A Numerical Investigation on the Performance and Sustainability Analysis of Conventional and Finned Air-Cooled Solar Photovoltaic Thermal (PV/T) Systems

Abstract

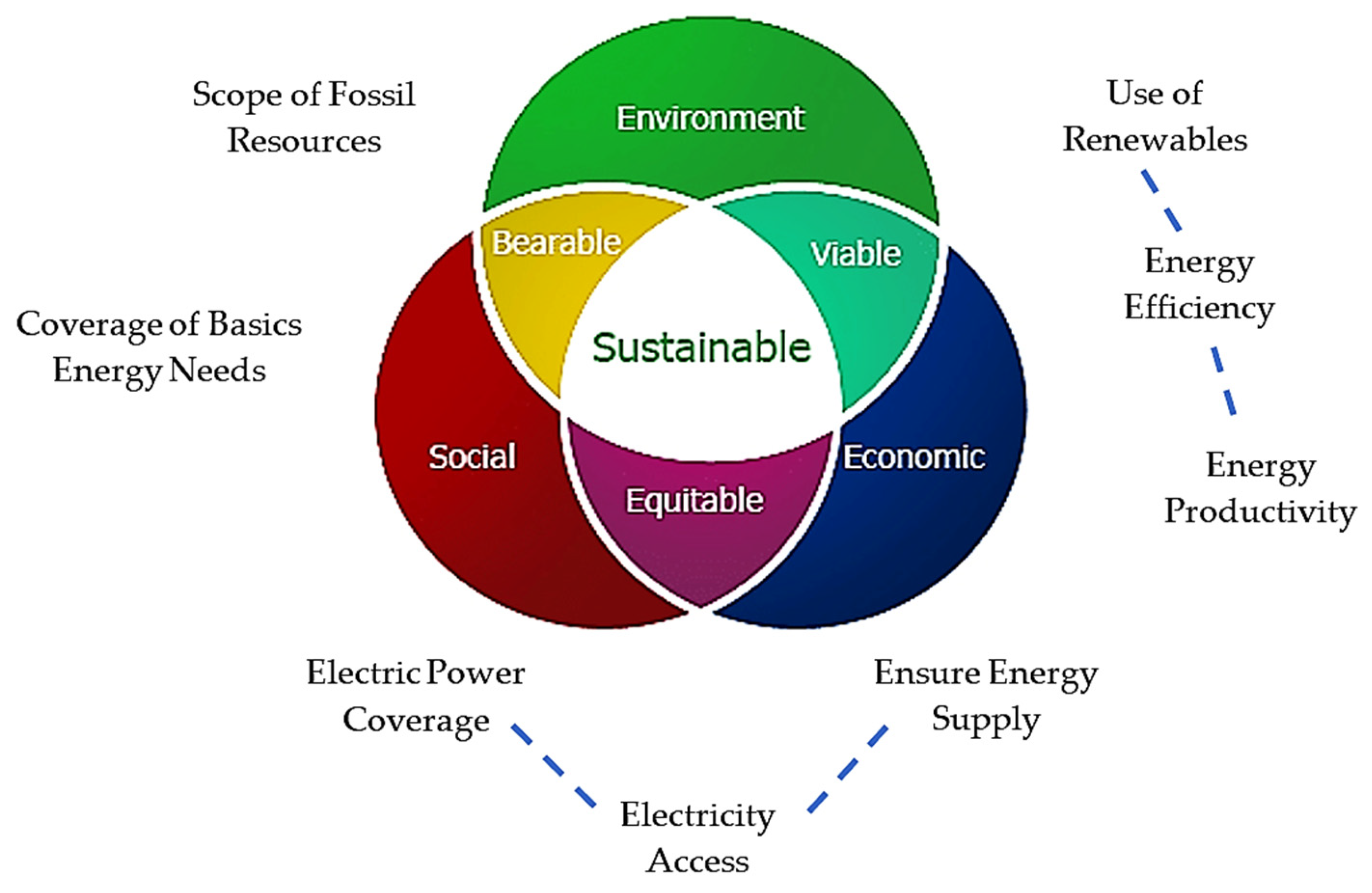

1. Introduction

- ¬

- To develop numerical modeling of conventional PV/T-C systems and Z-fin PV/T-F systems using ANSYS Fluent software.

- ¬

- To analyze the temperature and velocity distributions of relevant components of PV/T-C and Z-fin PV/T-F systems using CFD and evaluate them by presenting visual results.

- ¬

- To develop thermal modeling of conventional PV/T-C systems and Z-fin PV/T-F systems.

- ¬

- To perform energy, exergy, and sustainability analyses of conventional PV/T-C systems and Z-fin PV/T-F systems.

- ¬

- To conduct a comparative analysis of PV/T-C and Z-fin PV/T-F systems in terms of electrical efficiencies, thermal efficiencies, total efficiencies, exergy efficiencies, sustainability indexes, life cycle emissions, CO2 emission prices, levelized costs of energy, and payback periods.

- ¬

- To compare the electrical, thermal, exergy, and sustainability performances of PV/T-C and PV/T-F systems under local climate conditions (Malatya, Türkiye).

