1. Introduction

Photovoltaic array faults are common and critical issues in the operation of photovoltaic (PV) power generation systems. They are a major cause of instability in operational conditions, reduced generation efficiency, and poor economic performance. When the faults occur, they not only reduce power output but also pose a threat to the stability of the entire energy supply system, potentially leading to substantial economic losses and safety risks. Therefore, developing efficient and accurate fault classification technologies for photovoltaic arrays is crucial to ensuring stable PV system operation, enhancing power generation efficiency, and achieving safe production. Such technologies can effectively reduce resource wastage and economic losses caused by faults while significantly improving system reliability and sustainability, thus laying a solid foundation for the efficient development and utilization of renewable energy.

Traditional fault classification methods for photovoltaic modules can be broadly categorized into two types: rule-based unsupervised classification methods and supervised deep learning methods. Rule-based methods typically rely on expert knowledge or predefined rules, such as analyzing deviations in operational parameters [

1] and setting thresholds to detect faults [

2]. While these methods are simple and easy to implement, their rule-based nature heavily relies on expert experience, which makes them inflexible and poorly suited to complex, dynamic scenarios. As a result, they lack the ability to generalize across varied conditions. On the other hand, supervised deep learning methods, such as using KNN for early detection and diagnosis in photovoltaic DC systems [

3,

4] or employing CNNs for detecting defects in PV aerial images [

5], can automatically learn features and perform classification. However, despite the automatic extraction of image features, deep learning approaches in PV fault classification are not explicitly designed for this purpose and do not fully leverage the specific features of faults. As a result, their performance in classifying complex PV fault patterns remains suboptimal.

Texture, as the spatial distribution pattern of surface grayscale or color in an image, can intuitively reflect the physical changes in photovoltaic (PV) modules caused by faults [

6]. For instance, cell faults, which occur due to localized resistance increases and abnormal temperature rises, manifest as discrete bright spots in infrared images, exhibiting high contrast and non-uniform texture. Cracks in the solar cells appear as dark linear textures in images, with directional and continuous features. Aging degradation leads to a gradual loss of texture uniformity on the module surface, accompanied by randomly distributed granular noise. Based on this understanding, we engaged in in-depth discussions with domain experts and analyzed a large volume of data, focusing particularly on the texture features in PV data. Our analysis revealed a strong correlation between texture features and faults. To further investigate this, we conducted a preliminary experimental study, where exploratory analysis of sample data confirmed that texture features play a significant role in fault detection.

To address the issues mentioned above, this paper proposes an enhanced fault classification method for photovoltaic modules using texture features. The method utilizes the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) [

7] to extract textural attributes from infrared images. A feature fusion module is added to the traditional ResNet50 network, which combines the texture features with the high-level semantic features extracted by the deep network, thus enhancing the classifier’s sensitivity to different fault types. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed enhanced network, through joint modeling of texture and deep features, exhibits a significant improvement in fault diagnosis accuracy.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We validate the importance of texture features in PV fault classification through experimental studies on infrared image data from photovoltaic modules, revealing a significant correlation between these features and fault types.

We propose an improved ResNet50 network that integrates texture features enhancing both classification accuracy and model robustness.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the related work.

Section 3 explores the correlation between texture features and fault types through a pilot study, providing the foundation for further research.

Section 4 outlines the implementation of the proposed method, including texture feature extraction, network improvements, and classifier optimization.

Section 5 evaluates the method’s effectiveness.

Section 6 discusses the study’s limitations, and

Section 7 concludes with the research findings, innovations, and future directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Photovoltaic Fault Classification Technology

2.1.1. Fault Classification Methods Based on Electrical Characteristics

Fault classification methods based on electrical characteristics analyze I-V data from PV modules using various machine learning techniques. Azhar Ul-Haq et al. [

8] utilized multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) to classify faults, while Muhammed Hussian et al. [

9] achieved 97.9% accuracy by combining radial basis function networks and MLPs. WANG [

10] demonstrated that support vector machines (SVMs) offer superior accuracy and generalization, and Xia et al. [

11] effectively detected DC arc faults by integrating wavelet packet decomposition with SVM. Additionally, Mouleloued et al. [

4] enhanced early fault detection through an improved KNN algorithm, and Liu et al. [

12] addressed the challenges of imbalanced datasets with the FSR-SSL framework, improving accuracy to 99%.

Despite advantages like simplicity, interpretability, and cost-efficiency, these methods face limitations. Fault detection granularity is restricted to the module string level due to hardware constraints, making it difficult to identify specific faulty components. Moreover, accurately classifying multiple fault types within a single module string remains a significant challenge.

2.1.2. Fault Classification Methods Based on UAV Aerial Imagery

Fault classification methods using UAV aerial imagery combine UAV technology with advanced image analysis algorithms and have rapidly emerged as an innovative approach to PV inspection. By equipping UAVs with sensors to capture aerial imagery and performing classification on ground-based servers, this method was initially applied in distribution grid scenarios. In the visible light domain, CNNs have become the mainstream approach for analyzing UAV aerial imagery. Li et al. [

13] proposed a CNN-based method to identify faults like dust shading, delamination, and snail trails, achieving state-of-the-art results. For detecting faults invisible to the naked eye, electroluminescence (EL) imagery, with its high spatial resolution, enables precise classification of surface defects. Sergiu et al. [

14] successfully classified faults such as broken grids and microcracks using EL imagery, though the ultra-high resolution poses challenges for image acquisition and processing efficiency. Infrared (IR) images, offering higher UAV capture efficiency and comprehensive fault detection, have become the dominant choice for UAV-based PV inspection. Acciani et al. [

15] demonstrated the utility of IR images for identifying issues like hotspots and fractures. Advanced methods, such as the residual channel attention gate network by Su et al. [

