Abstract

Machine learning (ML) is becoming a key enabler in building energy management systems (BEMS), yet most existing reviews focus on simulations and fail to reflect the realities of real-world deployment. In response to this limitation, the present work aims to present a systematic review dedicated entirely to experimental, field-tested applications of ML in BEMS, covering systems such as Heating, Ventilation & Air-conditioning (HVAC), Renewable Energy Systems (RES), Energy Storage Systems (ESS), Ground Heat Pumps (GHP), Domestic Hot Water (DHW), Electric Vehicle Charging (EVCS), and Lighting Systems (LS). A total of 73 real-world deployments are analyzed, featuring techniques like Model Predictive Control (MPC), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Reinforcement Learning (RL), Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC), metaheuristics, and hybrid approaches. In order to cover both methodological and practical aspects, and properly identify trends and potential challenges in the field, current review uses a unified framework: On the methodological side, it examines key-attributes such as algorithm design, agent architectures, data requirements, baselines, and performance metrics. From a practical standpoint, the study focuses on building typologies, deployment architectures, zones scalability, climate, location, and experimental duration. In this context, the current effort offers a holistic overview of the scientific landscape, outlining key trends and challenges in real-world machine learning applications for BEMS research. By focusing exclusively on real-world implementations, this study offers an evidence-based understanding of the strengths, limitations, and future potential of ML in building energy control—providing actionable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers working toward smarter, grid-responsive buildings. Findings reveal a maturing field with clear trends: MPC remains the most deployment-ready, ANNs provide efficient forecasting capabilities, RL is gaining traction through safer offline–online learning strategies, FLC offers simplicity and interpretability, and hybrid methods show strong performance in multi-energy setups.

1. Introduction

1.1. General

Energy systems embedded within buildings form a central component of modern infrastructure, playing a decisive role in balancing occupant comfort with operational efficiency [1]. Subsystems such as HVACs, RES, ESS, DHW, and LS are highly energy-intensive, and their effective coordination is essential for achieving sustainability goals [2,3,4]. Given that buildings account for more than one-third of global final energy consumption and a substantial portion of CO2 emissions, optimizing these systems is not merely a technical challenge but a broader societal imperative [5,6]. In this context, building energy systems are increasingly viewed as dynamic and complex environments in which advanced control strategies may substantially reduce energy consumption, improve comfort, and support the integration of renewable energy resources [7,8,9].

Addressing these challenges requires autonomous and robust control mechanisms capable of operating with minimal human intervention [10,11,12]. Traditional approaches such as manual scheduling or operator-based tuning, although common in early deployments, quickly proved inadequate for dealing with fluctuations in occupancy behavior, rapidly changing weather conditions, and dynamic energy prices [13,14]. The transition toward autonomous control was driven both by technological advances in sensing and computation and by policy initiatives aimed at reducing carbon emissions in the building sector [15,16,17,18].

The first automated control strategies adopted in buildings were relatively simple, utilizing a predefined set of “if-then” rules to control a building’s energy consumption and generation [13,19,20]: Fixed-time schedules and rule-based control (RBC) were widely used, with HVAC systems typically operating during preset hours or responding to fixed temperature thresholds defined by simple if-then logic [21,22]. Such approaches were transparent, easy to implement, and required little computational effort. For many years, they formed the backbone of automation in both commercial and residential buildings, providing a standardized way to maintain acceptable comfort conditions [23,24].

However, the limitations of fixed-time schedules and RBC soon became apparent. Their lack of flexibility made them unsuitable for environments characterized by uncertainty and variability. RBC strategies could not respond effectively to unexpected occupancy changes, rapid weather fluctuations, or variable electricity tariffs [21,24]. This often resulted in unnecessary energy use, reduced occupant satisfaction, and limited effectiveness when integrating renewable energy sources [25]. Such shortcomings highlighted the need for control strategies capable of adapting intelligently to complex and uncertain operating conditions.

This need catalyzed the gradual introduction of more advanced control methods into real-world building applications. Model Predictive Control (MPC) emerged as one of the earliest and most influential techniques, offering an optimization-based framework that explicitly incorporates system dynamics and operational constraints [26,27,28]. By using mathematical models of building behavior, MPC enabled predictive scheduling and cost-aware decision-making. Yet, its reliance on accurate, high-fidelity models also exposed a key limitation: developing such models is time-consuming, requires expert knowledge, and does not scale easily across different building types [29,30]. This led researchers and practitioners to explore alternatives that reduce the modeling burden while preserving the ability to handle nonlinear building dynamics.

Consequently, data-driven and soft computing approaches—such as Artificial Neural Networks [31,32], Fuzzy Logic Controllers [33,34], and Evolutionary Algorithms [35,36,37]—began to gain traction. Such practices offer greater flexibility by learning patterns directly from operational data or incorporating expert knowledge into rule-based or bio-inspired algorithms. Their main advantage was the ability to model complex behaviors without relying on detailed physics-based representations, making them particularly attractive in settings characterized by uncertainty and variability [24].

With the growing availability of building instrumentation and sensor data, a new generation of learning-based control strategies emerged. Reinforcement Learning became particularly prominent due to its ability to learn control policies through interaction with the environment, eliminating the need for explicit system identification [9]. At the same time, broader machine learning techniques—including Deep Learning [38,39,40], Random Forests [41,42], Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) [43,44], and hybrid physics-informed ML models [45]—were increasingly adopted. These techniques leverage large volumes of operational and contextual data to create scalable and adaptive controllers capable of responding autonomously to changing occupancy, weather conditions, and market dynamics. Through this evolution—from model driven optimization to soft computing and ultimately to fully data-driven or hybrid learning frameworks—building control systems have advanced from basic automation toward methods capable of continuous adaptation [29,46]. This trajectory reflects both the difficulty of developing accurate building models and the broader scientific effort to achieve more autonomous, scalable, and resilient energy management systems.

Although the evolution of intelligent building control has been thoroughly examined in the literature, much of this work remains confined to simulated environments [4,9,24,29]. Researchers often rely on detailed simulators, testbeds, or digital twins to evaluate MPC, ANN-based controllers, RL agents, and other advanced techniques. While simulation-based studies are valuable for controlled experimentation and rapid prototyping, real-world deployment poses additional challenges. Issues such as sensor noise, actuator delays, communication constraints, cybersecurity considerations, and occupant acceptance are difficult to replicate in simulation [47,48]. Consequently, the gap between promising laboratory results and widespread real-world adoption remains substantial, emphasizing the need for more studies conducted in operational buildings (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of real-world experiments for BEMS.

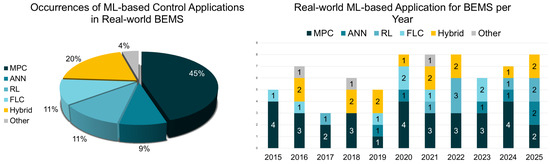

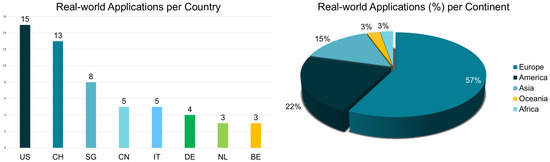

The current review therefore focuses explicitly on real-world applications of machine learning for controlling BEMS. By synthesizing studies that extend beyond simulation and into field demonstrations with live operational settings on building energy systems—e.g., HVACs, RES, ESS, TSS, DHW, etc.—or their integrated ecosystems, it aims to provide a comprehensive overview of current practices, identify the technical and practical trends encountered in deployment, and extract insights to guide future research. The ultimate goal is to explore the different key-aspects of machine learning applications (e.g., MPC, ANN, RL, FLC, hybrids etc.) that took place in real-world buildings (See Figure 2-Left and Right), offering a valuable reference for researchers and practitioners working toward the deployment of intelligent building control solutions.

Figure 2.

Left: Occurrences of ML-based control applications in real-world BEMS; Right: Real-world ML-based applications for BEMS per year.

