One-Pot Synthesis of Aminodiperoxides from 1,5-Diketones, Geminal Bishydroperoxides and Ammonium Acetate

Abstract

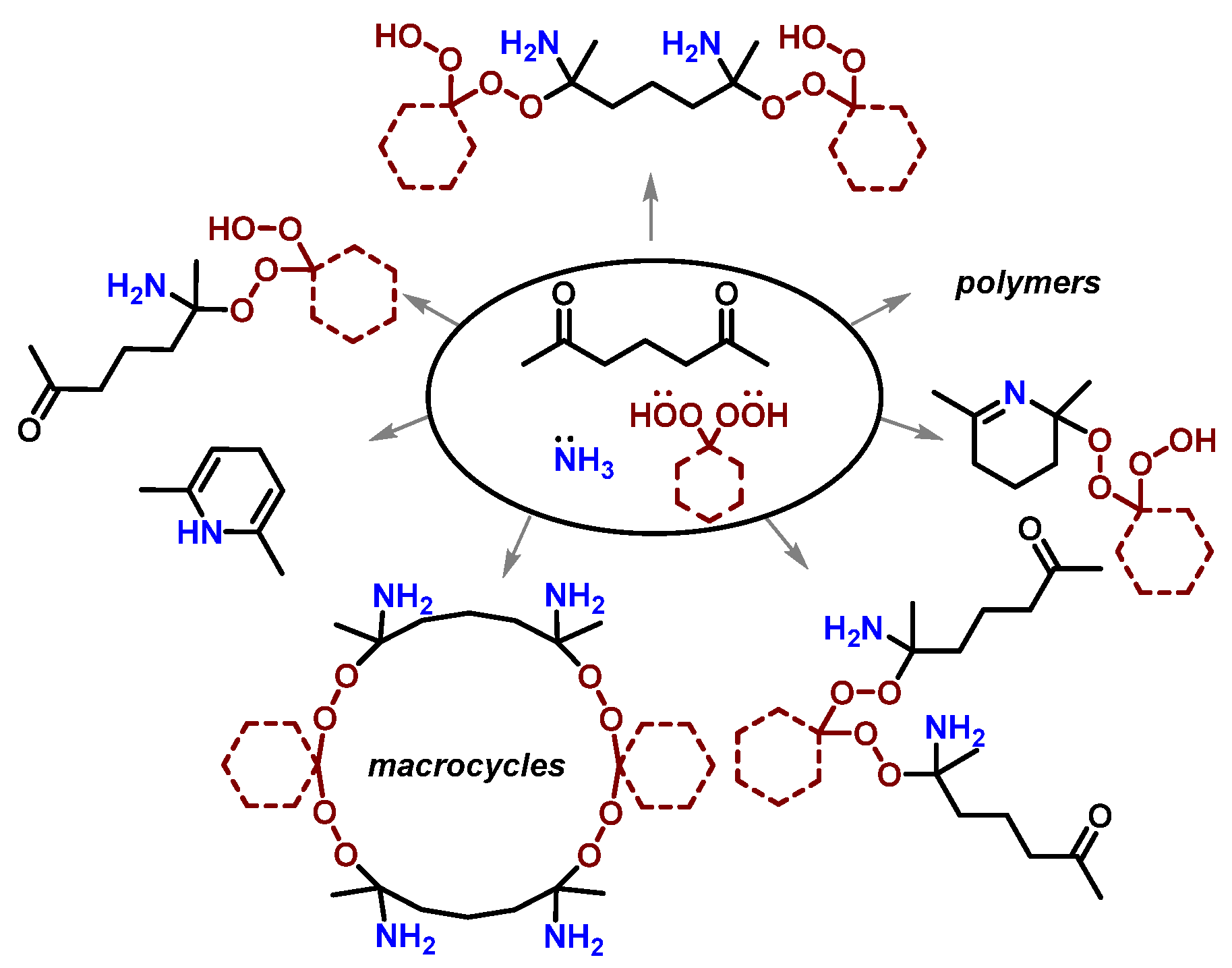

1. Introduction

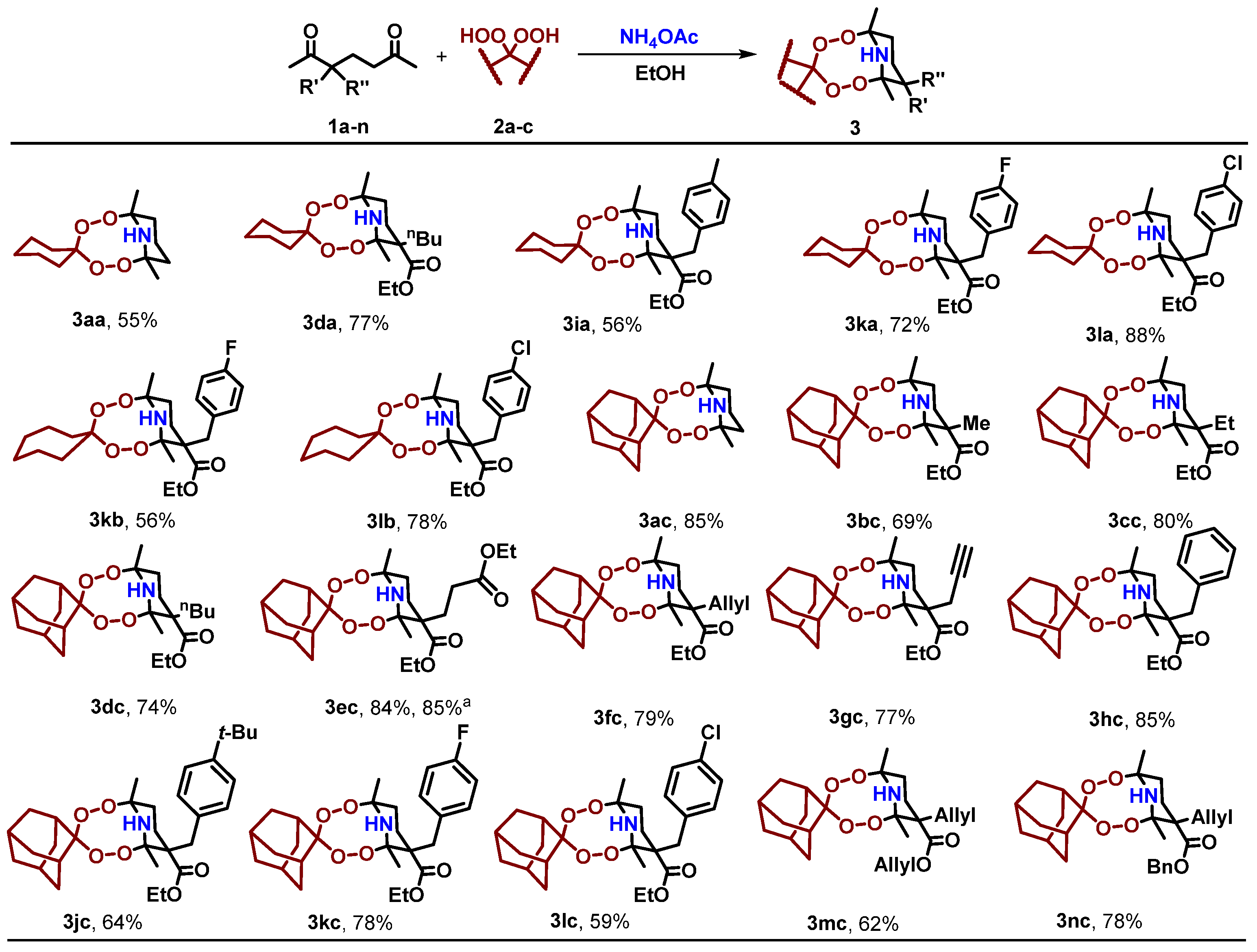

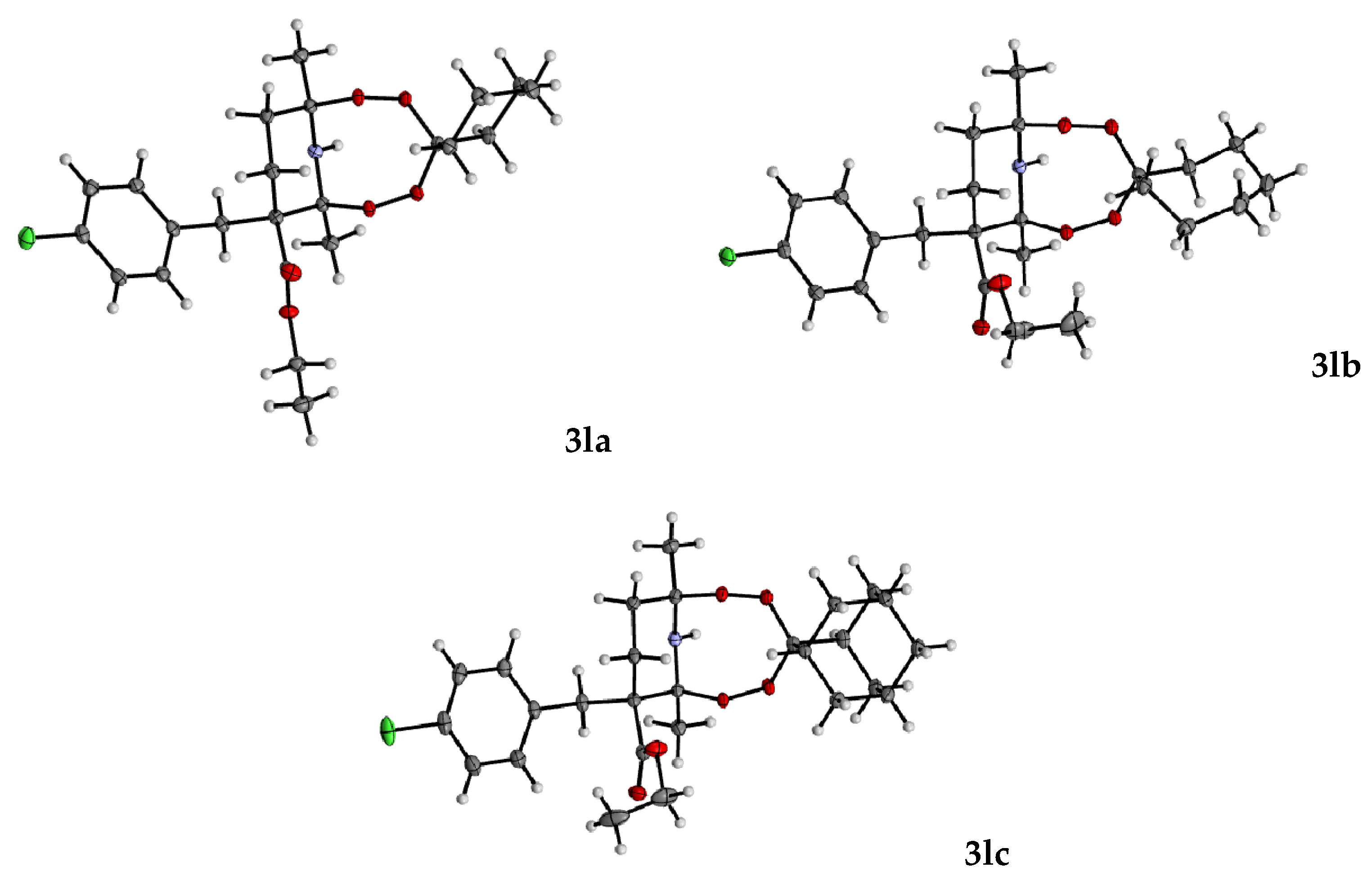

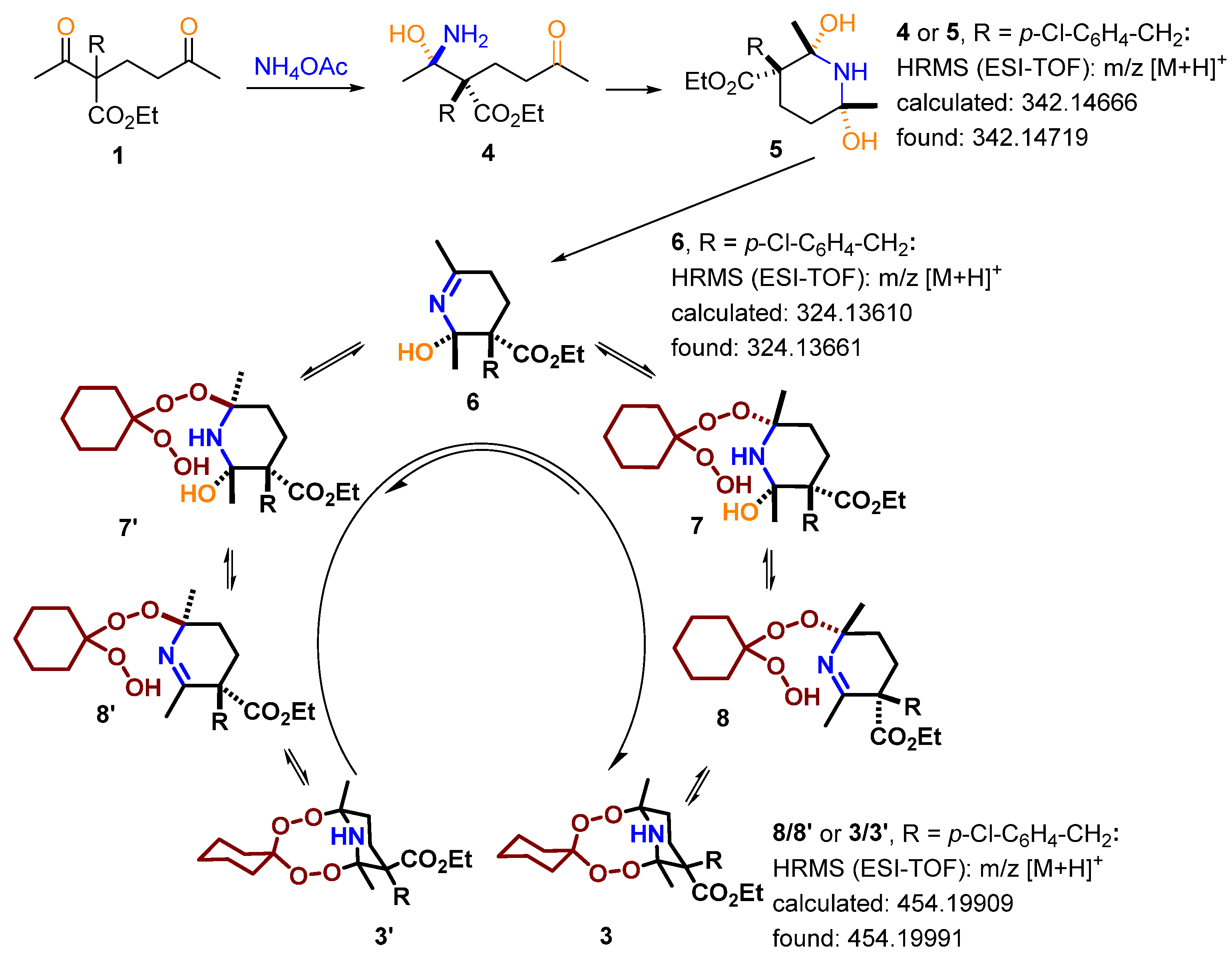

2. Results and Discussion

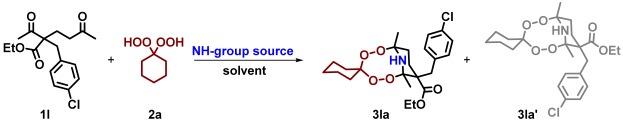

2.1. Synthesis of the Aminodiperoxides

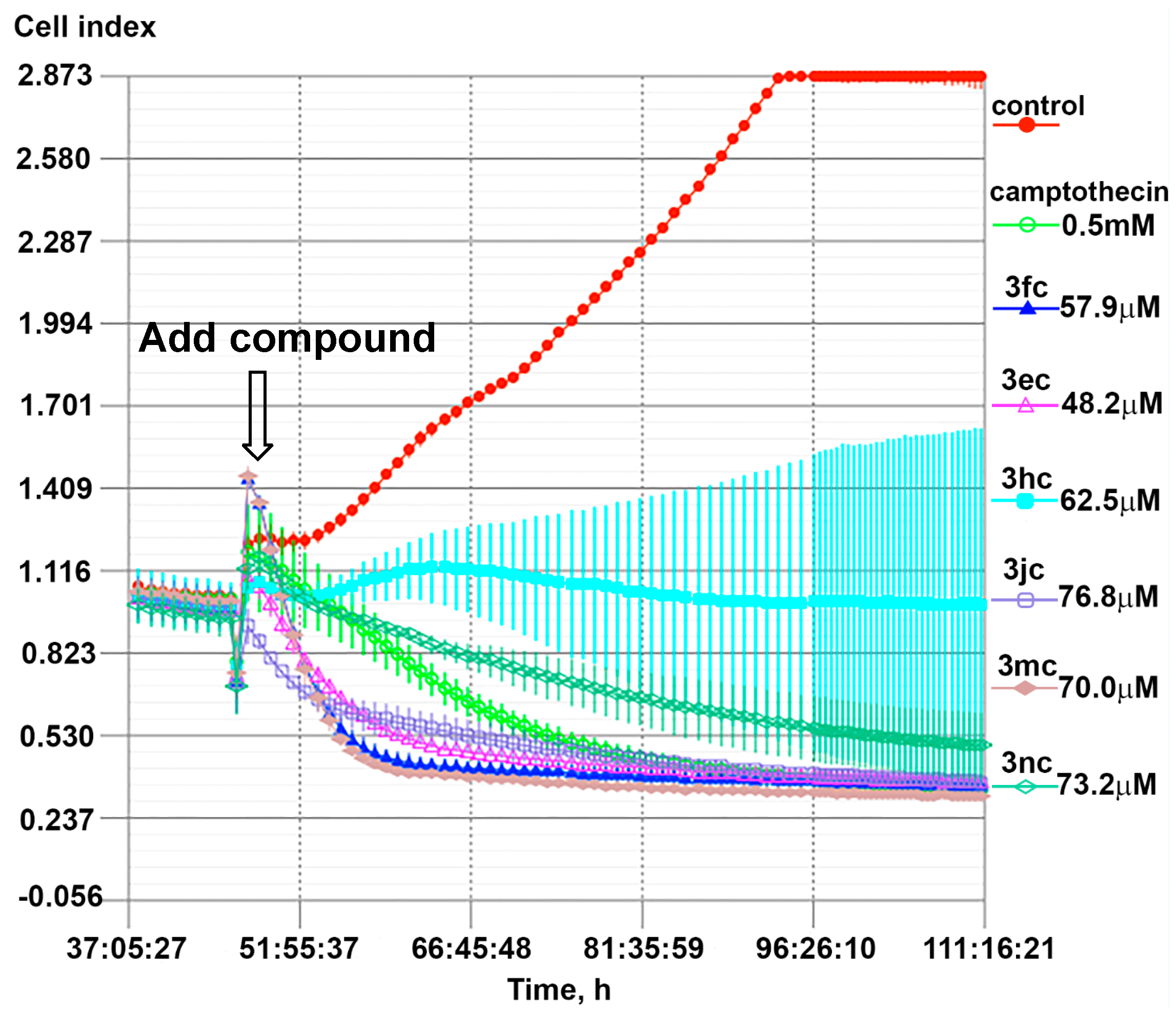

2.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of the Aminodiperoxides

