Abstract

Architecture students have a limited understanding of technology’s pedagogical benefits, which creates a gap between the potential of technology-enhanced learning and its actual implementation. A promising solution to this underlying problem would be the integration of GAI in architecture education. The purpose of this study is to explore the role of GAI in architecture education from students’ perspectives. A self-developed questionnaire was employed to collect data from 239 architecture students from three universities in Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Frequency distribution and structural equation modeling (SEM) were employed for data analysis. The study found a low level of awareness and moderate level of perception toward GAI. Integrating GAI into architecture education through knowledge and ethical awareness enhances students’ general skills competency and architecture and design expertise. Students who perceive GAI as beneficial enhance their general skills competency, while those who perceive GAI as challenging undermine their architecture and design expertise. The study also reported that students who intend to integrate GAI in architecture education have high ethical awareness toward GAI and possess a positive perception about GAI while inclining toward its benefits. Students should gain a better understanding of GAI tools and the ways to use them in architecture education in order to improve their general and field-specific skills proficiency. Educators must work with students to enhance their knowledge about GAI and the perception of its benefits and challenges, so that a focused skills development can transform students’ basic competencies to advanced architecture and design expertise.

1. Introduction

The fusion of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) has transformed learning styles and teaching practices in education. GAI is specialized in producing new content by rewriting the previously existing material [1]. Students can learn new concepts easily in an immersive, interactive, and engaging way [2]. Teachers can easily adapt to a new teaching style which cannot be achieved in traditional settings [2]. GAI provides personalized feedback, assists in language learning, and generates content tailored to diverse educational needs, hence fostering basic and field-specific competencies [3]. Considering its importance in ongoing digital transformation, the integration of GAI in any field of education is perceived as a learning tool that offers personalized educational experiences for students [4].

Likewise, the GAI integration in architecture education can enhance creativity, personalization, critical thinking, efficiency, and sustainability [5]. This highlights the importance of advancing AI technologies to streamline construction workflows, enable customized learning experiences, and enhance project management efficiency [6]. The integration of AI and other technologies within the architecture, education, and construction (AEC) industry needs to address the changing requirements of 21st-century education [6,7,8]. For instance, GAI tools, such as ChatGPT-3 and AI Image Creator, enable architecture education to generate the relevant and context-specific outputs after receiving prompts that guide these tools [9,10]. Similarly, Building Information Modeling (BIM) is commonly used in the AEC industry for 3D visualization, feasibility analysis, clash detection, environmental/LEED analysis, quantity take-off, constructability review, 4D/scheduling, leading to enhanced construction efficiency, collaboration, and knowledge sharing among team members [11]. Thus, GAI can foster both personalized education and efficient project management, which leads toward continuous professional development [6].

The current status of digital transformation in architecture education articulated that GAI has transformed the previously specialized design skills being taught in architecture education, such as parametric and digital design, into baseline competencies [12,13]. However, the current curricula do not align with such emerging technologies or do not offer such courses. The existing literature strongly suggested that AI should digitize conventional teaching, which makes learning easier, efficient, and tailored to students’ needs [14]. In a similar manner, AI must be integrated into architecture education to foster advanced architectural skills and competencies among students [15]. However, only a few studies have assessed the need of AI, especially GAI, in architectural education [5,16,17,18]. Onataya et al. [6] explained several educational approaches that can be employed to prepare AEC students and professionals to adopt GAI tools in their work. Huh et al. [19] reported that architecture students perceive image-based GAI tools as ethically acceptable and supportive in the early stages of design processes but avoid them in later design stages to bring creativity, originality, and critical judgment in their learning and practice. Memon et al. [20] highlighted that students and professionals in the AECO industry often train AI models for achieving quicker results, ensuring efficient use of resources, and improving quality. Dullinja & Jashanica [21] reported a strong enthusiasm and familiarity with AI tools in architecture learning contexts while compromising over-reliance on AI and resultant creative thinking. Alshahrani & Mostafa [15] reported an educational gap between awareness and usage of AI technologies in architecture education in Kosovo and North Macedonia. Nevertheless, AI integration from the learning sciences, such as self-regulated learning, cognitive load theory, and constructivism, still needs to be explored in order to determine how GAI impacts motivation, creativity, and critical thinking in different educational settings [22]. The integration of GAI in architecture education is a novel concept that needs to be addressed with thorough investigation [23]. Hence, the research gap of assessing the role of GAI in architectural education still prevails, especially for determining how the technical and ethical awareness of GAI would develop students’ skills and competencies and foster their willingness to adopt these tools in their education.

As part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, several efforts towards sustainability have been made which also aligns with UN’s Sustainable Development Goals [24] and national sustainability goals [25]. This ensures that educational reforms support broader environmental and societal objectives. Under Saudi Vision 2030, the evolution of the architectural sector is continuously in progress, in which architects essentially promote sustainable environmental design as a core competency. Such a design can only be achieved when pollution and waste are reduced and energy consumption in new sustainable buildings can be minimized [26]. Waste generation is expected to increase to 30 million tons by 2033 [27,28], while Saudi’s building sector consumes approximately 75% of its total electricity production, which is equivalent to 29% of the primary energy sector [29,30]. Hence, Saudi Arabia is bound to design energy-efficient and sustainable buildings, whereby the architects develop and implement environmentally responsive strategies such as ‘green’ architecture in order to reduce waste generation and sustain urban development [24]. Considering its importance, it is important for architecture students to learn advanced ways of design energy-efficient and sustainable building in line of UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and national sustainability goals under Saudi Vision 2030. Only trained students who are equipped with the knowledge and ethical awareness and perceive it as beneficial can move towards sustainability in their future career.

Past literature revealed that only a small proportion of students ever heard of GAI technologies for academic purposes [31,32,33]. Generally, students highly favor the potential of AI to enhance results, simplify complex academic tasks, generate novel insights, and foster innovation as compared to teachers [34]. Students find it beneficial due to time-saving, ease of access and instant feedback but, at the same time, challenging because of unreliable information, high subscription fees, reduced human-to-human interaction, risk of plagiarism, and low level of learning autonomy [35]. These technologies strongly discourage students to use their creativity and critical thinking in learning processes, which creates a critical need to evaluate the process of learning over its outputs, besides higher-order thinking and authentic applications [10]. To fill in this gap, the current study mainly seeks to explore the role of GAI in architecture education from students’ perspectives. The ultimate goal of architecture education is to develop skills proficiency (both general skills and architecture and design expertise) among students in order to prepare students to become competent, responsible, and innovative architects. With GAI as the focal point of study, an effective approach to enhance behavioral intention toward GAI would be to enhance students’ knowledge regarding the use of GAI, inform ethical concerns of integrating GAI in the learning process, and create a positive perception by informing and balancing between benefits and challenges of GAI. Such awareness and perception would create architecture students’ willingness to use GAI. Such hybrid learning processes—a combination of human expertise and the expertise of GAI—would develop architecture and design expertise along with the general skills proficiency of architecture students. Hence, the study seeks to answer the following research sub-objectives:

- To explore the level of architecture students’ awareness and perception regarding GAI in terms of knowledge toward GAI, AI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges;

- To explore the role of GAI in architecture education by investigating how knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges contribute to developing skills; and

- To explore the role of GAI in architecture education by investigating the impact of knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges contribute to enhancing behavioral intention toward GAI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Behavioral Intention Toward GAI

Behavioral intention toward GAI is referred to as the individual’s willingness to use or integrate GAI in architecture education [36]. It is a central concept in many technology acceptance and adoption theories, including Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). These theories investigated factors that directly or indirectly shape behavioral intention toward adopting GAI technologies, which directly influence actual behavior to use GAI, hence achieving the ultimate goal of all technologies. Past literature extensively studied the behavioral intention to adopt GAI in architecture education. For instance, Qlughara et al. [37], Xin et al. [38], and Zhao et al. [39] applied the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and reported that students’ behavioral intention toward GAI is positively related to their usage behavior. Understanding users’ behavioral intentions is beneficial for predicting technology adoption and developing design strategies [40]. Considering its underlying context, the current study explores the behavioral intention toward GAI, as architecture students’ adoption of GAI is directly influenced by the behavioral intention toward GAI that, according to TAM, form the result of conscious decision-making [41].

