Abstract

Buildings consume energy and are responsible for a significant portion of greenhouse gas emissions in Australia. Increased standards are being set for building thermal performance. Given the rising demand for energy-efficient housing solutions, this work explores the potential application of innovative technologies to enhance the thermal performance. Since modular construction is attracting popularity owing to numerous advantages, including its efficiency and cost-effectiveness, optimising the thermal performance is a way to further improve its popularity, particularly in diverse Australian climates. Smart materials are unique and have desirable properties when subjected to a change in the external environment. Integration of smart insulation materials in prefabricated buildings forecasts a potential to expand the horizon of thermal performance of prefabricated buildings and subsequently lead towards an enhanced energy performance. This work investigates the effects of aerogel, phase change materials (PCMs), and electrochromic glazing. To assess their potential to improve the thermal performance of a modular house, building energy performance simulations were conducted for three different climatic conditions in Australia. Individual implementation of innovative technologies and their combined effects were also quantified. The combination of the three innovative technologies has yielded total annual energy savings of 15.6%, 11.2%, and 6.1% for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane, respectively.

1. Introduction

Global energy consumption has been rising exponentially since the Industrial Revolution, with most of this demand being fulfilled by fossil fuels [1]. Since 2010, global energy consumption has nearly doubled its average growth rate, reaching approximately 8.92 Gtoe per year. It was predicted to increase by up to 60% by the end of 2020 [2]. The growing global population, along with the rising living standards, will lead to a significant increase in the demand for energy consumption by 2050, and conventional energy sources will not satisfy these elevated demands [3]. Among the numerous sectors contributing towards the increasing global energy demand, the leading single contributor is the building sector [4].

As per the Australian energy consumption statistics, Australia’s energy consumption increased 2.0% during the period from 2022 to 2023, reaching 5882 PJ, which reflected an increase of 117 PJ [5]. Owing to the climatic conditions and people’s lifestyle patterns in the country, energy consumed by residential buildings accounts for a substantial proportion of the total energy consumption. Approximately 24% of the total electricity use is consumed by residential buildings in Australia, with poor-performing houses and apartments significantly influencing these elevated energy consumption rates [6,7,8]. In buildings, a substantial portion of energy is dedicated to heating and cooling to achieve a comfortable indoor environment. The energy used for heating and cooling can account for a significant share of total energy consumption, ranging from 18% to 73% [9]. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the census on housing indicated that the housing cluster of Australia is composed of 70% separate houses, 13% townhouses, and 16% apartments [10]. As public concern grows about climate change and sustainable living, people are more aligned towards sustainable dwellings, switching from high energy-, labour-, and cost-intensive conventional houses. With this trend, modular houses have flourished in the construction sector of Australia, and the prefabricated building market size is estimated at USD 10.27 billion in 2024. It is expected to expand up to USD 13.06 billion by 2029, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 4.93% for the forecast period of 2024–2019 [11,12,13]. In contrast with traditional on-site construction, modular construction can be regarded as an off-site construction approach, where fully furnished volumetric units fabricated in a factory environment are transported and assembled at the construction site [12]. Several off-site construction categories have been identified as components, panels, pods, modules, complete buildings, and flat pack (foldable structures) [14]. Shorter construction time, reduced disruption to the human and natural environment [15], waste and energy reduction, higher quality, productivity, enhanced safer working conditions, and contribution towards the circular economy because of convenient disassembly and potential reuse of parts are several promising benefits served by adopting this technology.

Amidst the numerous benefits offered by prefabricated houses, traditional prefabricated homes persist in the potential for further energy efficiency and thermal performance enhancement [16,17]. Although the reduced weight of prefabricated houses due to fewer materials used in the building envelope tops the list of advantages served by prefabricated houses, it leads to high thermal conductivity and less thermal inertia of the envelope [18,19]. With large-panel prefabricated buildings, some observe that they display inadequate thermal performance, even though their building envelope is equipped with thermal insulation [20]. Low thermal insulation of large-panel prefabricated buildings resulted in a lack of thermal comfort, fungal problems, and rising heating costs for flat users [21]. In another study [19], it has been found that in terms of long-term occupation of prefabricated houses, the indoor thermal environments are severely unacceptable with high daytime temperatures and low nighttime temperatures. Loss of heat at the joints of the prefabricated houses is another factor contributing to the poor thermal performance of prefabricated houses. With the rising demands for improved thermal properties in prefabricated buildings, thicker insulation and enhanced contact systems have become a requisite for prefabricated houses. Another study has discovered that window glazing and shading are the most influential parameters on energy use, thermal comfort, and daylighting levels in prefabricated houses [22].

To negate the shortcomings associated with prefabricated houses in terms of thermal performance, it is crucial to optimise the building envelope. The building envelope and the building materials play a crucial role in regulating the indoor temperature, which subsequently affects the energy demands [23]. In this context, insulation materials within the building envelope serve a vital role. Fibreglass, mineral wool, polystyrene, and polyurethane are a few types of conventional insulation materials utilised in the industry [24,25]. These traditional insulation materials cause detrimental effects on the environment because of their non-renewability and high consumption of fossil fuels during production [26]. Traditional insulation materials, such as mineral wool and expanded polystyrene, present several drawbacks, including susceptibility to perforation, challenges despite adaptability, limitations in mechanical strength, concerns regarding fire safety, and negative environmental effects [27]. Expanded polystyrene and polyurethane possess elevated thermal conductivities and are characterised by their fragility and susceptibility to perforation [28]. Adverse environmental impacts during the production stage of traditional insulation materials contribute to a higher carbon footprint and negative environmental consequences [29]. More specifically, the use of these traditional insulation materials in prefabricated buildings has been a focus of rigorous evaluation. However, because of these numerous shortcomings, attention has been drawn towards innovative materials as futuristic materials to enhance environmental sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and security, etc., pertaining to the construction industry.

In the progression of building material advancement, smart materials represent a transformative category of materials with the capability of dynamically responding to different external stimuli. Prominent examples of these external stimuli include light, temperature, moisture, electric field, and magnetic field. These innovative materials are characterised by five fundamental characteristics: immediacy—the ability of innovative materials to respond in real-time, transiency—the ability to respond to more than one environmental state, self-actuation—the intelligence property is internal to the material rather than external, selectivity—response of innovative materials is discrete and predictable, and directness—the response is local to the activating event [30]. Innovative materials are described as man-made or natural materials that produce desirable properties when there are environmental changes around them [26]. Numerous definitions of smart materials have been articulated, and, as a result, these are classified broadly, reflecting their diverse characteristics and inherent benefits. According to Mohamed et al. [30], the taxonomy of smart materials is classified under two categories, based on smart material characteristics and types of smart materials. Bahl et al. [26], highlighted that smart materials are primarily categorised as active and passive. Passive materials display the ability to transfer a type of energy. Active materials are further divided into two types, Type 01 and Type 02, where Type 01 materials cannot change their properties when exposed to external stimuli. Type 02 materials possess the capability of altering from one form of energy to another. In the domain of smart materials, smart insulation materials used in the building industry attract significance as they offer a transformative opportunity to address the drawbacks of the thermal performance of prefabricated houses. Recent studies on smart materials consistently highlight their potential to enhance the thermal performance of residential buildings. However, in the Australian context, the use of smart materials to enhance thermal performance is predominantly seen in conventional detached housing models. Individual smart solutions have been considered in these studies, while limited studies have focused on the potential of adopting combined smart materials. Hence, no study to date has combined smart materials to enhance the thermal performance of Australian prefabricated houses. Therefore, this unexplored research gap presents a need to be evaluated to enhance the thermal performance of prefabricated houses in Australia.

Hence, this work evaluates the potential for thermal performance enhancement of prefabricated houses in Australia by incorporating innovative technologies that apply smart materials. A comparative analysis based on the building energy performance simulations was executed for the work. The work intends to provide insight into the applicability of innovative technologies in prefabricated houses to enhance the occupant’s thermal comfort and the building’s energy performance. Given the rising popularity of prefabricated houses in Australia, integrating innovative technologies can set a benchmark for future developments, whilst also serving as an alternative adaptive strategy to address the challenges faced because of Australia’s varied climate conditions. This would further be an approach towards meeting Australia’s new energy efficiency requirements. The details of the methods employed, selected innovative technologies that use smart materials, climatic conditions of the selected locations of Australia, findings of the comparative analysis, and conclusions are presented in the following sections.

