Abstract

Hand-arm vibration (HAV), which potentially causes vibration white finger (VWF), and occupational noise are serious issues in the agricultural and forestry industries. Generally, agricultural workers operate as single-family/small businesses and thus are exempted from Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations/laws for noise and HAV otherwise applicable to other industries in general. The agricultural/forestry sectors are at increased risk as working hours are longer than a typical 8-h work shift putting them at greater risk of hearing loss. The study was conducted to assess the possible association between hearing sensitivity on combined exposure to noise and hand-arm vibration. A systematic literature review was conducted on exposure to noise and HAV in the agricultural/forestry sector and the resulting impacts on hearing. The peer-reviewed articles in English were searched with 14 search words in three databases of PubMed, Ergo Abstracts, and Web of Science without any filter for the year for fully available article text. The database literature search resulted in 72 articles. Forty-seven (47) articles met the search criteria based on the title. Abstracts were then reviewed for any relationship between hearing loss and hand-arm vibration/Raynaud’s phenomenon/VWF. This left 18 articles. It was found that most agricultural workers and chainsaw workers are exposed to noise and VWF. Hearing is impacted by both noise and aging. The workers exposed to HAV and noise had greater hearing loss than non-exposed workers, possibly due to the additive effect on temporary threshold shift (TTS). It was found that VWF might be associated with vasospasm in the cochlea through autonomous vascular reflexes, digital arteries narrowing, vasoconstriction in the inner ear by noise, ischemic damage to the hair cells and increased oxygen demand, which significantly affects the correlation between VWF and hearing loss.

1. Introduction

Noise-induced hearing loss is a serious problem among United States workers affecting nearly 22 million people every year [1]. Virtually everyone is exposed to noise to some degree [2]. Health effects related to noise can be direct (auditory effects) and indirect (non-auditory) depending on the duration of exposure to sound signals and their intensity. Besides direct health effects leading to permanent effects such as hearing loss and tinnitus (ringing, buzzing etc., in the ears). The indirect health effects, such as sleep disorders with awakenings [3], learning impairment [4], hypertension, ischemic heart disease [5], diastolic blood pressure [6], reduction of working performance [7,8] and annoyance [9,10] are extremely important to consider. The scientific community is moving toward the prevention of these health effects [11].

Farmers and forestry workers are prone to hearing loss due to exposure to high noise levels for long work schedules because of seasonal job demands in the agricultural and forestry sectors. Approximately 37% of the workers suffer from hazardous noise levels, as illustrated by Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting Statistics (AFFH) [12]. Although farmers and forestry workers acknowledge they are exposed to hazardous noise levels, 27% reported not wearing hearing protection [12]. Audiograms of AFFH workers analyzed in the Surveillance Project study showed a significant decrease in hearing loss prevalence from 1981 (33%) to 2005 (13%), followed by an increase of 14% from 2006 to 2010. Overall, there was a significant decrease in incidence (11% to 6%) from 1986–2010. Even after these decreases in prevalence and incidence, it was stated that AFFH had the third highest hearing loss prevalence after Mining and the Healthcare and Social Assistance sectors [13].

Workers in the agricultural and forestry sectors are exposed to noise and vibration while using various kinds of handheld tools. The exposure to vibrations may cause Raynaud’s phenomenon, which occurs when there is a reduction of blood flow to fingers which results in a reduced tactile sense. The Vibration White Finger (VWF) is a secondary and severe form of Raynaud’s phenomenon, which results in cold blanching of fingers. Working frequently for long hours and exposure to vibrations simultaneously with noise increase the susceptibility to hearing loss [14,15,16]. The study conducted by Pykko et al., 1989 [17] discovered that forestry workers exposed to vibrations with noise had more severe hearing loss compared to other workers without vibration exposure. The objective of the study was to assess the combined synergistic effect of exposure to noise and hand-arm vibration on the hearing of forestry and agricultural sector workers.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Criteria

First, a systematic literature review protocol was developed. The search was carried out in three different databases (a) Web of Science, (b) PubMed, and (c) Ergo abstracts. Different combinations of words were chosen using ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ operators to identify articles relevant to the study. Finally, a string of words that resulted in the maximum number of relevant articles in searched databases for the purpose of the study was: ((Hand Arm Vibration OR Hand Vibration OR Arm Vibration OR Raynaud’s OR White Finger) AND Hearing AND (Agricultur* OR cultivat* OR lumberjack OR Chain Saw OR Farm* OR Forest* OR Sawyers OR Harvest*)).

