Abstract

Fluorescent carbon dots (CDs) were efficiently synthesized by a one-step microwave-assisted method using diphenylamine as a carbon precursor. The obtained CDs exhibit high stability and strong water solubility. Under UV irradiation, these CDs could emit bright green photoluminescence. These synthesized CDs have an average diameter of 1.8 nm (±0.46) and quantum yield (QY) as high as 44.69% using rhodamine-B as a reference. The CDs’ intensity can be quantitatively quenched by Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions with high sensitivity and low LOD about 9.58 nM and 22.27 nM, respectively, indicating that the CDs sensors can be potentially applied for Hg2+ and Fe3+ detection in aqueous solutions.

1. Introduction

As a category of zero-dimensional carbon-based nanomaterials, carbon dots (CDs) have been widely applied in chemosensing, photocatalysis, bioimaging, and many applications due to their excellent stability, biocompatibility, and optoelectronic properties [1]. CDs are generally known to be discrete, quasi-spherical particles with sizes below 10 nm, have a conjugated core (sp2) superposed by functional groups such as aldehyde, carboxyl, ketone, etc., which depends on the nature of the carbon resource material used to prepare the CDs [2]. CDs possess unique optical properties such as excellent photoluminescence, tunable fluorescence, as well as low toxicity, chemical inertness, good biocompatibility, and the ability to undergo photoinduced electron transfer [3,4,5]. CDs are a new category of zero-dimensional fluorescent nanomaterials that consist of conjugated carbon nuclei and surface functional groups mainly composed of elements C, H, and O doped with heteroatoms B, N, S, F, P, and Cl [6,7,8]. CDs can be synthesized through a number of approaches, which mainly include top-down and bottom-up methods [4,9]. The top-down technique is breaking down the larger carbon materials to the nanoscale using methods like electrochemical oxidation, ultrasonic synthesis, laser ablation, and arc discharge [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Generally, these methods require long processing times, harsh conditions, and expensive equipment. Conversely, bottom-up methods known as building CDs from starting material such as biowastes, phenyldiamine, citric acid, or glucose using techniques like hydrothermal carbonization, chemical oxidation, combustion, pyrolysis, and microwave-assisted synthesis [10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Bottom-up synthesis offers better control of size, composition, and fewer imperfections compared to top-down methods [10]. Among these techniques, the microwave-assisted method has emerged as a highly efficient and eco-friendly technique for CDs synthesis [25,26,27,28,29]. This approach involves rapid heating of carbon-rich precursors such as biowaste using microwave irradiation, which enhances carbonization and improves product yield [30]. The reaction parameters, such as irradiation time, microwave power, and precursor concentration, influence the optical and morphological properties of the produced CDs [31]. CDs have become outstanding materials in the development of fluorescent chemosensors for heavy metal ion detection due to their unique photoluminescent properties, high surface area, and tunable surface functionalization [32,33,34,35]. The heavy metal ions interact with the surface groups of CDs, leading to fluorescence quenching or enhancement changes [36].

On the other hand, heavy metal ions are essential for maintaining human health because many biological functions depend on the presence of these ions, and many enzymes require these elements for their catalytic reactions [29]. Mercury is a neurotoxin impacting both humans and animals, particularly Hg2+, which is the most stable form of mercury [37]. It is commonly recognized that the excessive release of mercury ions not only endangers the ecological environment but also leads to serious damage to human health through direct absorption and bioaccumulation through food chains. People are likely to be exposed to higher mercury doses under specific and non-specific conditions when using mercury-containing ingredients, such as traditional medicine or cosmetic skin products. Accidental exposure can be possible when air and water pollution, and home mercury spills occur [37].

Iron is an essential element in the environment and exists mainly in two oxidation states: Ferrous (Fe2+) and Ferric (Fe3+). While iron is important for biological processes such as oxygen transport and enzymatic reactions, its presence in water with high concentrations can pose significant hazards. Excess iron can lead to contamination of drinking water. More significantly, high iron concentrations may raise the growth of iron bacteria, which can block the water systems and contribute to the formation of biofilms, potentially harboring pathogenic microorganisms [38]. High levels of iron in water can cause immediate harmful effects on health, such as organ damage and gastrointestinal irritation. However, it can interact with other contaminants like arsenic, making it easier for them to be released and raising the risk of contamination [39].

Pollutant detection in aquatic environments is one of the most significant applications of CDs, and researchers are currently conducting many studies on this unique material to develop its properties in order to use it in many fields. This study aims to develop a fluorescent chemosensor using a simple and effective microwave-assisted method and use it to detect Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions in aquatic environments with low LOD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Orthophosphoric acid, mercury (II) nitrate hydrate, sodium thiosulphate pentahydrate, silver nitrate, strontium chloride, lead nitrate, cadmium nitrate, and iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate were purchased from BDH Chemicals Ltd. (Poole, England). Diphenylamine, zinc sulfate heptahydrate, lanthanum (III) nitrate hydrate, sodium chromate, magnesium chloride, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate was purchased from Philip Harris, nickel sulfate from Lobachemie, and ferric chloride anhydrous from SRL (Mumbai, India). Hydrochloric acid was purchased from Honeywell (Seelze, Germany). All chemicals used are of analytical grade and as received without any further purification. Deionized water was used in all experiments prepared in the laboratory using the (PURELAB) instrument (UK).

2.2. Instrumentation

A microwave oven from Nikai (20 Liter 700 W with Auto Menu Function| Model No. NMO515N8NX) (China) was used. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded at room temperature using an FTIR spectrometer from Perkin Elmer (Shelton, Connecticut, USA), and the UV-vis absorption spectra were obtained using a spectrophotometer from Thermo Scientific (Shelton, Connecticut, USA). The PL emission spectrum was measured using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer from Agilent (Santa Clara, California, United States). A pH meter from JENWAY (United Kingdom) was used for pH measurements. TEM-EDS with a specimen quick-change holder (EM-11210SOCH) from JEOL Ltd. (Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) was used to provide morphological and elemental analysis.

2.3. Synthesis of CDs

An amount of 0.50 g of diphenylamine was added to 10 mL of phosphoric acid and dissolved using stirring and heating until completely dissolved. They were mixed and then placed in a microwave-safe container and heated in a microwave oven at ~119 °C for 20–25 min (until the solution turns dark). The dark solution was then dialyzed to produce CDs (Scheme 1). CDs were diluted to 500.00 mg L−1 for use as a sensor, since it can retain sufficient fluorescence intensity for sensing. Lower concentrations (such as 250.00 mg L−1) may reduce signal intensity, while higher concentrations (such as 1000.00 mg L−1) could lead to aggregation or self-quenching [40].