1.2. Previous Works

To help situate our work in the broader research landscape, the current subsection provides a brief summary of key existing review studies: Vásquez et al. [49] examined post-occupancy evaluation (POE) as a structured method for assessing buildings under real operating conditions. By linking technical, environmental, and social aspects, their review showed how occupant feedback and performance monitoring can reveal inefficiencies and guide design and operational improvements. They also noted persistent challenges, including implementation costs, unclear responsibilities, and the absence of standardized POE procedures. Abuimara et al. [50] proposed a data-driven workflow to enhance energy-efficient building operations. Their framework integrates four domains—metadata quality, automated fault detection, occupant-centric controls, and energy flow monitoring—into a single, interdependent sequence. Demonstrated through case studies in Canadian institutional buildings, the approach offers a practical, low-cost, and tool-agnostic roadmap for improving building performance. Khoa et al. [51] provided a comprehensive review of machine learning applications for HVAC optimization, control, and fault detection. They surveyed a wide range of algorithms including neural networks, support vector machines, and Reinforcement Learning, highlighting their potential to reduce energy use. At the same time, they identified key barriers such as limited data availability, poor model transferability across buildings, and slow industry adoption, underscoring the gap between research capabilities and practical deployment. More recently, Aghili et al. [52] delivered a systematic review of artificial intelligence techniques for HVAC energy management, covering both operational control and maintenance. Their work emphasized how advanced AI methods—such as deep Reinforcement Learning and generative models—can dynamically accommodate changing occupancy patterns and environmental conditions. Distinct from earlier surveys, the authors stressed the importance of bridging theoretical progress with real-world implementation, positioning AI as a central technology for enabling smart and low-carbon buildings. Previous review papers in the field have contributed valuable overviews but are largely constrained by their focus on simulation-based studies or narrow system scopes—particularly HVAC control. Most lack detailed coverage of real-world implementations, making it difficult to assess how machine learning performs under actual operational constraints. Additionally, prior surveys often overlook important subsystems such as Renewable Energy Systems, Energy Storage Systems, Domestic Hot Water, or Electric Vehicle Charging, and rarely offer statistical synthesis across methodological and deployment factors.

1.3. Contribution and Novelty

In contrast to existing reviews, this work is focusing exclusively on real-world field implementations of ML in BEMS. Seventy three studies are systematically selected, each representing an ML-based approach validated under real operational conditions in actual building testbeds. This emphasis on real deployment is aimed to create a stronger evidence base that has been largely missing in literature. To this end, current work follows a systematic methodology designed to include high impact experimental studies from the past decade. Moreover, unlike the majority of reviews, which concentrates mainly on HVAC systems, the present study encompasses the full spectrum of building energy subsystems: HVAC, Heat Pumps, Renewable Energy Systems, Energy Storage, lighting, and Domestic Hot Water—thereby offering a broader understanding of ML-enabled energy management.

Beyond compiling field studies, current work provides systematic insights into trends, performance, and methodological patterns across the collected real-world implementations. Statistical analysis of the dataset is used to identify recurring behaviors and compare the effectiveness of different techniques under real operating constraints. To the authors’ knowledge, current work represents the first comprehensive/systematic review to consolidate the majority of real-world ML applications for BEMS in a single work. As such, it aims to serve both as a practical reference for practitioners and as a research-oriented guide that highlights key challenges, emerging trends, and promising directions for future investigations. More specifically, the novelty attributes of the current work may be summarized as follows: (a) Focuses exclusively on real-world ML-based BEMS deployments, representing the first systematic consolidation of real-world ML–BEMS work; (b) Examines a high number of applications—a total of 73 high-impact, real-life experimentally validated research studies; (c) Covers all major building energy subsystems, such as HVAC, HP, RES, ESS, TSS, DHW, EVCS and Light systems (LS); (d) Provides cross-study patterns in methodological (as algorithms, agent-based architectures, reward designs, datasets, baseline control approaches, performance indexes) and practical (as IoT implementation types, building typologies, zones number, location and climate) design choices; and (e) Uses statistical analysis to reveal trends across real implementations and foster the future directions in the field of real-life machine learning applications for building energy management.

1.4. Paper Structure

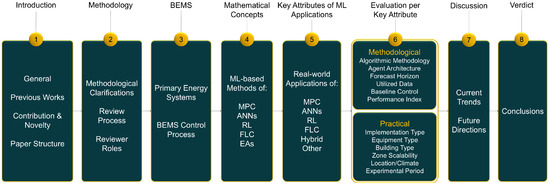

The structure of this paper may be described as follows (see Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Paper structure.

- Section 1: Introduces the background and rationale for the study, briefly reviews existing surveys in the field, and clarifies how the present work differs in scope and novelty.

- Section 2: Explains the research methodology, including literature search strategy, selection and screening process, data extraction, quality control, and synthesis procedure.

- Section 3: Describes the main categories of Building Energy Systems (BES) and discusses the integration of ML approaches, along with typical barriers encountered in real implementations.

- Section 4: Outlines the mathematical underpinnings of ML techniques and introduces the principal algorithm families (MPC, RL, evolutionary strategies, etc.), with particular attention to multi-agent frameworks.

- Section 5: Compiles the integrated influential real-world studies from 2015 to 2025 in a structured table, capturing the key-attributes of the integrated works.

- Section 6: Analyzes the reviewed studies across methodological and practical aspects. Methodological key-attributes concern dimensions as the algorithm design, agent structure, data types baselines control, performance indexes, while practical key-attributes concern implementation features, building type, zone scalability, location, climate and experimental period execution.

- Section 7: Discusses and summarizes the emerging trends and knowledge gaps, contrasts them with prior reviews, and proposes future research directions to advance ML applications in BEMS.

- Section 8: Closes the paper by highlighting the main contributions and overarching insights derived from the review.

- Appendix A: Concise summaries of each selected work are being illustrated in tables, following the numbering of the key attribute tables illustrated in Section 5.

2. Methodology

2.1. Methodological Clarifications

To ensure transparency and make the review easy to follow and reproduce, this study follows the PRISMA guidelines and includes several clarifications on how the methodology was carried out. The literature search focused on peer-reviewed studies published between January 2015 and March 2025, with the final database query completed in March 2025. Only papers written in English were included, and eligible sources were limited to journal articles and full conference papers. Materials like theses, dissertations, technical reports, workshop proceedings, or non-peer-reviewed documents were excluded. For a study to be included, it had to report on a ML-based control or optimization method that was tested in a real building—such as a field pilot, a living lab, or a long-term experimental setup. Simulation-only studies were not considered unless they included direct comparisons with real-world measurements. During the review process, data from each selected study were extracted using a structured template. Methodological information comprised the following: algorithm used, agent architecture, forecast horizon and control timestep, utilized data, baseline control methodology, and performance metrics. Practical information comprised the following: the experimental setup, the type of energy system involved, the building typology, the building zone scalability, the location, climate and the experimental time. The extracted data were carefully checked for consistency and accuracy.

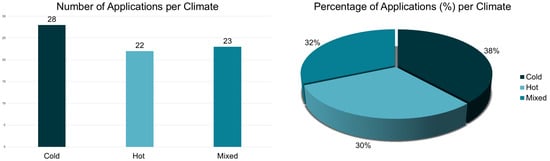

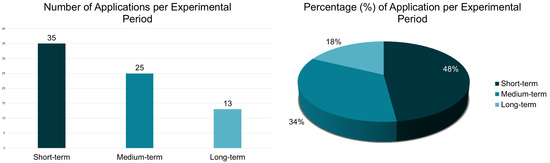

Since the reviewed studies varied widely in terms of building types, control goals, time horizons, and evaluation metrics, a formal meta-analysis was not possible. Instead, a descriptive quantitative synthesis was used, reporting on trends, frequencies, and comparisons across different methods—an approach that aligns well with PRISMA guidance for complex engineering reviews. Moreover, all the quantitative trends, percentages, and distributions shown in the figures and discussed throughout the paper were directly drawn from the curated set of 73 real-world studies included in the current review. Unless otherwise noted, percentages—such as the share of each algorithm type, deployment frequency, or regional distribution—were calculated as simple relative frequencies based on the total number of included studies. Geographic patterns were identified by counting the number of deployments per country or region, using the entries listed in the “Location” column of the attribute tables. Current work did not apply any data imputation or weighting. Current summary tables in the Appendix are fully available and make it possible for others to independently verify and reproduce the quantitative insights and visualizations presented. More specifically, the work has followed a systematic process described by the following steps:

2.2. Review Process

- Article Search and Retrieval: A systematic search was carried out using major academic databases such as Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). Search queries combined broad ML terminology with keywords related to building energy systems, for example:

The initial query returned over 400 publications. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, duplicates were removed, and only studies reporting real-world ML applications within building energy systems were retained for further evaluation.("Machine Learning" OR "Artificial Intelligence" OR "Reinforcement Learning" OR "Deep Learning") AND (Building OR HVAC OR "Building Energy Management" OR BEMS OR "Heat Pump" OR "thermal storage" OR RES OR "Domestic Hot Water" OR DHW OR Lighting OR "Energy Storage" OR ESS OR "Electric Vehicle Charging" OR EVCS) - Filtering and Selection Criteria: A second filtering stage ensured that only high-quality and practically relevant studies were included. More specifically, only studies that had accumulated at least 10 citations at the time of review were considered, ensuring a minimum level of academic recognition and peer validation. For very recent publications (2025), which have not yet had sufficient time to accrue citations, this criterion was relaxed, provided that the studies reported clear real-world experimental validation and were published in reputable peer-reviewed venues. Peer-reviewed journal articles and leading conference contributions were considered. Each selected work had to demonstrate a tangible real-world implementation, such as deployment in operational buildings, field pilots, or extensive experimental validation. Simulation-only studies were excluded unless the authors incorporated direct benchmarking with field measurements. The final dataset comprises real-life applications.

