Understanding How School-Based Interventions Can Tackle LGBTQ+ Youth Mental Health Inequality: A Realist Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Realist Methodology

2.2. Realist Causation

2.3. Young People’s Involvement

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Sample Recruitment and Demographics

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

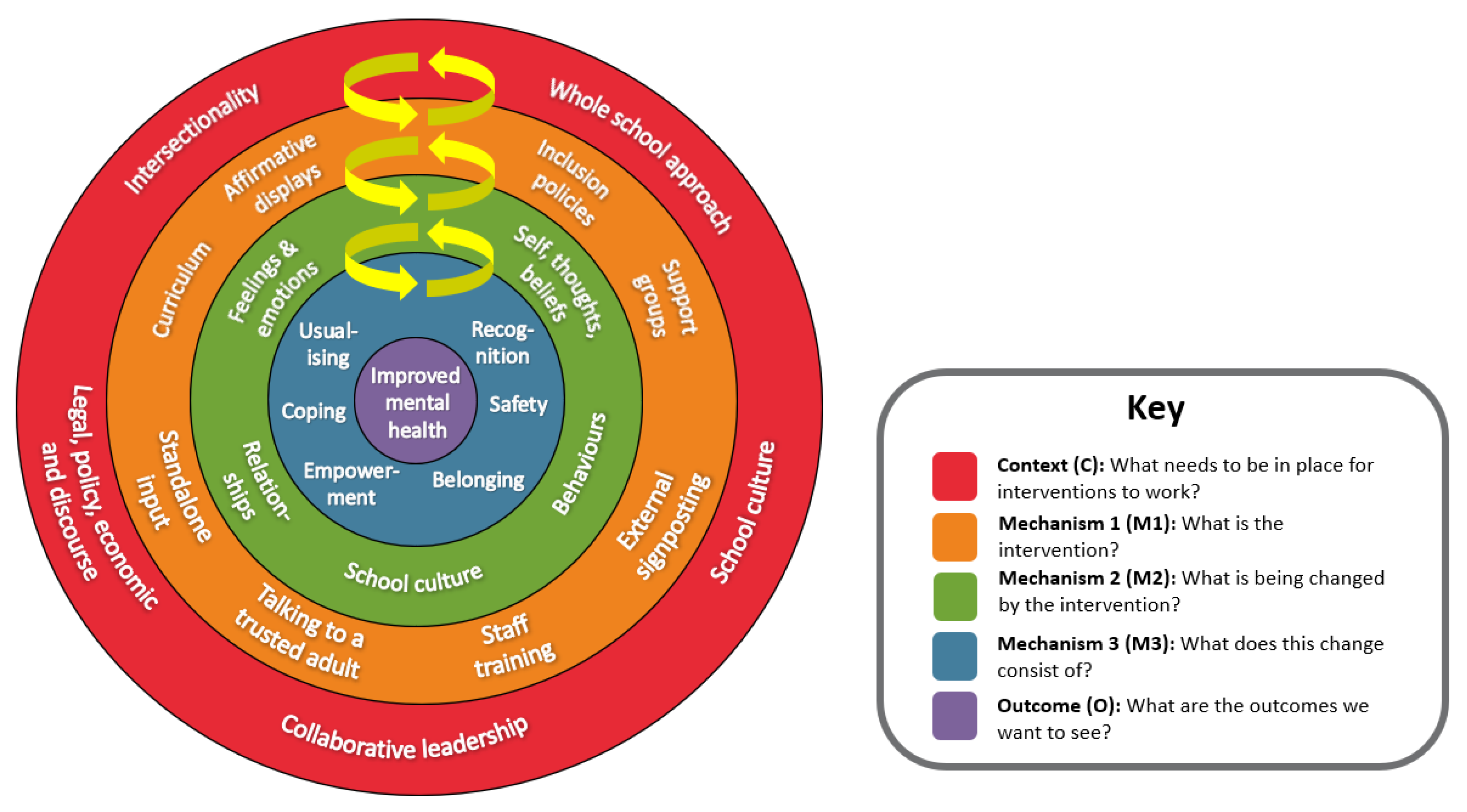

3.1. Programme Theory

3.2. Context Factors

3.2.1. Whole School Approach

“We had LGBTQ displays, maybe one pride assembly a year, and an LGBTQ club, but little to none of it helped with understanding, much [of] those displays only really felt like they were doing it to help their image, instead of just doing it out of pure support and the support groups, since the location was plastered around, the homophobic guys tended to lurk near the room and just point and laugh, really.”(LGBTQ+ young person)

3.2.2. Collaborative Leadership

“I went to the Head, and I said “look, this is something that I want to do a lot more of in school in terms of this” and she just gave me absolute carte blanche which has been brilliant. […] I think the really, really strong thing is that there’s one person that leads it. It’s like that go to.”(School Staff)

3.2.3. Intersectionality

“I need celebrity representation of LGBT people from BME faith communities to make me feel empowered. My community and culture is part of my identity—I have not lost that.”(LGBTQ+ young person)

“We know that LGBTQ young people have experienced poorer mental health than their non-LGBTQ peers, but that is more so for those who access free school meals, for those who are Black, for those who are disabled. It is suggested that the multiple experiences of isolation and knowing that the world is still a place that discriminates, then when the world is changing through stuff like COVID, the fear must be magnified, mustn’t it? So, I think doubly impacted by isolation plus anxiety about the state of the world.”(Intervention Practitioner)

3.2.4. Legal, Policy, Economic and Discursive Factors

“COVID has seen that actually schools haven’t prioritised these spaces, so therefore actually now we don’t really have focus on HBT bullying and or equally necessarily a commitment to creating LGBTQ+ safe spaces. Actually, it feels like regression, in that sense.”(Intervention Practitioner)

“Some of the responses that we have seen, in the last two years, I guess, to trans inclusive initiatives have been reminiscent of the run up to Section 28 back in 1988, absolutely. And so I think the fear of some kind of replies from parents or the community is greater than what actually does happen when they actually do something.”(Intervention Practitioner)

