Abstract

This study investigates the role of biogas and biomethane in accelerating the decarbonization of district heating systems in Europe. A structured literature review combined with two representative case studies evaluate technological, economic, and environmental performance across different system scales. The Meppel optimization model developed for the Netherlands and the large-scale Backbone energy system modelling framework for Finland are compared to identify methodological synergies and operational insights for integrating bioenergy into heating networks. The results show that biogas-based combined heat and power systems can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by more than 70 percent compared with fossil-based alternatives and significantly improve local energy security, especially when coupled with heat pumps and thermal storage. Large-scale modelling further demonstrates that biomethane and bioenergy resources provide valuable system flexibility, facilitating sector coupling and supporting the balancing of variable renewable electricity production. This study’s main contribution is an integrated comparative assessment at two different scales (local and regional), linking operational data, modelling, and performance results to determine how biogas and biomethane can optimize the energy system in the short and long term for centralized heat supply. The findings confirm that biogas and biomethane are essential, dispatchable renewable resources capable of supporting scalable, low-carbon, and resilient district heating systems across Europe.

1. Introduction

Decarbonizing the heating sector is necessary for achieving the European Union’s climate neutrality targets for 2050. District heating (DH) systems play an important role in this transition towards the efficient integration of renewable energy sources and waste heat into the heat energy supply. Among various renewable options, biogas and its upgraded form, biomethane, are valuable resources as they offer a sustainable, circular economy facilitating an alternative to fossil energy in existing natural gas infrastructure. These characteristics allow biogas and biomethane to complement variable renewable electricity, strengthen local production and security of supply, and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1,2,3].

Biogas is generated from organic waste, agricultural residues, and wastewater sludge via anaerobic digestion, supplying renewable energy and contributing to circular economy goals by turning waste streams into useful resources. When upgraded to biomethane, the resulting renewable gas can be injected directly into gas grids or used as a low-carbon fuel for combined heat and power (CHP) generation and district heating applications. Life-cycle assessments consistently show that replacing fossil natural gas with biogas-based energy can reduce GHG emissions by more than 70 percent, depending on feedstock and system configurations [3].

The energy transition in Europe and worldwide is driving a shift from fossil fuels toward low-carbon and renewable energy sources. Many countries, including Latvia, have set climate neutrality targets for 2050, and renewable and low-carbon gases represent a key tool for achieving these ambitions. In this context, biogas and biomethane serve as flexible energy carriers that complement the variable availability of renewable resources and enhance local energy security. District heating systems play an important role in decarbonizing the heating sector by enabling efficient heat distribution and the integration of renewable and waste heat sources. Achieving carbon neutrality at the municipal level may require a combination of district heating and individual renewable heating solutions, depending on infrastructure readiness and opportunities to increase the renewable share in heating [4].

Europe operates more than 21,000 biogas plants, with significant variation across different regions, producing approximately 234 TWh annually and accounting for about 7% of EU gas demand [5]. Germany alone hosts the largest share, with an estimated 9500 biogas plants, reflecting decades of various stimulating policy measures such as renewable energy incentives that have stimulated early and sustained growth [6]. In contrast, since 2025, France leads in the largest biomethane installed capacity (190,711 Nm3/h), followed by Germany (157,258 Nm3/h), Italy (99,658 Nm3/h), the United Kingdom (93,151 Nm3/h), and Denmark (85,142 Nm3/h). In contrast, in 2023 and in 2024, Lithuania and Latvia started their first biomethane grid injection [7]. France has implemented a 1.5 billion scheme to expand biomethane injection and transport infrastructure. Denmark has introduced a 1.7 billion renewable gas programme aimed at achieving full biomethane integration by 2030. Germany continues to lead European production through established feed-in tariffs and sustained capital investment. Italy has adopted new incentive decrees for 2022–2026 to support additional biomethane production capacity, showing the differences between status of biomethane development and support in European countries [8]. The shift from fossil to bio-based energy also stimulates regional development, job creation, and circular resource flows. However, despite these strengths, challenges remain, including variable production costs, methane-leakage risks, and competition with natural gas market prices [9].

District heating systems offer a practical and efficient way to use biogas and biomethane on a larger scale. When renewable heat production is combined with thermal storage, CHP units and, increasingly, heat pumps, district heating networks can achieve high efficiency, greater operational flexibility, and substantial emission reductions. However, the existing research on integrating bioenergy into district heating systems is still rather fragmented. Most studies concentrate on specific technologies or individual case studies, while broader comparative analyses that simultaneously address technical, economic, and environmental performance across different system scales are still limited [10].

