Abstract

The article presents an extended methodology for calculating the LENI energy efficiency index for building lighting, taking into account an additional reactive power component—LENIQ. The proposed methodology takes into account the influence of the power factor (cos φ), the nature of the receivers, and the presence of constant lighting intensity (CTE) systems. Based on the analysis of two public buildings (schools)—one without a photovoltaic installation and the other equipped with a PV system—it was shown that reactive power can be a significant component of the energy balance. For the facility without PV, a value of LENIQ = 58.4 kvarh/m2·year was obtained, while for the facility with PV—4.75 kvarh/m2·year, which indicates a more than tenfold reduction in reactive energy thanks to the use of automation and renewable energy sources. A comparison with model values for different cos φ enabled an additional assessment of the efficiency of lighting installations. The aim of this study is to develop an extended methodology of the LENI indicator by introducing a reactive power component LENIQ, enabling a comprehensive assessment of lighting energy efficiency.

1. Introduction

Lighting is one of the key aspects of energy efficiency in sustainable building design and operation. Requirements for the energy performance of lighting are set out in Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1194/2012 of 12 December 2012 [1], establishing ecodesign requirements for directional lamps, LED lamps, and related equipment.

The coefficient that determines the energy efficiency of a building in terms of lighting is the LENI (Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator) coefficient, which is defined by the PN-EN 15193:2010 standard “Energy performance of buildings—Energy requirements for lighting” [2]. This indicator determines the annual active lighting power consumption per unit of area and is often used for certification purposes [3,4,5,6]. This indicator refers only to the active power of lighting, ignoring the reactive power. In most lighting installations, reactive power constitutes a significant part of the load. This problem is becoming increasingly serious due to the increased use of modern LED systems and the introduction of voltage control systems such as CTE (Constant Illuminance Control), i.e., systems that maintain a constant level of illuminance [7]. CTE systems automatically adjust the power of luminaires depending on the amount of daylight or the degradation of light sources, which leads to a reduction in active energy consumption [8,9,10]. At the same time, however, they cause a decrease in the power factor (cos φ) and thus an increase in the share of reactive power in the total energy balance [5,11].

In recent years, many public buildings, especially schools and hospitals, have begun to show significant reactive power values on their electricity bills [4,5,12]. New tariffs, especially for consumers with connection capacities above 40 kW, where the cost of reactive energy is up to three times higher than before, further increase the significance of this phenomenon. Despite this, the technical literature still lacks coverage of reactive power in lighting energy efficiency analyses, especially in facilities equipped with CTE systems and photovoltaic (PV) installations. This creates a research gap in the comprehensive energy assessment of lighting systems, which should take into account both active and reactive power.

The importance of lighting systems in the overall energy balance of buildings is increasingly emphasized. Research results indicate that energy audits of buildings should cover not only heating systems and building envelopes, but also electrical installations, which can be a significant component of energy consumption in public buildings [7,13]. Modernizations carried out in such facilities, including thermal modernization, replacement of window frames, use of renewable energy sources, and modernization of lighting, allow for a significant reduction in energy demand, reaching up to 70–80% [14,15]. The modernization of lighting systems plays a particularly important role in improving energy efficiency, including the replacement of traditional light sources with LED technology and the introduction of control automation, which can reduce electricity consumption by more than 60% and significantly reduce CO2 emissions [16]. The results of these analyses indicate that the assessment of lighting energy efficiency should take into account not only active energy, but also energy quality parameters such as reactive power and power factor, which in modern LED installations can significantly affect the overall energy balance of a building.

The aim of this paper is to propose an extension of the LENI methodology with a component corresponding to passive energy, LENIQ. The article presents the theoretical basis for the new approach, the method for determining the LENIQ index, and case studies involving educational buildings with and without PV installations. The proposed index is intended to enable a more comprehensive and realistic assessment of the energy efficiency of lighting, which may contribute to improving the quality of design and energy management in modern buildings.

