Abstract

As demand for heat and power continues to grow, production planning of a combined heat and power (CHP) system becomes one of the most crucial optimization problems. Due to the fluctuations in demand and production costs of heat and power, it is necessary to quickly solve the production planning problem of the contemporary CHP system. In this paper, we propose a Hybrid Time series Informed neural Network (HYTIN) in which, a deep learning-based planner for CHP production planning predicts production levels for heat and power for each time step. Specifically, HYTIN supports inventory-aware decisions by utilizing a long short-term memory network for heat production and a convolutional neural network for power production. To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we build ten independent test datasets of 1200 h each with feasible initial states and common limits. Experimentation results demonstrate that HYTIN achieves lower operation cost than the other baseline methods considered in this paper while maintaining quick inference time, suggesting the viability of HYTIN when constructing production plans under dynamic variations in demand in CHP systems.

1. Introduction

While demand for heat and power grows and places greater pressure on energy systems, combined heat and power (CHP) offers a higher efficiency pathway to meet this demand more sustainably [1,2]. The key advantage of CHP over conventional production methods is higher energy efficiency, as electricity and heat are produced simultaneously from a single fuel source [3]. A CHP system operates under storage capacity and output bounds and transactions with external networks to handle imbalances between production and demand [4,5]. As a result, the task is to allocate production across time under inventory and output limits and to govern exchanges with external networks, and the solution must produce feasible decisions rapidly for operational updates [6,7].

In practical CHP operation, planning involves reconciling time-varying demand and production costs profiles with operational limits [8,9]. In many Asian countries, heat demand is higher at night, whereas power demand is typically higher during the day, and the production costs for both are usually lower during daytime than nighttime [10]. In particular, several studies focused on situations where heat and power cannot be produced simultaneously, and only either heat mode or power mode can be selected at a time [11,12]. Weather, seasonal factors, and changes in industrial activity further drive frequent shifts in demand for heat and power which makes it difficult to respond to demand variability [4,13]. Therefore, rapid CHP production planning is essential to track these fluctuations, and the need for speed under constraints makes the problem challenging [14,15].

CHP planning has relied on two main approaches, mathematical programming and rule-based methods [4,16]. Mixed integer programming provides optimality-guarantees when constraints are fully modeled, and time is sufficient where a solid baseline for small or moderate instances [10]. As the number of constraints increases and the planning horizon lengthens, computational effort grows rapidly and repeated solving under changing demand and production costs make real-time operation difficult [14,16]. Rule-based methods avoid heavy computation and deliver transparent fast decisions that keep capacity and inventory feasible in a pre-given setting [17,18]. Rule-based methods’ responses to time varying interactions among demand, production costs, inventory, and startup behavior are weak, and averaging future inputs can miss peaks and spikes, which leads to unnecessary external purchases or forced sales and lowers economic performance [10].

Recent research has actively explored employing machine learning and deep learning methods for CHP operational planning [10,13]. These methods have shown potential for predicting efficient operational strategies by learning complex patterns from historical data. While in the current situation with constraints, predicted values of the model can subtly violate the constraints, leading to an infeasible outcome. Against this background, a prior study that applied deep learning to the heat production planning problem successfully demonstrated the applicability of deep learning for efficient heat production planning by focusing solely on heat production [10]. However, this approach has a limitation as it fails to sufficiently address the characteristics of a CHP system, which is the combined production and linkage problem of heat and power [19,20].

To overcome the limitations of existing research, in this paper, we propose the Hybrid Time series Informed neural Network (HYTIN) to effectively reduce the overall operational cost of a complex CHP system planning problem by learning long- and short-term patterns from the time series information for both heat and power. The long- and short-term time series patterns from the demand and production costs of both heat and power are encoded by using LSTM or CNN. The MIP constraints proposed in a prior study were expanded to obtain high-quality and feasible solutions for joint heat and power planning [10]. Through extensive experiments, HYTIN trained on these solutions was shown to effectively solve unseen production planning problems. Furthermore, an ablation study was conducted to evaluate the four combinations of heat, power, LSTM, and CNN.

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews the related prior studies. The detailed definition of the CHP system operational planning problem and the mathematical modeling of MIP are discussed in Section 3. Section 4 describes the theoretical background and the specific algorithm of the HYTIN proposed in this study. Section 5 verifies the performance of the proposed methodology through simulations and experimental results using real data. Finally, the conclusion of this study and suggestions for future research directions are summarized in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

Hybrid deep learning forecasters improve short- and mid-horizon accuracy across electricity–heat–cooling by combining CNN/LSTM/Attention with decomposition, transfer learning, and multi-task objectives [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Explainable and privacy-preserving variants extend applicability in operational environments through reservoir-computing XAI and federated learning that approaches centralized accuracy while mitigating data-sharing risks [28,29]. Domain-specific models for CHP heating load demonstrate robust, season-long online deployment via strand-based LSTM with careful preprocessing and loss design [30]. Despite these advances, most forecasting studies still stop at continuous load prediction and do not directly yield discrete, constraint-aware dispatch decisions [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Several works couple improved forecasts with optimization to lower costs and emissions, using genetic algorithms, robust formulations, and ensemble selection to translate predictive gains into dispatch or unit commitment benefits [31,32,33,34,35]. Parallel efforts deploy deep reinforcement learning single- and multi-agent to enhance flexibility and cost control in CHP and integrated energy systems, with promising results but persistent challenges in hard-constraint satisfaction, action-space exclusivity, and robustness across seeds and scenarios [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Physics-informed surrogates accelerate inner-loop evaluations by orders of magnitude, enabling near-real-time planning provided the surrogate is well-trained over the relevant operating envelope [46].

