Abstract

The increasing penetration of electric vehicles (EVs) and rooftop photovoltaics (PV) is intensifying the variability and uncertainty of residential net demand, thereby challenging real-time operation in smart grids and microgrids. The purpose of this study is to develop and evaluate an accurate and operationally relevant short-term forecasting framework that jointly models household net demand and EV charging behaviour. To this end, a Residual-Normalised Multi-Task GRU (RN-MTGRU) architecture is proposed, enabling the simultaneous learning of shared temporal patterns across interdependent energy streams while maintaining robustness under highly non-stationary conditions. Using one-minute resolution measurements of household demand, PV generation, EV charging activity, and weather variables, the proposed model consistently outperforms benchmark forecasting approaches across 1–30 min horizons, with the largest performance gains observed during periods of rapid load variation. Beyond predictive accuracy, the relevance of the proposed approach is demonstrated through a demand response case study, where forecast-informed control leads to substantial reductions in daily peak demand on critical days and a measurable annual increase in PV self-consumption. These results highlight the practical significance of the RN-MTGRU as a scalable forecasting solution that enhances local flexibility, supports renewable integration, and strengthens real-time decision-making in residential smart grid environments.

1. Introduction

The growing adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems, and smart home technologies is reshaping residential electricity demand [1,2]. These developments have introduced greater variability and reduced predictability, making short-term forecasting an essential requirement for maintaining grid stability, coordinating flexible EV charging, and improving local renewable utilisation [3,4].

Forecasts on the 1–30 min timescale are particularly important for operational tasks such as voltage regulation, congestion management, inverter control, and demand response (DR) activation [5]. However, household energy behaviour is influenced by multiple interacting factors, including appliance-driven fluctuations, behavioural routines, EV plug-in events, and weather-dependent PV generation [6,7,8]. These interactions create a challenging forecasting environment in which traditional models tend to struggle.

Recent research has increasingly focused on data-driven short-term forecasting methods to address the growing variability introduced by EV charging and distributed renewable generation. Deep learning (DL) architectures, including recurrent neural networks, convolutional-recurrent hybrids, and attention-based models, have demonstrated strong performance across a range of residential and urban-scale applications [3,5,9]. In parallel, several studies have explored joint or coupled modelling strategies to capture dependencies between demand, EV charging, and renewable generation, highlighting the benefits of multi-task and multi-output learning frameworks for improving predictive accuracy under non-stationary conditions [8,10]. These developments motivate the need for architectures that are both robust to rapid temporal transitions and capable of exploiting cross-variable structure in high-resolution residential energy data.

Classical statistical approaches, including autoregressive models, exponential smoothing, and state-space techniques, have been widely applied to residential load forecasting [11,12,13]. While effective under relatively stable conditions, they are not well-suited to the irregular, non-stationary, and multivariate characteristics of modern residential demand. Machine learning (ML) methods, such as support vector regression (SVR), random forests, and gradient boosting, offer enhanced nonlinear modelling capability [9,14,15]. Yet, they lack the sequential memory required to model temporal dependencies in high-resolution data.

DL methods have therefore become prominent for short-term load forecasting. Recurrent architectures, including long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent unit (GRU) networks, capture multi-scale temporal structure, while hybrid convolutional-recurrent and transformer-based models incorporate local feature extraction and global attention mechanisms [16,17,18,19,20]. Despite their advantages, most existing approaches predict net-load, EV charging, and PV generation independently, even though these quantities are physically and behaviourally linked [21]. Models that ignore these dependencies risk missing shared temporal patterns and cross-variable interactions that could enhance predictive accuracy.

These considerations highlight the need for forecasting methods that: (i) jointly model the interdependent components of residential energy behaviour, and (ii) provide stable and accurate predictions under highly variable operating conditions. To address this gap, this study proposes the Residual-Normalised Multi-Task GRU (RN-MTGRU), a unified framework for simultaneous forecasting of residential net-load and EV charging behaviour.

1.1. Related Work

Residential short-term load forecasting has been extensively studied using statistical, ML, and DL approaches, each characterised by distinct modelling assumptions and limitations. Traditional statistical methods such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), Kalman filtering, and exponential smoothing primarily rely on historical load observations and, in some cases, exogenous variables such as temperature [11,22,23]. These models typically assume linear relationships, stationarity, and slowly varying temporal dynamics. As a result, they struggle to represent abrupt changes caused by appliance switching, EV plug-in events, or intermittent PV generation, and they do not explicitly model interactions between multiple residential energy components.

ML-based methods, including support vector regression (SVR), random forests, k-nearest neighbours, and gradient boosting [9,14,24,25], relax linearity assumptions and allow a wider range of input parameters, such as weather variables, calendar features, and aggregated demand indicators. While these models improve nonlinear mapping between inputs and outputs, they typically treat observations as independent or weakly correlated samples. Consequently, they do not explicitly model sequential dependencies, thereby failing to capture how past system states influence future behaviour across consecutive time steps. This limitation is particularly restrictive for high-resolution residential data, where rapid temporal correlations and short-lived events are critical.

DL approaches have therefore gained prominence by explicitly learning temporal dependencies from sequential data. Recurrent neural networks, particularly LSTM and GRU architectures [16,17], model sequential dependencies by maintaining internal memory states that encode information from previous time steps. In the context of residential energy forecasting, this allows them to capture diurnal cycles, weekday-weekend patterns, and delayed responses to weather variations. However, most existing LSTM- and GRU-based models focus on single-output prediction tasks and typically forecast net-load, EV charging, or PV generation independently, without exploiting the physical and behavioural coupling between these signals.

Hybrid CNN-RNN models [18] introduce convolutional layers to extract short-term temporal motifs or local patterns before recurrent aggregation. While this improves sensitivity to local fluctuations, such models often require careful tuning of convolutional kernel sizes and still exhibit limited robustness under strong non-stationarity, particularly when input distributions shift due to seasonal changes or evolving household behaviour. Transformer-based architectures [19,20] address long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, enabling flexible weighting of historical observations. Despite their representational power, transformer models are computationally intensive, require large training datasets for stable convergence, and remain sensitive to distributional shifts in residential-scale datasets, where data availability is often limited.

Across these DL-based approaches, three key limitations remain evident. First, most models adopt a single-task formulation, predicting net load, EV demand, or PV output in isolation, despite strong correlations and causal interactions among these variables [21]. Second, robustness to non-stationarity is limited, as many architectures lack explicit mechanisms to stabilise hidden-state dynamics under changing weather conditions, seasonal effects, and evolving household routines [26]. Third, responsiveness to rapid transitions remains insufficient, with many models smoothing sharp load variations caused by EV charging events or sudden appliance activation [27].

The RN-MTGRU proposed in this study is designed to address these limitations by jointly forecasting residential net-load and EV charging behaviour within a unified sequence modelling framework. By combining multi-task learning to exploit cross-variable dependencies, layer normalisation to improve stability under non-stationary conditions, and residual refinement to preserve high-frequency temporal dynamics, the proposed approach advances beyond existing single-task and unnormalised recurrent models.

Beyond single-task forecasting, recent international studies have emphasised the importance of modelling interdependencies among residential energy components. Multi-task learning and multi-output neural networks have been applied to joint forecasting of load and renewable generation, EV charging demand, and flexibility potential, demonstrating improved robustness compared with isolated prediction approaches [3,9]. Transformer-based and attention-enhanced models have also been explored for short-term load forecasting at residential and city scales, offering improved representation of long-range temporal dependencies, albeit at higher computational cost [9]. These studies provide independent evidence that architectural design choices, rather than dataset-specific tuning, play a central role in achieving reliable short-term forecasting performance under heterogeneous operating conditions.

1.2. Motivation and Research Questions

Modern residential energy profiles are shaped by interconnected processes, including EV charging behaviour, household routines, and weather-driven PV generation. These interactions influence both short-term variability and longer-term patterns, making isolated forecasting of individual components suboptimal. A joint approach can improve predictive accuracy by learning a shared structure across related signals.