The objective of this study is to address this gap through a structured comparative analysis of two representative European case studies: the Meppel district heating system in the Netherlands and the Backbone energy system modelling framework applied in Finland. The Meppel case illustrates local-scale optimization of a hybrid energy system combining biogas CHP, heat pumps, thermal storage, and district heating. The Backbone model represents large-scale, regional optimization of interconnected electricity, heating, and biomass supply systems. By comparing these systems, the study underlines important technological synergies, performance results, and analysis results regarding how biogas and biomethane can support both short- and long-term decarbonization of the centralized heat supply.

2. Methods and Methodology

The methods applied in this study are based on a structured review approach designed to systematically identify, summarize, and evaluate the scientific literature on the use of biogas and biomethane in district heating systems. This process enables a coherent assessment of current knowledge and supports development of an informed overview of the potential and practical applications of these renewable gases.

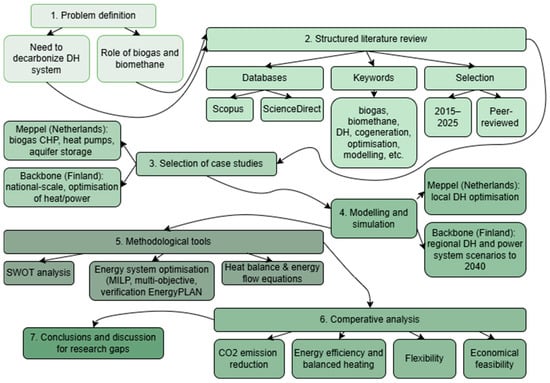

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the workflow adopted in this research. The process began with problem definition, followed by a structured literature review that informed the selection of relevant case studies. Subsequently, modelling approaches and analytical tools were identified, after which a comparative assessment was conducted. The workflow concluded with the formulation of key findings and the identification of discussion points and research gaps.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of used research methods and logic.

A strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis was applied as a structured framework to support strategic evaluation. Although relatively simple, it can provide a comprehensive and accessible overview for stakeholders. Although, SWOT is limited by subjectivity, static categorisation, and low prioritization capability, it offers value as an accessible tool for synthesizing diverse findings. Its shortcomings often necessitate more extensive research or the development of hybrid approaches, such as integrating multicriteria analysis methods to improve objectivity. However, its main advantages, such as ease of use and the ability to generate an integrated overview of findings, make it a valuable tool for forming an initial understanding of the topic [11,12].

Numerous studies have analyzed energy system optimization using mathematical modelling techniques. These methods are commonly categorized into single-objective and multi-objective approaches. Single-objective methods typically focus on minimizing annual costs, while multi-objective optimization incorporates additional criteria, such as emissions, enabling comprehensive assessment of system performance [13].

Several studies have examined the planning and operation of energy systems using mathematical optimization models. These models often address a single objective, such as reducing total annual or life-cycle costs, while others incorporate goals include environmental indicators, such as CO2 emissions [14,15].

Table 1 summarizes studies that primarily apply multi-objective optimization methods in energy system design, highlighting their context, methodological approach, and effectiveness.

Table 1.

Examples of decentralized and centralized energy system optimization (developed by the author using [16]).

Table 1 shows that multi-objective optimization consistently delivers considerable CO2 reductions (25–69%) and major cost savings across both centralized and decentralized energy systems.

A notable contribution to district heating system optimization is the work by Leeuwen et al., who developed a model for the Meppel area in the Netherlands [17]. The Meppel energy system combines biogas cogeneration, district heating, and ground-based heat pumps in an integrated configuration. A central combined heat and power (CHP) plant converts biogas from a municipal wastewater treatment facility into electricity and heat: the electricity drives the heat pumps, while the heat supplies the district heating network. Due to slower economic and construction progress, the system was implemented gradually, beginning with around 40 homes and expanding to 176. The energy system includes a biogas CHP plant, backup boilers, a high-temperature water storage tank, heat pumps, and aquifer thermal energy storage. Electricity from the CHP unit can be used locally or exported to the grid, and cooling demand is met through cold wells in the aquifer. Thermal balance is supported by heat recovery, and additional regeneration from dry coolers or the wastewater treatment plant. Leeuwen et al. developed an optimization model to maximize the profitability of this local energy system by analyzing heating and cooling demands. The model identified the optimal size and operation of the CHP unit and boilers across different scenarios and proposed a phased implementation approach. The first stage relies mainly on natural gas boilers and purchased green electricity, while later stages introduce biogas CHP and aquifer-based heat storage as supply and demand expand. A cooling unit is also incorporated to meet residential cooling requirements. System sustainability was evaluated by comparing fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emissions at each development phase, with particular attention to the second phase involving 160 houses [17,18].

