Abstract

Integrated additional cooling channels offer precise thermal management for solid-oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), mitigating temperature gradients. This research studies the thermal–hydraulic performance of cooling channels integrated between SOFC interconnectors, including a Diamond-type triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS), a conventional topology-optimized structure, and a topology-optimized lattice-filled structure. A conjugate heat transfer analysis is employed to investigate the influences of flow rate within the range of Reynolds numbers from 300 to 5000, and the effects of coolant type, including air and liquid metals, as well as the impacts of structural material. The results demonstrate that the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure, generating high turbulence mixing, achieves superior temperature uniformity, especially at high flow rates, despite having higher thermal resistance and pressure loss than the conventional topology-optimized design. The coolant types show the largest influence on thermal–hydraulic performance, and the use of liquid gallium in the conventional optimized design obtains the best temperature uniformity, yielding differences between the maximum and minimum temperatures of less than 5 K. Moreover, the higher-thermal-conductivity material improves temperature uniformity, even at low flow rates. Overall, the optimized-baffle designs in the conventional topology-optimized model, utilizing high-conductivity coolant and structural materials, could be the most suitable for thermal management of the SOFC.

1. Introduction

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) are an advanced technology for the future of sustainable energy, capable of directly converting chemical reactions into electricity with high efficiencies exceeding 70% [1]. Their high operating temperatures, ranging from 873 K to 1273 K, enable the favorable reaction kinetics, the use of non-precious metal catalysts, and the recovery of valuable high-grade waste heat [2]. However, the heat generated from exothermic electrochemical reactions, Joule heating, and resistive losses causes substantial temperature within the cell. These non-uniform thermal gradients induce thermomechanical stresses, leading to performance degradation through mechanisms such as electrode sintering and interconnect delamination [1,2,3]. Aguiar et al. [4] have suggested that a maximum local temperature gradient of 10 K/cm is critical to mitigate such structural damage, emphasizing that precise temperature control is not merely beneficial but essential for the commercial applicability and durability of SOFC systems.

Effective thermal management is therefore crucial for the SOFCs to minimize temperature gradients in the positive electrode–electrolyte–negative electrode (PEN) and interconnector structures. Enhancing thermal conduction in the PEN materials and improving convective heat transfer in gas channels are the most effective strategies to obtain high temperature uniformity. Different thermal management approaches have been investigated, including optimized air/fuel channels to increase surface area and uniform gas distribution [5,6]; flow arrangements, where adopting a co-flow arrangement generally yields a smaller temperature gradient compared to other configurations [7,8,9]; heat pipes [10,11], which can significantly lower gradients yet face challenges of heavy stainless-steel envelopes and long startup times; and fuel composition control [12], since endothermic reforming creates severe gradients, while adjusted air-to-fuel ratios help mitigate them.

Conventional thermal management also relies heavily on excess air circulation through cathode channels [13,14,15,16]. Experimental and numerical studies have confirmed that regulating air flow rate significantly influences thermal gradients. Wang et al. [17] demonstrated that increasing the airflow from 1.5 m/s to 7.5 m/s reduced the peak temperature gradient by around 17%. A similar increase in fuel velocity also enhances convective heat transfer and improves thermal uniformity. While increasing the air flow rate can moderate temperatures, the low volumetric heat capacity of air consumes significant pumping power for compression, accounting for up to 10% of the net output [18]. Furthermore, excessive air cooling can lower the average stack temperature, weakening electrochemical performance and reducing power density. These inherent limitations have encouraged the investigation of advanced cooling strategies [2,3].

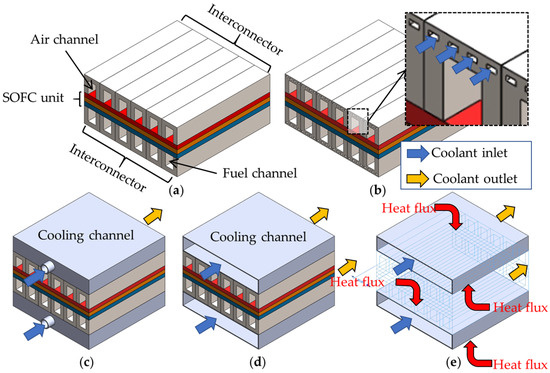

Another innovation in thermal management for SOFCs is the use of high-performance coolants in an additional cooling channel integrated within the SOFC stack, as shown in Figure 1b–d. Promsen et al. [16] proposed a saturated water-cooled SOFC stage. They found that the water-based cooling method reduced temperature differences in planar stacks from 185 K to 26 K. This strategy also reduced the parasitic losses from the air blower, increasing the overall system efficiency. Li et al. [14] proposed a supercritical fuel-cooled SOFC scheme. They observed that this design significantly reduced the temperature gradient from 22.7 K/cm in a conventional air-cooled SOFC to 8.35 K/cm, resulting in a substantial reduction in air usage and thereby lowering parasitic power consumption, improving overall efficiency. Fan et al. [15] revealed that an additional liquid tin cooling channel achieved a highly uniform temperature of 15 K. Later, Hasbi et al. [19] demonstrated that liquid gallium flowing through additional cooling slots of SOFC interconnectors significantly improved temperature uniformity over air cooling, though its high flow rates caused a larger pumping power penalty. These methods decouple the cooling function from the oxidant supply, allowing for a drastic reduction in the excess air ratio and its associated parasitic losses.

Figure 1.

Different cooling strategies for SOFC stack: (a) excessive air; (b) coolant flowing through the interconnectors; (c,d) coolant passing through an additional cooling channel; and (e) concept of simplified boundary conditions in this study.

Despite these promising results, a critical gap remains in the design and optimization of the additional cooling structures for the SOFCs. Advanced architectures, such as triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) lattices, offer superior thermal performance and structural integrity in various thermal management systems [20]. However, their use in cooling channels often causes a high-pressure loss, which again demands excessive pumping power [21]. To address this trade-off, researchers have turned to optimization techniques [22,23]. One promising method combines density-based topology optimization with lattice infills [24]. This process first computes an optimal channel layout under defined constraints and objectives. The obtained intermediate densities are then filled with lattice structures. This hybrid approach has been shown to significantly reduce pressure loss while maintaining excellent thermal performance, offering a potential pathway to more efficient thermal management of the SOFCs.

Hence, this study proposes high-performance cooling channel designs integrated between SOFC interconnectors [14,15,16], focusing on thermal–hydraulic performance and temperature uniformity of three advanced cooling structures: (1) a Diamond-type TPMS network, known for its high surface-area-to-volume ratio and efficient flow mixing [25]; (2) conventional topology-optimized structures, designed through computational methods to achieve optimal heat transfer performance under given constraints [26,27]; and (3) a hybrid topology-optimized-filled lattice structure, which combines the tailored flow paths of topology optimization with the enhanced heat transfer of an infilled lattice [24].

This investigation employs a simplified but practical approach by modeling cell heat generation as a constant heat flux boundary condition, as demonstrated in Figure 1d, allowing a comparative evaluation of these complex geometries. This methodology, successfully applied in studies on proton-exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) [28,29], enables the isolation and detailed analysis of the thermal–hydraulic performance of the cooling structures. This study further examines three critical factors that govern thermal management performance in the SOFCs. The analysis evaluates the thermal–hydraulic performance and temperature uniformity of the proposed cooling structures within the Reynolds numbers of 300 to 5000 [19], compares different coolants (air, liquid tin [15], and liquid gallium [19]), and assesses the impacts of commonly used metallic materials [30], including ferritic stainless steel [15], high-thermal conductivity metal [31], and nickel–chromium superalloy [32]. Through this comprehensive analysis, this work aims to serve as a guideline for implementing advanced cooling channels between the SOFC stacks to improve efficiency and durability.

2. Methodology

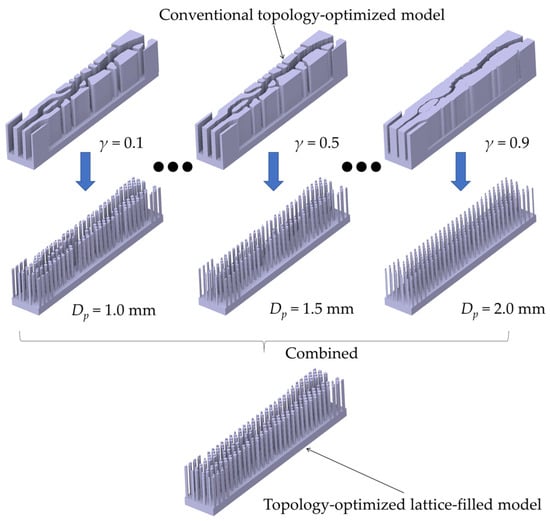

This study employs conjugate heat transfer (CHT) analysis to investigate the thermal–hydraulic performance, evaluating the impact of flow rate, coolant type, and structural material on heat transfer efficacy, pressure drop, and temperature uniformity. A comparative analysis covers three cooling architectures, including the Diamond-TPMS channel, a high-performance cooling structure generated via density-based topology optimization to maximize heat transfer, and the topology-optimized lattice-filled geometry, where the optimized density fields (γ) are interpreted into a manufacturable circular pin-fin array. This lattice structure is selected for its compatibility with traditional manufacturing and integration within narrow SOFC stack interconnects.

