Condition Monitoring of In-Service DFIGs Working Under Non-Stationary Conditions via NsHOTA: A Motor Current Signature Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Harmonic Order Tracking Analysis (HOTA) Method

2.1. NsHOTA Steps

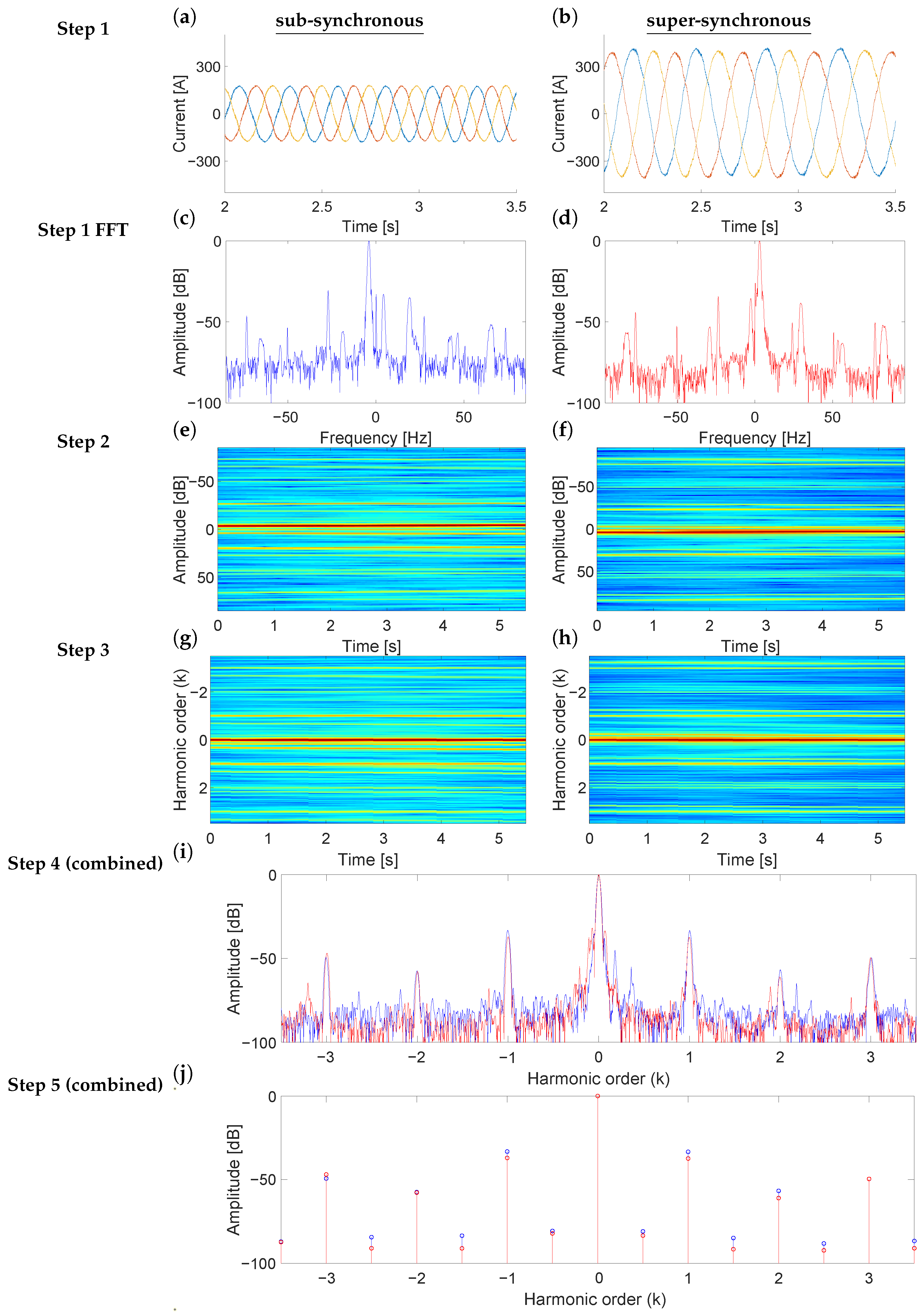

- Signal acquisition. The first step consists on acquiring the rotor-side converter currents for each phase (a, b, c). Figure 1a,b shows three -phase rotor current samples acquired with the WT DFIG operating at sub- and super-synchronous regimes, respectively. Figure 1c,d display the corresponding FFT spectra traditionally used for diagnosis. Note that the spectral distribution varies with the operating condition, requiring expert knowledge for interpretation and restricting analysis to steady-state periods.