2. Materials and Methods

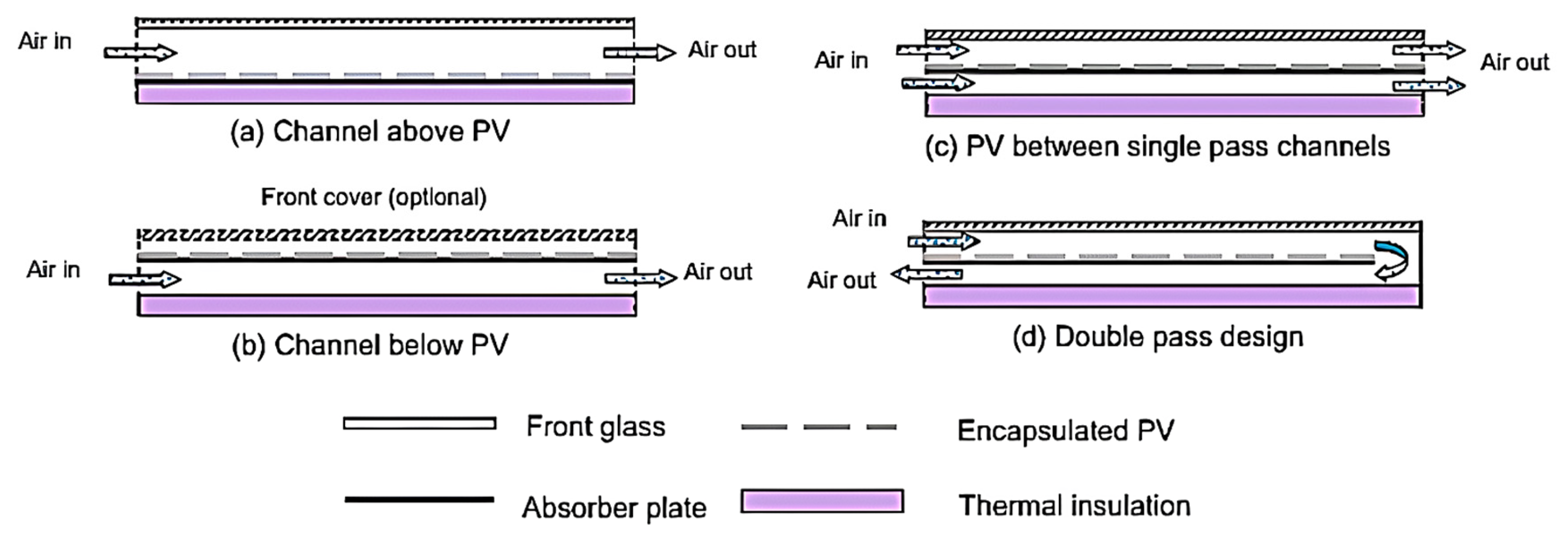

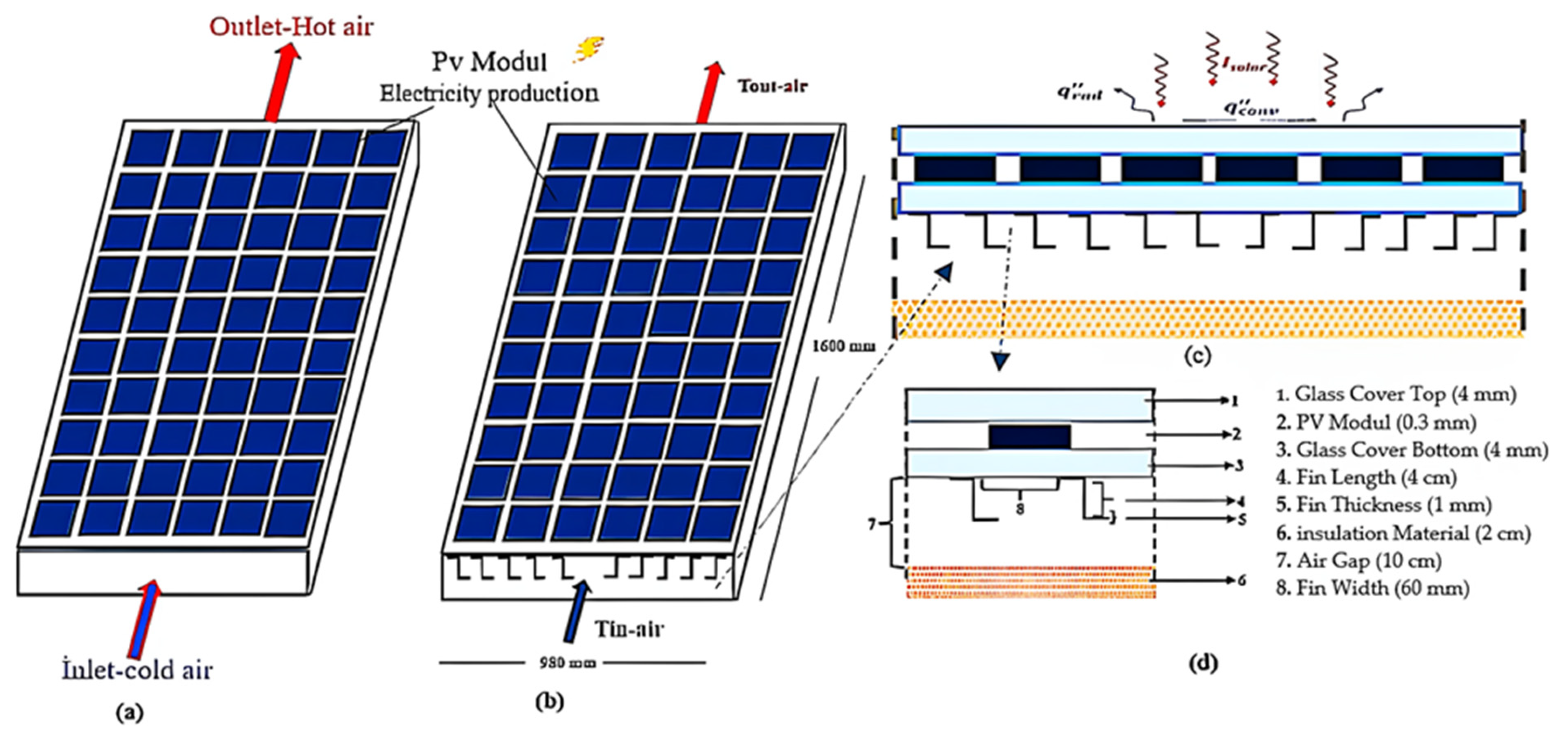

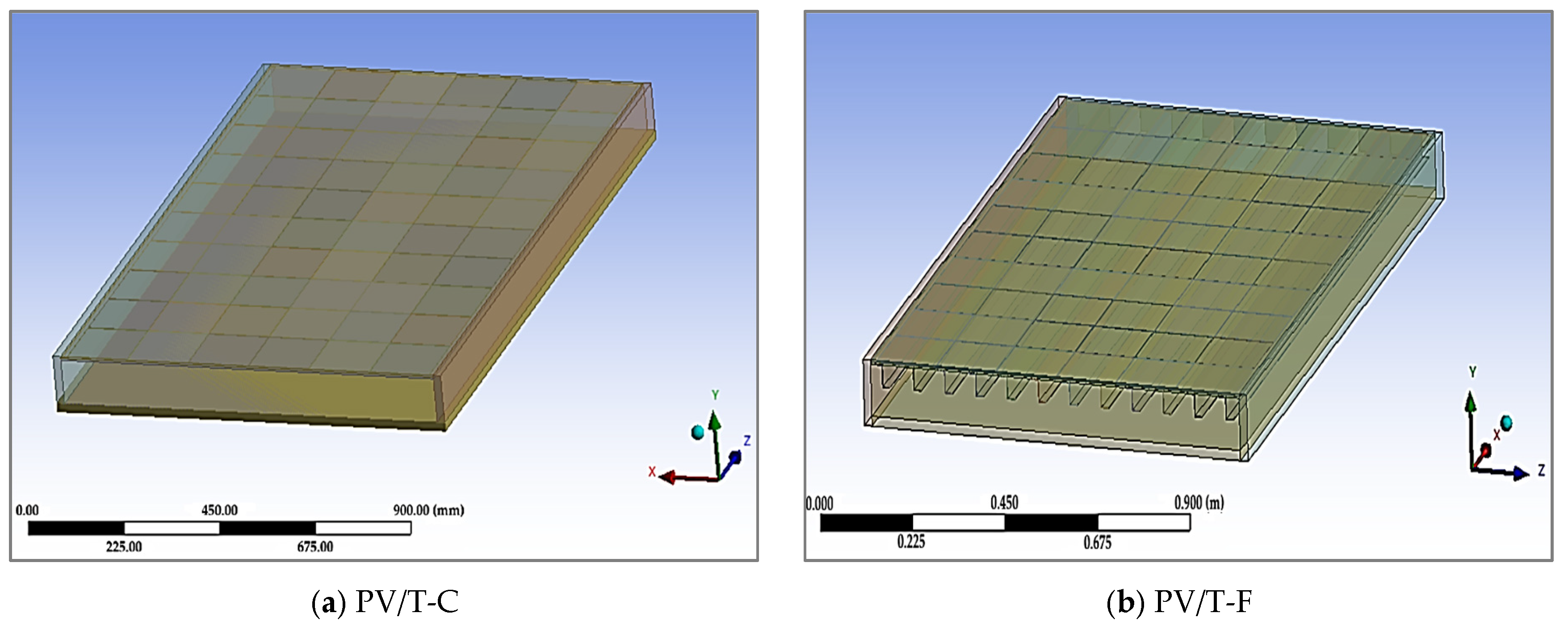

2.1. Description of PV/T System

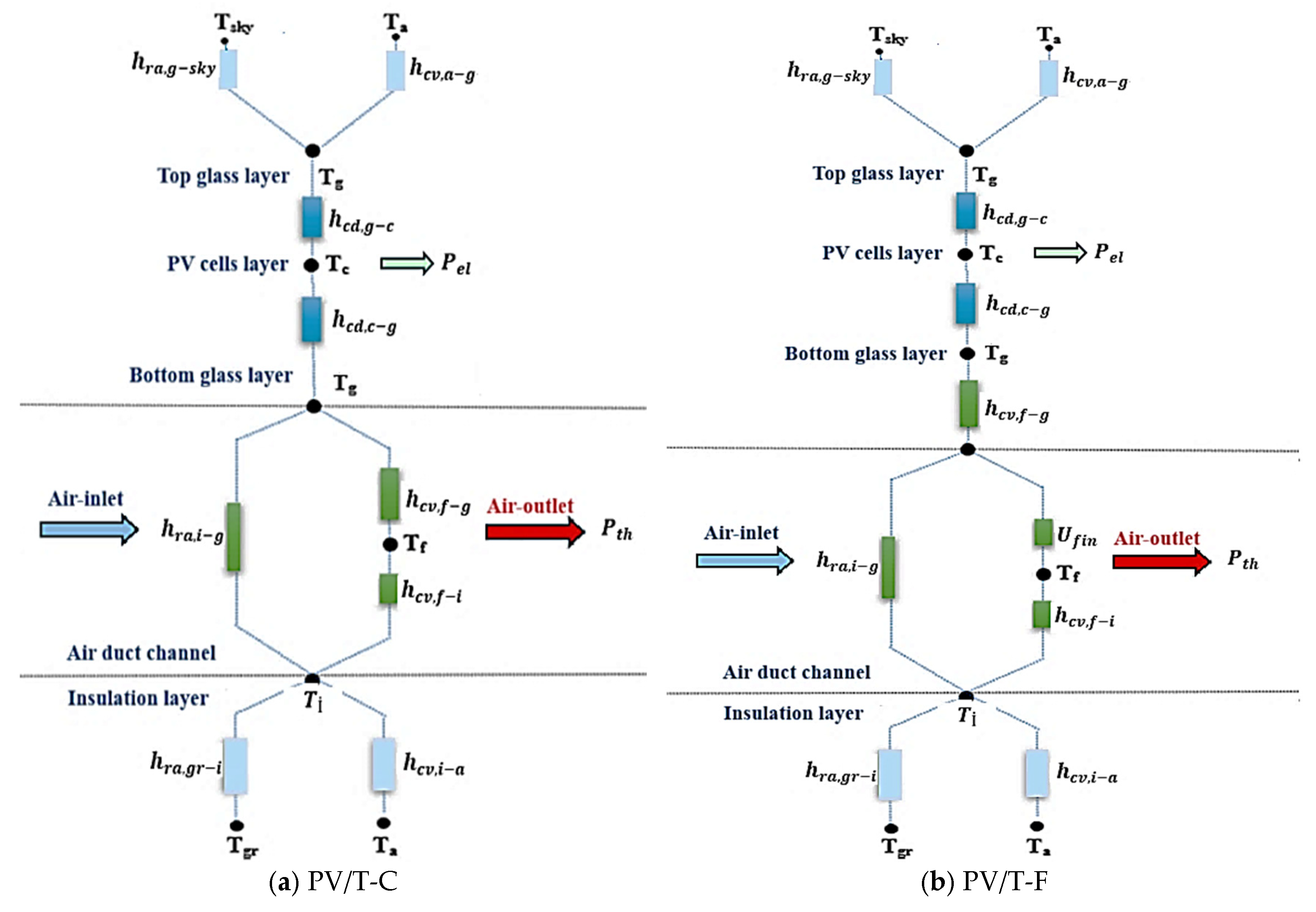

2.2. Mathematical Modeling

2.2.1. Thermal Modeling

- Top glass:

- PV solar cells:

- Bottom glass:

- The air flowing in the duct:

- Thermal insulation:

2.2.2. Numerical Modeling

Creating the Geometric Structure

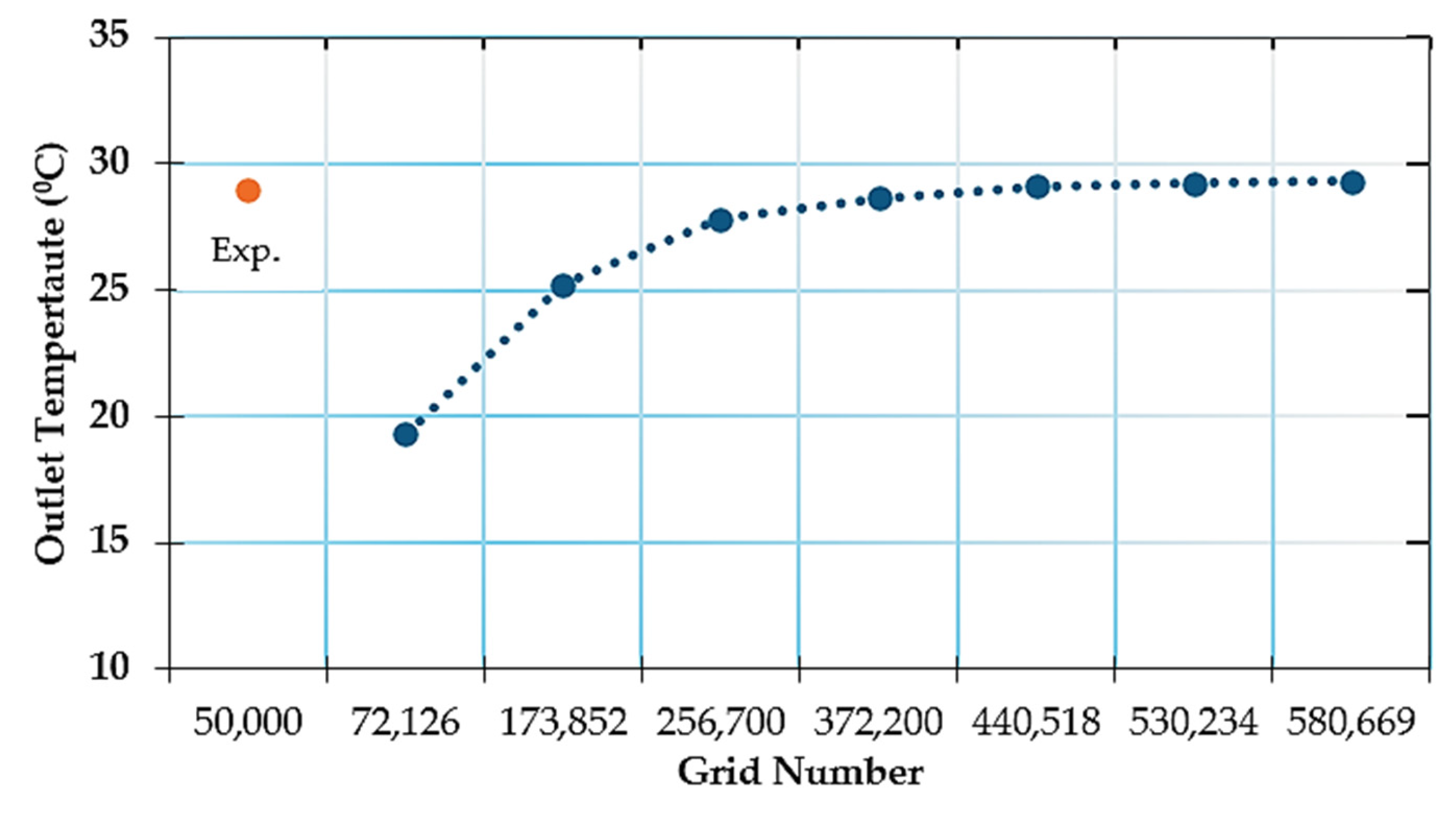

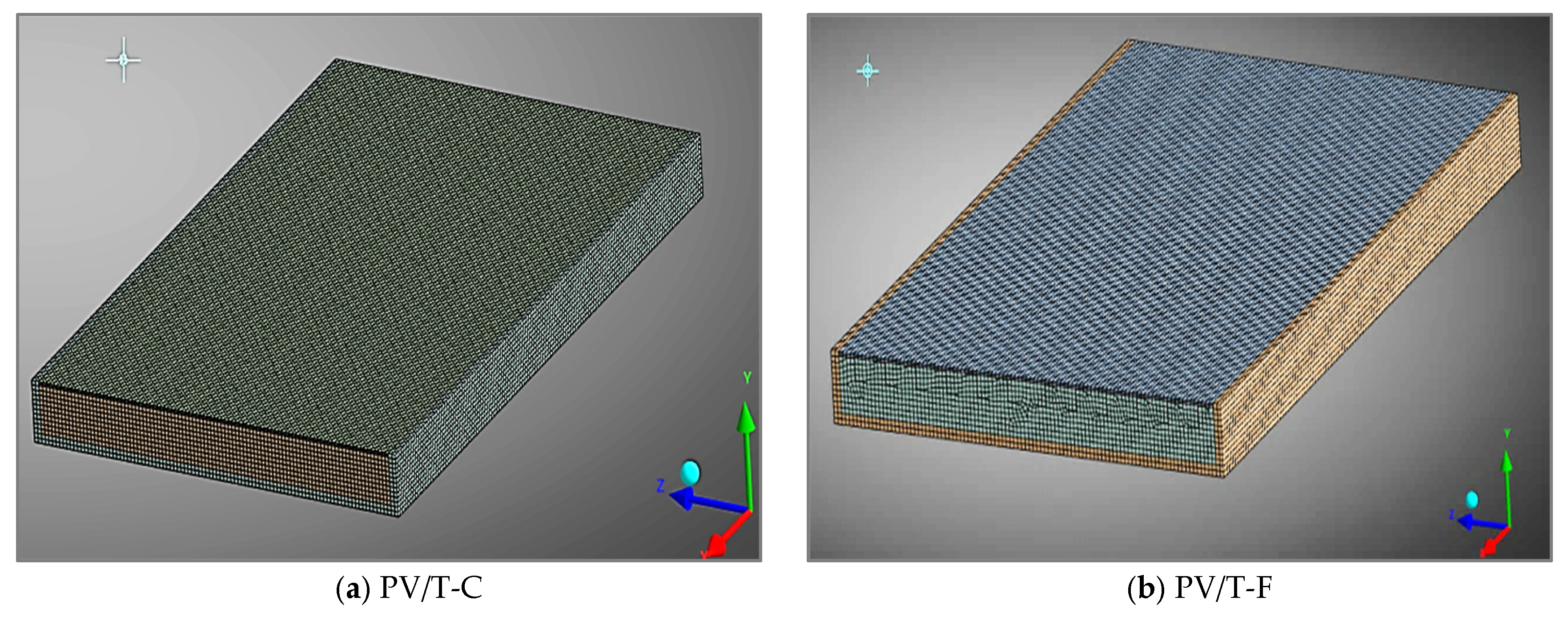

Creating the Mesh Structure

Initial and Boundary Conditions

- ¬

- For the PV/T system, the solar panel received an average heat flux, whereas all other boundaries were considered adiabatic [50].

- ¬

- The inlet air velocity was assumed to be uniform, and a pressure condition was applied at the outlet.

- ¬

- The physical properties of the materials were considered constant [51].

- ¬

- The fin absorber material was assumed to be homogeneous, and a uniform heat transfer coefficient (Ufin) was applied to the entire surface of the fins.

- ¬

- The ambient temperature was to be uniform around the collector [52].

- ¬

- ¬

- No leakage in the channel was assumed.

- ¬

- Air was treated as an ideal gas, and its thermophysical properties were considered uniform along the entire channel [55].

