1. Introduction

The accelerating global transition toward sustainable energy systems has positioned green hydrogen as a cornerstone in the decarbonization of sectors traditionally reliant on fossil fuels [

1,

2]. Large-scale green hydrogen production relies heavily on the availability of substantial and affordable renewable electricity, given the energy-intensive nature of water electrolysis, making regions endowed with abundant renewable resources (e.g., wind and solar) particularly pivotal for the future hydrogen economy [

3,

4]. Among such regions, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) stands out due to its exceptional solar and wind resources [

5,

6,

7]. While solar energy has long been the centerpiece of renewable development in MENA, offshore wind, particularly in countries like Oman and Egypt, presents an untapped yet promising frontier [

8,

9,

10]. Recent analyses suggest that Egypt and Oman possess substantial offshore wind potential, capable of supporting multi-gigawatt-scale projects [

11,

12,

13]. Their coastal geographies, coupled with favorable wind conditions, present ideal conditions for harnessing offshore wind to drive electrolytic hydrogen production.

Despite these advantages, offshore wind development in the MENA region remains nascent, constrained by high costs, technological and infrastructure challenges, policy gaps, and limitations in offshore resource assessment [

14,

15]. With targeted policy reforms and strategic investment, the region could unlock significant offshore wind potential in the future. Nevertheless, long-term visions are beginning to materialize, particularly in Oman, which has articulated national strategies aimed at becoming a global green hydrogen hub, and in Egypt, which is actively pursuing gigawatt-scale hydrogen projects in the Gulf of Suez.

This study presents a techno-economic assessment of green hydrogen production from offshore wind energy in two representative MENA countries: Oman and Egypt. Using site-specific simulation data, the performance of a 120 MW offshore wind power plant coupled with electrolyzers is evaluated for both locations. To ensure a realistic and scalable representation of offshore wind-powered hydrogen systems in the MENA region, a 120 MW wind farm was selected as the reference capacity for simulation. This size corresponds to the anticipated scale of early commercial offshore projects in emerging markets such as Egypt and Oman, where offshore infrastructure is still under development. The chosen capacity also supports a modular system configuration based on 15 Vestas 8 MW wind turbines, widely adopted in offshore wind projects. This setup facilitates consistent benchmarking of performance metrics while enabling accurate integration with electrolyzer systems. The analysis includes wind resource mapping, annual electricity output, Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE), hydrogen production volumes, and Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH). In addition, seasonal production patterns, capacity factors, and their implications for storage and utilization are investigated.

By comparing two distinct geographies within the same region, this research aims to illuminate the broader viability of offshore wind-to-hydrogen systems across MENA. Ultimately, the findings underscore not only the technical feasibility of such systems but also their potential to contribute meaningfully to national decarbonization goals and regional energy security. The selection of Oman and Egypt as focal points in this study is driven by their strategic positioning within the MENA region and their distinct yet complementary renewable energy profiles (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Figure 1 shows that the Gulf of Suez, highlighted as the highest wind speed classes, emerges as a wind energy hotspot, indicating average wind speeds consistently exceeding 9.85 m/s at 50 m height. The proposed site of the offshore wind power plant is strategically positioned near the convergence of the Red Sea’s northerly wind corridor and the Suez Gulf, where strong and persistent offshore winds are prevalent. This region is one of the most viable zones for high-capacity offshore wind development in the MENA region. From a policy and technical perspective, the site’s proximity to Egypt’s national grid, existing transmission infrastructure, and potential hydrogen export corridors (via the Suez Canal) also enhances its techno-economic feasibility.

Figure 2 presents the wind resource map of Oman at a 50 m height, highlighting spatial variations in mean annual wind speeds. The southern coastal corridor of Oman in Dhofar Governorate, particularly the area near Ash Shuwaymiyyah, emerges as a high-wind zone with average wind speeds consistently reaching 9–10 m/s at 50 m, as indicated by the intense red and violet coloration along the coastline. The proposed offshore wind power site is located near Ash Shuwaymiyyah and benefits from the seasonal monsoon (Khareef) effect, especially between June and September, when strong southerly winds dominate the Arabian Sea coast. These ocean-driven wind patterns make the site uniquely suitable for seasonal surplus green hydrogen production, complementing Egypt’s more uniform annual wind profile.

Importantly, the location provides direct offshore access and proximity to Oman’s developing hydrogen export infrastructure, as outlined in Oman’s Vision 2040. The low population density and relative ease of coastal land access also reduce siting and permitting constraints compared to inland or densely populated regions.

Oman’s commitment to becoming a green hydrogen export hub by 2030, backed by supportive policies and investor interest, makes it an ideal candidate for offshore wind-driven hydrogen production [

16]. Egypt, on the other hand, benefits from established infrastructure, a rapidly expanding renewable energy sector, and high-quality wind resources in the Gulf of Suez. With major energy corridors linking Africa, Europe, and Asia, Egypt is geographically positioned to serve as a key green hydrogen supplier to global markets [

17,

18,

19]. Together, these countries provide a representative comparison of offshore wind-to-hydrogen feasibility in differing policy, resource, and infrastructure contexts within the MENA region.

Figure 1.

Wind atlas of Egypt at 50 m height, illustrating the spatial distribution of average wind speeds and the location of the proposed offshore wind power plant near Gulf of Suez (according to global wind atlas) [

20].

Figure 1.

Wind atlas of Egypt at 50 m height, illustrating the spatial distribution of average wind speeds and the location of the proposed offshore wind power plant near Gulf of Suez (according to global wind atlas) [

20].

