Abstract

Hydro–wind–solar integrated control systems face significant challenges related to multi-source heterogeneity, power fluctuations, and cross-timescale scheduling. Traditional management and control models struggle to meet the demands of constructing new power systems. As a core enabling technology, digital twins enhance system perception, prediction, and optimization through virtual–physical mapping and high-fidelity simulations. This paper reviews the core requirements for integrated hydro–wind–solar control systems, including unified management, multi-timescale coordination, and multi-source system integration. It systematically summarizes the layered architecture for digital twins in centralized control scenarios, as well as multi-source model construction and data fusion pathways. Additionally, the paper provides an in-depth review of multi-scale modeling, multi-physics coupling, and computational optimization in high-fidelity simulations. On this basis, potential future evolutionary trends in standardized modeling, intelligent dispatch, and secure, trustworthy operation are discussed. This study provides systematic guidance for constructing an efficient and reliable digital twin platform for hydro–wind–solar integrated control systems.

1. Introduction

As renewable energy is integrated into the power grid at high penetration levels, power system operations exhibit new characteristics, such as heightened volatility, reduced predictability, and increased regulatory complexity [1]. This has imposed higher requirements for operational monitoring, dispatch management, and fault response capabilities. As the core system for centralized management, unified dispatch, and remote control of multiple power stations [2], the central control center has increasingly become an indispensable technological foundation of the new power system. By enabling real-time monitoring of distributed power plants, unified control command issuance, and centralized fault coordination, the central control center significantly improves operation and maintenance efficiency and overall system performance [3].

To enhance the operational management and emergency response capabilities of centralized control systems, simulation platforms have emerged as a critical supporting tool and become a focal point for research and development [4,5]. Traditional centralized control simulation platforms are primarily based on theoretical instruction and simple simulation methods, failing to effectively replicate actual operational environments. This makes it difficult for operators to master operational procedures and accident handling strategies under highly realistic conditions [6]. Furthermore, the modeling capabilities, dynamic responsiveness, and simulation accuracy of existing systems still require improvement. Particularly under complex operational scenarios and sudden fault conditions, current platforms are inadequate in meeting the demands for rapid response and intelligent decision-making, thereby diminishing their effectiveness in practical operational support.

Against this backdrop, digital twin (DT) technology provides a novel approach for the construction and optimization of centralized control computer monitoring system simulation platforms. A digital twin refers to a virtual model of a physical object constructed using digital technologies [7]. By integrating historical information, real-time operational data, and algorithm-based models, it enables simulation, verification, prediction, and control across the full lifecycle of the physical system, enabling high-fidelity reconstruction of actual system operations in a virtual environment. Leveraging robust virtual–physical mapping, deep interactivity, and real-time responsiveness, digital twin technology enables dynamic simulation of system elements and operating conditions, while supporting real-time assessment, fault prediction, and strategy optimization [8,9]. This significantly enhances the intelligence level and practical application value of simulation platforms.

Since the centralized control centers need to integrate multiple heterogeneous clean energy stations, their system structure is highly complex and functionally integrated. Applying digital twin technology to the construction of simulation platforms for centralized control centers still faces numerous challenges. The current digital twin framework for centralized control systems is incomplete, lacking unified modeling standards and a comprehensive technical architecture. Additionally, inherent issues such as operational characteristic differences, modeling structure heterogeneity, and time-data asynchrony among wind, solar, and hydropower stations significantly increase the difficulty of cross-scenario system modeling and high-precision simulation. There is a pressing demand to develop a standardized high-fidelity model repository that enables collaborative modeling across multiple energy stations. Moreover, to meet the integrated demands of centralized control platforms in operational optimization, strategy validation, and simulation training, breakthroughs in key digital twin application technologies are still required. Mature methodologies are particularly lacking in core aspects such as real-time online simulation, adaptive calibration of critical parameters, and verification of scheduling strategy effectiveness.

As summarized in Table 1, existing review studies on digital twin technology mainly concentrate on power systems, integrated energy systems, energy supply systems, and smart microgrids. These works focus on topics such as digital twin concepts and definitions, general architectural frameworks, modeling and simulation methods, and application scenarios including operation optimization, monitoring, and maintenance. However, most of the existing reviews address power systems or energy systems in a broad sense or focus on specific subsystems such as microgrids. Systematic reviews that explicitly target hydro–wind–solar integrated centralized control systems are still limited. In particular, issues related to multi-energy coordinated control, multi-timescale operational characteristics, and the supporting role of high-fidelity simulation in centralized control contexts have not been fully examined.

Table 1.

Comparison of representative review papers on digital twin applications in energy systems.

To systematically address the above challenges, this paper organizes the relevant technologies following a requirement-driven and architecture-oriented logic. They are classified according to their functional roles within the hydro–wind–solar centralized control digital twin system, progressing from system requirements to architectural design, enabling technologies, and high-fidelity simulation capabilities. First, the paper systematically analyzes the functional requirements of hydro–wind–solar integrated centralized control systems, clarifying key technical demands for unified management, multi-timescale coordination, and multi-source integration. Second, a layered digital twin architecture tailored to centralized control scenarios is comprehensively reviewed, highlighting multi-source heterogeneous modeling, data perception fusion, and virtual–physical interaction mechanisms. Third, high-fidelity simulation technologies are investigated as a core enabler of trustworthy digital twins, focusing on multi-scale modeling, multi-physics coupling, and computational optimization. Finally, based on an extensive synthesis of recent research, future development directions for digital twin–enabled centralized control systems are identified, providing systematic guidance for building intelligent, reliable, and scalable hydro–wind–solar integrated control platforms.

Notably, the literature reviewed in this study was collected from authoritative academic databases, including Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and CNKI. The selected references span from 2004 to 2025, with a substantial proportion published within the past five years. The selection process emphasized relevance to hydro–wind–solar integrated control systems, digital twin architectures, multi-timescale modeling, multi-physics coupling, and high-fidelity simulation, with priority given to peer-reviewed journal articles and high-quality conference papers. These keywords reflect the core technical foundations, system integration characteristics, and operational features addressed in this review.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 analyzes the core requirements of wind–solar centralized control systems in the context of new power systems, focusing on integrated management of heterogeneous scenarios, multi-timescale coordinated scheduling, and multi-source system collaboration. Section 3 reviews the evolution of digital twin technology and discusses its layered architectural application in wind–solar centralized control systems. Section 4 presents the key enabling technologies for digital twin–based wind–solar centralized control, including multi-source heterogeneous scenario modeling and data-driven fusion and coordination mechanisms. Section 5 focuses on the application of high-fidelity simulation in digital twin–enabled wind–solar centralized control systems, covering multi-scale model construction and unified integration, multi-physics coupling and simulation accuracy enhancement, as well as computational optimization and real-time responsiveness. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Hydropower, Wind Power, and Solar Power Centralized Control System Requirements

China’s installed capacity of clean energy sources such as wind power, photovoltaic power, and hydropower is growing rapidly. Most of these new energy stations are in resource-abundant but remote regions, such as the northwest and southwest, where a “multi-station centralized” operation model is widely adopted to enhance operational efficiency and reduce labor costs. As the core hub for centralized monitoring, operation, maintenance, and dispatch of multiple stations, the central control center plays a critical role in power system operation. Its functions evolve from traditional visualization-based monitoring toward intelligent capabilities such as smart analysis, condition prediction, and decision support, forming a foundational platform for new power systems.

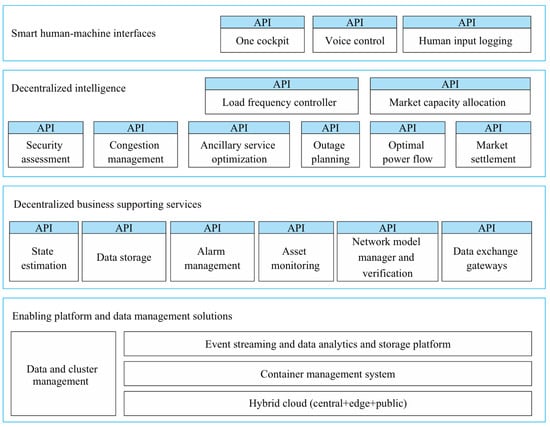

The central control center has evolved from single-source power management to coordinated regulation of multiple energy sources. This evolution requires not only real-time monitoring of different power stations but also comprehensive perception and predictive capabilities across power sources, grids, loads, and energy storage systems. As illustrated in Figure 1, the centralized control center adopts a four-layer architecture comprising platform and data, business services, intelligent applications, and human–machine interfaces. Built upon cross cloud–edge platform and data capabilities, this architecture enables system analysis, optimization, and control through decentralized business services and intelligent applications, while smart human–machine interfaces unify system states, real-time operational events, and decision-support functions to facilitate integrated cross-site management [15]. However, confronted with increasingly complex and dynamic operational environments, traditional SCADA systems and decision models struggle to support increasingly intricate dispatch decisions and system-level optimization tasks. There is an urgent need to introduce more intelligent, dynamic, and adaptive supporting technologies.