16], effectively address challenges like disappearing fault features in deep networks by introducing attention mechanisms to fuse multi-scale features. Innovative deep learning models have further advanced UAV-based fault classification. Rudro et al. [

17] integrated InceptionV3-Net and U-Net architectures with image segmentation, achieving validation accuracy of 98.34% and test accuracy of 94.35%. Similarly, Vasanth. et al. [

18] combined texture feature extraction via pre-trained networks (e.g., DenseNet-201, ResNet-50, and AlexNet) with machine learning classifiers. The DenseNet-201 with the k-nearest neighbor (IBK) classifiers achieved a perfect classification accuracy of 100.00%, outperforming other combinations. Liao et al. [

19] proposed a fast, accurate method for solar module fault classification using grayscale conversion, filtering, temperature representation, and cumulative density function analysis, enabling rapid fault identification. Despite achieving over 90% accuracy in supervised IR-based PV fault classification, these methods face challenges such as limited PV image datasets and the labor-intensive nature of data annotation.

In this study, we selected ResNet50 as the backbone model for PV fault classification based on several considerations. First, ResNet50, with its deep residual connections, effectively mitigates the vanishing gradient problem while capturing multi-level feature representations, making it particularly suitable for learning complex texture features. Compared to shallower networks, ResNet50 demonstrates superior feature extraction capabilities, enabling more effective differentiation of various PV fault types. Second, previous studies [

18] have shown that ResNet50 exhibits strong generalization ability in PV image analysis tasks. Furthermore, we optimized the ResNet50 architecture by integrating texture features, enhancing the model’s robustness and improving its ability to recognize complex fault patterns.

2.2. Optimized Texture Feature-Based Method for Photovoltaic Module Fault Classification

This paper proposes a method leveraging textural attributes to optimize fault classification models for photovoltaic (PV) modules, aiming to enhance classification efficiency and accuracy. Existing studies in texture feature-based image classification provide valuable references. Zhang et al. [

20] introduced a dual-stream neural network to enhance texture feature extraction for image classification tasks. Lethikim et al. [

21] proposed a gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM)-based technique for two-dimensional interval data representation in images, combined with an automatic fuzzy clustering algorithm using the Bayesian approach, forming a novel classification method. Vieira et al. [

22] applied a pseudo-parabolic diffusion process to texture recognition, achieving success in classifying plant species based on leaf surface images. Simon et al. [

23] combined convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for texture feature extraction with support vector machines (SVMs) as classifiers, demonstrating superior performance on grayscale and color texture databases. Huang et al. [

24] developed a texture feature extraction method using ICA filters, showing strong discriminative ability for both global and local texture features. Yongsheng Dong et al. [

25] proposed a multi-scale rotation-invariant texture representation method, generating MRIR vectors for texture classification, which outperformed other representative methods. Wei et al. [

26] introduced a novel texture feature extraction approach considering spatial continuity and grayscale diversity, achieving significant success in remote sensing image classification.

2.3. Feature-Enhanced Deep Learning Method

Building upon the extraction of texture features, this paper focuses on combining these features with deep learning techniques to construct a more powerful model for photovoltaic (PV) module fault classification. This approach leverages the expressive power of texture features and the strong pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning to improve classification accuracy. Farghaly et al. [

27] integrated advanced texture feature extraction methods, including GLCM, GLDM, and wavelet transform, with a deep learning framework for accurate classification of chest X-ray images in diagnosing lung diseases. Zhou et al. [

28] proposed a fine-grained image classification method based on feature enhancement, utilizing a pyramid residual convolution module, soft pooling, and a feature focus module to extract multi-scale discriminative features. Zhang et al. [

29] enhanced low-level features with an attention mechanism for image classification, using EfficientNet as the backbone network to achieve superior classification performance. Siar et al. [

30] incorporated features generated from feature extraction methods into a CNN framework for fault classification in MRI images, achieving high accuracy. Pichandi et al. [

31] developed a hybrid deep learning model combining AlexNet and DenseNet for brainwave-based emotion classification, where PCA-reduced features were classified using multi-class SVM.

Inspired by these approaches, we propose an improvement in the classification of PV module faults by integrating texture feature extraction with a deep learning-based classification model specifically tailored for photovoltaic (PV) module fault detection. This method leverages the strengths of both texture features and deep residual networks, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of the fault classification process.

3. Pilot Study

3.1. Sample Data Description

In this paper, we utilize the operational data from a photovoltaic power plant to collect 3000 infrared images of photovoltaic modules. These images were captured using a DJI M300 UAV equipped with an H20T dual-light gimbal camera, featuring a 1/2.3” CMOS sensor (12 MP) and an equivalent focal length of 24 mm. The UAV was manufactured by Shenzhen Dajiang Innovation Technology Co., Ltd., based in Shenzhen, China. This drone-based setup ensures high-resolution imaging and allows for consistent data collection from varying angles and altitudes, improving the model’s adaptability to real-world scenarios. To ensure image consistency, all images were acquired at a fixed resolution. Given that some acquired images contain black edge areas, which may interfere with model training, we first trim the images, reducing their original size from 40 × 24 to 36 × 22, thereby eliminating irrelevant regions and minimizing unnecessary noise. This cropping process focuses the images on the core area of the PV modules, effectively enhancing both the training accuracy and detection performance of the model. Following cropping, to further standardize the input data, all images undergo normalization, scaling pixel values to the range [0, 1]. This step accelerates the model’s training process and reduces the impact of varying gray-levels on model performance. Additionally, the emissivity parameter was set to 0.9 during data collection, following standard practices for photovoltaic module inspections to ensure accurate thermal imaging measurements. The dataset is class-balanced, with 500 images per fault type, mitigating selection bias and supporting a fair evaluation of classification performance across various fault categories. The preprocessed images will serve as input data for subsequent model training and testing.

