1. Introduction

In recent years, the market share of electric light commercial vehicles has been steadily increasing, driven by both growing environmental awareness and tightening European CO

2 emission standards. EU climate goals, which assume a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and achieving neutrality in the transport sector by 2035, place electromobility at the heart of the transformation of urban logistics. As a result, annual registrations of electric commercial vehicles are showing double-digit growth, underscoring the growing importance of these vehicles as a key element of green mobility. Including operational parameters such as energy consumption, charging time, and payload capacity in research provides practical and reliable support for fleets’ operational decisions, which is crucial for an efficient and sustainable transformation of the transport sector [

1].

Four selected evaluation parameters—range, energy consumption, payload, and charging times—were identified as key indicators of the operational efficiency of urban fleets. Range determines the ability to complete daily routes without frequent charging, energy consumption influences operating costs and energy efficiency, payload determines the ability to transport goods, and charging time determines the vehicles’ availability in distribution operations. Analysis of these parameters allows for a comprehensive assessment of the suitability of electric vehicles in the operational practice of logistics fleets.

The aim of this article is to compare electric delivery vehicles, taking into account additional operational parameters such as energy consumption, charging time and payload, in order to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of their suitability for logistics applications and to support the decision-making process regarding the selection of vehicles for transport fleets. The first stage introduces the issues of electromobility in the delivery industry and reviews current research in this field. Next, data is collected and the research method, including the selection of analyzed parameters, is defined. A comparative analysis of electric delivery vehicles is presented, along with their interpretation. The paper concludes with a summary of the most important observations and an indication of possible implications for further research [

2].

A light commercial vehicle (LCV) is a commercial vehicle with a gross vehicle weight (GVW) of less than 3.5 tonnes, used for carrying goods. These vehicles, including vans and light trucks, are designed for passenger transport and light to medium-duty cargo and are often used in urban and suburban areas due to their efficiency and maneuverability. Official weight categories for commercial vehicles [

3]:

N1—Light Commercial Vehicles (LCV): gross vehicle weight up to 3.5 tonnes. They can be driven with a category B driving license. In addition to the driver, they can carry goods or up to 8 passengers,

N2—Medium Commercial Vehicles (UV): weighing between 3.5 tonnes and 7.5 tonnes. They require a category C1 driving license and are primarily intended for freight transport,

N3—Heavy Goods Vehicles: weighing over 7.5 tonnes, requiring a category C driving license.

It is worth noting that commercial vehicles (VU) can be distinguished from passenger vehicles (VP) by, among other things, the code in box J1 of the vehicle registration certificate (designations such as: VU, CTTE, DERIV-VP, or VTSU). Additionally, by definition, the cargo area must be at least half the length of the wheelbase and cannot be equipped with mounting elements for seats or seat belts [

3].

2. Number of Electric Light Commercial Vehicles

Although electric delivery vehicles still constitute a small percentage of the total commercial vehicle fleet in Poland, their number is steadily growing. This growth is supported by government programs such as “Mój Elektryk”, which offer subsidies for the purchase of new electric delivery vehicles. Furthermore, the development of charging infrastructure and growing environmental awareness among businesses are contributing to increased interest in this type of vehicle [

4].

Existing studies often focus on single aspects of electric delivery vehicles, such as range or charging efficiency, without integrating them into a comprehensive analysis that also considers payload capacity. Furthermore, most available data comes from developed markets, while emerging markets such as Poland have different logistical and infrastructure conditions, limiting the applicability of these results. This study fills this gap by offering a more comprehensive comparison of performance parameters in the context of real-world applications [

5,

6].