Figure 2.

Wind atlas of Oman at 50 m height showing the average annual wind speeds and the proposed offshore wind power site near Ash Shuwaymiyyah (Dhofar Governorate) along the southern Arabian Sea coast (based on Global Wind Atlas data) [

20].

Figure 2.

Wind atlas of Oman at 50 m height showing the average annual wind speeds and the proposed offshore wind power site near Ash Shuwaymiyyah (Dhofar Governorate) along the southern Arabian Sea coast (based on Global Wind Atlas data) [

20].

Offshore wind-powered hydrogen has the potential to become a strategic pillar for strengthening energy security, driving economic diversification, and enabling industrial decarbonization in both Oman and Egypt. To realize this potential, policymakers must give priority to initiating pilot projects, establishing robust certification frameworks, and advancing infrastructure planning, as these measures are essential to de-risk investments and accelerate large-scale deployment. Moreover, coordinated regional strategies between Oman and Egypt could allow the two countries to position themselves as complementary leaders in supplying green hydrogen to both European and Asian markets, thereby enhancing their geopolitical standing and expanding their economic influence in the emerging global hydrogen economy.

Green hydrogen is pivotal for decarbonizing sectors where alternatives are limited, such as heavy industry (steel, cement), long-haul transport, aviation, maritime shipping, and chemical manufacturing [

21,

22,

23]. These sectors are responsible for a significant share of global CO

2 emissions, over 25%, and are now turning to green hydrogen as a feasible path to substantial emissions abatement [

24]. Countries are adopting industrial policies to foster green hydrogen innovation and capture economic opportunities in emerging markets, with global hydrogen demand projected to increase by 700% by 2050 [

22]. MENA countries possess vast solar and wind energy potential, which enables cost-effective production of green hydrogen. Nations such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Oman, UAE, Morocco, and Mauritania are particularly well-positioned to harness these resources for large-scale hydrogen projects [

25,

26]. MENA’s geographical closeness to Europe and Asia makes it strategically advantageous for exporting green hydrogen. The region’s existing infrastructure and its role as a major natural gas exporter further support its potential as a future hydrogen hub [

27,

28]. Egypt is a regional leader with ambitions to capture 5–8% of the global hydrogen market, leveraging its infrastructure and renewable resources to become a major hydrogen player.

The MENA region, including Oman, is recognized for its abundant solar and wind resources, which are crucial for cost-effective green hydrogen production. These countries have been selected for detailed analysis due to their diverse water profiles, hydrogen ambitions, and renewable energy capacities, supporting the notion that the region is well-positioned for export-oriented hydrogen production [

29,

30]. Accordingly, Egypt and Oman were selected as representative MENA cases due to their strong wind resources, contrasting seasonal profiles, and strategic ambitions for export-oriented hydrogen development [

19,

31].

Oman stands out in the Arabian Sea region for its strong offshore wind resources, particularly along its southern coastal zones. Offshore wind speeds of 8–10 m/s at 50 m hub height have been observed near Oman’s southern coastal zone, especially in the Oman Maritime Zone (OMZ). These wind speeds are notably higher than those found inland or near-shore, making offshore sites particularly attractive for energy generation [

13]. Oman has prioritized green hydrogen production, aiming to leverage its renewable energy resources for both domestic use and export, particularly to Asia and Europe [

29,

32]. The combination of strong coastal wind resources and national strategies for renewable energy positions Oman to become a major exporter of green hydrogen, supporting global decarbonization efforts [

29,

32,

33].

Egypt is recognized as a potential hotspot for green hydrogen production, leveraging its abundant wind (especially in the Gulf of Suez) and solar resources. Studies have shown that regions like Gulf of Suez in the Red Sea governorate can achieve competitive green hydrogen costs, with reported expenditures around

$4/kg, highlighting the economic feasibility of green hydrogen in the Suez Gulf area [

34,

35]. The competitiveness of green hydrogen in Egypt is influenced by fluctuating energy prices, production costs, and transport costs. A decline in natural gas prices could temporarily make blue hydrogen more competitive, but Egypt’s strong renewable resources position it well for green hydrogen leadership if it can maintain competitive pricing [

19]. The transition to green hydrogen dominance is expected between 2030 and 2040, with Egypt well-positioned to capitalize on this shift if it maintains competitive pricing and adapts to market dynamics.

Egypt’s strategic location at the crossroads of Africa, Europe, and Asia, and its proximity to the Suez Canal, provides a logistical advantage for exporting green hydrogen to major markets. This geographic connectivity supports Egypt’s ambition to become a global hydrogen exporter [

19,

36]. Oman’s strategic plans and policy support for renewable energy and hydrogen production are evident in its Vision 2040 and ongoing feasibility studies for green hydrogen, including techno-economic optimization of wind-based hydrogen refueling stations [

32,

37]. These factors collectively explain why Egypt is well-positioned for large-scale green hydrogen projects and export, while Oman’s strengths are in renewable resource consistency and strategic planning, albeit with water-related constraints.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 outlines the modeling framework and techno-economic methodology.

Section 3 presents the selected offshore sites and wind resource assessment for Egypt and Oman.

Section 4 analyzes offshore wind farm performance, while

Section 5 evaluates green hydrogen production.

Section 6 reports the economic results and sensitivity analysis.

