1. Introduction

Rising environmental concerns, escalating energy demand, and increasing volatility in electricity prices have created a pressing need for advanced energy systems that balance reliability, cost efficiency, and sustainability. In this context, microgrids have emerged as a promising solution. By integrating distributed generation (DG) technologies and demand response (DR) capabilities, microgrids offer localized control and flexibility within the broader energy ecosystem [

1].

The global shift toward clean energy is accelerating, driven by the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change. Renewable energy sources—such as wind and solar—are at the forefront of this transition due to their environmental benefits and declining costs [

2,

3]. However, their inherent intermittency and unpredictability pose significant challenges for power system stability. Large-scale integration of renewable generation into conventional distribution networks often leads to voltage fluctuations, frequency instability, and reduced inertia, complicating grid management (

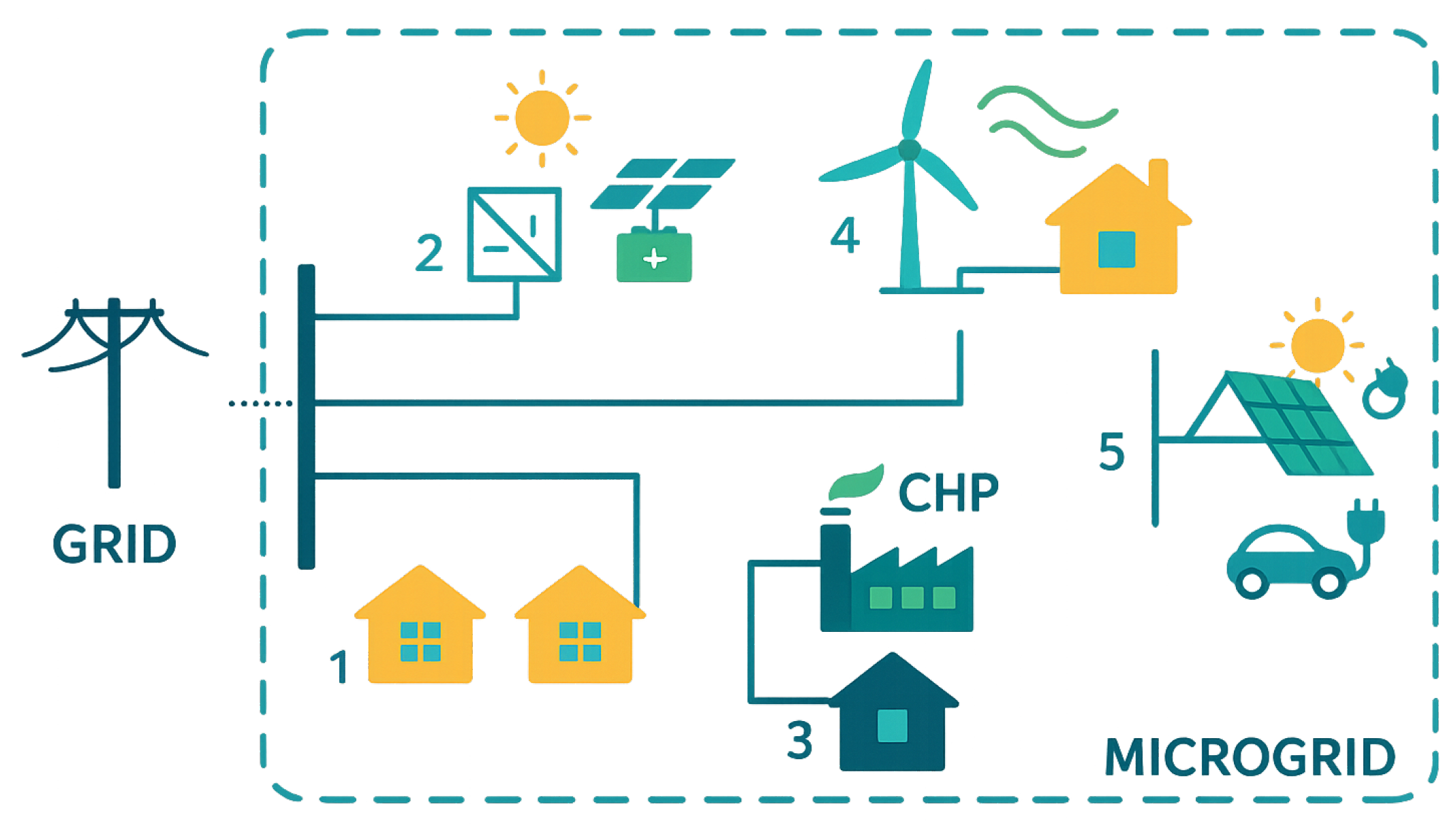

Figure 1).

Stochastic optimization has been extensively applied to microgrid operation and dispatch, offering a systematic way to manage the uncertainty inherent in renewable generation, load fluctuations, and market price variability. For instance, Ref. [

4] proposed a stochastic optimal power flow framework to schedule flexible resources in microgrid operation, while Ref. [

5] developed a stochastic model predictive control approach for integrated energy management under uncertainty. Similarly, Ref. [

6] introduced a stochastic optimization model that coordinates distributed energy resources and demand response programs to minimize operational costs. These studies collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of probabilistic modeling in improving reliability and economic performance. Building upon this foundation, the present work advances the field by integrating real-time dynamic pricing and demand response into a two-stage stochastic optimization framework, enabling both cost-effective and adaptive decision-making in real-world microgrid environments.

While the present study focuses on scenario-based stochastic optimization for real-time microgrid operation with an emphasis on computational efficiency, it is essential to acknowledge recent advances that align with this objective. Notably, Ref. [

7] introduced a high-efficiency economic dispatch framework for hybrid AC/DC networked microgrids using steady-state convex bidirectional converter models, achieving significant improvements in convergence speed and scalability. Such contributions highlight the ongoing evolution of optimization techniques toward more tractable and computationally efficient solutions in complex microgrid architectures. Incorporating these insights provides a stronger contextual foundation for the proposed approach, emphasizing its relevance to contemporary developments in hybrid microgrid coordination and real-time energy management under uncertainty.

To address these challenges, microgrids combine renewable energy sources with controllable loads, energy storage systems, and smart control technologies. This hybrid configuration enhances operational flexibility, supports local energy autonomy, and contributes to overall system resilience [

8]. Smart microgrids also enable efficient coordination of generation and consumption through embedded Energy Management Systems (EMSs) that facilitate real-time decision-making and optimization [

6,

9,

10].

Electric vehicles (EVs), which are gaining widespread adoption, introduce additional complexity and opportunity. EVs function as both mobile loads and distributed storage units, enabling bidirectional energy exchange with the grid. Recent studies, such as [

11], highlight the potential of vehicle-to-grid (V2G) strategies to stabilize short-term fluctuations and contribute to long-term decarbonization. In this work, we extend this line of inquiry by incorporating stochastic modeling of EV participation within DR programs in microgrids, accounting for state-of-charge constraints and user mobility patterns [

12].

Demand response is a cornerstone of modern Demand-Side Management (DSM). By incentivizing users to modify their electricity usage in response to price signals or system conditions, DR enhances grid reliability, reduces peak demand, and lowers operational costs. Price-based DR mechanisms shift consumption from peak to off-peak hours, while incentive-based DR programs offer compensation for load curtailment [

4,

5].

Despite their benefits, microgrids also face operational and economic challenges, particularly under high uncertainty. Any mismatch between generation and consumption can lead to increased costs, supply shortages, or even outages [

13,

14]. Although energy storage offers a potential solution, its high capital cost limits widespread adoption [

15]. Thus, effective DR strategies have gained attention as more accessible and scalable alternatives [

16].

Moreover, dynamic pricing mechanisms have shown considerable promise in enhancing microgrid performance. However, their integration into stochastic optimization frameworks remains limited in the existing literature. Most prior works rely on deterministic assumptions or treat DR and OPF models in isolation, reducing the realism and applicability of their findings [

16,

17,

18,

19].

To bridge this gap, this study introduces a unified, uncertainty-aware optimization framework that integrates real-time pricing, DR programs, and OPF-based dispatch. The model explicitly considers key sources of uncertainty—market prices, renewable output, and load variability—through scenario-based probabilistic analysis. Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) is also employed to account for risk-averse decision-making in high-volatility environments [

20,

21].

Recent studies have also adopted robust optimization (RO) to address uncertainty in microgrid operation. Ref. [

22] proposed a two-stage RO model accounting for uncertainty in renewable generation and demand, achieving improved resilience under variable conditions. Similarly, Ref. [

23] introduced a multiband robust optimization method for generator and battery bidding under uncertain market prices. Incorporating RO techniques can complement stochastic optimization by providing worst-case guarantees under extreme scenarios, suggesting a promising direction for hybrid modeling.

Stochastic operation typically requires the consideration of a large number of uncertain scenarios, which can significantly increase computational complexity and hinder real-time applicability. To address this challenge, the proposed framework integrates a scenario reduction technique based on mixed-integer linear programming (MILP), which systematically identifies and retains a representative subset of scenarios while preserving the statistical characteristics of the original probability distributions. This approach substantially reduces the dimensionality of the optimization problem without compromising accuracy. Furthermore, the heuristic implementation of the two-stage stochastic model enables rapid convergence by decomposing decision variables into pre-decision and corrective actions, optimized within short 15-min intervals. Combined with efficient linear formulations of the optimal power flow (OPF) problem, these design choices ensure that the proposed method achieves high computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time microgrid operation and adaptive control in dynamic environments [

7,

21,

24].

The main contributions of this research are as follows:

A two-stage stochastic optimization model integrating real-time pricing with OPF constraints for microgrids;

A comprehensive representation of price-based and incentive-based DR schemes, including contract structures and flexibility bounds;

A realistic formulation of EV behavior using time-coupled state-of-charge dynamics within a mixed-integer programming framework;

Incorporation of CVaR to manage operational risks and improve robustness under uncertainty.

2. Methodology

The nomenclature table summarizes all variables and parameters employed in the study, providing clear definitions, measurement units, and relevant symbols related to power generation, thermal systems, and demand response.

Let us start by looking at how conventional power systems work. In these traditional setups, electricity demand is something we cannot directly control. It fluctuates throughout the day depending on consumer behavior, weather, and other factors. Because of this, operators face a great deal of uncertainty. They must constantly adjust the generation side in real time just to keep up with what the load requires at any given moment. In other words, the system is reactive—it responds to changes after they happen, which often leads to inefficiencies and limits how flexibly the grid can operate.

