Abstract

Energy recovery technology is becoming a crucial part of modern approaches that address decarbonization, efficiency, and transitioning into a circular economy. In addition, apart from its advancements in efficiency and environmental benefits, its progress appears to be progressively limited due to its maturity and increasing complexity. In this case, innovation that focuses solely in the firm appears ineffective because more and more important knowledge in terms of innovation in processes and environmental aspects is becoming and remaining outside of organizational boundaries. In this paper, open innovation will be explored in its function as a structural innovation method of advancing energy recovery technology. The paper employs the narrative literature review of peer-reviewed literature indexed in the Scopus database to explore the implications of the outside-in model of open innovation, the inside-out model of open innovation, and the coupled model of open innovation with respect to the primary recovery processes of energy such as combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery. The literature incorporates findings about the implications of knowledge inflows and outflows with respect to the mentioned energy recovery processes. The results show that open innovation efficacy strongly varies according to the degree of technological maturity and performance issues, in that outside-in open innovation tends to be very effective in mature and semi-mature technology sectors, where incremental improvements in efficiency require specialized knowledge outside the industry, while coupled open innovation is crucial for addressing system-wide issues in areas such as emissions, regulatory compatibility, and infrastructure integration, while inside-out innovation is largely a means of facilitating technology dissemination and standardization once a degree of technological maturity had been realized. This study, through the association of selective open innovation practices with corresponding energy recovery technology and challenges, aims to provide a more nuanced perspective on the assistive potential of collaborative innovation in effecting sustainable development in energy recovery technology.

1. Introduction

While open innovation and energy recovery individually have been discussed in detail in previous research, only a few studies have focused on how the integration of different open innovation models—outside-in, inside-out, and coupled—can optimally enhance energy recovery technologies for better efficiency of various energy recovery methods such as combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery [1,2].

The presented research covers a literature gap in holistic analysis that links open innovation strategies with advances in energy recovery. Much of the earlier research has focused on the technological improvement of various energy recovery processes and has not reviewed how collaborative innovation models can accelerate the development, implementation, and scalability of the technologies [3,4,5,6,7]. The research fills this gap by underlining how the acquisition of external knowledge, knowledge sharing, and collaborative innovation efforts are contributing to energy efficiency improvements, reduced environmental impact, and wider industry-scale adoption of sustainable energy solutions. It also helps in the discussion of sustainable development by showing ways in which open innovation can facilitate the bridge that gaps interdisciplinary capabilities, industry/academia and government partnerships, and removes inhibitors to the introduction of energy recovery technologies. The findings present valuable lessons that could be useful to policymakers, industry leaders, and researchers in the pursuit of increasing the efficiency and sustainability of energy recovery systems through strategic knowledge exchange and innovation-driven collaboration.

Energy recovery has emerged as an important research topic in the wake of the challenge of decarbonization and the push for the circular economy and resource efficiency in industrial processes and the management of waste. Conventional energy systems, constrained by an increasing regulatory regime and, more so, the rising societal expectations for the implementation of the sustainability agenda, have seen energy recovery technologies become more and more relevant for their ability to enable the objectives of emission reduction, the reduction in waste, and the integration of energy systems, as opposed to just facilitating supportive improvements in efficiency [1,2,3]. It has been established from previous research studies that, although the primary technologies for energy recovery, such as combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, digestion, and landfill gas recovery, respectively, are relatively mature, their further development is impeded by the capital constraints, the regulatory lock-in and the increasing levels of complexity [4,5].

In this case, the open innovation approach has become more relevant as an instrument for realizing further technological and organizational development in the area of energy recovery. The open innovation approach focuses on the intentional inflows and outflows of knowledge across organizational boundaries, ensuring that firms are able to tap into complementary knowledge and advance technological development in ways that are most effective for addressing complex issues in the environment [6,7]. Energy sectors are known to have critical knowledge for developments in efficiency improvement, emission management, digitalization for monitoring, and system integration carried out outside the firms in higher educational institutions, research institutions, technology firms, or public institutions [8,9]. Evidence from studies indicates the importance of innovation approaches based on collaboration and innovation ecosystems specifically for capital-intensive and regulation-driven industries, where innovation performance not only relies on technological capabilities but on institutional alignment as well [10,11].

Therefore, the relevance of open innovation in energy recovery goes beyond the improvement brought on by collaboration and knowledge-sharing efforts. This is because open innovation helps address the innovation barriers in energy recovery that result from the level of maturity and system interdependencies in energy recovery, which cannot be effectively broken down by the application of the closed innovation paradigm [12,13].

Modern innovation activities in the area of energy recovery are increasingly marked by a paradigm shift from a more isolated, technology push-oriented approach to innovation to more networked and interdependent innovation patterns. Whereas the initial innovations in energy recovery technologies have been mainly the result of internal engineering and process optimization, modern innovation activities are increasingly based on external know-how sources, cross-industry collaboration, and integration into digital and regulatory infrastructure systems [1,2,14]. Technological innovations in such areas as materials, process control, emission sensing, and optimization have increasingly evolved outside the domain of the traditional energy recovery companies, needing efficient mechanisms to absorb external know-how [15,16,17]. At the same time, the innovation process in the area of energy recovery is heavily driven by environmental regulation, public policy goals, and wider system constraints associated with waste management and energy infrastructure, increasingly supporting a more collaborative and ecosystem-oriented innovation approach [18,19,20]. Consequently, the innovation process associated with energy recovery technologies is currently a socio-technical process where technological developments, organizational capacities, and institutional conditions are increasingly coupled together, forming a situation where open innovation not only presents advantages but quite often is a necessary strategy to ensure modern technological development and integration [14,21,22].

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the role of open innovation in the enhancement of energy recovery processes, supporting sustainable development and energy efficiency. More precisely, this study investigates how different open innovation models, such as outside-in, inside-out, and coupled innovation, may facilitate technological advancement, optimize energy recovery methods, and enable cross-industry collaboration in the development of more efficient and environmentally sustainable energy solutions.

This paper tries to respond to the following research questions:

Q1—How can open innovation models (outside-in, inside-out, and coupled) enhance the efficiency and sustainability of energy recovery processes?

Q2—What are the main barriers and challenges to implementing open innovation in energy recovery, and how can they be addressed?

Q3—What are the potential benefits of applying open innovation in energy recovery in terms of technological advancement, environmental impact, and economic feasibility?

The paper describes the various approaches in energy recovery from waste—categorically examining combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery—and makes an attempt at explaining how applying external knowledge by sharing internal novelties develops better waste-to-energy conversion; efficiency in the production of biogas is increased and has an optimum treatment of waste heat. The research will also try to underline the strategic advantages of open innovation in order to accelerate technological adoption, reduce costs, and increase scalability for energy recovery solutions.

While energy recovery will be viewed in this research as a wide-ranging analytical category, the literature review was carried out within a well-defined technology and functional scope. In this paper, the meaning of energy recovery will be viewed as the use of residual/waste energy and materials as fuel sources within the waste, industrial, or environmental sectors rather than as the more general technology of efficiency gain. In this respect, the literature review will concentrate on technologies where energy recovery represents the prime system function—like those of burning, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery—rather than the secondary efficiency parameter in systems having no connection with energy recovery. This would mean that technologies of the regenerative braking sort—sometimes classified together with energy recovery—are viewed in this paper as boundary examples of the application of the concept of energy recovery rather than as the subject of the literature assessment.