Figure 1.

Proposed enabling digital platform architecture featuring modular design and standardized API [15].

It is evident that the emerging demands of hydro–wind–solar centralized control systems primarily focus on three key aspects. First, significant differences in control logic and operational characteristics among hydropower, wind, and solar stations necessitate the establishment of a unified modeling and dispatch mechanism to achieve integrated management. Second, distinct differences in output characteristics and response times among different energy types require the development of a coordinated control system capable of accommodating multi-timescale operational characteristics ranging from seconds to hours. Third, fragmented system interfaces and inconsistent technical standards across various stations require centralized control systems to possess cross-platform model integration and operational fusion capabilities. To address these needs, it is essential to further explore the specific requirements of these three aspects, thereby enabling the more targeted construction of a real-time simulation platform for hydropower–wind–solar centralized control systems.

2.1. Integrated Management Requirements for Heterogeneous Field Stations

Significant differences exist among various types of power stations in terms of physical structure, control mechanisms, operational boundaries, and regulation responses, creating substantial obstacles for current centralized control systems in achieving unified access, coordinated scheduling, and strategic optimization. For example, wind farms exhibit strong nonlinear characteristics, with power output highly dependent on wind speed variations, while photovoltaic systems are significantly influenced by solar irradiance and temperature and lack inertia support capability. In contrast, hydropower stations provide excellent active power regulation, but their operation and scheduling are constrained by hydrological conditions, reservoir management, and upstream–downstream coordination [16]. The widely adopted “independent subsystem control” architecture is insufficient to support multi-energy coordination under the trend of integrated generation-grid-load-storage. As a result, system dispatch often remains static and segmented, lacking a holistic perspective and dynamic integration capabilities [17]. Consequently, establishing an integrated perception and collaborative control system for multi-source heterogeneous stations has become a critical direction for the structural upgrade of centralized control systems.

2.2. Multi-Timescale Collaborative Scheduling Requirements

Compared to the variability of wind and solar power, hydropower offers greater predictability and flexible dispatch capabilities, making it suitable for load tracking and reserve support from intraday to day-ahead timeframes. However, current centralized control systems generally lack unified modeling and control mechanisms to address these cross-timescale operational dynamics. As a result, dispatch strategies often struggle to balance real-time responsiveness with long-term economic efficiency, frequently leading to issues such as curtailed renewable energy and reduced system stability [18]. Moreover, multi-scale dynamic characteristics require synchronous mapping at the simulation level. Traditional scheduling systems lack the requisite modeling depth and simulation support capabilities, preventing prediction, control, and evaluation methods from aligning with the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of modern energy systems. Therefore, centralized control systems must overcome existing temporal granularity limitations and develop multi-timescale coordinated scheduling capabilities under unified modeling frameworks to achieve flexible coupling of generation, grid, load, and storage operations.

2.3. Multi-Source System Collaborative Integration Requirements

Most renewable energy stations are currently constructed, operated, maintained, and managed by different entities. Their hardware and software platforms, communication protocols, and operational logic vary significantly, leading to severe interface standardization issues for centralized control systems in data integration, model invocation, and functional adaptation. For instance, control systems from different manufacturers often support incompatible data structures, sampling frequencies, and response mechanisms. This necessitates extensive manual conversion and adaptation for data acquisition, compromising system scalability and operational stability. Moreover, fragmented and non-standardized model construction methods limit the reusability of models within simulation platforms and the capability for cross-system joint simulation, making it difficult to meet future goals of “multi-source integration and unified control” [19]. Therefore, the centralized control system urgently requires a framework with interoperability, standardized interface specifications, and unified model encapsulation mechanisms to support coordinated integration and efficient operation of multi-source energy stations. The requirements for digital twin modeling in hydro–wind–solar integrated control systems are summarized in Table 2. Beyond interface and model standardization, constructing a multi-timescale digital twin for hydro–wind–solar integrated systems faces distinct challenges: it must simultaneously capture the rapid second-to-minute fluctuations of wind and solar power and the slower minute-to-hour regulation dynamics of hydropower, requiring a delicate balance between high-fidelity simulation of fast transient processes and efficient long-term scheduling calculations, while also addressing the propagation of short-term uncertainties across longer timescales to ensure robust decision-making. To address these issues, targeted improvements include developing a hierarchical modeling framework that couples high-fidelity sub-models for fast timescales with simplified yet accurate models for slow timescales, deploying edge-cloud collaborative computing architectures to balance computational efficiency and simulation fidelity, and integrating a unified uncertainty quantification module to propagate short-term volatility into long-term scheduling strategies, thereby enabling more reliable multi-timescale coordinated control.

Table 2.

Core requirements for the integrated control system of hydropower, wind power, and solar power.

3. Application of Digital Twin Technology in Integrated Control Systems for Hydropower, Wind Power, and Solar Power

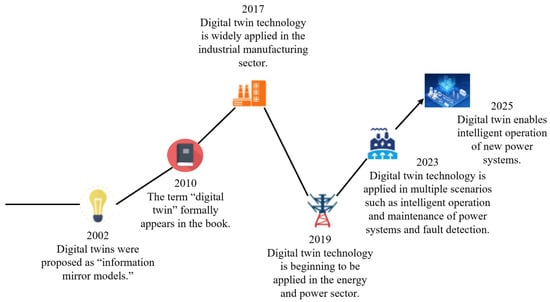

In 2002, Professor Grieves from the University of Michigan introduced the concept of digital twins, describing it as an “information mirror model” [20]. The expression “digital twin” was officially used for the first time in 2010 [21] and was defined in NASA’s Space Technology Roadmap as a process that integrates physical models, sensor data, and operational history. It integrates multi-disciplinary, multi-physical, multi-scale, and uncertain simulations to create a virtual representation of physical systems and capture their complete lifecycle [22]. A digital twin system generally consists of three parts: the physical object, its virtual model, and the data link connecting them. It achieves information synchronization and state mapping between the virtual and physical domains through multi-source, heterogeneous data-driven model updates [23,24].

3.1. The Evolution of Digital Twin Technology

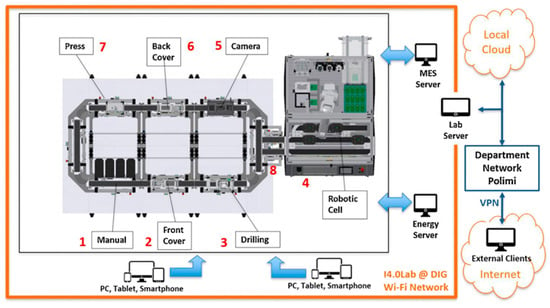

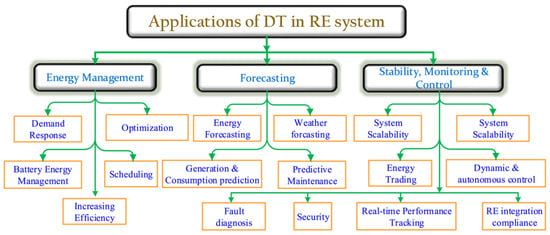

With ongoing progress in information technology, the Internet of Things, and computing capabilities, digital twin technology has evolved and matured [1], entering a rapid development phase after 2020. Its early applications were primarily concentrated in industrial manufacturing, demonstrating notable advantages in areas such as product design, process optimization, equipment operation and maintenance, and smart manufacturing [25]. Cimino et al. [26] present an Industry 4.0 laboratory production line, as illustrated in Figure 2. This system integrates a physical production system with a Manufacturing Execution System (MES) and an energy monitoring platform. The production line consists of multiple assembly stations and robotic units connected by an automated conveyor, enabling continuous process execution and real-time data acquisition through networked control and sensing modules. At the system level, the MES coordinates task dispatching and process control, while the energy monitoring system synchronously collects electrical signals such as current and power. The unified connectivity allows operational states, production information, and energy data to be continuously exchanged and synchronized. From a digital twin perspective, this architecture illustrates a basic physical–information coupling pattern based on real-time sensing, centralized management, and state synchronization, particularly in terms of multi-layer data integration and physical–cyber coordination. Shetwi et al. [27] systematically reviewed recent applications of digital twin technology in the renewable energy sector, as illustrated in Figure 3. They identified three core application domains: energy management, predictive analytics, and stability and monitoring control. Through hierarchical coordination, these form an integrated application framework covering the entire process—from battery management and fault diagnosis to renewable energy grid compliance. Zhang et al. [28] proposed a digital twin-driven smart manufacturing workshop that combines information computing technologies with low-carbon manufacturing. By leveraging the twin workshop to verify and optimize product processing solutions, this approach achieves the goals of energy saving and emission reduction in the workshop.