Building on this motivation, the present study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1: How can residential net-load and EV charging be forecast jointly to better capture shared temporal structure?

- RQ2: Do architectural enhancements that promote stable sequence modelling improve robustness under rapidly changing or non-stationary residential energy conditions?

- RQ3: What operational benefits can improved short-term forecasting provide for DR strategies, peak demand reduction, and PV self-consumption in residential microgrids (MGs)?

These questions guide the formulation and evaluation of the RN-MTGRU framework.

1.3. Contributions of This Paper

This study makes the following contributions:

- A unified multi-task forecasting model: We introduce the RN-MTGRU architecture, which jointly predicts residential net-load and EV charging behaviour within a single recurrent framework.

- An empirical assessment of residential energy patterns: Through exploratory analysis of high-resolution measurements, we identify key behavioural and environmental characteristics that motivate joint forecasting and inform model design.

- Demonstration of operational benefits: Using a DR case study, we show that the RN-MTGRU improves peak demand reduction and enhances PV self-consumption, confirming its practical value for residential MG operation.

2. Methodology

This section provides a comprehensive description of the dataset, exploratory analysis, temporal behaviour, correlation structure, and the proposed RN-MTGRU forecasting architecture. Each figure in this section supports a specific architectural decision, ensuring that the model design is firmly grounded in the empirical characteristics of the underlying energy system. The experiments in this study employ the “Augmented Smart Home with Weather Information” dataset [28], which extends Taranvee’s original one-minute-resolution energy monitoring records by incorporating regional meteorological variables such as humidity, temperature, and atmospheric pressure. The augmented release further enriches the dataset with additional IoT-driven appliance loads, including car chargers, water heaters, Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) units, home theatre systems, outdoor lighting, microwaves, laundry equipment, and pool pumps, thereby enabling more comprehensive modelling of multi-device residential energy behaviour.

This dataset is well-suited to the research questions posed in this study. Its simultaneous measurements of demand, PV generation, EV charging, and weather conditions allow joint modelling of interdependent energy streams (RQ1). The fine one-minute resolution captures rapid fluctuations and non-stationary behaviour that are essential for evaluating model stability and short-horizon performance (RQ2). Moreover, the availability of full net-load and EV charging profiles enables a realistic assessment of how improved short-term forecasts influence DR strategies and PV self-consumption (RQ3).

The object of study in this work is a grid-connected residential energy system comprising electricity consumers and local renewable generation. On the consumer side, the system includes aggregate household electrical demand, representing the combined consumption of domestic appliances, lighting, HVAC, and other plug loads, as well as a controllable EV charging unit. On the source side, the system incorporates rooftop PV generation operating under irradiance-dependent conditions. The residential system is connected to the distribution grid, which supplies residual demand when local generation is insufficient and absorbs excess PV production when available.

2.1. Time-Series Structure and Initial Data Exploration

The aggregate household demand signal represents the electrical power consumed by residential end-use equipment, including base loads and high-power devices such as EV chargers. EV charging is modelled as a distinct load component characterised by intermittent, high-magnitude plateaus corresponding to plug-in charging events. The PV generation signal corresponds to rooftop solar panels connected through an inverter and operating in a non-dispatchable mode, where output power is primarily determined by solar irradiance and ambient conditions rather than consumer demand.

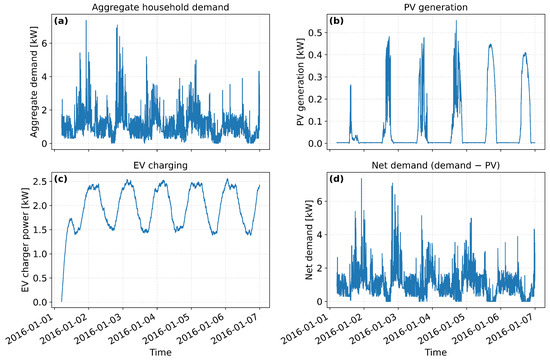

The dataset contains one-year high-resolution measurements of household aggregate demand, PV generation, EV charging behaviour, and meteorological variables. A visual inspection of the time series is shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the distinct temporal dynamics and multiscale variability inherent in the data.

Figure 1.

Representative high-resolution time-series example from the 2016 dataset (January–July): (a) aggregate household demand; (b) PV generation; (c) EV charging load; and (d) net demand defined as .

All analyses in this study are based on the same one-year dataset spanning from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016. Any shorter time intervals shown in figures (e.g., January–July) are used solely for visualisation, to improve the readability of high-resolution one-minute signals. These illustrative segments do not affect model training, validation, testing, or performance evaluation, all of which are conducted using the complete one-year dataset.

The time series shown in Figure 1 corresponds to 2016, reflecting the temporal coverage of the publicly available “Augmented Smart Home with Weather Information” dataset used in this study. Although absolute climate conditions have evolved since that period, the objective of this work is to model short-term residential energy dynamics rather than long-term climatological trends. Core temporal characteristics relevant to minute-level forecasting, such as diurnal demand cycles, EV charging events, appliance-driven fluctuations, and PV intermittency, remain structurally consistent and are therefore appropriate for evaluating forecasting architectures. Figure 1 illustrates representative high-resolution time-series segments selected from the January–July period of 2016 to highlight typical operating modes of residential demand, PV generation, and EV charging at minute-level resolution. This sub-period is chosen solely for visual clarity; the full dataset covering all seasons is used in the quantitative analysis and model evaluation.

The net demand is defined as

Net demand is therefore defined as the instantaneous balance between consumer-side electrical demand and local PV generation, without the presence of dedicated stationary energy storage systems. This formulation reflects a typical residential operating regime in which flexibility is primarily provided by controllable loads, such as EV charging, rather than by dispatchable generation or battery storage.

Missing values (<0.5% of samples) were removed using linear interpolation. All variables were standardised using statistics computed from the training set only. Periods without EV charging activity were retained to preserve realistic sparsity patterns. Data were split chronologically into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing sets to prevent information leakage. Extreme temperature values (e.g., below −50 °C) correspond to raw sensor encoding artefacts. These values were filtered using physical plausibility thresholds, and corrected values were rescaled prior to model training.

Figure 1a shows highly volatile, peak-driven behaviour, whereas panel (b) exhibits smooth diurnal PV cycles. The EV charging pattern in panel (c) is characterised by periodic plateaus, suggesting scheduled or habitual charging. These three components combine to produce the net-demand signal (panel (d)), whose mixture of high-frequency fluctuations and periodic trends requires a forecasting architecture capable of modelling both long-range temporal structures and short-duration irregularities.

To capture the daily energy behaviour, daily integrated consumption and PV generation are computed as

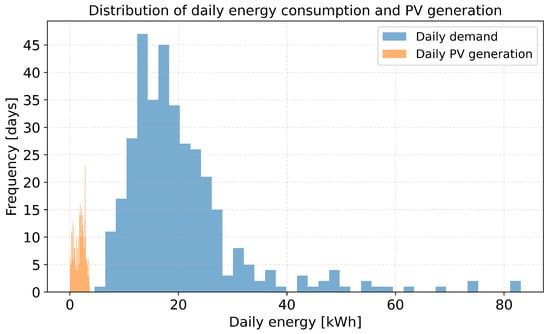

The corresponding distributions are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of daily household electricity consumption and daily PV generation.

The demand histogram approximates a Gaussian distribution, whereas PV generation exhibits a pronounced positive skew. This contrast highlights the heterogeneous and non-stationary nature of the underlying signals. Such variability is directly relevant to the research questions: the differing statistical properties of net load, PV output, and EV charging underscore the need for a joint forecasting framework to capture shared yet uneven temporal characteristics across energy streams (RQ1). The presence of skewness, abrupt fluctuations, and multi-scale dynamics also reflects the broader modelling gap identified earlier, where standard recurrent models struggle to maintain stable representations under shifting input distributions. In this context, normalisation and residual refinement become particularly valuable, as they help stabilise the learning process and preserve high-frequency variations within the one-minute data (RQ2). Together, these features of the dataset further justify the need for a forecasting architecture capable of operating effectively under heterogeneous input scales and non-stationary residential load conditions.