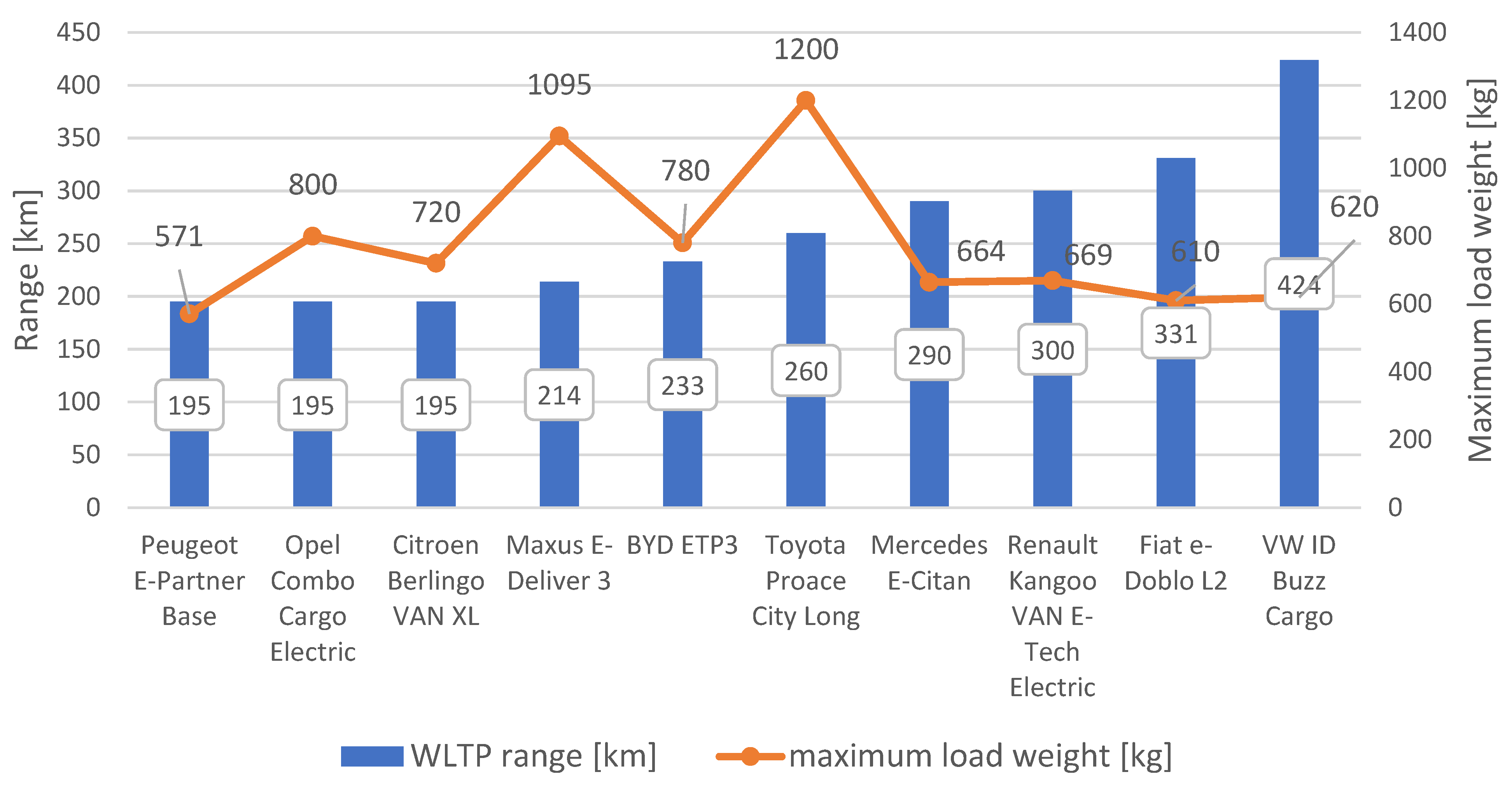

Diesel remains the dominant powertrain among newly registered delivery vehicles in Poland in 2022–2025. In 2022, 57,047 diesel vehicles were registered, a number that gradually increased to 60,824 in 2024. In 2025 (through September), the number of new diesel vehicle registrations reached 45,404, suggesting a continued high share of this type of powertrain throughout the year, although a slight decline compared to previous years is possible if the registration rate does not increase in the final quarter [

5,

6]. For gasoline-powered vehicles, registrations remain significantly lower, ranging between 3462 and 3886 vehicles between 2022 and 2024, with a slight decline to 1793 in 2025 (through September). This trend indicates a gradual decline in interest in gasoline vehicles in this market segment [

5,

6].

In turn, the number of electric vehicle registrations, while still relatively low, shows some fluctuations. In 2022, 1414 electric delivery vans were registered, in 2023 this number increased to 2450, before falling to 1867 in 2024. In 2025 (through September), 1310 new registrations were recorded. These data suggest that the development of electromobility in the delivery vehicle segment is progressing slowly and unevenly, although interest in this type of drivetrain remains strong. Despite the increasing promotion of alternative powertrains, the new commercial vehicle market in the analyzed period remains dominated by diesel vehicles. The share of electric and petrol vehicles remains marginal, and the observed changes do not yet indicate a clear trend toward zero-emission powertrains [

5,

6]. The registration structure of new commercial vehicles according to the drive system used is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Advantages of Using Electric Delivery Vehicles

Recent years have seen a rapid increase in interest in the electrification of road transport, driven both by technological advances in energy storage and increasing regulatory pressure to reduce pollutant emissions. Electric light commercial vehicles (LCVs) are a particularly important segment in this context, as they are heavily used in urban distribution, where their operation can significantly contribute to reducing local emissions [

5,

6].

The primary advantage of electric LCVs is the absence of exhaust emissions at the point of use, which helps reduce the concentration of nitrogen oxides (NO

x), particulate matter (PM), and carbon dioxide (CO

2) in the urban environment. This is particularly important in the context of achieving the European Union’s climate policy goals and implementing clean transport zones in cities. Unlike combustion vehicles, electric vehicles also feature lower noise levels, which positively impacts acoustic comfort in urban spaces, especially during nighttime deliveries [

5,

6].

Another advantage is lower operating costs resulting from the simpler drivetrain design and lower electricity costs compared to fossil fuels. Electric vehicles do not require regular replacement, such as engine oils, fuel filters, or exhaust systems, which reduces the frequency of technical inspections and lowers the total cost of fleet maintenance. Combined with the increasing availability of charging infrastructure and the possibility of using energy tariffs adapted to overnight charging, operating this type of vehicle is becoming increasingly economical [

7].

The operational aspect is also important. Electric delivery vehicles offer high torque engine available from the lowest speeds, facilitating maneuvering in urban environments and increasing dynamic starting. The range of modern models fully covers the needs of most last-mile distribution operations, and the ability to charge using fast chargers allows for flexible route planning and reduced downtime.

It is worth noting that electric vehicles are equipped with a system for energy recuperation during braking. The amount of energy recovered depends on the braking method, the efficiency of the energy conversion system, and kinetic energy, which increases with increasing vehicle weight (carrying loads). Energy recuperation from a braking vehicle reduces the load on the braking system, which has a positive impact on particulate matter emissions into the environment [

8].

From a social and image perspective, the use of electric vehicles in light transport is also a component of a company’s sustainable development strategy. The introduction of low-emission transport solutions allows companies to build a reputation as innovative and environmentally responsible entities, which can have a positive impact on relationships with business partners and consumers. In summary, light-duty electric vehicles combine ecological, economic, and operational benefits, making them an attractive alternative to conventional combustion vehicles, especially for urban applications. Their further development and widespread adoption represent a significant step towards decarbonizing road transport and improving the quality of life in urban areas [

7].