2.2. Skills Development

The current study comprehended skills development in two components: general (i.e., general skills proficiency) and field-specific skills (i.e., architecture and design expertise). These components altogether are termed as ‘employability skills’, which are the broader set of skills and personal attributes that go beyond discipline knowledge and technical skills, and are essential for success in the workplace [42]. Specifically, the study defined ‘general skills proficiency’ (i.e., the first component) as the broad and transferrable skills that are not tied to a specific field or technical expertise and are necessary for skills development in every field. These included teamwork, knowledge sharing, leadership skills, cross-communication skills, problem identification, time management skills, and knowledge acquisition [43,44]. The second component—architecture and design expertise—is categorized into three forms of employability skills, following classification presented in Abowardah et al.’s [45] study: (i) fundamental skills, including communication, critical thinking, and problem-solving; (ii) management skills, including positive attitudes, behaviors, responsibility and adaptability, learning continuously and working safely; and (iii) teamwork skills, such as taking part in projects and working collaboratively. The general skills proficiency and architecture and design expertise altogether reflect in employees’ and graduates’ soft skills and technical skills, which essentially enhance efficiency in architecture and construction projects and predict construction costs [45,46,47]. These employability skills were, especially, considered as a source of employers’ satisfaction when they hired fresh IT engineers [48]. Additionally, skills development comes with critical changes in teaching environment, including changes in courses contents, changes in acquired skills, applying effective teaching strategies, and changing the nature of coursework [47]. Following Lang et al. [49], the current study proposed that all these changes in architecture education can be implemented through the integration of GAI in this underlying education.

2.3. Knowledge Toward GAI

Knowledge toward GAI refers to the individual’s awareness and familiarity with AI-related technologies, including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL). Various sources contribute to the acquisition of AI knowledge, including the internet, peer discussions, and formal training courses [15]. The combination of knowledge, experience, and skills forms the foundation of AI competencies necessary for completing academic tasks and assignments [50].

A recent systematic review identified that individuals in developed countries tend to have significantly higher familiarity with GAI compared to those in developing or semi-developed countries like Saudi Arabia [51]. Alshahrani & Mostafa [15] revealed that 58.8% of the architecture students enrolled in Saudi Arabia had a high level of awareness of AI. In a related study, Almogren [52] explored the integration of AI in visual arts and design courses (VADC) and found that outcome expectations, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and job availability had a significant positive influence on students’ awareness of studying the VADC, which subsequently enhanced their academic performance.

In general, Dullinja & Jashanica [21] identified that almost all architecture students in Kosovo and North Macedonia (99.6%) are aware of AI, and only 71.1% of them use AI in their work. The study conducted in Saudi higher education institutions (HEIs) indicated that 76.6% of students had experience using e-learning platforms, with 50.5% having used these tools for two years. Comparatively, students and educators from other developed countries such as Australia, USA, Kosovo, and North Macedonia reported a high level of awareness of GAI tools and usage in education, while students from underdeveloped countries like Cyprus highlighted a lower level of awareness and usage [21,33]. Furthermore, 81% of the students valued IoT as a learning platform for e-learning [53]. Another study conducted in Saudi Arabia and three other Middle East nations found out that 71% of students possessed moderate to high familiarity with AI image generation [54].

2.4. GAI Ethical Awareness

Besides technical awareness, ethical awareness is equally important for a successful and sustained implementation of GAI [55]. Over-reliance on GAI may limit students’ creativity, originality of their work, resulting in a strong call of bringing ethics into GAI technologies [56]. The rapidly growing use of AI, particularly GAI, in architecture education demands to address the ethical implications of their usage. In educational settings, ethical concerns of GAI arise primarily around issues of transparency, bias and fairness, data security, privacy, digital divide, data protection, accountability, and copyright and intellectual property concerns [6,14,57,58]. Especially with learning analytics, the ethical concerns involve, but are not limited to, informed consent and privacy, data management, the interpretation of data and obtained results, and perspectives of data specific to analysis as well as concerns of surveillance, power relations, and purpose of education in a broader sense [59]. The confidentiality of sensitive project data creates a concern for data security and privacy breaches, which can be minimized with cybersecurity measures [6,60]. In particular, architecture students face several ethical challenges in utilizing Large Language Models (LLMs) such as low technological readiness, lack of replicability, lack of transparency, insufficient privacy, and insufficient beneficence [61].

2.5. Perceived GAI Benefits

A recent study conducted by Elrawy & Wagdy [62] highlighted that the Prompt-Based AI Generation applications can potentially speed up the design process, create new and innovative design ideas, reduce workload for human designers, enhance precision and accuracy, smoothen the communication between clients and designers, create more creative opportunities, and increase non-designers’ accessibility to designs. Ceylan [63] highlighted that AI assists architects in developing innovative design, enhancing building efficiency, and redesigning construction models using advanced AI algorithms. Accordingly, architecture students must learn to creatively operate AI and perceive its full potential with regard to their career progression and design identity [63]. A similar study conducted by Nermen & Nevine [64] highlighted that AI technologies assist in streamlining work activities and managing non-creative, administrative tasks in an efficient manner. This permits students and professional architects to have more time to carry out innovative processes and enhance productivity [64,65].

Another advantage of AI integration in architecture education lies in its ability to solve challenges and transform teaching methods, which assist in achieving SDG 4 [66]. Generative AI goes beyond replicating AI-provided solutions; rather, it develops and influences novel concepts, which promote originality and creativity in design solutions, enhances the quality of design outputs, and reduces cognitive load [67]. GAI is also equipped with emotional intelligence, as it can assess students’ emotional responses, create customized teaching strategies, and foster a dynamic learning environment based on that emotional data [23]. It also offers interactive lessons, immediate assistance, and personalized feedback, which assist architecture students in continuing meaningful learning and staying proficient in drawing and 3D design software [23].

2.6. Perceived GAI Challenges

The fit between AI-generated conceptual design models and the goals of architecture education remains problematic, as such tools often limit user control over design outcomes, restricting the pedagogical emphasis on authorship, iteration, and critical decision-making [60,68]. These issues are highly relevant to architecture education, where students are expected to produce coherent, contextually responsive, and structurally viable designs. AI-generated outputs that are stylistically inconsistent or disconnected from real-world constraints can hinder the development of these foundational skills [68]. This necessitates critical engagement with AI tools, encouraging students to assess, adapt, and refine outputs to align with project requirements and pedagogical goals [6].

In architecture education, the integration of text-to-image AI tools presents challenges, as students often struggle to align AI-generated content with established design workflows and practices [62]. While these tools offer the potential to enhance efficiency, it is essential that they complement rather than replace human creativity—preserving the critical ‘human touch’ that underpins architectural authorship and innovation [69]. Students are unable to consider context and cultural factors in utilizing text-to-image AI applications in design due to limited non-technical awareness of tools, inexperienced prompting, lack of proper understanding of context, and ineffective integration [62,70]. Text-to-image AI applications, such as DALL-E, Midjourney, or Stable Diffusion, offer limited flexibility and customization options that hinder students and other potential users from accurately unfolding anticipated outputs and limit students’ ability to handle complex design problems [62,71].

