A Control Method for Optimizing the Spectral Ratio Characteristics of LED Lighting to Provide Color Rendering Performance Comparable to Natural Light

Abstract

1. Introduction

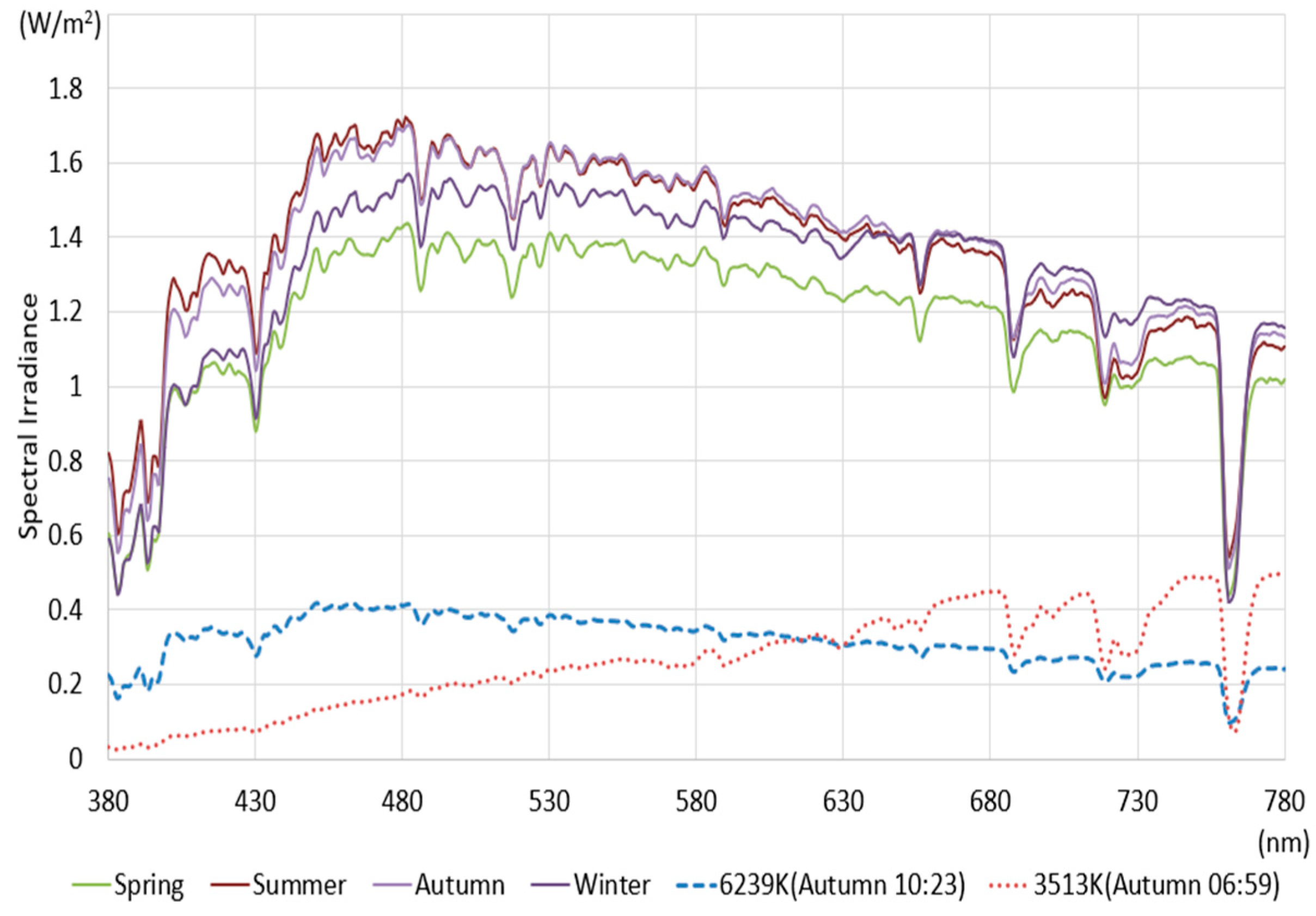

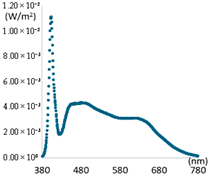

2. Analysis of Natural and Artificial Light Characteristics for Spectral Ratio Optimization

3. Control Method of Natural Light LED Lighting to Achieve High CRI by Optimizing Spectral Ratio

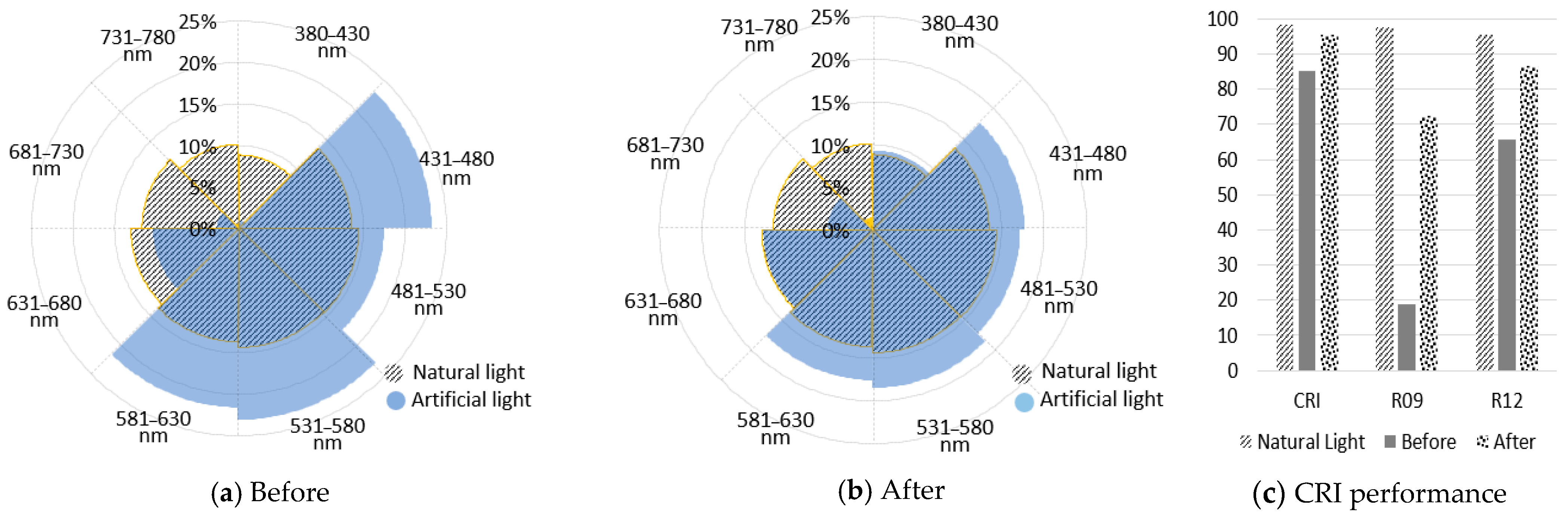

3.1. Spectral Ratio Optimization as per Natural Light Characteristics

3.2. Control of High CRI Natural Light LED Lighting

4. Experiments and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, M.R. The quality of light sources. Color. Technol. 2011, 127, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Arunkumar, P.; Park, S.H.; Yoon, H.S.; Im, W.B. Tuning the diurnal natural daylight with phosphor converted white LED–Advent of new phosphor blend composition. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2015, 193, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.S. 51.4: Design of highly efficient white LED for the maximal CRI. In SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers, Proceedings of the International Conference on Display Technology (ICDT 2020), Wuhan, China 11–14 October 2020; SID: Campbell, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 52, pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.N.; Kim, K.D.; Anoop, G.; Kim, G.S.; Yoo, J.S. Design of highly efficient phosphor-converted white light-emitting diodes with color rendering indices (R 1−R 15) ≥ 95 for artificial lighting. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Xu, Z.; Chan, J.; Devakumar, B.; Huang, X. Realizing full-spectrum LED lighting with a bright broadband cyan-green-emitting CaY2ZrGaAl3O12: Ce3+ garnet phosphor. J. Lumin. 2023, 263, 120015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Norton, B. Interior colour rendering of daylight transmitted through a suspended particle device switchable glazing. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 163, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, I.; León, J.; Bustamante, P. Daylight spectrum index: A new metric to assess the affinity of light sources with daylighting. Energies 2018, 11, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Near, A. LEDs+ Color Quality: Seeing beyond CRI. Light. Des. Appl. 