Reliability-aware operation has also been explored by several scholars. Specifically, a safe policy learning framework coordinates multi-energy microgrids with green hydrogen while managing congestion and shows how data-driven controllers incorporate operational safety during dispatch [47]. A state-similarity method was proposed to accelerate reliability assessment and quickly provide risk indicators [48].

Prior studies are predominantly simulation-based, emphasize continuous load prediction over discrete dispatch, and frequently rely on ex-post feasibility repair rather than ensuring feasibility at inference. Many DRL approaches omit explicit mutually exclusive action sets for heat versus power and provide limited safety guarantees under hard constraints. Surrogate methods, while fast, are not always integrated with learned dispatch policies to enforce constraints online. Safety-aware learning and reliability screening are often treated as separate modules rather than being enforced within the planner during inference, which leaves gaps in formal constraint satisfaction and real-time risk control.

3. Problem Description

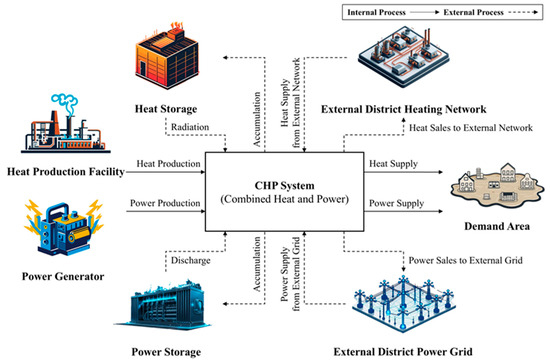

Figure 1 illustrates the overall flow of a CHP system considered in this research. The objective of the CHP system is to minimize total operation cost while maximizing energy supply efficiency by balancing production, storage, supply, and interactions with external networks to meet demand.

Figure 1.

Overview of the CHP system considered in this paper.

The CHP system consists of an internal process and an external process. The internal process produces heat and power and supplies them to the demand area, while the external process connects storage units and external networks. When on site production exceeds demand, the surplus is stored in heat or power storage, and any remaining excess is sold to the district heating network or the power grid. When demand exceeds on site supply, heat or power is released from storage, and any remaining deficit is purchased from the external networks. These storage operations and external transactions add constraints beyond basic production and supply, and they are central to balancing the plan. Because external sales and purchases carry penalty costs, the planning objective is to set production levels and storage actions that meet demand while limiting reliance on external networks.

In order to design the mathematical programming model, the parameters and decision variables are shown in Table 1. While a prior study addressed a mathematical programming problem for heat only, this research expands the scope to include both heat and power [10]. The constraints for our CHP system are particularly more complicated due to a path conflict between the heat and power processes where simultaneous production is not possible.

Table 1.

Notations for mathematical model.

The decision variables in our model include the production volume (), selected production level (), inventory (), and supply to and from external networks (, ), where i ∈ {h, p} for heat and power, at a time t. Additionally, for the heat and power line, a minimum operation time () and a minimum idle time () are given, where a duration of (t, t + − 1) or (t, t + − 1) is enforced when the operation starts or shuts down at time t. While these minimum time constraints apply independently to each unit, the key challenge is that simultaneous production of heat and power is not possible within this specific system. Therefore, we formulated the problem as deciding on a production level (k) at time t, where the production volume is automatically determined once the level is chosen. A typical production facility has minimum and maximum operational capacities. Production decisions are often made by using a set of pre-defined, fixed values between these minimum () and maximum () capacities. We set our production volume at production level k () to be one of the seven discrete levels k ∈ {1, 2, ..., 7}.

When production exceeds demand, excess inventory () is stored. Conversely, when demand surpasses production, inventory is discharged from storage. At the same time, the storage unit has minimum () and maximum () limits. If the system needs to discharge inventory but the storage is already at its minimum level, it requires a supply from external networks (). Conversely, if the system needs to accumulate more inventory but storage is at its maximum level, it must sell the excess energy to external networks (). Both scenarios incur high costs. Values for external exchange costs (, ) and storage costs (), based on the Korea district heating corporation, were addressed by prior work, and each cost is allowed to vary over time [10]. In contrast, production costs () and demand () maintain a real-world setting by fluctuating over time due to factors such as season, fuel source, and other external conditions. Operation costs are calculated using an exchange rate of USD 0.00072 per KRW 1, as of 10:44 AM UTC on 17 July 2025.

The objective function (1) is designed to minimize the total operation cost, which is composed of four distinct cost terms. These terms include production costs, inventory holding costs at the storage facility, and exchange costs to and from external networks. When transactions with external networks occur, we assume the volume of exchange is unlimited, but it incurs high costs. Thus, the mathematical model is structured to allow transactions with external networks only out of necessity.

