Port’s Role as a Determinant of Cruise Destination Socio-Economic Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Development of Cruise Tourism

2.2. Coastal Destination Cost/Benefit Trade-Off

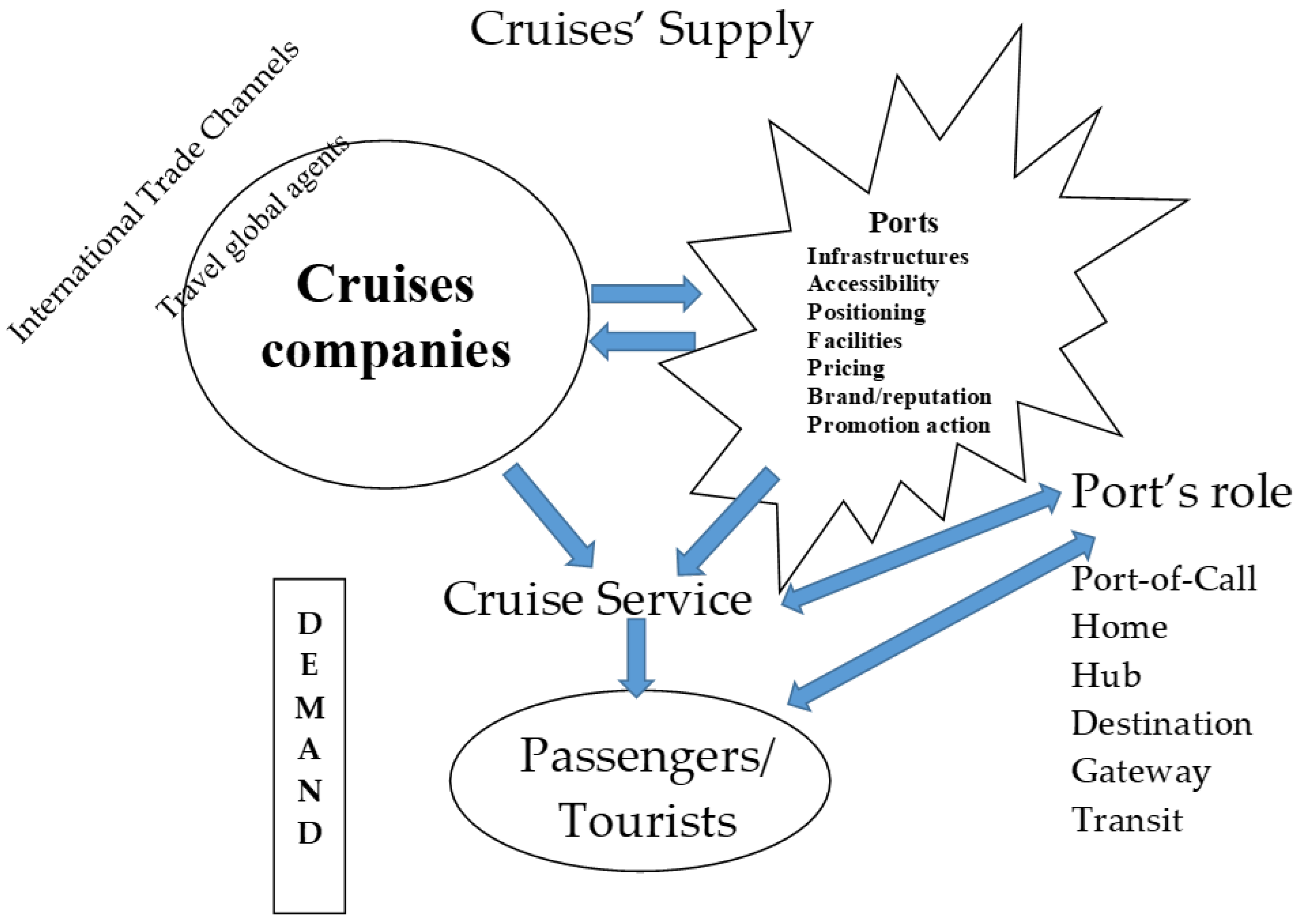

