A Systematic Review on the Toxicology of European Union-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Cell Lines and Mammalian Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identification and characterization of the EU-approved triazole fungicides;

- Identification of exposure data and toxicokinetic profile;

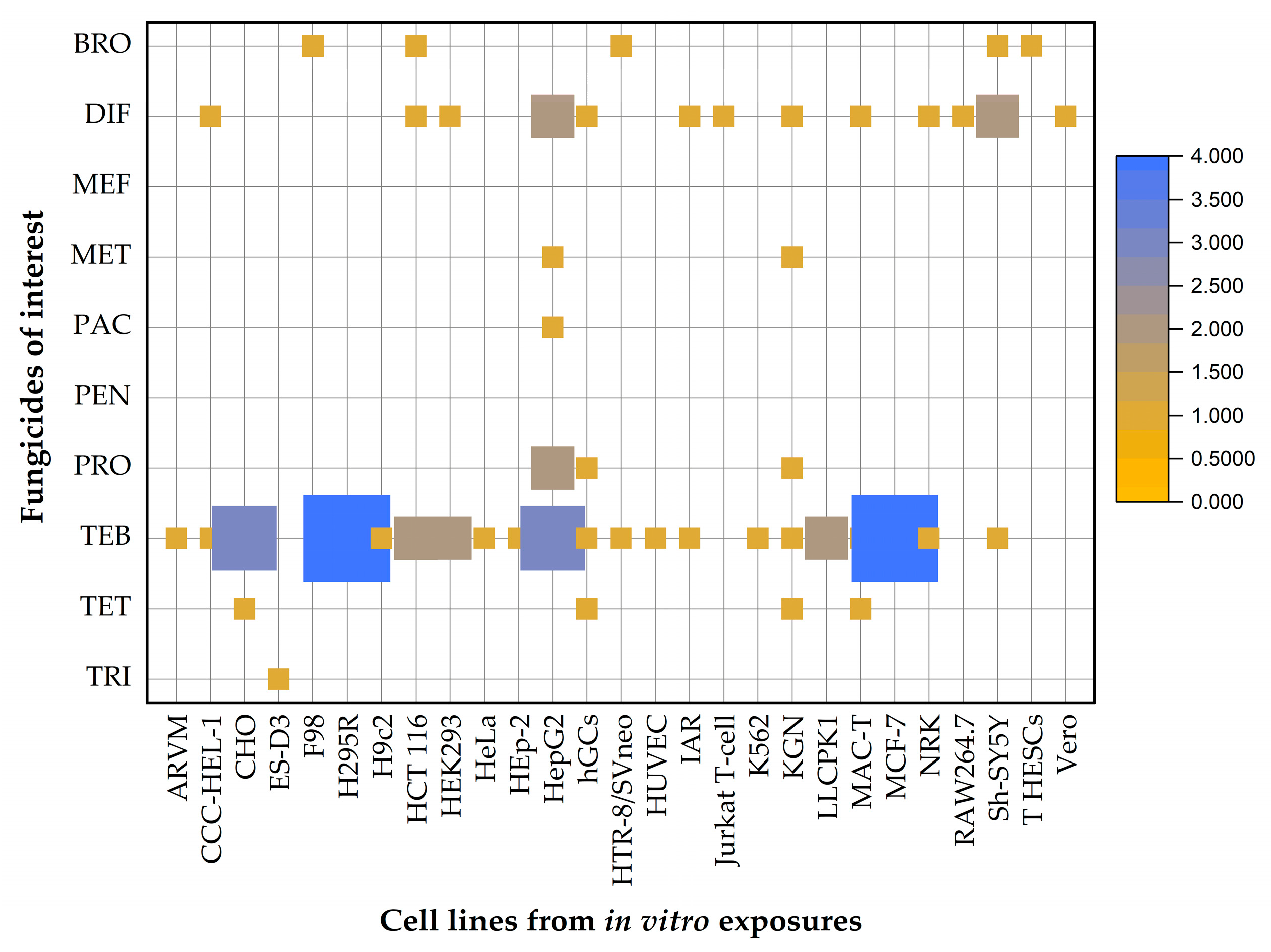

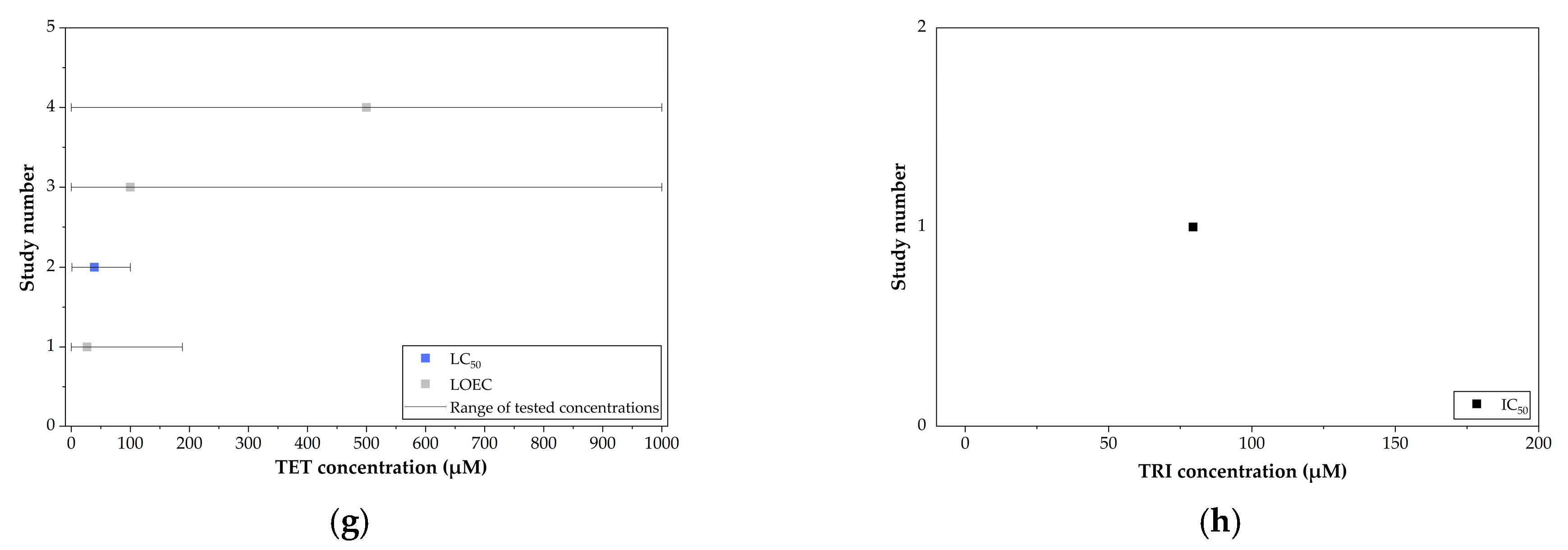

- Evaluation of in vitro toxicity in mammalian cell lines;

- Examination of potential molecular mechanisms of toxicity derived from in vitro data;