Figure 2.

Industrial 4.0 laboratory production line [26].

Figure 3.

Applications of DT in the renewable energy systems [27].

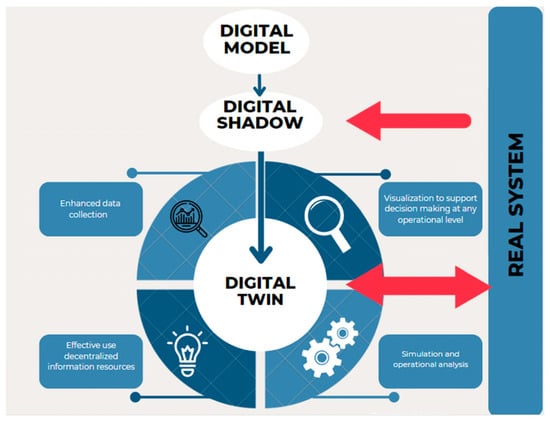

Subsequently, the application boundaries of digital twins have expanded further, gradually permeating complex system domains such as energy and power, transportation, and urban governance, becoming a crucial bridge connecting physical and digital realms [29,30]. Key milestones in digital twin technology are shown in Figure 4. Belik et al. [31] illustrate the relationships among digital models, digital shadows, and digital twins from an evolutionary perspective in Figure 5. They emphasize that digital twins enable data-driven simulation, state mapping, and decision support through bidirectional real-time interaction with physical systems, thereby supporting full lifecycle management of physical assets. Zhang et al. [32] developed an evaluation index system covering dimensions such as model fidelity, real-time performance, and service capability, providing a quantitative benchmark for technology implementation. The development of digital twin technology in the power system has been particularly rapid, finding applications across all segments including generation, transmission, transformation, and distribution [33,34,35]. It serves as a critical technological means for the comprehensive transformation from traditional power grids to modern power systems. Shen et al. [36], addressing the characteristics of power systems, further explained that digital twins must possess three key features: full-element mapping, real-time interaction, and dynamic simulation, highlighting their irreplaceable role in grid situational awareness. Bai et al. [37] proposed a “digital power grid” architecture, advocating for the use of twins to achieve coordinated regulation of generation-grid-load-storage. Xiang et al. [38] listed successful cases of digital twin applications in power grid operational scenarios such as power flow calculation and fault analysis.

Figure 4.

Milestones in the development of digital twin technology [10,20,21,25,29,30].

Figure 5.

Flowchart for the implementation of DT in the operation of DRESs [25].

To enhance the evaluability and implementability of digital twin system applications, Zhang et al. established a multi-dimensional evaluation framework encompassing model fidelity, real-time performance, and service capabilities, providing a reference standard for engineering practices [39]. Meanwhile, Zhang Lin emphasized a rational perspective on technological advances, arguing that modeling and simulation capabilities are fundamental to realizing digital twin value, while applications lacking modeling accuracy struggle to be effective in practice [40]. Overall, within the field of power system engineering, digital twin technology is undergoing a profound transformation from localized, static applications toward systematic, real-time integration. This technology significantly enhances the power system’s capabilities in perception, prediction, and decision-making, laying a solid technical foundation for building future intelligent energy infrastructure.

3.2. Application of Digital Twin in the Layered Architecture of Water–Wind–Solar Integrated Control Systems

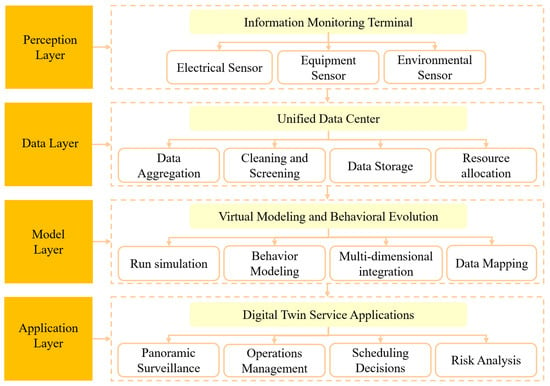

The design of the twin model’s architecture forms the foundational basis for the practical implementation of digital twin systems within centralized control systems. Its structural rationality directly determines the platform’s capabilities in multi-source data fusion, operational state restoration, strategy evaluation, and control simulation. In the context of integrated hydropower–wind–solar centralized control, the digital twins must achieve dynamic restoration of physical equipment operational states, behavioral modeling of control logic, and support multi-timescale operational simulation and optimization analysis. Consequently, current research commonly adopts layered and modular architectural frameworks to meet the collaborative modeling requirements for high coupling, multi-scale, and multi-role aspects within centralized control systems. Mainstream approaches predominantly follow a four-layer structure comprising perception layer, data layer, model layer, and application layer [41], as illustrated in Figure 6. Through the functional coupling of these layers, an efficient closed loop for system perception and intelligent management is achieved.

Figure 6.

Basic architecture of digital twin models.

- (1)

- The perception layer functions as the interface linking the digital twin with the physical system. Within a centralized control system, it is primarily responsible for collecting the operational status of multi-source power stations and aggregating edge-monitoring information. Its core task is to establish a multi-dimensional perception system encompassing key operational parameters of wind, solar, and hydropower equipment, thereby supporting the dynamic updating of backend models [33,42,43]. In recent years, miniaturized intelligent sensors, multi-physical integrated sensing terminals, and edge deployment technologies have enabled geographically distributed stations to achieve higher-precision and lower-latency data access. As a result, the real-time monitoring capability and system mapping synchronization of centralized control systems have been significantly enhanced.

- (2)

- The data layer fulfills a dual role of data-driven operation and operational assurance within the centralized control systems. It is responsible for the integration, processing, and scheduling of massive heterogeneous data, providing computational foundation and data support for model responses. Specific functions include data aggregation for high-concurrency station access, quality cleansing and feature extraction, storage management based on big data platforms, and computational resources allocation utilizing cloud–edge collaboration technologies [44,45]. In practical applications, the capabilities of this layer directly determine the response speed and intelligence level of the digital twin platform in handling rapid disturbances, abnormal events, and unforeseen operational conditions, making it the core hub for achieving intelligent simulation.

- (3)

- The model layer undertakes the tasks of virtual modeling and behavioral evolution for the digital twin entity, serving as the core medium for achieving unified modeling and dynamic simulation of wind, solar, and hydropower stations within the centralized control platform. Models must span multiple levels, including equipment, station, and system layers, and support the dynamic representation of operational processes across multiple timescales [46]. Common approaches include unified information modeling based on CIM, 3D geometric modeling, hierarchical encapsulation of system simulation models, and behavioral modeling algorithms based on operational data [47,48,49,50]. Through the support of this layer, the centralized control system can perform modeling, simulation, and control strategy validation for complex operational scenarios, providing a foundation of virtual–physical fusion for scheduling optimization.

- (4)

- The application layer serves as the functional output through which the digital twin serves the centralized control business, providing diversified support for typical scenarios such as operational management, strategy assistance, and risk analysis. By integrating simulation visualization, human–machine interaction interfaces, predictive warning modules, and dispatch decision support tools, this layer facilitates the evolution of the centralized control platform from a “monitoring-oriented” to a “decision-oriented” system [51,52]. Current research is also driving the expansion of the application layer into areas such as multi-role collaboration, business process integration, and security protection, thereby strengthening the system’s overall intelligence level and service capabilities.

In summary, the digital twin architecture centered on the “perception–model–data–application” framework has progressively established a closed-loop capability of virtual–physical interaction and intelligent evolution within centralized control systems. It has become a key enabler for enhancing the integrated perception, multi-scale simulation, and strategic coordination of hydropower–wind–solar multi-source systems. Future work is needed to reinforce real-time coordination mechanisms between layers, ensure data consistency, and enhance model elastic reconfiguration capabilities to improve system stability, scalability, and adaptive control capabilities.