4. Costs and Legal Aspects Electric Delivery Vehicles

The operating costs of electric delivery vehicles are increasingly favorable compared to their conventional combustion engine counterparts, especially in the long term. While the purchase price of an electric vehicle can be higher, operating one can be significantly cheaper, which in the long run can offset or even exceed the initial outlay. One of the main advantages of electric vehicles is the lower cost of refueling. Electricity—especially if it comes from a night-time tariff or from a private photovoltaic system—is significantly cheaper than fuel. It should be emphasized, however, that the actual economic benefits depend largely on the annual mileage of the vehicle, because with low mileage the payback period for the higher costs of purchasing an electric vehicle can be significantly extended. Furthermore, electric vehicles have fewer mechanical parts that can fail—for example, they lack a gearbox, clutch, starter motor, or exhaust system. As a result, service and ongoing maintenance costs are typically lower than for diesel vehicles. Fees associated with daily use can also be more favorable. Many cities offer preferential parking conditions for zero-emission vehicles, and entry to clean transport zones (whose range will only increase) is usually free or significantly cheaper for electric vehicles [

9,

10].

Funding programs are available to provide additional support. The most well-known of these in Poland is the “Mój Elektryk” (My Electrician) program, which offers subsidies of up to PLN 70,000 for the purchase of a new N1 electric van (for businesses). In some cases, combining the subsidy with dealer promotions (e.g., year-end sales), the total financial support can reach up to PLN 140,000, significantly lowering the barrier to entry [

4].

All this means that, despite their higher starting price, electric vans can prove more economical in terms of total cost of ownership (TCO). This is especially true for intensive urban use, where the benefits of quiet, emission-free driving and low operating costs become particularly noticeable. Requirements for Electric Vehicles in Fleets—Status as of 2025. Analyzing TCO of electric delivery vehicles allows for the correlation of range, energy consumption, and payload performance with real-world fleet operating scenarios. Vehicles with longer ranges may require larger and more expensive batteries, which increases acquisition costs but also reduces charging frequency and downtime, improving operational efficiency. Conversely, vehicles with higher payloads can transport larger volumes of goods on a single route, which can reduce the number of trips and operating costs, but their energy consumption is often higher. Considering TCO in the context of these parameters allows fleet operators to assess the optimal trade-off between acquisition costs, operating costs, and operational efficiency, which is crucial when deciding on vehicles for urban logistics [

11].

Poland has a 2018 Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels, which has been amended several times and sets specific limits on the share of electric vehicles in the fleets of various entities. According to this Act, public sector entities, such as municipalities, offices, and municipal companies, must ensure that at least 30% of their fleets are electric by the end of 2025. For some public entities, especially local governments with populations exceeding 50,000, these regulations are even more stringent [

12,

13].

Companies providing public services, such as waste collection, public transport, or government deliveries, are also required to meet specific thresholds for the share of electric vehicles, which, depending on the type of business, range from 10 to 30%. For private companies, however, mandatory thresholds for the share of electric vehicles have not yet been introduced, although work is underway on changes to the regulations, which may in the future apply, particularly to large corporate fleets.

At the same time, European Union regulations indirectly impact fleet policy, as from 2035, a ban on the sale of new combustion engine vehicles will apply across the EU, meaning all new vehicles will have to be zero-emission. Additionally, green public procurement rules are being introduced, requiring tenders to include a certain number of electric or low-emission vehicles [

1,

14,

15]

Despite the dynamic development of electromobility, electric delivery vehicles still face a number of limitations that impact their widespread adoption. The most frequently cited drawbacks include degradation of traction batteries during operation and the high cost of replacing them. Another significant factor is the still insufficiently developed charging infrastructure, particularly outside large urban areas, as well as the longer refueling time compared to vehicles powered by conventional fuels. Combined with the higher purchase price of electric vehicles, these factors mean that the number of newly registered electric delivery vehicles is currently significantly lower than that of conventionally powered vehicles [

1,

14].

5. Research Object

The study focused on electric delivery vehicles from the small and medium-sized segments. Their technical parameters, operational characteristics, and applicability in urban environments were analyzed. Particular attention was paid to energy efficiency and range in real-world driving conditions. The collected data are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

The most important parameters determining the efficiency of LCV use include range, charging time, and payload. Range determines the ability to complete transport tasks without the need for charging breaks, while charging time directly impacts the vehicle’s availability and fleet productivity. A vehicle’s payload determines its ability to transport goods, which is crucial for economic efficiency in delivery transport. In turn, battery capacity is designed to extend the range of an electric vehicle. However, it should be noted that increasing battery capacity is associated with an increase in its weight, which leads to an increase in the overall vehicle weight. Consequently, a higher vehicle weight results in higher energy consumption, which partially offsets the benefits of a larger battery capacity. In practice, this means there is a design compromise between battery capacity, vehicle payload, energy efficiency, and actual operating range [

2].

Vehicles are divided into two groups based on their belonging to different segments of the light commercial vehicle (LCV) market and are based on differences in body size, gross vehicle weight, cargo volume, and typical operational purpose. However, it is not possible to clearly define this division solely based on metric values, as individual vehicles differ in their set of technical and design parameters, and a larger cargo volume does not always translate into a higher permissible payload, and vice versa. Group 1 includes vehicles in the compact segment (B/C—Small/Compact Vans), intended primarily for urban logistics and local distribution, while Group 2 includes vehicles in the medium segment (D—Medium Vans), offering greater payload and cargo space, used in distribution and logistics processes requiring the transport of larger cargo volumes and regional transport.

The analyzed delivery vehicles were divided into two groups: small and medium, based on key operational and design parameters, such as cargo space, permissible payload, and cargo space dimensions. The small vehicle group includes models characterized by a shorter cargo space length (less than 2800 mm) and a lower permissible payload. Medium delivery vehicles are distinguished by a longer cargo space (often exceeding 3000 mm) and a higher permissible payload. It is worth noting that the Maxus brand offers two models—the E-Deliver 3 and E-Deliver 7—which fall into the small and medium-sized delivery vehicle categories, respectively. The two models differ in both cargo space and permissible payload.