2.3. The Cruise Sector Structure and Drivers

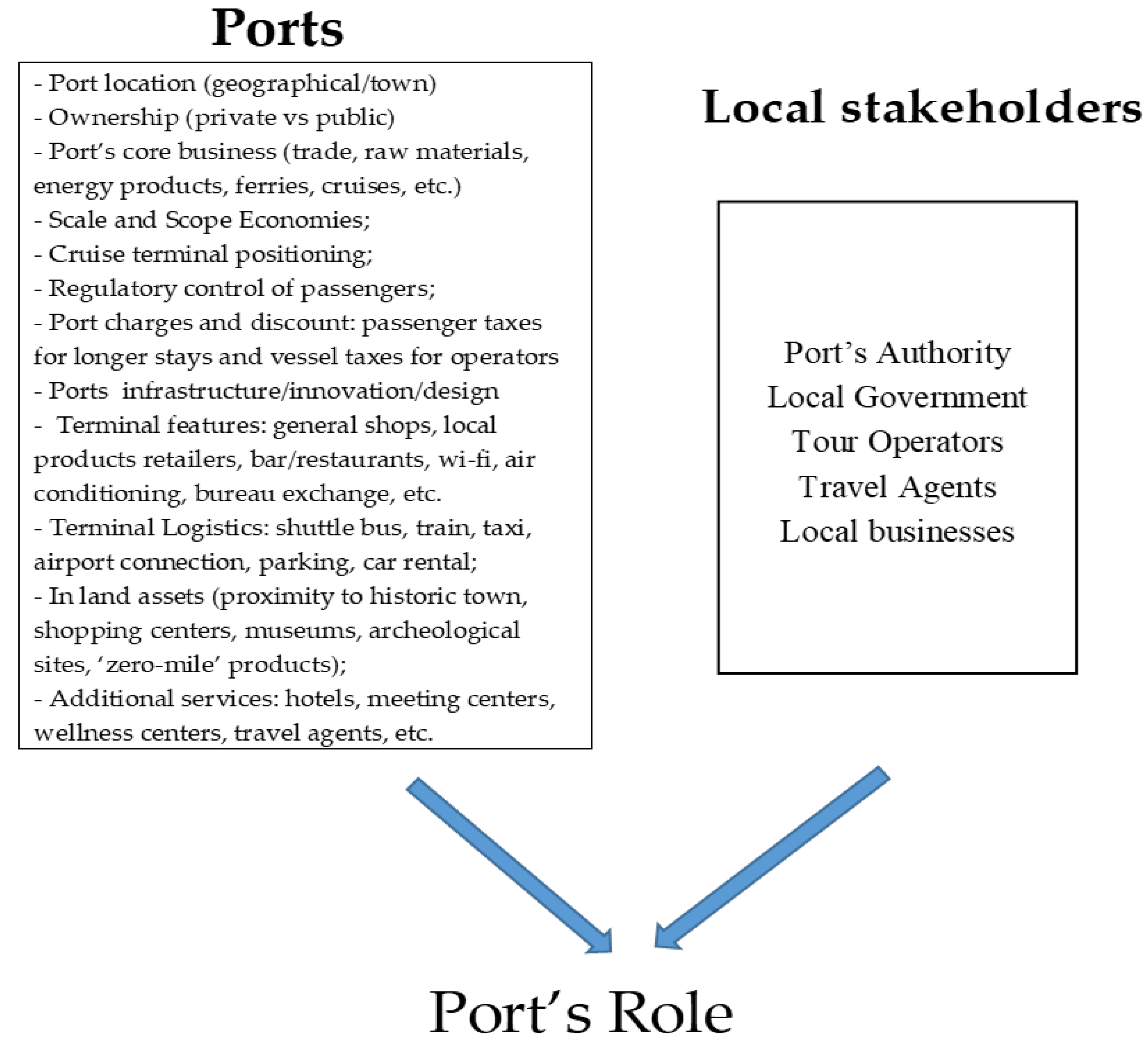

2.4. Port Categories and Their Role in the Cruise Destination Developmement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Proposed Framework