2. Methods

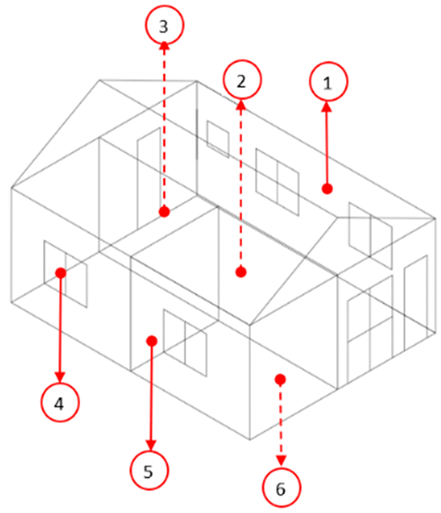

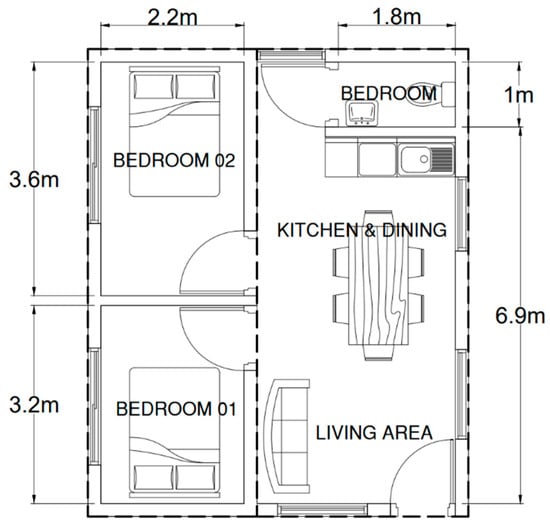

This work was conducted with the prime aim of determining the efficiency of incorporating innovative technologies into the building envelope of prefabricated houses in Australia. Hence, an explicit analysis was performed by conducting a series of thermal simulations for a selected modular house. A single-storey typical modular house (Figure 1) comprising two modular units of sizes 7.2 m × 2.65 m × 3.0 m and 7.2 m × 2.95 m × 3.0 m, accommodating two bedrooms, a living area, a kitchen, and one bathroom, has been selected for this work. This modular house was selected from the study by Munmulla et al. [15]. Concrete was considered the main generic material type for modular construction. Initially, a base case modular house was modelled and simulated under three selected climatic conditions of Australia: Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane. The specifics of the selected climatic conditions will be discussed in subsequent sections. The models were validated by comparing the results from Aye et al. [31].

Figure 1.

Layout of the prefabricated house.

Following the base case model development, the building envelope of the base case house was modified by incorporating the selected innovative technologies. The thermal performance of each modified model was assessed by conducting a series of building energy performance simulations using DesignBuilder software (v 4.0) for the selected cities across Australia. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using varying parameters to optimise the adaptability of innovative technologies in the prefabricated building envelope. The parameters considered include the building type, the type of building element that incorporates materials, the materials, the location, and the thickness. These selected variables and different parameter combinations are summarised in Table 1. Initially, each selected smart material was incorporated into walls, roofs, and windows separately for the prefabricated house in each selected city of Australia.

Table 1.

Variables considered for the sensitivity analysis.

2.1. Model Development

The selected modular house was modelled using DesignBuilder software [32]. The material combinations described above were considered for the construction template. General domestic residential building templates were considered for the activity templates for each simulation. The details of the construction materials and the relevant material properties used for the development of the base case model are stated in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. The heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system operated according to the defined schedules for each domestic residential unit. To represent the internal loads, the equipment power density and lighting power density were set as 3.58 W m−2 and 3 W m−2, respectively. Split and mechanical ventilation systems were considered for the HVAC system, and the fuel for both cooling and heating systems was regarded as electricity from the grid with an average coefficient of performance (COP) of 3.0 for heating and 2.2 for cooling. Mechanical ventilation provides fresh air at a rate of 3 air changes per hour (ACH). The indoor temperature set points were maintained at 21 °C and 24 °C for all the locations considered for the work.

Table 2.

Construction details of the base case prefabricated house (from inside to outside layer).

Table 3.

Properties of the building envelope materials [32,33].

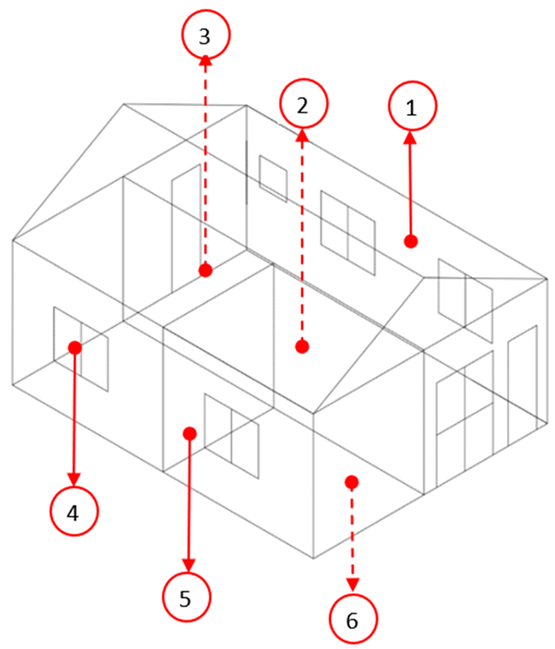

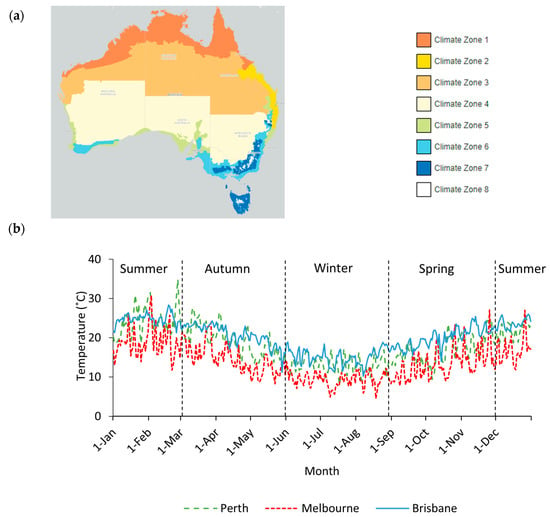

2.2. Climate Data

The entire process of building energy and thermal comfort is critically governed by the key input of site weather data. The thermal comfort and energy performance of a building vary with the location of the building because of the varied weather in the environment. Because of Australia’s diverse climate conditions, the demand for cooling and heating fluctuates accordingly. Australia is zoned under eight different climate zones (Figure 2a). Hence, to evaluate the efficiency of using innovative technologies in prefabricated houses under different climatic conditions, three cities in Australia, Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane, with distinct weather, were selected for this work. Future population growth rates, urbanisation, and migration trends are the main reasons for prioritising these three cities. Rapid population growth and urbanisation create a pressing need for affordable, innovative housing solutions, making prefabricated houses an attractive option in the Australian housing market. The selection of these three distinct cities for the study was based on their representation of major climate categories relevant to Australia. According to the Australian climate zone classification, Melbourne is classified under climate zone 06 with a mild temperature, and Perth is classified under zone 05 with a warm temperature. Warm, humid summers and mild winter weather can be observed in Brisbane, which is classified under climate zone 02. The Australian building stock is widely distributed across these three climate types; therefore, the selected three cities provide sufficient climatic coverage for assessing the applicability of these selected smart materials and innovative technologies in prefabricated houses in Australia. The ASHREA/WEC climate zones of Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane are 3C, 3A, and 2A, respectively. The outside dry-bulb temperature variation is presented in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

Climate data in Australia: (a) Climate zone map of Australia (Source: Australian Government, 2025 [34]); (b) Outside dry-bulb temperature variation (Source: DesignBuilder software Australia [32]).

3. Selected Innovative Technologies

The present work has been conducted with the intention of providing an insight into the potential of incorporating smart materials in prefabricated houses in Australia to enhance their thermal and energy performance. With the availability of numerous smart materials, the selection of potential smart materials from the cluster is crucial. The selection of innovative technologies for this work has been performed considering key factors, including relevance for energy efficiency, performance in diverse climates, compatibility with prefabricated construction, innovative and more sustainable building practices, and potential for future development. Hence, phase change material (PCM), aerogel blanket, and electrochromic glazing were selected. Of the two categories of smart materials, the aerogel blanket functions as a passive insulator, while the electrochromic glazing can be regarded as an active system because of the adjustability of thermal and optical properties through low-power electrical control. PCMs operate as a hybrid passive-dynamic system as they regulate the indoor temperature by storing and releasing heat. Hence, their selected materials align with the categories defined in the smart materials domain. For the sensitivity analysis of the selected innovative technologies, PCM thickness, melting point, and aerogel layer thickness were considered. The selection of these parameter values was based on the product availability, installation practicality, and relevant recommendations provided in the literature. For the PCMs, the layer thicknesses available in the market and reported in the literature range from 2 mm to 25 mm [35,36,37]. The melting point temperatures of PCMs were selected between 21 °C and 28 °C based on the values reported in previous studies [36,38]. Similarly, for the aerogel blanket thickness varied from 10 mm to 25 mm, product availability and installation capabilities were considered [39].

3.1. Phase Change Materials (PCMs)

Phase change materials absorb, accumulate, and release a large amount of energy as heat when the material changes its state from solid to liquid [40]. These are classified into three categories: organic, inorganic, and eutectic. Organic PCMs encompass paraffin and non-paraffin compounds, while inorganic PCMs comprise salt hydrates and metallics. Eutectic PCMs represent a combination of two or more components, each of which melts and freezes congruently, forming a mixture of the component crystals during crystallisation [40]. Because of the capability of storing heat induced by solar radiation, PCMs display a significant potential to enhance the energy efficiency of buildings [41,42]. The mechanism of enhancing the energy performance by PCMs is composed of a two-way process. During the daytime, PCMs integrated into the building envelope absorb heat from solar radiation, resulting in a reduced cooling load. The heat stored during the daytime is dispensed at night when the air turns cold. Dispensing heat involves the freezing process of PCMs. This release of stored energy to the internal and external environment results in reducing the heating energy of buildings [43,44].

Owing to the significant energy performance of PCMs, this material has been incorporated into the building envelope of conventional buildings since 1980 [45]. Table 4 summarises several applications of PCMs in conventional buildings. PCM as an insulation material has been incorporated into various elements in the building envelope, including the roof, wall, and floor. This has resulted in reducing the cooling and heating energy demands in significant proportions, given that these proportions have varied with the climate conditions of the selected buildings. Based on the results, PCM has displayed the potential of reducing the temperature by 1–2 °C and cooling and heating demands by 10–50% on average.