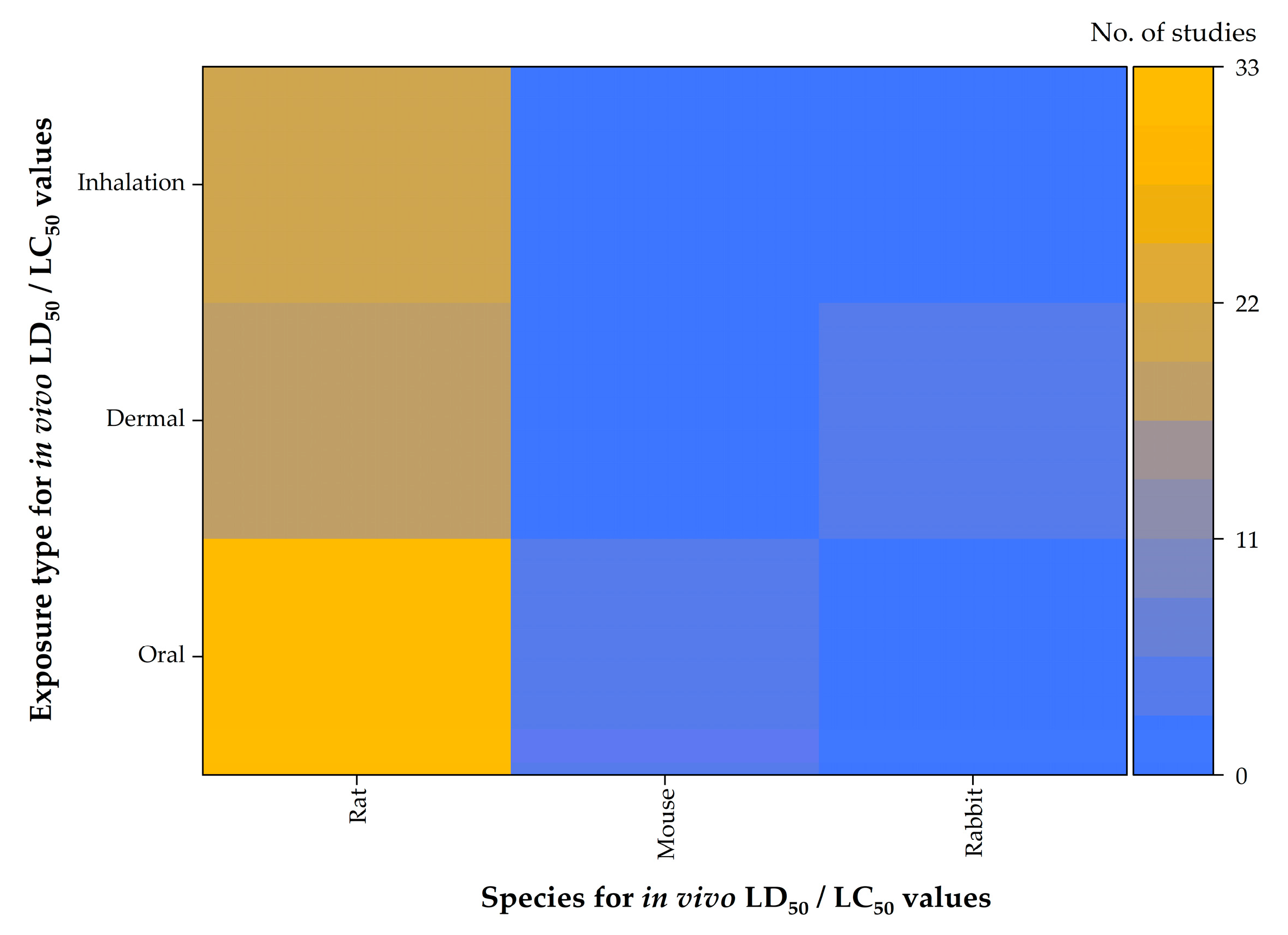

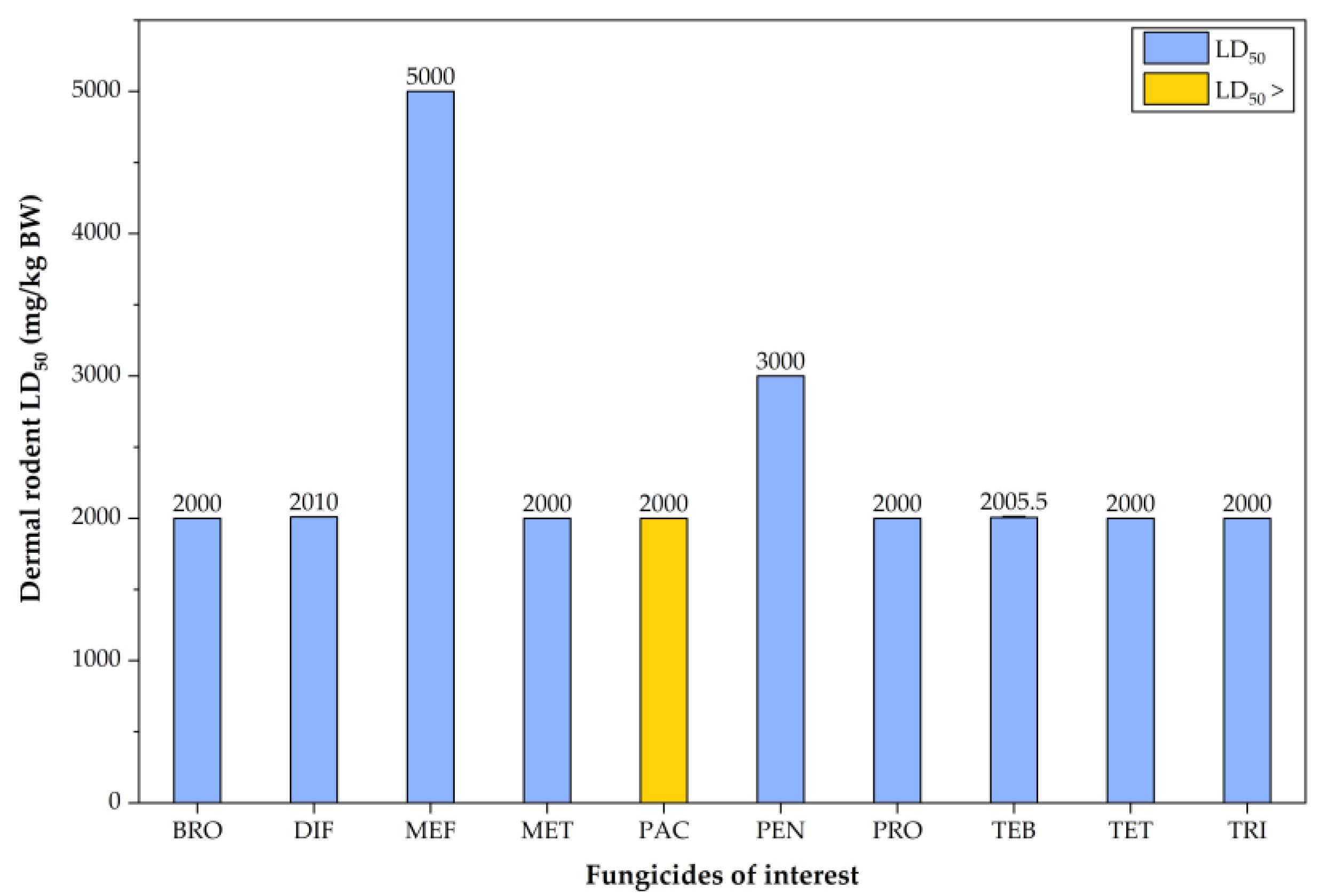

- Review and analysis of in vivo toxicity data in rodent models, including oral, dermal, and inhalation exposures;

- Assessment of qualitative evidence on specific and general human health issues linked to triazole fungicide exposure according to the Pesticide Properties DataBase records.

2. European Union-Approved Triazole Fungicides

3. Exposure Data and Toxicokinetic Profile of EU-Approved Triazole Fungicides

4. Literature Data-Mining and Analysis Workflow

5. In Vitro Toxicity of EU-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Mammalian Cell Lines

6. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying In Vitro Toxicity of EU-Approved Triazole Fungicides