3.2. Texture Correlation Experiments

3.2.1. Experimental Design

To validate the effectiveness of texture features in PV module fault classification, a pilot study was conducted to investigate the strong correlation between texture features and PV faults. The study utilized operational data from a photovoltaic power plant, collecting infrared images of PV modules, which were then annotated and classified. Specifically, 3000 infrared images, each containing a single module, were collected, with 500 images corresponding to each fault type. The fault types included hotspots, module cracking, diode failure, module offline failure, and others. Detailed images and descriptions for each fault type are presented in

Figure 1.

Texture features were extracted using the GLCM method, with statistical features such as energy, contrast, homogeneity, and correlation computed for each image, as summarized in

Table 1. Subsequently, a Pearson correlation analysis [

32] was performed to quantitatively assess the relationship between different fault types and texture features, evaluating the discriminative power of texture features for distinguishing various fault categories. The Pearson correlation coefficient, ranging from [−1, 1], indicates that values closer to 1 signify a stronger correlation between texture patterns and fault types.

In the formula of

Table 1, p(i,j) represents the element value in the grayscale co-occurrence matrix;

represents the mean of the row;

represents the mean of the column;

represents the standard deviation of the row;

represents the standard deviation of the column.

3.2.2. Experimental Conclusions

In this study, infrared images of photovoltaic (PV) modules were used as the experimental dataset to extract texture features, aiming to investigate their correlation with different fault types through statistical analysis. To ensure the rigor and reliability of our experimental analysis, we engaged in in-depth discussions with domain experts.

For correlation analysis, we employed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to assess the statistical relationship between texture features and fault types, followed by the computation of Spearman correlation coefficients to quantify the degree of association. ANOVA primarily evaluates whether the mean values of texture features differ significantly across fault types, thereby verifying their effectiveness in classification tasks. As shown in

Figure 2a, the experimental results indicate that the

p-values from the ANOVA tests are all significantly below 0.05, demonstrating that all the GLCM features play a statistically significant role in distinguishing different fault types.

As illustrated in

Figure 2b, the texture features exhibiting strong correlations with fault types include energy, contrast, homogeneity, correlation, and ASM. Specifically, energy, which measures texture uniformity, shows a strong positive correlation (0.53) with no-anomaly. This suggests that the texture distribution of non-faulty PV modules is more homogeneous, with minimal variations, facilitating differentiation from other fault types. Contrast, which reflects local variations in grayscale intensity, exhibits the highest correlation with shadowing (−0.49), followed by cracking (0.46), indicating that these fault regions typically exhibit abrupt texture changes. Homogeneity, which quantifies the consistency of pixel intensity distribution, is strongly correlated with cracking (−0.50) and no-anomaly (0.46). Experts suggest that this could be related to localized heat distribution patterns. Meanwhile, correlation, which measures the linear dependency between grayscale levels, demonstrates a notable negative correlation with cracking (−0.50). Experts attribute this to significant grayscale variations within shadowed regions, reinforcing the feature’s sensitivity to shadow-related faults. Additionally, while ASM exhibits statistical characteristics similar to energy, energy demonstrates superior discriminative power across different fault types. Consequently, we excluded ASM in subsequent experiments and retained energy as a key texture feature.

Based on these findings, we selected energy, contrast, homogeneity, and correlation for further feature integration and modeling. By integrating these features, we can create a more discriminative feature set for subsequent classification model training. These features will help improve the accuracy and efficiency of fault detection and classification in PV module fault diagnosis.

4. Methods

Through in-depth analysis of PV module fault classification tasks, we identified that texture features offer fine-grained classification insights. Therefore, this chapter proposes an improved network architecture that incorporates texture features. By integrating these features, the model’s expressiveness is enhanced, leading to a significant improvement in both the accuracy and robustness of fault classification.

4.1. Method Overview

This section introduces the overall framework for fault classification, where texture features are integrated into a deep learning model to build a more robust and accurate fault classification network. The design of the method aims to effectively combine texture information and deep features from the images, enhancing the model’s sensitivity to different fault types in photovoltaic modules.

The method can be summarized in the following stages: first, texture features are extracted from the infrared images of photovoltaic modules. To achieve this, we use the GLCM method to compute four key statistical features (energy, contrast, homogeneity, and correlation) that effectively capture the texture details of local image regions. Next, the ResNet50 deep learning model is employed to extract high-level semantic features, with the network progressively extracting both global and local deep features through convolution and pooling layers. Then, the texture features extracted by GLCM are fused with the deep features from ResNet50 at specific locations, forming a unified feature representation.

The overall network flow is illustrated in

Figure 3, encompassing the entire process from data preprocessing, texture feature extraction, and deep feature calculation to feature fusion and classification. This framework effectively integrates texture features with deep learning models, offering a novel approach to fault classification in photovoltaic modules. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method not only excels in classification accuracy but also exhibits strong model robustness, adapting well to diverse photovoltaic fault scenarios.

4.2. Construction of the Texture Feature-Enhanced Network

In this study, we propose an improved method that combines texture features with a deep learning model to enhance the recognition performance for PV anomaly classification tasks. Specifically, the energy, contrast, homogeneity, and correlation texture features derived from GLCM are concatenated with the output features from the average pooling layer of ResNet50, achieving effective feature fusion.

As shown in

Figure 4, building on the traditional ResNet50 architecture, the model first extracts low-level and high-level semantic features through its convolutional and pooling layers [

33,

34,

35]. The convolutional layers are responsible for extracting local features with shared parameters, while the pooling layers reduce dimensionality while preserving key information. Before the fully connected layer, we innovatively integrate the texture features extracted via GLCM with the high-dimensional feature maps output by the deep network, creating a unified feature vector. To ensure effective feature fusion, the concatenated feature vector is normalized to enhance its representational capacity. The final classification task is completed through the fully connected layer and activation functions.