Table 4.

Applications of PCM in building elements as insulation materials.

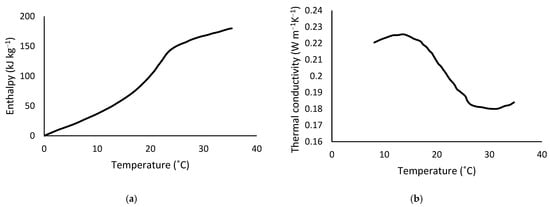

However, until now, no study has evaluated the potential of enhancing the building envelope of modular houses in Australia by incorporating PCMs. In the present work, the ‘Energain’ PCM board produced by DuPont was considered [54]. This material is composed of 60% paraffin microcapsules. The melting temperature, latent heat of fusion, density, and specific heat capacity are 21.7 °C, 70 kJ kg−1, 855 kg m−3, and 2500 J kg−1 K−1, respectively [36,54,55]. The enthalpy and thermal conductivity of the PCM with respect to temperature are represented in Figure 3 (reproduced from [54]).

Figure 3.

Properties of the ‘Energain’ PCM board: (a) enthalpy vs. temperature; (b) thermal conductivity vs. temperature (reproduced from [54]).

3.2. Aerogel

Aerogel is an ultralight synthetic material with a porous nature [56]. Although this material is derived from gels where the liquid component of the gel is replaced with a gas constrained in nanoscale cavities, it is a dry and rigid material in its physical state [2]. Base materials such as Alumina, Carbon, Chromium, Silica, and Tin Oxide are used in the production of aerogels [57,58,59,60]. Several types of aerogel end products are distinguished based on their synthesis procedure; namely, monolithic aerogels, granules or powdered aerogels, which are collectively referred to as divided aerogels, and composite aerogels [61]. However, the commercial availability of each of these types of aerogels depends on its respective synthesis process and cost-intensiveness. Owing to the time-consuming synthesis process and high-cost intensity, monolithic aerogels are not widely available in the commercial market [39,61], whereas silica aerogel, aerogel granules, and aerogel boards are widely available because of comparative cost-effectiveness, a convenient preparation process, and reliability [2].

In terms of the properties of aerogels, they are highly porous solid or semi-solid materials having a very low density of around 3 kg m−3 [2,62]. Low thermal conductivity, low density, lowest refraction index, low dielectric constant, extraordinary heat and sound insulation properties, high absorption capacity, bacteria and dust particle capturing nature, non-flammable composition, and recyclability make aerogels a versatile application. Since several aerogel-enhanced materials can display thermal conductivity less than that of air at the ambient temperature, their material types are regarded as super-insulation materials [2]. The thermal conductivity of air is 0.026 W m−1 K−1, whereas these super-insulation materials display a thermal conductivity of 0.02 W m−1 K−1. In the study by Ihara et al. [39], the properties of an aerogel blanket used to enhance the thermal performance of a house are stated. These include a thickness of 20 mm, density of 100–130 kg m−3, thermal conductivity of 0.013–0.023 W m−1 K−1, specific heat capacity of 1000 J kg−1 K−1, and roughness as medium-smooth. These properties were considered for the simulations in this work as well.

3.3. Electrochromic Glazing

Glazing is another option for regulating the energy efficiency and thermal comfort of a building, and electrochromic glazing has been found to be a potential candidate [63,64,65,66,67]. These systems can dynamically adjust the transparency of a glass pane based on external stimuli [63,68]. The electrochromic material, placed between the two panes of a window system, can be changed electrically to control the transparency or opacity levels [69]. Automatic control or operator-controlled transmittance of solar energy and visible light can be used for the controlling process [69]. The energy efficiency in buildings can be increased using electrochromic systems for smart windows with adequate control of the solar radiation penetrating inside the building. The amount of daylight entering a space can be optimised with the configuration of the smart window [70]. It has been identified that electrochromic glazing can reduce the uncomfortable hours of thermal comfort by 50% [71]. Because of its ability to control sunlight, electrochromic glass operates to provide ambient light and prevent heat from escaping into the environment [63]. This function of electrochromic glass contributes significantly to electricity savings, especially in hot seasons. The list of other advantages of using electrochromic glazing in buildings includes protection from harmful rays [72] and the option to choose the colour of the desired glass since this glass can change colour with the change in voltage [63,73]. When compared with other advanced glazing technologies, electrochromic glazing offers multiple benefits in terms of precision and low-power electrical control [74]. As a result, integrating into the building management system is comparatively easy. However, in terms of cost, control hardware, and colourisation issues, it could bring some disadvantages when compared with other advanced glazing technologies such as thermochromic or liquid-crystal systems [74,75]. However, average temperature, relative temperature, day length, daily sunshine, and global horizontal radiation govern the decision of energy optimisation using these smart windows [63]. Hence, the effect of this electrochromic glazing on the energy performance of a prefabricated house under the varying climatic conditions of Australia needs to be evaluated, and the simulation details of the electrochromic window incorporated in the prefabricated house are given in Table 5. The electrochromic glazing type “Dbl Elec Ref Bleached 6 mm/13 mm Air” which was taken from the EnergyPlus dataset embedded in DesignBuilder with a U-value of 1.766 W·m−2·K−1, total solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) of 0.64, visible transmittance of 0.727 and a direct solar transmission of 0.545 in the bleached state was used for the simulation in this work.

Table 5.

Details of the windows used for the simulation.

4. Results and Discussion

This section of the work presents a holistic analysis of the impact of integrating innovative technologies on the energy and thermal performance of prefabricated houses in Australia. The obtained results from the building energy performance simulations are analysed and discussed in terms of heating and cooling energy consumed under three different climatic conditions.