Section 7 discusses the findings in environmental and policy contexts, and

Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Modeling Framework and Theoretical Aspect

This paper employs a multidisciplinary modeling framework to assess the viability of offshore wind-powered electricity and green hydrogen production in Egypt and Oman. The methodology integrates wind resource assessment, offshore wind farm simulation, electrolyzer system modeling, and techno-economic performance analysis using the HOMER Pro software 3.18.4 [

38,

39]. HOMER Pro is a widely recognized simulation and optimization tool for the design and techno-economic evaluation of hybrid renewable energy systems, including green hydrogen applications. It enables integrated modeling of system components, operational scenarios, and economic performance, and is therefore extensively adopted in both academic research and practical system planning [

40,

41,

42,

43].

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the framework follows a structured five-step approach. First, potential coastal sites in both countries are evaluated through a wind resource assessment based on meteorological data to determine wind availability, seasonal variability, and capacity factors. In the second step, offshore wind power generation is modeled using a 120 MW wind farm configuration comprising 15 Vestas 8 MW offshore wind turbines, accounting for site-specific wind conditions and turbine performance. Vestas 8 MW represents the current state-of-the-art in offshore wind turbine technology and is widely used as a reference model in technical assessments and energy potential studies worldwide [

44,

45,

46].

The third step involves coupling the simulated power output with the electrolyzer system to estimate annual hydrogen production (kg/year), incorporating system efficiency and operational parameters. The fourth one consists of a techno-economic analysis to compute LCOE in

$/kWh and LCOH in

$/kg, considering capital expenditures, operating costs, and project lifespans. Finally, a comparative analysis is conducted to evaluate the performance of both countries in terms of energy output, seasonal efficiency, cost competitiveness, and the readiness of policy and infrastructure to support hydrogen development. This integrated approach enables a comprehensive evaluation of the offshore wind-to-hydrogen pathway in the MENA region. In detail, the steps are outlined in

Figure 3.

The performance of the modeled offshore wind farms was evaluated using a set of key performance indicators that reflect both the technical and economic viability of the projects. These include the capacity factor (%), which measures the efficiency of electricity generation relative to the turbines’ rated capacity; the annual energy production (GWh), representing the total electricity yield over a year; and LCOE ($/kWh), which is determined as the principal economic indicator, integrating capital costs, operating expenses, and project lifespans to quantify the competitiveness of offshore wind power at each site. These key performance indicators provide a comprehensive assessment of offshore wind system performance and its suitability for coupling with green hydrogen production. These key performance indicators are defined mathematically using Equations (1)–(6), as presented below.

Capacity Factor (

%)

where

= actual annual energy output of the wind farm (kWh);

= installed capacity of the wind farm (kW);

= total hours in a year (8760 h).

where

is a power curve of the selected wind turbine;

is wind speed duration function, calculated as:

For wind speed

,

is the Weibull probability density function [

11].

Note that by using the wind speed at 10 m

above sea level—the standard height advised by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO)—as a reference, we can calculate the wind speed at any height (

)

as follows:

where

denotes wind shear coefficient, taking

equal to 0.105 for offshore wind speed [

47].

Levelized Cost of Electricity (

LCOE,

$/kWh)

where

= wind turbine investment cost in year .

= expenses for operations and maintenance (OM) in year

t. The operation and maintenance cost is taken as 50

$/kW/year, which represents the average of the typical range (40–60

$/kW/year) reported in reference [

48] for offshore wind systems.

= Replacement cost in year t.

= electricity generation in year t.

= the amount of electricity generated during the installation’s first year.

= discount rate.

= expected lifetime of wind farm.

DR = Degradation factor; a 1.6% yearly output decrease for wind turbines has been estimated [

49].

Table 1 presents the offshore wind turbine investment expenses, average operation and maintenance cost, replacement cost, expected lifetime, and discount rate.

In this stage, the electrical output from the simulated offshore wind farms is supplied to the electrolyzer system. The system is modeled to estimate the annual hydrogen yield (kg/year) based on electrolyzer efficiency, operational parameters, and capacity utilization. This step establishes the link between renewable electricity generation and the possibility of producing green hydrogen. The total hydrogen yield (

in kg/year is calculated as follows:

where

The levelized cost of hydrogen (

LCOH) is calculated as the ratio of the discounted total lifecycle costs to the discounted total hydrogen production over the project lifetime, as expressed below:

where

3. Wind Resource Assessment

Two coastal locations, as indicated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, were selected for this study: Ash Shuwaymiyyah, Dhofar Governorate, Oman (17.3° N, 56.0° E), situated along the Arabian Sea, and the Gulf of Suez, Egypt (Safaga: 29.5° N, 32.4° E), located along the Red Sea-a region known for its strong and consistent wind resources. These sites were chosen based on their high offshore wind potential, the availability of reliable meteorological data, and their strategic relevance to national renewable energy development plans. According to Reference [

13], the selected location in Oman lies 22 to 44 km from the coast, with water depths ranging up to 50 m, making it suitable for bottom-fixed offshore wind turbine installation. It is worth noting that existing wind farms in the Ash Shuwaymiyyah region are located onshore, whereas the present study focuses exclusively on an offshore site, where wind resources are stronger and more consistent. In Egypt, Reference [

12] reports that the Gulf of Suez study area features water depths between 5 and 60 m, with distances from shore ranging from 1.5 km to over 200 km, offering a broad range of deployment options depending on technical and economic considerations.

To ensure the statistical reliability of the long-term offshore wind energy potential, this study utilizes hourly wind speed profiles based on a Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) derived from the PVGIS platform [

57], which integrates historical meteorological data from 2005 to 2023. PVGIS is a free and open-access platform developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). It provides access to meteorological data such as air temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, and relative humidity [

58]. The study recognizes the critical importance of such high-resolution datasets for accurate energy assessment; for instance, the literature [

44,

59] specifically utilized ERA5 reanalysis data for assessing offshore wind resources in the Mediterranean region, highlighting the reliability of reanalysis-based tools for large-scale technical assessments.