The inventory balancing constraint (2), a well-known constraint for this type of problem, ensures inventory volume at time t is a function of internal production and external exchanges for both heat and power. Constraints (3) and (4) are related to production capacity. If a facility is operating, its state variable () is set to 1 to satisfy these constraints. Constraint (6) ensures that only one of the k production levels is selected at any given time, while constraint (5) automatically calculates the production volume based on that chosen level. Constraints (8) and (9) enforce minimum operation and idle times. Since the problem is modeled as a MIP, these constraints significantly add complexity to model computing. Furthermore, constraint (7) defines the startup and shutdown states for each facility. Finally, constraints (10) and (11) define the minimum and maximum storage capacity limits. In this model, the state variables , and are binary, while all other variables are continuous, defined as constraints (12) to (14). Constraint (15) defines as the production volume for each of the seven discrete levels. Level k = 1 represents the off state in which production volume is 0. Heat production levels, k = 2, 3, 4, each correspond to production volume ,,. For power, levels k = 5, 6, 7 are, respectively, assigned to production volume ,,.

To train the proposed model, we generated a set of operation scenarios using the MIP model. We chose this approach because real-world operation data is often insufficient for deep learning and contains decisions that are not necessarily optimal for a given problem. Since the MIP model generates high-quality solutions that satisfy all operational constraints within an hour, we utilized the MIP model to generate diverse operational scenarios and used the resulting decision outcomes as the training data for our deep learning model. Consequently, using the MIP decision results to train the deep learning model is expected to produce solutions efficiently, allowing for rapid decision-making regardless of the input provided.

4. Proposed Method

4.1. Training and Planning Framework of HYTIN

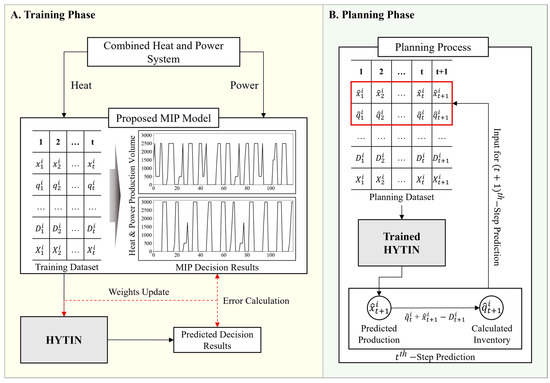

The details of the training and planning framework for HYTIN are presented in Figure 2. The HYTIN model operates in two distinct phases, a training phase and a planning phase. In the training phase, the model learns from the optimized decisions generated by the MIP model. The planning phase is where the trained model is swiftly applied to new scenarios. Through the connection of these two stages, HYTIN can significantly reduce computational time while providing high-quality operational decisions.

Figure 2.

The proposed two-phase planning for HYTIN framework.

We start the training phase by using the proposed MIP model to generate a set of scenarios which are then used to create the training dataset. The dataset for training HYTIN includes the demand () and production costs () at time t, as well as the inventory () and previous heat production volume () at time t − 1. Given an initial inventory () and initial production level (), the MIP begins its decision-making process. Using the CHP mathematical constraints from Section 3, the MIP generates decision results for production volume (). Similarly, HYTIN uses the same demand, production costs, inventory, and production volume information to predict one of the available production levels (), as presented in Section 3. The MIP decision results are mapped to one of s, which become target values for training. The error is then calculated between the HYTIN-predicted production level and this target value. After the training phase, HYTIN saves the best model states based on the training dataset.

In the subsequent planning phase, the trained HYTIN model can make rapid operational decisions for new scenarios. The model takes in real-time information about the new scenario’s demand and production costs at time t, as well as the inventory and production volume from time t − 1, to predict close to the MIP decision results. Unlike the training phase, where actual inventory values were used in the training dataset, here the inventory is calculated and used for the next step according to Equation (20). Similarly, the predicted production level is used to predict the production level for the next step t + 1. The planning phase follows long horizon planning and long-term time series forecasting, where several future steps are predicted ahead of time [10,49]. The model then reuses its own predicted production level and updated inventory as inputs for later steps as the true future states are not available. Under this structure, an early deviation can influence later steps, and the model is designed to account for carry forward in the decision results.

The planning phase also uses the same initial values, and , as the training phase. Where the biggest difference between the two phases is that unlike the training phase, which bases its planning decisions on actual information, the planning phase uses only predicted values recursively. Since the MIP formulation includes minimum and maximum operation time constraints, we apply the same constraints during the planning phase of HYTIN. At each step HYTIN enforces these constraints by excluding any of the seven production levels that would violate Equations (7)–(9) and then choosing among the remaining feasible levels.

This recursive process behaves like an autoregressive sequence, making the planning process a more challenging problem than the training process. The results predicted by HYTIN are used to calculate the values of , , , , , , and using Equations (16)–(22). These variables are then re-inserted into the mathematical constraints to calculate the predicted objective function value.