2011, 41, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIE. Colour Rendering (TC1-33 Closing Remarks); CIE TC1, Technical Report for Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage; CIE: Vienna, Austria, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, Y. Spectral design considerations for white LED color rendering. Opt. Eng. 2005, 44, 111302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Xu, J.; Yan, H. Spectral optimization of warm-white light-emitting diode lamp with both color rendering index (CRI) and special CRI of R9 above 90. AIP Adv. 2011, 1, 032160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Oh, S.T.; Lim, J.H. Exhibition Hall lighting design that fulfill high CRI based on natural light characteristics-focusing on CRI Ra, R9, R12. J. Internet Comput. Serv. 2024, 25, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Deng, Z.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lan, H.; Lu, Y.; Cao, Y. Study on the correlations between color rendering indices and the spectral power distribution. Opt. Express 2014, 22 (Suppl. S4), A1029–A1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, W.; Devakumar, B.; Ma, N.; Huang, X.; Lee, A.F. Full-spectrum white light-emitting diodes enabled by an efficient broadband green-emitting CaY2ZrScAl3O12: Ce3+ garnet phosphor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 5643–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Sun, S.; Xu, B.; Deng, Z. Polymer-encapsulated halide perovskite color converters to overcome blue overshoot and cyan gap of white light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.O.; Jo, H.S.; Ryu, U.C. Improving CRI and scotopic-to-photopic ratio simultaneously by spectral combinations of cct-tunable led lighting composed of multi-chip leds. Curr. Opt. Photonics 2020, 4, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Fu, L.; Wu, D.; Peng, J.; Du, F.; Ye, X.; Chen, L.; Zhuang, W. A cyan-emitting phosphor Ca3SiO4 (Cl, Br)2: Eu2+ with high efficiency and good thermal stability for full-visible-spectrum LED lighting. J. Lumin. 2021, 232, 117854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, J.G.; Shen, C. Blue light hazard optimization for high quality white LEDs. IEEE Photonics J. 2018, 10, 8201210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, S.; Sun, L.; Liang, J.; Devakumar, B.; Huang, X. Achieving full-visible-spectrum LED lighting via employing an efficient Ce3+-activated cyan phosphor. Mater. Today Energy 2020, 17, 100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, P. Improving CRI and luminous efficiency of phosphor-converted full-spectrum WLEDs by powder sedimentation packaging. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-T.; Lim, J.-H. CRI-Based Smart Lighting System That Provides Characteristics of Natural Light. Information 2023, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalani, M.J.; Kalani, M. Controlling the correlated color temperature of high CRI light-emitting diodes in response to the time of day as a way of enhancing the well-being of smart city residents. Optik 2022, 270, 169975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukovic, M.; Lukovic, V.; Belca, I.; Kasalica, B.; Stanimirovic, I.; Vicic, M. LED-based Vis-NIR spectrally tunable light source-the optimization algorithm. J. Eur. Opt. Soc.-Rapid Publ. 2016, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryc, I.; Brown, S.W.; Ohno, Y. Spectral matching with an LED-based spectrally tunable light source. In Fifth International Conference on Solid State Lighting, Proceedings of the Optics and Photonics, San Diego, CA, USA, 31 July–4 August 2005; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; Volume 5941, pp. 300–308. [Google Scholar]

| Light Source | Illuminance (Lux) | CCT (K) | CRI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ra) | (R9) | (R12) | |||

| Spring (17 March 2021) | 97,667 | 5471 | 99.3 | 98.8 | 97.8 |

| Summer (3 June 2023) | 113,055 | 5742 | 99.2 | 99.3 | 97.4 |

| Autumn (27 September 2022) | 113,729 | 5607 | 99.3 | 98.1 | 97.8 |

| Winter (24 December 2024) | 107,135 | 5402 | 99.2 | 99.6 | 97.6 |

| Autumn (27 September 2022. 10:23) | 26,042 | 6239 | 99.3 | 99.0 | 97.8 |

| Autumn (27 September 2022. 06:59) | 18,845 | 3513 | 96.1 | 81.6 | 96.7 |

| Light Source | CCT (K) | CRI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ra) | (R9) | (R12) | ||

| Light0 (General Office Lighting) | 5200 | 82.7 | 4.12 | 59.6 |

| Light1 (CCT Tunable Lighting) | 5516 | 85.3 | 18.6 | 65.7 |

| Light2 (High CRI Lighting) | 5513 | 97.5 | 93.2 | 82.7 |

| Light2 (Control: 3500 K) | 3500 | 97.4 | 94.4 | 88.8 |

| Light2 (Control: 6200 K) | 6212 | 96.0 | 85.8 | 79.0 |

| Category Wavelength (nm) | Spectral Ratio (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Light | Artificial Light | ||||||||||