- Park and Gabor transforms. The three-phase rotor currents are first expressed in their d–q components ( and ) using Park’s transform as Equations (3) and (4) [26]:The Park transformation projects the three-phase system into an orthogonal reference frame, removing redundant information and allowing more compact representation of the electrical behavior. Once the Park vector is obtained, the time–frequency analysis is performed using the Gabor transform [27], which provides the energy of the different fault components in the time–frequency plane. The Gabor transform is chosen for its high energy concentration and robustness to noise, enabling the processing of measurements acquired under non-steady conditions. This step is illustrated in Figure 1e,f. The combination of the Gabor transform and the Park transform in NsHOTA is motivated by their complementary roles in signal representation. The Park transform converts the three-phase quantities into a rotating reference frame where the modulus of the Park signal becomes DC (0 Hz). This operation decouples the analysis from the grid frequency and suppresses its possible fluctuations and leakage, ensuring that the fundamental does not interfere with the dynamic components of interest. Applying Gabor transform to the Park-domain signals further concentrates the spectral content around zero frequency, effectively reducing the bandwidth required for accurate representation. This compression allows the hardware front-end and acquisition systems to operate with lower sampling and filtering demands. Finally, performing the FFT on the Gabor-domain signals ensures spectral orthogonality.

- Re-scaling the frequency axis. Once the spectrogram is obtained, the next step consists in transforming the frequency axis so that the fault components appear at their corresponding harmonic order k, independently of the operating speed. For an eccentricity fault, the fault-related frequencies are given in Equation (2). To achieve a consistent representation, the time–frequency distribution is re-scaled for each time instant according to Equation (5):where is the transformed frequency corresponding to , and represents the main component in the spectrogram at time , identified as the frequency with the highest energy. The slip for each instant can be computed from the relationship between stator and rotor frequencies, as shown in Equation (6):In a DFIG connected to the grid, corresponds directly to the network frequency, which eliminates the need for a separate speed measurement. Consequently, the transformed frequency of order k can be expressed as Equation (7):Therefore, in the transformed spectrogram, all fault-related components are aligned at fixed harmonic order positions (k), regardless of variations in speed or load. This property allows a direct and consistent comparison of fault features, as illustrated in Figure 1g,h for the sub- and super-synchronous regimes, respectively.

- Averaging the harmonic energy. Since the fault components are aligned at fixed k-order positions regardless of the operating condition, their energy distribution can be conveniently condensed into a single representation. This new representation, referred to as the average HOTA spectrum, is analogous to the traditional steady-state spectrum (Figure 1c,d), but significantly easier to interpret. For each transformed frequency, the mean energy is calculated along the entire acquisition period, providing a compact summary of the fault-related information. Performing this compaction of the time-harmonic order space provides another important advantage: Any noise frequencies that are not perfectly aligned with the fault features throughout the time dimension are filtered out. Figure 1i illustrates this step.

- Improving the accuracy of fault features. To obtain a well-defined fault-feature space, this study incorporates an additional refinement based on selecting a window filter with appropriate time- and frequency-domain dimensions. The optimal window depends on the characteristics of the fault harmonics and corresponds to the Gabor window whose parameters are adjusted according to the slopes of the fault components to be detected. The methodology, thoroughly presented in [27], ensures maximum energy concentration in the time–frequency domain, approaching the limits imposed by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, and minimizes the entropy of the resulting time–frequency representation.Previous works established the baseline methodology: first, by adopting consensus window dimensions that produced time–frequency spaces of acceptable quality for fault detection [21], and later by introducing an iterative adjustment procedure based on the minimum-entropy criterion, which improved fault-identification accuracy [22]. These contributions form the stationary reference framework up to this point.Building on that foundation, the present study introduces a minor extension to account for transient effects, which were not considered in earlier stationary approaches. In this case, the minimum-entropy condition is explicitly sought by adjusting the window parameter within a range using a three-point binary search algorithm (Figure 2), reducing computational cost.