It should be noted that this study employs 2D topology optimization for computational efficiency, justified by the narrow channel gap. While a full 3D optimization generates complex geometries requiring advanced additive manufacturing, the 2D method produces extrudable designs, which are suitable for conventional processes [33,34,35,36]. This simplification is also validated by the comparable cooling performance achieved between the 2D-derived and full 3D models [37]. The topology optimization procedure is elucidated in the Appendix A, while subsequent sections detail the numerical models, boundary conditions, mesh sensitivity, and validation.

2.1. Numerical Models

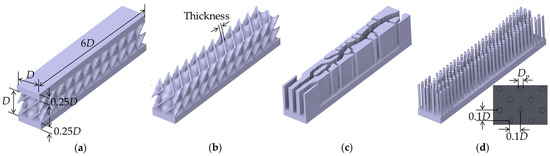

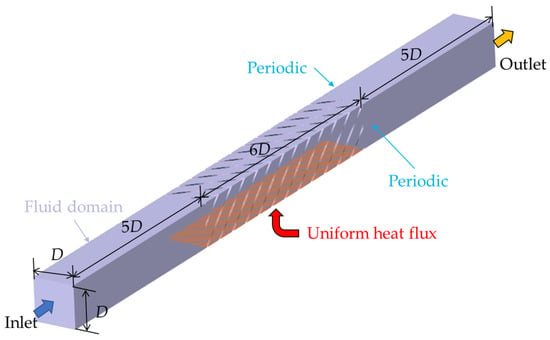

The numerical models investigated in this study are presented in Figure 2. Figure 2a shows the overall dimensions of the cooling structure, with a characteristic length (D) of 20 mm. The channel has a cross-section of 20 mm × 20 mm, attached by heated plates with a thickness of 5 mm, consistent with the previous study [16]. The length of the cooling structure (L) is 120 mm. Figure 2b shows the Diamond TPMS structure, which is generated from a mathematical equation [21]. This structure has a wall thickness of 1 mm and a unit cell size of 20 mm. The conventional topology-optimized design, shown in Figure 2c, is obtained by extracting the density field (γ) from the density-based topology optimization with an iso-contour threshold of 0.5. In Figure 2d, the optimized layout is interpreted as an array of circular pin-fins, where the pin diameter (Dp) varies consistently with the local density field (0.1 ≤ γ ≤ 0.9). The Dp = 1 mm corresponds to γ = 0.9, increasing consistently to Dp = 2 mm where γ = 0.1. A summary of all design parameters is provided in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Numerical models in this study: (a) Dimension of cooling structure; (b) Diamond-type TPMS structure; (c) Conventional topology-optimized design, and (d) Topology-optimized lattice-filled geometry.

Table 1.

Details of numerical models in this study.

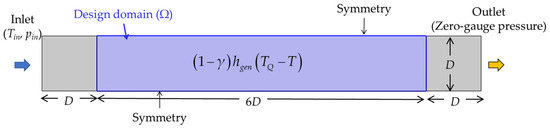

2.2. Computational Domain and Boundary Conditions

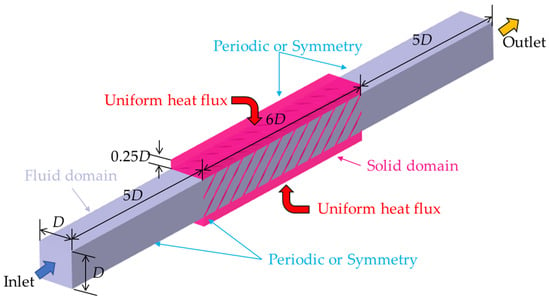

The conjugate heat transfer simulations are conducted using Ansys Fluent v. 2021R1, Ansys Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA. Figure 3 depicts the computational domain for the cooling channel configuration. Spanwise periodic boundary conditions are applied to the Diamond TPMS model, while the symmetry conditions are used for the topology-optimized and lattice-filled models to minimize computational cost. The bottom and top walls of the solid structure are treated by a uniform heat flux of 3200 W/m2, and this value was obtained based on an operating voltage of 0.75 V by Zhang et al. [38]. The interfaces between the solid and fluid domains are modeled using conjugate boundaries, and the rest surfaces are set as adiabatic.

Figure 3.

Computational domain and boundary conditions.

It is important to note that this study employs a uniform heat flux boundary condition to facilitate a direct cooling performance comparison of each case. In the SOFC, the current density and electrochemical reactions typically result in non-uniform heat generation within the PEN layer. While this simplification does not capture the uneven temperature distributions, it provides a consistent method for evaluating the cooling performance and temperature uniformity of each design. Future work will incorporate coupled electrochemical–thermal models to investigate the interaction between non-uniform stack generation and advanced cooling.

Three coolants, including compressible air, liquid tin, and liquid gallium, are studied. The inlet is defined with a uniform velocity profile and a constant temperature of 1073 K, while the outlet is set to a zero-gauge pressure [15,19]. The influence of the flow rate is investigated for the air-cooled channel at the Reynolds numbers of 300, 1000, and 5000 [19]. For the subsequent studies on coolant type and structural material, a Reynolds number of 300 is maintained. The solid structures are modeled with the properties of ferritic stainless steel, a high-thermal-conductivity metal, and a nickel–chromium superalloy. The corresponding thermophysical properties are detailed in Table 2, and all studied cases are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Material properties of the coolant and solid structure.

Table 3.

Studied cases in this research.

2.3. Parameter Definition

The Reynolds number (Re) is calculated based on the velocity (Vin) at the inlet channel, as follows:

where ρ and μ are the density and dynamic viscosity of the coolant, defined at the inlet.

Generally, the hydraulic diameter (Dh), applied to highly complex structures, such as porous media or two-fluid heat exchangers, is calculated as 4ψ/Sv, where ψ is the porosity and Sv is the specific surface area [21]. However, for this study, which focuses on channel-based heat sinks, the Dh is defined using the conventional channel-flow definition [19,25]:

where Ain indicates the cross-sectional area at the inlet of the cooling channel, and Lp is the wetted perimeter. Using this definition, all designs are created with a consistent Dh = 20 mm. Meanwhile, the Dh values calculated using the former porous media definition are provided in the Appendix A.

The Nusselt number (Nu), which is generally used to characterize the convective heat transfer in the channel, is calculated as follows:

where k is the thermal conductivity of the cooling material. h is the local heat transfer coefficient, which is defined by

where q is the wall heat flux at the observed area. Tw and Tb are the endwall and bulk temperatures. Tb is evaluated by linearly interpolating between inlet (Tin) and outlet (Tout) temperatures.

The heat exchange capability for all cases is evaluated based on the total thermal resistance (Rtot), defined as follows [33]:

where Theat is the area-averaged temperature on the heated wall. Q is the total heat input.

For the hydraulic performance, the friction factor (f) and pumping power (Pe) of the flow along the channel are expressed as follows:

where ∆p is the average pressure difference between the inlet and outlet of the cooling structure.

The performance evaluation criterion (PEC) is calculated to quantify the trade-off between heat transfer enhancement and the associated pressure loss:

where Nuavg indicates the area-averaged Nusselt number. The baseline Nusselt number (Nu0) and friction factor (f0) are obtained from the Dittus-Boelter equation and the Blasius correlation, respectively, as follows:

where the Prandtl number (Pr) for air is assigned a value of 0.7. It should be noted that Equations (9) and (10) are valid for the turbulent regimes (Re > 4000).

The temperature uniformity index (TUI) is calculated to quantify the temperature uniformity on the heated surface. The TUI is defined by the following equation:

where Ti is the local temperature, Ai is the local area, and Theat is the area-averaged temperature of the heated wall.

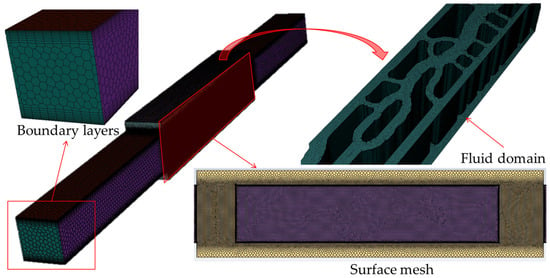

2.4. Mesh Independence Check and Numerical Scheme

The computational domain is discretized using poly-hexcore and prism meshes generated in Fluent Meshing. Figure 4 shows the mesh system for the conventional topology-optimized design. The “Body of Influence” is activated over the cooling structure to control high-quality surface mesh. Moreover, to capture complex structures, especially the Diamond TPMS and lattice-filled models, the value of the curvature normal angle and cell per gap is set at 9 degrees and 1. The boundary layers are generated using the smooth-transition offset method with the transition ratio of 0.272. Overall, the solid and fluid domains primarily consist of hexagonal elements, while prism layers are densely generated near all no-slip walls to ensure the y+ value below 1.0.

Figure 4.

Overview of the mesh system in the conventional topology-optimized model.

The realizable k-ε turbulence model is selected for this study based on its demonstrated accuracy in predicting the thermal–hydraulic performance of complex TPMS channel geometries in previous work [25], where it showed excellent agreement with experimental transient liquid crystal thermography (TLC) data at higher Reynolds numbers (Re = 10,000–30,000). While the Reynolds number range in the present study is ranging from Re = 300 to 5000, encompassing both laminar and transitional regimes, the use of turbulence models throughout the entire range is a common approach for comparative analysis of complex geometries, as seen in various air- and liquid-cooled heat sink studies [34,35,36,37]. Since this study also focuses on a relative comparison of cooling structures under a consistent numerical setting, the use of the realizable k-ε turbulence model is valid due to its dampening function, which provides a reasonable approximation in transitional flows, enabling an efficient evaluation within the studied Reynolds numbers.