By incorporating GLCM texture features, this approach achieves a complementary fusion of global texture information and local deep features. This not only improves the model’s capability for fine-grained anomaly classification but also demonstrates the value of feature fusion in complex scenarios. Experimental results show that this improved method significantly enhances the performance of PV fault diagnosis models.

4.3. PV Fault Classification

This study implements a fault classification model based on the PyTorch deep learning framework (version 1.13.1), emphasizing efficient optimization and stability throughout the design and training process. The input infrared images are cropped and normalized to a fixed size of 36 × 22 pixels to ensure the model can handle varying sample scales while standardizing inputs. The output node count is set to 5, corresponding to the fault categories: cell, cracking, diode, offline-module, shadowing, and no-anomaly.

Hyperparameters for the ResNet50 implementation were selected based on empirical experiments and best practices in deep learning for infrared image classification. The learning rate was initially set to 0.0001 and adjusted using a step decay strategy to balance convergence speed and stability. A batch size of 128 was chosen to balance training efficiency and hardware resource utilization, while the Adam optimizer was selected for its adaptive learning capabilities, enhancing convergence efficiency. The model was trained for 50 epochs, as performance stabilized around this point, using cross-entropy loss to address the multi-class classification task. Additionally, L2 regularization (weight decay) is applied with a coefficient of 0.0001 to penalize large weights, reducing model complexity and mitigating overfitting.

The classifier employs a combination of fully connected layers and a Softmax activation function. The fully connected layers apply linear transformations to the fused features, generating outputs that correspond to the number of fault categories. The Softmax activation function converts these outputs into a normalized probability distribution, clearly reflecting the likelihood of each sample belonging to a specific category.

Finally, the model completes the fault classification task by selecting the category with the highest probability as the predicted result. This design ensures robust classification performance while providing intuitive and interpretable predictions, making it well-suited for photovoltaic module fault diagnosis scenarios.

5. Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conduct comprehensive experiments on a photovoltaic (PV) module fault dataset. The evaluation primarily focuses on classification accuracy, robustness, and feature representation capability. We compare our approach with several baseline deep learning models to assess its advantages. Specifically, we first demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed model in classification tasks by comparing it with existing models and highlighting its strengths. Next, we analyze and compare the accuracy and recall of the proposed model in classification tasks, further validating its superiority. Finally, we evaluate the classification performance of the proposed model at different stages and present the results through visualization.

5.1. Comparison of Training Loss and Accuracy Curves with Classic Models

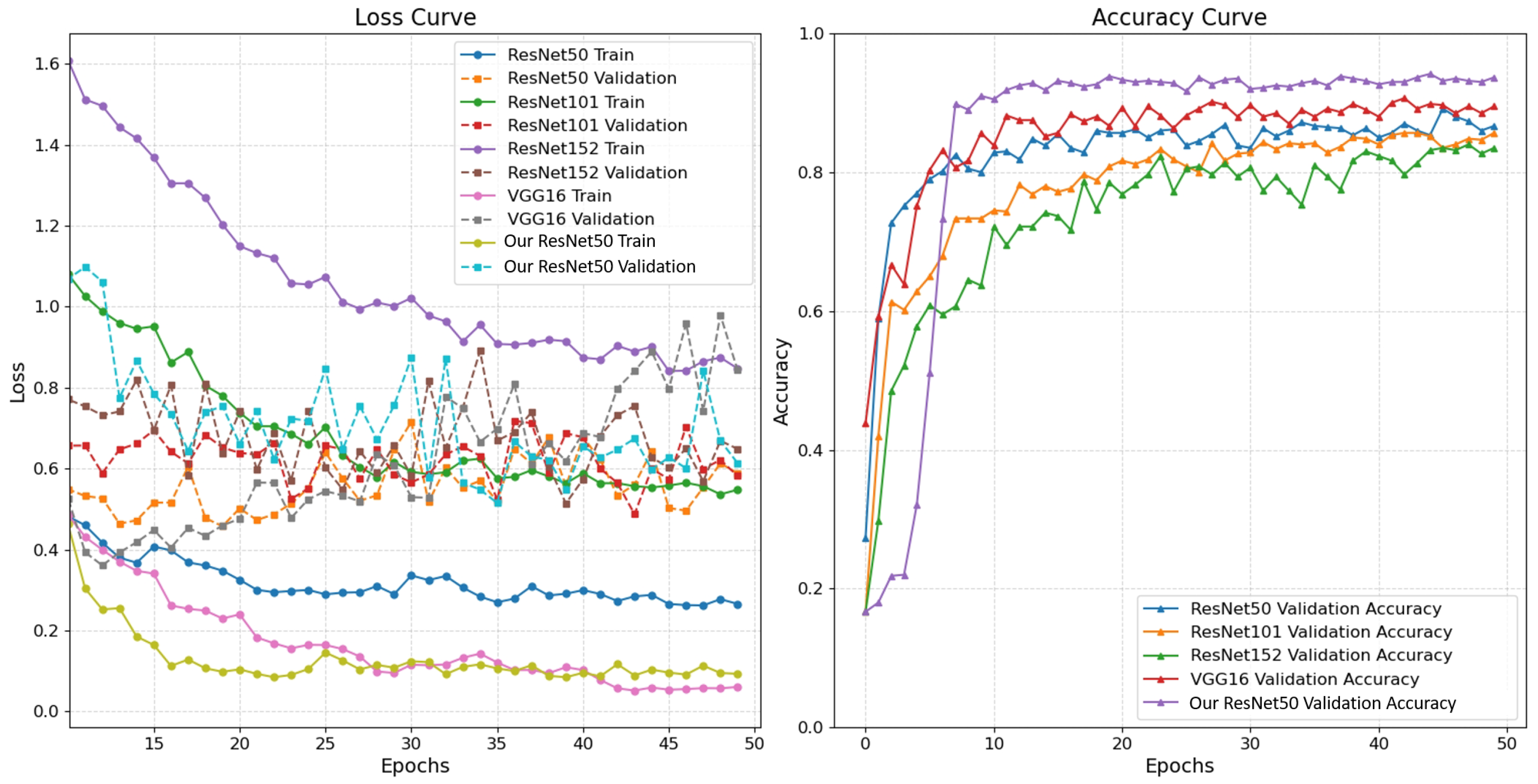

To validate the performance of the proposed method, we conducted evaluations on a photovoltaic module fault classification task. As illustrated in