2.2. Screening

An inclusion and exclusion strategy was defined. Inclusion criteria were: (a) peer-reviewed articles, (b) full text available, and (c) written in English. The exclusion criteria were: (a) articles undergoing the publishing process, (b) review papers, and (c) papers not written in English. The search was conducted without any filter for publication year. The items of interest in the title were exposure to hand-arm vibration, Raynaud’s phenomenon, VWF, and the resulting outcome of hearing loss in the agriculture sector, lumberjacks, chainsaw operators, and forestry workers. The articles that did not meet the above requirement in the title were not included in the study. After screening articles for titles, the abstracts were reviewed. The abstracts that did not present the relationship between hearing loss and hand arm vibration/Raynaud’s phenomenon/VWF were excluded. Finally, the articles meeting requirements were reviewed in full text and included in this study.

3. Results

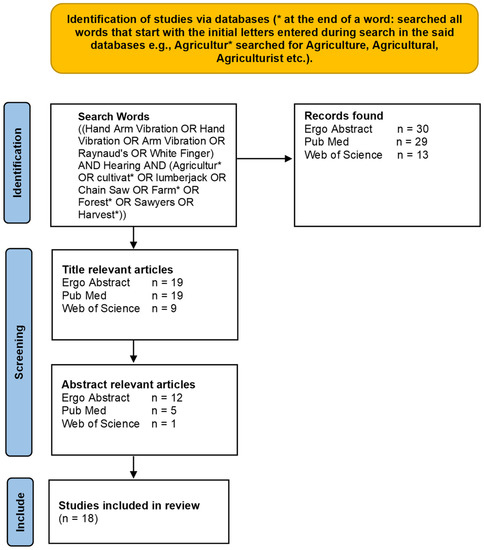

The literature search was conducted up to a publication date of November 2022 in databases of Ergo Abstracts, PubMed and Web of Science using the library’s subscription of the authors’ university. It resulted in 72 articles after removing duplicates and non-English language, as presented in Figure 1. Based on the initial search criterion of title relevance, 47 articles met the condition. Finally, article abstracts that demonstrated a relationship between hearing loss and hand-arm vibration/Raynaud’s phenomenon/vibration white finger were reviewed. This strategy reduced the number of articles to 18, which were thoroughly reviewed and included in this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article search results.

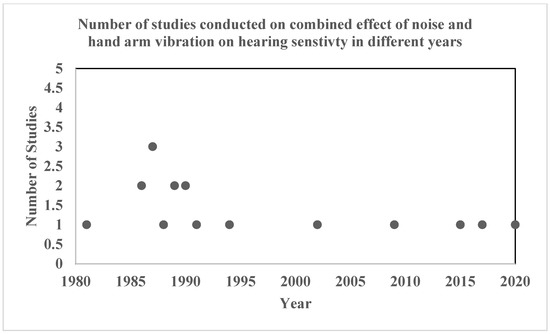

Figure 2 represents the number of studies published on the combined effect of noise and hand-arm vibration on hearing sensitivity at different points in time. The figure represents that 1987 had the highest number of studies conducted (three studies), followed by two studies in 1986, 1989, and 1990, and finally, one study in each of the other years. It can be said that very few researchers have studied the relationship/impact of the combined exposure of noise + hand-arm vibration on hearing sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Number of studies conducted by year.

Table 1 shows most of the majority of studies (eight) were conducted in Japan, followed by Finland (five studies), and one study each in the remaining countries: USA, Italy, Canada, Lithuania, and Romania. It also shows the aim of each study, study type, number of subjects, subject age, inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with performance measures. Table 2 lists the standards used in each study, and Table 3 shows brief details of the findings.

Table 1.

Brief details of studies conducted by different researchers (NIPTS—Noise Induced Permanent Threshold Shift, SNHL—Sensory neural Hearing Loss, VWF—Vibration White Finger, NM—Not Mentioned, h-hours, WBV—Whole Body Vibration, NIHL—Noise Induced Hearing Loss, HAV—Hand Arm Vibration, ms−2—meter per second square, Leq—equivalent continuous sound level and dBA—decibels A scale adjusted to human hearing).