6. Research and Discussion

The study analyzed the relationships between key operating parameters of electric commercial vehicles. Specifically, energy consumption per 100 km was examined in relation to vehicle weight, vehicle range in relation to energy consumption, and vehicle payload. The values presented are based on manufacturer-declared data obtained under the WLTP cycle and therefore represent standard, comparable test conditions. This is intended to increase data transparency and clearly establish a basis for comparison. The energy consumption of the tested vehicles refers to WLTP test conditions with partial load, corresponding to a load of approximately 28% of the vehicle’s maximum payload. The graphs are presented below.

This study relies solely on vehicle manufacturers’ declared technical data, obtained under the standardized WLTP cycle, without the use of proprietary experimental data or real-world testing. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as a comparative and exploratory analysis aimed at identifying general trends and relationships between key technical parameters of electric vehicles, rather than their experimental validation in real-world conditions. Despite these limitations, the approach used allows for an objective comparison of vehicles under identical, standardized conditions.

6.1. Vehicle Energy Consumption per 100 Km and Weight

The graphs below present an analysis of the relationship between vehicle weight and energy consumption in small and medium-sized electric delivery vehicles.

- (a)

Small commercial vehicles.

- (b)

Medium commercial vehicles

The average energy consumption in the WLTP test for small commercial vehicles is 20.4 kWh (

Figure 2). Energy consumption for the three heaviest vehicles is noticeably higher. The Toyota Proace City Long consumes the most energy—a whopping 24.5% more than the average.

Analyzing the results presented in the two graphs, clear differences can be seen between small and medium commercial vehicles in terms of energy consumption and curb weight. Medium commercial vehicles are significantly heavier—in most cases, ranging from approximately 1800 to 2450 kg, while small vehicles range from approximately 1600 to 2400 kg (

Figure 3). This increased weight translates directly into higher energy consumption: medium vehicles require 21 to 30 kWh per 100 km, while small vehicles require 18 to 25 kWh per 100 km.

In both groups, a general trend of increasing energy consumption with increasing vehicle weight can be observed, although this relationship is not entirely linear. Among small vehicles, the heaviest model, the VW ID Buzz Cargo, weighing 2402 kg, consumes 19.1 kWh/100 km, which is not the highest value in its category. This may indicate good aerodynamic efficiency and a powerful drive system. By comparison, among medium-sized vehicles, the MAN eTGE, also one of the heaviest (2442 kg), has a very high energy consumption of 29.9 kWh/100 km. This demonstrates that the impact of weight on energy efficiency becomes more noticeable at higher weights.

The most energy-efficient vehicle among small models is the Citroën Berlingo VAN XL, which consumes only 18.4 kWh/100 km, while among medium-sized vehicles, the Mercedes eVito Extra Long achieved the best result with 21.0 kWh/100 km. The highest energy consumption among small vehicles was recorded by the Toyota Proace City Long (25.4 kWh/100 km), and among medium-sized vehicles, the aforementioned MAN eTGE (29.9 kWh/100 km). The differences between the most and least efficient models in both categories are approximately 7–9 kWh/100 km, which can translate into significant differences in range and operating costs.

Energy consumption in electric delivery vehicles can vary significantly, and is not solely determined by vehicle weight or cargo volume, as it is influenced by many other technical and operational factors. Aerodynamic drag plays a significant role, depending not only on vehicle size but primarily on body shape and drag coefficient. Vehicles with a more angular shape, additional bodywork components, or a less streamlined front generate greater energy losses, especially at higher speeds. Rolling resistance is equally important, depending on the type and condition of tires, their pressure, suspension design, and road surface quality, which can vary significantly even between vehicles of similar weight. Energy consumption is also influenced by the efficiency of the electric drive system, which includes the electric motor, power electronics, transmissions, and control algorithms. Different design solutions and their level of optimization result in different energy losses during driving. Additionally, the efficiency of the energy recuperation system during braking is crucial, especially in urban conditions, as well as the energy demand of auxiliary systems such as heating, air conditioning, and battery thermal management. As a result, total energy consumption is the result of many interacting factors and cannot be assessed solely on the basis of the vehicle’s weight or cargo space.

6.2. Vehicle Range and Energy Consumption per 100 Km

The graphs below present an analysis of the relationship between vehicle range and energy consumption in small and medium-sized electric delivery vehicles.

- (a)

Small commercial vehicles.

- (b)

Medium commercial vehicles

The range of the analyzed vehicles depends, among other things, on the capacity of the traction battery and energy consumption. According to the WLTP test, the VW ID Buzz Cargo achieves the longest range (424 km), more than twice that of the vehicles with the lowest range analyzed. It’s worth noting, however, that the aforementioned vehicle has the largest battery capacity (82 kWh). This difference directly translates to vehicle weight, but the permissible load weight is not noticeably reduced compared to other vehicles. This can be explained by the fact that the VW ID Buzz Cargo is a new design in which the vehicle manufacturer designed a battery compartment beneath the entire cargo area, something that was impossible in older vehicles converted from conventional to electric drive. Differences in range between vehicles stem not only from cargo weight and battery capacity, but also from drive efficiency, body aerodynamics, rolling resistance, assistance systems (e.g., air conditioning, battery heating), and battery management and cargo placement strategies.