Sustainable development and energy efficiency are key aspects of contemporary architecture and construction engineering. In this context, international certification systems that help assess and confirm the environmental friendliness and energy efficiency of projects are becoming increasingly popular. Among the most recognizable are BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) and LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). The luxonled.eu website analyzes a comparison of these systems, particularly in the context of LED lighting certification [17]. Both BREEAM and LEED aim to evaluate and promote sustainable solutions in construction. While LEED, developed in the US, focuses on a wide range of environmental aspects, from energy to water, BREEAM, a British system, emphasizes a comprehensive environmental and economic assessment of buildings. An important part of the study is the role of LED lighting, which plays a key role in achieving high scores in both certification systems. The right choice and certification of LED systems not only affects energy efficiency but also helps you achieve higher certification levels. Both systems reward solutions that help save energy and reduce CO2 emissions. However, LEED and BREEAM differ in their approach to scoring and assessment categories. LEED, for example, attaches great importance to aspects such as technological innovation and indoor environmental quality, while BREEAM focuses more on the stages of a building’s life cycle and a comprehensive environmental analysis. Well-designed and certified LED lighting can significantly increase the chances of high scores in both systems. LED certifications have a significant impact on scoring in categories related to energy efficiency, innovation, and indoor environmental quality. A comparison of the BREEAM and LEED systems shows that, although both are deeply rooted in the philosophy of sustainability, they differ in the details of their assessment and certification strategies. In the context of LED lighting, the choice of the appropriate certification system may depend on the specifics of the project and the target requirements. Certainly, LED certification is becoming an increasingly important tool on the road to green and energy-efficient buildings [17].

2. Theoretical Foundations

The LENI (Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator) has been defined in the PN-EN 15193:2010 standard “Energy performance of buildings—Energy requirements for lighting” as a measure of the annual electricity consumption of a lighting system in relation to the usable floor area of a building [3,4]. The LENI indicator is used in LEED reports and certification, but not as a mandatory, direct requirement, but as one of the recognized methodologies within specific credits (points), mainly those related to energy efficiency optimization. This is a key credit in the Energy and Atmosphere (EA) category, which allows up to 20 points to be earned (in LEED v4.1 BD+C). To earn these points, the project must demonstrate a percentage improvement in the energy efficiency of the entire building compared to a baseline building defined in ASHRAE 90.1 [17]. The LENI index, defined in the European standard EN 15193, is a recognized method for calculating the energy consumed by the lighting system for both the reference building and the designed building.

The value of this indicator is determined according to the following formula:

where

E—annual total annual electricity consumption for lighting,

A—usable floor space of the analyzed zone or building.

In a situation where a facility has a renewable energy source installed, it is reasonable to analyze electricity consumption for lighting purposes, taking into account seasonal, monthly, or daily energy production from RES. The result will be the inclusion in the description of the annual LENIP,annual indicator, an aggregation of the energy effect spread over a selected period of time:

where

- -

- LENIi is an indicator analyzed over a short period of time,

- -

- n is the number of periods analyzed (n = 12 in monthly analysis, n-365 in daily analysis).

This standard also takes into account a number of correction factors F, which are intended to reflect the impact of operational factors and lighting automation systems on the LENIP value. The correction factors F include:

FO—occupancy factor,

FD—daylight factor,

FC—constant illuminance control (CTE) factor,

FT—system usage time factor.

In accordance with the use of these factors, the formula describing the total annual electricity consumption is expressed as follows:

where

- -

- Pn is the rated power of the installed lighting,

- -

- tn is the average time of its use during the year.

2.1. Impact of the Power Factor on Energy Consumption

The power factor cos φ determines the ratio of active power to apparent power S according to the formula:

In lighting, this factor describes what proportion of the power drawn from the grid is not converted by the receivers into active power but is converted into reactive power Q, which is related to the capacitive and inductive parameters of the receivers. The relationship between these quantities is described by the following equations [18,19,20]:

and

In modern LED lighting fixtures, this factor can vary greatly (from 0.2 to 0.97), which significantly affects the increase in reactive power in the total energy balance of a building, resulting in higher electricity costs [10]. CTEs used to change the intensity of lighting can have a particular impact on the value of this factor.

2.2. Extension with the LENIQ Index

In order to take reactive power into account in the analysis of a building’s energy efficiency, it is necessary to introduce a new LENIQ indicator analogous to the LENIP indicator but relating to the energy efficiency of the reactive power of lighting receivers. It is proposed that this indicator be described by the following formula:

where

- -

- Qannual total annual reactive energy consumed for lighting,

- -

- A usable area of the analyzed zone or building.