4.2. Model Architecture of HYTIN

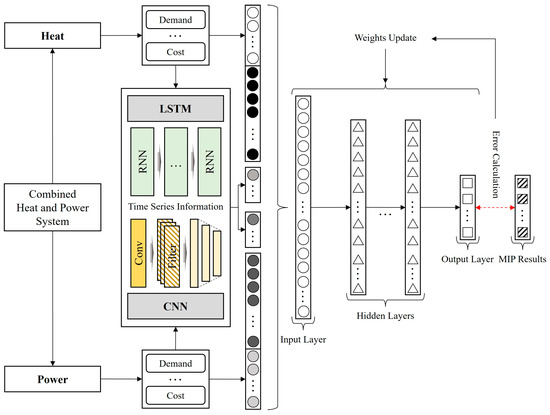

Figure 3 shows the architecture of HYTIN, and the inputs and outputs of the model are defined in Table 2. For the first time in a CHP system, HYTIN takes in time-series information for both heat and power as input. The input layer includes the next 24 h of demand, production costs, and the previous period’s inventory and production volume. We use these four types of information to help HYTIN effectively minimize the operational cost, much like the objective function of the MIP model. For example, the model can decide to produce more during periods of low cost or to not produce at all when inventory is high. To minimize operational costs, it is advantageous to know future demand and production costs during the planning process. Given the inherent periodicity of the data, we assume that 24 h of forecasted demand and production costs are known in advance. A straightforward sliding window approach, where input data shifts one time step at a time, is disadvantageous for long-term forecasting in the planning process because it only considers short-term time series.

Figure 3.

HYTIN model architecture.

Table 2.

Inputs and output of HYTIN.

Therefore, we used LSTM and CNN to encode both long- and short-term time series patterns for heat and power. LSTM is particularly effective at remembering long-term time series patterns and is skilled at identifying repetitive patterns with relatively low fluctuation. On the other hand, CNNs have the unique ability to extract spatial features from time series data, even with large fluctuations. This allows them to identify both small and large patterns in the short term. By adding the results of this pattern analysis for heat and power input data to the input layer, the neural network can better learn the time series information. Subsequently, the model selects one of the pre-fixed production levels through its hidden and output layers. The resulting output is then compared to the existing MIP decision results to perform a weight update.

5. Computational Experiments

5.1. Datasets

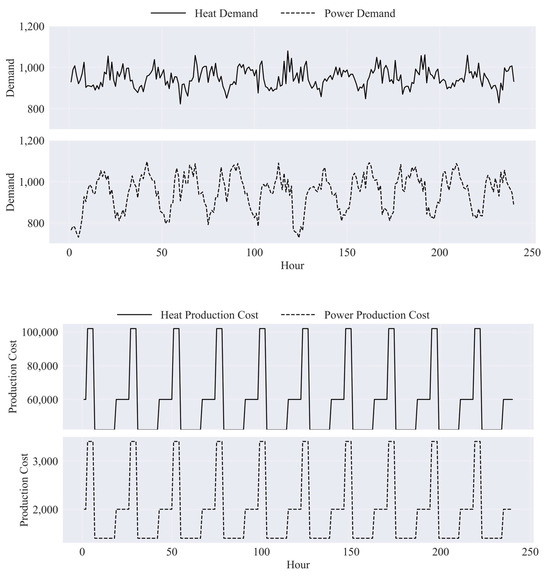

Figure 4 presents 240 h samples from recorded demand and production cost series in South Korea. The three-year record indicates that each heat and power demand has similar averages while power varies more. Production costs follow Korean day–night pricing rules, although the magnitudes differ; both series follow the same day–night structure, yielding aligned patterns [10]. Most patterns are opposite across the two products, yet overlap occurs at several points, which makes complicated switching decisions. For example, when production cost is low and demand is high, the production level must be high for the operation cost to be measured as low. Consequently, the parts considered important by the data are decided through the decision process.

Figure 4.

Sample data on CHP demand and production costs.

To enlarge the training datasets, we simulate additional demand sequences with Gaussian noise [50,51]. The mean and standard deviation are estimated from historical data, and simulated demand is drawn as with integer rounding. On the other hand, production cost values are taken directly from historical data. This produced 1,800,000 h of operational time series which were grouped into units of 120 h. The 120 h window matches a common operating cycle in which weekend demand is served from storage, which explains the inventory bounds used in planning. We split the pool into 80% for training and 20% for validation.

We partitioned the test pool into ten datasets. Each dataset contains ten independent planning cycles of 120 h. The test pool contains 12,000 h, which corresponds to one hundred planning cycle scenarios. Scenarios are drawn to represent all seasons and to keep weekday and weekend patterns in balance. All datasets share the same limits and cost coefficients to ensure a common operational setting.

5.2. Experiment Settings

As explained in Section 4.1, we train HYTIN by using MIP decision results as to guide planning in similar scenarios. The MIP model was optimized using the Gurobi solver on a computer equipped with 64 GB of memory and 24-core CPUs.

Table 3 shows the total operation cost results by varying the time limit for the MIP solver across ten datasets. Bold indicates the best results for each dataset, with the lowest cost. The table represents total operation cost for runs capped at 100 s, 300 s, 3600 s, and 7200 s. We set a maximum running time of MIP to 7200 s, due to the computing resources. Relative to 300 s, the average change is +0.11% at 100 s, −0.06% at 3600 s, and −0.07% at 7200 s. Since the practitioners should quickly make planning decisions to deal with the variations in demand and production costs, the computation time limit for the MIP solver is required to be less than a few minutes. Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, extending the run to two hours brings little additional cost reduction. Therefore, to effectively create as many production plans for training HYTIN as possible within a limited time, we set the MIP time limit to 300 s. This choice provides the best balance between decision quality and the computational speed needed to generate a large training dataset.

Table 3.

Comparison of each maximum runtime for the MIP.

