Abstract

Forests are one of the most predominant types of land usage in Portugal and are highly relevant in terms of environmental, economic, social, and political factors. Increasing the value and the resilience of the Portuguese forest, defining adequate policies, and aligning forest research with society needs requires a truthful comprehension of the most relevant challenges in this sector. This study identifies and analyzes the most relevant needs and challenges impacting the Portuguese forestry sector, both currently and over a five-year period, from the stakeholder’s perspective. A participatory approach was employed, engaging national and regional forest stakeholders, to ensure a realistic vision of the forest sector in Portugal. A total of 116 topics were identified, with a predominance of immediate challenges over future information needs, underscoring the urgent pressures on the sector. Environmental/ecological and policy issues dominated the identified needs and challenges, reflecting the urgency for strategic interventions in these areas. A significant emphasis was placed on the mitigation of climate change impacts, mainly associated with biotic and abiotic risks, promoting technological advanced forest management, and the sector valorization. Policy and legal issues, such as fragmented ownership and adequate economic and fiscal incentives, were also identified as major concerns. The findings highlight the interconnected nature of forestry challenges and the need for integrated, multidisciplinary, and transdisciplinary approaches, prioritizing research on climate impacts, developing adaptive management strategies, promoting stakeholder engagement, and enhancing capacity-building initiatives. The results of this study make it a relevant case study for other forest stakeholders in similar regions in Europe with comparative forest management models and can inspire new solutions for common challenges opening new research avenues for other forest related academics.

1. Introduction

Forests are one of the most crucial land uses in the world, providing a wide range of fundamental environmental, social, and economic services, highly contributing to carbon sequestration, water cycle regulation, biodiversity conservation, cultural values, recreational initiatives, and livelihood sustenance [1,2,3,4]. In Europe, the relevancy of the forest to the environment, society, and major sectors of activity is evidenced by the numerous political and research initiatives that focus on protecting forest resources and the ecosystem services they provide and enhancing the value of their externalities [5,6,7,8,9]. Due to the negative impacts of climate change and associated extreme weather events, as well as destructive anthropogenic activities, forests are currently stressed with multiple challenges and threats, such as habitat loss and fragmentation and the degeneration of forest ecosystem services, land use changes, and biodiversity loss [10,11]. While deforestation, climate change, biodiversity loss, and illegal logging are some of the broader challenges of the forests globally, depending on the location and circumstances, there are specific features associated with forest type and stage, geography, or political framework that can greatly differ [1,12,13,14].

European forests have been the subject of intense political debates and regulations across Europe over the years [15,16,17,18,19]. The European Green Deal [20] and the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 [21] recognize the central role of forests in climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation, highlighting the importance of joint efforts not only at the country, but also at European level [13]. Moreover, regulations such as the Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Law [19], the Nature Restoration Law [22], the Deforestation Regulation [15] and the emerging regulations for the carbon credit market [19] have dominated political agendas, and their ramifications deeply affect the Portuguese forest. The National Smart Specialisation Strategy (NSSS) for 2020, which included the forest as a priority aiming at the ‘development of forest ecosystems, sustainable production of raw and processed materials’, now revised and extended to 2030 and having forestry included in the pillars of great natural resources—forest, sea, and space—evidence the national importance of forests, concerning the ‘valorisation of endogenous resources associated with vegetable production and forestry through research and development of green biotechnology and the promotion of technologies and innovation in transformation’ [23]. Within the forest sector, the NSSS 2030 [23] identifies key categories as sustainable forest management focuses on maintaining and enhancing forest resources, such as implementing certification schemes for sustainable timber; forest conservation to protect biodiversity and natural habitats, for example, by establishing protected areas and wildlife corridors; forest-based bioeconomy that emphasizes the economic potential of forest resources, such as developing non-timber forest products and promoting ecotourism; climate change mitigation and adaptation addressing carbon sequestration and resilience strategies, like afforestation projects and adaptive management practices; and innovative forestry technologies that promote the development and application of advanced tools, such as remote sensing for forest monitoring and precision forestry techniques.

Forests are one of the most predominant land uses in Portugal [24], covering 36% of Portugal’s mainland, and its economy is largely dependent on forest-based products [7,25]. Increasing public understanding of the value of forests and associated risks can garner support for policy interventions and foster a culture of environmental concern [26], namely, for the effective implementation of the NSSS [23]. Recent scientific studies provide valuable insights into the specific challenges faced by Portuguese forests, such as the impact of climate change and management on cork oak woodlands [27,28], maritime pine stands [29,30], and wildfire management strategies [31,32,33]. Meneses et al. [34] investigated the impact of land-use dynamics on forest ecosystems, highlighting the interconnectedness of environmental and socio-economic factors in shaping forest landscapes.

To mitigate these challenges, Portugal has implemented a range of policies and strategies aimed at promoting sustainable forest management practices [35,36]. One relevant example is the National Forest Strategy that delineates objectives focusing on biodiversity conservation, rural development, and wildfire prevention, promoting adaptive management approaches [36]. Nevertheless, because the Portuguese forest is mostly owned by private landowners [37], the adequacy of public policies to the specificities of the sector and of the territory is particularly relevant. So, the collaboration between different interested parties of the forest sector, the academy, and the decision-makers is fundamental to identifying and effectively addressing the main challenges of the Portuguese forest and to ensuring its long-term sustainability and resilience to current and emerging global challenges [18,19]. By prioritizing sustainable management practices and inclusive strategies, countries and regions can work towards achieving global sustainability goals while ensuring the long-term health of forest ecosystems. Effective and sustainable forest management requires active involvement of interested parties and enhanced public awareness of forest-related issues. Participatory processes that integrate local knowledge with scientific expertise enable the development of solutions that enhance forest sustainability and outcomes [20]. By engaging all interested parties, including forest landowners, local communities, and other public or private entities, in participatory decision-making processes, the co-creation moments foster longer-term engagement and a sense of ownership and responsibility towards forest management [26,37,38]. Such events provide a platform for exchanging ideas, sharing experiences, and co-creating innovative strategies (e.g., tailored to spatial-explicit contexts, specific policies, local community’s needs), thereby promoting informed decisions regarding policy options and trade-offs and enhancing the resilience of forest ecosystems to environmental change [26].

Having Portugal mainland as territorial coverage, this work is driven by the question: What are the main forestry needs and challenges envisioned by the sector interested parties? The purpose of the research was (1) the identification of the sector’s most pressing challenges and information needs, i.e., knowledge gaps; (2) improved understanding of the causes and/or motivations underlying the main issues identified; and (3) co-development of recommendations to support actions and measures in response to the acknowledged challenges and needs. The research framework of this study was based on a participatory approach where key stakeholders from the Portuguese forestry sector were actively engaged in identifying and discussing the most relevant challenges and information needs of the sector. This study employed qualitative research to gather in-depth insights through a participatory workshop. In a sustainability context, the environmental perspective evidenced the need for climate change mitigation actions, the social perspective evidenced the professional valorization of the sector, and the economic perspective evidenced the need for economic and fiscal incentives.

2. Methodology

2.1. Workshop Design

This study aims to identify the main challenges and needs and elaborate on potential management actions and policy recommendations regarding the forestry sector in the mainland of Portugal. To achieve this, a participatory workshop was set up to gather insights from key Portuguese forest stakeholders, i.e., the sector interested parties. This was a qualitative study as the researchers aimed to explore a particular problem by gathering detailed information on a specific reality [39] and conduct an in-depth analysis of data from a specific situation, rather than generalizing or using representative samples of the population [40]. Due to its interpretive nature, the study involved a small but diverse and significant group of participants to explore and understand situations, actions, and meanings within a specific social context and to develop theories based on their views [41].

To ensure methodological rigor and to achieve active engagement and collaboration of workshop participants, the study employed a co-creation approach throughout its different steps [41].

The planning of the workshop included defining objectives, identifying the sector interested parties, selecting appropriate techniques and activities, and preparing support materials. The workshop was conducted in-person and divided into three parts, each with a different purpose and dynamic.

