Advanced Energy Collection and Storage Systems: Socio-Economic Benefits and Environmental Effects in the Context of Energy System Transformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- –

- Technology-specific databases from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), International Energy Agency (IEA), Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), and Fraunhofer ISE.

- –

- Macroeconomic and energy statistics from Eurostat, Asian Development Bank (ADB), U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), and national energy authorities.

- –

- Peer-reviewed scientific literature (2020–2025) on PV/T, battery technologies, hydrogen storage, and thermal energy storage (TES).

- –

- Policy documents and legislative reports from the European Commission, U.S. Department of Energy, and other government agencies.

- –

- Technology Scope: Photovoltaic-Thermal (PV/T) Hybrid Systems; Advanced Batteries (Sodium-ion, Solid-state, Lithium-sulfur); Hydrogen-Based Storage (Electrolysis, Power-to-Gas); Thermal Energy Storage (Molten Salt, Phase Change Materials).

- –

- job creation per MW of installed ECSS capacity;

- –

- GDP contributions from manufacturing, installation, and operation;

- –

- trade balance effects via fossil fuel import substitution.

- –

- baseline scenario: limited ECSS expansion; continuation of current policies.

- –

- moderate deployment scenario: moderate ECSS growth aligned with national renewable targets.

- –

- accelerated deployment scenario: aggressive scale-up of ECSS driven by enhanced policy support.

- –

- potential uncertainty in future technology cost projections.

- –

- limited availability of real-world data for emerging technologies (e.g., solid-state batteries).

- –

- regional policy differences not fully captured in global models.

4. Results

- –

- energy storage facility—an installation enabling the storage of energy, including electricity storage facilities (Art. 3, point 10 k);

- –

- electricity storage—the deferral, within the power system, of the final consumption of electricity, or its conversion into another form of energy, its storage, and subsequent reconversion into electricity (Art. 3, point 59);

- –

- energy storage—the storage of electricity or the conversion of electricity into another form of energy, its storage, and later use in the form of a different energy carrier (Art. 3, point 59a).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Advanced energy collection and storage systems are becoming essential components of low-carbon energy systems. Their deployment offers substantial economic benefits, including reduced energy costs, improved energy security, and enhanced job creation. While significant capital investment and policy reform are required to overcome current barriers, the long-term advantages of ECSS are compelling. Advanced energy collection and storage systems (ECSSs) demonstrate significant economic potential across diverse technologies and regions. Our analysis confirms that ECSS technologies—including advanced batteries, hydrogen storage, thermal energy storage (TES), and photovoltaic-thermal (PV/T) systems—are rapidly reducing in cost due to technological innovation and scaling effects. Battery storage costs are projected to fall below USD 50/kWh by 2050, while green hydrogen may become competitive at around USD 1.2/kg within the same timeframe. These trends are expected to make ECSS a central pillar of low-carbon energy systems worldwide.

- Deployment of ECSS technologies can deliver substantial macroeconomic benefits, including lower energy costs, increased energy security, and job creation. Comparative analysis across six major economies reveals that ECSS deployment can reduce electricity costs by 5–12%, cut fossil fuel imports by up to 25%, and stimulate GDP growth ranging from 0.8% to 1.2% by 2050. Additionally, millions of new jobs could potentially be created under supportive policy conditions in the ECSS value chain, particularly in battery manufacturing, hydrogen production, and infrastructure development. These benefits are most pronounced in regions with proactive energy policies and high renewable energy penetration.

- Hydrogen-based storage and thermal energy storage (TES) technologies play a crucial role in long-duration and seasonal energy storage, complementing batteries. While battery technologies are well-suited for short-term storage and grid balancing, hydrogen and TES provide essential services for long-duration applications and industrial decarbonization. Countries such as Japan and Germany are already leveraging hydrogen and TES to improve energy system resilience and reduce fossil fuel dependency, particularly in heating and heavy industry sectors.

- Accelerated ECSS deployment requires targeted policy interventions and integrated planning frameworks. Our scenario modeling demonstrates that ambitious policy support—including investment tax credits, carbon pricing, and dedicated research funding—can dramatically scale up ECSS adoption and maximize economic returns. Policy instruments such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, the EU Net Zero Industry Act, and national hydrogen strategies are critical to overcoming investment barriers and market risks associated with ECSS technologies.