7. In Vivo Toxicity of EU-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Rodent Models

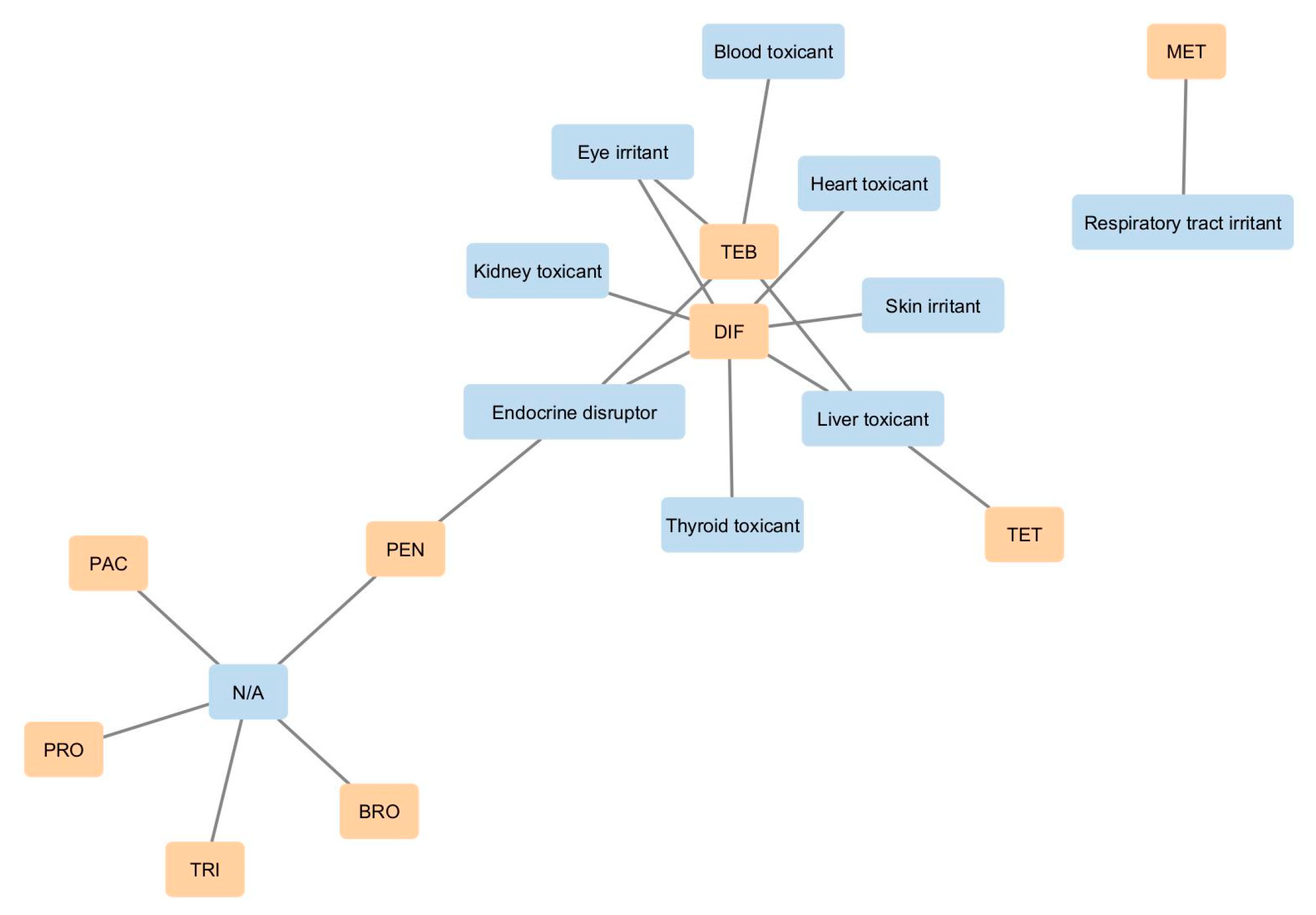

8. Qualitative Human Health Effects Associated with EU-Approved Triazole Fungicide Exposure

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fagundes, T.R.; Coradi, C.; Vacario, B.G.L.; de Morais Valentim, J.M.B.; Panis, C. Global Evidence on Monitoring Human Pesticide Exposure. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsenso, F. Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives on Chemical Risk Assessment of Pesticides in the European Union. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Principles and Methods for the Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241572408 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Pesticide Residues in Food: Report 2024: Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240113954 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- D’Amore, T.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Chemical Food Safety in Europe Under the Spotlight: Principles, Regulatory Framework and Roadmap for Future Directions. Foods 2025, 14, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament & Council. Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of 21 October 2009 on the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market (Repealing Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC). 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32009R1107 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- European Parliament & Council. Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides (Text with EEA Relevance). 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/128/oj/eng (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Zubrod, J.P.; Feckler, A.; Englert, D.; Koksharova, N.; Rosenfeldt, R.R.; Seitz, F.; Schulz, R.; Bundschuh, M. Inorganic fungicides as routinely applied in organic and conventional agriculture can increase palatability but reduce microbial decomposition of leaf litter. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, V.; Kosma, C.; Karabagias, I.K.; Zotos, A.; Pittaras, A.; Kehayias, G. Fungicides in Europe During the Twenty-first Century: A Comparative Assessment Using Agri-environmental Indices of EU27. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. How Pesticides are Regulated in the EU—EFSA and the Assessment of Active Substances. 2002. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/corporate_publications/files/Pesticides-ebook-180424.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority; Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Marchese, E.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2023 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.L.; Voiculescu, D.I.; Filip, M.; Ostafe, V.; Isvoran, A. Effects of Triazole Fungicides on Soil Microbiota and on the Activities of Enzymes Found in Soil: A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, T.M.A.; Abdelkareem, E.M.; Bouqellah, N.A.; Shokr, S.A. Triazole Fungicide Residues and Their Inhibitory Effect on Some Trichothecenes Mycotoxin Excretion in Wheat Grains. Molecules 2021, 26, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, I.A.; Sabir, J.S.M.; Asseri, A.H.; Wani, M.Y.; Ahmad, A. Triazole Derivatives Target 14α-Demethylase (LDM) Enzyme in Candida albicans Causing Ergosterol Biosynthesis Inhibition. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Perez, C.; Cramer, R.A. Targeting fungal lipid synthesis for antifungal drug development and potentiation of contemporary antifungals. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Dobson, H. The benefits of pesticides to mankind and the environment. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, J.; Pető, K.; Nagy, J. Pesticide productivity and food security. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevao, B.; Semple, K.T.; Jones, K.C. Bound pesticide residues in soils: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 108, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, W.F. Pesticide contamination of ground water in the United States—A review. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 1990, 25, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, A.; Osei-Fosu, P.; Dubey, B.; Kingsford-Adaboh, R.; Ziwu, C.; Asante, I. Pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables in Ghana: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 18966–18987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, S.M.; Ray, A.K.; Barghi, S. Water Pollution and Agriculture Pesticide. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.M.; Seibert, D.; Quesada, H.B.; de Jesus Bassetti, F.; Fagundes-Klen, M.R.; Bergamasco, R. Occurrence, impacts and general aspects of pesticides in surface water: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 135, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botnaru, A.A.; Lupu, A.; Morariu, P.C.; Nedelcu, A.H.; Morariu, B.A.; Di Gioia, M.L.; Lupu, V.V.; Dragostin, O.M.; Caba, I.-C.; Anton, E.; et al. Innovative Analytical Approaches for Food Pesticide Residue Detection: Towards One Health-Oriented Risk Monitoring. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Khan, A.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Deng, Y.; He, N. Aptasensors for pesticide detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 130, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimalt, S.; Dehouck, P. Review of analytical methods for the determination of pesticide residues in grapes. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1433, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish, G.P.; Ashokrao, D.M.; Arun, S.K. Microbial degradation of pesticide: A review. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 11, 992–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marican, A.; Durán-Lara, E.F. A review on pesticide removal through different processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 2051–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni, M.; Colosio, C.; Ferioli, A.; Fait, A. Biological Monitoring of Pesticide Exposure: A review. Introduction. Toxicology 2000, 143, 5–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprea, C.; Colosio, C.; Mammone, T.; Minoia, C.; Maroni, M. Biological monitoring of pesticide exposure: A review of analytical methods. J. Chromatogr. B 2002, 769, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kabir, E.; Jahan, S.A. Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, K.; Jacobsen, C.S.; Torsvik, V.; Sørensen, J. Pesticide effects on bacterial diversity in agricultural soils—A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2001, 33, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekár, S. Spiders (Araneae) in the pesticide world: An ecotoxicological review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I.; Matviishyn, T.M.; Husak, V.V.; Storey, J.M.; Storey, K.B. Pesticide toxicity: A mechanistic approach. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 1101–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, L.