1. Introduction

Human capital management has evolved considerably since the 1980s, becoming an essential practice for organizational success and sustainability [

1]. Internationally recognized institutions such as the World Federation of People Management Associations (WFPMA), the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) have implemented personnel management strategies that have enabled them to maintain a competitive advantage in their respective markets [

2]. Attention to the biopsychosocial component of employees is considered a key factor in optimizing productivity and fostering a healthy organizational environment [

1].

In recent decades, sustainable human resource management (Sustainable HRM) has taken on a central role in promoting responsible organizational development aligned with global sustainability. This approach is characterized by the integration of environmental sustainability, employee well-being, and social equity principles within human talent management [

3]. Recent literature indicates that the implementation of sustainable human resource practices contributes to reducing environmental impacts, retaining talent, and fostering resilient and ethical organizational cultures [

4,

5]. In this way, the sustainable management of human capital not only enhances motivation and a sense of belonging but also drives social innovation by promoting work environments grounded in cooperation, creativity, and the holistic well-being of employees.

This connection between Sustainable HRM and social innovation constitutes a key mechanism for understanding how human resource management can directly influence organizational sustainability. Social innovation is defined as the generation of new, collaborative, and sustainable solutions to address social and environmental needs [

6,

7]. In this context, sustainable human resource practices act as a catalyst by fostering employee commitment, continuous learning, and active participation in transformative processes [

8]. When organizations integrate these values into their internal culture, their capacity for innovation, social cohesion, and long-term sustainable impact is strengthened.

In the current context, rural organizations play a significant role in the economic and social development of their communities, particularly in Latin America, where these enterprises face challenges related to access to formal markets and the optimization of local resources [

9]. Organizational sustainability, understood as the balanced integration of economic, social, and environmental dimensions, has become a key requirement for global competitiveness [

10]. However, in regions such as southern Sonora, Mexico, research addressing the relationship between social innovation and sustainability in this type of organization remains scarce, representing an important gap in the literature.

The application of social innovation in rural organizations has demonstrated its potential to generate economic and social value by encouraging community participation, job creation, and the development of local leadership [

9,

11,

12]. Several studies highlight that social innovation directly influences the sustainability of rural enterprises by promoting the adoption of responsible practices, community engagement, and the strengthening of social capital [

11,

12,

13]. Likewise, its implementation generates economic and social value, fosters local leadership, and contributes to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda [

14,

15]. In this sense, social innovation functions as a driver of organizational transformation, linking business sustainability with the creation of collective well-being and community resilience [

16,

17].

At the international level, social innovation has been used as a tool to address global challenges such as economic crises, inequality, and climate change, encouraging the adoption of more efficient processes, the responsible use of resources, and the integration of innovative technologies [

11,

18,

19]. At the national level, Mexico has promoted public policies and programs that foster social innovation and corporate responsibility as tools for competitiveness and sustainability [

20,

21]. In the case of Sonora, the adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices and the modernization of processes through organizational innovation have enabled advances in productivity, labor inclusion, and social well-being [

22,

23]. These efforts, combined with sustainable talent management, strengthen the capacity of rural organizations to adapt to economic and environmental change.

During the theoretical review on social innovation and sustainability at the state level, it was identified that research on these topics remains limited, and studies applied at the local level are even more scarce. Therefore, based on the foregoing, the following research question is proposed:

What is the effect of the dimensions of social innovation on the sustainability of rural organizations in southern Sonora?