As demonstrated in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the TMY is constructed as a composite year by selecting the most representative months from this multi-decadal period, ensuring that the dataset reflects long-term average meteorological conditions rather than a single-year snapshot. To mitigate concerns regarding regional aggregation, simulations were conducted using site-specific coordinates for the Gulf of Suez and Ash Shuwaymiyyah. While the TMY approach is optimized for assessing typical technical feasibility, the underlying wind data is sourced from reanalysis datasets, a methodology consistent with established assessments of offshore resources in similar maritime regions that leverage high-resolution ERA5 reanalysis data.

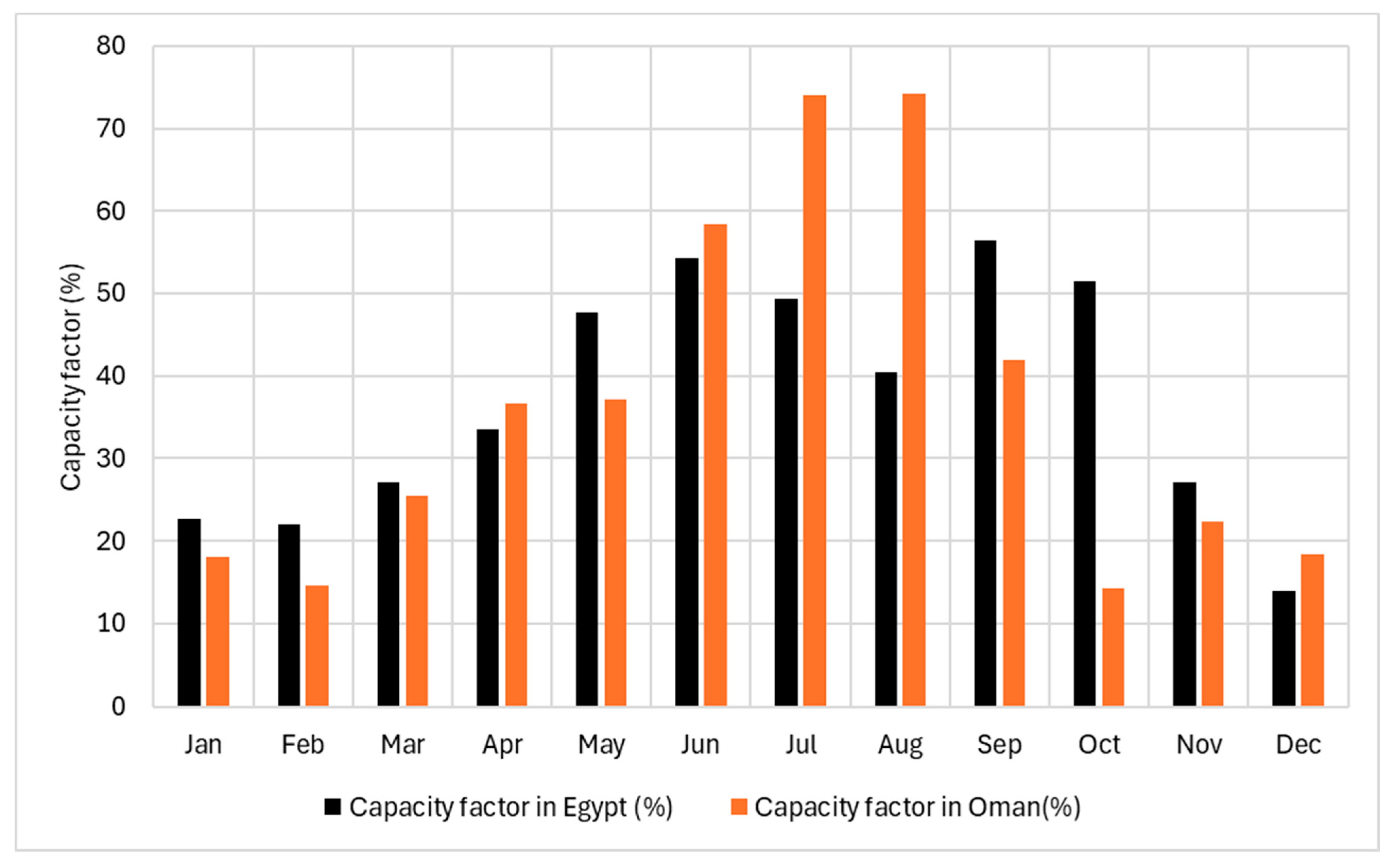

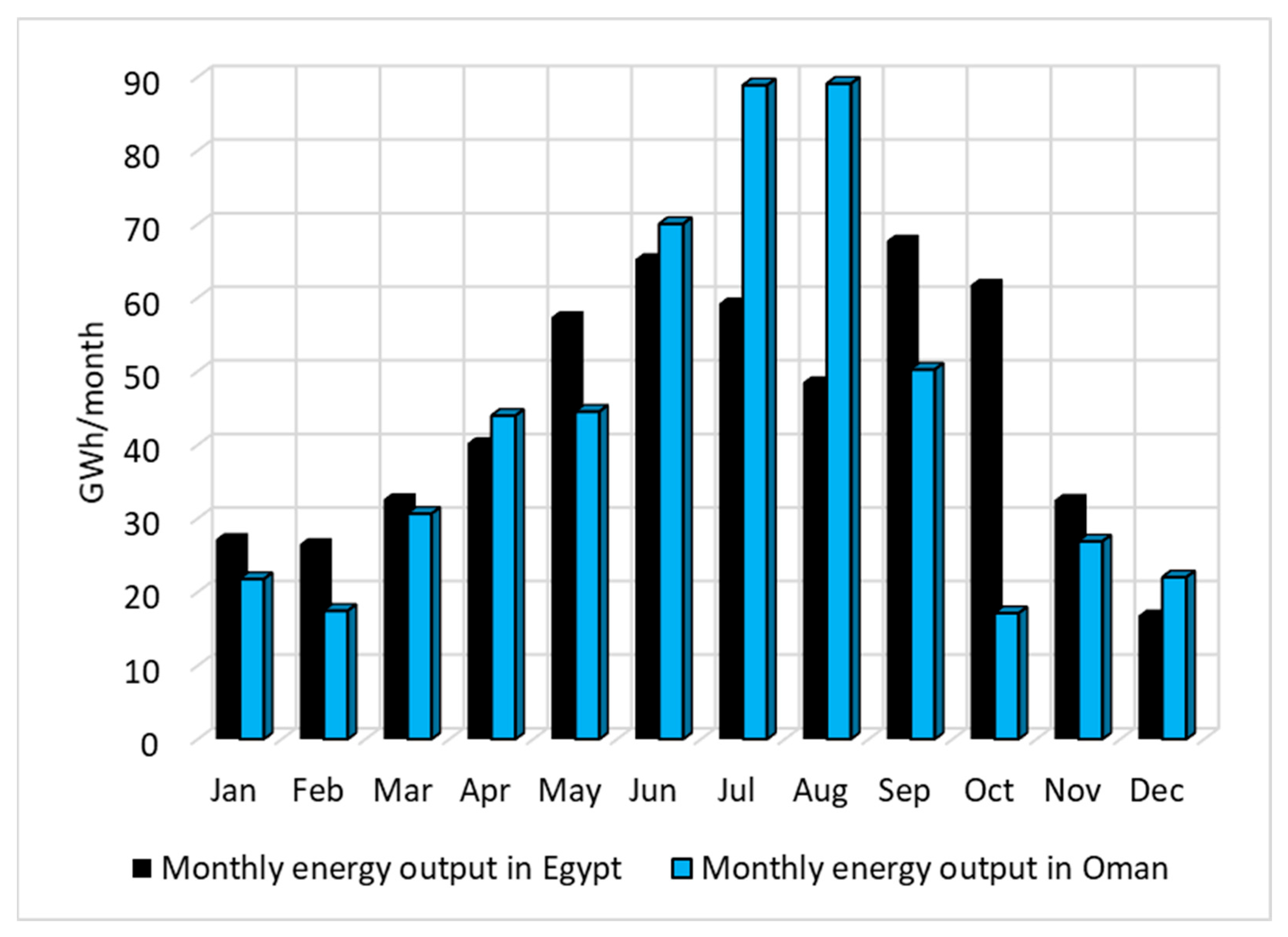

Figure 4 presents the TMY average wind speeds for each month in Egypt and Oman. The data reveals distinct temporal patterns in wind resource availability across the two locations, reflecting their respective climatic and geographic characteristics. In Egypt, wind speeds remain relatively stable throughout the year, ranging from 4.348 m/s in December to a peak of 8.464 m/s in September. The period between May and October generally exhibits higher wind speeds, with values consistently exceeding 7 m/s, indicating a relatively steady offshore wind regime suitable for continuous energy production and hydrogen generation. Conversely, Oman demonstrates a more pronounced seasonal variation. Wind speeds in Oman decline from October to March, with a minimum monthly average of 4.188 m/s in October, which is comparable to the minimum observed in Egypt (4.348 m/s). However, the key distinction lies in the pronounced seasonal variability and the substantially higher summer wind speeds observed in Oman. However, from June to August, Oman experiences a dramatic surge in wind intensity, reaching 13.695 m/s in July and 12.858 m/s in August. This spike is attributed to the influence of the Khareef (summer monsoon) season, which significantly enhances coastal and offshore wind potential along the southern Arabian Sea. The high wind speeds during these months offer an excellent opportunity for peak hydrogen production, albeit with strong seasonality.

The comparison underscores two key insights:

Egypt’s wind profile is more uniform and consistent year-round, which supports stable and predictable electricity and hydrogen output.

Oman’s wind profile is highly seasonal, with exceptional wind resources in summer months, suggesting the potential for seasonal hydrogen overproduction, which may require storage or complementary energy balancing strategies.

These differences in wind speed profiles highlight the complementary nature of the two sites in a regional hydrogen strategy. Egypt can ensure year-round supply, while Oman can capitalize on seasonal surpluses to meet peak demand or export hydrogen during periods of high production.