- In this work, the Model of the Long-Term Economic Impact of Energy Collection and Storage Systems (ECSS) was proposed. The proposed model highlights the considerable long-term economic potential associated with ECSS implementation. Job creation emerged as the primary contributor to GDP growth. The model can be tailored to different national contexts by incorporating country-specific data. It is suitable for scenario-based analysis using tools such as Excel or other modeling platforms. Widespread adoption of ECSS could serve as a powerful driver of economic development. Among the modeled impacts, employment effects contributed most significantly to long-term growth. This model offers valuable support for strategic policy formulation and national energy planning, enabling the analysis of various policy pathways, including both moderate and ambitious ECSS deployment strategies.

- Future research and policy development should prioritize hybrid energy storage systems, supply chain risk mitigation, and deployment in developing economies. Despite significant progress, gaps remain in the integration of hybrid ECSS solutions (e.g., combining batteries with hydrogen or TES) and in the analysis of their systemic impacts. In addition, global supply chains for critical materials such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel require diversification and improved circularity to reduce vulnerabilities. Finally, there is an urgent need to expand ECSS research and deployment in developing regions, where these technologies can provide cost-effective solutions for energy access and climate resilience. Therefore, recommended actions include establishing dedicated ECSS financing schemes via green bonds and climate funds; enhancing carbon pricing mechanisms to favor energy storage integration; and promoting international research collaboration to reduce technology costs. Policymakers should prioritize integrated approaches combining regulatory support, market incentives, and research investments to maximize the socio-economic returns of ECSS. Future research should focus on life-cycle cost analysis, system optimization, and cross-sectoral integration to unlock the full potential of these technologies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling Up Electrolysers to Meet Climate Targets; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K.; Tyagi, V.V.; Jeyraj, A.; Selvaraj, L.; Rahim, N.A.; Tyagi, S.K. Recent advances in solar photovoltaic systems for emerging trends and advanced applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Su, B.; Guo, S.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, X. Advancements in Energy-Storage Technologies: A Review of Current Developments and Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Serrano-Arévalo, T.I.; Ochoa-Barragán, R.; Ramírez-Márquez, C.; El-Halwagi, M.; Abdel Jabbar, N.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Energy Storage: From Fundamental Principles to Industrial Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, B.; Syri, S. Electrical energy storage systems: A comparative life cycle cost analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Ryan, S.E.; Stern, P.C.; Janda, K.; Rochlin, G.; Spreng, D.; Pasqualetti, M.J.; Wilhite, H.; Lutzenhiser, L. Integrating social science in energy research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N. The economics of climate change: The stern review. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). Battery Pack Prices Hit New Low in 2025. 2025. Available online: https://taiyangnews.info/business/bloombergnef-battery-pack-prices-hit-new-low-in-2025 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Du, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, J. The economic impact of energy storage co-deployment on renewable energy in China. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2023, 15, 035905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Net Zero Industry Act and European Green Deal Industrial Plan: Progress Report 2025; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Long-Duration Energy Storage; DOE Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). Hydrogen Strategy Progress Report; METI: Tokyo, Japan, 2024.

- Agora Energiewende. How Is Germany Transforming Its Energy System? 2025. Available online: https://www.agora-energiewende.org/about-us/the-german-energiewende/how-is-germany-transforming-its-energy-system (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Pagliaro, M. Renewable Energy Systems: Enhanced Resilience, Lower Costs. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 201900791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Armada, M.; Sanchez, M.J. Potential utilization of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) in the major European electricity markets. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markandya, A.; González-Eguino, M. Integrated Assessment for Identifying Climate Finance Needs for Loss and Damage: A Critical Review. In Loss and Damage from Climate Change. Climate Risk Management, Policy and Governance; Mechler, R., Bouwer, L., Schinko, T., Surminski, S., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.W.; Rosa, E.A.; Schor, J.B. Could working less reduce pressures on the environment? A cross-national panel analysis of OECD countries, 1970–2007. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 691–700, ISSN 0959-3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Manthiram, A. Sustainable Battery Materials for Next-Generation Electrical Energy Storage. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Ni, H.; Pan, H. Rechargeable Mild Aqueous Zinc Batteries for Grid Storage. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2020, 1, 2000026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakymchuk, A. The Carbon Dioxide Emissions’ World Footprint: Diagnosis of Perspectives. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol.–Organ. Manag. Ser. 2024, 195, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.R.; Guzović, Z.; Duić, N.; Boldyryev, S. Energy transition in south east and central Europe. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, XI–XX. [Google Scholar]