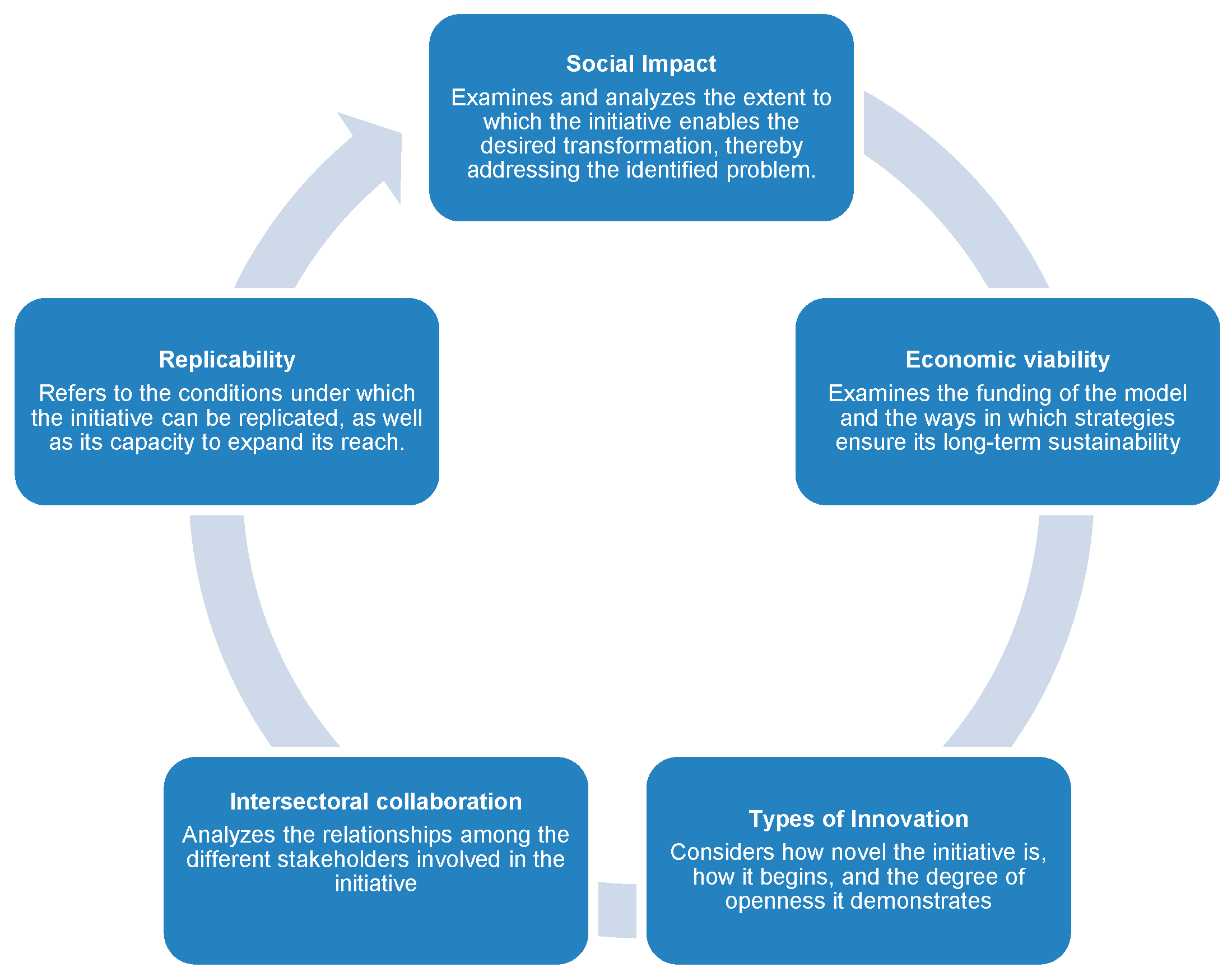

In this context, the present study aims to analyze the effect of the dimensions of social innovation on the sustainability of rural organizations, considering the mediating role of sustainable human resource management. This research seeks to provide theoretical and practical evidence that contributes to the design of strategies that strengthen social innovation, enhance organizational sustainability, and promote the economic, social, and environmental well-being of the region (see

Figure 1).

From this question, the following hypotheses are formulated:

The relationship between social innovation and sustainability can be theoretically explained through the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) approach and Social Capital Theory (SCT). The TBL approach emphasizes the integration of economic, social, and environmental dimensions as essential pillars of organizational sustainability [

24,

25]. In turn, SCT highlights the importance of trust, cooperation, and shared values among social actors to facilitate innovative practices that drive sustainable development [

26,

27]. Within this framework, social innovation functions as a mechanism that enables rural organizations to develop responsible, collaborative, and adaptive solutions to local challenges, thereby strengthening their long-term sustainability.

General Hypothesis

Social innovation has a positive and significant effect on the sustainability of rural organizations in southern Sonora. Organizational sustainability is understood as the ability of enterprises to generate economic, environmental, and social progress for both current and future generations [

17]. In this regard, social innovation enables rural organizations to integrate responsible practices that strengthen their resilience and competitiveness [

22,

28].