2.2. Participant Selection and Characterization

Participants were selected through purposive sampling based on their profile, representativeness of the sector, and diversity of associates they represent [40]. Their selection also considered their distribution in the forest sector value chain, their involvement in ongoing and past research projects, and collaborations between the academia and the Portuguese forestry sector. Of the 22 entities invited, 15 participated, including representatives from forestry producer associations, industrial companies, certification bodies, public and private financing entities, public–private interface organizations (e.g., collaborative laboratories), national authorities of the sector, and local authorities. The sample included five associations, one of which is an environmental NGO representing 36 subregional forest owners’ organizations and over 19,500 forest owners and hunters. Some members of this association, present in the workshop, were also promoters or users of socio-cultural forest services, mainly related to sustainable tourism, though this group was less represented. Another stakeholder, a Collaborative Laboratory (Co-Lab), represents seven corporate and industrial entities, ranging from the paper industry to the energy sector, as well as seven academic institutions and three national public organizations. A national authority, responsible for regulating and supporting the management of natural and forest areas in Portugal, also participated given its direct engagement with forest producers, hunters, technicians, fishers, and their respective associations. Additionally, an intermunicipal office representing at least 11 municipalities (local authorities) contributed to the discussion.

2.3. Data Collection

In preparation for the event, participants were asked to map the main needs and challenges for the forestry sector in the short and 5-year terms and to select those they considered most relevant to their activity. To facilitate data collection, the research team developed boards with categorized tables. During the first part of the workshop, after setting out the main objectives of the event, the participants were requested to place the mapped needs and challenges for their sector on a board using Post-it notes without discussing them with the other participants (Figure 1). The tables corresponded to categories of analysis related to challenges and information needs, both in the present and up to five years.

Figure 1.

A schematic overview of the first part of the workshop—mapping the needs and challenges of the sector in short and 5-year terms.

In the second part of the workshop, participants were randomly divided into four multidisciplinary groups, avoiding grouping by representatives of the same organization, sector, or interests. The participants were invited to discuss among themselves the various needs and challenges listed individually in the first part of the workshop, focusing on the forestry sector as a whole and not on the specific issues of their sector of activity. After this discussion and exchange of ideas, each group’s rapporteur orally presented the main conclusions from analyzing all the needs and challenges and what the group members considered to be a priority for the sector in our country. Each group was accompanied by a team member who acted as an additional note keeper and observer.

In the third part of the workshop, participants were requested to act individually again and vote on the 3 main needs and 3 most relevant challenges for the forestry sector in the short and 5-year terms identified on the board during the first part of the workshop. Although the initial request was limited to 3 needs and 3 challenges, some organizations voted for more challenges than intended.

2.4. Data Analysis

Following the workshop, a content analysis of the data compiled on the boards was conducted. The unit of analysis consisted of content excerpts from each Post-it that could be associated with a topic within a coding category [42]. A model for classifying and ordering the units of analysis was developed, following a mixed procedure, i.e., combining predefined categories from the theoretical framework with new categories that emerged from the collected data [42,43]. Data were analyzed for the 4 quadrants separately. Within each quadrant, the topics collected were grouped by Forest Wood Chain (FWC) themes, and within each theme, it was aggregated into PESTE (Policy, Economy, Social, Technological, Environmental/Ecological) categories, in agreement with the literature review presented by Nummelin et al. [44]. Since there were multiple topics identified by the stakeholders related to education and training, this category was added to the analysis. The units of analysis were organized into categories, providing a structured overview of the prominence of each theme and facilitating a synthesis and interpretation of the results [42]. The analysis is descriptive, detailing not only the findings but also the research process, including the setting, participants, and the role of the researchers [45]. Such detailed descriptions are crucial in qualitative research as they support the assessment of the study’s transferability and replicability to other contexts [46].

3. Results

3.1. Challenges and Information Needs Identified by the Individual Stakeholders

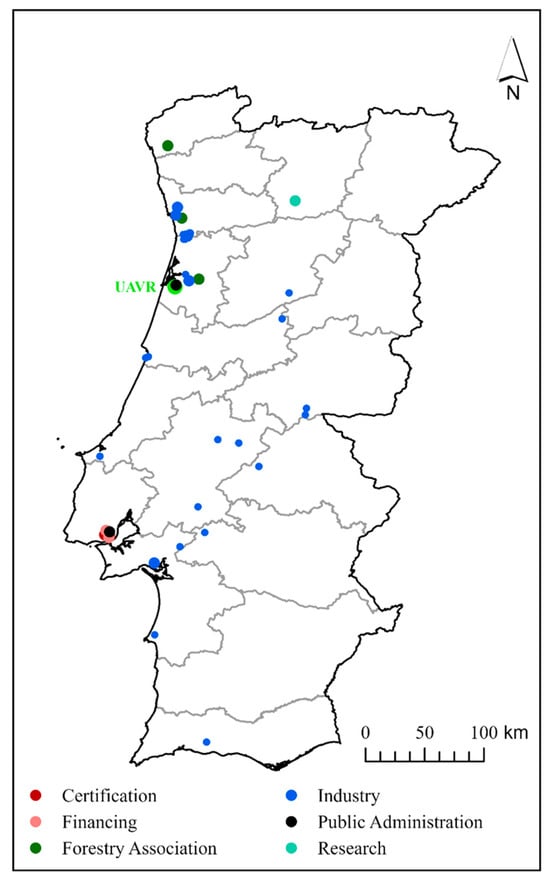

The workshop was attended by fifteen Portuguese entities, representing six forest sectors (Figure 2 and Figure 3A). The geographical representation of the stakeholders highlights their distribution across Portugal, showing the involvement of stakeholders from various regions from the north to the south, both from coastal and inland areas.

Figure 2.

Geographical representation of the stakeholders present at the workshop. Larger dots correspond to headquarters while smaller dots correspond to branches. Map generated by the authors. Projection: WGS 1984. Administrative boundaries: Portuguese Agency for Administrative Modernization, available on www.dados.gov.pt. Locations: provided by stakeholders.

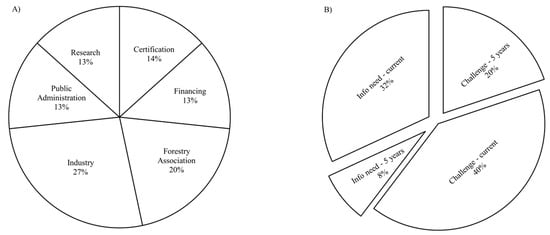

Figure 3.

(A) A percentage of entities present at the workshop per activity sector; (B) a percentage of mapped challenges and information needs per period.

Industry was the most represented sector, followed by Forest Associations. The least represented sector was Research (Figure 3A).

In total, 116 topics were mapped by the stakeholders individually during the first part of the workshop, 70 being challenges and 46 being information needs, and there were more challenges and information needs identified for the present than for the 5-year period (Figure 3B).

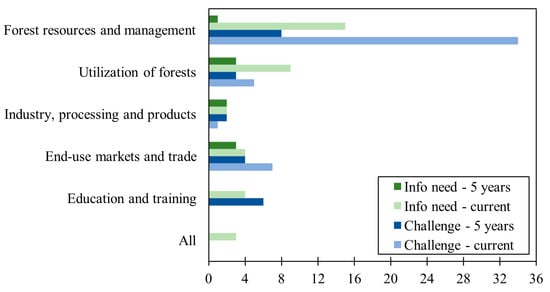

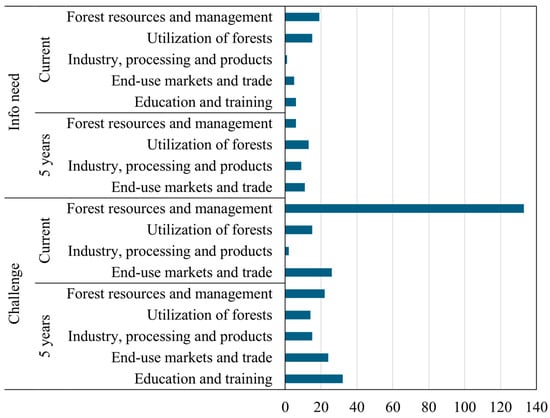

When grouping the identified topics per theme, forest resource management has the highest number of identified challenges and information needs, mostly in the short term, with a total of 58 topics identified. Utilization of forests and end-use markets and trade has a similar number of topics (20 and 18, respectively) with a high number of topics identified at present. The themes with fewer topics are industry, processing, and products. The education and training theme had six challenges for the 5-year period, mostly related to training, and four current information needs, mostly related to education. There were three topics identified by the stakeholders that fit all FWC themes, which were, therefore, grouped as “All” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of challenges and information needs identified per theme.