This value can be calculated based on active power and power factor [19]:

For a more comprehensive energy assessment, it is also proposed to introduce a combined indicator:

where k is a weighting factor reflecting the ratio of reactive energy costs to active energy costs (e.g., k = 0.33 in the case of three times higher reactive power charges, which is currently the case in Poland).

To determine the daily and monthly values of the LENIQ coefficient, the value of the LENItotal coefficient should be divided by 365 days and 12 months, respectively:

This approach allows for the comparison of different lighting system scenarios, both in terms of energy efficiency and economic efficiency.

Recent studies provide a strong empirical foundation for the inclusion of reactive power in lighting energy assessments and directly support the conceptual development of the LENIQ indicator proposed in this work. Yoomak et al. [21] highlighted that LED luminaires, despite their high luminous efficacy, generate substantially higher levels of harmonic distortion and exhibit lower and more unstable power factors compared to traditional HPS luminaires in roadway lighting systems. Their results clearly demonstrate that modern LED lighting alters the reactive power profile of electrical installations, thereby reinforcing the need for energy performance indicators that consider not only active but also reactive energy flows. Similarly, Gil-de-Castro et al. [22] showed that LED drivers introduce distinct harmonic signatures and non-linear behaviors that significantly influence reactive power flows within street-lighting networks. Their research emphasizes that replacing older luminaires with LED systems changes not only active energy consumption but also the characteristics of reactive energy demand—a factor not captured by the standard LENI metric. This finding directly supports the rationale for extending LENI with a reactive power component. Uddin et al. [23] investigated low-wattage LED lamps and reported pronounced current harmonics, voltage sensitivity, and considerable variations in power factor under typical operating conditions. These behaviors amplify reactive power consumption and degrade power quality at the installation level. Such results indicate that in real-world usage, especially in buildings with large numbers of LED fixtures, reactive energy may constitute a substantial and variable share of total electricity demand—again demonstrating a gap in existing energy assessment methodologies. Sikora et al. [24] further contributed by developing a measurement-based model of LED luminaires that accounts for changes in electrical behavior under different dimming levels. Their study reveals that dimming a feature increasingly used in modern CTE systems can significantly reduce the power factor, thereby increasing reactive energy consumption even when active energy demand decreases. This observation is highly relevant to LENIQ, as it confirms that lighting control systems may unintentionally exacerbate reactive power flows, making a reactive component essential for accurate energy evaluation. Finally, Skarżyński and Wiśniewski [25] demonstrated that although modern LED lamps can achieve high luminous efficacy, this often occurs at the cost of a lower power factor and increased reactive energy consumption. They also emphasize that reactive energy costs are becoming an important part of operating expenses in many facilities equipped with LED technology. Their work underlines the financial significance of reactive energy, further supporting the inclusion of the LENIQ indicator as a practical tool for assessing not only technical but also economic performance of lighting systems.

Taken together, these five studies reveal a consistent and critical theme: modern LED lighting systems, especially when combined with advanced control strategies, exhibit complex power quality behaviors that substantially influence reactive energy demand. This body of literature clearly exposes a methodological gap in existing lighting energy metrics, which focus solely on active energy consumption. The findings therefore provide strong justification for the development of the LENIQ indicator, which fills this gap by enabling a comprehensive, realistic, and economically meaningful assessment of lighting system performance in contemporary buildings.

3. Research Methodology

Educational facilities are currently characterized by the frequent use of LED sources in lighting and are increasingly equipped with photovoltaic installations to reduce electricity costs. The use of LED lighting significantly increases the reactive power demand of such facilities. This behavior makes it necessary to consider electricity demand not only in terms of active power but also reactive power. The aim of this paper is to propose an extension of the LENI methodology with a component corresponding to passive energy, LENIQ. This analysis was carried out for two educational buildings, one without a photovoltaic installation and the other with such an installation.

The requirements for lighting in schools are detailed in the PN-EN 12464-1:2022-01 standard entitled “Light and lighting—Lighting of workplaces—Part 1: Indoor workplaces” [26]. The lighting intensity values that individual rooms in the school should meet are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Lighting requirements according to PN-EN 12464-1:2022-01. Source: EN 12464-1:2022.

