Future Thinking and Sustainable Career Perceptions in Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

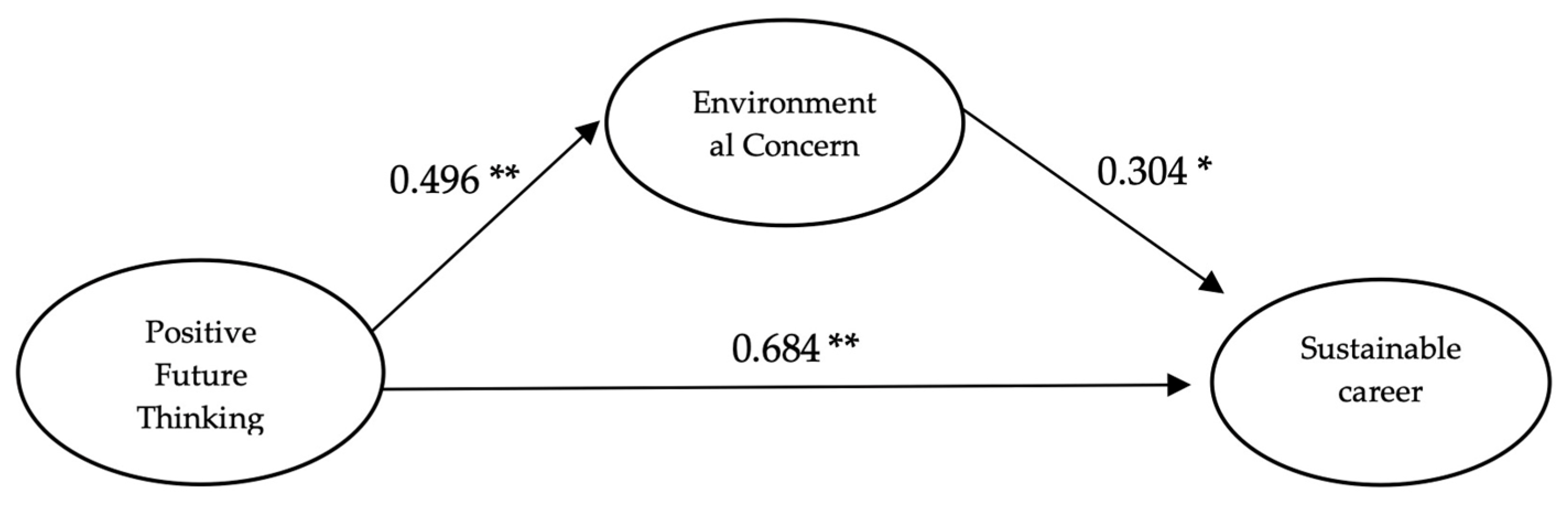

- Is positive future thinking associated with higher levels of environmental concern?

- -

- Does positive future thinking predict perceptions of sustainable careers?

- -

- Does environmental concern mediate the relationship between positive future thinking and perceptions of sustainable careers?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emerging Adulthood, Future Thinking, and Environmental Concern