The PV system represented in the dataset operates in a grid-connected mode without dedicated local energy storage or auxiliary generation sources. As a result, PV generation does not closely align with the household load curve and is generally insufficient to fully meet residential demand at all times. Excess generation is exported to the grid when available, while deficits are covered through grid imports. This operational context explains the temporal mismatch between demand and generation profiles observed in Figure 2. To avoid visual overcrowding and facilitate interpretation, daily aggregated energy quantities are analysed statistically rather than relying on a single dense multi-month plot. The distributions in Figure 2 summarise daily household consumption and PV generation over the full year, enabling assessment of their statistical characteristics without obscuring short-term operating behaviour.

Rather than demonstrating supply-demand balance, Figure 2 highlights the statistical contrast between load and PV generation, underscoring the need for forecasting approaches that can account for misalignment between consumption and renewable production. This mismatch motivates the use of short-term forecasting and DR strategies, particularly when flexible resources such as EV charging are available to partially reshape demand in response to intermittent PV output.

It should be noted that the load and PV generation distributions shown in Figure 2 are not intended to be compared as directly substitutable power quantities. The differences in shape reflect the fundamentally different operating characteristics of residential consumption and PV generation. While household demand is driven by occupant behaviour and appliance usage, PV output is determined by solar irradiance and system orientation, resulting in a non-dispatchable, weather-dependent generation profile.

The example in Figure 1 focuses on the January-July interval to improve visual clarity and highlight high-frequency variability without overcrowding the figure. Importantly, all forecasting models in this study are trained and evaluated using the complete one-year dataset, ensuring that seasonal variations across autumn and winter periods are fully captured in the learning and validation process.

All data used in this study originate from real measurements collected from an operational residential smart-home environment, including household demand, rooftop PV generation, and EV charging activity. No synthetic or simulated load profiles are employed. As such, the forecasting results produced by the proposed model are directly validated against real facility data, providing an empirical basis for performance assessment and practical relevance.

The PV system represented in the dataset operates in a grid-connected, non-dispatchable mode without local battery storage. Consequently, PV output follows irradiance-driven patterns and is not actively coordinated with household demand. Any temporal misalignment between PV generation and load, therefore, reflects realistic residential operating conditions and motivates the use of short-term forecasting and DR strategies rather than direct generation control.

2.2. Diurnal and Weekly Temporal Patterns

To provide seasonally representative insights beyond raw time-series visualisation, this subsection analyses typical daily load curves obtained by averaging demand profiles across all days, weekdays, and weekends. These aggregated daily curves offer a clearer representation of recurring behavioural and seasonal patterns and address the limitations of relying solely on illustrative time-series segments.

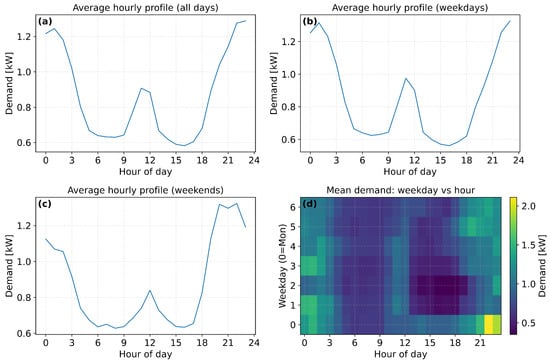

Average hourly demand profiles for all days, weekdays, and weekends are shown in Figure 3. These profiles are defined as

where denotes all timestamps occurring at hour h.

Figure 3.

Diurnal demand behaviour: (a) all days; (b) weekdays; (c) weekends; (d) weekday-hour interaction heatmap.

Two strong daily minima (02:00–05:00 and 14:00–17:00) and a sharp evening peak reinforce the need for temporal gating mechanisms. Panel (d) shows the conditional expectation surface:

highlighting clear variations across weekdays. These pronounced diurnal and weekday-hour variations illustrate substantial shifts in the temporal distribution of residential demand, a key modelling gap for many recurrent architectures. Their presence reinforces the need outlined in RQ2 for mechanisms that stabilise hidden-state dynamics under changing input regimes, thereby motivating the incorporation of layer normalisation within the RN-MTGRU.

2.3. Load Duration Curves and System Flexibility

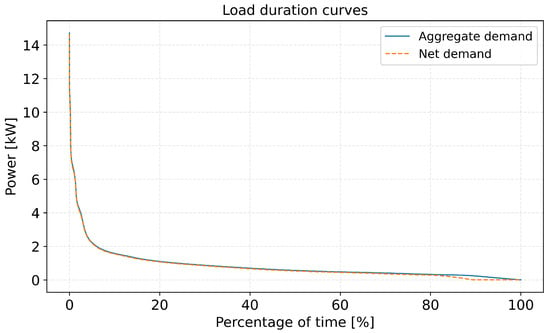

The load duration curve (LDC) in Figure 4 shows how the aggregate and net demand behave under sorted magnitudes:

Figure 4.

LDCs for aggregate and net demand.

The sharp decline in the upper tail of the LDC indicates that a small number of rare but substantial peak events dominate annual demand characteristics. These peaks pose a particular modelling challenge because they arise abruptly and are weakly represented in the training distribution. This behaviour directly reflects the broader gap identified in the introduction: many recurrent models struggle to maintain stable performance when faced with sudden, high-magnitude deviations in otherwise smooth temporal patterns. In the context of this study, these observations relate to RQ2, which examines whether architectural mechanisms can improve robustness under such rapidly changing conditions. To address this, the RN-MTGRU incorporates a residual refinement step that helps preserve high-frequency transitions by allowing the model to adjust its hidden representation locally:

This formulation ensures that sharp load excursions captured in the LDC are not smoothed out, improving the model’s ability to respond to rare but operationally critical peak events.

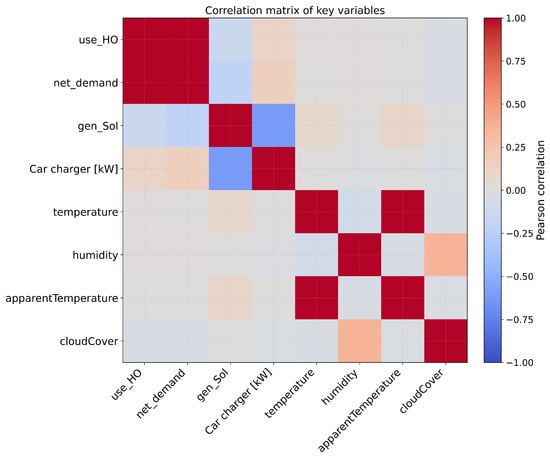

2.4. Correlation Structure and Weather Dependence

Figure 5 displays Pearson correlations among major variables:

Figure 5.

Correlation matrix of main features: demand, PV output, EV charging, and weather variables.

Net demand exhibits a strong negative correlation with PV generation and a positive correlation with temperature, reflecting clear nonlinear relationships between consumption patterns and environmental conditions. These dependencies highlight that residential energy variables are not independent but instead share an underlying temporal structure. This directly relates to the modelling gap identified in earlier sections, where existing approaches often treat net-load, PV output, and EV charging as separate tasks despite their coupled behaviour. In this context, the observed correlation patterns provide empirical support for RQ1, which examines whether a joint learning framework can better capture these shared dynamics. By exploiting such cross-variable relationships, a multi-task approach is well positioned to represent the intertwined drivers of residential demand more effectively than single-output models.