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.; Grewal, A.S.; Srivastav, A.L.; Kaushal, J. An extensive review on the consequences of chemical pesticides on human health and environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yan, H. Pesticide exposure and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyabina, V.P.; Esimbekova, E.N.; Kopylova, K.V.; Kratasyuk, V.A. Pesticides: Formulants, distribution pathways and effects on human health—A review. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Bandral, S.S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, M.A.; Rani, N.; Singh, T.G.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevas, T.; Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M.; Stefanou, S.E. Designing the emerging EU pesticide policy: A literature review. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2013, 64, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baibakova, E.V.; Nefedjeva, E.E.; Suska-Malawska, M.; Wilk, M.; Sevriukova, G.A.; Zheltobriukhov, V.F. Modern Fungicides: Mechanisms of Action, Fungal Resistance and Phytotoxic Effects. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2019, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hamel, C.; Vujanovic, V.; Gan, Y. Fungicide: Modes of Action and Possible Impact on Nontarget Microorganisms. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 130289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.W.; Rossato, L.; Goldman, G.H.; Santos, D.A. Fungicide effects on human fungal pathogens: Cross-resistance to medical drugs and beyond. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1010073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gikas, G.D.; Parlakidis, P.; Mavropoulos, T.; Vryzas, Z. Particularities of Fungicides and Factors Affecting Their Fate and Removal Efficacy: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrod, J.P.; Bundschuh, M.; Arts, G.; Brühl, C.A.; Imfeld, G.; Knäbel, A.; Payraudeau, S.; Rasmussen, J.J.; Rohr, J.; Scharmüller, A.; et al. Fungicides: An Overlooked Pesticide Class? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3347–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, M.G.; Thompson, L.J.; Carolan, J.C.; Stout, J.C.; Stanley, D.A. Fungicides, herbicides and bees: A systematic review of existing research and methods. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeau, S.; Raine, N.E. Fungicides and bees: A review of exposure and risk. Environ. Int. 2022, 165, 107311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, M.; Čadková, E.; Chrastný, V.; Bordas, F.; Bollinger, J.-C. Contamination of vineyard soils with fungicides: A review of environmental and toxicological aspects. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lini, R.S.; Scanferla, D.T.P.; de Oliveira, N.G.; Aguera, R.G.; Santos, T.d.S.; Teixeira, J.J.V.; Kaneshima, A.M.d.S.; Mossini, S.A.G. Fungicides as a risk factor for the development of neurological diseases and disorders in humans: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2024, 54, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas Cusick, H. Fungicides. In Farm Toxicology: A Primer for Rural Healthcare Practitioners; Meggs, W.J., Langley, R.L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, F.J.; Santana, F.M.; Lau, D.; Del Ponte, E.M. Quantitative Review of the Effects of Triazole and Benzimidazole Fungicides on Fusarium Head Blight and Wheat Yield in Brazil. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, M.; Klix, M.B.; Klink, H.; Verreet, J.A. Quantifying the effects of previous crop, tillage, cultivar and triazole fungicides on the deoxynivalenol content of wheat grain—A review. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2006, 113, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.L.; Voiculescu, D.I.; Ostafe, V.; Ciorsac, A.; Isvoran, A. A review of the toxicity of triazole fungicides approved to be used in European Union to the soil and aqueous environment. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Chem. 2022, 33, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Cheng, H.; Martyniuk, C.J. A comprehensive review of 1,2,4-triazole fungicide toxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio): A mitochondrial and metabolic perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobezhimova, T.P.; Korsukova, A.V.; Dorofeev, N.V.; Grabelnych, O.I. Physiological effects of triazole fungicides in plants. Proc. Universities. Appl. Chem. Biotechnol. 2019, 9, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, L.V.B.; de Aguiar, G.C.; Pereira, A.M.R.d.S.; Thomaz, L.d.S.C.; de Oliveira, I.C.C.d.S.; Mari, R.d.B.; Perobelli, J.E.; Ribeiro, D.A.; da Silva, R.C.B. Triazole fungicides induce genotoxicity via oxidative stress in mammals in vivo: A comprehensive review. Rev. Environ. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Friedman, K.; Papineni, S.; Marty, M.S.; Yi, K.D.; Goetz, A.K.; Rasoulpour, R.J.; Kwiatkowski, P.; Wolf, D.C.; Blacker, A.M.; Peffer, R.C. A predictive data-driven framework for endocrine prioritization: A triazole fungicide case study. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2016, 46, 785–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Pandey, G. Understanding the impact of triazoles on female fertility and embryo development: Mechanisms and implications. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Liang, X. Advances in Selective Bioactivity and Toxicity of Chiral Triazole Fungicides and Their Selective Behavior in Mammals. Chirality 2025, 37, e70055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Web of Science. Web of Science Advanced Search Query Builder. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/advanced-search (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- European Commission. EU Pesticides Database—Active Substances. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/start/screen/active-substances (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.A.; Tzilivakis, J.; Warner, D.J.; Green, A. An international database for pesticide risk assessments and management. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2016, 22, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Bromuconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/97.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Difenoconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/230.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Mefentrifluconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/3098.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Metconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/451.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Paclobutrazol. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/504.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Penconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/509.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Prothioconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/559.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Tebuconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/610.