Abstract

Shiraia mycelial culture is a promising biotechnological alternative for the production of hypocrellin A (HA), a new photosensitizer for anticancer photodynamic therapy (PDT). The extractive fermentation of intracellular HA in the nonionic surfactant Triton X-100 (TX100) aqueous solution was studied in the present work. The addition of 25 g/L TX100 at 36 h of the fermentation not only enhanced HA exudation to the broth by 15.6-fold, but stimulated HA content in mycelia by 5.1-fold, leading to the higher production 206.2 mg/L, a 5.4-fold of the control on day 9. After the induced cell membrane permeabilization by TX100 addition, a rapid generation of nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was observed. The increase of NO level was suppressed by the scavenger vitamin C (VC) of reactive oxygen species (ROS), whereas the induced H2O2 production could not be prevented by the NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (PTIO), suggesting that NO production may occur downstream of ROS in the extractive fermentation. Both NO and H2O2 were proved to be involved in the expressions of HA biosynthetic genes (Mono, PKS and Omef) and HA production. NO was found to be able to up-regulate the expression of transporter genes (MFS and ABC) for HA exudation. Our results indicated the integrated role of NO and ROS in the extractive fermentation and provided a practical biotechnological process for HA production.

1. Introduction

Hypocrellin A (HA) is a perylenequinone pigment extracted from the fruiting bodies of a pathogenic fungus Shiraia bambusicola in bamboos. HA has been widely used in photodynamic therapy (PDT) for skin diseases and is becoming a novel non-porphyrin photosensitizer for the treatment of cancers and viruses [1,2]. Due to the limitations of the wild fungal fruiting bodies and complexity of total chemical synthesis of HA [3], Shiraia mycelium culture has become a biotechnological alternative for HA production [4]. Since lower HA yield is the bottleneck of biotechnological production of HA in Shiraia fermentation, many process strategies have been applied to Shiraia cultures, including medium optimization, treatment of fungal elicitor [5,6], ultrasound stimulation [7] and light radiation [8,9]. Liu et al. (2016) managed to mutagenize Shiraia spores using cobalt-60 gamma irradiation to obtain mutated strains for higher HA production [10]. Apart from these conventional optimization methods, extractive fermentation in water-organic solvent two-phase system, also known as perstractive fermentation or milking process, is becoming an efficient strategy to enhance fungal products [11]. In extractive fermentation, organic surfactant is added to permeabilize cells for intracellular products across the cell membrane and extract the fungal products consecutively in the surfactant micelle aqueous solution. Another two-phase system is formed when a nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution is at above a certain temperature (cloud point). The cloud point system has a surfactant micelle aqueous solution and a coacervate phase (surfactant-rich phase), which has been extensively studied for the extraction, separation and purification of metal chelates, organic compounds and biomaterials [12]. Recently, nonionic surfactant Triton X-100 (TX100) has been applied successfully as an effective extractant on the perstraction of intracellular pigments produced by Monascus [13] and Talaromyces [14], the conversion of benzaldehyde into L-phenylacetylcarbinol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae [15] and microbial transformation of cholesterol by Mycobacterium sp. NRRL B-3683 [16]. In the mycelium culture of Shiraia sp. SUPERH168, TX100 at 0.2–1.0% (w/v) was used to induce hypocrellin biosynthesis [17]. We previously screened more surfactants including TX100, Tween-40, -80, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Brij 52, Span 80 and Pluronic F68, F-127 for the induction of HA in mycelium cultures of S. bambusicola and TX100 exhibited significant elicitation on HA production [18]. However, the application of the concept of nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution or cloud point system to submerged Shiraia fermentation has not been studied.

Great efforts have been made on the selection of different surfactant, optimization of addition time, effects of surfactant concentration, solubility and bioavailability, and fermentation mode in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution [11]. However, the underlying mechanism on the effects of nonionic surfactant on the production of fungal metabolites is still largely unknown. Some factors, including changes in fungal morphology and pellet formation [19], an increase in cell membrane permeability [13], solubilizing the extracellular pigments in micelle aqueous solution [20] and a perstraction effect of surfactant micelles [14] have been suggested as possible action mechanisms of surfactants. In our previous study on S. bambusicola, TX100 elicited HA biosynthesis and induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in the mycelia [18]. Since TX100 and other surfactants could incur toxic effects via disruption of cellular membrane [21], it is not surprising that the defense responses to oxidative stress could be initiated by the surfactant exposure. Now, compelling evidence indicates that, in addition to ROS generation, nitric oxide (NO) is an essential biological messenger in plant and mammalian cells under the oxidative stress [22,23]. However, there has been, so far, few reports regarding the regulation of NO on fungal metabolism, and no reports regarding physiological responses, especially on NO and ROS signaling during surfactant exposure in mycelium cultures. Therefore, as a follow-up exploration on stimulating HA production in the fermentation under elicited conditions including the treatments of fungal elicitor [24], the sonication of low-energy ultrasound [7,25], and the radiation of ultraviolet-B [26] or red light [9], we wish to explore the physiological role of NO and ROS in mycelium cultures of S. bambusicola in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution. This study may help us understand the mechanism or the signaling regulation in fungal extractive fermentation and provide a novel process strategy for HA production in Shiraia fermentation.