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation for preparation of CDs.

2.4. Detection of Hg2+ and Fe3+

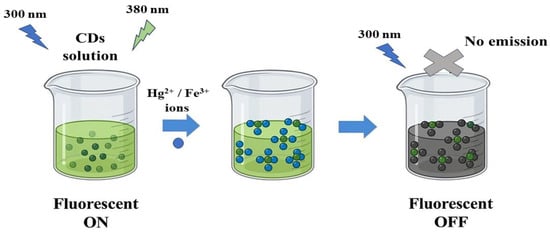

The selectivity of Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions was performed by adding other metal-ion solutions: (Na+, Ag+, Zn2+, Cr6+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Cd2+, La3+, Pb2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Sr2+ and Mg2+) in a similar way. Stock solutions (50.00 μM) were prepared to study the selectivity of the CDs towards the heavy metal ions. Then, standard solutions with different concentrations (5.00, 10.00, 50.00, 100.00, 150.00, 200.00, 400.00, 600.00, 800.00, and 1000.00 μM) of the selected heavy metal ions, which showed quenching effect, were prepared to study their behavior and interactions with the CDs. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Scheme 2 illustrates the quenching process by Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions.

Scheme 2.

Schematic representation for the quenching of CDs intensity by Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions.

2.5. Measurement of Fluorescence Quantum Yield (QY)

The QY of CDs was calculated using the following equation:

where

= Quantum yield, I = Intensity, = Refractive index, = Absorption, and R subscript represents the fluorescence reference of known quantum results. Rhodamine-B (aqueous solution, ΦR = 0.31) was used as a reference. The CDs were dissolved in deionized water (η = 1.33) as preparation for the measurements.

2.6. Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOC) Estimation

LOD = 3.3 σ/s and LOC = 10 σ/s, where σ and s are related to the blank sample’s standard deviation and slope of the S-V plot, respectively.

2.7. Relative Fluorescence Change (F − F0)/F0

The fluorescence response of the prepared CDs to heavy metal ions was quantitatively assessed by measuring the relative change in fluorescence intensity, which is defined as (F − F0)/F0, where F0 represents the initial fluorescence intensity in the absence of target heavy metal ions, and F is the fluorescence intensity in the presence of heavy metal ions. This relative fluorescence change is a key metric for evaluating the selectivity of sensors towards heavy metal ions, as significantly different (F − F0)/F0 values for various metal ions indicate a sensor’s ability for a specific metal detection. A sensor with high selectivity will show a large (F − F0)/F0 change for its target metal and a small change for other non-target ions. This change can have positive or negative values:

- Fluorescence Enhancement: In some cases, the metal ion can cause an “on–off” fluorescence response, where the fluorescence increases. In this case, F > F0, and (F − F0)/F0 becomes a positive value.

- Fluorescence Quenching: When a metal ion interacts with a sensor, it can quench the sensor’s fluorescence intensity. This leads to a decrease in F0 value, making (F − F0)/F0 a negative value. (Common in heavy metal ion detection).

2.8. F/F0

The F/F0 ratio provides a direct measurement of fluorescence intensity changes. It is commonly used in fluorescent sensor studies to quantify changes in the intensity relative to the initial intensity.

2.9. Relative Fluorescence Intensity (F0 − F)/F0

A relative fluorescence intensity plot quantifies the change in fluorescence signal relative to the initial intensity, often used to measure the impact of an analyte on a fluorescent probe. This plot indicates the fractional decrease in fluorescence and is commonly used in sensor development to determine analyte concentrations or changes in environmental conditions.

2.10. Stern–Volmer Plot

The Stern–Volmer equation is:

where [Q] is the quencher concentration and KSV is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant, representing the efficiency of quenching. This ratio allows the evaluation of quenching efficiency, elucidation of quenching mechanisms (static or dynamic), and quantification of analyte–quencher interactions, which will provide key parameters for sensor performance.

F0/F = 1 + KSV [Q]

2.11. Benesi–Hildbrand Plot

The Benesi–Hildebrand (B-H) plot is a graphical method used to determine the stoichiometry and equilibrium constant (binding constant) of host–guest complexes, or other non-bonded interactions, by analyzing changes in fluorescence intensity. Y-axis (1/(F0 − F)) represents the inverse of the change in the observed fluorescence intensity upon complex formation. X-axis (1/[Q]) represents the inverse of the concentration of the guest molecule (heavy metal ions), which is added to the host (CDs). The linear plot confirms the assumption of a 1:1 stoichiometry and allows for the calculation of the association constant (K), which represents the strength of the interaction between the molecules from the intercept and slope. A nonlinear plot indicates that the interaction is not a simple 1:1 complex and suggests the formation of a 1:2 or higher-order complex.

2.12. Study of CD Stability

2.12.1. pH Stability

HCl and NaOH were used to prepare CD solutions with different pH values ranging from 2 to 13. Fluorescence intensities were measured after 15 min.

2.12.2. Thermal Stability

To study the thermal stability, the temperature of the CD solutions was adjusted between 20 and 100 °C. The fluorescence intensity was measured immediately after the CD solutions reached the desired temperature.

2.12.3. Storage Time Stability

CD solutions were stored in tightly closed containers at room temperature to prevent contamination, aggregation, or changes in properties.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of CDs

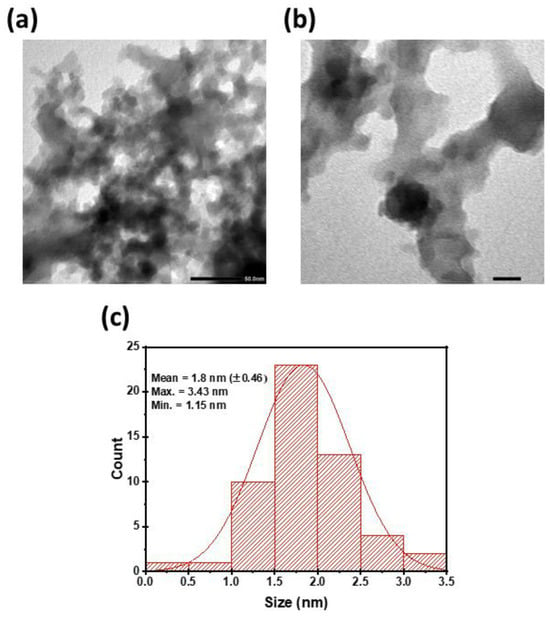

To evaluate the particle size distribution of the prepared CDs, TEM analysis was applied. Figure 1a,b showed that the CDs have an average diameter of 1.80 (±0.46 nm). The size range extended from 1.15 nm to 3.43 nm as demonstrated in Figure 1c, which indicates a relatively narrow distribution and good uniformity. These findings suggest the synthetic approach produces CDs with consistent dimensions, which is helpful for applications that require nanomaterials with a uniform size.