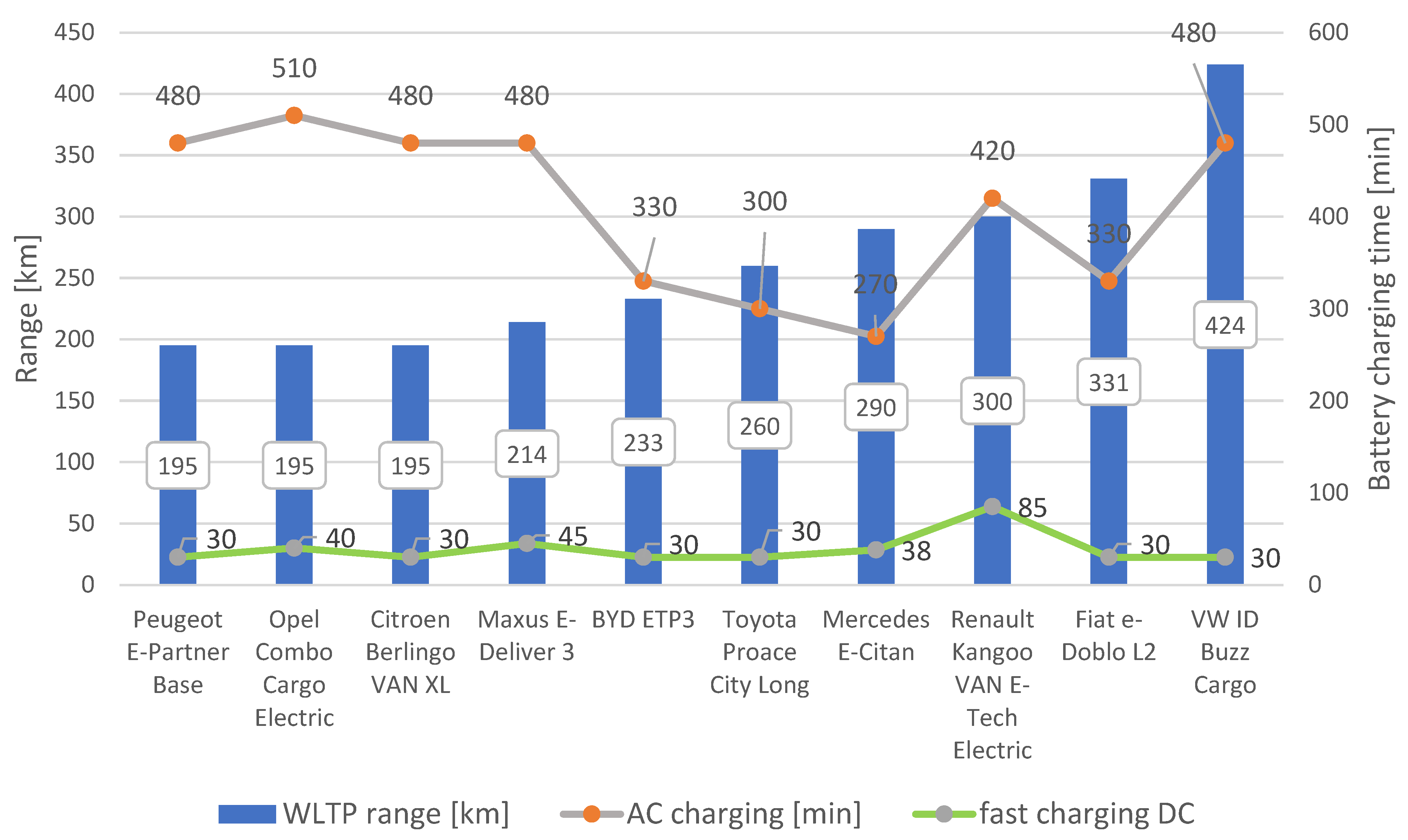

Analysis of the results presented in the figures regarding vehicle range and energy consumption per 100 km reveals a clear correlation between energy efficiency and vehicle size and characteristics. For small delivery vehicles, WLTP range values range from 195 to 424 km, demonstrating the significant variation in the capabilities of individual models (

Figure 4). The Peugeot e-Partner and Opel Combo-e Cargo have the shortest range, while the VW ID Buzz Cargo has the highest. Average energy consumption in this group ranges from 18.7 to 25.4 kWh/100 km, with the lowest values being found in vehicles with lower weight and less powerful engines, while higher values are found in those with larger battery capacity and higher performance, such as the Toyota Proace City Long. It’s noticeable that vehicles with longer ranges don’t always consume proportionally more energy—for example, the VW ID Buzz Cargo, which, despite its highest range, maintains a moderate energy consumption level (20.1 kWh/100 km), indicating good optimization of the drivetrain and vehicle aerodynamics.