2. Results

2.1. Extractive Fermentation in Micelle Aqueous Solution

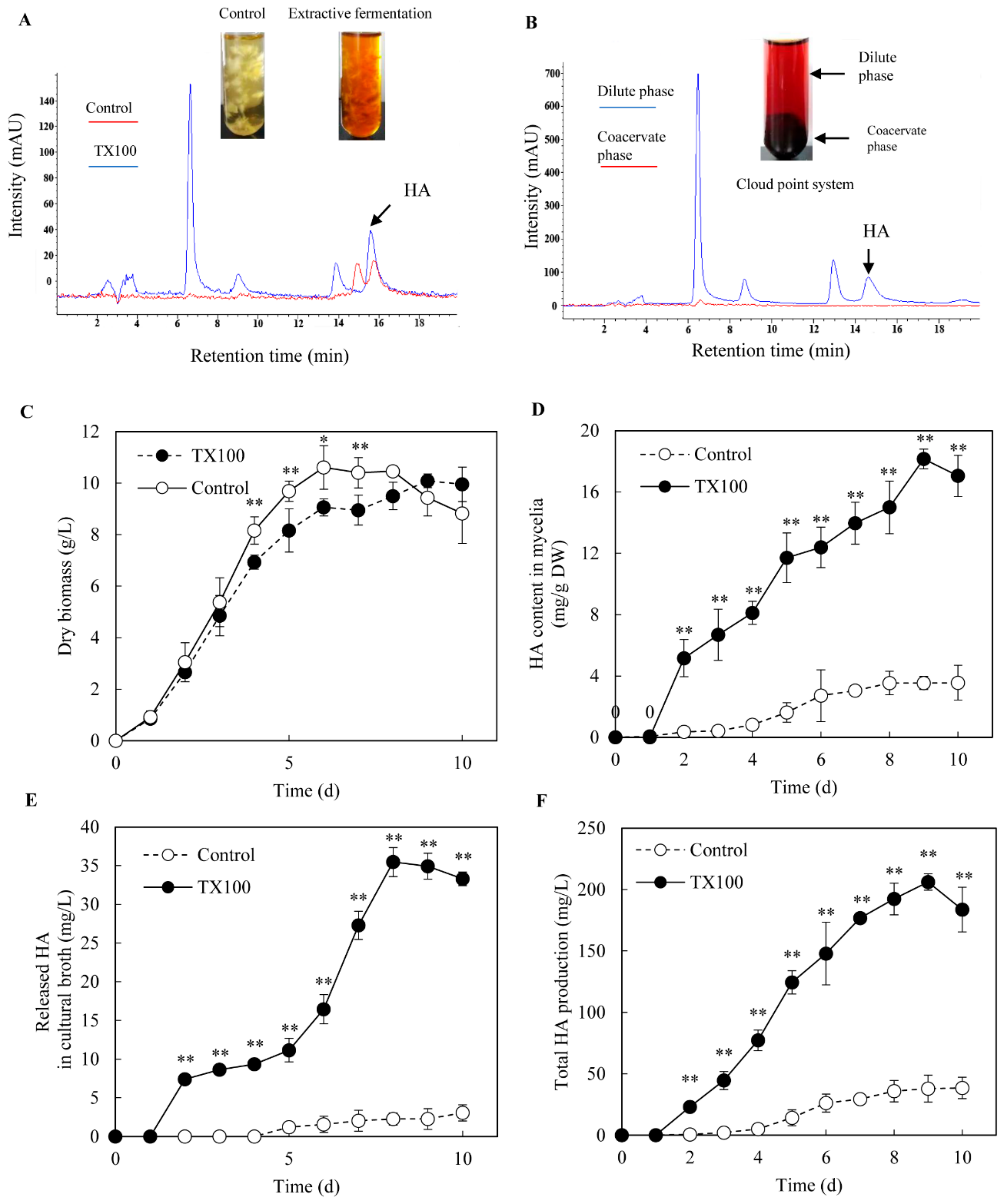

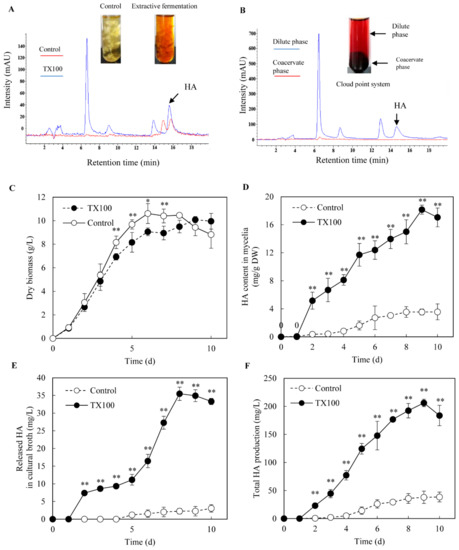

The biocompatibility, permeability and elicitation effects of nonionic surfactant TX100 to Shiraia cells are confirmed in our previous report [18]. Hence, extractive fermentation in submerged culture of Shiraia sp. S9 was conducted by adding TX100 at 25 g/L after 36 h of the initial culture. The red perylenequinone pigments of Shiraia were majorly accumulated intracellularly in the control culture without TX100 addition, but exported into the broth by extractive fermentation in the nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution (Figure 1A). Then, the extracellular broth after 8 days of the extractive fermentation was further subjected to cloud point extraction (Figure 1B). After phase separation in cloud point system at 75 °C, the extracellular pigments were separated into the dilute phase and coacervate phase (TX100-rich phase) whereas HA partitioned mainly to the coacervate phase (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1D, HA was an intracellular product as the amount of HA released from cells to medium was less than 8% in the control culture. Although TX100 led to a slight drop (less than 15%) of the mycelium biomass after day 4 (Figure 1C), HA contents in both mycelia and medium were enhanced significantly in the extractive fermentation (Figure 1D,E). The extracellular HA production was increased sharply after TX100 addition to the highest value (35.5 mg/L) on day 8, about a 15.6-fold increase over the control (Figure 1E); whereas the intracellular HA contents were increased by 5.1-fold (Figure 1D). After 9 days of the extractive fermentation, total HA production reached a highest value 206.2 mg/L (Figure 1F), about 5.4-fold of the control.

Figure 1.

The extractive fermentation of Shiraia sp. S9 in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution. (A) The chromatogram of HA in Shiraia mycelia in the extractive fermentation. (B) The chromatogram of HA in cloud point system. TX100 was added at (25 g/L) at 36 h of 8-day fermentation. The supernatant was heated at 75 °C for 1 h and separated into a cloud point system including TX100-rich phase (coacervate phase) and the dilute phase. The time-course of fungal biomass (C), HA content in mycelia (D), the released HA in cultural broth (E) and the total HA production (F) in the extractive fermentation. Data shown is the mean ± SD (n=3). Asterisks represent significant differences when compared to control group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

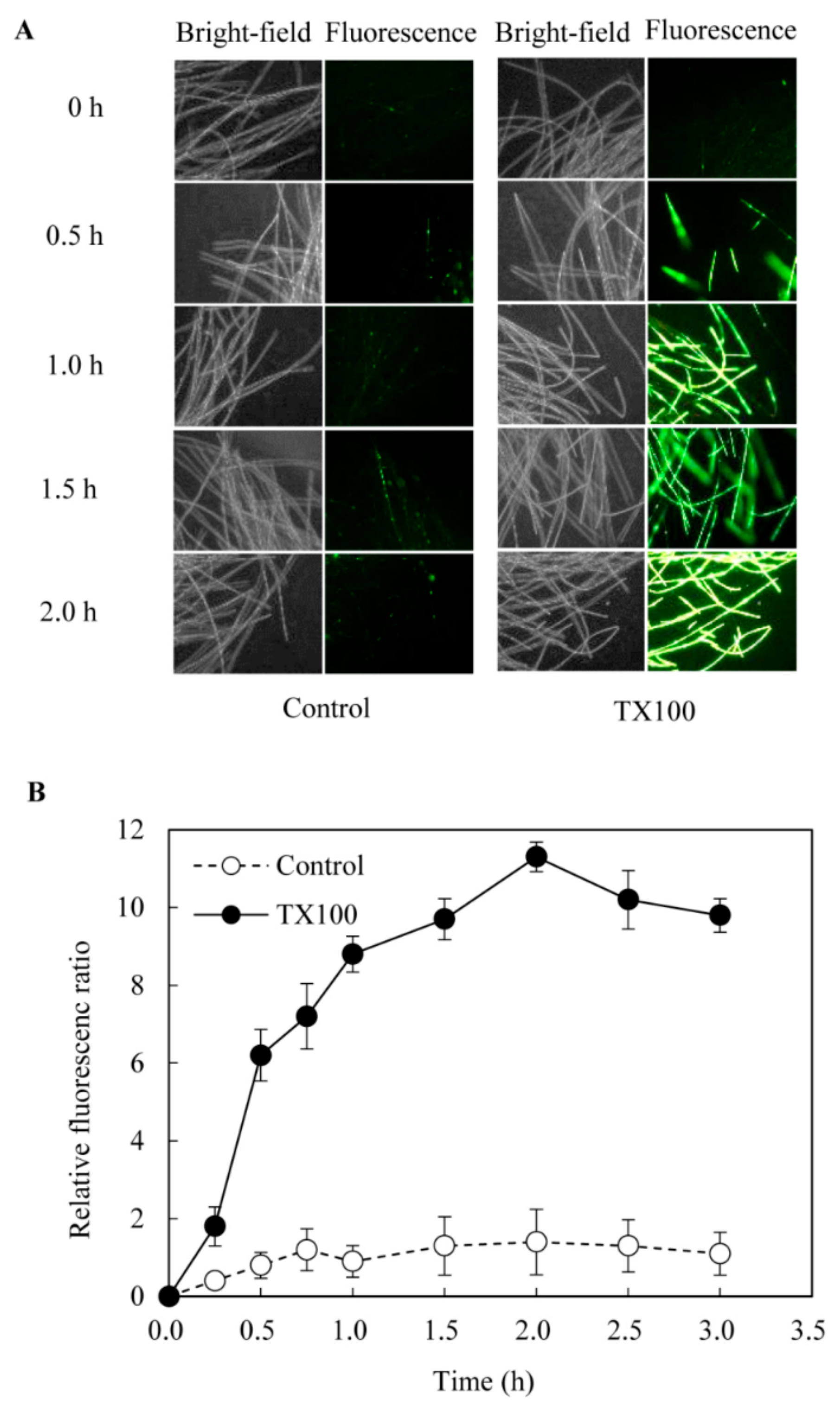

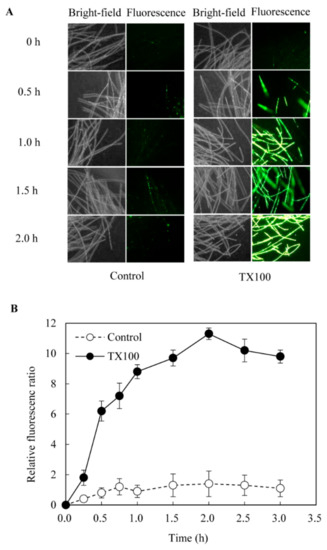

2.2. Effect of TX100 on Fungal Membrane Permeabilization

When TX100 was added to Shiraia hyphal cells, the uptake of the high-affinity nucleic acid stain fluorescent dye SYTOX Green was rapidly increased and the fluorescent signal emitted by hyphal cells was clear and strong (Figure 2A), indicating a higher permeability of the cell membrane. The relative fluorescent intensity showed about 8-fold increase after TX100 addition and peaked at about 2 h (Figure 2B), which proved that TX100 could improve the permeability of the fungal cell membrane in the extractive fermentation.

Figure 2.