2.7. Benefits–Challenges Trade-Offs

Balancing benefits against challenges would assist in optimizing students’ personal and professional growth as well as create a willingness to adopt GAI in architecture education. It also helps in understanding the limits of GAI technologies that would influence the learning processes of architecture students. In general, the usage of GAI chatbots in education enhances task planning, deepens metacognitive reflection, and encourages adaptive strategy use while creating a risk of over-reliance on GAI and inaccuracy of its generated content [72]. In the context of the present study, the utilization of GAI in higher education allows for continuous improvement in technology and a strong emphasis on context-dependent technology utilization while creating issues of data reliability, privacy, personal irresponsibility, reduced human involvement, and several ethical concerns [73]. To mitigate this issue, students with more developed AI skills, or AI literacy, tend to have a deeper understanding of AI technology, enabling them to assess its risks and benefits more effectively [74].

A comparative table of related work showing focal areas, methodology/approach, context/population, and key findings/contribution is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative table of related work.

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Impact of Knowledge Toward GAI on Skills Development

Knowledge toward AI, or mastering and understanding GAI technologies, can influence students’ skills development in general and at specific levels. For career development, it is important to develop competency in both basic-level skills (i.e., in this case, general skills proficiency) or specific subject-related skills (i.e., in this case, architecture and design expertise). Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy suggests that how one’s belief in his capabilities can influence his perseverance, decision-making, and actions [75]. The growth mindset theory implies that students with an innovation mindset view AI integration as a learning opportunity, not a hurdle, adopt a growth mindset, and enhance their self-efficacy [76,77]. High knowledge toward AI, or AI literacy, ensures that these skills are useful and easy to use or integrate into learning practices and, hence, reinforce their innovation mindset [78]. The study proposed the following:

H1:

Knowledge toward GAI is positively related to general skills proficiency.

H2:

Knowledge toward GAI is positively related to architecture and design expertise.

3.2. Impact of AI Ethical Awareness on Skills Development

GAI ethical awareness, or knowledge of ethical implications of GAI usage, may induce the students to learn the skills by themselves and avoid unethical behavior in academic writing. GAI usage can create the problems of copyright infringement, plagiarism detection, authorship breach, and attribution concerns [79]. Integrating ethical education into the curriculum would be an effective strategy for preparing future students to deal with ethical challenges and ongoing innovation in architecture industry [6,80]. Training on the technical, practical, and ethical aspects of AI application in architecture education would improve students’ writing, moral reasoning, critical thinking, and self-awareness of personal values and biases [81]. Hence, the study proposed the following:

H3:

AI ethical awareness is positively related to general skills proficiency.

H4:

AI ethical awareness is positively related to architecture and design expertise.

3.3. Impact of Perceived GAI Benefits on Skills Development

Despite several other benefits, students perceive GAI as a valuable tool to enhance students’ learning experience. Its ability to respond to user prompts tends to produce high quality and original output. GAI applications such as ChatGPT brainstorm ideas and give feedback on written contents [82]. Equipped with emotional intelligence, it is viewed as valuable for teaching technical and artistic concepts in arts and design to architecture students [23,67]. It brings about creativity and efficiency while balancing it with automated precision within complex operational models [83]. Architects employed advanced AI-powered design tools to develop innovative design, enhance building efficiency, and redesign construction models, which drive student’s personal and professional growth [6,63]. The expectancy–value theory implies that students who often look for the perceived value generated from the combination of AI and human competencies are more likely to be motivated to pursue a task [84]. Hence, the study proposed the below:

H5:

Perceived GAI benefits are positively related to general skills proficiency.

H6:

Perceived GAI benefits are positively related to architecture and design expertise.

3.4. Impact of Perceived GAI Challenges on Skills Development

When students properly addressed challenges they faced while implementing GAI, they can enhance learning practices that can result in the development of general or field-specific skills. For instance, a major challenge faced by rural students is accessibility, which occurs due to the digital divide and prevents them from having equitable access to AI-empowered learning practices, leading to a hindrance in developing digital literacy skills in general [85]. Students may also require to have a certain level of linguistic skills to construct appropriate academic writing prompts [86]. Falsified information or misinformation require human oversight for validity of content produced by GAI [87]. Lack of accuracy and transparency create an obstacle to public trust, and require a human eye to guarantee verification [79,88]. The expectancy–value theory implies that students who often believe in themselves to overcome GAI challenges and look for the perceived value generated from the combination of AI and human competencies are more likely to be motivated to pursue a task [84]. Hence, the study proposed the below:

H7:

Perceived GAI challenges are positively related to general skills proficiency.

H8:

Perceived GAI challenges are positively related to architecture and design expertise.

3.5. Impact of Knowledge Toward GAI on Behavioral Intention Toward GAI

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) recognized that knowledge, along with competence, can influence behavioral intention among university students [89]. It explained that students’ proficiency in GAI technology is directly related to the controllability and effectiveness of their actions and behaviors [89]. Mastering and understanding GAI technology enhances students’ confidence and embraces their ability to control their actions [90]. Having a higher level of AI knowledge significantly improves students’ willingness to use it in future practice [91]. Hence, the study proposed the following:

H9:

Knowledge toward GAI is positively related to behavioral intention toward GAI.

3.6. Impact of GAI Ethical Awareness on Behavioral Intention Toward GAI

TPB theory identified that AI ethical awareness showed a positive influence on behavioral intention toward AI [89]. It explained that when users can have a stronger sense of control over GAI technology, they tend to display a stronger behavioral intention [92,93]. AI ethical awareness, or possessing a better and more comprehensive understanding of ethical concerns relating to the usage of GAI, makes students more confident in handling controllable ethical concerns and hence enhances a behavioral intention toward GAI in line of ethical principles [94]. Hence, the study proposed that

H10:

AI ethical awareness is positively related to behavioral intention toward GAI.

3.7. Impact of Perceived GAI Benefits on Behavioral Intention Toward GAI

Perceived benefits of GAI explained the potential advantages that a user perceives to have while employing technology for the enhancement of work efficiency and performance. If the students perceive them more helpful and advantageous in their learning, they are more likely to use and accept AI technologies [95]. The TAM supported this notion that it signifies the important impact of perceived usefulness and relative benefit on willingness or behavioral intention to use GAI [96]. Similarly, the innovation diffusion theory also signifies that relative advantages, or higher level of usefulness of e-learning systems, can enhance students’ behavioral intention to use GAI [97]. It is hypothesized that

H11:

Perceived GAI benefits are positively related to behavioral intention toward GAI.

3.8. Impact of Perceived GAI Challenges on Behavioral Intention Toward GAI

Students perceive to face several GAI challenges, which, if addressed properly, can enhance behavioral intention toward GAI. Over-reliance on AI may hinder students’ skills and intellectual development over time [79,98]. Its usage also poses privacy and security risks due to lack of proper protection of these technologies, which may reduce students’ intention to use GAI [99]. GAI also poses a threat of job replacement or job displacement that might make it difficult to find employment or catch up, which may stop students from utilizing GAI in architecture education [100]. GAI may also cause social injustice and inequality that affect the student–teacher relationship, hence leading to reduction in behavioral intention toward GAI [101]. These challenges aligned with automation theory, which suggested that technology advancements often generate fears of job displacement [62,102]. Hence, the study proposed

H12:

Perceived GAI challenges are negatively related to behavioral intention toward GAI.