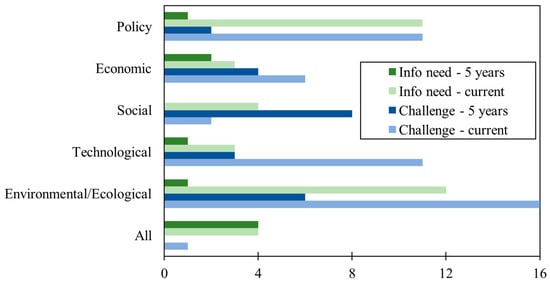

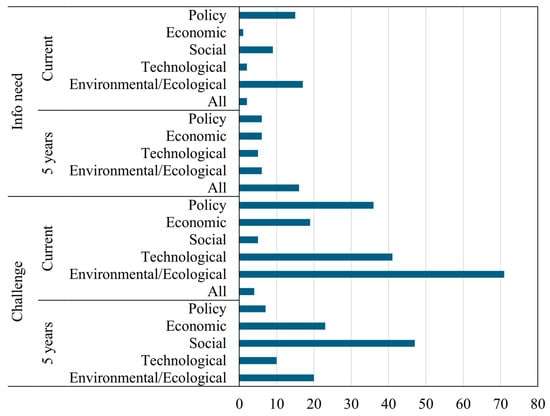

To contextualize the information gathered during the workshop, a PESTE approach was taken to group each topic according to each category—Policy, Economic, Social, Technological, and Environmental/Ecological. The analysis of PESTE categories (Figure 5) showed that the most relevant challenges and information needs were in Environmental/Ecological and Policy categories. Of the Environmental/Ecological topics, circa 80% were current challenges and information needs, with only 20% identified for the 5-year period. The only category with a higher number of topics for the 5-year vs. current was Social. Two PESTE categories, Economic and Technological, included a high number of topics in challenges. There were nine current information needs that fitted into “All” PESTE categories.

Figure 5.

Number of challenges and information needs identified by each PESTE category.

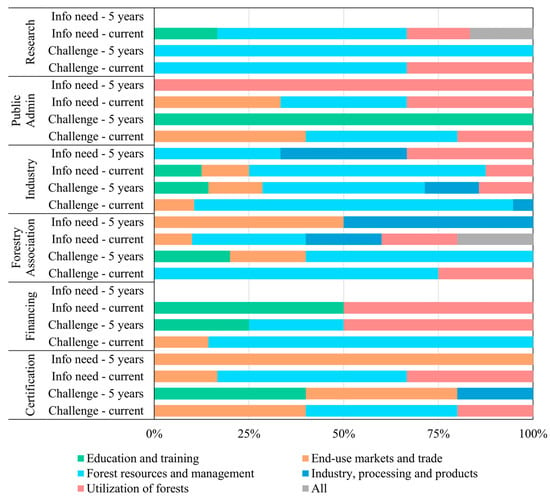

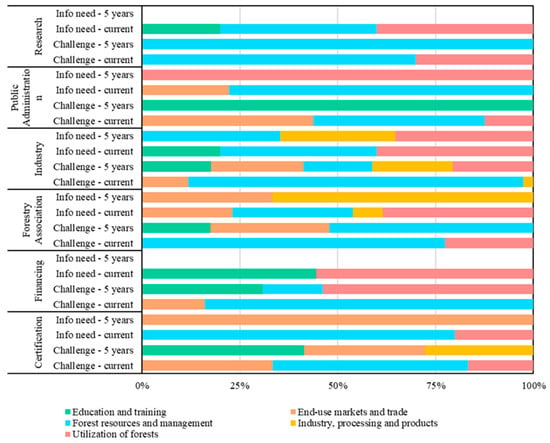

When analyzing the themes per activity sector and period, the Research and Industry sectors were mostly concerned with the forest and resource management, while the public administration ones were concerned with the utilization of forests. The Certification sector had a high relative contribution of topics in the end-use markets and trade theme; finally, the Forestry Association and Financing sectors have more balanced and overarching concerns, with a more evident relative contribution of industry, processes, and products (Figure 6). The education and training theme was identified in all activity sectors. While topics mentioned by the Public Administration, Industry, Forest Associations, and Certification fit in both time periods, Research and Financing entities did not identify information needs for the 5-year period.

Figure 6.

Distribution of themes identified per activity sector, typology, and time frame. Neither the Financing nor the Research entities identify information needs in 5 years.

If the same analysis of the PESTE categories is conducted but applied to different activity sectors, it is observed that the Certification entities are equality concerned with Policies, Social, and Environmental/Ecological categories; Financing and Research entities are more focused on Policy and Environmental/Ecological categories; and Forest Associations are concerned with Policy and Economic categories, Industry with Technological and Environmental/Ecological components, and Public Administration with Policy and Social categories (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of categories identified per activity sector, typology, and time frame. Neither the Financing nor the Research entities identify information needs in 5 years.

3.2. Challenges and Information Needs Prioritized by the Stakeholders

During the third part of the workshop, the stakeholders were invited to prioritize the top three topics identified individually in the initial part of the workshop and after a group discussion.

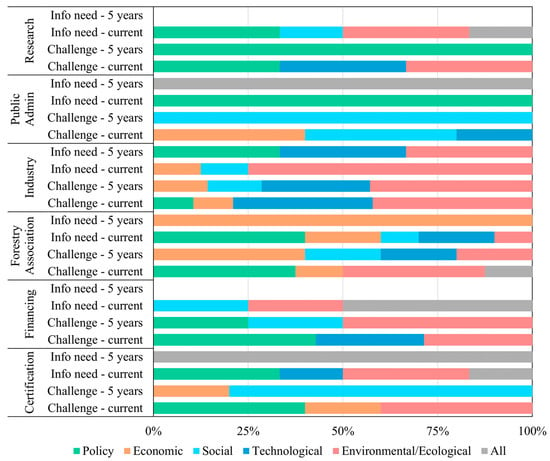

The forest resources and management topics stand out with the highest number of votes, with a total of 180 votes, with 133 being current challenges. It follows the end-use market and trade (66 votes), utilization of forests (57 votes), and education and training (38 votes). The least voted theme was industry, processing, and products (Figure 8). Looking for the PESTE categories (Figure 9), Environmental/Ecological was the most voted, with 114 votes, and Economy was the least voted, with 49 votes.

Figure 8.

Sum of votes per theme.

Figure 9.

A summary of votes per PESTE category.

Overall, the most voted topics were current challenges—176—and the least voted topics—39—were information needs in 5 years.

Considering the distribution of votes per theme and per entity sector (Figure 10), the same concern with forest and resource management as in the initial part of the workshop (Figure 6), was observed by the Research, Industry, and Certification sectors. The Public Administration, Financing organizations, and Forestry Associations voted more on forest and resource management-related topics, which is not aligned with their identified concerns in the utilization of forests, and the industry, processes, and products.

Figure 10.

A summary of votes in each theme per entity, typology, and time frame.

3.3. The Most Voted Topics

The top three prioritized topics in the challenges domain were “Biotic and abiotic risks” (Environmental/Ecological), “Valorization and qualification of the sector” (Social), and “Economic and fiscal stimulus to forest management” (Economic), the first being a current challenge and the last two categorized in a 5-year period.

The top three prioritized topics in the information needs domain were “Forest inventory, cadastral data, and legal restraints” (Environmental/Ecological), “Decision-making support systems for forest management” (Policy), and “National and sub-national climatic projections” (Environmental/Ecological), the first one being a current need and the other two categorized in the future 5-year time span.