- Data reduction and transmission. After obtaining the average HOTA spectrum, the most relevant diagnostic information must be stored or transmitted to the control center for further analysis. To minimize data volume while preserving diagnostic accuracy, HOTA retains only the mean energy values corresponding to the main harmonic orders (k from to 3, including the main component) together with selected intermediate points. These approximately 15 values form the harmonic signature of the machine, which allows clear differentiation between fault-related components and background noise. The resulting k-Order values, shown in Figure 1j, can be directly compared with predefined thresholds to assess the presence or absence of faults. This compact representation facilitates quick and reliable diagnosis, even for non-specialized personnel.

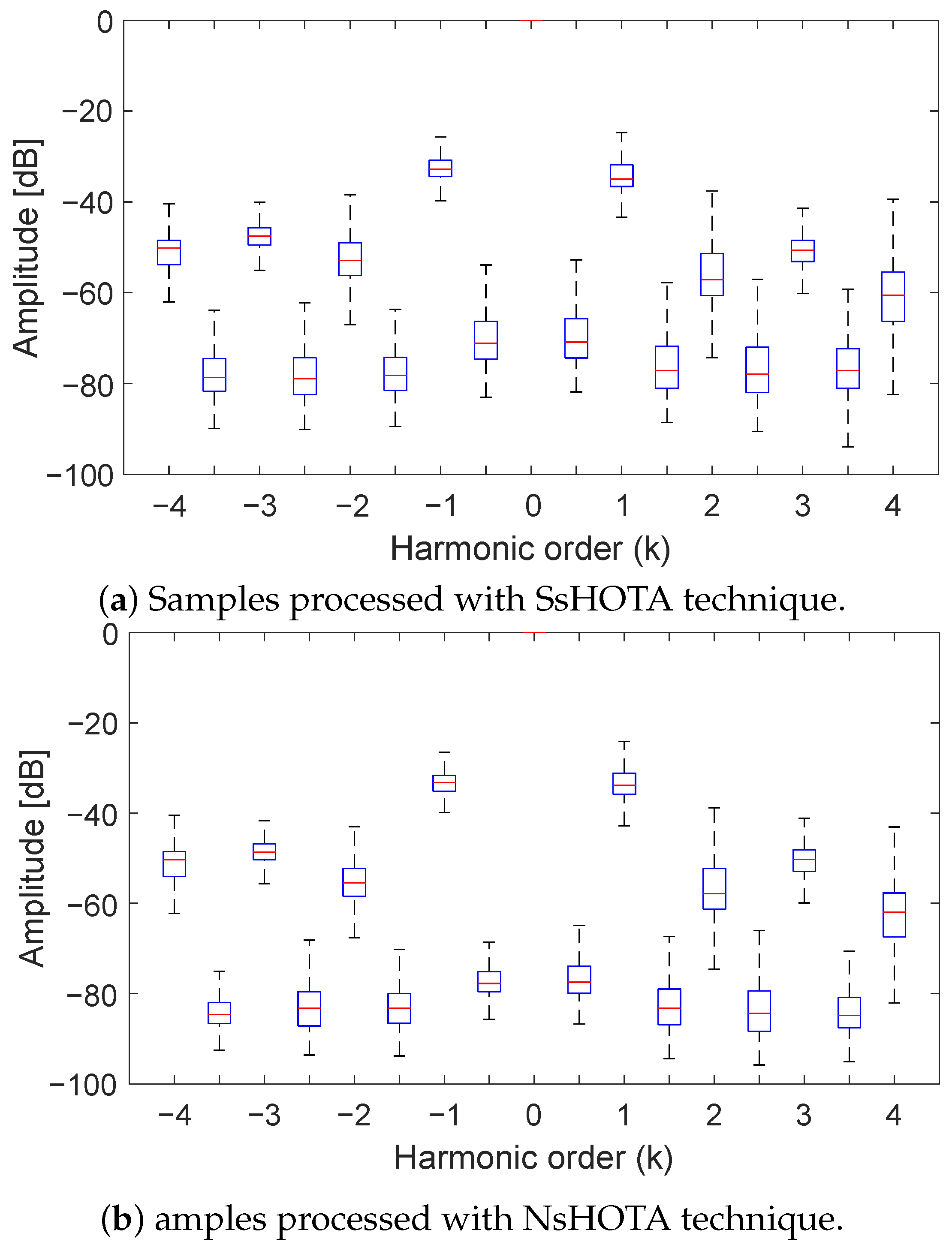

2.2. Improvements in NsHOTA vs. SsHOTA

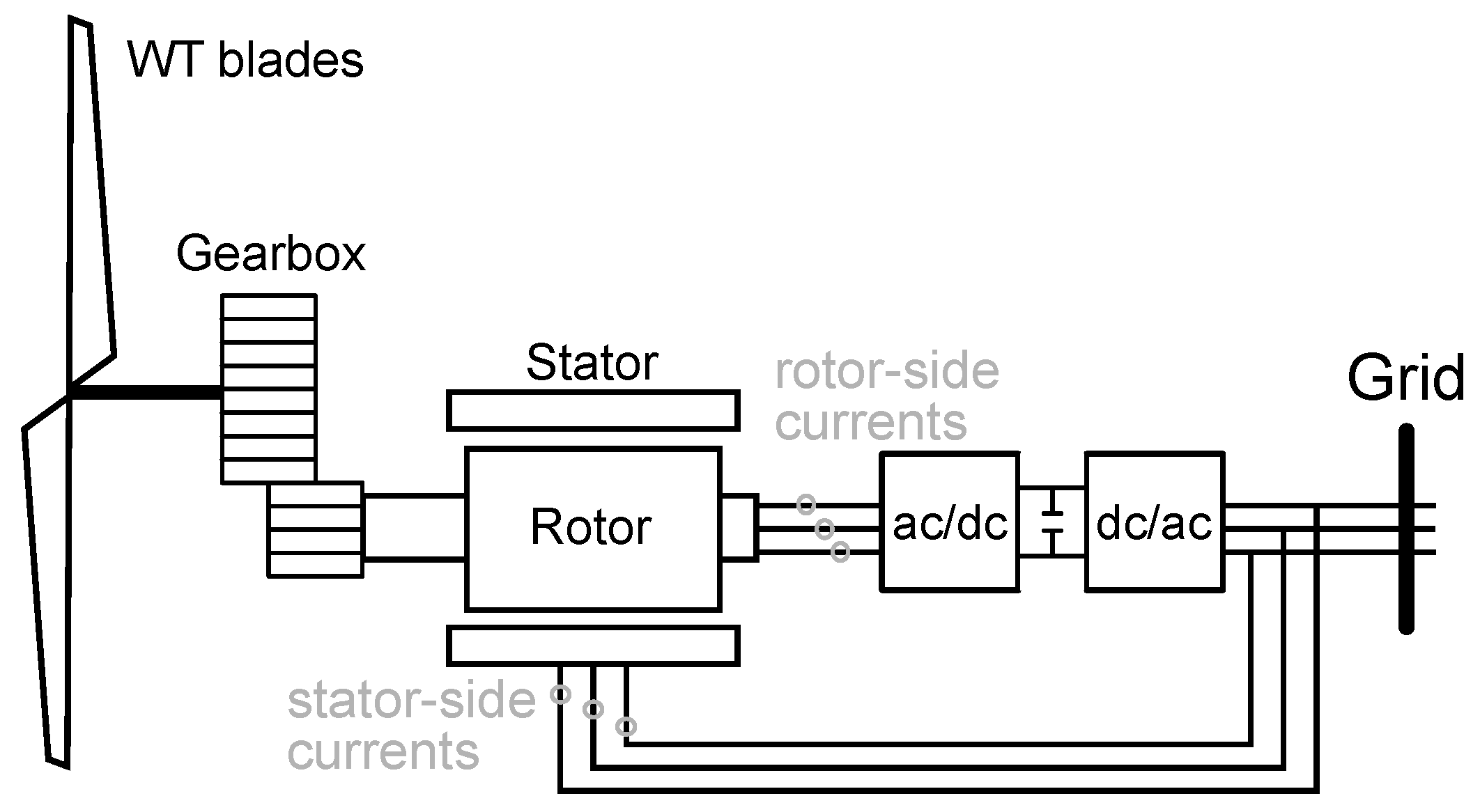

3. In-Service WT Data Used for the Analysis and Background

- RMS value of raw stator currents.