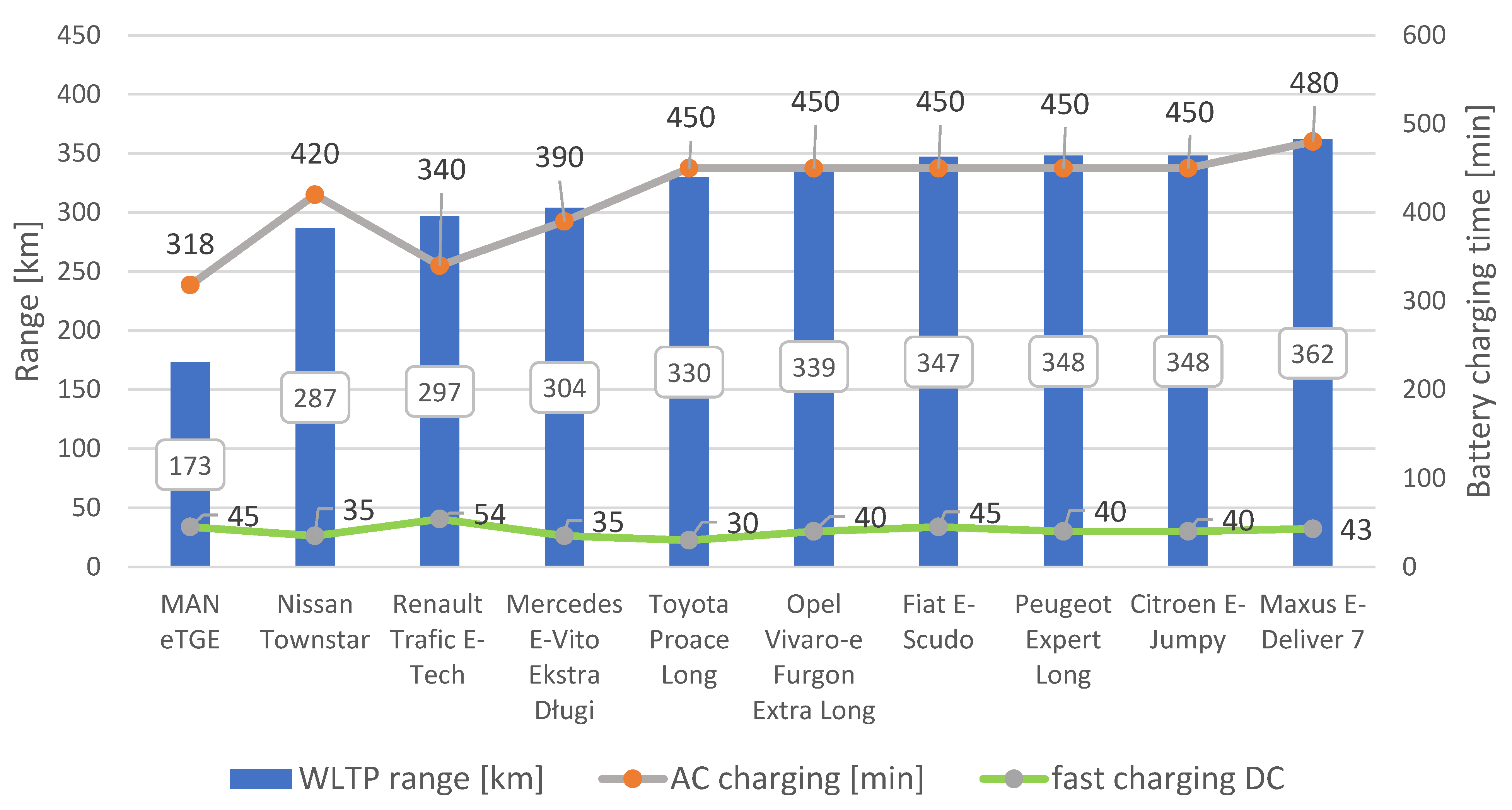

In the case of medium-sized commercial vehicles, higher energy consumption is observed, a consequence of their greater curb weight and carrying capacity (

Figure 5). The WLTP range in this group ranges from 173 to 362 km, with the MAN eTGE achieving the lowest result and the Nissan e-NV200 achieving the highest. Energy consumption per 100 km ranges from 21.0 to 29.9 kWh, indicating that medium-sized vans require on average 3–5 kWh more energy per 100 km than vehicles in the smaller segment. Vehicles with the longest range are not always the most energy-efficient, suggesting that factors such as aerodynamics, payload, and drivetrain characteristics become increasingly important with larger designs. Despite their higher energy consumption, some models—such as the Fiat e-Doblo L2 and Renault Kangoo VAN E-Tech—achieve a relatively good compromise between range and energy consumption, making them competitive in their class.

6.3. Vehicle Range Depending on Payload

The graphs below present an analysis of the relationship between vehicle range and payload of small and medium-sized electric delivery vehicles.

- (a)

Small commercial vehicles.

- (b)