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | Autumn (6239 K) | Autumn (3513 K) | Light0 | Light1 | Light2 | Light2 (Control 3500 K) | Light2 (Control 6200 K) | |

| 380–430 | 8.89 | 9.90 | 9.34 | 8.25 | 11.26 | 2.64 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 3.37 | 1.87 | 3.72 |

| 431–480 | 13.56 | 14.24 | 13.91 | 13.22 | 15.36 | 6.27 | 21.27 | 23.21 | 19.31 | 11.75 | 21.12 |

| 481–530 | 14.38 | 14.67 | 14.62 | 14.39 | 15.11 | 9.68 | 17.67 | 17.47 | 17.18 | 13.11 | 18.15 |

| 531–580 | 14.41 | 14.42 | 14.49 | 14.31 | 14.31 | 12.08 | 24.31 | 23.06 | 19.10 | 18.08 | 19.34 |

| 581–630 | 13.76 | 13.51 | 13.67 | 13.70 | 12.99 | 14.24 | 22.32 | 21.58 | 18.09 | 23.04 | 16.91 |

| 631–680 | 13.01 | 12.58 | 12.81 | 13.34 | 11.92 | 18.54 | 10.56 | 10.39 | 15.07 | 21.34 | 13.57 |

| 681–730 | 11.57 | 10.82 | 11.10 | 12.09 | 10.03 | 17.31 | 2.70 | 2.72 | 6.28 | 8.67 | 5.71 |

| 731–780 | 10.20 | 9.65 | 9.85 | 10.49 | 9.02 | 19.25 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 1.59 | 2.12 | 1.46 |

| Light Source | SPD Current Value STEP | Spectral Characteristics (Spectral Ratio %) | Light Property | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380–430 nm | 431–480 nm | 481–530 nm | 531–580 nm | 581–630 nm | 631–680 nm | 681–730 nm | 731–780 nm | Illumin-ance (Lux) | CCT (K) | CRI | R9 | R12 | ||

| Natural Light | 8.50 | 13.70 | 14.60 | 14.60 | 13.50 | 13.10 | 11.50 | 10.30 | - | 5500.0 | 97.2 | 91.5 | 82.8 | |

| Combination Light | 1.1 | 23.4 | 17.9 | 23.5 | 21.9 | 10.5 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 499.2 | 5518.8 | 85.3 | 18.7 | 65.7 | |

| Add Light Source 405 nm | 1 | 9.6 | 21.4 | 16.4 | 21.5 | 20.0 | 9.6 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 499.3 | 5607.3 | 85.7 | 21.1 | 68.8 |

| 2 | 16.7 | 19.7 | 15.1 | 19.8 | 18.5 | 8.8 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 499.4 | 5699.7 | 86.0 | 23.6 | 71.6 | |

| 3 | 22.8 | 18.3 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 8.2 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 499.5 | 5796.2 | 86.3 | 26.0 | 74.1 | |

| Add Light Source 655 nm | 1 | 1.0 | 21.4 | 16.4 | 21.5 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 508.0 | 5157.0 | 91.5 | 74.3 | 72.5 |

| 2 | 0.9 | 19.7 | 15.1 | 19.8 | 18.5 | 24.6 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 516.8 | 4823.6 | 94.1 | 77.7 | 71.6 | |

| 3 | 0.8 | 18.3 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 30.2 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 525.6 | 4516.6 | 90.2 | 37.8 | 74.1 | |

| Add Light Source 705 nm | 1 | 1.0 | 21.4 | 16.4 | 21.5 | 20.0 | 9.6 | 11.1 | 0.6 | 499.5 | 5504.1 | 85.6 | 21.5 | 65.6 |

| 2 | 0.9 | 19.7 | 15.1 | 19.8 | 18.5 | 8.8 | 18.1 | 0.5 | 499.9 | 5489.4 | 85.9 | 24.2 | 65.6 | |

| 3 | 0.8 | 18.3 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 8.2 | 24.1 | 0.5 | 500.2 | 5474.7 | 86.2 | 26.9 | 65.5 | |

| Add Light Source 755 nm | 1 | 1.0 | 21.4 | 16.4 | 21.5 | 20.0 | 9.6 | 2.5 | 9.2 | 499.2 | 5518.4 | 85.3 | 18.8 | 65.6 |

| 2 | 0.9 | 19.7 | 15.1 | 19.8 | 18.5 | 8.8 | 2.3 | 16.3 | 499.2 | 5517.9 | 85.3 | 18.9 | 65.6 | |

| 3 | 0.8 | 18.3 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 8.2 | 2.1 | 22.5 | 499.2 | 5517.5 | 85.3 | 18.9 | 65.5 | |