3.2. Research Methodology: A Qualitative Case Study Analysis

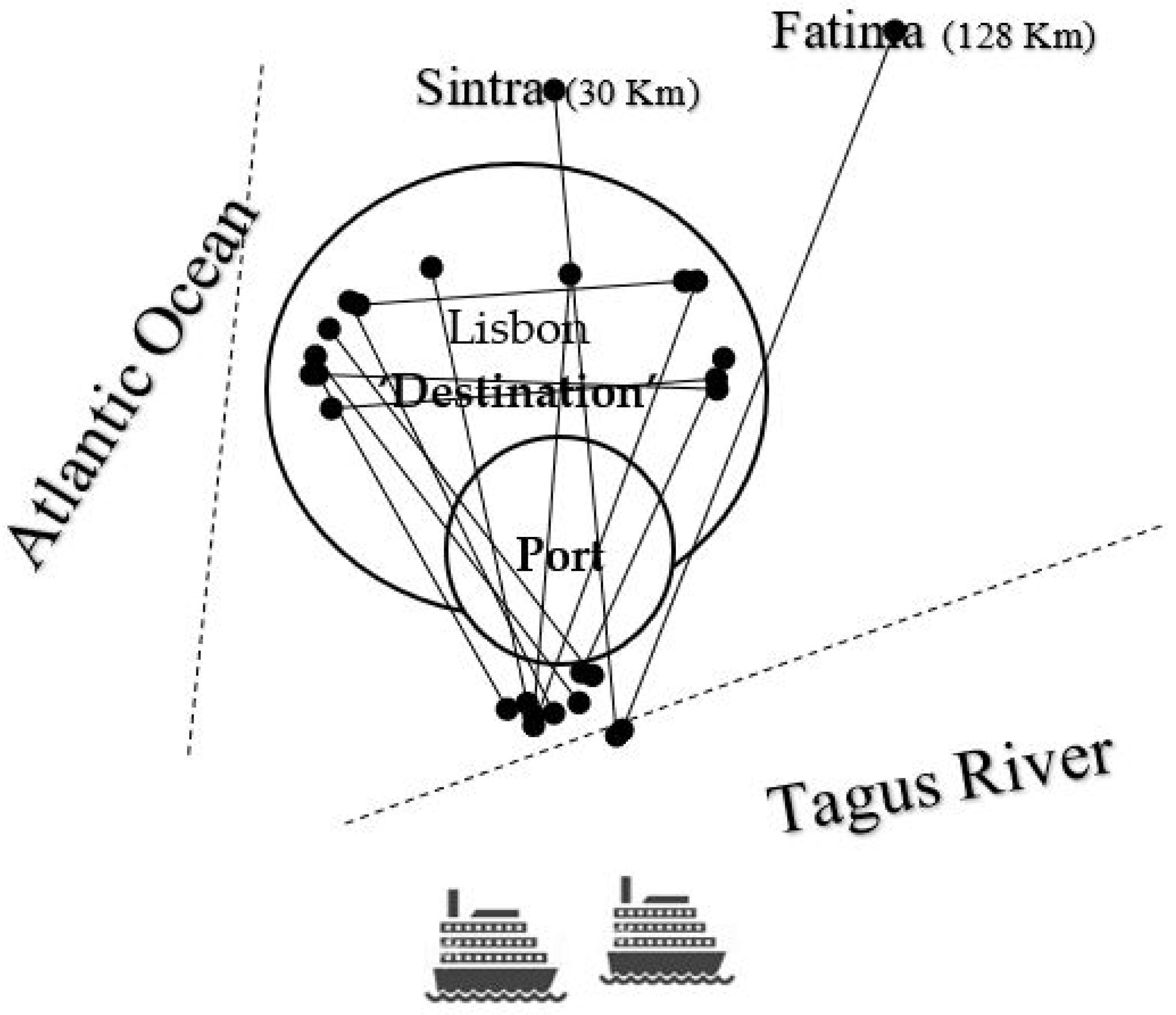

3.2.1. Lisbon: A “Destination” Port

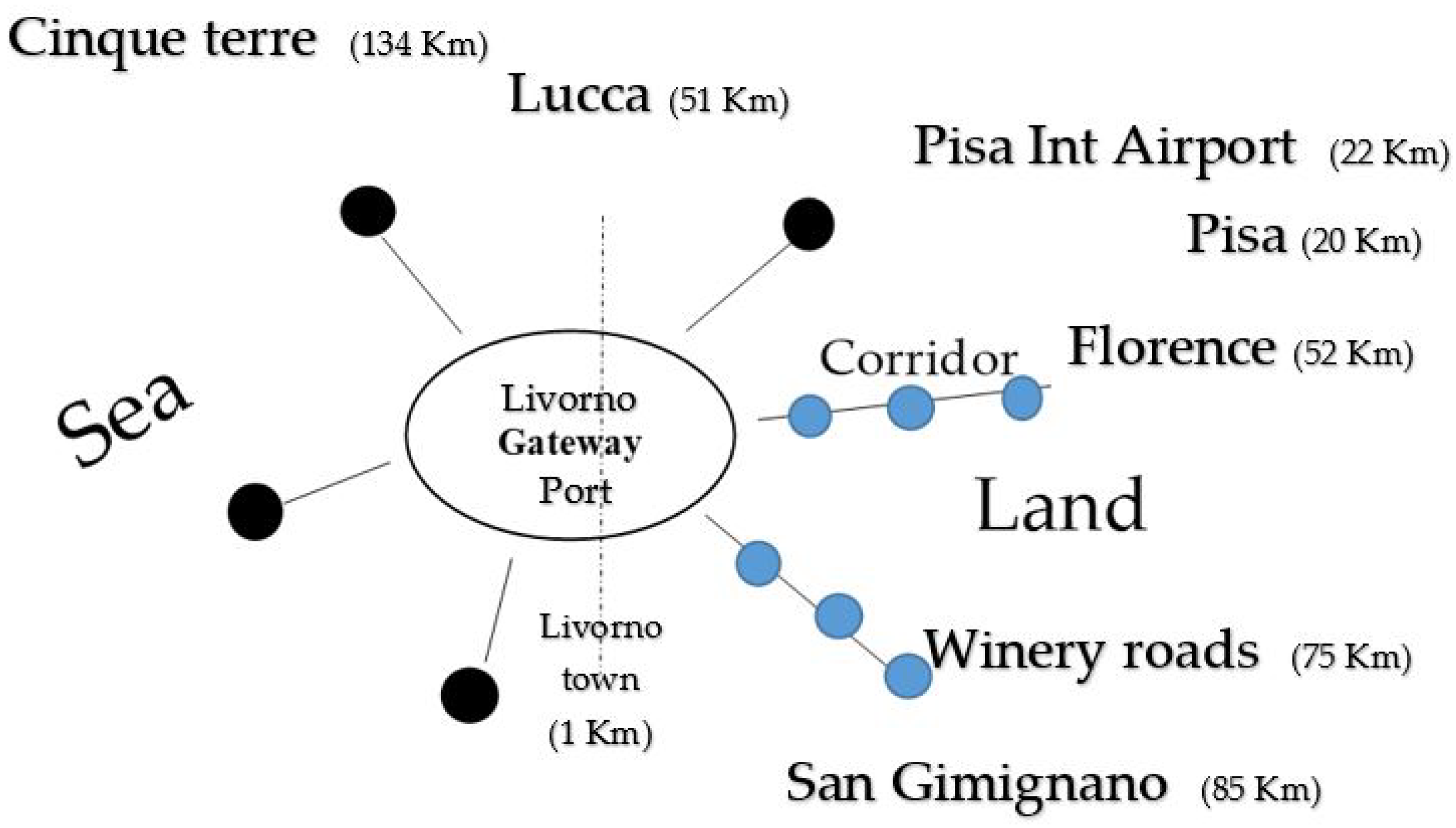

3.2.2. Livorno: A “Gateway” Port

- -

- Livorno was born as a trading port supporting all the inland Tuscan economy;

- -

- Pisa at the beginning and obviously Florence were strategically the main reference points for political and economic decisions;

- -

- Livorno is a strategic location for connecting the Italian peninsula with islands like Sardinia, Corse, Elba, Sicily, and the south Mediterranean (Tunisia, Morocco); many traders and passengers use the quite impressive ferry network departing from Livorno.