H1. From the perspective of the Triple Bottom Line, social innovation reinforces the social dimension of sustainability by addressing local needs, improving quality of life, and strengthening community well-being [22]. Therefore, the social impact dimension is expected to have a positive and significant effect on the sustainability of rural organizations in southern Sonora. H2. Economic viability ensures that organizations can maintain stable operations while adopting socially and environmentally responsible practices. Following the TBL framework, this dimension supports financial sustainability and value creation, reinforcing long-term organizational stability [25,28]. Therefore, it is proposed that economic viability has a positive and significant effect on organizational sustainability. H3. The type of innovation implemented influences an organization’s ability to adapt and generate social value. Based on the approach of innovation systems, flexible and inclusive innovation models promote resilience and sustainability in dynamic environments [29]. Thus, it is proposed that this type of innovation has a positive and significant effect on the sustainability of rural organizations. H4. According to Social Capital Theory, intersectoral collaboration fosters relationships based on trust and resource-exchange networks that strengthen organizational learning and sustainability [27,30,31]. Although theory suggests that intersectoral collaboration should enhance organizational sustainability through the creation of trust-based networks and shared resources, the empirical findings of this study revealed a nonsignificant effect. This result may be explained by contextual factors such as limited local resources and low interorganizational trust, which often constrain the formation of strong collaborative networks in rural regions. H5. The ability to replicate innovative practices supports regional development and organizational learning. The OECD [32] emphasizes that the diffusion of successful innovation models is essential to ensuring the growth and sustainability of organizations. Therefore, replicability is expected to have a positive and significant effect on the sustainability of rural organizations in southern Sonora. 2. Materials and Methods

The present study is grounded in a positivist paradigm characterized by its quantitative approach, aimed at obtaining precise, measurable, and replicable results supported by scientific rigor. This paradigm allows for the systematization, comparison, and verification of knowledge, as well as the identification of causes and the establishment of generalizations based on observed phenomena [

33]. The research follows a quantitative and correlational design focused on analyzing the relationship between the independent variable, social innovation, and the dependent variable, sustainability, in organizations located in the municipality of Cajeme.

Currently, the PLS technique has gained wide acceptance in social science research and is therefore used in explanatory and predictive studies [

34,

35]. The present study employs a formative model, and according to [

35], the PLS technique follows a measurement approach that aligns with the characteristics of this research, allowing for the effective assessment of validity and relevance. Likewise, it offers substantial flexibility regarding data distribution, measurement scales, and sample size.

A five-point Likert-scale questionnaire consisting of 34 items was administered to a representative sample. The data collected were subjected to statistical analysis to test the proposed hypotheses [

36]. For the structural equation modeling analysis, SmartPLS 4 Professional (SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) was used. Furthermore, the research is classified as a non-experimental cross-sectional study, as data collection was conducted at a single point in time without deliberate manipulation of the variables, allowing for the determination of how one variable influences the other [

36,

37].

2.1. Participants

For data collection, the study was conducted in southern Sonora, involving various organizations engaged in different economic activities and located in rural areas, specifically in the communities of Esperanza, Cócorit, Providencia, Pueblo Yaqui, and San Ignacio Río Muerto. To ensure that participants adequately represented the target population, a non-probabilistic sampling method was used. The main selection criterion was that the organizations had a rural character and provided services or marketing products, regardless of their sector or size [

36].

The sample was selected based on convenience, meaning that participants were chosen according to their accessibility and availability to the researcher [

37]. In total, questionnaires were administered to 200 participants, with the expectation that the results obtained could be generalized to the target population, following the principles outlined by [

33]. For future studies, it is recommended and considered important to use stratified sampling, which allows the population to be divided into different subgroups, ensuring their adequate representation and enabling a more detailed understanding of the population under study [

38].

2.2. Instrument

The data collection instrument used in this research was structured using a five-point Likert scale, where a value of one (1) corresponds to “strongly disagree” and a value of five (5) to “strongly agree”. The instrument consisted of 34 items distributed across two main variables. The first variable, Social Innovation (SI), comprised five dimensions and a total of 20 items. The second variable, Sustainability, included 14 items [

39]. Once the information was collected, the reliability of the instrument was assessed through Cronbach’s Alpha analysis, yielding positive and significant results. The closer the obtained value is to one (1), the greater the reliability of the instrument, thus confirming the internal consistency of the evaluated variables [

39,

40] (see

Table 1).

2.3. Pilot Test for Application for Data Collection

A preliminary application of the instrument was conducted to validate its reliability and assess the variables of social innovation and sustainability, adapted to the context of rural organizations located in the communities of Cócorit, Esperanza, Providencia, San Ignacio Río Muerto, and Pueblo Yaqui, in southern Sonora. The application was carried out in person, with the informed consent of all participants.