Medium commercial vehicles

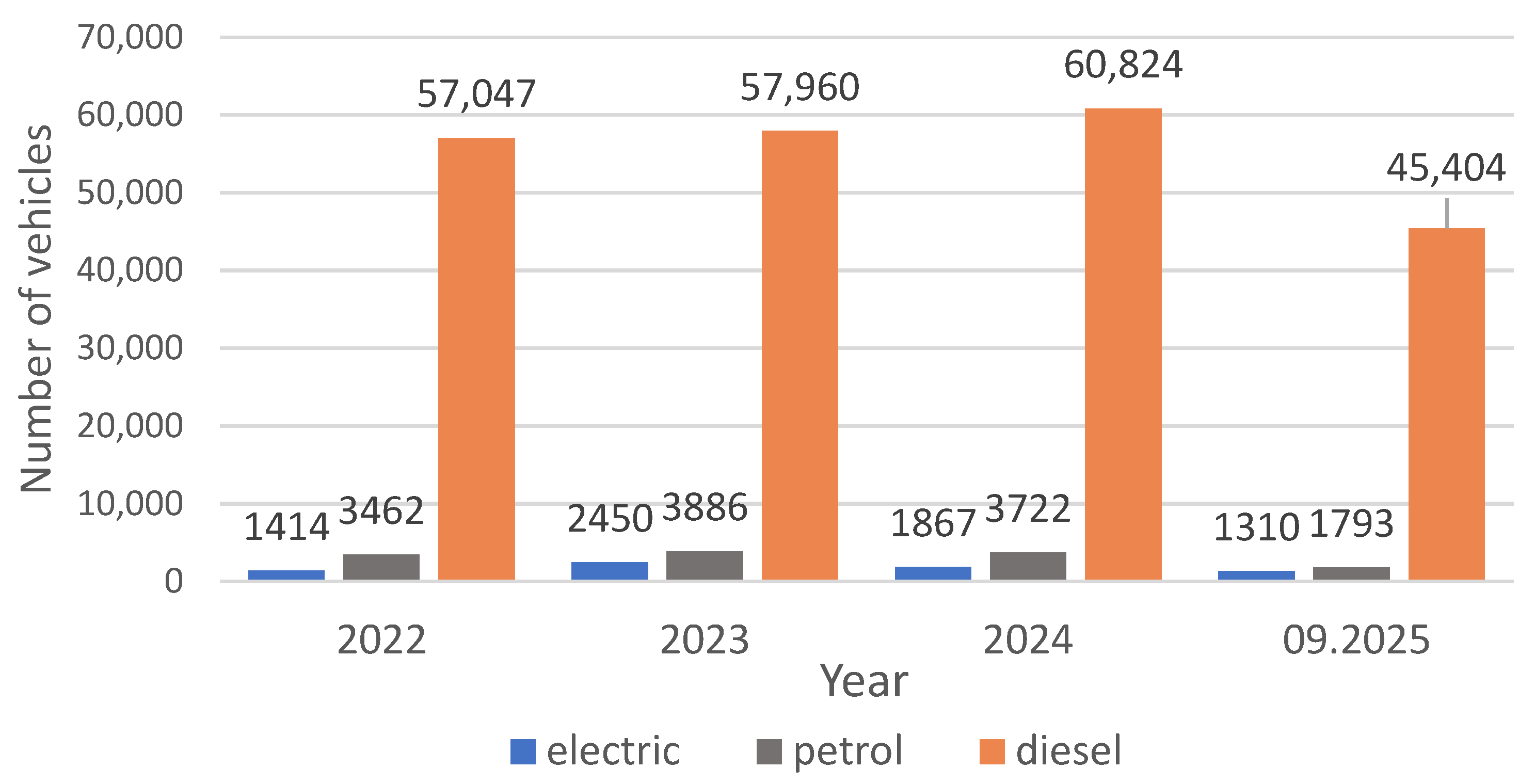

Based on the graphs showing the relationship between vehicle range and maximum payload, significant differences can be seen between small and medium-sized commercial vehicles. For small commercial vehicles, the WLTP range ranges from approximately 195 to 390 km. The Opel Combo Cargo Electric has the shortest range (195 km), while the VW ID Buzz Cargo has the longest—390 km (

Figure 6). It’s worth noting that increased range doesn’t always translate to increased payload. For example, the Renault Kangoo VAN E-Tech Electric has one of the highest payloads (1200 kg), yet only has a range of 260 km. Meanwhile, the VW ID Buzz Cargo, despite its significantly lower payload (424 kg), boasts the highest range in its class. This means that design priorities vary across manufacturers in the small vehicle segment—some models are designed with longer range in mind, others with higher carrying capacity. Overall, there’s no clear correlation between payload weight and range in this group—these parameters seem to be largely independent of each other.

For medium-sized delivery vehicles, the range range is slightly higher, ranging from 173 to 362 km, with an average payload also being higher, ranging from approximately 850 to 1236 kg (

Figure 7). As with smaller vehicles, there’s no clear correlation between payload and range. For example, the MAN eTGE, which has a relatively high payload (1058 kg), achieves the shortest range—just 173 km. Meanwhile, the Maxus E Deliver 7, with a very similar payload (1055 kg), offers a much longer range—362 km. This demonstrates that the factors influencing range are more complex and depend not only on the weight of the cargo being transported, but also on battery capacity, drive efficiency, and vehicle aerodynamics.

6.4. Vehicle Range Depending on Charging Time

The graphs below present an analysis of the relationship between vehicle range and charging time in small and medium-sized electric delivery vehicles.

- (a)

Small commercial vehicles.

- (b)

Medium commercial vehicles

All analyzed electric vehicles could be charged with both alternating current and direct current using fast chargers. It can be seen that for vehicles with a longer range (233 km or more), fast charging times are noticeably shorter and are determined by the individual parameters of each model (maximum charging current). The battery capacity of the small delivery vehicles in the study ranged between 45 and 50 kWh. The VW ID Buzz Cargo was an exception. Stored energy density is the main determinant of electric vehicle range.

An analysis of the presented results regarding vehicle range and battery charging times indicates significant variation among both small and medium-sized delivery vehicles. In the case of small delivery vehicles (

Figure 5), it is noticeable that WLTP range values range from approximately 195 to 480 km. The VW ID Buzz Cargo achieves the longest range (480 km), while the Peugeot e-Partner achieves the shortest (195 km). At the same time, charging times using alternating current (AC) range between 330 and 510 min, with the highest values observed for vehicles with larger battery capacity, such as the VW ID Buzz Cargo and Opel Combo-e Cargo (

Figure 8). Charging times using direct current (DC), on the other hand, are significantly shorter, in most cases ranging from 30 to 85 min, confirming that fast charging technology significantly shortens the time required to recharge. In the context of the relationship between range and charging time, it can be observed that vehicles with longer ranges typically have longer AC charging times, but not necessarily proportionally longer DC charging times, suggesting limitations in charger power and battery thermal management.

In the group of medium-sized commercial vehicles (

Figure 9), range values are similar but generally lower compared to the smaller vehicle segment, ranging from 173 to 362 km. The MAN eTGE has the lowest range, while the Nissan e-NV200 has the highest. AC charging times are also high, ranging from 318 to 480 min, which is typical for larger vehicles equipped with larger batteries. DC charging, on the other hand, remains similar to smaller vehicles, ranging from 30 to 45 min. Analyzing the relationship between range and charging time, it can be seen that despite the generally longer AC charging times compared to the small vehicle segment, the ranges of medium-sized vans are not significantly longer, indicating a trade-off between vehicle weight, battery capacity, and energy efficiency.