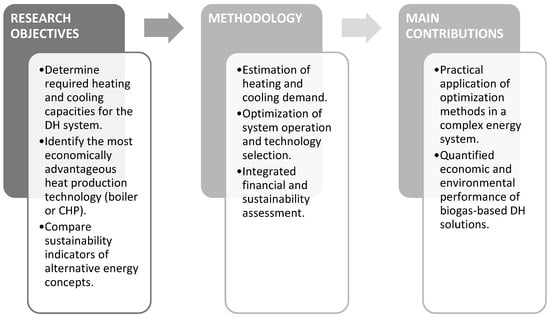

The study defined four cases and concluded that the use of biogas in district heating is a more sustainable solution. However, when the CHP unit operates on natural gas, it is only about 6% more sustainable than in cases with conventional heating with gas boilers. The study’s objectives and contributions are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research objectives and main analytical contributions of the study, illustrating the relationship between system design, optimization modelling, and sustainability performance (developed by the author using [17]).

Figure 2 summarizes how system analysis and optimization are used to evaluate the economic and environmental performance of biogas-based district heating solutions. It shows the research structure of the study, including the progression from the main research objectives through the applied methodology to the main scientific contributions.

A structured literature review was conducted using high-quality databases, in particular ScienceDirect and Scopus. To assess the existing research base, the search combined keywords such as “biogas,” “biomethane,” “district heating,” “energy system optimization,” “cogeneration,” “modelling,” and “heating calculations.” The inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2015 and 2025, written in English, and dedicated to the use of biogas or biomethane in district heating or integrated energy systems. To ensure that this article remained focused on district heating applications, research that addressed only small-capacity or off-grid biogas systems without clear links to district heating networks was excluded. Such systems differ fundamentally in scale and operational purpose, as off-grid biogas and biomethane facilities typically supply energy for on-site use, small nearby buildings, or internal transport needs. Their technological configurations, economic boundary conditions, and environmental performance are therefore not directly comparable to centralized district heating systems, which require continuous heat provision, interconnected thermal networks, and centralized or semi-centralized production assets. For these reasons, studies examining small-capacity or stand-alone systems were excluded to avoid distorting the comparative assessment and to ensure that the conclusions remain directly relevant to district heating applications.

Two representative case studies were selected for detailed analysis based on their methodological diversity and relevance to different European contexts: the Backbone model in Finland, where a large-scale mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) optimization framework was applied to Nordic and European energy systems, emphasizing the integration of bioenergy resources and district heating in system operation and investment planning [18]; and the Meppel city case study in the Netherlands, where a local scale optimization model combining biogas cogeneration, district heating, and heat pumps, designed to assess system performance, energy balance, and sustainability in an urban context, was applied [17].

Key data on system configuration, fuel mix, efficiency, CO2 reduction potential and techno-economic parameters were extracted from each case study. A comparative analysis was then carried out, focusing on four main dimensions: (1) modelling approaches and optimization methods, (2) energy and emission performance, (3) operational flexibility and renewable energy integration, and (4) policy and investment impacts.

This structured comparison provides a broader perspective, from a city-scale microsystem (Meppel) to modelling of national and regional systems (Backbone).

2.1. Methodology and Meppel District Heating Case

The methodology used by Leeuwen et al. employs a mathematical optimization model designed to identify economically optimal configurations for district heating (DH) systems integrating biogas CHP, boilers, and heat storage. The developed optimization model was intended to serve as a validation tool for verifying additional modelling carried out using the EnergyPLAN system [17].

The initial concept of a district heating system is defined by the efficiency of its converters, the characteristics of energy resources, energy demand, and energy flows. A summary of the main research methods and examples of their application for evaluating biogas and other energy sources for use in district heating is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Structured research methods and elements.

The energy concept from the Netherlands served as a pilot system: it combines a biogas-fuelled CHP engine, backup gas boilers, a high-temperature (HT) water tank, heat pumps, and aquifer thermal energy storage. The CHP provides electricity for the heat pumps and heat to the district network. Cooling is provided via an aquifer-based system using heat–cold storage wells.

Model objectives include the following (see Table 3):

Table 3.

Key aspects of the optimization model (developed by the author using [11]).

- Determining required heating and cooling capacities for the DH network;

- Identifying optimal combinations of CHP and boilers from an economic (cost) perspective;

- Evaluating CO2 emission reductions under biogas and natural gas operation [17].

2.2. Backbone Energy System Modelling Framework

For macro-scale modelling, the Backbone framework was applied. Backbone is an open-source energy systems model implemented in Python and solved using mixed-integer linear programming (MILP). It enables the temporal and spatial optimization of interconnected electricity, heating, and biomass supply systems.