In order to analyze educational facilities and assess their energy efficiency, it was decided to convert the LENIP coefficient from annual values to monthly values. This allows for a realistic assessment of a building’s energy efficiency based on its operating characteristics—vacancies during the holiday season. The converted LENIP values are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Seasonal theoretical values of the LENI index according to PN-EN 15193-2010. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on PN-EN 15193:2010.

Then, based on three different representative cos φ values (0.9; 0.75; 0.5), the following coefficient values were adopted because: 0.9 is typical for lighting fixtures powered by electronic converters, e.g., LEDs, T5 fluorescent lamps, 0.75 is characteristic of LED replacements, e.g., LED fluorescent lamps, and 0.5 characterizes LED replacements for conventional light sources with E14, E27, or other inferior quality bases used, for example, in basic modernization and maintenance of luminaires by replacing light sources. Derived values of the LENIQ coefficient have been determined, which schools should achieve when using light sources with such power coefficients. These results are presented in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. It should also be remembered that the use of light flux regulation causes a downward change in cos φ, because according to the literature [11], LED controllers with a dimming function have a variable cos φ, so the values for 100% power supply are assigned a rated cos φ, but after regulation, cos φ drops by up to 30% [27,28].

Table 3.

Seasonal, theoretical values of the LENI index according to PN-EN 15193-2010, taking into account the actual cos φ = 0.9. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on PN-EN 15193:2010.

Table 4.

Seasonal, theoretical values of the LENI index according to PN-EN 15193-2010, taking into account the actual cos φ = 0.75. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on PN-EN 15193:2010.

Table 5.

Seasonal, theoretical values of the LENI index according to PN-EN 15193-2010, taking into account the actual cos φ = 0.5. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on PN-EN 15193:2010.

The analysis covers a school with an area of 1000 m2, divided into three basic parts: 700 m2 of classrooms, 200 m2 of corridors, and 100 m2 of bathrooms. Assuming that classrooms are used for 6 h a day each, and the remaining rooms for 8 h a day, and that the lighting intensity requirements are met. An example of the energy load in such a school is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Project assumptions. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The total energy consumption in such an educational building can amount to 229 kWh/day, with lighting accounting for 79.8 kWh/day. This represents 34.85% of the building’s total daily electricity demand. In the further analysis, a percentage of 35% of the total electricity consumed by schools for lighting was assumed, in accordance with the adopted calculation model for the selected school building.

In accordance with the requirements of PN-EN 61000-3-2:2019-04 (EN 61000-3-2:2018) “Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC)—Part 3-2: Limits—Limits for harmonic current emissions (equipment input current ≤ 16 A phase current),” lighting devices are classified as Class C [29]. This standard defines the minimum acceptable power factor (PF) values depending on the rated power of the light source or luminaire. According to Annex A of this standard: for devices with a power p < 5 W, no PF requirements are specified; for the range 5 W ≤ p < 25 W, the power factor should be no less than 0.4; for 25 W ≤ p < 75 W, a PF value of ≥0.5 is required; and for devices with a power of p ≥ 75 W, the power factor should be at least 0.9 [30,31]. These requirements are intended to reduce current distortion and improve the quality of electricity in power supply networks, thereby ensuring the electromagnetic compatibility of lighting devices with other energy consumers. In further considerations and in the developed formula, the LENIQ factor was divided into components corresponding to the division of the factor based on the power of the luminaires.

4. Estimated Calculation of LENIQ at School

4.1. School Without a Photovoltaic Installation

Daily energy consumption values provided with the operating system for the year 2024 during standard school operations. These data are derived from a yearly lighting usage profile, while seasonal analysis was conducted following research. Monitoring covered the full calendar year 2024 (1 January–31 December), including both operational and non-operational periods (weekends, holidays, summer break). The LENIQ annual value is therefore calculated using real measurement data reflecting seasonal reductions in lighting usage during school closure periods. Since educational buildings exhibit strong seasonal variability, periods of reduced occupancy were included directly through the measured daily values from the full 2024 dataset. No artificial assumptions were applied thus, seasonal effects are inherently reflected in the annual LENIQ estimates.

School building 1 (SB1) without a photovoltaic installation has an area of approx. 12,000 m2. In the building, 2/3 of the area is occupied by classrooms, 2/9 by corridors, and 1/9 by toilets. The estimated values of the F coefficients are presented in Table 7. The study also assumes the following power distribution: classrooms E, corridors (0.5E), bathrooms (1/3E) and, accordingly cos φ: classrooms (cos φ > 0.9), corridors (cos φ 0.5–0.9), bathrooms (cos φ < 0.5).