2.3. In Vitro Fungicidal Activity of the Aminodiperoxides

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of 1,5-Diketones 1a–n

3.2. Synthesis of Bishydroperoxides

3.3. Procedure for the Synthesis of Aminodiperoxide 3la with Use NH3, Ammonium Salts and 1,1-Dihydroperoxycyclohexane 2a (Table 1, Entries 1–9)

3.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Aminodiperoxides 3aa, 3da, 3ia, 3ka, 3la, 3kb, 3lb, 3ac–3hc, 3jc–3nc from 1,5-Diketones 1a–n and Corresponding Bishydroperoxides 2a–c

3.5. Synthesis of Aminodiperoxide 3ec Scaled Up to 1.0 g of 1,5-Diketone 1e

- (1R*,7S*)-1,7-Dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cyclohexane], 3aa. White crystals. Mp = 46–48 °C. Rf = 0.41 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 3.63 (br. s, 1H), 2.22–2.13 (m, 1H), 2.04–1.84 (m, 2H), 1.77–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.38 (m, 11H), 1.34 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 108.6, 89.6, 31.9, 31.1, 29.9, 26.8, 25.5, 22.9, 21.9, 16.8. Anal. Calcd for C13H23NO4: C, 60.68; H, 9.01; N, 5.44. Found: C, 60.79; H, 9.13; N, 5.55. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C13H24NO4]+: 258.1700; found: 258.1691.

- Ethyl (1R*,7S*,8S*)-8-butyl-1,7-dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cyclohexane]-8-carboxylate, 3da. Colourless oil. Rf = 0.53 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 4.26–4.14 (m, 1H), 4.13–4.00 (m, 1H), 3.41 (br. s, 1H), 2.52 (td, J = 14.5, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.28–2.06 (m, 2H), 1.88–1.73 (m, 3H), 1.70–1.10 (m, 23H), 0.88 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.5, 109.2, 94.1, 88.9, 60.7, 50.3, 31.2, 30.4, 30.0, 28.4, 26.7, 25.6, 23.2, 23.0, 21.9, 21.3, 20.8, 14.3, 14.1. Anal. Calcd for C20H35NO6: C, 62.31; H, 9.15; N, 3.63. Found: C, 62.48; H, 9.28; N, 3.82. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M +H]+: calculated for [C20H36NO6]+: 386.2537; found: 386.2527.