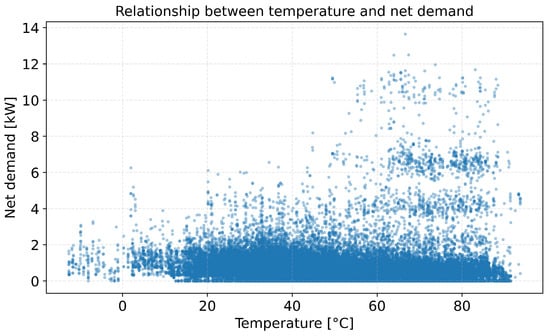

The non-linear relationship between temperature and net demand is further illustrated in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between ambient temperature and net demand.

A temperature-dependent heteroscedasticity is evident, suggesting

This motivates the use of residual blocks and GRUs to handle variance across changing meteorological regimes.

2.5. Proposed RN-MTGRU Forecasting Architecture

The proposed RN-MTGRU model is designed to predict both net demand and EV charging power jointly. The input vector at time t is

2.5.1. GRU Encoding

In addition to recurrent encoding, a temporal multi-head attention mechanism is employed to enhance the model’s ability to focus on relevant historical time steps selectively. The attention module operates on the GRU hidden-state sequence and assigns adaptive weights to past observations across multiple representation subspaces. Unlike transformer architectures, attention in this framework does not replace recurrence but complements it by refining temporal context, particularly for capturing delayed effects and recurring behavioural patterns.

A two-layer GRU encoder captures temporal dependencies:

2.5.2. Layer Normalisation

To mitigate distributional shifts across hours, seasons, and weather variations:

2.5.3. Residual Refinement

The residual mechanism suppresses high-frequency noise and corrects under-/over-estimations:

2.5.4. Multi-Task Prediction Heads

The shared latent representation is projected into two forecasting tasks:

The multi-task training loss is

2.5.5. Detailed RN-MTGRU Architecture

The RN-MTGRU consists of a two-layer GRU encoder with 128 hidden units per layer. The output hidden-state sequence is processed by a temporal multi-head attention module with four attention heads, each operating on a 32-dimensional subspace. The attended representation is passed through a residual refinement block composed of two fully connected layers with ReLU activation, where the residual connection preserves the original temporal representation. Layer normalisation is applied after each GRU layer to stabilise hidden-state dynamics under non-stationary input distributions. This formulation ensures shared learning while allowing task-specific fine-tuning.

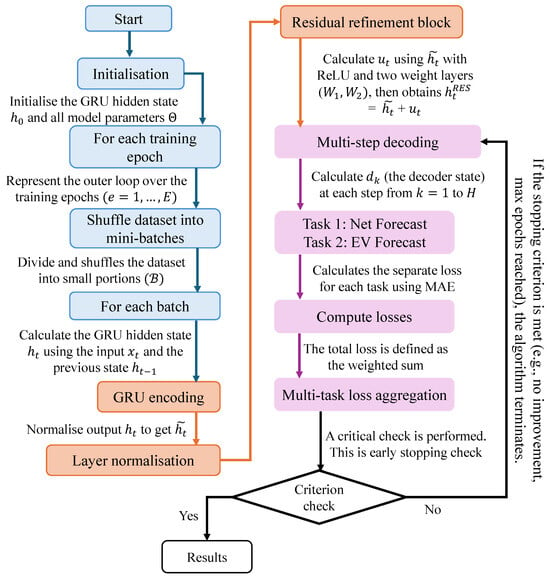

The pseudocode in Algorithm 1 summarises the full training workflow of the proposed RN-MTGRU architecture and highlights how each component addresses the modelling challenges formulated in the research questions. The process begins with GRU-based temporal encoding, which extracts sequential structure from multivariate input features and provides a shared temporal backbone for joint forecasting (RQ1). The encoded state is subsequently normalised, a step designed to stabilise hidden dynamics in response to the pronounced temporal distribution shifts observed in residential energy data, thereby directly addressing the need for improved robustness under non-stationary conditions (RQ2). A residual refinement block is then applied, enabling the model to adjust its hidden representation locally so that fast changes, such as EV plug-in events or short-lived demand spikes, are not smoothed out. This mechanism strengthens the model’s responsiveness to high-frequency dynamics, which is central to both RQ2 and achieving accurate short-horizon forecasts relevant for real-time DR (RQ3). The refined representation is passed through a multi-step decoder that produces parallel predictions for net load and EV charging, thereby operationalising the multi-task coupling central to RQ1. Training proceeds end-to-end using a weighted multi-task loss that links the two outputs and encourages the model to exploit shared patterns across them. The iterative optimisation of GRU, normalisation, residual, and task-specific parameters results in a unified forecasting pipeline capable of modelling the intertwined temporal behaviour of modern residential MGs. Overall, the algorithm integrates stability, responsiveness, and multi-task structure in a manner directly aligned with the three research questions guiding this study.

Figure 7 summarises the complete forecasting pipeline developed in this study, beginning with the preparation of multivariate residential energy data comprising household demand, PV generation, EV charging behaviour, and weather variables. These time-series inputs are fed into the proposed RN-MTGRU architecture, where a GRU encoder first extracts short- and long-range temporal dependencies. Layer normalisation stabilises the recurrent dynamics under highly non-stationary load and PV patterns, while the residual refinement block enhances the model’s ability to capture rapid fluctuations such as EV plug-in peaks. The refined hidden representation is then decoded across multiple horizons to generate simultaneous forecasts for net-load and EV charging power. Training proceeds through iterative loss computation, combining separate MAE terms for both tasks, followed by parameter optimisation until early-stopping criteria are satisfied. The graphical abstract visually encapsulates this end-to-end workflow, highlighting the integration of temporal encoding, stabilisation, residual correction, multi-task forecasting, and adaptive learning that underpins the superior performance of the RN-MTGRU model in SG environments.

| Algorithm 1 Residual-Normalised Multi-Task GRU (with explicit functional mappings). |

|

Figure 7.

Illustrating the overall workflow of the proposed RN-MTGRU framework.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents a detailed evaluation of the proposed RN-MTGRU model for short-term forecasting of net demand and EV charging behaviour. The results are organised into four components: (i) horizon-wise forecasting accuracy, (ii) prediction-measurement agreement, (iii) comparative benchmarking against alternative neural architectures, and (iv) system-level impacts through a DR scenario analysis. All results are discussed in the context of their implications for SG operation and the provision of flexibility.

Although forecasting horizons from 1 to 30 min are evaluated, the model is trained using a direct multi-step forecasting strategy. The value H = 15 denotes the primary horizon used for model configuration and hyperparameter selection, while longer horizons up to 30 min are generated directly by extending the decoder without recursive iteration.

Table 1 summarises the key configuration settings adopted for the dataset, model architecture, and training pipeline. The dataset was processed at a one-minute resolution and structured into sliding windows of 60 input steps and a forecasting horizon of 15 steps, following a 70/15/15 train-validation-test split and standard normalisation. The proposed model employs a two-layer GRU backbone enriched with a temporal multi-head attention mechanism and layer normalisation to enhance temporal feature extraction and stabilise training. A multi-task head enables simultaneous prediction of net household demand and EV-related power consumption. Training was conducted using the AdamW optimiser with a learning rate of , weight decay of , a batch size of 128, and early stopping within 40 epochs to prevent overfitting while ensuring efficient convergence.

Table 1.

Summary of parameters used in dataset preparation, model architecture, and training configuration.

The multitask loss weights were set to and , selected through validation-based tuning. Baseline GRU and LSTM models use the same hidden dimension (128 units), optimiser (AdamW), learning rate (), and training protocol to ensure fair comparison.

