupling performance. In many years, they mainly experienced expansive negative decoupling, recessive decoupling, and expansive coupling. For example, around 2014, Brazil mainly showed expansive negative decoupling and recessive decoupling. This is related to economic fluctuations and the middle-income trap. In recent years, Brazil has introduced various emission reduction policies to strengthen its role in the UNFCCC. Brazil has pledged to raise its greenhouse gas reduction target from 43% to 50% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 [103]. Through green energy transition, Brazil’s carbon emissions have fallen significantly. Since 2020, its decoupling status has improved, showing strong and weak decoupling. Research also shows that in India, there is a long-term link between output growth and carbon emissions. This means that energy consumption will likely continue to cause environmental degradation in the long run [104]. This matches the poor decoupling performance found in this study.

Developing countries such as China and Russia show better decoupling performance. China’s performance is the most favorable, with most years showing strong or weak decoupling. This is closely linked to China’s active fulfillment of international commitments and promotion of global governance. After joining the WTO in the early 21st century, China’s economy entered a period of rapid growth. Energy consumption and CO2 emissions also grew quickly. By 2005, China had overtaken the United States as the world’s largest CO2 emitter [105]. During this period, the decoupling relationship showed expansive coupling and expansive negative decoupling, which lasted until about 2005. After 2005, with the implementation and revision of the Energy Conservation Law and other regulations [106], China began to reduce its excessive use of fossil fuels. However, total and per capita carbon emissions still grew strongly. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a return to expansive coupling. This may be related to the link between economic growth and the vulnerability of the energy system. Overall, although China saw the fastest growth in both carbon emissions and economic output during the study period, the general trend shifted from expansive coupling to weak and even strong decoupling. Technological progress played an important role in this shift.

Over the past 60 years, CO2 emissions per unit of GDP have declined globally, even in fast-growing economies such as India and China. However, relative decoupling is not enough. Tackling climate change requires absolute decoupling. The link between CO2 emissions and economic growth is complex and multi-layered, involving many variables and dynamic changes. In the current context of global climate change, developed countries are gradually reducing their GDP dependence on carbon emissions. Developing countries still need to control total energy use and improve energy efficiency. This highlights the importance of continued attention and joint efforts in environmental protection and sustainable development, to ensure the sustainable use of global resources and to promote economic and social sustainability.

5. Analysis of Driving Effects of the EU and BRICS Countries

5.1. Analysis of Driving Effects of EU Countries

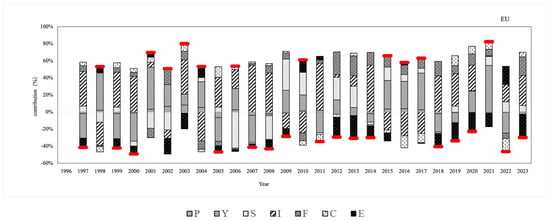

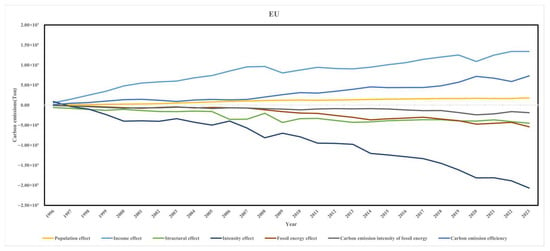

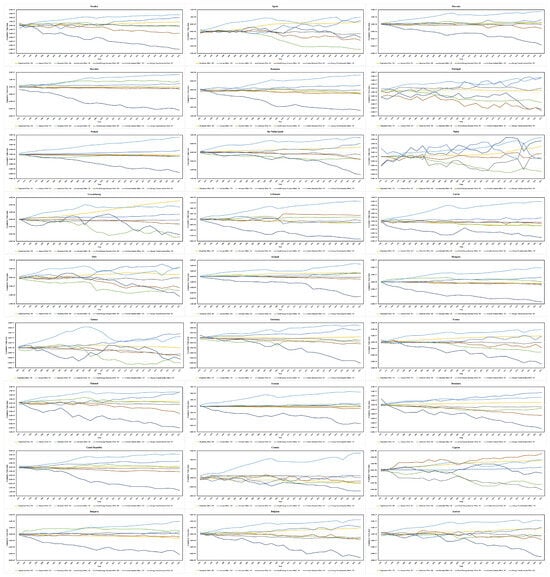

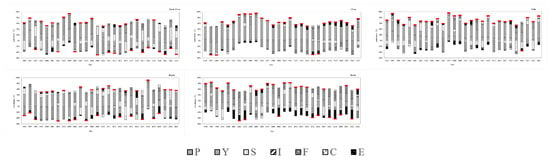

Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the contribution of carbon emission driving factors and the cumulative effects for the EU as a whole, respectively. Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the corresponding charts for individual EU member states. The contribution charts clearly show the extent to which each factor influences changes in carbon emissions, while the cumulative effect charts reflect the long-term impact trends of these factors.

Figure 6.

Decomposition of driving factors of carbon emissions in European countries. Red on the top indicates more carbon emissions, and red on the bottom indicates less carbon emissions.