To ensure the effective performance of HYTIN, we determined the final parameters through extensive experimentation. Following prior research, the depth of the fully connected hidden layers was set to five, with sizes of 1024, 512, 128, 64, and 32. The LSTM uses two layers, and the CNN uses 1-D convolution to finally embed the time series information into a 128-dimensional hidden dimension. The learning rate was set to 0.001, and early stopping was implemented to prevent overfitting. We used ReLU as an activation function and Adam as the optimizer. We used cross-entropy as the loss function and applied SoftMax to the final output, as this is a production level selection problem.

We compare HYTIN with DHPP and with the MIP solver [16]. As MIP decision results are not necessarily going to be optimal due to the time limitation, the predictions by using DHPP or HYTIN are possibly going to yield a lower cost than the MIP decision results. Even though HYTIN does not match every production level, decisions that improve inventory management are possible to reduce external transactions and lower operation costs.

Our primary objective is to minimize total operation cost, and our secondary objective is to classify production levels with accurate on-off decisions. We report four metrics aligned with this goal. First, the total operation cost is the sum over the horizon of production cost, inventory holding, and external transactions, where purchases add cost and sales reduce cost. Second, accuracy measures how similar the predicted production level () and production levels () from the MIP decision results are at each time step. For a horizon of length T, accuracy is defined in Equation (23):

where 1{⋅} refers to the indicator that equals one when the statement is true and zero otherwise.

Third, HP-Off accuracy checks whether the predicted production level belongs to the same group as the true level when levels are grouped into Off, Heat, and Power. Let the set of production levels be U = {1,…,k}. Partition U into three disjoint subsets O for Off, H for heat, and P for power with O ∪ H ∪ P = U, O ∩ H = ⌀, O ∩ P = ⌀ and H ∩ P = ⌀.

While Equation (24) defines the grouping map f, for a horizon of length T, HP-Off accuracy is calculated as follows:

Equation (25) provides the metric which gives credit when prediction and truth fall in the same group and averages this agreement over the horizon. It depends only on group membership, so it remains valid when the number of heat or power levels or their identifiers change. In our experiments one concrete instance is O = {1}, H = {2,3,4}, and P = {5,6,7}.

Lastly, On-Off accuracy is a binary measure that checks production versus idle, Equation (26). For this metric we use a binary version of the grouping map g. We let g(u) = 0 for state on with u ∈ O, and otherwise g(u) = 1 for state off with u ∈ H ∪ P.

5.3. Experiment Results

Table 4 and Table 5 present the comparative results across ten datasets and the improvement ratios (IR) of HYTIN over the baselines. Boldface marks the best value in each column for each part, the lowest total cost and the highest accuracy measures. The average total operation cost with HYTIN is 9,760,775 USD, while MIP records 10,184,265 USD and DHPP records 10,993,122 USD. The corresponding IR are 4.16% relative to MIP and 11.21% relative to DHPP. HYTIN achieves the lowest cost in most datasets and remains close in the remaining cases, which indicates stable gains rather than isolated wins. For runtime, planning all 100 sets takes 30,000 s with MIP, whereas DHPP and HYTIN are complete in 16 s.

Table 4.

Total cost comparison for each model.

Table 5.

Comparison of accuracy metrics for DHPP and HYTIN.

In Table 4, the percentage shown next to the MIP total operation cost is the average MIP gap across sets under a 300 s time limit. The MIP gap is the relative difference, in percentage, between the solver’s best incumbent solution and the best bound (theoretically lower bound). The average gap equals 31.02%, indicating the mean cost obtained within the allotted time is not certified optimal and that solutions up to 31.02% lower may exist. For example, in Dataset 5 the MIP gap is 8.26%, and HYTIN does not improve the MIP schedule. In contrast, Dataset 10 shows a 47.93% gap, which indicates substantial potential for improvement, and HYTIN achieves a lower total cost.

Accuracy yielded by HYTIN was 80.99% on average, while that of DHPP was 75.57%. Although accuracy is not the objective of the production planning problem considered in this paper, higher accuracy implies that HYTIN reproduces MIP solver patterns more closely while still improving economics. HYTIN lifts HP-Off accuracy from 69.88% to 87.40%, which is an increase of 20.05% in relative terms. HYTIN also raises On-Off accuracy from 90.38% to 95.44%, which is an increase of 5.28% relatively. These improvements align with the observed cost reductions, indicating that HYTIN learns when to keep a product idle, when to produce, and when to transition, which reduces unnecessary purchases and forced sales while satisfying operational limits.

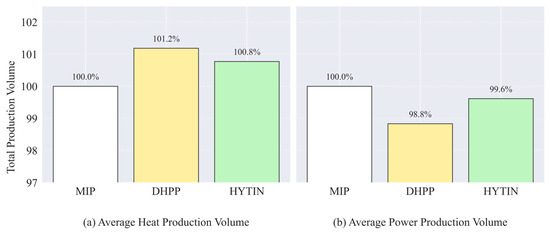

Figure 5 shows that HYTIN stays closer to the MIP totals for both products, which indicates a more balanced mix across the horizon. For (a), the average heat production volume, DHPP produces 101.2% on average and HYTIN produces 100.8%. For (b), the average power production volume, DHPP produces 98.8% and HYTIN produces 99.6%. In the absolute unit gap from MIP, DHPP records about 135,000 for heat and 132,500 for power, while HYTIN records about 88,000 for heat and 43,750 for power.

Figure 5.