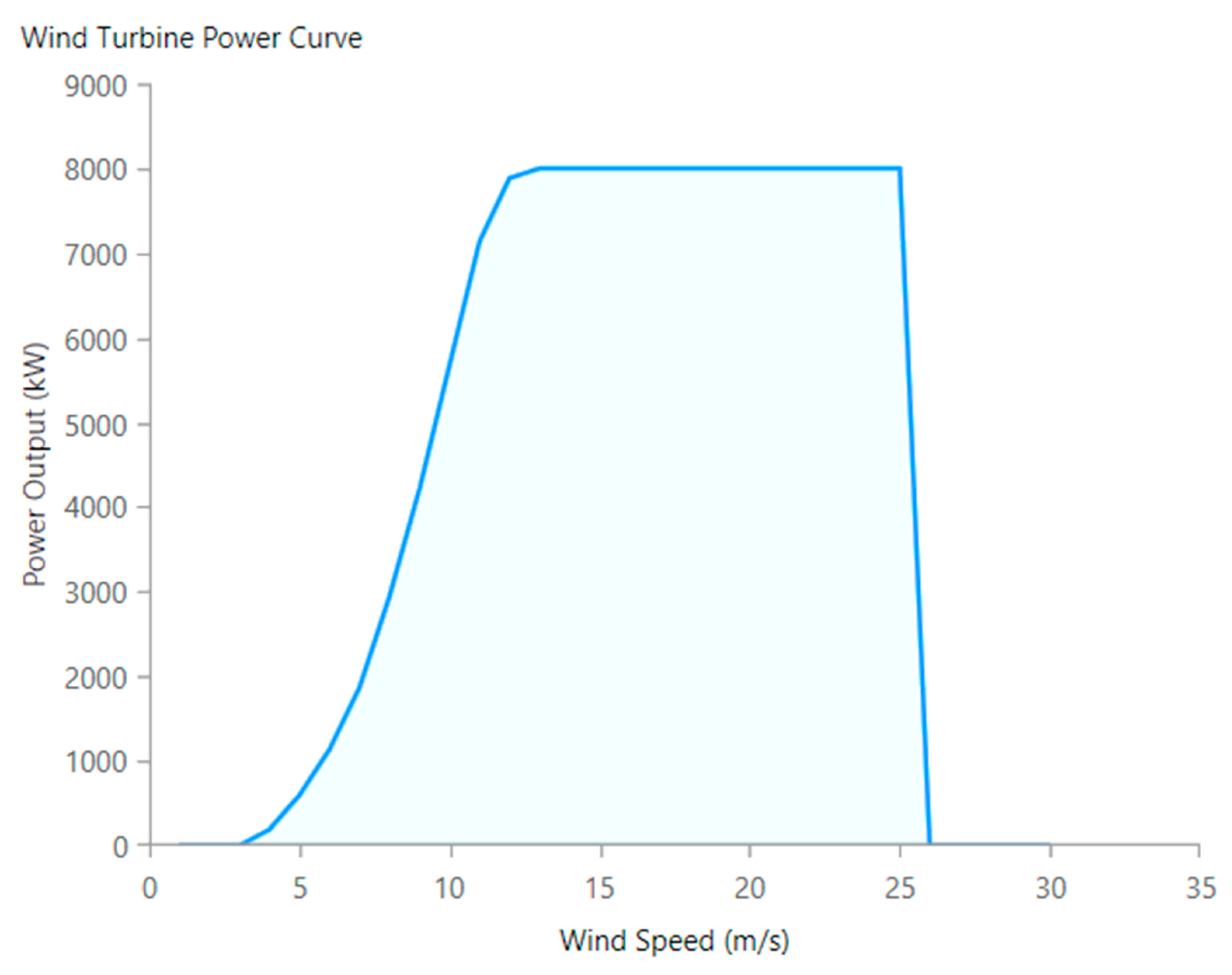

The offshore wind resource assessment in this study was simulated using the Vestas -8 MW wind turbine model (

Figure 5), selected for its proven reliability, high energy yield, and widespread commercial deployment in large-scale offshore wind projects [

44]. The turbine features a rotor diameter of 164 m, and is capable of delivering a rated power output of 8.0 MW at a cut-in wind speed of around 4 m/s and a cut-out speed near 25 m/s. A total of 15 turbines were modeled at each site to form a 120 MW offshore wind farm. The simulation accounts for site-specific wind resource data, turbine power curves (

Figure 5), hub height wind speeds, and wake loss effects using standard layout configurations (

Table 5). The resulting hourly power output serves as the primary energy input for the downstream green hydrogen production system via electrolysis.