4. Key Enabling Technologies for Digital Twin in Integrated Control of Hydropower, Wind Power, and Solar Power

4.1. Multi-Source Heterogeneous Field Station Model Construction

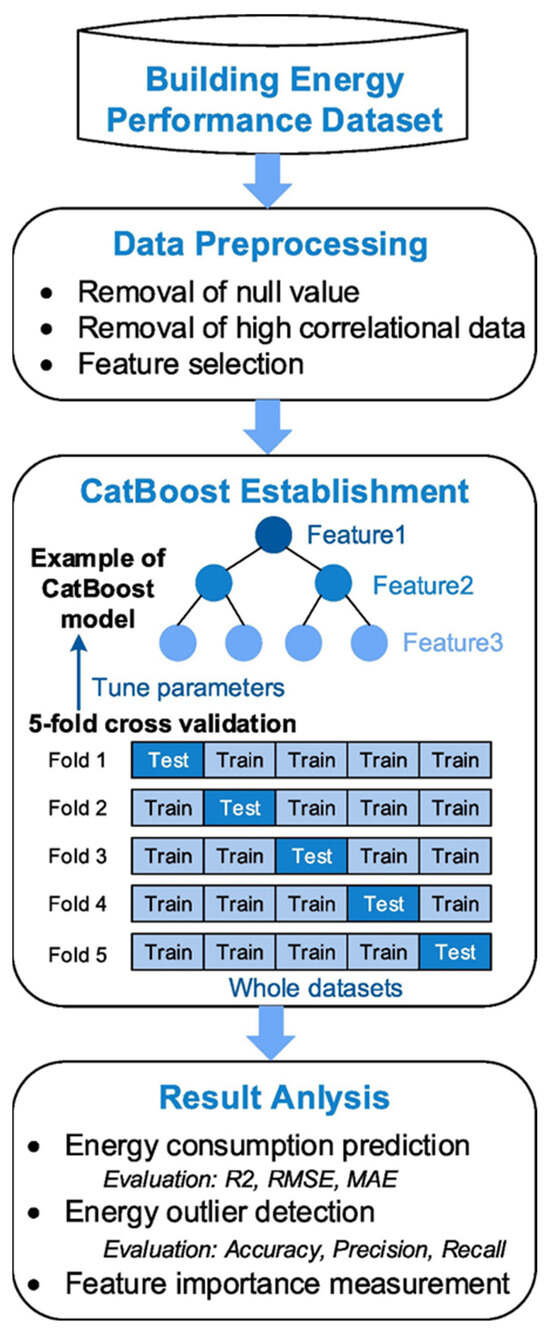

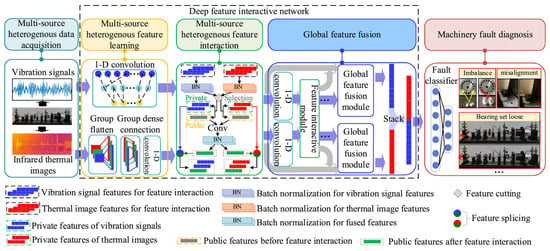

This is a complex framework composed of subsystems from diverse sources, where each subsystem exhibits distinct typological and structural characteristics. Its core feature lies in the diversity and heterogeneity of data, models, and operational mechanisms. By integrating and coordinating these multi-source heterogeneous elements, it achieves holistic system perception, unified modeling, and intelligent decision support. Multi-source heterogeneous modeling not only mitigates information silos between subsystems and promotes the sharing and interoperability of data resources but also provides essential support for achieving cross-domain, cross-level collaborative optimization and intelligent control. Figure 7 illustrates the workflow of the energy consumption prediction method proposed by Pan et al. [53]. Preprocessed multi-source heterogeneous data from buildings are input into a CatBoost model. The model’s parameters are optimized using 5-fold cross-validation, enabling accurate predictions of building energy consumption. Similarly, Miao et al. [54] developed a deep neural network model, DFINet, for interactive feature extraction from multi-source heterogeneous data to improve machinery fault diagnosis accuracy. As illustrated in Figure 8, multi-sensor data are first collected from the machine. Shallow and deep features extracted by different modules are fused via a global feature fusion module, and the fused output is then used for fault diagnosis.

Figure 7.

Workflow of the proposed energy prediction method [53].

Figure 8.

DFINet and its application flowchart for machinery fault diagnosis [54].

Achieving unified perception, coordinated control, and intelligent simulation of multi-source renewable energy stations, such as wind, solar, and hydropower, within centralized control systems relies on the digital twin model’s accurate virtual mapping of physical stations. The construction of multi-source models not only provides foundational support for scheduling optimization, situational awareness, and operational forecasting but also establishes the data and mechanism foundation for the centralized control center to achieve coordinated management and control across wide-area multi-station operations. A comparative analysis of the key elements for constructing digital twin models for multi-source heterogeneous stations is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of key elements for constructing digital twin models of multi-source heterogeneous field stations.

First, there are inherent differences in control mechanisms and operational behaviors among different energy types such as wind, solar, and hydropower. Accordingly, digital twin models need to be developed with a focus on their specific operational characteristics. Wind power system models need to reflect the driving effect of wind speed disturbances on power output and the dynamics of regulation [55]. Photovoltaic models need to accurately represent solar irradiance periodicity, battery array output, and power prediction procedures [56]. Hydropower models should cover multi-scale operational characteristics, including reservoir management, turbine unit control, and cascade regulation effects [57]. By constructing such differentiated models, digital twins effectively support the centralized control platform in simulating the operational behaviors of multi-source stations and facilitating optimization decision-making across heterogeneous energy systems.

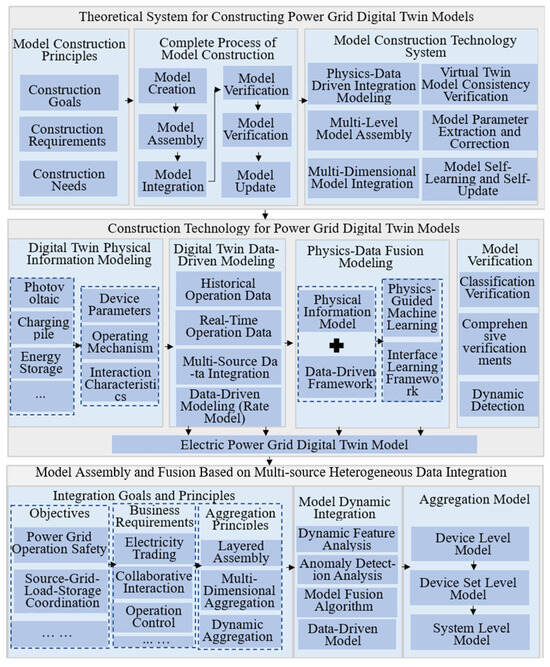

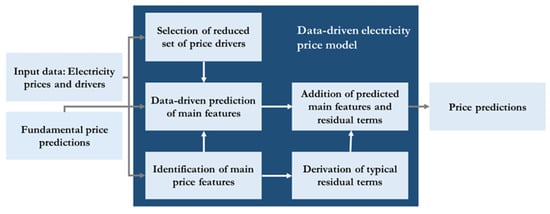

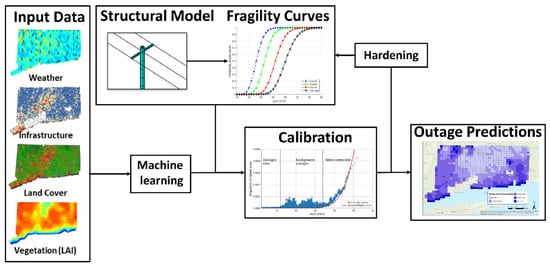

Second, the digital twin models of the centralized control systems require flexible modeling capabilities to accommodate diverse operational requirements. Current modeling methods mainly consist of physics-based, data-driven, and hybrid approaches. Physics-based modeling emphasizes the accurate representation of system structure and dynamic processes, making it particularly suitable for engineering-level simulation requirements [58]. Data-driven modeling leverages operational data from power stations, employing algorithms such as neural networks to capture and predict state evolution [59]. Hybrid modeling integrates physical knowledge with data-driven learning advantages, emerging as an effective approach to improve the accuracy and adaptability of the twin model [60]. As shown in Figure 9, Li et al. [61] proposed a digital twin model for power systems, whose overall architecture consists of three main components: a theoretical framework for model construction, key modeling technologies, and model assembly and integration based on multi-source heterogeneous data fusion. Specifically, the theoretical framework provides methodological guidance at the system level for the construction and evolution of digital twin models. The key modeling technologies support the detailed modeling of different physical entities and operational processes, while multi-source data fusion provides the data foundation for information exchange and coordinated operation among heterogeneous models. This technical route supports intelligent and secure operation of power grids. Gabrielli et al. [62] constructed a data-driven model for long-term electricity price prediction using Fourier analysis. This model decomposes electricity prices into two components: a fundamental evolution component described by the amplitude of the principal Fourier frequency, and a high-volatility component characterized by residual frequencies. The approach demonstrates high accuracy and stability in long-term market predictions, as illustrated in Figure 10. Hughes et al. [63] additionally incorporated the physical characteristics of infrastructure systems into data-driven models. By combining structural vulnerability characteristics of pole-and-line overhead distribution systems with machine learning techniques, they developed a power outage prediction model for the northeastern United States, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 9.

Digital twin model building technology roadmap [61].

Figure 10.

Overview of the structure of the data-driven model [62].