Average heat and power production volume for each model.

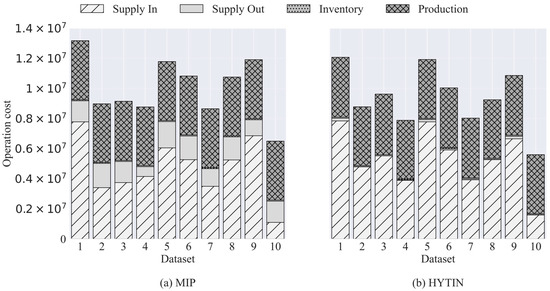

Figure 6 compares the composition of operation cost by dataset for (a) MIP and (b) HYTIN where HYTIN lowers total operation cost mainly by reducing supply-out costs. HYTIN shows more supply-in in several datasets, yet total external transactions are lower because supply-out is smaller, especially in datasets four and ten. As Figure 5 shows, production volumes remain close to the MIP baseline, so production costs are similar. The operation cost advantage, therefore, comes mainly from fewer sales to external networks rather than from changes in production, which is consistent with the aim of limiting external transactions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of cost components for MIP and HYTIN.

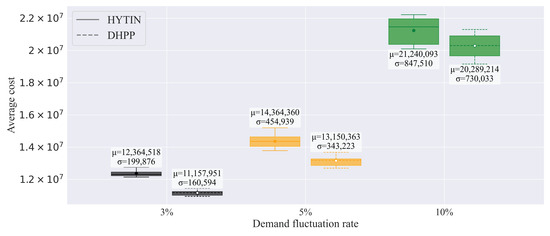

We further conducted an uncertainty analysis by planning the existing known 24 h demand while assuming the real demand differed by 3%, 5%, and 10%. For each level the actual demand was randomly generated within the ranges [0.97·, 1.03·], [0.95·, 1.05·], and [0.90·, 1.10·]. As shown in Figure 7, HYTIN yields lower total operation cost than the DHPP baseline across all cases. Under 3%, 5%, and 10% fluctuation, mean operation cost over 10 repetitions, and relative improvements for HYTIN are 9.76%, 8.45%, and 4.47%. Standard deviations are also lower for HYTIN at every level, indicating more robust planning under demand mismatch.

Figure 7.

Boxplots for DHPP and HYTIN average operation cost under 3%, 5%, and 10% demand differences with ten-run mean and standard deviation.

5.4. Ablation Study

We run an ablation study to identify the most effective encoder pairing for heat and for power. Four variants are tested within HYTIN. L-C uses LSTM for heat and CNN for power. L-L and C-C apply the same encoder to both products. C-L swaps the assignment and encodes heat with CNN and power with LSTM. This study examines whether a sequence-oriented encoder for heat and a pattern encoder for power yields better planning under our constraints.

In Table 6 and Table 7, boldface marks the best value in each column for each dataset, and in the average row it marks the best overall average. Table 6 reports the total operation cost for the four variants according to the datasets. The L-C configuration yields the lowest average cost at 9,710,076 USD. It achieves the best or near best cost in most datasets, while L-L and C-L are consistently higher and C-C is competitive only in a few cases. These results indicate that combining a sequence-oriented encoder for heat with a local pattern encoder for power produces decisions that reduce purchases from external networks and avoid forced sales, which lowers total cost.

Table 6.

Total operation cost comparison across LSTM and CNN configurations.

Table 7.

HP-Off and On-Off accuracy under LSTM and CNN variants.

Table 7 summarizes HP-Off accuracy and On-Off accuracy. C-C attains the highest average HP-Off accuracy at 87.69%, while L-C is close at 87.40% and ahead of L-L and C-L. For On-Off accuracy L-C is the best at 95.44%, followed by L-L at 95.07%, C-C at 95.33%, and C-L at 95.10%. In practice the higher On-Off accuracy of L-C translates into better control of production versus idle states, fewer unnecessary startups, and smoother inventory use, which aligns with the cost advantage observed in Table 6. Although C-C has a slight edge in HP-Off accuracy, the overall operation cost with C-C is higher than with L-C, so we adopt L-C as the default.

Based on the results, it can be said that a recurrent encoder captures extended temporal context and improves the timing of heat production and storage actions. Furthermore, a one-dimensional convolution captures sharper spikes and local peak patterns effectively. The L-C pairing therefore aligns encoder bias with the characteristics of each product. The result is higher On-Off accuracy, competitive HP-Off accuracy, and the lowest total operation cost among the tested variants.

6. Conclusions

This study addressed the production planning problem of the CHP system while not allowing simultaneous production of heat and power. We proposed an HYTIN that aims to decide feasible production levels given demand and production cost profiles with inventory states. To achieve this, HYTIN was trained with the production plans generated by an MIP solver, and then it quickly solved an unseen production planning problem to accommodate the frequent variations in demand and production costs.

Experiments show that HYTIN lowers operation cost relative to prior baselines and improves decision quality. It attains higher alignment with the MIP solver and records higher HP-Off and On-Off accuracy. Cost breakdowns indicate fewer external purchases and fewer forced sales, while average heat and power volumes remain close to the MIP decision results. The ablation study supports the LSTM for heat and CNN for power pairing, which matches long horizon thermal dynamics for heat and short-term variability for power. We cap the MIP solver at three hundred seconds to match real operational turnaround, and results with longer limits show little additional benefit, which supports this choice.