Table 7.

Indicators for determining LENI used in the calculation model. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

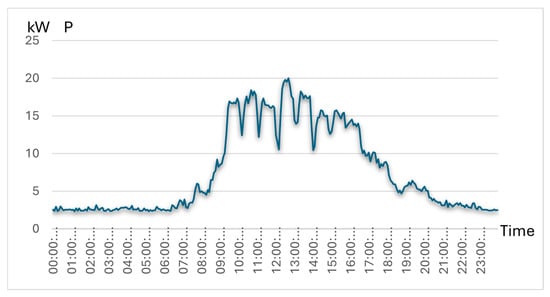

In the first of the schools studied, the average daily power consumption on working days is 2390 kWh/day. According to earlier assumptions, 35% of the school’s daily electricity demand is for lighting. Therefore, it is assumed that E = 836.5 kWh/day is consumed by lighting fixtures. The average active power consumption in BS1 is shown in Figure 1. The maximum value reaches 20 kW, with a noticeable increase in power demand around 8 a.m. when the school starts classes, and visible drops in power consumption every 45 min during the day in line with the school’s daily rhythm and the switching off of lighting in classrooms during breaks.

Figure 1.

Power demand curve in the SB1 school building calculation model. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

It follows that lighting in classrooms accounts for electricity consumption of 457.1 kWh/day, corridors for 227.55 kWh/day, and toilets for 151.85 kWh/day. Taking into account the previously calculated F coefficients, power consumption can be estimated at the levels presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Ind Results of calculations of electricity demand for lighting purposes in building SB1. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

According to the proposed model, the LENIQ coefficient value at the school will be at the level of:

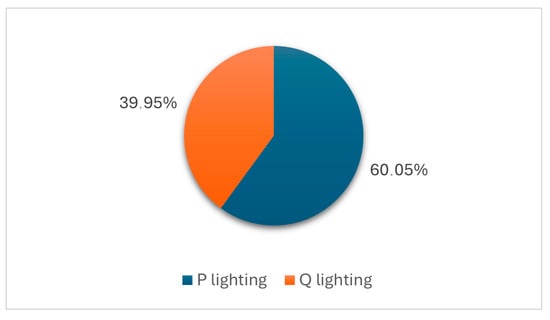

Assuming 365 days a year and 12 months, the annual LENIQ in the school under study will be 58.4 kvar/m2, and the monthly LENIQ will be 4.86 kvar/m2. LED luminaires and all electronic luminaires are capacitive in nature, so Q takes negative values, while if they are fluorescent luminaires powered by inductive ballasts, they are inductive in nature and Q takes positive values. Figure 2 illustrates the share of active and reactive power consumption for lighting in SB1.

Figure 2.

Percentage demand for active and reactive power consumed by lighting in SB1. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

4.2. School with a Photovoltaic Installation

School building 2 (SB2), with a 50 kW photovoltaic installation, has an area of approx. 9000 m2. The building has the same floor space distribution as the previous school, identical F coefficients, and the same cos φ values corresponding to the spaces.

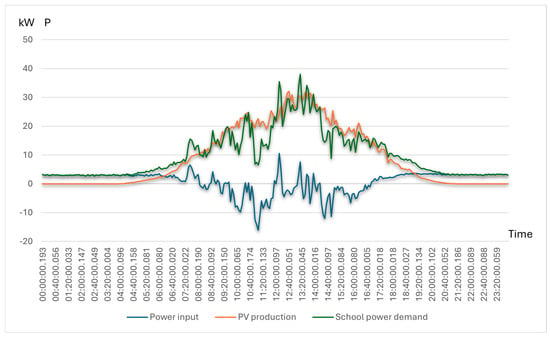

In the second of the schools studied, the average daily power consumption on working days is 223.02 kWh/day. It is assumed that E = 78.06 kWh/day is consumed by lighting fixtures. Figure 3 shows the daily power demand, production from the photovoltaic installation, and the resulting power consumption in school 2. Negative active power values are noticeable, which means that the photovoltaic installation produces more electricity than is needed, and the excess energy goes to the grid. There are also noticeable spikes in active power demand, which may be caused by changes in weather conditions, e.g., cloud cover, when the photovoltaic installation does not produce electricity.