4. Results

5. Conclusions Remarks and Discussion

6. Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biehn, N. A cruise ship is not a floating hotel. J. Rev. Pricing Manag. 2006, 5, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakson, R. Beyond the tourist bubble? Cruise ship passengers in port. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Petrick, J. Why do you cruise? Exploring the motivations for taking cruise holidays and the construction of a cruising motivation scale. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritz, N.; Cecil, A. Investigating the sustainability of cruise tourism: A case study of Key West. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoa, C.E.A.; Flores, L.C.S.; Stecker, B. The convergence of environmental sustainability and ocean cruises in two moments: In the academic research and corporate communication. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Tur. 2018, 12, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P. Economic Significance of Cruise tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Responsible cruise tourism and regeneration: The case of Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada. Int. Plan. Stud. 2018, 23, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliano, G.; Benassai, G.; Benassai, E. Integrating urban and port planning policies in a sustainable perspective: The case study of Naples historic harbour area. Plan. Perspect. 2018, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ Perceptions of Stress Related to cruise tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.J.; Dredge, D. Cruise Tourism Shore Excursions: Value for Destinations? Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, T.; Wozniak, D. The economic, social and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Lorenzo-Romero, C.; Gallarza, M. Host community perceptions of cruise tourism in a homeport: A cluster analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragin, A.; Dragin, V.; Kosic, K.; Demirovic, D.; Ivkov-Dzigurski, A. Tourists motives and residents towards the cruisers. Tour. South East Eur. 2017, 4, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Abbate, T. Island cruise tourism development A resident perspective in the context of Italy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Schlesinger, W. The sustainability of cruise tourism onshore: The impact of crowding on visitors’ satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.; Wolf, K. Exploring Assumptions about Cruise Tourists’ visits to ports. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, E.N.; Damian, I.M.; Fernandéz-Morales, A. Carrying capacity model applied in coastal destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, W.R.; Lohmann, G. Power in the context of cruise destination stakeholder’s interrelationships. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidaki, E.; Lekakou, M. Cruise carrying capacity: A conceptual approach. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlis, T.; Polemis, D. Cruise homeport competition in the Mediterranean. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. The cruise shorescape as contested tourism space: Evidence from the warm-water pleasure periphery. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Nijkamp, P. Itinerary Planning: Modelling cruise lines’ lengths of stay in ports. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, F.; Beck, A.L.; Manfredini, D.; Muller, M. Do tourist attractions of an itinerary pull cruise ship lines? A logit model estimation for Southern Hemisphere destinations. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Spatial Planning, Tourism and Regeneration in Historic port cities. DISP Plan. Rev. 2003, 39, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.P.; Romein, A. Cruise passenger terminals, spatial planning and regeneration: The cases of Amesterdam and Rotterdeam. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 2033–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaggelas, G.K.; Pallis, A.A. Passengers ports: Services provision and their benefits. Marit. Policy Manag. 2010, 37, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Hein, C.; Zhang, T. Understanding how Amesterdam City tourism marketing addresses cruise tourists’ motivations regarding culture. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.A. Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and Sustainability. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebot, N.; Rosa-Jimenez, C.; Ninot, R.P.; Perea-Medina, B. Challenges for the future of ports. What can be learnt from the Spanish Mediterranean ports? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 137, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussano, M.I.; Ferrari, C.; Tei, A. Port hierarchy and concentration: Insights from the Mediterranean cruise market. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Wang, S.; Gillet, B.D.; Liu, Z. An overview of cruise tourism research through comparison of cruise studies published in English and Chinese. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 77, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassis, A. Cruise Tourism Management: State of the art. Tours. Rev. 2017, 72, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. ‘Overtourism’? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cruise Lines International Association. The Contribution of the International Cruise Industry to the Global Economy in 2017; CLIA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Tourism Statistics at Regional Level. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Tourism_statistics_at_regional_level (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- Cruise Activities in MedCruise Port Statistics of 2017; Medcruise report; Medcruise: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- IRPET. Cruising in Livorno and Its Economic Impaction in Tuscany; IRPET: Florence, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. Environmental Sustainable Cruise Tourism: A reality Check. Mar. Policy 2002, 26, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Zapata-Aguirre, S. Cruise Tourism: Economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2010, 1, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogkamer, L.P. Assessing and Managing Cruise Ship Tourism in Historic Port Cities: Case Study Charleston South Carolina. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, B.; Cruse, R. Cruise Tourism in Dominica: Benefits and Beneficiaries. ARA J. Tour. Res. 2015, 5, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, L.J.; Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Cruise destinations attributes: Measuring the relative importance of the onboard and the onshore aspects of cruising. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J.P.; Notteboom, T. The geography of cruises: Itineraries, not destinations. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 38, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakou, M.B.; Pallis, A.A. Cruising the Mediterranean sea: Market Structures and EU Policy initiatives. J. Transp. Shipp. 2005, 2, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bagis, O.; Dooms, M. Turkey’s potential on becoming a cruise hub for the East Mediterranean region: The case of Istambul. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dia Vaio, A.; D’Amore, G. Governance of Italian cruise terminals for the management of Mediterranean passenger flows. Int. J. Euro Mediterr. Stud. 2012, 4, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, B. Geography and the cruise ship port selection process. Marit. Policy Manag. 1990, 17, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CTUR. URBACT II European Programme CTUR Thematic Framework–Cruise Traffic and Urban. In Regeneration Final Report and Good Practices Guide; European Union: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Portal do Porto de Lisboa. Available online: http://www.portodelisboa.pt (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- Deloitte. Estudo de Impacte Macroeconómico do Turismo na Cidade e na Região de Lisboa em; Deloitte: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, J.C. Cruzeiros Turisticos e acessos a cidades históricas: A reinvenção de Lisboa como porto de entrada e lugar turístico. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 397–416. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.G. Cruise Tourism in Lisbon-Cruise Tourism activity and its impact in the city. Work project for a Master degree. NOVA–School of Business and Economics; unpublished.