Figure 1.

TEM image of CDs at (a) 50.00 nm, (b) 20.00 nm; (c) particle size distribution.

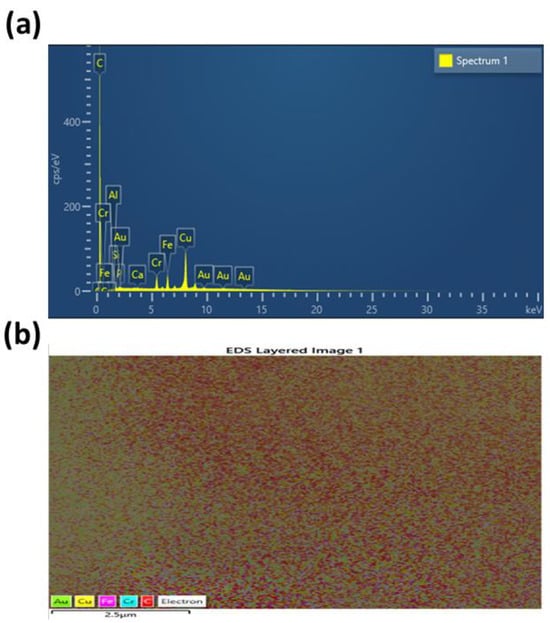

The EDS technique has been applied to obtain the elemental composition of the synthesized CDs, as shown in Figure 2a. The obtained findings illustrated that carbon was the dominant component (70.65 wt%) with a minor phosphorus contribution (0.29 wt%) corresponding to phosphorus doping using o-phosphoric acid. Other elements have values of: Al 0.20%, Si 0.42%, Ca 0.21%, Cr 4.32%, Fe 5.43%, Cu 16.50%, and Au 1.98%. The Au signal results from gold coating applied prior to EDS analysis, while metallic element residues reflect environmental and instrumental influences rather than compositional features of the precursors. Generally, the EDS analysis confirms successful preparation of carbon-rich, phosphorus-functionalized CDs.

Figure 2.

(a) EDS and (b) mapping analysis of the prepared CDs.

The EDS layered mapping analysis in Figure 2b demonstrates the spatial distribution of elemental species within the carbon dot sample. Each color represents a specific element as indicated in the legend. The dominant red coloration observed across the mapped area indicates a homogeneous distribution of carbon, which is consistent with the formation of carbon dots. Minor signals from Au, Cu, Fe, and Cr, marked by their respective colors, result from either substrate background, sample holder, or possible trace residues from reagents and synthesis vessels. This mapping confirms the successful synthesis of CDs with a uniform elemental composition. The presence of carbon as the continuous phase affirms that the CDs are well dispersed without significant aggregation or phase separation. The spatial homogeneity is further corroborated by the lack of distinct clusters, ensuring consistent fluorescence behavior throughout the sample. Although nitrogen appears in FTIR analysis, it often does not appear in EDS analysis due to its low atomic number, which results in weak X-ray emissions that are easily absorbed by the detector window or surface contamination. In addition, nitrogen must be present above a certain concentration (around 2.00% by mass) to be detected, and this makes its EDS detection unreliable for low levels in many samples [41].

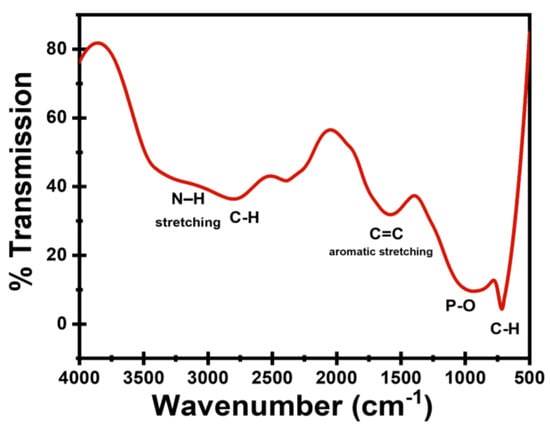

FTIR spectrum of the as-prepared CDs in Figure 3 showed a medium prominent band at 715 cm−1 contributed to aromatic C–H out-of-plane bending or P–O bending modes. There is a fairly strong peak at ~1000 cm−1 attributed to P–O/P=O/P–O–C vibrations and C–O (ether/ester) stretches, P–O vibrations given owing to the use of o-phosphoric acid. A high moderate peak at ~1600 cm−1 is assigned to C=C aromatic stretching. A medium to moderate peak at 2810 cm−1 is attributed to aliphatic C–H stretching. Finally broad and shallow peak at 3000–3400 cm−1 suggests hydroxyls (surface OH) and possible amine N–H stretching (from Diphenylamine).

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrum of the prepared CDs.

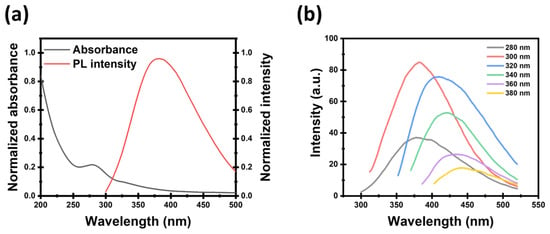

The optical properties of the prepared CDs were characterized by UV-Vis and PL intensity, as shown in Figure 4a. The absorbance spectrum exhibits a distinct peak at 280 nm, indicating the characteristic electronic transitions in the CDs. The corresponding PL intensity spectrum, recorded with excitation at 280 nm, shows an emission peak centered around 380 nm, confirming the strong photoluminescent property of the CDs under UV excitation [42]. Also, it displays the PL intensity peak of CDs. Excitation-dependent emission has been illustrated by the prepared CDs, suggesting that the fluorescent/luminescent wavelength can be changed by varying the excitation wavelength. Figure 4b shows the emission PL spectra of CDs, with different excitation wavelengths within the range from 280 to 380 nm.

Figure 4.