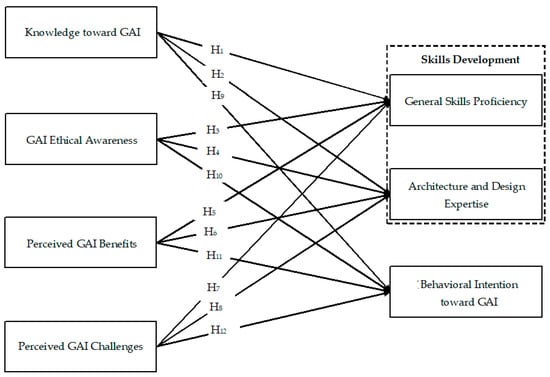

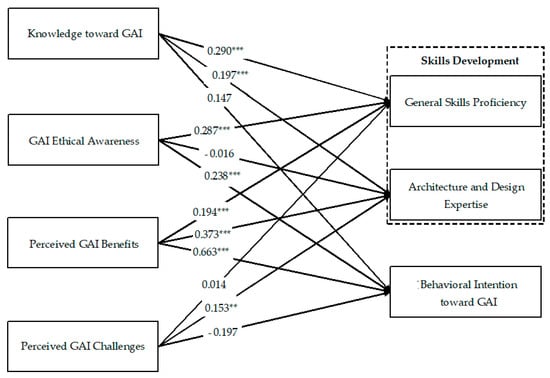

In summary, a research model was constructed for combining seven latent variables, including knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, perceived GAI challenges, general skills proficiency, architecture and design expertise, and behavioral intention toward GAI, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Approach and Design

A cross-sectional research design was employed to explore the role of GAI in architecture education by presenting the respondents’ knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges as well as assessing the impact of knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges on skills development and behavioral intention toward GAI. Such a design enables the collection of data once at a time to explore the underlying topic in the current state of architecture education. Students enrolled in architecture and design courses taught in Saudi and Egyptian universities are primarily the target population of this study, as they primarily learn and adapt new skills from the integration of GAI in architecture education. The questionnaire survey was spread among Saudi and Egyptian universities between June 2025 and July 2025 via online Google Forms.

4.2. Sample and Sampling Method

The study employed purposive sampling to match target respondents (i.e., architecture students) with the context of the study (i.e., architecture education). In particular, the current study involved approximately 350 architecture students from the Faculty of Architecture and Design at Prince Sultan University—Saudi Arabia, Egypt-Japan University of Science and Technology—Egypt, and British University in Egypt—Egypt. These universities were selected due to the accessibility and appropriateness of the study population to the purpose of the study. The actual sample consisted of 239 undergraduate and postgraduate students who consented to participate in the survey and returned a completed questionnaire. G*Power version 3.1.9.4 was employed to estimate the minimum sample size of 222 [103]. This calculation was based on the parameters of 5% f2 effect size, 5% α alpha error, 80% power (1 − β), and 3 predictors in total. The sample size employed in each university was shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample size from selected universities.

4.3. Measurement Instruments

The study tool consisted of the following sections:

- Educational background: University name, Year of study

- AI proficiency and experience: Proficiency in using digital tools (e.g., AutoCAD, Rhino, Revit) (Beginner/Intermediate/Advanced/Expert), Usage of GAI technologies (e.g., ChatGPT, Large Language Models, Foundation Models) (Never/Rarely/Sometimes/Often/Always)

- Knowledge toward GAI (6 items)

- GAI Ethical Awareness (3 items)

- Perceived GAI Benefits (7 items)

- Perceived GAI Challenges (9 items)

- General Skills Proficiency (15 items)

- Architecture and Design Expertise (9 items)

- Behavioral intention toward GAI (8 items)

The study adopted the measurement instrument to measure the general skills proficiency and architecture and design expertise from the study of Abowardah et al. [45]. Using Cronbach’s α, the reliability of this scale in the original study was found to be 0.956 when surveyed for both employers and graduates [45]. However, the study designed the measurement instruments to measure the behavioral intention toward GAI, knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges after a careful review of the literature [4,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111]. The self-developed questionnaire was thoroughly reviewed and approved by a panel of experts including two faculty members from the Faculty of Administrative Sciences, four faculty members from the Faculty of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), and two independent reviewers from the Ministry of Commerce. All statements for section 3 to section 9 were measured on a five-point Likert scale, starting from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. A copy of the questionnaire is attached in Appendix A.

4.4. Pilot Study

A pilot study involving 40 respondents was also conducted to assess the internal consistency of the key survey variables. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all study variables were above the recommended threshold of 0.70 [112], indicating acceptable reliability (Knowledge toward GAI: α = 0.767; GAI ethical awareness: α = 0.721; Perceived GAI benefits: α = 0.822; Perceived GAI challenges: α = 0.852; General skills proficiency: α = 0.872; Architecture and design expertise: α = 0.823; Behavioral intention toward GAI: α = 0.846).

4.5. Data Analysis

Data was, firstly, assessed for missing data using missing data analysis, outliers using boxplots, and normality using normal probability plots. Moreover, frequencies and percentages were computed to describe the demographic characteristics, while mean and standard deviations were used to report the quantitative data. The study also presented 100% stacked horizontal bar charts to explore the perception and behavioral intention toward GAI. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to explore the correlative relations among the study variables and to model these relations with one or more observed or measurable variables. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm the factor structure and evaluated the reliability and validity of study variables. Covariance-based Structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) was conducted to assess the proposed relationships between the study variables. Data was recorded in IBM SPSS version 29 and then analyzed in SPSS AMOS version 26.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

To ensure transparency, the researchers clearly described the topic and purpose of the study. Moreover, to ensure voluntary participation, the study asked to consent for their voluntary participation in the research study and gave them withdraw from participation at any time. Furthermore, to ensure anonymity and privacy, the survey did not ask for any personal information (e.g., name, address, phone number, email address, etc.) from the participants.

5. Results

5.1. Composition of Educational Level and Technological Proficiency

Table 3 presents the frequency distribution that portrayed the composition of the study population in terms of educational level and technological proficiency. In terms of current year of study, most of the study population were at the time enrolled in the second year (33.5%), while the remaining study population were equally proportional across the first year (21.8%), third year (21.8%), and fourth year (21.8%). A small study population was also currently enrolled in a post-graduate year (1.3%). Moreover, in terms of usage, nearly 40% of the study population reported to sometimes use GAI technologies (e.g., ChatGPT, Large Language Models, Foundation models), while 26.4% reportedly often use GAI technologies. A few respondents either never used or always used GAI technologies (10%). Lastly, in terms of proficiency, most of the sampled architecture and design students reported to have an intermediate (39.7%) or advanced (36.8%) level of proficiency in using digital tools (e.g., AutoCAD, Rhino, Revit).

Table 3.

Frequency distribution—composition of educational level and technological proficiency.

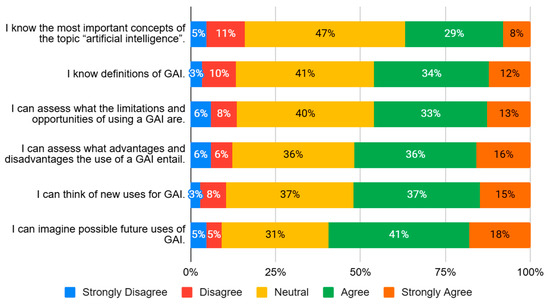

5.2. Knowledge Toward GAI

A clustered bar chart was designed to describe the composition and proportion of respondents’ knowledge toward GAI, as shown in Figure 2. The graph indicated that responses were rated either neutral or agree on all the statements of ‘knowledge toward GAI’ (28.5–41.4%), with neutral in greater proportion. Furthermore, around one-tenth to two-tenths of the respondents (8.7–18.0%) strongly agreed with having sufficient knowledge about GAI. An overall trend shown in Figure 2 revealed that respondents reported having a good understanding of generative AI.

Figure 2.

Clustered bar chart—knowledge toward GAI.