2.2. Positive Future Thinking and Sustainable Career Perceptions

2.3. The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern

2.4. Career Development and Sustainable Development Goals

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Fabio, A.; Palazzeschi, L.; Bonfiglio, A.; Gori, A.; Svicher, A. Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being for sustainable development in university students: Personality traits or acceptance of change? Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1180995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Svicher, A. The Eco-Generativity Scale (EGS): A New Resource to Protect the Environment and Promote Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svicher, A.; Gori, A.; Di Fabio, A. The Sustainable Development Goals Psychological Inventory: A Network Analysis in Italian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Pallini, S.; Vecchio, G.M.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Future orientation and attitudes mediate career adaptability and decidedness. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95–96, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, M.F.; Mastuti, E.; Yoenanto, N.H. The impact of future orientation and social support on career adaptability. J. Psikol. Ulayat 2024, 12, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.S.A.; Wyatt, S.L. Examining Influences on Environmental Concern and Career Choice among a Cohort of Environmental Scientists. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2008, 7, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J.; Zukauskiene, R.; Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.; Crapnell, T.; Lau, L.; Bennett, A.; Lotstein, D.; Ferris, M.; Kuo, A. Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Faustman, E.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Commodari, E.; Consiglio, A.; Cannata, M.; La Rosa, V.L. Influence of parental mediation and social skills on adolescents’ use of online video games for escapism: A cross-sectional study. J. Res. Adolesc. 2024, 34, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Ching, B.H.H.; Commodari, E. The Impact of Helicopter Parenting on Emerging Adults in Higher Education: A Scoping Review of Psychological Adjustment in University Students. J. Genet. Psychol. 2024, 186, 162–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: Developmental Period Facilitative of the Addictions. Eval. Health Prof. 2014, 37, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, S.; Barr, T.; Livneh, Y.; Nurmi, J.-E.; Vasalampi, K.; Pratt, M. Career pursuit pathways among emerging adult men and women. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 39, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Chaoyun, L. How young adults imagine their future? The role of temperamental traits. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2017, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.G.G. Future time perspective as a predictor of adolescents’ adaptive behavior in school. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015, 36, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seginer, R. Future Orientation: A Conceptual Framework. In Future Orientation: Developmental and Ecological Perspectives; Seginer, R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, S.; Nurmi, J.-E. Dynamics of goal pursuit and personality make-up among emerging adults: Typology, change over time, and adaptation. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2010, 2010, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacter, D.L.; Addis, D.R.; Buckner, R.L. Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G.; da Silva, J.T.; Paixão, M.P.; Crespo, C.; Relvas, A.P. Future Hopes and Fears of Portuguese Emerging Adults in Macroeconomic Hard Times: The Role of Economic Strain and Family Functioning. Emerg. Adulthood 2019, 8, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Alisat, S.; Soucie, K.; Pratt, M. Generative Concern and Environmentalism. Emerg. Adulthood 2015, 3, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle Matsuba, M.; Alisat, S.; Pratt, M.W. Environmental Activism in Emerging Adulthood. In Flourishing in Emerging Adulthood: Positive Development During the Third Decade of Life; Padilla-Walker, L.M., Nelson, L.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. The Structure of Environmental Concern: Concern for Self, Other People, and the Biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammitti, A.; Santisi, G.; Magnano, P.; Di Nuovo, S. Analyzing Attitudes to Promote Sustainability: The Adaptation of the Environmental Concern Scale (ECs) to the Italian Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J.; Cameron, L.D. A Cross-Cultural Study of Environmental Motive Concerns and Their Implications for Proenvironmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Larsen, S. Intentions to make sustainable tourism choices: Do value orientations, time perspective, and efficacy beliefs explain individual differences? Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalot, F.; Ahvenharju, S.; Uusitalo, O. Green dreams are made of this: Futures consciousness and proenvironmental engagement. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 64, e12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpawong, T.E.; Rohrbach, L.A.; Milam, J.E.; Unger, J.B.; Land, H.; Sun, P.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Sussman, S. Stressful Life Events and Predictors of Post-traumatic Growth among High-Risk Early Emerging Adults. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Valls-Figuera, R.G.; Zammitti, A.; Magnano, P. Redefining ‘Careers’ and ‘Sustainable Careers’: A Qualitative Study with University Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fang, T.; Liu, F.; Pang, L.; Wen, Y.; Chen, S.; Gu, X. Career Adaptability Research: A Literature Review with Scientific Knowledge Mapping in Web of Science. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers; EE/Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hallpike, H.; Vallee-Tourangeau, G.; Van der Heijden, B. A Distributed Interactive Decision-Making Framework for Sustainable Career Development. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 790533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Jin, S. Development and validation of career sustainability scale for mid-career employees. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1442119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lian, R. Linking undergraduates’ future orientation and their employability confidence: The role of vocational identity clarity and internship effectiveness. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, H.; Teng, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Gu, X. Future Work Self Salience and Future Time Perspective as Serial Mediators Between Proactive Personality and Career Adaptability. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 824198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Romanelli, M.; Velez-Grau, C.; Lindsey, M.A. Unpacking Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Associations between Neighborhood Disadvantage and Academic Achievement: Mediation of Future Orientation and Moderation of Parental Support. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkapaa, K.; Jarvikoski, A.; Gould, R. Motivational orientation of people participating in vocational rehabilitation. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2014, 24, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, S.P.; Innes, J.M. The Attitudinal Influence of Career Orientation in 1st-Year University Students: Environmental Attitudes as a Function of Degree Choice. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 32, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnocky, S.; Milfont, T.L.; Nicol, J.R. Time Perspective and Sustainable Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2013, 46, 556–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.L.; Jackson, J.J.; Roberts, B.W.; Lapsley, D.K.; Brandenberger, J.W. Change You Can Believe In: Changes in Goal Setting During Emerging and Young Adulthood Predict Later Adult Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 2, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- International Association for Educational and Vocational Guidance Challenges and Opportunities for Career Guidance Towards Sustainability in the Aftermath of COVID-19 and Digital Transformation. Available online: https://iaevg.com/resources/Documents/Final%20Draft_2022%20Communique.cleaned.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- International Association for Educational and Vocational Guidance Contribution of Educational and Vocational Guidance to Support Sustainable Development and the Necessary Socio-Ecological Transition. Available online: https://iaevg.com/resources/IAEVG%202023%20Communique.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Plant, P. Fringe Focus: Informal Economy and Green Career Development. J. Employ. Couns. 2011, 36, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, S.; Scott, W. Higher Education and Sustainable Development: Paradox and Possibility; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adomßent, M.; Fischer, D.; Godemann, J.; Herzig, C.; Otte, I.; Rieckmann, M.; Timm, J. Emerging areas in research on higher education for sustainable development—Management education, sustainable consumption and perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Sustainability in higher education in the context of the UN DESD: A review of learning and institutionalization processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istenic Starcic, A.; Terlevic, M.; Lin, L.; Lebenicnik, M. Designing Learning for Sustainable Development: Digital Practices as Boundary Crossers and Predictors of Sustainable Lifestyles. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehmaa, A.; Karvinen, M.; Keskinen, M. Building a More Sustainable Society? A Case Study on the Role of Sustainable Development in the Education and Early Career of Water and Environmental Engineers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models, Version 4.0. Available online: http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Russo, A.; Zammitti, A.; Parola, A.; Marcionetti, J. Assessing sustainable career development: The Future-Sustainable Career Scale (F-SCS) for young adults. Educ. Train. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Zammitti, A.; Zarbo, R.; Magnano, P.; Santisi, G. The sustainable career scale (SCS): Development, validity, reliability and invariance. J. Glob. Responsib. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Gibson, K.; Schoemann, A.M. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H. Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, R.S.; Cheung, G.W. Estimating and Comparing Specific Mediation Effects in Complex Latent Variable Models. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 15, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcionetti, J.; Zammitti, A. Italian Higher Education Student Engagement Scale (I-HESES): Initial validation and psychometric evidences. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2023, 37, 470–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Tena, R.; Mayor Ruiz, C.; Yot Domínguez, C.; Chaves Maza, M. Structural Equation Models on the Satisfaction and Motivation for Retirement of Spanish University Professors. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Santoro, G.; Schimmenti, A. Interpersonal Guilt and Problematic Online Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Emotion Dysregulation. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2022, 19, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. 2016, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.; Jin, Q. Impact of a Career Exploration Course on Career Decision Making, Adaptability, and Relational Support in Hong Kong. J. Career Assess. 2015, 24, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Hung, K.; Wang, L.; Schuett, M.A.; Hu, L. Do perceptions of time affect outbound-travel motivations and intention? An investigation among Chinese seniors. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayseless, O.; Keren, E. Finding a Meaningful Life as a Developmental Task in Emerging Adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 2013, 2, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammitti, A.; Russo, A.; Baeli, V.; Hichy, Z. “Guiding University Students towards Sustainability”: A Training to Enhance Sustainable Careers, Foster a Sense of Community, and Promote Sustainable Behaviors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, W.E.; Mouratidou, M. Preparing for a Sustainable Career. GILE J. Skills Dev. 2022, 2, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A. Sustainable Communities and Sustainable Development: A Review of the Sustainable Communities Plan; Sustainable Development Commission: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Future Thinking | 2.99 | 0.72 | - | ||

| 2. Environmental Concern | 5.70 | 0.98 | 0.30 * | - | |

| 3. Sustainable Career | 3.66 | 0.66 | 0.68 * | 0.42 * | - |

| Model | Model Fit | Model Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | RMSEA (90% C.I.) | CFI | SRMS | ΔRMSEA | ΔCFI | |

| Configural invariance | 2.517/34 * | 0.077 (0.057–0.097) | 0.947 | 0.061 | - | - |

| Metric invariance | 2.342/39 * | 0.072 (0.053–0.092) | 0.946 | 0.065 | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| Scalar invariance | 2.280/42 * | 0.071 (0.052–0.089) | 0.945 | 0.077 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

La Rosa, V.L.; Zammitti, A. Future Thinking and Sustainable Career Perceptions in Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115146

La Rosa VL, Zammitti A. Future Thinking and Sustainable Career Perceptions in Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115146

Chicago/Turabian StyleLa Rosa, Valentina Lucia, and Andrea Zammitti. 2025. "Future Thinking and Sustainable Career Perceptions in Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115146

APA StyleLa Rosa, V. L., & Zammitti, A. (2025). Future Thinking and Sustainable Career Perceptions in Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Environmental Concern. Sustainability, 17(11), 5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115146