Abstract

Efficient control a system of multiple Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) is crucial for modern intralogistics given the growing importance of energy consumption and operating costs. This study investigates the impact of two deadlock handling methods: Chain Of Reservations (COR) and Structural On-line Control Policy (SOCP), on the energy efficiency and performance of AGV systems operating in a production environment described as square topology. A simulation model developed in FlexSim implemented both methods using real AGV data on electricity consumption during various tasks. The analysis also discusses the adopted battery charging strategy. Simulation experiments combined each deadlock handling method with two path-planning strategies: shortest path and fastest path. Pseudocode algorithms for determining these paths in an environment described as square topology are provided. System performance was evaluated across a wide range of AGV fleet sizes, focusing on key indicators such as total energy consumption, time to complete transportation tasks, and AGV utilization rate. Multi-criteria optimization reduced the problem to two conflicting objectives: energy consumption and completion time, with Pareto fronts generated for each configuration studied. The results demonstrate that both the deadlock handling strategy and the selected pathfinding algorithm significantly influence the evaluation criteria. This original research integrates solving the deadlock problem with controlling energy efficiency and task completion time in structured transportation environments that are not deadlock-free by design.

1. Introduction

The 2023 International Energy Outlook [1] summarizes long-term energy trends worldwide. It indicates a sustained long-term increase in energy consumption. Global total energy consumption was about 445 EJ in 2023, with the industrial sector accounting for the largest share (39%), followed by buildings (including appliances) (28%) and transportation (27%) [2]. An overview of issues related to optimizing energy use in transportation is presented in [3], which focuses on road, rail, sea, and air transportation. Among other aspects, it discusses approaches that contribute to reducing emissions and energy consumption. One of the identified trends in optimization is the shift from a single-criterion approach, which only minimizes the cost of transportation operations, to a multi-criteria approach that also considers additional measures of evaluation. With the growing importance of transportation activities, the optimization of energy consumption is becoming increasingly relevant [4]. This applies not only to global sectors such as road, rail, sea, or air transport, but also to transport tasks carried out in material handling, which is a key part of intralogistics.

A crucial aspect of implementing AGV or AMR mobile robots in intralogistics is their growing potential for sustainable development, particularly in terms of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. According to [5], the use of mobile robots helps reduce energy consumption and CO2 emissions compared to combustion vehicles, mainly through broadly understood trip optimization. Similar conclusions are presented in [6], where the authors emphasize that optimizing mobile robot routes has a fundamental impact on reducing both emissions and costs. They calculated CO2 emissions for a test AMR before and after route optimization, demonstrating a significant reduction in emissions. The article also highlights an additional environmental challenge related to e-waste. It should be noted, however, that the benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions depend on local conditions and the emission factor [7]. For example, according to [8], the CO2 emission factor for electricity available to end users in Poland was 597 kg CO2 per MWh in 2024. In comparison, the average across all EU countries was below 300 kg CO2 per MWh in 2019. Despite the growing share of renewable energy sources, these emission factors remain very high. Therefore, optimizing energy consumption at every stage of the production process is essential. One way to achieve this is by introducing new methods of AGV fleet management.

Recent research on the energy consumption of AGVs has primarily addressed the development of models. These models are utilized to enable precise prediction and analysis of energy consumption. Physical and parametric models have been developed to capture the variation in energy use across different phases of motion. These models include drivetrain losses and rolling resistance [9]. Specifically adapted for AGVs with empirical calibration, the efficacy of these models has been demonstrated in [10]. Furthermore, data-driven and machine learning methodologies facilitate real-time prediction. As demonstrated in [11], the optimization of telemetry signals enhances estimation accuracy. Moreover, the work [12] presents findings that support the implementation of IIoT-based battery forecasting as a strategy for fleet management. The energy consumption of these vehicles is found to be significantly influenced by the vehicles’ motion profiles. As demonstrated in [13], the acceleration and deceleration processes have a substantial impact on energy consumption, with optimized speed profiles resulting in a notable decrease in energy demand. It is noteworthy that the work [14] conducted experimental investigations to analyze the energy consumption of AGVs in warehouse environments, providing valuable empirical data that informs the development of more precise models. The integration of physical and machine learning models has been demonstrated to have the potential to enhance the accuracy of energy efficiency predictions in AGV operations.

Automated guided vehicles and autonomous mobile robots play an essential role in intralogistics, as they are used to transport materials in factories, warehouses, distribution centers, and automated container terminals. They contribute to increased competitiveness by improving productivity, accuracy, and safety, while reducing labor costs. The use of AGVs, particularly in repetitive tasks, also results in lower energy consumption compared to traditional manual systems. The article [15] presents a timeline of the development of AGVs and AMRs since the introduction of these technologies. Important development milestones are illustrated with relevant examples and photos. Autonomous mobile robots offer greater flexibility and adaptability to dynamic environments than AGVs, which follow fixed paths. AGVs are, therefore, typically used for repetitive tasks in structured environments, while the more expensive and advanced AMRs can also be deployed in unstructured and dynamic environments. A transportation system made up of multiple AGVs can perform various control and management tasks. A comprehensive survey of these tasks can be found in review articles [16,17,18,19,20]. The control process of AGV systems involves a number of essential tasks, including: dispatching, routing, scheduling, handling collisions and deadlocks, as well as positioning idle vehicles and ensuring their recharging and maintenance. Decisions about sending out orders, planning routes, and scheduling can be made at the same time or separately [16]. A paper [21] suggests that control tasks should be divided into these categories: task allocation, location, path planning, motion planning, and vehicle management. In this proposal, motion planning includes collision and deadlock handling. Furthermore, these management and control tasks apply to both single-loaded [18,21] and multi-loaded [22,23] AGV systems.

From the perspective of production processes, the transportation system is an auxiliary system that consumes resources and generates additional costs. However, its performance in efficiently performing transportation tasks has a significant impact on the efficiency and flexibility of production processes With this in mind, the AGV system control problem can be formulated as a single or multicriteria optimization problem with constraints. The most common maximized objectives are system throughput and AGV utilization. The minimized objectives are the time needed to perform all tasks (makespan), vehicle travel time, total cost of movement, total energy consumption, time handling loads beyond expected times, delivery time, AGV travel time to destinations of new tasks, and expected waiting times for loads.

In order to carry out optimization, it is necessary to consider the methods that can be used. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms represent a significant contemporary trend within the domain of optimization techniques. Recent review articles have analyzed the application of these algorithms in various areas, including Building Energy Optimization (BEO) [24] and Home Energy Management Systems (HEMS) [25]. Evolutionary algorithms and swarm intelligence play a particularly important role in this context. These reviews underscore the significance of metaheuristics, encompassing Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO). It has been demonstrated that these metaheuristics possess the capacity to efficiently search vast solution spaces, while concurrently accounting for a variety of constraints and objectives. Another intriguing nature-inspired proposal is Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO) [26], which emulates the social structure and hunting behavior of gray wolves in their natural environment. It has been demonstrated that GWO possesses the capacity to address a multitude of challenges, including the determination of the parameters associated with overhead transmission lines [27]. The most recent metaheuristic Hybrid Grey Wolf-Particle Swarm Optimization (HGWPSO) algorithm integrates two methodologies: GWO and PSO [28]. The integration of the exploratory capabilities of GWO with the rapid convergence and operational efficiency of PSO facilitates the effective resolution of various problems, including the reactive power planning issue.