(a) Absorption and PL intensity spectrum of CDs. (b) Emission PL spectrum at different exciting wavelengths.

The QY of the prepared CDs was calculated to be 44.69%. This value is significantly higher compared to CDs in the previous studies (Table 1), which proves the high efficiency of the microwave-assisted technique. This high value suggests that the adopted approach enables effective surface passivation of the CDs, which makes them suitable for different applications in sensing and bioimaging.

Table 1.

Comparison of QY of CDs produced from different precursors in previous studies and this work.

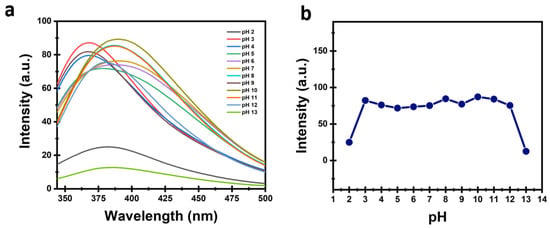

3.2. Stability of CDs

The stability of CDs is one of the significant parameters for employing them in sensing applications. Thus, the pH stability of the CDs was studied over a broad pH range (pH 2–13) as shown in Figure 5. The PL intensity of the prepared CDs exhibited remarkable stability in a wide pH range (4–11), while a notable decrease in PL intensity was observed under strongly acidic (pH 2) and basic (pH 12–13) conditions. This behavior can be attributed to the protonation and deprotonation of surface functional groups such as COOH, OH, and NH2. At lower pH, protonation of these groups introduces non-radiative recombination pathways, which result in PL intensity quenching. Conversely, in highly basic conditions, deprotonation changes the surface charge and may promote partial aggregation, also reducing the PL intensity. The slight shift in emission wavelength observed with pH variation arises from modifications in the surface state energy levels, which affect the electronic transitions responsible for emission. Generally, the CDs demonstrate excellent PL stability over a broad pH range, indicating robust surface passivation and stable optical properties, and significant potential of the CDs in several applications.

Figure 5.

(a,b) PL intensity stability of CDs at different values of pH.

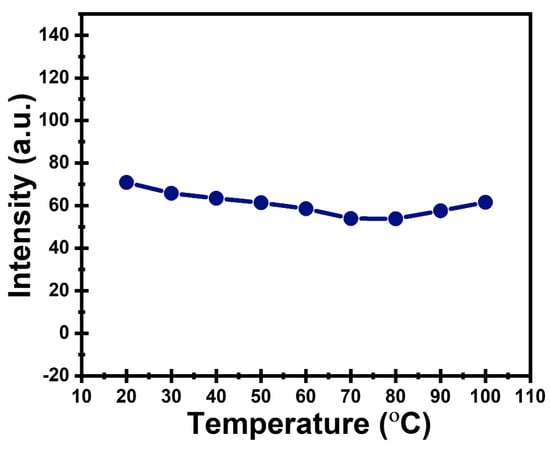

The PL intensity of the prepared CDs gradually decreased with increasing temperature (Figure 6), indicating typical thermal quenching behavior. The PL intensity of the prepared CDs gradually decreased with increasing temperature, indicating typical thermal quenching behavior. This decrease is attributed to enhanced non-radiative relaxation processes such as phonon-assisted recombination, which become more pronounced at higher temperatures and compete with radiative emission. In addition, elevated temperatures may slightly disturb the surface passivation of the CDs, allowing charge carriers to escape from emissive surface states, thus reducing fluorescence efficiency. Generally, the CDs exhibit good thermal stability, maintaining consistent emission characteristics within a broad temperature range [51].

Figure 6.

Temperature-dependent PL intensity of CDs.

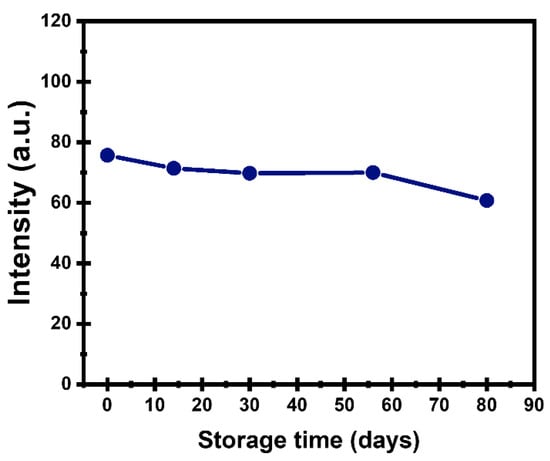

According to Figure 7, the PL intensity of the prepared CDs retained approximately 80% of its original value after 80 days of storage, indicating good storage stability under the studied conditions.

Figure 7.

PL intensity of CDs stored at room temperature.

3.3. Selectivity of CDs Toward Hg2+ and Fe3+

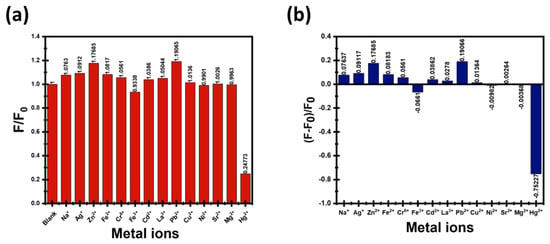

As illustrated in Figure 8a, the CDs’ fluorescence intensity could be significantly quenched by Hg2+ and Fe3+ compared with the other metal ions. Figure 8b illustrates the fluorescence response of CDs in the presence of different metal ions at = 380 nm. The ratio (F − F0)/F0 is commonly used to quantify the relative change in the CDs’ fluorescence intensity when metal ions are introduced. This value represents the fractional change in fluorescence and is particularly helpful for comparing the sensitivity and selectivity of CDs with different metal ions. A negative value indicates fluorescence quenching (decrease in intensity), like Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions. The positive value indicates fluorescence enhancement (increase in intensity). Here, the (F − F0)/F0 was calculated for each metal ion. As shown, Hg2+ induced the most significant quenching, with a value of −0.752, and Fe3+ with a value of −0.066. While other ions exhibited no quenching effect.

Figure 8.

(a) Histogram of CDs intensity with several metal ions; (b) Fluorescence response of CDs in the presence of different metal ions.