- Data Collection: For each selected publication, detailed information was extracted regarding the ML methodology (e.g., MPC, FLC, RL, ANNs, evolutionary approaches, hybrid models), targeted subsystem, control or optimization objective, baseline comparisons, and performance metrics (including energy savings, comfort indicators, and cost reductions). Information on the validation setup—building type, scale, and zone configuration—was also captured. Particular attention was paid to studies that benchmarked ML controllers against standard or rule-based control strategies.

- Quality Assessment: All works were evaluated for methodological rigor, clarity in describing the ML workflow, and completeness of the reported results. Priority was given to studies published in reputable outlets (Elsevier, IEEE, MDPI, Springer, etc.) and authored by established researchers in energy systems and control. Preference was also given to contributions presenting full workflows, from model development and controller design to validation and performance evaluation.

- Data Synthesis: The selected studies were grouped according to subsystem type, ML technique, control architecture, and scale of real-world validation. This categorization facilitated cross-comparison across methods and supported the generation of statistical charts illustrating trends in algorithm selection, performance outcomes, and building typologies. Through this synthesis, the review identifies promising approaches, recurring limitations, and emerging directions for applying ML in real operational BEMS environments.

2.3. Reviewer Roles and Dispute Resolution

The systematic review process was conducted by multiple authors with complementary expertise in building energy management systems, machine learning, and control engineering. The search strategy, study screening, and eligibility assessment were primarily conducted by P.M. and I.M., following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data extraction and investigation were performed by P.M., F.M., M.K., and H.H.C. using a structured extraction template, while validation and formal analysis were carried out collaboratively by all authors to ensure consistency and accuracy.

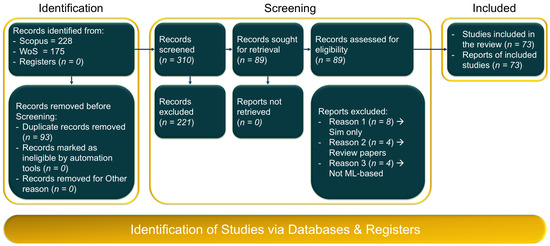

In cases of disagreement regarding study inclusion, data interpretation, or methodological classification, differences were resolved through structured discussion among the involved reviewers. When consensus was not immediately achieved, final decisions were made under the supervision of senior authors (P.M. and E.K.). This consensus-based procedure ensured methodological rigor, minimized individual bias, and enhanced the reproducibility of the review process. The comprehensive methodology of the current review is illustrated in a PRISMA type diagram in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Methodology in a PRISMA type diagram.

3. Building Energy Management Systems

3.1. Primary Energy Systems

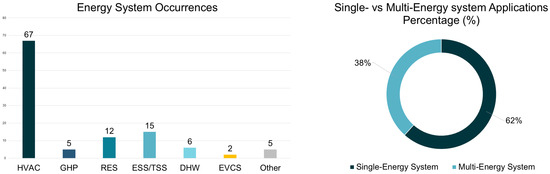

Modern buildings consist of multiple Energy Systems—such subsystems account for most of a building’s energy use and strongly influence both operating costs and occupant comfort [53]. The most common equipment found in the building level may concern [24] (See also Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Reasons for controlling energy systems in the building environment.

- HVAC: HVACs may consist of heat pumps, boilers, chillers, fans, pumps, and distribution networks that regulate indoor temperature and air quality [54]. Its purpose in the building environment is to maintain comfort and healthy indoor environments, requiring control to adapt operation to weather and occupancy while minimizing energy use [55].

- DHW: Domestic Hot Water systems include heaters, storage tanks, heat exchangers, and circulation loops that deliver hot water for hygiene and daily needs [56,57]. DHW operation ensures reliable and efficient hot-water availability, requiring control to schedule heating, avoid thermal losses, and match operation to demand [56].

- RES: Renewable Energy Systems may comprise PV panels, inverters, solar thermal collectors, wind turbines, and related sensors that generate on-site renewable electricity or heat [9,58,59]. Their utilization in the building environment is aimed to harvest energy, maximize renewable use and reduce grid dependency. Such systems require control to manage variability and coordinate with loads and energy storage [60].

- ESS: Energy Storage Systems include batteries with BMS/inverters [61]. Such equipment is adequate to shift loads and increase flexibility, requiring control of charge/discharge timing to optimize cost, protect system health, and support renewable integration [60,62].

- EVCS: Electric Vehicle Charging Systems consist of AC/DC chargers, smart controllers, and sometimes V2G/V2B interfaces supplying energy to EVs [63,64]. The implementation of such systems in the building environment concerns the provision of charging without causing peaks or strain [65]. Such systems require control to schedule charging, use low-tariff periods, and leverage EV flexibility [66,67,68].

- GHP: Ground-source Heat Pumps extract or reject heat through underground loops connected to the stable-temperature ground, offering highly efficient year-round heating and cooling [69,70]. Such systems are utilized in order to leverage the ground’s thermal inertia for superior efficiency, requiring control to regulate flow rates, switching modes, and loop balancing to maximize savings and protect the ground loop from thermal drift [71].

- LS and Appliances: Lighting Systems and Appliances may include LED fixtures, lamps or home devices, office equipment, computer, servers, that consume electricity during operation or standby [72]. Such equipment is commonly utilized to enable comfort and reduce unnecessary consumption. It requires control through smart switching, dimming, and scheduling aligned with occupancy [73].

In real buildings, such energy systems do not operate in isolation—they continuously cooperate within the same environment to satisfy occupant needs and achieve overall performance targets [74]. Together, they form an integrated building energy management system (IBEMS) where each subsystem influences the others: shading or plug loads affect HVAC demand, PV output affects battery and EV charging decisions, and thermal storage influences heating and cooling loads. This interdependence means that delivering comfort, reliability, and efficiency in real-life potentially requires coordinated control rather than subsystem-level decisions [75].

3.2. BEMS Control Process

Modern BEMS operate through a structured, intelligent control loop that continuously transforms sensor data into optimized actions for energy efficiency and occupant comfort. This process involves sensing, prediction, decision-making, and execution—working together to create a responsive and adaptive environment [29,76].

At the heart of this system is a step-by-step control cycle that enables predictive and coordinated management of key building subsystems, such as HVAC, RES, ESS, GHP, EVCS, etc. Each component plays a role in helping the building operate more efficiently, flexibly, and sustainably. The complete step-by-step control workflow is outlined as follows (see also Figure 6):

Figure 6.

Step-by-step control cycle of a modern building energy management system.

- Sensing: The process starts with capturing building and environmental real-time data from sensors that monitor temperature, humidity, CO2, occupancy, solar radiation, energy usage, and other key indicators. This provides a snapshot of the current state of the building.

- Preprocessing: Raw data is cleaned, synchronized, and formatted to ensure it can be reliably used. Communication protocols such as BACnet/IP, Modbus, OPC-UA, or MQTT help ensure that data flows safely and accurately to the system.

- Forecasting: Using machine learning or statistical models, the system predicts short-term future conditions such as energy demand, occupancy changes, or solar generation. These forecasts allow the system to plan ahead rather than simply react.

- Optimization: Based on the forecasts and system constraints (e.g., comfort requirements, energy prices, equipment limits), optimization algorithms compute the best control actions. These might include HVAC setpoints, charge/discharge schedules for batteries, or EV charging rates.

- Actuation: The control decisions are sent to physical devices through the building management system, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), or IoT platforms. This is the point where decisions become real-world actions.

- Operation: Devices adjust according to the new settings. HVAC systems may change airflow or temperature, batteries may charge or discharge, and EV chargers may ramp up or down.