A significant application of optimization in multi-AGV systems is path planning. The most prevalent and widely implemented algorithm is A* and its various modifications. A comprehensive overview of these algorithms can be found in [29]. A more intricate task related to path determination in multi-AGV systems is to calculate collision-free paths for multiple AGVs moving from a starting point to a destination. This problem is referred to as Multi-Agent Path Finding (MAPF). A comprehensive overview of methods for solving the problem of coordinating the actions of multiple agents representing AGVs can be found in [30]. This work on the MAPF problem also contains references to many previously published review articles on this topic. The present problem is addressed through the application of two broad categories of solutions: first, standard algorithmic solutions; and second, dynamically developing methods employed in the domain of artificial intelligence. In the classic MAPF model, the path structure is modeled as an undirected graph , where V is a set of vertices (possible locations occupied by AGVs), and E is a set of edges representing permissible paths between these locations. During task execution, each agent must navigate from the initial to the final position on the graph while evading collisions with other agents. The criteria employed are as follows: makespan—minimizing which reduces the longest execution time of all tasks; and the total cost incurred by all agents—minimizing which corresponds to minimizing the average cost per agent. Lifelong MAPF represents an extension of the classical approach. In the context of the present model, following the attainment of the inaugural objective, the agents have the capacity to be allocated to novel tasks, or alternatively, the introduction of additional agents into the system is a possibility. However, the assessment of the efficacy of these algorithms is only possible through the utilization of test problem sets. The paper [31] presents benchmarks that facilitate the comparison of the effectiveness of the developed MAPF algorithms. The classic MAPF formulation poses significant challenges in its practical application for numerous manufacturing companies employing AGV systems. In [31], in the section entitled “From Pathfinding to Motion Planning,” a number of assumptions employed in MAPF were examined in the context of production systems. However, from a contemporary standpoint, the advancement of classical methods used by MAPF, such as search- and compilation-based methods, as well as the development of learning-based methods, including reinforcement learning, indicate a change in perspective. Rather than perceiving these methodologies as competitive, it would be more appropriate to regard them as complementary hybrid methods [30]. This paradigm shift could lead to significant progress in the future, including the resolution of numerous intractable practical problems in applications, such as those related to transportation in production systems.

The problem of controlling a multi-AGV system as a single- or multi-criteria optimization task requires thinking about the constraints that will appear in the model. The constraints [16,17,21] used in the optimization task can be divided into five areas: time, resources, priority, capacity, and domain. Resource constraints pose the greatest challenge to researchers. In transportation, resources refer to the routes and the AGVs that travel along them. Concurrent processes in discrete event systems often encounter resource conflicts that prevent them from completing their tasks. This phenomenon, known as deadlock, has attracted considerable attention in computer science, network communications, and manufacturing systems [32]. Deadlock is caused by the formation of a closed chain of processes, wherein each process waits for a resource held by the next process in the chain. Any method that prevents the formation of such a chain is an effective solution for addressing deadlock in these systems. There are three predominant approaches to deadlock management [33]:

- The process of deadlock detection and resolution entails the identification and subsequent resolution of deadlocked states in real-time;

- The process of deadlock prevention entails the determination of offline resource allocation capabilities;

- The process of deadlock avoidance involves the strategic management of resource allocation through the online analysis of current state information.

The first approach to dealing with deadlocks—allowing them to occur—cannot be considered appropriate for modern transportation systems. The second method, deadlock prevention, employs well-established principles of resource allocation, such as the all-or-nothing approach. In this approach, only processes for which all necessary resources can be reserved at the outset are executed. Another principle posits that resources are allocated in ascending order according to their numbering. The simplicity of these methods is a key factor in their widespread industrial use, despite the drawback of low resource utilization. The third method, deadlock avoidance, is of a different nature. In this case, it is necessary to determine in advance whether the allocation of specific resources will result in a deadlock or in a state that will inevitably lead to one. This requires verifying the liveness of the system. If a deadlock, or a situation leading to it, is detected, the allocation of the requested resources is denied.

The deadlock avoidance strategy is characterized by a reduced level of resource allocation, achieved at the expense of increased computation time. The issue of deadlock in a transportation system must therefore be evaluated from the standpoint of the efficiency of the algorithm employed. This efficiency is typically assessed from two perspectives: time complexity and the number of achievable states. Clearly, the complexity of an algorithm is directly correlated with the number of states: more restrictive algorithms result in fewer states. Determining the set of achievable states for real-world tasks is challenging and requires estimating efficiency in terms of the number of processes that can be executed simultaneously. While a clear relationship exists between the number of concurrent processes and the efficiency of the transportation system, it must be acknowledged that implementing a more efficient algorithm does not necessarily guarantee improved performance of the control process. The effectiveness of a transportation system depends on numerous additional factors. Deadlock, as a critical feature of discrete-event systems executing concurrent processes, has a notable impact on the efficiency of automated transport in production environments. Research in this domain focuses on optimization processes based on temporal, resource, and cost criteria.

In light of the growing importance of energy efficiency driven by environmental considerations, it is essential to examine studies that incorporate energy efficiency into multi-criteria optimization tasks for systems employing multiple AGVs. The literature review conducted in this work led to the identification of a research gap, specifically concerning the influence of deadlock handling methods on energy consumption and other performance criteria in such systems. The remainder of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a review of recent literature, limited to the past decade due to the dynamic nature of the research area, which forms the basis for defining the research gap. Section 3 introduces the concept of the AGV working environment. The considered environment is characterized by a square topology, understood as a structural arrangement of elements forming a square-like layout. This section also discusses deadlock handling methods, outlines path generation algorithms used to determine optimal travel routes, and clearly states the research problem addressed in this study. Section 4 describes the parameters of the mobile robot used in the simulation experiments. Section 5 provides a detailed description of the simulation experiments, including the setup, transport tasks, configuration options for the AGVs, and the method applied for analyzing energy consumption. Section 6 presents and discusses the results obtained. Section 7 summarizes the main findings of the research. Finally, Section 8 outlines possible directions for future work.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Search Areas

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the development of energy-efficient AGVs by researchers and manufacturers, with a concomitant focus on optimizing their performance. These optimizations have addressed various issues, including minimizing travel distance and idle time, maximizing battery life and minimizing recharging time, as well as efficiently recovering energy during braking and storing it in batteries. As intralogistics systems evolve to encompass a greater number of AGVs and more complex routes, the optimization of energy consumption assumes paramount importance in ensuring operational efficiency and mitigating operating costs. Consequently, it is advantageous to incorporate this metric into a multi-criteria control analysis of a transportation system comprising a fleet of AGVs at varying stages of control and management.

This analysis encompasses the fleet’s various application areas. In identifying the research gap, the investigation focused on key areas related to energy-efficient AGV fleet control. The primary objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive review of the extant literature pertaining to two distinct areas: energy-efficient AGV scheduling and energy-aware route planning. A thorough review of extant literature indicates that both areas are directly related to the issue of managing deadlocks. Consequently, a meticulous analysis of extant literature was conducted, with particular attention directed toward the manner in which authors approach energy consumption from the perspective of deadlock handling. This targeted search identified publications that treat these issues as important aspects for assessing the efficiency of AGV fleet operation. A review of extant works in both areas, along with a summary and identification of research gaps, is presented in Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4.