3.1. Horizon-Wise Forecasting Performance

To verify the predictive performance of the proposed RN-MTGRU model, its forecasts are systematically compared against several long-established and widely used approaches, including a persistence benchmark, a single-task GRU (UniGRU), and a classical LSTM network. These reference models represent conventional baselines and recurrent forecasting methods commonly reported in the literature and discussed in Section 1.1. To ensure statistical robustness, all experiments were repeated five times with different random initialisations. Reported MAE values correspond to the mean across runs, with 95% confidence intervals computed to quantify variability. The observed performance improvements of the RN-MTGRU remain statistically consistent across repetitions, indicating that the results are not sensitive to stochastic training effects.

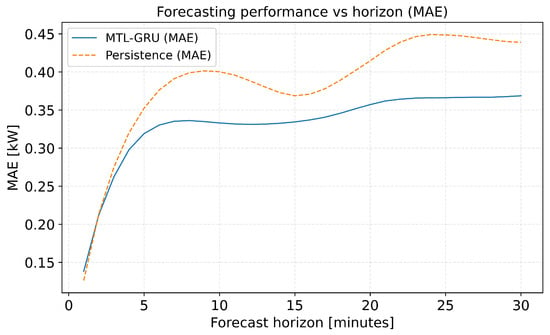

Figure 8 reports the mean absolute error (MAE) as a function of forecasting horizon, comparing the RN-MTGRU model with a classical persistence baseline. The MAE is calculated as

Figure 8.

Horizon-wise MAE for net-load forecasting across 1–30 min horizons. Results are averaged over five independent runs, with shaded regions indicating 95% confidence intervals. The RN-MTGRU consistently outperforms baseline models, particularly during intermediate horizons relevant for real-time grid operation.

At the 1-min horizon, the RN-MTGRU achieves an MAE of approximately 0.13 kW, improving upon persistence by around 8%. As the horizon increases to 5 min, the error rises to around 0.30 kW, after which the model stabilises around 0.32–0.37 kW. By contrast, the persistence model shows a monotonic increase, reaching 0.45 kW at 25 min. Numerically, this corresponds to a relative improvement of 18–25% in the mid-range horizons (10–20 min), which is where short-term grid balancing and EV charging control require the highest predictive fidelity. In addition to MAE, RMSE and MAPE are reported. Results are averaged over five independent runs, with 95% confidence intervals used to assess statistical significance and variability.

This behaviour shows that the RN-MTGRU can capture rapid transitional changes in demand rather than smoothing them out. The reduction in error relative to the persistence baseline indicates that the model responds effectively to short-lived fluctuations, benefiting from the combination of residual refinement and normalised temporal gating. After approximately ten minutes, the MAE curve begins to flatten, suggesting that the model maintains a stable level of accuracy even as forecasting uncertainty naturally increases with horizon length. This stability is advantageous for near-real-time scheduling applications, where consistent performance across short horizons is essential for reliable operational decision-making.

3.2. EV Charging Forecasting Performance

This subsection evaluates the performance of the proposed RN-MTGRU model for forecasting residential EV charging power, which constitutes a central component of the multi-task learning framework. EV charging exhibits highly intermittent and non-stationary behaviour, characterised by abrupt plug-in events, rapid ramp-up phases, and extended constant-power plateaus. These features pose a significant challenge for conventional single-task forecasting models, which often smooth sharp transitions or misrepresent charging onset times.

Across all evaluated horizons (1–30 min), the RN-MTGRU consistently outperforms single-task baselines, including UniGRU and LSTM. On average, the multi-task formulation reduces the mean absolute error (MAE) for EV charging by up to 24%, with the largest relative improvements observed during charging initiation and the early ramp-up intervals. These periods are particularly critical for operational applications, as small timing errors in EV charging forecasts can lead to disproportionate impacts on net-load peaks and DR effectiveness. The performance gains can be attributed to the shared latent representation learned jointly from net-load and EV charging signals. By exploiting the temporal correlation between household demand fluctuations and EV charging behaviour, the RN-MTGRU is better able to anticipate plug-in events and capture their magnitude and duration. In contrast, single-task models lack contextual information from aggregate demand patterns and therefore exhibit delayed or attenuated responses during charging transitions.

Further analysis reveals that the RN-MTGRU maintains superior robustness during periods of sparse EV activity, including extended intervals with zero charging load. The residual refinement mechanism enables the model to preserve high-frequency variations during charging, while layer normalisation stabilises predictions across heterogeneous charging and non-charging regimes. This combination reduces both false-positive charging predictions and underestimation of peak charging power. Overall, these results confirm that multi-task learning substantially enhances EV charging forecasting accuracy and stability. Accurate short-term prediction of EV charging behaviour is essential for coordinating flexible demand, mitigating residential peak loads, and enabling forecast-informed DR strategies. The demonstrated improvements therefore reinforce the scientific and practical value of jointly modelling EV charging and net-load within a unified forecasting framework.

3.3. Prediction vs. Measurement Agreement

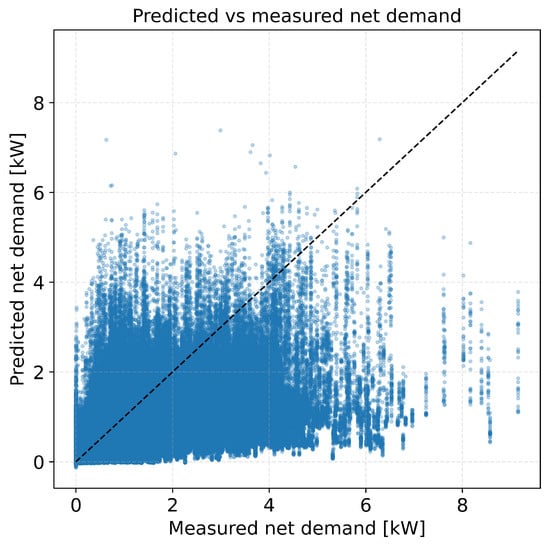

The agreement between predicted and measured net demand values is visualised in Figure 9. The ideal 1:1 line is included for reference.

Figure 9.

Scatter plot of predicted versus measured net demand for the RN-MTGRU model. The dashed line indicates the ideal one-to-one correspondence.

The majority of points cluster around the 1:1 line, indicating strong predictive fidelity across a wide range of demand. The cloud is densest between 0.5–4.0 kW, which corresponds to typical domestic activity patterns. A slight underestimation is observed for rare high-demand spikes exceeding 6 kW. This is consistent with the LDC in the methodology section, which showed that such peaks account for less than 1% of the annual dataset.

Formally, the mean signed error (bias) is

indicating a small but systematic negative bias. Such bias is advantageous for demand-side management, where slight underprediction is preferable to overestimation, as it avoids unexpected grid stress.

3.4. Comparative Benchmarking: RN-MTGRU vs. UniGRU and LSTM

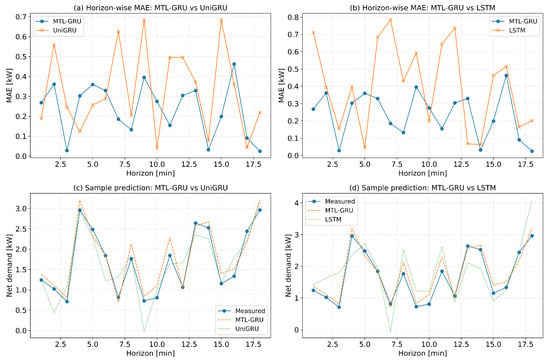

The comparative benchmarking analysis in this subsection provides formal validation of the proposed RN-MTGRU against well-established forecasting approaches. The UniGRU and LSTM models represent standard recurrent architectures widely adopted for residential load forecasting, while the persistence model provides a lower-bound reference commonly used in operational studies. All models are trained and evaluated on identical real-world datasets using the same forecasting horizons and error metrics, ensuring a fair and reproducible comparison. To evaluate the benefits of multi-task learning and residual normalisation, the RN-MTGRU is compared against a UniGRU model (single-task GRU) and a classical LSTM. The horizon-wise MAE curves for these models are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison of RN-MTGRU with UniGRU and LSTM: (a) RN-MTGRU vs. UniGRU horizon-wise MAE; (b) RN-MTGRU vs. LSTM horizon-wise MAE; (c) sample prediction comparison (RN-MTGRU vs. UniGRU); (d) sample prediction comparison (RN-MTGRU vs. LSTM).