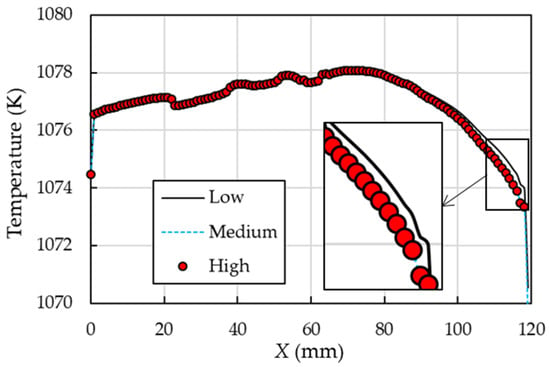

The mesh independence analysis is conducted by comparing the temperature distribution within three mesh systems of 4.21 × 106 (Low), 4.92 × 106 (Medium), and 7.21 × 106 (High) elements. The results in Figure 5 show that all plots are almost identical within the range of 0 mm < X < 100 mm, while small deviations can be observed near the outlet (X ≥ 100 mm). The area-averaged Nusselt number at the endwall in the low and medium meshes is 3.3% and 0.3%, respectively, deviating from the highest mesh resolution. Therefore, the mesh with 4.92 × 106 elements is selected for the conventional topology-optimized model, due to a balance between computational cost and accuracy. Similar mesh settings are applied to all other models.

Figure 5.

Plots of temperature distributions on the endwall with different meshes at Re = 5000.

2.5. Validation

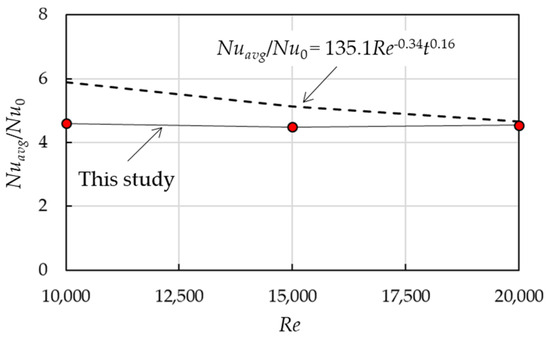

To validate the present numerical models, the average Nusselt number correlation established by Xu et al. [25] from their experimental study of a Diamond TPMS structure is employed. Since their experimental data are acquired via the TLC under adiabatic conditions, a corresponding numerical model is constructed without a solid domain, as shown in Figure 6. In this model, a uniform heat flux is applied directly to the bottom endwall to emulate the TLC measurement technique. The model is validated across a range of Re = 10,000, 15,000, and 20,000, with all other boundary conditions maintained as specified in Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Numerical model of the Diamond-type TPMS structure for the validation.

Figure 7 shows the agreement between the present numerical results and the experimental correlation (Nuavg/Nu0 = 135.1Re−0.34t0.16) established by Xu et al. [25]. The data points from this numerical study closely follow the trend of the empirical correlation within Re = 10,000–20,000. The average deviation in all validated Re is 12.5%, which can be explained by the implemented periodic boundary conditions. By design, this setup excludes the side impingement flow, as found in the experiments, which is a key mechanism for high heat transfer, leading to the observed discrepancy. Therefore, this validation ensures the ability to simulate more complex conjugate heat transfer scenarios accurately.

Figure 7.

Plots of the average Nusselt number ratio between the present study and the correlations from experimental investigation within the Reynolds number of 10,000 to 20,000.

3. Results and Discussion

The thermal–hydraulic performance is characterized by plotting heat transfer and pressure loss to illustrate the effects of coolant flow rate, coolant type, and structural material. The flow and temperature distributions are used to explain the variations in each geometry.

3.1. Influences of Coolant Flow Rate

In this section, to effectively evaluate the influence of coolant flow rate within the range of Re = 300 to 5000, air and ferritic stainless steel are selected as the working fluid and structural material, respectively. Their thermal properties serve to clearly observe the thermal–hydraulic results.

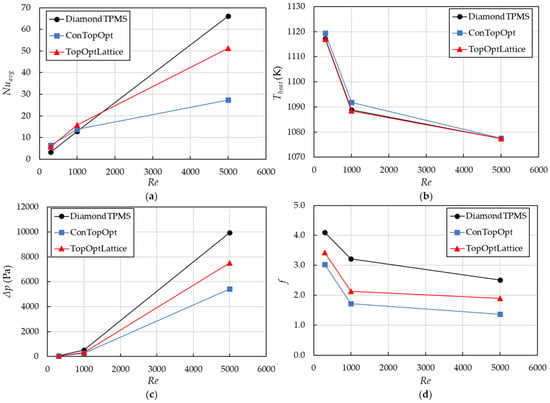

3.1.1. Thermal–Hydraulic Performance

Figure 8 provides the thermo-hydraulic performance within the studied Re for the Diamond-type TPMS structure (DiamondTPMS), conventional topology-optimized structure (ConTopOpt), and topology-optimized lattice-filled structure (TopOptLattice). In Figure 8a, the area-averaged Nusselt number (Nuavg) monotonically increases as Re increases due to higher flow momentum and mixing, resulting in a thinner thermal boundary layer. All models show a competitive and steadily increasing trend at Re = 300 and 1000. The Diamond TPMS geometry, due to its intense flow accumulation [25], achieves the highest Nuavg at higher Re, followed by the topology-optimized lattice-filled model. At Re = 5000, the Nuavg value in the Diamond is 66.1, which is higher than in the conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled models by 58.6% and 22.4%, respectively.

Figure 8.

Thermal–hydraulic performance of all models within the range of the Reynolds numbers of 300 to 5000: (a) area-averaged Nusselt number on the endwall inside the cooling channel; (b) area-averaged temperature on the heated wall; (c) pressure loss; and (d) friction factor.

This enhanced heat removal inside the channel directly reflects the temperature removal from the heated wall in Figure 8b. All models sharply decrease wall temperatures when Re increases from 300 to 1000. At the highest coolant flow rate, the Diamond TPMS model shows the best cooling structure, followed by the topology-optimized lattice-filled model. However, the cooling performance in the Diamond TPMS structure causes the highest pressure loss and friction factor, as shown in Figure 8c,d. A direct consequence of the high pressure is that its topology blocks the flow passing through the cooling channel.

Meanwhile, the conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled models demonstrate a significant advantage, as they exhibit a substantially lower pressure penalty. Compared to the Diamond TPMS model that blocks the through-flow path, the pressure loss in the conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled models is 43.2 Pa to 5417 Pa and 48.9 Pa to 7500 Pa, which decreases by 26.2% to 45.6% and 16.4% to 24.6%, respectively, when the Re increases from 300 to 5000. Moreover, the friction factor, particularly in the conventional topology-optimized model, which allows for a smoother flow and reduces strong vortices, exhibits the lowest values within the studied flow rates and decreases as Re increases, indicating a significantly more hydraulically efficient design.

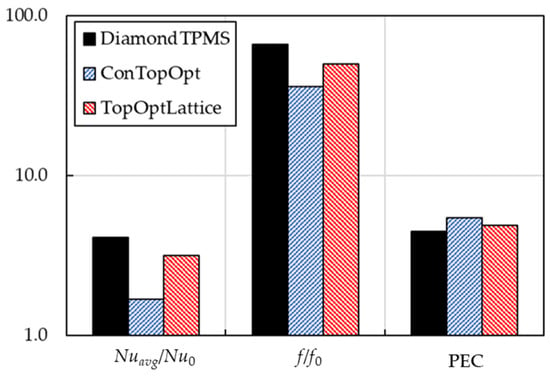

Figure 9 plots the Nu/Nu0, f/f0, and PEC of all geometries at Re = 5000 to evaluate the trade-off between heat transfer enhancement and flow resistance. The Diamond TPMS geometry yields the highest Nu/Nu0 but also incurs the largest f/f0. For all geometries, the PEC values exceed 1.0, confirming a net performance gain. Among them, the conventional topology-optimized model achieves the highest PEC of 5.48, outperforming the Diamond TPMS and lattice-filled models by 22.5% and 11.5%, respectively. This demonstrates that while the Diamond TPMS is most effective at augmenting heat transfer, the conventional topology-optimized design offers a superior overall balance by mitigating the friction penalty.

Figure 9.

Plots of the heat transfer enhancement, friction factor ratio, and the performance evaluation criterion of all models at Re = 5000.

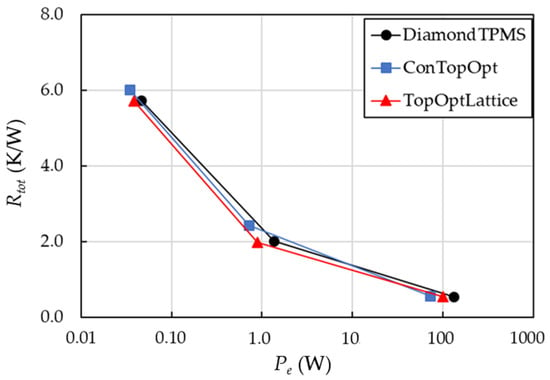

Figure 10 presents the trade-off between thermal performance and energy use by plotting thermal resistance (Rtot) against pumping power (Pe) for all models. The trends are similar to those in Figure 9, where the Diamond TPMS structure consistently requires the highest Pe to achieve a low Rtot, indicating that this cellular-lattice model is less effective at removing heat for a given pumping input. The conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled models obtain a lower Rtot at a given Pe. In this comparison, the topology-optimized lattice-filled model shows the best performance at low Pe, outperforming the Diamond TPMS and conventional topology-optimized geometries. Meanwhile, the conventional topology-optimized geometry obtains a similar Rtot ≈ 0.55 K/W but requires a lower Pe compared to the other models. Beyond overall heat transfer efficiency, the temperature uniformity is a critical requirement for SOFC system integrity. The following section evaluates the flow pattern, heat transfer distribution, and temperature uniformity for all designs.