Figure 11.

HPD model architecture [63].

Within centralized control systems, the integrated application of these modeling approaches can specifically support diverse scenarios such as strategy evaluation, dispatch simulation, and fault early warning, thereby improving the system’s overall predictive, diagnostic, and decision-support capabilities.

Additionally, to achieve unified access and integrated operation of multi-site models, the digital twin platform within centralized control systems must establish a technical framework featuring standardized interfaces and a universal modeling language. Standards such as the Common Information Model (CIM) and Functional Model Interface (FMI) are widely adopted for model description and communication interoperability across heterogeneous systems [64]. Moreover, methodologies like Model-Driven Architecture (MDA) and Object-Oriented Modeling (OOM) further enhance model reusability and system integration capabilities [65]. These mechanisms ensure the integrated deployment and consistent management of diverse station models within the centralized control platform.

Overall, the application of digital twins in centralized control systems enables unified modeling and integrated management of multi-source renewable energy stations. Nonetheless, challenges remain in model consistency, platform adaptability, and standardized representation, necessitating coordinated advancement across modeling theory, system interfaces standardization, and model development toolchains to fully realize the potential of digital twins in multi-source energy integration and intelligent control.

4.2. Data Perception, Integration, and Driven Action

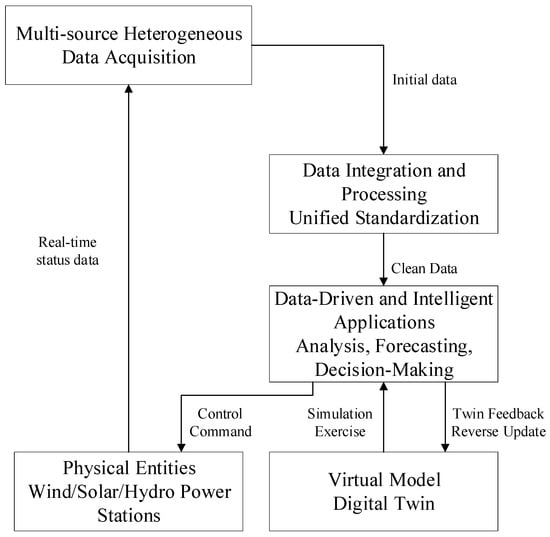

In the digital twin system of the centralized control center, precise data perception and intelligent decision-making are critical for achieving virtual–physical mapping, situational analysis, and decision support. As illustrated in Figure 12, multi-source heterogeneous data from power stations undergo comprehensive processing to enable effective system representation. Facing multiple stations, cross-regional operations, and diverse heterogeneous control objects, the digital twins must rely on an efficient and reliable data system to maintain continuous perception and real-time dynamic response capabilities for physical operational states.

Figure 12.

Multi-source heterogeneous field station data processing method.

To enhance the system’s comprehensive perception of operational environments and equipment status, multi-physical quantity fusion sensing technology is progressively introduced in centralized control scenarios. By integrating diverse sensor measurements, including temperature, humidity, voltage, current, wind speed, and solar radiation, it enables multi-dimensional, synchronous collection of complex operational conditions at hydro, wind, and solar power stations. Particularly in wide-area and distributed scenarios, the deployment of edge intelligent sensing nodes, low-power micro-sensors, and transparent sensing networks enhances the timeliness and flexibility of data acquisition. This significantly improves the system’s capability to monitor the operational dynamics of multi-source renewable energy stations.

Within the unified operation platform of the centralized control system, significant differences exist in format, semantics, and temporal characteristics among data from various sources. Without standardized processing mechanisms, this will constrain consistent model construction and efficient data flow transmission. To address this, research widely employs methods such as the Common Information Model (CIM), semantic ontologies, and graph databases to structure and semantically process data, enhancing its interoperability across models and platforms [66]. Furthermore, by leveraging multi-scale feature extraction and data fusion algorithms, the digital twin platform can achieve unified integration of status data from multiple stations, supporting collaborative modeling and prediction of the overall operational management at the centralized control level [67].

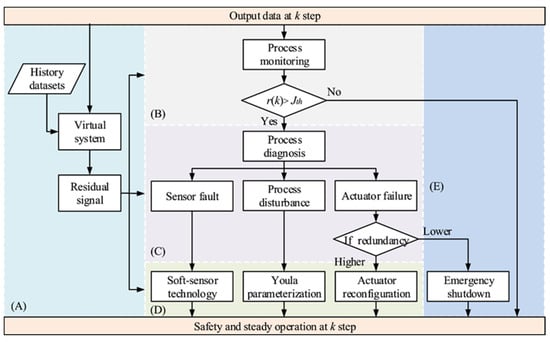

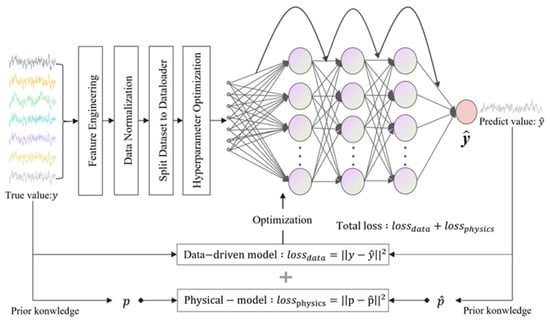

In critical applications such as control strategy formulation and system evolution simulation, data-driven technologies serve as a vital pillar supporting the dynamic capabilities of digital twins. He et al. [68] proposed a data-driven digital twin system and evaluated its effectiveness through multiple simulation experiments. As illustrated in Figure 13, the system seamlessly combines virtual modeling, process monitoring, fault diagnosis, and optimization control within a unified collaborative architecture, thereby enabling efficient coordination and dynamic closed-loop operation of digital twin functions. Chen et al. [69] further enhanced the modeling capability by embedding physical knowledge into a backpropagation neural network (BPNN), constructing a hybrid neural network (DPNN) that combines data-driven and physics-based modeling. They subsequently proposed an improved model, ResDPNN, incorporating residual connections to strengthen learning capacity, as shown in Figure 14. By utilizing machine learning and deep learning methods, the centralized control platform can predict equipment status, characterize system behavior, and optimize control strategy deployment.

Figure 13.

The architecture of the digital twin system [68].

Figure 14.

The flowchart of the ResDPNN framework [69].

To improve system response efficiency and optimize computational resource allocation, several studies have advocated cloud-edge collaborative architectures, which delegate specific computational tasks to edge nodes, thereby alleviating the central system’s computational burden [70]. Concurrently, the emerging twin feedback mechanism enables reverse updating of virtual model states based on real-time system data, establishing a data-driven closed-loop control logic that tightly integrates virtual and physical systems [1].

In summary, the core role of data perception, fusion, and driving technologies in the digital twin platform of the centralized control center is increasingly prominent. These technologies not only ensure the input foundation for high-fidelity system modeling but also provide critical support for achieving intelligent regulation and dynamic closed-loop control. Future research should continue to deepen in areas such as the coordinated deployment of perception systems, data trustworthiness assurance, and the interpretability of model-driven logic.

5. The Critical Role of High-Fidelity Simulation Technology in Water–Wind–Solar Integrated Control Digital Twin Systems

High-Fidelity Simulation (HFS) constitutes a critical component for enabling credible modeling within digital twin systems. It emphasizes the high-precision reproduction and detailed characterization of real physical system behavior, aiming to construct a virtual mapping environment with sufficient credibility. Compared to traditional simulation approaches, HFS not only requires multi-scale detail resolution in the spatial dimension but also captures dynamic response characteristics in the temporal dimension while accounting for multi-physics coupling mechanisms. As such, it serves as an indispensable foundation for constructing digital twins of complex engineering systems.

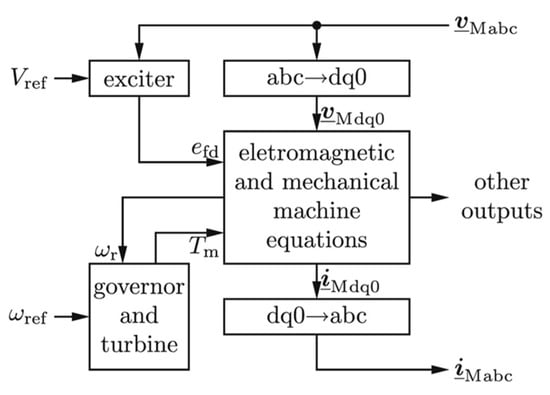

5.1. Multi-Scale Model Construction and Unified Integration Technology

High-fidelity simulation significantly enhances the capability of digital twin systems to represent complex power system operational characteristics by establishing a model framework spanning multiple temporal and spatial scales. Within central control center level digital twin systems, operational dynamics encompass multi-level behaviors ranging from microsecond-scale electromagnetic transients and electrical control processes to hourly-scale energy management. To support cross-scale coupled modeling, researchers have employed multi-timescale coordination mechanisms. By refining modeling granularity and synchronizing time steps, simulation platforms can concurrently respond to both rapid disturbances and slow-varying processes. Gao et al. [71] proposed a modeling and integration approach for synchronous motors that captures electromagnetic and electromechanical transient behaviors across diverse time scales, as illustrated in Figure 15. Huang et al. [72] introduced a heterogeneous multi-scale method for efficiently simulating multi-temporal-scale power system problems represented by the EMT model. By alternating between detailed microscopic EMT models and automatically reduced macroscopic models while adjusting step sizes, combined with a semi-analytical solution for adaptive variable stepping, they ensured accuracy in both fast and slow dynamic simulations.