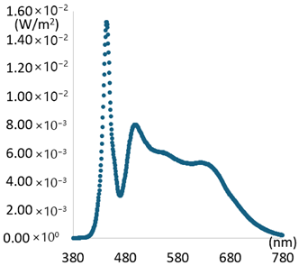

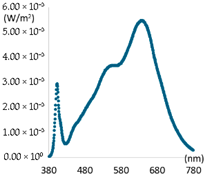

| CH1 | CH2 | CH3 | CH4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Peak: 450 nm, Illuminance: 400 Lux | Peak: 405 nm, Illuminance: 250 Lux | ||

| SPD |  |  |  |  |

| CCT(K) | 3158 K | 6621 K | 3165 K | 6601 K |

| CRI | 98.61 | 96.34 | 97.44 | 95.89 |

| R9 | 96.26 | 98.02 | 96.60 | 97.45 |

| R12 | 88.80 | 92.32 | 93.58 | 93.85 |

| lm/W | 62 | 67 | 45 | 44 |

| CCT (K) | Light Source | Spectral Characteristics (Spectral Ratio %) | Light Property | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380–430 nm | 431–480 nm | 481–530 nm | 531–580 nm | 581–630 nm | 631–680 nm | 681–730 nm | 731–780 nm | Illumin-ance | CCT | CRI | R9 | R12 | ||

| 3500 | Natural Light | 3.06 | 6.89 | 10.05 | 11.97 | 13.83 | 17.62 | 17.97 | 18.18 | - | 3687 | 96.1 | 80.4 | 96.0 |

| Light1 (CCT Tunable) | 7.73 | 10.62 | 13.61 | 17.52 | 22.86 | 18.30 | 7.33 | 2.00 | 509.0 | 3547 | 96.0 | 74.0 | 94.3 | |

| Light2 (High CRI) | 3.08 | 10.94 | 13.13 | 17.83 | 22.65 | 21.26 | 8.85 | 2.24 | 494.1 | 3495 | 97.8 | 94.9 | 91.3 | |

| Light3 (Experimental) | 3.65 | 8.99 | 13.76 | 17.47 | 21.26 | 21.83 | 10.15 | 2.86 | 479.1 | 3502 | 98.0 | 97.6 | 95.1 | |

| 5500 | Natural Light | 8.85 | 13.57 | 14.46 | 14.35 | 13.67 | 13.04 | 11.70 | 10.15 | - | 5500 | 98.4 | 97.8 | 95.4 |

| Light1 (CCT Tunable) | 9.34 | 17.72 | 17.17 | 18.47 | 17.56 | 12.86 | 5.34 | 1.51 | 509.3 | 5493 | 95.4 | 72.3 | 86.6 | |

| Light2 (High CRI) | 9.96 | 16.46 | 17.13 | 17.17 | 16.54 | 14.41 | 6.49 | 1.82 | 509.3 | 5658 | 98.8 | 98.7 | 93.6 | |

| Light3 (Experimental) | 7.19 | 16.78 | 18.42 | 17.07 | 16.77 | 15.01 | 6.81 | 1.93 | 511.3 | 5481 | 97.1 | 92.8 | 99.1 | |

| 6200 | Natural Light | 9.04 | 13.70 | 14.50 | 14.34 | 13.63 | 12.94 | 11.61 | 10.03 | - | 5547 | 98.4 | 97.6 | 95.5 |

| Light1 (CCT Tunable) | 9.02 | 20.46 | 18.13 | 19.24 | 17.15 | 10.76 | 4.09 | 1.13 | 504.3 | 6178 | 92.2 | 53.2 | 80.0 | |

| Light2 (High CRI) | 9.87 | 18.57 | 18.01 | 17.43 | 15.80 | 13.00 | 5.73 | 1.59 | 499.9 | 6389 | 96.3 | 87.3 | 82.0 | |

| Light3 (Experimental) | 8.66 | 18.51 | 19.41 | 16.81 | 15.64 | 13.29 | 5.97 | 1.70 | 504.4 | 6155 | 98.8 | 94.1 | 89.8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, S.-T.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lim, J.-H. A Control Method for Optimizing the Spectral Ratio Characteristics of LED Lighting to Provide Color Rendering Performance Comparable to Natural Light. Sensors 2025, 25, 7453. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247453

Oh S-T, Lee J-Y, Lim J-H. A Control Method for Optimizing the Spectral Ratio Characteristics of LED Lighting to Provide Color Rendering Performance Comparable to Natural Light. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7453. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247453

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Seung-Teak, Ji-Young Lee, and Jae-Hyun Lim. 2025. "A Control Method for Optimizing the Spectral Ratio Characteristics of LED Lighting to Provide Color Rendering Performance Comparable to Natural Light" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7453. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247453

APA StyleOh, S.-T., Lee, J.-Y., & Lim, J.-H. (2025). A Control Method for Optimizing the Spectral Ratio Characteristics of LED Lighting to Provide Color Rendering Performance Comparable to Natural Light. Sensors, 25(24), 7453. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247453