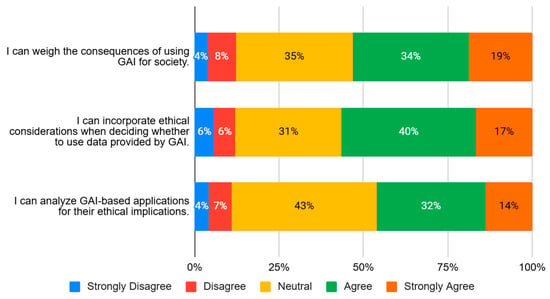

5.3. GAI Ethical Awareness

A clustered bar chart was used to portray the number and percentage of respondents’ GAI ethical awareness, as shown in Figure 3. The results indicated that a majority of responses were equally proportionate in terms of being neutral (31.4–42.7%) or agreeing (32.6–39.8%) when asked about assessing GAI-based applications for their ethical implications, weighting consequences of using GAI for society, and incorporating ethical considerations while using GAI. Furthermore, around 13.8–18.8% of the respondents strongly agreed with giving adequate ethical consideration before using GAI. An overall trend shown in Figure 3 revealed that respondents reported a moderate level of ethical awareness toward GAI.

Figure 3.

Clustered bar chart—GAI ethical awareness.

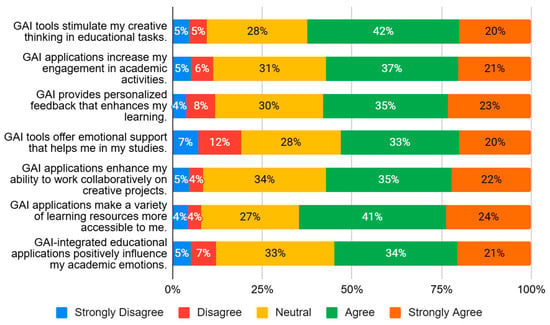

5.4. Perceived GAI Benefits

A clustered bar chart was computed to describe the composition of responses for the perceived benefits of GAI, as shown in Figure 4. The results indicated that a majority of respondents agreed to have stimulated their creative thinking in educational tasks (42.3%). Most of the respondents either agreed (36.8%) or were neutral (31.4%) with having their engagement increased in academic activities. Nearly one-third of the respondents agreed with GAI being useful in providing personalized feedback that enhances their learning (34.7%) and offering emotional support that helps them in their studies (32.6%). Most of the respondents were either neutral (33.9%) or agreed (34.7%) with GAI being useful in enhancing their ability to work collaboratively on creative projects. Nearly 41% of the respondents find GAI beneficial in making a variety of learning resources more accessible to them. Lastly, most of the respondents were neutral (33.0%) or agreed (34.3%) with GAI having a positive influence on students’ academic emotions. An overall trend shown in Figure 4 revealed that respondents reported that GAI is highly beneficial for academic learning and skills development.

Figure 4.

Clustered bar chart—perceived GAI benefits.

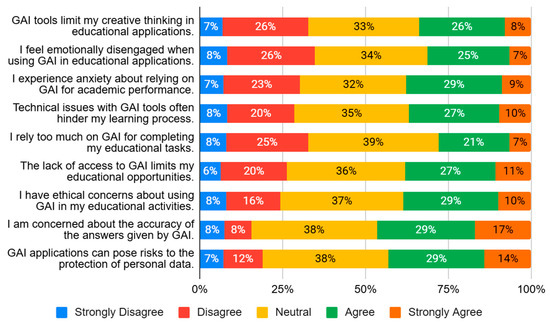

5.5. Perceived GAI Challenges

A clustered bar chart was computed to describe the number and percentage of respondents’ responses to the agreement of the perceived GAI challenges, as shown in Figure 5. The results indicated that a majority of the respondents were neutral with all the mentioned challenges GAI pose to them (32.2–39.3%). However, these concerns were rated different among all the remaining responses: respondents either disagreed (25.9%) or agreed (25.5%) with GAI putting a limitation on their creative thinking in educational applications. Furthermore, respondents either disagreed (26.4%) or agreed (24.7%) with being emotionally disengaged when using GAI in educational applications. Similar findings were reported when they were inquired about anxiety levels (D: 23.4%, A: 28.9%), technical issues hindering the learning process (D: 20.1%, A: 27.2%), reliance on GAI for completing their educational tasks (D: 24.7%, A: 21.3%), and lack of access resulting in limitation on educational opportunities (D: 20.1%, A: 27.2%). However, the second largest rated category was the ‘agree’ response when students were asked about ethical concerns about using GAI in their educational activities (28.5%), the accuracy of the answers generated by GAI (29.3%), and risks to the protection of personal data (28.9%). An overall trend shown in Figure 5 revealed that respondents reported a high probability of challenges in terms of reduced creative thinking, emotional disengagement, stress, and data compromise.

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution—perceived GAI challenges.

5.6. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to assess the factor structure of self-developed measurement instruments used to measure each study variable (Table 4). The results indicated that the Barlett Test of Sphericity was 11650.617 (p < 0.001). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.939, showing that the data was suitable for factor analysis. The 57 items were assessed via the Maximum Likelihood extraction method, using a varimax rotation. The varimax rotation method is appropriate for structural equation modeling in the current study, as it expects the latent variables to be uncorrelated, allowing us to explore the latent structure and simplify interpretation [113]. The analysis extracted seven factors that explained, based on the initial solution, 65.261% of the total variances. It confirmed the factor structure, indicating that all items designed to measure one particular variable fell under a single factor. For instance, all statements measuring ‘behavioral intention toward GAI’ fell under factor 2, hence named as behavioral intention toward GAI. Hence, the results confirmed the factor structure of all study variables.

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis: rotated component matrix.

5.7. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of all study variables as well as to evaluate how well the model fits the data (Table 5 and Table 6). Firstly, the standardized factor loadings (SFL) of all items were higher than the threshold level of 0.70 as suggested by Hair et al. [114] (Table 3). Secondly, for reliability, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and the composite reliability (CR) scores of all study variables are computed and lie within the threshold level of 0.70 and 0.95 as suggested by Hair et al. [114] (α: 0.890–0.949; CR: 0.891–0.949) (Table 5). Hence, the reliability of all study variables was acceptable. Thirdly, for convergent validity, average variance extracted (AVE) scores of all study variables (0.553–0.731) were computed and higher than the threshold level of 0.50 (Table 5). Hence, convergent validity was achieved. Fourthly, for discriminant validity, maximum shared variance (MSV) scores were computed and found to be lower than AVE (Table 5). Furthermore, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was assessed and it found that the AVE scores of all study variables were higher than its highest correlation with any other constructs (Table 6) [115]. Hence, discriminant validity was achieved as well. Lastly, all model fit indices of measurement models fell within the suggested threshold level (Table 7), reflecting that it fits well with the data and represents the underlying relationships in the data. Hence, the model fit of the measurement model was achieved. The mean and standard deviation of all items representing each study variable was reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Construct reliability and convergent validity.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity.

Table 7.

Model fit indices.

5.8. Descriptive Statistics

Mean and standard deviation were computed to describe the average scores and variability in scores of all study variables, including knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, perceived GAI challenges, general skills proficiency, architecture and design expertise, and behavioral intention toward GAI (Table 8). The results indicated that all variables, except for ‘perceived GAI challenges’, were rated as ‘agree’ on average. However, respondents rated the statements of the variable ‘perceived GAI challenges’ as neutral. Furthermore, skewness and kurtosis were computed to assess normality. The results in Table 8 indicated that skewness ranged from 0.089 to 2.177 that fell in between ±3, while kurtosis ranged from −0.475 to −1.127 that fell in between ±7. Since both skewness and kurtosis fell within the threshold level as suggested by Byrne [116] and Hair et al. [117], normality was achieved.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics.