The process began by contacting several organizations to request authorization to administer the questionnaire, receiving a positive response in most cases. Additionally, some questionnaires were applied to collaborators outside their workplaces, who voluntarily agreed to participate. The response rate was satisfactory, with a total of 40 participants completing the instrument in full, providing valuable information for the preliminary validation of the questionnaire. The importance of the pilot test is associated with improving the validity, reliability, and feasibility of the instrument.

2.4. Procedure

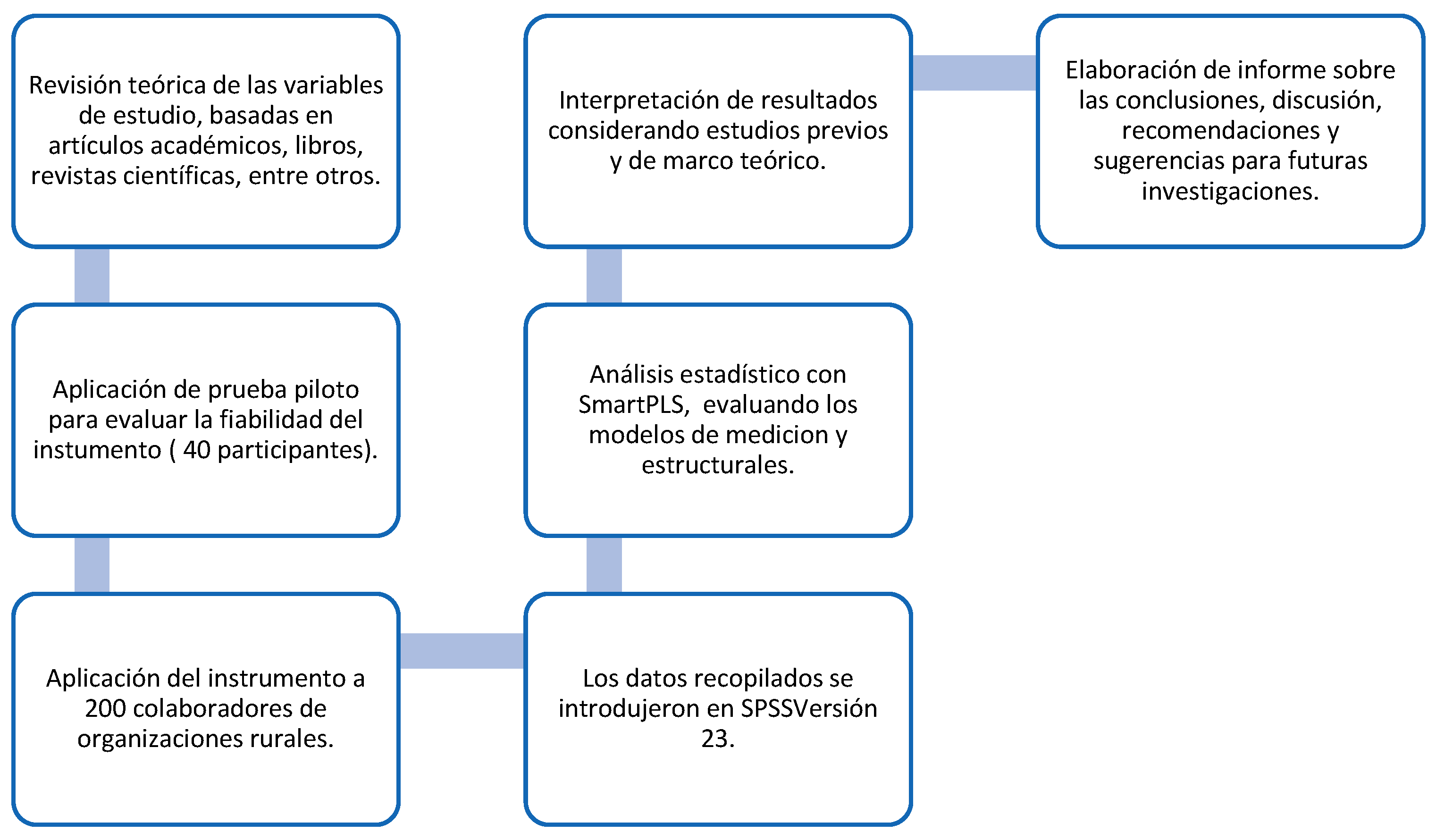

The research process was carried out in several stages. First, a pilot test was applied to 40 active collaborators to evaluate the reliability of the instrument. Once validated, the final questionnaire was administered to 200 collaborators from different rural organizations located in southern Sonora.