Even though there is a considerable amount of literature focusing on open innovation within the energy industry and, independently, the technological dimensions of energy recovery, there is a research gap within the integrative research stream, where open innovation archetypes are connected, in a problem-solving and situation-specific manner, to various energy recovery technologies. The current literature generally presents studies on open innovation, concentrating either on the organizational practices of firms, independently of specific energy recovery technologies, or technical evaluations, ignoring the organizational practices and innovation governance structures. This research aims to close the mentioned research gap by concentrating the empirical investigation on waste or process-oriented energy recovery technologies while adopting a more encompassing research perspective for the explanation of open innovation configurations in accordance with technological maturities, prevailing innovation problems, or system constraints.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a narrative literature review as its primary methodological approach [13,23,24]. The choice of a narrative review is deliberate and methodologically justified by the interdisciplinary and conceptually heterogeneous nature of the research problem, which lies at the intersection of open innovation studies, energy recovery technologies, sustainability research, and innovation management. In contrast to systematic reviews, which aim at exhaustive coverage and statistical aggregation of narrowly defined empirical results, a narrative review allows for analytical synthesis, conceptual integration, and theory-informed interpretation across fragmented bodies of literature. This approach is particularly suitable for examining how different open innovation models are applied across diverse energy recovery technologies and organizational contexts.

Although narrative in nature, the review follows a transparent and structured protocol to ensure methodological rigor, replicability, and coherence. The review process consisted of four sequential stages:

- database selection and search strategy design,

- application of inclusion and exclusion criteria,

- screening and selection of relevant publications,

- thematic analysis and synthesis of the selected literature.

The literature search was conducted exclusively in the Scopus database, selected due to its broad coverage of peer-reviewed journals across engineering, environmental sciences, management, and social sciences. Scopus is particularly appropriate for interdisciplinary research that spans both technological and organizational domains.

The search was carried out in February 2025 and covered publications from January 2015 to January 2025, a period chosen to capture contemporary developments in open innovation and energy recovery while avoiding conceptual obsolescence. The search strategy combined general and technology-specific query strings using Boolean operators. In addition to the keyword combinations reported in Table 1, the following explicit search strings were applied in the Scopus “Title–Abstract–Keywords” field:

Table 1.

Search results for papers with the given keywords on Scopus.

- “open innovation” AND “energy recovery”

- “open innovation” AND (“waste-to-energy” OR “energy-from-waste”)

- “open innovation” AND combustion AND energy

- “open innovation” AND gasification AND energy

- “open innovation” AND pyrolysis AND energy

- “open innovation” AND “anaerobic digestion” AND energy

- “open innovation” AND “landfill gas” AND energy

To ensure conceptual completeness, additional supporting searches were conducted separately for:

- “open innovation model” OR “outside-in innovation” OR “inside-out innovation” OR “coupled innovation”, and

- “energy recovery technology” OR combustion OR gasification OR pyrolysis OR “anaerobic digestion” OR “landfill gas recovery”.

This two-track strategy made it possible to capture both direct intersections between open innovation and energy recovery and theoretical or technological studies that inform their integration, even when not explicitly combined in the same publication.

The screening process applied clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Publications were included if they:

- were peer-reviewed journal articles, reviews, or conference papers with substantial conceptual or empirical content;

- were published in English;

- addressed open innovation, collaborative innovation, or inter-organizational knowledge flows in relation to energy systems, waste management, or energy recovery technologies;

- provided theoretical frameworks, models, or empirical insights relevant to the analysis of open innovation mechanisms applicable to energy recovery.

Publications were excluded if they:

- focused exclusively on technical optimization of energy recovery without any innovation, collaboration, or knowledge-management dimension;

- addressed open innovation in sectors unrelated to energy, sustainability, or industrial processes;

- were editorials, notes, book reviews, or purely descriptive reports lacking analytical depth.

The initial search returned a broad pool of publications (as summarized in Table 1). Screening was conducted in two stages. First, titles and abstracts were reviewed to assess relevance to the research questions. Second, full-text analysis was performed for publications that met the initial relevance threshold. Particular attention was paid to conceptual clarity, methodological transparency, and explicit discussion of innovation mechanisms, collaboration structures, or knowledge flows.

Given the relatively small number of publications directly combining open innovation with specific energy recovery technologies, the final corpus intentionally integrates core open innovation literature with technology-specific energy recovery studies, allowing for cross-domain interpretation rather than narrow bibliometric filtering.

The synthesis followed an inductive–deductive thematic analysis. Deductively, the review was structured around two established classification frameworks:

- (1)

- the division of open innovation into outside-in, inside-out, and coupled models, and

- (2)

- the categorization of energy recovery technologies into combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery.

Inductively, recurrent themes were identified through iterative reading and comparison of the selected literature. These themes included, among others:

- mechanisms of external knowledge acquisition and integration;

- intellectual property sharing and licensing strategies;

- cross-sectoral and cross-disciplinary collaboration patterns;

- technological scaling and diffusion barriers;

- regulatory and organizational constraints affecting open innovation in energy recovery.

The final synthesis integrates these themes into a coherent analytical framework that explains how different open innovation models influence the development, efficiency, and sustainability of specific energy recovery processes, while also identifying research gaps and unresolved challenges.

In this paper, the authors perform a narrative review in order to analyze the literature on existing open innovation models—outside-in, inside-out, and coupled innovation—and their influence on increasing the efficiency and sustainability of the energy recovery process. An extensive literature search was carried out by the authors in the Scopus database, selecting all the relevant publications from the last ten years, that is, from 2015 to 2025. It involves the identification of keywords containing “open innovation” and “energy recovery,” including other specific energy recovery technologies like combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery.

It is in this regard that such a narrative review study was able to bridge disparate streams of research, combining theoretical insights with empirical findings in order to build a holistic framework through which open innovation drives technological advancement in energy recovery. The result has been the emergence of some dominating themes that include but are not limited to the role of external knowledge acquisition in realizing efficiency in energy conversion, strategic advantages of knowledge-sharing networks, and challenges associated with protecting intellectual property along with regulatory barriers.

This review allowed a discussion on the wider implications of open innovation for sustainable development, developing how collaborative knowledge flows can be environmentally and economically more sustainable. While systematic reviews focus on quantifiable data extraction, the narrative approach provided a synthesis that was interpretative in nature, drawing out links between the fragments of research and identifying emergent trends and research gaps.

This study applies literature review as a method of research. The authors conducted an analysis of the publications indexed by Scopus. Table 1 presents the results of a search for scientific articles in the Scopus database based on specific keywords, data of 3 February 2025. The data include the total number of publications and the number of articles published from 2015 onwards. In this regard, the authors have chosen a time period of ten years starting from 2015 to 2025, while considering the first month of January 2025. Combinations of keywords related to open innovation and different energy recovery technologies were used in the present study.