Figure 10.

Plots of the thermal resistance on the heated walls against pumping power in all models.

3.1.2. Flow Characteristics

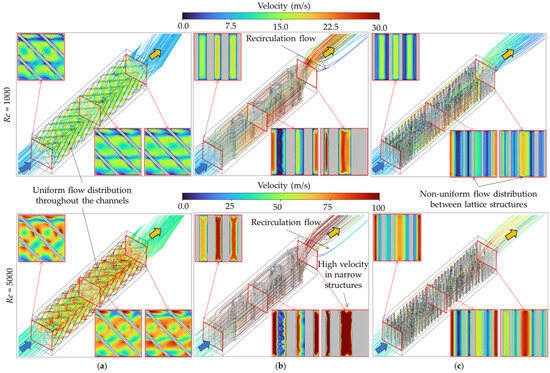

The results in the flow and heat transfer distributions at Re = 300 are excluded because the thermal–hydraulic performance of all geometries is insignificant, making it difficult to distinguish the flow effect. Therefore, the internal flow characteristics of all studied models are compared at Re = 1000 and 5000, as shown in Figure 11. The velocity contours and flow trajectories provide detailed insights into the internal flow characteristics that directly affect the cooling efficiency and temperature uniformity of the SOFC stack. As seen in Figure 11a, the Diamond TPMS lattice exhibits exceptional flow uniformity at both Re values [25]. Its diagonal topology provides consistent flow with minimal recirculation and promotes uniform heat transfer. These flow characteristics imply low thermal gradients across the SOFC components.

Figure 11.

Flow characteristics of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 1000 and 5000: (a) Diamond TPMS model. (b) Conventional topology-optimized model. (c) Topology-optimized lattice-filled model.

In contrast, the conventional topology-optimized design in Figure 11b generates high-velocity jets between the baffles, leading to intense local heat transfer enhancement. However, this model generates strong recirculation zones at the outlet and a highly non-uniform flow distribution within the channel, particularly at Re = 5000. On the other hand, the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure in Figure 11c emerges as a hybrid solution. Although its flow distribution is not perfectly uniform as in the Diamond TPMS model, the integrated lattice structures with large surface areas induce local turbulence and mixing, enhancing overall cooling uniformity more effectively than the conventional topology-optimized model.

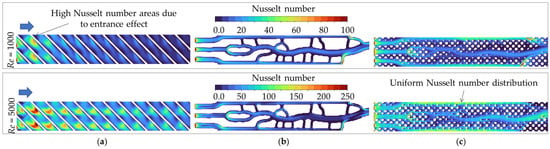

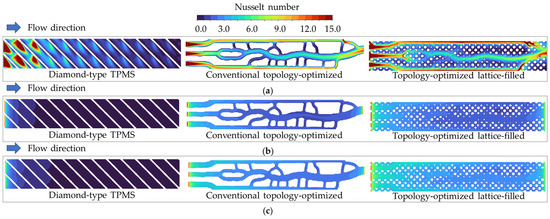

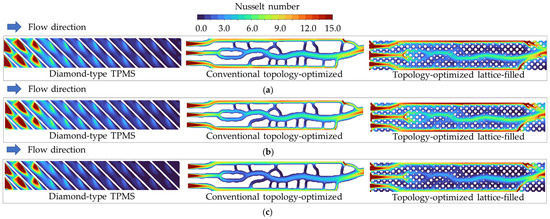

3.1.3. Heat Transfer Distributions

Figure 12 demonstrates the Nusselt number distributions at Re = 1000 and 5000 for all models. The contours indicate local heat transfer intensity, demonstrating the effectiveness and uniformity of convective heat transfer within each geometry. Based on the flow analysis, the Diamond TPMS structure demonstrates a correspondingly uniform and stable Nusselt number distribution at high Re, as seen in Figure 12a. The high flow uniformity translates into consistent heat transfer, confirming its capability for balanced thermal management of the SOFC system.

Figure 12.

Nusselt number distributions on the endwall of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 1000 and 5000: (a) Diamond TPMS model. (b) Conventional topology-optimized model. (c) Topology-optimized lattice-filled model.

The jet impingement on the baffles and intense flow recirculation at the outlet in the conventional topology-optimized design cause non-uniform Nusselt number distribution, as observed in Figure 12b, particularly at high coolant flow rates, which can lead to high thermal stresses. Positively, the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure shows a more significant improvement with increasing flow rate. Although the non-uniform flow distribution at Re = 1000 results in a lower and uneven Nusselt number, the complex lattice interacts to create a uniform and enhanced heat transfer field at Re = 5000. This demonstrates that the lattice-filled design utilizes higher flow rates to improve heat transfer within its large surface area, thereby overcoming initial limitations.

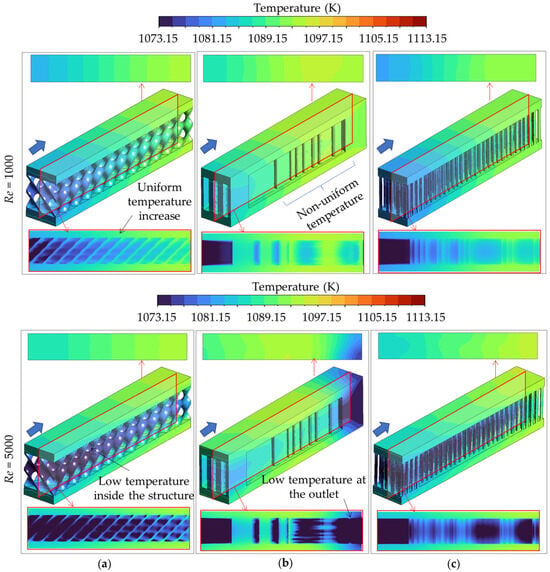

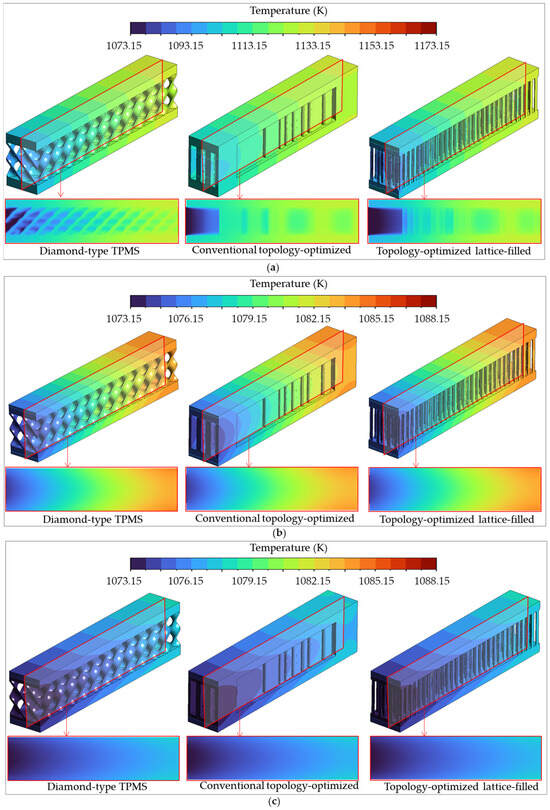

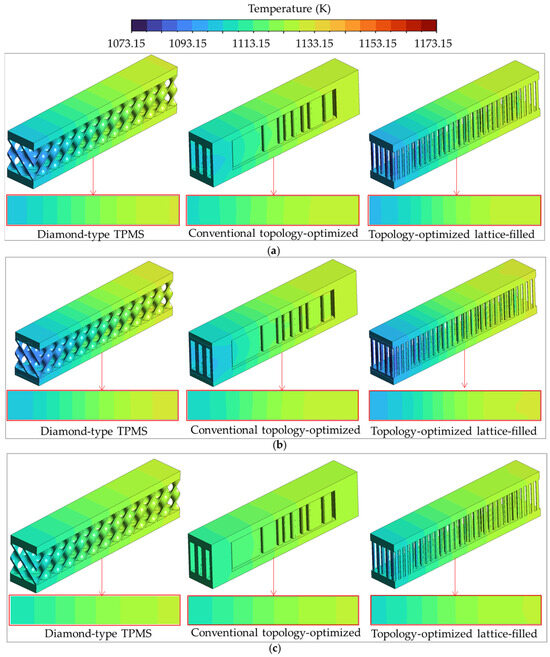

Figure 13 shows the temperature distributions in the solid domain for all models at Re = 1000 and 5000. The temperature contours demonstrate the coolant flow behavior that influences heat removal and temperature uniformity in the cooling channel of the SOFC system. As shown in Figure 13a, the Diamond TPMS structure, consistent with its uniform flow, provides excellent temperature uniformity. However, at Re = 5000, a significant thermal gradient develops between the cooled structure and the heated walls, indicating a high thermal stress when integrating into the SOFC system. The conventional topology-optimized model in Figure 13b, which aligns with its non-uniform flow and Nusselt number distributions, exhibits uneven temperature contours and sharp gradients at both Re values, demonstrating a clear risk for thermal fatigue.