The collected data were entered into a database created with SPSS version 23, which included both sociodemographic variables and questionnaire responses. Subsequently, statistical analyses were conducted using SmartPLS 4 Professional, evaluating both the measurement and structural models. Finally, the results were reviewed and interpreted considering previous studies and the theoretical framework. This process led to the development of a comprehensive report from which the conclusions, discussion, recommendations, and suggestions for future research were derived (see

Figure 2).

3. Results

Based on the preliminary findings, a descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic data was conducted to characterize the study participants in terms of gender, age, job position, and length of employment. The results revealed a balanced participation between men and women. Regarding job positions, participants included employees, supervisors, managers, business owners, and sales personnel, with a greater representation of supervisory staff. In terms of age, most participants were between 20 and 50 years old, while approximately 70% reported a length of employment ranging from one month to ten years within the organization. These results provide a general overview of the profile of the rural collaborators included in this study (see

Table 2).

Regarding the results obtained for the study variables, the presentation of social innovation and sustainability is summarized in

Table 3.

The results indicate that the responses for the dimensions of the social innovation variable, as well as for sustainability, fall within a medium range, with values close to three (3).

3.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

The measurement model allows for the analysis of relationships between constructs and indicators using various metrics, enabling the verification of their reliability and supporting the proposed model [

41].

3.2. Internal Consistency

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, with 0.70 considered the minimum acceptable value [

42]. Values below this threshold indicate low consistency, while values above 0.90 may suggest item redundancy. A composite reliability ≥ 0.7 is acceptable, and ≥0.8 is considered ideal [

43]. In this study, both consistency indicators meet the established criteria, as all values exceed 0.8, demonstrating that the internal consistency tests are significant and reliable (see

Table 4).

3.3. Convergent Validity

Once the data were obtained, they were processed using SPSS, allowing the reliability of the variables to be assessed through Cronbach’s alpha analysis. The closer the value is to 1, the higher the reliability of the instrument [

39,

40]. In the present study, the results indicated high reliability for both dimensions. The social innovation dimension achieved a value of 0.949, while the sustainability dimension reached 0.860. Furthermore, the complete instrument yielded a value of 0.951, indicating that the scale is highly reliable and suitable for measuring the variables (see

Table 5).

3.4. Discriminative Validity

Discriminant validity refers to the ability of a construct to measure exclusively what it is intended to measure, distinguishing it from other related constructs. For a measure to be valid, it must show strong correlations with its own indicators while exhibiting lower correlations with other constructs [

44]. Three main criteria are considered for its evaluation: Fornell–Larcker criterion, cross-loadings, and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

According to the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct must exceed the shared variance with other constructs. In other words, the square root of the AVE for each variable should be greater than its correlations with other constructs [

35]. After analyzing these correlations, it was verified that each AVE is indeed higher than the squared correlations between variables, thereby confirming the discriminant validity of the model (see

Table 6).

Regarding cross-loadings, this criterion was also met, as each item associated with a construct showed higher values when compared to the corresponding values of other constructs. In other words, the items within each dimension presented the highest loadings on their respective constructs [

35]. This procedure ensures discriminant validity by demonstrating that each item correlates more strongly with its own construct than with other constructs evaluated in the model (see

Table 7).

Regarding the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, this criterion was also satisfied, as no correlation between variables exceeded 1. For HTMT to be reliable, all values must be below 1 for each established criterion [

35] (see

Table 8).

3.5. Structural Model Evaluation

Once the reliability and validity of the measurement model were verified, the next step involved evaluating the structural model. This evaluation considered indicators such as collinearity levels using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), the coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and path coefficients.

3.6. Collinearity

Since the objective of this study was to conduct a statistical analysis to determine the relationships between variables, collinearity among constructs was assessed using VIF. This analysis provides information on potential multicollinearity risks. VIF values should not exceed 5.0, while values above 2.0 are considered within the minimally acceptable range [

45]. In this study, no variable exceeded these thresholds, indicating that there is no collinearity risk and that the results are reliable for structural analysis (see

Table 9). However, a more stringent criterion recommends using a VIF < 3.3 to ensure greater statistical safety [

46,

47]. The results show that most values ranged from 2.663 to 2.965, apart from intersectoral collaboration, which presented a value of 3.726, approaching the threshold of 4. It is important to note that this does not indicate construct overlap; rather, because the items belong to the same variable, they tend to be identified as highly similar.