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Tetraconazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/626.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pesticide Properties DataBase. Triticonazole. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/673.htm#3 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Voiculescu, D.I.; Roman, D.L.; Ostafe, V.; Isvoran, A. A Cheminformatics Study Regarding the Human Health Risks Assessment of the Stereoisomers of Difenoconazole. Molecules 2022, 27, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridan, I.M.; Alecu, A.C.; Isvoran, A. Prediction of ADME-Tox properties and toxicological endpoints of triazole fungicides used for cereals protection. ADMET DMPK 2019, 7, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.L.; Voiculescu, D.I.; Matica, M.A.; Baerle, V.; Filimon, M.N.; Ostafe, V.; Isvoran, A. Assessment of the Effects of Triticonazole on Soil and Human Health. Molecules 2022, 27, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovani, I.S.; Yamamoto, P.A.; da Silva, R.M.; Lopes, N.P.; de Moraes, N.V.; de Oliveira, A.R.M. Unveiling CYP450 inhibition by the pesticide prothioconazole through integrated in vitro studies and PBPK modeling. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2845–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovani, I.S.; Santos Barbetta, M.F.; Moreira da Silva, R.; Lopes, N.P.; Moraes de Oliveira, A.R. In vitro-in vivo correlation of the chiral pesticide prothioconazole after interaction with human CYP450 enzymes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 163, 112947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampalakis, G. Underestimations in the In Silico-Predicted Toxicities of V-Agents. J. Xenobiot. 2023, 13, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Open Science Framework. View Only Link of Open Science Framwork Registration That Is Under Embargo. Available online: https://osf.io/nvz5x/overview?view_only=96796d5395344b10b3755d3e79dde0a8 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell. Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Almedeny, S.A.; Sahib, Z.H.; Al Mukhtar, E.J.; Alkelaby, K.K. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Effect of the Epoxyconazole and Difenoconazole on Human Colorectal Cancer HCT116 Cell Line. Int. J. Drug Deliv. Technol. 2022, 12, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrioli, N.B.; Nieves, M.; Poltronieri, M.; Bonzon, C.; Chaufan, G. Genotoxic effects induced for sub-cytotoxic concentrations of tebuconazole fungicide in HEp-2 cell line. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2023, 373, 110385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrón Cuenca, J.; de Oliveira Galvão, M.F.; Ünlü Endirlik, B.; Tirado, N.; Dreij, K. In vitro cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of single and combined pesticides used by Bolivian farmers. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2022, 63, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülbül, E.; Özhan, G.; Bülbül, E.; Bülbül, G.Ö.E.; Özhan, G. Cytotoxic effects of triazole fungucides. J. Fac. Pharm. Istanb. Univ. 2012, 42, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, S.L.; Hartman, G.L.; Wagner, E.D.; Plewa, M.J. Mammalian Cell Cytotoxicity Analysis of Soybean Rust Fungicides. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 78, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.; Barenys, M.; Hermsen, S.A.B.; Verhoef, A.; Ossendorp, B.C.; Bessems, J.G.M.; Piersma, A.H. Comparison of the mouse Embryonic Stem cell Test, the rat Whole Embryo Culture and the Zebrafish Embryotoxicity Test as alternative methods for developmental toxicity testing of six 1,2,4-triazoles. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2011, 253, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Wang, X.; Qian, M.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Y. Impacts of prothioconazole and prothioconazole-desthio on bile acid and glucolipid metabolism: Upregulation of CYP7A1 expression in HepG2 cells. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2024, 198, 105702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.A.; Song, J.; Ham, J.; An, G.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Tetraconazole interrupts mitochondrial function and intracellular calcium levels leading to apoptosis of bovine mammary epithelial cells. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2023, 191, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, W.; Lim, W.; Song, G.; Park, S. Bromuconazole impairs implantation process through cellular stress response in human trophoblast and endometrial cells. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2025, 214, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærstad, M.B.; Taxvig, C.; Nellemann, C.; Vinggaard, A.M.; Andersen, H.R. Endocrine disrupting effects in vitro of conazole antifungals used as pesticides and pharmaceuticals. Reprod. Toxicol. 2010, 30, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.-C.; Kim, D.-H.; Jeong, C.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Han, J.-H.; Lim, S.-J.; Shin, D.-M.; Kim, D.-W.; Han, S.-G. Tebuconazole Fungicide Induces Lipid Accumulation and Oxidative Stress in HepG2 Cells. Foods 2021, 10, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-Y.; Lee, R.; Park, H.-J. Tebuconazole Induces ER-Stress-Mediated Cell Death in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cell Lines. Toxics 2023, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F.G.; Silva, C.d.P.M.; Miranda, R.G.; Dorta, D.J. Comparison of in vitro toxicity in HepG2 cells: Toxicological role of Tebuconazole-tert-butyl-hydroxy in exposure to the fungicide Tebuconazole. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2024, 202, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, B.; Xu, W.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Tao, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. DNA damage and cell apoptosis induced by fungicide difenoconazole in mouse mononuclear macrophage RAW264.7. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-C.; Liu, S.-Y.; Li, H.-R.; Meng, F.-B.; Qiu, J.; Qian, Y.-Z.; Xu, Y.-Y. Use of Transcriptomics to Reveal the Joint Immunotoxicity Mechanism Initiated by Difenoconazole and Chlorothalonil in the Human Jurkat T-Cell Line. Foods 2024, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, N.; Song, X.; Deng, M.; Sun, R.; Wang, P.; Cao, L. Specific Hepatorenal Toxicity and Cross-Species Susceptibility of Eight Representative Pesticides. Toxics 2025, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lu, S.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; Sun, G.; Yang, M.; Sun, X. Paclobutrazol exposure induces apoptosis and impairs autophagy in hepatocytes via the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, M.-J.; Lee, W.-Y.; Park, H.