The choice of the 2015–2025 interval has a theoretical and empirical foundation in the structural transformation in both open innovation paradigm approaches and energy recovery system structures noticed in the past decade. The interval does not symbolize an arbitrary bibliometric interval or range; it actually matches a unique stage in the conceptual maturity and transformation stages in the two research trends.

As far as open innovation research is concerned, the year 2015 represents a turning point that began to move from the phase of conceptualization to the applications at the systemic level, ecosystems, and the green/sustainability focus [10,11,15,16]. Until the year 2015, the concept of open innovation was largely concentrated on the issue of permeability at the company level, to R&D outsourcing, licensing, and bilateral agreements. Since 2015, there has been a remarkable move in the open innovation literature toward innovation ecosystems among multiple actors, inter-sectoral knowledge transfer, and the coupling of open innovation concepts and practices related to the grand challenges of society, including the fields of sustainability, energy, and climate change. This was particularly apparent in the related literature that emerged since the mid-2010s.

The end year of 2015 marks the beginning of a new era for energy and waste policy, focusing on the challenges of decarbonization, resource efficiency, and the circular economy [25,26,27,28,29]. This era has seen the evolution of energy recovery technology from semi-mature and autarkic technologies to integrated, digitally enabled, and system-integrated technologies, which are increasingly linked to smart grids, monitoring systems, and hybrid energy systems. This has resulted in a series of new interdependencies on external knowledge, cross-boundary collaboration, and coordination across organizations, which has made open innovation a relevant concept to the technology developments but even a prerequisite for the technology developments and scaling-up.

Since 2015, energy recovery has become more deeply intertwined with innovation frameworks underpinned by policy pressures, where regulatory forces, environment-related goals, and collaborative public–private engagements exerted a strong impact on innovation pathways. This context reinforced greater demands for collaborative innovation ecosystems, cross-institutional knowledge sharing, and joint innovation development by the private, academic, and public sectors [28,29]. Consequently, since 2015, there has been a rising concern for innovation research on energy recovery, which goes beyond a technical procedure, thereby fitting perfectly within the open innovation framework under an analytical lens.

From the table, the highest number of articles deal with the general term “energy recovery,” in which 46,697 publications were found, of which 29,870 were from 2015 onwards. That is understandable because energy recovery is a generic term covering many technologies such as combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, and anaerobic digestion applied in energy, waste management, and industry. The second most studied keyword is “open innovation,” which was mentioned in 8414 publications, of which 5913 were published from 2015 onward. This is also a general concept referring to collaboration within innovation processes, including partnerships between businesses, research institutions, and governments.

While the combination of “open innovation” and “energy recovery” appears much more rarely, in 57 publications, of which 40 were published during the recent years. Adding more specific energy recovery technologies, such as combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, or landfill gas recovery, reduces the number of results even further. For example, “open innovation, energy, gasification” is only 5, while “open innovation, energy, landfill gas recovery” is only 3. Since the number of results was relatively small for the combination of “open innovation” and specific recovery technologies of energy, in this study, consideration was given to the keywords without the two where the number of publications was the highest, “open innovation” and “energy recovery”.

In the analysis of energy recovery processes, they were divided into five main groups according to the literature [8,9]:

- combustion;

- gasification;

- pyrolysis;

- anaerobic digestion;

- landfill gas recovery.

The categorization of energy recovery processes into the five main categories of combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery was chosen because each represents a distinct technological approach to extracting energy from waste materials. These categories are based on fundamental differences in the chemical and biological mechanisms involved, the types of waste they can process, and the forms of energy they produce. The classification relies on the basic principles of each process, their technological applications, and types of waste for which they are intended. It provides a systematic approach to the analysis of energy recovery methods and gives the opportunity to compare the efficiency, environmental impact, and suitability for different streams of waste. Each of these processes will be described in further parts of the paper.

In the case of open innovation in the analysis in this paper, it is divided into three types [10,11,12]:

- outside-in open innovation (inbound knowledge flow);

- inside-out open innovation (outbound knowledge flow);

- coupled open innovation (combining inflows and outflows).

The division of open innovation into three types was used in the paper because it provides a structured framework for analyzing the different ways knowledge flows across organizational boundaries. This classification helps to distinguish the various mechanisms through which firms engage in open innovation and leverage external and internal knowledge resources. By employing this classification, the paper is able to analyze open innovation more systematically, highlighting the different strategic approaches organizations can adopt when engaging in open innovation practices. This division also provides a clear analytical framework for understanding how firms integrate external and internal knowledge flows to enhance their innovation potential. In the following part of the paper, there is a more detailed characteristic of those types of open innovation.

3. Literature Review: Energy Recovery Technologies and Open Innovation

Despite the fact that this paper relies completely upon the structured analysis of the existing literature, this section represents the essential literature review that forms the empirical and conceptual basis of the subsequent analytical and interpretative phases of the paper. In Section 3, the status of the art in energy recovery technology and the characteristics of innovations related to the technology will be synthesized through the use of peer-reviewed articles indexed in the Scopus database. In this section, rather than merely performing an essential descriptive analysis of the literature, the results will be systematically analyzed through categories of technology types and characteristics related to innovations so that patterns of convergence and divergence within the literature will become distinguishable. These results will then be employed for the analysis of open innovations in Section 4 and Section 5.

Energy recovery basically means the process of collecting energy that otherwise will be dissipated to the surroundings, mainly produced from various industrial processes, electricity generation, and waste management, among others. The concept of energy recovery is an important evolution factor in current energy efficiency improvements and sustainability perspectives. There is a range of methods of recovering energy, which include mechanisms applied within their field. Recovery of waste of heat is one of the methods of energy recovery. Most of such processes result in massive generation of surfeit thermal energies which could also have been exploited towards raising the overall efficiencies of the energies applied. Through means such as recovery steam boilers, the system retrieves the surfeit thermal energies into useful energetic states, either purely electric or vaporized steam applicable to heating tasks. Another possible example could be waste heat utilization in some of the electric stations that could serve for the preheating of the input water and hence would decrease the energy input of the whole process [15,16,30].

The most efficient method could be energy recovery from the waste that can be realized through anaerobic digestion. It represents a biological process where organic materials are decomposed without the influence of oxygen, and biogas is its by-product. The main composition of biogas is methane, which can be recovered for use as a renewable energy vector, supplying heat, generating electricity, or even serving as fuel in vehicles. In the same way, this technology provides ways to recover energy through organic waste management, hence contributing to the circular economy [31,32].

Energy recovery can be done through the realization of energy in systems set up to capture kinetic energy at deceleration and store it. Examples are some in-transit public systems and electric vehicle regenerative braking systems. When the car brakes, the kinetic energy generated is usually dissipated as heat; these systems convert kinetic energy into electrical energy, which is stored in batteries for later use to assist the efficiency of the vehicle’s overall energy use [33,34,35].