- Mains frequency of stator currents.

- RMS value of raw rotor-side converter currents.

- Mains frequency of rotor-side converter currents.

4. Results: Application of HOTA to Steady and Non-Steady State Working Conditions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enevoldsen, P.; Xydis, G. Examining the trends of 35 years growth of key wind turbine components. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2019, 50, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebars, A.D.; Eladl, A.A.; Abdulsalam, G.M.; Badran, E.A. Internal electrical fault detection techniques in DFIG-based wind turbines: A review. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2022, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, C.; Kazemtabrizi, B.; Crabtree, C. Wind turbine reliability data review and impacts on levelised cost of energy. Wind Energy 2019, 22, 1848–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Á.M.; Orosa, J.A.; Vergara, D.; Fernández-Arias, P. New tendencies in wind energy operation and maintenance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.A.; Bakhsh, S.T.; Irfan, M.; Nor, N.b.M.; Nowakowski, G. A review to diagnose faults related to three-phase industrial induction motors. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2022, 22, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeriwala, S. Induction motor diagnostics using vibration and motor current signature analysis. In Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Mechanics Annual Conference and Exposition, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–8 May 2023; pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Issaadi, I.; Hemsas, K.E.; Soualhi, A. Wind turbine gearbox diagnosis based on stator current. Energies 2023, 16, 5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osornio-Rios, R.A.; Cueva-Perez, I.; Alvarado-Hernandez, A.I.; Dunai, L.; Zamudio-Ramirez, I.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A. FPGA-Microprocessor based Sensor for faults detection in induction motors using time-frequency and machine learning methods. Sensors 2024, 24, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzimov, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; Aziz, M.S. Detection of Inter-Turn Short-Circuit Faults for Inverter-Fed Induction Motors Based on Negative-Sequence Current Analysis. Sensors 2025, 25, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agah, G.; Rahideh, A.; Faradonbeh, V.; Kia, S.H. Stator winding interturn short-circuit fault modeling and detection of squirrel-cage induction motors. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 5725–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, S.K.; Vairavasundaram, I.; Aljafari, B.; Kareri, T. Rotor Bar Fault Diagnosis in Indirect Field–Oriented Control-Fed Induction Motor Drive Using Hilbert Transform, Discrete Wavelet Transform, and Energy Eigenvalue Computation. Machines 2023, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diversi, R.; Lenzi, A.; Speciale, N.; Barbieri, M. An Autoregressive-Based Motor Current Signature Analysis Approach for Fault Diagnosis of Electric Motor-Driven Mechanisms. Sensors 2025, 25, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Shi, X.; Zou, H.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, J. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine generators based on stacking integration algorithm and adaptive threshold. Sensors 2023, 23, 6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gritli, Y.; Stefani, A.; Rossi, C.; Filippetti, F.; Chatti, A. Experimental validation of doubly fed induction machine electrical faults diagnosis under time-varying conditions. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2011, 81, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behara, R.K.; Saha, A.K. Artificial intelligence techniques framework in the design and optimisation phase of the doubly fed induction generator’s power electronic converters: A review of current status and future trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 215, 115573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigao, E.; Koukoura, S.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Carroll, J.; McDonald, A.; Gómez-Lázaro, E. Current Signature and Vibration Analyses to Diagnose an In-Service Wind Turbine Drive Train. Energies 2018, 11, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Neti, P. Detection of gearbox bearing defects using electrical signature analysis for Doubly-fed wind generators. In Proceedings of the Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Denver, CO, USA, 15–19 September 2013; pp. 4438–4444. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, F.; Qu, L.; Qiao, W.; Wei, C.; Hao, L. Fault Diagnosis of Wind Turbine Gearboxes Based on DFIG Stator Current Envelope Analysis. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Ancona, A.; Sevilla-Camacho, P.Y.; Robles-Ocampo, J.B.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J.; De la Cruz-Arreola, S.; Hernández-Estrada, E.N. Comparative Study of Vibration-Based Machine Learning Algorithms for Crack Identification and Location in Operating Wind Turbine Blades. AI 2025, 6, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barszcz, T. Vibration-Based Condition Monitoring of Wind Turbines; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sapena-Bano, A.; Burriel-Valencia, J.; Pineda-Sanchez, M.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Riera-Guasp, M. The harmonic order tracking analysis method for the fault diagnosis in induction motors under time-varying conditions. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2016, 32, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapena-Bano, A.; Riera-Guasp, M.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Martinez-Roman, J.; Perez-Cruz, J.; Pineda-Sanchez, M. Harmonic order tracking analysis: A speed-sensorless method for condition monitoring of wound rotor induction generators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 4719–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Moosavi, S. Eccentricity fault detection – From induction machines to DFIG A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, M.R.; Borghesani, P.; Tan, A.C. Electrical Signature Analysis-Based Detection of External Bearing Faults in Electromechanical Drivetrains. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 5941–5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zou, J.; Cao, F. Adaptively Detecting the Transient Feature of Faulty Wind Turbine Planetary Gearboxes by the Improved Kurtosis and Iterative Thresholding Algorithm. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 14602–14612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.H. Two-reaction theory of synchronous machines generalized method of analysis-part I. Trans. Am. Inst. Electr. Eng. 1929, 48, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Guasp, M.; Pineda-Sanchez, M.; Pérez-Cruz, J.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Roger-Folch, J.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A. Diagnosis of induction motor faults via Gabor analysis of the current in transient regime. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 61, 1583–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Calva, T.A.; Morinigo-Sotelo, D.; Duque-Perez, O.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Romero-Troncoso, R.d.J. Time-frequency analysis based on minimum-norm spectral estimation to detect induction motor faults. Energies 2020, 13, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Sanchez, M.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Riera-Guasp, M.; Sapena-Bano, A.; Roger-Folch, J.; Perez-Cruz, J. Motor condition monitoring of induction motor with programmable logic controller and industrial network. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, Birmingham, UK, 30 August 2011–01 September 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Artigao, E.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Gomez-Lazaro, E. Current signature analysis to monitor DFIG wind turbine generators: A case study. Renew. Energy. 2018, 116, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigao, E.; Sapena-Bano, A.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Martinez-Roman, J.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Gómez-Lázaro, E. Long-term operational data analysis of an in-service wind turbine DFIG. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 17896–17906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Current Transducer | Sampling Parameters | Measurement Type |