Figure 7.

Cumulative effects of driving factors for EU carbon emissions.

Figure 8.

Contribution decomposition of carbon emission drivers in EU countries. Red on the top indicates more carbon emissions, and red on the bottom indicates less carbon emissions.

Figure 9.

Cumulative effects of carbon emission drivers in EU countries.

As shown in Figure 8, in most EU countries, the impact of population on the increase in carbon emissions is manifested as a promoting effect, while it shows an inhibitory effect on the reduction of carbon emissions, but the overall contribution rate is not high. However, a few EU countries, such as Romania, Lithuania, Latvia, Croatia, and Bulgaria, have shown the opposite trend. This might be related to the fact that their populations have been experiencing negative growth for many years. From the perspective of cumulative effects, population is not the main cause of the increase in carbon emissions, but in most countries, its contribution shows a gradually rising trend (Figure 9).

For EU countries, the income effect has been one of the main contributors to the increase in carbon emissions during the study period (Figure 8). Although the contribution of the income effect to carbon emissions varied across different EU countries and years, it generally promoted the rise in emissions. Overall, its contribution to increasing emissions outweighed any suppressive effect it might have had (Figure 9). This is because economic activity tends to drive up carbon emissions during certain periods. Notably, in some years, the income effect in certain EU countries actually contributed to a reduction in carbon emissions. This phenomenon can mainly be attributed to two factors: first, changes in the structural effect moderated the influence of the income effect [107,108], and second, economic fluctuations at both global and national levels impacted the income effect [109]. During the 2008–2009 financial crisis, carbon emissions declined due to a reduction in economic activity [110]. Although some countries experienced a rebound in emissions post-crisis [109,111,112], it is still evident from the figures that countries such as Germany, France, and Italy saw a decline in emissions during the post-crisis period. This may be linked to the ongoing decoupling process between carbon emissions and GDP in EU countries [110]. Furthermore, it can be anticipated that in EU countries where the income effect currently plays a significant positive role, such as Finland and Luxembourg, the contribution of the income effect to carbon emissions may gradually stabilize or even decline in the future.

The structural effect in EU countries has generally acted to suppress the growth of carbon emissions, though its restraining influence has been less pronounced than that of the intensity effect (Figure 9), This may be related to the EU’s active promotion of a green, low-carbon industrial transformation and the advancement of digital economic transition. Specifically, there are several contributing factors: First, most European countries, as well as the EU as a whole, have established clear carbon neutrality targets. For instance, the EU has committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 [113]. Second, the EU has strongly promoted the development and deployment of renewable energy. Not only has it enacted the Renewable Energy Directive, which legally mandates member states to increase the share of renewables, but individual member countries have also actively advanced their use. For example, Nordic countries such as Denmark are global leaders in wind energy, having extensively developed both onshore and offshore wind power projects. Southern European countries such as Spain, Italy, and Greece, have become the main drivers of solar power generation due to their abundant solar resources [114]. In addition, countries like the Netherlands and Germany are actively promoting the hydrogen economy, aiming to apply hydrogen technologies across transportation, industry, and residential sectors [115,116]. Third, the EU has achieved significant technological innovation in improving energy efficiency and advancing energy transitions [117,118]. From a policy perspective, the EU has introduced a wide range of energy innovation policies that provide comprehensive support and direction for renewable energy development and efficiency improvement [119]. At the implementation level, these innovations include renewable energy technologies, energy storage systems, carbon capture and storage (CCS), carbon capture and utilization (CCU), and advances in transportation and nuclear energy technologies.

Since the 1970s, the European Union has undergone a wave of deindustrialization. On one hand, this was driven by productivity gains [120], which to some extent contributed to reductions in carbon emissions. On the other hand, due to the progress of economic globalization, trade between developed and developing countries has grown rapidly. As a result, the European Union has outsourced or relocated some manufacturing industries to low-cost countries, especially labor-intensive and environmentally sensitive ones [121,122]. Furthermore, under its emissions reduction commitments in the Paris Agreement, the EU has implemented stringent climate policies. For example, its Emissions Trading System (ETS) imposes carbon taxes or emissions caps on high-emission sectors such as steel, cement, and chemicals, which has further accelerated the outsourcing and relocation of industrial production [123]. As high-carbon manufacturing shifts abroad, this industrial offshoring may also be a contributing factor to the EU’s overall decline in carbon emissions.

The intensity effect in EU countries has generally contributed to the reduction of carbon emissions. The difference lies in the timing of when this effect became significant. In countries such as France, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden, the intensity effect began to suppress emissions relatively early, around the year 2000. In contrast, in countries like Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, this suppressive effect emerged later. Specifically, as shown in Figure 9, Sweden experienced a notable reduction in emissions as early as 1999, with a decrease of 19.11 million tonnes of CO2 between 1998 and 2000. This may be attributed to Sweden’s significant reduction in fossil fuel dependence around the year 2000; from 1970 to 2000, the country’s energy intensity declined by 40%, with technological innovation being the primary driver of this decrease [124]. In contrast, Ireland saw a marked increase in the suppressive impact of the intensity effect during the periods of 2014–2015 and 2019–2022, reducing carbon emissions by 18.64 million tonnes and 20.98 million tonnes, respectively. During these years, the intensity effect accounted for roughly 50% of the total reduction in emissions, significantly higher than in other years (Figure 8).