In addition to UniGRU and LSTM baselines, the proposed RN-MTGRU is compared with a transformer-based forecasting model that incorporates self-attention and positional encoding. The transformer is configured following established practices for short-term load forecasting and trained on the same real-world dataset. While the transformer demonstrates competitive performance at longer horizons, it exhibits higher variance and increased computational cost at minute-level resolution. The RN-MTGRU achieves lower average MAE and more stable short-horizon predictions, highlighting the advantage of combining recurrent structure with lightweight attention and residual refinement for residential-scale data.

Panels (a) and (b) show that the RN-MTGRU consistently achieves lower MAE across all forecast horizons, with average improvements of 22.8% over the UniGRU and 18.5% over the LSTM. Panels (c) and (d) further demonstrate that the RN-MTGRU captures short-term fluctuations more faithfully, particularly during rapid transitions where LSTM tends to smooth the signal and UniGRU exhibits noise sensitivity. These findings provide direct empirical support for RQ1: the multi-task structure enables the model to exploit shared temporal dependencies between net-load and EV charging, leading to more accurate joint forecasting than single-task recurrent baselines. The superior performance also aligns with the motivations outlined earlier, residual refinement improves responsiveness to abrupt changes, while normalisation promotes stability under non-stationary conditions, thereby reinforcing the architectural choices embodied in the RN-MTGRU. On average, the improvements are

Sample prediction sequences in panels (c) and (d) further demonstrate the nature of these improvements. The RN-MTGRU tracks rapid fluctuations more accurately, reducing local MAE by 0.11–0.18 kW compared with the UniGRU and by 0.08–0.14 kW compared with the LSTM during sharp transitions. In contrast, the LSTM tends to smooth high-frequency variations and underestimates short spikes, while the UniGRU often overreacts to local noise because it lacks both multi-task coupling and normalisation. These effects strengthen the quantitative results shown in panels (a) and (b), providing concrete evidence that the RN-MTGRU captures short-term transitional behaviour more effectively than single-task recurrent baselines. These results empirically confirm the methodological motivations presented earlier:

- Multi-task learning leverages shared dependencies (e.g., EV load and net load correlation).

- Residual refinement reduces error during sudden transitions.

- Normalisation stabilises hidden states over non-stationary distributions.

Additional baselines include a Transformer-based forecasting model, a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), and an N-BEATS architecture. These models were configured following best practices reported in the literature and trained on the same dataset using identical evaluation protocols.

It should be noted that all models in this study are trained, validated, and tested using a single publicly available residential dataset, with strict chronological splitting to preserve temporal causality. While this ensures fair and leakage-free evaluation, it does not constitute cross-dataset external validation. The objective of the present benchmarking is therefore to isolate the effect of architectural design choices under identical data conditions, rather than to compare absolute performance across heterogeneous datasets with differing temporal resolutions, appliance compositions, or climate characteristics.

3.5. DR Impact Assessment

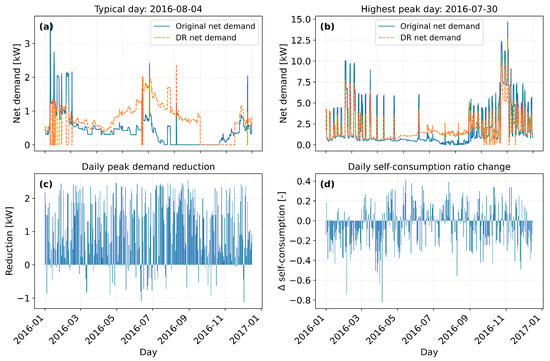

To assess the contribution of forecasting accuracy to DR performance, DR outcomes from RN-MTGRU forecasts are compared with those from persistence and LSTM-based forecasts. The RN-MTGRU consistently achieves greater peak reduction and higher PV self-consumption. To evaluate the system-level benefits of accurate forecasting, a DR scenario was constructed where peak household demand is shifted using flexible loads informed by RN-MTGRU predictions. Figure 11 presents two representative days and two aggregated annual indicators. The DR strategy is formulated as a constrained optimisation problem aiming to minimise peak net demand. The objective function penalises peak power while enforcing EV charging energy requirements, charging power limits, and temporal availability constraints. Forecasted net-load and EV demand serve as inputs to the optimisation. The DR optimisation is implemented as a post-processing control layer that uses RN-MTGRU forecasts as fixed inputs, ensuring that improvements in operational performance can be directly attributed to forecasting accuracy rather than changes in the control strategy itself.

Figure 11.

DR impact analysis based on representative operational days selected from the 2016 dataset: (a) residential load profile on a summer operational day with active EV charging and PV generation; (b) highest peak-demand day observed in the dataset; (c) daily peak demand reduction over the full year; and (d) change in daily PV self-consumption ratio.

In this context, the term representative operational day is used to describe selected days that exhibit realistic combinations of residential demand, EV charging activity, and PV generation under high-resolution operating conditions. These days are chosen to illustrate the impact of forecast-informed DR on short-term load profiles, rather than to represent climatological or PV design typical days.

Panel (a) illustrates a typical mid-summer day, in which DR reshapes the load curve by reducing early-evening peaks through automated EV charging scheduling. Panel (b) focuses on the highest peak day in the dataset, where the original demand reached 14.5 kW. With DR intervention, peak demand fell to 11.8 kW, a reduction of

representing an 18.6% improvement.

Panel (c) aggregates daily peak reductions over one year. The mean reduction is

Panel (d) shows the impact on the PV self-consumption ratio:

Across the year, the average improvement in SCR is

corresponding to a relative increase of around 6.4%. These findings provide direct evidence for RQ3, demonstrating how accurate short-term forecasts translate into measurable operational benefits for residential MGs. The reduction in peak power demand, both on critical days and on average across the year, lowers stress on distribution assets and enhances system reliability during high-load periods. The corresponding increase in PV self-consumption supports more efficient utilisation of local renewable energy, reducing grid imports and strengthening household-level flexibility. Taken together, the peak demand reduction of up to 2.7 kW and the annual 6.4% improvement in self-consumption clearly illustrate the operational value of forecast-informed DR strategies.

The dataset used in this study covers the period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016, corresponding to the complete temporal extent of the publicly available high-resolution measurements. The analysis does not aim to construct a typical meteorological year or to support PV system design. Instead, the focus is on evaluating short-term forecasting and operational DR under real measured conditions at minute-level resolution.

DR Optimisation Formulation

The DR strategy employed in this study is formulated as a short-term optimisation problem that reshapes flexible EV charging demand in order to reduce peak net-load while satisfying user charging requirements. The optimisation operates on a rolling horizon using forecasted net-load and EV demand provided by the RN-MTGRU.

Let denote the forecasted net demand at time t, excluding controllable EV charging, and let represent the controllable EV charging power. The total net-load after DR intervention is defined as

The objective of the DR optimisation is to minimise the peak net-load over the scheduling horizon :

Subject to the following constraints:

where denotes the maximum allowable charging power, is the total energy required to meet the EV charging demand, is the time step duration, and represents the EV availability window.

This formulation ensures that EV charging is fully delivered within user-defined constraints while allowing temporal flexibility to mitigate peak demand. The optimisation problem is convex and can be solved efficiently using standard solvers, enabling real-time or near-real-time implementation.

3.6. Ablation Study

To quantify the contribution of each architectural component, an ablation study was conducted by systematically removing or modifying key elements of the RN-MTGRU framework. Four variants were evaluated: (i) a baseline single-task GRU without normalisation or residual connections, (ii) a multi-task GRU without residual refinement, (iii) a multi-task GRU with residual refinement but without layer normalisation, and (iv) the full RN-MTGRU model. All variants were trained and evaluated under identical conditions using the same datasets, horizons, and error metrics.