6.5. MCDM Analysis for Electric Light Commercial Vehicles

A set of small electric delivery vehicles (eLCVs) comprising 10 alternatives was analyzed. The input data was 100% complete. The alternatives were evaluated using four measurable technical and operational criteria: range (km), charging time (min), energy consumption (kWh/100 km), and maximum payload weight (kg). The criteria were classified as stimulants and destimulants: range and maximum payload weight were treated as stimulants (higher values are more favorable), while charging time and energy consumption were treated as destimulants (lower values are more favorable). The study adopted the objective CRITIC (Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation) weighting method, which determines the importance of criteria based on their variability and interdependencies (correlations) between criteria, reducing the risk of assigning high weights to features carrying redundant information (

Table 3 and

Table 4) [

16,

17,

18,

19].

The TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method was used to construct the ranking. In this method, alternatives are ordered by their similarity to the ideal solution and their distance from the anti-ideal solution [

16,

17,

18,

19]. In the first step, min-max normalization was performed to the interval (0, 1), while taking into account the direction of preference. For the stimulants (1), and for destimulants (2) the following were used:

Then, the normalized weighted matrix

, was calculated, the ideal point

and the anti-ideal point

were determined as the maximum and minimum, respectively, over the columns of matrix V, and the Euclidean distances were calculated (3, 4):

The closeness to ideal index was defined as follows (5):

- (a)

Small commercial vehicles.

Table 5 presents the ranking of small commercial vehicle models obtained using the TOPSIS method with weights determined using the CRITIC method.

To assess the stability of the ranking, additional TOPSIS calculations were performed for Entropy and equal weights. In each weighting variant, the leader of the ranking remained unchanged (Toyota Proace City Long), while changes mainly concerned the order in positions 2–5. The correlation between the rankings was high (Spearman rank correlation between CRITIC and Entropy: 0.867, and between CRITIC and equal weights: 0.915), confirming the overall stability of the conclusions while simultaneously confirming the sensitivity of the middle part of the ranking to the weighting method.

- (b)

Medium commercial vehicles.

Table 6 presents the ranking of medium commercial vehicle models obtained using the TOPSIS method with weights determined using the CRITIC method.

To assess the stability of the results, additional TOPSIS calculations were performed for entropy weights and equal weights. The leader of the ranking remained unchanged (Renault Trafic E-Tech) across all weighting variants, which strengthens the validity of the main conclusion. Differences were primarily found in the middle and lower parts of the ranking. The agreement between the rankings was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient: CRITIC vs. Entropy: ρ = 0.915; CRITIC vs. equal: ρ = 0.624; Entropy vs. equal: ρ = 0.442. The high agreement between CRITIC and Entropy indicates that the ranking is largely stable with objective, data-driven weighting methods. The lower agreement with equal weights suggests that assuming equal importance of criteria may significantly alter the ordering of some alternatives, particularly beyond the leader.

7. Conclusions

In summary, the main scientific contribution of this work is a systematic comparative analysis of electric delivery vehicles, taking into account four key operational parameters: energy consumption, range, charging time, and payload.

Energy consumption is significantly lower in the small delivery vehicle segment, due to their smaller weight and dimensions. This confirms their high energy efficiency and suitability for use in urban logistics, where low operating costs are crucial. Medium-sized vehicles are characterized by higher energy consumption, a compromise resulting from their larger size and transport capacity.

The analysis revealed significant differences in range between small and medium-sized zero-emission delivery vehicles. Small vehicles offer a favorable range-to-weight ratio, making them particularly suitable for urban applications. At the same time, modern models such as the VW ID Buzz Cargo and Nissan e-NV200 boast relatively long ranges in both segments, increasing their operational flexibility and fleet appeal.

Payload remains a parameter that clearly favors medium-sized vehicles, which better meet the requirements of transporting larger and heavier loads, especially in regional logistics. At the same time, the analysis did not reveal a strong correlation between payload and range, although there is a noticeable tendency for vehicles with longer ranges to often offer lower payloads. This indicates a design compromise between battery weight and gross vehicle weight.

Charging time, especially when using alternating current (AC), is dependent on battery capacity and vehicle range. Using fast charging with direct current (DC) significantly reduces recharging times regardless of vehicle segment. Models with the longest ranges, such as the VW ID Buzz Cargo and Nissan e-NV200, achieve the best range-to-charging time ratio, making them the most efficient for fleet operational continuity.

In the context of the future implementation of electric delivery vehicles in corporate fleets, range, energy efficiency, payload, and charging time will be key, supported by the development of charging infrastructure and EU climate regulations. The study results indicate that vehicles that optimally balance these four parameters have the greatest implementation potential, contributing to emission reduction and the development of sustainable urban and regional mobility.

CRITIC’s objective weighting analysis showed that the importance of criteria differed between segments: for small eLCVs, maximum payload (0.291) and energy consumption (0.262) were the most important, while for medium-sized eLCVs, charging time (0.329) proved crucial, followed by maximum payload (0.252). Using TOPSIS (CRITIC–TOPSIS variant) allowed us to determine preference rankings: in the small eLCV group, the Toyota Proace City Long received the highest rating (C* = 0.627), and in the medium-sized eLCV group, the Renault Trafic E-Tech (C* = 0.769). The results indicate that these models represent the most favorable compromise between the analyzed criteria within their respective vehicle segments, while maintaining the ranking’s sensitivity to weighting primarily in the middle of the ranking.

In the coming years, the adoption of electric delivery vehicles in corporate fleets will largely depend on the expansion of charging infrastructure and the implementation of European climate regulations, which aim to achieve neutrality in transport by 2035. The results of this study indicate that vehicles with longer range and greater payload will be preferred in large-scale deployment scenarios, as they reduce the number of journeys and minimize charging-related downtime. At the same time, energy efficiency and charging times remain critical parameters determining the operational viability of vehicles. As charging networks expand and regulations promoting zero-emission vehicles are introduced, electric light commercial vehicles have the potential to significantly increase their share in urban and regional logistics, contributing to reduced emissions and increased sustainable mobility.