4.1. Effect of PCM as a Wall Insulation Material

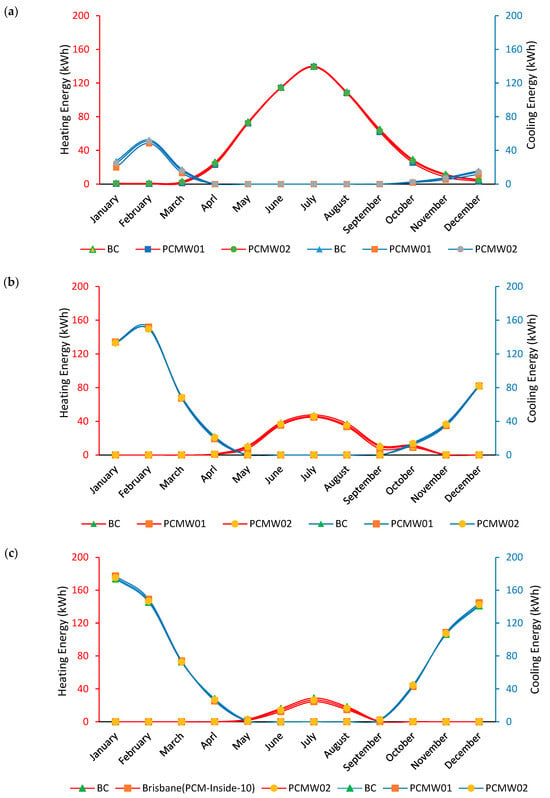

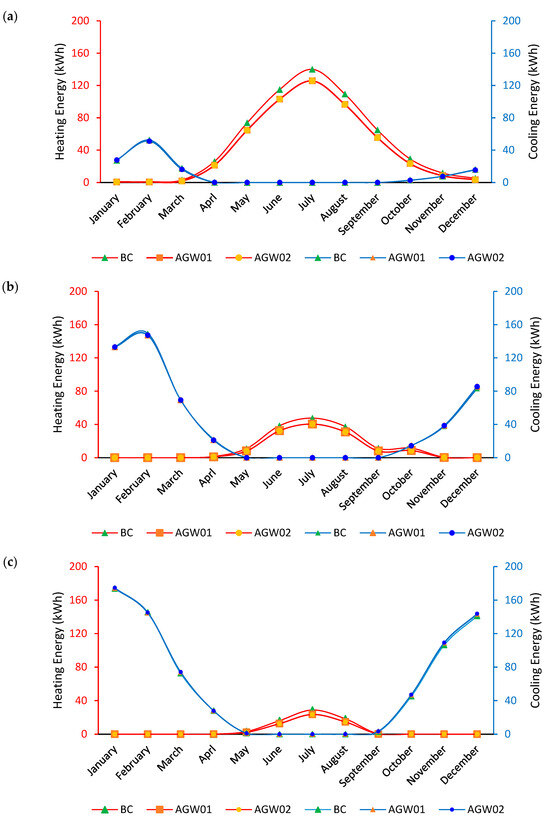

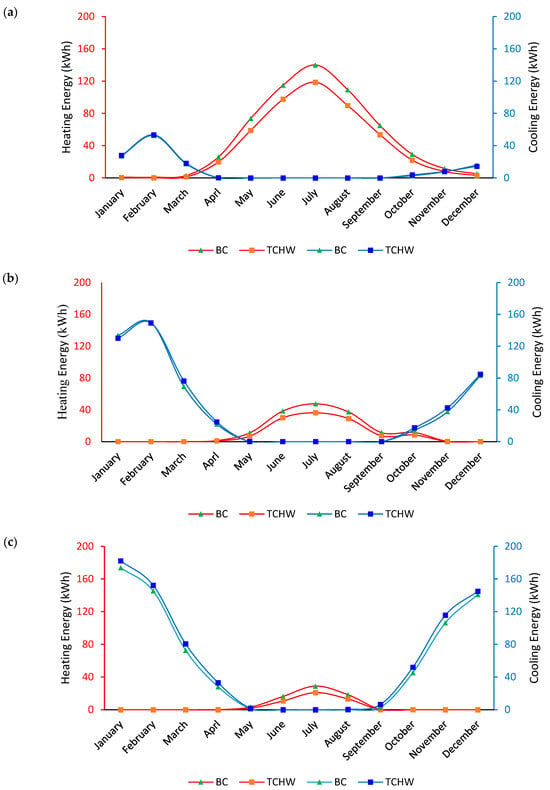

The model house under the base-case scenario was modified by incorporating PCM as an insulation material within the wall panels. Figure 4 depicts the variation in heating and cooling energy loads of the prefabricated house under the climatic conditions of Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane while incorporating PCM. Considering the results obtained for Melbourne, it is noticeable that incorporating the PCM layer has lowered the cooling loads during the hot seasons compared to the base case. However, no significant reduction in the heating loads during the cold seasons was observed. Regarding the cooling load, placing the PCM layer towards the inside of the wall has a greater influence than having the layer placed towards the outside of the wall. During the month of February, in which the highest cooling load was consumed, the cooling load was reduced from 52.5 kWh to 48.4 kWh, indicating a reduction of 7.8% of the cooling load. In contrast, under the climatic conditions of Perth and Brisbane, a significant impact is observed in the consumed heating energy compared with the cooling energy. However, a similar trend to Melbourne’s is observed in the location’s influence on the PCM layer within the inside-the-wall configuration. Placing the PCM layer towards the inside of the wall has resulted in the highest energy reduction compared to the base case. In July, when the highest heating energy was consumed, the heating energy reductions were 5.9% and 15.3% for Perth and Brisbane, respectively. Table 6 describes the details of the PCM-modified wall panels incorporated in the building envelope.

Figure 4.

Effects of PCM placed on the internal side of walls of the prefabricated house in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

Table 6.

Details of the wall layers modified with PCM insulation (from inside to outside layer).

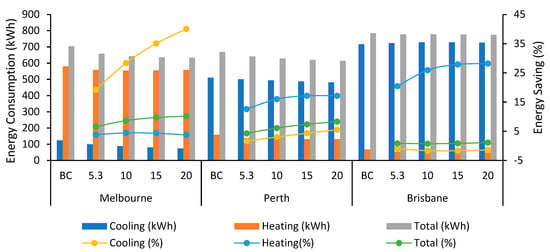

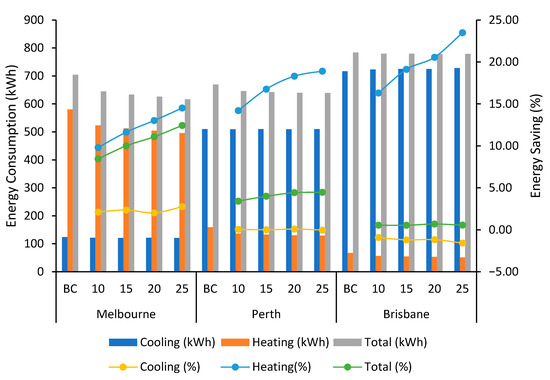

After determining the optimum location of the PCM inside the wall, the influence of the PCM layer thickness on the energy performance of the prefabricated house in each location was evaluated. Wall configurations with a PCM layer located towards the inside of the building and with the PCM layer thicknesses of 5.3 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm, and 20 mm were considered. Figure 5 explicitly presents the cooling, heating, and total energy demands and the percentage of energy saving for each. In Melbourne, with the layer thickness increasing from 5.3 mm to 20 mm, the cooling and heating energies reduced from 100.2 kWh to 74.3 kWh, yielding an energy saving percentage increase from 19.1% to 40.0%. However, heating energy consumption decreased from 557.8 kWh to 554.3 kWh up to 10 mm layer thickness, accumulating as the layer thickness increased from 10 mm to 20 mm. The total energy consumption under the Melbourne climatic condition followed the same trend as that of cooling energy, where the total energy consumption was reduced from 658 kWh to 632.6 kWh with the increase in layer thickness. This resulted in a total energy saving increase from 6.6% to 10.1%. For the prefabricated house in Perth, a gradually decreasing trend was observed for cooling and total energy with the increase in PCM layer thickness. The cooling energy consumption has been reduced from 501.2 kWh to 481 kWh, and the total energy has been reduced from 640.4 kWh to 613.6 kWh. This has accounted for 5.5% and 8.3% energy savings, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effects of PCM layer thickness on energy consumption.

The heating energy consumed is minimal at the PCM layer thickness of 15 mm, and no significant variation has been observed at the layer thickness of 20 mm. The heating energy saving for the 15 mm PCM layer is observed to be 17.2%, which is an increase from 12.6% for the thickness of 5.3 mm. In contrast with the observations for Melbourne and Perth, the cooling energy for Brisbane seemed to increase slightly with the increase in PCM layer thickness. A marginal decrease in total energy consumption was observed with the increase in layer thickness, whereas in terms of heating energy demand, the value has reduced up to 48.18 kWh from 53.4 kWh, which is an energy-saving increase from 20.5% to 28.2%. However, regarding the total energy consumption, the energy saving percentage was trivial with the increase in layer thickness.

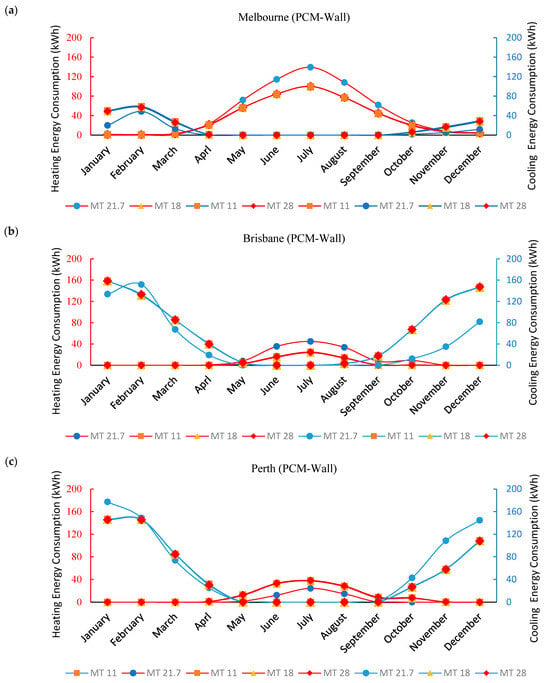

However, the melting temperature of the PCM is another critical factor governing the performance of this material. Hence, the behaviour of PCM with different melting points was also evaluated under the three distinct climate conditions to evaluate the optimal melting temperature desired for each climate condition. Besides the initially considered melting temperature of 21.7 °C, the melting temperatures of 11 °C, 18 °C, and 28 °C were considered for the study. Figure 6 presents the obtained results for these variations. There is a significant reduction in the heating energy consumption in Melbourne and Brisbane, with the change in the melting temperature from 21.7 °C. However, in contrast, cooling energy consumption has shown an increase. For these three climate conditions, which require both heating and cooling, this PCM only reduces the heating loads; hence, PCM with a melting point of 21.7 °C can be used along with another PCM with a different melting temperature from the three evaluated, to obtain optimum results for both heating and cooling load reductions.

Figure 6.

Effects of melting temperature of PCM placed on the internal side of walls of the prefabricated house in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

Besides the properties such as PCM layer thickness and melting point, the fundamental thermodynamic interactions between the PCM and the selected building element are also a critical concern for the variation in these energy demands [76]. The placement of the PCM layer affects charging and discharging. When the PCMs are installed within wall cavities, lateral conductive heat flow governs the heat entering through the wall during the daytime [77]. As a result, the phase-transition process is gradual because of the buffering effect of the wall cladding and other insulation layers [76,77,78].

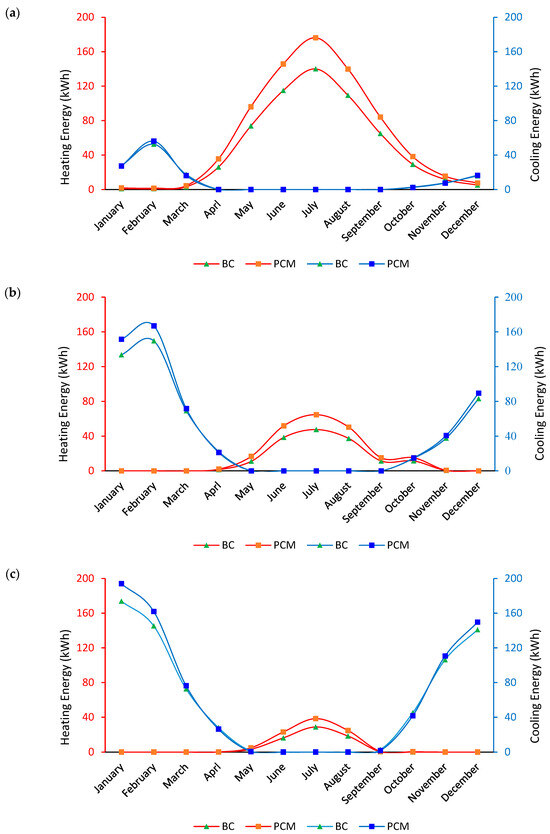

4.2. Effect of Aerogel as a Wall Insulation Material

The analysis was continued using aerogel for wall insulation. The results for the cooling and heating energy obtained when aerogel, as a smart insulation material, is incorporated into the walls of the prefabricated house are presented in Figure 7. The results show that no significant reduction in the cooling energy is observed when incorporating an aerogel blanket under all three climatic conditions. However, incorporating an aerogel blanket as an insulation material has significantly reduced the heating energy demand for all three cities. For July, where the highest heating energy demand is observed, the heating energy savings for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane are 10.2%, 15.2%, and 18.8%, respectively. It is also perceptible that the effect of the location of the aerogel layer on energy consumption in the wall configuration is borderline. Table 7 provides details of the wall configurations modified with aerogel insulation.