The membrane permeability of hyphal cells in the extractive fermentation (400 ×). (A) The membrane integrity of hyphal cells was detected by a nucleic acid stain fluorescent dye SYTOX Green at 0.5 μmol/L. (B) The time-course of membrane permeability in the extractive fermentation. The relative fluorescence ratio is defined to the ratio of fluorescence intensity at a given time to that at 0 min. TX100 was added at 25 g/L at 36 h of the fermentation. Data shown is the mean ± SD (n=3).

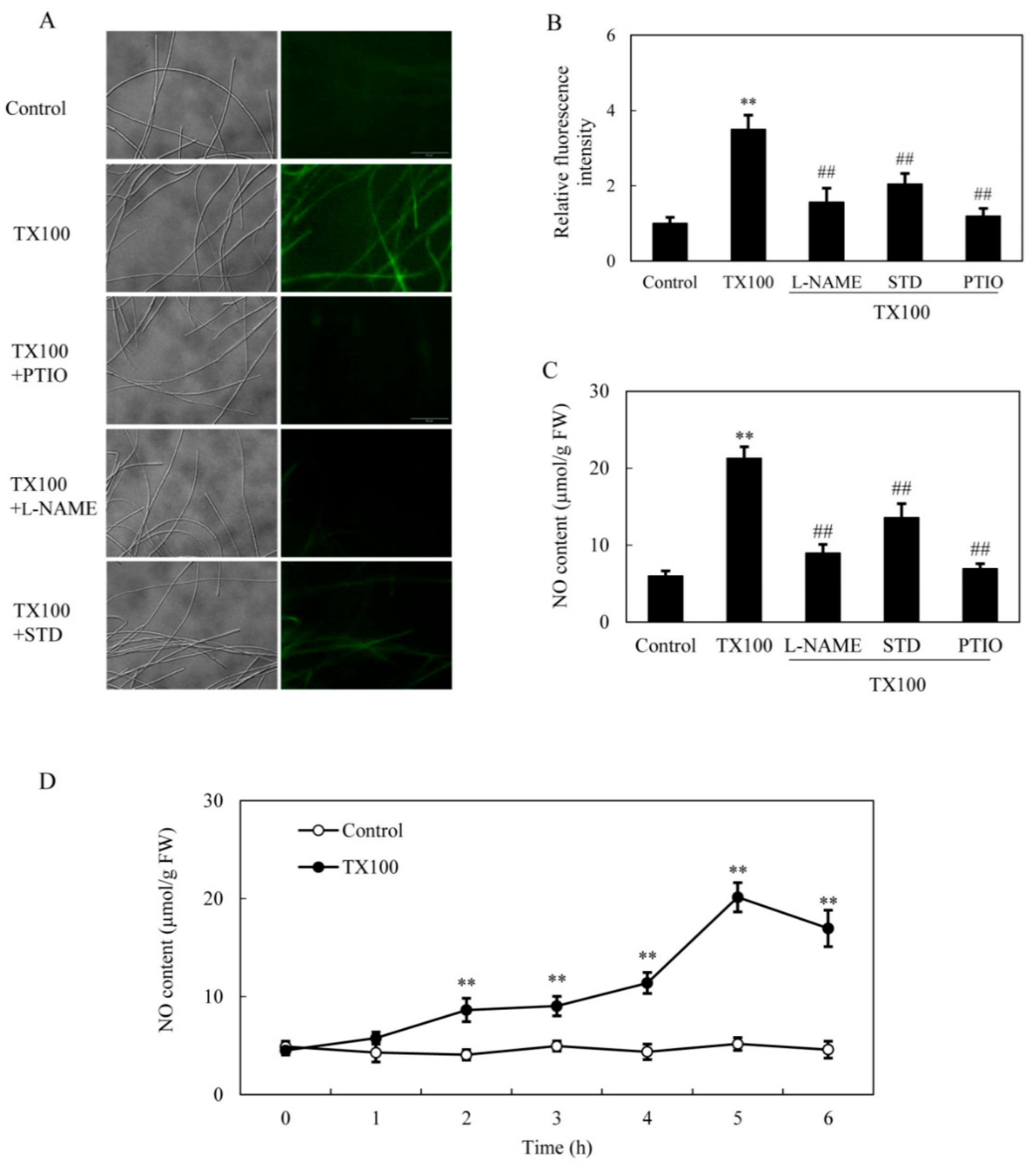

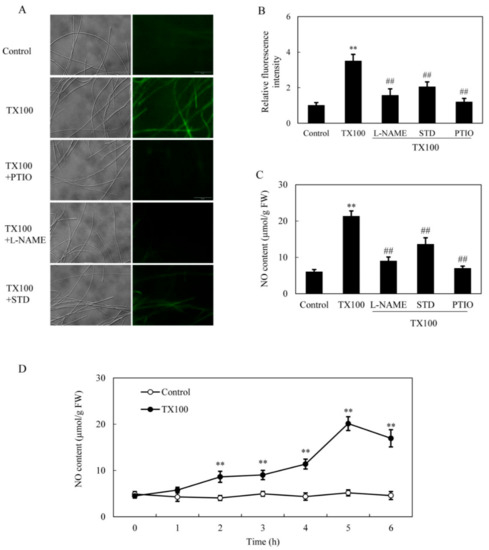

2.3. NO Generation in the Extractive Fermentation

The induced NO production in S. bambusicola mycelia was observed directly on the green fluorescence of 4, 5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA)-stained mycelia after 5 h of TX100 addition (Figure 3A, B). The induced fluorescence intensity was suppressed by NO scavengers 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (PTIO), indicating that endogenous NO was response for the increased fluorescence. The induced NO content in mycelium was inhibited by 58% and 36%, respectively, by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and nitrate reductase (NR) inhibitor sodium tungstate dihydrate (STD) (Figure 3A–C), suggesting that both NO synthase and NR were the possible sources for NO production. The induced NO accumulated with time and peaked around 5 h, about 3.9-fold over that of the control (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

NO generation in the extractive fermentation. (A) Bright-field image (left) and fluorescence microscopy of DAF-2 DA-stained mycelium (right) in cultures. TX100 was added at 25 g/L at 36 h of the fermentation. PTIO (100 μM), L-NAME (100 μM) or STD (100 μM) was added 30 min prior to TX100 treatment respectively. The photo was taken after 5 h of TX100 treatment. NO accumulation (relative fluorescence intensity) (B) and NO content (C) in mycelium after TX100 treatment. (D) Time-course of NO contents in mycelium after TX100 treatment. Values are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. TX100 group).