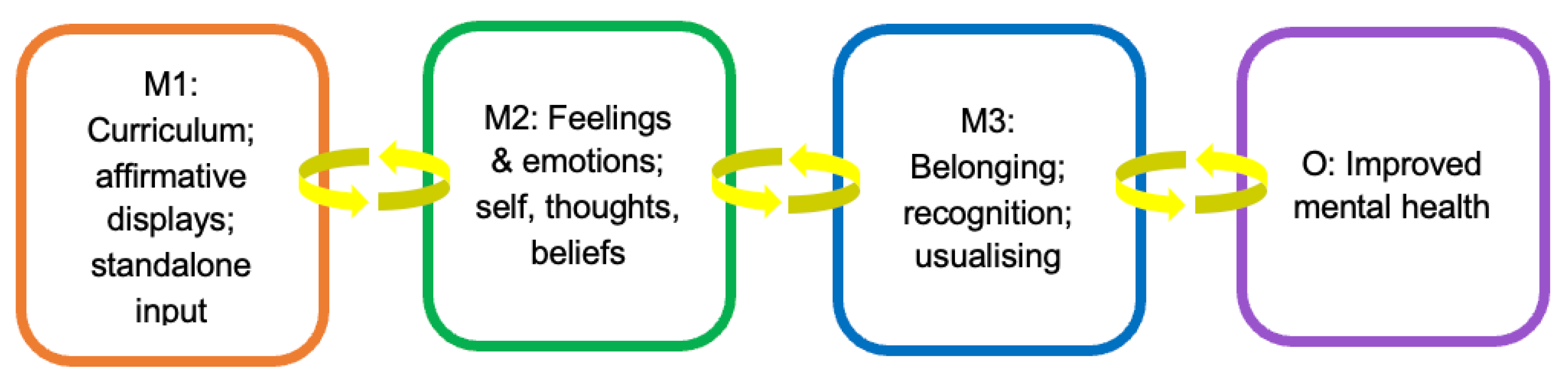

3.2.5. Causal Pathway 1: Interventions That Promote LGBTQ+ Visibility

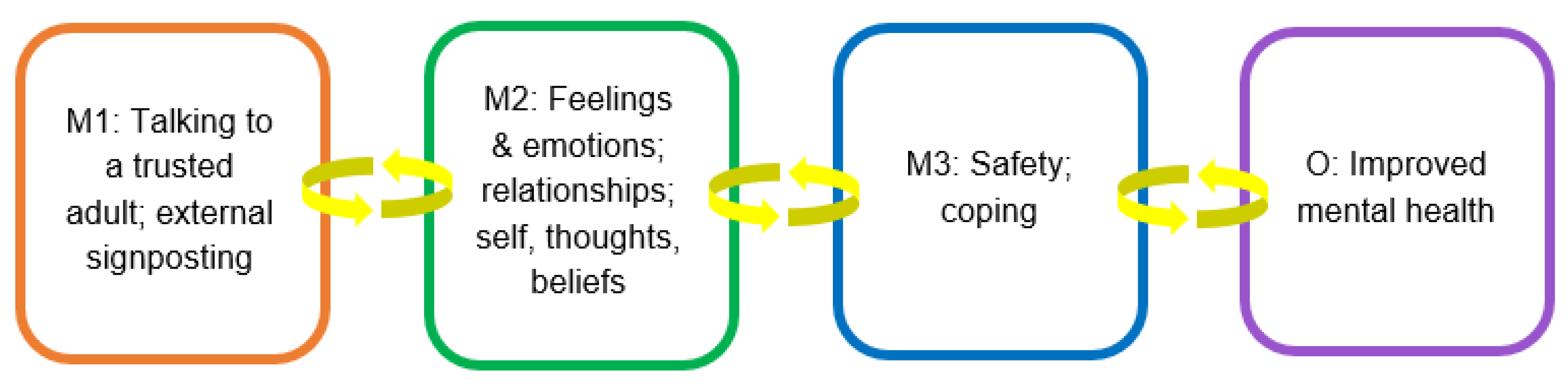

3.2.6. Causal Pathway 2: Interventions for Talking and Support

“I need to speak to someone like a teacher. Who can understand me and offer support. My mates in school I would not speak to as they can judge quickly. Signposting is good but if you’re in a bad place it’s too much Information. Counselling would be good but guided and supported. It hard being yourself, I come from a religious family and my community does not accept of LGBT equality at all. I think mentally the struggles can be hard no doubt.”