Diphenylamine-derived CDs contain nitrogen-rich surface functionalities from the precursor itself, which facilitate strong ligand-to-metal interactions with Hg2+ and Fe3+. The presence of nitrogen or other heteroatoms on the surface of CDs improves binding affinity due to coordination chemistry principles, leading to selective and sensitive quenching responses [52]. Due to their nanoscale size and high surface area, they have more accessible active sites for metal ions. Furthermore, the eco-friendly and facile synthesis methods preserve these surface functional groups and dopants, thereby enhancing their sensing performance. Fundamentally, the high sensitivity and selectivity of these CDs arise from the combination of surface functional groups capable of selective coordination, intrinsic doping that adjusts their electronic properties, and optimized fluorescence characteristics that respond strongly to Hg2+ and Fe3+ binding. These factors together yield CDs compatible for rapid and sensitive detection of these toxic metal ions in aqueous environments.

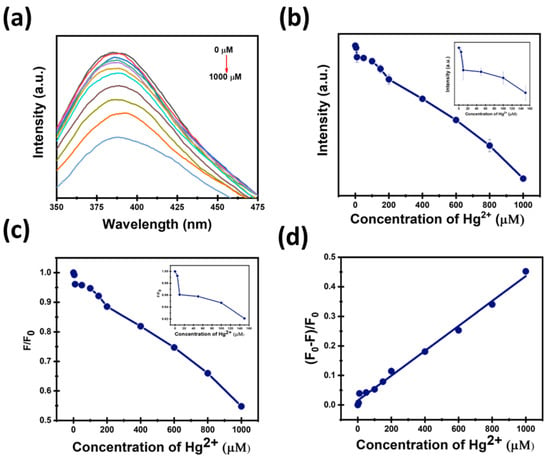

3.4. Sensitivity of CDs Toward Hg2+

As shown in Figure 9a,b, the intensity of CDs decreases by adding Hg2+ with increasing concentrations. In Figure 9c, the addition of Hg2+ ions to the CDs solution leads to a clear concentration-dependent decrease in F/F0 ratio, indicative of fluorescence quenching. The quenching efficiency was quantitatively analyzed to investigate how the CDs fluorescence is quenched by the addition of Hg2+ ions, using the plot of (F0 − F)/F0 versus Hg2+ concentration shown in Figure 9d. This plot exhibited an excellent linear relationship within the concentration range with R2 = 0.99. The linearity indicates a direct proportional Hg2+ ions quenching effect on the CDs intensity, which enables a reliable quantification and suggests a well-defined interaction mechanism between Hg2+ ions and the CDs surface.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Effect of different concentrations of Hg2+ on the intensity of CDs; (c) The ratio of fluorescence intensity to Hg2+ concentration (μM); (d) Quenching efficiency.

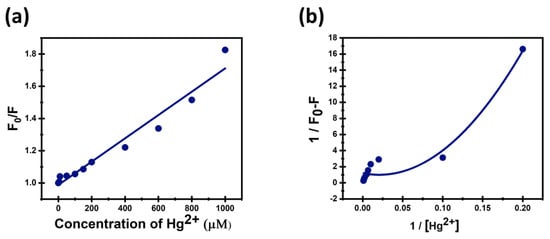

The linear increase in the Stern–Volmer plot of (F0 − F) versus concentration of Hg2+ (Figure 10a) indicates a concentration-dependent quenching of CDs’ fluorescence that follows the classical Stern–Volmer relationship:

Figure 10.

(a) Stern–Volmer quenching plot and (b) 1:2 Benesi–Hildbrand plot for CDs with Hg2+.

Ksv was obtained from the slope of the S-V plot and found to be equal to 7.23 M−1. The linear S-V plot with R2 = 0.96 suggests that the quenching mechanism predominantly involves dynamic quenching, where the quencher molecules collide with the excited fluorophores, causing a non-radiative deactivation proportional to quencher concentration. The LOD was estimated to be 0.009 μM, and the LOC was equal to 0.029 μM.

The determined LOD value of the present sensor demonstrates competitive sensitivity toward Hg2+ ions compared to other recent fluorescent sensors reported in the literature (Table 2). While several advanced sensors achieve slightly lower detection limits around 0.27–6.00 nM, the 9.58 nM LOD is notably lower than many others exhibiting detection limits in nanomolar to micromolar ranges. Therefore, the sensor exhibits reliable low-nanomolar sensitivity, suitable for environmental monitoring and practical applications.

Table 2.

Different sensors based on CDs for Hg2+ detection.

The Benesi–Hildbrand plot displayed in Figure 10b, and the binding constant was calculated for 1:2 stoichiometry. The Benesi–Hildebrand plot shows nonlinear behavior with 1:2 stoichiometry, and a high correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.96) indicates that the fluorescence quenching proceeds from the formation of a complex containing one fluorophore bound to two quencher molecules. This suggests a more complex binding interaction than the simple 1:1, which can reflect stronger and multiple binding sites. Good fitting supports the assumption of this higher-order complexation contributing to the observed fluorescence quenching [59].

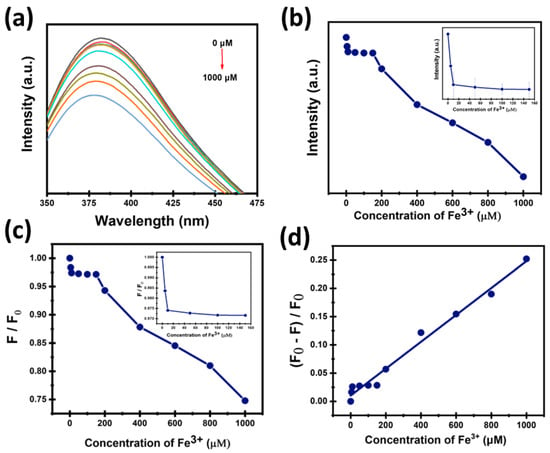

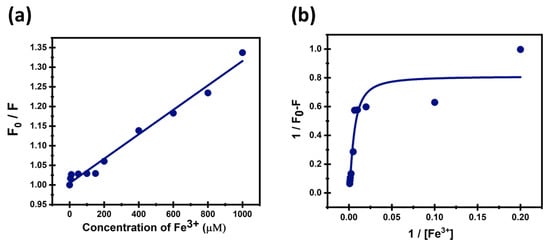

3.5. Sensitivity of CDs Toward Fe3+

Figure 11a,b show that the intensity of CDs decreases gradually with the increase of Fe3+ concentration. In Figure 11c, the fluorescence quenching efficiency of CDs by the addition of Fe3+ ions was quantitatively estimated by plotting the F/F0 versus Fe3+ concentration. It was noted that the F/F0 value decreased with the increase of Fe3+ concentration, indicating efficient quenching by Fe3+ ions. Quenching efficiency was studied to analyze how the fluorescence of CDs is quenched with Fe3+ ions by plotting (F0 − F)/F0 versus Fe3+ concentration shown in Figure 11d. This plot demonstrates a strong linear relationship with R2 = 0.98. The strong linearity indicates a directly proportional quenching effect of Fe3+ ions on the intensity of CDs, allowing reliable quantification, and suggests a well-defined interaction mechanism between Fe3+ ions and the surface of CDs.