2.2. Energy-Efficient AGV Scheduling

The paper [34] analyzed the problem of flexible job shop scheduling, taking into account energy consumption and transportation time, and formulated a comprehensive mathematical model. A methodology based on integer programming was utilized in order to optimize four distinct objectives. The aforementioned objectives included the maximum completion time, total energy consumption, load on critical machines, and penalties for tardiness. A proposed solution to the problem was presented in the form of an evolutionary algorithm utilizing reinforcement learning. The subject of the article [35] was the problem of flexible job shop scheduling with a peak power constraint taking into account setup and transport time. To solve the problem, a mathematical model was developed and an improved genetic algorithm for non-dominated sorting was proposed. Minimization of maximum completion time and minimization of total energy consumption were used as optimization criteria. The importance of acknowledging peak power as a hard constraint in urgent orders was underscored. This constraint necessitates a trade-off between order completion and electricity cost. In the paper [36], a multi-criteria optimization model was developed to minimize energy consumption and production time for the flexible scheduling problem of a production shop with transportation constraints. The aggregate energy expenditure comprises the following components: the initial energy consumption during configuration, the energy consumption during processing, residual energy consumption, transportation energy consumption, and auxiliary energy consumption. To address this challenge, an enhanced genetic algorithm was devised to identify optimal solutions. The job shop scheduling problem in an AGV-based manufacturing plant with battery constraints was the subject of the research presented in the article [37]. A meta-heuristic approach based on the General Variable Neighborhood Search (GVNS) algorithm was proposed, facilitating the preservation of economic viability in power cell optimization, concurrently achieving substantial energy consumption reduction. The developed AGV fleet scheduling ensures minimization of task completion time and optimization of battery utilization. The paper [38] addresses the problem of scheduling automatic guided vehicles (AGVs) in a flexible manufacturing system consisting of multiple flexible manufacturing cells with various material handling needs and time constraints. A dual objective mathematical model was developed to simultaneously minimize the total tardiness and energy consumption in the AGV system. To address this challenge, a hyper-heuristic algorithm was employed, leveraging a Double-Deep Q-Network (DDQN) framework with double decision network structures and multiple operators. In [39], the energy-efficient scheduling problem of a flow shop with blocking constraints and collision-free and deadlock-free transportation was studied. A multifaceted, integrated, energy-efficient scheduling model was meticulously engineered. This sophisticated model was developed for the purpose of simultaneously reducing total energy consumption and maximum completion time. An energy reduction algorithm was developed to enhance the generated solutions and achieve enhanced performance by adjusting the velocity of the AGV and obtaining a new schedule with reduced total energy expenditure but unchanged execution time. The problem was addressed by employing an enhanced ant colony algorithm. In [40] an evolutionary algorithm was applied to the multi-criteria optimization of a flexible Mobile Robot (MR) workshop schedule. Two criteria were adopted: makespan and Total Energy Consumption (TEC), which are subject to minimization. The TEC criterion applies not only to MRs, but also to the machines used, which have the ability to perform their tasks at different times. The shorter their operating time, the higher the energy consumption. The problem of flexible scheduling of work in a manufacturing plant, taking into account both transportation time and deterioration effect, was addressed in [41]. A mathematical model was developed to optimize the total energy consumption. To solve the problem, an Animal Migration Optimization (AMO) algorithm, originally used for continuous problems, was modified so that it could be applied to a discrete scheduling problem. The paper [42] tackles the issue of dynamic flexible job shop scheduling in the context of constrained transportation resources, with the objective of minimizing makespan and total energy expenditure. A multi-criteria optimization model was developed with objective and constraint functions that take into account the possibility of disturbances. The application of deep learning with reinforcement, in conjunction with the development of a Hybrid Deep-Q Network (HDQN), has yielded notable advancements. This HDQN is a synthesis of a deep-Q network and three extensions. In [43], a mixed-integer programming model with an innovative energy replenishment policy was developed for efficient scheduling of AGV operations in container terminals. It combines battery swapping with opportunity charging to ensure smooth and timely container operations while maximizing resource utilization and minimizing costs. To reduce the computational complexity of the model, a Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) algorithm was used to reduce the number of integer decision variables using heuristic methods. A decision support system that is able to support the decision making activities on the shop floor in the case of a production disruption has been addressed in [44]. It facilitates the automated adjustment of both AGV and machine schedules within the framework of flexible manufacturing systems. This paper presents a decision support system designed to offer numerous scheduling solutions in response to production disruptions. The system automatically detects an anomalous production occurrence and provides a set of strategies for the rescheduling of production activities. These strategies are designed to maximize just-in-time delivery performance and minimize on-time AGV energy consumption. The study posited the assumption that two-way paths would be converted into two one-way paths to avoid potential deadlocks. The paper [45] analyzes a scheduling problem in automated container terminals with the objective of minimizing energy consumption while preserving competitive makespan. In addressing the scheduling problem, the focus is on optimizing both task sequences and execution times. This objective is achieved by formulating a two-criteria optimization problem based on a flow shop representation. The criteria under consideration are the execution time, also referred to as “makespan,” and the kinetic energy consumption during container transport. A modified genetic algorithm is employed to address the optimization problem. A proactive–reactive scheduling framework based on the digital twin was introduced in paper [46] to solve the complexity and uncertainty of the integrated scheduling problem of multiple port facilities. Preliminary experimental findings indicate that the implementation of the digital twin framework approach results in substantial enhancements in terms of efficiency and energy conservation when compared to conventional scheduling methodologies.

It is noteworthy that in the aforementioned works on energy-efficient AGV scheduling, the authors disregard the possibility of deadlocks, utilize deadlock-free transport structures [39], or simplify their models by modifying them to deadlock-free ones by replacing a bi-directional path with a single unit capacity into two unidirectional paths across the routing topology [44].

In summary, in the literature on energy-efficient AGV scheduling, authors use modern heuristic optimization algorithms. These include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), various versions of genetic algorithms, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) methods such as deep reinforcement learning. These algorithms are used to solve the complex problem of mixed integer nonlinear programming.

2.3. Path Planning with Energy Considerations

The paper [47] proposes a methodology that integrates a routing and scheduling algorithm with a simple strategy that reduces energy consumption and other performance indicators, including makespan, maximum tardiness, and sum of tardiness. It was shown that the optimization method reduces the travel speed, while the mentioned performance indicators are still better than those obtained by the original traffic controller. In the article [48], an optimization model for the path planning of a multiload AGV performing multiple transportation tasks in a manufacturing workshop was formulated. Transport distance and energy consumption were used as optimization criteria. A two-step approach to solving the model was presented. In the initial phase, data concerning optimal pathways between any two nodes associated with transportation tasks was collected. In the subsequent phase, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was employed to ascertain the optimal sequence in which to execute pick-up and delivery operations, and to select the optimal transportation pathway to perform each pick-up/delivery operation concurrently. In [49], an Energy-efficient AGV Path Planning (EAPP) model, herein referred to as the EAPP model, was developed. This model concurrently considers the transportation distance and energy consumption for a solitary AGV load in a manufacturing workshop environment. Two methodologies have been advanced to address the EAPP model. One of these models is based on a two-stage optimization strategy, while the other is based on particle swarm optimization. The study showed that the use of AGVs with multiple loads can help improve the efficiency of workshop logistics. An interesting approach to path planning for a mobile robot is presented in [50], where the motion environment is first discretized into squares according to Moore’s neighborhood. In this approach, a digital Building Information Modeling (BIM) is used to generate both a spatial map and semantic information about objects, allowing effective consideration of the working environment’s specifics. Based on this information, a route is then determined on the resulting graph using the Multi-Heuristic A* (MHA*) algorithm, Artificial Potential Fields (APF), and Large Language Models (LLMs) for dynamic obstacle avoidance. Route planning for multiple AGVs in a chessboard-like warehouse was addressed in [51]. The developed algorithm improves the performance of classical Q-learning algorithms and significantly speeds up dynamic route planning. It allows not only to finding all shortest routes from the start node to the destination node, but also to finding the route with the lowest energy cost, taking into account the number of turns along the route. The improved algorithm also takes into account whether the AGV is loaded or unloaded. Based on the time window, an improved online collision-free multi-AGV route planning algorithm based on the Q-learning algorithm is proposed. Reference [52] highlights the importance of AGV energy consumption forecasting and optimal route planning in a changing industrial environment. It proposes the use of artificial intelligence, including machine learning, to predict energy consumption. The subject under discussion in article [53] pertains to the implementation of digital twins and deep reinforcement learning in addressing the problem of AGV dispatching and routing. The paper proposes an optimization framework that employs a digital twin model of a production shop floor. This model functions as a simulation environment for deep learning. The decision-making environment is constructed on the foundation of a multi-agent system. The study examines AGV dispatching and battery replacement, taking into account conflict-free routes determined using the A* algorithm in a static environment. A dynamic collision avoidance agent is responsible for avoiding dynamic collisions while preventing the occurrence of congestion or deadlock. The applied optimization criteria are average delays and average energy consumption during the execution of transport tasks. An adaptive optimization framework was implemented, integrating reinforced deep learning and digital twin enhancements. This framework utilizes data from the system’s real component to ensure its efficacy. To effectively solve the optimization problem, an improved dueling double deep Q network algorithm was developed, which simultaneously meets the key requirements for performance and adaptability. The paper [54] presents a novel dynamic assignment of transport orders to a fleet with an energy minimization criterion in the internal transportation system of a printing company. The proposed approach is the first solution presented in the literature for the assignment and scheduling problem for a fleet of mixed autonomous and manually operated internal transport vehicles with an objective function focused on energy savings. The efficacy of the proposed approach was assessed through the utilization of a simulation model that integrates classical simulation components and optimization techniques. A model for evaluating the energy demand of AGVs during traffic is presented in [55]. A proposed enhancement to the linear path layout involves the introduction of an improved layout. A conflict-free routing algorithm was proposed for this layout by formulating the necessary conditions to be met. An evaluation was conducted to ascertain the energy efficiency of the AGV. The calculation was performed to determine the lower boundary of the energy required by all AGVs to perform tasks in a linear path layout and the upper boundary of the required energy. The paper [56] considered the task of receiving and delivering multiple products in stereoscopic warehouses or depots. A particle swarm optimization algorithm was used. The optimization criterion was the minimization of energy consumption at different load weights for heterogeneous AGVs. Only the two most common types of AGVs were considered, namely forklift AGVs and load transfer AGVs.