Material recycling also serves as an avenue for energy recovery. Recycled materials from scrap metals and plastics can save energy up to several folds compared with producing new ones from primary sources. For example, aluminum recycling saves about 90% of the energy required for the production of aluminum from bauxite ore. This saves energy but also decreases the amount of greenhouse gas emission associated with the raw material extraction process. The concept is well explained by the gravitation potential that can be obtained, for example, in storage hydropower systems, where, due to pumping water to a greater height than naturally available, excess energy is reserved during periods of markedly low demand, and during peak times, water would be let through the turbine for electricity generation. This is quite an effective way of balancing demand and supply in energy grids, hence providing better reliability of energy supply [18,36,37].

Energy recovery itself forms part of the wider economy decarbonization and directly contributes to greenhouse gas emission reduction, energy efficiency, and sustainable best practices across various sectors. The urgency for the implementation of solutions to climate change requires a movement away from dependency on fossil fuels to more renewable sources of energy; hence, energy recovery is very relevant in this conversion process [25].

Energy recovery is key to decarbonization because of the potential it offers for waste reduction and further efficiency in energy systems. Most traditional methods of energy generation are characterized by massive energy losses mainly in the form of waste heat from industrial processes and the generation of electricity. It will go a long way in reducing overall energy demand from fossil fuels if recovered and reutilized, consequently reducing associated carbon emissions. In industries involving very high temperatures, waste heat recovery systems can be installed to cut by a big margin the amount of fuel required for operations, thus reducing carbon footprints. Recovery technologies, including anaerobic digestion, convert waste organics into renewable forms such as biogas-producing on-site fuel and electrical power. In not creating methane from landfills—a very powerful GHG—while providing a renewable fuel resource that displaces fossil fuel resources for space heating and producing electrical energy, there lies a possible advantage in the mitigation process. Energy recovery will be one of the key solutions to moving towards a low-carbon economy because, at some stage, it will involve the recycling of resources, making waste minimal through processing of waste material into valuable energy resources and, furthermore, decreasing energy sources that are carbon-intensive [38,39,40,41].

Another aspect of energy recovery is to complement integrating renewable sources into the energy mix. While the world faces the growing dominance of wind and solar installations, storage technologies, such as pumped hydro, will also begin to take solid steps in making headway with intermittence in renewable energy generation. Energy recovery, within its function to store excess renewable energy during times of low demand and release energy during times of peak load, can indeed be used toward grid stabilization to provide reliable energy. This not only encourages more renewables to penetrate the energy mix but also helps move away from fossil fuel-based energy systems—a major contributor toward decarbonization.

Energy recovery provides an impetus for technological innovation and economic growth in the clean energy sector. Energy recovery technologies create new business opportunities and jobs in industries that will drive improvement in energy efficiency. It would be possible for innovation in both the development and deployment of Energy Recovery Systems to improve and reduce the overall cost of this technology enable clean energy options to be both more feasible and appealing. A very important economic perspective is taken here—for decarbonization, huge investments are required, with collaboration between the public–private sectors in that regard [41,42].

Energy recovery helps ensure energy security: it reduces dependence on imported fossil fuels by increasing efficiency, utilizing local waste streams and, thus, increasing the energy self-sufficiency of the country to disturbances in the markets and geopolitical tensions. This might be particularly relevant under a decarbonization perspective, since it contributes to more general goals related to sustainability and self-sufficiency.

Recovery of energy from waste is one of the major options for energy generation with a reduced environmental impact, which could help in ensuring sustainable energy supply. The main existing technologies of energy recovery include combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery; various mechanisms are concerned with the energy extraction from waste [33].

Combustion, as it is normally referred to, is among the oldest methods employed in energy recovery. It involves the complete oxidation of waste at high temperatures usually in excess of 800 °C, in the presence of oxygen. Thermal energy produced during this process is normally utilized to generate steam to drive turbines for electricity production. Modern W-to-E plants incorporate state-of-the-art emission control technologies that reduce the emissions of harmful pollutants like dioxins, furans, and NOx. Although combustion is effective in volume reduction in waste and energy recovery, its application is usually opposed due to possible environmental impacts, especially greenhouse gas emissions [43,44].

Gasification is a thermochemical process that converts carbonaceous materials into a synthesis gas, mainly composed of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane. Unlike combustion, gasification takes place in an oxygen-deficient environment in a controlled manner; the temperature generally ranges from 700 °C to 1500 °C. The resulting syngas has direct application in gas turbines for electricity production and can be converted further into synthetic fuels such as methanol and hydrogen. The process is, in general, considered more environmental than incineration since less air pollutants are produced, together with more alternatives for energy recovery [35,45]. Pyrolysis, on the other hand, represents another thermo-chemical process that involves organic material decomposition in an oxygen-free atmosphere at temperatures in the range 300–800 °C. The products include solid biochar, liquid bio-oil, and gaseous products of pyrolysis, which all can serve for energy usage. Biochar can be utilized as an ameliorant for soils to increase the agricultural output, whereas bio-oil itself is a precursor for biofuel. The gases mostly consisted of methane and hydrogen; they again can effectively be used in producing heat and electric power. Pyrolysis has some advantages in the treatment of biomass and plastic waste, offering an alternative route to convert waste into energy carriers with a lower emission factor than direct combustion.

Anaerobic digestion is a biological process in which organic matter is degraded with the help of metabolic activities in the absence of oxygen, carried out by microorganisms and giving rise to biogas, which principally contains methane and carbon dioxide. This process generally occurs in digesters designed for that purpose at mesophilic 35–40 °C or thermophilic 50–60 °C temperatures. Biogas produced can be used either for heating, electricity generation, or upgraded to biomethane for injection into natural gas grids. The remaining digestate is rich in nutrients and acts like organic fertilizer. Anaerobic digestion finds its wide applicability in the treatment of agricultural residues, food waste, and sewage sludge with the recovery of energy and waste management [46,47]. Energy recovery as landfill gas recovery involves the recovery of methane produced by anaerobic decomposition of organic waste in landfills. Over time, the waste decomposes and produces landfill gas through microbial action; it is usually composed of 50–60% methane with the remainder being carbon dioxide along with trace gases. This gas can be extracted by collection systems including wells and piping networks and then used either for electricity production or heating applications, or further purified into renewable natural gas. If this is not recovered, then the landfill gas will be released to the atmosphere, creating massive greenhouse gas emissions. Controlled landfill gas capture thus supplies energy while reducing environmental impacts [19,31,32].

All these processes of energy recovery reduce fossil fuel consumption and further provide workable solutions with respect to waste management in a sustainable manner. Their choice and application depend on waste composition, energy demand, and environmental regulations, defining the feasibility and efficiency of each method. Ultimately, the integration of such technologies will take societies toward a circular economy wherein the waste becomes an asset for the production of energy rather than being a liability.

The various energy recovery processes can be listed as combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion, and landfill gas recovery. Below is Table 2, detailing different energy recovery processes. Identifying applications that are typical of each process will be shown on the table below.

Table 2.

Energy recovery processes.

Energy recovery is a component of sustainable development and energy efficiency across many industrial sectors (Appendix A Table A1).