- Condition Alteration: As the control actions are applied, the building’s internal conditions—temperature, humidity, energy use—change. These new states are what the system will monitor in the next control cycle.

- Feedback: The system collects new sensor data and compares it to expected outcomes. This feedback allows it to adjust, learn, and improve performance over time, while also detecting anomalies or triggering safety rules if needed.

Thanks to this continuous loop, BEMS can dynamically adjust system settings—like HVAC temperature or battery charging—based on current conditions, user presence, and even external factors like energy tariffs. This ensures buildings run efficiently while maintaining comfort and responsiveness to occupant needs and grid conditions.

4. Mathematical Concepts of ML-Based Methodologies

The development of advanced control strategies for building energy management systems (BEMS) has been shaped by different methodological philosophies, each reflecting a distinct view of how buildings interact with their environment and how energy performance can be improved. Model Predictive Control is rooted in optimization and predictive modeling [77,78]; Fuzzy Logic Control draws on human reasoning and linguistic rules [79]; ANNs and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) rely on data-driven pattern recognition [80,81]; EAs mimic natural selection [82,83]; and RL focuses on adaptation through trial-and-error interaction [9,84,85]. The following subsections describe the conceptual motivation, mathematical principles, and practical strengths and weaknesses of each approach, particularly in the context of real-world BEMS applications.

4.1. Model Predictive Control

MPC is built on the idea of prediction and optimization. Assuming that building dynamics can be described with sufficient accuracy, MPC forecasts future system trajectories and computes optimal control actions by repeatedly solving a constrained optimization problem [29]. The general formulation minimizes a cost function over a prediction horizon:

subject to model dynamics and operational constraints. MPC’s main advantages include explicit constraint handling, support for multi-objective formulation, and the ability to coordinate multiple interacting subsystems [29,78]. Its limitations stem from the need for accurate models, high computational demand, and sensitivity to disturbances not captured in the model [86]. In practice, these challenges complicate model calibration, scalability in multi-zone buildings, and ensuring sufficiently fast computations for real-time control [29].

4.2. Artificial Neural Networks

ANNs are based on the idea of learning nonlinear relationships directly from data. By stacking layers of interconnected neurons, they approximate complex functions without requiring explicit physical models [87]. DNNs extend this capability through multiple hidden layers that enable hierarchical feature extraction. Mathematically, an ANN is expressed as [88]:

with and denoting weights and biases, and activation functions. ANNs are powerful universal approximators capable of capturing nonlinear building behavior using sensor data. Their drawbacks include the need for large, representative datasets, risks of overfitting, and limited interpretability [4]. For BEMS, this means that models may struggle with unusual conditions, incomplete datasets, or operator concerns regarding the transparency of black-box decision-making [4,31].

4.3. Reinforcement Learning

RL is based on adaptation through ongoing interaction with the environment. An agent learns a control policy by exploring actions and receiving rewards, aiming to maximize long-term performance [9]. Formally, RL optimizes the expected return [89]:

where denotes the policy mapping states to actions. RL’s strengths include independence from explicit models, the ability to learn adaptive strategies in dynamic environments, and direct optimization of long-term objectives [9,90]. Its weaknesses involve high data requirements, potential instability during training, and safety concerns during exploration. In BEMS, these limitations pose challenges for direct deployment in occupied buildings, where unsafe actions may compromise comfort or equipment, and where policies trained in simulation often fail to transfer seamlessly to real-world environments [9].

4.4. Fuzzy Logic Control

FLC is grounded in approximate reasoning and relies on human expertise when precise models are unavailable. Inputs are translated into fuzzy sets (e.g., “high temperature”), and inference rules are combined to compute control actions [91]. A standard fuzzy control law is:

where are membership functions and rule outputs. FLC excels in interpretability, robustness to noise, and independence from explicit modeling [92,93]. However, rule bases can become complex and difficult to maintain, and classical FLC lacks automatic adaptation mechanisms. In BEMS, this limits scalability to large multi-zone environments and can reduce performance when operating conditions evolve and rules are no longer well aligned with real dynamics [24].

4.5. Evolutionary Algorithms

EAs draw inspiration from biological evolution, using populations of candidate solutions that evolve through selection, crossover, and mutation. They do not rely on differentiability or convexity, making them effective for complex, multi-objective problems. In the case of GAs, evolutionary updates follow [94]:

with parents and chosen based on fitness. EAs offer robustness, flexibility, and reliable performance in noisy, multimodal optimization settings [94]. However, they often converge slowly, require significant computation, and can yield variable solutions across runs [95]. In BEMS, these characteristics limit their suitability for real-time operation and necessitate careful parameter tuning to ensure consistency and operational robustness [24,95].

5. Key Attributes of ML-Based Real-World Applications

This section illustrates the high impact ML-based applications in BEMS from 2015 to 2025, by offering a high-level overview of MPC, ANN, RL, FLC, hybrid, and other high-impact real-world applications found in the literature. Such an approach allows readers to quickly identify relevant applications in the attribute tables and refer to the detailed summaries for deeper insights into their methodologies and findings. The general description of the tables is as follows:

Key-Attribute Tables: (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) systematically illustrate each application according to key characteristics, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the overall approach:

Table 1.

Key attributes of MPC applications for real-life BEMS.

Table 2.

Key attributes of ANN applications for real-life BEMS.

Table 3.

Key attributes of RL applications for real-life BEMS.

Table 4.

Key attributes of FLC applications for real-life BEMS.

Table 5.

Key attributes of hybrid applications for real-life BEMS.

Table 6.

Key attributes of other type applications for real-life BEMS.

- Ref.: Provides the reference application is listed in the first column;

- Year: Provides the publication year for each research application;

- Type: Contains the specific algorithmic type of each MPC, ANN, RL, FLC, hybrid, and other ML-based methodologies, applied in each application. In MPC applications the solver is contained in parentheses: SLP (Sequential Linear Programming), NLP (Nonlinear Programming), QP (Quadratic Programming), MILP (Mixed-Integer Linear Programming), MIQP (Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming), SQP (Sequential Quadratic Programming), DP (Dynamic Programming). In ANNs applications the cases concern: MLP (Multilayer Perceptron), LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory Network), NARX (Nonlinear Autoregressive Network with Exogenous Inputs), CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) algorithms. In RL applications the cases concern: FQI (Fitted Q-Iteration), BDQ (Batch Deep Q-Learning), DQN (Deep Q-Network), PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) and SAC (Soft Actor–Critic) algorithms;

- Agent: Contains the agent type of the concerned methodology (“Single” for single-agent or “Multi” for multi-agent ML-based approach);

- FH/TS: Illustrates the Forecast Horizon (FH) and the Timestep (TS) intervals for the ML-based control application, considering the BEMS;

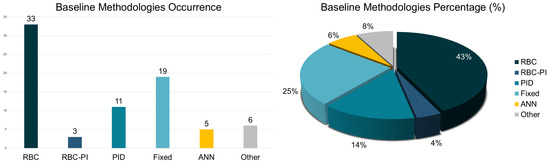

- Baseline: Illustrates the comparison methods used to evaluate the proposed ML-based approach (such as RBC, Fixed, or other ML-based strategies);

- Equipment: Indicates the energy systems integrated in the BEMS framework (e.g., HVAC, RES, ESS, TSS, GHP, EVCS, LS, Appliances etc.);

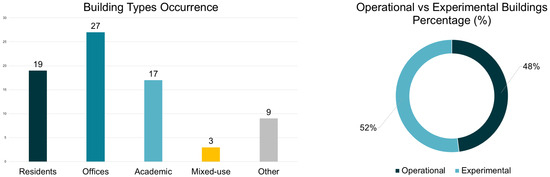

- Building: Describes the typology of the concerned real-world building (e.g., Residential, Office, Academic, Lab, etc.);

- Zones: Illustrates the number of the controlled zones for each real-world building testbed;

- Location: Illustrates the location of each real-world application. The country code is included in parentheses for each experiment;

- Period: Illustrates the period when experimental control implementation took place (Summer, Autumn, Winter, Spring). The exact time intervals of experiment execution is given in parenthesis concerning Days (D), Weeks (W), Months (M) and Years (Y);

It should be underlined that the summaries of the real-world applications that concern the current paper have been moved to the Appendix A along with the Figures that concerns the structures of the experimental building testbeds. The interested reader may identify the summaries for MPC, ANN, RL, FLC, hybrid and other ML applications in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5, respectively. Each of these tables are aligned with key-attribute Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 that this section illustrates in detail.