- Kropp, T.; Lennerts, K.; Fisch, M.N.; Kley, C.; Wilken, T.; Marx, S.; Zak, J. The contribution of the German building sector to achieve the 1.5 °C target. Carbon Manag. 2022, 13, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, M.R.; Biswas, W.K.; Selvan, C.P. Advancements and challenges in solar photovoltaic technologies: Enhancing technical performance for sustainable clean energy—A review. Sol. Energy Adv. 2025, 5, 100084, ISSN 2667-1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zoras, S.; Zhang, J. Comprehensive review of the recent advances in PV/T system with loop-pipe configuration and nanofluid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Q.; Su, M. Drivers of decoupling economic growth from carbon emission—An empirical analysis of 192 countries using decoupling model and decomposition method. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Lu, C.; Li, H.; Yang, Z. A region-based low-carbon operation analysis method for integrated electricity-hydrogen-gas systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122230, ISSN 0306-2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakymchuk, A.; Maxand, S.; Lewandowska, A. Economic Analysis of Global CO2 Emissions and Energy Consumption Based on the World Kaya Identity. Energies 2025, 18, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.ticketforchange.org/become-a-changemaker-mooc (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Riahi, K.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Emmerling, J.; Fujimori, S.; Kc, S.; Kriegler, E.; O’Neill, B. The Shared Socio-economic Pathways: Trajectories for human development and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, C.; Adlen, E.; Beddington, J.; Carter, E.A.; Fuss, S.; Mac Dowell, N.; Minx, J.C.; Smith, P.; Williams, C.K. The technological and economic prospects for CO2 utilization and removal. Nature 2019, 575, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhou, D. Impact of renewable energy investment on carbon emissions in China—An empirical study using a nonparametric additive regression model. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.J.; Caldeira, K.; Matthews, H.D. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science 2010, 329, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Brown, A.; Culver, J.N.; Lundgren, C.A.; Xu, K.; Wang, Y.; et al. Architecturing hierarchical function layers on self-assembled viral templates as 3D nano-array electrodes for integrated Li-ion microbatteries. Nano Lett. 2012, 13, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzywacz, M.; Sokołowski, M.M.; Wierzbowski, M. Ramy i bariery prawne magazynowania energii wobec rosnącego wykorzystania magazynów energii elektrycznej na świecie. In Państwo a Gospodarka. Zasady—Instytucje—Procedury. Księga Jubileuszowa Dedykowana Profesor Bożenie Popowskiej; Lissoń, P., Strzelbicki, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Poznańskie: Poznań, Poland, 2020; pp. 305–315. Available online: https://open.icm.edu.pl/items/01b5f409-920c-411c-af16-111645602528 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Pająk, T.; Jura, P.; Szczotka, K.; Szymiczek, J.; Pelczar, S.; Habryń, A.; Zych, P. Innowacje w Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii; Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Technicznej w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2024; ISBN 978-83-68422-01-6. Available online: https://www.pie.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Monografia-naukowa-konferencji-INNOWACJE-W-ODNAWIALNYCH-ZRODLACH-ENERGII-2024.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Chmielewski, A.; Kupecki, J.; Szabłowski, Ł.; Fijałkowski, K.J.; Zawieska, J.; Bogdziński, K.; Kulik, O.; i Adamczewski, T. Dostępne i Przyszłe Formy Magazynowania Energii; Fundacja WWF Polska: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-60757-55-0. [Google Scholar]