Although the above-described energy recovery processes differ substantially in terms of technological principles, feedstock requirements, and environmental profiles, they share a common set of innovation-related challenges. These include incremental efficiency gains under conditions of technological maturity, growing pressure to reduce emissions beyond regulatory minima, difficulties in scaling solutions across heterogeneous waste streams, and increasing system complexity resulting from integration with broader energy infrastructures. Addressing these challenges increasingly exceeds the capacity of isolated, firm-centric R&D approaches and requires access to complementary knowledge, cross-sectoral expertise, and shared experimentation environments. From this perspective, energy recovery technologies constitute not only technical systems, but also socio-technical configurations whose further development depends on the structure of knowledge flows, collaboration mechanisms, and governance arrangements. This creates a natural conceptual bridge toward open innovation, which offers a structured framework for understanding how external knowledge sourcing, internal knowledge dissemination, and collaborative co-development can shape the evolution, performance, and societal acceptance of energy recovery systems.

4. Open Innovation in Energy Recovery

In the current study, open innovation refers to the deliberate and concerted application of knowledge inflows and outflows across organization boundaries with the aim of fast-tracking innovation as well as enhancing technological and system-level performance [14,17]. Unlike the traditional approach to innovation in the energy recovery sector that was hitherto marked by in-house engineering development and supplier-driven equipment development and process optimization within firm boundaries—open innovation integrates external parties such as research organizations, technology firms, the regulating authority as well as public organizations into the innovation process [53,54]. The critical point to note concerning open innovation in this argument is that it is not the collaboration but the application of external knowledge that characterizes the approach and has long been practiced in the energy recovery sector [14,21].

This divide has become especially pertinent in the context of energy recovery, where innovation challenges have started to extend beyond mere optimization, focusing on the reduction in emissions, integration, and regulatory compliance [2,15,16]. In most innovation endeavors, these challenges have traditionally been handled sequentially, in organizational silos, either focusing on internal innovation capabilities or supplier contracts. With open innovation, all these challenges can actually be accomplished in a parallel manner, leveraging diverse innovation capabilities available across the innovation ecosystem, including public institutions [20,22]. This, therefore, means open innovation in energy recovery, compared to conventional innovation, occurs not merely in degree, by a logic and a governance divide, transforming innovation practices from a closed, company-focused innovation to a system-level innovation [14,17].

Open innovation is a collaborative approach wherein external ideas, technologies, and expertise are utilized to advance innovation and problem-solving within organizations. This model runs in contrast to the traditional, internally driven closed innovation processes that rely solely on internal resources and knowledge bases. In relation to energy recovery, open innovation offers a number of potent advantages that are able to further develop and implement effective technologies and strategies of recovery [5,6,14,21].

It could be identified that there exist three types of open innovations, including outside-in open innovation, inside-out open innovation, and coupled open innovation. Different approaches to knowledge and resource exchange can be involved between the organizations and their external stakeholders. These models have further facilitated ways in which firms draw on external knowledge, share their internal innovations, or synergize with other sources of development for progress [17].

Open innovation or inbound knowledge flow in an outside-in process simply means integrating the knowledge, technologies, and ideas from outside into the firm’s internal processes of innovation. A company opens up to customers, suppliers, research institutions, universities, startups, and even competitors as an opportunity to boost internal innovation. This is where external expertise can give a firm a leap in terms of accelerating the process of research and development and shortening the time to market to develop its competitive advantage. The methodologies normally associated with this form of open innovation include crowdsourcing, technology scouting, corporate venture capital, and collaborative research projects [53,54,55].

Inside-out open innovation could be called outbound knowledge flow, a process when a firm actively externalizes its internal knowledge, technologies, and intellectual properties to others. Instead of retaining all the innovations within the corporation, firms can also commercialize or share the knowledge with others through various licensing agreements, spin-offs, technology transfers, or strategic partnerships. This will, in turn, enable companies to commercialize non-core innovations, reach wider markets, and even participate in the creation of whole industries. A very good example is IBM, which has embraced open-source software development and made a large part of its patents available to stimulate collaboration and innovation across industries [56,57,58].

Coupled open innovation, as the term itself suggests, couples the inbound and outbound knowledge flows together into a hybrid. In such an approach, deep collaborations happen wherein a firm codesigns innovations together with external partners, and all gain jointly. Most often, such open coupled innovations take forms such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, innovation ecosystems, or even co-creation initiatives [20,59]. These could be a combination of internal competencies and external resources that allow firms to develop breakthrough innovations jointly while sharing risks and rewards. Probably the most powerful example of coupled open innovation is in the automotive industry, where manufacturers, suppliers, and technology firms join hands to create next-generation vehicle technologies in electric and autonomous driving [22,60].

The energy recovery challenges are complex and many times interdisciplinary; therefore, they require a number of different perspectives and skill sets. Companies can take advantage of a wider knowledge base with more creative ideas through collaboration with external partners such as startups, academia, research organizations, and even other industries. It is a thought-provoking environment in which creativity is promoted, and it allows organizations to start looking at energy recovery in ways they might not have considered before [38,47,61,62,63]. For example, the intersection of knowledge in material sciences, environmental engineering, and technology could result in either the elaboration of new and more efficient heat exchangers or in new ways of producing biogas. Another dimension of open innovation in energy recovery pertains to the speed at which technology has started changing [39,44]. The energy sector is one of the ones that are moving really fast. This can be done in collaboration with external entities that may introduce the organization to the latest research, tools, and methodologies to help in improving their activities concerning energy recovery [40]. This acceleration is very important in a landscape where timely implementation of energy-efficient solutions becomes crucial regarding tackling climate change and fulfilling regulatory requirements. Secondly, a partnership ensures the sharing of resources, hence reducing costs related to research and development and facilitating the expedient delivery of organizational innovative solutions within the marketplace [41,42].

Excerpts of such an open culture of innovation allow for more experimentation and risk-sharing. Engaging with external innovators, these organizations can test new energy recovery technologies or methods without bearing complete risk, generally associated with projects developed in-house. This may result in much higher investments being made in innovative projects, leading to driving even more efficiency in the methods applied for energy recovery. For example, energy companies can enter into a relationship with tech startups to pilot the advanced sensor technologies for waste heat recovery process monitoring, continuously improving without immediate financial risk [64,65,66].

Open innovation can promote better stakeholder involvement and increased social acceptance of energy recovery initiatives. Collaboration with local communities, governmental bodies, and non-profit organizations will assist organizations in making their energy recovery strategy meet societal needs and expectations [18,67]. This also develops public support for projects, smoother regulatory approval processes, and effective communication on the benefits deriving from energy recovery. It is expected, therefore, that better implementation and application of systems and technologies regarding energy recovery can come out along with increased investment in sustainable practice [18,68].

Open innovation can be useful in letting the organization identify and tackle the energy recovery barrier. The wide variability of stakeholders will provide insight into regulatory hurdles, market constraints, and technical challenges that may lie in the way of appropriate energy recovery solutions [69,70,71,72,73]. Working with external partners who have experience in overcoming similar obstacles will thus allow organizations to devise more robust strategies toward such challenges. This adaptability is vital in the energy industry, with fluctuating policies and market dynamics [7,74,75].