Figure 5 after constructing the network, classification prediction results were obtained after 50 training epochs. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the feature concatenation module in the proposed fusion model, comparative experiments were performed with and without the use of the feature concatenation module. Additionally, the performance of classic models, including the original ResNet50, ResNet101, ResNet152, and VGG16, was tested on this task to assess their effectiveness in addressing the problem. The test results were then compared and analyzed against the proposed improved model, providing a more intuitive demonstration of the advantages and improvements brought by the proposed model in this task.

The results can be analyzed as follows:

From the loss curves, it can be observed that the training loss of our ResNet50 consistently remains lower than that of other models, demonstrating its superior performance. Specifically, the training loss of ResNet50 starts at approximately 1.5 and gradually decreases with the increase in training epochs, reaching close to 0.2 by the 50th epoch. In contrast, while the training losses of ResNet101 and ResNet152 exhibit a similar downward trend, their overall training losses remain higher than those of ResNet50. The training loss of VGG16 decreases more rapidly; however, its validation loss shows significant fluctuations in the early stages before gradually stabilizing.

From the accuracy curves, the training accuracy of our ResNet50 model is clearly superior to that of other models, achieving not only higher accuracy but also exhibiting smaller fluctuations in the curve. This demonstrates greater stability in the training process. Furthermore, this stability indicates that our ResNet50 is better at learning features during training and avoids excessive oscillations, making it more reliable compared to other models.

In summary, our ResNet50 outperforms other models in terms of both loss and accuracy. Therefore, from the perspective of overall training efficiency, our ResNet50 model is superior to other models.

5.2. Comparison of Testing Accuracy and Recall with Classic Models

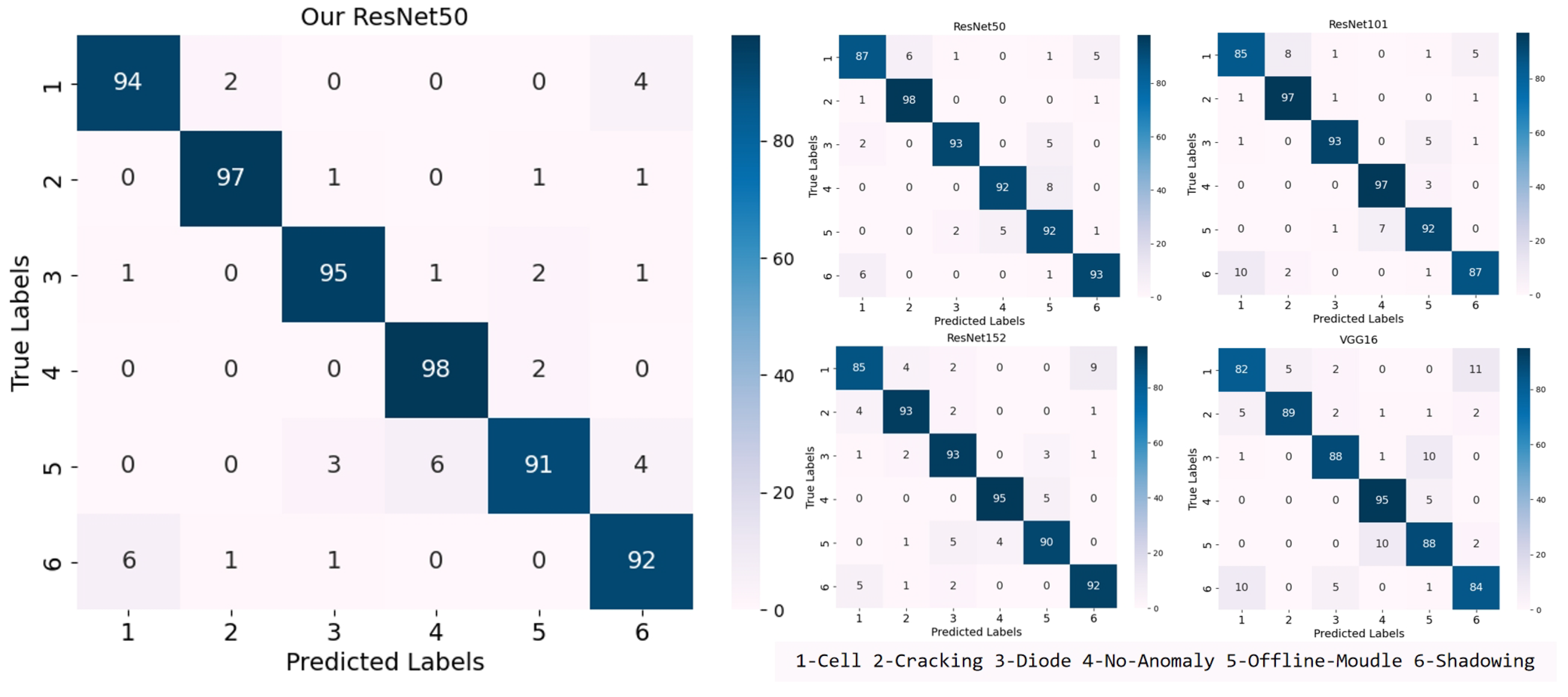

Figure 6 presents the confusion matrices obtained by our ResNet50 model and existing models when performing fault classification on the test set. The vertical axis represents the actual fault types, while the horizontal axis represents the predicted results. The fault types include cell, cracking, diode, offline-module, and shadowing. The depth of color in the corresponding positions of the matrix indicates the number of correctly classified samples. Brighter colors represent a higher number of correctly identified samples, thereby indicating higher model accuracy.