Table 2.

Standards followed in each study (NM—Not Mentioned, WBV—Whole Body Vibration, HAV—Hand Arm Vibration).

Table 3.

Brief Summary of Study Findings (HAV—Hand Arm Vibration, WBV—Whole Body Vibration, NIPTS—Noise Induced Permanent Threshold shift, HL—Hearing Loss, TTS—Temporary Threshold Shift, VWF—Vibration White Finger, SNHL—Sensory Neural Hearing loss, ms−2—meter per second square, kHz—kilohertz, °C—degree Celsius, ASV—Average Body Sway Velocity, NM—Not Mentioned, DBP—Diastolic Blood Pressure, mgm−3—milligram per cubic meter, OSHA—Occupational Safety and Health Administration, NIOSH—National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and TWA—Time Weighted Average).

4. Discussion

4.1. Association between Hand Arm Vibration (HAV) and Hearing Loss

Nine studies were found that established the relationship between HAV and hearing loss among forestry workers. The first study was conducted by Pyykko et al., 1981 [15]. The aim of the study was to determine the role of hand-arm vibration in the etiology of hearing loss in lumberjacks. A longitudinal study was conducted on Finnish forestry workers. Only the workers who had used chainsaws for a minimum of 500 hours per year were included in the study. It was found that hearing loss increased with age along with the duration of noise exposure and hearing protection use. The HAV-exposed subjects had significant hearing loss compared to non-HAV-exposed subjects with similar noise exposure.

The second study analyzed risk factors for sensory neural hearing loss during combined exposure to noise and vibration by Pyykko, Pekkarnine, and Starck in 1987 (Pyykkö, Pekkarinen, and Starck 1987). The VWF explained a 5% variation of SNHL in forestry workers at 4000 Hz. There was an interesting observation that the combination of noise and hand-arm vibration was not more hazardous to hearing than exposure to equivalent energy of noise alone. Iki et al., 1989 studied hearing of forestry workers affected by VWF with 5-year follow-up [23]. The noise-induced hearing loss was tested at 2, 4, and 8 kHz. The older subjects (>50 years) had greater hearing loss for tested frequencies compared to younger subjects (<50 years). The hearing loss was more severe in men with VWF regardless of age, hearing health, and noise exposure. The threshold shift at 8 kHz was similar in all age groups. However, hearing at 4 kHz was influenced by the interaction of noise exposure and VWF. Therefore, it was concluded that subjects exposed to noise and VWF were more vulnerable to hearing loss. The studies conducted by Iki et al. 1986; Iki 1994 and Pyykko et al., 1981 [15,18,27] discovered a similar association between VWF and hearing loss.

Pyykko et al., 1989 [17] studied risk factors in the genesis of sensory neural hearing loss. They found that aging was the major factor for sensory neural hearing loss and explained 25% of the variance in sensory neural hearing loss, followed by noise exposure which explained 9% of the variance of sensory neural hearing loss.

Iki et al., 1990 [24] found that age was significant for every hearing level tested (500, 1000, 2000, 4000, and 8000 Hz). Chainsaw operation hours were significant for all hearing levels tested except for 8 kHz. The VWF had a significant correlation with hearing at 4 kHz. The hearing was found to be affected by both age and noise. Also, VWF was significantly correlated with hearing independent of age and noise exposure. The hearing of subjects without VWF, with VWF in both hands and VWF in one hand, were tested. No significant differences were observed in subjects with VWF in one hand and in both hands. At 4 kHz, in the subjects with VWF in one hand, significant differences were observed on the ipsilateral side of the hand with VWF, which was greater than the contralateral side. Laterality in hearing could be a problem in subjects with VWF in one hand, possibly due to the posture of the operator such that one ear was nearer to the noisy tool. The laterality of hearing loss might be due to different noise susceptibilities of both left and right ears on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the hand with VWF.

Murata, Araki and Aono, 1990 [25] discovered that chainsaw and brush saw operators both had moderate hearing loss for all frequencies tested. However, hearing was worse in chainsaw operators at 4 and 8 kHz. Turcot et al., 2015 [30] conducted research on noise-induced hearing loss and combined noise and vibration exposure. The researchers found that significant differences existed in hearing loss between forestry and mining workers with VWF and without VWF. There was a gradual decline in hearing in VWF subjects. The hearing was related to the duration of noise exposure. Working in environments with >90 dBA significantly contributed to the differential hearing deficit (DHD).