Solving Governing Equations

- Continuity Equation:

- Momentum Equations:

- Energy Equation:

2.3. Electrical Efficiency

2.4. Thermal Efficiency

2.5. Overall Energy Efficiency

2.6. Exergy Analysis and Sustainability Index

2.7. Techno-Economic and Environmental Analysis

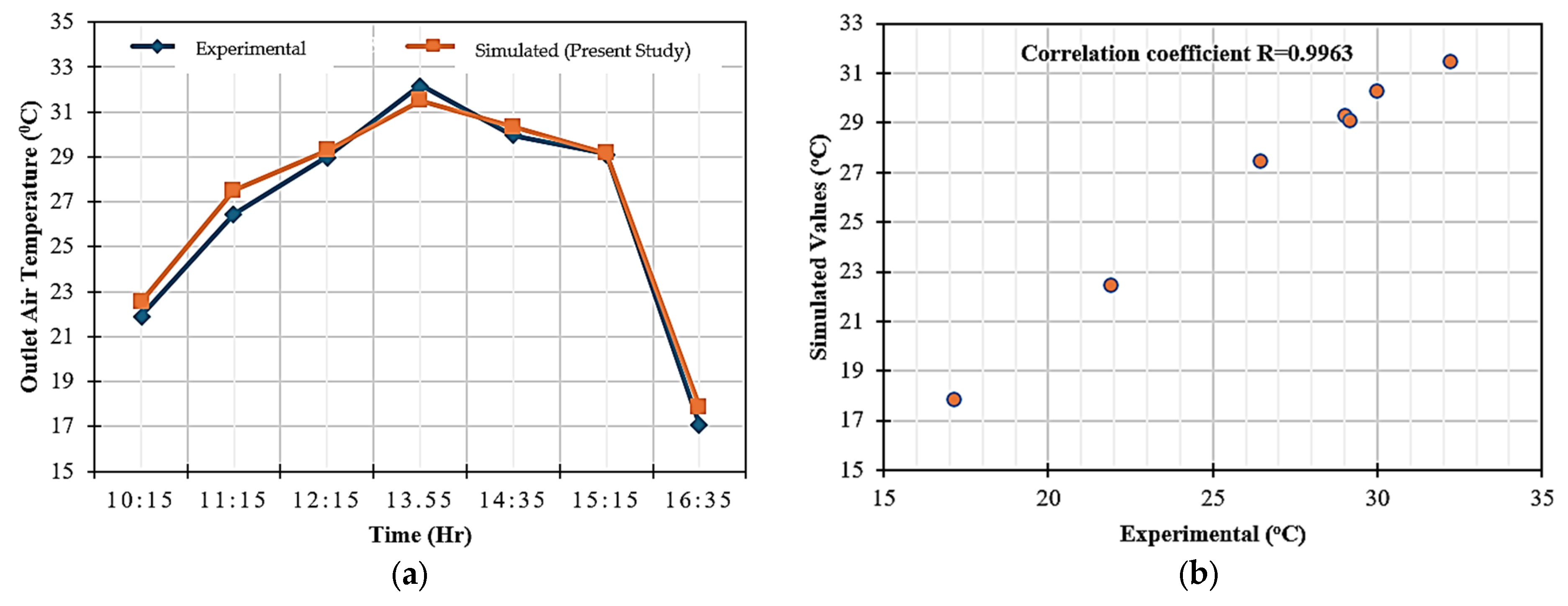

2.8. Statistical Validation of the Numerical Model

3. Results and Discussion

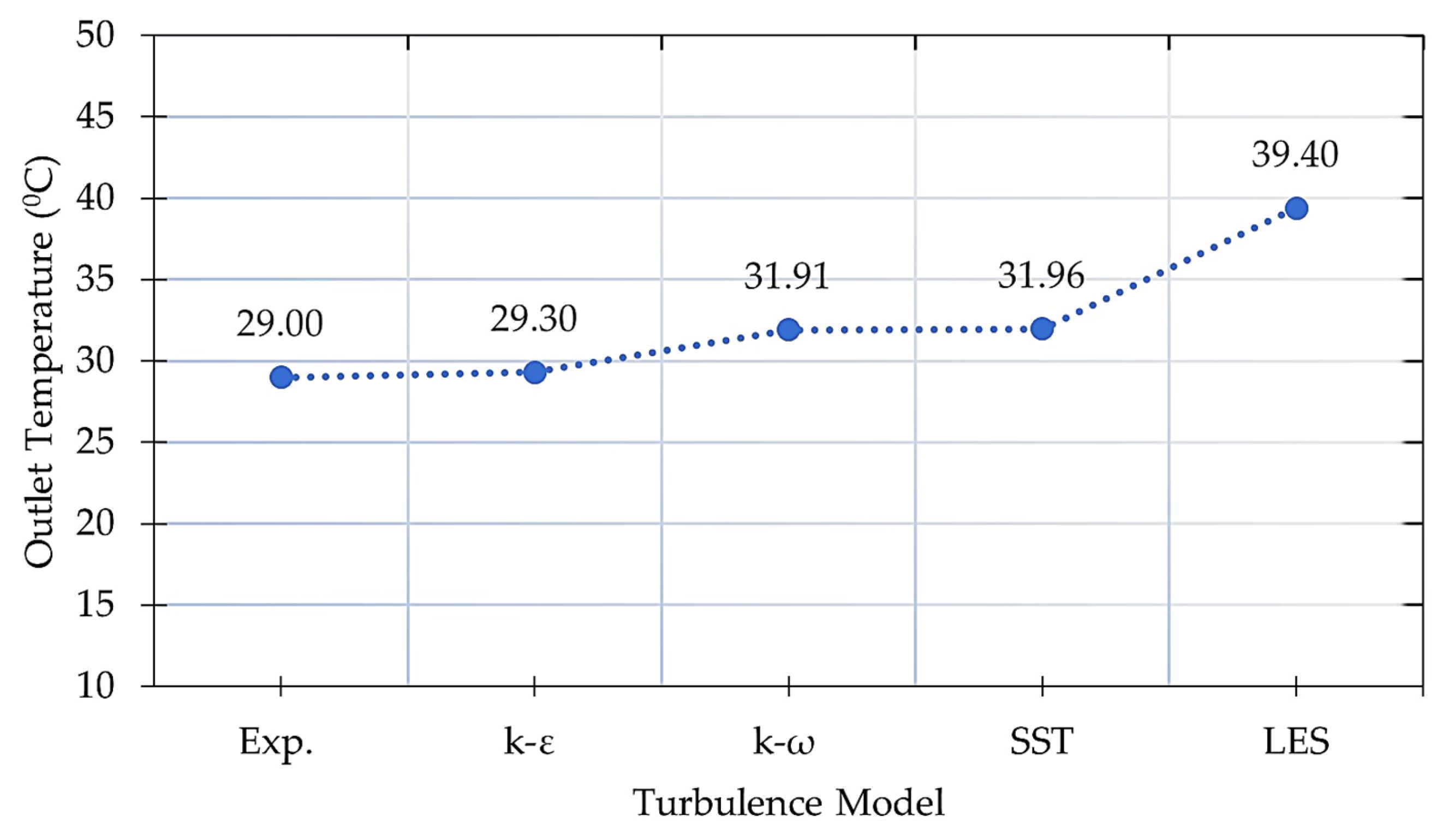

3.1. Validation of Numerical Result

3.2. Comparison of PV/T-C and PVT-F Systems

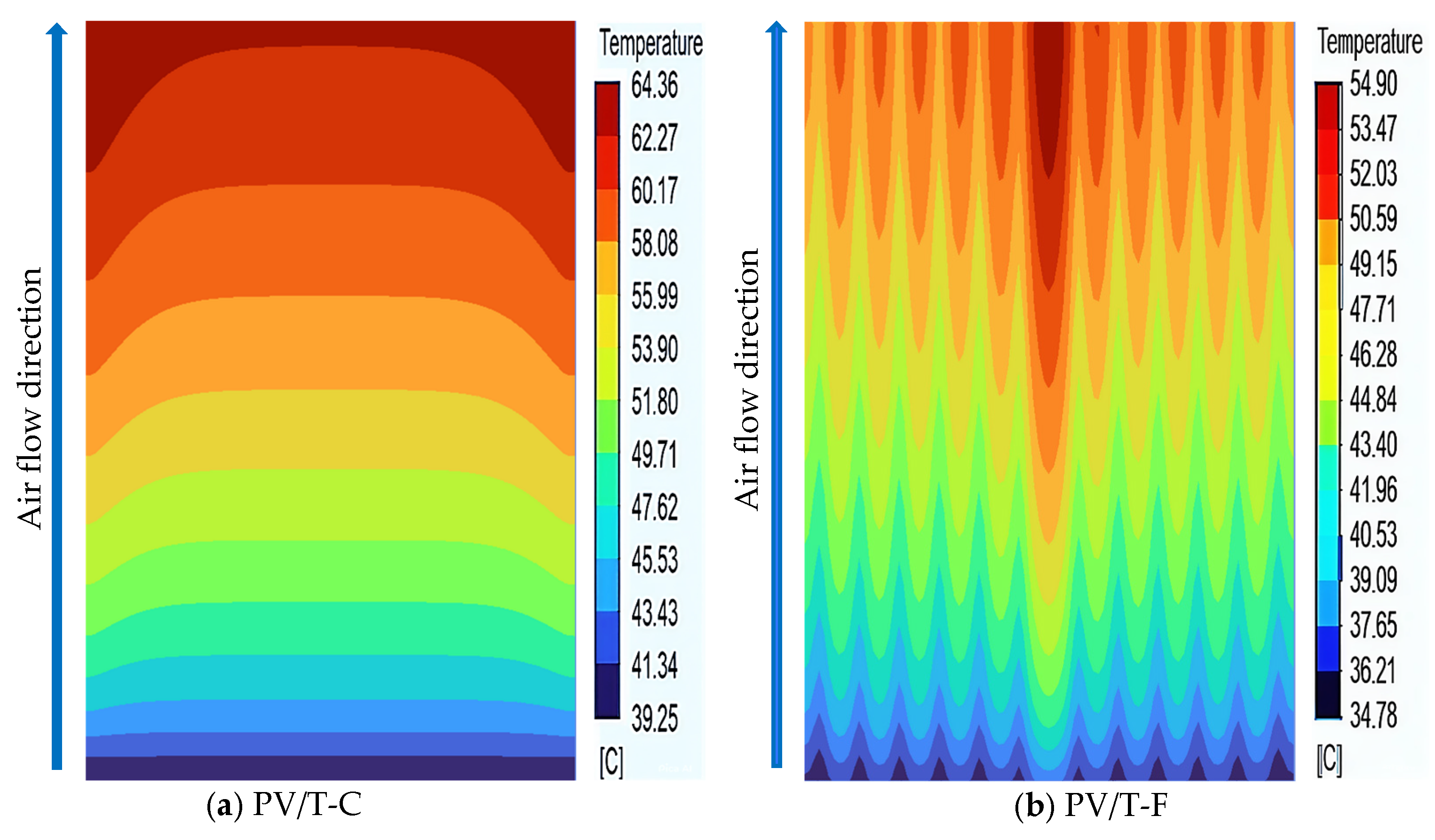

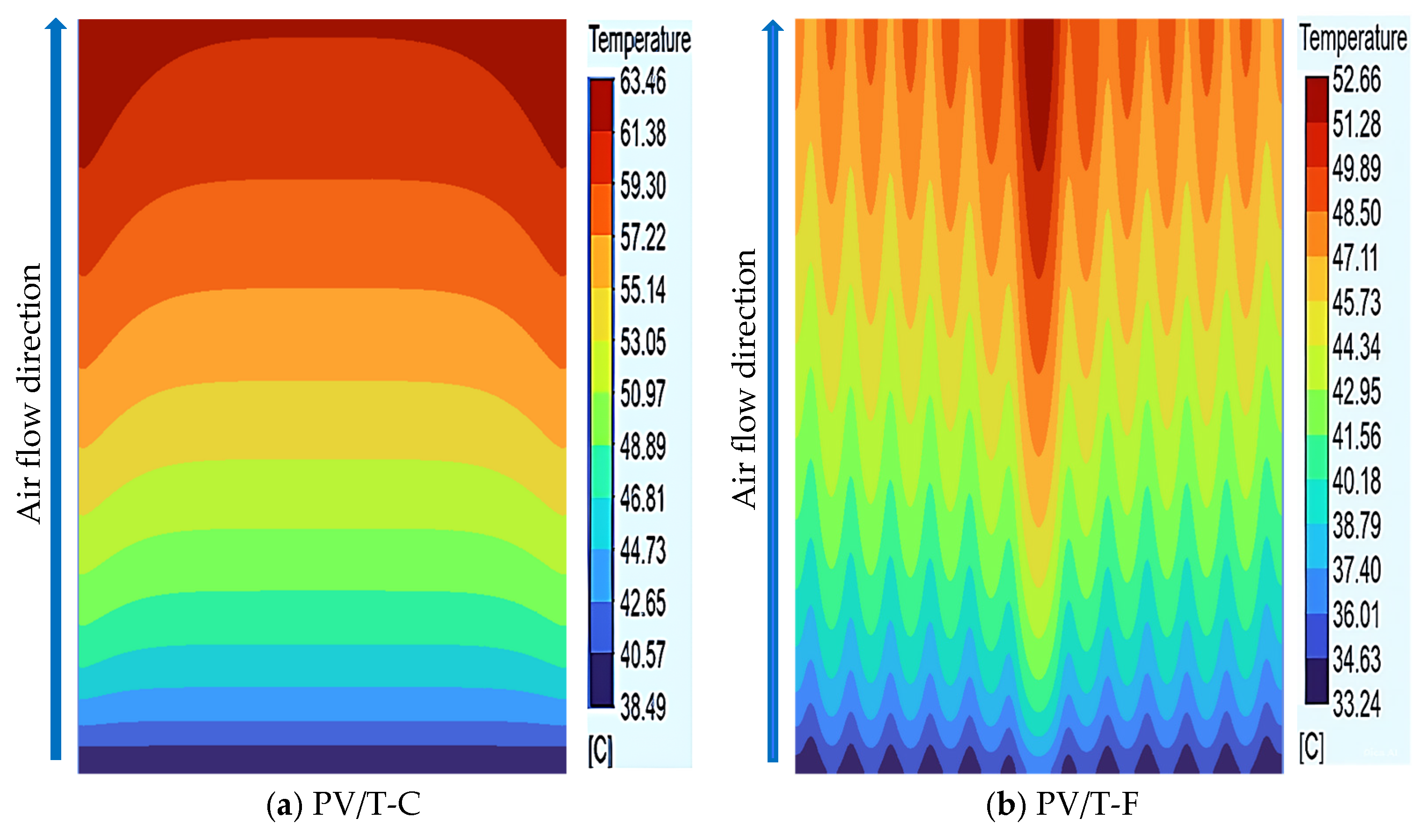

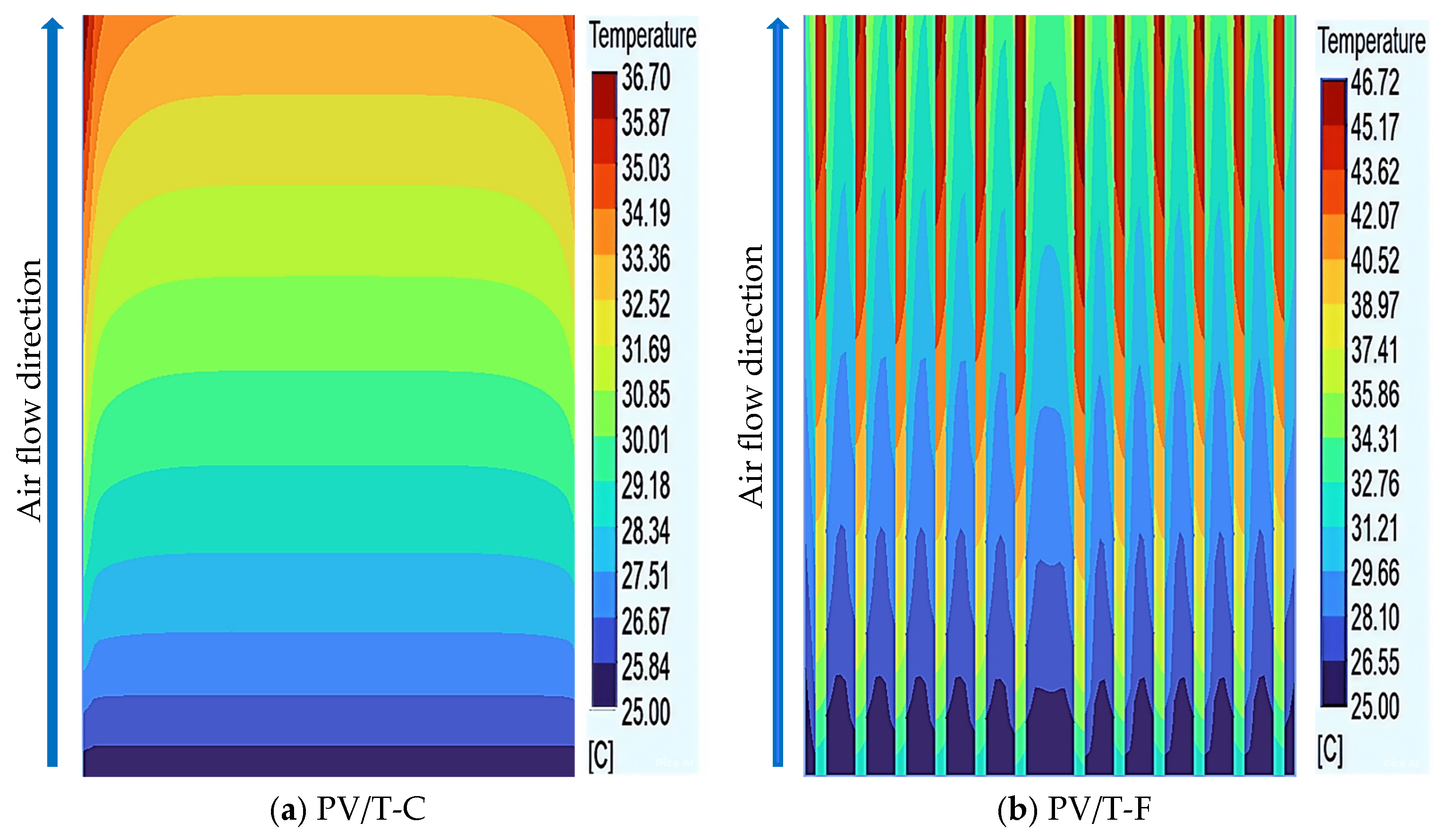

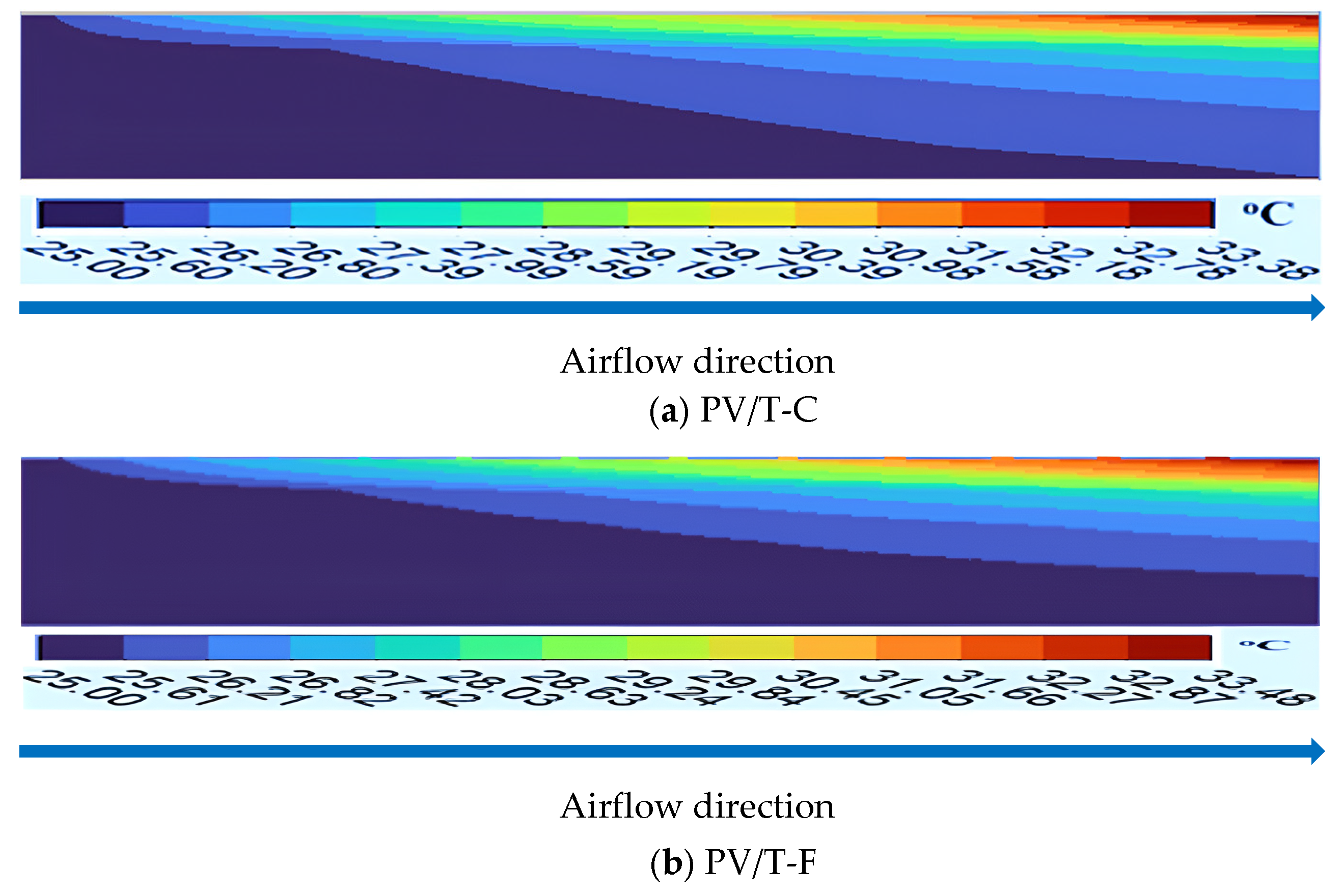

3.2.1. Temperature Distributions

Top Glass Temperature

The Average PV Cell Temperature

Channel Top Surface Temperature

Channel Mid-Section Temperature

Outlet Air Temperature Distribution

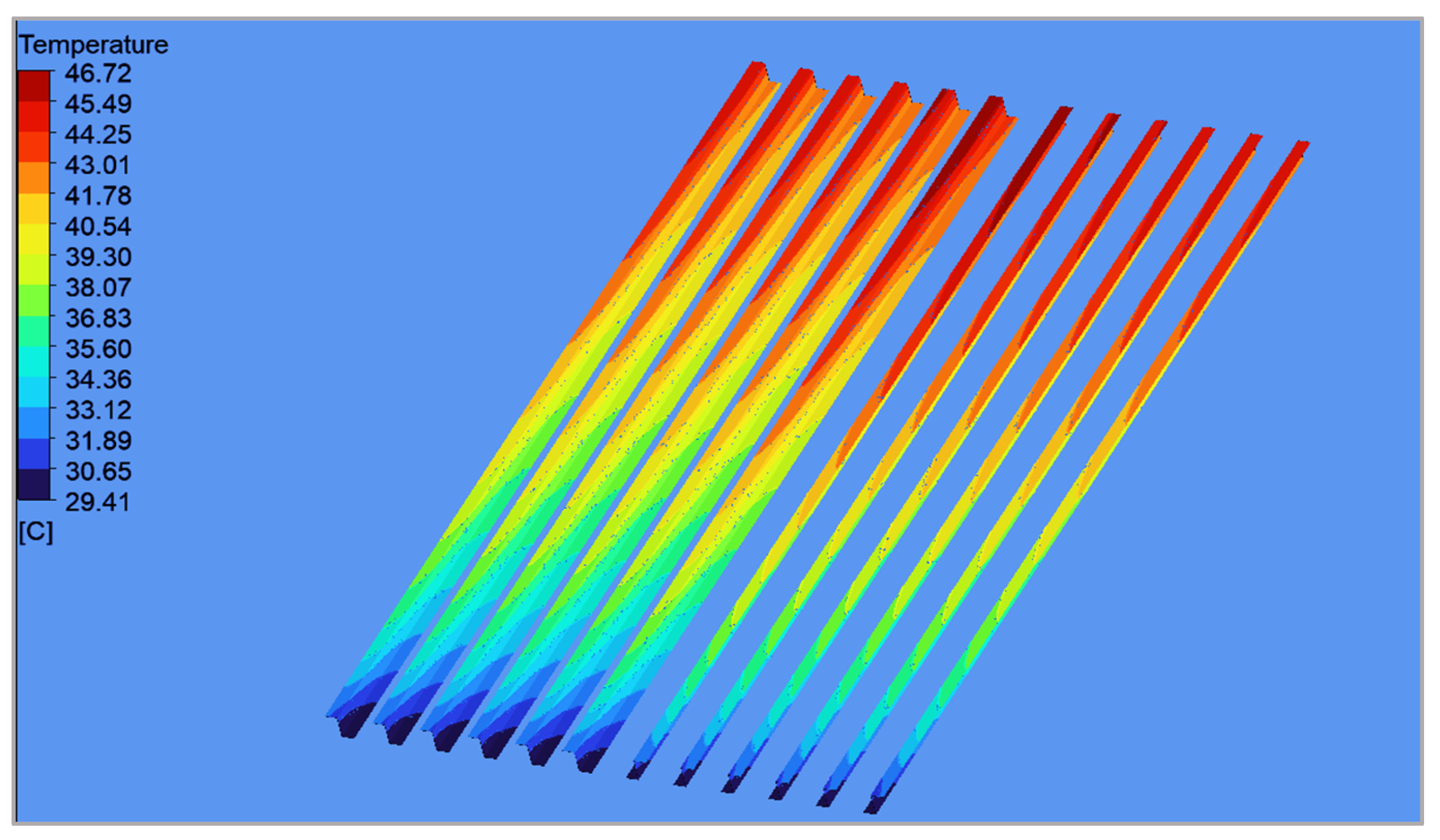

Fin Temperature Distribution

3.2.2. Velocity Distributions

The Velocity Distributions of the Longitudinal Mid-Section of the Channel

Outlet Air Velocity Distribution

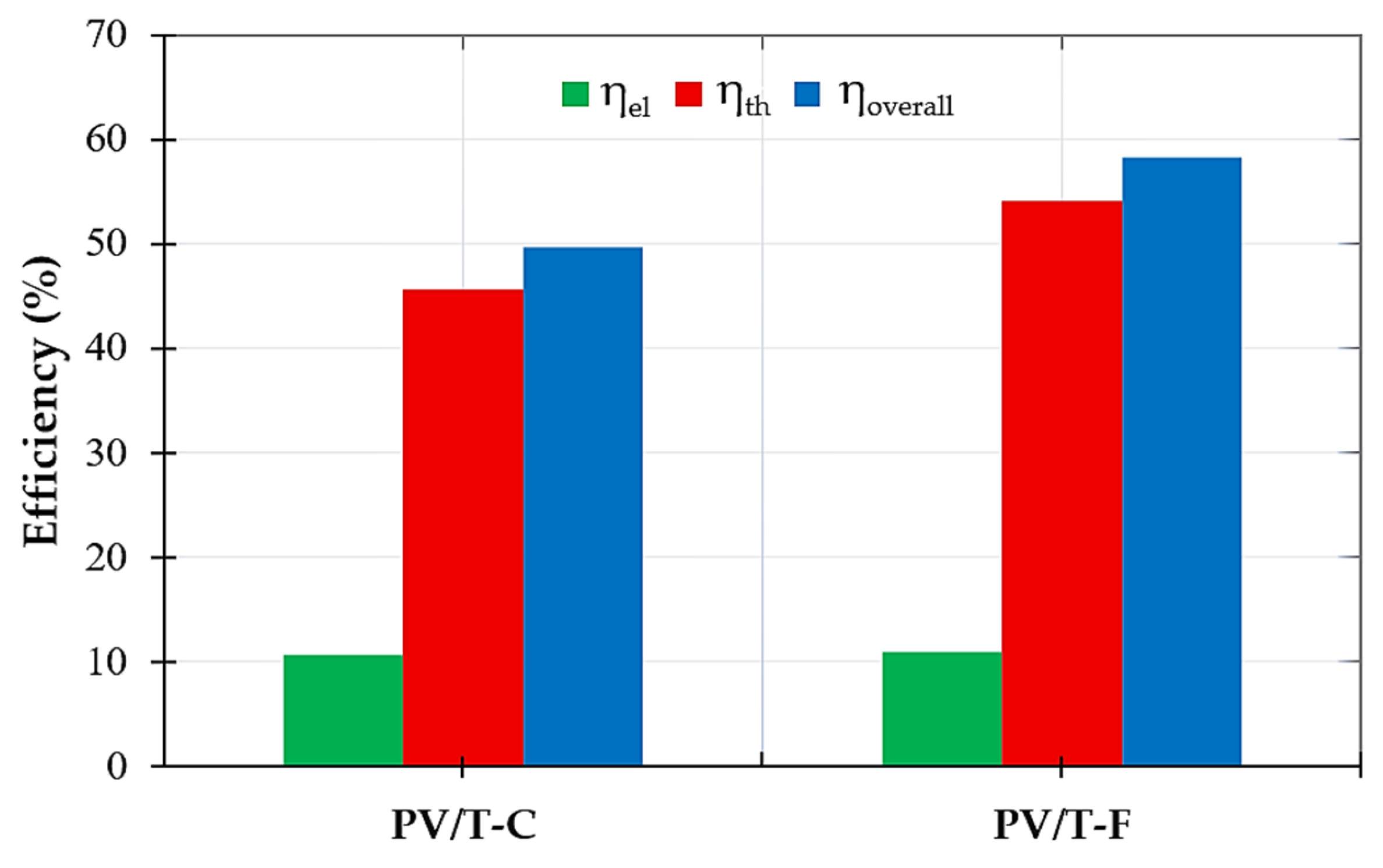

3.2.3. Electrical Efficiency, Thermal Efficiency, and Overall Efficiency

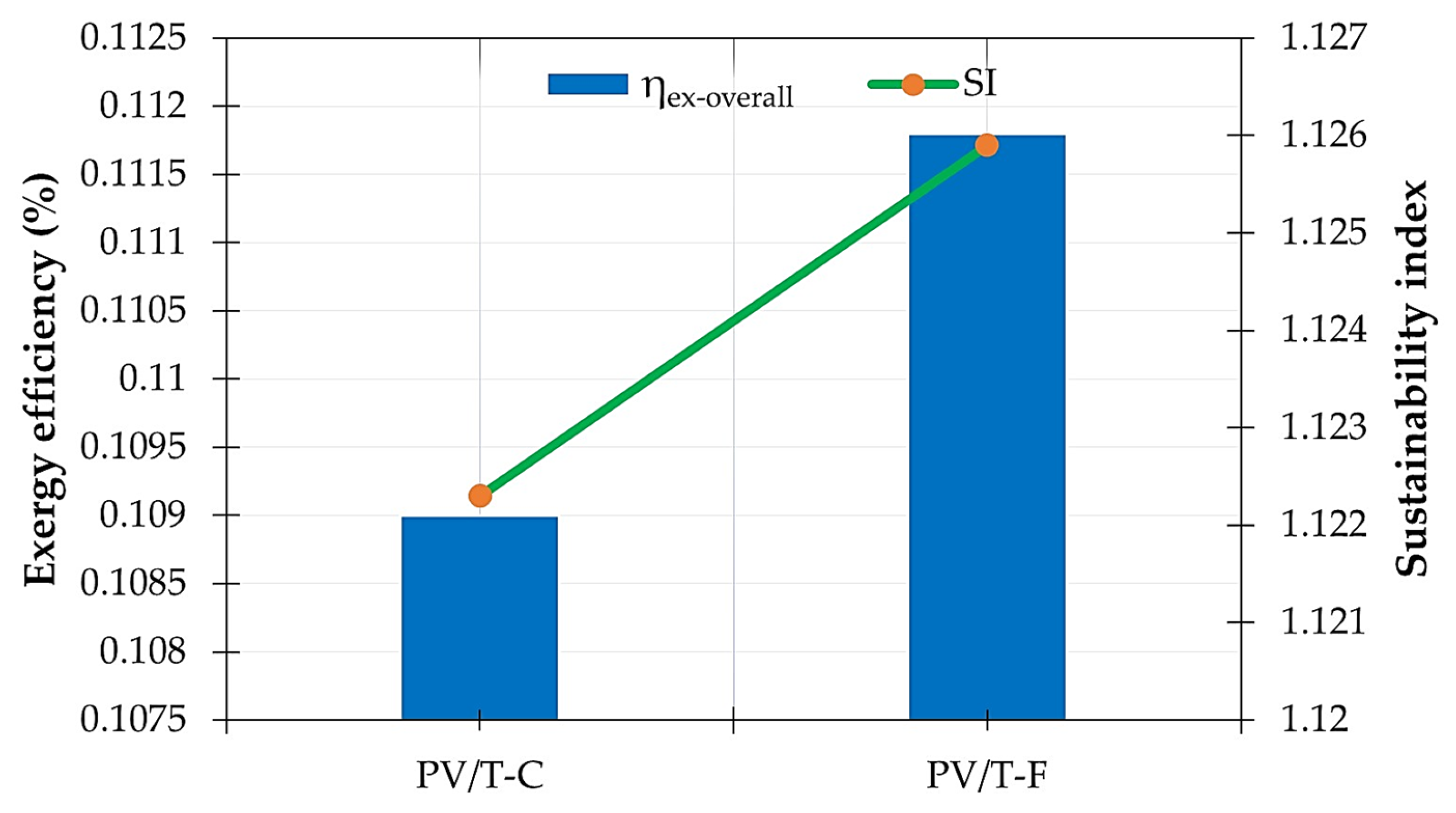

3.2.4. Exergy Efficiency and Sustainability Index

3.3. Use of PV/T-C and PV/T-F Systems in Malatya Province Climatic Conditions

3.3.1. Climatic Conditions of Malatya Province

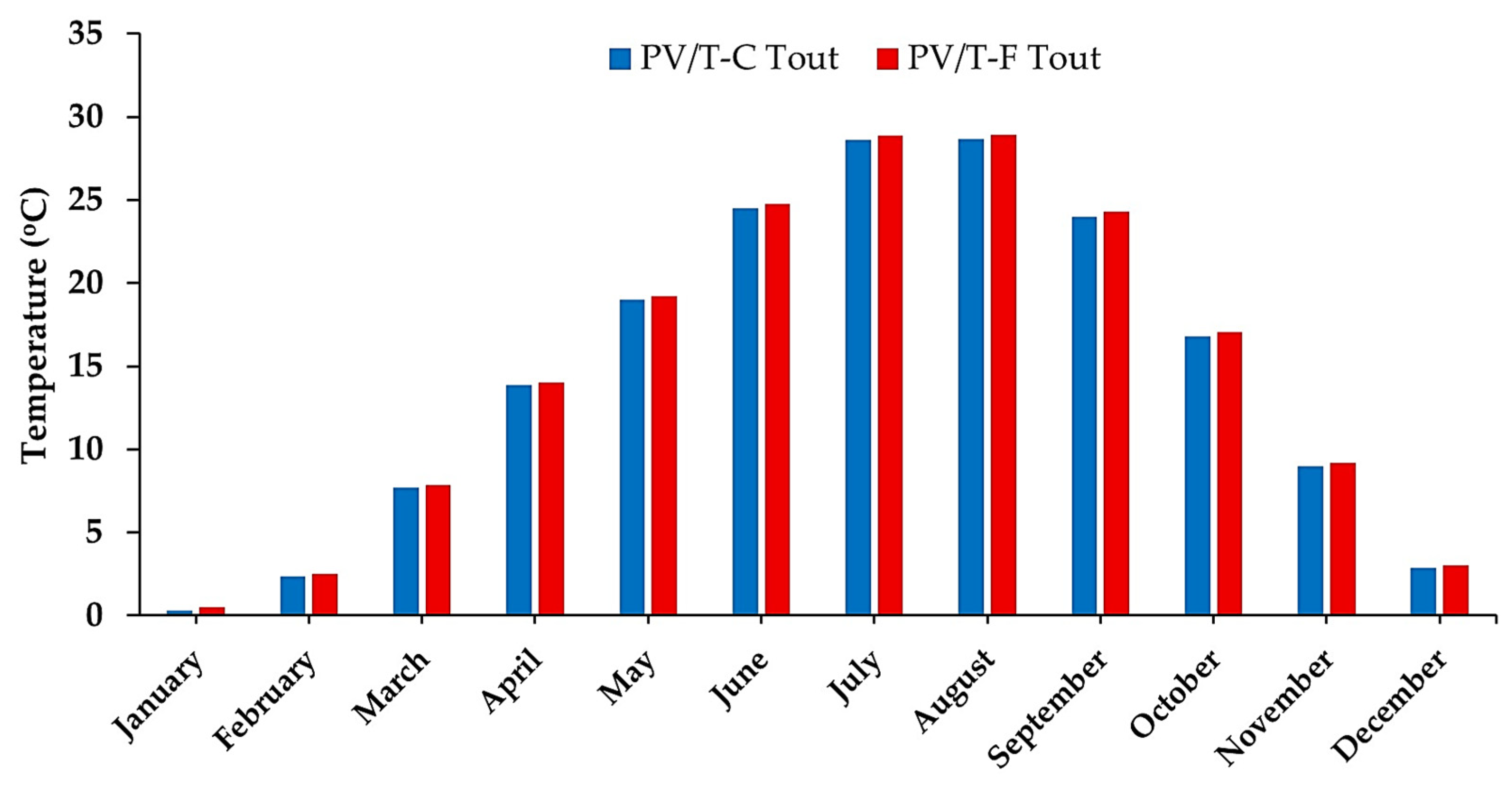

3.3.2. The Outlet Air Temperature

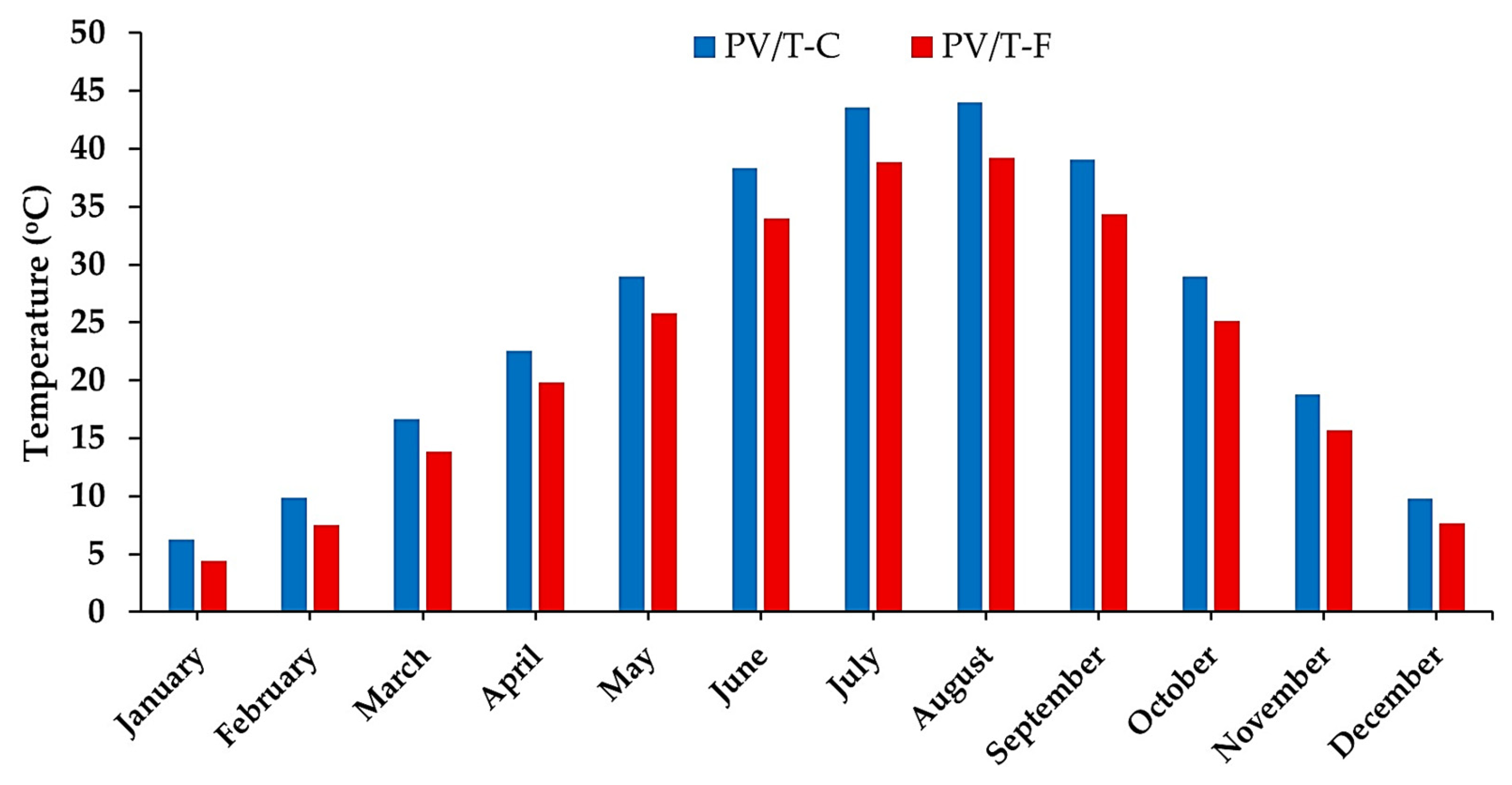

3.3.3. The Average PV Cell Temperature

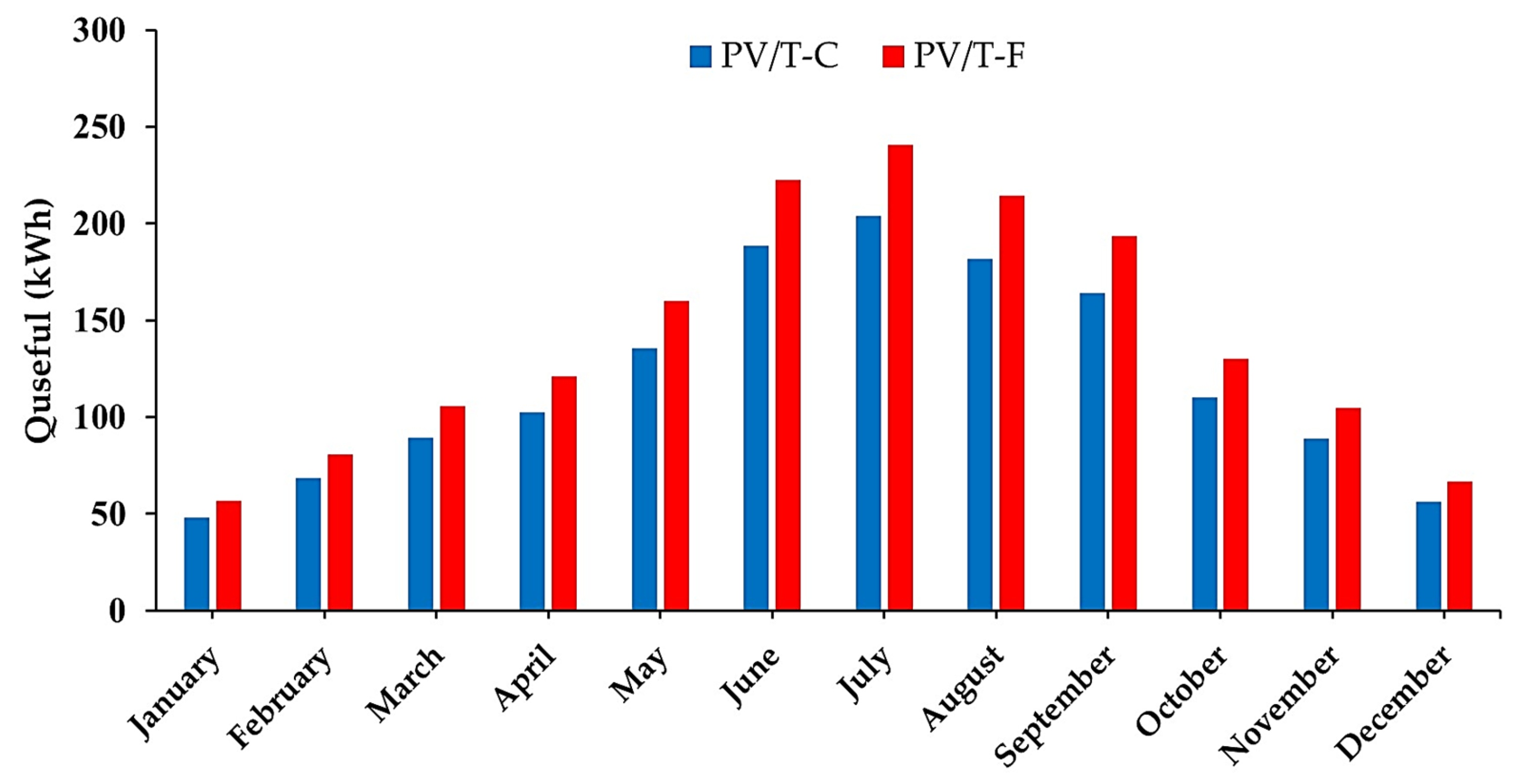

3.3.4. The Useful Heat of the Outlet Air

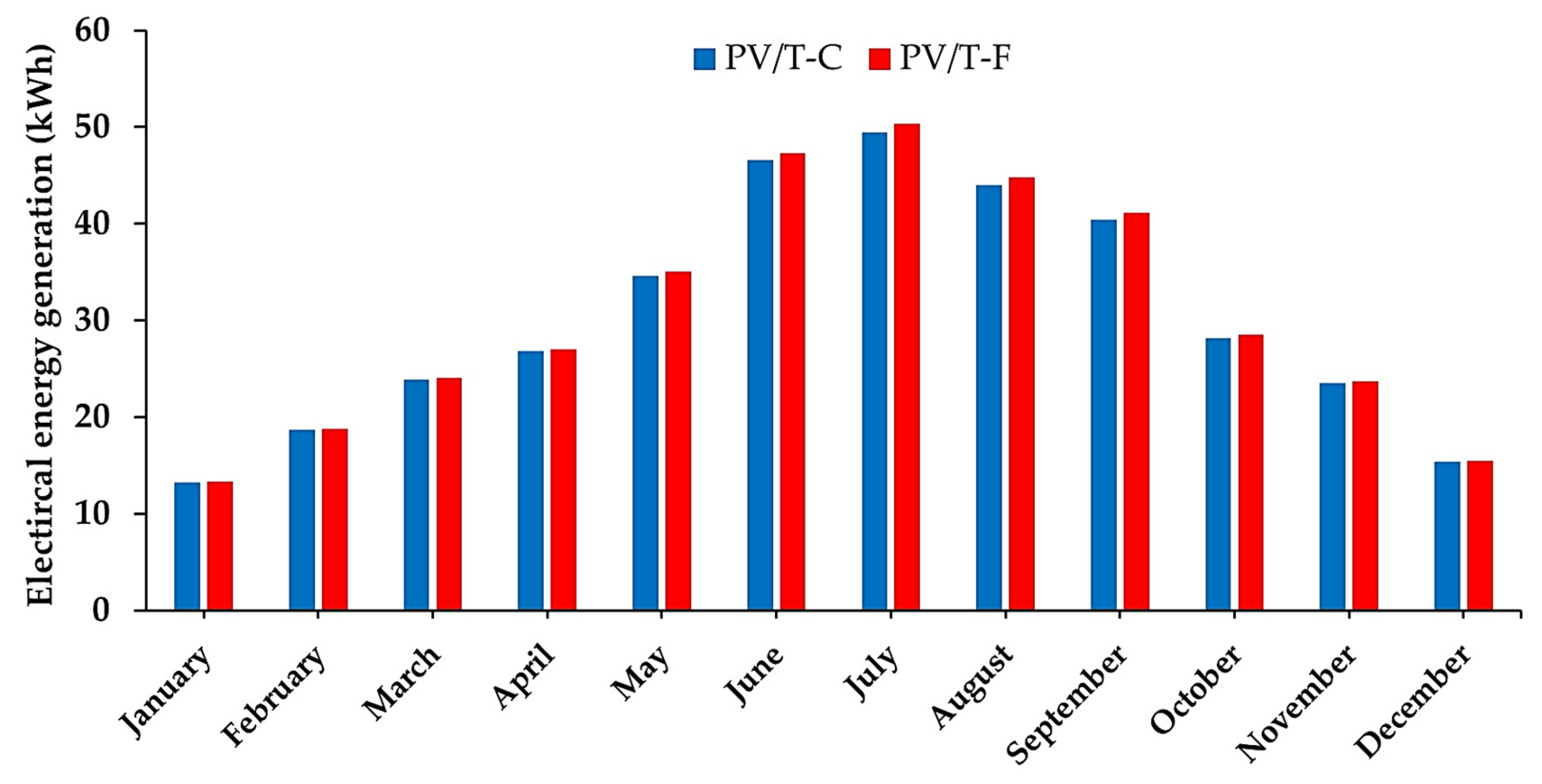

3.3.5. The Monthly Electrical Energy Generation

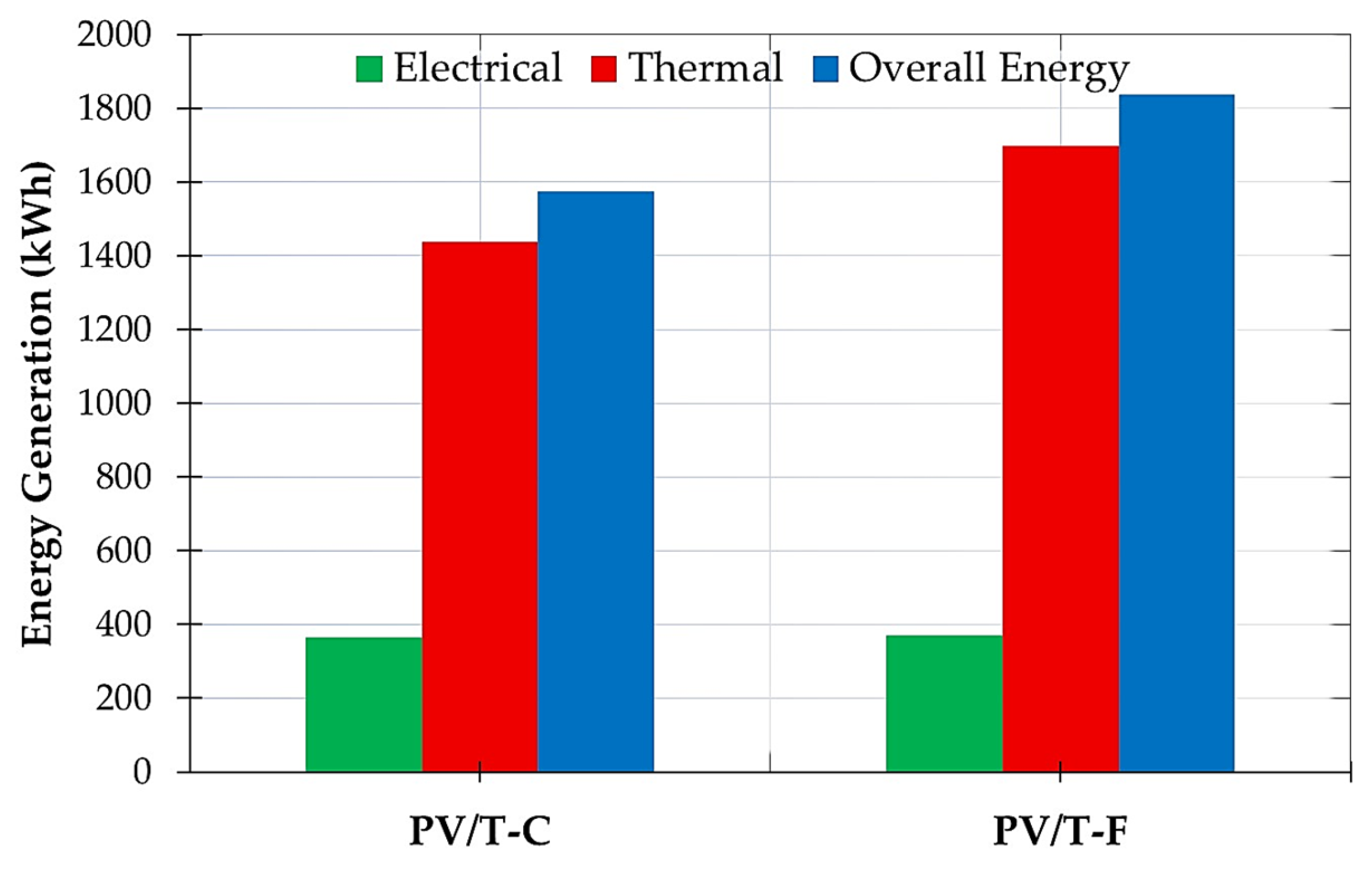

3.3.6. The Annual Electrical, Thermal, and Overall Energy Generation

3.3.7. The Annual Electrical, Thermal, and Overall Efficiency

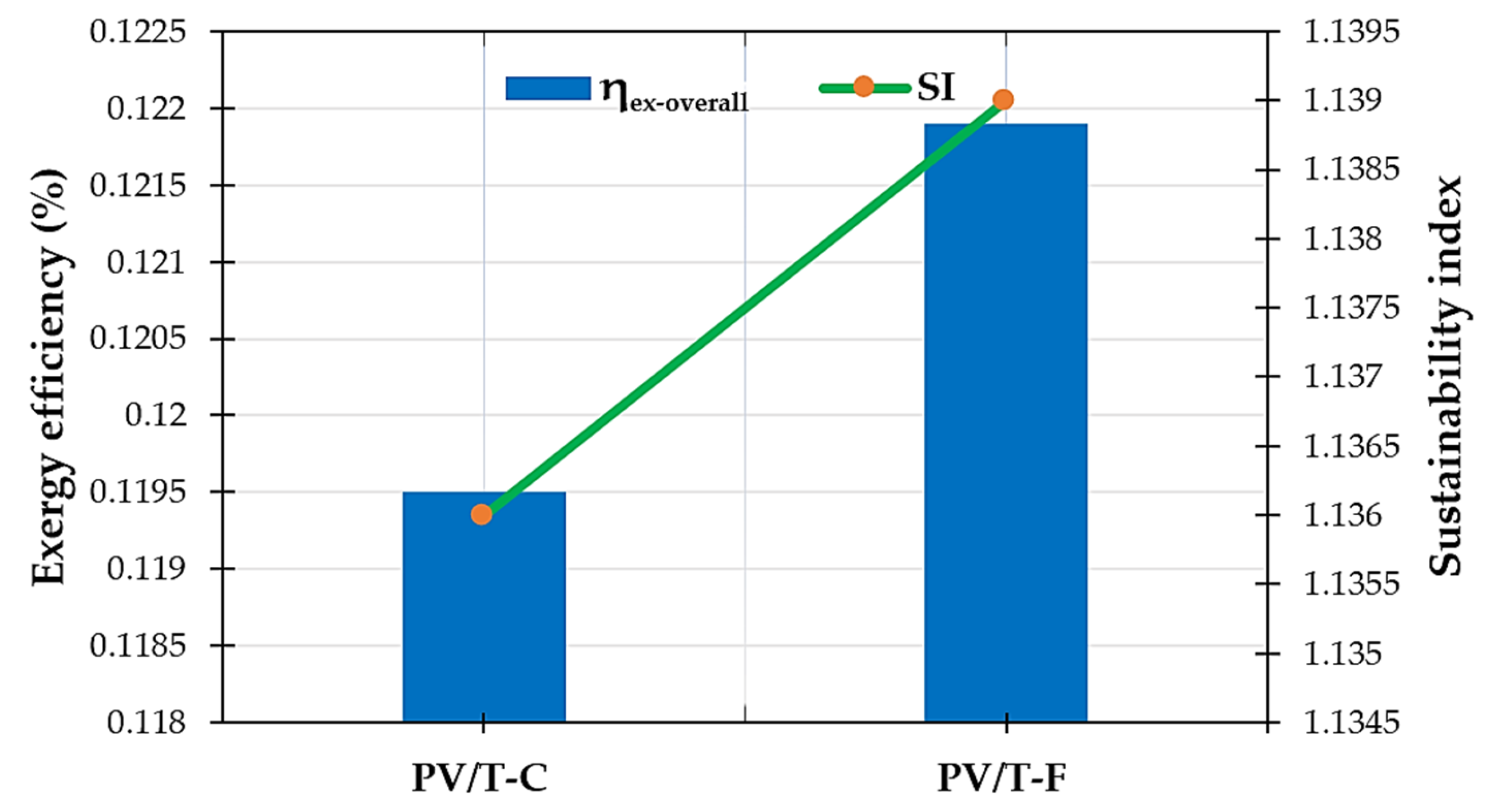

3.3.8. The Exergy Efficiency and Sustainability Index

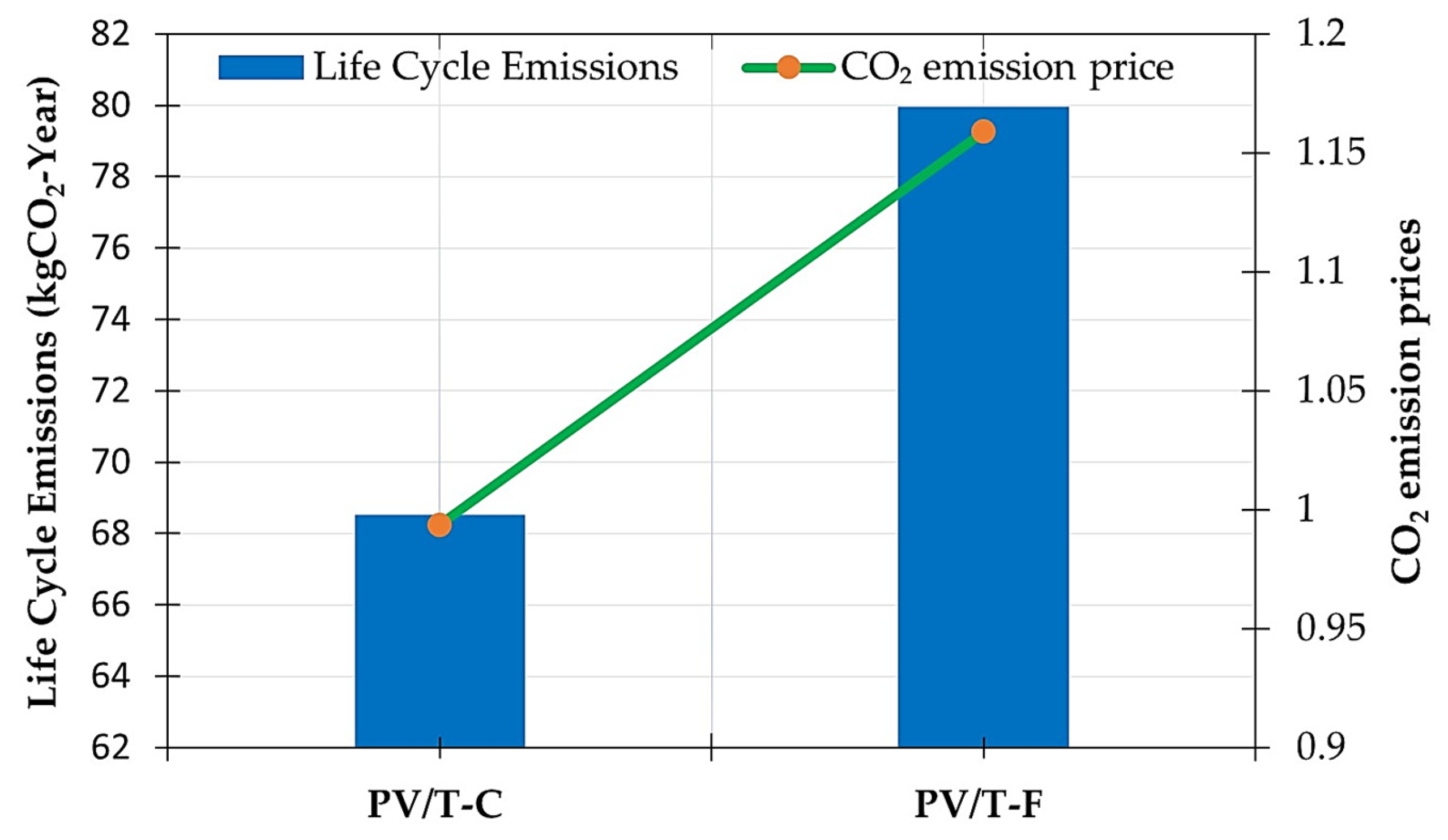

3.3.9. Techno-Economic and Environmental Analysis

3.4. Comparison of PV/T-C and PV/T-F Systems

3.5. Comparisons with the Literature Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Area (m2) |

| Br | Temperature coefficient of the PV cell (K−1) |

| C | Specific heat (J.Kg−1 K−1) |

| Enviroeconomic factor (USD/year) | |

| D | Diameter |

| Exergy | |

| Electricity tariffs (USD/kWh) | |

| Heat tariffs (USD/kWh) | |

| Emission price of CO2 (USD/kgco2) | |

| F | Packing factor |

| G | Solar radiation (W·m−2) |

| h | Coefficient of heat transfer (W/m2·K) |

| k | Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) |

| LCE | life cycle emissions (kgCO2) |

| LCOE | Levelized cost of energy (USD/kWh) |

| M | Mass (kg) |

| Flow rate of mass (kg/s) | |

| Nu | Nusslet number |

| Pr | Prandtl number |

| PV | Photovoltaic panel |

| PV/T | Photovoltaic thermal |

| PV/T-C | Conventional photovoltaic thermal |

| PV/T-F | Finned photovoltaic thermal |

| Qu | Useful energy gain (W) |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| SI | Sustainability index |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| V | Velocity (m/s) |

| Greek symbols | |

| α | Absorptivity |

| η | Energy Efficiency |

| ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| σ | Stefan–Boltzmann constant (W/m2·K4) |

| ε | Emissivity |

| µ | Dynamic viscosity (kg/m·s) |

| δ | Thickness (m) |

| τ | Transmissivity of glass cover |

| Subscripts | |

| a | ambient |

| c | solar cell |

| cd | conduction |

| cv | convection |

| el | electrical |

| f | transfer fluid |

| out | outlet |

| g | glass cover |

| gr | ground |

| ra | radiative |

| t | time |

| th | thermal |

References

- Muniz, R.N.; da Costa Júnior, C.T.; Buratto, W.G.; Nied, A.; González, G.V. The Sustainability Concept: A Review Focusing on Energy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Brettel, M.; Mauer, R. The three dimensions of sustainability: A delicate balancing act for entrepreneurs made more complex by stakeholder expectations. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippidis, G.; Sartori, M.; Ferrari, E.; Marek, R. Waste not, want not: A bio-economic impact assessment of household food waste reductions in the EU. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casem, What Is Sustainability? Available online: https://www.casem.com.tr/surdurulebilirlik-nedir/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Winss. What Sustainability Indicators Exist Now and Should Be Used? Available online: https://www.winssolutions.org/what-sustainability-indicators-exist-now-and-should-be-used/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Rosen, M.A. Energy Sustainability: A Pragmatic Approach and Illustrations. Sustainability 2009, 1, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Goal 7: Ensure Access to Affordable, Reliable, Sustainable and Modern Energy for All; United Nations Sustainable Development: New York, NY, USA; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/energy/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Sova Solar. Solar Energy: A Beacon for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sova Solar Blog, 3 September 2024. Available online: https://sovasolar.com/solar-energy-a-beacon-for-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Smets, A.; Jäger, K.; Swaaıj, O.I.R.V.; Zeman, M. Solar Energy: The Physics and Engineering of Photovoltaic Conversion, Technologies and Systems, 1st ed.; UIT Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 27–33. Available online: https://books.google.com.tr/books?hl=tr&lr=&id=gj7JEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Energy:+The+Physics+and+Engineering+of+Photovoltaic+Conversion,+Technologies+and+Systems&ots=Mt-8DOTBUd&sig=ElDxu43yxqBcOsiHx_mcnz-kggs&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Energy%3A%20The%20Physics%20and%20Engineering%20of%20Photovoltaic%20Conversion%2C%20Technologies%20and%20Systems&f=false (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Sharma, A. A comprehensive study of solar power in India and World. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, M.E.; Diner, F. A review of the factors affecting operation and efficiency of photovoltaic based electricity generation systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, M.; Mohsin, A.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain Bhuian, M.B. A comprehensive evaluation of solar cell technologies associated loss mechanisms, and efficiency enhancement strategies for photovoltaic cells. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3345–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauter, S. Increased electrical yield via water flow over the front of photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2004, 82, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.T.; Rashel, M.R.; Abdullah-Al-Wadud, M.; Hoque, T.T.; Janeiro, F.M.; Tlemcani, M. Mathematical Modeling, Parameters Effect, and Sensitivity Analysis of a Hybrid PVT System. Energies 2024, 17, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hadi Attia, M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.M.; Khelifa, A. A numerical approach to enhance the performance of double-pass solar collectors with finned photovoltaic/thermal integration. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 268, 125974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, H.; Rossi di Schio, E.; Semprini, G.; Valdiserri, P. Photovoltaic-thermal solar-assisted heat pump systems for building applications: A technical review on direct expansion systems. Energy Build. 2025, 334, 115516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, C.; Ponnambalam, P. The role of thermoelectric generators in the hybrid PV/T systems: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 151, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.T. A review on photovoltaic/thermal hybrid solar technology. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Tiwari, G.N. Performance analysis in terms of carbon credit earned on annualized uniform cost of glazed hybrid photovoltaic thermal air collector. Sol. Energy 2015, 115, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Agarwal, S.; Tiwari, G.N.; Chauhan, D. Application of genetic algorithm with multi-objective function to improve the efficiency of glazed photovoltaic thermal system for New Delhi (India) climatic condition. Sol. Energy 2015, 117, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; Kim, J.T. Performance evaluation of photovoltaic/thermal (Pv/t) system using different design configurations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, M.E.A.; Amirat, M.; Kurucz, I.; Bahria, S.; Hamidat, A.; Chaouch, W.B. A detailed thermal-electrical model of three photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) hybrid air collectors and photovoltaic (PV) module: Comparative study under Algiers climatic conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 133, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. A Numerical Investigation of PVT System Performance with Various Cooling Configurations. Energies 2023, 16, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Song, Z.; Jia, B.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, X. Enhancing the Performance of Air-Based Photovoltaic/Thermal (PV/T) Heaters Using Baffles and Metal Foam. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 169, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özakin, A.N.; Kaya, F. Effect on the Exergy of the PVT System of Fins Added to an Air-Cooled Channel: A Study on Temperature and Air Velocity with ANSYS Fluent. Sol. Energy 2019, 184, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojumder, J.C.; Chong, W.T.; Ong, H.C.; Leong, K.Y.; Abdullah-Al-Mamoon. An experimental investigation on performance analysis of air type photovoltaic thermal collector system integrated with cooling fins design. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtadha, T.K.; Alalwany, A.A.H.; Hussein, A.A. The effect of installing different arrangements of aluminum fins on the photovoltaic performance. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, E.; Aktas, M.; Can, O.F. Experimental and numerical investigation of a novel photovoltaic thermal (PV/T) collector with the energy and exergy analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, E. Design and Analysis of a New-Generation Solar-Powered Photovoltaic-Thermal Drying System. Ph.D. Thesis, Gazi University Institute of Science, Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aktaş, A.; Koşan, M.; Aktekeli, B.; Güven, Y.; Arslan, E.; Aktaş, M. Numerical and experimental investigation of a single-body PVT using a variable air volume control algorithm. Energy 2024, 307, 132793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, O.F.; Arslan, E.; Kosan, M.; Demirtas, M.; Aktas, M.; Aktekeli, B. Experimental and numerical assessment of PV-TvsPV by using waste aluminum as an industrial symbiosis product. Sol. Energy 2022, 234, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwania, S.; Siddiqui, A.S.; Agrawal, S.; Kumar, R. Performance Assessment of PVT-Air Collector with V-Groove Absorber: A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 57, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeel, A.E.; Attia, M.E.H.; Khelifa, A.; Kabeel, A.A.; Bady, M. Investigating the Impact of Trapezoidal Fin Length, Thickness, and Positions on the Performance of Photovoltaic Panels with Dual-Inlet Air Cooling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Lei, Y.; Wang, G.; Chan, W.; Wang, T.; Tian, Y. Simulation and Optimization on a Novel Air-Cooled Photovoltaic/Thermal Collector Based on Micro Heat Pipe Arrays. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 255, 127755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuwailhi, A.; Zeitoun, O. Investigating the cooling of solar photovoltaic modules under the conditions of Riyadh. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2023, 35, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi, M.; Siavashi, M.; Norouzi, A.M.; Doranehgard, M.H. Thermal and electrical efficiencies enhancement of a solar photovoltaic-thermal/air system (PVT/air) using metal foams. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 124, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deokar, V.H.; Bindu, R.S.; Potdar, S.S. Active cooling system for efficiency improvement of PV panel and utilization of waste-recovered heat for hygienic drying of onion flakes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 2088–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeroglu, G. CFD analysis and electrical efficiency improvement of a hybrid PV/T panel cooled by forced air circulation. Int. J. Photoenergy 2018, 2018, 9139683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, H.; Sahlaoui, K.; Oueslati, H.; Taghouti, H.; Mami, A. Experimental Comparative Study between PV Solar Collector and Hybrid PV/T Air Collector. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Electrical Sciences and Technologies in Maghreb (CISTEM), Tunis, Tunisia, 26–28 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri, H.; Riahi, J.; Vergura, S.; Taghouti, H. Experimental Validation of the Electrical Performance for PVT Air Collector. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET), Cape Town, South Africa, 16–17 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, H.; Riahi, J.; Oeslati, H.; Taghouti, H.; Vergura, S. Performance Analysis and Optimization of a Channeled Photovoltaic Thermal System with Fin Absorbers and Combined Bi-Fluid Cooling. Computation 2024, 12, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assoa, Y.B.; Sauzedde, F.; Boillot, B. Numerical parametric study of the thermal and electrical performance of a BIPV/T hybrid collector for drying applications. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinbank, W.C. Long-wave radiation from clear skies. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1963, 89, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhaddi, F.; Farahat, S.; Ajam, H.; Behzadmehr, A. Exergetic Performance Assessment of a Solar Photovoltaic Thermal (PV/T) Air Collector. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 2184–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshchimonfared, M.; Bilbao, J.I.; Sproul, A.B. Full Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis of a Photovoltaic–Thermal (PV/T) air System Linked to a Typical Residential Building. Sol. Energy 2016, 136, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Li, J.; Wei, A.; Zhu, T. Performance Analysis of Nanofluid-Based Spectral Splitting PV/T System in Combined Heating and Power Application. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 129, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansys, Inc. CFX-Solver Theory Guide; Release 2021 R2; Ansys: Canonsborg, SC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Enterfea, Correct Mesh Size—A Quick Guide! Available online: https://enterfea.com/correct-mesh-size-quick-guide (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Udemy, CFD Engineer Training. Available online: https://www.udemy.com/course/ansys-fluent-aks-analizleri-uygulamalaryla-cfd-egitimi/learn/lecture/18047423#overview (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Khanjari, Y.; Pourfayaz, F.; Kasaeian, A.B. Numerical investigation on using of nanofluid in a water-cooled photovoltaic thermal system. Energy Conv. Manag. 2016, 122, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Ji, J.; Cai, J.; Yu, B. Experimental and numerical study of the freezing process of flat-plate solar collector. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 118, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofari, C.; Notton, G.; Canaletti, J.L. Thermal behavior of a copolymer PV/Th solar system in low flow rate conditions. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunjo, D.G.; Mahanta, P.; Robi, P.S. Exergy and energy analysis of a novel type solar collector under steady state condition: Experimental and CFD analysis. Renew. Energy 2017, 114, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim Ghasemi, S.; Akbar Ranjbar, A. Numerical thermal study on effect of porous rings on performance of solar parabolic trough collector. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 118, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amber Dunne, N.; Liu, P.; Anas, F.A.; Elbarghthi, A.F.A.; Yang, Y.; Drowak, V.; Wen, C. Performance evaluation of a solar photovoltaic-thermal (PV/T) air collector system. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 20, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Sodha, M.S. Performance evaluation of solar PV/T system: An experimental validation. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousteix, J. Aircraft Aerodynamic Boundary Layers. In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Herrando, M.; Pantaleo, A.M.; Markides, C.N. Markides, Technoeconomic assessments of hybrid photovoltaic-thermal vs. conventional solar-energy systems: Case studies in heat and power provision to sports centres. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.M.; Gupta, R.P.; Mathew, M.; Jayakumar, A.; Singh, N.K. Performance, energy loss, and degradation prediction of roof-integrated crystalline solar PV system installed in Northern India. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 13, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Solar Energy Engineering: Processes and Systems, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Cetina-Quiñones, A.J.; Polanco-Ortiz, I.; Alonzo, P.M.; Hernandez-Perez, J.G.; Bassam, A. Innovative heat dissipation design incorporated into a solar photovoltaic thermal (PV/T) air collector: An optimization approach based on 9E analysis. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 38, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adun, H.; Adedeji, M.; Dagbasi, M.; Bamisile, O.; Senol, M.; Kumar, R. A numerical and exergy analysis of the effect of ternary nanofluid on performance of Photovoltaic thermal collector. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 145, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, N.S.; Fudholi, A.; Mustafa, W.; Yen, C.H.; Mohammad, M.; Ruslan, M.H.; Sopian, K. Exergy and improvement potential of hybrid photovoltaic thermal/ thermoelectric (PVT/TE) air collector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 111, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Othman, M.Y.H.; Sopian, K.; Yatim, B.; Ruslan, H.; Othman, H. Design development and performance evaluation of photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) air base solar collector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, A.; Taheri, A.; Sardarabadi, A.; Ma, T.; Passandideh-Fard, M.; Peng, J. Energy, exergy and environmental analysis of glazed and unglazed PVT system integrated with phase change material: An experimental approach. Sol. Energy 2020, 201, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardarabadi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Kazemian, A.; Passandideh-Fard, M. Experimental investigation of the effects of using metal-oxides/water nanofluids on a photovoltaic thermal system (PVT) from energy and exergy viewpoints. Energy 2017, 138, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusseau, M.L. Sustainable development and other solutions to pollution and global change. In Environmental and Pollution Science, 3rd ed.; Brusseau, M.L., Pepper, I.L., Gerba, C.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milousi, M.; Souliotis, M.; Arampatzis, G.; Papaefthimiou, S. Evaluating the environmental performance of solar energy systems through a combined life cycle assessment and cost analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, H. Energy, exergy, environmental, enviroeconomic, exergoenvironmental (EXEN) and exergoenviroeconomic (EXENEC) analyses of solar collectors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, K.; Naderi, M.; Saghafifar, M. Economic feasibility of developing grid-connected photovoltaic plants in the southern coast of Iran. Energy 2018, 156, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHURA Energy Transition Center. Roof-Top Solar Energy Potential in Buildings—Financing Models and Policies for the Implementation of Roof-Top Solar Energy Systems in Turkey; SHURA Energy Transition Center: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2020; Available online: https://shura.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SHURA-2020-04-Binalarda-Cati-Ustu-Gunes-Enerjisi-Potansiyeli.pdf?utm_source (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Atakale. Tommatech 300 W Monocrystalline Solar Panel—Product Page; Atakale Solar Energy: Kirikkale, Türkiye, 2025; Available online: https://www.atakale.com.tr/index.php?route=product/product&product_id=77 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- SolarAVM. Orbus 300 W Modified Sine Wave 24 V Inverter—Product Page; SolarAVM: Ankara, Turkey, 2025; Available online: https://solaravm.com/orbus-300-watt-inverter-modifiye-sinus-24v (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- BVN Air. Official Website; BVN Air: Arnavutköy, Türkiye, 2025; Available online: https://bvnair.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Robiz.net. Official Website; Robiz.net: Kocaeli, Türkiye, 2025; Available online: https://robiz.net (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Fan Market. Flexible Air Ducts—Product Category; Fan Market: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2025; Available online: https://www.fanmarketi.com/kategori/fleks-hava-kanali (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Investing.com. Copper Futures—Current Price and Market Data; Investing.com: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2025; Available online: https://tr.investing.com/commodities/copper (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Flextab. Insulation: Istanbul, Turkey. 2025. Available online: https://www.flextab.com.tr/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Good, N.; Martínez Ceseña, E.A.; Mancarella, P. Business Cases. In Energy Positive Neighborhoods and Smart Energy Districts: Methods, Tools, and Experiences from the Field; Monti, A., Pesch, D., Ellis, K., Mancarella, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 159–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksa Fırat Electric. Useful Links; Aksa Fırat Electric: Malatya, Türkiye, 2025; Available online: https://www.aksafirat.com/Iletisim/YararliLinkler (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Aksa Malatya Natural Gas Distribution, Co. Aksa Doğalgaz Malatya—Service Area Information. Available online: https://www.aksadogalgaz.com.tr/Dogal-Gaz-Dagitim-Bolgelerimiz/Aksa-Dogalgaz-Malatya (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yousif, J.H.; Kazem, H.A.; Alattar, N.N.; Elhassan, I.I. A Comparison Study Based on Artificial Neural Network for Assessing PV/T Solar Energy Production. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 13, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudholi, A.; Zohri, M.; Rukman, N.S.B.; Nazri, N.S.; Mustapha, M.; Yen, C.H.; Mohammad, M.; Sopian, K. Exergy and sustainability index of photovoltaic thermal (PVT) air collector: A theoretical and experimental study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 100, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV/T Collector | Collector Area | Apvt | 1.5245 | m2 |