Figure 7.

Effects of an aerogel blanket placed on the internal side of walls of the prefabricated house in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

Table 7.

Details of the wall layers modified with aerogel insulation (from inside to outside layer).

Given that the relative location of the aerogel blanket within the wall configuration was found to have minimal impact on the energy consumption of the prefabricated house, further analysis was conducted to assess the effect of the layer thickness. The layer thickness was changed from 10 mm to 25 mm. Figure 8 depicts the influence of aerogel layer thickness on the energy demands and respective energy-saving percentages. The cooling load has not been seen to be significantly affected by the layer thickness under the climatic conditions in Melbourne. However, the heating and total energy savings were noticed to be increasing from 9.8% to 14.5% and from 8.5% to 12.4%, respectively. In Perth, a minor reduction in cooling energy was observed with the increase in layer thickness from 10 mm to 20 mm, and a negligible increase was observed for the 20 mm layer thickness. However, heating, cooling, and total energy followed a similar variation, where the energy demands reduced as the layer thickness increased. The increase in layer thickness from 10 mm to 25 mm increased the total energy saving from 3.4% to 4.5%. Like the effect of PCM, under the climate conditions of Brisbane, the cooling energy and total energy are observed to increase as the layer thickness increases slightly. Heating energy has been reduced from 56.15 kWh to 51.33 kWh, resulting in an energy saving of 23.5%.

Figure 8.

Effects of aerogel layer thickness on energy consumption.

4.3. Effect of PCM as a Ceiling Insulation Material

The effect of incorporating PCM as a roof insulation material was evaluated (Table 8). Figure 9 represents the results obtained for the cooling and heating loads under the three climate conditions considered when the PCM layer is incorporated as an insulation layer. However, the replacement of a 130 mm thick mineral wool insulation layer with a PCM layer of thickness 5.3 mm has not reduced the cooling and heating loads from the respective base case scenarios. Conversely, substantial increases in these loads were observed. In terms of the thicknesses of the two layers, this result is apparent because of the reduced thermal mass associated with incorporating the PCM layer when compared to the thickness of the mineral wool layer. However, the increased energy consumption when the conventional insulation layer is replaced with a 5.3 mm thick PCM layer is not only attributable to the reduced thickness. The conventional insulation layer effectively reduces the rate of heat flow into the indoor environment because of its high thermal resistance, whereas PCM activates heat capacity through latent heat storage. Although PCM absorbs heat during the phase change stage, because of the reduced insulation capacity, heat gains can be higher, leading to increased energy consumption. When the heating and cooling energy demands for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane are considered, a relatively lower energy increase from the base case scenario is observed in cooling loads compared to the heating loads. In Melbourne during February, the month in which the highest cooling energy demand was observed, with the introduction of the PCM layer, only approximately 4 kWh difference was observed in the cooling load. The cooling energy consumption has remained almost the same as the base case throughout the other months in Melbourne. A similar trend has also been observed in the cooling load demand in Perth, where an increase of approximately 17 kWh was observed in January and February. In Brisbane, the highest cooling energy demand was observed in January, and the cooling energy demand increased with the introduction of the PCM by approximately 20 kWh.

Table 8.

Details of the ceiling configurations modified with PCM insulation (from inside to outside layer).

Figure 9.

Effects of the PCM layer placed on the internal side of the ceiling of the prefabricated house in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

However, when the heating energy demand is considered for all three locations, during July, the month in which the highest heating energy demand has been consumed, the energy increase with the PCM layer introduction is 36 kWh, 17 kWh, and 10 kWh for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane, respectively. In contrast with the cooling load demand, this increase in energy demand for heating has also been observed in other months at lower values. In a study by Hasan et al. [79], the use of PCM as a ceiling insulation material has been explored. An experimental study has been conducted with a 100 mm thick paraffin wax PCM layer with a melting point of 44 °C. It has been incorporated into a ceiling panel of a building. The PCM layer is embedded between a sandwich roof panel and an aluminium layer. The results imply that the cooling load has reduced by 6.8% during a peak hour in the daytime. In the study by Hasan et al. [79], additional insulation has been provided by the polyurethane insulation in the sandwich panel. The study by Soares et al. [80] reveals that numerous factors contribute towards the efficiency of PCM’s performance. These factors are the relative location of the PCM layer, the volume and thermophysical properties, the phase-change temperature range, the latent heat capacity, the climatic conditions, internal solar gains, reflectivity and orientation of the surfaces, ventilation rates, HVAC controls, and building structure [54]. Hence, in the present work, although an increase in the cooling load during the hottest months was observed, this can be reasonably justified based on several reasons. The lesser the thickness of the PCM layer considered, the fewer the changes in the material and building properties, etc. However, with a further increase in the thickness of the PCM layer and/or by the addition of another conventional insulation material, the thermal performance can be further enhanced. This is because using a PCM layer of minimum thickness alone has resulted in a close behaviour to the base case thermal behaviour of the considered house. Similarly to the effect of the PCM layers with the wall elements in Section 4.1, it also affects the energy demand for PCM as a ceiling insulation layer [76]. However, in contrast to PCM as a wall insulation layer, when it is applied at the ceiling level, the heat transfer is governed by buoyant indoor air stratification in the vertical upward direction [81]. Hence, during peak cooling hours, warmer indoor air stagnates near the ceiling. As a result, PCM insulation charging could be accelerated, and the heat release capacity at night could be reduced.

4.4. Effect of Aerogel as a Ceiling Insulation Material

The effect of incorporating aerogel as a smart insulation in the ceiling of a prefabricated house was evaluated, altering the location of the aerogel layer in the ceiling configuration (Table 9). The results for the annual cooling and heating demands for the climatic conditions of Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane are presented in Figure 10. A similar variation to incorporating the PCM layer inside the ceiling was observed with an aerogel blanket, where no cooling and heating energy reduction was observed under the three climatic conditions. In terms of the cooling energy demand, approximately similar variation has been observed in all three locations, reflecting that a 20 mm aerogel layer can replace a 130 mm thick mineral wool insulation layer. A slight variation has been observed for the heating energy, where the maximum heating energy consumption, which was observed during July, has highlighted an increase from the respective base case scenarios by approximately 5 kWh, 3 kWh, and 2 kWh, respectively, for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane. These results resemble the potential of enhancing the thermal performance of prefabricated buildings with less thermal mass, which further results in reducing the weight of prefabricated modules.

Table 9.

Details of the ceiling configurations modified with aerogel insulation (from inside to outside layer).

Figure 10.

Effects of an aerogel blanket placed on the internal side of the ceiling of the prefabricated house in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

The study conducted by Bashir et al. [2] showed that the performance of aerogel for tropical climates in Nigeria has been evaluated by incorporating aerogel blankets into the attic and the floor of a house. The results showed a reduction in energy consumption exceeding 15%.

However, in the present work, although the same aerogel material with the same properties has been considered, the results displayed no clear energy reduction (Figure 10). Instead, similar energy demand was observed in the base case scenario. The disparity of these results could be significantly affected by the climate conditions and construction type considered in the study by Bashir et al. [2] and in the present work. In terms of the construction type, Bashir et al. [2] considered a masonry-based tropical housing, whereas the present study focused on a lightweight prefabricated house. Hence, as these prefabricated houses do not contain high thermal mass because of their lightweight structure, when compared with masonry-based tropical houses, the heat gain in prefabricated houses is relatively higher. The contrasting climate conditions of the hot tropical climate with consistent warm temperatures and minor day–night and seasonal temperature variations in Nigeria [2], form the temperate, hot-dry Mediterranean, and humid subtropical climates in Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane, respectively, are critical factors for this result variation. This difference observed in the reduced energy performance of aerogel in this study when compared with the findings reported by Bashir et al. [2] could be attributed to the different thermal capacitance of the envelope materials. The brick and stone have higher thermal mass than the prefabricated building materials. When a high-performance insulation layer, such as an aerogel blanket, is applied in a tropical climate, these materials inherently do not provide thermal inertia to buffer the internal heat gains. Instead, conduction through the building envelope is provided. In lightweight structures, such as prefabricated buildings, where thermal mass is relatively low, any internal heat gains from occupants, equipment, and lighting, or any solar gains and ventilation-related heat ingress, could cause a rapid indoor temperature rise because of low heat capacitance. Studies by Hu et al. [82] and Toldi et al. [83] provide evidence that the thermal mass is a significant factor affecting the peak and accumulated cooling loads. Because of the absence of adequate mass to absorb the heat and/or to dissipate the accumulated heat, the indoor environment follows the instantaneous internal loads. As a result, high cooling energy demands could be observed despite the provided insulation.

The results of the present work imply that the aerogel layer of 10 mm thickness has replaced a 130 mm thick conventional mineral wool insulation layer. Hence, in terms of the functionality of the prefabricated houses, this reduction in the thermal mass leading to the weight reduction in the structure is a merit. With the increase in the aerogel layer’s thickness, the potential for further enhancement of the thermal performance exists.