Table 7 provides a compact synthesis of dominant characteristics observed across all real-world ML-based BEMS implementations from 2015 to 2025. By aggregating common patterns in algorithmic types, agent structures, horizons, baselines, building contexts, and deployment durations.

Table 7.

Cross-method summarization of dominant attributes in real-world ML-based BEMS (2015–2025).

6. Evaluation

Current review work analyzes the different trends in methodological and practical aspects in depth in a effort to holistically cover the field of ML-based control in real-world buildings. To this end, Section 6 analyzes the field in-depth across the following aspects:

Section 6.1 Methodological Key-Attributes describes how the ML-based control systems were designed and evaluated in real-world settings. More specifically, each paragraph analyzes:

- Algorithmic Methodology: In Section 6.1.1

- Agent Architecture: In Section 6.1.2

- Forecast Horizon and Timestep: In Section 6.1.3

- Data Utilization: In Section 6.1.4

- Baseline Control: In Section 6.1.5

- Performance Metrics: In Section 6.1.6

Section 6.2 Practical Key-Attributes reflects on how these ML-based approaches were implemented and operated in real building environments. More specifically, each paragraph analyzes:

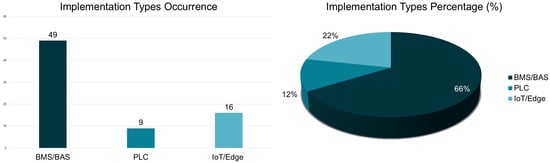

- Implementation Types: In Section 6.2.1

- Equipment Types: In Section 6.2.2

- Building Types: In Section 6.2.3

- Zone Scalability: In Section 6.2.4

- Location and Climate: In Section 6.2.5

- Experimental Period: In Section 6.2.6

6.1. Methodological Key-Attributes

The methodological attributes (Section 6.1.1, Section 6.1.2, Section 6.1.3, Section 6.1.4, Section 6.1.5 and Section 6.1.6) focus on the internal logic and design of each control system, including the algorithmic approach (e.g., MPC, RL, ANN), agent architecture (single-agent vs. multi-agent), forecasting horizon and timestep, data utilization methods, baseline control strategies, and performance evaluation metrics. Such elements provide a structured lens through which to assess how ML techniques are applied, compared, and validated in real building environments.

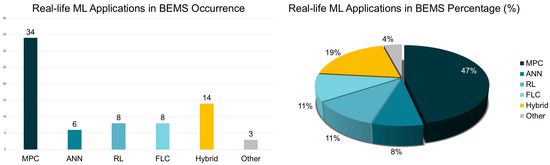

6.1.1. Evaluation per Algorithmic Methodology

Among the reviewed real-world experimental studies, MPC in its classical form appears most frequently in academic field deployments (see Figure 7-Left and Right, and also Table 7) [96,111,117]; however, this reflects publication trends rather than a general claim about dominance or maturity across all building types or industry practice. As it is evident, economic and distributed MPC further extend MPC utilization to tariff-driven and multi-zone applications [110,119]. ANNs, on the other hand, seem to be well-suited for forecasting indoor temperature, CO2, HVAC loads, or for functioning as surrogate models, enabling predictive and personalized control [130,131,134]. Their compatibility with embedded systems and BMS infrastructures foster such suitability for real-time prediction tasks [132]. By contrast, RL becomes suitable when building dynamics are nonlinear, uncertain, or hard to model. Field studies show RL is adequate to adapt to stochastic occupancy and volatile conditions when combined with offline training and safety layers [137,138,142]. However, although RL proved highly adaptive, its real-world experimentation remained small-scale due to stability and data requirements [141] (see Figure 7-Left and Right, and also Table 7).

Figure 7.

Left: Occurrence of ML types in in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Percentage (%) of ML types in in real-world BEMS applications.

FLC approaches excelled in environments with uncertainty, sparse sensing, or strong human-in-the-loop requirements. Their interpretability and robustness rendered them suitable for comfort and IAQ control as shown across multiple real experiments [144,145,150]. Metaheuristics—such as GA and PSO—proved suitable for non-convex or multi-energy scheduling tasks, particularly when forecasting modules feed into higher-level optimization [152,162]. Their limitation, however, concerning the slow runtime, restricted them mostly to supervisory, day-ahead, or design-level tasks—as such implementations were primarily concerned hybrid algorithmic approaches. Moreover, in several deployments, hybrid architectures demonstrated the ability to combine forecasting, optimization, and constraint-handling within a single framework [135,158,163]; however, it needs to be mentioned that their performance advantages were context-dependent and not uniformly superior to pure MPC or pure RL approaches. More specifically:

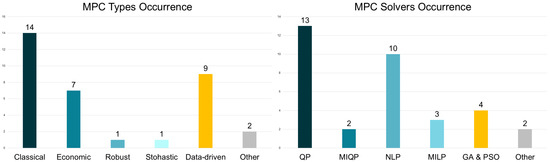

- Model Predictive Control: Across the experimental real-world deployments reviewed, MPC was predominantly implemented using classical, physics-based models, which are frequently reported to integrate cleanly with existing BMS/BAS infrastructures and to offer predictable performance [96,112,117] (See Figure 8-Left). Calibrated RC or state-space models—combined with convex cost functions and constraint sets—enable transparent operation and consistent real-time behavior [105,111,114]. In situations with high uncertainty, such as fluctuating occupancy, outdoor conditions, or grid-interaction scenarios, robust and stochastic MPC formulations were used [102,124]. Such embed uncertainty via chance constraints or conservative sets, reducing comfort violations with minimal increases in energy use [102,124]. When detailed physics-based modeling became costly or systems were highly complex, data-driven MPC was adopted. These retain an optimization-friendly structure while improving prediction accuracy through ML models (e.g., residual regressors, neural networks) [107,113,118]. Such hybrid formulations are reported to lower prediction errors without compromising real-time feasibility [112,121,122].

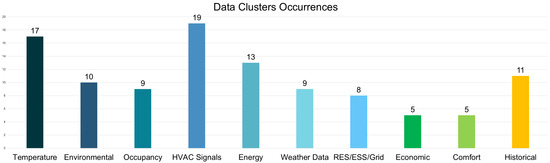

Figure 8. Left: Occurrence of MPC types in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Occurrence of MPC solvers in real-world BEMS applications.For buildings with dynamic tariffs or onsite RES generation, economic MPC (E-MPC) illustrated the dominant strategy [108,110]. By directly minimizing energy costs or maximizing PV self-consumption, E-MPC was frequently reported to deliver double-digit cost reductions and significant peak-load reductions compared with RBC or PI control [115,120,122]. Conversely, comfort-driven MPC remained common in academic testbeds and constant-tariff settings, where the primary objective is maintaining indoor comfort rather than reducing energy bills [111,114,125]. A smaller but notable share of real-life studies adopted distributed or hierarchical MPC [105,119]: Using ADMM or price-based coordination, such architectures efficiently managed multi-zone buildings or campus-scale systems by separating slower economic optimization from faster local comfort tracking—maintaining both tractability and autonomy.A consistent trend across real-life MPC studies was the preference for convex optimization. When comfort, actuator limits, and energy costs can be expressed linearly, MPC formulations rely on QP or MIQP solvers, ensuring reliable convergence and predictable computation [105,123,127] (See Figure 8-Right). Nonlinear solvers (NLP) were primarily used for PMV, humidity, or CO2 constraints, and even then researchers employ efficient algorithms (IPOPT, fmincon, sequential linearization) to maintain real-time feasibility [99,113,114,117]. Moreover, discrete actuators introduced additional complexity. Even when the main optimization was convex, discrete equipment modes (compressors, valves, fans) are managed using MIQP formulations or dedicated post-processing logic to avoid short-cycling [110,112,120,126]. When system nonlinearities remain strong, metaheuristics such as GA or PSO were occasionally integrated as observed in [104,115,129]—it should be mentioned though, that such methods needed to be carefully bounded, in order to preserve real-time operation. According to evidence, comfort modeling was increasingly sophisticated since numerous MPC approaches retained convexity by linearizing PMV or using temperature bands [96,111]—others implemented adaptive or occupant-centered models based on feedback or estimated thermal sensation [101,116]. Such personalized approaches proved adequate to reduce energy use while preserving (or even improving) perceived comfort [99,127].In summary, the reviewed practical deployments indicate that MPC implementations tend to perform most reliably when designed pragmatically: using calibrated grey-box models [112], lightweight estimation [114,126], convex or mixed-integer solvers [105,127], and horizons tailored to building dynamics [96,111]. Across the reviewed real-world studies, reliability, explainability, and real-time feasibility are more frequently emphasized than theoretical optimality [116,117,125]. Under these conditions, MPC is able to deliver measurable savings, improved comfort, and enhanced flexibility in operational buildings [105,106,112,118].