The model represents:

- Northern European power systems (Module A),

- Finnish bioenergy and heat sectors (Modules B and C),

- Cross-border electricity exchanges and biomass resource flows.

The input datasets included the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E) power capacities, the Natural Resources Institute Finland (LUKE) biomass statistics, and meteorological data, which were pre-processed to ensure their compatibility with the Backbone model’s time steps and geographical resolution. Power capacity data from ENTSO-E were grouped by major generation types and aligned with the model’s hourly time steps. Biomass availability data from LUKE were converted into annual supply estimates. Meteorological datasets were processed into hourly temperature and renewable resource profiles to represent seasonal and daily variability in heat demand and system performance. To deal with uncertainty in the input data, we tested how changes in important factors affected the results. The model evaluates scenarios up to 2040 with progressive decarbonization measures—coal phaseout, biomass substitution, and large-scale heat pumps in Helsinki and other Finnish DH networks [18]. A simplified visualization of both system cases is presented in Figure 3.

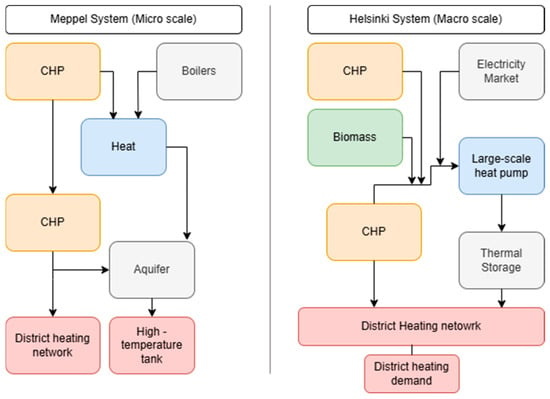

Figure 3.

Visualization of systems.

The Meppel district system represents a small, local district heating network with only a few components (CHP, boilers, aquifer) that is used by a small number of buildings. In energy-system terminology, this kind of setup is commonly described as micro-scale because it covers a relatively small geographic area, there are not many heat sources, and it has some decentralized units. The Helsinki system is a city-wide district heating network with many heat sources (biomass, electricity market, heat pumps, CHP), and it uses large-scale storage and central infrastructure supplying a large number of consumers.

3. Results

3.1. Biogas Utilization and Environmental Benefits

Biogas typically consists of about 60% methane (CH4) and 40% CO2, with small traces of H2 and other gases. Through anaerobic digestion (AD), agricultural residues, wastewater sludge, and municipal waste are converted into renewable energy and digestate fertilizer. Upgrading biogas to biomethane enables its use for grid injection and transport applications.

Life-cycle analyses indicate that replacing fossil gas with biogas in CHP systems can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 70–90%, depending on feedstock. The reduction in emissions reflects differences in the origin of biogas feedstocks and related life-cycle stages. Emissions from biogas systems mainly arise from feedstock production and transport, anaerobic digestion, and gas purification. In contrast, emissions associated with fossil natural gas mainly arise from extraction, processing, transport, and infrastructure leaks. Agricultural residues and separately collected organic waste offer smaller but still significant net reductions. By comparison, energy crops generally offer lower savings due to emissions associated with cultivation. Emission figures are highly dependent on the type of feedstock and boundary conditions, not just combustion efficiency [6].

Biogas cogeneration emissions are significantly lower than those from fossil natural gas systems because the carbon released during combustion comes from recent biogenic sources rather than geologically stored carbon [19]. As a result, the resulting CO2 emissions are generally considered carbon neutral, as they are part of the short-term biological carbon cycle and do not contribute to net atmospheric accumulation [20]. Thus, the main greenhouse gas benefit comes from avoiding methane emissions associated with manure and organic waste management, as well as from the replacement of fossil fuels in heat and power production. These mechanisms explain the emission reductions observed in biogas cogeneration systems, regardless of carbon dioxide capture in the biogas purification process.

Centralized energy network (DEN) optimal variables include the following:

- Heat carrier supply temperature, flow rate, and total energy consumption and cost [21];

- Storage capacity [22];

- The layout of the energy network [23], etc.

DEN optimization algorithms mainly include the hybrid evolution and mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) methods [24], as well as genetic algorithms [22].

Integrating renewable energy sources and recovering waste heat in district heating energy network (DEN) systems is crucial for reducing the environmental impact of the building sector, supporting sustainability goals, and decreasing environmental pollution. Examples include the use of hydropower [25], photovoltaic technologies [26,27], and waste heat from coking furnaces [26]. These solutions are also the most beneficial and energy efficient in the long term.