During the study period, Spain’s intensity effect exhibited an opposite trend compared to the EU overall and most other member states. Except for the period after 2018, when the intensity effect began to act as a suppressor of carbon emissions, it generally contributed to an increase in emissions during the rest of the period (Figure 8). While most European countries have reduced their energy intensity over the past few decades, Spain showed the opposite trend. This divergence may be related to differences in Spain’s economic structure. The construction sector in Spain accounts for 9.4% of GDP, significantly higher than the 5.2% average among the EU-15 countries [125]. This is closely tied to Spain’s real estate boom, which drove large-scale investment in infrastructure, housing, and vacation homes, in turn increasing energy demand in other sectors [126], and placing strain on the tertiary sector. Additionally, the transport sector also holds a relatively high share of Spain’s GDP [125]. In the case of Spain, there are still signs of inefficient energy use, which may be related to its location along the Mediterranean coast and relatively high climate temperatures. The low heating demand does not encourage Mediterranean countries to introduce efficient heating systems. In the industrial sector, Spain’s National Energy Efficiency Strategy notes that significant energy efficiency improvements could be made in the production processes of non-metallic minerals, basic metals, and chemicals [127].

Notably, during the study period, the intensity effect in Germany contributed to more than 40% of the reduction in carbon emissions in most years, reaching as high as 60% in some cases (Figure 8). Clearly, the rate at which the intensity effect suppressed emissions exceeded the rate of economic growth, indicating a certain level of decoupling between economic development and energy demand in Germany. In 2023, Germany’s carbon intensity fell to its lowest level in 30 years, reaching 572 million tonnes of oil equivalent. This achievement is closely linked to the country’s active implementation of the “Energiewende” energy transition strategy [128]. This strategy aims to promote the supply and use of renewable energy and reduce the output of coal-fired power generation and energy-intensive industries.

As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, from an overall EU perspective, the energy structure has played a modest role in suppressing carbon emissions. Between 1996 and 2023, adjustments in the energy structure cumulatively reduced emissions by approximately 540 million tonnes of oil equivalent. However, the contribution of energy structure to total carbon emissions reduction was relatively limited, with its share below 10% in most years. During the study period, fossil fuels accounted for an average of about 76% of the EU’s primary energy consumption. In most EU member states, the share of fossil fuels in the primary energy mix declined over time. It is worth noting that both the COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict between Russia and Ukraine have had extraordinary external impacts on the energy sector of the EU. The pandemic severely disrupted the renewable energy industry, causing delays in project development due to insufficient funding and supply chain interruptions for equipment and components [129]. The embargo on coal and natural gas brought about by the Russia–Ukraine conflict has led to sharp fluctuations in energy demand [130]. Nonetheless, in the long run, these external shocks are expected to spur innovation and growth in the renewable energy sector, accelerating the replacement of fossil fuels [131]. This is consistent with the study’s findings, which show a gradually increasing cumulative suppressive effect of energy structure on carbon emissions.

Before the COVID-19 crisis, energy consumption in EU countries reached its lowest level in 2014. However, it increased for three consecutive years from 2014 to 2017 [132]. Following the pandemic, between 2020 and 2023, the EU’s primary energy consumption declined once again, which may be attributed to significant progress in achieving energy efficiency targets. In addition to energy efficiency, energy consumption is also influenced by economic activity [133]. Specifically, during the expansion period from 2000 to 2008, most countries increased energy consumption in the production sector. In contrast, between 2008 and 2018, most countries reduced energy use in that sector, a trend likely affected by changes in labor productivity and employment dynamics [133].

However, there are exceptions. In the case of Cyprus, the energy structure effect shows a markedly different pattern, as it has significantly contributed to the increase in carbon emissions. This is likely related to the country’s geographical and resource constraints. Due to a lack of domestic energy resources, Cyprus relies almost entirely on imported hydrocarbon fuels for energy production. Over 90% of its electricity generation depends on petroleum products, with the remaining 9% supplied by imported coal (4.5%) and solar energy (4.5%). Solar energy is the only locally available natural energy resource [134].