Figure 11.

(a,b) The relationship between the CDs’ fluorescence intensity and Fe3+ concentration; (c) The ratio of fluorescence intensity to concentration (μM); (d) Linear relationship between the quenching efficiency of CDs and Fe3+ concentration.

The linear increase in the S-V plot (Figure 12a) indicates a concentration-dependent quenching of CDs’ fluorescence that follows the classical S-V relationship and has a KSV value equal to 3.11 M−1. This strong linearity is characteristic of a well-defined quenching process and supports the suitability for the detection of Fe3+ ions by the synthesized CDs. The LOD and LOC were calculated to be 0.02 μM and 0.07 μM, respectively. Moreover, LOD of the prepared CDs sensors were compared with literature in Table 3.

Figure 12.

(a) Stern–Volmer plot and (b) Benesi–Hildbrand plot of CDs with Fe3+ ions.

Table 3.

Different sensors based on CDs for Fe3+ detection.

The LOD of the diphenylamine-derived CDs for Fe3+ ion detection was calculated to be 22.27 nM. The table above illustrates their high sensitivity compared to many previously reported sensors. These values are significantly lower than the micromolar LODs exhibited by several conventional CDs (Such as 1.90 μM and 3.80 μM) and are superior to many other CDs, which display LODs ranging from 162.00 nM down to 13.80 nM. The relatively wide linear detection ranges up to 1000.00 μM further demonstrate their practical applicability for environmental and analytical Fe3+ monitoring. Compared with other sensors, the presented sensors show a noticeable improvement in sensitivity. This enhanced performance can be attributed to the tailored surface chemistry that facilitates the efficient fluorescence quenching by Fe3+ ions.

Figure 12b shows a B-H plot that has a 1:2 stoichiometry, nonlinear behavior, and a relatively good correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.89), proving that the quenching emerges from the complex formation, which contains one fluorophore bound to two quencher molecules. This suggests a more complex binding interaction, which might reflect stronger and more multiple binding sites. Further studies should be conducted to gain a deeper understanding of fluorescence quenching mechanisms and to study the binding interactions and pathways involved at the molecular level. Detailed mechanistic insights will help to optimize sensor design and sensitivity. Moreover, investigating potential interferences and sensor behaviors will provide robustness for real-world applications.

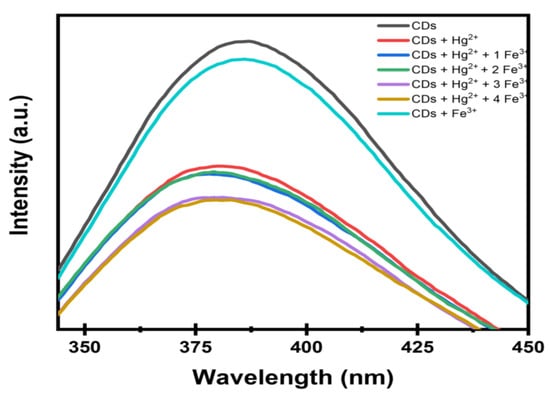

3.6. Simultaneous Detection of Hg2+ and Fe3+

The interference plot shows that Hg2+ produces a strong and distinct quenching of the intensity of CDs, indicating high sensitivity. As shown in Figure 13, Fe3+ causes only a gradual additional decrease; however, at higher concentrations, it partially masks the Hg2+ response. Therefore, in real samples containing large excess Fe3+, the Hg2+-induced quenching may not be distinguishable. This represents a practical limitation, and samples with high Fe3+ may require pretreatment or correction. In summary, Fe3+ ions demonstrated significant interference in the fluorescence detection of Hg2+ by the synthesized CDs, highlighting the need for a masking agent in practical sensing applications.

Figure 13.