Based on ref. [28], the main problems with DEN include the following:

- Significant initial investment and high maintenance costs;

- The need for local authorities to provide financial support and develop a detailed plan and design strategy before the network is built.

The main challenge of research is the efficient and smooth integration of several energy systems and renewables into the DEN structure. The main challenge of DEN technology is that the same pipelines cannot provide both heating and cooling for different buildings at the same time [29].

The study [28] draws conclusions explaining the operation and optimization capabilities of DH and Centralized Energy Networks (DENs) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Main results and examples for DEN development.

Fifth-generation district heating and cooling (5GDHC) networks are still under development; however, several systems are already operating in Europe, many of them launched as pilot projects. These systems differ significantly from conventional district heating technologies. In 5GDHC networks, water is supplied to decentralized water source heat pump (WSHP) stations at temperatures between 0 °C and 30 °C, providing several advantages over traditional high-temperature systems.

5GDHC allows network temperatures to fluctuate freely and makes use of locally available low-grade heat sources. Distribution temperatures close to ground temperature result in minimal heat losses, enable operation in both heating and cooling modes regardless of grid temperature, and allow for bidirectional, decentralized energy flows. These characteristics align closely with the concept of smart heating networks, as 5GDHC employs hybrid substations and facilitates sector coupling between electricity and heat within a smart energy system [30].

With the growing transport electrification and other energy sectors, 5GDHC can further support the sustainable and efficient electrification of urban heating. Table 5 summarizes the main opportunities and challenges associated with the deployment of 5GDHC systems in existing infrastructure, highlighting their potential role in future low-carbon district heating development.

Table 5.

Fifth-generation district heating systems SWOT analysis results.

The high implementation costs of 5GDHC systems can be reduced by phased development, modular network expansion, and wider use of lower-cost piping and standardized heat pump designs, which can reduce initial investment requirements and risk exposure. Economic viability may be strengthened through targeted incentives, including capital grants or carbon-linked heat tariffs. The current lack of technical standards can be alleviated through pilot projects and coordinated data sharing at municipal or national levels, supporting the development of common design and operating guidelines and reducing uncertainty for broader deployment.

The advantages of 5GDHC over air-sourced heat pump systems are relatively numerous [29,31,32]. These include a higher source temperature in the heating mode and a lower source temperature in the cooling mode compared to ambient air, which enable higher seasonal system performance. Another advantage of 5GDHC systems is that centralized solutions can incorporate seasonal heat storage in urban environments, where the installation of individual ground-source heat pump heat exchangers may be limited. In addition, the diversity and simultaneity of building loads increase the potential for recovering excess heat from cooling processes for use in heating [29]. Since 5GDHC is still an emerging and relatively understudied field, expertise in this technology remains concentrated within a limited number of companies. Moreover, the use of local heat sources and the introduction of decentralized “active” substations support a shift away from traditional monopolistic district heating and cooling (DHC) structures and encourage the development of new business models for multi-service enterprises. Designers currently lack technical standards and guidelines, and there is insufficient knowledge regarding the operational optimization and management of 5GDHC systems [33]. The study by [29] reviewed 40 operational 5GDHC networks, most of which are located in Germany and Switzerland (75%), making these countries the leaders in deploying this technology. The main drivers behind the adoption of 5GDHC are the intentions of local authorities, building investors, and communities to choose sustainable heating and cooling solutions [19,24].

3.2. Economic Optimization Outcomes (Meppel Case)

The optimization and scenario analysis based on the Meppel district heating system [17] compared four concepts: Scenario 1—a biogas-fired combined heat and power (CHP) system with natural gas backup boilers, Scenario 2—district heating using only gas boilers, Scenario 3—individual gas boilers in each house, and Scenario 4—rooftop solar photovoltaics with gas backup heating. Of these solutions, Scenario 1, which uses biogas in cogeneration, proved to be the most sustainable, combining the use of local renewable energy resources and the efficient nature of the cogeneration process. The economic efficiency of Scenario 1 was assessed using the results of operations and resource use, which showed significantly lower fuel consumption and emissions compared to the alternatives. The biogas cogeneration configuration required the lowest annual fuel consumption (6.18 TJ of biogas and 1.65 TJ of natural gas), provided the highest combined efficiency (about 88%), and reduced CO2 emissions by approximately 80% compared to conventional individual heating, indicating improved economic prospects associated with lower fuel costs and less impact on carbon pricing. In contrast, the system using only boilers (Scenario 2) performed the worst, consuming almost 9.8 TJ of natural gas and emitting more than 500 t of CO2 per year. Scenario 3 (individual gas boilers) emitted around 430 t of CO2 per year, while Scenario 4 (solar photovoltaics and gas) achieved a 50% reduction in emissions by offsetting grid electricity with on-site solar energy.