It is noteworthy that in the aforementioned works on path planning with energy consumption, both in conjunction with task scheduling and considered independently, the authors generally disregard the issue of potential deadlock situations. In [53], the authors discuss the implementation of an agent responsible for collision avoidance, as well as the prevention of congestion and deadlocks. The proposed agent is founded on the principle of deep deterministic policy gradient. However, the specifics of the proposed approach remain undisclosed.

2.4. Summary of the Literature Review and Identification of Research Gap

A review of the relevant literature indicates that among the extant works on the use of energy consumption as a criterion for optimizing transport tasks performed by AGV fleets, only a few studies refer to the issue of deadlock. The prevailing assumption among works is the non-existence of deadlocks in the system. Consequently, it can be deduced that the transport system structures under consideration are engineered to be deadlock-free. However, two works explicitly refer to the issue of deadlocks. In [41], unidirectional loop networks were employed to form a deadlock-free structure, while in [44], the authors simplified the structure of the transport path network model used by replacing a bi-directional path with a single unit capacity into two unidirectional paths across the routing topology in order to avoid the issue of deadlocks. In the context of industrial practice, however, the presence of bidirectional pathways often precludes the replacement of these pathways with two unidirectional pathways. Moreover, the existence of multiple path intersections may result in resource waiting cycles and, consequently, lead to deadlocks. In such cases, it is not possible to determine collision-free and deadlock-free paths for all AGVs performing concurrent tasks. Consequently, the completion of transport tasks according to the established schedule is no longer feasible.

Therefore, it is necessary to consider the possibility of deadlocks in the system and apply an appropriate method to eliminate them. To the authors’ knowledge, existing scientific literature has not sufficiently addressed the impact of deadlock handling methods on energy consumption, transportation task timing, and AGV utilization in production systems. This problem poses a challenge, i.e., a research gap, which is why this study focuses on this issue. This paper addresses the original research problem of studying the impact of deadlock handling methods on the multi-criteria optimization of transport system control with multiple AGVs. Two methods are used as examples: the Chain of Reservation and the Structural Online Control Policy. These methods are briefly described in Section 3 and in more detail in [57,58]. The criteria used are the energy consumption of all AGVs and the time needed to complete all tasks (makespan). All energy consumption data were obtained from tests conducted on a real AGV. Additionally, two methods were used to generate paths: Shortest Path (SP) and Fastest Path (FP). Both are based on the Breadth-First Search (BFS) algorithm and are described in Section 3. All four methods were implemented and used to simulate the control of a multi-AGV system in a square topology environment. That allowed for the analysis of the research results and the formulation of final conclusions.

3. Research Problem and Applied Methods Statement

3.1. AGV Operating Environment Described as a Square Topology

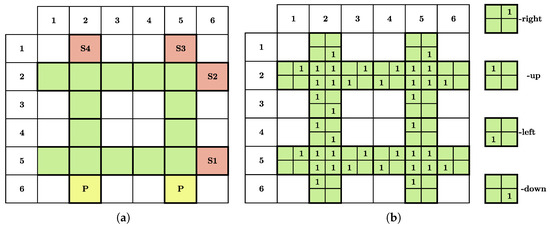

In the presented approach, the AGV operating environment has been discretized by dividing it into squares. This layout format is useful for modeling automated warehouse systems and container terminals. Additionally, it can represent a typical industrial layout with a specified level of discretization. Figure 1a shows an example of an environment defined in this way, with dimensions of 6 × 6. Colored squares mark the area in which the mobile robot can move. Yellow squares represent parking spaces, and red ones indicate stations, i.e., places where the mobile robot loads and unloads items. The robot can move from square to square and can stop within a square, turn around, and change its direction of travel without violating the boundaries of adjacent squares. The path for the mobile robot is defined as a sequence of squares.

Figure 1.

A transportation environment described as a square topology: (a) An example of mobile robot paths in an environment with six rows and six columns. (b) A precise description of possible movements from each square.

Using a square topology layout, there are four possible movement directions from each square: right, up, left, and down. To fully define the layout, it is necessary to specify all directions in which the robot can exit each square. In Figure 1b, each square is divided into four smaller squares. A value of 1 indicates the possibility of movement in the specified direction, according to the legend on the right side of the figure. In this way, the movement possibilities of the mobile robot can be precisely defined within its environment. This approach allows for the definition of both unidirectional and bidirectional paths. For example, in Figure 1b, the squares (4, 5) and (3, 5) form a unidirectional path (up) and squares (5, 3) and (5, 4) form a bidirectional path (left, right). The practical recording of this data is realized using four mask tables named R, U, L, and D. These correspond to movements to the right, up, left, and down, respectively. If, for example, in the R mask table a given cell has a value of 1, it indicates the possibility for the mobile robot to move from this square to the right, to the neighboring square. The method described above for defining the transport environment for mobile robots as a square topology will be used in the Section 4 to present a test case for the simulation experiment.

3.2. Deadlock Handling Methods

This article compares the effects of two COR and SOCP methods for handling deadlocks. The core concepts of these methods are discussed below. The COR method introduces the concept of a safe place, which is a parking space assigned to a specific AGV. No other vehicle can enter this parking space. An AGV’s driving path is a sequence of squares that begins and ends at its assigned parking space, i.e., its safe place. Before an AGV begins driving along its designated path, a reservation chain is created for each square along the path. Reservation information for individual AGVs is stored in queues assigned to squares. The contents of the queue depend on the number of AGVs passing through a given square and multiples of these trips. The reservation queue is handled according to the first-in, first-out (FIFO) rule. An AGV can proceed to the next square if it has the first reservation for that location. After an AGV leaves a square, the reservation at the front of the queue is removed. A full description of the COR method, along with a proof of its correctness, can be found in [57].

The Structural Online Control Policy (SOCP) categorizes squares along designated paths as one of two types of places. The first type, deadlock-free places, includes parking lots, stations, and squares that form unidirectional paths. The second type, deadlock-risk places, includes squares on bidirectional paths or crossings. The SOCP method divides paths into consecutive logical segments composed of deadlock-free and deadlock-risk places. The method introduces two rules of conduct. The first rule states that a transport task can only begin if a single place is reserved within all logical deadlock-free segments accessed by an AGV. This reservation is canceled when an AGV leaves the segment of the path. The second rule specifies the condition necessary to allow an AGV to perform an elementary transport operation into a deadlock-risk place. All residual places in the deadlock-risk segment must have available capacity. This method is suitable for both central and distributed control system architectures. A full description of the SOCP method, along with a proof of its correctness, is presented in papers [58,59].

3.3. The Path Planning Algorithms

In the presented study, two algorithms were used to generate the routes of mobile robots. The SP algorithm determines the shortest path (in terms of the number of steps) from the starting point S (start_r, start_c) to the target point G (goal_r, goal_c), r and c refer to row and column, respectively. It is based on the Breadth-First Search (BFS) algorithm and uses two work-lists:

- Current—Contains all cells (squares) analyzed in the current iteration;

- Next—Contains cells selected during the current iteration to be analyzed in the next one.