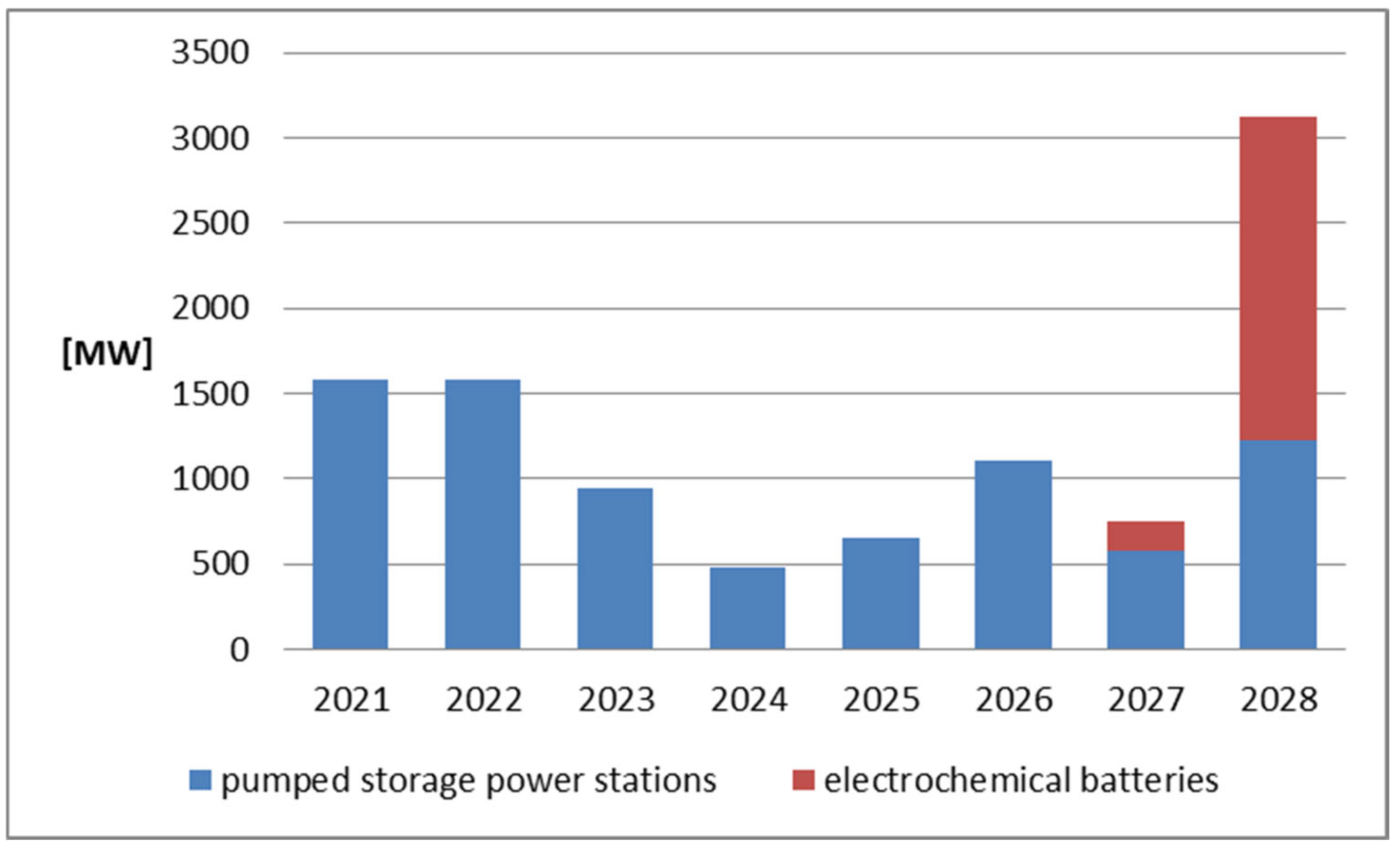

- Adamska, B.; Kopeć, S.; Lach, Ł.; Szczeciński, P.; Wrocławski, M. Wpływ rozbudowy infrastruktury magazynów energii na rozwój gospodarczy w Polsce—Prognoza do 2040 roku. Analizy AGH. Komunikat 2/2022. 2022. Available online: https://psme.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/RAPORT_PSME_AGH.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Fijak, W.; Miłkowska, M. Regulacje prawne magazynowania energii i ich wpływ na rozwój gospodarczy Polski. In Rola Magazynów Energii we Współczesnej Gospodarce; Pawełczyk, M., Ed.; IUS PUBLICUM, Katowice: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; pp. 217–258. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jakub-Kmiec-2/publication/378707986_Rola_magazynow_energii_w_rozwoju_lokalnych_spolecznosci_energetycznych/links/65e60126e7670d36abfd147b/Rola-magazynow-energii-w-rozwoju-lokalnych-spolecznosci-energetycznych.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Sokołowski, M.M. European Law on Combined Heat and Power; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Babiarz, A.; Kolasa, P. Magazyny energii po zmianach prawa energetycznego—Czy zakres zmian wystarczająco znosi bariery rozwoju? Nowa Energ. 2021, 2, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z dnia 23 lipca 2023 r. o zmianie ustawy—Prawo energetyczne. Dziennik Ustaw z 2023 poz. 1681. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20230001681 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Dyrektywa Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2019/944 z Dnia 5 Czerwca 2019 r. w Sprawie Wspólnych Zasad Rynku Wewnętrznego Energii Elektrycznej Oraz Zmieniającą Dyrektywę 201227/UE. Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on Common Rules for the Internal Market for Electricity and Amending Directive 2012/27/EU. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/944/oj (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 20 Maja 2021 r. o Zmianie ustawy—Prawo Energetyczne Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw. Dz. U. z 2021 r. poz. 1093. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20210001093 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 8 Lutego 2023 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Szczególnych Rozwiązaniach w Zakresie Niektórych Źródeł Ciepła w Związku na Rynku Paliw Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw. Dziennik Ustaw z 2023 poz. 295. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20230000295 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Adamska, B. Magazyny energii niezbędnym elementem transformacji energetycznej. Energetyka Rozproszona 2022, 7, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horzela-Mis, A.; Semrau, J. Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Poland’s Construction Sector: Simulating Renewable Energy and Storage Integration. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 1, 6646016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagusiak, B. Bezpieczeństwo energetyczne a bezpieczeństwo socjalne. Energ. Gigawat 2015, 10. Available online: https://www.cire.pl/pliki/2/jagusiakboguslawbezpieczenstwosocjalne.