5.9. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to assess the association between study variables (Table 9). The results indicated that behavioral intention toward GAI was significantly associated with knowledge toward GAI (r = 0.541, p < 0.001), GAI ethical awareness (r = 0.589, p < 0.001), general skills proficiency (r = 0.610, p < 0.001), architecture and design expertise (r = 0.429, p < 0.001), perceived GAI benefits (r = 0.760, p < 0.001), and perceived GAI challenges (r = 0.210, p < 0.001). Similarly, both general skills proficiency and architectural and design expertise were significantly associated with knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges (p < 0.001). This confirmed the assumption of linearity.

Table 9.

Pearson’s correlation analysis.

5.10. Path Analysis—Structural Equation Analysis (SEM)

To explore the role of GAI in architecture education, the study further assessed knowledge and ethical awareness as well as the perception of its benefits and challenges on skills development (i.e., general skills proficiency and architecture and design expertise) and willingness to adopt GAI (i.e., behavioral intention toward GAI). For this purpose, Covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) was conducted (Figure 6). All model fit indices of the structural model fell within the suggested threshold level (Table 7), reflecting that it fits well with the data and represents the underlying relationships in the data. Hence, the model fit of the structural model was achieved. The path analysis results in Table 10 indicated that knowledge toward GAI (β = 0.290, t = 3.569, p < 0.001), GAI ethical awareness (β = 0.287, t = 4.157, p < 0.001), and perceived GAI benefits (β = 0.194, t = 3.820, p < 0.001) had a significant and positive impact on the general skills proficiency of architecture students. However, perceived GAI challenges did not have a significant impact on the general skills proficiency of architecture students (β = 0.014, t = 0.310, p = 0.757). Hence, hypotheses H1, H3, and H5 were accepted, while hypothesis H7 was rejected. Furthermore, knowledge toward GAI (β = 0.197, t = 2.046, p < 0.05), perceived GAI benefits (β = 0.373, t = 5.666, p < 0.001), and perceived GAI challenges (β = 0.153, t = 2.745, p < 0.01) had a significant and positive impact on the architecture and design expertise of architecture students. GAI ethical awareness did not have a significant impact on the architecture and design expertise of architecture students (β = −0.016, t = −0.202, p = 0.840). Hence, hypotheses H2, H6, and H8 were accepted, while hypothesis H4 was rejected. Lastly, GAI ethical awareness (β = 0.238, t = 3.328, p < 0.001) and perceived GAI benefits (β = 0.663, t = 10.192, p < 0.001) had a significant and positive impact on architecture students’ behavioral intention toward GAI. However, knowledge toward GAI (β = 0.147, t = 1.760, p = 0.078) and perceived GAI challenges (β = −0.023, t = −0.495, p = 0.621) did not have any significant impact on architecture students’ behavioral intention toward GAI. Hence, hypotheses H10 and H11 were accepted, while hypotheses H9 and H12 were rejected. Overall, the model explained that there were 65.2% variances in behavioral intention toward GAI, 50.2% of variances in general skills proficiency, and 33.5% of variances in architecture and design proficiency.

Figure 6.

Path analysis. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01.

Table 10.

Path analysis.

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Study Findings

The purpose of this study is to explore the role of GAI in architecture education from architecture students’ perspectives by investigating knowledge toward GAI, perceived GAI benefits, perceived GAI challenges, and GAI ethical awareness that would influence the development of their skills and behavioral intention to use GAI. A descriptive, cross-sectional research approach was adapted for this purpose. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into how awareness and perception of GAI tools influence the adoption of such tools as well as the development of general skills proficiency and architecture and design expertise.

Regarding RQ1, the study findings revealed a low to moderate level of awareness and knowledge of GAI among architecture students. Only one-third (33%) of the student respondents agreed to known definitions of AI and can assess the limitations and opportunities of GAI usage, while 12% of the respondents strongly agreed with awareness and knowledge. However, around 60% of the respondents agreed to the possibility of future use of GAI. Moreover, around half (50%) of the respondents were aware of the ethical consequences of GAI for society and student performance itself. Similarly, a greater proportion of respondents reported benefits in comparison to challenges. The findings of this study were inconsistent with Alshahrani & Mostafa [7], who reported a high level of awareness among architecture students in Saudi Arabia (around 60%). Past literature revealed that the differences in awareness and self-efficacy of architecture students in developed countries (around 99.6%) are higher than that of architecture students in low-developed countries (71%) [27,29]. Low awareness might have occurred due to the evolving nature of AI or a specific field of architecture education. This implies that although architecture students have low awareness, they have a positive perception toward GAI usage and capability in developing the general and academic-related competencies of architecture students.

Regarding RQ2, the study findings revealed that knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, and perceived GAI benefits had a significant and positive impact on general skills proficiency. These findings supported the notions presented by Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy [75], growth mindset theory [76,77], and expectancy–value theory [84]. Following Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy [75], and growth mindset theory [76,77], the study suggests that a mindset to promote innovation and create learning opportunity through GAI enhance architecture students’ self-efficacy, and that self-efficacy and self-awareness together develop the general skills proficiency of architecture students. These findings were also consistent with the studies of Almogren [52] and Khlaif et al. [50], which highlighted the positive impact of GAI integration in education in developing skills and enhancing academic performance. Following the expectancy–value theory [84], the findings imply that when students perceive that GAI combined with human competencies generate value, they become motivated and learn new skills necessary to complete a task. These findings were also consistent with the studies of Lingard [82], Chellakkannu [83], and Zahra [23], which highlighted how creativity, efficiency, and emotional intelligence are created through the integration of generative AI in education in general.

In parallel, the study findings revealed that knowledge toward GAI, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges had a significant and positive impact on architecture and design expertise. These findings supported the notions presented by Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy [75], and expectancy–value theory [84]. Following Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy [75], the study implied that having knowledge about the innovative nature of GAI and its potential as an e-learning tool can enhance architecture and design expertise. As Feng et al. [78] mentioned, high AI literacy makes it easier to integrate AI in learning practices and thus results in the reinforcement of an innovation mindset complementing architecture and design expertise. Similarly, the positive relationship of perceived GAI benefits and challenges with architecture and design expertise justified the notion presented in the expectancy–value theory [84] and the past literature [6,63,79,83,87]. The perceived GAI benefits encourage architecture students to learn from GAI, overseeing AI-generated content for accuracy, transparency, and falsified information, which consequently drive personal professional growth.

Regarding RQ3, the study findings revealed that GAI ethical awareness and perceived GAI benefits had a significant and positive impact on behavioral intention toward GAI. These findings were supported by Schwartz’s norm activation model [118], TPB [93], and innovation diffusion theory [97] as well as the past literature [97,98,99]. Following Schwartz’s norm activation model [94,118], knowledge of ethical concerns surrounding GAI creates a sense of responsibility for those consequences and hence activates personal norms, leading to enhanced behavioral intention to use GAI with integrity and autonomy. Similarly, following TPB [93] and innovation diffusion theory [97], perceived GAI benefits in the form of perceived usefulness and relative benefits can enhance architecture students’ behavioral intention to use GAI. GAI brings innovation in learning processes that provide ease to use and enhance the ability to learn more efficiently, thus improving the behavioral intention to use GAI.