| Variables | Livorno (Italy) | Lisbon (Portugal) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Port | Gateway Port | Destination Port |

| Ownership/management | Until 2018, the proprietary majority was public. Since 2019, 66% is privately hold by Moby (main ferry company) + 34% by the Chamber of Commerce and Port Network Authority of the Tyrrhenian Sea | The Administração do Porto de Lisboa (APL), the administration of the Lisbon Port, is an association that has the grant to the cruise terminal activity for the last 35 years. Since 2014, the APL has a private ownership. |

| Port location | -West-Med Route: Morocco–Livorno -North Tyrrhenian Multi-Port Gateway -Northern Italy -Central–Eastern Europe -West Mediterranean/Eastern Europe “land bridge” -North–South America | Switching point or base port for -Atlantic coast of Europe; -Western Mediterranean; -Northern Europe; -Africa, Madeira, and the Canary Islands |

| Port core business * | Cargo shipment: 748,000 TEU movements (+1.9%) Ro-Ro (cars) sector: 507,000 movements (+13.2%) Energy Products: Long tradition in chemical and gas and oil sector: 11 million tons (+10%) Ferry: 2.65 million passengers (+5.2%) Cruises: 786,000 passengers (+12.5%) | Container cargo: 56% Bulk agri-food stuffs and liquid and solid raw materials: 29% Tourism and leisure: 15% Cruises: 487,000 passengers (+11% compared to 2018) |

| Cruise terminal positioning | Alto Fondale and Porto Mediceo; independent management; market position as premium/luxury cruises tours. In expansion, but still interstitial. | 3 cruise terminals: Alcantara, Santa Apolonia, and Jardim do Tabaco Quay. Market position as a turnaround port for large international cruises companies Exponential growth, but still niche business segment |

| Port infrastructures | 11 Berths for cruise ships and ferries (3.5 km of port berths) 2 cruise terminals 1 ferry terminal Shore-side electric power supply plant | Port’s main access channel has 14 m depth 1500 m of berth quay (depths between 8 m and 12 m) 13,800 m2 of terminal facilities over 3 floors 1490 m of pier for multi length ships 3 cruise terminals (north bank of the River Tagus) 4 recreational docks: Alcantara, Belem, Bom Sucesso, and Santo Amaro |

| Terminal features | Waiting area Info point Check-in desks Security check Ticket offices Cash dispenser Internet Point Wi-Fi Parking Bar and cafeteria Shopping center Self-service restaurant | Waiting area Wi-Fi Info tour for experiencing Lisbon Duty-free stores Ship storage area Onsite equipment (forklift, crane, and others) Supplying services (water, provisions, and others) Fully automated gangway system Post office Public phones Souvenirs shops Wine shops |

| Terminal logistics | Bus to Pisa international airport (fly and cruise) Car rental booth (drive and cruise) Taxi parking Chauffeur service parking Shuttle bus to Livorno city center | Connection to Lisbon railway station; 80 bus parking spaces at Alcantara terminal Taxi parking Cars rental 360 car parking spaces Coach park Shuttle bus to Lisbon city center |

| Inland assets | Florence–Pisa–Lucca (90% of total excursions) Cinque Terre (4.37%) San Gimignano/Volterra Etruscan coast excursions, wine and oil roads, Tuscan museums, wine tasting, truffle hunting, farmhouse visiting, etc.) | City of Lisbon ** (90%) Sintra (28%) Cascais (17%) Fatima (10%) |

| Additional services | -Event and exhibition centers -Tour operator booth | -Panoramic view terrace -Music concert hall |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, M.; Radicchi, E.; Zagnoli, P. Port’s Role as a Determinant of Cruise Destination Socio-Economic Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174542

Santos M, Radicchi E, Zagnoli P. Port’s Role as a Determinant of Cruise Destination Socio-Economic Sustainability. Sustainability. 2019; 11(17):4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174542

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Maria, Elena Radicchi, and Patrizia Zagnoli. 2019. "Port’s Role as a Determinant of Cruise Destination Socio-Economic Sustainability" Sustainability 11, no. 17: 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174542

APA StyleSantos, M., Radicchi, E., & Zagnoli, P. (2019). Port’s Role as a Determinant of Cruise Destination Socio-Economic Sustainability. Sustainability, 11(17), 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174542