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Ehrenhalt, W. Transformacja Energetyczna—Szansa i Konieczność dla Polskiej Gospodarki. Związek Przedsiębiorców i Pracodawców. 2025. Available online: https://zpp.net.pl/transformacja-energetyczna-szansa-czy-koniecznosc-dla-polskiej-gospodarki/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Magazynowanie Energii Elektrycznej. Urząd Regulacji Energetyki. 2024. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/urzad/informacje-ogolne/edukacja-i-komunikacja/publikacje/magazynowanie-energii-elektryc/12061,Magazynowanie-Energii-Elektrycznej.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Przybylska, M. Energetyka prosumencka w rozwoju energii odnawialnej. In Kierunki Rozwoju Branży Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii w Polsce; Skorupska, A., Ed.; Aspekty Prawne; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; pp. 45–64. ISBN 978-83-8270-262-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrektywa Parlamentu Europejskiego 2009/28/WE w Sprawie Promowania Stosowania Energii ze Źródeł Odnawialnych (…). Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/28/oj (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Klimatu i Środowiska z Dnia 21 Października 2021 r. w Sprawie Rejestru Magazynów Energii Elektrycznej. Dziennik Ustaw z 2021 r. poz. 2010. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20210002010 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2015/1222 z dnia 24 lipca 2015 r. Ustanawiające Wytyczne Dotyczące alokacji Zdolności Przesyłowych i Zarządzania Ograniczeniami Przesyłowymi. Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/1222 of 24 July 2015 Establishing a Guideline on Capacity Allocation and Congestion Management (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/1222/oj (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Zalecenie Komisji z Dnia 2023 r. w Sprawie Magazynowania Energii—Wspieranie Zdekarbonizowanego i Bezpiecznego Systemu Energetycznego UE. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32023H0320(01) (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Energy Regulatory Office (URE). 2024. Available online: https://eru.gov.cz/en (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- What are the Sustainable Development Goals? 2024. Available online: https://www.sightsavers.org/policy-and-advocacy/global-goals/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAy9msBhD0ARIsANbk0A8x3Z2OnYDAmW8AnYh0x_J1zig90-bAHcaScOs_SQ2D5UOCrks7GksaApPaEALw_wcB (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Czaplicki, R.; Jeznach, Ł.; Jabczuga, M.; Kucek, B.; Kasprzak, N.; Gnat, Ł. Magazyny OZE jako narzędzie wychodzenia z kryzysu energetycznego w Polsce i zabezpieczenie na przyszłość. In Kryzys Energetyczny: Wyzwanie Strategiczne dla Polski. Raporty Słuchaczy KSAP XXXIV Promocji Ignacy Łukasiewicz; Stankiewicz, P., Ed.; Krajowa Szkoła Administracji Publicznej im. Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Lecha Kaczyńskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; pp. 135–167. ISBN 978-83-61713-42-5. [Google Scholar]

