Sexual Hormones Determination in Biofluids by In-Vial Polycaprolactone Thin-Film Microextraction Coupled with HPLC-MS/MS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Development of the In-Vial TF-ME Procedure in Urine

2.2. Development of the In-Vial TF-ME Procedure in BSA and FBS

2.3. Analytical Evaluation of the In-Vial TF-ME Followed by the HPLC-MS/MS Method

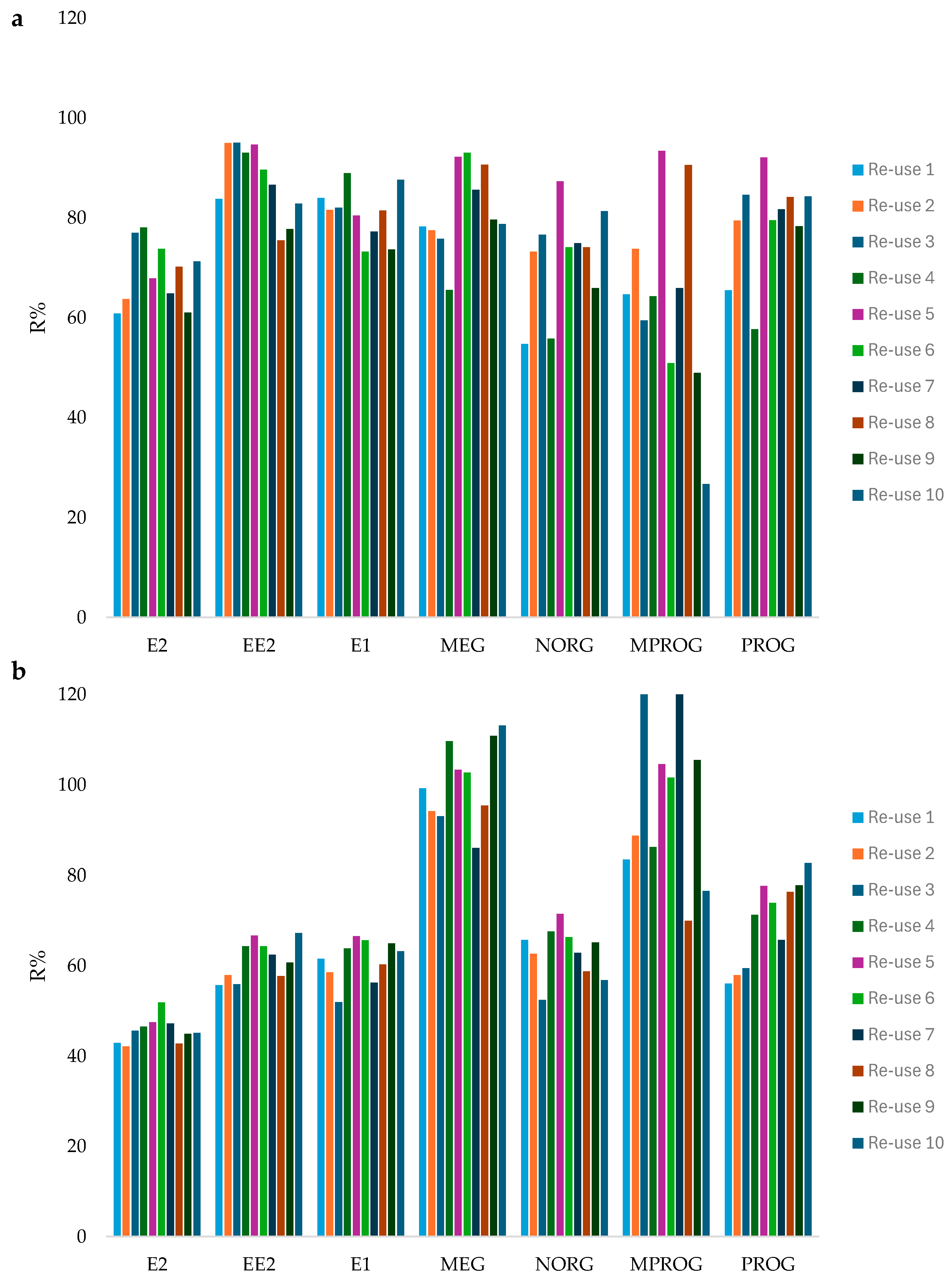

2.4. Reusability of the In-Vial PCL Film

2.5. Greenness Evaluation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. Biofluids

3.3. Preparation of In-Vial Polycaprolactone Film

3.4. In-Vial Thin-Film Microextraction (In-Vial TF-ME)

3.4.1. Development of the Procedure in Synthetic Urine

3.4.2. Final Procedure in Urine

3.4.3. Final Procedure in Protein Matrices

3.5. Analytical Performance of the In-Vial TF-ME Followed by HPLC-MS/MS Method

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiménez-Skrzypek, G.; Ortega-Zamora, C.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Borges, J. Miniaturized Green Sample Preparation Approaches for Pharmaceutical Analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 207, 114405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela, H.; Gionfriddo, E. Evolution of Green Sample Preparation: Fostering a Sustainable Tomorrow in Analytical Sciences. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 7840–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peris-Pastor, G.; Azorín, C.; Grau, J.; Benedé, J.L.; Chisvert, A. Miniaturization as a Smart Strategy to Achieve Greener Sample Preparation Approaches: A View through Greenness Assessment. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, S.; Garrigues, S.; de la Guardia, M. Green Analytical Chemistry. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2008, 27, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lorente, Á.I.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S.; Zuin, V.G.; Ozkan, S.A.; Psillakis, E. The Ten Principles of Green Sample Preparation. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 148, 116530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Pawliszyn, J. Thin-Film Microextraction Offers Another Geometry for Solidphase Microextraction. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 39, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarurwa, H. Advances in Thin Film Micro-Extraction (TFME) of Selected Organic Pollutants, and the Evaluation of the Sample Preparation Procedures Using the AGREEprep Green Metric Tool. Microchem. J. 2024, 203, 110938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Arain, M.B.; Shahzad, S.; Soylak, M. Various Eco-Friendly and Green Approaches in Thin Film Microextraction Techniques for Sample Analysis—A Review. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 190, 118292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, A.; Jiménez-Abizanda, A.I.; Pino, V.; Gutiérrez-Serpa, A. In Vial Thin-Film Solid-Phase Microextraction Using Silver Nanoparticles as Coating for the Determination of Phenols in Waters. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hua, R.; Wu, X.; Xue, J. Development of a Polyurethane-Coated Thin Film Solid Phase Microextraction Device for Multi-Residue Monitoring of Pesticides in Fruit and Tea Beverages. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, 2200661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taima-Mancera, I.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, M.J.; Pasán, J.; Pino, V. Saliva Analysis Using Metal–Organic Framework-Coated Miniaturized Vials. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1345, 343663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, F.; Cerviani, V.; Fontàs, C.; Speltini, A.; Profumo, A.; Anticò, E. In-Vial Polycaprolactone Thin Film for Sampling and Microextraction of Sexual Hormones in Environmental Waters and Wastewaters Followed by HPLC-MS/MS. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1362, 344164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizan, M.M.H.; Gurave, P.M.; Rastgar, M.; Rahimpour, A.; Srivastava, R.K.; Sadrzadeh, M. “Biomass to Membrane”: Sulfonated Kraft Lignin/PCL Superhydrophilic Electrospun Membrane for Gravity-Driven Oil-in-Water Emulsion Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 41961–41976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manholi, S.; Athiyanathil, S. Poly (ε-Caprolactone)-Based Porous Membranes for Filtration Applications—Effect of Solvents on Precipitation Kinetics, Performance, and Morphology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, V.; Hoyos, P.; Castoldi, L.; Domínguez De María, P.; Alcántara, A.R. 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF): A Biomass-Derived Solvent with Broad Application in Organic Chemistry. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, L.; Arismendi, D.; Richter, P. Integration of Rotating Disk Sorptive Extraction and Dispersive-Solid Phase Extraction for the Determination of Estrogens and Their Metabolites in Urine by Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2023, 185, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speltini, A.; Merlo, F.; Maraschi, F.; Villani, L.; Profumo, A. HA-C@silica Sorbent for Simultaneous Extraction and Clean-up of Steroids in Human Plasma Followed by HPLC-MS/MS Multiclass Determination. Talanta 2021, 221, 121496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.Y.; Zhen, C.Q.; He, Y.J.; Cui, Y.Y.; Yang, C.X. Solvent and Monomer Regulation Synthesis of Core-Shelled Magnetic β-Cyclodextrin Microporous Organic Network for Efficient Extraction of Estrogens in Biological Samples Prior to HPLC Analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1728, 464991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, T.L.; Williams, D.A.; Roche, V.F.; Zito, S.W. Foye’s Principles of Medicinal Chemistry; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781609133450. [Google Scholar]