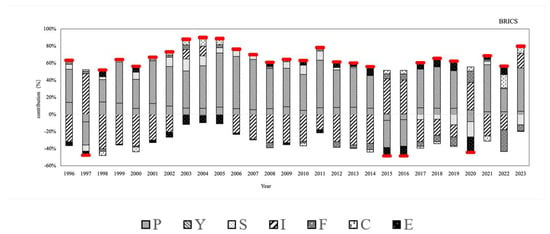

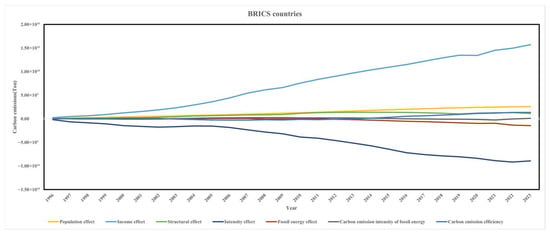

5.2. Analysis of the Driving Effect of BRICS Countries

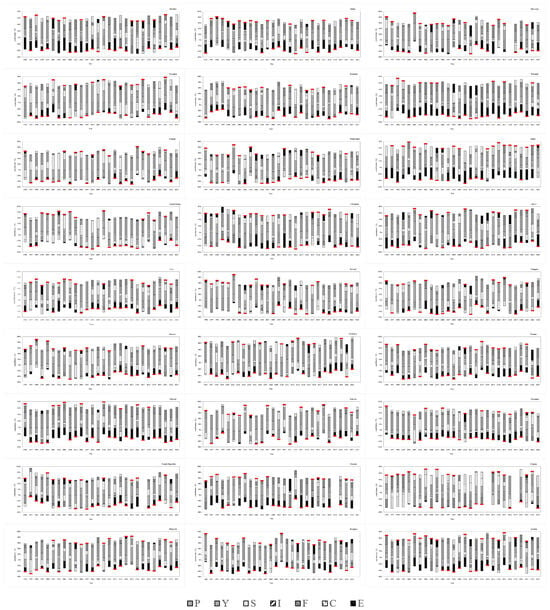

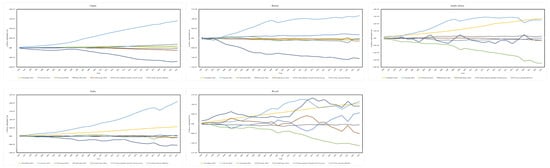

Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the contribution of carbon emission driving factors and the cumulative effects for the BRICS as a whole, respectively. Figure 12 and Figure 13 present the corresponding charts for individual BRICS member states.

Figure 10.

Decomposition of the contribution of driving factors to BRICS’ overall carbon emissions. Red on the top indicates more carbon emissions, and red on the bottom indicates less carbon emissions.

Figure 11.

Cumulative effect of driving factors of BRICS carbon emissions.

Figure 12.

Contribution decomposition of carbon emission drivers in BRICS countries. Red on the top indicates more carbon emissions, and red on the bottom indicates less carbon emissions.

Figure 13.

Cumulative effect of carbon emission driving factors in BRICS countries.

As shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13, the population effect has generally contributed to the increase in carbon emissions across the BRICS countries. This effect is particularly pronounced in India, South Africa, and Brazil, while it is relatively modest in Russia and China. Take India as an example. It has nearly one-fifth of the world’s population and is undergoing profound transformation and rapid urbanization. This may have increased energy consumption to a certain extent and triggered an energy crisis in India [135]. In contrast, in China, changes in population structure have had a greater impact on carbon emissions than population size alone [136]. The proportion of the working-age population in China reached its peak around 2010, which may have led to a relatively small contribution of the population effect, being less than 5% in most years (Figure 12). Although many scholars have argued that population growth leads to higher CO2 emissions and treat it as a key variable in forecasting future emissions [137,138,139,140], real-world evidence suggests that population is often more of a surface-level factor than a decisive one. In most cases, population growth drives demand in sectors such as transportation and housing, which in turn contributes to increased emissions [141]. Additionally, many developing countries are still in the midst of rapid urbanization, which also plays a role in shaping carbon emission trends [142].

The income effect in the BRICS countries has played a significant role in driving carbon emissions, with its contribution rate exceeding 40% in most years (Figure 12). At the country level, as shown in Figure 12, India’s GDP declined by approximately USD 155.37 billion between 2019 and 2020 due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was reflected in the income effect, which contributed to a reduction of about 160 million tonnes of carbon emissions during that period. Similarly, between 2008 and 2009, Russia’s income effect contributed to a reduction of approximately 120 million tons in carbon emissions. This opposite effect might be related to the global economic crisis in 2008, which led to a slowdown in economic activities and a decrease in industrial production. The situation in South Africa is the same. During 2008–2009, the income effect led to a reduction of approximately 13.01 million tons in carbon emissions, and during 2019–2020, it led to a reduction of about 34.04 million tons in carbon emissions. In contrast, China showed a markedly different pattern. Neither the global financial crisis nor the COVID-19 pandemic reversed the income effect’s contribution to increasing emissions. As seen in the cumulative effects chart, China’s income effect has consistently driven up carbon emissions. This persistent impact can be partly attributed to China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2002, after which its GDP and trade volumes grew significantly. Many developed countries relocated pollution-intensive industries to China, contributing to the country’s rising carbon emissions [143]. According to observational data, excluding other factors, economic growth between 2005 and 2007 may have driven an average increase in carbon emissions of over 60%. In most years, the income effect’s contribution to rising emissions in China remained above 40%, and at times approached 80%, making it the most influential driver of carbon emission changes (Figure 12).