6. Economic Analysis

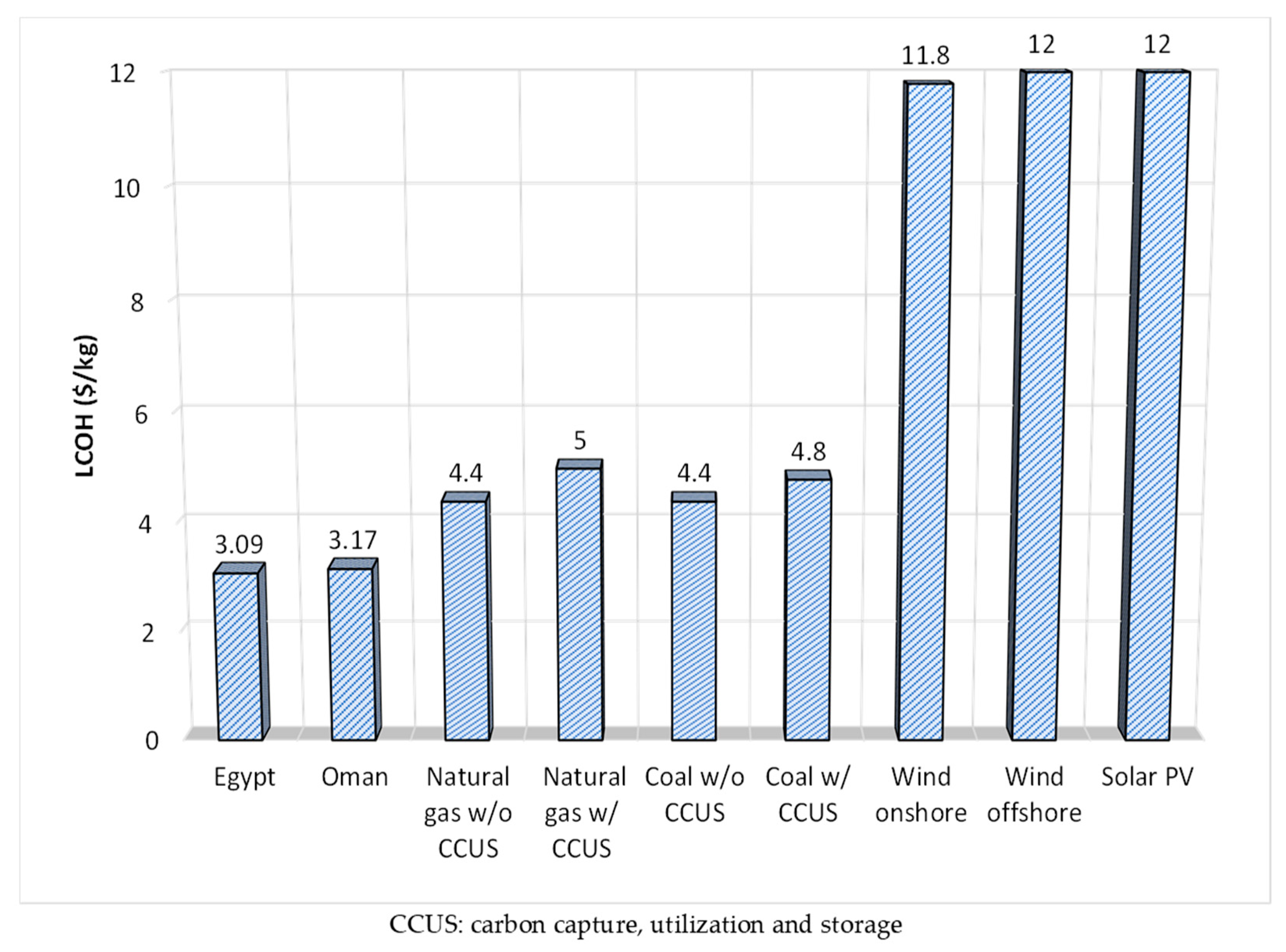

Table 7 compares the economic performance of offshore wind-to-hydrogen systems in Egypt and Oman in terms of LCOE and LCOH. The results indicate that Egypt exhibits a slightly lower LCOE of 0.035

$/kWh compared to 0.036

$/kWh in Oman. LCOH in Egypt is calculated at 3.09

$/kg, slightly below Oman’s 3.17

$/kg, indicating that Egypt holds a small but measurable cost advantage in hydrogen production. These results demonstrate that both locations are economically competitive on a global scale, with LCOH values significantly lower than many international benchmarks. The narrow gap in performance further supports the complementary role of Egypt and Oman in a regional green hydrogen strategy, where Egypt may serve as a reliable, low-cost base-load producer, while Oman contributes high-output capacity during peak wind seasons.