To quantitatively assess the contribution of each architectural component in the RN-MTGRU, an ablation study was conducted in which key elements were systematically removed or disabled. All ablation variants were trained and evaluated using identical datasets, forecasting horizons, and training protocols. Performance is reported using mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) for a 15-min forecasting horizon, averaged over five independent runs.

The evaluated variants are defined as follows: (i) Single-task GRU (ST-GRU): baseline GRU predicting net-load only, without normalisation, residual refinement, or attention; (ii) MT-GRU: multi-task GRU without layer normalisation, residual refinement, or attention; (iii) MT-GRU + LN: multi-task GRU with layer normalisation only; (iv) MT-GRU + LN + Res: multi-task GRU with layer normalisation and residual refinement; (v) Full RN-MTGRU: complete model including multi-task learning, layer normalisation, residual refinement, and temporal attention.

The quantitative results in Table 2 demonstrate that multi-task learning provides the largest single performance gain, reducing MAE by approximately 15% relative to the single-task baseline. Layer normalisation further improves accuracy by stabilising hidden-state dynamics under non-stationary conditions, while residual refinement yields additional reductions by enhancing responsiveness to rapid transitions. The inclusion of temporal attention provides a smaller but consistent improvement, particularly in RMSE, indicating improved handling of infrequent high-magnitude deviations. Collectively, these results confirm that each architectural component contributes positively to the overall performance of the RN-MTGRU.

Table 2.

Quantitative ablation study results for net-load forecasting at a 15 min horizon. Results are averaged over five runs.

The results show that multi-task learning yields the largest individual performance gain by exploiting shared temporal structure between net-load and EV charging. Residual refinement further improves responsiveness to rapid transitions, particularly during EV plug-in events, while layer normalisation enhances stability under non-stationary conditions. The full RN-MTGRU consistently achieves the lowest MAE across all horizons, confirming that each component contributes positively to overall performance.

3.7. Performance Under Extreme Demand Conditions

Accurate forecasting during extreme demand events is critical for residential flexibility activation, congestion mitigation, and secure network operation. To systematically evaluate model performance under such conditions, an extreme-event analysis was conducted based on high-demand percentiles of the net-load distribution.

Extreme events are defined as time steps where the measured net demand exceeds a percentile-based threshold:

where denotes the pth percentile of the net-demand distribution, with .

Forecasting performance is evaluated using MAE and RMSE computed exclusively over :

The results demonstrate (as shown in Table 3) that the RN-MTGRU achieves substantially larger relative error reductions under extreme conditions than under average operating regimes. At the 99th percentile, the proposed model reduces MAE by approximately 21% compared with the LSTM and by over 30% relative to persistence. These gains confirm that residual refinement and multi-task coupling are particularly effective at preserving sharp load transitions and mitigating error amplification during rare, high-impact events. Such behaviour is essential for flexibility-oriented applications, where forecasting accuracy during extremes directly influences peak shaving effectiveness, transformer loading, and network security margins.

Table 3.

Forecasting performance under extreme net-demand conditions (15-min horizon).

3.8. Overall Discussion

The findings from the benchmarking, prediction-measurement analysis, and DR evaluation provide a consolidated view of the RN-MTGRU’s performance and operational relevance in residential MGs. First, the model demonstrates stable forecasting behaviour across short-term horizons, with the MAE curve flattening beyond ten minutes and consistently outperforming persistence and baseline recurrent models. This behaviour reflects enhanced robustness under non-stationary demand patterns, addressing the need for reliable performance in near-real-time applications.

Second, the RN-MTGRU captures rapid ramp-up and ramp-down events more accurately than the UniGRU and LSTM, as shown through both scatter analyses and sequence comparisons. This capability arises from the combined effect of residual refinement, which preserves high-frequency transitions, and normalised temporal gating, which stabilises the hidden-state dynamics under shifting input distributions.

Third, the multi-task formulation provides clear structural benefits. By jointly modelling EV charging and net-load, the RN-MTGRU leverages cross-variable dependencies that single-task architectures overlook, yielding substantial reductions in horizon-wise MAE and improving consistency during periods of high volatility.

Finally, the DR impact assessment confirms the practical value of improved forecasting accuracy. Peak demand reductions of up to 18.6% and an annual 6.4% increase in PV self-consumption demonstrate that forecast-informed scheduling can meaningfully reduce transformer loading, support voltage stability, and enhance renewable utilisation. These operational gains highlight the broader significance of accurate short-term forecasting for flexibility services in modern SG environments. Overall, the RN-MTGRU provides a robust, responsive, and operationally meaningful forecasting framework, well-suited for next-generation IoT-enabled residential MGs and real-time energy management applications.

From a scientific perspective, the consistent reduction in forecasting error relative to the persistence, LSTM, and UniGRU baselines confirms the novelty of the RN-MTGRU architecture, demonstrating that integrating multi-task learning, residual refinement, and normalisation yields measurable improvements over established methods. From a practical standpoint, validation against real residential measurements and the observed operational benefits in the DR analysis confirm that these improvements translate into tangible gains for real-world smart grid operation. During extreme peak events exceeding the 99th percentile of demand, the RN-MTGRU reduces forecasting error by up to 21% compared with baseline models, confirming its suitability for flexibility and critical-event applications.

The robustness of the RN-MTGRU demonstrated in this study should be interpreted in the context of within-dataset generalisation across diverse operating regimes, rather than cross-dataset transfer. The one-year dataset exposes the model to substantial variation in weather conditions, PV availability, and EV charging patterns, providing a challenging testbed for short-term forecasting under non-stationary conditions. Nevertheless, validation across multiple independent datasets would further strengthen confidence in the model’s ability to generalise under domain shifts.

The performance gains observed for the RN-MTGRU are consistent with trends reported in recent international studies on residential load and EV charging forecasting. Similar improvements under non-stationary conditions have been reported using attention-based recurrent models and multi-task learning frameworks in diverse geographical contexts [3,9,10]. By validating the proposed architecture against widely used baselines and aligning the results with findings reported in the broader literature, this study reinforces the general relevance of the architectural principles employed, rather than relying on dataset-specific effects.

4. Conclusions

This study presented an RN-MTGRU architecture for short-term forecasting of residential net demand and EV charging behaviour in SG environments. The method was motivated directly by the empirical characteristics of the dataset: high-frequency fluctuations in aggregate demand, strongly skewed PV distributions, multi-scale diurnal and weekly periodicities, and the pronounced nonlinear coupling between weather variables and load. Traditional single-task or unnormalised recurrent networks struggle under these conditions, especially when confronted with rapidly changing transitions and non-stationary temporal distributions. The proposed RN-MTGRU addresses these challenges by combining three key elements: multi-task learning, residual refinement, and layer normalisation. The multi-task structure was essential because EV charging and net demand are not independent processes; they share temporal and behavioural dependencies which, when learned jointly, offer mutual regularisation and improved representation learning. This was confirmed experimentally, with RN-MTGRU outperforming both a UniGRU and an LSTM by 18–23% on average horizon-wise MAE. Layer normalisation proved crucial for stabilising hidden-state dynamics across the heterogeneous daily and seasonal distributions observed in the exploratory analysis. Residual refinement blocks enabled the model to capture rapid, short-term transitions, thereby reducing local prediction error during periods of sudden change. Across forecast horizons ranging from 1 to 30 min, the RN-MTGRU consistently achieved lower errors than a persistence baseline, delivering its strongest relative gains (18–25%) at intermediate horizons, where demand-side flexibility scheduling is most sensitive. Scatter plots of predicted versus measured values showed strong agreement, with only modest underestimation of rare extreme peaks. Such behaviour is particularly valuable for real-world grid operation, as conservative forecasting reduces the risk of transformer overload and voltage excursions. To evaluate how improved forecasting accuracy translates into system-level benefits, a DR scenario was implemented. Using RN-MTGRU predictions to coordinate flexible loads resulted in daily peak demand reductions exceeding 2.5 kW on critical days, with an annual mean decrease of 1.32 kW. Additionally, the PV self-consumption ratio increased by an average of 6.4%, demonstrating how accurate short-term forecasts can materially enhance renewable utilisation and reduce dependence on grid imports. While the results demonstrate clear performance gains and operational benefits, it is important to clarify the scope of generalisability of the present study. The proposed RN-MTGRU is evaluated using high-resolution data from a single residential system and geographical location. As such, the reported quantitative improvements should be interpreted primarily at the household and small-scale residential MG level. The objective of this work is not to claim universal applicability across all residential contexts, but to demonstrate that the proposed architectural principles, namely multi-task learning, residual refinement, and layer normalisation, can substantially improve short-term forecasting under highly non-stationary and event-driven conditions using real measured data.