-J. Difenoconazole Induced Damage of Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells via ER Stress and Inflammatory Response. Cells 2024, 13, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, J.; Zhou, J.; Shen, Y.; Lin, R.; Hu, H.; Zeng, K.; Bi, H.; Huang, M.; Yu, L.; Zeng, S.; et al. Studies on the interaction of five triazole fungicides with human renal transporters in cells. Toxicol. In Vitr. 2023, 88, 105555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othmène, Y.B.; Kevin, M.; Ahmed, K.; Salem, I.B.; Anissa, B.; Salwa, A.-E.; Christophe, L. Tebuconazole induces ROS-dependent cardiac cell toxicity by activating DNA damage and mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 204, 111040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othmène, Y.B.; Kevin, M.; Anissa, B.; Ahmed, K.; Intidhar, B.S.; Manel, B.; Salwa, A.-E.; Christophe, L. Triazole fungicide tebuconazole induces apoptosis through ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 94, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othmène, Y.B.; Salem, I.B.; Hamdi, H.; Annabi, E.; Abid-Essefi, S. Tebuconazole induced cytotoxic and genotoxic effects in HCT116 cells through ROS generation. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2021, 174, 104797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Lu, L.; Wang, J.; Zheng, C.; Fu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Jin, Y.; Zhuang, S. The fungicide difenoconazole alters mRNA expression levels of human CYP3A4 in HepG2 cells. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 15, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjiba-Touati, K.; Ayed-Boussema, I.; Hamdi, H.; Abid, S. Genotoxic damage and apoptosis in rat glioma (F98) cell line following exposure to bromuconazole. NeuroToxicology 2023, 94, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjiba-Touati, K.; Ayed-Boussema, I.; Hamdi, H.; Azzebi, A.; Abid, S. Bromuconazole fungicide induces cell cycle arrest and apoptotic cell death in cultured human colon carcinoma cells (HCT116) via oxidative stress process. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjiba-Touati, K.; Hamdi, H.; M’nassri, A.; Rich, S.; Mokni, M.; Abid, S. Brain injury, genotoxic damage and oxidative stress induced by Bromuconazole in male Wistar rats and in SH-SY5Y cell line. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.L.; Souders, C.L.; Pena-Delgado, C.J.; Nguyen, K.T.; Kroyter, N.; Ahmadie, N.E.; Aristizabal-Henao, J.J.; Bowden, J.A.; Martyniuk, C.J. Neurotoxicity assessment of triazole fungicides on mitochondrial oxidative respiration and lipids in differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. NeuroToxicology 2020, 80, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, L.; Estienne, A.; Bongrani, A.; Ramé, C.; Caria, G.; Froger, C.; Jolivet, C.; Henriot, A.; Amalric, L.; Corbin, E.; et al. The epoxiconazole and tebuconazole fungicides impair granulosa cells functions partly through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) signalling with contrasted effects in obese, normo-weight and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) patients. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 12, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, L.; Estienne, A.; Caria, G.; Ramé, C.; Jolivet, C.; Froger, C.; Henriot, A.; Amalric, L.; Guérif, F.; Froment, P.; et al. In vitro exposure to triazoles used as fungicides impairs human granulosa cells steroidogenesis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 104, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevim, Ç.; Taghizadehghalehjoughi, A.; Kara, M. Effects of chlorpyrifos-methyl, chlormequat, deltamethrin, glyphosate, pirimiphos-methyl, tebuconazole and their mixture on oxidative stress and toxicity in HUVEC cell line. İstanb. J. Pharm. 2021, 51, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Yan, S.; Meng, Z.; Sun, W.; Yan, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Diao, J.; Li, L.; et al. Widening the Lens on Prothioconazole and Its Metabolite Prothioconazole-Desthio: Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Mediated Reproductive Disorders through in Vivo, in Vitro, and in Silico Studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17890–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ma, M.; Chen, C.; Yang, X.; Qian, Y. Three widely used pesticides and their mixtures induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis through the ROS-related caspase pathway in HepG2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 152, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ni, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, B.; Xie, T.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Tao, L.; Zhang, Y. Difenoconazole induces oxidative DNA damage and mitochondria mediated apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, X.; Muhayimana, S.; Liu, X.; Xue, Y.; Huang, Q. Comparative cytotoxic effects of five commonly used triazole alcohol fungicides on human cells of different tissue types. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2020, 55, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-B. Chiral analysis and semi-preparative separation of metconazole stereoisomers by supercritical fluid chromatography and cytotoxicity assessment in vitro. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, 2300655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Liu, J. Triazole fungicide tebuconazole disrupts human placental trophoblast cell functions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 308, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassy, M.A.; Marzouk, M.A.; Nasr, H.M.; Mansy, A. Effect of imidacloprid and tetraconazole on various hematological and biochemical parameters in male albino rats (Rattus norvegious). J. Political Sci. Public Aff. 2014, 2, 1000122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. Evaluation of the New Active Prothioconazole in the Product Redigo Fungicidal Seed Treatment. 2007. Available online: https://www.apvma.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication/13941-prs-prothioconazole.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- El-Shershaby, A.E.-F.M.; Lashein, F.E.-D.M.; Seleem, A.A.; Ahmed, A.A. Toxicological potential of penconazole on early embryogenesis of white mice Mus musculus in either pre- or post-implantation exposure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 9943–9956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion regarding the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance triticonazole. EFSA J. 2005, 3, 33ar. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion regarding the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance bromuconazole. EFSA J. 2008, 6, 136r. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion regarding the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance tetraconazole. EFSA J. 2008, 152, 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance bromuconazole. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance paclobutrazol. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance difenoconazole. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Toxicological Evaluation of Penconazole; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015.