| Collector Length | L | 1.6 | m | |

| Collector Width | w | 0.98 | m | |

| Collector Depth | δ | 0.1 | m | |

| Tampered Glass | Thickness | δg | 0.004 | m |

| Specific Heat Capacity | cpg | 500 | J/kgK | |

| Density | ρpg | 3000 | Kg/m3 | |

| Emissivity | εg | 0.92 | - | |

| Absorptivity | αg | 0.05 | - | |

| Conductivity | kg | 1.8 | W/mK | |

| PV Module | Thickness | δpv | 0.0003 | m |

| Specific Heat Capacity | cpv | 677 | J/kgK | |

| Density | ρpv | 2330 | Kg/m3 | |

| Emissivity | εpv | 0.88 | - | |

| Absorptivity | αpv | 0.95 | - | |

| Conductivity | kpv | 148 | W/mK | |

| Transmissivity | τpv | 0.88 | - | |

| Reference Solar Efficiency | ηpv | 0.12 | - | |

| Fin | Thickness | δf | 0.001 | m |

| Specific Heat Capacity | cf | 381 | J/kgK | |

| Density | ρf | 8978 | Kg/m3 | |

| Conductivity | kf | 388 | W/mK | |

| Insulation | Thickness | δins | 0.02 | m |

| Specific Heat Capacity | cins | 880 | J/kgK | |

| Density | ρins | 15 | Kg/m3 | |

| Emissivity | εins | 0.05 | - | |

| Conductivity | kins | 0.041 | W/mK |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Very Good | Good | Acceptable | Bad | Unacceptable |

| 0–0.25 | 0.25–0.50 | 0.50–0.80 | 0.80–0.94 | 0.95–0.97 | 0.98–1.00 |

| Constant | Value |

|---|---|

| 0.09 | |

| 1.92 | |

| 1.44 | |

| (Prandtl Number) | 1 |

| 1.3 |

| Hour | Amb. Air Temp. (°C) | Solar Radiation (W/m2) | Exp. Air Outlet Temperature (°C) | Sim. Air Outlet Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10:15 | 9.2 | 802 | 21.9 | 22.5 |

| 11:15 | 12.1 | 926 | 26.44 | 27.5 |

| 12:15 | 13.4 | 957 | 29 | 29.3 |

| 13.55 | 15.9 | 938 | 32.19 | 31.5 |

| 14:35 | 15.6 | 867 | 29.95 | 30.33 |

| 15:15 | 16.23 | 768 | 29.13 | 29.15 |

| 16:35 | 11.94 | 357 | 17.1 | 17.88 |

| Grid Number | k–ε | k–ω | SST | LES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72,126 | 19.31 | 21.02 | 21.06 | 25.95 |

| 173,852 | 25.24 | 27.49 | 27.54 | 33.93 |

| 256,700 | 27.82 | 30.30 | 30.35 | 37.40 |

| 372,200 | 28.64 | 31.19 | 31.24 | 38.50 |

| 440,518 | 29.10 | 31.68 | 31.74 | 39.11 |

| 530,234 | 29.22 | 31.82 | 31.88 | 39.28 |

| 580,669 | 29.30 | 31.91 | 31.96 | 39.39 |

| Exp. Air Outlet Temperature (°C) [28,29] | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 |

| Percentage Error (%) | 1.03 | 10.03 | 10.21 | 25.83 |

| Parameter | Unit | PV/T-C | PV/T-F | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outlet Air Temperature | °C | 16.32 | 16.55 | 1.41 |

| Average PV Cell Temperature | °C | 27.48 | 23.97 | −12.77 |

| Outlet Air Useful Heat | kWh | 119.76 | 141.45 | 18.11 |

| Annual Electrical Generation | kWh | 364.07 | 369.78 | 1.57 |

| Annual Useful Heat Generation | kWh | 1437.07 | 1697.34 | 18.11 |

| Annual Total Energy Generation | kWh | 1575.42 | 1837.86 | 16.66 |

| Electrical Efficiency | - | 10.71 | 10.99 | 2.61 |

| Thermal Efficiency | - | 45.66 | 54.08 | 18.44 |

| Overall Efficiency | - | 49.72 | 58.26 | 17.18 |

| Exergy Efficiency | - | 11.95 | 12.19 | 2.01 |

| Sustainability Index | - | 1.136 | 1.139 | 0.26 |

| Life Cycle Emissions | kg | 68.53 | 79.95 | 16.66 |

| CO2 Emission Price | USD/year | 0.99 | 1.16 | 17.17 |

| Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) | USD/kWh | 0.0208 | 0.0182 | −12.5 |

| Payback Period | Year | 7.8 | 6.9 | −11.54 |

| No | Author/s | Year | Country | Type of Study | Efficiency (%) | Sustainability Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal | Electrical | Exergy | ||||||

| 1 | Singh et al. [20] | 2015 | India | Numerical | 56.54 | 14.15 | 14.87 | - |

| 2 | Agrawal and Tiwari [19] | 2015 | India | Experimental | - | - | 12.8–17.6 | - |

| 3 | Mojumber et al. [26] | 2016 | Malaysia | Experimental | 56.19 | 13.75 | - | - |

| 4 | Slimani et al. [22] | 2017 | Algeria | Exp. and Num. | 44 | 10.65 | - | - |

| 5 | Özakin and Kaya [25] | 2019 | Türkiye | Exp. and Num. | 33–65 | 25–48 | - | |

| 6 | Fudholi et al. [83] | 2019 | Malaysia | Exp. and Num. | - | - | 12.89–13.36 | 1.15–1.17 |

| 7 | Hussain and Kim [21] | 2020 | Korea | Numerical | 48.25–52.22 | 13.92–14.31 | - | |

| 8 | Arslan et al. [28,29] | 2020 | Ankara, Türkiye | Exp. and Num. | 35.88 | 15.52 | 17.12–18.05 | - |

| 9 | Deokar et al. [37] | 2021 | India | Experimental | - | 13.5–14.7 | - | - |

| 10 | Tahmasbi et al. [36] | 2021 | Iran | Numerical | 85 | - | - | - |

| 11 | Diwania et al. [32] | 2021 | India | Numerical | 41.57 | 10.26 | - | - |

| 12 | Can et al. [31] | 2022 | Diyarbakir, Türkiye | Exp. and Num. | 33.41–49.62 | 11.57–13.17 | - | - |

| 13 | Almuwailhi and Zeitoun [35] | 2023 | Saudi Arabia | Experimental | - | 13.9–16 | - | |

| 14 | Murtadha et al. [27] | 2023 | Jordan | Experimental | 20.7–21.11 | - | ||

| 15 | Cetina-Quinones et al. [61] | 2023 | Mexico | Numerical | 23.34–27.92 | 13.16–13.43 | 13.97–14.58 | 1.162–1.171 |

| 16 | Aktaş et al. [30] | 2024 | Ankara, Türkiye | Exp. and Num. | 34.52–43.68 | 13.42–15.63 | 29.77 | - |

| 17 | Yu et al. [34] | 2024 | China | Numerical | 19.5 | 12.59 | - | |

| 18 | Kabeel et al. [33] | 2025 | Egypt | Numerical | 31.8 | 13.8 | - | - |

| 19 | Tang et al. [24] | 2025 | China | Numerical | 46.5–58.5 | 12.1–14.7 | - | - |

| 20 | Imik and Yilmaz [this study] | 2025 | Malatya, Türkiye | Numerical | PV/T-C: 45.50 PV/T-F: 54.00 | PV/T-C: 11.70 PV/T-F: 11.84 | PV/T-C: 11.95 PV/T-F: 12.19 | PV/T-C: 1.136 PV/T-F: 1.139 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imik, E.; Yilmaz, M. A Numerical Investigation on the Performance and Sustainability Analysis of Conventional and Finned Air-Cooled Solar Photovoltaic Thermal (PV/T) Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310638

Imik E, Yilmaz M. A Numerical Investigation on the Performance and Sustainability Analysis of Conventional and Finned Air-Cooled Solar Photovoltaic Thermal (PV/T) Systems. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310638

Chicago/Turabian StyleImik, Edip, and Mehmet Yilmaz. 2025. "A Numerical Investigation on the Performance and Sustainability Analysis of Conventional and Finned Air-Cooled Solar Photovoltaic Thermal (PV/T) Systems" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310638

APA StyleImik, E., & Yilmaz, M. (2025). A Numerical Investigation on the Performance and Sustainability Analysis of Conventional and Finned Air-Cooled Solar Photovoltaic Thermal (PV/T) Systems. Sustainability, 17(23), 10638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310638