Now, microgrids take a different approach. Instead of relying on centralized generation to serve scattered loads, microgrids integrate local energy generation—what we call distributed generation—with localized consumption. Think of it as a smaller, more self-contained version of the power grid, where energy can be produced and used closer to where it is needed. This setup allows for much more precise control, and it improves the match between supply and demand at a local level [

24].

As you might expect, advances in technology have opened the door to smarter and more efficient grid operations. But even with all this progress, managing energy intelligently remains a real challenge—especially with the increasing complexity of smart grids. comes in. DR programs are designed to encourage users to shift or reduce their energy usage at key times, typically in response to price signals or grid conditions. By doing this, they help to flatten the peaks in demand, ease stress on the system, and reduce operational costs. DR is no longer seen as an optional feature—it is now considered an essential part of DSM, and it plays a key role in creating a more adaptive and resilient electrical grid [

25].

Problem Definition: The proposed model aims to determine the optimal operation of a renewable-based microgrid under uncertainty in generation, demand, and energy prices.

Decisions: Determine the generation dispatch, storage operation, and real-time dynamic prices.

Limits: Physical and operational constraints of generators, storage capacity, and energy balance.

Objective: Minimize the total operational cost while maximizing renewable utilization and maintaining supply–demand equilibrium.

Formally, the stochastic optimization problem can be represented as

subject to

where

x represents the decision vector,

denotes the stochastic variables (renewable generation, demand, and prices), and

is the expectation operator.

2.1. Distributed Generation (GD)

In a conventional power system, electricity is generated at a few large, centralized plants and then transmitted across long distances to reach consumers. These systems include various types of generation units distributed throughout the grid infrastructure. Their main role is to supply electricity with acceptable standards of quality—primarily in terms of voltage and frequency—across a widely dispersed demand base (

Table 1).

Now, each generation source relies on a specific primary energy resource, such as water, natural gas, or wind. These resources vary in nature, and each type of generator has its own operating characteristics that influence how it contributes to the grid [

26].

When we shift our focus to microgrids, we apply the same basic principles but at a smaller and more localized scale. A microgrid can host a diverse mix of generation technologies. These typically include traditional units such as small hydroelectric plants and micro gas turbines, as well as non-traditional or renewable technologies like photovoltaic (PV) modules and wind turbines [

25].

Here is where the key difference lies: traditional generation units generally offer stable and controllable outputs, because their fuel sources are consistent. But renewable units behave differently. Their output depends entirely on natural resources—sunlight, wind, etc.—which are inherently variable and uncertain. These are what we call “discrete” or stochastic variables. For instance, the power generated by a wind turbine can change from minute to minute depending on wind speed at that exact location. As a result, the energy output from renewable sources is not just variable—it is also difficult to predict with high accuracy [

25].

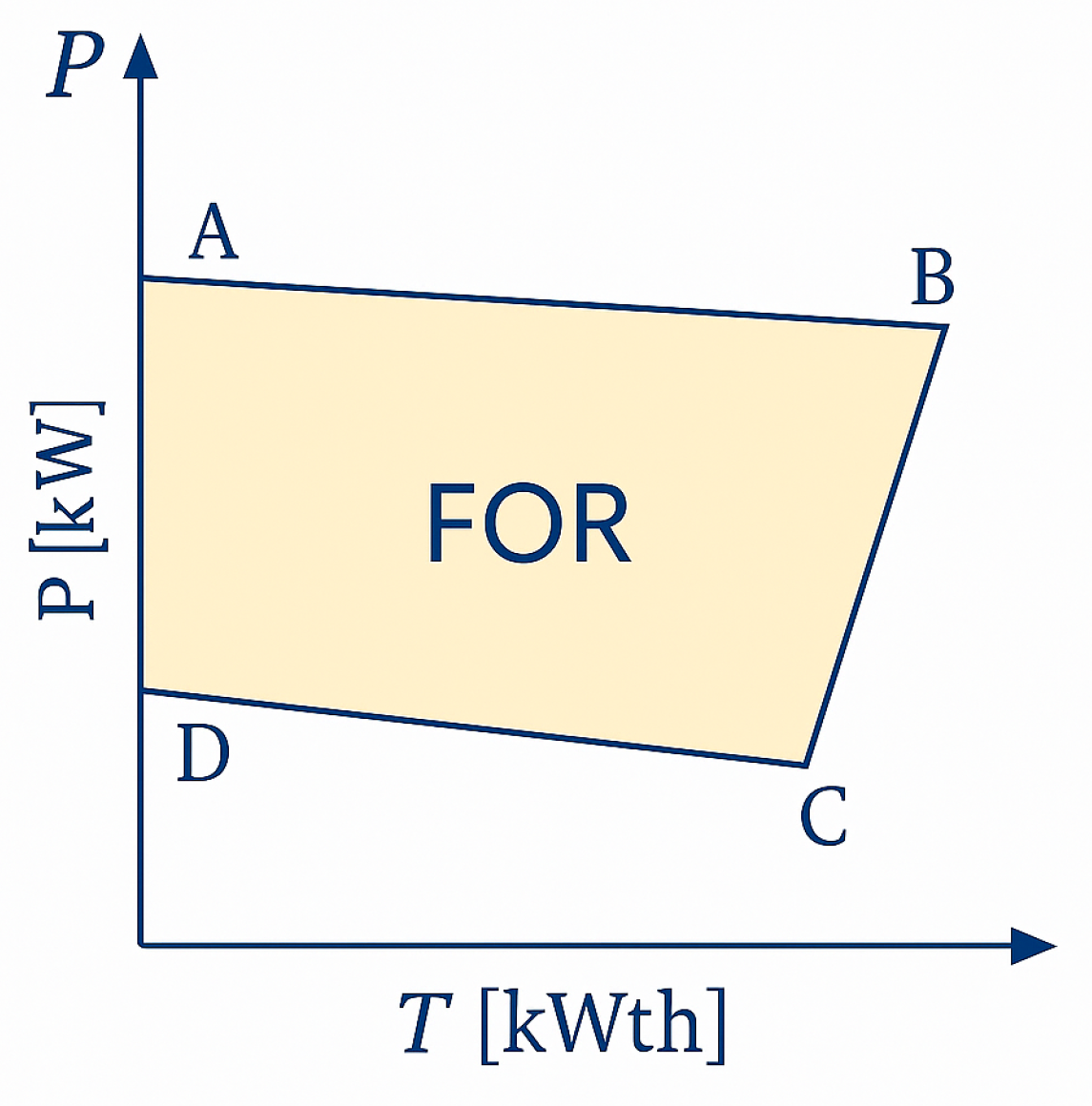

Figure 2 illustrates the Feasible Operating Region (FOR) of a CHP unit. The shaded polygonal area, denoted by the vertices

A,

B,

C, and

D, represents all admissible combinations of electrical power output

P [kW] and thermal energy production

T [kWth] that the CHP unit can deliver while respecting its technical and operational constraints. The polygon A–B–C–D represents all admissible

operating points subject to electrical and thermal limits; segment styles indicate active constraints (A–B:

; B–C:

; C–D:

; A–D:

). Dotted guides show

and

. Labeled vertices correspond to the case study values A(5,0), B(4,6), C(2,3), and D(2.5,0) in kW/kWth. The model implementation caps electrical output at 1500 kW while neglecting heat, as noted in

Section 2.1.

Each boundary of the polygon corresponds to a specific limit in the CHP’s operational behavior:

Segment : Maximum electrical output as a function of thermal output.

Segment : Minimum electrical output limit.

Segment : Minimum thermal generation capability.

Segment : Maximum thermal generation capacity.

The FOR serves as a constraint set in optimization problems involving CHP scheduling and dispatch, ensuring that selected operating points remain physically realizable. Any point outside the FOR lies beyond the CHP unit’s feasible output envelope and would violate either electrical, thermal, or combined capacity restrictions.

This uncertainty presents a challenge when attempting to balance supply and demand in real time. It requires us to model and manage renewable generation in new ways, often using probabilistic approaches. And this is precisely why understanding distributed generation is so important—because it forces us to rethink how we plan, control, and optimize modern power systems.

Equations (1) and (2) define the feasible range within which a CHP unit can operate. More specifically, they establish the boundaries for both electrical and thermal output that determine whether the CHP system’s operating point falls within the valid region known as the Feasible Operating Region, or FOR.

To better understand how a CHP unit operates within its feasible region, Equations (1) and (2) can be broken down further into a set of relationships described in Equations (3)–(7). These correspond to a convex Feasible Operating Region (FOR) and help define it geometrically.

The following set of constraints mathematically define the Feasible Operating Region (FOR) of the combined heat and power (CHP) unit in the power–thermal output space. This formulation ensures that the CHP operates within the permissible boundaries defined by its physical and thermodynamic characteristics.

Equation (3) enforces the lower bound of the feasible region by modeling the inequality constraint associated with segment of the FOR polygon. It ensures that any operating point lies above or on the line connecting points A and B, where P and T denote electrical and thermal output, respectively.

Equations (4) and (5) represent the upper convex boundary of the operating region. Specifically, Equation (4) describes the line segment , while Equation (5) describes segment . These constraints ensure that the CHP unit’s output remains below the maximum allowable envelope of operation. The binary variable and the large positive constant M are used to model unit commitment status, such that the upper boundary constraints are only enforced when the unit is online.

Equations (6) and (7) impose upper bounds on the electrical and thermal outputs, respectively. When the CHP unit is operational (i.e.,

), these bounds restrict the outputs to the maximum values defined by the coordinates of points

A and

B. Conversely, when the unit is offline (

), both power and heat outputs are constrained to zero.

The operating cost of a CHP unit is typically modeled using a linear cost function, as shown in Equation (

8). This cost function accounts for three main components: the cost of fuel, the startup cost, and the shutdown cost. Among these, the fuel cost is usually the most significant and varies depending on the local energy market where the CHP system operates. Startup and shutdown costs are associated with the transitions in the unit’s operating state and must be included to accurately capture the economic behavior of the system.

In a CHP system, electrical and thermal outputs are inherently linked. To achieve the maximum electrical power output, the unit must also simultaneously produce its maximum thermal output. This condition corresponds to Point B on the operational curve shown in

Figure 2, which marks the peak of both electrical and thermal performance within the system’s Feasible Operating Region (FOR).