|---|---|---|

| HOP 2000-SB/SP1 ±3000 A | 1.5 kHz 5.4 s | Stator-side current phase a |

| Stator-side current phase b | ||

| Stator-side current phase c | ||

| Rotor-side converter current phase a | ||

| Rotor-side converter current phase b | ||

| Rotor-side converter current phase c |

| Month | No. of Stationary Measurements | Total Number of Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| November | 212 | 528 |

| December | 82 | 281 |

| January | 259 | 693 |

| February | 164 | 519 |

| March | 180 | 652 |

| April | 96 | 382 |

| May | 160 | 433 |

| June | 132 | 373 |

| TOTAL | 1285 | 3861 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delfa-Baena, S.; Artigao, E.; Terron-Santiago, C.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Burriel-Valencia, J.; Gomez-Lazaro, E. Condition Monitoring of In-Service DFIGs Working Under Non-Stationary Conditions via NsHOTA: A Motor Current Signature Approach. Sensors 2025, 25, 7451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247451

Delfa-Baena S, Artigao E, Terron-Santiago C, Honrubia-Escribano A, Burriel-Valencia J, Gomez-Lazaro E. Condition Monitoring of In-Service DFIGs Working Under Non-Stationary Conditions via NsHOTA: A Motor Current Signature Approach. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247451

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelfa-Baena, Sandra, Estefania Artigao, Carla Terron-Santiago, Andres Honrubia-Escribano, Jordi Burriel-Valencia, and Emilio Gomez-Lazaro. 2025. "Condition Monitoring of In-Service DFIGs Working Under Non-Stationary Conditions via NsHOTA: A Motor Current Signature Approach" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247451

APA StyleDelfa-Baena, S., Artigao, E., Terron-Santiago, C., Honrubia-Escribano, A., Burriel-Valencia, J., & Gomez-Lazaro, E. (2025). Condition Monitoring of In-Service DFIGs Working Under Non-Stationary Conditions via NsHOTA: A Motor Current Signature Approach. Sensors, 25(24), 7451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247451