Figure 3.

Power demand curve in the SB2 school building calculation model. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

It follows that classroom lighting accounts for electricity consumption of 42.56 kWh/day, corridors for 21.30 kWh/day, and toilets for 14.20 kWh/day. Taking into account the previously calculated F coefficients, power consumption can be estimated at the levels presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Ind Results of calculations of electricity demand for lighting purposes in building SB2. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

According to the proposed model, the LENIQ coefficient value at the school will be:

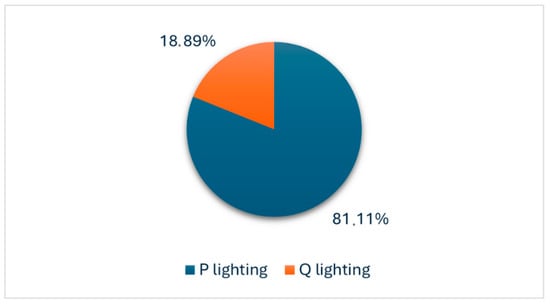

The annual LENIQ coefficient will be 4.75 kvar/m2, and the monthly coefficient will be 0.4 kvar/m2. Figure 4 presents the percentage distribution of active and reactive power consumption for lighting in SB2.

Figure 4.

Percentage demand for active and reactive power consumed by lighting in BS2. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Cost analysis based on the obtained LENIQ values further highlights the practical implications of reactive energy consumption in educational buildings. The difference between the LENIQ coefficients of SB1 and SB2 (58.4 vs. 4.75 kvarh/m2·year) results in an annual reduction of approximately 643,800 kvarh of reactive energy. Under current Polish tariff conditions, where reactive energy charges are approximately 0.40 EUR/kvarh, this corresponds to an annual cost of about 279,900 EUR for SB1 and about 22,800 EUR for SB2. Therefore, the lower LENIQ value of SB2 translates into an estimated annual saving of approximately 257,000 EUR. These results clearly show that reducing reactive energy demand provides substantial financial benefits and further reinforces the practical relevance of the LENIQ indicator for building owners and facility managers.

5. Conclusions

Until now, the LENI indicator has only referred to active energy. If regulations concerning consumers paying for reactive energy change, it will be necessary to consider which consumers consume the most reactive electricity. Lighting is one of the biggest loads on an installation. The introduction of the LENIQ component, representing reactive energy consumption, allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the energy efficiency of lighting systems in buildings. This indicator can be used to identify reactive power compensation needs in lighting systems, which is very important in the context of building energy efficiency.

In typical LED lighting installations, the power factor (cos φ) can range from 0.5 to 0.9. A decrease in cos φ leads to a significant increase in reactive power and thus to higher operating costs. For large schools, this can mean an increase in total energy costs of up to 20–30%. Schools already show reactive power on their bills, and in the future, they will pay for its consumption. Currently, reactive electricity costs are three times higher than active energy costs.

Based on the results illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 4, the school equipped with a photovoltaic installation exhibits a substantially lower share of reactive power in the total energy balance. This confirms the effectiveness of automation and PV systems in reducing reactive energy demand. The difference in LENIQ values between SB1 and SB2 (58.4 vs. 4.75 kvarh/m2·year) corresponds to an annual reduction of approximately 643,800 kvarh of reactive energy, which translates into an estimated cost saving of about 257,000 EUR per year under current Polish tariff conditions.

The comparison shows that the share of reactive energy in the total energy balance (S) decreases significantly in the case of facilities with PV installations and a higher power factor cos φ. The introduction of photovoltaics promotes local self-consumption and power profile stabilization, thus reducing reactive power flows in the school’s internal network. At the same time, the proper selection of the power of LED sources and computers to the power of the PV installation allows for the optimization of active energy use and reduces reactive power charges.

Modernizing lighting without analyzing the reactive power of new lighting fixtures may pose a significant problem in the future. An apparent reduction in active power consumption may result in high reactive power charges, so when modernizing a lighting installation, it is necessary to check the cos φ of the lighting fixtures.