Iftime, Dumitrascu and Ciobanu, 2020 [32] conducted a study on chainsaw operators’ exposure to occupational risk factors and incidence of professional diseases specific to the forestry field. Exposure to high levels of noise, HAV, humidity and particulates might cause bilateral hearing loss and Raynaud’s syndrome (observed in 12% of workers with 26–35 years of forestry work experience). The diseases are closely related to age, work experience years in the current job, noise exposure, vibration, particulates and environment.

4.2. Possible Reasons for Hearing Loss Caused by Hand Arm Vibration (HAV)

The four studies conducted by Pyykko et al., 1981 [15], Pyykko et al., 1986 [19], Miyakita et al., 1987 [11] and Pyykko et al., 1989 [8] discussed the possible mechanism of hearing loss caused by combined exposure to noise and hand-arm vibration. Pyykko et al., 1981 [15] suggested vasoconstriction of the cochlear vessels triggered by the hand-arm vibration as one potential reason. If an individual with VWF is more susceptible to the ill effects of noise, then hearing might deteriorate further with digital vasospasms (vascular derangement with the sympathetic flow).

Another reason was suggested by Pyykko, Starck and Pekkarinen, 1986 [19] and Pyykko et al., 1989 [17]. The authors found that the simultaneous exposure to noise and vibration caused high energy demands. It caused the sympathetic nervous system to disturb the local compensatory changes in capillary beds by increasing circulation of the inner ear. This mechanism was responsible for hearing loss. This fact was supported by Miyakita et al., 1987 [20], who said that there was a relationship between hearing loss and peripheral circulation disorder due to the participation of the sympathetic nervous system found in some earlier animal studies. However, no relationship was established between hand-arm vibration exposure and cochlear microcirculation. Miyakita et al., 1987 stated that it was unclear if the reaction of microcirculation in the cochlea was analogous to digital vessels. The synergistic effect of noise and vibration might be considered a stressor that impacts temporary threshold shifts. The chainsaw operation demanded high energy. This energy demand activates the sympathetic nervous system, which might override the autoregulation of the inner ear and fingers as it disturbs the compensatory changes in the peripheral circulation.

4.3. Other Resulting Effects of Combined Exposure of Noise + Hand Arm Vibration

Chainsaw operation causes gradual decreases in finger skin temperature with cyclic changes corresponding to each exposure and break period, as found by researchers Pyykko, Starck and Pekkarinen, 1986 [19]. On the other hand, chainsaw handle temperature increased with increased operation times due to the running engine, as shown by Miyakita, Miura, and Futatsuka, 1987 [21]. The study conducted by Pyykko, Pekkarinen, and Starck, 1987 [14] on the analysis of risk factors for sensory neural hearing loss during combined noise and vibration exposure found that smoking did not appear to explain any significant variation in SNHL.

The VWF or skin temperature was found to be more significant in older persons (>50 years) in a study conducted by Iki et al., 1989 [23] on the hearing of forestry workers affected with VWF. It was found that cutaneous blood flow was regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, which was measured by skin temperature under controlled conditions. A slower skin temperature recovery after cessation of cold stimuli indicates that the nervous system reacted more intensely to cold stimuli. The researchers Pyyko et al., 1989 [17] studied risk factors in the genesis of SNHL. At 4000 Hz, a statistically significant correlation was found between VWF, serum LDL-cholesterol concentration, and use of antihypertensive drugs and SNHL which explained 28% of the variance in SNHL. The SNHL was observed to be not significantly correlated with salicylate medicine consumption, diastolic and systolic blood pressure, and smoking.

The combined effects of noise and HAV on auditory organ and peripheral circulation was studied by Miyakita, Miura, and Futatsuka, 1991 [26]. Three experimental conditions were used in the study: (1) subjects operated the chainsaw without any cutting involved, (2) subjects operated the chainsaw with double hearing protection (earmuffs and plugs), and (3) subjects stood beside someone operating the chainsaw. The researchers found that finger skin temperature decreased gradually during chainsaw operation. However, the handle temperature of the chainsaw increased. The finger skin temperature decreases considerably in Exposure 1 compared to Exposure 2 with more exposure time. The early stages did not show significant differences in skin temperature. No significant differences were observed for Exposure 1 and Exposure 3. The changes in blood flow had similar patterns to finger skin temperature. When the subjects operated the chainsaw at a higher working temperature, there was a significant reduction in finger skin temperature compared to the condition when subjects used double hearing protection.