Figure 13.

Temperature distributions on the solid domain of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 1000 and 5000: (a) Diamond TPMS model. (b) Conventional topology-optimized model. (c) Topology-optimized lattice-filled model.

While the non-uniform flow characteristics in the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure at Re = 1000 lead to significant temperature variations, the high flow rate enhances mixing within the lattice, generating a uniform and lower overall temperature field. This structure also reduces the temperature imbalance found in the Diamond model and the high temperature in the conventional topology-optimized design. By combining a topologically guided flow path with a high-surface-area lattice, this complex structure shows a superior temperature uniformity at high coolant flow rates, ensuring effective heat dissipation and minimizing thermal variation, thereby enhancing SOFC reliability.

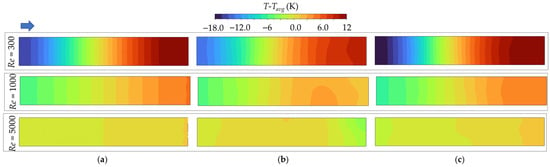

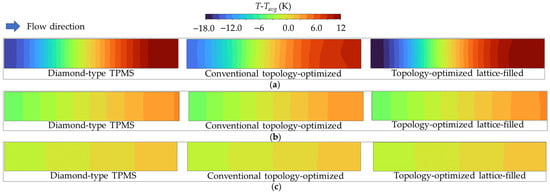

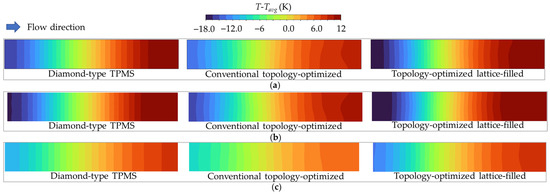

3.1.4. Temperature Uniformity

Figure 14 shows the temperature uniformity (T-Tavg) on the heated wall for all models within the range of Re = 300–5000. The color scale, ranging from −18 K to +12 K, indicates that values closer to zero signify superior temperature uniformity. Among them, the Diamond TPMS structure in Figure 14a exhibits minimal temperature deviation from Re = 300 to Re = 5000, confirming its inherent design provides highly uniform temperature on the heated wall. Meanwhile, the conventional topology-optimized structure in Figure 14b causes a lower temperature uniformity, particularly at Re = 5000. Large and contiguous zones of positive and negative deviations are evident, revealing inherent non-uniform flow distribution, which is due to recirculation and stagnant zones. This temperature pattern fails to achieve the reliability for thermal management of the SOFC system at high coolant flow rates.

Figure 14.

Contours of the temperature variation on the heated wall of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 300, 1000, and 5000: (a) Diamond TPMS model. (b) Conventional topology-optimized model. (c) Topology-optimized lattice-filled model.

The topology-optimized lattice-filled structure in Figure 14c improves the temperature uniformity with increasing flow rate. At Re = 5000, this model achieves temperature uniformity similar to that of the Diamond TPMS model, demonstrating its advanced design effectively leverages higher flow inertia to activate uniform cooling across a complex structure. The topology-optimized lattice-fill structure could be an excellent candidate in the cooling channel between the SOFC stack, especially for high cooling air supplies.

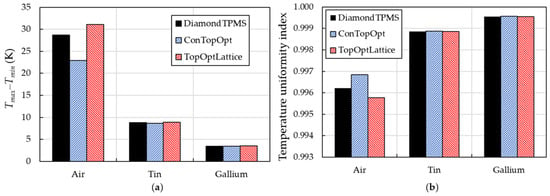

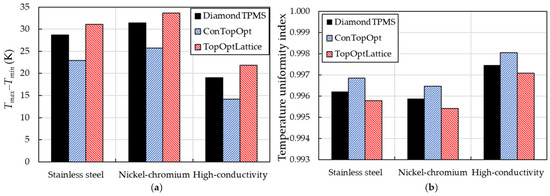

Figure 15 provides quantitative values of the temperature range (Tmax–Tmin) and a temperature uniformity index (TUI) against Re. In Figure 15a, the conventional topology-optimized model exhibits the lowest temperature range (Tmax–Tmin) value of 23 K and 8.6 K when Re = 300 and 1000, while the Diamond TPMS and topology-optimized lattice-filled structures show a smaller temperature range of around 2 K at Re = 5000. Here, the smaller (Tmax–Tmin) value indicates a more uniform temperature field by minimizing the difference between the hottest and coldest spots, which is critical for reducing thermal stresses.

Figure 15.

Evaluation of temperature uniformity on the bottom heated wall of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 300, 1000, and 5000: (a) Tmax–Tmin and (b) temperature uniformity index.

This superior performance is further validated in Figure 15b by the TUI, where a value closer to 1.0 represents perfect uniformity. The Diamond TPMS structure achieves the highest index values, confirming its excellent thermal distribution at Re = 5000. While the conventional topology-optimized models perform well at low Re values, the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure slightly exceeds its uniformity at higher flow rates. Overall, the analyses in this section demonstrate that the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure offers a highly uniform thermal environment on the heated wall of the air-cooled SOFC system, indicating that it is the optimal design for mitigating thermal stress and ensuring reliable operation at high cooling air flow rates in this study.

3.2. Effect of Coolant Type

To isolate the influence of coolant flow rate on thermal performance, the thermal–hydraulic performance, heat transfer distribution, and temperature uniformity are analyzed at Re = 300. The following analysis utilizes a ferritic stainless steel structure to compare three coolants: air, liquid tin, and liquid gallium.

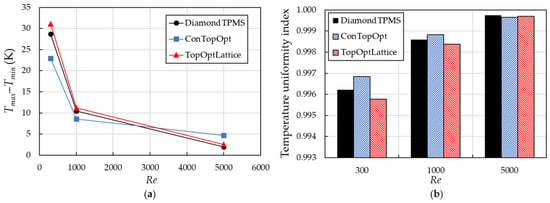

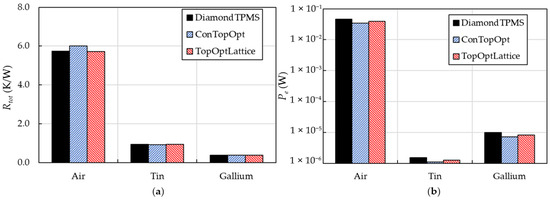

3.2.1. Thermal–Hydraulic Performance

Figure 16 compares the thermal–hydraulic performance of all models under three coolant types at Re = 300. The conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled structures achieve Nuavg approximately twice that of the Diamond TPMS with air cooling, as shown in Figure 16a, due to their enhanced flow redistribution and mixing. While liquid metals yield lower Nusselt number values of Nuavg < 4 [19], the topology-optimized lattice-filled model slightly outperforms others, as its complex lattice promotes mixing even in low-flow-rate liquid metals. This translates directly to the temperature on the heated wall in Figure 16b, where liquid metals reduce wall temperatures by up to 43 K compared to air, with the gallium-cooled channel obtaining the lowest values.

Figure 16.

Thermal–hydraulic performance of all models with different coolants at Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) area-averaged Nusselt number on the endwall inside the cooling channel; (b) area-averaged temperature on the heated wall; (c) pressure loss; and (d) friction factor.

Figure 16c reveals that pressure loss is governed by both fluid properties and channel topology. For the air-cooled channel, the Diamond TPMS structure exhibits the highest pressure loss of 58.5 Pa, while the conventional topology-optimized model achieves the lowest. For liquid tin and gallium, the pressure losses are significantly lower than those of the air-cooled channel due to their higher density and lower dynamic viscosity, which drastically reduces fluid flow resistance at an equivalent Re. The f in Figure 16d further elucidates this hydraulic behavior, where the Diamond TPMS model exhibits the highest f value, ranging from 4.1 to 14.2, which is 26.2% to 27.2% higher than the conventional topology-optimized model, and from 16.4% to 16.9% higher than the lattice-filled design for all coolant types. The topology-optimized lattice-filled model exhibits an obviously higher f value than the conventional topology-optimized model, by 13.2% to 14.2%, because of its finer internal structures, which strongly interact with the high density of the liquid metals.

Figure 17 compares the Rtot and Pe for all designs with different coolants at Re = 300. As shown in Figure 17a, the Rtot decreases significantly when the coolant is changed from air to liquid metals. The air-cooled channel exhibits the highest Rtot in all geometries due to its inherently low thermal conductivity and heat capacity. Meanwhile, the liquid tin and gallium achieve higher performance, with gallium offering the lowest Rtot ≈ 0.25 K/W, a reduction of 93%. A noticeable difference of approximately 60% between the liquid metals is due to variations in coolant conductivity. Notably, the geometric differences cause only minor changes in the Rtot with liquid metals, confirming that the coolant properties dominate heat transfer under these flow conditions. Overall, for the air-cooled channel, the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure exhibits the best performance. Meanwhile, for liquid metals, the conventional topology-optimized geometry is the most effective, indicating that its baffle structures are more efficient in removing heat at low coolant flow rates.

Figure 17.

Influence of coolant type on: (a) thermal resistance and (b) pumping power for all models at Reynolds numbers of 300.