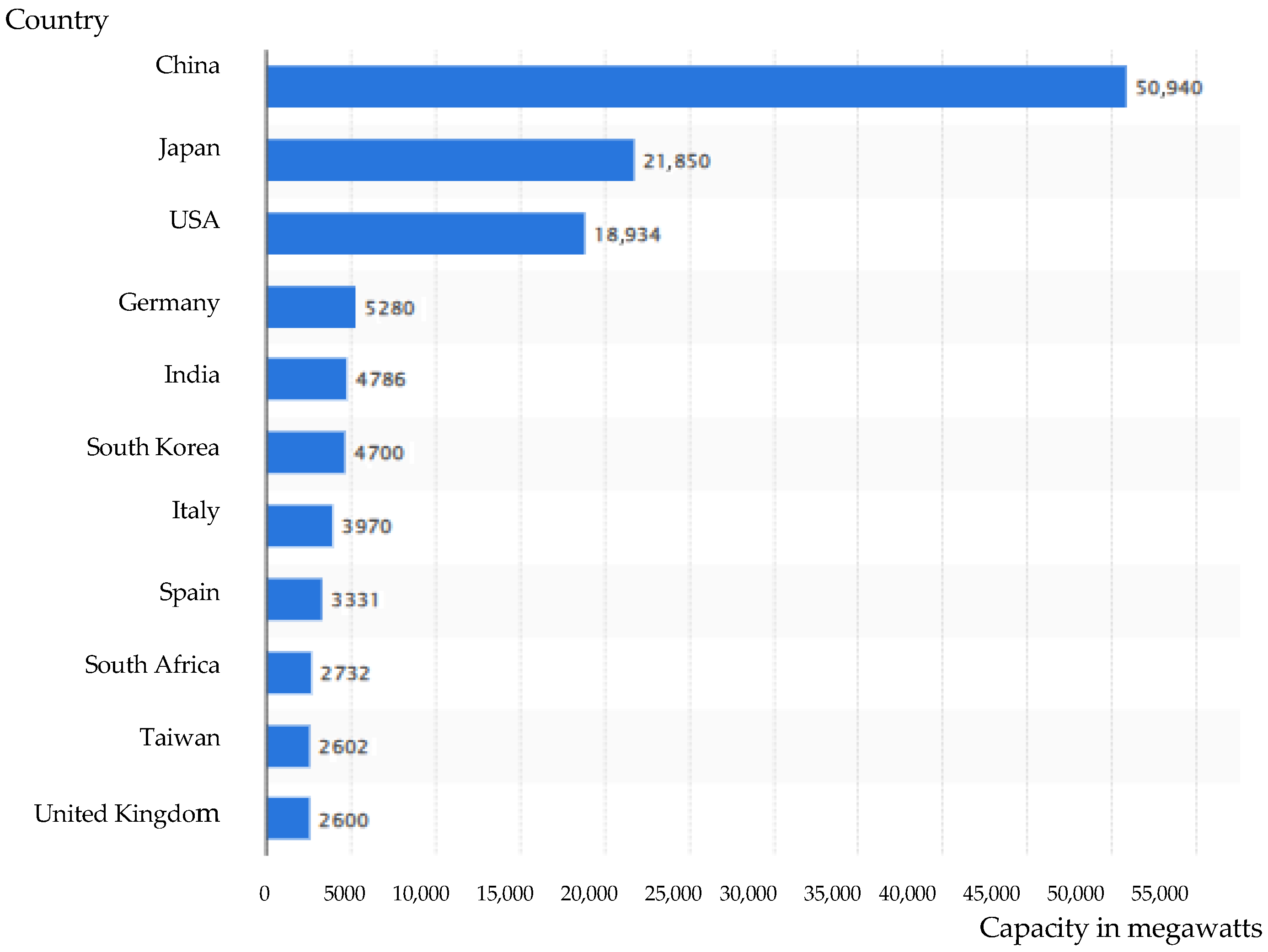

- Statista. Capacity of Pumped Storage Hydropower Worldwide in 2024, by Leading Country. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/689667/pumped-storage-hydropower-capacity-worldwide-by-country/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Statista. Pure Pumped Storage Hydropower Capacity Worldwide from 2010 to 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1304113/pumped-storage-hydropower-capacity-worldwide/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Fouquet, R. Consumer Surplus from Energy Transitions. Energy J. 2023, 39, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economics: The Economics of Biophysical Equilibrium and Moral Growth; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1977; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmann, K. Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Joint Research Centre; Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Pagani, F.; Banja, M.; Muntean, M.; Schaaf, E.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Becker, W.E.; et al. GHG Emissions of All World Countries; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CO2 Emissions from EU Territorial Energy Use: −2.8%. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230609-2 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ellerman, A.D.; Marcantonini, C.; Zaklan, A. The European Union Emissions Trading System: Ten Years and Counting. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2015, 10, rev014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, I.; Wang, R.; Ling-Chin, J.; Paul Roskilly, A. Solid oxide fuel cells with integrated direct air carbon capture: A techno-economic study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 315, 118739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, C.; Stern, N.; Stiglitz, J.E. “Carbon Pricing” Special Issue in the European Economic Review. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 127, 103440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhringer, C.; Löschel, A. Promoting Renewable Energy in Europe: A Hybrid Computable General Equilibrium Approach. Energy J. 2006, 27, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenhofer, O.; Knopf, B.; Barker, T.; Baumstark, L.; Bellevrat, E.; Chateau, B.; Criqui, P.; Isaac, M.; Kitous, A.; Kypreos, S.; et al. The Economics of Low Stabilization: Model Comparison of Mitigation Strategies and Costs. Energy J. 2010, 31, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Trends and Projections in Europe 2021: Tracking Progress Towards Europe’s Climate and Energy Targets; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; 41p, ISBN 978-92-9480-392-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, A.; Mittal, S.; Lamboll, R.D.; Grant, N.; Bernie, D.; Gohar, L.; Hawkes, A.; Köberle, A.; Rogelj, J. Adjusting 1.5 degree C climate change mitigation pathways in light of adverse new information. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.M.; Le Quéré, C.; Mayot, N.; Olsen, A.; Bakker, D.C.E. Fingerprint of climate change on Southern Ocean carbon storage. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2023, 37, e2022GB007596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J.; Oates, W. The Theory of Environmental Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X.; Lu, L.C.; Chiu, Y.H. How the European Union reaches the target of CO2 emissions under the Paris Agreement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1836–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 200–250. [Google Scholar]