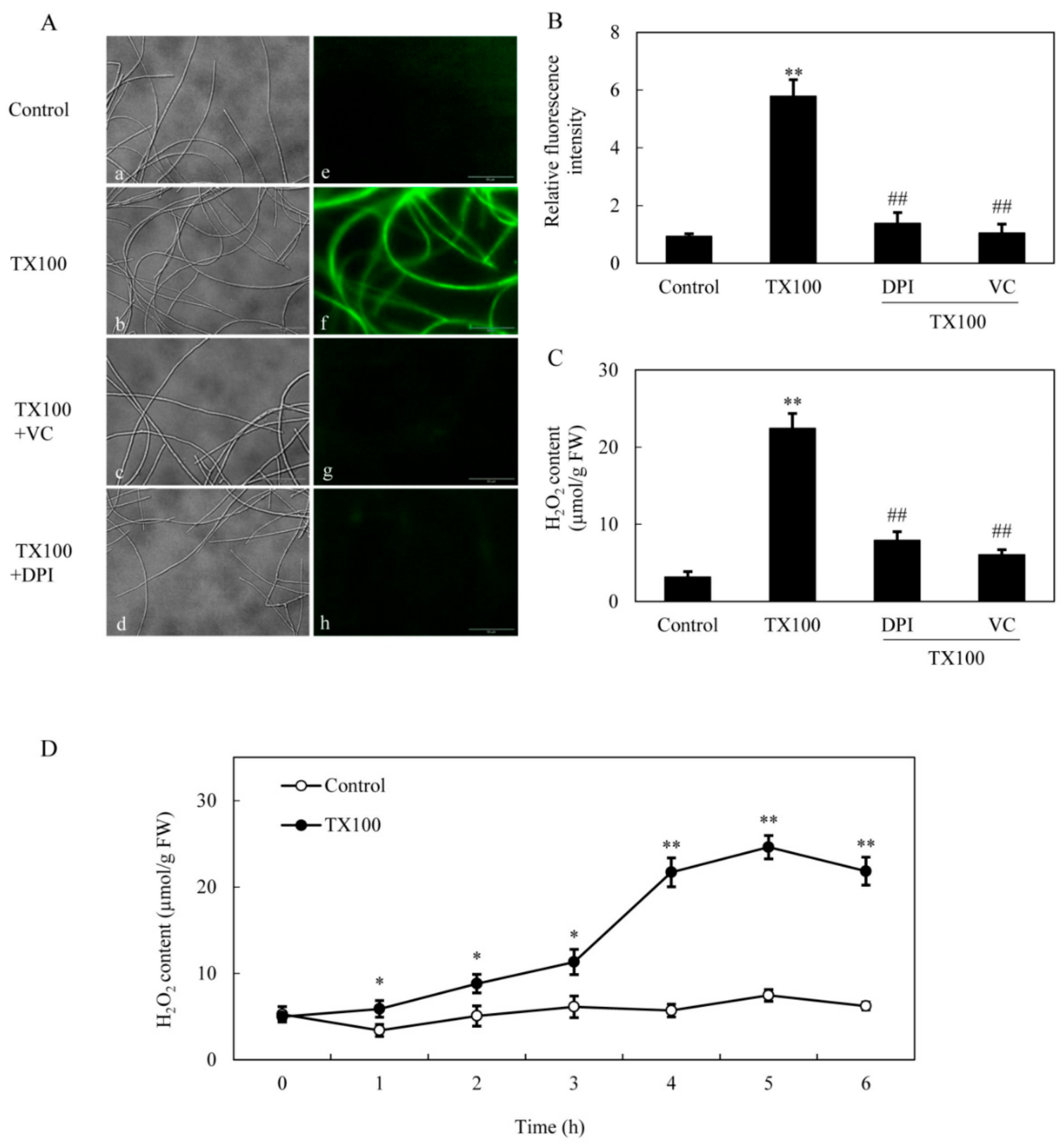

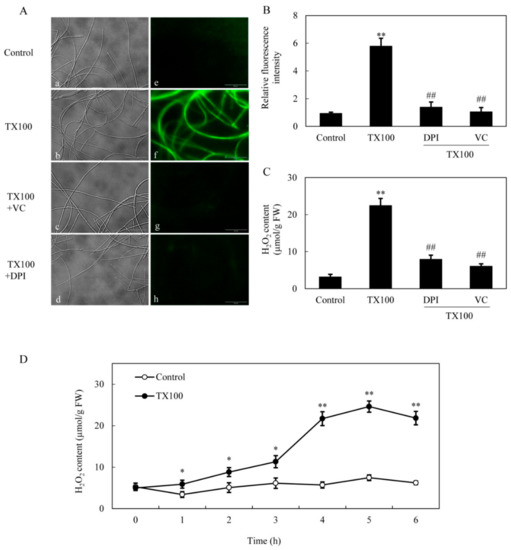

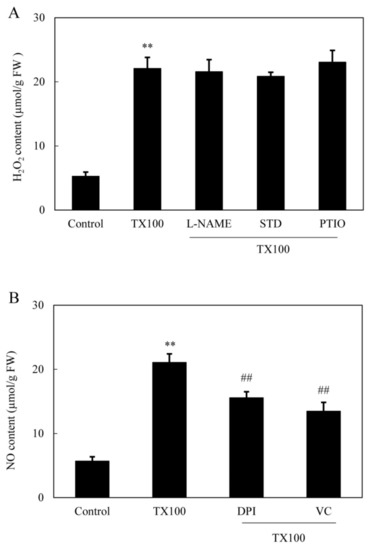

2.4. ROS Production in the Extractive Fermentation

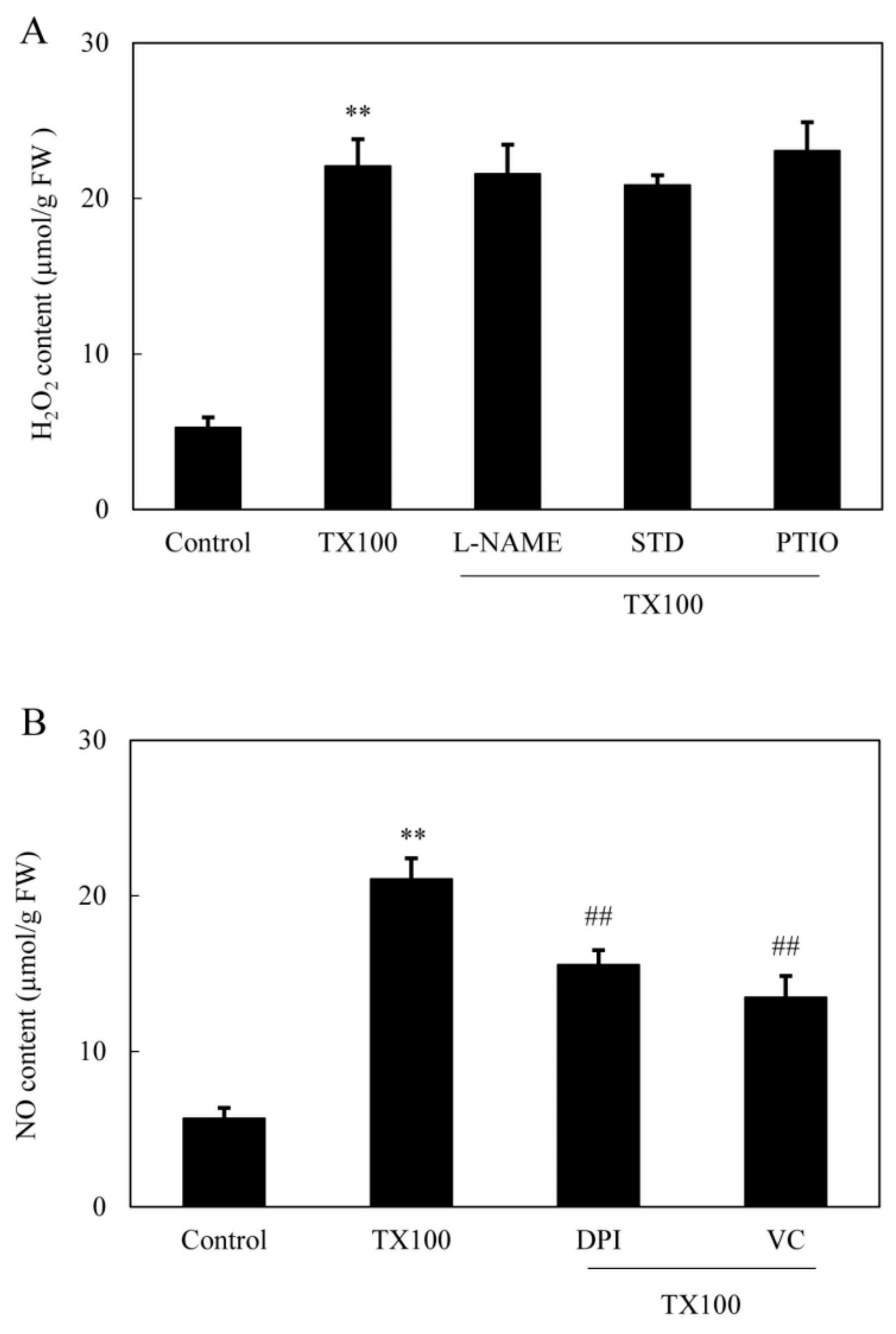

Simultaneously, TX100-induced ROS production in mycelia was directly observed using the green fluorescent probe of 2, 7-dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Figure 4A). After 5 h of TX100 treatment, the relative intensity of DCFH-DA fluorescence increased by 6.2-fold over that of control (Figure 4B). The fluorescent increase was blocked strongly by NADPH oxidase (NOX) inhibitor diphenylene iodonium (DPI) and ROS scavenger vitamin C (VC), suggesting that the fluorescence increase in the mycelia was mainly from ROS production by NOX. Moreover, the induced H2O2 content in mycelia was suppressed significantly by 65%, 73% by DPI and VC, respectively (Figure 4C). The extractive fermentation induced rapid accumulation of H2O2 around 5 h, reaching a broad peak of 24.6 μmol/g FW (Figure 4D). Although no significant suppression on H2O2 production was detected after the addition of NO inhibitors including PTIO, L-NAME and STD (Figure 5A), the induced NO production was suppressed by 26% and 36%, respectively, by DPI and VC (Figure 5B), suggesting the relationship between NO and the oxidative stress of the extractive fermentation.

Figure 4.

ROS generation in the extractive fermentation. (A) Bright-field image (left) and fluorescence microscopy of DCFH-DA-stained mycelium (right) in cultures. TX100 was added at 25 g/L at 36 h of the fermentation. DPI (5 μM) or VC (10 μM) was added 30 min prior to TX100 treatment respectively. The photo was taken after 5 h of TX100 treatment. ROS accumulation (relative fluorescence intensity) (B) and H2O2 content (C) in mycelium after TX100 treatment. (D) Time-course of H2O2 contents in mycelium after TX100 treatment. Values are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. TX100 group).