In our experiment, we specifically compared the accuracy and recall of the ResNet50 model with several baseline models. Our ResNet50 model significantly improved performance by integrating new texture features. The introduction of these new features enabled the model to better capture subtle differences when handling photovoltaic module fault detection tasks. In contrast, the baseline models, including ResNet101, ResNet152, and VGG16, retained their original feature extraction mechanisms in the experiment.

These baseline models did not incorporate new texture features but relied on their inherent architectural design for feature extraction and classification. A detailed analysis of the confusion matrix for five types of faults was conducted and evaluated using average precision (AP) and average recall (AR). As shown in

Table 2, our ResNet50 model achieved approximately 94.74% average accuracy and 94.80% average recall in the photovoltaic module fault detection task, demonstrating high classification performance. In comparison, the standard ResNet50 model’s average accuracy and recall were about 92.14% and 92.60%, respectively. The ResNet101 model’s average accuracy and recall were about 91.60% and 90.80%, slightly inferior to ResNet50. Meanwhile, the ResNet152 model’s average accuracy and recall were around 90.42% and 91.00%, showing a slight improvement but still not surpassing ResNet50. Conversely, the VGG16 model’s performance was relatively low, with an average accuracy of 87.22% and recall of 86.2%.

Compared to these traditional models, the proposed method significantly optimized the average accuracy and average recall in the photovoltaic module fault detection task, further enhancing the overall performance of the model.

5.3. Visualization of Classification Results

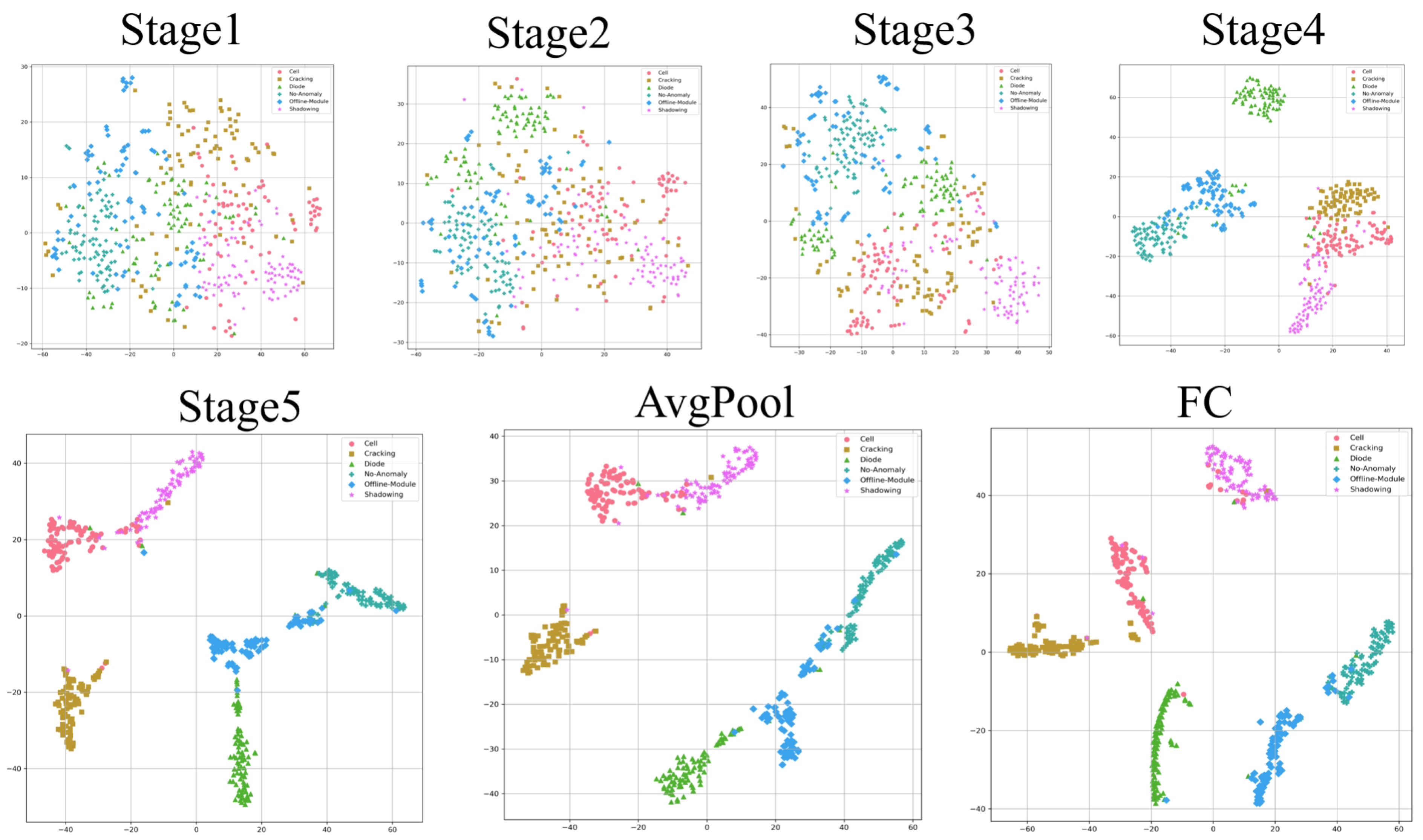

This paper further analyzes the feature classification behavior using the t-SNE algorithm based on the infrared image dataset of photovoltaic modules and the improved ResNet50 model designed in this study. The high-dimensional output prediction data is visualized in a two-dimensional plane.