However, in the context of this particular study, we are focused exclusively on the electrical generation aspect of the CHP unit. As a result, thermal output is considered negligible and is not included in the optimization. Based on the constraints defined in Equations (3)–(7), the maximum electrical capacity used in the model is 1500 kW. This simplification allows for a more targeted analysis of the CHP’s role in meeting demand, without accounting for the complexities introduced by thermal energy recovery or use.

2.2. Wind Power Generation Systems

Wind power technology and system development have seen a significant rise over the past decade. As more wind generation plants are deployed, ongoing innovations continue to emerge, particularly regarding the efficient use of kinetic energy to drive the rotation of turbine blades. Today, we find high-capacity wind farms operating in a variety of settings, thanks to the ease of installing this technology on both flat and uneven terrain, including offshore environments [

27]. Since wind is the primary resource for this type of generation, and its cycles are naturally continuous within the environment, wind farms are capable of producing energy around the clock, making them a highly efficient energy source.

However, because wind is an inherently variable and uncertain resource, careful analysis is required. Typically, this involves applying the Weibull probability distribution, using at least two years of hourly wind data from historical records. This statistical approach helps ensure more accurate assessments when designing and planning wind generation systems.

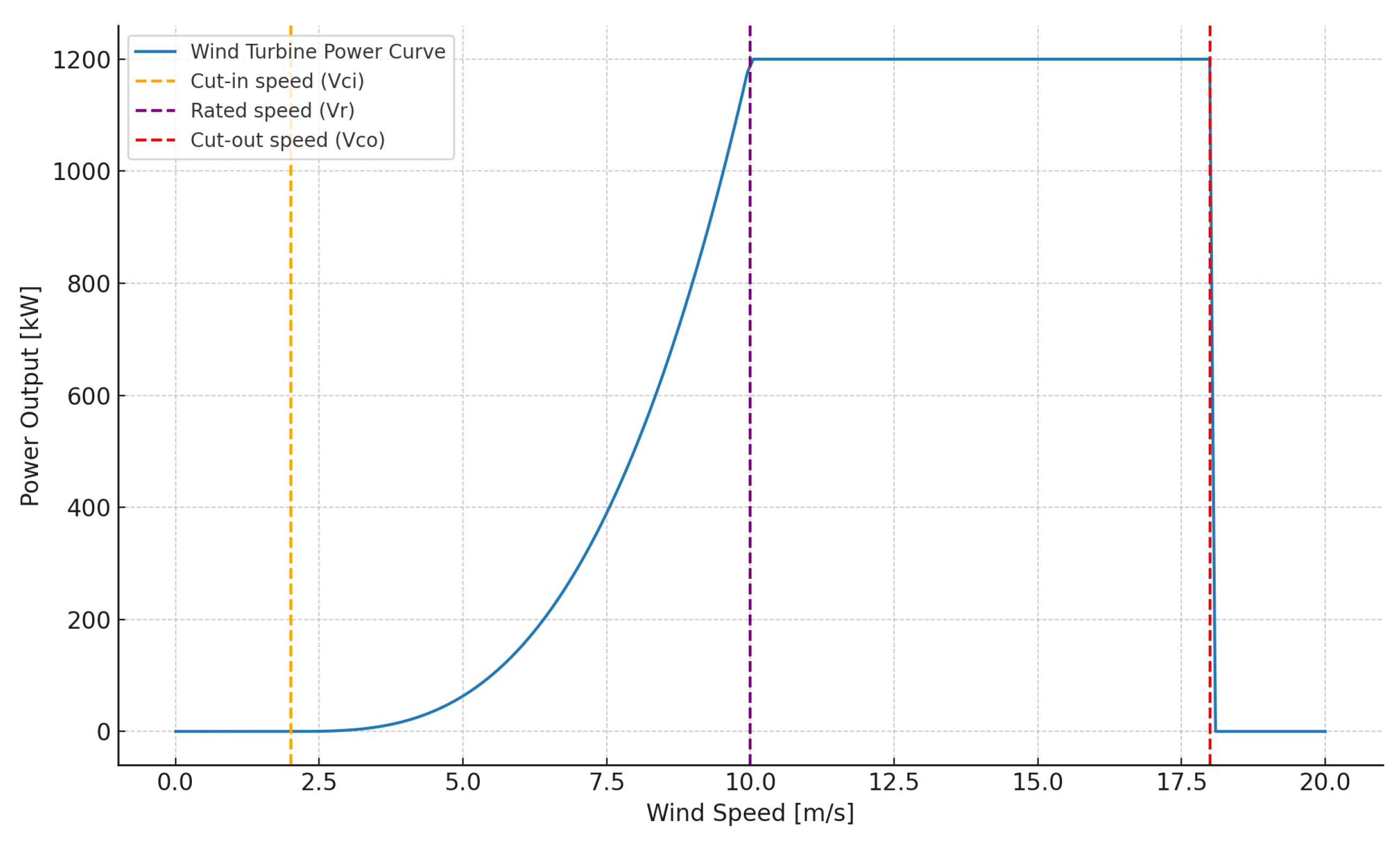

The output power of a wind turbine at a given time t can be calculated using the following equation:

Equation (

9), which defines the wind turbine’s power output, can also be reformulated as shown in Equation (

10). This version provides greater insight into how wind speed influences turbine performance across three critical thresholds.

First, we have the cut-in wind speed (

), which is the minimum wind speed required to activate the turbine. If the wind speed at a given time

t is below this threshold, the turbine does not generate any power—its output is zero. Between

and the rated wind speed (

), the turbine’s power output increases nonlinearly—specifically, it follows a cubic relationship, as described in Equation (

9). This means that small increases in wind speed within this range result in much larger increases in power output.

Once the wind speed exceeds

, the output reaches the turbine’s rated or nominal capacity and remains constant. However, if the wind speed surpasses the cut-out wind speed (

), the turbine automatically shuts down as a protective measure to avoid mechanical damage. In this condition, the output again drops to zero.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the behavior described in Equation (

10) is represented graphically. This figure helps visualize how a wind turbine’s power output varies under different wind speed conditions. Each operational range—below cut-in speed, between cut-in and rated speed, at rated output, and beyond cut-out speed—produces a distinct response in the turbine’s performance curve.

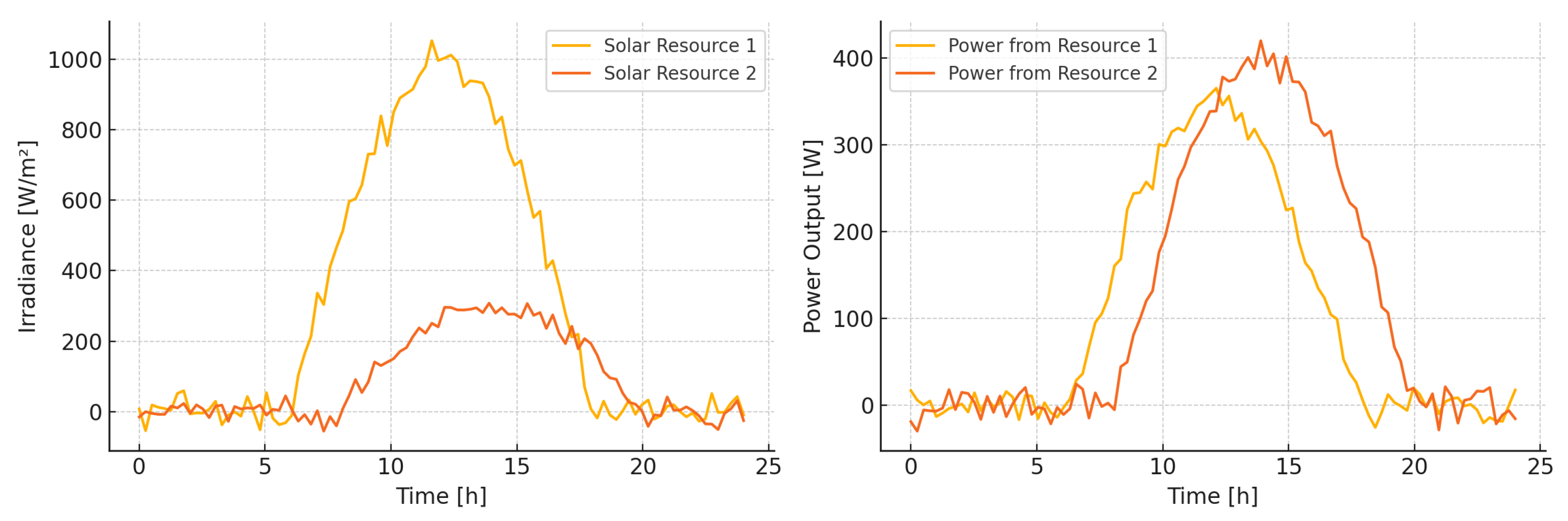

2.3. Photovoltaic Generation Systems

Let us now turn our attention to photovoltaic (PV) energy systems, which, like wind turbines, rely heavily on environmental variables that exhibit uncertainty. Because of this variability, we must approach the analysis of solar power systems using probabilistic methods, specifically through probability density functions (FDPs). These analyses are typically based on at least two years of hourly data, which helps reduce statistical error and ensures more reliable system design and forecasting [

27].

The power output of a photovoltaic system is primarily determined by two environmental factors: solar irradiance and ambient temperature. Both parameters vary continuously throughout the day and across seasons, and they can significantly influence system performance. Additionally, the specific characteristics of the solar panel technology used—such as efficiency, temperature coefficient, and material properties—play an important role in determining how much energy is produced.

To quantify this, the power generated by a solar panel can be modeled using the following equations, relating irradiance, temperature, and panel efficiency to the resulting electrical output, which we will look at next:

Let us now focus on one key operational characteristic of photovoltaic (PV) systems—the impact of temperature and irradiance on panel efficiency. A standard reference value used in modeling is the nominal operating cell temperature (NOCT), typically around 45 °C. This value assumes specific test conditions and serves as a baseline for predicting performance.

It is important to understand that the efficiency of a PV panel is not solely determined by irradiance. Instead, there is a delicate balance between irradiance and cell temperature. If either of these parameters deviates significantly—either too high or too low—the panel’s ability to generate electrical power may be compromised. For example, a location might receive excellent solar irradiance, but if the ambient temperature is excessively high, the cell temperature may exceed optimal operating levels, thereby reducing overall efficiency. Conversely, in cooler environments with less irradiance, power output might also suffer.

Figure 4 provides a practical illustration of this concept. We see irradiance profiles from two distinct geographic locations. At first glance, “Solar Resource 1” appears superior due to higher irradiance values throughout the day. However, when we observe the corresponding power output curves, “Solar Resource 2” actually produces more electricity. This discrepancy highlights how temperature effects can offset the apparent benefits of higher irradiance, reinforcing the importance of considering both factors in PV system design and planning.