- Hariyadi, H.R. The presence of bromuconazole fungicide pollutant in organic waste anaerobic fermentation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 60, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwanes, S.A.; Mohamed, R.A.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Abd El-Rahman, H.A. Ginger reserves testicular spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in difenoconazole-intoxicated rats by conducting oxidative stress, apoptosis and proliferation. Andrologia 2022, 54, e14241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klix, M.B.; Verreet, J.-A.; Beyer, M. Comparison of the declining triazole sensitivity of Gibberella zeae and increased sensitivity achieved by advances in triazole fungicide development. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lian, T.; Su, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Construction of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of paclobutrazol and exposure estimation in the human body. Toxicology 2024, 505, 153841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.E.s.; El-Sayed, M.M.; Arief, M.M.; Mahmoud, A.A. Evaluation of the ameliorative effect of Cinnamon cassia against metabolic disorder and thyroid hormonal disruption following treatment with difenoconazole fungicide in the male albino rats. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.H.; Elshama, S.S.; Osman, A.S.; El-Hameed, A.K.A. Toxicological and pathological evaluation of prolonged bromuconazole fungicide exposure in male rats. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2011, 79, 555–564. Available online: https://scholar.cu.edu.eg/?q=yomnakhaled/files/cairo_univeristy_journal.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Rjiba-Touati, K.; Hamdi, H.; M’nassri, A.; Guedri, Y.; Mokni, M.; Abid, S. Bromuconazole caused genotoxicity and hepatic and renal damage via oxidative stress process in Wistar rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 14111–14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solera ATO, L. Safety Data Sheet - Tebuconazole. 2015. Available online: https://www.greenbook.net/solera-source-dynamics/tebuconazole-36f (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Tesh, S.A.; Tesh, J.M.; Fegert, I.; Buesen, R.; Schneider, S.; Mentzel, T.; van Ravenzwaay, B.; Stinchcombe, S. Innovative selection approach for a new antifungal agent mefentrifluconazole (Revysol®) and the impact upon its toxicity profile. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 106, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide Fact Sheet—Tetraconazole. 2005. Available online: https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/registration/fs_PC-120603_01-Apr-05.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide Fact Sheet—Triticonazole. 2005. Available online: https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/cleared_reviews/csr_PC-125620_1-Nov-00_a.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide Fact Sheet—Metconazole. 2007. Available online: https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/registration/fs_PC-125619_01-Sep-07.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Xu, M.; Yang, F. Integrated gender-related effects of profenofos and paclobutrazol on neurotransmitters in mouse. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Liu, Z.; Pi, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, F.; Liu, Z. Network Pharmacology Combined with Metabolomics Approach to Investigate the Toxicity Mechanism of Paclobutrazol. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.; Schwarz, M.; Burkholder, I.; Kopp-Schneider, A.; Edler, L.; Kinsner-Ovaskainen, A.; Hartung, T.; Hoffmann, S. “ToxRTool”, a new tool to assess the reliability of toxicological data. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 189, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.C.; Sohn, H.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, D.M.; Jeong, C.H.; Chang, Y.H.; Yune, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, D.-W.; Kim, S.H.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Study on the Toxic Effects of Propiconazole Fungicide in the Pathogenesis of Liver Fibrosis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7399–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.; Garry, V.F. In vitro studies of cellular and molecular developmental toxicity of adjuvants, herbicides, and fungicides commonly used in Red River Valley, Minnesota. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2000, 60, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, J.; Olguín, N.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Suñol, C. Toxicity evaluation of new agricultural fungicides in primary cultured cortical neurons. Environ. Res. 2015, 140, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safandeev, V.V.; Beloedova, N.S.; Poroșin, M.A.; Bogdanova, A.V.; Sinitskaya, T.A. Characterization of a phenylpyrrole derivative fungicide in an acute oral toxicology study in rats. Health Care Kyrg. Sci. Pract. J. 2023, 1, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Triazole Fungicide | Status of Approval | Approval Expiration Date |