3.7. Coefficient of Determination (R2) and Adjusted R2

The coefficient of determination measures the predictive capacity of the estimated model. Values should be ≥ 0.10 [

48]. According to the results, R

2 for sustainability is 0.595 (approximately 59%), and the adjusted R

2 is 0.585 (approximately 58%) (see

Table 10).

3.8. Effect Size

Effect size was calculated to interpret the results and compare them with other studies. According to established thresholds, effect sizes can be classified as small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large (0.35) [

49]. The results show that the effect of social impact, replicability, type of innovation, and economic viability is small, whereas the effect of intersectoral collaboration on sustainability is negligible (see

Table 11).

3.9. Path Coefficient

To determine the significance of the relationship between the dependent variable (sustainability) and the independent variable (social innovation), path coefficients were examined. These coefficients indicate the relationship between the dimensions of social innovation and sustainability. The following classification is used: imperceptible (0.0 < β ≤ 0.09), perceptible (0.10 < β ≤ 0.15), considerable (0.16 < β ≤ 0.19), important (0.20 < β ≤ 0.29), strong (0.30 < β ≤ 0.50), and very strong (β > 0.50) [

50]. The results indicate that intersectoral collaboration is imperceptible, social impact, replicability, and economic viability are important, and type of innovation is considerable (see

Table 12).