Figure 5.

The induced H2O2 (A) and NO (B) production in the extractive fermentation and the influence of the donor, inhibitors and scavengers of NO and ROS (same procedure and dosage as specified in Figure 3 and Figure 4). Values are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. TX100 group).

2.5. Effect of NO and ROS on HA Production

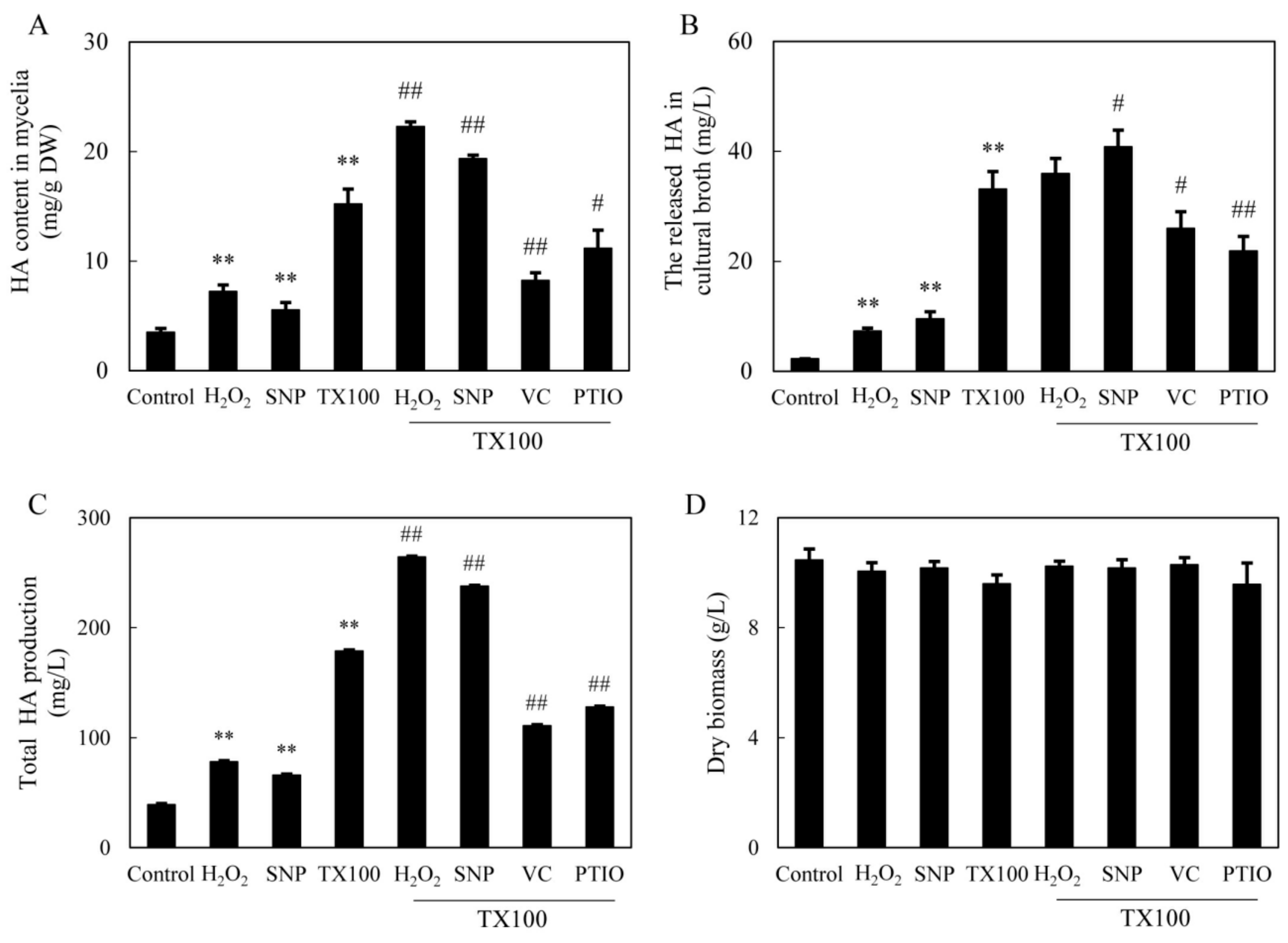

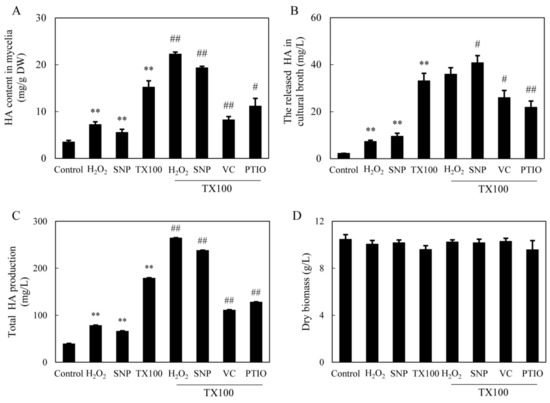

Although the deprivation of ROS and NO in the extractive fermentation did not cause the significant changes in membrane permeability (TX100+VC or TX100+PTIO in Figure S1), HA production in medium was inhibited markedly when ROS and NO generation was inhibited by VC and PTIO (TX100+VC or TX100+PTIO vs. TX100 in Figure 6A–C). Contrarily, the exogenous applied H2O2 and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) at 0.1 mM alone caused enhancement of intracellular and extracellular HA in the control culture without TX100 (Figure 6A, B). After the application of H2O2 in the extractive fermentation with TX100, HA content in the mycelia was increased significantly (TX100+H2O2 vs. TX100 in Figure 6A), whereas both intracellular and extracellular HA was stimulated by the addition of SNP (TX100+SNP vs. TX100 in Figure 6A,B). The addition of H2O2 or SNP in the extractive fermentation resulted in 7.8-, and 7.0-fold increase of HA production respectively, leading to total HA production 264.1 mg/L and 237.6 mg/L, respectively (Figure 6C). However, the mycelial biomass was not altered significantly by above treatments (Figure 6D). These results indicated the relationship between the induced signals (NO and ROS) and the total HA production (extracellular and intracellular) in the extractive fermentation.

Figure 6.

Effects of TX100 on HA content in mycelia (A), the released HA in medium (B) and total HA production (C) and mycelium biomass (D), and the influences of the donor, inhibitors and scavengers (same dosage as specified in Figure 3 and Figure 4) of NO and ROS in the extractive fermentation. TX100 was added at 25 g/L at 36 h of the 8-day fermentation. Values are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01 vs. control; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TX100 group).