4.1. Combustion Energy Recovery

Open innovation may help in carving a multi-faceted approach to the improvement of combustion energy recovery internal capability by building external competence. In this regard, combustion energy recovery has been implemented by combusting waste and several fuels to develop heat for generating electrical energy. The integration of open innovation here can lead to great improvements pertaining to efficiency and emission reduction related to overall performance [33].

Examples include outside-in open innovation—seeking to complement combustion processes through the integrating of external ideas, technologies, and research results. Outside-in open innovation applied to the field of combustion energy recovery may entail industry–university interaction, specifically by companies joining hands with highly acknowledged universities or even dedicated research centers in establishing innovative algorithms of control in various kinds of combustions or with regard to investigation within a bank of new catalytic materials meant for further enhancement of combustion [41,76,77]. Diffusion of such breakthrough innovations in everything from new sensor technologies to data analytics, which enable real-time monitoring and optimization of combustion parameters by tapping into a larger knowledge base, will contribute to enhanced energy conversion efficiency and also meet both economic and environmental goals by reducing harmful emissions [78,79].

Inside-out open innovation is a process where an organization prioritizes the flow of internal innovations outside, in particular sharing proprietary technologies or process improvements it has generated with external partners and the greater marketplace [80,81]. Large organizations, through investing in significantly new combustion technology—development of burner design with remarkably improved low emission performance or perhaps even entirely new system design for effective heat recovery—can license either other participants from the energy sectors or even downstream industries [82,83,84]. Clearly, licensing expertise from within them through appropriate joint ventures and/or strategic partnering allows diffused technology standardization of enhanced performance combustion on a wider scope. This way, licensing of internal breakthroughs may allow companies to set, besides new sources of revenues, an industry-wide benchmark of efficiency and environmental performance, opening pathways toward a sustainable and competitive energy marketplace [85].

Coupled open innovation refers to the symbiotic integration between the inbound and outbound flow of knowledge. This model in essence defines the cooperation relationship whereby related internal and external stakeholders interact among themselves for ecodevelopment [86,87]. In Combustion Energy Recovery, this may be interpreted as the leading energy company co-creating integrated systems with technology startups, research institutions, and regulatory bodies to solve a complex set of challenges around fuel combustion optimization, pollutant emission minimization, and waste heat recovery for further energy production [88,89]. The workshop will bring together all participants in the development process of robust combustion systems that are adaptive to changing fuel qualities and other operational conditions. In coupled open innovation, the collaborative process accelerates the pace of development and deployment of state-of-the-art combustion technologies, while providing a guarantee that the solutions developed will be economically viable and environmentally sustainable [90,91].

In this respect, the workshop needs to be considered as part of an arranged collaboration space within the frame of the open innovation process. Primarily, it acts as a coordination tool where the aim of the meeting is to align the various actors involved in the system development process such as the technology supplier, energy recovery operator, researcher, regulator, and system integrators. The workshop allows the participants to translate the system necessities as well as their tacit knowledge into design parameters concerning the combustion system through interactive collaboration.

From a process viewpoint, the workshop can be considered a boundary-spanning arena, where external and internal knowledge streams enter a joint process of recombination. The technical sessions of a workshop enable knowledge sharing for data on fuel variability, combustion characteristics, emission performance, and control methods, whereas strategic sessions cover problems pertaining to economic viability, scaling, and government regulations. In other words, through workshops, scientists can assess together the trade-offs involved in increased efficiency, emissions, and economic costs, thereby avoiding the creation of technologically more advanced but economically or institutionally unviable alternatives.

At the same time, it should be noted that the workshop is a very important component for speeding up the pace of innovation, reducing the time for feedback cycles involving system design, testing, and validation. The early-stage joint assessment of design options helps quickly detect potential problems connected with fuel quality variability, system operation, or regulatory limits. This, in turn, means that the development of combustion technologies within this collective environment can increase the chances of these developments being adaptive, robust, and matched with the conditions of actual operation, and this, in turn, helps the workshop be a governance tool for open innovation, enhancing, through this process, the chances for achieving economic viability and environmental sustainability at the same time.

Open innovation, in all its dimensions, provides the ability for combustion energy recovery contributing companies to be more resilient and adaptive in terms of their technological infrastructure. It is about integrating outside innovations into your company via outside-in strategies for continuous process control and efficiency improvement, while dissemination of inside-out internal approaches allows for progress and standardization of the whole industry [92,93,94]. These strategies involve open innovation couplings for the assurance of a dynamically collaborative ecosystem-driving breakthroughs with energetics enabled to be sustainable [95,96,97]. Thus, from this point of view, open innovation is strategically applied and results in superior energy production by the best means and with environmental performance adding values to transitions of the globe toward clean and efficient systems of energy generation [38,43,44,98].

Appendix A Table A2 explains how open innovation can be applied in developing the combustion energy recovery processes, dealing with outside-in/inbound knowledge flow, inside-out/outbound flow of knowledge, and coupled open innovation.

Outside-in innovation in an open innovation model performs best in a state of technological maturity as a consequence of regulatory force. As the basic thermodynamic knowledge surrounding combustion technology has now matured, incremental improvements in performance are necessarily contingent upon expert knowledge from outside the industry in areas such as advanced materials science, digital control systems, and emission measurement technology. Outside-in innovation strategies maximize their profitability in those corporations that possess the absorptive capacity for structural modifications that combine knowledge from outside with existing knowledge. Outside-in innovation is most applicable in an existing industry structure where corporations are presently functioning near the limits of existing best technology and looking for incremental improvements.

Coupled open innovation in combustion technologies often results in a number of coordination and governance pitfalls. Close collaboration with regulators, equipment manufacturers, and research institutions often results in extended development cycles and blurred accountability. Furthermore, once collaborative arrangements codify emission standards prematurely, firms may be subject to regulatory lock-in, reducing the likelihood of technological flexibility beyond these arrangements. This is particularly salient in combustion, where requirements for compliance change more quickly than the life span of installed assets. Because of this, coupled innovation must be designed with careful forethought in order to maintain technological optionality, or else collaboration may inadvertently stabilize suboptimal solutions rather than allow for transformative change.

4.2. Gasification Energy Recovery

Open innovation, especially in techniques such as gasification energy recovery—a process of converting organic or fossil-based material into syngas for the production of energy—can ensure huge advancements regarding efficiency, sustainability, and effectiveness.

Outside-in open innovation in the context of gasification energy recovery may involve partnerships with research institutions, universities, and innovative technology startups. In this case, for instance, a gasification company might collaborate with a university that has a specialty in advanced material science to develop new catalysts that would serve to improve the efficiency of syngas production [99,100,101]. By integrating these advanced materials into the gasification systems, the company can achieve better conversion rates from various feedstocks, such as agricultural waste, municipal solid waste, or industrial byproducts. Besides this, partnerships with technology companies that have expertise in data analytics and machine learning will empower gasification plants to deploy real-time monitoring systems that optimize operational parameters, reduce downtime, and maximize energy output. The outside-in approach opens several doorways for the company to external knowledge and expertise, placing it at the top of the developments in gasification technology [18,102].