Overall, GAI, through proper knowledge, awareness of ethical concerns, and beliefs in its relative advantages and perceived usefulness, can enhance general skills proficiency, architecture and design expertise, and behavioral intention to use GAI among architecture students. It is essential for architecture students to understand how GAI operates within the ethical boundaries, with the aims of ease of use and value for the learning process. Such learning practices induce students to use GAI more often and develop their general and specialized skills more efficiently. Focusing on the ethical awareness and evaluation of perceived challenges provides a better understanding of how students should consider the ethical aspects of GAI adoption while implementing it within architecture education. Learning new architecture and design skills and expertise will help the architecture students in designing and building sustainable construction and buildings, resulting in its alignment with Saudi Vision 2030 as well as national and international sustainability goals.

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, the study connected learning theories to technology adoption for embracing the ultimate goal and true purpose of education, particularly architecture education. Secondly, the study findings signified that to integrate GAI technologies in architecture education, students must have both sufficient technical and ethical knowledge and a positive perception of benefits and challenges toward GAI technologies, which resultantly enhanced behavioral intention and developed general skills and architecture and design expertise among architecture students. It implies that architecture students must be trained properly or taught approaches to integrate GAI in their learning approaches in order to achieve the true potential of GAI in skills development. Thirdly, with the revolutionization of almost all industries through GAI, the current study identifies areas for improvement in order to enhance sustainability and educational quality in Saudi Arabia. A low level of awareness and perception regarding GAI demands for more studies to determine the potential causes, given its considerable significance in architecture education. Lastly, the study findings add to the literature on sustainability by emphasizing skills development necessary for the efficient and effective implementation of architecture and construction projects with the assistance of GAI technologies.

The study has several practical implications. Firstly, students should learn new ways to learn from GAI and develop general skills and architecture and design expertise of architecture students. GAI users also train these technologies for assistance and guidance by investing time and effort, which increasingly reduces the learning burden of the course. GAI is an emerging learning tool that can optimize programming, idea generation, and outcome expression [119]. Students should understand and then adapt their learning style to incorporate GAI within their learning practices. Secondly, educators and curriculum designers should design new curriculum and learning materials that explain the usage and procedures of operating GAI. Such educational practices can assist students in using GAI in a more efficient, effective, and accurate manner. Thirdly, administrators should provide students and educators with technological resources that would support the successful integration of GAI in architecture education. Lastly, policy makers and governments should provide educational institutions with the necessary funding to purchase the necessary equipment and hire the necessary trainers in order to successfully implement GAI within the architecture educational settings.

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The study has several key limitations: firstly, the study collected data from only three universities located in two different countries. Future studies can collect data from multiple universities across different regions to confirm the replication and generalizability of the study findings. Secondly, the study focused on only students’ perspectives on the role of GAI in architecture education. Future studies can explore the role of GAI on architecture education from the perspectives of other stakeholders, including educators, university administrators, curriculum administrators, and AI developers. Assessing their perspectives would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities they face when implementing GAI in architecture education. Thirdly, the study identified that most of the students sampled in this study did not frequently use GAI technologies or were not expert in using digital tools. With having a low level of awareness, assessing the corresponding impact on skills development and behavioral intention toward GAI would be misleading or inaccurate. Future studies could adopt an experimental design, whereby students can be trained to use GAI technologies and, later, be assessed for their awareness and resulting impact on skills development and behavioral intention toward GAI. Fourthly, the study adopted a cross-sectional design that weakened the reliability and generalizability of research findings by limiting it to the current situation of architecture education. Future studies would adopt longitudinal research to assess the role of GAI in architecture education or investigate the causal relationships between the identified variables over time, i.e., across different eras of development in architecture education. Fifthly, the study did not consider any demographic characteristics, personality attributes, or cultural differences as potential mediators or moderators. Future studies can explore the mediating or moderating role of such variables in the underlying relationships explaining the role of GAI in architecture education. Sixthly, the current study reported a low to moderate level of awareness, both technically and ethically, that restrains students’ ability to perceive benefits and challenges in the usage of GAI technologies. Future studies can assess the confounding role of experience and frequency of usage in transforming knowledge into competencies and intention to use GAI. Seventhly, the study has developed their own instruments to assess students’ knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges due to the lack of available established measures particularly for the field of architecture and design. Although the self-developed scale was thoroughly validated with exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, the current study did not assess test–retest reliability on the self-developed scale. Future research can employ cross-validation techniques involving different methodologies or can compare with other measures to confirm the reliability and validity of these self-developed measures. Lastly, the current study singly focused on utilizing a single, self-developed scale to measure the study variables within a quantitative research design. Further studies can employ qualitative research design or mixed-methods research design to understand the nature and extent of the challenges GAI technologies pose to students’ use of GAI.

7. Conclusions

The study explored the role of GAI in architecture education from students’ perspectives. The study found a low usage of GAI technologies and low proportion of expert proficiency in using digital tools. Only 40% of the sampled students at most have reported a sufficient level of knowledge toward GAI, considered the ethical concerns of GAI, and perceived to have identified the benefits of GAI. However, less than one-third of the respondents agreed to have perceived challenges of GAI. With respect to skills development, the study found that knowledge toward GAI, GAI ethical awareness, and perceived GAI benefits significantly influence general skills proficiency, while knowledge toward GAI, perceived GAI benefits, and perceived GAI challenges significantly influence architectural and design expertise. Lastly, GAI ethical awareness and perceived GAI benefits significantly influence architecture students’ behavioral intention toward GAI. The current study included ethical awareness and evaluation of perceived challenges in the theoretical framework, which provide a more nuanced understanding of GAl adoption that goes beyond simple technological acceptance. The study provides several implications for students, educators, curriculum designers, university administrators, and other stakeholders to look into particular factors that would enhance architecture students’ skills development and behavioral intention to use GAI. Such an approach promotes educational quality and sustainability in the line of SDG 4 and Saudi Vision 2030.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L., A.A., E.A. and M.A.; methodology, W.L. and A.A.; software, W.L.; validation, W.L.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, W.L., A.A., E.A., M.A. and H.M.; resources, W.L., A.A., E.A., M.A. and H.M.; data curation, W.L., A.A., E.A., M.A. and H.M. writing—original draft preparation, W.L., A.A., E.A. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization: W.L.; supervision, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Prince Sultan University (Approval code: PSU IRB-2025-05-0230).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| GAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| AECO | Architecture, Engineering, Construction, and Operations |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling |

| χ2/df | chi-square statistic/degree of freedom |

| CFI | Comparative Fix Index |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

Appendix A. Survey Title: The Role of Generative AI in Architecture Education

Introduction: This survey aims to explore how architecture students perceive and utilize generative AI tools in their education. The data collected will help in understanding how these technologies influence learning experiences, creativity, and overall education outcomes.

Demographic Information

- What is your year of study?

- 1st Year

- 2nd Year

- 3rd Year

- 4th Year

- Post-Graduate

- Have you ever used generative AI technologies (e.g., ChatGPT, Large Language Models, Foundation models)?

- Never

- Rarely

- Sometimes

- Often

- Always

- What is your level of proficiency in using digital tools (e.g., AutoCAD, Rhino, Revit)?