Figure 17b reveals that air cooling requires the highest Pe of 0.047 W, despite its low heat transfer performance, which is attributed to its low density requiring high volumetric flow rates [18]. The liquid metals significantly reduce pumping requirements, with liquid tin exhibiting the lowest Pe of up to 100% compared to the air-cooled channel, due to its viscosity–density balance. The higher viscosity and density of the gallium-cooled channel result in a 5.6% increase in its Pe compared to the tin-cooled channel. Overall, the geometric design influences on the Pe are minor for liquid metals but more pronounced for air, where the Diamond TPMS model shows higher losses.

3.2.2. Heat Transfer Distributions

Figure 18 shows the effect of coolant types on the Nusselt number distributions for all models at Re = 300. The liquid metal-cooled channels exhibit lower Nusselt numbers than the air-cooled channel despite their superior performance. It is essential to clarify that the Nusselt number is a measure of the convective relative to the conductive heat transfer. The relatively high thermal conductivity of liquid metals is the primary mechanism for their effectiveness, enabling rapid heat transfer through conduction rather than convection. This results in a lower temperature difference between the wall and the bulk fluid, which leads to a lower Nusselt number. While the air-cooled channel exhibits high Nusselt numbers, the tin- and gallium-cooled channels maintain a more uniform Nusselt number along the flow direction, even at this low flow rate. Furthermore, the Diamond TPMS structure creates a high heat transfer only at the channel entrance, whereas the conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled models maintain a more uniform distribution.

Figure 18.

Nusselt number distributions on the endwall of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Air-cooled channel. (b) Liquid tin-cooled channel. (c) Liquid gallium-cooled channel.

A comparison of the liquid-metal coolants reveals that the gallium-cooled channel in Figure 18c generates a higher magnitude and a more uniform Nusselt number distribution than the tin in Figure 18b. It is noticeable that the conventional topology-optimized structures consistently demonstrate the most uniform distributions when using liquid gallium. This optimal performance arises from the combination of high thermal conductivity in the liquid gallium and the baffle topology, which provides a simple and large surface area for heat exchange while maintaining smooth flow pathways that enable efficient heat removal.

The temperature fields on the solid domain for the three coolant types at Re = 300 are compared in Figure 19. The cross-sectional views show that although the constant flow rate offers a similar temperature trend in all geometries, the liquid tin and gallium generate substantially lower and more uniform temperature distributions than the air-cooled channel. Specifically, the gallium-cooled channel in Figure 19c exhibits the most uniform temperature and the lowest peak temperature, closely followed by the tin-cooled channel in Figure 19b. Meanwhile, the air cooling in Figure 19a results in non-uniform and high peak temperatures, indicating that it is unsuitable for the cooling channel of the SOFC without substantial geometric or operational adjustments.

Figure 19.

Temperature distributions on the solid domain of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Air-cooled channel. (b) Liquid tin-cooled channel. (c) Liquid gallium-cooled channel.

3.2.3. Temperature Uniformity

Figure 20 shows the impact of coolant type on the temperature uniformity for all designs at Re = 300. A dominant trend of all structures is the profound improvement in temperature uniformity when using liquid tin and gallium coolants compared to air. The air-cooled channels in Figure 20a exhibit the largest temperature change, indicating poor heat spreading and a high risk of thermal stress. On the other hand, both liquid metal coolants provide more uniform temperature fields, with significantly smaller deviations concentrated near zero. Among the liquid metals, the gallium-cooled channel in Figure 20c yields the most uniform temperature distributions, slightly outperforming the liquid tin-cooled channel in Figure 20b. This is also consistent with the higher thermal conductivity of the liquid gallium [19]. Regarding the geometries, the conventional topology-optimized structure consistently demonstrates the best uniformity with the liquid-metal coolants. Its optimized-baffle design integrates well with high-conductivity liquid metals to create a uniform temperature contour.

Figure 20.

Contours of the temperature variation on the heated wall of all models at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Air-cooled channel. (b) Liquid tin-cooled channel. (c) Liquid gallium-cooled channel.

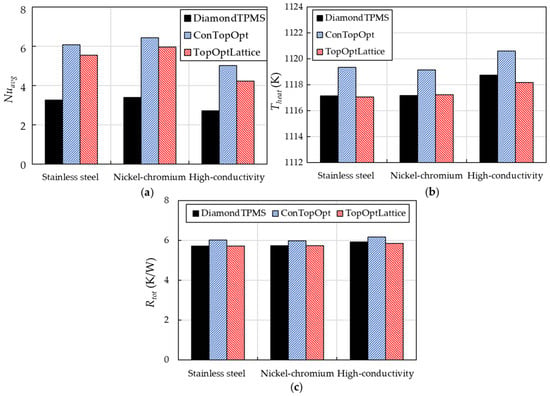

Figure 21 quantitatively evaluates the temperature uniformity on the heated wall for all models using air, liquid tin, and liquid gallium as coolants at Re = 300. With the air-cooled channel, all geometries exhibit significant temperature differences (Tmax–Tmin) up to 30 K and lower temperature uniformity index values, indicating limited heat spreading capability. Among the designs, the conventional topology-optimized model achieves the best air-cooled performance due to its simple baffle cooling structures, which enable smooth flow at low Re. In contrast, the liquid metals drastically improve temperature uniformity, reducing the temperature difference value to below 10 K and achieving temperature uniformity index values close to 1.0. The gallium-cooled channel performs slightly better than the tin, yielding differences below 5 K due to its superior thermal conductivity. These results confirm that while the geometry influences convective heat transfer, the coolant properties dominate temperature uniformity. Consequently, these findings affirm the promise of liquid-metal coolants for thermal management in high-power-density SOFCs, though practical integration issues remain to be improved.

Figure 21.

Evaluation of temperature uniformity on the bottom heated wall of all models with different coolants at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Tmax–Tmin and (b) Temperature uniformity index.

Although these findings affirm the excellence of liquid-metal coolants for thermal management in high-power-density SOFCs, their practical implementation in the SOFCs requires careful consideration of material compatibility, corrosion, and cost. The liquid tin is highly corrosive to ferritic stainless steel under high operating temperatures of the SOFCs, necessitating the use of specialized nickel-based superalloys or protective ceramic coatings [15]. The liquid gallium could cause embrittlement in many structural metals and is significantly more expensive than liquid tin. Moreover, these liquid metals face wetting issues in highly complex channels. Thus, their thermal benefits must be balanced against higher costs, material problems, and potential long-term degradation.

3.3. Effect of Structural Material

This section evaluates the impact of various structural materials on the thermal performance of the air-cooled channel. A comparative analysis of pressure loss shows insignificant variation between different structural materials at Re = 300; consequently, the discussion is confined to thermal characteristics.

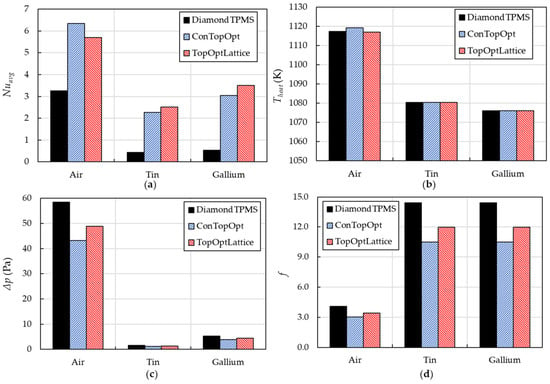

3.3.1. Heat Transfer Performance

Figure 22 illustrates the comparison of thermal performance parameters for all air-cooled geometries, fabricated with three different solid materials at Re = 300. The Nuavg is substantially higher in the conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled configurations than in the Diamond TPMS structure across all structural materials, as seen in Figure 22a. The improvement is significant, with the Nuavg increases of 56–89% over the Diamond TPMS model. The stainless steel and nickel–chromium structures provide similar value, which is slightly higher than that of the high-thermal-conductivity metal.

Figure 22.

Thermal performance of all air-cooled geometries at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) area-averaged Nusselt number on the endwall inside the cooling channel; (b) area-averaged temperature on the heated wall, and (c) Thermal resistance.

Despite these convective heat transfer increases, the conventional topology-optimized model exhibits higher Theat than the Diamond TPMS structure, as found in Figure 22b. This indicates that convective enhancement alone does not dictate the final wall temperature. The high-thermal-conduction metal causes a slightly higher Theat value than the others. Lastly, the Rtot shows a similar value in all designs in Figure 22c, indicating that the high convective heat transfer does not translate proportionally into lower thermal resistance with different structural materials. It could also be deduced that the performance of the flow and heat transfer conditions in this study is governed by a complex balance between convection and conduction.

3.3.2. Heat Transfer Distributions

Figure 23 illustrates the Nusselt number distributions on the endwall of all designs for different structural materials at Re = 300. In the ferritic stainless-steel and nickel–chromium superalloy cases, as shown in Figure 23a,b, the conventional topology-optimized geometry generates high Nusselt number values along the flow direction, indicating improved convective mixing at low coolant flow rate. In contrast, the Diamond TPMS model exhibits alternating high- and low-Nusselt number values, resulting from periodic flow recirculation, which leads to more pronounced local hot spots [25]. The topology-optimized lattice-filled structure exhibits intermediate behavior, maintaining relatively continuous high-Nusselt number regions near flow passage intersections.

Figure 23.

Nusselt number distributions on the endwall of all air-cooled geometries at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Ferritic stainless steel. (b) Nickel–chromium superalloy. (c) High-thermal-conductivity metal.