2.4. Demand Response Programs

Now, let us turn to DR, a fundamental concept in modern grid flexibility and energy management. The main objective of DR programs is to encourage end users to adjust their typical consumption behavior based on real-time electricity market signals or incentive-based structures. This helps utilities manage load more efficiently and reduces stress on the grid during peak hours.

DR programs are generally classified into two main categories:

- (1)

Price-based DR programs, which influence user behavior by varying the cost of electricity throughout the day.

- (2)

Incentive-based DR programs, which offer direct financial rewards to users who agree to reduce or shift their consumption upon request [

28].

Let us first examine price-based DR in more detail. Under these schemes, consumers are encouraged to reduce energy usage during peak price periods and shift their consumption to off-peak hours, when electricity is more affordable. Since electricity price and demand are typically directly correlated, this dynamic pricing leads to a more balanced demand curve, smoothing out sharp peaks and valleys in consumption [

29].

2.5. Price-Based DR Modeling

The price-based DR model is formulated to capture temporal load flexibility by enabling the redistribution of electrical demand between peak and off-peak hours in response to dynamic pricing signals.

Equation (14) defines the net demand at time t under scenario i, as the sum of the baseline load , increased by the amount of load shifted to peak periods , and decreased by the load deferred to off-peak hours . This expression captures real-time reconfiguration of demand in response to price signals.

Equation (15) imposes a conservation constraint on the total shifted load, ensuring that the cumulative upward adjustments during peak periods are exactly offset by downward adjustments during off-peak periods over the scheduling horizon T. This condition preserves energy neutrality and avoids artificial inflation or reduction of total demand.

Equations (16) and (17) define the operational limits of load shifting in both directions. The upward shift

and the downward shift

are constrained to be non-negative and bounded by fixed percentages

and

, respectively, of the baseline load

at each time

t. These constraints ensure that the demand flexibility remains within feasible physical and behavioral limits.

2.6. Incentive-Based Demand Response Programs

Incentive-based DR programs operate differently from price-based schemes. In this case, users enter into formal agreements or contracts in which they commit to reducing their electricity consumption under certain conditions, typically in exchange for financial compensation. These programs are especially relevant when system security is not a critical concern for the user, such as in cases where customers have on-site generation resources or are connected to microgrids.

When a disturbance occurs upstream in the main grid—such as a voltage drop or a supply failure—these users or microgrids may be required to operate in island mode, temporarily disconnecting from the broader network. During these periods, they must reduce their electrical demand (a process known as load shedding) to maintain system stability. In return, they receive economic incentives as compensation for their cooperation [

30].

From a cost modeling perspective, incentive-based DR programs include two primary cost components:

Load Preparation Cost. This refers to the expense of having a load available to be curtailed when needed. It functions as a form of energy reserve and can be structured using multi-level contracts that specify different tiers of commitment. Load Reduction Cost. This is the payment made to the user when the agreed-upon load is actually curtailed in response to a DR event [

19].

Equation (

18) defines the total load preparation cost, denoted as

, which represents the financial commitment incurred by the system operator to reserve a portion of the user’s load for potential curtailment. This cost is modeled through a three-tier contract structure, where each tier

is characterized by a distinct incentive rate

and a corresponding reserved load

:

This expression aggregates the cost of reserving load under each contract level, scaled by the respective incentive rate. The load reservation is bounded to prevent overcommitment relative to the user’s total demand.

Equations (19)–(21) impose tier-specific upper bounds on the committed load, expressed as a percentage

of the total demand

at each time step

t and in each scenario

i. These constraints ensure proportional allocation of DR capacity across contract levels and preserve operational feasibility:

Equation (

22) models the cost associated with actual load reduction—that is, the payment made to the end user when they reduce their consumption as part of the demand response agreement. This cost reflects the direct compensation for curtailed energy during a DR event.

Equation (

23) defines the maximum amount of load that can be curtailed. This value acts as an upper bound, ensuring that the amount of demand reduced remains within the limits set by the prior contractual agreement. Exceeding this limit could compromise system reliability or unfairly impact customer operations.

If the operator requests a load reduction beyond the agreed-upon amount, and the user is unable to meet their energy needs as a result, the system is considered to have failed to supply the necessary energy. In such cases, the upstream grid operator is required to pay a penalty to the affected user, compensating for what is referred to as energy not supplied (ENS). This penalty cost is formally described in Equation (

24).

2.7. Electric Vehicle (EV) Power Modeling

As electric vehicles (EVs) continue to gain traction worldwide, integrating their charging behavior into power system models has become essential. The global transition from internal combustion engines to electric drivetrains means that EVs are no longer a marginal load—they are becoming a significant component of electricity demand.

In particular, we must focus on the state of charge (SoC) of EV batteries. This variable plays a dual role in system analysis: on the one hand, it serves as a key operational metric for battery availability; on the other, it can be used as a flexible resource within DR strategies. For example, charging EVs during peak demand hours can place excessive stress on the grid, while coordinated charging during off-peak times can help flatten the demand curve and improve grid stability [

31].

To capture these dynamics, we model the SoC behavior of EV batteries using a series of equations—specifically, the term EDC represents the time-dependent evolution of battery energy, functionally equivalent to the state of charge (SoC) in dynamic modeling, Equations (25)–(31): Equation (

25) sets the initial SoC of the EV battery. Equation (26) updates the SoC at time

t, factoring in both charging and discharging power, as well as the energy stored during the previous time interval. Equations (27)–(31) define the operational constraints of the SoC. A key element here is Equation (

28), which estimates the amount of energy needed to move an EV during a given time period. The parameter

represents the distance or activity of each vehicle per hour, which directly influences its energy needs. Finally, Equation (

31) introduces binary control variables to indicate the EV’s operational status: If

and

, the vehicle is charging. If

and

, it is discharging. If both values are zero, the vehicle is in motion and not interacting with the grid. The integer variables

and

are treated using a mixed-integer programming approach, allowing binary control of the EV charging and discharging states within the optimization framework.

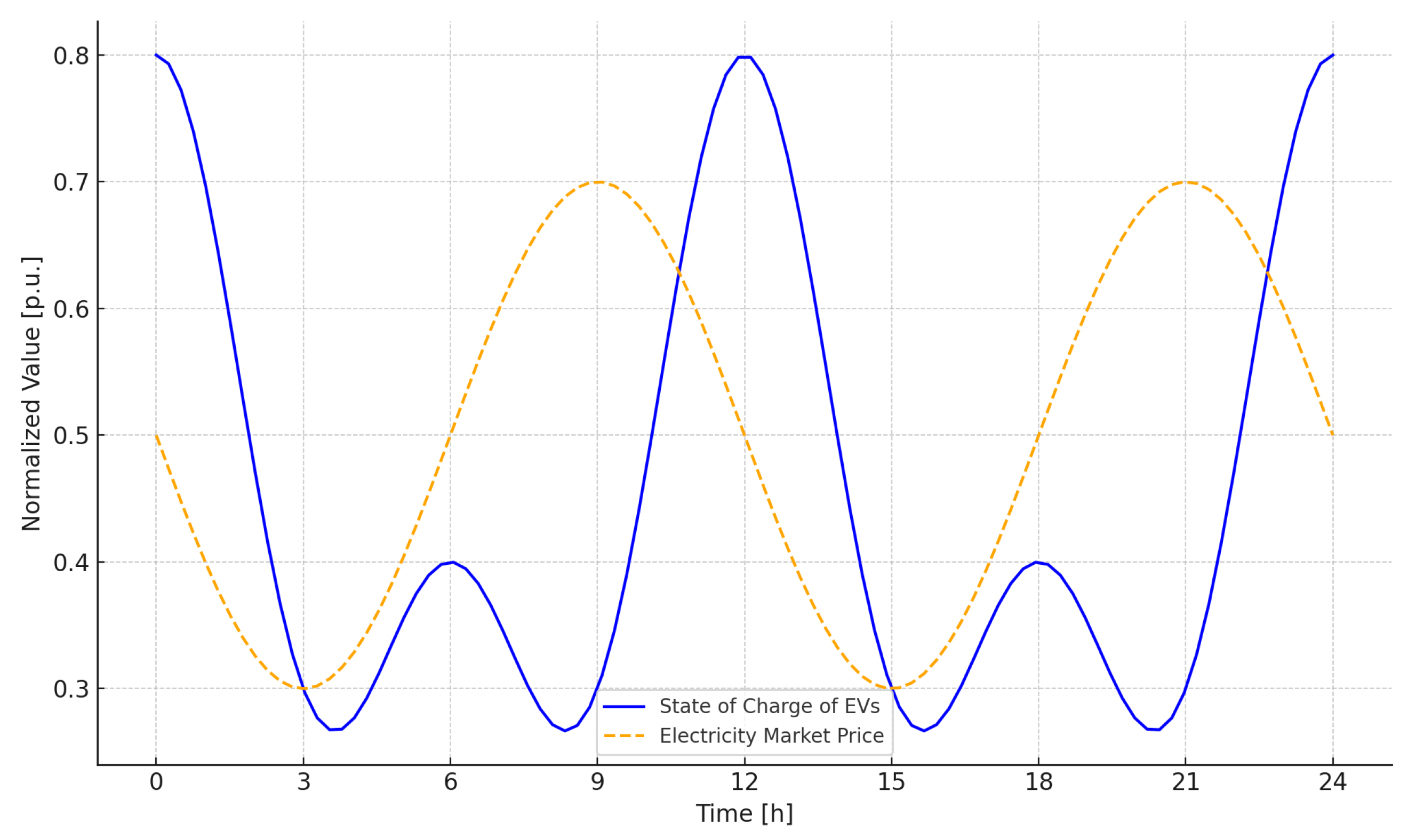

2.8. EV State-of-Charge and Market Pricing Dynamics

Figure 5 illustrates two key aspects of electric vehicle (EV) integration into power systems: the state of charge (SoC) of EV batteries and the behavior of electricity market prices over the course of a day. What we observe is a clear inverse relationship between these two variables. When market prices are low—typically during off-peak hours—EV batteries tend to reach higher SoC levels. Conversely, when prices are high, SoC levels decline, either because charging is avoided or because energy is being discharged back to the grid.