The age and VWF exposure duration did not significantly correlate with average body sway velocity (ASV), as found by Iki, 1994 [27] while studying VWF as a risk factor for hearing loss and postural instability. Significant differences were found for ASV between the highest and lowest hearing subjects. The researchers Iftime, Dumitrascu and Ciobanu, 2020 [32] discovered that forestry workers revealed a high percentage of osteomusculoskeletal disorders (25.23%) when they conducted a study on forestry chainsaw operators’ exposure to occupational risk factors and incidence of professional diseases.

4.4. Noise and Hand Arm Vibration from Various Equipment

Chainsaws manufactured before 1970 caused hand-arm vibration between 10 and 20 ms−2 (root means square), and the later models after 1970 had 2 to 6 ms−2 [14]. The development of anti-vibrating chainsaws in 1972 produced a weighted acceleration of 1.8–2.2 ms−2, along with features of reduced weight and impulsiveness of vibration. This made it possible for workers to increase tool usage exposure time to 5 h a day [22].

Neitzel and Yost [28] assessed different forestry tasks for noise and vibration in 2002. The average readings for National Institute Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) time-weighted average (TWA) sound level meter settings were 90.2 ± 5.1 dBA and 86.1 ± 6.2 dBA for Occupational Safety and Health-OSHA, respectively. The highest OSHA and NIOSH noises, TWA by operation, were observed in felling and road construction. Similarly, tree fellers and hook tenders are identified by job titles. The maximum whole-body vibration resulted from log processing (9.17 ms−2) and front-end loader (2.53 ms−2), respectively. The highest hand-arm vibration of 10.36 ms−2 was observed for tree felling. In the x-axis, the notching stump activity resulted in the highest HAV (8.12 ms−2). In the y-axis, the tree felling task resulted in the greatest HAV (5.64 ms−2). For the z-axis, chain idling produced the most HAV (6.95 ms−2). The chainsaw had the highest HAV Aeq with 6 ms−2, 4.26 ms−2 and 5.46 ms−2 for the x, y and z axes, respectively.

Monarca et al., 2009 [29] studied noise, vibration and dust in nut farms. The researchers found that the noise produced was >90 dB for various equipment such as towed harvesters, self-propelled harvesters, power-takeoff propelled harvesting devices (both hydraulic and mechanical), tractors, swathers, and blowers. Whole body vibration and hand-arm vibration for 8 h of exposure ranged from 0.21–0.97 ms−2 and 1.19–4.41 ms−2, respectively. Butkis and Vasiliauskas [31] evaluated farmers’ exposure to noise and vibration in small and medium-sized farms in 2017. The researchers reported that mean noise generated by combine harvesters, tractors with cabs, tractors without cab handheld tools for machine maintenance, handheld and guided tools for environmental works (lawnmowers, brush cutters, chainsaws etc.), grain equipment (augers, dryers, bin fans) and dairy farm equipment were 85.8, 87.3, 92, 94.3, 89.9, 86.2 and 82.4 dBA, respectively. Grain farming was observed to be louder than dairy farming. The noisiest activity in dairy farming was mechanized milking (87.1 dBA). For self-propelled, hand-guided and handheld machinery, the majority of HAV was in the range of 2.5–5 ms−2, and 35% of the cases had 1.15 ms−2 for WBV. Air impact wrenches had the highest HAV of 8.9 ms−2, chainsaws and grinders > 5 ms−2 and impact hammers > 8 ms−2. For WBV, during cultivation unsuspended tractors generated the highest value of 2.86 ms−2 and combine harvesters with 2.19 ms−2.