- Official Site of the European Statistics Service. 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/about/departments-and-executive-agencies/eurostat-european-statistics_en (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Gross National Income (GNI) Indicator; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshwan, R.; Shi, X.L.; Zhang, M.; Yue, Y.; Liu, W.D.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Liang, D.; Chen, Z.-G. Advances and challenges in hybrid photovoltaic-thermoelectric systems for renewable energy. Appl. Energy 2025, 380, 125032, ISSN 0306-2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Haque, R.; Jahirul, M.I.; Rasul, M.G.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Hassan, N.M.S.; Mofijur, M. Advancing energy storage: The future trajectory of lithium-ion battery technologies. J. Energy Storage 2025, 120, 116511, ISSN 2352-152X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Kintner-Meyer, M.C.W.; Lu, X.; Choi, D.; Lemmon, J.P.; Liu, J. Electrochemical energy storage for green grid. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3577–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhu, B.; Jiang, X.; Han, G.; Li, S.; Lau, C.H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, L. Symbiosis-inspired de novo synthesis of ultrahigh MOF growth mixed matrix membranes for sustainable carbon capture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2114964119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohe, G.W.; Tol, R.S. The Stern Review and the Economics of Climate Change: An Editorial Essay. Clim. Change 2008, 89, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distribution of Carbon Dioxide Emissions Worldwide in 2022, by Sector. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1129656/global-share-of-co2-emissions-from-fossil-fuel-and-cement (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Fischer, C.; Newell, R.G. Environmental and technology policies for climate mitigation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzig, F.; Agoston, P.; Goldschmidt, J.C.; Luderer, G.; Nemet, G.; Pietzcker, R.C. The underestimated potential of solar energy to mitigate climate change. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Year | Technology | Methodology | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pandey et al. [2] | 2020 | PV/T systems | Techno-economic review | Combined efficiency > 70%, strong potential in buildings | Limited large-scale deployment |

| Liu et al. [3] | 2021 | Advanced batteries | Experimental & modeling | Higher energy density, improved safety | High material costs |

| Zakeri & Syri [6] | 2022 | Energy storage systems | System modeling | Storage improves grid flexibility | Policy assumptions |

| Sovacool et al. [7] | 2023 | Integrated ECSS | Comparative analysis | Strong socio-economic benefits | Regional focus |

| IEA [4] | 2024 | Hydrogen storage | Scenario analysis | Seasonal storage potential | Infrastructure gaps |

| Technology | LCOS (USD) | Applications | Maturity Level | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battery Storage | 50–90 USD/kWh | Grid balancing, EVs, residential | High (commercial) | BloombergNEF, 2025 [9] |

| Hydrogen Storage | 1.2–4.5 USD/kg | Long-duration storage, industry, mobility | Medium (early commercial) | IEA, 2024 [4] |