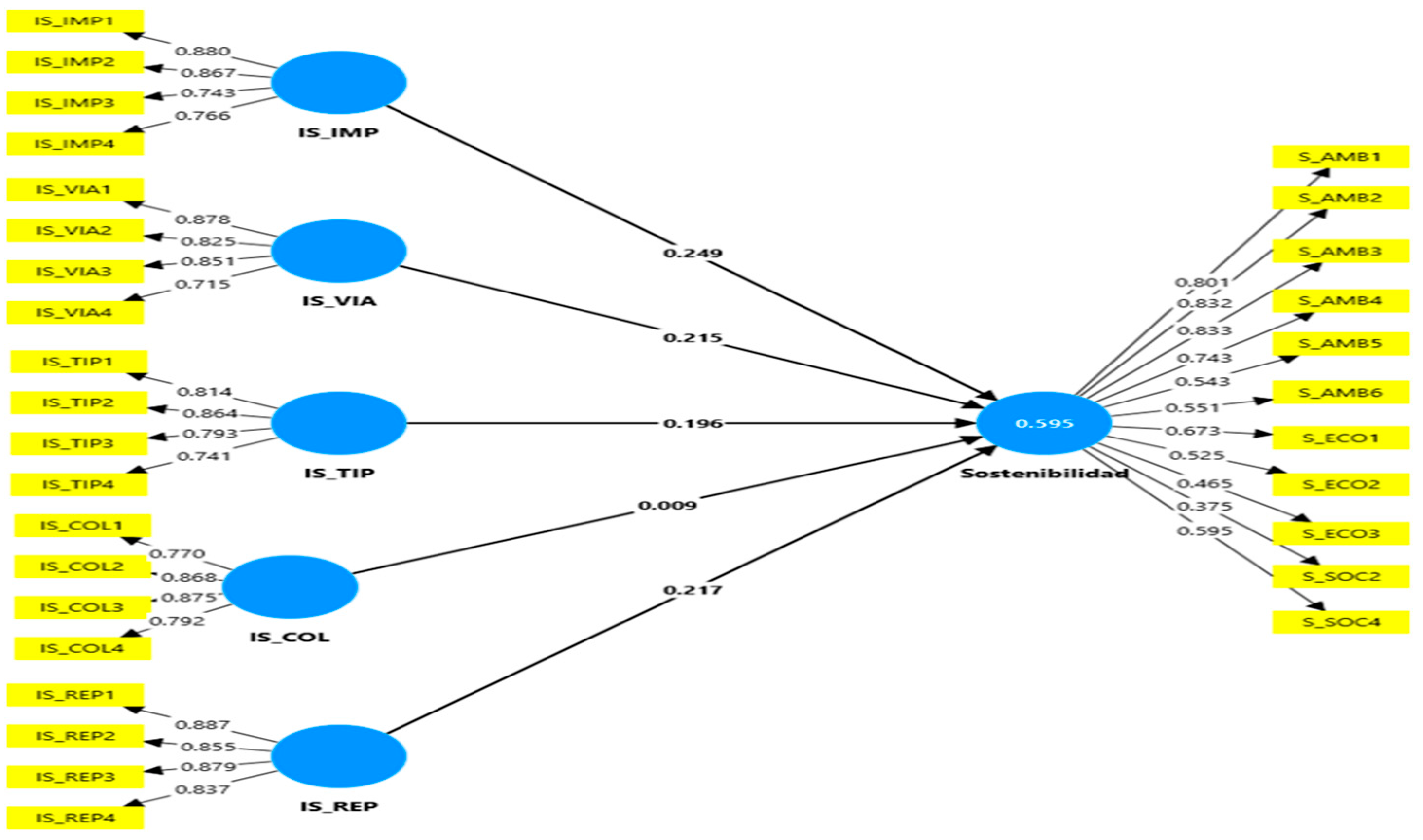

In

Figure 3, the structural model is presented. The model explains 59.5% of the variance in sustainability. It is classified as reflective, as the latent variable acts as the cause of the observed measures [

34]. By analyzing the Beta coefficients (β), which allow for comparison of the relative influence of each construct on the dependent variable, social impact shows the greatest effect on sustainability (β = 0.249), followed by replicability (β = 0.217), economic viability (β = 0.215), type of innovation (β = 0.196), and finally intersectoral collaboration (β = 0.009). These results identify which dimensions of social innovation have the strongest influence on sustainability in the studied organizations.

Q

2 is the measure used to evaluate the extent to which a statistical model can predict outcomes. According to [

46,

47,

51], the values are interpreted as follows: Q

2 ≤ 0 indicates no predictive power; 0.02 ≤ Q

2 < 0.15 indicates low predictive power; 0.15 ≤ Q

2 < 0.35 indicates medium predictive power; and Q

2 ≥ 0.35 indicates high predictive power. Therefore, the model demonstrates high predictive relevance (0.553), meaning that it correctly predicts the values of the variables (see

Table 13).

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) is a fit index used to measure the average differences between the correlations observed in the data and those predicted by the statistical model. Lower SRMR values indicate a better fit; however, values below 0.088 are also considered acceptable. Therefore, it can be concluded that the model proposed in this study exhibits an adequate fit (see

Table 14).

After evaluating the previous results, the next step involved verifying the research hypotheses, of which five out of six were accepted, with only H4 (intersectoral collaboration) being rejected. Using Student’s

t -statistics and

p-values, it is possible to determine the beta coefficients of the model and their statistical significance [

45]. In this study, hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H5, and Hi presented

t -values ≥ 2.0, which, according to the literature, indicates statistical significance.

Regarding the

p-value, obtained through the Bootstrap procedure in the PLS-SEM software, the following classification criteria were applied:

p ≤ 0.05 (significant),

p ≤ 0.01 (highly significant), and

p ≤ 0.001 (very highly significant). Following these criteria, it was confirmed that hypotheses Hi (very highly significant), H1 (very highly significant), H2 (highly significant), H3 (significant), and H5 (significant) were accepted, while H4 was rejected as its value fell outside the established significance range. Similarly, the analysis of the Path coefficient indicates that only H4 was discarded, being considered imperceptible, whereas the remaining hypotheses demonstrated a positive effect on the sustainability dimensions of rural organizations in southern Sonora, confirming their relevance and statistical significance (see

Table 15).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to analyze the effect of the dimensions of social innovation on sustainability in rural organizations in southern Sonora. The results showed that hypotheses Hi, H1, H2, H3, and H5 were accepted, demonstrating a positive effect, whereas H4, related to intersectoral collaboration, was rejected due to insufficient evidence of effective interaction among different stakeholders. The findings indicate that social innovation contributes to organizational well-being and the strengthening of sustainability, encompassing economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Specifically, the rural organizations analyzed, mostly developing SMEs, exhibited neutral levels in the implementation of social projects, economic management, and the use of technology for productivity. Likewise, the replicability of initiatives and collaboration with other sectors remained limited, consistent with previous studies highlighting challenges in financing, resistance to change, and lack of intersectoral support [

48,

52].

Likewise, it is inferred that the effect of the dimensions is small, which may be related to the characteristics of the collaborators and organizations under study. In this case, they are micro and small enterprises with few employees, where management typically falls on the owner, who simultaneously assumes multiple roles within the business. Their capital depends on the owner, they are geographically located in highly limited areas, and they face multiple resource constraints.