When replacing the structural material with a high-thermal-conductivity metal in Figure 23c, the Nusselt number gradients become clearly non-uniform. Although the increased thermal conductivity promotes lateral heat spreading within the solid, a non-uniform endwall temperature distribution can be observed. Consequently, the distinction between high- and low-Nusselt number zones becomes more prominent. Among all designs, the topology-optimized lattice-filled maintains the high uniform Nusselt number regions, confirming that the topology optimization effectively tailors the internal flow paths to maximize thermal utilization of the coolant under air-cooling conditions.

Figure 24 presents the temperature distributions on the solid domain of all air-cooled geometries at Re = 300 for different structural materials. In the ferritic stainless-steel and nickel–chromium superalloy cases shown in Figure 24a,b, all designs exhibit noticeable temperature gradients along the flow direction, with higher temperatures near the outlet region, particularly in the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure. The conventional topology-optimized structure shows the most uniform temperature distribution, although it demonstrates slightly lower temperatures, followed by the Diamond TPMS model.

Figure 24.

Temperature distributions on the solid domain of all air-cooled geometries at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Ferritic stainless steel. (b) Nickel–chromium superalloy. (c) High-thermal-conductivity metal.

As the material changes to the high-thermal-conductivity metal in Figure 24c, the overall temperature levels increase, but the temperature variations become smaller, which can be attributed to lateral heat spreading within the solid wall, significantly reducing the thermal nonuniformity between the inlet and outlet. In this material condition, the temperature contours in all geometries become more uniform, indicating that material thermal conductivity has a significant influence on the wall temperature distribution. Nevertheless, the conventional topology-optimized configuration consistently provides the lowest temperature variation among all designs.

3.3.3. Temperature Uniformity

Figure 25 illustrates the contours of temperature variation (T-Tavg) on the heated walls of all air-cooled geometries at Re = 300 for different materials. Similar to the previous discussion, the ferritic stainless steel in Figure 25a and the nickel–chromium superalloy in Figure 25b cause significant temperature gradients. The conventional topology-optimized model exhibits the most non-uniform temperature distribution, a consequence of its less complex structure, which allows smooth flow between the baffles at low Re. The transition to the high-thermal-conductivity metal in Figure 25c shows a more uniform temperature contour. This improvement signifies that heat is being effectively conducted from hot spots, creating a more isothermal heated surface.

Figure 25.

Contours of the temperature variation on the heated wall of all air-cooled geometries at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Ferritic stainless steel. (b) Nickel–chromium superalloy. (c) High-thermal-conductivity metal.

Figure 26 evaluates the temperature uniformity on the heated wall of all air-cooled designs, fabricated from different materials, at Re = 300. For all materials, the conventional topology-optimized configuration exhibits the smallest temperature range (Tmax–Tmin) of 16 K to 30 K, as shown in Figure 26a, indicating superior temperature uniformity compared to the other geometries. Meanwhile, the topology-optimized lattice-filled structure causes the largest temperature range values, spanning 40 K to 51 K, due to complex flow recirculation behind each lattice, particularly at low Re. As the thermal conductivity of the wall material increases, from ferritic stainless steel to high-thermal-conductivity metals, the overall temperature range decreases across all designs, and the conventional topology-optimized model achieves the lowest temperature range of 16 K.

Figure 26.

Evaluation of temperature uniformity on the bottom heated wall of all air-cooled geometries with different structural materials at the Reynolds numbers of 300: (a) Tmax–Tmin and (b) temperature uniformity index.

A similar trend is observed in the temperature uniformity index in Figure 26b, where the conventional topology-optimized model achieves the highest index for all materials. The topology-optimized lattice-filled model slightly reduces uniformity despite its enhanced surface area, implying that excessive internal complexity may hinder uniform cooling, particularly at low coolant flow rates. The Diamond TPMS model maintains moderate uniformity across studied materials, benefiting from its periodic structure but limited by reduced internal mixing.

The superior temperature uniformity observed with high-conductivity materials can also be quantitatively explained by the Biot number. For all geometries at Re = 300, the Biot number is significantly less than 0.1. This occurs because the intricate structures have a very small characteristic length, defined by the ratio of solid volume to wetted surface area. Among the materials, the high-thermal-conductivity metal yields the lowest Biot number, confirming its minimal internal conductive resistance relative to the external convective resistance and thus the most uniform temperature field.

Overall, these findings indicate that for the air-cooled system utilizing high-conductivity materials and low coolant flow rates, the baffle-shaped designs (the conventional topology-optimized model) that enable low pressure loss and a smooth flow field are the most suitable for thermal management of the SOFC stack.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a conjugate analysis of cooling channel designs, including the Diamond TPMS, conventional topology-optimized, and topology-optimized lattice-filled structures, which integrate between the SOFCs to improve thermal management. The investigation assesses the impact of coolant flow rate, coolant type, and structural material on thermal–hydraulic performance and temperature uniformity. The conclusions can be drawn as follows:

- (1)

- The Diamond TPMS structure provides excellent flow and heat transfer distribution, but causes a significant pressure penalty of 45.6% and 24.6% at Re = 5000, compared to the conventional topology-optimized and lattice-filled designs. The conventional optimized model minimizes pressure loss but can lead to non-uniform flow and temperature distributions at high flow rates. The topology-optimized lattice-filled structure emerges as an excellent compromise, especially at high Re. By combining the tailored flow paths from topology optimization with the high surface area of a lattice-filled array, this design in the air-cooled system achieves temperature uniformity comparable to that of the Diamond TPMS at Re = 5000, while incurring a significant reduction in pressure loss penalty.

- (2)

- While both topology-optimized designs can improve convective heat transfer, the choice of coolant is found to be the highest dominant factor, governing the thermal–hydraulic performance. The transition coolants from air to liquid metals resulted in a significant reduction in thermal resistance, up to 93%, and a relatively high temperature uniformity index at Re = 300. The liquid gallium, with its superior thermal conductivity, outperformed liquid tin, achieving the most uniform temperature distributions on the heated wall, where the differences between the maximum and minimum temperatures (Tmax–Tmin) are less than 5 K in both topology-optimized designs. However, the excellent cooling performance of liquid metals might come with a higher cost and greater engineering challenges.

- (3)

- A higher thermal conductivity material improves heat spreading within the solid structure, creating a more uniform temperature in all geometries. Under low coolant flow rates and air-cooled conditions, the baffle-like structures in the conventional topology-optimized model exhibit preferable thermal–hydraulic performance, facilitating a smooth flow field, and achieve the lowest temperature range (Tmax–Tmin) of 16 K at Re = 300.

- (4)

- For maximum performance, employing a liquid metal coolant within the optimized-baffle design channel is highly recommended for the precise thermal management of the SOFC. This configuration leverages their balanced thermal–hydraulic performance and the high thermal conductivity of the liquid metals. Additionally, fabricating the channel with a high thermal conductivity material for a conventional topology-optimized design further achieves better temperature uniformity while minimizing parasitic power.

The design strategies outlined in this work offer an alternative approach to enhancing the thermal management of SOFC systems, providing significantly improved temperature uniformity. To transition these concepts from simplified simulations to real-world applications, future investigations could establish full-system computational modeling and experimental validation to quantify the realistic performance improvements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y. and Y.R.; methodology, K.Y. and Y.C.; software, K.Y.; validation, K.Y. and Y.C.; formal analysis, K.Y. and Y.C.; investigation, K.Y. and Y.C.; resources, K.Y. and Y.R.; data curation, K.Y. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.Y., Y.R. and Y.C.; visualization, K.Y. and Y.C.; supervision, Y.R.; project administration, Y.R.; funding acquisition, K.Y. and Y.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11972230, 24Z033103800), the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2017-III-0009-0035), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 24110712700).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Yu Rao gratefully acknowledges support from the Shandong Provincial Industrial Leading Talents Project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Ai | Local area (m2) |

| Ain | Inlet area of the cooling channel (m) |

| D | Characteristic length (m) |

| Dh | Hydraulic diameter of the cooling channel (m), defined in Equation (2) |

| Dp | Diameter of the circular pin-fin structure (m) |

| f | Friction factor, defined in Equation (6) |

| f0 | Blasius correlations, defined in Equation (10) |

| h | Heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2∙K), defined in Equation (4) |

| Tb | Bulk flow temperature (K) |

| Theat | Temperature of the heated wall (K) |

| Tin, Tout | Inlet and outlet coolant temperatures (K) |

| Ti | Local temperature (K) |

| Tmax, Tmin | Maximum and minimum temperature on the heated wall (K) |

| Tw | Endwall temperature(K) |

| L | Length of the cooling structure (m) |

| Lp | Wetted perimeter (m) |

| Nu | Nusselt number, defined in Equation (3) |

| Nuavg | Area-averaged Nusselt number |

| Nu0 | Dittus-Boelter equation, defined in Equation (9) |

| q | Wall heat flux (W/m2) |

| k | Thermal conductivity of the fluid (W/m·K) |

| Pe | Pumping power (W), defined in Equation (7) |

| pin | Coolant inlet pressure (Pa) |

| Re | Reynolds number, defined in Equation (1) |

| Rtot | Total thermal resistance (K/W), defined in Equation (5) |

| Sv | Specific area surface (m2/m3) |

| Vin | Velocity at the inlet (m/s) |

| X, Y, Z | Cartesian coordinate |

| Greek letter | |

| γ | Density field in the topology optimization |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity of the coolant (Pa∙s) |

| ρ | Density of the coolant (kg/m3) |

| ∆p | Different pressure between the inlet and outlet boundaries (Pa) |

| Гin | Inlet boundary |

| ψ | Porosity (%) |

| Abbreviations | |

| CHT | Conjugate heat transfer |

| PEC | Performance evaluation criterion, defined in Equation (8) |

| PEMFCs | Proton-exchange membrane fuel cells |

| PEN | Positive electrode-electrolyte-negative electrode |

| TLC | Transient liquid crystal thermography |

| TPMS | Triply periodic minimal surface |

| TUI | Temperature uniformity index, defined in Equation (11) |

| SOFC | Solid-oxide fuel cell |

Appendix A

The density-based topology optimization is used to maximize heat transfer within the internal cooling channel. This method solves a material distribution problem, defining an optimal layout of fluid and solid phases within the design domain (Ω). A continuous design variable (γ) represents the material distribution, ranging from 0 (solid) to 1 (fluid) at any cell in the design domain. A review of this approach for cooling channels is available in Refs [26,27].