- Struck-Lewicka, W.; Karpińska, B.; Rodzaj, W.; Nasal, A.; Wielgomas, B.; Markuszewski, M.J.; Siluk, D. Development of the Thin Film Solid Phase Microextraction (TF-SPME) Method for Metabolomics Profiling of Steroidal Hormones from Urine Samples Using LC-QTOF/MS. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1074263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravitte, A.; Archibald, T.; Cobble, A.; Kennard, B.; Brown, S. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Applications for Quantification of Endogenous Sex Hormones. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2021, 35, e5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrieva, E.; Temerdashev, A.; Azaryan, A.; Gashimova, E. Quantification of Steroid Hormones in Human Urine by DLLME and UHPLC-HRMS Detection. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1159, 122390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turazzi, F.C.; Morés, L.; Carasek, E.; Barra, G.M.d.O. Polyaniline-Silica Doped with Oxalic Acid as a Novel Extractor Phase in Thin Film Solid-Phase Microextraction for Determination of Hormones in Urine. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, 2300280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Carmo, S.N.; Merib, J.; Carasek, E. Bract as a Novel Extraction Phase in Thin-Film SPME Combined with 96-Well Plate System for the High-Throughput Determination of Estrogens in Human Urine by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Fluorescence Detection. J. Chromatogr. B 2019, 1118–1119, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Duan, L.; Shi, L.; Liu, E.; Fan, J. Novel Ferrofluid Based on Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents for Separation and Analysis of Trace Estrogens in Environmental Water and Urine Samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 4057–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaipet, T.; Fresco-Cala, B.; Thammakhet-Buranachai, C.; Lucena, R.; Cárdenas, S. Sustainable Hybrid Sorbent Based on a Thin Film Gelatin Coating over Cellulose Paper for the Determination of Steroid Hormones in Urine and Environmental Water Samples. Microchem. J. 2025, 209, 112769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA. ICH Guideline M10 on Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis—Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) (EMA/CHMP/ICH/660315/2022). 2022. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-guideline-m10-bioanalytical-method-validation-and-study-sample-analysis-frequently-asked-questions-faq_en.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Psillakis, E. AGREEprep—Analytical Greenness Metric for Sample Preparation. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 149, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, R.; Gutiérrez-Serpa, A.; Pino, V.; Sajid, M. A Tool to Assess Analytical Sample Preparation Procedures: Sample Preparation Metric of Sustainability. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1707, 464291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatrochová, S.; Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela, H.; Catalá-Icardo, M.; Simó-Alfonso, E.F.; Lhotská, I.; Šatínský, D.; Herrero-Martínez, J.M. Development of Hybrid Monoliths Incorporating Metal–Organic Frameworks for Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction Coupled with Liquid Chromatography for Determination of Estrogen Endocrine Disruptors in Water and Human Urine Samples. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, N.A.; Saad, B.; Mohamed, M.H.; Wilson, L.D.; Latiff, A.A. Cyclodextrin Based Polymer Sorbents for Micro-Solid Phase Extraction Followed by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry in Determination of Endogenous Steroids. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1543, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, F.; Occhipinti, S.; Gontero, P.; Cavalera, S.; Chiarello, M.; Baggiani, C.; Anfossi, L. Detection of Urinary Prostate Specific Antigen by a Lateral Flow Biosensor Predicting Repeat Prostate Biopsy Outcome. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 325, 128812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analytes | LLQC | LQC | MQC | HQC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | 84 (14) | 66 (7) | 79 (9) | 86 (5) |