The research conducted for both schools shows that the school with a PV installation has a significantly lower LENIQ coefficient. Both schools had manual lighting control, so when analyzing the daily coefficient values obtained, it can be seen that the daily LENIQ coefficient value in the school with a photovoltaic installation meets all the daily values resulting from LENIP calculations for different cos φ variants. The school without a photovoltaic installation meets these requirements only for the highest cos φ value, and for basic and good lighting classes with a cos φ = 0.75 coefficient. On an annual and monthly basis, the school without a photovoltaic installation meets the LENIQ coefficient values only at cos φ = 0.9 and cos φ = 0.75. It follows that it is necessary to pay special attention to the value of the cos φ coefficient when purchasing light sources and lighting fixtures.

The developed LENIQ methodology is consistent with the literature and tabular values, confirming its usefulness for assessing the overall energy efficiency of lighting systems in buildings with modern LED sources and CTE automation.

Further research could address the seasonality of these coefficients, taking into account the annual impact of daylight on the demand for artificial lighting in buildings through year-round observation of buildings. Further research is also planned to analyze the developed indicator in other public facilities.

In the context of energy certification systems such as LEED and BREEAM, it is very important to take passive energy consumption into account. The assessment of a building’s energy efficiency in these systems is not limited to active energy, but also includes aspects of power quality and power optimization. Increasingly, energy bills include items related to capacitive reactive energy, typical for installations with LED luminaires, which confirms the need to monitor and compensate for reactive power already at the design and modernization stage of lighting. The inclusion of the LENIQ indicator in the assessment of lighting efficiency can therefore complement the requirements of LEED certification, supporting a more comprehensive energy analysis of buildings and contributing to the reduction in operating costs resulting from excess reactive power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and H.S.; methodology, M.Z.; software, H.S.; validation, H.S., M.A.S. and M.Z.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, H.S.; resources, M.A.S.; data curation, M.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, M.Z.; visualization, H.S.; supervision, M.Z.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S., M.A.S. and M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was carried out as part of thesis no. WZ/WE-IA/3/2023 and no. WZ/WIZ-INZ/4/2025 at the Białystok University of Technology and financed from a research subsidy provided by the minister responsible for science.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LENI | Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator |

| LENIQ | Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator for reactive power |

| LENIP | Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator for active power |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| CTE | Constant Illuminance Control |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| PF | Power Factor |

| SB1 | School Building 1 |

| SB2 | School Building 2 |

References

- Rozporządzenie Komisji (UE) Nr 1194/2012 z Dnia 12 Grudnia 2012 r. w Sprawie Wykonania Dyrektywy 2009/125/WE Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady w Odniesieniu Do Wymogów Dotyczących Ekoprojektu Dla Lamp Kierunkowych, Lamp z Diodami Elektroluminescencyjnymi i Powiązanego Wyposażenia. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32012R1194 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- PN-EN 15193:2010; Charakterystyka Energetyczna Budynków—Wymagania Energetyczne Dotyczące Oświetlenia. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2025.