4. Discussion

This study used a stakeholder participatory approach to identify and analyze the most pertinent needs and challenges impacting the Portuguese forest at the present and in 5 years. This distinction between challenges and information needs not only demonstrates the perception of existing obstacles but also allows for the planning of the required knowledge and resources needed to address them effectively. The 5-year period was initially chosen with the intention of aligning some of the most relevant needs and challenges with the upcoming national and European agendas and funding framework programs, allowing this knowledge to feed into relevant topic suggestions for development and funding [47]. One of the key aspects of the current work was the national and regional forest stakeholder-centered approach taken. Similar studies involving stakeholders have been conducted in Portugal and in many other European countries [38,48,49,50,51]. Most of these were designed to empower participants, democratize knowledge production, improve decision-making, and help bring about new environmental futures for scenario building and decision-making support [52,53]. Although they offer valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities facing national forest sectors, these initiatives are often thematic, asking for the stakeholders’ insights on specific problems and challenges [37], preconditioning their inputs. Studies in Portugal and Spain have been mainly focused on issues such as forest fires and the impact of climate change on the Mediterranean ecosystems [38,52]. In Finland, studies have explored sustainable forest management and the trade-off between biodiversity conservation and bioenergy production [51,54]. Similarly, research in France and Germany has addressed topics ranging from forest biodiversity conservation to the socio-economic benefits of forest ecosystems [55,56]. Our study design focused on an open participatory approach, asking for the stakeholders’ feedback and suggestions on their current and future challenges and information needs, without imposing thematic barriers and gathering all given inputs. This approach broadens the scope of the collected data, with 116 topics identified by the group covering aspects from public policies, funding, climate change mitigation, human resource trainings, industry bottlenecks, or end-users’ needs. The direct stakeholder engagement in identifying, understanding, and addressing the needs and challenges of the forest sector in Portugal was crucial to providing realistic feedback that reflects actual national forest problems and challenges. This participatory approach is aligned with previous studies, reinforcing the importance of integrated decision-making processes to effective management of natural resources [37,52]. Collectively, the stakeholders represented the major sub-sectors of activity within the forest sector, with a higher representation of the Industry and Forest Associations, as a means of having a good representation of the main forest species-related value chains of the sector: Pinus pinaster, Eucalyptus globulus, and Quercus suber [24]. The sample size of 15 participants, while limited, is justified by the qualitative nature of this study, enabling a deeper understanding of the perspectives of strategically selected stakeholders with key roles and responsibilities in Portugal’s forestry sector. As Patton [57] highlights, qualitative research prioritizes depth and richness of data over numerical generalization, with purposive sampling ensuring the inclusion of individuals whose expertise is essential to meeting the study’s objectives. However, the lack of representation of some specific stakeholders in the value chain, especially those related to social and tourism aspects, may be a limitation of the findings related to the challenges of the sector.

Considering the 116 identified topics, the stakeholders revealed more challenges than information needs, most of which focused on the present time. These results were mainly justified by the stakeholders with a greater number of difficulties and restrictions faced currently by the sector, along with the fact that a 5-year timeframe is too short when taking forest ecosystems development rates into account. Indeed, when we consider that trees take years to decades to reach maturity, meteorological patterns—considering, or not, climate change—vary yearly, influencing the conditions for tree growth, and that management decisions made today can take years to produce relevant outputs, a 5-year timeframe is short in forestry.

Additionally, the predominance of short-term concerns within this theme demonstrates a collective awareness of the need for immediate actions required to mitigate emergent risks faced by the sector. Overall, by comparing the needs and challenges identified with stakeholders in the present study with the National Smart Specialisation Strategy 2030 (NSSS 2030) [23], a comprehensive view emerges through the PESTE framework [44]. Politically, both the present work and the NSSS 2030 highlight the need for supportive policies and effective governance. In terms of the economy, there is an alignment on adequate funding mechanisms and investment in innovative projects, while at the social level, both prioritize stakeholder engagement, emphasizing community involvement and regional insights. In technology, there is a shared focus on the adaptation of innovative tools for better forest management. Environmentally, both works focus on conservation, climate change mitigation, carbon sequestration, and addressing challenges like wildfire prevention. While these points demonstrate substantial alignment, this study goes further by identifying additional needs and challenges, offering a more detailed and comprehensive approach to the forest sector.

Our results are aligned with the findings of Nummelin et al. [44], which addressed the international scientific forest sector research between January 2000 and December 2019, demonstrating that forest resource management was, and continues to be, a central point to the forest sector both at the national and international levels. In the specific case of Portugal, several public resources, scientific studies, and political guidelines focused on forest management have been developed [23,35,36], but their application to solve stakeholders’ related main concerns seems to remain insufficient. The topics of forest utilization, involving the use of forest resources for the production of wood, non-wood products, and other ecosystem services [44] and end-use markets and trade, including alterations in market segments, which are the catalysts for shifts throughout the entire forest value chain [44], also had significant interest, demonstrating an extensive understanding and concern by the stakeholders of the entire forest product value chain. Wood production and wood products remain some of the major forest outcomes, highly shaping the global forest sector [1].

The PESTE analysis revealed that, despite the focused forest approach, most needs and challenges are related to Environmental/Ecological and Policy categories, evidencing a clear transversal need to focus on strategies addressing these themes, some of which result from past inadequate policies, less established priorities, and land use planning both at the national and local levels [58]. Nevertheless, the Economic, Social and Technological categories were also significant to most of the stakeholders as the Portuguese forest sector contributes significantly to the national economy through the production of wood and non-wood products and related activities, such as tourism or sports and employment opportunities [25].

This deeper analysis of the overall needs and challenges presented by each stakeholder allowed for the identification of inherent biases related to the type of stakeholder, with those that play a certification/regulatory role being more focused on legal aspects to regulate the forest and territorial usage and those with a more commercial profile focusing more on economic and social aspects. It was also interesting to note that the environmental and climate-related topics were transversal to all stakeholder types. These same trends were observed in similar approaches in other sectors, such as food supply value chains [59] and carbon capture-related value chains [60]. The workshop also facilitated discussions on the role research and innovation play in advancing sustainable forestry practices in Portugal. Participants emphasized the importance of both private and public entities investing in scientific research, technological innovation, specific training, and knowledge exchange along the forest value chain to develop new solutions and open new opportunities in the forest sector. This includes research on climate change impacts, including ecosystem monitoring, biodiversity mapping and conservation tools development, forest ecosystem dynamics studies, and socio-economic studies of different forestry dimensions. These results demonstrate a strong alignment with recent studies conducted in the USA [61], Canada [62], and Europe [63], evidencing that the concerns and challenges faced by Portuguese stakeholders are very similar to those faced in other countries, although the forest sector may be very different. Such alignment not only reinforces the significance of these findings but also suggests that exchanging solutions and strategies may have valuable implications for addressing similar challenges across countries. Participants also highlighted the need for more interdisciplinary collaboration and the need for knowledge-sharing platforms to bridge the gap between scientific research and on-the-ground forest management practices.

Environmental/Ecological was the most voted PESTE category for both needs of information and identified challenges. Stakeholders indicated the lack of reliable and regional climate projections, abiotic and biotic risks, and the resilience of the forest as key concerning points in that category. Portuguese forest stakeholders lack accurate data and climate projections, crucial information to assess the precise impacts of climate change on the forest and formulate adequate adaptation management strategies [64]. Climate change is altering temperature and precipitation patterns, increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme events such as wildfires and prolonged droughts [64,65]. The workshop participants also highlighted significant concerns about the impacts of climate change on Portuguese forest ecosystems and their services and the lack of unified strategies and/or policies and incentives to mitigate and adapt to such changes [58,65]. There was a consensus among participants on the importance of addressing climate change challenges, not only related to forests directly but also by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing decarbonization, and how these could be adapted to the forestry services and related businesses. With adequate policies and incentives, such as carbon pricing (e.g., carbon taxes and emission trading) and funding through green bonds and public–private partnerships, which support sustainable practices and emission reduction projects, the forest industry has a good and sustainable potential to become carbon-negative [66,67], thus effectively contributing to climate change mitigation.