Figure 8. Left: Occurrence of MPC types in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Occurrence of MPC solvers in real-world BEMS applications.For buildings with dynamic tariffs or onsite RES generation, economic MPC (E-MPC) illustrated the dominant strategy [108,110]. By directly minimizing energy costs or maximizing PV self-consumption, E-MPC was frequently reported to deliver double-digit cost reductions and significant peak-load reductions compared with RBC or PI control [115,120,122]. Conversely, comfort-driven MPC remained common in academic testbeds and constant-tariff settings, where the primary objective is maintaining indoor comfort rather than reducing energy bills [111,114,125]. A smaller but notable share of real-life studies adopted distributed or hierarchical MPC [105,119]: Using ADMM or price-based coordination, such architectures efficiently managed multi-zone buildings or campus-scale systems by separating slower economic optimization from faster local comfort tracking—maintaining both tractability and autonomy.A consistent trend across real-life MPC studies was the preference for convex optimization. When comfort, actuator limits, and energy costs can be expressed linearly, MPC formulations rely on QP or MIQP solvers, ensuring reliable convergence and predictable computation [105,123,127] (See Figure 8-Right). Nonlinear solvers (NLP) were primarily used for PMV, humidity, or CO2 constraints, and even then researchers employ efficient algorithms (IPOPT, fmincon, sequential linearization) to maintain real-time feasibility [99,113,114,117]. Moreover, discrete actuators introduced additional complexity. Even when the main optimization was convex, discrete equipment modes (compressors, valves, fans) are managed using MIQP formulations or dedicated post-processing logic to avoid short-cycling [110,112,120,126]. When system nonlinearities remain strong, metaheuristics such as GA or PSO were occasionally integrated as observed in [104,115,129]—it should be mentioned though, that such methods needed to be carefully bounded, in order to preserve real-time operation. According to evidence, comfort modeling was increasingly sophisticated since numerous MPC approaches retained convexity by linearizing PMV or using temperature bands [96,111]—others implemented adaptive or occupant-centered models based on feedback or estimated thermal sensation [101,116]. Such personalized approaches proved adequate to reduce energy use while preserving (or even improving) perceived comfort [99,127].In summary, the reviewed practical deployments indicate that MPC implementations tend to perform most reliably when designed pragmatically: using calibrated grey-box models [112], lightweight estimation [114,126], convex or mixed-integer solvers [105,127], and horizons tailored to building dynamics [96,111]. Across the reviewed real-world studies, reliability, explainability, and real-time feasibility are more frequently emphasized than theoretical optimality [116,117,125]. Under these conditions, MPC is able to deliver measurable savings, improved comfort, and enhanced flexibility in operational buildings [105,106,112,118]. - Artificial Neural Networks: Real-world ANN implementations for building energy management seem to evolve far beyond simple feedforward predictors, increasingly adopting deep, temporal, and hybrid architectures. The dominant pattern follows supervised learning with offline training on building data, followed by online adaptation or seamless BEMS integration for real-time operation. Early demonstrations, such as [130], used a Bayesian-regularized MLP trained on occupant feedback to personalize HVAC setpoints in a commercial office. Updated daily and interfaced directly with PID controllers, this study showed that even lightweight and interpretable ANNs were able to deliver real-time personalization while remaining fully compatible with legacy control structures. A major share of real-world ANN deployments employed recurrent or otherwise time-aware architectures—NARX networks, LSTMs, or hybrid temporal models—to capture thermal inertia, occupancy-driven variability, and indoor air quality dynamics (See Figure 9-Left). In [131], an MLP–NARX integrated model, predicted indoor temperatures under varying occupancy with sub-degree accuracy across both short and long horizons. Similarly, ref. [134] embedded an LSTM within a BEMS to predict CO2 concentrations 5 min ahead and control an ERV system. Such recurrent ANN design captured temporal correlations more effectively than DNN and GRU baselines, demonstrating the advantages of temporal learning for proactive HVAC and ventilation management.

Figure 9. Left: Occurrence of ANN types in real-world BEMS applications; Center: Occurrence of RL types in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Occurrence of FLC types in real-world BEMS applications.A second emerging trend concerned embedded and edge-deployed ANN models for distributed control and monitoring. In [132,133], 1-D CNNs and LSTM predictors were implemented on low-cost microcontrollers for residential NILM. Processing aggregated power data at 8 s intervals, these networks achieved less than 12% disaggregation error, proving that compact deep models can operate efficiently on resource-constrained hardware. Such work reflected the growing movement toward edge AI, enabling decentralized analytics and low-latency decision-making within building systems. Another important direction concerns the deployment of ANNs as soft sensors and surrogates, reducing reliance on physics-based models that may be difficult or costly to develop. For example, in [135], researchers used a three-layer MLP to estimate natural ventilation airflow from readily available BMS variables (temperature differences, wind conditions, window geometry). Such an approach provided a scalable, low-cost alternative to continuous CFD or first-principles modeling, especially in retrofits where physical models are unavailable.As it is evident, across real-world case studies, interoperability remained essential. Most ANN modules interacted with existing BEMS layers via standard communication protocols (BACnet, EnOcean, Wi-Fi), supplying forecasts or supervisory setpoints without replacing core controllers [130,131,134]. Such modular integration preserved safety, supported retrofitting, and ensured compatibility with diverse hardware ecosystems. Architecturally, deployed ANNs tend to be compact—typically one to three hidden layers—trained with standard optimizers such as Adam and employing ReLU, tanh, or softmax activations depending on task requirements [130,131,135]. Practical deployments favor computational feasibility: hidden layers rarely exceed 5–50 neurons, and prediction horizons typically span 1–15 min to maintain fast inference on embedded platforms [131,132,135].A final trend involves contextual and personalized learning. ANN-based controllers were increasingly integrated physiological or behavioral indicators, enabling comfort and IAQ adaptation at the individual level. The occupant-feedback-driven comfort adaptation in [130] and the comfort-voting mechanism from [138] (from the RL domain) illustrated how personalized inputs are extending into ANN-based decision loops. Likewise, the authors of [134] incorporated metabolic and anthropometric features rendered into LSTM inputs, enabling personalized IAQ optimization in a working office environment.Overall, the reviewed real-world evidence suggests that ANNs are increasingly deployed as robust modules for prediction and supervisory control: real-world evidence illustrate that ANNs have matured into robust, deployable modules for prediction and supervisory control. Their advantages—as interpretability, ease of integration, computational efficiency, and ability to incorporate temporal and contextual information—render them well suited solutions for live building operation. As reflected in the reviewed case studies, ANN-based methods extend beyond offline modeling tools to fully operational components capable of real-time adaptation, personalized comfort support, and cost-effective energy optimization in modern BEMS.