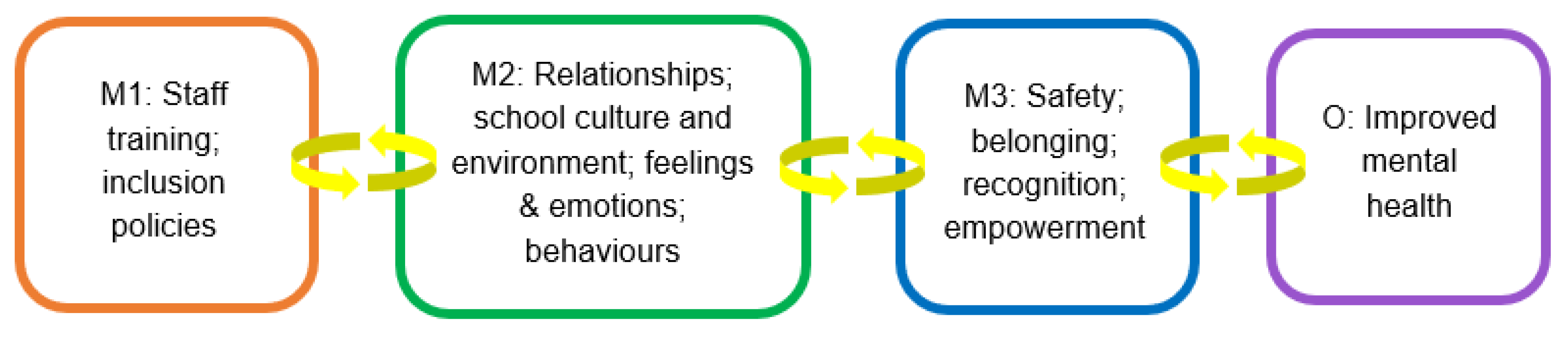

3.2.7. Causal Pathway 3: Interventions That Change Institutional School Culture

“Inclusion policies is very important, having policies that consider is a long-term strategy [...] the LGBTQ+ people in the school won’t feel shy/alone in the school. We would feel recognized and even empowered. Issues like bullying won’t happen anymore.”(LGBTQ+ young person)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fish, J.N. Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, M.P.; Dietz, L.J.; Friedman, M.S.; Stall, R.; Smith, H.A.; McGinley, J.; Thoma, B.C.; Murray, P.J.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Brent, D.A. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irish, M.; Solmi, F.; Mars, B.; King, M.; Lewis, G.; Pearson, R.M.; Pitman, A.; Rowe, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Lewis, G. Depression and self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood in sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals in the UK: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, G.; Lambert, K.; Patlamazoglou, L. The mental health of transgender young people in secondary schools: A scoping review. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Castillo, D.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.A.; del Mar Pastor-Bravo, M.; Sánchez-Muñoz, M.; Fernández-Espín, M.E.; García-Arenas, J.J. School victimization in transgender people: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giacomo, E.; Krausz, M.; Colmegna, F.; Aspesi, F.; Clerici, M. Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteat, V.P.; O’Brien, M.D.; Rosenbach, S.B.; Finch, E.K.; Calzo, J.P. Depression, Anxiety, and Interest in Mental Health Resources in School-Based Gender-Sexuality Alliances: Implications for Sexual and Gender Minority Youth Health Promotion. Prev. Sci. 2021, 22, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, T.; Taylor, C.; Campbell, C. “You can’t break… when you’re already broken”: The importance of school climate to suicidality among LGBTQ youth. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2016, 20, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A.; Cohen, J.; Guffey, S.; Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. A review of school climate research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.J. A Comparative Study of High School Perceptions of School Climate Between Students, Teachers, and Parents. Ph.D. Thesis, Neumann University, Aston, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Out in the Open: Education Sector Responses to Violence Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression; UNESCO: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chances, M.Y. Youth Chances Summary of First Findings: The Experiences of LGBTQ Young People in England; METRO: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Epps, B.; Markowski, M.; Cleaver, K. A rapid review and narrative synthesis of the consequences of non-inclusive sex education in UK schools on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and questioning young people. J. Sch. Nurs. 2021, 39, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baams, L.; Russell, S.T. Gay-straight alliances, school functioning, and mental health: Associations for students of color and LGBTQ students. Youth Soc. 2021, 53, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancheta, A.J.; Bruzzese, J.-M.; Hughes, T.L. The impact of positive school climate on suicidality and mental health among LGBTQ adolescents: A systematic review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2021, 37, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Finan, L.J.; Bersamin, M.; Fisher, D.A. Sexual orientation–based depression and suicidality health disparities: The protective role of school-based health centers. J. Res. Adolesc. 2020, 30, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyano, N.; del Mar Sanchez-Fuentes, M. Homophobic bullying at schools: A systematic review of research, prevalence, school-related predictors and consequences. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 53, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Keyes, K.M. Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C.; Szalacha, L.; Westheimer, K. School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saewyc, E.M.; Konishi, C.; Rose, H.A.; Homma, Y. School-based strategies to reduce suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and discrimination among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents in Western Canada. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. IJCYFS 2014, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, L.M. School Supports for LGBTQ Students: Counteracting the Dangers of the Closet. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.M.; Shattuck, D.G.; Green, A.E.; Vitous, C.A.; Ramos, M.M.; Willging, C.E. Amplification of school-based strategies resulting from the application of the dynamic adaptation process to reduce sexual and gender minority youth suicide. Implement. Res. Pract. 2021, 2, 2633489520986214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.M.; Beltran, O.; Armstrong, H.L.; Jayne, P.E.; Barrios, L.C. Protective factors among transgender and gender variant youth: A systematic review by socioecological level. J. Prim. Prev. 2018, 39, 263–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessel, A.B.; Kulick, A.; Wernick, L.J.; Sullivan, D. The importance of teacher support: Differential impacts by gender and sexuality. J. Adolesc. 2017, 56, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, P.J.; Juday, T.R.; Charters, C.W. A School-Based Program to Improve Life Skills and to Prevent HIV Infection in Multicultural Transgendered Youth in Hawai’i. J. Gay Lesbian Issues Educ. 2004, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, N.C. Expanding, Refining, and Replicating Research on High School Gay-Straight Student Alliances and Sexual Minority Youth. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burk, J.; Park, M.; Saewyc, E.M. A media-based school intervention to reduce sexual orientation prejudice and its relationship to discrimination, bullying, and the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents in Western Canada: A population-based evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteat, V.P.; Yoshikawa, H.; Calzo, J.P.; Gray, M.L.; DiGiovanni, C.D.; Lipkin, A.; Mundy-Shephard, A.; Perrotti, J.; Scheer, J.R.; Shaw, M.P. Contextualizing Gay-Straight Alliances: Student, advisor, and structural factors related to positive youth development among members. Child Dev. 2015, 86, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteat, V.P.; Calzo, J.P.; Yoshikawa, H. Promoting youth agency through dimensions of gay–straight alliance involvement and conditions that maximize associations. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapointe, A.; Crooks, C. GSA members’ experiences with a structured program to promote well-being. J. LGBT Youth 2018, 15, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.L.; Austin, A.; McInroy, L.B. School-based groups to support multiethnic sexual minority youth resiliency: Preliminary effectiveness. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2014, 31, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, N.C. The potential to promote resilience: Piloting a minority stress-informed, GSA-based, mental health promotion program for LGBTQ youth. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.L.; Audette, L.; Mitchell, Y.L.; Simpson, I.; Ward, J.; Ackerman, L.; Gonzalez, K.A.; Washington, K. LGBTQ student experiences in schools from 2009–2019: A systematic review of study characteristics and recommendations for prevention and intervention in school psychology journals. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 115–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, E.; Kaley, A.; Kaner, E.; Limmer, M.; McGovern, R.; McNulty, F.; Nelson, R.; Geijer-Simpson, E.; Spencer, L. Reducing LGBTQ+ Adolescent Mental Health Inequalities: A Realist Review of School-Based Interventions. BMC Public Health 2022. pre-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagosh, J. Realist synthesis for public health: Building an ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Westhorp, G.; Pawson, R. Protocol-realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: Evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.I.; Meezan, W. Applying ethical standards to research and evaluations involving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. In Handbook of Research with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, M.; Parker, N. Doing Mental Health Research with Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Qualitative Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elze, D. Strategies for recruiting and protecting gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender youths in the research process. In Handbook of Research with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 60–88. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, A. The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation 2016, 22, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K. Bridging the digital divide: Reflections on using WhatsApp instant messenger interviews in youth research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2022, 19, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, A.; Peel, E.; Shaw, R. Online interviewing in psychology: Reflections on the process. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2011, 8, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkin, S.; Forster, N.; Hodgson, P.; Lhussier, M.; Carr, S.M. Using computer assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS; NVivo) to assist in the complex process of realist theory generation, refinement and testing. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, B.; McAuliffe, E.; Power, J.; Vallières, F. Data analysis and synthesis within a realist evaluation: Toward more transparent methodological approaches. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919859754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Westhorp, G.; Greenhalgh, J.; Manzano, A.; Jagosh, J.; Greenhalgh, T. Quality and reporting standards, resources, training materials and information for realist evaluation: The RAMESES II project. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W.M.; Donnelly, J.P. Research Methods Knowledge Base; Atomic Dog Publishing Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Making every School a Health-Promoting School: Implementation Guidance; World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Glazzard, J.; Stones, S. Running Scared? A Critical Analysis of LGBTQ+ Inclusion Policy in Schools. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 613283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagosh, J.; Bush, P.L.; Salsberg, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Green, L.W.; Herbert, C.P.; Pluye, P. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind (Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN. General Comment No. 20 on the Implementation of the Rights of the Child during Adolescence; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Classification | Young People (N = 10) | Intervention Practitioners (N = 9) | School Staff (N = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13–16 | 4 | - | - |

| 17–18 | 6 | - | - | |

| 21–30 | - | 1 | 2 | |

| 31–40 | - | 5 | - | |

| 41–50 | - | 2 | 1 | |

| 51–60 | - | 1 | - | |

| Gender | Male | 5 | 3 | - |

| Female | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Non-binary | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Are you trans? | Yes | 4 | 2 | - |

| No | 4 | 7 | 3 | |

| Unsure | 2 | - | - | |

| Ethnicity | English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 7 | 7 | 2 |

| White (Other) | - | 1 | - | |

| European | - | 1 | - | |

| African | 2 | - | - | |

| Pakistani | 1 | - | - | |

| Jewish European | - | - | 1 | |

| Sexual orientation | Lesbian | 2 | - | 1 |

| Bisexual | 3 | 1 | - | |

| Gay | 3 | 3 | - | |

| Pansexual | 1 | - | - | |

| Queer | - | 3 | 1 | |

| Heterosexual | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Education level | No qualifications | 4 | - | - |

| GCSE | 4 | - | - | |

| AS Levels | 1 | - | - | |

| A Levels | 1 | - | - | |

| First Degree | - | 6 | 2 | |

| Higher Degree | - | 3 | 1 | |

| Occupation | Student | 8 | - | - |

| Unemployed | 2 | - | - | |

| Full-time Employment | - | 6 | 2 | |

| Part-time Employment | - | 3 | 1 | |

| Do you have a disability? | No | 7 | 6 | 2 |

| Yes | 3 | 3 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McDermott, E.; Kaley, A.; Kaner, E.; Limmer, M.; McGovern, R.; McNulty, F.; Nelson, R.; Geijer-Simpson, E.; Spencer, L. Understanding How School-Based Interventions Can Tackle LGBTQ+ Youth Mental Health Inequality: A Realist Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054274

McDermott E, Kaley A, Kaner E, Limmer M, McGovern R, McNulty F, Nelson R, Geijer-Simpson E, Spencer L. Understanding How School-Based Interventions Can Tackle LGBTQ+ Youth Mental Health Inequality: A Realist Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054274

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcDermott, Elizabeth, Alex Kaley, Eileen Kaner, Mark Limmer, Ruth McGovern, Felix McNulty, Rosie Nelson, Emma Geijer-Simpson, and Liam Spencer. 2023. "Understanding How School-Based Interventions Can Tackle LGBTQ+ Youth Mental Health Inequality: A Realist Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054274

APA StyleMcDermott, E., Kaley, A., Kaner, E., Limmer, M., McGovern, R., McNulty, F., Nelson, R., Geijer-Simpson, E., & Spencer, L. (2023). Understanding How School-Based Interventions Can Tackle LGBTQ+ Youth Mental Health Inequality: A Realist Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054274