2.6. Effect of NO and ROS on Gene Expression for HA Biosynthesis

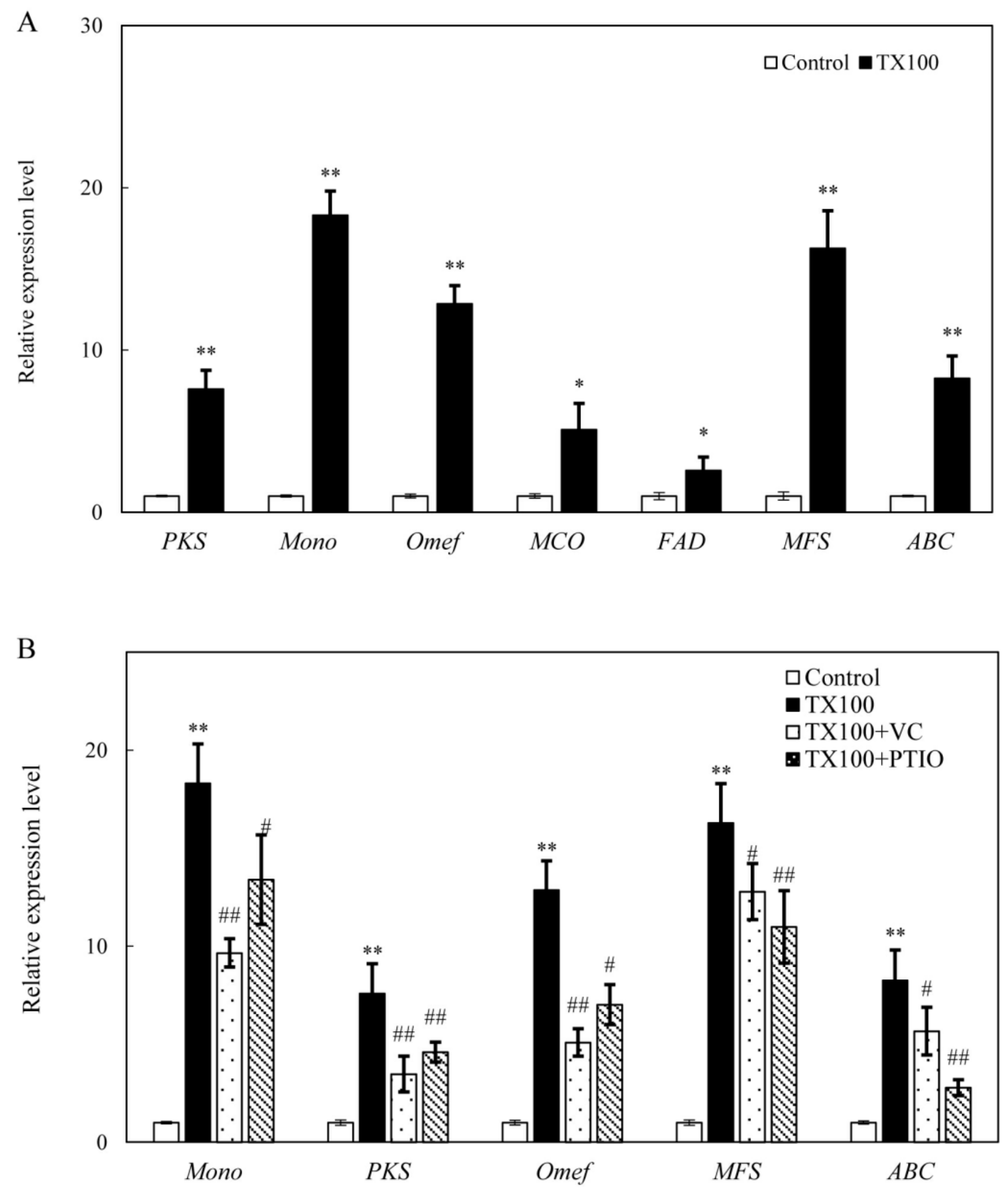

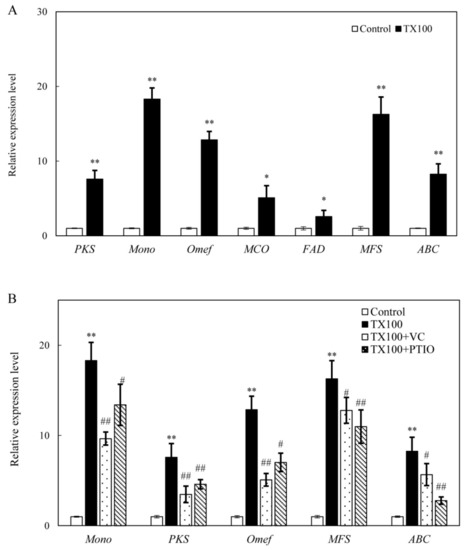

The expressions of some HA biosynthetic genes were significantly up-regulated after 24 h of the extractive fermentation (Figure 7). TX100 up-regulated gene expressions of polyketide synthase (PKS, 7.6-fold), monooxygenase (Mono, 18.3-fold), O-methyl-transferase (Omef, 12.9-fold), multicopper oxidase (MCO, 5.1-fold), FAD/FMN-containing dehydrogenase (FAD, 2.6-fold), major facilitator superfamily (MFS, 16.3-fold) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC, 8.3-fold) (Figure 7A). Furthermore, TX100-induced up-regulation of gene expressions could be abolished by VC and PTIO (Figure 7B). The induced expressions of biosynthetic genes including Mono, PKS and Omef were significantly decreased by VC, indicating the main involvement of ROS in HA biosynthesis. Simultaneously, the induced expressions of transporter genes (MFS and ABC) were repressed significantly after PTIO treatment (Figure 7B), suggesting the possible involvement of NO in the HA release in the medium.

Figure 7.

Effect of TX100 on the gene expressions for Shiraia HA biosynthesis (A) and the influences of the donor, inhibitors and scavengers (the dosage as specified in Figure 3 and Figure 4) of NO and ROS on the gene expressions in the mycelium (B). TX100 was added at 25 g/L on day 1.5 for 24 h of TX100 treatment. Values are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (**p < 0.01 vs. control; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TX100 group).

3. Discussion

The extent of enhancement of productivity and final product concentration of microbial metabolites is closely associated with the type of extractants and their interaction with the microbial cells in an extractive fermentation process [11]. Due to the benefit of using TX100 as elicitor in Shiraia cultures [17,18], we chose TX100 as the addictive to explore the mechanism of extractive fermentation. TX100, as a biocompatible nonionic surfactant has been applied in the perstractive fermentation of Monascus fungi to enhance their pigment production, since it has capabilities to alter the permeability of cell membrane for pigment exudation [13], as well as to solubilize the extracellular pigments in micelle aqueous solution [20]. In our previous report [18], TX100 could greatly alter the composition of membrane lipids and increase the ratio of unsaturated/saturated fatty acids of S. bambusicola mycelia. In this study, the improved permeability occurred after TX100 addition in the extractive fermentation (Figure 2), making the cell membranes more conducive to the export of intracellular HA. The intracellular HA was secreted into its fermentation broth (Figure 1E) and consecutively extracted into the nonaqueous micelle phase (Figure 1A). Since HA was confirmed to be self-toxic to the fungus in our recent paper [27], the transferring of HA into its nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution in extractive fermentation may alleviate self-toxicity of HA on fungal growth or the feedback inhibition of HA biosynthesis. Our results also demonstrated that increase of HA production in the extractive fermentation was from not only HA in the cultural broth, but also the stimulated biosynthesis of HA in mycelial cells (Figure 1). In this study, a higher production of HA (206.2 mg/L) was induced in the extractive fermentation, suggesting a new method for biotechnological process to improve HA yield, and this is also the first report on the induced generation of NO and ROS signals in the extractive fermentation (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

The previous studies have shown that NO was involved in elicited production of polyphenols in submerged cultures of Inonotus obliquus by pathogenic Alternaria alternate and Phellinus morii [28,29], and ganoderic triterpenoid production in the submerged cultures of Ganoderma lucidum [30]. Recently, similar reports on effects of induced NO by biotic elicitors from live Phoma sp. BZJ6 [31], Aspergillum niger [32] and Phytophthora boehmeriae [6] were made on S. bambusicola for hypocrellin and laccase production. Their studies suggested NO may be one of necessary signal molecules involved in metabolite production in S. bambusicola under the elicitation. In present study, the induced NO generation and its involvement in the biosynthesis of HA were verified in the extractive fermentation (Figure 3). The kinetics of TX100-induced NO production is similar to that in S. bambusicola cultures with fungal elicitors from A. niger [32] and Phoma sp. BZJ6 [31], suggesting NO is an early defense response of S. bambusicola to the stress. In our experiments, a shorter induction time (around 5 h) for the highest NO production was observed (Figure 3D), while it took about 7.5 h or 2 d for Shiraia cultures treated by fungal elicitors to achieve the highest NO production [31,32]. This discrepancy was likely due to different responses to abiotic and biotic elicitors. Although the source of NO in fungi remains obscure, NOS-like proteins have been identified in Neurospora crassa [33], Magnaporthe oryzae [34], and I. obliquus [29]. In our experiments, TX100-induced NO production in Shiraia mycelia was inhibited by both the NOS inhibitor L-NAME and NR inhibitor STD (Figure 3), suggesting the possible occurrence of a NOS-like enzyme and NR-dependent side reaction for the induced NO production [35].

TX100 and other surfactants disrupt cellular membrane and induce defense responses [21]. ROS generation including H2O2 production is one of the earliest fungal defense reactions. The induced ROS generation in Shiraia was further verified in our extractive fermentation (Figure 4). The suppression of TX100-induced NO production by DPI (NADPH oxidase inhibitor) and VC (ROS scavenger) suggested that ROS generation may play a regulation role in NO biosynthesis (Figure 5). However, the induced H2O2 production was not attenuated by NO inhibitors (L-NAME and STD) and scavenger PTIO. Although the accumulation of NO or H2O2 reached a plateau almost simultaneously around 5 h, the results suggested that NO production may occur downstream of ROS in S. bambusicola after TX100 treatment. This is in agreement with the finding from guard cells of Pisum sativum exposed to chitosan elicitor that NO inhibitors prevented the chitosan-induced NO levels but did not suppress the ROS production [36]. Recently, we found that ROS generation was one of early signals for the abiotic elicitation on Shiraia mycelium cultures for HA production, including the treatments of a low intensity ultrasound [7], a light/dark shift [37] and lanthanum (La3+) [38]. Therefore, the existence of interplays between NO and ROS might have been involved in HA biosynthesis in the extractive fermentation.