5.3.1. Observation and Analysis of Feature Evolution at Different Stages

As shown in

Figure 7, we first conducted an in-depth comparison and analysis of the dimensionality-reduced visualizations of features from the stages before the final stage of the model. For this study, a representative feature layer from each stage was selected for visualization and analysis. By observing the feature distributions, we found that in the early stages of classification, the fault data of different categories were distributed in a more mixed manner, with fuzzy boundaries between categories, making precise differentiation challenging. However, as model training progressed, the features were gradually optimized, and the distinctions between different categories became clearer, with a significant improvement in feature representation capability. This process reflects the model’s gradual learning and understanding of data features, showcasing the typical pattern of deep learning models evolving from low-level to high-level features.

5.3.2. Performance Improvement and Clustering Effect Analysis with the Addition of Texture Features

The introduction of texture features effectively enhanced the model’s ability to represent high-order features. In the feature space visualization analysis, although inter-class feature overlap still existed in the output of the average pooling layer, the non-linear transformation applied by the fully connected layer resulted in significantly increased intra-class compactness and inter-class separability in the feature space. Through t-SNE dimensionality reduction and projection, it was clearly observed that the optimized feature space formed category clusters with distinct decision boundaries. Quantitative analysis showed that the fusion of texture features improved the intra-class-to-inter-class similarity ratio (IWCR) from 2.55 to −5.41, with the inter-class similarity in the fully connected layer reaching −0.162, indicating that different fault categories formed oppositional feature distributions in the decision space. Feature space visualization analysis further confirmed that at the average pooling layer stage, although inter-class feature overlap still partially existed (inter-class similarity 0.294), after the transformation by the fully connected layer, the feature space exhibited significant topological structure optimization: intra-class similarity improved to 0.876. This performance improvement demonstrates that the introduction of texture features not only optimized the model’s feature representation capability but also enhanced the accuracy of category differentiation, ultimately achieving a higher level of classification performance.

As shown in

Figure 7, the results indicate that, at the initial stages of classification, fault data from different categories are intermingled and difficult to distinguish. However, after training, the boundaries between different categories gradually become clearer. In the fully connected layer, six distinct category distributions can be observed. Notably, while the clustering results in the average pooling layer still exhibit a certain degree of overlap, the clustering results in the fully connected layer are significantly clearer. This demonstrates that the introduction of texture features in this study has significantly optimized the model’s performance in classification tasks.

6. Discussion

This study builds upon the ResNet50 model and proposes an improved method for photovoltaic module fault classification by incorporating gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) texture features. The proposed model integrates these features in a targeted manner, specifically tailored to the characteristics of photovoltaic module fault data, aiming to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of fault classification using ResNet50. Experimental results demonstrate that the enhanced model, which combines GLCM texture features, achieves significantly higher accuracy in photovoltaic fault classification tasks compared to traditional models. Furthermore, the training efficiency of the proposed model also surpasses that of existing approaches.

Despite these promising results, several areas require further improvement. The experimental data used in this study face standardization challenges due to external factors such as image resolution and lighting conditions, and the model’s adaptability to non-standardized images requires further evaluation and optimization. Moreover, more comprehensive quantitative evaluations are needed to rigorously verify the independent contribution of texture features. To address this, future work will involve comparing GLCM texture features with other features related to photovoltaic faults to mitigate potential bias caused by the effectiveness of a single feature. Additionally, we plan to conduct control experiments incorporating feature concatenation and attention-weighted fusion to verify the superiority of the current feature fusion strategy. Future research may also explore the integration of multi-scale texture feature extraction methods to comprehensively capture the texture characteristics of photovoltaic modules, thereby enhancing classification performance.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This study focuses on the critical issue of fault diagnosis in photovoltaic (PV) modules and proposes an improved classification method based on texture features for PV module fault detection. Building upon traditional texture feature extraction methods, this approach ingeniously integrates deep learning techniques, effectively combining the strengths of texture feature extraction with the powerful learning capabilities of neural networks. By deeply exploring the intrinsic texture features of PV module surfaces, the method achieves more precise identification of subtle differences in module faults, providing robust technical support for accurate fault localization and classification. In this study, the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) is employed to extract pivotal features that characterize the texture of PV modules. Subsequently, the extracted texture features are concatenated with the model for further processing, enabling high-precision fault classification of PV modules. Compared to traditional methods, this approach not only significantly improves the fault recognition accuracy but also demonstrates superior performance in handling challenging fault scenarios.

In terms of experimental performance, the proposed method exhibits remarkable advantages. Extensive testing on a PV module fault dataset shows that the method achieves a significantly higher recognition accuracy compared to traditional approaches, reaching a new benchmark in this field. Furthermore, owing to the computational efficiency of the deep learning model, the proposed method delivers outstanding performance in fault classification speed, meeting the requirements for real-time monitoring and diagnosis.