Overall, the structural effect across the BRICS countries has shown a weak positive (emission-increasing) impact on carbon emissions (Figure 13), with its share in influencing emissions remaining very limited and showing a declining trend in recent years. As seen in the figure, the structural effect is not a major factor driving carbon emissions in Russia, India, or China. Take China as an example. During the research period, the cumulative increase in carbon dioxide emissions brought about by the industrial structure was only 300 million tons, less than a quarter of the contribution of economic growth to the growth of carbon dioxide emissions (Figure 13). Take China as an example. During the research period, the cumulative increase in carbon dioxide emissions brought about by the industrial structure was only 300 million tons, less than a quarter of the contribution of economic growth to the growth of carbon dioxide emissions (Figure 13). This is likely because China’s overall industrial structure has not undergone major transformations during the study period. According to the 2023 Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development published by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the proportion of the tertiary industry, which has relatively low energy consumption and carbon emissions, in the national economy has been gradually increasing, from 32.8% in 1996 to 54.6% in 2023. However, the secondary industry, which has high energy consumption and carbon emissions, still holds a relatively important position, accounting for 38.3%. The substantial CO2 emissions from the secondary sector tend to offset the carbon reduction benefits brought about by structural adjustments [48]. As a result, although the structural effect’s contribution to emissions is not particularly pronounced, it still tends to act as a driving force behind emission increases.

Notably, in South Africa and Brazil, the structural effect has acted to suppress carbon emissions (Figure 13), with its cumulative impact strengthening over time. As the most affluent country in Africa, South Africa’s economy is predominantly service-based. According to April 2024 data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), services accounted for 67.8% of South Africa’s GDP in 2023, while industry contributed only 27.2%. Moreover, the manufacturing sector has shown a continued decline in its contribution to both economic growth and employment [144]. This structural shift is likely a key reason why South Africa’s structural effect has had a dampening impact on carbon emissions. Brazil’s economic structure has evolved in two main phases [145]. From 1950 to the mid-1980s, the country underwent a strong industrialization period, marked by robust GDP growth. However, from the mid-1980s to 2021, Brazil entered a phase of premature deindustrialization, with weak GDP growth averaging below the global economy by about one percentage point. This deindustrialization trend likely explains why the structural effect in Brazil has contributed to suppressing carbon emissions during the study period [146].

Overall, the intensity effect has an inhibitory effect on the growth of carbon emissions in the BRICS countries. This is mainly due to the relatively ideal performance of China, India, and Russia, which has affected the overall outcome. According to data from the World Bank, India’s economic structure is dominated by the service sector, which accounted for approximately 52% of its GDP in 2022, while manufacturing contributed only 14.7%. This service-oriented structure is likely a key reason why industrial development in India has not driven a sharp increase in carbon emissions. In Russia, the share of industry and manufacturing in GDP has shown a general downward trend over the past two decades. The value added by industry as a share of GDP declined from 33.92% in 2000 to 33.16% in 2021. This indicates that although Russia has a certain foundation in the industrial and manufacturing sectors, it may be affected by factors such as global industrial structure adjustment, the rising proportion of the service industry, and Russia’s economic diversification strategy. This is reflected in the intensity effect that inhibits the increase in carbon emissions.

As shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13, Brazil exhibits the weakest performance in terms of the intensity effect, which has clearly contributed to an increase in carbon emissions. This can be attributed to Brazil’s unique industrial and emissions structure. Unlike many countries where carbon emissions mainly stem from fossil fuel consumption, Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions primarily originate from deforestation and land-use changes related to agriculture [147]. On one hand, illegal and large-scale deforestation has significantly reduced the carbon sink capacity of the Amazon rainforest. On the other hand, rapid growth in the mining and agricultural sectors has transformed much of the cleared forest into soybean plantations and cattle pastures [148,149,150]. As a result, in Brazil’s case, most carbon emissions are not directly tied to increases in industrial output. The intensity effect, which is typically used to evaluate emissions per unit of economic output, may thus misleadingly underrepresent the emissions embedded in the agricultural value chain.

As shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, the fossil energy structure effect in BRICS countries has shown a slight suppressive impact on carbon emissions in recent years. Historically, coal, oil, and natural gas have remained the dominant sources of energy in BRICS nations, accounting for over 70% of total energy consumption. However, due to mounting climate change pressures and the need for sustainable development, BRICS countries have in recent years begun accelerating the development of renewable energy. According to the international think tank Global Energy Monitor (GEM), the report “Energy in the BRICS” forecasts that by the end of 2024, the share of coal, oil, and gas in power generation capacity across the BRICS nations will fall below 50%, potentially matching the pace of the EU and G7 countries [151]. Nonetheless, compared to EU countries, BRICS nations are at a relatively later stage of both economic and energy transitions. As a result, the impact of energy structure on emissions also lags behind. It is only since around 2015 that this effect has begun to show a consistent downward (emissions-reducing) trend. This timing likely corresponds with the adoption of the landmark Paris Agreement in 2015, which marked a new phase in global climate governance. The agreement reflected an unprecedented international consensus on sustainable development and green transformation, motivating BRICS countries to begin shifting toward cleaner energy sources.