The model also revealed that the total heat demand in the district was around 4–5 TJ per year, whereas individual households required 12–20 GJ per year, depending on building type. Cooling needs were significantly lower (around 5–10 GJ per year per household) and were partly covered by a water-layer storage system. Using mathematical relationships between the electrical and thermal outputs of the CHP and the heat pump coefficient of performance (COP of about 3.5–4), the study calculated that for every MJ of heat produced by the heat pump, only 0.25–0.3 MJ of electricity was required, thereby improving overall energy efficiency. The CHP achieved a combined efficiency of around 88%, with a capacity ratio of approximately 1.45 MJ of heat per 1 MJ of electricity produced.

The simplified optimization model effectively determined the optimal system size and operating strategies, suggesting a gradual implementation that begins with a small cogeneration unit and increases in size as the neighbourhood expands. The methodology successfully balances technical design, economic justification, and environmental impact. Despite simplifications such as fixed efficiency indicators, static tariffs, and steady-state assumptions, this approach proved effective in the initial planning phase and in comparing district heating scenarios.

The optimization for Meppel case demonstrated that biogas-based CHP achieves the best balance between efficiency and emissions when operated continuously with heat storage. Systems using natural gas CHP are only ~6% more sustainable than standard gas boiler systems, while biogas improves sustainability by >30%. The inclusion of heat storage (125 L per household at 90 °C) increases operational stability and profitability. The results show that integrating local renewable energy sources (biogas, solar panels) with cogeneration provides the greatest sustainability gains for urban energy systems such as Meppel.

3.3. Backbone Simulation Insights (Finland Case)

The results of the study demonstrate the applicability and flexibility of the Backbone energy system modelling framework for the analysis of complex, multi-level energy systems in Northern Europe. The Backbone model was applied as a unit engagement and economic allocation tool with a variable time horizon, focusing on optimizing the operation of existing assets rather than on making new investment decisions. The model successfully captured the interactions between the Northern European electricity system, the Finnish district heating network, and the regional forest biomass supply, providing an integrated view of energy flows, resource availability, and system-level constraints.

The results show that the modelled system effectively reflected the chosen decarbonization path of the Nordic energy sector, which was mainly driven by a significant increase in wind and solar power generation. The main results from the model calculations for the 2030 baseline scenario and their comparison with 2017 statistics showed that in Finland, the share of biomass and hydropower also increased slightly, while nuclear power generation was projected to decrease by around 35%. In the district heating sector, coal and peat were gradually replaced by forest residues, small-diameter wood, imported pellet fuels, heat pumps, and natural gas. The model confirmed that large-scale heat pumps provide the lowest marginal costs and serve as baseload technologies, while biomass boilers operated almost all year round except for summer. Energy storage facilities, in particular thermal storage facilities, play an important role in balancing short-term fluctuations in demand and production. Scenario analysis revealed significant flexibility in adapting to changing operational and market conditions. Combining local district heating systems with those of neighbouring cities improved system stability and reduced overall operating costs. Economic indicators such as payback period and internal rate of return (IRR) demonstrate that biomass heating technologies can be financially viable, especially if carbon pricing and fuel taxation policies promote solutions that generate the lowest possible emissions. The Backbone system, thanks to its transparent modular structure, is considered well suited to combining the electricity, heat, and biomass sectors in long-term planning while maintaining the possibility of a detailed evaluation of the results of each operation.

The Backbone simulation of Finland’s DH transition shows a 30% reduction in DH heat demand by 2040 due to efficiency gains; the replacement of coal and peat with biomass residues, heat pumps, and gas backup; the gradual decline of nuclear generation offset by wind and solar increases; and the CHP plant achieving greater emission reductions at the overall system level.

Biomass and biogas integration in DH lead to significant reductions in carbon emissions without compromising supply security. In Helsinki, large-scale heat pumps (60 MW) and storage (11 GWh) further improve flexibility and emission reduction potential.

4. Discussion/Conclusions

This integrated study demonstrates that biogas and biomethane can be an important part of the decarbonization of district heating in Europe. The optimization framework developed by Leeuwen provides evidence that locally integrated systems can achieve strong cost and emission performance, while the Backbone model highlights the long-term scalability of bioenergy resources and their interactions within regional energy systems.