- Beginner

- Intermediate

- Advanced

- Expert

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Willingness to use Generative AI | |||||

| I envision integrating generative AI into my teaching and learning practices in the future. | |||||

| Students must learn how to use generative AI well for their careers. | |||||

| I believe generative AI can improve my digital competence. | |||||

| I believe generative AI can help me save time. | |||||

| I believe generative AI can provide me with unique insights and perspectives that I may not have thought of myself. | |||||

| I think generative AI can provide me with personalized and immediate feedback and suggestions for my assignments. | |||||

| I think generative AI is a great tool as it is available 24/7. | |||||

| I think generative AI is a great tool for student support services due to anonymity. | |||||

| Knowledge toward Generative AI | |||||

| I know the most important concepts of the topic “artificial intelligence”. | |||||

| I know definitions of artificial intelligence. | |||||

| I can assess what the limitations and opportunities of using an AI are. | |||||

| I can assess what advantages and disadvantages the use of an artificial intelligence entails. | |||||

| I can think of new uses for AI. | |||||

| I can imagine possible future uses of AI. | |||||

| Generative AI Ethics | |||||

| I can weigh the consequences of using AI for society. | |||||

| I can incorporate ethical considerations when deciding whether to use data provided by an AI. | |||||

| I can analyze AI-based applications for their ethical implications. | |||||

| General Skills Proficiency | |||||

| I have good collaboration and interactive skills. | |||||

| I am a confident user of information and communication technology. | |||||

| I work well in a team. | |||||

| I always share knowledge and experiences with other team members. | |||||

| I can assess situations, identify problems, determine root cause and evaluate. | |||||

| I am fully capable of utilizing research knowledge at work. | |||||

| I can comprehend and comply with work rules and regulations and the firm dynamics. | |||||

| I can select goal-relevant activities, | |||||

| I can manage time to handle multiple tasks and projects at once. | |||||

| I can set up and manage the budget of the projects. | |||||

| I can accept and apply criticism to improve my work with a positive attitude. | |||||

| I can adapt to changing circumstances and environments. | |||||

| I can take on board new ideas and concepts. | |||||

| I can communicate and work with people from different cultural backgrounds and countries. | |||||

| I have strong leadership skills. | |||||

| I am fully capable of exhibiting competence, respect, and appropriate behavior. | |||||

| Architectural and Design Expertise | |||||

| My knowledge in architectural and design field is updated and optimal. | |||||

| I am fully capable of developing or reviewing programming phase and design phase standards in compliance with codes and client’s requirements. | |||||

| I am fully capable of assessing environmental, social, economic conditions of the site/building. | |||||

| I have full control and updated architectural and design software skills. | |||||

| I can effectively establish preliminary project scope, budget, and scheduling. | |||||

| I can effectively coordinate architectural, structural, mechanical, civil, and electrical drawings. | |||||

| I am fully capable of performing life cycle cost analysis of selected building elements. | |||||

| I can conduct thorough on-site observation. | |||||

| I am fully aware of potential sustainable solutions and application. | |||||

| Generative AI-related Benefits | |||||

| Generative AI tools stimulate my creative thinking in educational tasks. | |||||

| Generative AI applications increase my engagement in academic activities. | |||||

| Generative AI provides personalized feedback that enhances my learning. | |||||

| Generative AI tools offer emotional support that helps me in my studies. | |||||

| Generative AI applications enhance my ability to work collaboratively on creative projects. | |||||

| Generative AI applications make a variety of learning resources more accessible to me. | |||||

| Generative AI-integrated educational applications positively influence my academic emotions. | |||||

| Generative AI-related Challenges | |||||

| Generative AI tools limit my creative thinking in educational applications. | |||||

| I feel emotionally disengaged when using generative AI in educational applications. | |||||

| I experience anxiety about relying on generative AI for academic performance. | |||||

| Technical issues with generative AI tools often hinder my learning process. | |||||

| I rely too much on generative AI for completing my educational tasks. | |||||

| The lack of access to generative AI limits my educational opportunities. | |||||

| I have ethical concerns about using generative AI in my educational activities. | |||||

| I am concerned about the accuracy of the answers given by generative AI. | |||||

| Generative AI applications can pose risks to the protection of personal data. | |||||

References

- Ronge, R.; Maier, M.; Rathgeber, B. Towards a Definition of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Philos. Technol. 2025, 38, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, U.; Sai, S.; Chamola, V.; Sangwan, D. A Comprehensive Review on Generative AI for Education. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 142733–142759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Chan, E.K.C.; Lo, C.K. Opportunities, Challenges and School Strategies for Integrating Generative AI in Education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ren, Y.; Nyagoga, L.M.; Stonier, F.; Wu, Z.; Yu, L. Future of Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence: Consensus among Chinese Scholars on Applications of ChatGPT in Schools. Future Educ. Res. 2023, 1, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kang, S. The Influence of Generative AI with Prompt Engineering on Creative Design in Architectural Education. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onatayo, D.; Onososen, A.; Oyediran, A.O.; Oyediran, H.; Arowoiya, V.; Onatayo, E. Generative AI Applications in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction: Trends, Implications for Practice, Education & Imperatives for Upskilling—A Review. Architecture 2024, 4, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, K.K.D.S.; De Souza, R.A.C. Digital Transformation towards Education 4.0. Inform. Educ. 2021, 21, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, N. Role of ChatGPT and Similar Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Construction Industry. SSRN J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenlaender, J. A Taxonomy of Prompt Modifiers for Text-to-Image Generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.13988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, P.; Mazurek, G.; Krzypkowska, P.; Kurasinski, A. Artificial Intelligence Prompt Engineering as a New Digital Competence: Analysis of Generative AI Technologies Such as ChatGPT. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2023, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Olbina, S.; Issa, R.R. BIM Use by Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) Industry in Educational Facility Projects. Adv. Civil Eng. 2019, 2019, 1392684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ventura, J.; de-Miguel-Arbonés, E.; Sentieri-Omarrementería, C.; Galan, J.; Calero-Llinares, M. A Tool to Assess Architectural Education from the Sustainable Development Perspective and the Students’ Viewpoint. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Yang, F.; Mei, H.; Li, H. Artificial Intelligence-Designer for High-Rise Building Sketches with User Preferences. Eng. Struct. 2023, 275, 115171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okagbue, E.F.; Ezeachikulo, U.P.; Akintunde, T.Y.; Tsakuwa, M.B.; Ilokanulo, S.N.; Obiasoanya, K.M.; Ilodibe, C.E.; Ouattara, C.A.T. A Comprehensive Overview of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Education Pedagogy: 21 Years (2000–2021) of Research Indexed in the Scopus Database. Social Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.; Mostafa, A.M. Enhancing the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Education—Case Study Saudi Arabia. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1610709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocho-Bermejo, A. Artificial Intelligence and Architectural Design before Generative AI: Artificial Intelligence Algorithmics Approaches 2000–2022 in Review. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Lotfabadi, P. Critical Questions on the Emergence of Text-to-Image Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Design Pedagogy. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 3557–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizawa, T. Architectural Informatics Self-Hackathon Workshop—Reassessing Professional Essence through Generic and Generative Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2025, 14780771251335108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, M.B.; Miri, M.; Tracy, T. Students’ Perceptions of Generative AI Image Tools in Design Education: Insights from Architectural Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Shehata, W.; Rowlinson, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Architecture, Engineering, Construction, and Operations: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullinja, E.; Jashanica, K. Examining the Knowledge Level and Opinions of Architecture Students about Artificial Intelligence. Social Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12, 101720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.-L.; Ho, C.-C. Generative AI in Education: Mapping the Research Landscape through Bibliometric Analysis. Information 2025, 16, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.; Samra, M.; El Gizawi, L. Working toward Advanced Architectural Education: Developing an AI-Based Model to Improve Emotional Intelligence in Education. Buildings 2025, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloshan, M. Sustainable Environmental Design: Evaluating the Integration of Sustainable Knowledge in Saudi Arabian Architectural Programs. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, I. Strategic Environmental Assessment for Sustainable Coastal Zone Management in Saudi Arabia, Aligning with Vision 2030. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2024, 15, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, R.E.C.; Brito, J.; Buckman, M.; Drake, E.; Ilatova, E.; Rice, P.; Sabbagh, C.; Voronkin, S.; Abraham, Y.S. Waste Management and Operational Energy for Sustainable Buildings: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.A.; McCluskey, A.; Alfaris, A.; Strzepek, K. Scenario Based Regional Water Supply and Demand Model: Saudi Arabia as a Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2016, 7, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]