5.3. New Findings on Driving Factors

In analyzing the driving factors behind carbon emission decoupling in EU and BRICS countries, a particularly interesting phenomenon emerges. In the cumulative effect charts of carbon emission drivers (Figure 7, Figure 9, Figure 11 and Figure 13), both the fossil energy structure effect (F) and the energy transition effect (T) display a nearly symmetrical pattern around the zero axis.

It is important to note that this symmetry is not exact in terms of absolute values, but rather reflects a mirrored trend in direction, peak points, and inflection moments. As mentioned in Section 3 of this study, the fossil energy structure effect represents the share and use of fossil fuels in a country’s total primary energy supply. A reduction in fossil fuel use typically suppresses carbon emissions and is reflected as a steadily accumulating negative value (below the zero axis). Conversely, the energy transition effect reflects the total amount of primary energy required to emit one unit of carbon, essentially how intensively energy is used. Since higher energy use promotes carbon emissions, this effect usually accumulates above the zero axis. When a country begins transitioning its energy system, it tends to replace fossil fuels with cleaner sources. When a country begins its energy transition, it is often manifested as starting to use more clean energy to replace fossil fuels. Therefore, for a country in the process of energy transition, when it uses a cleaner energy mix for production, the cumulative impact on carbon emissions changes and the impact of simultaneously reducing the use of fossil fuels must change in tandem and have opposite effects.

As highlighted in the study [152], substituting one energy source with a cleaner alternative does not necessarily lead to an overall decline in energy consumption. This is in line with our finding that the use of cleaner energy does not mean an absolute decrease in carbon emissions. This relationship is clearly reflected in the near symmetry between the fossil energy structure effect and the energy transition effect in the cumulative charts. However, the two effects do not perfectly cancel each other out. This is largely because no country has yet completely phased out fossil fuels. Therefore, the contribution effect of overall energy to carbon emissions represented by the energy transition effect is usually not fully offset by the reduction effect of fossil fuels. Still, this imperfect cancellation offers a useful and intuitive lens for assessing a country’s energy transition progress. When the cumulative chart shows that the positive contribution of the energy transition effect to emissions is significantly greater than the suppressive effect of reduced fossil fuel use, it suggests the transition is incomplete. Conversely, if the cumulative contribution of the energy transition effect is close to or even smaller than the mitigation effect of fossil fuel reduction, it indicates a more successful and effective energy transition.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study conducts a comparative analysis of the decoupling between economic output and CO2 emissions in the EU and BRICS countries from 1996 to 2023 using the Tapio decoupling model and LMDI decomposition analysis. The findings provide clear answers to the research questions initially posed.

First, our analysis reveals a stark divergence in decoupling pathways. The EU has, on average, achieved a state of strong decoupling, with carbon emissions declining at an annual rate of −1% alongside economic growth. In contrast, the BRICS bloc remains predominantly in a state of weak decoupling, characterized by an average annual emissions growth of 6.26%, where economic growth continues to drive carbon emissions upward, albeit at a slower rate. Significant internal heterogeneity exists within both blocs; for instance, Western and Northern EU members like Germany and Sweden show more consistent strong decoupling, while Eastern members like Poland lag. Among BRICS, China has progressed towards weak and occasionally strong decoupling, whereas South Africa and Brazil have frequently experienced expansive negative decoupling.

Second, the LMDI decomposition identifies distinct primary drivers for each bloc. In the EU, the intensity effect (I) is the most significant factor suppressing carbon emissions, underscoring the success of energy efficiency improvements and technological innovation. For BRICS, the income effect (Y) is the predominant driver promoting emissions growth, reflecting the carbon-intensive nature of their rapid economic expansion. The population effect (P) also exerts consistent upward pressure on emissions in BRICS, particularly in India and South Africa. A novel finding is the near-symmetrical relationship between the energy transition effect (T) and the fossil energy structure effect (F) in cumulative charts, offering a new lens to evaluate the progress and completeness of a country’s energy system transformation.

6.2. Policy Implications

The findings of this research have important policy implications.

In general, policies and strategies should be tailored to the specific drivers and development stages of each bloc. For BRICS, the critical challenge is to mitigate the carbon-intensive pressure from economic and population growth. This necessitates a fundamental shift towards green industrialization, accelerated industrial upgrading, and large-scale deployment of renewable energy infrastructure. Given their development stages and structural differences, BRICS countries should adopt differentiated strategies. China and India, as manufacturing hubs, should enforce stricter energy efficiency standards, promote green manufacturing, and adopt circular economy principles. Russia and South Africa, as resource-dependent economies, should implement carbon pricing mechanisms and environmental taxation to incentivize low-carbon innovation and diversification. Brazil should leverage its vast renewable base to become a green energy leader while simultaneously enforcing stringent policies against deforestation to address its unique emissions profile.

For the EU, the priority is to consolidate and accelerate its existing decoupling pathway by addressing internal disparities, with a focus on supporting Eastern member states in their energy transition and further deepening decarbonization across all sectors.