This correlation highlights the dynamic nature of electricity pricing, which responds directly to fluctuations in demand. Importantly, it also shows that the effectiveness of demand response policies can influence how EVs are charged. With well-designed DR programs, EV charging patterns can be synchronized with market price signals, ensuring that charging occurs during periods of low demand and low cost. This kind of price-responsive behavior can help stabilize the grid while also reducing energy expenses for EV owners.

2.9. Power Balance in Microgrids

When managing a power system—particularly a microgrid—that integrates multiple types of generation sources, including both conventional (e.g., CHP units) and renewable (e.g., wind and solar), along with distributed loads, achieving power balance is essential. At every moment in time, the total amount of electricity generated must equal the total electricity consumed, accounting for all loads and any energy losses or unmet demand.

To manage this, we implement an optimal power dispatch strategy, which is grounded in an optimal power flow (OPF) model. This approach allocates generation in the most efficient way possible, taking into account both fixed and variable generation costs. These costs are typically represented using polynomial cost functions that are specific to each type of generator.

By doing so, the system can maximize overall operational efficiency while ensuring that all power demands are reliably met. This balance between supply and demand forms the core principle of energy system operation, especially in microgrids where generation and consumption are closely coupled [

26]. In a well-functioning microgrid, power balance is a fundamental operating condition. This means that the total demand—including not just the active load but also any unsupplied energy (ENS) and load shedding due to reliability constraints—must match the total generation from all available energy sources at any given moment.

This principle ensures that the system remains stable and avoids overloading or undersupplying critical loads. Mathematically, this relationship is expressed as a power balance equation, where the sum of all power generated by distributed energy resources (such as CHP units, wind turbines, solar panels, demand response programs, and any external grid support) must equal the sum of all power consumed or lost, including

However, in an ideal scenario—where the network operates without any disturbances, no load shedding is necessary, and all energy demands are fully met—the power balance equation can be significantly simplified.

In this case, the total power generated at each time step must be equal to the total demand across the microgrid. That is, there are no unmet energy needs and no curtailment, so the equation reduces to a direct match between generation and consumption:

2.10. Two-Stage Stochastic Programming-Based Heuristic

In the context of modern energy systems—especially microgrids that rely on renewable and distributed energy resources—uncertainty plays a major role. Variables such as market electricity prices, solar irradiance, wind speed, and load demand can fluctuate unpredictably. To handle this uncertainty in a mathematically sound way, we turn to stochastic programming.

One of the most widely used frameworks in this area is two-stage stochastic programming. This technique divides decision-making into two stages: First-stage decisions are made before the uncertain variables are revealed. These decisions represent a baseline or initial plan based on expected conditions. Second-stage decisions (also known as recourse actions) are made after the uncertainties are realized. These adjust the initial decisions to correct for any deviations from expected values. Now, applying this to a heuristic method means that instead of solving the stochastic optimization problem exactly—which may be computationally expensive—we approximate a solution using simplified rules or iterative logic. This enables faster execution while preserving the core structure of the uncertainty.

In the case of microgrid operation and dynamic price allocation, the first-stage decisions might include setting preliminary power outputs for stochastic sources like wind, solar, and CHP units, based on forecasts. The second-stage decisions would then adjust these outputs or trigger demand response programs depending on the actual conditions observed, such as real wind speeds or current electricity prices. Objective function (Z): Minimize the operating cost of the microgrid:

Subject the above equation to (33) and (35):

In Equation (

34) the objective function is shown, where the function of operating costs of the microgrid is minimized, with this function also accounting for the dispatched power of each type of generation plant multiplied by the marginal cost of the microgrid for each period of time to be analyzed.

The proposed two-stage stochastic optimization framework manages dynamic data by combining probabilistic modeling with adaptive demand response (DR) strategies. In the first stage, scheduling decisions are optimized using forecasted distributions of uncertain variables—wind speed, load demand, and electricity prices—captured through suitable probability density functions. The second stage performs real-time recourse adjustments when actual conditions deviate from forecasts, addressing short-term fluctuations such as wind variability, EV charging surges, or price spikes. Through coordinated price-based and incentive-based DR actions, the model reallocates or curtails loads to balance supply and demand efficiently. This integrated design enables rapid adaptation to changing system conditions, ensuring cost-effective and reliable operation of microgrids under uncertainty.

3. Problem Setup

When analyzing optimal management strategies for a microgrid, one of the primary challenges we face is dealing with uncertainty in system variables over time. If we rely solely on deterministic optimization models—those that assume all parameters are known and fixed—we risk obtaining misleading or inaccurate results. This is because many key variables in real-world energy systems, such as demand, wind speed, solar radiation, and electricity prices, exhibit inherently unpredictable behavior.

To obtain a more realistic and reliable analysis, it is essential to adopt a probabilistic approach. This involves modeling the uncertain variables using probability distribution functions (FDPs) derived from historical data—ideally covering a full year (at least 365 days) to capture seasonal and temporal variations. These FDPs allow us to understand how these variables might behave in the future and to plan accordingly.

In the model proposed in this study, we apply a scenario-based stochastic approach. Here, each uncertain parameter—such as wind speed or electricity price—is discretized into a finite number of representative scenarios, each with an associated probability of occurrence. These scenarios are generated from the FDPs, enabling the model to account for the full range of possible outcomes.

Figure 6 illustrates the configuration of the microgrid that serves as the basis for the case study presented in this work. As shown, the microgrid integrates a variety of generation units, many of which rely on primary energy resources that are inherently uncertain, such as wind and solar radiation. Additionally, electricity demand and power exchange with the main grid also exhibit variable and unpredictable behavior.

Because these elements introduce uncertainty into system operation, it is essential to treat each of them with appropriate analytical rigor. In particular, a detailed analysis of each uncertain parameter is necessary in order to obtain an optimal and reliable solution. This includes not only modeling the variability of renewable resources but also accounting for the dynamic nature of demand and market interactions. By doing so, we can develop a more accurate and resilient energy management strategy tailored to the microgrid’s specific operating conditions.

3.1. FDP Generation for Uncertain Parameters

In most probabilistic analyses involving wind data, the Weibull probability density function (FDP) is the most commonly employed model. This is due to its flexibility and effectiveness in characterizing the variability and statistical behavior of wind speeds over time. The Weibull distribution is defined by Equation (

36), which introduces two critical parameters:

k: the shape parameter, which controls the distribution’s form—essentially, how peaked or flat the curve is.

c: the scale parameter, which determines the spread or “scalability” of the distribution, directly related to the average wind speed.

Similarly, the beta FDP is used for the probabilistic analysis of solar radiation, which is shown in (37), where alpha and beta are distribution parameters that are calculated based on the mean and standard deviation of historical solar radiation data.

To model the load uncertainty parameters and electricity market price, we use the normal FDP, as shown in Equation (38); in this type of FDP, we use the mean and standard deviation for each parameter.

3.2. Scenario Generation

In stochastic modeling, one of the main challenges is that uncertain parameters can theoretically assume an infinite number of values. This makes it practically impossible to solve optimization problems directly when faced with such infinite input spaces. To address this, we must discretize the probability distribution function (FDP) of each uncertain parameter into a finite number of segments, thus enabling tractable analysis.

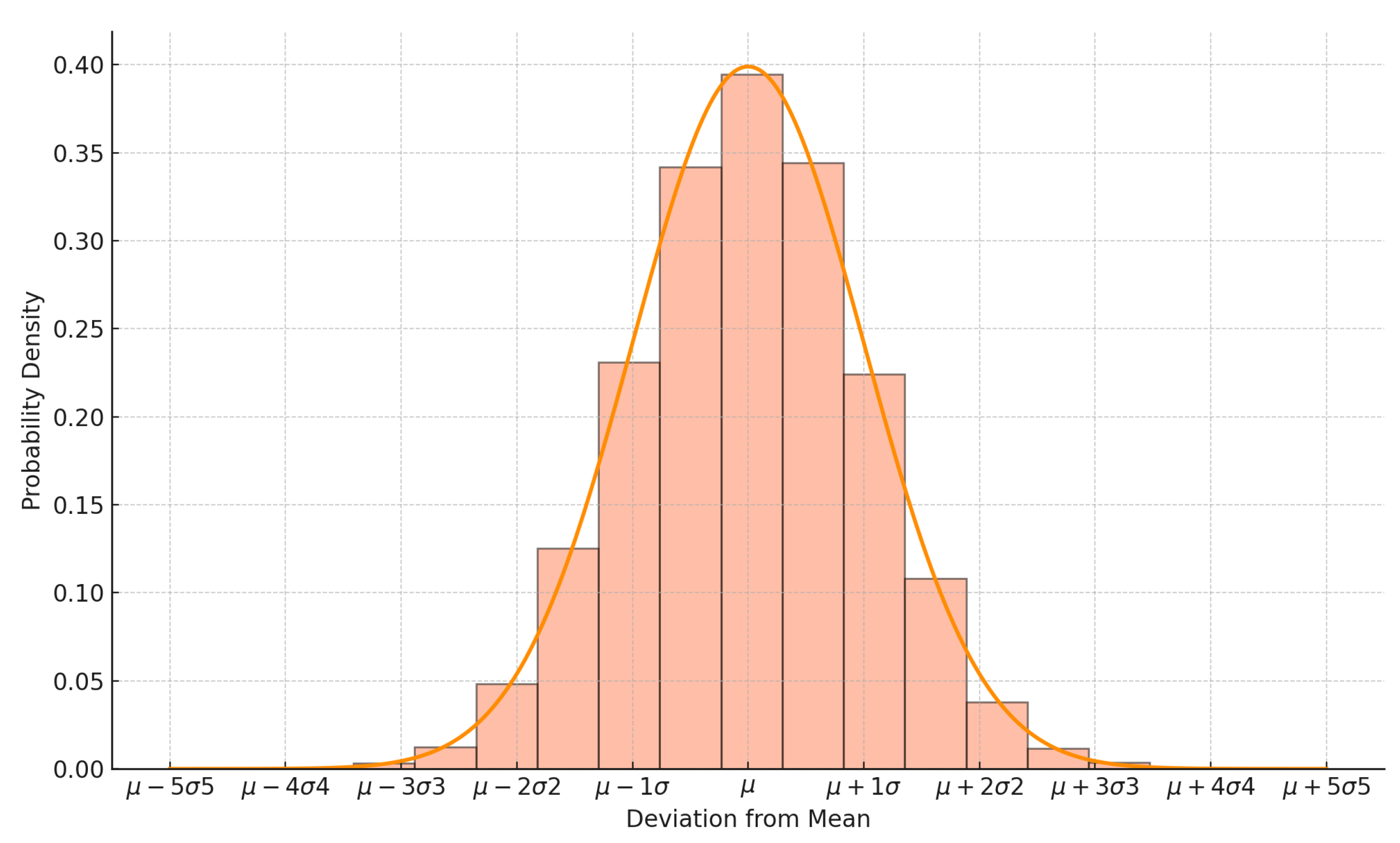

For example,

Figure 7 illustrates how a normal distribution can be discretized into nine distinct segments. Each segment represents a possible value of the uncertain parameter, along with its associated probability. We denote each scenario’s probability and corresponding value for a given uncertain parameter

x as

and

, respectively.

In this particular study, each uncertain parameter—such as wind speed, solar radiation, demand, or market price—is discretized into nine scenarios. However, when dealing with multiple independent parameters, the total number of combined scenarios increases exponentially. For instance, with four uncertain variables, the total number of hourly scenarios becomes . Clearly, solving an optimization problem with over six thousand scenarios would be computationally intensive and inefficient.

To manage this complexity, we implement a scenario reduction method. The goal is to reduce the original set of scenarios to a smaller, equivalent subset that still captures the statistical behavior of the original distributions. In this study, the reduction process is formulated as a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem, where the objective is to minimize the number of scenarios while preserving the overall probabilistic structure.

3.3. Pseudocode Overview of the Proposed Heuristic

The proposed heuristic is built upon the foundation of a two-stage stochastic programming model, designed to compute the operating cost of a microgrid in real time. By leveraging this model, it becomes possible to determine optimal resource allocation across various generation units, taking into account the uncertainty of key parameters—such as renewable generation, demand, and market prices—over short time intervals, .

To achieve this, all stochastic variables are first discretized and standardized, enabling the heuristic to realistically simulate the dynamic behavior of a microgrid. In the context of this case study, the time horizon is broken down into 15 min intervals, allowing for a high-resolution, time-sensitive analysis.

Importantly, this heuristic not only allocates generation resources optimally and computes real-time dynamic prices, but also incorporates a power flow model. This means that it respects all physical and operational constraints inherent to an actual grid, ensuring that the solutions are both feasible and implementable.

3.4. Case Study Design

This study proposes an analysis based on three distinct case studies, each designed to evaluate the performance of the proposed model under different operating conditions:

Case 1: Microgrid connected to the main grid without demand response.

Case 2: Microgrid connected to the main grid with DR, allowing for maximum load variation of 10% and 20%.

Case 3: Islanded microgrid (off-grid mode) with DR, allowing for maximum load shedding of 10%.

For all scenarios, the input data includes 365 days of historical records for key stochastic parameters: electricity demand, wind speed, and solar irradiance. This extensive dataset enables a more realistic representation of system behavior and enhances the reliability of the simulation outcomes. Regarding electricity pricing, the model uses dynamic market prices from the Ontario electricity market, where there is no fixed tariff. Instead, the price fluctuates throughout the day based on supply and demand conditions (Algorithm 1). This reflects a more accurate market-driven environment for evaluating cost optimization strategies in microgrid operation.

Table 2 shows the input parameters of the VEs, necessary to be able to model according to what was mentioned in previous chapters.

| Algorithm 1 Two-Stage Stochastic Dispatch and Real-Time Pricing (compact) |

- Require:

Horizon T (15-min), scenarios with probs , sets ; limits - Ensure:

Prices and dispatch feasible and low expected cost - 1:

Build scenario set - 2:

Wind (Weibull): , , - 3:

Irradiance (Beta): , , - 4:

Demand/Price (Normal): - 5:

Discretize PDFs (9-quantiles/var), form products, reduce via MILP - 6:

Initialize - 7:

; pick ; tolerance - 8:

while do - 9:

Stage 1 (master): choose s.t. - 10:

Stage 2 (per-scenario subproblems): - 11:

for all s ∈ S do - 12:

for all t ∈ T do - 13:

Wind: , - 14:

PV: , , - 15:

CHP FOR (polygon): - 16:

- 17:

- 18:

, - 19:

CHP cost: - 20:

Price-based DR: , , , - 21:

Incentive DR: , , ,, - 22:

EVs (SoC): , , , , , , - 23:

Power balance (per bus j): - 24:

Solve OPF/MILP for scenario s with dispatch , cost - 25:

end for - 26:

end for - 27:

Aggregate expected cost: - 28:

Update prices (projected subgradient): - 29:

- 30:

Stop if: and ; else - 31:

end while - 32:

Objective (compact): - 33:

Output: ,

|

Table 3 shows the input parameters of a CHP generation plant, including the points for the FOR curve, necessary to determine the power delivery of this plant, as well as the efficiency and costs of it. These data are necessary to model according to what was mentioned in previous chapters.

Table 4 shows the power values of each aero generator, as well as the values of starting speed, nominal power delivery, and braking.

Table 5 presents the fixed parameters used to calculate the power output of the photovoltaic system in this case study. The microgrid includes a solar farm composed of 5681 crystalline silicon panels, interconnected to deliver a peak power output of 2.2 MW during periods of high solar availability. These values reflect a realistic utility-scale PV installation and are used to model the system’s contribution to meeting demand under varying irradiance conditions.

Table 5 summarizes the parameters related to DR programs, including the percentage of load subject to DR, as well as the associated costs and incentive values for each case study. Notably, the third case—representing an islanded microgrid operating with DR—shows significantly higher costs compared to Cases 1 and 2. This increase is due to the nature of the DR strategy implemented in Case 3, which is incentive-based and does not benefit from the energy security typically provided by the main grid. As a result, the microgrid must rely entirely on internal resources and load shedding to maintain system stability. While this configuration provides a high degree of operational reliability and autonomy, it also comes with greater economic cost—a trade-off that is important to consider in real-world microgrid planning and design.

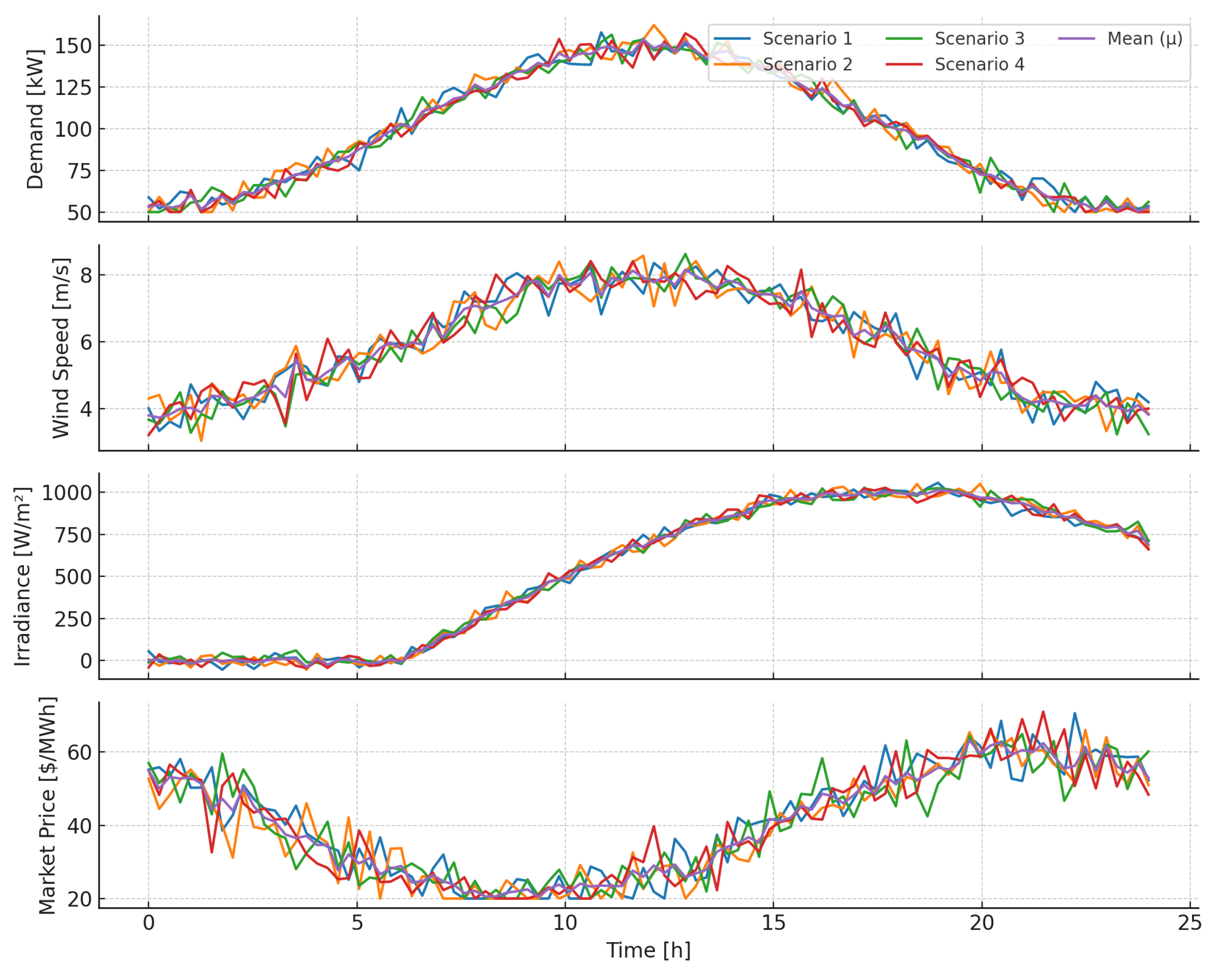

All the input parameters for the different generation technologies that compose the microgrid are detailed in the tables mentioned above. The stochastic variables to be used in the case studies are those shown in

Figure 8.