4.5. Additional Observations

The use of earmuffs resulted in equivalent noise levels below 85 dB when used with helmet liners [22]. The helmet liners used by forestry workers increased the attenuation by 2–6 dBA. Earmuffs were found to attenuate high frequencies better than lower ones. Iftime, Dumitrascu and Ciobanu, 2020 [32] studied chainsaw operators’ exposure to occupational risk factors and incidence of professional diseases specific to the forestry field. The HAVs measured were associated with the wood type (soft or hard), the diameter of the tree, the topography of the land, chainsaw handling technique, wear and tear of equipment, capacity and dimensions of chainsaws, worker positioning while felling, cutting and trimming along with climatic conditions. The researchers Murata, Araki, and Aono, 1990 [25] said that the peak latency of brainstem auditory evoked potential-BAEP in chainsaw operators up to V-component, and interpeak latency between I and V was observed to be significantly longer. For brush saw operators, the peak latency (between I and V components) was significantly correlated with the number of years worked. No significant prolongation of BAEP latencies was found. The median nerve conduction for both chainsaw and brush saw operators was significantly slowed. The maximum voluntary contraction of brush saw operators was significantly correlated with years worked.

5. Conclusions

Hearing is impacted by noise and aging. Workers with VWF had greater hearing loss compared to workers without VWF. The combined exposure to noise and VWF made subjects more prone to hearing loss. The synergistic effect of noise and vibration appears to create a greater temporary threshold shift. The proposed mechanisms behind increased hearing loss in subjects exposed to simultaneous noise and VWF exposure are: (a) decreased blood flow resulting in ischemic damage and vibration damage transmitted via bone conduction due to prolonged and strong excitation of receptor cells, (b) digital arteries narrowing which results in increased oxygen demand, (c) hyper-responsiveness of the arteries to noradrenaline (d) changes in peripheral circulation and (e) hypersensitivity to catecholamine in a local median muscular layer along with hormonal effects. The sympathetic nervous system plays a major role in the genesis of VWF. VWF also explained some variance in postural stability and osteomusculoskeletal disorders. Exposure to hand-arm vibration could cause a significant decrease in finger skin temperature as well as musculoskeletal disorders. Modern chainsaws are quieter than older models. However, exposure times with chainsaws have increased as the vibration levels of newer chainsaws were reduced, making them more comfortable to use. Engineering controls such as acoustic treatment, enclosing engines, isolating heavy equipment operator compartments, and installation of more effective mufflers can reduce both noise and HAV. Despite the progress made in improving equipment and working conditions, noise remains a problem, particularly in agricultural and forestry settings.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tak, S.; Davis, R.R.; Calvert, G.M. Exposure to Hazardous Workplace Noise and Use of Hearing Protection Devices among US Workers—NHANES, 1999–2004. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2009, 52, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaper, R.; Sesek, R.; Oh, J. Performance of Smart Device Noise Measurement Applications: A Literature Review. Prof. Saf. 2021, 66, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fredianelli, L.; Lercher, P.; Licitra, G. New Indicators for the Assessment and Prevention of Noise Nuisance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minichilli, F.; Gorini, F.; Ascari, E.; Bianchi, F.; Coi, A.; Fredianelli, L.; Licitra, G.; Manzoli, F.; Mezzasalma, L.; Cori, L. Annoyance Judgment and Measurements of Environmental Noise: A Focus on Italian Secondary Schools. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dratva, J.; Phuleria, H.C.; Foraster, M.; Gaspoz, J.-M.; Keidel, D.; Künzli, N.; Liu, L.-J.S.; Pons, M.; Zemp, E.; Gerbase, M.W.; et al. Transportation Noise and Blood Pressure in a Population-Based Sample of Adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, D.; Licitra, G.; Vigotti, M.A.; Fredianelli, L. Effects of Exposure to Road, Railway, Airport and Recreational Noise on Blood Pressure and Hypertension. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukić, L.; Mihanović, V.; Fredianelli, L.; Plazibat, V. Seafarers’ Perception and Attitudes towards Noise Emission on Board Ships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Prato, A.; Lesina, L.; Schiavi, A. Effects of Low-Frequency Noise on Human Cognitive Performances in Laboratory. Build. Acoust. 2018, 25, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, H.M.; Oudshoorn, C.G. Annoyance from Transportation Noise: Relationships with Exposure Metrics DNL and DENL and Their Confidence Intervals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licitra, G.; Fredianelli, L.; Petri, D.; Vigotti, M.A. Annoyance Evaluation Due to Overall Railway Noise and Vibration in Pisa Urban Areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 568, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzet, A. Environmental Noise, Sleep and Health. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing & Hunting Statistics|NIOSH|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/ohl/agriculture.html (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Overall Statistics-All U.S. Industries-OHL|NIOSH|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/ohl/overall.html (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Pyykkö, I.; Pekkarinen, J.; Starck, J. Sensory-Neural Hearing Loss during Combined Noise and Vibration Exposure. An Analysis of Risk Factors. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1987, 59, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyykkö, I.; Starck, J.; Färkkilä, M.; Hoikkala, M.; Korhonen, O.; Nurminen, M. Hand-Arm Vibration in the Aetiology of Hearing Loss in Lumberjacks. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1981, 38, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, R.A.; Sauve, J.T.; Jiang, D. Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Construction Workers Being Assessed for Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome. Can. J. Public Health-Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2010, 101, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, I.; Koskimies, K.; Starck, J.; Pekkarinen, J.; Färkkilä, M.; Inaba, R. Risk Factors in the Genesis of Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Finnish Forestry Workers. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1989, 46, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iki, M.; Kurumatani, N.; Hirata, K.; Moriyama, T.; Satoh, M.; Arai, T. Association between Vibration-Induced White Finger and Hearing Loss in Forestry Workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1986, 12, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, I.; Starck, J.; Pekkarinen, J. Further Evidence of a Relation between Noise-Induced Permanent Threshold Shift and Vibration-Induced Digital Vasospasms. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 1986, 7, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakita, T.; Miura, H.; Futatsuka, M. Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Relation to Vibration-Induced White Finger in Chain-Saw Workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1987, 13, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakita, T.; Miura, H.; Futatsuka, M. An Experimental Study of the Physiological Effects of Chain Saw Operation. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1987, 44, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, J.; Pekkarinen, J.; Pyykkö, I. Impulse Noise and Hand-Arm Vibration in Relation to Sensory Neural Hearing Loss. Scand J. Work Environ. Health 1988, 14, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iki, M.; Kurumatani, N.; Satoh, M.; Matsuura, F.; Arai, T.; Ogata, A.; Moriyama, T. Hearing of Forest Workers with Vibration-Induced White Finger: A Five-Year Follow-Up. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1989, 61, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iki, M.; Kurumatani, N.; Moriyama, T.; Ogata, A. Vibration-Induced White Finger and Auditory Susceptibility to Noise Exposure. Kurume Med. J. 1990, 37, S33–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, K.; Araki, S.; Aono, H. Central and Peripheral Nervous System Effects of Hand-Arm Vibrating Tool Operation. A Study of Brainstem Auditory-Evoked Potential and Peripheral Nerve Conduction. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1990, 62, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyakita, T.; Miura, H.; Futatsuka, M.C. Combined effects of noise and hand-arm vibration on auditory organ and peripheral circulation. J. Sound. Vib. 1991, 151, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iki, M. Vibration-Induced White Finger as a Risk Factor for Hearing Loss and Postural Instability. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 1994, 57, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neitzel, R.; Yost, M. Task-Based Assessment of Occupational Vibration and Noise Exposures in Forestry Workers. AIHA J. (Fairfax Va) 2002, 63, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monarca, D.; Cecchini, M.; Guerrieri, M.; Santi, M.; Bedini, R.; Colantoni, A. Safety and Health of Workers: Exposure to Dust, Noise and Vibrations. In Proceedings of the VII International Congress on Hazelnut, Leuven, Belgium, 23–27 June 2009; Varvaro, L., Franco, S., Eds.; ILO: Viterbo, Italy, 2009; Volume 845, pp. 437–442, ISBN 978-90-6605-712-8. [Google Scholar]

- Turcot, A.; Girard, S.A.; Courteau, M.; Baril, J.; Larocque, R. Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Combined Noise and Vibration Exposure. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkus, R.; Vasiliauskas, G. Farmers’ Exposure to Noise and Vibration in Small and Medium-Sized Farms; Raupeliene, A., Ed.; Aleksandras Stulginskis University: Akademija, Lithuania, 2017; pp. 232–236. ISBN 978-609-449-128-3. [Google Scholar]

- Iftime, M.D.; Dumitrascu, A.-E.; Ciobanu, V.D. Chainsaw Operators’ Exposure to Occupational Risk Factors and Incidence of Professional Diseases Specific to the Forestry Field. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Erg. 2020, 28, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).