Figure 15.

Block diagram organization of multi-scale synchronous machine model [71].

At the spatial scale, the modeling scope must span from the equipment layer and substation layer to regional-level systems. Relevant information for modeling at different scales is summarized in Table 4. To address these requirements, modular and hierarchical modeling strategies are widely employed. Shahid et al. [73] introduced the Common Information Model (CIM) to address the integration of heterogeneous data sources in low-voltage distribution networks. This approach extracts grid-related information from various asset management databases and supports the configuration of smart grid application algorithms alongside parameter data-driven updates.

Table 4.

Comparison of modeling at different scales.

Zhang et al. [74] proposed a multi-dimensional, multi-scale intelligent spatial model for digital twin manufacturing units along with its high-fidelity modeling method. They further constructed a hardware–software integrated configuration model for digital twin manufacturing units from an edge–cloud collaboration perspective, establishing an edge–cloud collaborative operation and intelligent control mechanism based on smart contracts. These modeling and integration techniques not only constitute the high-precision core of the digital twin system but also provide a robust foundation for the centralized control center to perform strategy computation, dynamic analysis, and operational simulation.

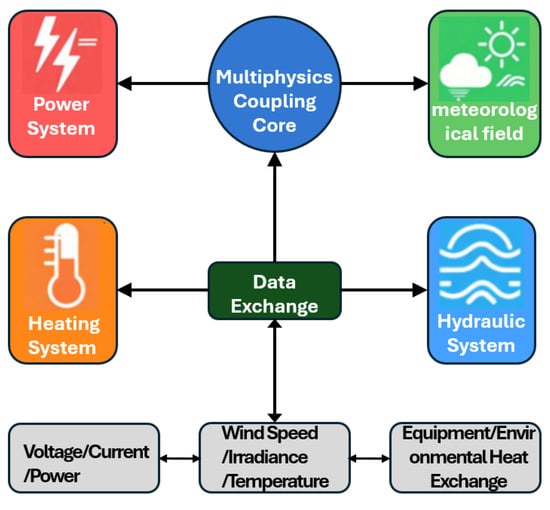

5.2. Multi-Physics Coupling Modeling and Simulation Accuracy Optimization

The power conversion and operational processes within the integrated control system for hydro–wind–solar power are illustrated in Figure 16. Traditional digital twin models primarily emphasize electrical-side modeling, neglecting the dynamic interactions across other domains and thereby limiting the system’s ability to reflect complex operational behaviors. High-fidelity simulation addresses precise reproduction of physical laws, employing multi-physics joint modeling to establish coupling relationships across electrical, thermal, hydraulic, and pneumatic domains [75]. For example, wind power systems require simultaneous consideration of feedback between meteorological disturbances and blade dynamic responses, while photovoltaic systems involve nonlinear correlations among temperature, irradiance, and electrical characteristics. By incorporating multi-physics mechanisms with rich model details and well-defined boundary conditions, digital twins achieve high-fidelity representation of physical processes in complex operational environments. This enhances their ability to identify abnormal operations, regulatory risks, and other critical operating conditions.

Figure 16.

Multi-physics coupling relationships in the integrated control system for hydropower, wind power, and solar power.

The disparity in temporal scales across multiple physical domains poses significant challenges to simulation accuracy. For example, in power electronic systems, the evolution of electromagnetic transients occurs at a significantly higher rate than meteorological or hydrological processes. Using a uniform time step would compromise both simulation efficiency and stability. Consequently, high-fidelity simulations often utilize adaptive time-step adjustment and parallel solution techniques, employing asynchronous computation strategies to ensure consistency between high-frequency physical processes and low-frequency system responses [76]. Furthermore, recent studies have introduced coupling mechanisms based on optimization algorithms, including genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization, to dynamically regulate boundary conditions and interaction parameters. This enhances the stability and adaptability of multi-physics coupled models in complex operational scenarios [77].

Multi-physics coupled modeling not only significantly improves the digital twin system’s perception and dynamic response capabilities in real-world operational environments but also provides higher credibility for simulation results such as dispatch verification, anomaly detection, and strategy rehearsal. Further research should explore universal modeling frameworks and standardized interface technologies for cross-domain coupling mechanisms, supporting the widespread application of high-fidelity digital twins within centralized control systems.

5.3. Computational Optimization and Real-Time Response Techniques in High-Fidelity Simulation

Building a high-fidelity digital twin system within integrated hydro–wind–solar power control systems requires precise restoration of system states and rapid response capabilities. Traditional simulation approaches often struggle to simultaneously achieve both accuracy and speed when confronting challenges such as the large-scale integration of power electronic devices in complex systems, the nonlinear amplification of coupling processes, and the diversification of simulation tasks. Consequently, optimizing computational efficiency and real-time response capabilities in high-fidelity simulation is crucial for enhancing digital twin performance.

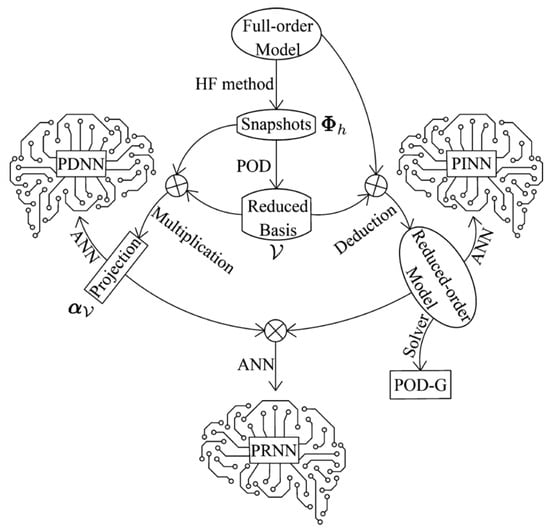

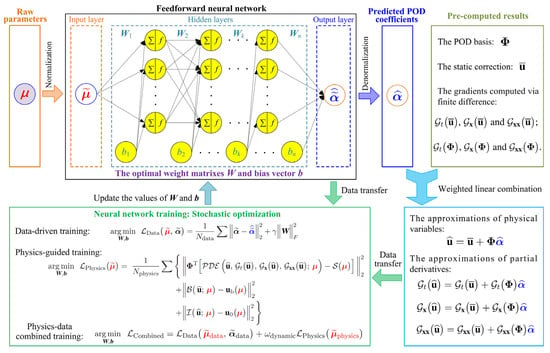

At the modeling level, researchers extensively employ techniques such as reduced-order modeling (ROM) to effectively compress system dimensions while preserving core dynamic characteristics, thereby significantly reducing computational resources required for simulation [78]. For instance, Chen et al. [79] introduced a reduced-order modeling approach based on a physical-information-driven machine learning framework, enabling efficient parameterized partial differential equation (PDE) simulations, as illustrated in Figure 17. Similarly, Fu et al. [80] introduced a Physical Data Combined with Machine Learning (PDCML) approach for non-intrusive parameter reduction under limited data conditions, as depicted in Figure 18. This method utilizes Principal Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) to derive basis functions from a finite set of high-fidelity snapshots, transforming parameter reduction into a reliable mapping between system parameters and POD coefficients. The formula in Figure 18 is

where denotes the static correction, represents the POD basis, and stands for the predicted POD coefficients.

Figure 17.

Framework of physics-informed machine learning for reduced-order modeling [79].

Figure 18.

The workflows of non-intrusive parametric ROM of nonlinear dynamical systems via the data-driven method, the physics-guided method, and the physics–data combined method [80].

The approximations of partial derivatives:

where , , , , , and denotes the gradients computed via finite difference.

where denotes the data-driven loss function to train the neural network, represents the number of the training data pairs , and stands for the weight regulation constant. The first term of the loss function is the mean square error to represent the discrepancy between and . The second term is the weight regulation term.

where denotes the loss function of the physics-guided neural network, and is the number of parameter points used for physics-guided training.

where is the physics–data combined loss function, and is a dynamic weight coefficient to adjust the physics–data proportion in the loss function .