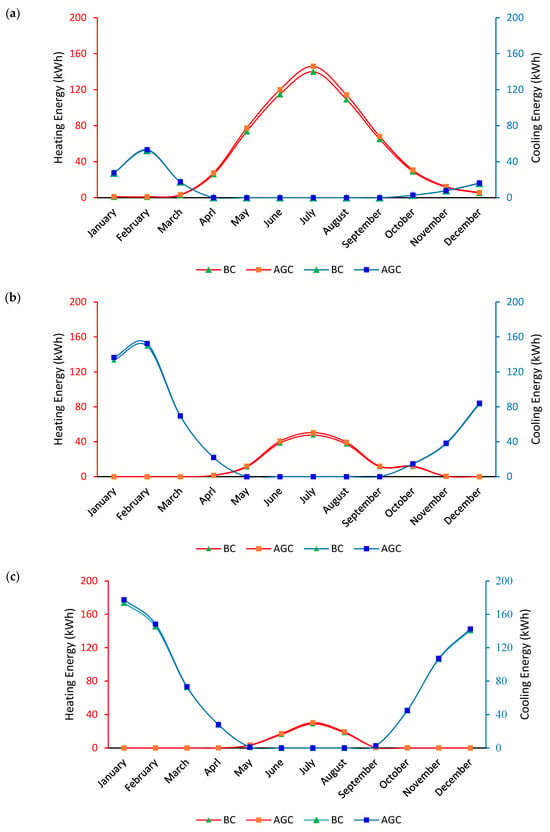

4.5. Effect of Electrochromic Glazing

The contribution towards energy enhancement of a prefabricated house by replacing the generic plain glass with electrochromic glazing material is analysed in this section. Two cases were considered, including the base case (BC) with clear glass and the modified case with electrochromic glazing (ECHW). The results obtained for the monthly cooling and heating energy demands under the three different climate conditions are presented in Figure 11. Regarding the energy efficiency of using electrochromic glazing, it is apparent that the cooling energy demands have not been lowered by replacing plain glazing with electrochromic glazing. Instead, it has slightly increased the annual energy consumed in all three cities. The highest rise in energy consumption is observed in Brisbane, while the lowest is observed in Perth, with a rise of 3% annually. In contrast, the annual heating energy demands were noticed to be significantly reduced in all three cities. Perth, with an annual heating energy saving of 10.6%, displays the highest saving amongst the three cities, with Melbourne marginally ranking second with a 10.5% saving. An annual heating energy saving of 7.2% is observed in Brisbane by incorporating electrochromic glazing. Subsequently, in the cities of Melbourne and Perth, the total annual energy consumption is reduced by 8.9% and 3.8%, respectively, when electrochromic glazing is used in prefabricated houses. However, the replacement of electrochromic glazing does not promise to reduce annual energy consumption. Instead, it has increased the annual energy consumption for cooling and heating by 2.3%.

Figure 11.

Effects of electrochromic glazing of the prefabricated house in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

In the study [65], an electrochromic window has been incorporated into a building facade to enhance its thermal performance. A reduction in the entire building’s annual electrical consumption by up to 3.5% for hot-humid weather was found. The total annual gas consumption of the building was reduced by up to 22.7% for hot and dry weather. Hence, the results obtained in the present work provide a promising approach towards using electrochromic glazing as a potential option for prefabricated houses in Australia.

4.6. Effect of Combined Use of Innovative Technologies

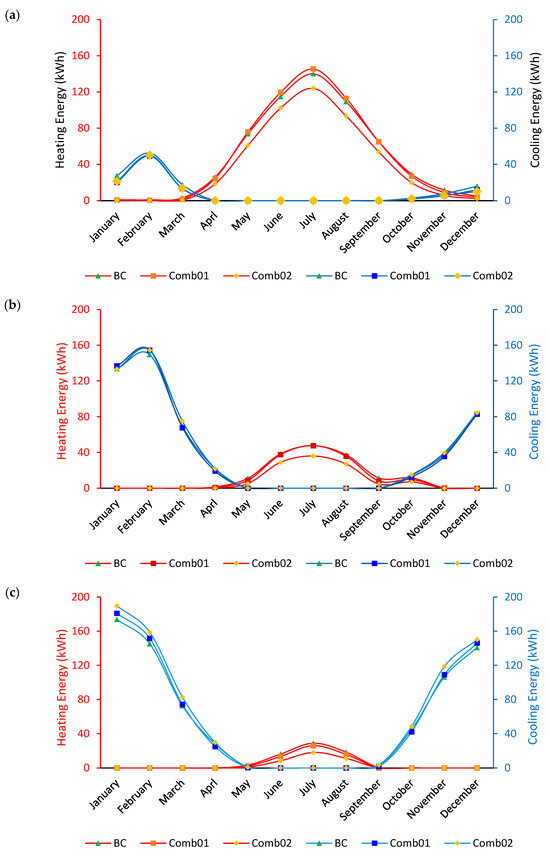

After evaluating the impact of integrating various innovative technologies into each building element of the prefabricated house separately, the potential for performance improvements through the combined use of innovative technologies was further explored.

The impact of the previously obtained results governed the innovative technologies and the layer configuration selection. The PCM located towards the inside of the wall performed more efficiently than the outside wall. When an insulation material for the ceiling is considered, aerogel displays enhanced thermal performance compared to the PCM. Based on these observations, two combinations were considered for further enhancement of the thermal performance of the prefabricated house. Combination 01 incorporated a PCM layer towards the inside of the wall, an aerogel blanket as ceiling insulation material, and a generic window type. In Combination 02, electrochromic glazing replaced the generic window type. Table 10 elaborates on the details of the two combinations.

Table 10.

Details of the combinations.

The results obtained under the above combinations are presented in Figure 12. Overall, the obtained results reveal that further reduction in the total energy consumption could be observed with the combined utilisation of innovative technologies in all three selected cities in Australia. Under Combination 01, the prefabricated house in all three cities demonstrated reduced cooling, heating, and total energy consumption compared to the base case scenario, which employed only conventional insulation materials. For this combination, the highest total energy saving is observed in Perth, which accounts for a total energy saving of 7.67%. Under Combination 01, Brisbane achieved a total energy saving of 6.13%, while Melbourne experienced a saving of only 4.45%. For Melbourne and Perth’s climatic conditions, this energy saving has been further improved under Combination 02, which includes electrochromic glazing. However, while the total energy savings have improved for Brisbane’s climatic conditions compared to the base case, they remain lower than those achieved with Combination 01. Amongst the two combinations, Combination 02 proves to be the optimal option for energy performance in Melbourne and Perth’s climate conditions. However, for Brisbane’s climatic conditions, Combination 01 appears to be more promising than Combination 02 in terms of energy performance. When the heating energy utilised for the optimum combination is considered as a measure of the total floor area (28.56 m2), in Melbourne, the most-efficient combination yields 16.8 kWh m−2 of heating energy saving. In Perth, which reflects strong diurnal temperatures due to a hot-dry climate, the heating energy value achieved is 3.8 kWh m−2 for the optimum configuration. In Brisbane, as the climate is influenced by both solar gains and humidity, the heating energy yielded 1.3 kWh m−2.

Figure 12.

Combined effects of the three innovative technologies in prefabricated houses in: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

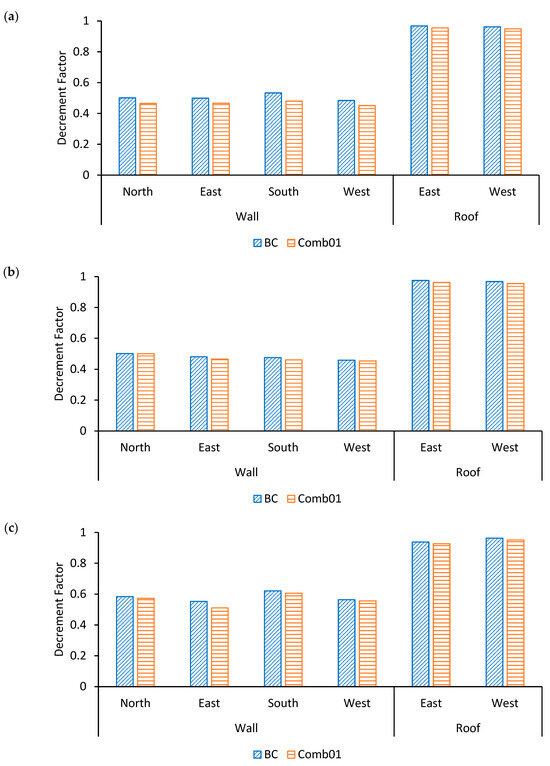

Given the high cost associated with smart materials, it is crucial to optimise their use in prefabricated buildings. Therefore, the thermal decrement factor is a key metric that offers insight into how the building envelope can be further optimised using these selected innovative technologies. The key aspect of thermal comfort is maintaining a consistently desirable indoor temperature despite the fluctuations in the outdoor temperature. The building envelope damps this temperature fluctuation, and the decrement factor for a given building envelope is defined as the ability to attenuate the amplitude of the outside temperature to that of the inside. To assess the temperature-damping potential of the building envelope of the prefabricated house modified with innovative technologies, decrement factors (f) with respect to building orientation were calculated using Equation (1) [84].

where TI-max, TI-min, TO-max, and TO-min represent inside maximum, inside minimum, outside maximum, and outside minimum surface temperatures, respectively.