According to [

53], it is important to note that creating shared value generates both social and economic benefits for organizations. In this context, when rural organizations support each other and work collaboratively, they positively influence one another because they focus on achieving common objectives and providing mutual support, even when they are competitors. In addition, shared value practices help care for employees and clients, improving their quality of life through energy-efficient consumption, process optimization, and enhanced products and services. In this sense, ref. [

54,

55] propose that implementing the shared value model allows organizations to generate economic gains while simultaneously addressing environmental and social challenges. This is achieved by reconsidering the product and market in which they operate, redefining productivity, and creating clusters among rural organizations that enable continuous progress.

On the other hand, Elkington’s Triple Bottom Line model describes how companies can integrate economic, environmental, and social dimensions. In this case, the people dimension refers to achieving social equity, respecting human rights, and understanding the impact on rural communities. The planet dimension relates to responsible resource use, recycling, and addressing climate change. Finally, the profit dimension encompasses the organizational sustainability, profitability, and green innovation that characterize each enterprise [

55].

Regarding sustainability, the neutral results reflect a moderate participation of these organizations in projects benefiting society, resource optimization, fund management, and environmental care. This aligns with the literature emphasizing the need to balance economic, social, and environmental dimensions to achieve comprehensive sustainability [

10,

21,

56]. Moreover, social innovation is perceived as a mechanism that, when implemented ethically, fosters organizational adaptation to global changes, enhances productivity, and contributes to employee well-being [

22,

57].

Despite these positive outcomes, areas of opportunity were identified for strengthening intersectoral collaboration, which focuses on the joint work of actors from the private sector, the public sector, and civil society. Collaboration across sectors is essential because many challenges are difficult to address individually, and it is also important to implement solutions that are effective in the long term. This dimension is related to the support provided to university communities to develop academic projects or internships in rural areas, the collaboration networks established with businesses and social groups, and the participation of the community in the proposed initiatives. Future research could explore strategies to facilitate integration among private, public, and community organizations, as well as assess the impact of social innovation in companies of varying sizes and regions, aiming to expand knowledge on rural sustainability and its relationship with social innovation.

In summary, this study demonstrates that social innovation has a positive effect on sustainability in rural organizations, although greater development in collaboration, social participation, and replicability strategies is required to consolidate more sustainable and long-term results.

5. Conclusions

The research findings confirmed that the applied instrument presents high reliability, validated through Cronbach’s Alpha, and that the statistical analyses conducted using SPSS Version 23 and SmartPLS V.4.0 are consistent for evaluating the study variables. Regarding the impact of the dimensions of social innovation on sustainability, social impact was identified as having the greatest influence, which is related to the fact that the organizations under study implement projects that generate processes contributing to societal transformation. They also assess these projects, tend to participate in external social movements that benefit the community, and provide support to other institutions, organizations, and associations that work toward social change. This was followed by replicability, economic viability, type of innovation, and finally, intersectoral collaboration, which showed only a minimal effect. Organizations face constant environmental changes, making social innovation a key strategy for improving competitiveness, generating employment, optimizing infrastructure, and promoting local economic growth. To ensure sustainability, it is essential that social innovation be applied strategically and oriented toward effective projects that respond to community needs and enhance the capacity of organizations to deliver products and services sustainably.

The relevance of this study provides specific information that allows decision-makers to design strategies and programs that address the challenges faced by rural communities. Furthermore, the findings demonstrate the importance of government involvement in developing public policies aimed at mitigating the needs of the rural sector, promoting equity, improving quality of life, and fostering sustainable economic development.

Regarding the limitations of this study, one is the regional scope, as some organizations located in rural areas of southern Sonora were unable to participate due to security concerns at the time, which limited the number of participants. Another limitation relates to the use of cross-sectional data, as the instruments were applied at a single point in time; therefore, this study establishes correlations but not causal relationships.

Social innovation is a process that generates value and is essential for community participation, allowing citizens to exchange ideas and values and connecting with their shared responsibility to make decisions as members of their organizations. Rural community members are inclined to seek cultural change and collaborate through creativity and teamwork. This ensures that when actions aligned with clear objectives are implemented—actions designed to promote diverse strategies and plans for social innovation—citizens are willing to cooperate [

57,

58].

In conclusion, social innovation is crucial for achieving sustainability in rural communities. It operates through the implementation of solutions that enhance equity, resilience, and well-being while respecting local social and cultural values. None of this would be possible without the active participation of community members. Strengthening their capacity to adapt to economic, social, and environmental challenges is essential to sustaining these communities. Likewise, government–community collaboration is necessary to generate employment and initiate projects that positively impact rural regions and their inhabitants through the development of public policies and the management of rural enterprises.