The movement of the mobile robot is possible only in four directions, defined by the mask tables: R, U, L, and D. A value of 1 means that the cell can be exited in the given direction. If movement is allowed and the target cell has not been visited yet, the letter: U, D, L or R is written into the Paths table at the current cell to indicate the direction of movement. The target cell is then added to the Next list. The algorithm terminates immediately upon reaching the coordinates of the target point G. The letters stored in the Paths table allow the route to be easily reconstructed from point G to point S by retracing the stored directions. The pseudo-code of the SP algorithm is shown below (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1 SP (Paths, R, U, L, D, start_r, start_c, goal_r, goal_c). |

|

The FP algorithm, like the SP, operates on the same input data and is also based on the Breadth-First Search algorithm. This algorithm is used to find the fastest path from the starting point, S, to the destination point, G, while taking into account the penalties for turning. This is significant because the number of turns required on the designated path significantly impacts travel time. The more turns, the longer the travel time. The key difference in its operation is the use of an additional Wait list. Similar to the SP algorithm, for each cell in the Current list, the possible directions of movement to neighboring cells are checked based on the data in mask tables: U, D, L and R. If movement is possible and the target cell has not yet been visited, then:

- If the direction of movement is the same as the previous one, the new cell is added to the Next list (i.e., it will be processed in the next iteration without delay);

- If the direction differs (i.e., a turn was made), the cell is added to the Wait list, which will be processed one iteration later, corresponding to a time penalty for changing direction.

The process ends when the destination point G is reached. The letters stored in the Paths table allow the route to be reconstructed for the mobile robot. The pseudo-code of the FP algorithm is presented below. The proposed FP algorithm do not aspire to compute precise, optimal travel times; instead, they prioritize event-based progression between successive locations (squares). Accurate travel time estimation is challenging due to the kinematic constraints of mobile robot movement and, in real-world systems, additional factors such as dynamics and environmental interactions. Therefore, each transition to a new square that involves a directional change (turn) is placed in a waiting queue and processed in the following iteration, as indicated in line 23 of Algorithm 2. This approach favors routes with fewer turns without requiring explicit time calculations and significantly improves computational efficiency.

| Algorithm 2 FP (Paths, R, U, L, D, start_r, start_c, goal_r, goal_c). |

|

3.4. Research Problem

The main objective of this research is to compare methods of dealing with deadlocks in terms of transportation system energy efficiency, makespan and AGV utilization under comparable conditions. The results of this analysis can be used to search for an optimal solution to the overall scheduling problem, in which the chosen method of deadlock handling would serve as a constraint.

As mentioned in previous chapters, the effective use of AGV-based transportation systems is influenced by many factors. Therefore, a multi-criteria approach should be used to evaluate them. The most commonly used evaluation criteria are the time taken to complete transportation tasks (makespan); energy consumption, which affects the operational cost of completing these tasks; and utilization rate of AGVs. Of the five essential tasks related to AGV systems presented in the article [21], this paper focuses on the tasks of path planning and motion planning. The importance of these two areas is particularly significant when the transport path network is not “by design” collision and deadlock free. In this case, it is necessary to apply appropriate methods that provide efficient path planning and collision and deadlock free control of the AGV system. Considering these factors, the article presents research on the impact of AGV deadlock handling and path planning methods on makespan, AGV energy consumption and AGV utilization.

4. AGV Functional Parameters

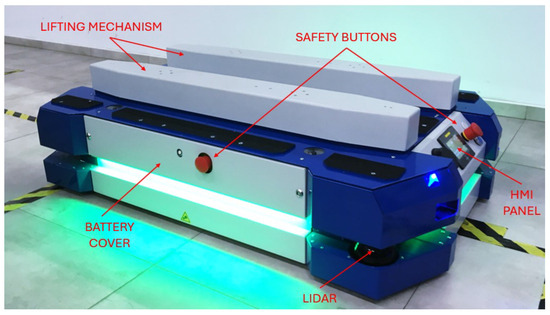

To build a simulation model for studying the energy consumption of AGVs, it is necessary to determine their functional parameters, particularly their energy consumption in different operating states. These parameters were determined based on measurements taken from a real mobile robot, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The tested mobile robot.

The dimensions and basic information of the mobile robot are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mobile robot parameters.

Kinematic parameters are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Kinematic parameters of mobile robot.

A very important aspect in the design of a simulation model for intralogistics systems based on AGVs is the performance of partial logistics tasks. Therefore, the purpose of the research conducted during the preparation stage was to determine the energy characteristics of a mobile robot. The scope of the study was to analyze the electricity consumption of the robot over time for typical intralogistics tasks under different task parameters. The transportation process was divided into smaller tasks, with the following cases distinguished and studied:

- Idle waiting;

- Accelerating and decelerating without a load (25 kg pallet) and with a load (600 kg pallet);

- Driving straight ahead without a load (25 kg pallet) and with a load (600 kg pallet);

- Turning without a load (25 kg pallet) and with a load (600 kg pallet).

To obtain accurate measurement results, ten passes were made during the test for a given mass-partial task configuration in order to calculate an average value. Temperature variations were not considered in the measurement results. Similarly to the real robot, energy recovery during braking was not implemented. Although each run was performed under identical conditions, it should be noted that the control system operates within a control loop with a Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controller, which introduces some variability in the runs. The average results of the measurements are presented in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Energy consumption by the mobile robot.

The data obtained are essential in the planning and design process of internal logistics, which fundamentally relies on AGVs. Understanding the amount of energy required and the possibility of its storage in batteries is a crucial aspect of estimating the required number of robots. It also determines path planning, which directly impacts the efficiency of the entire intralogistics system. In this context, the choice and development of battery technologies play a particularly important role. Recent advancements in battery technology, such as solid-state and aluminum-ion batteries, hold significant promise for the future of energy storage solutions in automated guided vehicle (AGV) systems. Solid-state batteries are expected to offer higher energy density, improved safety, and faster charging capabilities compared to traditional lithium-ion batteries. Aluminum-ion batteries, on the other hand, have the potential to provide greater capacity at lower cost and with an improved cycle life. The integration of these emerging technologies could substantially enhance the performance, efficiency, and sustainability of multi-AGV systems by enabling longer operating times, reducing charging durations, and minimizing maintenance requirements. Although current systems primarily rely on Li-ion batteries, ongoing advancements and the gradual commercialization of these new chemistries suggest that they may have a transformative impact on energy management and operational reliability in intralogistics and production environments in the coming years.

5. Simulation Experiment

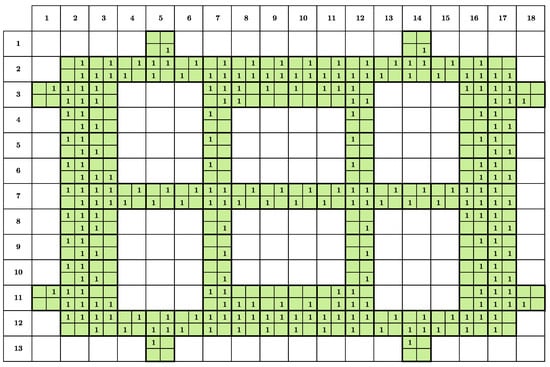

Figure 3 presents a discretized test layout with 13 rows and 18 columns. Inside each square, there can be up to four instances of the digit “1.” According to the legend below the figure, the value “1” indicates that AGVs can move in the corresponding direction. These data are stored in the R, U, L, and D mask tables. Squares with a green background represent transport routes accessible to AGVs. The presented layout serves as the foundation for building a simulation model of a production system that utilizes a transportation system with multiple AGVs.

Figure 3.

Definition of test layout paths in a square topology for a simulation model.