Despite the research accomplishments in PV module fault diagnosis, there are still aspects that require further improvement. Future work will focus on enhancing the model’s generalization capability in complex and dynamic environments, optimizing the model architecture and training strategies, and exploring multi-scale texture feature extraction to further improve fault diagnosis accuracy and adaptability. These advancements will provide more comprehensive technical support for the intelligent operation and maintenance of PV systems.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Q.M., S.Z. and D.W.; software, Z.F.; validation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.G.; Investigation, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Pioneer R&D Program of Zhejiang Province-China (2025C01177).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qiang Meng and Dou Wang were employed by the company Zhejiang Provincial Energy Group Co., Ltd.; Chenghang Zheng were employed by the company Zhejiang Baima Lake Laboratory Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chouder, A.; Silvestre, S. Automatic supervision and fault detection of PV systems based on power losses analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviria, J.F.; Narváez, G.; Guillen, C.; Giraldo, L.F.; Bressan, M. Machine learning in photovoltaic systems: A review. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrou, F.; Taghezouit, B.; Sun, Y. Improved k NN-based monitoring schemes for detecting faults in PV systems. IEEE J. Photovoltaics 2019, 9, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouleloued, Y.; Kara, K.; Chouder, A. A Developed Algorithm Inspired from the Classical KNN for Fault Detection and Diagnosis PV Systems. J. Control Autom. Electr. Syst. 2023, 34, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.W.; Li, G.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, X.; Khaliq, A.; Faheem, M.; Ahmad, A. CNN based automatic detection of photovoltaic cell defects in electroluminescence images. Energy 2019, 189, 116319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanakas, J.A.; Ha, L.; Buerhop, C. Faults and infrared thermographic diagnosis in operating c-Si photovoltaic modules: A review of research and future challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanaiah, P.; Sathyanarayana, P.; GuruKumar, L. Image texture feature extraction using GLCM approach. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ul-Haq, A.; Sindi, H.F.; Gul, S.; Jalal, M. Modeling and fault categorization in thin-film and crystalline PV arrays through multilayer neural network algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 102235–102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Dhimish, M.; Titarenko, S.; Mather, P. Artificial neural network based photovoltaic fault detection algorithm integrating two bi-directional input parameters. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 1272–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, D.; Zhu, S. Fault diagnosis method of photovoltaic array based on support vector machine. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 5380–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; He, S.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, W. Wavelet packet and support vector machine analysis of series DC ARC fault detection in photovoltaic system. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2019, 14, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guan, X. FSR-SSL: A fault sample rebalancing framework based on semi-supervised learning for PV fault diagnosis. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 2667–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Lou, Z.; Yan, W. Deep learning based module defect analysis for large-scale photovoltaic farms. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2019, 34, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitsch, S.; Christlein, V.; Berger, S.; Buerhop-Lutz, C.; Maier, A.; Gallwitz, F.; Riess, C. Automatic classification of defective photovoltaic module cells in electroluminescence images. Sol. Energy 2019, 185, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciani, G.; Simione, G.; Vergura, S. Thermographic analysis of photovoltaic panels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’10), Granada, Spain, 23–25 March 2010; pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Su, B.; Chen, H.; Liu, K.; Liu, W. RCAG-Net: Residual Channelwise Attention Gate Network for Hot Spot Defect Detection of Photovoltaic Farms. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3510514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudro, R.A.M.; Nur, K.; Sohan, M.F.A.A.; Mridha, M.F.; Alfarhood, S.; Safran, M.; Kanagarathinam, K. SPF-Net: Solar panel fault detection using U-Net based deep learning image classification. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1580–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanth, J.J.; Venkatesh, S.N.; Sugumaran, V.; Mahamuni, V.S. Enhancing Photovoltaic Module Fault Diagnosis with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Deep Learning-Based Image Analysis. Int. J. Photoenergy 2023, 2023, 8665729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.C.; Lu, J.H. Using UAV to Detect Solar Module Fault Conditions of a Solar Power Farm with IR and Visual Image Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, W.; Min, X.; Wang, T.; Lu, W.; Zhai, G. Distinguishing Computer-Generated Images from Photographic Images: A Texture-Aware Deep Learning-Based Method. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), Suzhou, China, 13–16 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethikim, N.; Nguyentrang, T.; Vovan, T. A new image classification method using interval texture feature and improved Bayesian classifier. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 36473–36488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Abreu, E.; Florindo, J. Texture image classification based on a pseudo-parabolic diffusion model. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 3581–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.; Uma, V. Deep Learning based Feature Extraction for Texture Classification. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Li, J.; Hu, S. Texture feature extraction using ICA filters. In Proceedings of the 2008 7th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, Chongqing, China, 25–27 June 2008; pp. 7631–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Feng, J.; Liang, L.; Zheng, L.; Wu, Q. Multiscale Sampling Based Texture Image Classification. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2017, 24, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Jia, K.; Wang, Q.; Ji, F.; Cao, B.; Qi, J.; Zhao, W.; Yan, K.; Wang, G.; Xue, B.; et al. A texture feature extraction method considering spatial continuity and gray diversity. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, O.; Deshpande, P. Texture-Based Classification to Overcome Uncertainty between COVID-19 and Viral Pneumonia Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Gao, L.; Hua, R.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y. Fine-grained image recognition method for digital media based on feature enhancement strategy. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 2323–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Zang, Y. Image Classification Based on Low-Level Feature Enhancement and Attention Mechanism. Neural Process. Lett. 2024, 56, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siar, M.; Teshnehlab, M. A combination of feature extraction methods and deep learning for brain tumour classification. IET Image Process. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichandi, S.; Balasubramanian, G.; Chakrapani, V. Hybrid deep models for parallel feature extraction and enhanced emotion state classification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, A.; Yıldırım, M.; Eroğlu, Y. Classification of pneumonia cell images using improved ResNet50 model. Trait. Signal 2021, 38, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Chen, C. Modulation Pattern Recognition Based on Resnet50 Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information Communication and Signal Processing (ICICSP), Weihai, China, 28–30 September 2019; pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Ali, N.; Ahmed, J.; Zafar, B.; Rasheed, A.; Sajid, M.; Ahmed, A.; Dar, S.H. Satellite and scene image classification based on transfer learning and fine tuning of ResNet50. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5843816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |