Abstract

Plants contain underutilized resources of compounds that can be employed to combat viral diseases. Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. (syn. Aloe barbadensis Mill.) has a long history of use in traditional medicine, and A. vera extracts have been reported to possess a huge breadth of pharmacological activities. Here, we discuss the potential of A. vera compounds as antivirals and immunomodulators for the treatment of viral diseases. In particular, we highlight the use of aloe emodin and acemannan as lead compounds that should be considered for further development in the management and prevention of viral diseases. Given the immunomodulatory capacity of A. vera compounds, especially those found in Aloe gel, we also put forward the idea that these compounds should be considered as adjuvants for viral vaccines. Lastly, we present some of the current limitations to the clinical applications of compounds from Aloe, especially from A. vera.

1. Introduction

Recent large outbreaks of acute viral diseases, including those caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-2, Ebola virus, Zika virus, chikungunya virus, SARS-CoV, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome CoV, and influenza virus, have underscored the limitations of currently available tools for controlling viral outbreaks. Ideally, both antivirals and vaccines should be on hand in the event of an outbreak; antivirals will be given to those with active infection, and vaccines will be administered to the larger population. However, as highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2, the current response to viral (re)emergence is highly reactive: we only start searching for antivirals or design vaccines after viral emergence [1]. There is no repository of antivirals that can be dispatched for rapid outbreak response, hence the spike in death and hospitalizations throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. In the absence of effective antivirals and prior to vaccine approval, only non-pharmaceutical interventions could be imposed, and these measures have severely impacted global economy.

The increasing frequency of viral outbreaks necessitates global preparedness so that we may avoid a repeat of the protracted COVID-19 pandemic. Building a library of antivirals with broad-spectrum potential and developing them up to early human clinical trials is an ideal strategy in preparing for future outbreaks of known and unknown viral etiology. This strategy requires less knowledge of the emergent virus and, in turn, shorter lead time between outbreak and clinical deployment [1]. Further discovery and development of broad-spectrum antivirals and the expansion of targets of current antiviral candidates will therefore be instrumental to the management of future viral epidemics and pandemics [2].

Natural products contribute structural diversity and complexity to the current pool of drug candidates. Plants, in particular, are acknowledged as primary sources of new bioactive compounds. As of 2018, 44.1% of the reported natural compounds came from plants [3]. New plant species are continuously being discovered, adding further potential sources of novel bioactive compounds. However, despite their long history in traditional medicine and their success rates in other disease states, plants remain underutilized resources in the fight against viral diseases. Although secondary metabolites from plants have already been reported to inhibit viral infections in preclinical studies, an antiviral from plants is yet to be approved [4]. While synthetic small molecules, the most commonly approved antivirals, can be designed by chemists, the human imagination bears limitations. New ideas can be drawn from existing products in plants that have already evolved to be biologically active. Thus, plant compounds should be considered in developing new drugs, including those needed for the management and prevention of viral diseases.

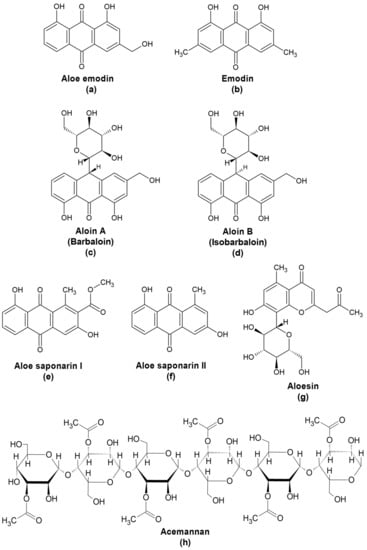

Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. (syn. Aloe barbadensis Mill.) is a succulent that grows in dry regions of Asia, Africa, America, and Europe. It belongs to the Asphodelaceae (Liliaceae) family, along with various Aloe species. The A. vera leaf consists of three layers that serve as sources of different compounds. The outermost layer or the rind, appears green and is the site of carbohydrate and protein synthesis [5,6]. The middle layer or the latex consists of yellow sap containing phenolics, including anthraquinones that are primarily present as glycosides. The innermost layer is the pulp, consisting of a clear gel that contains mainly polysaccharides such as acetylated mannans. A. vera extracts have long been used in folk medicine to cure digestive problems, skin problems, burns, wounds, diabetes, and high blood pressure [7]. It is also used as an additive in cosmetic products.

There is a large amount of evidence on the immunomodulatory effects compounds from A. vera, especially from A. vera gel. To a lesser extent, antiviral effects of A. vera extracts and compounds have also been reported. However, literature that weaves together the potential applicability of A. vera compounds in the management and prevention of a broad spectrum of viral diseases is limited. To fill this gap, here we discuss the potential of compounds isolated from Aloe spp., particularly A. vera, as direct-acting antivirals and as immunomodulators for the management of acute viral diseases. Additionally, we discuss the potential of some of the immunomodulators from Aloe as viral vaccine adjuvants to help prevent viral diseases. This manuscript should then provide information on A. vera compounds that can be developed to help combat the continuous threat of viral diseases.

2. Methodology

Literature searches for the antiviral effects of Aloe spp. and Aloe compounds were mainly performed using PubMed and Google Scholar employing “Aloe virus” or the name of the compound plus “virus” as search terms. For the immunomodulatory effects and adjuvant effects, “Aloe immune” and “Aloe adjuvant” were used as primary search words, with additional searches including specific targets such as “innate immunity,” “antibody,” or “T cell”. The results were then screened for their potential application in the context of viral diseases. In silico studies without in vitro data for the antiviral effects of the Aloe compounds were excluded from this review. References that attributed the effects of emodin to aloe emodin were also excluded under the premise that these isomers may possess different biological activities unless the primary source presented data for aloe emodin. The references used here were published from 1911 to 2022.

4. Aloe Compounds for the Regulation of Immune Responses to Viral Infection

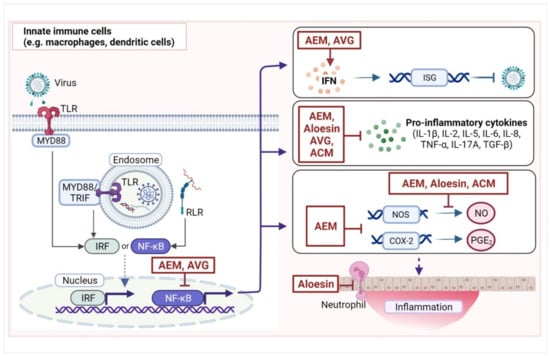

Viruses that penetrate the initial line of defenses (skin and mucosa) and enter the host are detected by pattern recognition receptors, especially Toll-like receptors (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9), retinoic acid-inducible gene I, and NOD-like receptors that are typically expressed in innate immune cells (e.g., dendritic cells and macrophages) (Figure 2) [42]. Upon activation, these receptors trigger the production of interferons (IFNs); chemokines; and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukins (IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-17) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) via transcription factors nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) or IFN regulatory factors [43]. The IFNs then activate IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), which exhibit various antiviral activities. Meanwhile, pro-inflammatory cytokines promote local inflammatory responses (e.g., vasodilation, vascular permeability, and tissue destruction) and the recruitment of innate effector cells (e.g., neutrophils, natural killer cells, and innate lymphoid cells) to facilitate the elimination of virus-infected cells. During this process, prostaglandins, especially prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) produced from arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), cause some of the classical signs of inflammation (redness, swelling, pain, and heat) in affected tissues. PGE2 is also involved in the regulation of cytokine production in macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs).

Figure 2.

Targets of compounds from Aloe, especially Aloe vera, in the innate immune response. Innate immune cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells, recognize viral infection through pattern recognition receptors such as the Toll-like receptors (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9) or RIG-I-like receptors (RLR). Upon signal stimulation, TLRs recruit adaptor proteins, such as myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) and TIR domain-containing adapter molecule 1 (TRIF). This initiates signaling cascades that activate transcription factors, mainly interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). IRFs are typically involved in the production of interferons (IFNs) that, in turn, stimulate the expression of products of IFN-stimulating genes (ISGs) that have antiviral functions. Meanwhile, NF-κB is a master regulator of the immune response and activates the transcription of several proteins involved in the immune response including ISGs and cytokines, such as interleukins (IL), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). NF-κB also activates the transcription of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-2 gene, which catalyzes the production of nitric oxide (NO) that regulates local inflammation. Moreover, NF-κB activates the transcription of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which induces inflammation. Tissue inflammation recruits other cells, such as granulocytic neutrophils, to the site of infection. Shown here are some of the reported targets of compounds from Aloe spp., especially A. vera, such as aloe emodin (AEM), A. vera gel (AVG), acemannan (ACM), and aloesin in the innate immune response. While in most cases, A. vera compounds inhibit pro-inflammatory responses, they may also promote certain responses, such as IFN production. (Image was created with BioRender.com, accessed on 27 April 2022).

Activated DCs at the site of infection migrate to lymphoid tissues to present antigens to T cells, thereby initiating the adaptive immune response [44]. Viral antigen presentation by DCs stimulates the differentiation of naïve CD8+ T cells to cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) that destroy virus-infected cells. It also activates CD4+ T cells, which differentiate into T helper 1 (TH1) cells that further produce antiviral cytokines, and into T follicular helper (TFH) cells that promote antibody production in B cells. Adequate viral clearance typically allows the resolution of inflammation and a return to homeostasis. DCs, macrophages, activated regulatory T cells, B cells, and some natural killer cells secrete the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, which can then block the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in different target cells [43].

A persistent and exaggerated inflammatory response can cause tissue and organ damage that is seen in severe cases of acute viral diseases. Acute respiratory distress syndrome following COVID-19 or influenza virus pneumonia are characterized by persistent infiltration of immune cells in the lungs and by dysregulated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which eventually lead to organ damage [45]. On the other hand, inadequate immune responses, such as a failure or delay in producing IFNs, can also lead to the inability to clear the virus and a failure in initiating the cascade of the necessary immune responses [46,47]. Thus, modulating immune responses following viral infection may prove helpful in treating diseases. That corticosteroids were among the first drugs to show benefits for the management of severe COVID-19 suggests that immune regulation should be considered for the treatment of viral diseases with similar hyper-immunological profiles. A. vera extracts have demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity in several studies. In the following sections, we discuss some of the anti-inflammatory effects of Aloe compounds and the potential mechanisms underlying these effects.

4.1. Aloe Phenolics as Immunomodulatory Agents

4.1.1. Immunomodulatory Effects of Aloe Emodin

AEM has also been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects in vitro and in vivo (Table 3) (Figure 2). In a study by Yu et al., AEM was found to reduce the activity of natural killer cells and the phagocytic activity of macrophages from rats in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, AEM was found to increase IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α but not IL-6 and IFN-γ production of leukocytes [48]. Further supporting the anti-inflammatory effects of AEM on macrophages, incubation of RAW 264.7 macrophages with AEM attenuated lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (Nos) mRNA and nitric oxide (NO) production [49]. AEM was also found to reduce PGE2 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Further, AEM inhibited LPS-induced Cox2 mRNA levels in a dose-dependent manner in the macrophages. A rat paw edema model also indicated the anti-inflammatory effects of AEM and a derivative [50]. Moreover, in rats with complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced arthritis, AEM and a derivative reduced NO production in the rats relative to the untreated control. NO acts as an inflammatory mediator, and can be either anti- or pro-inflammatory, depending on concentration. Modulating NO production is therefore important in regulating the inflammatory response.

Table 3.

Immunomodulatory effects of Aloe vera components.

In a middle cerebral occlusion reperfusion rat model, AEM was able to reduce serum TNF-α levels, and protected rats from neurological deficits, suggesting that AEM protected the rats from neuroinflammation [51]. AEM treatment of LPS-stimulated microglial BV2 cell lines was able to inhibit the production of NO as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. In this model, AEM reduced the activity of NF-κB in a dose-dependent manner. Considering that NF-κB is a master regulator of immune responses, activating the transcription of ISGs, cytokines, NOS, and COX-2, the anti-inflammatory effects of AEM is likely mediated by NF-κB (Figure 2).

In the context of viral infections, AEM was able to stimulate the activation of IFN-α transcription in vitro [20]. It also activated the IFN stimulation response element (ISRE)-driven promoter and the gamma-activated sequence (GAS)-containing promoter, which are involved in the expression of ISGs. Indeed, AEM enhanced the transcription of two ISG products, protein kinase R (PKR) and 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), in a monocytic cell line (HL-CZ cells). Thus, AEM may be able to inhibit viral infection by enhancing the antiviral immune state.

Supporting this, Li et al. [52] demonstrated that the inhibitory effects of AEM against IAV correlated with increased levels of galectin-3, which, in turn, upregulated IFN-β and IFN-γ. The non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of influenza A viruses inhibits the IFN-α-inducible Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway that typically regulates the expression of ISGs [66]. In their study, Li et al. further showed that AEM was able to attenuate the effects of NS1 in vitro, promoting the phosphorylation of STAT1, which in turn promoted the expression of PKR and OAS in NS1- producing cells. However, the effects of AEM may be independent of IFN-α, as IFN-α did not increase in response to AEM treatment. Meanwhile, galectin-3 has been suggested to activate the JAK-STAT pathway [67]. Thus, the findings of Li et al. suggest that AEM activates the JAK-STAT pathway through galectin-3. However, these results will have to be replicated and characterized.

Thus, in addition to direct antiviral effects, AEM appears to modulate immune responses, including those that are relevant to viral infections. An antiviral agent with the capacity to target both viral and host factors would prove beneficial especially in combatting viruses that tend to develop resistance against direct-acting antivirals, as is the case for IAV and HIV drugs. Furthermore, an antiviral agent with immunomodulating capacity can be administered in a large therapeutic window over the course of a viral disease. Antivirals are given early in the course of the disease to accelerate viral clearance, while immunomodulators are given late in the disease course, typically in severe disease cases, to temper hyper-immune responses. A drug that targets both the virus and the immune response may be given in the middle stages of infection to reduce the likelihood of progression to severe or critical illness.

4.1.2. Immunomodulatory Effects of Aloin

In addition to inhibitory effects on influenza virus infection in vitro, aloin also exhibits immunomodulatory effects on influenza A H1N1 (PR8)-infected mice with adoptively transferred hemagglutinin (HA)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [24]. Pulmonary infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells increased following aloin treatment in infected mice, and these cells showed increased production of IFN-γ and TNF-α. NA-mediated TGF-β activation was also reduced in the lungs. Co-treatment with aloin also appeared to enhance the effects of oseltamivir on HA-specific T cell responses in influenza-infected mice. Specifically, aloin augmented the oseltamivir-induced reduction in TGF-β and increase in IFN-γ. Similar trends were observed when infected mice were first treated with aloin and then treated with oseltamivir two days later.

Influenza NA activates TGF-β by removing sialic acid motifs from the latent form of TGF-β. This cytokine has both pro- and anti-inflammatory functions. Inhibition of TGF-β has been observed to reduce epithelial cell adherence of group A Streptococcus bacteria, which are common coinfections with influenza virus that contribute to the morbidity and mortality of influenza virus infections [68]. TGF-β may also act as a pro-viral factor in influenza virus infection by suppressing the production of IFN-β, which allows viral proliferation, further indicating that increased levels of TGF-β may augment the pathology of influenza virus infection [69]. Meanwhile, increased TNF-α production has been correlated with reduced viral titers in vitro, suggesting that it has antiviral functions [70]. Thus, the ability of aloin to inhibit TGF-β and to promote TNF-α may contribute to the protective effects of aloin in influenza A H1N1 (PR8)-infected mice. However, the immune pathways directly targeted by aloin in the context of influenza virus infection will have to be elucidated further.

4.1.3. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Aloesin

Aloesin is a chromone (Figure 1) found in the latex of a number of Aloe species, and it has exhibited anti-inflammatory activity. An aloesin-supplemented diet markedly reduced deformity and granulocyte infiltration in colon segments taken from rat colitis models, indicating anti-inflammatory effects of aloesin (Table 3) [53]. Serum TNF-α and PGE2 levels, and colonic Tnfa and Il1b mRNA levels were also reduced by supplementation of aloin, Aloe gel, or aloesin to the diets of the rat colitis models. Moreover, rats fed with aloin, Aloe gel, or aloesin had reduced plasma levels of leukotriene B4 (LTB4), an immunomodulatory chemokine, with aloesin reducing LTB4 levels to baseline. LTB4 is involved in the recruitment of innate immune cells, which leads to the production of cytokines [71]. LTB4 may be one of the direct targets of aloesin, leading to overall changes in cytokine levels. However, a chromone analog was also indicated to reduce TNF-α production through the inhibition of NF-κB, suggesting that NF-κB may also be a target of aloesin [72].

4.2. Immunomodulatory Effects of A. vera Gel and Its Components

4.2.1. Immunomodulatory Effects of A. vera Gel

Most of the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Aloe extracts are attributed to the gel and polysaccharides in the gel. In a study by Langmead et al., incubation with A. vera gel (AVG) of mucosal biopsies from patients with active ulcerative colitis reduced PGE2 release from the biopsies (Table 3) [54]. Additionally, they showed that AVG reduced IL-8 production in human colorectal cancer (Caco-2) cells at a select concentration, suggesting that AVG has anti-inflammatory effects. AVG was also able to reduce the production of cytokines TNF-α, TGF-β, and IL-6 in rats given a high-fat diet [55]. Furthermore, rats with acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer had lower serum TNF-α levels, and higher IL-10 levels compared to the untreated ulcer control. Gastric ulcer also resolved faster among the A. vera-fed rats than among the untreated rats.

Moreover, AVG was found to reduce LPS-induced cytokine (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and TNF-α) production in THP-1 cells and in primary human monocyte-derived macrophages [56]. Further investigation of underlying mechanisms for the effects of AVG on IL-1β suggested that AVG downregulated both pro-IL-1β and IL-1β in LPS-stimulated primary macrophages but did not appear to directly affect pro-IL-1β and IL-1β levels in the absence of LPS, suggesting that AVG only suppresses inflammation in the presence of stimulation and does not affect the baseline state. The effects of AVG on IL-1β may also be related to the downregulation of the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) sensor protein and the P2X7 receptor, which are both involved in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Notably AVG inhibited LPS-induced activation of NF-κB and kinases in the MAPK pathway, which are both involved in the recognition of LPS by TLR4. These findings suggest that the attenuation of LPS-induced increases in IL-1β and other pro-inflammatory cytokines by AVG may be mediated by the NF-κB or the MAPK pathway. If, indeed, NF-κB is affected by AVG, then downstream inflammatory responses (Figure 2) may be affected.

Several in vivo studies further support AVG-induced reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-17A) in the presence of various stimuli (e.g., LPS, bacteria, and pesticides) or in different inflammatory conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis, arthritis, and ulcer in rodents) (Table 3) [57,58,59,73,74]. Interestingly, some studies also reported increased production of IL-10, which is involved in the resolution of inflammation [60,73]. Thus, AVG may not only attenuate inflammation through the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines but may also accelerate the shift from the pro-inflammatory immune state to a recovering immune state.

Freeze-dried A. vera inner leaf gel (AVH200) reduced the activation and proliferation of T cells in a dose-dependent manner [61]. However, it did not trigger significant apoptosis among activated T cells, suggesting that activation of the apoptotic pathway is not the underlying mechanism for the effects of AVH200 on T cells. AVH200 also reduced cytokine secretion (IL-2, IL-5, and IL-17A) in T cells, which may be a consequence of reduced T cell proliferation. Additionally, the effects of the inner leaf gel on T cell proliferation were superior to the effects of A. vera extract, indicating that the active component is predominantly in the inner leaf gel. Notably, A. vera extract alleviated symptoms of inflammatory bowel syndrome in two small randomized-controlled studies, further indicating the anti-inflammatory effects of A. vera components [75].

Taken together, AVG appears to have immunosuppressive effects in the presence of stimuli or in the inflammatory disease state, suggesting a potential for application in viral diseases characterized by hyper-inflammatory responses. The mechanisms and pathways involved in the immunomodulatory effects of AVG and their direct effects on the viral disease state will have to be determined in future studies.

4.2.2. Immunomodulatory Effects of Acemannan and A. vera Polysaccharides

As opposed to the observed immunosuppressive effects of AVG, a number of immunostimulatory effects have been reported for ACM (Table 3) (Figure 2). Womble and Helderman reported that ACM promoted CTL genesis and improved their capacity to destroy target cells [62]. ACM also enhanced monocyte activity in response to alloantigen, which may contribute to the CTL antiviral response. Moreover, ACM was reported to enhance macrophage activation in response to IFN-γ stimulation, which may indicate a favorable antiviral immune response [63].

In the absence of stimulation, ACM was also able to induce cytokine (IL-6 and TNF-α) and NO release in macrophages. Similarly, ACM activated NO production in chicken spleen cells and chicken macrophages, with indications that the effects may be mediated by a receptor for terminal mannose [64]. This was further supported by the ability of modified APS, especially those within the 5–400 kDa range, to induce the maturation of RAW 264.7 cells [76]. Modified APS also promoted the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and NO in the macrophages. In contrast, however, a separate group reported that the combination of ACM and IFN-γ caused NO-independent apoptosis in RAW 264.7 macrophages, and that the combination downregulated B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) at the mRNA level [77]. The mechanisms underlying the effects of ACM on NO production remain unclear and will have to be elucidated further. Regardless, macrophages are involved in the clearance of virus-infected cells. Thus, ACM may promote the antiviral immune state.

Moreover, ACM was discovered to be mitogenic to mouse splenocytes [65]. It also stimulated the differentiation and maturation of DCs from mouse blood monocytes. However, mannose did not inhibit the effects of ACM on DCs, suggesting that these effects did not involve mannose-binding receptors.

Some groups have put forward the idea that components of Aloe gel, including polysaccharides, may exhibit either immunostimulatory or immunosuppressive effects, likely depending on purity, size, composition, or concentration of the gel or the compound [76,78]. Further studies using purified and characterized APS and ACM will have to be performed to elucidate the specific immunomodulatory activity of each compound. Additionally, based on the studies we presented here, the immune-related pathways targeted by ACM are so far unknown. More mechanistic studies on the immunomodulatory effects of ACM especially in the context of viral diseases will have to be performed so that its immunomodulating capacity can be maximized for clinical application.

4.2.3. Aloe Compounds as Viral Vaccine Adjuvants

Adjuvants are additional vaccine components that enhance the magnitude, breadth, and durability of immune responses to vaccines. Although a number of adjuvants are licensed for use with certain vaccines, safer alternatives that stimulate antiviral immune responses are still desired. For instance, alum, the most commonly used adjuvant in human viral vaccines elicits a TH2-biased immune response needed to manage helminthic parasites instead of stimulating TH1 immune responses required to combat most viral infections. Given the immunomodulatory effects of Aloe components, especially Aloe polysaccharides such as ACM, Aloe compounds may be considered as adjuvants for viral vaccines (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjuvanticity of A. vera components in viral vaccines.

The viral vaccine adjuvant potential of ACM was first reported by Chinnah wherein subcutaneous administration of ACM with a combination vaccine for NDV vaccine, infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), and infectious bronchitis in chickens raised protective antibody titers to NDV [79]. However, no enhancement of humoral immune responses to IBDV was observed, indicating that the adjuvanticity of ACM is antigen-dependent and ACM cannot be used as vaccine adjuvant for all viruses. Oral administration of AVG was reported to promote anti-sheep red blood cell antibody production in mice [85]. ACM has also been shown to raise anti-coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) antibody titers in mice, although it did not ameliorate myocarditis arising from CVB3 infection [80]. Oral administration of processed Aloe gel (PAG) in mice also elevated HA antibody and virus neutralizing titers against homologous and heterologous IAV strains [81]. Moreover, oral PAG enhanced the protectivity of IAV antigen and vaccines against homologous and heterologous challenge, although the effects were not as dramatic as those of commercially available adjuvants. High levels of neutralizing antibody titers are considered correlates of immunity and protectivity for vaccines against several viruses [86]. The ability of AVG or ACM to enhance the humoral immune response indicate an enhancement of immune responses that may be relevant to vaccine protectivity, suggesting their potential as adjuvants.

Furthermore, A. vera compounds have been reported to stimulate cell-mediated immunity and influence the direction of the T cell immune response. In addition to increasing IgA, IgG, and IgM levels following vaccination against myxomatosis virus in rabbits, oral administration of APS also increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts in vaccinated rabbits [82]. Notably, the administration of the combination of AVG and alum with a human papillomavirus (HPV16 E7d) vaccine increased the levels of TH1 cytokines IFN-γ and IL-4 in mice [83]. AVG alone (without vaccine) also increased the production IFN-γ and IL-4. Furthermore, AVG enhanced the effects of Montanide, an adjuvant known to enhance TH1 immune responses to vaccines, as indicated by elevated IgG2 titers following vaccination with HPV16 E7d. Although the study did not show the effects of AVG alone with the vaccine, the findings of this study suggest that adding AVG to an existing adjuvanted vaccine promotes a shift to a TH1 immune response, which is important in controlling viral infections. Whether the combination of AVG with an unadjuvanted viral vaccine promotes the TH1 immune response should be investigated further.

Although a number of animal studies indicate the viral vaccine adjuvant potential of AVG, we only know of one exploratory trial in humans so far. Oral intake of PAG (8 weeks) that overlapped with quadrivalent influenza vaccination (week 4) did not significantly increase vaccine seroprotectivity among healthy adults [84]. However, the geometric mean fold increase in antibody titers among patients at 4 weeks post-vaccination relative to baseline was significantly higher in the PAG group than in the placebo group. Furthermore, patients in the PAG arm reported lower rates of upper respiratory tract infection than those in the placebo arm, indicating that PAG may have increased the protectivity of the quadrivalent vaccine against symptomatic influenza infection. Cell-mediated immunity following influenza virus vaccination has been correlated with disease protection and cross-protection [87]; however, markers for cellular immunity were not evaluated in this study. The effects of PAG on the cell-mediated immunity conferred by the quadrivalent influenza vaccine will have to be evaluated to provide a clear understanding of the adjuvant potential of PAG. Additionally, the optimal route of administration and dose of PAG or its components for human applications require further investigation.

Taken together, compounds from A. vera have the ability to enhance the immunity and protectivity conferred by viral vaccines. The breadth of the adjuvant activity (e.g., target viruses) of the A. vera compounds should be determined in vivo.

5. Hurdles to Applying Aloe Compounds in Preventing and Managing Viral Diseases

As with other natural products, the clinical applicability of compounds from Aloe is complicated by poor product standardization and limitations to industrial-scale production. For example, the polysaccharide and phenolic content of Aloe spp. are highly variable and are easily affected by both biotic and abiotic factors [3]. Compound compositions of Aloe spp. generally differ based geographic origin, temperatures, climate, and variant, making harvest from direct plant sources difficult to replicate across multiple locations and various seasons [88]. The composition of the extracts and the sizes of polysaccharides are further affected by differences in treatment and extraction procedures. Moreover, even when farming, harvesting, and extraction conditions have been standardized, industrial-scale production of some of the compounds is often not feasible if plants are used as direct sources owing to low yield from individual plants [89]. Full synthesis, semi-synthesis, or bioengineering may be needed to achieve the desired amounts of compounds, especially the phenolics, for wide-scale clinical application. This requires research legwork to determine which metabolic pathways in microorganisms can be altered to produce the desired compound.

Another hurdle is the low bioavailability of Aloe phenolics, especially AEM and aloin. Aloe anthraquinones have also been reported to exhibit toxic effects in vitro and in vivo. These problems can be solved by optimization of the core structure of the compounds to improve their pharmacological and safety profiles. Compounds with low bioavailability can also be encapsulated using lipid-based delivery systems.

Lastly, most of the work we have presented here are still at early stages of pre-clinical exploration. For antiviral effects in particular, most studies on Aloe compounds remain in vitro and have little information on targets in viral replication cycles. Meanwhile, in the case of Aloe polysaccharides, the composition of Aloe polysaccharides (e.g., size range) are not well-defined such that different studies report contradicting results [81]. Characterization of isolated Aloe compounds and more mechanistic studies are needed to understand how the pharmacological activities of Aloe compounds can be maximized for application in viral disease prevention and management.

6. Conclusions

Here, we presented evidence that various compounds from Aloe, especially from A. vera, can be used as (1) direct antivirals for viral clearance; (2) immunomodulators for late viral disease management; and (3) vaccine adjuvants for viral disease prevention. However, most of these studies are still at early exploration stages. More characterization, mechanistic, and in vivo studies in the context of viral diseases are needed to understand the full potential of compounds from Aloe. Additionally, some of the Aloe compounds, especially the phenolics, are subject to the same issues as phenolics from other plants: low bioavailability and toxicity, which limit their clinical applicability. Optimization of these compounds should be considered. Furthermore, standardization of compound extraction procedures especially for Aloe polysaccharides will have to be ensured for industrial production. Overall, more research is needed to see these compounds further along the drug development pipeline. However, despite these issues, Aloe compounds contribute chemical and structural diversity to the current repertoire of candidate compounds for the fight against viral diseases. With the increasing frequency of viral disease emergence, all resources, whether natural or synthetic, should be given weight and developed pharmaceutically to improve our readiness for future viral outbreaks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-K.K.; investigation, E.E., J.K. and J.-K.K.; writing–original draft preparation: E.E.; writing–review and editing, J.-K.K. and J.K; supervision and project administration, J.-K.K.; funding acquisition, J.-K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by a Korea University Grant (KUS Innovative Research Fellowship).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in this article.

Acknowledgments

The graphical abstract and Figure 2 were created with BioRender.com, accessed on 27 April 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meganck, R.M.; Baric, R.S. Developing therapeutic approaches for twenty-first-century emerging infectious viral diseases. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitalia, V.C.; Munawar, A.H. A painful lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic: The need for broad-spectrum, host-directed antivirals. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautié, E.; Russo, O.; Ducrot, P.; Boutin, J.A. Unraveling Plant Natural Chemical Diversity for Drug Discovery Purposes. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.I.; Sheikh, W.M.; Rather, M.A.; Venkatesalu, V.; Muzamil Bashir, S.; Nabi, S.U. Medicinal plants: Treasure for antiviral drug discovery. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 3447–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maan, A.A.; Nazir, A.; Khan, M.K.I.; Ahmad, T.; Zia, R.; Murid, M.; Abrar, M. The therapeutic properties and applications of Aloe vera: A review. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjushe, A.; Vasani, R.; Saple, D.G. Aloe vera: A short review. Indian J. Dermatol. 2008, 53, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, M.H.; Laxmipriya, N.P. Evaluation of biological properties and clinical effectiveness of Aloe vera: A systematic review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2015, 5, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saoo, K.; Miki, H.; Ohmori, M.; Winters, W.D. Antiviral Activity of Aloe Extracts against Cytomegalovirus. Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydiskis, R.J.; Owen, D.G.; Lohr, J.L.; Rosler, K.H.; Blomster, R.N. Inactivation of enveloped viruses by anthraquinones extracted from plants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 2463–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zandi, K.; Zadeh, M.; Sartavi, K.; Rastian, Z. Antiviral activity of Aloe vera against herpes simplex virus type 2: An in vitro study. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waihenya, R.K.; Mtambo, M.M.A.; Nkwengulila, G. Evaluation of the efficacy of the crude extract of Aloe secundiflora in chickens experimentally infected with Newcastle disease virus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 79, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Peng, P.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Ma, Y.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y. Aloe extract inhibits porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in vitro and in vivo. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 249, 108849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.C.; Kim, Y.W.; Ryu, S.; Lee, A.; Lee, J.-S.; Song, M.J. Suppression of norovirus by natural phytochemicals from Aloe vera and Eriobotryae Folium. Food Control 2017, 73, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alla, H.I.; Abu-Gabal, N.S.; Hassan, A.Z.; El-Safty, M.M.; Shalaby, N.M. Antiviral activity of Aloe hijazensis against some haemagglutinating viruses infection and its phytoconstituents. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2012, 35, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatthaar-Saalmüller, B.; Fal, A.M.; Schönknecht, K.; Conrad, F.; Sievers, H.; Saalmüller, A. Antiviral activity of an aqueous extract derived from Aloe arborescens Mill. against a broad panel of viruses causing infections of the upper respiratory tract. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, P.; Fal, A.M.; Jambor, J.; Michalak, A.; Noster, B.; Sievers, H.; Steuber, A.; Walas-Marcinek, N. Candelabra Aloe (Aloe arborescens) in the therapy and prophylaxis of upper respiratory tract infections: Traditional use and recent research results. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 163, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutin, F.; Clewer, H.W.B. XCIX.—The constituents of rhubarb. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1911, 99, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chihara, T.; Shimpo, K.; Beppu, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Kaneko, T.; Wakamatsu, K.; Sonoda, S. Effects of Aloe-emodin and Emodin on Proliferation of the MKN45 Human Gastric Cancer Cell Line. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 3887–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, D.O.; Weber, N.D.; Wood, S.G.; Hughes, B.G.; Murray, B.K.; North, J.A. In vitro virucidal activity of selected anthraquinones and anthraquinone derivatives. Antivir. Res. 1991, 16, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Wu, C.-F.; Hsiao, N.-W.; Chang, C.-Y.; Li, S.-W.; Wan, L.; Lin, Y.-J.; Lin, W.-Y. Aloe-emodin is an interferon-inducing agent with antiviral activity against Japanese encephalitis virus and enterovirus 71. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 32, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimaneni, S.; Kumar, A. Abscisic acid and aloe-emodin against NS2B-NS3A protease of Japanese encephalitis virus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 8759–8766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-W.; Tsai, F.-J.; Tsai, C.-H.; Lai, C.-C.; Wan, L.; Ho, T.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Chao, P.-D.L. Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Isatis indigotica root and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, M.K.; Al-Dosari, M.S.; Alam, P.; Rehman, M.; Alajmi, M.F.; Alqahtani, A.S. The anti-hepatitis B virus therapeutic potential of anthraquinones derived from Aloe vera. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2960–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-T.; Hung, C.-Y.; Hseih, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-S.; Velu, A.B.; He, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-L.; Chen, T.-A.; Chen, T.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; et al. Effect of aloin on viral neuraminidase and hemagglutinin-specific T cell immunity in acute influenza. Phytomedicine 2019, 64, 152904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, D.S.; Pérez-Fons, L.; Estepa, A.; Micol, V. Membrane-related effects underlying the biological activity of the anthraquinones emodin and barbaloin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Argáez, R.; Chan-Balan, R.; Cetina-Montejo, L.; Ayora-Talavera, G.; Sansores-Peraza, P.; Gómez-Carballo, J.; Cáceres-Farfán, M. In vitro evaluation of anthraquinones from Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) roots and several derivatives against strains of influenza virus. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 132, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yu, C.; Wang, W.; Yu, G.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wei, K. Aloe Polysaccharides Inhibit Influenza A Virus Infection—A Promising Natural Anti-flu Drug. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlon, J.B.; Kemp, M.C.; Yawei, N.; Carpenter, R.H.; Shannon, W.M.; McAnalley, B.H. In vitro evaluation of the synergistic antiviral effects of acemannan in combination with azidothymidine and acyclovir. Mol. Biother. 1991, 3, 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, K.M.; Rosenberg, L.J.; Harris, C.K.; Bronstad, D.C.; King, G.K.; Biehle, G.A.; Walker, B.; Ford, C.R.; Hall, J.E.; Tizard, I.R. Pilot study of the effect of acemannan in cats infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1992, 35, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheets, M.A.; Unger, B.A.; Giggleman, G.F., Jr.; Tizard, I.R. Studies of the effect of acemannan on retrovirus infections: Clinical stabilization of feline leukemia virus-infected cats. Mol. Biother. 1991, 3, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rolta, R.; Yadav, R.; Salaria, D.; Trivedi, S.; Imran, M.; Sourirajan, A.; Baumler, D.J.; Dev, K. In silico screening of hundred phytocompounds of ten medicinal plants as potential inhibitors of nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of COVID-19: An approach to prevent virus assembly. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 7017–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Y.; You, L.; Yin, X.; Fu, J.; Ni, J. Aloe-emodin: A review of its pharmacology, toxicity, and pharmacokinetics. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şeker Karatoprak, G.; Küpeli Akkol, E.; Yücel, Ç.; Bahadır Acıkara, Ö.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. Advances in Understanding the Role of Aloe Emodin and Targeted Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 7928200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groom, Q.J.; Reynolds, T. Barbaloin in aloe species. Planta Med. 1987, 53, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, D.S.M.; Ho, J.; Wills, S.; Kawall, A.; Sharma, A.; Chavada, K.; Ebert, M.C.C.J.C.; Evoli, S.; Singh, A.; Rayalam, S.; et al. Aloin isoforms (A and B) selectively inhibits proteolytic and deubiquitinating activity of papain like protease (PLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-Y.; Kwon, H.-J.; Sung, M.-K. Plasma, tissue and urinary levels of aloin in rats after the administration of pure aloin. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2008, 2, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akao, T.; Che, Q.M.; Kobashi, K.; Hattori, M.; Namba, T. A purgative action of barbaloin is induced by Eubacterium sp. strain BAR, a human intestinal anaerobe, capable of transforming barbaloin to aloe-emodin anthrone. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 19, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Final Report on the Safety Assessment of Aloe andongensis Extract, Aloe andongensis Leaf Juice, Aloe arborescens Leaf Extract, Aloe arborescens Leaf Juice, Aloe arborescens Leaf Protoplasts, Aloe barbadensis Flower Extract, Aloe barbadensis Leaf, Aloe barbadensis Leaf Extract, Aloe barbadensis Leaf Juice, Aloe barbadensis Leaf Polysaccharides, Aloe barbadensis Leaf Water, Aloe ferox Leaf Extract, Aloe ferox Leaf Juice, and Aloe ferox Leaf Juice Extract. Int. J. Toxicol. 2007, 26, 1–50. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Mei, N. Aloe vera: A review of toxicity and adverse clinical effects. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2016, 34, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Yates, K.M.; Tizard, I.R. Aloe polysaccharides. In Aloes: The Genus Aloe; Reynolds, T., Ed.; CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hamman, J.H. Composition and applications of Aloe vera leaf gel. Molecules 2008, 13, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rai, K.R.; Shrestha, P.; Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Maarouf, M.; Chen, J.-L. Acute Infection of Viral Pathogens and Their Innate Immune Escape. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 672026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, B.T.; Sehrawat, S. Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: What decides the outcome? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, S.N.; Rouse, B.T. Immune responses to viruses. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Lan, Z.; Ye, J.; Pang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Qin, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, P. Cytokine Storm: The Primary Determinant for the Pathophysiological Evolution of COVID-19 Deterioration. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 589095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancanelli, M.J.; Huang, S.X.L.; Luthra, P.; Garner, H.; Itan, Y.; Volpi, S.; Lafaille, F.G.; Trouillet, C.; Schmolke, M.; Albrecht, R.A.; et al. Infectious disease. Life-threatening influenza and impaired interferon amplification in human IRF7 deficiency. Science 2015, 348, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stertz, S.; Hale, B.G. Interferon system deficiencies exacerbating severe pandemic virus infections. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.S.; Yu, F.S.; Chan, J.K.; Li, T.M.; Lin, S.S.; Chen, S.C.; Hsia, T.C.; Chang, Y.H.; Chung, J.G. Aloe-emodin affects the levels of cytokines and functions of leukocytes from Sprague-Dawley rats. In Vivo 2006, 20, 505–509. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.-Y.; Kwon, H.-J.; Sung, M.-K. Evaluation of Aloin and Aloe-Emodin as Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Aloe by Using Murine Macrophages. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, A.D.; Panchal, P.V.; Harle, U.N.; Nanda, R.K.; Shaikh, H.M. Anti-Inflammatory and Antiarthritic Activity of Anthraquinone Derivatives in Rodents. Int. J. Inflam. 2014, 2014, 690596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xian, M.; Cai, J.; Zheng, K.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Liang, S.; Wang, S. Aloe-emodin prevents nerve injury and neuroinflammation caused by ischemic stroke via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and NF-κB pathway. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 8056–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-W.; Yang, T.-C.; Lai, C.-C.; Huang, S.-H.; Liao, J.-M.; Wan, L.; Lin, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-W. Antiviral activity of aloe-emodin against influenza A virus via galectin-3 up-regulation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 738, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.-Y.; Kwon, H.-J.; Sung, M.-K. Dietary aloin, aloesin, or aloe-gel exerts anti-inflammatory activity in a rat colitis model. Life Sci. 2011, 88, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, L.; Makins, R.J.; Rampton, D.S. Anti-inflammatory effects of Aloe vera gel in human colorectal mucosa in vitro. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 19, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdani, N.; Hossini, S.E.; Edalatmanesh, M.A. Anti-inflammatory Effect of Aloe vera Extract on Inflammatory Cytokines of Rats Fed with a High-Fat Diet (HFD). Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2021, 17, e114323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budai, M.M.; Varga, A.; Milesz, S.; Tőzsér, J.; Benkő, S. Aloe vera downregulates LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine production and expression of NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 56, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, N.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, S.M. Protective effect of Aloe vera on polymicrobial sepsis in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Modak, D.; Chattaraj, S.; Nandi, D.; Sarkar, A.; Roy, J.; Chaudhuri, T.K.; Bhattacharjee, S. Aloe vera gel homogenate shows anti-inflammatory activity through lysosomal membrane stabilization and downregulation of TNF-α and Cox-2 gene expressions in inflammatory arthritic animals. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, K.; Lkhagva-Yondon, E.; Kim, M.; Lim, Y.R.; Shin, E.; Lee, C.K.; Jeon, M.S. Oral treatment with Aloe polysaccharide ameliorates ovalbumin-induced atopic dermatitis by restoring tight junctions in skin. Scand. J. Immunol. 2020, 91, e12856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Z.; Femenia, A.; Núñez-Jinez, G.; Salazar Zúñiga, M.N.; Cano, M.E.; Espino, T.; Knauth, P. In vitro Immunomodulatory Effect of Food Supplement from Aloe vera. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2019, 2019, 5961742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahluwalia, B.; Magnusson, M.K.; Isaksson, S.; Larsson, F.; Öhman, L. Effects of Aloe barbadensis Mill. extract (AVH200®) on human blood T cell activity in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womble, D.; Helderman, J.H. The Impact of Acemannan on the Generation and Function of Cytotoxic T-Lymphocytes. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 1992, 14, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Tizard, I.R. Activation of a mouse macrophage cell line by acemannan: The major carbohydrate fraction from Aloe vera gel. Immunopharmacology 1996, 35, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, K.; Sharma, J.M.; Nordgren, R. Nitric oxide production by chicken macrophages activated by Acemannan, a complex carbohydrate extracted from Aloe vera. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1995, 17, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Lee, M.K.; Yun, Y.-P.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, K.; Han, S.S.; Lee, C.-K. Acemannan purified from Aloe vera induces phenotypic and functional maturation of immature dendritic cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001, 1, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Rahbar, R.; Chan, R.W.; Lee, S.M.; Chan, M.C.; Wang, B.X.; Baker, D.P.; Sun, B.; Peiris, J.S.; Nicholls, J.M.; et al. Influenza virus non-structural protein 1 (NS1) disrupts interferon signaling. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, S.B.; Yoon, H.J.; Chang, C.Y.; Koh, H.S.; Jeon, S.H.; Park, E.J. Galectin-3 exerts cytokine-like regulatory actions through the JAK-STAT pathway. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7037–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, N.; Ren, A.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao George, F.; Cleary, P.; Wang, B. Influenza viral neuraminidase primes bacterial coinfection through TGF-β–mediated expression of host cell receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denney, L.; Branchett, W.; Gregory, L.G.; Oliver, R.A.; Lloyd, C.M. Epithelial-derived TGF-β1 acts as a pro-viral factor in the lung during influenza A infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seo, S.H.; Webster, R.G. Tumor necrosis factor alpha exerts powerful anti-influenza virus effects in lung epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Bel, M.; Brunet, A.; Gosselin, J. Leukotriene B4, an Endogenous Stimulator of the Innate Immune Response against Pathogens. J. Innate Immun. 2014, 6, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, B.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Raj, H.G.; Prasad, A.K.; Eycken, E.V.D.; Parmar, V.S.; Ghosh, B. A chromone analog inhibits TNF-α induced expression of cell adhesion molecules on human endothelial cells via blocking NF-κB activation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 2952–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eamlamnam, K.; Patumraj, S.; Visedopas, N.; Thong-Ngam, D. Effects of Aloe vera and sucralfate on gastric microcirculatory changes, cytokine levels and gastric ulcer healing in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Pereira, M.D.; Siddiqi, N.J.; Sharma, B. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Potential of Aloe vera on the Cartap and Malathion Mediated Toxicity in Wistar Rats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, B.; Magnusson, M.K.; Isaksson, S.; Larsson, F.; Öhman, L. Aloe barbadensis Mill. extract improves symptoms in IBS patients with diarrhoea: Post hoc analysis of two randomized double-blind controlled studies. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211048133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, S.-A.; Oh, S.-T.; Song, S.; Kim, M.-R.; Kim, D.-S.; Woo, S.-S.; Jo, T.H.; Park, Y.I.; Lee, C.-K. Identification of optimal molecular size of modified Aloe polysaccharides with maximum immunomodulatory activity. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2005, 5, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamoorthy, L.; Tizard, I.R. Induction of Apoptosis in a Macrophage Cell Line RAW 264.7 by Acemannan, a β-(1,4)-Acetylated Mannan. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998, 53, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadgrove, N.J.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Pharmacodynamics of Aloe vera and acemannan in therapeutic applications for skin, digestion, and immunomodulation. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6572–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnah, A.D.; Baig, M.A.; Tizard, I.R.; Kemp, M.C. Antigen dependent adjuvant activity of a polydispersed β-(1,4)-linked acetylated mannan (acemannan). Vaccine 1992, 10, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauntt, C.J.; Wood, H.J.; McDaniel, H.R.; McAnalley, B.H. Aloe polymannose enhances anti-coxsackievirus antibody titres in mice. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.-J.; Españo, E.; Nam, J.-H.; Kim, J.; Shim, K.-S.; Shin, E.; Park, Y.I.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, J.-K. Adjuvanticity of Processed Aloe vera gel for Influenza Vaccination in Mice. Immune Netw. 2020, 20, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, G.; Taghavi, M.; Maleki, A.K.; Habibian, R. The effect of Aloe vera extract on humoral and cellular immune response in rabbit. Afr. J. Biotechnol. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 5225–5228. [Google Scholar]

- Nikookalam, M.; Salehian, Z.; Mirzaee, S.; Ajideh, R.; Mahdavi, M.; Yazdi, M. Aloe Vera Extracted Polysaccharides Shift the Immune Responses of Tumor Bearing Mice Toward Th1 Pattern: Animal Study. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2019, 16, 12148–12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Oh, M.R.; Hwang, J.H.; Choi, E.K.; Jung, S.J.; Song, E.J.; Españo, E.; Webby, R.J.; Webster, R.G.; Kim, J.K.; et al. Effect of processed Aloe vera gel on immunogenicity in inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine and upper respiratory tract infection in healthy adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bałan, B.J.; Niemcewicz, M.; Kocik, J.; Jung, L.; Skopińska-Różewska, E.; Skopiński, P. Oral administration of Aloe vera gel, anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory herbal remedy, stimulates cell-mediated immunity and antibody production in a mouse model. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 39, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plotkin, S.A. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sridhar, S. Heterosubtypic T-Cell Immunity to Influenza in Humans: Challenges for Universal T-Cell Influenza Vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baruah, A.; Bordoloi, M.; Deka Baruah, H.P. Aloe vera: A multipurpose industrial crop. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Orhan, I.E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J.M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; Bayer, E.A.; et al. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).