- Akimov, L.; De Michele, G.; Filippi Oberegger, U.; Badenko, V.; Mainini, A.G. Evaluation of EN 15193-1 on energy requirements for artificial lighting against radiance-based DAYSIM. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 40, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompei, L.; Blaso, L.; Fumagalli, S.; Bisegna, F. The impact of key parameters on the energy requirements for artificial lighting in Italian buildings based on standard EN 15193-1:2017. Energy Build. 2022, 263, 112025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, S.; Blaso, L.; Testa, A.; Ruggieri, G.; Ransen, O. EN 15193, lighting energy numeric indicator: LENICALC calculations in a retirement home case study. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Istanbul, Turkey, 27–28 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparovsky, D.; Erkin, E.; Onaygil, S.; Smola, A. A Critical Analysis of the Methodology for Calculation of the Lighting Energy Numerical Indicator (LENI). In Light in Engineering, Architecture and the Environment; Wit Press: Southampton, UK, 2011; p. 184. ISBN 978-1-84564-550-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pracki, P.; Komorzycka, P. Analysis of the general index of modelling in interior lighting. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2024, 72, e149233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, S.; Kotulski, L.; Lerch, T.; Rad, M.; Sędziwy, A.; Wojnicki, I. Application of reactive power compensation algorithm for large-scale street lighting. J. Comput. Sci. 2021, 51, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. DOE; PNNL. CALiPER Study 3.1: Retail Lamps Study 3.1—Dimming, Flicker, and Power Factor; U.S. DOE: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wlaś, M.; Galla, S. The influence of LED lighting sources on the nature of power factor. Energies 2018, 11, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkowski, M.; Popławski, T.; Zajkowski, M.; Sołjan, Z. The impact of limiting reactive power flows on active power losses in lighting installations. Energies 2024, 17, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompei, L.; Mattoni, B.; Bisegna, F.; Blaso, L.; Fumagalli, S. Evaluation of the energy consumption of an educational building, based on the UNI EN 15193–1:2017, varying different lighting control systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2020 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 9–12 June 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Siwek, K. Energy audit of the residential building. J. Mech. Energy Eng. 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwińska-Małajowicz, A.; Pyrek, R.; Szczotka, K.; Szymiczek, J.; Piecuch, T. Improving the energy efficiency of public utility buildings in Poland through thermomodernization and renewable energy sources—A case study. Energies 2023, 16, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, D.; Jovanović, V.; Ignjatović, M.; Marchwiński, J.; Kopyłow, O.; Milošević, V. Improving energy efficiency of school buildings: A case study of thermal insulation and window replacement using cost-benefit analysis and energy simulations. Energies 2024, 17, 6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.; Saad, M. Building energy use: Modeling and analysis of lighting systems—A case study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BREEAM and LEED Certificates: Comparison of the Most Common Energy Certification Systems for LED Lighting. Available online: https://luxonled.eu/knowledge/breeam-and-leed-certificates-comparison-of-the-most-common-energy-certification-systems-for-led-lighting/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Phannil, N.; Jettanasen, C.; Ngaopitakkul, A. Harmonics and reduction of energy consumption in lighting systems by using LED lamps. Energies 2018, 11, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzelka, Z. Jakość Dostaw Energii Elektrycznej; Wydawnictwo AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki, L. Moce w Obwodach Elektrycznych z Niesinusoidalnymi Przebiegami Prądów i Napięć; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yoomak, S.; Jettanasen, C.; Ngaopitakkul, A.; Bunjongjit, S.; Leelajindakrairerk, M. Comparative Study of Lighting Quality and Power Quality for LED and HPS Luminaires in a Roadway Lighting System. Energy Build. 2018, 159, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-de-Castro, A.; Moreno-Muñoz, A.; Larsson, A.; González de la Rosa, J.J.; Bollen, M.H.J. LED Street Lighting: A Power Quality Comparison among Street Light Technologies. Light. Res. Technol. 2013, 45, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Shareef, H.; Mohamed, A. Power Quality Performance of Energy-Efficient Low-Wattage LED Lamps. Measurement 2013, 46, 3783–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, R.; Markiewicz, P.; Rózga, P. An Accurate Model of LED Luminaire Using Measurement Results for Estimation of Electrical Parameters Based on the Multivariable Regression Method. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 2022, 29, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarżyński, K.; Wiśniewski, A. The Reflections on Energy Costs and Efficacy Problems of Modern LED Lamps. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 4926–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12464-1:2022-01; Light and Lighting—Lighting of Workplaces—Part 1: Indoor Workplaces. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Drgoňa, P.; Ďurana, P.; Betko, T. Research of the negative influence of dimmed LED luminaires in context of smart installations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem Atılgan, L.; Bayram Kara, D.; Üstün, Ö. An analysis of LED driver performance using TRIAC and DC link dimming. In Proceedings of the 29th CIE SESSION, Washington, DC, USA, 14–22 June 2019; p. 1347. [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN 61000-3-2:2019-04 (EN 61000-3-2:2018); Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC)—Part 3-2: Limits—Limits for Harmonic Current Emissions (Equipment Input Current ≤ 16 A Phase Current). PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2025.

- R Rozporządzenie Komisji (WE) Nr 244/2009 z dnia 18 Marca 2009 r. w Sprawie Wykonania Dyrektywy 2005/32/WE Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady w Odniesieniu do Wymogów Dotyczących Ekoprojektu Dla Bezkierunkowych Lamp do Użytku Domowego. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02009R0244-20160227&from=RO (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Wantuch, A.; Olesiak, M. Effect of LED lighting on selected quality parameters of electricity. Sensors 2023, 23, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.