Yet, the proposed method relies on specific forecast inputs and a single MIP solver configuration, while assuming a single plant with non-parallel production paths and fixed production level. This poses a limitation since employing the approach to CHP systems with different structures or cost settings may require retraining. In future works, discrete production levels will be replaced by continuous outputs by employing regression-based models. Furthermore, we plan to extend the proposed model to handle multi-level plants and to incorporate simultaneous co-production of heat and power by utilizing graph-based networks, thereby improving its applicability to more general industrial settings. In addition, future work considers stochastic cost and demand so that planning decisions are optimized under time varying price and load uncertainty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.A., I.-B.P. and K.K.; Methodology: J.A.; Software and Validation: J.A. and S.L.; Formal Analysis and Investigation: J.A., S.L. and I.-B.P. Data Curation: J.A., S.L. and I.-B.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: J.A., I.-B.P. and K.K.; Writing—Review and Editing: I.-B.P. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2025-24523405) and supported in part by the Dongguk University Research Fund of 2025.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets available on request from the authors. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schiefelbein, J.; Tesfaegzi, J.; Streblow, R.; Müller, D. Design of an Optimization Algorithm for the Distribution of Thermal Energy Systems and Local Heating Networks within a City District. In Proceedings of the ECOS 2015, Pau, France, 29 June–3 July 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Zou, Y.; Soltanov, N. A Multilevel Optimization Approach for Daily Scheduling of Combined Heat and Power Units with Integrated Electrical and Thermal Storage. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordehi, A.R. Scheduling Heat and Power Microgrids with Storage Systems, Photovoltaic, Wind, Geothermal Power Units and Solar Heaters. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.Y.; Chen, Y. A Two-Stage Robust Operation Approach for Combined Cooling, Heat and Power Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Beijing, China, 26–28 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, M.; Neumaier, L.; Remmen, P.; Müller, D. Temperature Control in 5th Generation District Heating and Cooling Networks: An MILP-Based Operation Optimization. Appl. Energy 2021, 288, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, T.; Ritter, A.; Onder, C.H. The Faster the Better? Optimal Warm-Up Strategies for a Micro Combined Heat and Power Plant. Energies 2023, 16, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.K.; Terziev, A.K.; Beloev, H.I.; Nikolaev, I.; Georgiev, A.G. Comparative Analysis of the Energy Efficiency of Different Types Co-Generators at Large-Scale CHPs. Energy 2021, 221, 119755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, A.E.; Ghanavati, F.; Ahmarinejad, A. Determining the Optimal Operating Point of CHP Units with Nonconvex Characteristics in the Context of Combined Heat and Power Scheduling Problem. IETE J. Res. 2022, 68, 2609–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Y.W.; Alpcan, T.; Lee, V.C.S.; Lo, A.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Demand Response Architectures and Load Management Algorithms for Energy-Efficient Power Grids: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2012 Seventh International Conference on Knowledge, Information and Creativity Support Systems (KICSS), Melbourne, Australia, 8–10 November 2012; IEEE: Melbourne, Australia, 2012; pp. 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Yoon, S.M.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Song, S.H. Applying Deep Learning to the Heat Production Planning Problem in a District Heating System. Energies 2020, 13, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiron, J.; Montañés, R.M.; Normann, F.; Johnsson, F. Combined Heat and Power Operational Modes for Increased Product Flexibility in a Waste Incineration Plant. Energy 2020, 202, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiron, J.; Montañés, R.M.; Normann, F.; Johnsson, F. Flexible Operation of a Combined Cycle Cogeneration Plant—A Techno-Economic Assessment. Appl. Energy 2020, 278, 115630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benam, M.R.; Madani, S.S.; Alavi, S.M.; Ehsan, M. Optimal Configuration of the CHP System Using Stochastic Programming. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2015, 30, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, N.; Yang, N.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L. A Review: Machine Learning for Combinatorial Optimization Problems in Energy Areas. Algorithms 2022, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, A.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, M. Model Predictive Control Based Real-Time Scheduling for Balancing Multiple Uncertainties in Integrated Energy System with Power-to-X. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 130, 107015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanabadi, R.; Sharifzadeh, H. Solving Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch Using a Mixed Integer Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Long, S.; Marjanovic, O.; Parisio, A. Model Predictive Control of Smart Districts with Fifth Generation Heating and Cooling Networks. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 2659–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, X.; Yu, D.; Dong, M.; Liu, H. Rule-Based Coordinated Control of Domestic Combined Micro-CHP and Energy Storage System for Optimal Daily Cost. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ni, W. Heat and Power Load Dispatching Considering Energy Storage of District Heating System and Electric Boilers. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2018, 6, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, H.; Yan, J. Heat–Power Decoupling Technologies for Coal-Fired CHP Plants: Operation Flexibility and Thermodynamic Performance. Energy 2019, 188, 116074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, J.; Peng, M.; Cui, X. A CNN-LSTM-Attention (CLA) Hybrid Model with PID-Based Search Algorithm (PSA) for Heat Load Forecasting in District Heating System. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Duan, P.; Cao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, B.; Xue, Q.; Feng, M. A Multi-Energy Load Forecasting Method Based on Complementary Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition and Composite Evaluation Factor Reconstruction. Appl. Energy 2024, 365, 123283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, G.; Wang, K.; Han, B. A Multi-Energy Load Forecasting Method Based on Parallel Architecture CNN-GRU and Transfer Learning for Data-Deficient Integrated Energy Systems. Energy 2022, 259, 124967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Shouxiang, W.; Qianyu, Z.; Shaomin, W.; Liwei, F. A Multi-Energy Load Prediction Model Based on Deep Multi-Task Learning and Ensemble Approach for Regional Integrated Energy Systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Systems. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 126, 106583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Mu, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, C. A Novel Short-Term Multi-Energy Load Forecasting Method for Integrated Energy System Based on Feature Separation–Fusion Technology and Improved CNN. Appl. Energy 2023, 351, 121823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Mei, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Nakanishi, Y. Bi-LSTM Multi-Task Learning-Based Combined Load Forecasting Considering the Loads Coupling Relationship for Multi-Energy System. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3481–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, J.; Luo, F.; Qiu, X. Collaborative Forecasting of Multiple Energy Loads in Integrated Energy Systems Based on Feature Extraction and Deep Learning. Energies 2025, 18, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.; Ortiz, A.; Cortés, P.J.; Canals, V. Explainable District Heating Load Forecasting by Means of a Reservoir Computing Deep Learning Architecture. Energy 2025, 318, 134641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhu, S.; Bai, X. Federated Learning-Based Multi-Energy Load Forecasting Method Using CNN-Attention-LSTM Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, B.; Lu, K.; Wang, R. Heating Load Forecasting for Combined Heat and Power Plants via Strand-Based LSTM. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 33360–33369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, P.; Golkar, M.A. A Dual-Stage Optimization Model for Multi-Microgrid Energy Management: Balancing Economic, Environmental and Social Objectives. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2025, 19, e70146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, R.; Si, F. Operation Optimization for a CHP System Using an Integrated Approach of ANN and Simulation Database. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 266, 125771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghione, G.; Randazzo, V.; Pasero, E.; Badami, M. Optimal Cogeneration Scheduling: A Comparison of Genetic and POMDP-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning Approaches. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 128562–128581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Agbozo, R.S.K.; Zhao, X. Optimal Load Distribution of CHP Based on Combined Deep Learning and Genetic Algorithm. Energies 2022, 15, 7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, F.; Ge, J.; Yin, Q.; Wang, R. Research on Integrated Decision Making of Multiple Load Combination Forecasting for Integrated Energy System. Energy 2024, 311, 133390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, C.; Pan, C.; Zhang, C.; Ren, H.; Ghias, A.M. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Control Strategy to Improve the Operating Flexibility of CHP Units under Variable Load Conditions. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 49, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, Z.; He, Y. A Deep Neural Network-Based Optimal Scheduling Decision-Making Method for Microgrids. Energies 2023, 16, 7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Hu, Z.; Gu, W.; Jiang, M.; Chen, M.; Hong, Q.; Booth, C. Combined Heat and Power System Intelligent Economic Dispatch: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chang, W.; Yang, Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Hierarchical Energy Management for Virtual Power Plant with Aggregated Multiple Heterogeneous Microgrids. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Q.; Yin, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, C. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Real-Time Energy Management for an Integrated Electric–Thermal Energy System. Sustainability 2025, 17, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Cui, Y.; Yan, G.; Huang, Y.; Fan, Z. Distributed Energy Management of Multi-Area Integrated Energy System Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yang, S.; Sun, S.; Yu, P.; Xing, J. Energy Management for Integrated Energy System Based on Coordinated Optimization of Electric–Thermal Multi-Energy Retention and Reinforcement Learning. Processes 2025, 13, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Shahidehpour, M. Enhancing Cyber-Resilience in Integrated Energy System Scheduling with Demand Response Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Applied. Energy 2025, 379, 124831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Gong, Y.; Liang, X.; Chung, C.Y.; Noble, B.; Poelzer, G. Safe Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Real-Time Multi-Energy Management in Combined Heat and Power Microgrids. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 193581–193593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Ran, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Scalable Energy Management Approach of Residential Hybrid Energy System Using Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Applied. Energy 2024, 367, 123414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, T.S.; Flores, R.J.; Brouwer, J. Neural-Network-Based Optimization for Economic Dispatch of CHP Systems. Appl. Energy 2020, 265, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Xia, Y.; Yan, Z.; Gao, H.; Qiu, D.; Guerrero, J.M.; Li, Z. Coordinated Operation of Multi-Energy Microgrids Considering Green Hydrogen and Congestion Management via a Safe Policy Learning Approach. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Hou, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, R.; Jia, H. A State-similarity-based Fast Reliability Assessment for Power Systems with Variations of Generation and Load. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, D.; Park, J.; Park, I.-B. TSDNet: A two-stage decomposition-based hybrid deep neural network for long-term time series forecasting. Intell. Data Anal. Int. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelos, S.; Pudjianto, D.; Zhang, T.; Strbac, G. Energy Hub Operation Under Uncertainty: Monte Carlo Risk Assessment Using Gaussian and KDE-Based Data. Energies 2025, 18, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dreven, J.; Cheddad, A.; Alawadi, S.; Ghazi, A.N.; Koussa, J.A.; Vanhoudt, D. From data scarcity to diagnostic precision: A novel data augmentation and fault diagnosis framework for district heating substations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 151, 110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).