| Thermal Storage | 20–30 USD/MWh | Industrial heat, district heating, CSP plants | High (niche mature) | IRENA, 2024 [1] |

| Country (Region) | Energy Cost Reduction | Fossil Fuel Import Reduction | GDP Impact (Direct & Indirect) | Job Creation | Main ECSS Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union (EU) | 5–12% reduction in wholesale electricity prices by 2040 (EC) | ~15% reduction in gas imports by 2035 (EU Energy Outlook) | Estimated +0.8% GDP growth by 2050 from ECSS investments [11] | +850,000 new jobs by 2035 in ECSS industries | Batteries (Li-ion, Na-ion), Thermal Energy Storage (TES), Hydrogen |

| United States | 4–9% retail electricity price reduction by 2040 [1,4,9,11,73] | Oil & gas import reductions in selective regions, ~8% by 2040 | Up to USD 80 billion in private investment driven by IRA policies [69,70,78] | +520,000 jobs by 2030 in ECSS (battery & hydrogen sectors) | Batteries (Li-ion, Solid-state), Hydrogen, Long-duration Storage |

| China | Electricity price stabilization (region-specific) | ~20% reduction in coal & gas dependency by 2040 [10,69,78] | Estimated +1.2% GDP increase by 2050 due to large-scale storage [81,84,85] | +1.5 million new jobs by 2040 (mainly in batteries & hydrogen) | Batteries (Li-ion, LFP), Hydrogen Storage, PV-Thermal Hybrids |

| Japan | Up to 7% reduction in natural gas imports in pilot regions by 2030 [13,27] | Moderate, localized reductions in fossil fuel imports | Industrial growth linked to hydrogen economy (up to USD 35 billion annually by 2050) | ~150,000 jobs in hydrogen & advanced storage by 2035 | Hydrogen Storage, Thermal Storage, PV/T Systems |

| India | ~6–10% reduction in retail energy costs in urban regions by 2040 [1] | ~10% decrease in energy imports by 2040 | Expected USD 25 billion in energy savings & productivity gains by 2050 | +600,000 new jobs by 2040, mainly in decentralized storage | Batteries (Na-ion, Li-ion), PV/T Systems, Hydrogen Storage |

| Australia | ~8% electricity cost savings in regions with high renewable penetration [3,17,77] | Local reductions in LNG imports (~5–7% by 2035) | Moderate GDP impact; highest effect in rural energy-intensive sectors | +70,000 jobs by 2035 (mostly in grid storage projects) | Batteries, Hydrogen Storage, Pumped Hydro |

| Parameter | Example Value (EU) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Energy cost reduction ΔC | 10% | European Commission |

| Fossil fuel import reduction ΔF | 15% | EU Energy Outlook |

| EU GDP in 2025 GDP_base | USD 19 trillion | Eurostat |

| Fossil fuel imports F_imp | USD 500 billion | Eurostat, EC |

| Investment in ECSS IECSSI | USD 2 trillion (2025–2050) | BloombergNEF, EC |

| Energy multiplier M | 1.5 | OECD, literature |

| Import substitution multiplier S | 1.8 | OECD, literature |

| Employment multiplier Jm | 20,000 jobs per USD 1 billion | IRENA, EC |

| EU GDP per capita GDPpc | USD 46,000 | Eurostat |

| Average labor productivity E | USD 130,000 per worker | OECD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yakymchuk, A.; Baran-Zgłobicka, B.; Woruba, R.M. Advanced Energy Collection and Storage Systems: Socio-Economic Benefits and Environmental Effects in the Context of Energy System Transformation. Energies 2026, 19, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020309

Yakymchuk A, Baran-Zgłobicka B, Woruba RM. Advanced Energy Collection and Storage Systems: Socio-Economic Benefits and Environmental Effects in the Context of Energy System Transformation. Energies. 2026; 19(2):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020309

Chicago/Turabian StyleYakymchuk, Alina, Bogusława Baran-Zgłobicka, and Russell Matia Woruba. 2026. "Advanced Energy Collection and Storage Systems: Socio-Economic Benefits and Environmental Effects in the Context of Energy System Transformation" Energies 19, no. 2: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020309

APA StyleYakymchuk, A., Baran-Zgłobicka, B., & Woruba, R. M. (2026). Advanced Energy Collection and Storage Systems: Socio-Economic Benefits and Environmental Effects in the Context of Energy System Transformation. Energies, 19(2), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020309