In the context of computational framework optimization, parallel computing, heterogeneous collaboration, and graph computing technologies are widely adopted to enhance simulation throughput. Current mainstream approaches include GPU-based high-concurrency task execution architectures, suitable for intensive power flow and dynamic power flow calculations in large-scale wind and solar power stations [81]. Jin et al. [82] addressed the sequential single-core execution of individual dynamic simulations by integrating modern high-performance computing (HPC). They designed and implemented parallel dynamic simulations to accelerate individual dynamic simulations for transient stability assessment, maximizing computational hardware utilization and simulation performance by guiding the matching of simulation algorithms with computational hardware.

To enable adaptive response of simulation systems to operational environment changes, recent research has focused on online model updating and rapid reconfiguration. Through mechanisms such as dynamic model switching, incremental learning, and online parameter tuning, simulation engines can achieve efficient reconfiguration during sudden system state changes, ensuring continuous simulation reliability [83].

In summary, computational optimization and real-time response technologies have become critical enablers for the evolution of high-fidelity digital twin systems toward engineering-level applications. Future efforts must continue advancing in areas such as coordinated model compression and scheduling, heterogeneous computing resource management, and the design of simulation feedback mechanisms to support the complex and dynamic operational demands of integrated hydro–wind–solar power control systems.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

The analysis suggests that hydro–wind–solar integrated control systems may benefit from enhanced virtual–physical coupling and high-fidelity simulations, which can improve situational awareness and support more informed decision-making. Compared with conventional centralized control methods, digital twins potentially enable a shift from reactive monitoring to proactive optimization, particularly under high renewable penetration conditions characterized by uncertainty, volatility, and multi-timescale interactions.

Our review indicates that unified modeling of heterogeneous energy sources appears to be an important factor in enabling coordinated scheduling and system-level optimization. Inconsistencies in information models and interface standards may limit the effectiveness of data fusion and intelligent control applications. High-fidelity simulation, especially when incorporating multi-scale and multi-physics coupling, could contribute to more reliable representations of complex operational behaviors, although its practical performance may depend on computational resources, model assumptions, and data quality.

Moreover, the combination of physics-based and data-driven modeling approaches shows promise in supporting adaptive and scalable digital twin implementations. While artificial intelligence methods can enhance prediction and responsiveness, their effectiveness is contingent on model interpretability and the reliability of real-time data streams. These observations imply that future digital twin platforms may benefit from flexible, co-optimized designs in which modeling, data processing, and computational mechanisms are continuously aligned to operational needs.

6.2. Conclusions

This paper presents a systematic review of digital twin and high-fidelity simulation technologies for hydro–wind–solar integrated centralized control systems, with an emphasis on system requirements, architectural design, enabling technologies, and simulation credibility. The analysis demonstrates that digital twins provide a unified technical framework for addressing the challenges arising from multi-source heterogeneity, renewable power volatility, and cross-timescale operational coordination.

The review shows that layered digital twin architectures, combined with unified information modeling and multi-source data fusion, significantly enhance situational awareness and operational transparency in centralized control environments. More importantly, high-fidelity simulation is identified as a critical foundation for trustworthy digital twins, enabling accurate representation of multi-scale dynamics and multi-physics interactions that are essential for strategy evaluation and risk assessment. The integration of physics-based modeling, data-driven methods, and computational optimization further supports real-time responsiveness and adaptive system evolution. Quantitative analysis suggests that the implementation of digital twin and high-fidelity simulation technologies could improve dispatch efficiency, fault response speed, and system scalability by roughly 20–40%.