| EE2 | 100 (7) | 94 (14) | 95 (6) | 97 (4) |

| E1 | 89 (17) | 111 (7) | 81 (7) | 90 (1) |

| MEG | 66 (17) | 65 (17) | 93 (10) | 105 (11) |

| NORG | 100 (17) | 83 (6) | 80 (11) | 88 (1) |

| MPROG | 100 (18) | 89 (14) | 109 (14) | 96 (16) |

| PROG | 80 (12) | 71 (6) | 89 (6) | 102 (12) |

| Analytes | 80 g L−1 | 40 g L−1 (a) | 27 g L−1 (b) | 20 g L−1 (c) | 16 g L−1 (d) | 10 g L−1 (e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | 9 (16) | 16 (14) | 37 (16) | 55 (6) | 63 (2) | 56 (17) |

| EE2 | 20 (22) | 28 (14) | 56 (3) | 77 (10) | 79 (10) | 78 (10) |

| E1 | 11 (21) | 21 (18) | 55 (8) | 71 (9) | 73 (1) | 71 (11) |

| MEG | 37 (17) | 48 (18) | 108 (13) | 122 (8) | 123 (13) | 97 (4) |

| NORG | 16 (18) | 24 (17) | 53 (7) | 65 (3) | 72 (4) | 78 (5) |

| MPROG | 37 (17) | 46 (17) | 84 (15) | 85 (17) | 70 (17) | 83 (22) |

| PROG | 25 (15) | 36 (29) | 43 (8) | 57 (3) | 63 (1) | 58 (9) |

| Analytes | 200 ng mL−1 | 50 ng mL−1 | 10 ng mL−1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSA | FBS | BSA | FBS | BSA | FBS | |

| E2 | 55 (6) | 66 (8) | 56 (8) | 86 (2) | 56 (2) | 63 (8) |

| EE2 | 77 (10) | 91 (22) | 79 (7) | 107 (1) | 68 (9) | 86 (1) |

| E1 | 71 (9) | 82 (19) | 70 (3) | 97 (1) | 74 (8) | 95 (7) |

| MEG | 122 (8) | 88 (20) | 102 (7) | 121 (1) | 102 (13) | 114 (18) |

| NORG | 65 (3) | 82 (20) | 72 (7) | 87 (4) | 76 (5) | 62 (4) |

| MPROG | 85 (17) | 90 (15) | 98 (18) | 95 (10) | 97 (18) | 92 (3) |

| PROG | 57 (3) | 88 (17) | 73 (6) | 96 (1) | 76 (2) | 67 (6) |

| Analytes | Urine | BSA | FBS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDL (ng mL−1) | MQL (ng mL−1) | MDL (ng mL−1) | MQL (ng mL−1) | MDL (ng mL−1) | MQL (ng mL−1) | |

| E2 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| EE2 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.2 |

| E1 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| MEG | 0.65 | 1.96 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| NORG | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| MPROG | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| PROG | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Merlo, F.; Anselmi, S.; Speltini, A.; Fontàs, C.; Anticó, E.; Profumo, A. Sexual Hormones Determination in Biofluids by In-Vial Polycaprolactone Thin-Film Microextraction Coupled with HPLC-MS/MS. Molecules 2026, 31, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020255

Merlo F, Anselmi S, Speltini A, Fontàs C, Anticó E, Profumo A. Sexual Hormones Determination in Biofluids by In-Vial Polycaprolactone Thin-Film Microextraction Coupled with HPLC-MS/MS. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020255

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerlo, Francesca, Silvia Anselmi, Andrea Speltini, Clàudia Fontàs, Enriqueta Anticó, and Antonella Profumo. 2026. "Sexual Hormones Determination in Biofluids by In-Vial Polycaprolactone Thin-Film Microextraction Coupled with HPLC-MS/MS" Molecules 31, no. 2: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020255

APA StyleMerlo, F., Anselmi, S., Speltini, A., Fontàs, C., Anticó, E., & Profumo, A. (2026). Sexual Hormones Determination in Biofluids by In-Vial Polycaprolactone Thin-Film Microextraction Coupled with HPLC-MS/MS. Molecules, 31(2), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020255