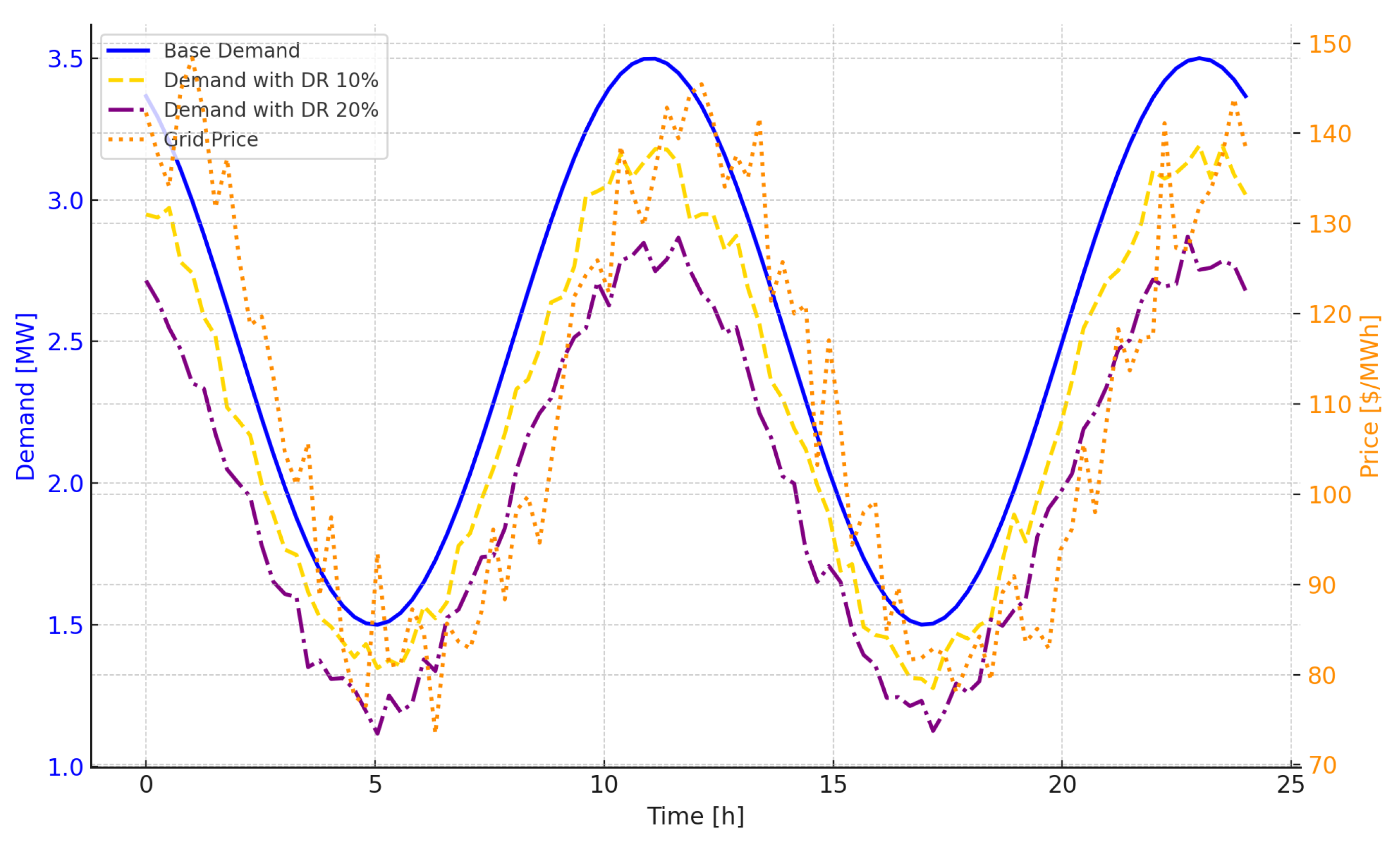

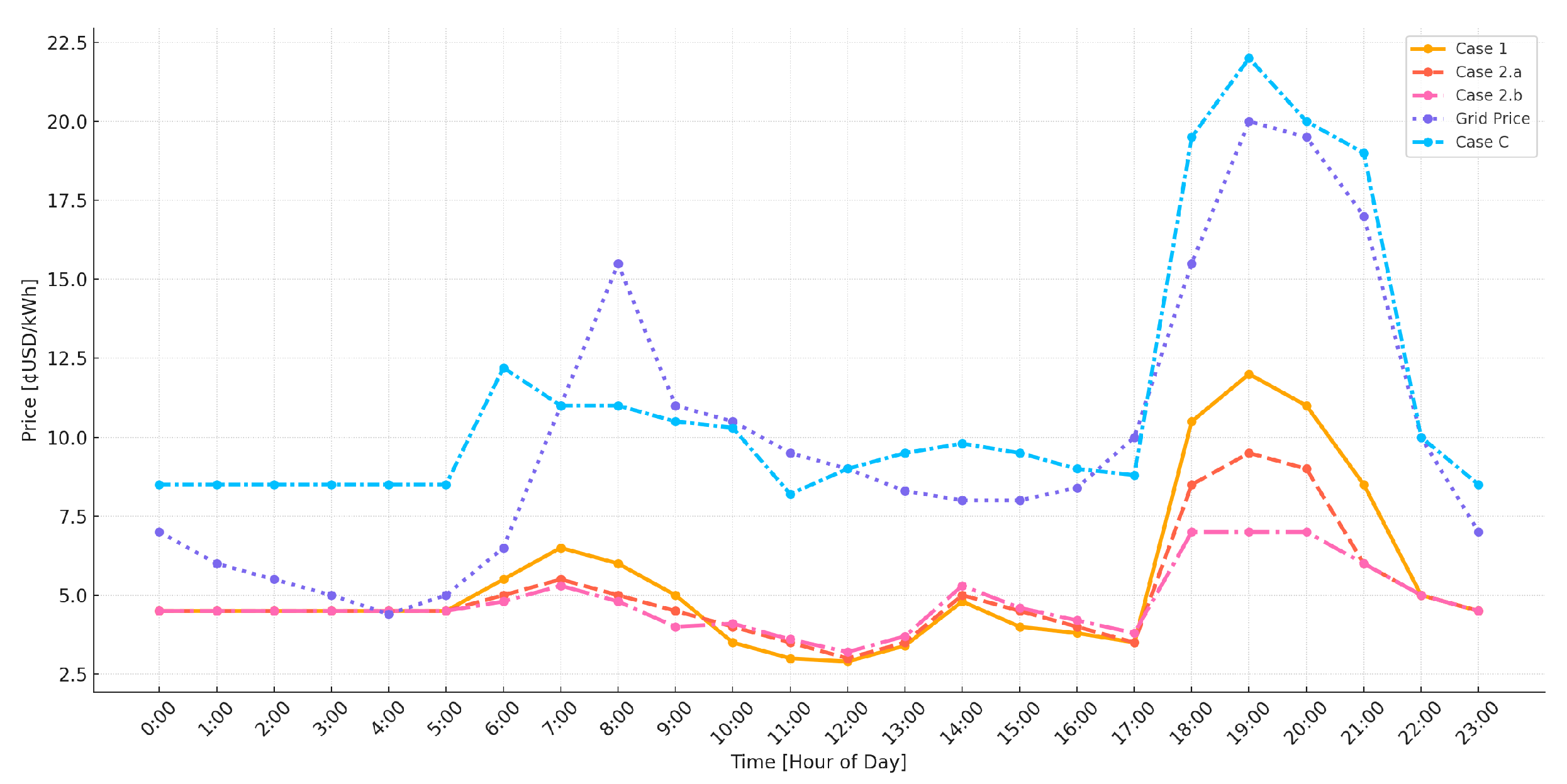

Figure 9 illustrates the demand curves corresponding to all three case studies, clearly showing how DR programs influence load patterns throughout the day. The curves demonstrate how demand fluctuates under different DR strategies—either flattening peaks or shifting load to off-peak hours. Additionally, the figure includes the electricity market price function, which follows a behavior closely aligned with demand levels. As expected in dynamic market environments, electricity prices tend to rise during periods of high demand and drop during periods of low consumption. This direct correlation between demand and price reinforces the importance of DR mechanisms, not only for load balancing but also for cost optimization and operational efficiency within the microgrid.

4. Analysis of Results and Discussion

4.1. Case Study 1: Microgrid Connected to the Main Grid Without Demand Response

In the first case study, we examine the operation of a microgrid that is connected to the main utility grid and operates without the implementation of DR strategies.

Because the microgrid remains grid-tied, it enables the possibility of bidirectional power flow between the microgrid and the upstream utility network. In practical terms, this means that the microgrid can both import energy from the grid when local generation is insufficient and export excess energy to the grid when local generation exceeds demand. This bidirectional exchange plays a key role in maintaining system reliability and economic operation, especially when no DR mechanisms are in place to modulate load behavior.