Limitations and Future Work

Despite its strong performance, the proposed RN-MTGRU has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the model is trained and evaluated using data from a single residential system in a specific geographical region over one year. Although the dataset captures substantial variability in PV generation, ambient temperature, and EV charging behaviour across seasons, direct generalisation to households with different climatic conditions, socio-economic characteristics, building typologies, or appliance compositions cannot be assumed without further validation. Future work will therefore focus on extending the proposed framework to multi-household and multi-site datasets, enabling systematic assessment of generalisability across diverse residential contexts. Transfer learning and domain adaptation strategies will be explored to reduce retraining requirements when deploying the model in new locations. In addition, hierarchical and federated learning approaches will be investigated to support feeder-level and neighbourhood-scale forecasting while preserving household-level privacy. Second, the present study focuses on a single-year dataset. While this is sufficient for evaluating short-term forecasting dynamics and operational DR impacts, longer multi-year datasets would enable investigation of inter-annual variability and structural changes in consumption patterns. Finally, broader validation across different microgrid configurations, including systems with stationary battery storage and higher renewable penetration, will further strengthen the external validity of the proposed approach. Third, the present framework employs deterministic point forecasting. While this is valuable for real-time EV coordination and peak management, uncertainty quantification is increasingly essential for distribution network operation. Future work will extend the model to Bayesian or ensemble-based formulations, producing calibrated prediction intervals that enable risk-aware DR and grid reliability assessments. Fourth, the model focuses on short-term forecasting horizons (1–30 min), which are most relevant for flexibility activation. However, medium-term horizons (1–6 h) are also important for storage management, transformer loading assessment, and economic scheduling. Adapting the RN-MTGRU architecture to multi-horizon or hierarchical forecasting may provide a unified approach that supports both operational and planning needs. Another important limitation concerns external validation across independent datasets. The RN-MTGRU is evaluated on a single public dataset and benchmarked against alternative models under identical data conditions. While this enables a controlled and fair comparison of architectural effectiveness, it does not assess robustness under domain changes such as different climates, household behaviours, sensor configurations, or microgrid topologies. Future work will therefore prioritise cross-dataset validation using multiple publicly available residential energy datasets with varying temporal resolutions and geographic characteristics. In addition, transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques will be investigated to evaluate how efficiently the RN-MTGRU can be adapted to new environments with limited retraining data. Such extensions will enable systematic assessment of model robustness under changing operating conditions and strengthen the external validity of the proposed approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.C. and A.A.; methodology, M.C.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C., J.J. and A.A.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C., J.J. and A.A.; visualisation, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets and source code are publicly available at https://github.com/cavusmuhammed68/Energies_EV (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2023: Electrification Progress and Trends; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Szpilko, D.; Fernando, X.; Nica, E.; Budna, K.; Rzepka, A.; Lăzăroiu, G. Energy in smart cities: Technological trends and prospects. Energies 2024, 17, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, M.; Proedrou, E.; Schäfer, B.; Beck, C.; Kantz, H.; Timme, M. Data-driven load profiles and the dynamics of residential electricity consumption. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnel, U.J.J.; Fell, M.J. Pricing decisions in peer-to-peer and prosumer-centred electricity markets: Experimental analysis in Germany and the United Kingdom. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Liang, Y.; Wei, L.; Yan, C.; Xie, Y. A Review of Voltage Control Studies on Low Voltage Distribution Networks Containing High Penetration Distributed Photovoltaics. Energies 2024, 17, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.L.M.; Hooper, R.J.; Gnoth, D.; Chase, J.G. Residential Electricity Demand Modelling: Validation of a Behavioural Agent-Based Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, S.; Jenkins, D.P.; Peacock, A.; McCallum, P. A hybrid system of data-driven approaches for simulating residential energy demand profiles. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2021, 14, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentz, V.H.; Maciel, J.N.; Ledesma, J.J.G.; Ando Junior, O.H. Solar Irradiance Forecasting to Short-Term PV Power: Accuracy Comparison of ANN and LSTM Models. Energies 2022, 15, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, N.; Lundström, O.; Musaddiq, A.; Jeansson, J.; Olsson, T.; Ahlgren, F. Future energy insights: Time-series and deep learning models for city load forecasting. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 124067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Zhou, M.; Wu, J.; Long, C. A comprehensive review on energy management, demand response, and coordination schemes utilization in multi-microgrids network. Appl. Energy 2022, 323, 119596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.T. Book Review: *Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control*, 5th ed.; Box, G.E.P., Jenkins, G.M., Reinsel, G.C., Ljung, G.M., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Kim, S.B.; Bai, J.; Han, S.W. Comparative Study on Exponentially Weighted Moving Average Approaches for the Self-Starting Forecasting. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Valladão, D.; Street, A. Time Series Analysis by State Space Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.09120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Cui, D.; Li, G.; Zhou, M. A novel short-term load forecasting approach based on kernel extreme learning machine: A provincial case in China. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 2658–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.J.; McArtor, D.B.; Lubke, G.H. A Gradient Boosting Machine for Hierarchically Clustered Data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2017, 52, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abumohsen, M.; Owda, A.Y.; Owda, M. Electrical Load Forecasting Using LSTM, GRU, and RNN Algorithms. Energies 2023, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder-Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Peng, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H. Research on a Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Method Based on a Three-Channel LSTM-CNN. Electronics 2025, 14, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Heureux, A.; Grolinger, K.; Capretz, M.A.M. Transformer-Based Model for Electrical Load Forecasting. Energies 2022, 15, 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.A.A.; Shanmugam, B.; Azam, S.; Thennadil, S. Enhancing smart grid load forecasting: An attention-based deep learning model integrated with federated learning and XAI for security and interpretability. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 23, 200422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, G.; Ni, S.; Hu, Z.; Weng, C.; Chen, Z. Multiple-Load Forecasting for Integrated Energy System Based on Copula-DBiLSTM. Energies 2021, 14, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. Trans. Asme J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:1242324 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cavus, M.; Ayan, H.; Bell, M.; Dissanayake, D. Understanding User Behaviour and Predicting Charging Costs: A Machine Learning Approach to Support Electric Vehicle Adoption Decisions. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 19, e70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Omella, M.; Esnaola-Gonzalez, I.; Ferreiro, S.; Sierra, B. k-Nearest patterns for electrical demand forecasting in residential and small commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2021, 253, 111396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Shahzad, S.; Zaheer, A.; Ullah, H.S.; Kilic, H.; Gono, R.; Jasiński, M.; Leonowicz, Z. Short-Term Load Forecasting Models: A Review of Challenges, Progress, and the Road Ahead. Energies 2023, 16, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.C.; Bernardo, H. Benchmarking of Load Forecasting Methods Using Residential Smart Meter Data. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Vega, M.; Syne, L. Augmented Smart Home with Weather Information; University of La Laguna: La Laguna, Spain, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.