Figure 13 shows the variation in decrement factors for the prefabricated house under Combination 01 at each location relative to building orientation. The roof has displayed higher decrement factor values because of the greater exposure to solar radiation compared to the walls. The reduction in thermal decrement factors in Combination 01 has been influenced by the addition of thermal mass and the respective heat transfer properties of each material. However, a marginal variation in thermal decrement factors concerning the orientation of the prefabricated house under each climatic condition was observed. Because of the temperate oceanic climate conditions in Melbourne, characterised by cool winter and warm summer periods, walls facing north have the maximum solar gains, east- and west-facing walls have moderate solar gains, and walls facing south have the minimal solar gains. According to the decrement factor variation in Melbourne, west-facing walls and north-facing walls are attributed to the lowest and highest decrement factors under the base case scenario. With the thermal enhancement under Combination 01, these decrement factors have further reduced from their respective base case values. The highest reduction of 9.9% is observed on south-facing walls, followed by the north-facing walls with a reduction of 7.2%.

Figure 13.

Decrement factors for: (a) Melbourne; (b) Perth; and (c) Brisbane.

Under the Mediterranean climate with hot-dry summer and mild-wet winter periods in Perth, maximum solar gains will be received by north-facing walls and minimum by the south-facing walls. However, according to the thermal decrement factor variation in Perth, the highest reduction is observed in south- and east-facing walls, which accounts for a reduction of 3.1%, and the lowest reduction in the thermal decrement factor is observed in the north-facing walls when compared with the base case. Hence, with the influence of the high solar gains by north-facing walls, the variation in the thermal decrement factors implies that the north-facing walls shall be insulated more than the other directions. A humid subtropical climate with humid summers and mild winters is observed under Brisbane’s climate conditions. Like Melbourne and Perth, north-facing walls receive the maximum solar gains. In terms of the thermal decrement factor variation in Brisbane, the highest reduction in the thermal decrement factor from the base case scenario is observed in east-facing walls with a reduction of 7.7%. South-facing walls are second with a reduction potential of 2.4%, with north-facing walls with 1.8%. Hence, like under previous conditions, north-facing walls can be prioritised regarding thermal insulation to further enhance the house’s energy performance.

The decrement factor is directly affected by the building orientation, as the building orientation changes the amount and timing of solar radiation falling on the building envelope. In Australia, north- and west-facing building elements typically receive higher solar gains in the afternoon. This could affect the charging-discharging behaviour of PCMs. Sun-exposed orientations and higher daytime heat gains could cause the effective reach of the PCM melting point while enabling heat storage for a prolonged period. Hence, significant reductions in cooling loads can be expected. This behaviour could be opposite in elements facing the south direction because of limited solar gains. For the aerogel blanket, heat ingression regulation could be more effective in the north and west directions due to the elevated temperature gradient compared with other directions. A similar performance can be expected from electrochromic glazing, where west-facing windows are more effective because of the elevated temperature gradient. Overall, these material behaviour variations with building orientation resemble the orientation-dependent heat gain patterns reflected by the decrement factors.

5. Limitations

In terms of the principal hypothesis and modelling, there are some limitations in this study. The study adopted a constant indoor set-point temperature throughout all simulations. Hence, it may not reflect the full range of occupant behaviour and comfort in real dwellings. The combined behaviour of PCM, aerogel, and electrochromic glazing could vary with complex variables such as occupant schedules, dynamic ventilation strategies, or mixed-mode operation. However, these variables were not explored in the study. The material degradation potential of smart materials was also not explored in this study. Since the study focused on three major climate zones in Australia, the study can be further expanded, considering the other climate regions in Australia as well.

The previous analysis presents the potential of using PCM, aerogel blankets, and electrochromic glazing as potential smart materials to enhance the energy performance of modular buildings in Australia. However, one of the critical constraints that could limit the widespread adoption of these materials in modular buildings is their high costs. Owing to factors such as advanced manufacturing processes, specialised installation requirements, and limited market availability, the upfront cost of these materials and technologies could be relatively high. The typical cost values for these materials in the Australian market are approximately AUD 55–110 m−2, AUD 50 m−2, and AUD 350 m−2 for PCM, aerogel, and electrochromic glazing, respectively [85,86,87]. These values resemble the high initial cost compared with conventional materials. Therefore, evaluating the economic feasibility of these materials and technologies before adopting them in the energy enhancement of modular buildings is crucial. Assessments that consider both initial capital cost and long-term operational benefits shall be conducted to ensure that incorporating these materials in modular buildings to enhance the energy performance is both technically and economically effective.

To confirm the applicability of these selected innovative technologies to enhance the energy performance of prefabricated houses, it is vital for these results to be validated using experimental programmes. However, in this study, the scope does not completely cover the experimental validation, although the simulation outputs are validated in reference to the published experimental studies. However, these limitations do not curtail the findings presented in this study but highlight further opportunities to broaden this research area in future investigations.

6. Conclusions

The work was conducted to analyse the potential for energy performance enhancement of a prefabricated house where the building envelope elements are improved with innovative technologies. A comparative analysis using the building energy performance simulation results obtained from the DesignBuilder software was executed for the work. The analysis was conducted under three different climatic conditions in Australia (Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane). Several variations, including the performance under individual building envelope element modification and their combinations, were considered in this work. The innovative technologies considered for the work were PCM thermal mass, aerogel blanket, and electrochromic glazing. Walls, ceiling panels, and windows were modified as individual building envelope elements. The limitations of the work include the number of innovative technologies that can be considered, the unavailability of experimental results for validation, and limitations in applicability for the prefabricated houses in other climate conditions of Australia. The following major conclusions were drawn from this work.

- For all three cities, a higher total annual energy saving is observed when the phase change material (PCM) is placed towards the inside of the wall. Perth has the highest energy saving amongst the three, which accounts for 6.4% when PCM is utilised in the walls of the prefabricated house. When the layer thickness is increased, no significant saving is observed in the total energy consumed.

- In aerogel modified wall panels, the highest total energy saving is observed when the aerogel blanket is located towards the external surface of the wall configuration. Annual total energy savings of 8.1%, 6.3%, and 3.3% were observed for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane, respectively.

- Aerogel blanket was identified as more efficient than the PCM as a ceiling insulation. The highest total energy saving was observed in Brisbane, with a saving of 5.3%, followed by Perth, with an annual saving of 4.6%. The energy saving for Melbourne with the ceiling modification using an aerogel blanket is negligible because of the limited thickness, the effect of complementary materials, weak integration with the other building systems, and the effects of the different systems operating in the building.

- When electrochromic windows were evaluated to replace generic plain glass, for the Melbourne and Perth climate conditions, significant energy savings of 8.9% and 3.8% were observed. However, for Brisbane, no energy performance enhancement was observed with the use of electrochromic glazing. Limited performance under high solar gains in Brisbane, and the performance of electrochromic glazing depending on the device control system, could be possible reasons for this observation.

- For the combined modifications of the prefabricated building envelope, which include the incorporation of PCM in walls, aerogel in the ceiling, and the introduction of electrochromic glazing, under Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane climatic conditions, the most efficient combination was the combination with a PCM inside walls placed towards the internal side, aerogel blanket placed inside ceiling panels and electrochromic windows. This combination has yielded total annual energy savings of 15.6%, 11.2%, and 6.1% for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane, respectively. Moreover, these energy saving values resemble those for this optimum housing solution; the heating energy efficiency for Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane are approximately 16.8 kWh m−2, 3.8 kWh m−2, and 1.3 kWh m−2, respectively.

Besides the thermal and energy enhancement of the prefabricated houses using innovative technologies, reducing the mass because of the increased performance of the smart materials over conventional materials leads to reducing the mass of the prefabricated houses as well. Hence, the potential for making the prefabricated houses lighter is an added advantage of incorporating a smart material as an insulation material. Comprehensively, the findings from this work provide prospects of incorporating innovative technologies in prefabricated houses to enhance their benefits. However, as stated previously, some limitations exist in this work. For the further optimisation of the application of innovative technologies in prefabricated houses in Australia, several future approaches could be followed. With the prevalence of numerous innovative technologies applying smart materials as alternatives for conventional building envelopes, the selection of the optimum technology for the climate condition, concerning cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and life cycle performance, is salient to be addressed by considering a detailed parametric study. The results should be further validated using an appropriate experimental programme.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N. and L.A.; methodology, S.B.; software, S.B.; validation, S.N. and L.A.; formal analysis, S.B.; investigation, S.B., S.N., and T.M.; resources, S.N., G.Z., and L.A.; data curation, S.B., S.N., G.Z., and L.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and T.M.; writing—review and editing, S.N., G.Z., and L.A.; visualisation, S.B. and T.M.; supervision, S.N., G.Z., and L.A.; project administration, S.N.; funding acquisition, G.Z. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the RMIT University’s financial and technical support and access to other research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACH | Air Changes per Hour |

| COP | Coefficient of Performance |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| toe | tonne of oil equivalent |