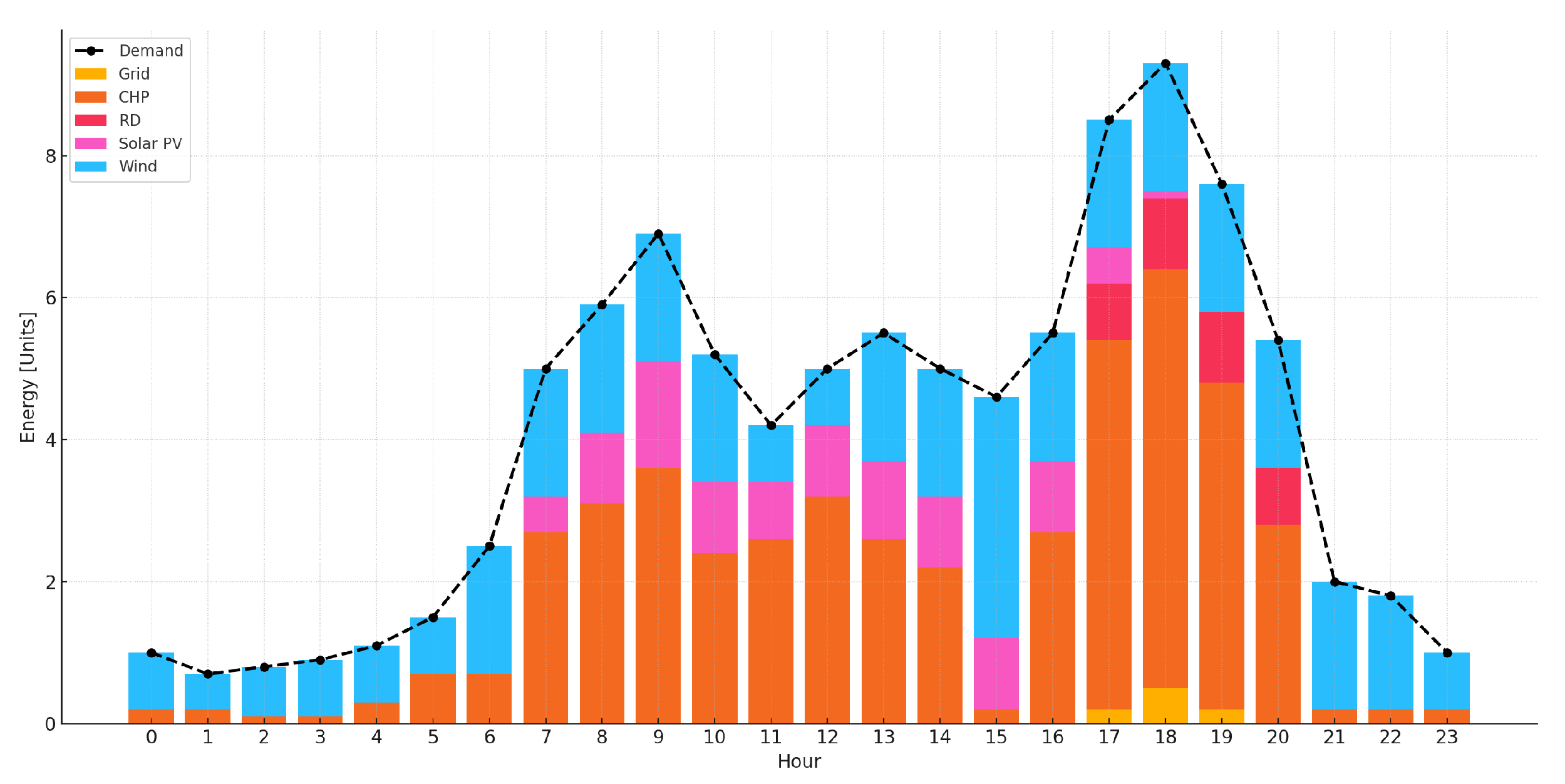

Figure 10 illustrates the energy dispatch profile analyzed in 15 min intervals throughout the day. It can be observed that the microgrid is largely self-sufficient, relying on its internal generation for most time periods. Only during peak demand hours does the system draw small amounts of energy from the main grid. During hours of high solar availability, the photovoltaic plant contributes significantly to the supply—although not at its full nominal capacity, which reflects the inherent uncertainty in the input data such as irradiance and temperature.

The CHP and wind units provide generation consistently throughout the day, although not at constant output levels. Importantly, the grid contributes only modestly to the supply, as the cost of local generation within the microgrid is lower than that of purchasing electricity from the utility.

4.2. Case Study 2: Microgrid Connected to the Grid with Demand Response (10% and 20%)

In

Figure 9, we can clearly see the impact of implementing DR programs on the demand curve. For this scenario, the peak demand is reduced and redistributed—specifically by 10% and 20%—to periods of lower demand, also known as valley hours. This adjustment leads to a flattening of the overall demand profile, effectively reducing stress on the main grid and enhancing system stability and efficiency.

In

Figure 11, we observe how the microgrid demand is primarily met by internal generation units, with a noticeable shift in load between 18:00 and 22:00. This shift corresponds to the implementation of a 10% DR program, which redistributes a portion of the peak load to off-peak hours. As a result, the microgrid’s dependence on the main grid is significantly reduced, with grid imports dropping to nearly zero during these intervals.

The solar photovoltaic (PV) system increases its share of power supply compared to the previous case, as does the CHP unit. The wind power plant, however, maintains a similar dispatch profile, indicating consistent generation based on prevailing wind conditions.

In contrast, when a 20% DR program is applied—shifting an even larger portion of peak demand to valley hours—we observe further optimization of the system. As shown in

Figure 12, the demand curve becomes more stable throughout the day, contributing to a reduction in the microgrid’s total operating cost. In this scenario, the grid’s contribution is effectively eliminated, as local generation is sufficient to meet all demand.

While the CHP unit continues to operate throughout the day, it does so at lower output levels than in the 10% DR scenario, reflecting the reduced overall energy requirement during peak hours. Interestingly, wind generation increases its contribution, while the PV system maintains a similar output pattern as observed in the previous case. Together, these adjustments highlight how DR programs can enhance efficiency and reduce reliance on external energy sources.

Case Study 3: Islanded Microgrid with 10% Load Shedding through Demand Response. In this third scenario, the microgrid operates in island mode, meaning that it is fully disconnected from the main utility grid. Additionally, a price-based DR program is implemented, allowing for up to 10% load shedding, in accordance with a three-tiered contractual agreement.

When the microgrid is isolated, it is entirely responsible for meeting its own demand using only its internal generation resources. However, due to generation capacity constraints, the system cannot always satisfy the full demand. To maintain operational integrity, it is therefore necessary to shed or disconnect a portion of the load, limited to 10% as specified by the DR contract. While this strategy ensures system stability, it comes at the cost of increased operational expenses, particularly due to penalties or opportunity costs associated with unserved energy.

As shown in

Figure 13, even after applying the allowed DR-based load shifting, the microgrid is still unable to fully meet demand between 18:00 and 22:00, leading to energy shortfalls. These shortages contribute directly to an increase in total operating costs, as both the cost of unserved energy and the cost of load shedding must be accounted for in the system’s economic performance.

Based on the analysis conducted for each case study, it is essential to examine the operating costs incurred by the microgrid under the conditions unique to each scenario.

Figure 14 provides a summary comparison of these costs, reflecting the operational constraints and performance of the microgrid in each case.

In Cases 1 and 2a, the microgrid is connected to the utility grid, and while it maintains overall costs lower than the market price, there are notable increases in operating expenses during certain periods. These spikes are attributed to the import of electricity from the grid during high-price hours, which raises the average cost of energy supplied by the microgrid during those intervals.

In contrast, Case 2b, which incorporates a 20% demand response program, shows the lowest overall operating cost. This efficiency is due to the successful shifting of peak demand to off-peak hours, enabling the microgrid to rely entirely on its internal resources even during peak times. As a result, there is no need to import expensive energy from the grid, and the marginal cost of operation is determined solely by the microgrid’s own generation assets, leading to significant cost savings.

However, when evaluating Case 3, where the microgrid operates in island mode with 10% load shedding, the cost profile changes significantly. In some time periods, the operating cost matches or even exceeds the grid market price. Two key factors contribute to this outcome: The microgrid must activate all available generation units to meet demand, resulting in higher operational costs due to the simultaneous operation of multiple resources. The presence of unserved energy during peak hours contributes to the cost burden, as penalties or estimated losses associated with unmet demand further increase the total operational cost.

Figure 14 presents the temporal evolution of marginal electricity prices across five operational scenarios: a grid-connected baseline without demand response (Case 1), grid-connected microgrids implementing 10% and 20% price-based DR (Cases 2a and 2b), an islanded configuration with incentive-based DR (Case C), and the external wholesale market price as a benchmark (Grid Price). The comparison spans a 24 h horizon with 1 h resolution, capturing dynamic price signals driven by load variation, resource availability, and DR participation.

The observed trends underscore the economic impact of demand-side flexibility. Case C exhibits the highest marginal prices, particularly between 18:00 and 21:00, reflecting elevated operational stress under islanded conditions and limited dispatchable capacity. Case 1 also shows a sharp price increase during evening peak hours, albeit moderated by access to grid imports. In contrast, Cases 2a and 2b exhibit significantly flattened price curves throughout the day. Notably, Case 2.b maintains the lowest marginal costs due to more aggressive load shifting, which alleviates peak demand stress and optimizes the dispatch of local generation units.

The proposed method achieved a 12.4% cost reduction compared to the deterministic baseline and increased renewable utilization by 17.9%. A sensitivity analysis revealed that cost savings remain above 10% even when uncertainty in generation increases by 20%, demonstrating robustness and scalability of the proposed approach.

Although the proposed model effectively integrates stochastic optimization and dynamic pricing, its scalability is limited for large-scale multi-microgrid systems. Future research will focus on developing hybrid stochastic–robust models, integrating data-driven scenario reduction, and exploring decentralized optimization schemes for cooperative microgrids.

5. Conclusions

The analysis confirms that DR programs exert a measurable influence on the operational and economic performance of microgrids. In particular, Case 2.b—featuring a 20% load-shifting DR scheme—achieved the most cost-efficient dispatch configuration by enabling complete peak-hour demand coverage through local resources, without resorting to grid imports. In contrast, Case 3, which modeled an islanded microgrid with incentive-based DR, incurred the highest operating costs, driven by forced full-capacity utilization and unmet load penalties. These findings underscore the need to incorporate demand-side flexibility and anticipatory control mechanisms to maintain cost efficiency and grid resilience, especially under constrained operating conditions.

Case 1 examined a grid-connected microgrid operating without DR, where internal generation—comprising solar PV, wind, and CHP units—satisfied more than 85% of daily demand. Grid imports were limited to peak intervals, comprising less than 15% of the total energy mix. The dispatch strategy favored local generation due to lower marginal costs, yielding a robust and economically viable outcome. However, the absence of demand-side flexibility constrained further optimization. These results suggest that integrating DR programs and predictive control mechanisms could enhance both operational adaptability and system robustness, particularly under variable market and resource conditions.

The results from Cases 2.a and 2.b, which implemented price-based DR strategies with 10% and 20% load shifting, respectively, demonstrated the effectiveness of temporal load redistribution in flattening demand peaks. In both cases, DR significantly reduced dependence on external grid energy; in Case 2.b, grid interaction was fully eliminated. The system operated predominantly on renewable sources, with CHP units functioning in partial-load mode, resulting in optimized fuel usage and reduced marginal cost. These findings validate the effectiveness of price-responsive DR programs in improving system efficiency, lowering operational costs, and maintaining service reliability under dynamic pricing conditions.

In Case 3, the islanded microgrid operated under a contractual, incentive-based DR scheme that permitted up to 10% load shedding. While the model maintained internal autonomy, it faced significant limitations during evening peak hours (18:00–22:00), when local generation proved insufficient to meet demand, even under maximum curtailment allowances. As a result, operational costs escalated due to overutilization of generation assets and energy-not-supplied penalties. These results reveal the operational fragility of isolated systems and underscore the need to integrate distributed energy storage, enhance local generation flexibility, or adopt hybrid DR–storage coordination schemes to maintain secure and cost-effective islanded operation.

Although the proposed framework demonstrates strong performance in optimizing real-time microgrid operation under uncertainty, several limitations must be acknowledged. The model assumes ideal communication conditions and does not account for delays or measurement errors that may arise in practice. Moreover, energy storage systems are not yet integrated into the optimization process, which could enhance operational flexibility. While the scenario reduction method improves computational efficiency, its scalability for large-scale multi-microgrid systems remains to be examined. Future research should focus on extending the model to include storage–demand response coordination, data-driven scenario generation using machine learning, and decentralized control strategies to strengthen resilience and applicability in complex smart energy systems.