From an engineering perspective, the findings indicate that future hydro–wind–solar centralized control platforms should move beyond isolated simulation tools toward tightly coupled virtual–physical systems capable of closed-loop optimization. Such systems will increasingly rely on standardized modeling frameworks, cloud–edge collaborative computing, and intelligent learning mechanisms. Overall, this study provides a structured reference for the development of reliable and scalable digital twin platforms, contributing to the advancement of intelligent control technologies for new power systems with high renewable energy penetration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and J.C.; methodology, Y.M. and Y.R.; validation, L.D.; investigation, F.H. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.D. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the technology project of China Huaneng Group Co., Ltd.: Research and Demonstration of Autonomous Controllable Computer Monitoring System for Clean Energy in Large River Basins (No. HNKJ24-H135) and the Technology Talent and Platform Program of Yunnan Province (202405AK340002).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yongjun Liu was employed by the company Huaneng Lancangjiang River Hydropower Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Reddy, S.S. Optimal scheduling of thermal-wind-solar power system with storage. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. Discussion on construction of new energy centralized control center. Mech. Electr. Tech. Hydropower Stn. 2016, 39, 17–19+104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ge, L.; Wu, J. Unified and Comprehensive Anti-maloperation System in Centralized Control Center for New Energy Power Stations. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2018, 42, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Feasibility Study on the Establishment of Training Simulation System for Hydropower Stations in Hongshui River Basin. Water Power 2017, 43, 16–18+54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Wu, G. Simulation training system for 220kV centralized control station and unmanned substation. East China Electric Power 2004, 32, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J. The Development and Application of 500KV Substation Simulation Training System in Suzhou. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.; Teng, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, M. Full realization of digitalization is the only way to intelligent manufacturing-interpretation of “The Road to Intelligent Manufacturing: Digital Factory”. China Mech. Eng. 2018, 29, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yan, J.; Feng, D. Digital twin framework and its application to power grid online analysis. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 5, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Dong, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Modeling Method of Power Cyber-Physical System Considering Multi-layer Coupling Characteristics. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 45, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wu, X.; Leng, Y.; Hou, H.; Wu, S.; Qiu, J. Review of the Development of Digital Twin Technology in New Type Power Systems. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 3872–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Hao, J.; Yang, T.; Du, X.; Wang, S.; Lyu, H.; Chen, H.; Chen, J. Development and Challenges of Intelligent Operation and Maintenance of Integrated Energy Systems Based on Digital Twin. Proc. CSEE 2026, 46, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hackl, C.M.; Anand, A.; Thommessen, A.; Petzschmann, J.; Kamel, O.; Braunbehrens, R.; Kaifel, A.; Roos, C.; Hauptmann, S. Digital twins for the future power system: An overview and a future perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.B.; Al-Faiz, H.; Hasini, H.; Al-Bazi, A.; Kazem, H.A. A comprehensive review of the dynamic applications of the digital twin technology across diverse energy sectors. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.; Panda, S.; Rout, P.K.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V. Digital twin enabled smart microgrid system for complete automation: An overview. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marot, A.; Kelly, A.; Naglic, M.; Barbesant, V.; Cremer, J.; Stefanov, A.; Viebahn, J. Perspectives on future power system control centers for energy transition. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J. Coordinated optimal operation of hydro–wind–solar integrated systems. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J.; Xie, N.; Yang, S. Real-time operational optimization for flexible multi-energy complementary integrated energy systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Xu, T.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q. Multi-time Scale Optimal Scheduling of Active Distribution Network Considering Source Load Storage Coordination. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 10321–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, G.; Khaparde, S.A. A common information model oriented graph database framework for power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 32, 2560–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M. Product Lifecycle Management: Driving the Next Generation of Lean Thinking; McGraw Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grieves, M.W. Virtually Intelligent Product Systems: Digital and Physical Twins. In Complex Systems Engineering: Theory and Practice; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piascik, R.; Vickers, J.; Lowry, D.; Scotti, S.; Stewart, J.; Calomino, A. Technology Area 12: Materials, Structures, Mechanical Systems, and Manufacturing Road Map; NASA Office of Chief Technologist: Washington, WA, USA, 2010; pp. 15–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C. Advancements and challenges of digital twins in industry. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, N.; Sun, L.; Zhang, S. Modular based flexible digital twin for factory design. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.; Liu, J.; Xiong, H.; Ding, X.; Liu, S.; Weng, G. Connotation, architecture and trends of product digital twin. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 23, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, C.; Negri, E.; Fumagalli, L. Review of digital twin applications in manufacturing. Comput. Ind. 2019, 113, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Atawi, I.E.; El-Hameed, M.A.; Abuelrub, A. Digital Twin Technology for Renewable Energy, Smart Grids, Energy Storage and Vehicle-to-Grid Integration: Advancements, Applications, Key Players, Challenges and Future Perspectives in Modernising Sustainable Grids. IET Smart Grid 2025, 8, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ji, W. Digital twin-driven carbon emission prediction and low-carbon control of intelligent manufacturing job-shop. Procedia CIRP 2019, 83, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H. Research on architecture and system deployment of intelligent power plant based on digital twin. Chin. J. Intell. Sci. Technol. 2019, 1, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Guo, B.; Liu, X.; Yan, Y. Research Status and Prospects of Digital Twin Key Technologies for Intelligent Operation and Maintenance of Power Equipment. High Volt. Eng. 2026, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, M.; Rubanenko, O. Implementation of digital twin for increasing efficiency of renewable energy sources. Energies 2023, 16, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ding, G.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, K.; Qin, S. Iterative updating of digital twin for equipment: Progress, challenges, and trends. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifat, M.M.H.; Choudhury, S.M.; Das, S.K.; Ahamed, M.H.; Muyeen, S.M.; Hasan, M.M.; Ali, M.F.; Tasneem, Z.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; et al. Towards electric digital twin grid: Technology and framework review. Energy AI 2023, 11, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Cong, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, X. Key Technology and Application Prospect of Digital Twin in Power Equipment Industry. High Volt. Eng. 2021, 47, 1539–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Meng, F. Application of Digital Twin in Power Grid Inspection. In 2023 IEEE 12th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Cao, Q.; Jia, M.; Chen, Y.; Huang, S. Concepts, Characteristics and Prospects of Application of Digital Twin in Power System. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, Z.; Lei, J. Prospect and Thinking of Digital Power Grid Based on Digital Twin. South. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 14, 18–24+40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Zeng, S.; Yan, P.; Zhao, J.; Jia, B. Typical Application and Prospect of Digital Twin Technology in Power Grid Operation. High Volt. Eng. 2021, 47, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tao, F. Evaluation index system for digital twin model. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 27, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Cool thoughts on digital twins and the modeling and simulation technology behind them. J. Syst. Simul. 2020, 32, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zomerdijk, W.; Palensky, P.; AlSkaif, T.; Vergara, P. On future power system digital twins: A vision towards a standard architecture. Digit. Twins Appl. 2024, 1, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xi, W.; Cai, T.; Yu, H.; Li, P.; Wang, C. Concept, Architecture and Key Technologies of Digital Power Grids. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, Y.; Peng, B.; Miao, Z.; Xiong, X. Research on digital transformation and application of key business of power grid planning. Adv. Eng. Technol. Res. 2024, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, D.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Y. Key technologies and applications of collaboration between digital power grid and Internet of Things. Digit. Twins Appl. 2024, 1, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Li, B.; Cai, W.; Zhao, G.; Lu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, H. Discussion on the Functional Architecture System Design and Innovation Mode of Intelligent Power Internet of Things. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, J.; Liang, Z.; Du, Z. Application of digital twin in power equipment operation and maintenance. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of China Electrotechnical Society, Beijing, China, 17–18 September; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhang, Z. Research on Digital Twin-Based Assembly Workshop Modeling and Simulation Methods. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 8th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; My, C.A.; Le, C.H.; Zlatov, N.; Hristov, G.; Gao, J.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Mahmud, J.; Bui, T.T.; Packianather, M.S. Motion and condition monitoring of an industrial robot based on digital twins. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual International Conference on Material, Machines and Methods for Sustainable Development (MMMS2022), Can Tho, Vietnam, 10–13 November 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. Application of computer technology in new energy simulation modeling and safety calculation. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2022, 43, 543. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Wu, B.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, P.; Huang, K.; Guo, Y.; Du, Z.; Zeng, Q. Review of Forward and Reverse Multi-field Simulation Technology for Digital Twin of Electrical Power Equipment. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 4215–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, G.N.; Steinmetz, C.; Rodrigues, R.N.; Henriques, R.V.B.; Rettberg, A.; Pereira, C.E. A methodology for digital twin modeling and deployment for industry 4.0. Proc. IEEE 2020, 109, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wu, J.; He, X.; Tai, N.; Hu, S. Application Prospect and Key Technologies of Digital Twin for Shipboard Integrated Power System. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 2456–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Data-driven estimation of building energy consumption with multi-source heterogeneous data. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 114965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Yu, J. Deep feature interactive network for machinery fault diagnosis using multi-source heterogeneous data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, L.; Min, Y.; Xiong, X.; Feng, Y.; Yi, P. Frequency Response Model of Doubly Fed Induction Generator Wind Turbine. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Smart Power & Internet Energy Systems (SPIES), Beijing, China, 9–12 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, W.; He, G.; Guo, Z. Impedance Modeling and Characteristics Analysis of Photovoltaic Generation Considering Photovoltaic Array. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 5122–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Z. Design of a modified model predictive control and composite control strategy for hydraulic turbine regulation system. ISA Trans. 2025, 167, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Ma, T. A Survey of Reliability Modeling and Evaluation Methods for Active Distribution Cyber-physics Systems. Power Syst. Technol. 2019, 43, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Hu, J.; Ouyang, J.; Ou, S. An Integrated Data-Driven and Physics-Based Approach for Dynamic Operation Simulation of Electric Vehicles; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhong, W.; Liu, B.; Xia, G. Optimal Scheduling of Industrial Park Integrated Energy Systems Considering Dynamics of Multiple Fluid Networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 514, 145743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, L.; Di, X.; Du, X. Research on The Construction Technique of Power Grid Digital Twin Model Based on Multi-source Heterogeneous Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on New Energy and Power Engineering (ICNEPE), Guangzhou, China, 8–10 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, P.; Wüthrich, M.; Blume, S.; Sansavini, G. Data-driven modeling for long-term electricity price forecasting. Energy 2022, 244, 123107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.; Zhang, W.; Cerrai, D.; Bagtzoglou, A.; Wanik, D.; Anagnostou, E. A hybrid physics-based and data-driven model for power distribution system infrastructure hardening and outage simulation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 225, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Ji, Y. Unified Modeling for Adjustable Space of Virtual Power Plant and Its Optimal Operation Strategy for Participating in Peak-shaving Market. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Han, Q.; Ding, Z. An intelligent analysis method of security and stability control strategy based on the knowledge graph. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1022231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, G. Collecting and Analyzing Multidimensional Categorical Data Under Shuffled Differential Privacy. J. Softw. 2022, 33, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X. Research on Flexible Operational Optimization of CCHP System Based on Intelligent Fusion Algorithm. J. Syst. Simul. 2024, 36, 2330–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Chen, G.; Dong, C.; Sun, S.; Shen, X. Data-driven digital twin technology for optimized control in process systems. ISA Trans. 2019, 95, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Huang, Q.; Song, M.; Liu, X.; Zeng, W.; Song, H.; Cheng, K. A study on the development of digital model of digital twin in nuclear power plant based on a hybrid physics and data-driven approach. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 271, 126289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Zhao, Y. Cloud-edge collaborative data storage and retrieval architecture for industrial scenarios. J. Comput. Appl. 2025, 45, 2902–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Strunz, K. Multi-scale simulation of multi-machine power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2009, 31, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xiong, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, K. A Heterogeneous Multiscale Method for Efficient Simulation of Power Systems with Inverter-Based Resources. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 4292–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, K.; Nainar, K.; Olsen, R.L.; Iov, F.; Lyhne, M.; Morgante, G. On the use of common information model for smart grid applications—A conceptual approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5060–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, G.; Xiao, J.; Qin, T.; Zhou, Y. Multi-dimensional and multi-scale modeling and edge-cloud collaborative configuration method for digital twin manufacturing cell. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 29, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tao, L.; Rong, B.; Rui, X. Review of dynamics simulation methods for multi-field coupling systems. Adv. Mech. 2023, 53, 468–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z. Multi-level Simulation Modeling Technology for Urban Rail Traction Power Supply System. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Technologies for Rail Transportation (EITRT) 2023, Beijing, China, 19–21 October; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariquzzaman, M.; Li, P.; Barton, S.J.; Thurlbeck, A.P.; Kilgore, T.; Brekken, T.K.A.; Cao, Y. Multi-physics and multi-timescale modeling of hydrokinetic turbine energy conversion system. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 6028–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yuan, J.; You, X.; Zhang, Z. Research on FPGA optimization approach of power electronics real-time simulation modeling. Electr. Mach. Control 2020, 24, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Hesthaven, J.S.; Zhang, C. Physics-informed machine learning for reduced-order modeling of nonlinear problems. J. Comput. Phys. 2021, 446, 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Xiao, D.; Fu, R.; Li, C.; Zhu, C.; Arcucci, R.; Navon, I.M. Physics-data combined machine learning for parametric reduced-order modelling of nonlinear dynamical systems in small-data regimes. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 404, 115771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Nie, N.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Zhou, C.; Li, S.; Yao, K.; Li, S.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Large-Scale Simulation of Structural Dynamics Computing on GPU Clusters. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, Denver, CO, USA, 12–17 November 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Huang, Z.; Diao, R.; Wu, D.; Chen, Y. Comparative implementation of high performance computing for power system dynamic simulations. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; He, X.; Tang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, D. Dynamic coupling across energy forms and hybrid simulation of the multi-energy system. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1209845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.