Figure 9. Left: Occurrence of ANN types in real-world BEMS applications; Center: Occurrence of RL types in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Occurrence of FLC types in real-world BEMS applications.A second emerging trend concerned embedded and edge-deployed ANN models for distributed control and monitoring. In [132,133], 1-D CNNs and LSTM predictors were implemented on low-cost microcontrollers for residential NILM. Processing aggregated power data at 8 s intervals, these networks achieved less than 12% disaggregation error, proving that compact deep models can operate efficiently on resource-constrained hardware. Such work reflected the growing movement toward edge AI, enabling decentralized analytics and low-latency decision-making within building systems. Another important direction concerns the deployment of ANNs as soft sensors and surrogates, reducing reliance on physics-based models that may be difficult or costly to develop. For example, in [135], researchers used a three-layer MLP to estimate natural ventilation airflow from readily available BMS variables (temperature differences, wind conditions, window geometry). Such an approach provided a scalable, low-cost alternative to continuous CFD or first-principles modeling, especially in retrofits where physical models are unavailable.As it is evident, across real-world case studies, interoperability remained essential. Most ANN modules interacted with existing BEMS layers via standard communication protocols (BACnet, EnOcean, Wi-Fi), supplying forecasts or supervisory setpoints without replacing core controllers [130,131,134]. Such modular integration preserved safety, supported retrofitting, and ensured compatibility with diverse hardware ecosystems. Architecturally, deployed ANNs tend to be compact—typically one to three hidden layers—trained with standard optimizers such as Adam and employing ReLU, tanh, or softmax activations depending on task requirements [130,131,135]. Practical deployments favor computational feasibility: hidden layers rarely exceed 5–50 neurons, and prediction horizons typically span 1–15 min to maintain fast inference on embedded platforms [131,132,135].A final trend involves contextual and personalized learning. ANN-based controllers were increasingly integrated physiological or behavioral indicators, enabling comfort and IAQ adaptation at the individual level. The occupant-feedback-driven comfort adaptation in [130] and the comfort-voting mechanism from [138] (from the RL domain) illustrated how personalized inputs are extending into ANN-based decision loops. Likewise, the authors of [134] incorporated metabolic and anthropometric features rendered into LSTM inputs, enabling personalized IAQ optimization in a working office environment.Overall, the reviewed real-world evidence suggests that ANNs are increasingly deployed as robust modules for prediction and supervisory control: real-world evidence illustrate that ANNs have matured into robust, deployable modules for prediction and supervisory control. Their advantages—as interpretability, ease of integration, computational efficiency, and ability to incorporate temporal and contextual information—render them well suited solutions for live building operation. As reflected in the reviewed case studies, ANN-based methods extend beyond offline modeling tools to fully operational components capable of real-time adaptation, personalized comfort support, and cost-effective energy optimization in modern BEMS. - Reinforcement Learning: Unlike MPC, model-free RL algorithms learn control strategies directly from interaction data rather than from explicit physics-based models. Such a fact makes them naturally suited to buildings, where nonlinear thermal dynamics, stochastic occupancy, and volatile renewable generation create conditions that are difficult to capture analytically. The advantages of such an ML type were clearly demonstrated in [139], where a DQN RL algorithm was inferred from HVAC setpoints solely from environmental states and tariff signals, and in [141], where a SAC RL agent which controlled a real Thermally Activated Building System (TABS) installation using only sensor data achieved MPC-like predictive behavior without any plant model.Compared with simulation-heavy literature, real-world RL deployments remain limited; however, the evaluation reveals a consistent methodological pattern centered on safety, adaptability, and stable field performance. The dominant strategy is offline pre-training followed by online fine-tuning, which reduces the risks of unsafe exploration in occupied buildings. Historical data allow a policy to train before interacting with the real system, thus ensuring safe initialization. This approach has been identified clearly in [136], where a FQI agent was batch-trained on DHW–PV trajectories and then updated hourly online. Similarly, in [137] researchers employed a DDPG agent pretrained using an EnergyPlus–Modelica co-simulation, and ref. [138] initialized a BDQ RL agent through offline Modelica training prior to human-guided online refinement. Taken together, such studies consistently report offline–online hybrid learning as a practical and field-safe RL deployment strategy. Architectural patterns also converge across real implementations: The actor–critic framework has effectively become a default design due to its sample efficiency and stable policy convergence (See Figure 9-Center). Off-policy methods such as DDPG and SAC [137,141] dominated continuous-control tasks, whereas PPO variants were more common in mixed or discrete settings [140,142,143]. The actor computes continuous actions, while the critic stabilizes training by evaluating value functions. Several real deployments refined such algorithms further: ref. [140] introduced a dual-loop retraining scheme for robustness under non-stationarity, and ref. [142] incorporated invalid-action masking to block unsafe HVAC setpoints. Such adjustments demonstrated how real building constraints are shaping practical RL design.Another complementary trend involved integrating imitation or human-in-the-loop learning to improve convergence speed and interpretability. In [143], a PPO controller was initialized via Behavioural Cloning from legacy rule-based data before online RL adaptation. In [138], occupant comfort feedback updated the BDQ agent’s reward and policy in real time. Such integrated RL schemes combined the stability of supervised learning with the adaptability of RL, reducing exploration time and aligning RL decisions with human comfort expectations. Finally, recent work places increasing emphasis on continual learning, safety monitoring, and trustworthy AI techniques. The PPO controller in [140] detected policy degradation via cumulative reward trends and triggered offline retraining with Elastic Weight Consolidation to prevent catastrophic forgetting. The Maskable PPO in [142] enforced comfort and safety constraints by dynamically filtering out unsafe actions during exploration. These mechanisms illustrate a broader shift toward RL architectures that are not only adaptive but also dependable during long-term, real-building operation.Overall, real-world RL deployments in BEMS now follow a mature algorithmic blueprint: (i) offline pre-training for safety, (ii) actor–critic architectures for stable learning, (iii) imitation or human-in-the-loop adjustments for improved adaptability, and (iv) safety-enhancing mechanisms such as masking, reward shaping, or continual-learning loops. When combined with standard BEMS integration, such practices allow RL controllers to operate continuously in occupied buildings, maintain comfort, and adapt to uncertain environmental and occupancy dynamics.

- Fuzzy Logic Control: Real-world FLC applications have evolved from simple comfort heuristics to adaptive, multi-input, and hardware-embedded intelligent controllers. Early demonstrations—such as [144]—showed how occupant-driven fuzzy systems could directly translate human thermal feedback into HVAC actions using a Mamdani inference structure. Here, subjective states (“too cold”- “neutral”-“too hot”) were fuzzified and converted into setpoint adjustments, forming a foundation for human-in-the-loop HVAC control that adapted continuously to individual preferences and uncertain occupant responses. Subsequent field test studies extended FLC towards more autonomous and environment-aware thermal regulation. In [145], a Mamdani controller using indoor temperature, its derivative, and outdoor temperature delivered smooth, anticipatory heating control without any prediction model—showing that fuzzy reasoning can mimic MPC-like behavior at a fraction of the computational cost. Likewise, ref. [146] integrated wearable-sensor data (skin temperature, its rate of change, heart rate) into a Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation module, fusing multiple occupants’ sensations into a single comfort index for zone-level HVAC adaptation in a real office. Such works illustrated how fuzzy logic naturally accommodates uncertainty, heterogeneous feedback, and nonlinear thermal behavior.A parallel line of development concerned hybrid fuzzy–PID control structures, designed to address multivariable, nonlinear building environments without sacrificing interpretability. In [148], a Multiple-Input Multiple-Output fuzzy–PID controller with 81 rules dynamically tuned PID gains to regulate temperature, humidity, and air quality simultaneously in a real poultry facility—achieving high comfort stability under volatile microclimatic conditions. Similarly, in [149] researchers integrated a Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy supervisor with an MLP–NARX model that captured occupancy-driven heating dynamics, enabling an adaptive, rule-based strategy integrated with EnOcean wireless sensing and PLC hardware in a multi-storey academic building. Recent FLC implementations increasingly emphasized embedded and edge-deployable fuzzy control. In [147], a Mamdani FLC was embedded directly into a smart-meter prototype, controlling PV–battery interactions every 60 s and managing stochastic load and PV fluctuations on low-power hardware. Likewise, in [150] FLC embedded a 49-rule Mamdani for AHU temperature regulation onto an ESP32 microcontroller, demonstrating robust, real-time performance under hardware-in-the-loop testing. In the broader energy domain, ref. [151] deployed a Sugeno-type FLC on an edge PC to manage PV–battery power flows through Modbus-based communication with inverters and sensors, using 45 adaptive rules to balance load, state of charge, and electricity prices in real time. Such studies have indicated that FLC may be computationally lightweight and also highly compatible with IoT- and PLC-based BEMS architectures.Across these real-world applications, fuzzy control retains two defining strengths: interpretability and robustness under uncertainty. Mamdani-type controllers, favored in comfort-oriented settings (See Figure 9-Right) [144,145,146], provide transparent rule bases that building operators can understand and adjust. In contrast, Sugeno or fuzzy–PID hybrids dominate energy management and grid-interactive applications [148,149,151] due to their computational simplicity and smooth output surfaces (See Figure 9). Architecturally, FLC designs remain compact—typically two to three inputs and 25–81 rules—yet fully compatible with common BEMS communication layers (LabVIEW, PLCs, Modbus, EnOcean), allowing safe, plug-and-play deployment. In summary, real-world FLC usage has expanded from occupant-centric comfort tuning [144] to adaptive, multi-input, hybrid, and embedded architectures [145,148,150,151]. These systems leverage fuzzy inference’s interpretability and resilience to uncertainty, offering reliable, low-cost, and scalable performance across HVAC, IAQ, PV–battery management, and broader smart-grid applications.