Effect of Hg2+ detection in the presence of Fe3+ ions.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a rapid and facile microwave-assisted synthesis of CDs for efficient detection of Hg2+ and Fe3+ in aqueous solutions using o-diphenylamine as a carbon precursor. The prepared CDs show a high QY of 44.69%. These CDs provide sufficient sensitivity toward Hg2+ and Fe3+ ions with low LOD up to 9.58 nM and 22.27 nM, respectively. The excellent photostability, strong water solubility, and long storage time make these CDs useful in multiple applications, including bioimaging and sensing. Both Hg2+ and Fe3+ exhibit dynamic (collisional) quenching as the primary fluorescence quenching mechanism, evidenced by linear Stern–Volmer plots. Nonlinear Benesi–Hildebrand plots indicate that static quenching via ground-state complex formation does not adequately describe their interaction, suggesting alternative binding mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.K.; methodology, R.H.A. and L.R.A.; validation, E.M.B. and K.A.; formal analysis, R.H.A. and S.B.K.; investigation, E.M.B. and K.A.; resources, S.B.K.; data curation, R.H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.A.; writing—review and editing, E.M.B., L.R.A., K.A. and S.B.K.; supervision, E.M.B. and S.B.K.; funding acquisition, E.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Z. Green synthesis of nitrogen-doped carbon dots from Pueraria residues for use as a sensitive fluorescent probe for sensing Cr(VI) in water. Sensors 2025, 25, 5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S.K.; D’Souza, A.; Suhail, B. Blue light-emitting carbon dots (CDs) from a milk protein and their interaction with Spinacia oleracea leaf cells. Int. Nano Lett. 2019, 9, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Ren, X.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Xia, L. Carbon dots: Synthesis, properties and applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, A.; Ushakova, E.; Rogach, A.L. Chiral carbon dots: Synthesis, optical properties, and emerging applications. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Ge, J.; Liu, W.; Niu, G.; Jia, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, P. Tunable multicolor carbon dots prepared from well-defined polythiophene derivatives and their emission mechanism. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travlou, N.A.; Giannakoudakis, D.A.; Algarra, M.; Labella, A.M.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Bandosz, T.J. S- and N-doped carbon quantum dots: Surface chemistry dependent antibacterial activity. Carbon 2018, 135, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, Z.M.; Labudova, M.; Danko, M.; Matijasevic, D.; Micusik, M.; Nadazdy, V.; Kovacova, M.; Kleinova, A.; Spitalsky, Z.; Pavlovic, V. Highly efficient antioxidant F-and Cl-doped carbon quantum dots for bioimaging. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16327–16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Duan, W.; Song, W.; Liu, J.; Ren, C.; Wu, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, H. Red emission B, N, S-co-doped carbon dots for colorimetric and fluorescent dual mode detection of Fe3+ ions in complex biological fluids and living cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 12663–12672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, V.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Ganapathy, D. Recent advances on synthesis and potential applications of carbon quantum dots. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 906838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirlou-Miavagh, F.; Rezvani-Moghaddam, A.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H.; Sundararaj, U. Comparative study of synthesis of carbon quantum dots via different routes: Evaluating doping agents for enhanced photoluminescence emission. Prog. Org. Coatings 2024, 191, 108445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; Ettoumi, F.; Javed, M.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Shao, X.; Luo, Z. Ultrasonic-assisted green extraction of peach gum polysaccharide for blue-emitting carbon dots synthesis. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2021, 24, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xiong, M.; Zhang, J.; He, C.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Kuang, Y.; Yang, M.; Huang, Q. Carbon dots based on natural resources: Synthesis and applications in sensors. Microchem. J. 2021, 160, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cui, K.; Gong, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Z.; Hou, L.; Yuan, C. Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of N-doped, multicolor carbon dots toward fluorescent inks, fluorescence sensors, and logic gate operations. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao-Mujica, F.J.; Garcia-Hernández, L.; Camacho-López, S.; Camacho-López, M.; Camacho-López, M.A.; Reyes Contreras, D.; Pérez-Rodríguez, A.; Peña-Caravaca, J.P.; Páez-Rodríguez, A.; Darias-Gonzalez, J.G. Carbon quantum dots by submerged arc discharge in water: Synthesis, characterization, and mechanism of formation. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 163301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, A.; Hoffman, J.; Morgiel, J.; Mościcki, T.; Stobiński, L.; Szymański, Z.; Małolepszy, A. Luminescent carbon dots synthesized by the laser ablation of graphite in polyethylenimine and ethylenediamine. Materials 2021, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, G.; El-Deen, A.K.; Radwan, A.S.; Belal, F.; Elmansi, H. Ultrafast microwave-assisted green synthesis of nitrogen-doped carbon dots as turn-off fluorescent nanosensors for determination of the anticancer nintedanib: Monitoring of environmental water samples. Talanta Open 2025, 11, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.K.M.; Lim, G.K.; Leo, C.P. Comparison between hydrothermal and microwave-assisted synthesis of carbon dots from biowaste and chemical for heavy metal detection: A review. Microchem. J. 2021, 165, 106116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, M.; Hildebrandt, M.; Kuhnemuth, R.; Karg, M. Pyrolysis and solvothermal synthesis for carbon dots: Role of purification and molecular fluorophores. Langmuir 2022, 38, 6148–6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, L.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, P.; Jin, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Sun, X. Study on the fluorescence properties of carbon dots prepared via combustion process. J. Lumin. 2019, 206, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchudan, R.; Perumal, S.; Edison, T.N.J.I.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Vinodh, R.; Sangaraju, S.; Kishore, S.C.; Lee, Y.R. Natural nitrogen-doped carbon dots obtained from hydrothermal carbonization of chebulic myrobalan and their sensing ability toward heavy metal ions. Sensors 2023, 23, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayani, K.F.; Ghafoor, D.; Mohammed, S.J.; Shatery, O.B.A. Carbon dots: Synthesis, sensing mechanisms, and potential applications as promising materials for glucose sensors. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latief, U.; Ul Islam, S.; Khan, Z.M.S.H.; Khan, M.S. A facile green synthesis of functionalized carbon quantum dots as fluorescent probes for a highly selective and sensitive detection of Fe3+ ions. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 262, 120132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopalan, P.; Vidya, N. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of carbon dots derived from wild lemon (Citrus pennivesiculata) leaves as a fluorescent probe for tetracycline sensing in water. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 286, 122024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, R.B.; González, L.T.; Madou, M.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Martinez-Chapa, S.O.; Mendoza, A. Synthesis, purification, and characterization of carbon dots from non-activated and activated pyrolytic carbon black. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, M.; Hasan, M.; Wirjosentono, B.; Gani, B.A.; Nada, C.E. Microwave synthesis of carbon quantum dots from arabica coffee ground for fluorescence detection of Fe3+, Pb2+, and Cr3+. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 20571–20581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, J.; Sharma, H.; Dwivedi, C. Microwave-assisted synthesis of carbon quantum dots and their integration with TiO2 nanotubes for enhanced photocatalytic degradation. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 144, 111050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Yuan, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Green-light-emitting carbon dots via eco-friendly route and their potential in ferric-ion detection and WLEDs. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 7339–7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Zhang, M. Microwave-assisted synthesis of carbon dot—iron oxide nanoparticles for fluorescence imaging and therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 711534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, H.; Abe, M.; Sato, K.; Uwai, K.; Tokuraku, K.; Iimori, T. Microwave-assisted synthesis and formation mechanism of fluorescent carbon dots from starch. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 3, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, M.M. Thiamethoxam sensing using gelatin carbon dots: Influence of synthesis and purification methods. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Hong, S.; Ju, H. Carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, characteristics, and quenching as biocompatible fluorescent probes. Biosensors 2025, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; She, Y. Fluorescent enhanced endogenous carbon dots derived from green tea residue for multiplex detection of heavy metal ions in food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1431792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ji, X.; Liang, J.; Gao, Y.; Xing, H.; Song, Y.; Hou, J.; Yang, G. The fabrication of fluorescent sensor for Fe3+ detection and configurable logic gate operation based on N-doped carbon dots. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 449, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Q.; Sun, P.; Deng, Y.; Shen, G. One-step synthesis of highly fluorescent carbon dots as fluorescence sensors for the parallel detection of cadmium and mercury ions. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1005231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-J.; Ge, S.; Li, D.-Q.; Xu, Z.-Q.; Wang, E.-J.; Wang, S.-M. Fluorescent carbon dots for sensing metal ions and small molecules. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 50, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Landa, S.D.; Reddy Bogireddy, N.K.; Kaur, I.; Batra, V.; Agarwal, V. Heavy metal ion detection using green precursor derived carbon dots. iScience 2022, 25, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Jin, W.; Yin, Q.; Huang, J.; Huang, Z.; Fu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Zou, J.; Nie, J.; Zhang, Y. Ultrasensitive visual detection of Hg2+ ions via the Tyndall effect of gold nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2613–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, Z.; Sugiarti, S.; Rohaeti, E.; Batubara, I. Validation method of the cellulose triacetate-based optode membrane for Fe(III) detection in water samples. J. Kim. Sains dan Apl. 2025, 28, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Swaren, L.; Wang, W. Water decontamination by reactive high-valent iron species. Eco-Environ. Health 2024, 3, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarmathy, C.; Sudhaparimala, S. Carbon dots as selective fluorescent probes for metal ions-influence of Moringa oleifera leaf as a precursor. Int. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2023, 19, 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, V.C.G.; Limpoco, T.; Enriquez, E.P. Detection of nitrogen in layer-by-layer polymeric films by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Key Eng. Mater. 2022, 913, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Tan, J.K.S.; Mo, X.; Song, Y.; Lim, J.; Liew, X.R.; Chung, H.; Kim, S. Carbon quantum dots with tunable size and fluorescence intensity for development of a nano-biosensor. Small 2025, 21, e2404524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šafranko, S.; Janđel, K.; Kovačević, M.; Stanković, A.; Dutour Sikirić, M.; Mandić, Š.; Széchenyi, A.; Glavaš Obrovac, L.; Leventić, M.; Strelec, I.; et al. A facile synthetic approach toward obtaining N-doped carbon quantum dots from citric acid and amino acids, and their application in selective detection of Fe(III) ions. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, F.; Moukham, H.; Olia, F.; Piras, D.; Ledda, S.; Salis, A.; Stagi, L.; Malfatti, L.; Innocenzi, P. Highly photostable carbon dots from citric acid for bioimaging. Materials 2022, 15, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Cui, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Orange emissive N-doped carbon dots and their application in detection of water in organic solvents and the polyurethane composites. Opt. Mater. 2022, 123, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte De Assuncao, T.; Broussier, A.; Plain, J.; Proust, J. Unveiling the photoluminescence of carbon quantum dots with controlled cyan or green emission: Synthesis and photophysics investigation. ACS Appl. Opt. Mater. 2024, 2, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jin, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Jiao, L. A label-free yellow-emissive carbon dot-based nanosensor for sensitive and selective ratiometric detection of chromium (VI) in environmental water samples. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 248, 122912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ren, G.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Shen, J. Bioinspired carbon quantum dots for sensitive fluorescent detection of vitamin B12 in cell system. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1032, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandoss, S.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, M.R.; Velu, K.S.; Palanisamy, S.; You, S.; Kumar, A.J.; Lee, Y.R. Nitrogen and sulfur co-doped photoluminescent carbon dots for highly selective and sensitive detection of Ag+ and Hg2+ ions in aqueous media: Applications in bioimaging and real sample analysis. Environ. Res. 2023, 228, 115898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, H.; Li, H. Detection of Fe3+ and Hg2+ ions by using high fluorescent carbon dots doped with S and N as fluorescence probes. J. Fluoresc. 2022, 32, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, S.; Kumar, P.; Pani, B.; Kaur, A.; Khanna, M.; Bhatt, G. Stability of carbon quantum dots: A critical review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13845–13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhani, E.; Al Zbedy, A.S.; Alqarni, S.A.; Alzahrani, S.O.; Alharbi, A.; Alfi, A.A.; Al-Bonayan, A.M.; Shahat, A. Eco-friendly nanocellulose-based sensor for sensitive and selective detection of mercury and iron ions in water samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, K.; Suriyaprakash, R.; Shunmugakani, S.; Saravanan, P.; Kumar, J.V.; Mythili, R.; Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Santhamoorthy, M. Sequential detection of Hg2+ and TNT using a nitrogen-doped polymeric carbon dots on–off–on fluorescence sensor. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yan, H.; Li, H.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Liu, X. Carbon dots as specific fluorescent sensors for Hg2+ and glutathione imaging. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhu, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y. Fluorescent and colorimetric assay for determination of Cu(II) and Hg(II) using AuNPs reduced and wrapped by carbon dots. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Yoon, J.; Liu, S. Insight into mercury ion detection in environmental samples and imaging in living systems by a near-infrared fluorescent probe. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2024, 411, 135768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zou, T.; Wang, Z.; Xing, X.; Peng, S.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. The fluorescent quenching mechanism of N and S co-doped graphene quantum dots with Fe3+ and Hg2+ ions and their application as a novel fluorescent sensor. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tam, T.; Hong, S.H.; Choi, W.M. Facile synthesis of cysteine–functionalized graphene quantum dots for a fluorescence probe for mercury ions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 97598–97603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yu, Z. Validity and reliability of Benesi-Hildebrand method. Acta Phys.—Chim. Sin. 2007, 23, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, X.; Pan, W.; Yu, G.; Wang, J. Fe3+-sensitive carbon dots for detection of Fe3+ in aqueous solution and intracellular imaging of Fe3+ inside fungal cells. Front. Chem. 2020, 7, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, N.; Mousazadeh, M.H. Preparation of fluorescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots for highly selective on-off detection of Fe3+ ions in real samples. Opt. Mater. 2021, 121, 111515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Luo, Y.; Cui, C.; Han, Q.; Peng, Z. Carbon dots as multifunctional fluorescent probe for Fe3+ sensing in ubiquitous water environments and living cells as well as lysine detection via “on-off-on” mechanism. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 309, 123840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, C.; Garg, A.K.; Mathur, M.; Sonkar, S.K. Fluorescent polymer carbon dots for the sensitive–selective sensing of Fe3+ metal ions and cellular imaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 12699–12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mao, L.; Cui, C.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Nitrogen-doped carbon dots as fluorescent probes for sensitive and selective determination of Fe3+. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 316, 124347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Yang, H.; Gong, A.-J.; Huang, X.-M.; Li, L. Sensitive and selective chemosensor for Fe3+ detection using carbon dots synthesized by microwave method. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 334, 125907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Xu, G.; Hou, C.; Zhang, H. Ratiometric fluorescence nanoprobe based on nitrogen-doped carbon dots for Cu2+ and Fe3+ detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, W.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Cao, L.; Duan, L.; Tang, T.; Wang, Y. Green synthesis of boron-doped carbon dots from Chinese herbal residues for Fe3+ sensing, anti-counterfeiting, and photodegradation applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).