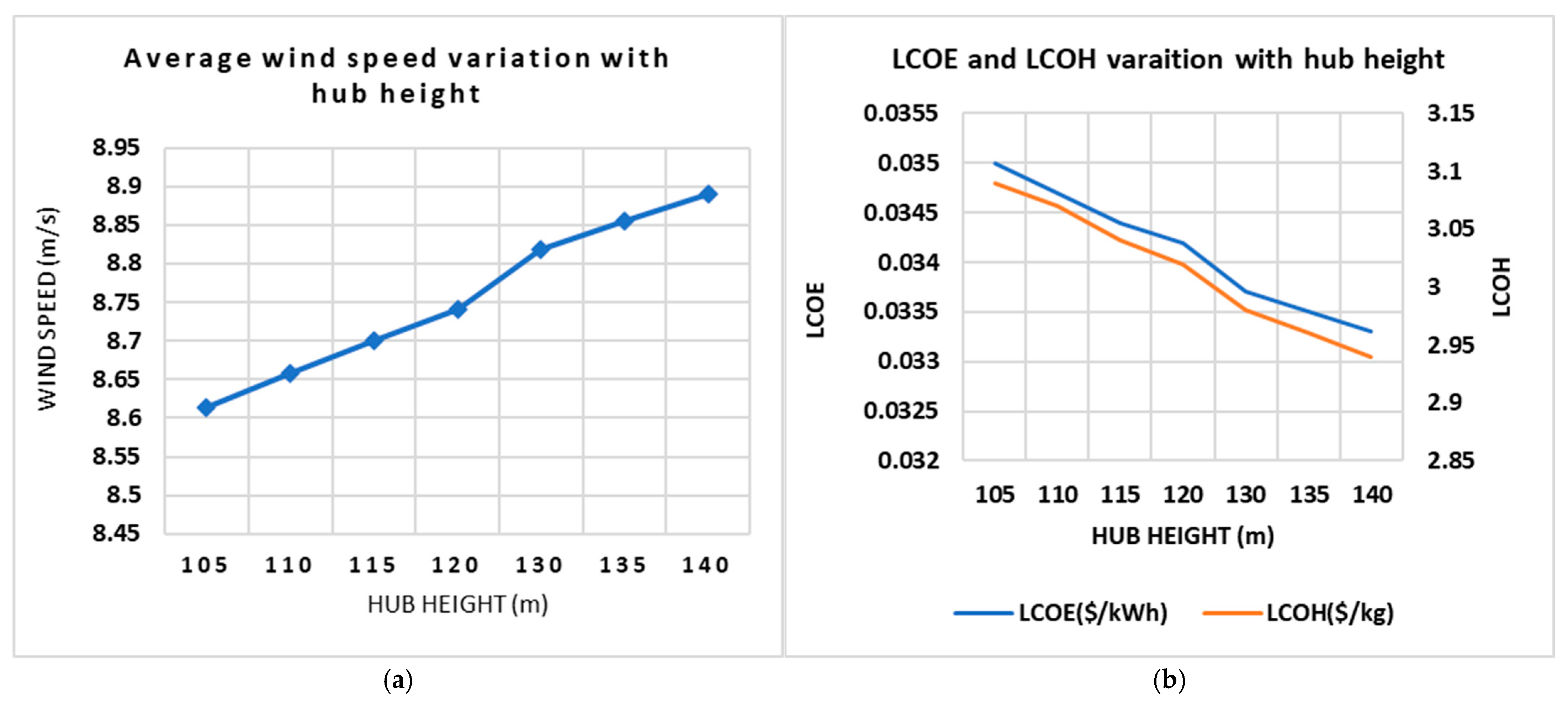

In offshore wind energy systems, wind speed is the dominant factor influencing both energy output and economic performance. Since wind speed typically increases with elevation due to the wind shear effect, selecting an appropriate hub height becomes a critical design consideration. The impact of increasing turbine height on wind speed, as well as on the resulting cost of electricity and hydrogen, warrants detailed analysis. To simulate these effects, the hub height of the wind turbine was varied from 105 to 140 m, representing the typical range for the wind turbines and reflecting conditions encountered at different elevations or nearby coastal zones. Taking Egypt as a reference case study, for each hub height value, the corresponding average wind speed, LCOE, and LCOH were recalculated using the consistent techno-economic framework employed throughout this study. This approach enables a systematic assessment of whether variations in hub height have a significant impact on system performance, or whether such effects are marginal and can be reasonably neglected in preliminary design stages.

Figure 8a illustrates the relationship between turbine hub height and average wind speed, while

Figure 8b presents the corresponding variations in the LCOE and the LCOH. As the hub height increases from 105 m to 140 m, the average wind speed rises only marginally—from approximately 8.60 m/s to 8.90 m/s—indicating a modest gain of about 0.32 m/s. Consequently, the impact on both LCOE and LCOH is minor: LCOE decreases slightly from around 0.035

$/kWh to 0.0333

$/kWh, and LCOH drops from 3.09

$/kg to 2.94

$/kg.

While the trend is technically favorable, the overall economic benefit is limited and likely insufficient to offset the significantly higher capital expenditures associated with the structural and installation complexities of taller offshore towers. This sensitivity analysis suggests that increasing hub height alone does not result in substantial cost reductions under the given site conditions. Therefore, design decisions regarding turbine height should carefully weigh the trade-off between increased structural costs and the relatively small economic benefits gained from marginal improvements in wind speed and energy yield.

8. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the techno-economic viability and environmental benefits of offshore wind-powered green hydrogen production systems at two coastal locations: Ash Shuwaymiyyah, Dhofar Governorate, Oman, and Safaga, Gulf of Suez, Egypt. By simulating a 120 MW offshore wind farm integrated with the electrolyzer system in both countries, we show that the systems can achieve high annual capacity factors—51% in Egypt and 49.7% in Oman—and produce more than 11 million kilograms of green hydrogen annually at globally competitive costs. Egypt’s stable wind profile supports continuous year-round production with a lower LCOH of $3.09/kg, while Oman’s monsoonal wind patterns enable high-output seasonal production despite a slightly higher LCOH of $3.17/kg. The environmental assessment was strengthened by adopting a dual-scenario framework. When offshore wind electricity is considered as a substitute for fossil-fuel-based grid electricity, annual CO2 mitigation reaches up to 240,000 tonnes in Egypt and 256,000 tonnes in Oman. Alternatively, if the green hydrogen displaces conventional gray hydrogen from steam methane reforming, the avoided emissions amount to 126,500 and 123,200 tonnes of CO2 per year, respectively. This dual approach enhances the robustness of the sustainability analysis and aligns with both energy system and hydrogen market decarbonization goals.

Furthermore, sensitivity analysis shows that increasing turbine hub height from 105 m to 140 m results in only marginal gains in wind speed and minor reductions in LCOE and LCOH, suggesting limited economic advantage under current conditions. These findings emphasize that system optimization should prioritize integration strategies and hydrogen infrastructure over turbine structural expansion alone. In conclusion, Egypt and Oman offer complementary strengths: Egypt provides consistent base-load hydrogen supply supported by established infrastructure and grid connectivity, while Oman excels as a seasonal exporter due to its high summer wind intensity and strategic energy vision. Together, they represent a scalable, regionally integrated model for positioning the MENA region as a global leader in the emerging green hydrogen economy.

Future research should extend the proposed assessment framework to additional offshore sites in Egypt, Oman, and other MENA countries to capture spatial variability in wind resources and infrastructure readiness. In addition, further work should focus on optimal system configuration through integrated simulation-optimization approaches, including optimal wind turbine design, hub height selection, and wind farm layout optimization. Finally, incorporating a fully integrated green hydrogen supply chain, covering compression, storage, transport, and potential conversion to hydrogen carriers, would provide a more comprehensive basis for evaluating export-oriented hydrogen strategies and long-term investment decisions.