Portugal has experienced an escalation in biotic (e.g., pests and diseases) and abiotic (e.g., wildfires and drought) stresses in recent years, mostly derived from climate changes felt intensely at a regional scale and less sustainable management options [64,65,68]. The proliferation of pests and diseases has been growing in number and impact, posing serious risks to forest health and resilience [68]. The increasing frequency and severity of wildfires, along with the more recurrent and long drought periods, have been greatly impacting forest productivity and the associated ecosystem services, biodiversity, and social infrastructures and human lives not only in Portugal [10,11]. In Southern Europe, wildfires consistently reduce the annual regional gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate by 0.11 to 0.18% [69]. So, a progressive reduction in forest productivity, exacerbated by extreme drought conditions and elevated fire risks, is already contributing to increased tree mortality rates and the subsequent conversion of forested areas into other types of vegetative and land uses [70]. Although climate change is a worldwide concern, its main effects and impacts may vary between bioclimatic regions [65,70,71,72]. Countries located in the Mediterranean biogeographical region, such as Spain, Italy, and Greece, have been experiencing the same climate change effects and vulnerability to natural disasters due to their similar climatic conditions, ecological plant species, and forest coverage [7,69,70]. Scientific and technical knowledge associated with effective territorial planning and more suitable public incentives to sustainable forest and natural resource management at the landscape level are crucial to increasing forest resilience today and in the future [73,74]. In this context, forest inventorying and monitoring data are today more important than ever to track changes on forest dynamics in short periods, providing relevant information for accurate and effective forest management and planning, decision supporting actions, and more directed policies [13,14,75,76,77].

Several stakeholders mentioned the enormous impact of the lack of an updated cadastral map of the Portuguese forest territory. This is an old challenge, referred to often by the sector actors, mainly due to the current forest ownership model of Portugal and other countries, such as Spain and Italy [13,78]. In the particular case of Portugal, it is a fragmented ownership where private small owners have more than 90% of the total national forest territory [24,37]. BUPi (Balcão Único do Prédio) is a public program in Portugal that has effectively been updating land registration, covering already 140 municipalities and registering over 555,000 georeferenced descriptions [79]. Several European countries have initiatives like the Portuguese program BUPi for property registration. For example, the “Agenzia delle Entrate” manages the “Catasto” program in Italy [80], the “General Directorate of Public Finances” oversees the “Cadastre” system in France [81], and in Spain, the “Catastro” system is maintained by the “Directorate General for Cadastre” [82]. These programs allow for the maintenance of detailed land and property records. Nevertheless, to fully overcome the Portuguese cadastral issues, it is essential to integrate the remaining municipalities into BUPi, accurately georeference all properties, maintain and update the system, and enhance user engagement [79]. This raises difficulties not only for maintaining an up-to-date record and reflecting transactions but also making forest management and, particularly, fire risk management an extremely complex issue. Fragmentation of the territory and regulatory complexity present great [83] obstacles to effective forest governance and land management. Fragmented land ownership patterns, characterized by small-scale parcels and absentee landowners, hinder coordinated conservation efforts and sustainable land use planning. Additionally, the forest sector suffers from a lack of interaction between forest owners and the political authorities and additional legal constraints affecting forest planning and management, not due to the lack of policy tools but to their implementation and complexity [83]. Moreover, the lack of political and legal support for investments in the forest limits the development of innovative projects and the attraction of investments needed to promote the sustainability and resilience of the forest sector. Many other European countries, including Spain, Greece, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Latvia, face similar challenges [13]. Initiatives aimed at improving wildfire prevention and implementing advanced forestry technologies often struggle to secure funding and regulatory approval, while fragmented policies and inconsistent enforcement further deter potential investors from committing to long-term projects in the Portuguese forestry sector [84]. Streamlining administrative procedures and harmonizing regulatory frameworks with European Union standards can enhance governance effectiveness and facilitate cross-sectoral collaboration [85]. Addressing rural depopulation and promoting sustainable land stewardship among local communities are critical aspects of political engagement. Encouraging land consolidation initiatives and supporting agroforestry practices can revitalize rural economies and mitigate land abandonment [86]. Furthermore, enhancing access to technical assistance and financial resources for forest owners and managers is essential for empowering public initiatives and fostering social inclusivity [87].

The economic viability of the Portuguese forest sector faces difficult obstacles. Fiscal incentives are essential to stimulating investment in sustainable forest management practices and promoting the transition towards a low-carbon economy [73]. Market volatility, compounded by global supply chain disruptions and fluctuating demand for timber products, underscores the need for diversification and resilience within the forest sector [7]. Investing in value-added wood products and non-timber forest resources can mitigate reliance on volatile commodity markets, fostering economic and social stability [1,12,88,89]. Moreover, the establishment of innovative payment schemes for ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration and hydrologic cycle regulation, can provide additional financial support for forest protection and conservation efforts [90,91,92].

Concerns from social and technological PESTE categories were also highlighted by the stakeholders as structural to the sector. Shifting societal perceptions and fostering a culture of stewardship through effective communication strategies are vital to overcoming social challenges within the forest sector, such as the fragmentation of the property, depopulation, and the high number of small private forest ownership and land abandonment [83,84,93,94]. Valorizing the multifunctional role of forests as providers of ecosystem services, recreational spaces, and cultural heritage sites can promote public support for sustainable forest management practices [14,25]. Professionalization and capacity building within the forest sector are critical for enhancing productivity, innovation, and competitiveness. The mentioned training needs reflected the urgency to review current education curricula and training paths as well as the need to foster novel technical skills training suitable for the current and upcoming challenges related to new technologies and innovations in the forestry sector. While this topic was highlighted by the stakeholders as a major challenge in Portugal, other findings have reported a similar situation in other countries [95,96]. These studies suggested that current forestry education models are not prepared to adapt to the rapid transformations of the sector driven by the advances in new technologies [95,96]. Highly related to professionalization is the technological innovation of the sector, which holds immense potential for transforming forest management practices and enhancing environmental sustainability [1]. Leveraging advances, and concomitant training, in remote sensing, and geographic information systems (GIS) can facilitate data-driven decision-making and optimize resource allocation [1,23,97,98]. Precision forestry techniques, such as LiDAR-based forest inventory and monitoring, enable precise spatial analysis and management interventions, maximizing forest productivity and resilience [23]. These challenges and needs are transversal to regional, national, and European forest sectors and pose new opportunities not only for education and training but also for innovation and technology development in this basilar sector.

This work highlights the interconnectedness of forestry challenges and information needs across not only the forest stakeholders from different sectors but also different themes and categories. Most of the identified issues are highly complex, requiring a transdisciplinary approach to effectively address them, a close collaboration between national and international actors of the forest sector, and suitable funding opportunities [99]. Although each country must tailor its own forestry policies and practices to its unique forest context and framework, there are overarching principles and approaches that can guide sustainable forest management at the European level [100,101] and globally [102]. There is value in learning from the experiences and best practices of other countries, particularly those facing similar challenges or with successful forestry management strategies in place, such as those from the Mediterranean region with similar environmental and social contexts [22,38,45].

Some identified topics indicate that a gap exists between the knowledge generated in academia and its practical application, which ultimately can limit the progress and effectiveness of forestry practices. Since scientific research produced in academia is mostly published in academic journals, written in technical English, the information is not readily accessible to the stakeholders. Even though stakeholders in Portugal tend to trust the knowledge generated in universities, it might not be easy to extrapolate results of experiments run in (semi-)controlled environments to their reality and their species of interest. Hence, to foster forestry practices, stakeholders and academia (perhaps also including local communities) should jointly invest more in knowledge transfer platforms or working groups, which could, for example, develop toolboxes that summarize findings and provide guidelines, organize formative workshops and courses, communicate science in plain language and infographics, and promote ongoing collaborations between sectors [authors note].

The integration of national and European policy perspectives provided further insights into the regulatory frameworks and institutional arrangements governing forest management. European policies such as the EU Forest Strategy [103], LULUCF [19] and the Common Agricultural Policy play a crucial role in shaping national forest policies and practices, highlighting the interconnectedness of regional and global efforts to address forest-related challenges [12,13]. However, the national funding and incentive strategies for a decarbonized and sustainable forestry are lagging the speed of development needed by the active forestry sector and are not fully aligned with the expected EU Goals [104]. Adjusted financial and economic incentive mechanisms for reaching a net zero forest goal are urgently needed in many European countries, not only Portugal but also Spain, Greece, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Latvia [103]. Additionally, a targeted strategy for forest innovation drive would benefit the sector with ideas and new solutions on how to adapt and advance to a more profitable, yet sustainable, forest sector [69]. Although the existing innovation projects and initiatives are supporting the forest sector in Portugal [23], the country lacks a dedicated forest innovation accelerator. Programs like the MIT Portugal Program’s Building Global Innovators Accelerator [105] and Forest Europe’s Future Forest Accelerator [106] can help foster forest innovation by linking academia with industry and supporting startups in forestry. Similar initiatives are being pursued with success in other relevant Portuguese sectors, like Ocean and Blue economy with dedicated accelerators, ideation, and the development of an innovation ecosystem (e.g., BlueBio Value Accelerator [107], the Hub Azul project [108]).

5. Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this study allowed us to identify the main forestry needs and challenges envisioned by the Portuguese forestry sector interested parties, with the disclosure of 116 topics across the whole value chain. The findings highlight the predominance of immediate challenges over future needs, with environmental and policy-related issues—such as climate change mitigation, biotic and abiotic risks, and governance deficiencies—emerging as the most pressing. Additionally, economic incentives, professional valorization, and technological advancements were recognized as essential for sector resilience.

By organizing the results within the PESTE framework, this study provides a systematic stakeholder perspective on forestry, aligning with, but adding to, national strategies like NSSS 2030 or the National Strategy for Forests [23,36]. Unlike previous studies that focus on specific forestry issues [38,51,52,54,55,56], this research offers an integrated, bottom-up assessment that gathers concerns from different agents across the forest-related value chain. The 116 identified topics establish a robust ground for national policy guidelines, research agendas, and funding priorities. Based on the findings of this study, several recommendations for future research and policy decision-making are proposed: further research is needed to deepen our understanding of the impacts of climate change on forests. These shall constitute priorities at the national science and innovation funding strategies and be included in the design of dedicated forest funding and financing instruments. Policy initiatives may consider prioritizing the development and implementation of adaptive management strategies that enhance the resilience of forest ecosystems to climate change, wildfire, and other disturbances. Positive fiscal incentives aligned with the desired sustainable management practices and innovation incorporation into the sector can be designed and implemented. Capacity-building initiatives and specific training dedicated to innovative technologies and upcoming challenges should be implemented to enhance technical skills for the sector.

The following approach ensures its relevance beyond Portugal, offering insights applicable to other European forestry sectors facing similar socio-political and environmental pressures. By directly capturing the priorities of stakeholders, it strengthens participatory governance and evidence-based decision-making in sustainable forest management.

It is important to acknowledge the limitation of this study as the lack of representation of some specific stakeholders in the value chain, mainly related to social and tourism activities. While our findings provide valuable insights into key sectoral challenges, they do not represent an exhaustive assessment of all forestry-related perspectives in Portugal. Moreover, further research is needed to explore the nuances and complexities of forestry dynamics at local and regional scales.

Author Contributions

S.C.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, funding acquisition, and project management. H.V.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. M.A.: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft. D.L.: data curation, writing—original draft. A.L.: funding acquisition, project management, and writing—review and editing. B.R.F.O.: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization, funding acquisition, and project management. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by ModelEco (PTDC/ASP-SIL/3504/2020) http://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/ASP-SIL/3504/2020, funded by national funds (OE) through FCT/MCTES, by the support action (CSA) ERA Chair BESIDE project financed by the European Union’s Horizon Europe under grant agreement No 951389 (http://doi.org/10.3030/951389), by the FirEProd Project, http://doi.org/10.54499/PCIF/MOS/0071/2019, funded by FCT, through national funds and by RESTORE4CS funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement 101056782, (http://doi.org/10.3030/101056782). Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting authority.

Data Availability Statement

Statements are available in section “DUNAS repositório de dados de investigação” at https://dunas.ua.pt/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.48527/TMGKRF, https://doi.org/10.48527/TMGKRF, Dunas, V1.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM) by FCT/MCTES (UID Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e Mar (CESAM) + LA/P/0094/2020), through national funds.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO; UNEP. The State of the World’s Forests 2020; FAO, UNEP, Eds.; FAO and UNEP: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132419-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, E.; Lozano, S. Cross-Country Comparison of the Efficiency of the European Forest Sector and Second Stage DEA Approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 314, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontl, T.A.; Swanston, C.; Brandt, L.A.; Butler, P.R.; D’Amato, A.W.; Handler, S.D.; Janowiak, M.K.; Shannon, P.D. Adaptation Pathways: Ecoregion and Land Ownership Influences on Climate Adaptation Decision-Making in Forest Management. Clim. Chang. 2018, 146, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontl, T.A.; Janowiak, M.K.; Swanston, C.W.; Daley, J.; Handler, S.; Cornett, M.; Hagenbuch, S.; Handrick, C.; Mccarthy, L.; Patch, N. Forest Management for Carbon Sequestration and Climate Adaptation. J. For. 2020, 118, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhling, K.; Todeschini, M.F.M. The Forest Sector in the 2030 EU Climate Policy Framework: Looking Back to Assess Its Future. J. Eur. Environ. Plan. Law 2021, 18, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, L. The Role of Science in Forest Policy–Experiences by EFI. Policy Econ. 2019, 105, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pra, A.; Masiero, M.; Barreiro, S.; Tomé, M.; Martínez de Arano, I.; Orradre, G.; Onaindia, A.; Brotto, L.; Pettenella, D. Forest Plantations in Southwestern Europe: A Comparative Trend Analysis on Investment Returns, Markets and Policies. Policy Econ. 2019, 109, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancioiu, P.; Nita, M.; Lazăr, G. Forestland Connectivity in Romania—Implications for Policy and Management. Land. Use Policy 2018, 76, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekroos, A. Forests and the Environment—Legislation and Policy of the EU. Eur. Energy Environ. Law. Rev. 2005, 14, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P.G.; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying Drivers of Global Forest Loss. Science (1979) 2018, 361, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevedello, J.A.; Winck, G.R.; Weber, M.M.; Nichols, E.; Sinervo, B. Impacts of Forestation and Deforestation on Local Temperature across the Globe. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020—Main Report, 1st ed.; FAO, Ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132974-0. [Google Scholar]

- FOREST EUROPE. State of Europe’s Forests 2020; FOREST EUROPE: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Freer-Smith, P.; Muys, B.; Bozzano, M.; Drössler, L.; Farrelly, N.; Jactel, H.; Korhonen, J.; Minotta, G.; Nijnik, M.; Orazio, C. Plantation Forests in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the Making Available on the Union Market and the Export from the Union of Certain Commodities and Products Associated with Deforestation and Forest Degradation and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010 (Text with EEA Relevance); European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Climate Action. The Monitoring and Reporting Regulation—General Guidance for ETS2 Regulated Entities; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Romppanen, S. The LULUCF Regulation: The New Role of Land and Forests in the EU Climate and Policy Framework. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law. 2020, 38, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, C.; Henriot, C. Protecting Forests from Conversion: The Essential Role of Supply-Side National Laws 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334371135_Protecting_Forests_From_Conversion_The_Essential_Role_of_Supply-Side_National_Laws (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Commission Consolidated Text: Regulation (EU) 2018/841 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on the Inclusion of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry in the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework, and Amending Regulation (EU) No 525/2013 and Decision No 529/2013/EU (Text with EEA Relevance)Text with EEA Relevance; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- European Commission. Factsheet—The European Green Deal—Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Targets; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Environment. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Eu Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Environment. Proposal for a Regulation of The European Parliament and of The Council on Nature Restoration; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ANI, National Innovation Agency. National Smart Specialisation Strategy 2030; ANI: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ICNF, Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests. 6o Inventário Florestal Nacional 6—2015; ICNF: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tomé, M.; Almeida, M.H.; Barreiro, S.; Branco, M.R.; Deus, E.; Pinto, G.; Silva, J.S.; Soares, P.; Rodríguez-Soalleiro, R. Opportunities and Challenges of Eucalyptus Plantations in Europe: The Iberian Peninsula Experience. Eur. J. Res. 2021, 140, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedelty, M. Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere. Environ. Commun. 2015, 9, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surová, D.; Surový, P.; de Almeida Ribeiro, N.; Pinto-Correia, T. Integrating Differentiated Landscape Preferences in a Decision Support Model for the Multifunctional Management of the Montado. Agrofor. Syst. 2011, 82, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acácio, V.; Dias, F.S.; Catry, F.X.; Bugalho, M.N.; Moreira, F. Canopy Cover Loss of Mediterranean Oak Woodlands: Long-Term Effects of Management and Climate. Ecosystems 2021, 24, 1775–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Cerveira, A.; Kašpar, J.; Marušák, R.; Fonseca, T.F. Forest Management of Pinus Pinaster Ait. In Unbalanced Forest Structures Arising from Disturbances—A Framework Proposal of Decision Support Systems (Dss). Forests 2021, 12, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; Corticeiro, S.; Maia, P. Maritime Pine Natural Regeneration in Coastal Central Portugal: Effects of the Understory Composition. For. Syst. 2022, 31, eSC06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Huidobro, G.; Lopes, L.F.; Ganteaume, A.; Ascoli, D.; Colaco, C.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Giannaros, T.M.; Gazzard, R.; Boustras, G.; et al. A Global Outlook on Increasing Wildfire Risk: Current Policy Situation and Future Pathways. Trees For. People 2023, 14, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.; Colaço, M.C.; Fernandes, P.M.; Sequeira, A.C. Remains of Traditional Fire Use in Portugal: A Historical Analysis. Trees For. People 2023, 14, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guisuraga, J.M.; Fernandes, P.M. Prescribed Burning Mitigates the Severity of Subsequent Wildfires in Mediterranean Shrublands. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, B.M.; Reis, E.; Vale, M.J.; Reis, R. Modelling the Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Portugal: A Multi-Scale and Multi-Temporal Approach. Finisterra 2018, 53, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA, Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente. National Forestry Accounting Plan Portugal 2021—2025; APA: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Estratégia Nacional Para as Florestas (ENF)—Resolução Do Conselho de Ministros n.o 6-B/2015, de 4 de Fevereiro; Presidency of the Council of Ministers: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, S.; Coelho, C.; Ribeiro, C.; Marsh, G. Sustainable Forest Management in Portugal: Transition from Global Policies to Local Participatory Strategies. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S.; Coelho, C.; Ribeiro, C.; Liniger, H.; Schwilch, G.; Figueiredo, E.; Bachmann, F. How Much Management Is Enough? Stakeholder Views on Forest Management in Fire-Prone Areas in Central Portugal. Policy Econ. 2015, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781134204304. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, C. Metodologia de Investigação Em Ciências Sociais e Humanas: Teoria e Prática; 2a.; Leya: Almedina, Spain, 2013; ISBN 978-972-40-5137-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Investigação Qualitativa Em Educação; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 1994; ISBN 972-0-34112-2. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, J. Manual de Investigação Qualitativa Em Educação; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014; ISBN 9789892608792. [Google Scholar]

- Nummelin, T.; Hänninen, R.; Kniivilä, M. Exploring Forest Sector Research Subjects and Trends from 2000 to 2019 Using Topic Modeling. Curr. For. Rep. 2021, 7, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenny, S.; Brannan, J.; Brannan, G. Qualitative Study; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Devers, K. How Will We Know “Good” Qualitative Research When We See It? Beginning the Dialogue in Health Services Research. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 34, 1153–1188. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/695 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 April 2021 Establishing Horizon Europe—the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, Laying down Its Rules for Participation and Dissemination, and Repealing Regulations (EU) No 1290/2013 and (EU) No 1291/2013 (Text with EEA Relevance); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Balteiro, L.; de Jalón, S.G. Certifying Forests to Achieve Sustainability in Industrial Plantations: Opinions of Stakeholders in Spain. Forests 2017, 8, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Giacovelli, G.; Pastorella, F. Stakeholders’ Opinions and Expectations for the Forestbased Sector: A Regional Case Study in Italy. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C. Sustainable Forest Management, Pecuniary Externalities and Invisible Stakeholders. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haatanen, A.; den Herder, M.; Leskinen, P.; Lindner, M.; Kurttila, M.; Salminen, O. Stakeholder Engagement in Scenario Development Process—Bioenergy Production and Biodiversity Conservation in Eastern Finland. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tàbara, D.; Saurí, D.; Cerdan, R. Forest Fire Risk Management and Public Participation in Changing Socioenvironmental Conditions: A Case Study in a Mediterranean Region. Risk Anal. 2003, 23, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreteau, O.; Bots, P.; Daniell, K.; Etienne, M.; Perez, P.; Barnaud, C.; Bazile, D.; Becu, N.; Castella, J.-C.; Daré, W.; et al. Participatory Approaches. In Simulating Social Complexity: A Handbook; Edmonds, B., Meyer, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 197–234. ISBN 978-3-540-93813-2. [Google Scholar]