The comparative analysis indicates that both cases demonstrate the potential of biogas in district heating to support the energy transition, particularly by coupling renewable energy production directly with heat networks. The Backbone model emphasizes the importance of incorporating bioenergy resources into large-scale, multi-sector energy systems, optimizing resource allocation while maintaining operational reliability. It further shows that district heating can operate as a balancing mechanism, especially when combined with bioenergy, energy storage, and variable renewable electricity generation.

The Meppel case provides insight into hybrid system configurations in which biogas cogeneration units operate alongside heat pumps and thermal storage. This approach enhances local energy self-sufficiency, supports flexible demand management, and offers a practical model for small- and medium-sized communities that may be replicated in similar contexts.

Identified technological trends include the increasing use of digital optimization tools, such as mixed-integer linear programming models illustrated by the Backbone framework. In parallel, the development of hybrid energy systems that combine bioenergy and heat pumps is gaining attention as a promising approach for achieving efficient and resilient energy systems.

The main conclusions are that biogas-based CHP and upgraded biomethane provide dispatchable renewable heat and power compatible with existing infrastructure, deliver substantial GHG reductions (>70%) compared to fossil systems, and remain competitive under supportive carbon pricing and stable policy frameworks (e.g., the RED III target of 35 bcm of biomethane by 2030). National-level Backbone simulations confirm strong synergies between biogas, biomass, and electrified heating technologies.

The findings of this study are consistent with other research showing that biogas and biomethane integration can enhance emission performance and energy system flexibility in district heating applications. Previous work confirms the environmental benefits of anaerobic digestion and waste valorization [3]. Studies on municipal heating transitions indicate that combining district heating with individual renewable heat sources may be required to reach carbon neutrality targets [4], while research on integrated heating networks demonstrates that increased operational flexibility supports higher renewable energy share and lower system costs [10]. Combined, these comparisons reinforce the present study’s conclusion that biogas-based cogeneration and biomethane integration offer a reliable way to low-carbon, resilient district heating systems.

Current research often relies on modelled rather than measured performance data and gives limited attention to social factors that influence local acceptance of specific energy sources. Additional limitations include uneven data availability and challenges in comparing results across studies, which frequently differ in temporal scope, geographical context, and national energy system conditions. Data from real production facilities on cogeneration efficiency under variable load conditions remain limited. Additional empirical gaps include biogas upgrading energy use, biomethane leakage rates, heat losses, and dynamic temperature behaviour in district heating networks. These parameters are often modelled rather than measured, reducing result reliability and constraining cross-study comparability. A more unified evaluation framework could be established through standardized reporting boundaries, harmonized life-cycle assumptions, and consistent techno-economic indicators such as efficiency ratios, fuel input–output margins, and emission factors. Such standardization would enable more accurate comparison between district heating concepts and improve the long-term consistency and interpretability of modelling results.