Furthermore, the contrasting yet complementary needs of the EU and BRICS present a significant opportunity for collaboration. Both blocs should strengthen cooperation under frameworks like the UNFCCC and BRICS platforms to establish a “Green Development Partnership”.

By implementing these differentiated yet synergistic strategies, both developed and developing economies can more effectively navigate their low-carbon transitions, avoiding the "pollute first, clean up later" path and collectively advancing global sustainable development.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has certain limitations that also point to avenues for future research. Firstly, the analysis relies on production-based (territorial) CO2 emissions data, which does not account for embodied carbon transfers via international trade. Given the deep trade links between the EU and BRICS, future research could employ multi-regional input–output (MRIO) models to analyze consumption-based footprints (e.g., material footprint or carbon footprint) for a more complete attribution of carbon responsibilities [28]. Secondly, the aggregate national-level analysis could be extended to the sectoral or industrial level to uncover the impact of energy-intensive industry distribution and restructuring. Future work could also integrate econometric techniques to explore the dynamic interactions and causal relationships between the driving factors identified by the LMDI decomposition. Lastly, while this study deepens our understanding of carbon emission decoupling, a direct comparison of decoupling behaviors across different environmental indicators (e.g., material footprint vs. CO2 emissions) is not explored in detail here. Our previous work has begun this comparison [27,28], but further exploration is needed to understand if decoupling in one domain translates to another. Thus, a future comparative analysis of decoupling behaviors across different environmental indicators, such as material footprint versus CO2 emissions, would offer deeper insights into sustainable resource management.