- den Herder, M.; Kurttila, M.; Leskinen, P.; Lindner, M.; Haatanen, A.; Sironen, S.; Salminen, O.; Juusti, V.; Holma, A. Is Enhanced Biodiversity Protection Conflicting with Ambitious Bioenergy Targets in Eastern Finland? J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 187, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, I.; Rösch, C.; Saha, S. Converting Monospecific into Mixed Forests: Stakeholders’ Views on Ecosystem Services in the Black Forest Region. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Pinta, F.; Negny, S.; Montastruc, L. Importing Participatory Practices of the Socio-Environmental Systems Community to the Process System Engineering Community: An Application to Supply Chain. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 155, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, J.S.T.; Dias, L.F.; Kok, K.; van Vuuren, D.; Soares, P.M.M.; Santos, F.D.; Azevedo, J.C. Increased Policy Ambition Is Needed to Avoid the Effects of Climate Change and Reach Carbon Removal Targets in Portugal. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2024, 24, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattas, K.; Tsakiridou, E.; Karelakis, C.; Lazaridou, D.; Gorton, M.; Filipović, J.; Hubbard, C.; Saidi, M.; Stojkovic, D.; Tocco, B.; et al. Strengthening the Sustainability of European Food Chains through Quality and Procurement Policies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Nieto, J.; García-Meneses, P.M. A Stakeholder-Centred Narrative Exploration on Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage: A Systems Thinking and Participatory Approach. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 113, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homyack, J.; Sucre, E.; Magalska, L.; Fox, T. Research and Innovation in the Private Forestry Sector: Past Successes and Future Opportunities. J. For. 2022, 120, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, N.L.; Wyatt, S. The Design and Management of Multi-Stakeholder Research Networks to Maximize Knowledge Mobilization and Innovation Opportunities in the Forest Sector. Policy Econ. 2015, 61, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tret’yakov, A.; Ivanova, A.; Burmistrov, A. Priorities of Research Programs of European Universities in the Field of Forestry. In Proceedings of the Materials of the International Scientific and Practical Conference Green Economy: “Iforest”, FSBE Institution of Higher Education Voronezh State University of Forestry and Technologies Named after G.F. Morozov, Voronezh, Russia, 17 February 2022; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, L.; Álvarez-González, J.; Alberdi, I.; Silva, V.; Rocha, M.; Rego, F.C. Analysis of the Occurrence of Wildfires in the Iberian Peninsula Based on Harmonised Data from National Forest Inventories. Ann. Sci. 2019, 76, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. Portugal Facing Climate Change: Deep Problems, Sluggish Responses, But Hopeful Prospects. In Climate Change and the Future of Europe: Views from the Capitals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lipiäinen, S.; Sermyagina, E.; Kuparinen, K.; Vakkilainen, E. Future of Forest Industry in Carbon-Neutral Reality: Finnish and Swedish Visions. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 2588–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Midkiff, D.; Yin, R.; Zhang, H. Carbon Finance and Funding for Forest Sector Climate Solutions: A Review and Synthesis of the Principles, Policies, and Practices. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1309885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccoli, M.; Gallego, D.; Branco, M.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Corley, J.; Coyle, D.R.; Hurley, B.P.; Jactel, H.; Lakatos, F.; Lantschner, V.; et al. A First Worldwide Multispecies Survey of Invasive Mediterranean Pine Bark Beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae, Scolytinae). Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 1785–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.; Hebermehl, W.; Grossmann, C.M.; Loft, L.; Mann, C.; Hernández-Morcillo, M. Innovations for Securing Forest Ecosystem Service Provision in Europe—A Systematic Literature Review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 52, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Fitzgerald, J.B.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Reyer, C.; Delzon, S.; van der Maaten, E.; Schelhaas, M.-J.; Lasch, P.; Eggers, J.; van der Maaten-Theunissen, M.; et al. Climate Change and European Forests: What Do We Know, What Are the Uncertainties, and What Are the Implications for Forest Management? J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, D. Forests and Climate Change—Background Analytical Study; United Nations Forum on Forests: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppi, P.E.; Stål, G.; Arnesson-Ceder, L.; Hallberg Sramek, I.; Hoen, H.F.; Svensson, A.; Wernick, I.K.; Högberg, P.; Lundmark, T.; Nordin, A. Managing Existing Forests Can Mitigate Climate Change. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 513, 120186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsenty, A.; Salau, S. Fiscal Incentives for Improved Forest Management and Deforestation-Free Agricultural Commodities in Central and West Africa. Int. For. Rev. 2023, 25, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górriz Mifsud, E.; Bugalho, M.; Valbuena, P.; Corradini, G. Financial Incentives and Tools for Mediterranean Forests. In State of Mediterranean Forests 2018; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, F.; Somers, M.J.; Nieuwenhuis, M. PractiSFM—An Operational Multi-Resource Inventory Protocol for Sustainable Forest Management. In Sustainable Forestry: From Monitoring and Modelling to Knowledge Management and Policy Science; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Almendro, A.J.; Hidalgo, P.J.; Galán, R.; Carrasco, J.M.; López-Tirado, J. Assessment and Monitoring Protocols to Guarantee the Maintenance of Biodiversity in Certified Forests: A Case Study for FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) Forests in Southwestern Spain. Forests 2018, 9, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnus, J.-M.; Tome, M.; Orazio, C. Integrated Approach and Inventory System for the Evaluation of Sustainable Forest Management Indicators at Local Scales in Western European Regions. New Zealand J. Sci. 2005, 35, 246–265. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, F.; Laschi, A.; Zorzi, I.; Foderi, C.; Cenni, E.; Guadagnino, C.; Pinzani, G.; Ermini, F.; Bottalico, F.; Milazzo, G.; et al. Forest Sharing® as an Innovative Facility for Sustainable Forest Management of Fragmented Forest Properties: First Results of Its Implementation 2023. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/12/3/521 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- eBUPi, Estrutura de Missão para a Expansão do Sistema de Informação Cadastral Simplificado. Expansão Do Sistema de Informação Cadastral Simplificado; eBUPI: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia delle Entrate Cadastral Services. Available online: https://www.agenziaentrate.gov.it/portale/web/english/nse/services/cadastral-services (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Direction Générale des Finances Publiques Cadastre. Available online: https://www.cadastre.gouv.fr/scpc/accueil.do (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Directorate General for Cadastre. Available online: https://www.sedecatastro.gob.es/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Feliciano, D.; Alves, R.; Mendes, A.; Ribeiro, M.; Sottomayor, M. Forest Land Ownership Change in Portugal. COST Action FP1201 Forest Land Ownership Changes in Europe: Significance for Management and Policy (FACESMAP) Country Report; European Cooperation in Science and Technology: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, J. Forest Planning in Portugal. In Forest Context and Policies in Portugal: Present and Future Challenges; Reboredo, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 155–183. ISBN 978-3-319-08455-8. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission—Directorate-General for Structural Reform Support. Enhancing the European Administrative Space (ComPAct); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moodie, J.; Salle, E.; Laurent, I.; Pazos-Vidal, S. Empowering Rural Areas in Multi-Level Governance Processes. SHERPA Discussion Paper; Sustainable Hub to Engage into Rural Policies with Actors: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, A.B.; German, L.; Paumgarten, F.; Chikakula, M.; Barr, C.M.; Obidzinski, K.; van Noordwijk, M.; de Koning, R.; Purnomo, H.; Yatich, T.; et al. Sustainable Trade and Management of Forest Products and Services in the COMESA Region: An Issue Paper; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simula, M. The Economic Contribution of Forestry to Sustainable Development 1998. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42607194 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Montagné-Huck, C.; Niedzwiedz, A. The Definition and Use of Sustainable Forest Management Indicators from an Economic and Social Perspective. Rev. For. Fr. 2012, 64, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Garcia, J.; Wolff, H. Payment for Ecosystem Services from Forests. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbjornsen, H.; Wang, Y.; Ellison, D.; Ashcraft, C.; Atallah, S.; Jones, K.; Mayer, A.; Altamirano, M.; Yu, P. Multi-Targeted Payments for the Balanced Management of Hydrological and Other Forest Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 522, 120482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalho, M.; Silva, L. Promoting Sustainable Management of Cork Oak Landscapes through Payments for Ecosystem Services: The WWF Green Heart of Cork Project 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Miguel-Bugalho/publication/316859689_Promoting_sustainable_management_of_cork_oak_landscapes_through_payments_for_ecosystem_services_The_WWF_Green_Heart_of_Cork_project/links/591481fcaca27200fe4e8163/Promoting-sustainable-management-of-cork-oak-landscapes-through-payments-for-ecosystem-services-The-WWF-Green-Heart-of-Cork-project.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=.KoF1iwhMFZlnG3NLgzz2eFvpurxt54o4XXXHXMrkg0-1741776210-1.0.1.1-z2Bzf.BOacrD9j3kIpe5288vAno8yujyY94ZgrRjYjU (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Sténs, A.; Bjärstig, T.; Nordström, E.-M.; Sandström, C.; Fries, C.; Johansson, J. In the Eye of the Stakeholder: The Challenges of Governing Social Forest Values. Ambio 2016, 45, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunaratne, G. Effective Strategies for Communicating Environmental Management Policies to the Public. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367520099_Effective_Strategies_for_Communicating_Environmental_Management_Policies_to_the_Public (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Jegatheswaran, R.; Florin, I.; Hazirah, A.; Shukri, M.; Abdul Latib, S. Transforming Forest Education to Meet The Changing Demands For Professionals. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2018, 30, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.; Frosini de Barros Ferraz, S.; Sulbaran-Rangel, B. Trends in Brazil’s Forestry Education—Part 2: Mismatch between Training and Forest Sector Demands. Forests 2023, 14, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, P.; Sousa, J.P.; Alves, J. Toward Forests’ Sustainability and Multifunctionality: An Ecosystem Services-Based Project. In Handbook of Sustainability Science in the Future: Policies, Technologies and Education by 2050; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Doni, F., Salvia, A.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-3-030-68074-9. [Google Scholar]

- Heldt, L.; Beske-Janssen, P. Solutions from Space? A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective on the Growing Use of Satellite Technology for Managing Sustainability in Multi-Tier Supply Chains 2023. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925527323000968 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Begemann, A.; Roitsch, D.; Roux, J.-L.; Lovrić, M.; Azevedo-Ramos, C.; Börner, J.; Beeko, C.; Cashore, B.; Cerutti, P.; de Jong, W.; et al. Quo Vadis Global Forest Governance? A Transdisciplinary Delphi Study. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 123, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Gale, F.; Meidinger, E.; Newsom, D. Forest Certification in Developing and Transitioning Countries: Part of a Sustainable Future? Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesano, M.; Lasserre, B.; Masiero, M.; Tonti, D.; Marchetti, M. First Mapping of the Main High Conservation Value Forests (HCVFs) at National Scale: The Case of Italy. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All. Asp. Plant Biol. 2016, 150, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lallo, G.; Maesano, M.; Masiero, M.; Mugnozza, G.S.; Marchetti, M. Analyzing Strategies to Enhance Small and Low Intensity Managed Forests Certification in Europe Using SWOT-ANP. Small-Scale For. 2016, 15, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions New EU Forest Strategy for 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, M.; Batista, P.; Cordovil, F. The Portuguese Forest and the Common Agricultural Policy. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT Portugal Innovation. Available online: https://mitportugal.org/innovation (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Forest Europe Innovation in the Forest Sector: A Reality or Wishful Thinking? Available online: https://foresteurope.org/innovation-in-the-forest-sector-a-reality-or-wishful-thinking/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Oceano Azul Fundation BlueBio Value Accelerator. Available online: https://www.bluebiovalue.com/acceleration/acceleration-2024/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Fórum Oceano Hub Azul Project. Available online: https://hubazul.pt/en/landing-page-en (accessed on 9 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).