Previous researches on the transcriptomic profiles and the draft genome sequence of S. bambusicola [39,40] provided the putative biosynthetic genes for HA biosynthesis, including PKS for the catalyzing of the condensation of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA subunits, Mono and FAD for polyketide oxidations, and Omef for methyl modification on the HA backbone. In the extractive fermentation, TX100 up-regulated expressions of all of these HA biosynthetic genes (Figure 7). It is worth noting that the expressions of ABC and MFS were increased significantly, while both genes were reported to be involved in HA efflux [38,41]. Accordingly, the addition of TX100 not only enhanced HA contents in mycelia, but also stimulated HA exudation to the medium (Figure 1). The results from our present study have also shown that TX100-induced HA contents in mycelia was enhanced further by NO donor SNP and H2O2 but suppressed by NO scavenger PTIO and ROS scavenger VC (Figure 6C), whereas the released HA in medium was increased by SNP and deprived by PTIO and VC (TX100+SNP/PTIO/VC vs. TX100 in Figure 6B). These results demonstrated that HA production was regulated by endogenous NO and H2O2 in the extractive fermentation. The suppression of TX100-enhanced expressions of HA biosynthetic genes (Mono, PKS and Omef) and transporter genes (MFS and ABC) by NO scavenger PTIO and ROS scavenger VC (Figure 7) provided further support for the involvement of NO and ROS in HA biosynthesis. On the other hand, the combination of SNP/H2O2 in the extractive fermentation enhanced the HA production much more significantly than the two used separately (TX100 vs. TX100+ SNP/H2O2 in Figure 6). From biotechnological viewpoint, the combination of the exogenous donors (SNP and H2O2) of these signal molecules (NO or ROS) in the extractive fermentation is of great practical value to stimulate fungal production in mycelium cultures.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains and Culture Conditions

The HA-yielding strain Shiraia sp. S9 was isolated from bamboo (Brachystachyum densiorum) twigs [42] and registered in China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center as No. CGMCC 16369. The strain was initially incubated on a potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium in a petri dish at 28 °C for 6 day, as previously reported [42]. The subsequent experiments were carried out in shake-flask cultures on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm and at 28 °C for an overall culture period of 8-10 days. For extractive fermentation in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution, specific amount of nonionic surfactant TX100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 25 g/L was applied to the shake-flask cultures after 36 h of the initial culture according to our previous study [18].

4.2. Membrane Permeabilization Assay

Fungal membrane permeabilization was observed using the fluorescence dye SYTOX Green, a high-affinity nucleic acid stain fluorescent dye [43]. After 36 h of the initial culture, fungal mycelium was incubated in the extractive medium with 0.5 μM SYTOX Green, the fluorescence was analyzed by live cell imaging using an Olympus Cell’R IX81 fluorescence microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA) with excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission wavelength of 538 nm. The relative fluorescence value is defined to the ratio of fluorescence intensity at a given time to that at 0 min.

4.3. Detection of NO and ROS Generation

For the detection of NO generation in fungal mycelia, the NO-specific fluorescent probe DAF-2 DA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used [44]. After 36 h of mycelium culture, DAF-2 DA was added to the culture at 30 min prior to TX100 treatment. The fluorescence was observed using an Olympus Cell’R IX81 fluorescence microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA) with excitation/emission wavelengths (470 nm/525 nm). NO contents in mycelia were measured by Griess assay using a Total Nitric Oxide Assay Kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China). On the other hand, ROS accumulation in the mycelia was detected using DCFH-DA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) under an Olympus Cell’R IX81 fluorescence microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA) with excitation/emission wavelengths (485 nm/528 nm). The content of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in mycelium was determined as previously described by Sun et al. (2018) [37]. The mycelia (0.5 g, fresh weight, FW) were ground into homogenate with 5 mL of 0.05 M PBS buffer (pH 7.8) in ice bath and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was added to 750 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 1.5 mL 1 M KI. The absorbance was read by a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan) at 390 nm.

4.4. Inhibition Experiments on NO and ROS Effects

To study the effects of NO signal during the extractive fermentation by TX100, SNP and PTIO were used as NO donor and scavenger, respectively. L-NAME and STD were used, respectively, as a NOS inhibitor and NR inhibitor. The NO donor and inhibitors used in the experiments were chosen based on previous studies regarding roles of NO in fungi [6,29,45]. l-NAME (100 μM), STD (100 μM) and PTIO (100 μM) were added to the culture at 30 min prior to, and SNP (0.1 mM) simultaneously with TX100 treatment. On the other hand, to investigate the role of ROS generation during the extractive fermentation, the exogenous H2O2 (0.1 mM) was used as ROS donor. NOX inhibitor DPI (5 μM) and a scavenger VC (10 μM) were used to pretreat for 30 min in mycelium cultures before the TX100 addition according to our previous study [38].

4.5. Extraction and Quantification of HA

The extractive fermentation in Triton X-100 micelle aqueous solution was carried out for 8 d. The fermentation broth was subjected to centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min to separate the mycelia. The extracellular supernatant was heated (75 °C) until the formation of two-phase cloud point system: a surfactant-rich phase (coacervate phase) and a dilute phase, and until reaching the equilibrium (1 h). To determine extracellular HA, the extracellular broth in the two phases (50 mL) was exhaustively extracted with ethyl acetate (150 mL). The organic extracts were evaporated in vacuo to afford a residue and re-dissolved in methanol for HPLC analysis. The intracellular HA extraction and quantification were based on the method described in our previous report [7]. HPLC analysis was carried out using Agilent 1260 HPLC systems equipped with 250 × 4.6 mm Agilent HC-C18 column. The sample was eluted with a mobile phase (acetonitrile: water at 65: 35, v/v) at 1 mL/min and monitored at 465 nm. HA was quantified with genuine standard provided by the Chinese National Compound Library (Shanghai, China). Total HA production refers to the sum of intracellular and extracellular HA.

4.6. Quantitative Real-time PCR

The primers of target genes for HA biosynthesis and internal reference gene (18S ribosomal RNA) were listed in Table S1. The relative gene expressions were measured using RT-qPCR on the basis of our previous reports [7].

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Each group consists of triplicate experiments (ten flasks per replicate). Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnet’s multiple comparison tests were performed for the results. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

Currently, the regulation of surfactant addition on fungal metabolites has not been well explored. In this study, we have successfully demonstrated that the extractive fermentation by TX100 could enhance greatly HA production in Shiraia cultures, suggesting an effective process strategy to mycelium cultures. The present study clearly showed the enhanced production of HA in the extractive fermentation is strongly dependent on the induced permeabilization and the signals including NO and ROS. Our finding indicates NO and H2O2 could serve as new signals for the fungal production by microbial fermentation in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution. Both NO and H2O2 not only participated in the up-regulation of HA biosynthetic genes, but also enhanced transporter genes (MFS and ABC) by NO for HA exudation. Since the extractive fermentation has been a successful process strategy for enhancing fungal production, the elucidation of signal roles will not only bring about the understanding of the response mechanisms during the process but also effective strategies for fungal production of desired metabolites.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/3/882/s1.

Author Contributions

X.P.L., Y.W. and Y.J.M. performed the experiments; L.P.Z. and J.W.W. designed the research and analyzed the data. L.P.Z., J.W.W., Y.W. and X.P.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773696 and 81473183), the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX17_2042) and the Priority Academic Program Development of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutes (PAPD).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| DAF-2 DA | 4, 5-diaminofluorescein diacetate |

| DCFH-DA | 2, 7-dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate |

| DPI | diphenylene iodonium |

| FAD | FAD/FMN-containing dehydrogenase |

| FW | fresh weight |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HA | hypocrellin A |

| L-NAME | Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester |

| MCO | multicopper oxidase |

| MFS | major facilitator superfamily |

| Mono | monooxygenase |

| NO | nitric oxide synthase |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| NR | nitrate reductase |

| Omef | O-methyl-transferase |

| PDA | potato dextrose agar |

| PDT | photodynamic therapy |

| PKS | polyketide synthase |

| PTIO | 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SNP | sodium nitroprusside |