Author Contributions

Q.X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Funding acquisition, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and editing. S.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Reviewing and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Reviewing. F.C.: Conceptualization and methodology, Reviewing and editing, Supervision, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Scholarship Council, grant number 202306490005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santopietro, L.; Solimene, S.; Lucchese, M.; Di Carlo, F.; Scorza, F. An economic appraisal of the SE (C) AP public interventions towards the EU 2050 target: The case study of Basilicata region. Cities 2024, 149, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Y.; Qin, B.; Chen, G.; Bao, L.; Long, X. Study on the response and prediction of SDGs based on different climate change scenarios: The case of the urban agglomeration in central Yunnan. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hu, J.; Afshan, S.; Irfan, M.; Hu, M.; Abbas, S. Bridging resource disparities for sustainable development: A comparative analysis of resource-rich and resource-scarce countries. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.A. Decoupling: A Conceptual Overview; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Directorate for Food: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Indicators to measure decoupling of environmental pressure from economic growth. OECD 2002, 2002, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tapio, P. Towards a theory of decoupling: Degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp. Policy 2005, 12, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, C.; Gatto, A. Policy, regulation effectiveness, and sustainability in the energy sector: A worldwide interval-based composite indicator. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, A.M.; García-Freites, S.; Walsh, C.; Mukoro, V.; Aberilla, J.M.; April, A.; Kuriakose, J.; Gaete-Morales, C.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Mander, S. Advancing sustainable development goals through energy access: Lessons from the global south. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, P.A.; Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. A review of renewable energy sources, sustainability issues and climate change mitigation. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Payne, J.E. Energy consumption and growth in South America: Evidence from a panel error correction model. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I. Economic growth and energy. Encycl. Energy 2004, 2, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.; Fung, I.; Lacis, A.; Rind, D.; Lebedeff, S.; Ruedy, R.; Russell, G.; Stone, P. Global climate changes as forecast by Goddard Institute for Space Studies three-dimensional model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1988, 93, 9341–9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; Jones, M.W.; O’sullivan, M.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Peters, G.P.; Peters, W.; Pongratz, J.; Sitch, S.; Le Quéré, C. Global carbon budget 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1783–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmapriya, N.; Gunawardena, V.; Methmini, D.; Jayathilaka, R.; Rathnayake, N. Carbon emissions across income groups: Exploring the role of trade, energy use, and economic growth. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadeyan, O.J.; Muthivhi, J.; Linganiso, L.Z.; Deenadayalu, N. Decoupling economic growth from carbon emissions: A transition toward low-carbon energy systems—A critical review. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 1076–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Green Deal: Delivering on Our Targets; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, F.; Tanveer, A.; Karim, S.; Dowling, M. The decoupling dilemma: Examining economic growth and carbon emissions in emerging economic blocs. Energy Econ. 2024, 138, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorember, P.T.; Gbaka, S.; Işık, A.; Nwani, C.; Abbas, J. New insight into decoupling carbon emissions from economic growth: Do financialization, human capital, and energy security risk matter? Rev. Dev. Econ. 2024, 28, 827–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papież, M.; Śmiech, S.; Frodyma, K. Does the European Union energy policy support progress in decoupling economic growth from emissions? Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.; Cascetta, F.; Nardini, S. Analysis of the carbon emissions trend in European Union. A decomposition and decoupling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-lami, A.; Török, Á. Decomposition of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in Hungary: A case study based on the Kaya identity and LMDI model. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2025, 53, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Han, X.; Wang, Q. Do technical differences lead to a widening gap in China’s regional carbon emissions efficiency? Evidence from a combination of LMDI and PDA approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abam, F.I.; Inah, O.I.; Nwankwojike, B.N. Impact of asset intensity and other energy-associated CO2 emissions drivers in the Nigerian manufacturing sector: A firm-level decomposition (LMDI) analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, C.H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Bhutta, M.S.; Li, Z.; Ni, W. LMDI decomposition of coal consumption in China based on the energy allocation diagram of coal flows: An update for 2005–2020 with improved sectoral resolutions. Energy 2023, 285, 129266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, P.; Yang, L. The application and evaluation of the LMDI method in building carbon emissions analysis: A comprehensive review. Buildings 2024, 14, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Liu, K. Decomposition analysis of natural gas consumption in Bangladesh using an LMDI approach. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 40, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Cao, F. Decomposition of factors affecting copper consumption in major countries in light of green economy and its trend characteristics. Resour. Policy 2024, 98, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Cao, F.; Yang, Y. Material footprint and economic growth decoupling toward green development: Comparative analysis of United States, the European Union and the BRICS countries. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 238, 108733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenich, C.; Magraw, D.; Rowley, A.; Rubin, J.W. The Kyoto protocol to the United Nations framework convention on climate change. Am. J. Int. Law 1998, 92, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Paris Agreement. In Report of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (21st Session, 2015: Paris); Retrived December 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Fang, F.; Song, M. The influences of aging population and economic growth on Chinese rural poverty. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, M.; Zhao, R. Analyzing the decoupling relationship between marine economic growth and marine pollution in China. Ocean. Eng. 2017, 137, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Li, T.; Wang, A.; Liu, G.; Guo, X. Decoupling analysis of economic growth and mineral resources consumption in China from 1992 to 2017: A comparison between tonnage and exergy perspective. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Liu, S.; Xi, P. Long-term economic growth: Leveraging natural resources for sustainable economic growth and energy transition. Resour. Policy 2024, 92, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, L.C.; Kaneko, S. Decomposing the decoupling of CO2 emissions and economic growth in Brazil. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Environmental Indicators: Development, Measurement and Use; OECD: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, J.P.; Román-Collado, R.; Cansino, J.M. Key driving forces of energy consumption in a higher education institution using the LMDI approach: The case of the Universidad Autónoma de Chile. Appl. Energy 2024, 372, 123797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, X. Tracking China’s CO2 emissions using Kaya-LMDI for the period 1991–2022. Gondwana Res. 2024, 133, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Can, S.d.I.R.; Price, L. Sectoral trends in global energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1386–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadell, J.G.; Ciais, P.; Dhakal, S.; Dolman, H.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gurney, K.R.; Held, A.; Jackson, R.B.; Le Quere, C.; Malone, E.L. Interactions of the carbon cycle, human activity, and the climate system: A research portfolio. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsu, F.; Adams, S. Energy consumption, finance, and climate change: Does policy uncertainty matter? Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singpai, B.; Wu, D.D. An integrative approach for evaluating the environmental economic efficiency. Energy 2021, 215, 118940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, J.; Ferreira, J.; Santibanez-González, E. New insights into decoupling economic growth, technological progress and carbon dioxide emissions: Evidence from 40 countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, R.; Van den Bergh, J.C. Comparing structural decomposition analysis and index. Energy Econ. 2003, 25, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.; Jimoh, A.; Kholopane, P.A. Assessing the energy potential in the South African industry: A combined IDA-ANN-DEA (index decomposition analysis-artificial neural network-data envelopment analysis) model. Energy 2013, 63, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, J.; Ma, W.; Ma, H.; Farajallah, M. Decomposing manufacturing CO2 emission changes: An improved production-theoretical decomposition analysis based on industrial linkage theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W.; Zhang, F.Q. A survey of index decomposition analysis in energy and environmental studies. Energy 2000, 25, 1149–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Da, Y.-B. The decomposition of energy-related carbon emission and its decoupling with economic growth in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W. Decomposition analysis for policymaking in energy: Which is the preferred method? Energy Policy 2004, 32, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Su, M. Decomposition and decoupling analysis of carbon emissions from economic growth: A comparative study of China and the United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, J.; Liu, L. Influencing factors of carbon emissions in transportation industry based on CD function and LMDI decomposition model: China as an example. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 90, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Assessment of land use change and carbon emission: A Log Mean Divisa (LMDI) approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ruiz, G.; Mena-Nieto, A.; García-Ramos, J.E. Is India on the right pathway to reduce CO2 emissions? Decomposing an enlarged Kaya identity using the LMDI method for the period 1990–2016. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Jiang, W.; Gao, Z.; Liu, T. Influencing factors of carbon emissions from final consumption based on LMDI decomposition and Tapio index: The EU 28 as an example. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 4884–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, J.; Ashimedua, O.; Okoye, O. Decomposition and Decoupling Analysis of Nigeria Industrial Emission from Lmdi And Tapio Models: Case Study of the cement Industry. J. Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]