References

- Li, X.G. Green energy for sustainability and energy security. In Green Energy: Basic Concepts and Fundamentals; Li, X.G., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, A.W.; Leite, B.C.C. Performance of aerogel as a thermal insulation material towards a sustainable design of residential buildings for tropical climates in Nigeria. Energy Built Environ. 2022, 3, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, D.G. On the future of global energy. Daedalus 2006, 135, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouhi, A.; El Fouih, Y.; Kousksou, T.; Jamil, A.; Zeraouli, Y.; Mourad, Y. Energy consumption and efficiency in buildings: Current status and future trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DCCEEW Energy Consumption. Available online: https://www.energy.gov.au/energy-data/australian-energy-statistics/energy-consumption#:~:text=Australia’s%20energy%20consumption%20rose%202.0,energy%20mix%20in%202022%2D23 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- DCCEEW Residential Buildings. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/energy/energy-efficiency/buildings/residential-buildings (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Navaratnam, S.; Jayalath, A.; Aye, L. Effects of Working from Home on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Associated Energy Costs in Six Australian Cities. Buildings 2022, 12, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, Q.; Zhang, G.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Navaratnam, S.; Giustozzi, F.; Hou, L. Retrofit of Building Façade Using Precast Sandwich Panel: An Integrated Thermal and Environmental Assessment on BIM-Based LCA. Buildings 2022, 12, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Cabeza, L.; Serrano, S.; Barreneche, C.; Petrichenko, K. Heating and cooling energy trends and drivers in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABS Housing. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing#:~:text=Housing%3A%20Census,unoccupied%20dwellings%20on%20Census%20Night (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Mordor Intelligence Modular Construction in Australia Market Size—Industry Report on Share, Growth Trends & Forecasts Analysis (2024–2029). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/australia-prefabricated-buildings-industry (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Luo, C.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H. An empirical study on the impact of different structural systems on carbon emissions of prefabricated buildings based on SimaPro. World J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, S.; Tushar, Q.; Jahan, I.; Zhang, G. Environmental Sustainability of Industrial Waste-Based Cementitious Materials: A Review, Experimental Investigation and Life-Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginigaddara, B.; Perera, S.; Feng, Y.; Payam, R. Offsite construction skills prediction: A conceptual model. In World Construction Symposium, Proceedings of the10th World Construction Symposium, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 24–26 June 2022; University of Moratuwa: Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 2022; pp. 648–656. [Google Scholar]

- Munmulla, T.; Hidallana-Gamage, H.D.; Navaratnam, S.; Ponnampalam, T.; Zhang, G.M.; Jayasinghe, T. Suitability of modular technology for house construction in Sri Lanka: A survey and a case study. Buildings 2023, 13, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boafo, F.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.T. Performance of modular prefabricated architecture: Case study-based review and future pathways. Sustainability 2016, 8, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Lv, J.; Li, H.X.; Liu, Y.; Yao, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, S. Improving the performance of prefabricated houses through multi-objective optimization design. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Yu, Y.; Hou, J.W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.L.; Meng, X. The testing research on prefabricated building indoor thermal environment of earthquake disaster region. Procedia Eng. 2017, 205, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Long, E.S.; Deng, S.M. An experimental study on the indoor thermal environment in prefabricated houses in the subtropics. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri, M.; Krois, F.; Xhexhi, K. Study of thermal performance of prefabricated large panel buildings. In Proceedings of the 2nd Croatian Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Zagreb, Croatia, 22–24 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Podawca, K.; Pawlat-Zawrzykraj, A.; Dohojda, M. Analysis of the possibilities for improvement of thermal comfort of living quarters located in multi-family large-panel prefabricated buildings. In Proceedings of the 10th Conference on Interdisciplinary Problems in Environmental Protection and Engineering Eko-Dok 2018, Polanica-Zdrój, Poland, 16–18 April 2018; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Naji, S.; Aye, L.; Noguchi, M. Sensitivity analysis on energy performance, thermal and visual discomfort of a prefabricated house in six climate zones in Australia. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Foliente, G.; Chan, W.-Y.; Chen, D.; Ambrose, M.; Paevere, P. A model for predicting household end-use energy consumption and greenhousegas emissions in Australia. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban. Dev. 2013, 4, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Jdayil, B.; Mourad, A.H.; Hittini, W.; Hassan, M.; Hameedi, S. Traditional, state-of-the-art and renewable thermal building insulation materials: An overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 214, 709–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llantoy, N.; Chàfer, M.; Cabeza, L.F. A comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) of different insulation materials for buildings in the continental Mediterranean climate. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Nagar, H.; Singh, I.; Sehgal, S. Smart materials types, properties and applications: A review. Mater. Today-Proc. 2020, 28, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelle, B.P. Traditional, state-of-the-art and future thermal building insulation materials and solutions—Properties, requirements and possibilities. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2549–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicklein, B.; Kocjan, A.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Carosio, F.; Camino, G.; Antonietti, M.; Bergström, L. Thermally insulating and fire-retardant lightweight anisotropic foams based on nanocellulose and graphene oxide. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataraman, M.; Mishra, R.; Kotresh, T.M.; Militky, J.; Jamshaid, H. Aerogels for thermal insulation in high-performance textiles. Text. Prog. 2016, 48, 55–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.S.Y. Smart materials innovative technologies in architecture; Towards innovative design paradigm. Energy Proced. 2017, 115, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, L.; Ngo, T.; Crawford, R.H.; Gammampila, R.; Mendis, P. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions and energy analysis of prefabricated reusable building modules. Energy Build. 2012, 47, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design Builder Software Australia Design Builder. Available online: https://designbuilder.com.au/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- ABCB National Construction Code. Available online: https://ncc.abcb.gov.au/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Australian Government Your Home. Available online: https://www.yourhome.gov.au/getting-started/australian-climate-zones (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Tunçbilek, E.; Wang, D.; Arıcı, M.; Krajčík, M.; Nižetić, S.; Li, D. Energy conservation and CO2 mitigation potential through PCM integration in building envelopes: Effect of façade orientation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 8389–8401. [Google Scholar]

- DuPont DuPont Energain. Available online: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/55819/file-14736951-pdf/docs/energain_flyer.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Kumar, D.; Alam, M.; Sanjayan, J.G. Retrofitting Building Envelope Using Phase Change Materials and Aerogel Render for Adaptation to Extreme Heatwave: A Multi-Objective Analysis Considering Heat Stress, Energy, Environment, and Cost. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F. Energy conservation and renewable technologies for buildings to face the impact of the climate change and minimize the use of cooling. Sol. Energy 2017, 154, 34–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, T.; Jelle, B.P.; Gao, T.; Gustavsen, A. Aerogel granule aging driven by moisture and solar radiation. Energy Build. 2015, 103, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yasiri, Q.; Szabó, M. Incorporation of phase change materials into building envelope for thermal comfort and energy saving: A comprehensive analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 36, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, K.; Khaled, M.; Faraj, J.; Hachem, F.; Castelain, C. A review on phase change materials for thermal energy storage in buildings: Heating and hybrid applications. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Mahyuddin, N.; Sulaiman, R.; Khayatian, F. Phase change material (PCM) integrations into buildings in hot climates with simulation access for energy performance and thermal comfort: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 397, 132312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyenim, F.; Hewitt, N.; Eames, P.; Smyth, M. A review of materials, heat transfer and phase change problem formulation for latent heat thermal energy storage systems (LHTESS). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniassadi, A.; Sailor, D.J.; Bryan, H.J. Effectiveness of phase change materials for improving the resiliency of residential buildings to extreme thermal conditions. Sol. Energy 2019, 188, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.G.; Jeon, J.; Seo, J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S. Performance evaluation of the microencapsulated PCM for wood-based flooring application. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 64, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zheng, Y.M.; Liu, C.Y.; Wu, G.Z. Numerical analysis on thermal performance of roof contained PCM of a single residential building. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 100, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, A.; Martorell, I.; Medrano, M.; Pérez, G.; Cabeza, L.F. Experimental study of using PCM in brick constructive solutions for passive cooling. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 534–540. [Google Scholar]

- Kosny, J.; Miller, W.A.; Yarbrough, D.; Kossecka, E.; Biswas, K. Application of Phase Change Materials and Conventional Thermal Mass for Control of Roof-Generated Cooling Loads. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, M.C.; Sulong, N.H.R.; Chong, W.T.; Poh, S.C.; Ang, B.C.; Tan, K.H. Integration of thermal insulation coating and moving-air-cavity in a cool roof system for attic temperature reduction. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 75, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.Q.; Kong, X.F.; Li, Y.T.; Du, Y.X.; Qia, C.Y. Numerical and experimental research of cold storage for a novel expanded perlite-based shape-stabilized phase change material wallboard used in building. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 155, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.L.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, J.; Frisco, S.; Song, P.; Li, X.G. The shape-stabilized phase change materials composed of polyethylene glycol and various mesoporous matrices (AC, SBA-15 and MCM-41). Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 3550–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Li, L.; Zhao, M. Experimental assessment on the use of phase change materials (PCMs)-bricks in the exterior wall of a full-scale room. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 120, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Li, W.; Yang, C.; Huang, H.; Guo, Y.; Ge, F.; Zhang, Y. Thermal performance of an active casing pipe macro-encapsulated PCM wall for space cooling and heating of residential building in hot summer and cold winter region in China. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.Y.; Yu, X. Thermo and light-responsive building envelope: Energy analysis under different climate conditions. Sol. Energy 2019, 193, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Feijoo, M.A.; Orgeira-Crespo, P.; Arce, E.; Suárez-García, A.; Ribas, J.R. Effect of insulation on the energy demand of a standardized container facility at airports in Spain under different weather conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesser, H.D.; Goswami, P.C. Aerogels and related porous materials. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 765–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, C.; Moretti, E. Glazing systems with silica aerogel for energy savings in buildings. Appl. Energy 2012, 98, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, K.; Achard, P.; Biwole, P. Hygro-thermal properties of silica aerogel blankets dried using microwave heating for building thermal insulation. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 14–22, Erratum in Energy Build. 2018, 168, 165–166.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffat, S.B.; Qiu, G.Q. A review of state-of-the-art aerogel applications in buildings. Int. J. Low-Carbon. Technol. 2013, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]