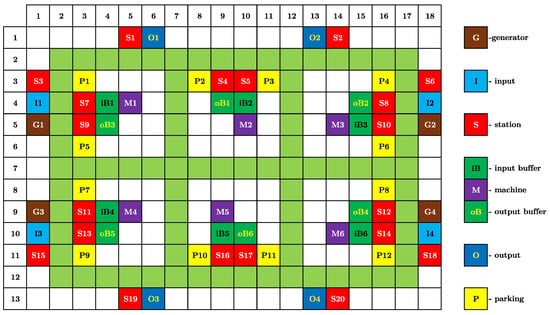

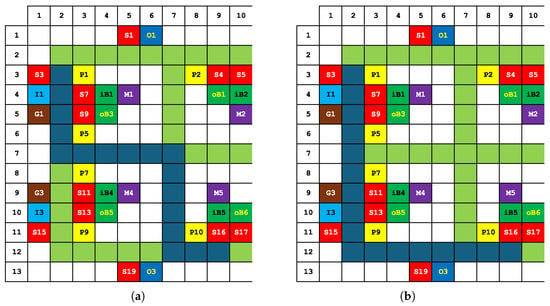

To investigate deadlock handling methods and the impact of the path generation method on energy consumption, a layout of a virtual production system was proposed. It was designed based on the test layout paths shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the arrangement of the system objects, where each square has a side length of two meters and the objects are numbered consecutively.

Figure 4.

The layout of a simulated production system.

The system contains workpiece generators (“G”), from which items are sent to input buffers (“I”). Stations (“S”) are locations where mobile robots stop to load or unload a workpiece. The production system includes six machines (“M”), each equipped with input buffer (“iB”) and output buffer (“oB”). After the production process is completed, the workpieces are transported to the appropriate output (“O”). Parking spaces for mobile robots are marked as (“P”). Each parking space is equipped with a battery charging station.

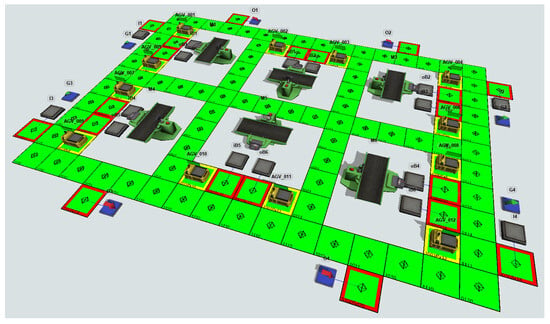

Based on the layout described above, a simulation model was built in FlexSim, as shown in Figure 5. Squares corresponding to the stations are marked with red frames, and parking places are marked with yellow frames. In this model, up to 12 AGVs can be used to perform transportation tasks. The AGV parameters were determined based on the characteristics and test results of a real mobile robot. The robot’s linear-motion kinematics follow a trapezoidal profile consisting of three stages: acceleration to the maximum attainable speed, travel at constant (crusing) speed, and deceleration at a constant rate. The simulation model omits robot docking as well as load lifting and lowering, since these activities are repetitive in every simulation scenario. Additionally, the loading and unloading time for each workpiece was set to 5 s. Angular acceleration and deceleration were omitted due to limitations of the simulation tool. Each robot is also equipped with a flag that visualizes the battery’s energy level.

Figure 5.

View of a 3D simulation model.

A different workpiece was generated in each of the four generators “G.” Each subsequent workpiece of a given type was generated at 1 s intervals, and the time each workpiece spent in the system was recorded in the “Age” parameter. A “Step” parameter was also assigned to each workpiece, indicating the next stage of the technological process to be completed.

To ensure uniform conditions for both the analyzed deadlock handling methods and the two path generation algorithms, it was assumed that transportation tasks were generated based on a queue of workpieces waiting for transport. The objects in this queue were ordered first by the “Step” parameter and then by “Age.” A workpiece with higher “Step” and “Age” values was prioritized. The nearest available AGV was assigned to carry out the transportation task for the first workpiece in the queue. The next free AGV was assigned to carry out the transportation task for the next workpiece, and so on. The number of generated workpieces, along with their routing, is presented in Table 4. The transportation task involves the robot traveling to the loading station (picking up the workpiece), traveling to the unloading station (delivering the workpiece), and returning to its parking place.

Table 4.

The batch size and routing.

To illustrate how the simulation procedure works, we briefly describe the processing of the first generated item (WP1). The remaining items follow the same logic, so for clarity we focus only on this initial example. In the simulation experiment, five items of each type were generated. Item WP1 is created first and, according to the routing defined in Table 4, it must be collected from buffer I1 and transported by an AGV through station S3 to station S16. The nearest available robot is assigned to execute this task. At the beginning of the simulation, this will be AGV1, located at parking space P1. Before the robot begins the task, a travel path is generated to station S3, then from S3 to S16, and finally from S16 back to its designated parking space. The resulting path depends on the selected path-generation algorithm (SP or FP). Figure 6a illustrates a fragment of the path from S1 to S16 (dark blue squares) generated using the SP algorithm, while Figure 6b shows the corresponding fragment generated using the FP algorithm. Although both fragments cover the same distance, they differ in the number of turns, which directly affects energy consumption and travel time.

Figure 6.

Fragment of the generated path for AGV1 from station S3 to S16: (a) By the SP algorithm. (b) By the FP algorithm.

During the simulation, a new travel path is generated for each AGV immediately before it begins a transport task. The generated route depends on the robot’s current position as well as the pickup and drop-off locations associated with the task. In the simulation experiments, one of the two path-generation algorithms (SP or FP) is selected first, and one of the two deadlock-prevention methods (COR or SOCP) is applied. For each such configuration, simulation experiments is performed with the number of AGVs ranging from 1 to 12.

Since the aim of this research is to evaluate the energy efficiency of the transportation system based on the methods used for deadlock handling and path generation, following processing times were assumed for individual machines (M2 and M5: 600 [s]; M1, M3, M4, and M6: 1000 [s]). This ensures that the transportation system is subjected to a higher load in an environment that is more prone to deadlock, allowing a more accurate assessment of its operational performance. To analyze energy efficiency during the simulation, the type of task performed by each AGV (e.g., acceleration without load, driving straight, etc.) was recorded at a frequency of 1 Hz ( [s]). Based on these data, the current drawn from the battery per second was calculated and subtracted from the initial battery capacity of 40 [Ah], according to Equation (1). The total energy consumed by the mobile robot was calculated according to Equation (2).

where

- —battery capacity level [Ah].

- —time step (sampling period) [s].

- —power consumption depending on the task (e.g., acceleration, motion) [W].

- —battery voltage [V].

- —cumulative energy used [Wh].

It should be noted that the type of electric motors used, as well as the charging strategies adopted, plays an important role in the energy efficiency and operational reliability of AGV systems. In our study, the mobile robot was equipped with BLDC motors due to their advantageous characteristics, including high efficiency, low maintenance requirements, and cost-effectiveness. These motors are well-suited for continuous operation in intralogistics environments, providing a good balance between performance and energy consumption. Alternatively, Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) are gaining increasing attention due to their higher efficiency and enhanced control capabilities, which can contribute to further reductions in energy consumption and longer operating times.

With respect to charging solutions, our model assumes the use of constant-voltage Direct Current (DC) chargers, which are commonly applied in industrial settings due to their simplicity and fast charging capabilities. The Battery Management System (BMS) ensures safety by preventing overcharging, thereby maintaining stable and reliable operation. This approach is consistent with best practices reported in recent literature, such as [60]. The simulation model assumes the presence of charging stations with a charging power [W] in each parking space. Such a solution is commonly used in practice. The charging process of lithium-ion batteries can be reasonably approximated as linear up to approximately 80% State of Charge (SoC). This is primarily due to the Constant Current (CC) phase, during which the battery voltage increases steadily under a fixed current, resulting in an almost linear accumulation of charge. Although the subsequent Constant Voltage (CV) phase introduces some nonlinearity as the current gradually decreases, for modeling and control purposes—especially when charging is limited to 80% SoC—a linear approximation provides sufficient accuracy and simplifies system analysis. This assumption is commonly adopted in engineering practice to strike a balance between model fidelity and computational efficiency. Each mobile robot begins the battery charging process when the energy level drops below and ends charging when it exceeds 80%. In the simulation, the increase in battery energy is modeled linearly, according to Equation (3), and the charging process is not interrupted.

where

- —battery capacity level [Ah].

- —time step (sampling period) [s].

- —charging power [W].

- —battery voltage [V].