To reduce the high computational cost required for convergence, a simplified 2D model is employed, as shown in Figure A1. The symmetry boundary conditions are applied to the side walls to further accelerate the optimization process. The inlet velocity (Vin) is typically used to determine the Reynolds number (Re). However, during topology optimization, the channel geometry changes, which alters the inlet velocity even when the input power is held constant. To maintain a consistent basis for comparison at fixed input power, the following integral equation for inlet pressure is derived [27], as follows:

where pin is the coolant inlet pressure. u is the velocity component in the X-axis.

Figure A1.

Design domain and boundary conditions of the optimization model.

In this topology optimization, the Reynolds number, based on the coolant hydraulic diameter, is maintained at 10,000 to facilitate the simulation. The heat generation coefficient (hgen), which governs the rate of heat generation, is set to 1.3 × 106 W/(m3K) to promote the formation of a complex structure. TQ is a constant temperature applied at the heat source. A volume constraint with a volume fraction of 0.5 is also imposed. The governing equations, material interpolations, problem formulation, filtering, projection, and optimization procedures follow established methods from previous studies.

The intermediate densities (0.1 ≤ γ ≤ 0.9) from the topology optimization are interpreted as an array of circular pin-fins, as shown in Figure A2. This optimized 2D layout is extruded to a 20 mm height to form a 3D lattice structure. The pin diameter (Dp) varies consistently with the local density field, ranging from Dp = 1 mm for γ = 0.9 to Dp = 2 mm for γ = 0.1. The pin-fin configuration is selected for its compatibility with traditional manufacturing and its suitability for integration within the narrow interconnects of an SOFC stack.

Figure A2.

Procedure to obtain the cooling channel with a topology-optimized lattice-filled structure.

Table A1.

The hydraulic diameter calculated based on the porous media definition.

Table A1.

The hydraulic diameter calculated based on the porous media definition.

| Geometry | Diamond TPMS Model | Conventional Topology-Optimized Model | Topology-Optimized Lattice-Filled Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic diameter (mm) | 6.65 | 5.55 | 5.3 |

References

- Lin, C.; Kerscher, F.; Spliethoff, H. Thermal Gradient Management in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Future Directions. J. Power Sources 2025, 656, 238017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veza, I. Fuel-Cell Thermal Management Strategies for Enhanced Performance: Review of Fuel-Cell Thermal Management in Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs) and Solid-Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs). Hydrogen 2025, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, C.; Dan, D.; Zhuge, W. A Review of Heat Transfer and Thermal Management Methods for Temperature Gradient Reduction in Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) Stacks. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 115899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, P.; Adjiman, C.S.; Brandon, N.P. Anode-Supported Intermediate-Temperature Direct Internal Reforming Solid Oxide Fuel Cell: II. Model-Based Dynamic Performance and Control. J. Power Sources 2005, 147, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manglik, R.M.; Magar, Y.N. Heat and Mass Transfer in Planar Anode-Supported Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: Effects of Interconnect Fuel/Oxidant Channel Flow Cross Section. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2015, 7, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.F.; Sá, L.F.N.; Lopes, T.; Meneghini, J.R.; Silva, E.C.N. Design of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) Channel Layout Using the Topology Optimization Method with a Design Variable Propagation Approach. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2024, 67, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Su, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Jiao, Z. Microstructure-Insight Topology Optimization for Efficient Interconnect Flow Channels in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 242, 126823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lang, M.; Costa, R.; Lee, I.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Hong, J. Enhancing Uniformity and Performance in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Double Symmetry Interconnect Design. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Luo, X.; Tu, Z.; Chan, S.H. A Novel Flow Channel Design to Achieve High Temperature Homogenization in Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillig, M.; Plankenbühler, T.; Karl, J. Thermal Effects of Planar High Temperature Heat Pipes in Solid Oxide Cell Stacks Operated with Internal Methane Reforming. J. Power Sources 2018, 373, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillig, M.; Meyer, T.; Karl, J. Integration of Planar Heat Pipes to Solid Oxide Cell Short Stacks. Fuel Cells 2015, 15, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokmaingam, P.; Irvine, J.T.S.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Charojrochkul, S.; Laosiripojana, N. Modeling of IT-SOFC with Indirect Internal Reforming Operation Fueled by Methane: Effect of Oxygen Adding as Autothermal Reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 13271–13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillig, M.; Leimert, J.; Karl, J. Planar High Temperature Heat Pipes for SOFC/SOEC Stack Applications. Fuel Cells 2014, 14, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cheng, K.; Li, B.; Liu, H.; Qin, J.; Wei, L. Feasibility Study on Supercritical Fuel Cooled Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Stack with Internal Reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, R.; Shi, J.; Shi, Y.; Cao, H.; Cai, N. Thermal Management of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Liquid Metal. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 10659–10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promsen, M.; Komatsu, Y.; Sciazko, A.; Kaneko, S.; Shikazono, N. Feasibility Study on Saturated Water Cooled Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Stack. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; An, B.; Tu, S. Effect of Operation Parameters on the Thermal Characteristics in a Planar Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 33, 1974–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.; Blum, L.; Deja, R.; Hoven, I.; Tiedemann, W.; Küpper, S.; Stolten, D. Operation Experience with a 20 KW SOFC System. Fuel Cells 2014, 14, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbi, S.; Amber, I.; Hossain, M.; Leong, K.Y.; Saharudin, M.S. Feasibility Study of Liquid Metal-Based Thermal Management for Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cell (SOEC). Int. J. Green Energy 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Bian, H.; Zhang, K. Advances in Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Structures for Thermal Management Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeranee, K.; Rao, Y. A Review of Recent Investigations on Flow and Heat Transfer Enhancement in Cooling Channels Embedded with Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMS). Energies 2022, 15, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, J.; Liang, X.; To, A.C. Coupling Lattice Structure Topology Optimization with Design-Dependent Feature Evolution for Additive Manufactured Heat Conduction Design. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2018, 332, 408–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Lei, N.; Luo, Z.; Liu, L. Meshless Optimization of Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Based Two-Fluid Heat Exchanger. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2023, 162, 103554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeranee, K.; Xu, C.; Rao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Experimental and Numerical Study of Improving Flow and Heat Transfer in a Serpentine Cooling Channel with Topology-Optimized TPMS Porous Structures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 231, 125873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Rao, Y.; Yeranee, K. Experiments and Numerical Analysis of Turbulent Flow Heat Transfer and Pressure Loss of a Channel with Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Structures. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 220, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, X.; Jing, D.; Xiong, M.; Meng, F. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Liquid-Cooled Heat Sinks Designed by Topology Optimization. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 146, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumori, T.; Kondoh, T.; Kawamoto, A.; Nomura, T. Topology Optimization for Fluid-Thermal Interaction Problems under Constant Input Power. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2013, 47, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.M.; Yu, S.H.; Nam, J.H.; Kim, C.J. A Numerical Study on Uniform Cooling of Large-Scale PEMFCs with Different Coolant Flow Field Designs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, S.; Desouza, A.; Bahrami, M.; Kjeang, E. Thermal Analysis of Air-Cooled PEM Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 18261–18271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, J.W. Metallic Interconnects for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 397, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, B.; Vijayaraghavan, K. 3D and Simplified Pseudo-2D Modeling of Single Cell of a High Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cell to Be Used for Online Control Strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 9733–9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhang, D.; Kuai, Z. Modeling and Performance Analysis of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Power Generation System for Hypersonic Vehicles. Aerospace 2024, 11, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haertel, J.; Engelbrecht, K.; Lazarov, B.; Sigmund, O. Topology Optimization of a Pseudo 3D Thermofluid Heat Sink Model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 121, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Lee, P. Topology Optimization of Liquid-Cooled Microchannel Heat Sinks: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 142, 118401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Kanargi, B.; Lee, P. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of a Mini Channel Forced Air Heat Sink Designed by Topology Optimization. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 121, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Sun, Q.; Lee, P.S. Thermohydraulic Analysis of a New Fin Pattern Derived from Topology Optimized Heat Sink Structures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 147, 118909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.D.; Lee, P.S. 3D Topology Optimisation of Liquid-Cooled Microchannel Heat Sinks. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 33, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, E.; Ni, M.; Zheng, K.; Ouyang, M.; Hu, H.; Wang, H.; Lu, L.; Ren, D.; Chen, Y. A Numerical Analysis of Metal-Supported Solid Oxide Fuel Cell with a Focus on Temperature Field. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).