|---|---|---|

| Azaconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Bitertanol | Not approved | 29 August 2013 |

| Bromuconazole | Approved | 30 April 2027 |

| Cyproconazole | Not approved | 31 May 2021 |

| Difenoconazole | Approved | 15 March 2026 |

| Diniconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Epoxiconazole | Not approved | 30 April 2020 |

| Etaconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Fenbuconazole | Not approved | 30 April 2021 |

| Fluconazole | N/A | N/A |

| Fluotrimazole | N/A | N/A |

| Fluoxytioconazole | N/A | N/A |

| Fluquinconazole | Not approved | 31 December 2021 |

| Flusilazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Flutriafol | Not approved | 31 May 2021 |

| Furconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Hexaconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Imibenconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Ipconazole | Not approved | 31 May 2023 |

| Ipfentrifluconazole | N/A | N/A |

| Mefentrifluconazole | Approved | 20 March 2029 |

| Metconazole | Approved | 31 August 2031 |

| Myclobutanil | Not approved | 31 May 2021 |

| Paclobutrazol | Approved | 31 August 2026 |

| Penconazole | Approved | 15 October 2026 |

| Propiconazole | Not approved | 19 December 2018 |

| Prothioconazole | Approved | 31 March 2027 |

| Quinconazole | N/A | N/A |

| Simeconazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Tebuconazole | Approved | 15 August 2026 |

| Tetraconazole | Approved | 31 March 2027 |

| Triadimefon | Not approved | N/A |

| Triadimenol | Not approved | 31 August 2019 |

| Tricyclazole | Not approved | N/A |

| Triticonazole | Approved | 31 January 2027 |

| Bromuconazole (BRO) | Difenoconazole (DIF) |

|---|---|

| MW: 377.1 g/mol | MW: 406.3 g/mol |

|  |

| Mefentrifluconazole (MEF) | Metconazole (MET) |

| MW: 397.8 g/mol | MW: 319.8 g/mol |

|  |

| Paclobutrazol (PAC) | Penconazole (PEN) |

| MW: 293.79 g/mol | MW: 284.18 g/mol |

|  |

| Prothioconazole (PRO) | Tebuconazole (TEB) |

| MW: 344.3 g/mol | MW: 307.82 g/mol |

|  |

| Tetraconazole (TET) | Triticonazole (TRI) |

| MW: 372.14 g/mol | MW: 317.8 g/mol |

|  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vulpe, C.-B.; Iachimov-Datcu, A.-D.; Pujicic, A.; Agachi, B.-V. A Systematic Review on the Toxicology of European Union-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Cell Lines and Mammalian Models. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060208

Vulpe C-B, Iachimov-Datcu A-D, Pujicic A, Agachi B-V. A Systematic Review on the Toxicology of European Union-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Cell Lines and Mammalian Models. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060208

Chicago/Turabian StyleVulpe, Constantina-Bianca, Adina-Daniela Iachimov-Datcu, Andrijana Pujicic, and Bianca-Vanesa Agachi. 2025. "A Systematic Review on the Toxicology of European Union-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Cell Lines and Mammalian Models" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060208

APA StyleVulpe, C.-B., Iachimov-Datcu, A.-D., Pujicic, A., & Agachi, B.-V. (2025). A Systematic Review on the Toxicology of European Union-Approved Triazole Fungicides in Cell Lines and Mammalian Models. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060208