Inside-out open innovation enables companies to license their proprietary technologies, methodologies, and knowledge for wider implementation and use of efficient gasification processes. For example, it would mean a company that spent time and effort to develop an advanced gasification technology would license its patents to waste management firms or energy providers, especially in countries where access to clean energy is limited [103,104]. This, in turn, enables the technology to be installed at various sites of application to convert waste into renewable energy and contribute toward local energy security [105,106]. Apart from this, knowledge transfer activities such as workshops or webinars can be organized by organizations to share best practices and operational knowledge related to the gasification processes. This does not only over time build a reputation for the company of origin as a thought leader in this respect but also fosters sector-wide innovation that encourages others to adopt similar technologies and methods [35,45,107].

Coupled open innovation is the model that syntactically embeds both inbound and outbound knowledge flow. The model provides for collaboration across organizations: gasification companies, manufacturers of equipment, regulatory agencies, and environmental groups [107,108,109]. As such, for example, gasification firms might form an alliance with a government department to co-develop standards to control new emissions in gasification systems. In cooperation, they can both realize that their respective expertise in the optimization of energy recovery and in fulfilling or surpassing regulatory requirements come together to provide solutions [108,109,110]. The partnership will see new gasification technologies developed that incorporate advanced filtration and scrubbing systems leading to better environmental performance and greater public acceptance. Furthermore, coupled knowledge flows can create an enabling environment where innovation can thrive. This is achieved by carrying out joint research projects in exploring new feedstock options, better reactor design, and testing of integrated systems incorporating gasification combined with other renewable energy systems such as anaerobic digestion or biomass combustion [111,112,113,114].

Appendix A Table A3 presents an overview of how open innovation on gasification energy recovery could be applied based on outside-in, inside-out, and coupled open innovation. Each option provides a description of how such processes would contribute toward improvements in the gasification processes.

Outside-in open innovation pays off most in gasification when technological uncertainty remains high, but modular innovation opportunities exist. Variety in feedstock, reactor design, and syngas quality interact in complex ways within gasification systems and external expertise can be especially valuable during the early and intermediate technological development stages. Outside-in approaches pay off especially when complementary competencies—for instance, catalysis, process modeling, or digital optimization—are contributed by external partners rather than generic technological inputs. Effectiveness does tend to decline, however, when fragmentation of external knowledge inflows or misalignments with plant-specific operating conditions drive up integration costs beyond the gains in performance.

Coupled open innovation in gasification faces structural challenges related to risk allocation and control of intellectual property. Coupled innovation ventures may obscure process know-how ownership, which plays a crucial role in the competitiveness of gasification innovation. Secondly, gasification ventures fundamentally require huge capital outlays, thereby posing asymmetrical risk to innovation partners. This situation may hinder coupled innovation if there are different risk perceptions. Coupled innovation in the gasification sector can, therefore, be successful if the innovation partners have similar time horizons, investment capabilities, and regulatory risks.

4.3. Pyrolysis Energy Recovery

It is outward-looking, benefiting from partnerships with top academic institutions, research organizations, and technology start-ups. Outside-in open innovation may be particularly relevant for a pyrolysis energy recovery firm. As an illustration, imagine a pyrolysis firm partnering with a university that has a highly regarded reputation in catalysis to jointly work on catalysts which enhance yield and quality of the bio-oil produced in the pyrolysis process [47]. This would contribute to better process efficiencies in the company for having more energy from the same feedstock, whether agricultural waste, plastics, or other organic materials. Additionally, it will be important to identify the right startups engaging either in process optimization or digital monitoring, which can be a great way to achieve smart systems able to continuously analyze data from operations and make adjustments in real-time to maximize production efficiency while reducing emissions at any pyrolysis facility. This approach would be helpful in bringing progress for the two technologies while enabling the pyrolysis company to stay competitive during shifting energy use scenarios [19,36,115].

Inside-out open innovation can assist in the diffusion of the application of companies’ proprietary technologies, methodologies, and insights in effective pyrolysis processes. For instance, a company may license the new design for the pyrolysis reactor to waste management companies or other industries that would like to apply a sustainable approach within the context of waste-to-energy production [34,35,116,117]. This way, the technology can be installed for various uses, such as waste to renewable energy, aiding in waste management and sustainability. Outreach could be in the form of workshops or published research findings that one organization provides in order to share best practices and operational knowledge regarding pyrolysis. These initiatives boost the company’s status as an industry leader but also drive innovation across the sector by encouraging others to implement similar technologies and practices, thereby contributing to wider improvements in energy recovery from waste [18,37,118,119].

In this instance, coupled open innovation in pyrolysis energy recovery can be explained as collaboration between companies in pyrolysis, equipment manufacturers, environmental organizations, and regulating agencies. For example, a pyrolysis company may co-develop with a governmental agency the emission control and product quality assurance for pyrolysis processes [120,121,122,123]. This can be developed in this case by the combination of both parties’ respective competencies, developing solutions that result in optimum energy recovery, as well as full compliance with the regulatory regime [124,125,126]. It allows for innovative pyrolysis technologies with integrated, advanced filtration and scrubbing systems that minimize harmful emissions and make the process more viable and sustainable [35,127]. Coupled innovation therefore creates a networked ecosystem in which knowledge can be shared and co-developed. This could include informing about new feedstock options, advanced reactor design, integrating systems containing pyrolysis with other renewable energy conversion technologies, such as anaerobic digestion or gasification—all through cooperation in research activities [128,129].

Appendix A Table A4: How open innovation could be applied to pyrolysis energy recovery using outside-in, inside-out, and coupled open innovation approaches. Each entry describes how this type of innovation enhances pyrolysis processes.

For pyrolysis-based energy recovery, outside-in open innovation can be considered most effective in heterogenous feedstock and instable process environments. Knowledge inflows from outside, especially from materials science, catalysis, and process control knowledge, can help companies adjust pyrolysis technology according to different waste feeds, and increase the selectivity of products. Outside-in innovation will be most effective for companies if they orchestrate the knowledge integration process actively rather than adopting outside-in approaches for passive solution-seeking. Without this activity, outside knowledge can optimize different subprocesses independently but will not be able to remove inefficiencies in the system.

Coupled open innovation in the case of pyrolysis can be limited by an imbalance between innovation experiments and regulatory requirements. Regulations concerning pyrolysis tend to be in a middle regulatory position, often failing to fit neatly into either waste or energy regulation. Public–private innovation can increase legitimacy, but it could also have a limiting effect on innovation experimentation, which might lock process parameters into a predefined pathway. Moreover, coupled innovation could increase coordination costs, especially when there are conflicting requirements to ensure environmental protection and viability. It appears, therefore, that coupled innovation in the case of pyrolysis must initially emphasize adaptive innovation regulation mechanisms to enable learning.

4.4. Anaerobic Energy Recovery

Anaerobic digestion is characterized by the conversion of organic matter by microbial activities into biogas in the absence of oxygen. In addition, this process has to gain much from developing new strategies dealing with operational difficulties, efficiency of processes, and increased application perspectives. Companies in the industry can also make use of more open strategies of innovation, either by licensing in external ideas, licensing out internal breakthroughs, or even the creation of collaborative ventures that harness both inbound and outbound knowledge flows in the creation of a more sustainable and economically viable renewable energy solution [31,32].