In order to reduce the probability of all mobile robots running out of battery power at the same time during the simulation, a rule was introduced to set their initial battery energy levels, according to Equation (4). In this way, the initial energy levels in the batteries are uniformly distributed—from the maximum value (in one mobile robot) to a minimum value that is still above the charging threshold .

where

- —initial battery level for a given AGV [Ah].

- C—battery capacity [Ah].

- —initial charging level (percentage of capacity) [%].

- —total number of AGVs [-],

- —rank/index of the AGV, starting from 1 [-].

Simulations were performed until all processes were completed and, consequently, all transportation tasks were finished. During the simulations, two deadlock handling methods were applied—COR and SOCP—along with two path generation methods: SP and FP. The number of AGVs ranged from 1 to 12. The vehicles used in each simulation are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

The AGVs used in simulation experiment.

6. Analysis of Simulation Results

During the simulation experiments, the following indicators were recorded:

- Makespan—the total time required to perform all transportation tasks ;

- Total energy consumption of all AGVs, expressed as ;

- Average utilization of all AGVs, expressed as a percentage .

The results of 12 simulations—corresponding to the number of AGVs used in the transportation system—for the four variants of the methods applied are presented in Table 6 and Table 7. Table 6 presents the results for the COR deadlock handling method using the SP and FP path generation algorithms, while Table 7 presents the results for the SOCP deadlock handling method, also using the SP and FP algorithms.

Table 6.

Results for COR method with SP and FP algorithm.

Table 7.

Results for SOCP method with SP and FP algorithm.

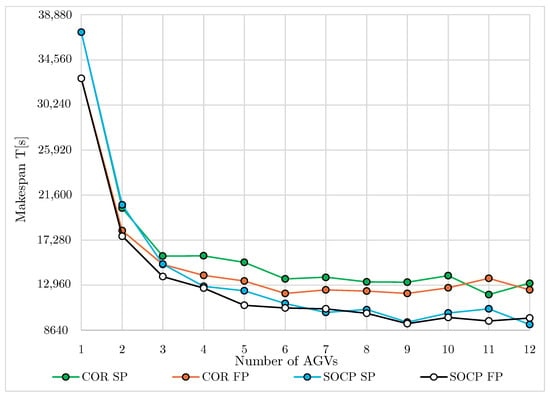

The simulation results are presented in three graphs. The first graph, shown in Figure 7, illustrates the total time required to complete transportation tasks T [s] for all four variants of the methods used as a function of the number of AGVs. The figure shows that in most cases the lowest makespan value is obtained using the SOCP method in combination with the FP algorithm. It can also be seen that increasing the number of AGVs does not always directly reduce the execution time, and this effect depends on the methods used.

Figure 7.

Makespan T [s]—total time of tasks completion.

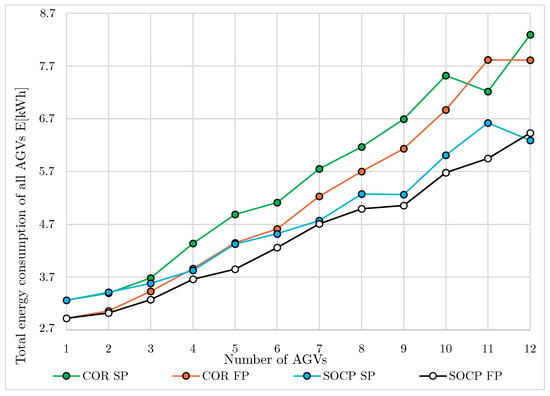

Figure 8 shows the relationship between the total energy consumption [kWh] and the number of AGVs for all four variants of the methods used. In general, increasing the number of AGVs resulted in higher total energy consumption [kWh]. Again, the SOCP method combined with the FP algorithm produced the best results.

Figure 8.

Total energy consumption of all AGVs E [kWh].

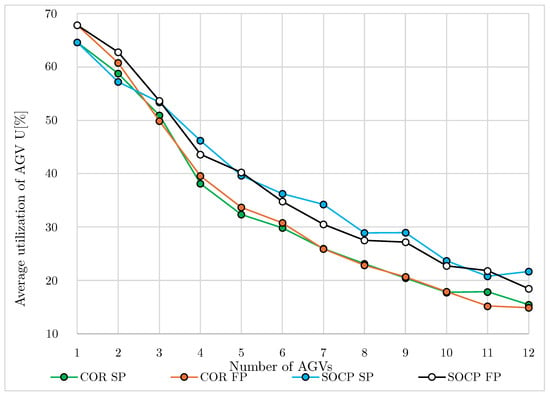

The graphs in Figure 9 summarize the average AGV utilization U[%] as a function of the number of AGVs. As can be seen, the level of AGV utilization decreases as the number of AGVs increases. This is due to the fact that the transportation tasks are distributed among a larger number of vehicles. This leads to a reduction in the economic efficiency of the transportation system, which prevents a quick return on investment. A consequence of the increased number of vehicles is also an increased number of their interactions, which can lead to longer waiting times for the continuation of ongoing transportation tasks.

Figure 9.

Average utilization of AGVs.

The values recorded during the simulation studies are important indicators of the efficiency of transportation systems using AGVs. Let’s therefore conduct a multi-criteria analysis of the simulation results obtained. We will consider the following criteria:

- Makespan—The total time required to perform all transportation tasks (T [s]), subject to minimization;

- Total energy consumption of all AGVs (E [kWh]), subject to minimization;

- Average utilization of all AGVs, expressed as a percentage (U [%]), subject to maximization.

The second and third metrics, E [kWh] and U [%], are non-conflicting. An analysis of the simulation results, as presented in Table 6 and Table 7, indicates a consistency between the total energy consumption criterion and the average AGV utilization criterion. This hypothesis is corroborated by the correlation coefficient results for the values of these criteria depending on the changing number of AGVs. For the pairs COR SP, COR FP, SOCP SP, and SOCP FP, the respective values are −0.93, −0.92, −0.96, and −0.95. The negative values are a consequence of the fact that the energy consumption criterion is minimized while the AGV utilization criterion is maximized. Moreover, all variants considered have optimal values for the same number of AGVs. This is evident in the simulation results presented in Table 6 and Table 7. For the COR SP variant, E = 3260 kWh and U = 64.63%; for the COR FP variant, E = 2918 kWh and U = 67.82%; for the SOCP SP variant, E = 3260 kWh and U = 64.63%; and for the SOCP FP variant, E = 2918 kWh and U = 67.82%. The multicriteria optimization problem was reduced to a two-criteria task with two conflicting objectives: T [s], which is subject to minimization, and E [kWh], which is also subject to minimization.

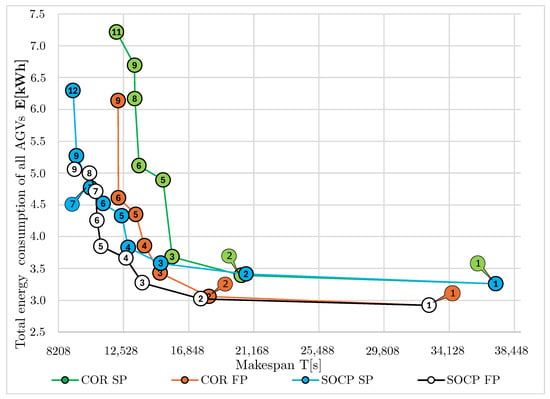

Multi-criteria analysis is predicated on the principle of Pareto optimality, which states that a Pareto optimal solution is one in which none of the objective functions can be improved without degrading the value of at least one of the others. The objective of Table 8 is to facilitate the multicriteria analysis of the results derived from the simulation tests. It organizes the results contained in Table 6 and Table 7 by arranging the values of the considered criteria E [kWh] and T [s] so that straightforward comparisons can be made, and by adding columns and containing, for a given number of AGVs, the differences between the maximum (brown) and minimum (blue) values.

Table 8.

Results of multicriteria analysis for different AGV configurations.