Future work could incorporate dynamic pricing, biogenic carbon capture and utilization technologies, and expanded multi-sector coupling to further optimize renewable district heating systems. It may also include harmonized life-cycle assessments across system scales, enhanced dynamic performance modelling reflecting fluctuating renewable resource availability, and long-term assessments of infrastructure investment pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R. and D.B.; Methodology, A.A. and D.B.; Validation, D.B.; Formal analysis, K.B.; Resources, K.B. and D.B.; Data curation, D.B.; Writing—original draft, A.A.; Writing—review & editing, A.A., L.R. and C.R.; Visualization, A.A.; Supervision, L.R., C.R. and D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IEA (International Energy Agency). Special Section: Biogas and Biomethane. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2023/special-section-biogas-and-biomethane (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Biogas Production and Applications in the Sustainable Energy Transition. J. Energy 2022, 2022, 8750221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Ceci, P.; Cafaro, C.; Corazzi, G.; Avino, P. Production of Biogas and Biomethane as Renewable Energy Sources: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balode, L.; Zlaugotne, B.; Gravelsins, A.; Svedovs, O.; Pakere, I.; Kirsanovs, V.; Blumberga, D. Carbon Neutrality in Municipalities: Balancing Individual and District Heating Renewable Energy Solutions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBA (European Biogas Association). Statistical Report 2023 Tracking Biogas and Biomethane Deployment Across Europe; EBA: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Thrän, D.; Deprie, K.; Dotzauer, M.; Kornatz, P.; Nelles, M.; Radtke, K.S.; Schindler, H. The potential contribution of biogas to the security of gas supply in Germany. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Biogas Association. European Biomethane Capacity Hits 7 bcm—Stronger Policy Support Needed to Sustain Momentum. Available online: https://www.europeanbiogas.eu/news/european-biomethane-capacity-hits-7-bcm-stronger-policy-support-needed-to-sustain-momentum/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- European Commssion. Commission Approves €1.5 Billion French State Aid Scheme to Support Sustainable Biomethane Production to Foster the Transition to a Net-Zero Economy. July 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3986 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Biomethane Industrial Partnership. European Biomethane Price Benchmarking Report—Insights Into the Current Cost of Biomethane Production from Real Industry Data. Available online: https://bip-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/BIP_TF4-study_Full-slidedeck_Oct2023.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Schwarz, M.B.; Veyron, M.; Clausse, M. Impact of Flexibility Implementation on the Control of a Solar District Heating System. Solar 2023, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyt, R.W.; Lie, F.B.; Wilderom, C.P.M. The origins of SWOT analysis. Long Range Plann. 2023, 56, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, N.; Yang, T. Wisdom of crowds: SWOT analysis based on hybrid text mining methods using online reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 171, 114378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Multi-objective optimization strategy for regional multi-energy systems integrated with medium-high temperature solar thermal technology. Energy 2024, 300, 131545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ren, H.; Zhou, W. Review of multi-objective optimization in long-term energy system models. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2023, 6, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egieya, J.M.; Čuček, L.; Zirngast, K.; Isafiade, A.J.; Kravanja, Z. Optimization of biogas supply networks considering multiple objectives and auction trading prices of electricity. BMC Chem. Eng. 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, M.; Karasu, A.; Kriegel, M. Methodology to compare and optimize district heating and decentralized heat supply for energy transformation on a municipality level. Energy 2023, 282, 128987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, R.P.; Fink, J.; de Wit, J.B.; Smit, G.J.M. Upscaling a district heating system based on biogas cogeneration and heat pumps. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2015, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindroos, T.J.; Mäki, E.; Koponen, K.; Hannula, I.; Kiviluoma, J.; Raitila, J. Replacing fossil fuels with bioenergy in district heating—Comparison of technology options. Energy 2021, 231, 1207990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianides, D.; Bagaki, D.A.; Timmers, R.A.; Zrimec, M.B.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Angelidaki, I.; Kougias, P.; Zampieri, G.; Kamergi, N.; Napoli, A.; et al. Biogenic CO2 Emissions in the EU Biofuel and Bioenergy Sector: Mapping Sources, Regional Trends, and Pathways for Capture and Utilisation. Energies 2025, 18, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrot-Paw, M.; Tapczewski, J. Waste to Energy: Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Microalgal Biomass and Bakery Waste. Energies 2025, 18, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirouti, M.; Bagdanavicius, A.; Ekanayake, J.; Wu, J.; Jenkins, N. Energy consumption and economic analyses of a district heating network. Energy 2013, 57, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Lahdelma, R. Genetic optimization of multi-plant heat production in district heating networks. Appl. Energy 2015, 159, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvaj, B.; Evins, R.; Carmeliet, J. Optimising urban energy systems: Simultaneous system sizing, operation and district heating network layout. Energy 2016, 116, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesterlund, M.; Toffolo, A.; Dahl, J. Optimization of multi-source complex district heating network, a case study. Energy 2017, 126, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriqi, A.; Pinheiro, A.N.; Sordo-Ward, A.; Garrote, L. Flow regime aspects in determining environmental flows and maximising energy production at run-of-river hydropower plants. Appl. Energy 2019, 256, 113980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novosel, T.; Feijoo, F.; Duić, N.; Domac, J. Impact of district heating and cooling on the potential for the integration of variable renewable energy sources in mild and Mediterranean climates. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 272, 116374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Li, J.; Fu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S. New configurations of district heating and cooling system based on absorption and compression chillers driven by waste heat of flue gas from coke ovens. Energy 2020, 193, 116707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chow, D.; Kuckelkorn, J.M. Evaluation and optimization of district energy network performance: Present and future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, S.; Cozzini, M.; D’Antoni, M.; Baratieri, M.; Fedrizzi, R. 5th generation district heating and cooling systems: A review of existing cases in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Duic, N.; Østergaard, P.A.; Mathiesen, B.V. Future district heating systems and technologies: On the role of smart energy systems and 4th generation district heating. Energy 2018, 165, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesten, S.; Ivens, W.; Dekker, S.C.; Eijdems, H. 5th generation district heating and cooling systems as a solution for renewable urban thermal energy supply. Adv. Geosci. 2019, 49, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegazzo, D.; Lombardo, G.; Bobbo, S.; De Carli, M.; Fedele, L. State of the Art, Perspective and Obstacles of Ground-Source Heat Pump Technology in the European Building Sector: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünning, F.; Wetter, M.; Fuchs, M.; Müller, D. Bidirectional low temperature district energy systems with agent-based control: Performance comparison and operation optimization. Appl. Energy 2018, 209, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.