| STD | sodium tungstate dehydrate |

| TX100 | Triton X-100 |

| VC | vitamin C |

References

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, N.H.; Wan, Q.; Li, M.F. EPR studies of singlet oxygen (1O2) and free radicals (O2−, OH, HB−) generated during photosensitization of hypocrellin B. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1993, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio-Srichan, S.; Oudrhiri, N.; Bennaceur-Griscelli, A.; Turhan, A.G.; Dumas, P.; Refregiers, M. Toxicity and phototoxicity of hypocrellin A on malignant human cell lines, evidence of a synergistic action of photodynamic therapy with Imatinib mesylate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B-Biol. 2010, 99, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, E.M.; Morgan, B.J.; Mulrooney, C.A.; Carroll, P.J.; Kozlowski, M.C. Perylenequinone natural products: Total synthesis of hypocrellin A. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.W.; Mao, L.W.; Liang, H.L.; Zhang, Z.B.; Wang, Y.; Yan, R.M. Simultaneous determination of six perylenequinones in Shiraia sp. Slf14 by HPLC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2017, 40, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Liang, Z.Q.; Zou, X.; Han, Y.F.; Liang, J.D.; Yu, J.P.; Chen, W.H.; Wang, Y.R.; Sun, C.L. Effects of microbial elicitor on production of hypocrellin by Shiraia bambusicola. Folia Microbiol. 2013, 58, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Sun, C.L.; Wang, B.G.; Wang, Y.M.; Dong, B.; Liu, J.H.; Xia, J.B.; Xie, W.J.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.K.; et al. Response mechanism of hypocrellin colorants biosynthesis by Shiraia bambusicola to elicitor PB90. AMB Express 2019, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.X.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.W. Enhanced production of hypocrellin A by ultrasound stimulation in submerged cultures of Shiraia bambusicola. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 38, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.J.; Xu, Z.C.; Deng, H.X.; Guan, Z.B.; Liao, X.R.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X.H.; Cai, Y.J. Influences of light on growth, reproduction and hypocrellin production by Shiraia sp. SUPER-H168. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Sun, C.X.; Wang, J.W. Enhanced production of Hypocrellin A in submerged cultures of Shiraia bambusicola by red light. Photochem. Photobiol. 2019, 95, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Shen, X.Y.; Fan, L.; Gao, J.; Hou, C.L. High-efficiency biosynthesis of hypocrellin A in Shiraia sp. using gamma-ray mutagenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2016, 100, 4875–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Dai, Z.W. Extractive microbial fermentation in cloud point system. Enzym. Microb. Tech. 2010, 46, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinze, W.L.; Pramauro, E. A critical review of surfactant-mediated phase separations (cloud-point extractions): Theory and applications. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1993, 24, 133–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Wu, Z.Q.; Qi, H.S.; Wang, Z.L. Export of intracellular Monascus pigments by two-stage microbial fermentation in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 162, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Oyervides, L.; Oliveira, J.; Sousa-Gallagher, M.; Méndez-Zavala, A.; Montañez, J.C. Perstraction of intracellular pigments through submerged fermentation of Talaromyces spp. in a surfactant rich media: A novel approach for enhanced pigment recovery. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.Y.; Qian, C.; Wang, Z.L.; Xu, J.H.; Yang, R.D.; Qi, H.S. Investigation of extractive microbial transformation in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution using response surface methodology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Zhao, F.S.; Hao, X.Q.; Chen, D.J.; Li, D.T. Microbial transformation of hydrophobic compound in cloud point system. J. Mol. Catal. B-Enzym. 2004, 27, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.J.; Liao, X.H.; Liang, X.R.; Ding, Y.R.; Sun, J.; Zhang, D.B. Induction of hypocrellin production by Triton X-100 under submerged fermentation with Shiraia sp. SUPER-H168. New Biotech. 2011, 28, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.Y.; Zhang, M.Y.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.W. Transcriptomic responses involved in enhanced production of hypocrellin A by addition of Triton X-100 in submerged cultures of Shiraia bambusicola. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, N.V.; Ju, L.K. Promoting pellet growth of Trichoderma reesei Rut C30 by surfactants for easy separation and enhanced cellulase production. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2012, 50, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Wu, Z.Q.; Qi, H.S.; Wang, Z.L. Perstraction of intracellular pigments by submerged cultivation of Monascus in nonionic surfactant micelle aqueous solution. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H. Effects of nonionic and ionic surfactants on survival, oxidative stress, and cholinesterase activity of planarian. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droge, W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendehenne, D.; Hancock, J.T. New frontiers in nitric oxide biology in plant. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 507–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.W.; Zheng, L.P.; Zhang, B.; Zou, T. Stimulation of artemisinin synthesis by combined cerebroside and nitric oxide elicitation in Artemisia annua hairy roots. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 85, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Zheng, L.P.; Wu, J.Y.; Tan, R.X. Involvement of nitric oxide in oxidative burst, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activation and Taxol production induced by low-energy ultrasound in Taxus yunnanensis cell suspension cultures. Nitric Oxide 2006, 15, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Zheng, L.P.; Tian, H.; Wang, J.W. Synergistic effects of ultraviolet-B and methyl jasmonate on tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B-Biol. 2016, 159, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Zheng, L.P.; Wang, J.W. Bacteria associated with Shiraia fruiting bodies influence fungal production of hypocrellin A. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.F.; Miao, K.J.; Zhang, Y.X.; Pan, S.Y.; Zhang, M.M.; Jiang, H. Nitric oxide mediates the fungal-elicitor-enhanced biosynthesis of antioxidant polyphenols in submerged cultures of Inonotus obliquus. Microbiology 2009, 155, 3440–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Xi, Q.; Xu, Q.; He, M.H.; Ding, J.N.; Dai, Y.C.; Keller, N.P.; Zheng, W.F. Correlation of nitric oxide produced by an inducible nitric oxide synthase-like protein with enhanced expression of the phenylpropanoid pathway in Inonotus obliquus cocultured with Phellinus morii. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 4361–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Zhong, X.; Lian, D.H.; Zheng, Y.M.; Wang, H.Z.; Liu, X. Triterpenoid biosynthesis and the transcriptional response elicited by nitric oxide in submerged fermenting Ganoderma lucidum. Process Biochem. 2017, 60, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Sun, C.L.; Wang, J.; Xie, W.J.; Wang, B.Q.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Fan, Y.H. Conditions and regulation of mixed culture to promote Shiraia bambusicola and Phoma sp. BZJ6 for laccase production. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Liang, J.D.; Han, Y.F.; Yu, J.P.; Liang, Z.Q. Nitric oxide mediates hypocrellin accumulation induced by fungal elicitor in submerged cultures of Shiraia bambusicola. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninnemann, H.; Maier, J. Indications for the occurrence of nitric oxide synthases in fungi and plants and the involvement in photoconidiation of Neurospora crassa. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996, 64, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samalova, M.; Johnson, J.; IIIes, M.; Kelly, S.; Fricker, M.; Gurr, S. Nitric oxide generated by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae drives plant infection. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos, A.T.; Ramos, M.S.; Marcos, J.F.; Carmona, L.; Strauss, J.; Cánovas, D. Nitric oxide synthesis by nitrate reductase is regulated during development in Aspergillus. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 99, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, N.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Puli, M.R.; Raghavendra, A.S. Nitric oxide production occurs downstream of reactive oxygen species in guard cells during stomatal closure induced by chitosan in abaxial epidermis of Pisum sativum. Planta 2009, 229, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.X.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.W. Improved hypocrellin A production in Shiraia bambusicola by light-dark shift. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B-Biol. 2018, 182, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.S.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.W. Lanthanum elicitation on hypocrellin A production in mycelium cultures of Shiraia bambusicola is mediated by ROS generation. J. Rare Earth. 2019, 37, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.B.; Yan, R.M.; Zhu, D. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Shiraia sp. strain Slf14, a novel endophytic fungus producing huperzine A and hypocrellin A. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e00011–e00014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Lin, X.; Qi, S.S.; Luo, Z.M.; Chen, S.L.; Yan, S.Z. De novo transcriptome assembly in Shiraia bambusicola to investigate putative genes involved in the biosynthesis of hypocrellin A. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.X.; Gao, R.J.; Liao, X.R.; Cai, Y.J. Characterization of a major facilitator superfamily transporter in Shiraia bambusicola. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.J.; Zheng, L.P.; Wang, J.W. Inducing perylenequinone production from a bambusicolous fungus Shiraia sp. S9 through co-culture with a fruiting body-associated bacterium Pseudomonas fulva SB1. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevissen, K.; Terras, F.R.G.; Broekaert, W.F. Permeabilization of fungal membranes by plant defensins inhibits fungal growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 5451–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrion-Gomez, J.L.; Benito, E.P. Flux of nitric oxide between the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea and the host plant. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.N.; Gao, Z.J.; Wang, C.F.; Huang, L.L.; Kang, Z.S.; Zhang, H.C. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species coordinately regulate the germination of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici urediniospores. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).