The values contained in the and columns demonstrate the extent to which the variant of the methods used impacts the adopted evaluation criteria. In Table 8, the dominated solutions that are not considered in the multicriteria analysis are marked with a red “x”. The data contained in Table 8 were used to prepare Figure 10, which shows the Pareto fronts for all four variants of the methods used. The presence of circles on the graphs serves as a visual representation of the number of AGVs. As illustrated in Figure 10, the SOCP FP variant typically demonstrates a substantial advantage in most cases. From a practical standpoint, it is imperative to ascertain the number of AGVs at which the system functions most efficiently. Consequently, the objective is to identify a resolution that constitutes a compromise between the identified Pareto solutions.

Figure 10.

Pareto fronts.

The determination of a compromise solution was achieved through the implementation of the minimax decision rule, a fundamental principle derived from zero-sum game theory. As illustrated in Table 8, additional columns were appended to the existing framework, aligning with the specified variant categories. These columns are designated as “Max relative deviation ”. The values contained in these columns were determined as the maximum of the relative deviations from the minimum values.

where i denotes the number of AGVs and j denotes the variant under consideration. The values and represent the global minimum values for criteria and , respectively. These values, marked in Table 8 by underlining, are and , respectively.

An analysis of the final four columns of Table 8 reveals that the values in the SOCP FP column are lower than those observed in the other variants, irrespective of the number of AGVs in the system. This finding substantiates the hypothesis that this variant is superior, and that the minimum value of the maximum relative deviation minimax = 31.91 (highlighted in bold), represents the most advantageous compromise, corresponding to the deployment of five autonomous guided vehicles (AGVs) within the system. The table also shows that for the COR SP and COR FP variants, the compromise solution is also obtained for five AGVs, while for SOCP SP it applies to four AGVs.

Comparing, for the tested example, the energy consumption for the variant with five AGVs, the difference between the best and the worst result is ΔE = 1.04 [kWh]. Assuming the CO2 emission factor Fe at the average level for Poland in 2024 Fe = 597 [gCO2/kWh] it can be observed that selecting the appropriate method of controlling the AGV fleet allows for a reduction of CO2 emissions, in this particular case, by 620.88 [gCO2].

7. Conclusions

The growing interest in AGV systems has inspired the search for solutions that enhance their efficiency. This is particularly true for issues such as reducing operating costs related to energy consumption for transportation tasks, increasing productivity by shortening task completion time, and improving return on investment by optimizing AGV utilization. Reducing energy consumption can significantly reduce long-term operating costs and offer environmental benefits. Meanwhile, advanced algorithms that solve critical decision-making and optimization problems for AGV system control play a fundamental role in boosting productivity. One such issue is deadlock handling.

This article uses a multi-criteria approach to analyze how methods for deadlock handling impact the efficiency of a production system. A simulation model of a production system using an AGV was developed in FlexSim that implemented two deadlock handling methods: COR and SOCP. Two route-generation options were also used for each method: SP (shortest) and FP (fastest). Technical data on AGVs necessary for simulation experiments, particularly that related to electricity usage, was obtained from tests conducted on a real object. The established principles of battery charging were also discussed. Then, simulations were performed with varying numbers of AGVs, from one to twelve, for all method variants. The results were summarized in tables and presented in graphs. They demonstrate that the total energy consumption criterion is consistent with the average utilization of AGVs. This allowed the optimization problem to be reduced to a two-criteria problem, focusing on makespan and total energy consumption of all AGVs. Pareto fronts were determined for all analyzed variants. As presented in Table 8 and illustrated in Figure 10, the differences between the best and worst variants are significant. These results suggest that the method used to handle deadlocks has a significant impact on the quality of solutions obtained in production systems in which the transport subsystem is not deadlock-free by design. Furthermore, the Pareto fronts obtained from simulation studies can be used to determine the optimal number of AGVs in a real transport system by balancing vehicle energy consumption with the time required to complete all tasks. It should be noted that the Pareto solutions were obtained not by solving a general scheduling task but by using queuing mechanisms for transport elements based on the “Step” and “Age” parameters built into FlexSim.

It should be emphasized that the research conducted in this study was based on the parameters of a real mobile robot, which allows for drawing conclusions that reflect practical conditions. Repeating these experiments using data from another AGV with a different battery type may—and most likely will—yield different results, which is to be expected. Similarly, variations in the path structure and other operational factors may influence the outcomes. Nevertheless, the method proposed in this article for analyzing the efficiency of controlling a fleet of mobile robots enables the selection of the most suitable solution for a given implementation of a mobile robot-based transport system.

Based on the conducted research, it can be concluded that implementing an appropriate deadlock handling method to control a transport system consisting of multiple mobile robots can significantly reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. If a case study were conducted on the use of mobile robots—for example, replacing traditional forklifts in a warehouse setting—it would be possible to quantify the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Such a study would require data on the emission levels generated by the conventional system and information about the local emission factor. The pursuit of sustainable development, while taking into account environmental impact, encourages further research into the effective use of mobile robots in intralogistics.

8. Further Works

Future research should focus on improving the effectiveness of deadlock-handling methods, as these directly influence both the reliability and efficiency of multi-AGV systems. Equally important is the development of path-generation algorithms that take into account the movements of other AGVs, allowing for more adaptive and collision-free navigation in dynamic environments. In addition, interference from other objects encountered during mobile-robot operations must be considered, since real production settings rarely provide fully predictable conditions. Such interference includes not only static or dynamic obstacles but also human workers who may cross the paths used by mobile robots, introducing an additional layer of uncertainty and requiring advanced safety and detection mechanisms. Moreover, the application of machine learning techniques to predict transport tasks offers promising opportunities, as transport demand is typically generated by the completion of preceding production processes. Anticipating such events enables earlier responses and proactive redirection of mobile robots, which in turn enhances scheduling efficiency, minimizes idle time, and improves overall resource allocation within intralogistics systems. Finally, future research should investigate how different battery technologies influence AGV energy efficiency, considering factors such as battery mass, capacity, and charging characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, W.M.; validation, W.M., J.Z. and W.K.; formal analysis, R.C.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, W.K.; data curation, W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, W.M.; supervision, R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMO | Animal Migration Optimization |

| AMR | Autonomous Mobile Robot |

| APF | Artificial Potential Field |

| BEO | Building Energy Optimization |

| BFS | Breadth-First Search |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| BLDC | Brushless Direct Current |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| CC | Constant Current |

| COR | Chain Of Reservations |

| CV | Constant Voltage |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DDQN | Double-Deep Q-Network |

| EAPP | Energy-efficient AGV Path Planning |

| FP | Fastest Path |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GVNS | General Variable Neighborhood Search |

| GWO | Grey Wolf Optimization |

| HDQN | Hybrid Deep-Q Network |

| HEMS | Home Energy Management Systems |

| HGWPSO | Hybrid Grey Wolf-Particle Swarm Optimization |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| MAPF | Multi-Agent Path Finding |

| MHA* | Multi-Heuristic A* |

| MR | Mobile Robot |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| PMSM | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| SOCP | Structural On-line Control Policy |

| SP | Shortest Path |

| TEC | Total Energy Consumption |

| VNS | Variable Neighborhood Search |

References

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. International Energy Outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/ieo/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2024—Analysis—IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Corlu, C.G.; Torre, R.D.L.; Serrano-Hernandez, A.; Juan, A.A.; Faulin, J. Optimizing energy consumption in transportation: Literature review, insights, and research opportunities. Energies 2020, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Hu, W.; Dong, J.; Sun, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z. A systematic literature review of green and sustainable logistics: Bibliometric analysis, research trend and knowledge taxonomy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtsis, D.; Tsolakis, N.; Vlachos, D.; Iakovou, E. Sustainable supply chain management in the digitalisation era: The impact of Automated Guided Vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3970–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.A.; Olteanu, S.C.; Ifrim, A.M.; Petcu, C.; Silvestru, C.I.; Ilie, D.M. The Influence of Energy Consumption and the Environmental Impact of Electronic Components on the Structures of Mobile Robots Used in Logistics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamasz, K.; Stęchły, J.; Komorowska, A.; Kaszyński, P. The Impact of Fleet Electrification on Carbon Emissions: A Case Study from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]