This means open innovation outside-in, whereby a company collaborates with microbiologists and bioengineers in the discovery of new microbial strains or optimization of existing consortia for the improvement of the rate and yield of biogas produced from various feedstocks [130,131]. It would also be supported in the development of an integrated sensor technology with advanced data analytics from third-party experts who could enable real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance to ensure that digesters work at their optimum level and experience less downtime. These continuous inflows of third-party knowledge expedite the pace of technological enhancement but allow businesses to be responsive to ever-evolving environmental requirements and market conditions for stronger, more powerful ways to achieve energy recovery [19,132].

Inside-out open innovation—in anaerobic energy recovery, the companies are allowed to take advantage of internally developed technologies, process improvements, and operational best practices through licensing, research output sharing by publication and conference presentations, or even strategic alliance with industry peers [133,134]. Companies open up and share successful innovations, such as new reactor design, better ways of biogas upgrading, or more efficient feedstock pretreatment, contributing to a wider dissemination of sustainable technologies. It develops new revenue sources to strengthen market position [135]. This strategy will be part of creating an enabling environment concerning innovation collaboration, building potential, and contributing to the fast deployment of anaerobic digestion along the diffusion in overall renewable transitions to come more rapidly into everyday application [34,35,136].

Coupled open innovation enables different partners to come together and combine skills for tackling specific complex challenges resulting from anaerobic digestion: improvement of the conversion efficiency of a variety of organic waste, process stability management in variable operating conditions, and environmental impact reduction upon the digestate disposal. For example, one leading anaerobic digestion company, one engineering university, even one governmental environmental agency may be involved; these partnerships could work within integrated systems to realize the maximum of biogas production with mechanisms related to advanced emissions control and nutrient recovery. The program will create an environment where joint ventures, through the sharing of knowledge and resources, will be continuously developing innovations that promise adaptable and scalable solutions across the board in a wide range of settings and applications [137,138,139,140].

Appendix A Table A5 describes how open innovation can be applied to anaerobic digestion energy recovery: outside-in, inside-out, and coupled open innovation approaches. Each filling in the table describes how every type of open innovation supports enhancements in anaerobic digestion processes.

Outside-in open innovation is effective in anaerobic digestion, especially when biological complexity outperforms internal expertise. Most microbial optimization and feedstock preprocessing depend on advanced biological knowledge and data analytics that reside outside traditional energy firms. For instance, the use of outside-in methods to overcome crucial bottlenecks, such as process stability or methane yield variability, produces great returns. Meanwhile, dependence on inside-out biological solutions without any ways of learning internally reduces long-term organizational competence, developing dependency rather than capability.

The coupled open innovation of anaerobic digestion is prone to organizational inertia and path dependence, in particular, with regard to municipally embedded systems. The collaboration between utilities, agricultural actors, and regulators often cements instead of challenging existing operational routines. Additionally, the diverging goals of key stakeholders (energy production, waste treatment, nutrient recovery) dilute an innovation focus. Consequently, coupled innovation will express its full potential only in those constellations where it explicitly targets system-level optimization rather than incremental operational improvements and governance mechanisms provide checks against dominating positions of a single type of stakeholder.

4.5. Landfill Gas Energy Recovery

Landfill gas energy recovery is the collection of methane and other gases generated by anaerobic decomposition of organic waste in landfills and conversion to a usable form of energy. Landfill gas energy recovery, in a business perspective, can engage an academic institution, research center, or technology start-up for access to advanced gas monitoring systems, better methane conversion techniques, and innovative sensor technologies through outside-in open innovation. These collaborations, especially with the research organizations focused on environmental engineering, will lead to the development of advanced real-time monitoring systems that can accurately analyze the composition of the landfill gas [141,142,143]. Therefore, external expertise can only create better conditions for optimizing the process of capturing gas and generally improving efficiency in energy-converting systems. Also, companies contribute to a cleaner environment with integrated external novelties, not only improving operational performance but also reducing the amount of greenhouse gas emissions [144,145,146,147].

In the opposite direction, inside-out open innovation would comprise those firms that have reached efficient landfill gas extraction techniques or processes for gas purification through the sharing or licensing of such an innovation with other companies, utilities, or public institutions. The opening up of achievements in internal research and development to outside actors provides wider perspectives on the uptake and standardization of successful experiences at the level of the entire sector [148,149,150]. The flow of knowledge in this direction may contribute not only to more sources of revenue via licensing agreements or collaborative ventures but also create a shared learning and continuous improvement environment. This again leads to the faster dissemination of best practices and proven technologies that are very conducive to a more competitive and sustainable market for renewable energy solutions derived from landfill gas [116,151,152].

Coupled Open Innovation: The model provides for the joining of forces between companies operating in the waste management market, technology developers, regulatory bodies, and academia. The partnerships combine diverse knowledge pools in an effort to address strategic challenges with respect to efficiency optimization in gas capture and reduction in impact on the natural environment. Such a project might involve the collaboration of a leading landfill gas recovery company, an environmental technology firm, and a government agency in the co-development of an integrated system [153,154]. This could include the integration of advanced sensor technologies, innovative gas processing techniques, and regulatory insight into a superior and more sustainable energy recovery system. In fact, the very co-creative process accelerates technological development itself to achieve the technology leap forward; it enables the creation of industry-wide standards and practices for common benefit, thus achieving more speedily the low-carbon economy and energy regime [18,70].

Appendix A Table A6 shows the possibility of open innovation in the context of energy recovery from landfill gas. This involves three open innovation types, including outside-in, inside-out, and coupled, in explanation of landfill gas recovery enhancement.

Outside-in open innovation in the area of landfill gas recovery works best in an environment in which there is a standardization of technologies on one hand and the uncertainty associated with environment and data monitoring on the other. This is because the central technologies in gas recovery have reached a relatively mature stage and therefore the only area in which improvement can be made by having more advanced sensing and forecasting technologies.

The coupled innovation in the recovery of landfill gas may be characterized by institutional complexity and slow decision-making processes. This collaboration among the parties involved—such as the landfill company, the technology company, and the public authority—can be very formalized, which inhibits innovation. The long lifespan of the involved assets and a low level of public awareness make it less attractive to engage in radical innovation. Therefore, innovation can be seen as procedural innovation. The effectiveness of innovation relies on the ease of incorporating innovation goals into contractual frameworks.

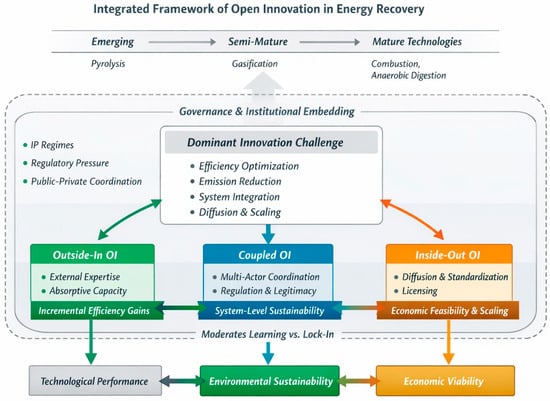

4.6. Synthesize Cross-Cutting Insights