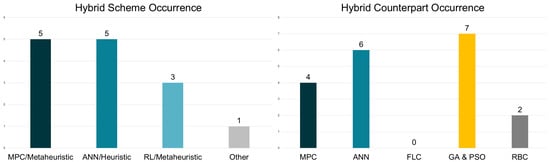

- Hybrids: Real-world hybrid ML controllers seem to follow a practical pattern: they combine predictive intelligence—using statistical forecasts, learned models, or digital-twin surrogates—with an optimization or search layer that produces real-time setpoints. A common design uses time-series forecasting and state estimation to feed a metaheuristic optimizer, which then searches for suitable control sequences. For example, ref. [152] integrates demand forecasting, a hybrid thermal/Kalman estimator, and an ACO/Simulated Annealing search to select domestic hot-water reheat schedules over a 48 h/5 min horizon. Other variants simply swap the search strategy: ref. [153] uses a Random Neural Network trained with PSO and SQP for HVAC control in an IoT BEMS, while [162] combines Random Forest forecasts with a GA scheduler for day-ahead multi-vector energy management. Some studies incorporate knowledge-based reasoning as well—for instance, [155], where MLP occupancy predictions support case-based reasoning (CBR) selecting HVAC actions within a lightweight multi-agent framework.A second major stream fused classical MPC structure with ML flexibility. One way was to adapt the MPC model online: ref. [156] updates linear zone models using RLS and then runs LP/QCQP MPC in a hierarchical, MQTT-based allocator across 85 zones. Another approach was to train ANNs to imitate MPC itself. In [160], a NARX-RNN learns MPC trajectories (60 min horizon, 5 min steps), replacing online optimization with fast policy inference while preserving MPC-like control. Several hybrids also separated slow planning from fast operation: ref. [158] used PSO to size storage for cost minimization, while MPC handles 24 h/5 min real-time heat-pump and battery control; ref. [159] used also PSO for day-ahead flexible-load scheduling and an RBC for stable real-time dispatch.A third family utilized calibrated ML surrogates to enable safe learning and fast control. For instance, in [157], an EnergyPlus model was calibrated using GA and Bayesian methods, accelerated using a Random Forest PID surrogate, and then used to train an A3C policy that transfers reliably to a real HVAC system. NILM-oriented hybrids also appeared in the literature: ref. [161] employed RBFNN predictors optimized via a multi-objective GA to perform appliance disaggregation at 1 min sampling, supporting downstream control in an embedded HEMS. At the minimalist end, ref. [164] utilized an ALAMO-based surrogate to feed a predictive rule-based controller on a PLC, achieving accurate preheating without relying on cloud computation.Recent hybrid controllers explicitly incorporated safety and explainability by pairing learning modules with constraint-handling or transparent fallback layers. In [163], a residential microgrid controller used TD3, alongside a MILP MPC planner and a PSO-trained decision tree for interpretable fallback control. In a multi-zone HVAC system, ref. [165] combine feature selection (ReliefF), deep sequence prediction (CNN–BiLSTM), and a Whale Optimization Algorithm (tuned the PID), creating a stable pipeline where ML handles forecasting and the PID ensures reliable actuation.Across deployments, hybrid pipelines follow a common logic: forecast or identify the state/optimize or schedule/supervise or track, using horizons and timesteps that match the building’s physical dynamics (typically 12–48 h horizons with 1–15 min control). Metaheuristics or MILP/LP/QCQP solvers are used when equipment modes or discrete logic dominate, while learned surrogates or MPC-distilled policies are used to keep real-time computation light. Most computation is pushed toward the edge—via MQTT, BACnet, or REST—ensuring low latency, modularity, and fault isolation [152,153,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165].Reviewing all real-life hybrid BEMS deployments, three families consistently dominate (See Figure 10-Left): (i) MPC/Metaheuristic hybrids—where MPC is paired with PSO or GA—are frequently used for multi-energy scheduling and handling nonlinearities [158,161,162]. (ii) ANN/Heuristic or ANN/Surrogate hybrids use neural predictors or surrogate models to support rule-based or optimization layers with low computation cost [153,155,165]. (iii) RL/Optimization hybrids blend the adaptability of Reinforcement Learning with the safety of optimization, showing promising results in HVAC, RES, and storage coordination [152,157,163]. Overall, real-world practice favors combinations that merge accurate prediction with robust, explainable optimization—ensuring both adaptability and operational reliability in BEMS.

Figure 10. Left: Occurrence of hybrid schemes in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Occurrence of hybrid counterparts in real-world BEMS applications.Last but not least, real-world hybrid control strategies, commonly combined metaheuristics (like GA and PSO), ANN predictors (such as LSTM or NARX), and traditional MPC schemes (see Figure 10-Left) should be mentioned in terms of the algorithmic schemes. Such setups typically used ML models to forecast conditions or learn system behavior, while an optimization layer—like MPC—handled real-time decision-making and constraint enforcement. This combination is able to balance prediction accuracy with operational safety and reliability. As a result, hybrid approaches proved to be among the most flexible and deployment-ready control solutions, effectively managing HVAC, PV, storage, and hot water systems in real buildings across different climates.

Figure 10. Left: Occurrence of hybrid schemes in real-world BEMS applications; Right: Occurrence of hybrid counterparts in real-world BEMS applications.Last but not least, real-world hybrid control strategies, commonly combined metaheuristics (like GA and PSO), ANN predictors (such as LSTM or NARX), and traditional MPC schemes (see Figure 10-Left) should be mentioned in terms of the algorithmic schemes. Such setups typically used ML models to forecast conditions or learn system behavior, while an optimization layer—like MPC—handled real-time decision-making and constraint enforcement. This combination is able to balance prediction accuracy with operational safety and reliability. As a result, hybrid approaches proved to be among the most flexible and deployment-ready control solutions, effectively managing HVAC, PV, storage, and hot water systems in real buildings across different climates.

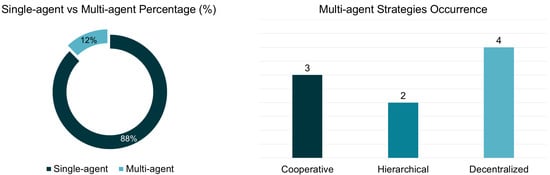

6.1.2. Evaluation per Agent Architecture

Multi-agent control implementations in real-world setting were limited in number (See Figure 11-Left), however such innovative practice seems to gradually evolving from experimental prototypes to mature coordination frameworks. According to evaluation, three clear families of multi-agent strategies have emerged across real buildings: Cooperative distributed MPC architectures, where intelligence is divided among agents responding to autonomous building zones that iteratively reach consensus through optimization-based coordination. Studies such as [105,119] showed that consensus mechanisms—either via ADMM or virtual-price dual decomposition—enable agents to maintain autonomy while converging to near-centralized performance. Such cooperative distributed MPCs emphasize convex coordination, peer-to-peer communication, and real-time feasibility, proving that full centralization is unnecessary for high performance. Such a multi-agent scheme presented the most extensively validated form of optimization-based multi-agent control in real buildings [75] (See Figure 11-Right).

Figure 11.

Left: Percentage (%) of single-agent vs. multi-agent real-world applications for BEMS; Right: Occurrence of multi-agent strategies (cooperative, hierarchical, fully decentralized) in real-world applications for BEMS.

A second trend involves hierarchical multi-agent systems that distribute prediction and reasoning across functional layers. In these, local agents—corresponding to different building zones or energy systems—handle data-driven forecasting or comfort modeling at the edge, while a supervisory coordinator allocates energy resources. Such a pattern has been demonstrated in [133,155,156], combining local learning and global scheduling and resulting in reduced communication load, higher robustness, and easier integration of complex subsystems, such as HVAC, TSS, and PV. Such hierarchy among agents also enabled privacy-preserving collaboration through federated or case-based reasoning, allowing each agent to learn independently but contribute collectively to system-wide optimization. The hierarchical—or layered—multi-agent algorithmic systems particularly suited for large, sensor-rich environments, reflecting a transition toward edge–cloud intelligence fusion in building control.

The third direction highlighted fully decentralized and model-free multi-agent strategies. Works like [166,167] illustrated that agents may cooperate without any global model or solver, relying only on local feedback or shared scalar performance indices. Such lightweight designs proved able to deliver plug-and-play scalability, resilience to communication loss, and minimal computational cost, marking a promising path for low-infrastructure retrofits. Similarly, occupant-centric fuzzy controllers such as [144], embed humans as agents, transforming comfort feedback into decentralized control signals, thus introducing social intelligence into the energy loop. Together, these approaches revealed a growing movement toward self-organizing, low-communication, and adaptive control paradigms capable of operating autonomously yet coherently (See Figure 11-Right).