- Ethyl (1R*,7S*,8R*)-1,7-dimethyl-8-(4-methylbenzyl)-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cyclohexane]-8-carboxylate, 3ia. White crystals. Mp = 95–96 °C. Rf = 0.58 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.05 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 4.38–4.16 (m, 1H), 4.15–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.45 (br. s, 1H), 3.40 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (td, J = 14.4, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.23–2.02 (m, 2H), 1.81 (td, J = 14.4, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 1.69–1.35 (m, 16H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.0, 136.3, 134.1, 129.7, 129.2, 109.2, 94.2, 88.8, 60.8, 51.2, 36.4, 31.2, 30.0, 28.7, 26.7, 25.6, 23.0, 21.9, 21.4, 21.1, 20.6, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C24H35NO6: C, 66.49; H, 8.14; N, 3.23. Found: C, 66.60; H, 8.22; N, 3.31. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C24H36NO6]+: 434.2537; found: 434.2532.

- Ethyl (1R*,7S*,8R*)-8-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1,7-dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cyclohexane]-8-carboxylate, 3ka. White crystals. Mp = 134–135 °C. Rf = 0.50 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.10–7.00 (m, 2H), 6.98–6.88 (m, 2H), 4.29–4.15 (m, 1H), 4.14–4.00 (m, 1H), 3.48 (br. s, 1H), 3.39 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (td, J = 14.3, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.23–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.78 (td, J = 14.3, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.68–1.37 (m, 16H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.7, 161.8 (d, 1JCF = 244.3 Hz), 132.7 (d, 4JCF = 3.4 Hz), 131.2 (d, 3JCF = 7.7 Hz), 115.2 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 109.2, 94.1, 88.8, 61.0, 51.2, 35.9, 31.2, 30.0, 28.7, 26.7, 25.6, 22.9, 21.9, 21.3, 20.5, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C23H32FNO6: C, 63.14; H, 7.37; F, 4.34; N, 3.20. Found: C, 63.28; H, 7.45; F, 4.41; N, 3.30. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C23H33FNO6]+: 438.2286; found: 438.2298.

- Ethyl (1R*,7S*,8R*)-8-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1,7-dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cyclohexane]-8-carboxylate, 3la. White crystals. Mp = 131–132 °C. Rf = 0.37 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.21 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.28–4.15 (m, 1H), 4.13–4.01 (m, 1H), 3.47 (br. s, 1H), 3.39 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 3.02 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 2.44 (td, J = 14.3, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.24–2.08 (m, 2H), 1.76 (td, J = 14.3, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 1.68–1.33 (m, 16H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.8, 135.8, 132.7, 131.2, 128.6, 109.2, 94.1, 88.8, 61.0, 51.2, 36.1, 31.2, 30.0, 28.7, 26.7, 25.6, 22.9, 21.9, 21.3, 20.5, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C23H32ClNO6: C, 60.85; H, 7.11; Cl, 7.81; N, 3.09. Found: C, 61.00; H, 7.28; Cl, 8.02; N, 3.19. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C23H33ClNO6]+: 454.1991; found: 454.1991.

- Ethyl (1R*,7S*,8R*)-8-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1,7-dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cycloheptane]-8-carboxylate, 3kb. White crystals. Mp = 113–115 °C. Rf = 0.51 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.09–7.00 (m, 2H), 6.97–6.87 (m, 2H), 4.26–4.02 (m, 2H), 3.49 (br. s, 1H), 3.38 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (td, J = 14.2, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.34–2.23 (m, 2H), 1.77 (td, J = 14.2, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 1.59–1.38 (m, 18H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.8, 161.9 (d,1JCF = 245.0 Hz), 131.3 (d, 4JCF = 3.4 Hz), 131.2 (d, 3JCF = 7.7 Hz), 115.3 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 114.7, 94.1, 88.8, 61.0, 51.2, 35.9, 35.4, 31.5, 30.5, 30.3, 28.7, 26.6, 23.4, 22.4, 21.3, 20.4, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C24H34FNO6: C, 63.84; H, 7.59; F, 4.21; N, 3.10. Found: C, 63.99; H, 7.65; F, 4.32; N, 3.19. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + K]+: calculated for [C24H34FNKO6]+: 490.2002; found: 490.1989.

- Ethyl (1R*,7S*,8R*)-8-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1,7-dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cycloheptane]-8-carboxylate, 3lb. White crystals. Mp = 149–151 °C. Rf = 0.48 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.21 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 4.28–4.01 (m, 2H), 3.48 (br. s, 1H), 3.39 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 2.42 (td, J = 14.4, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.35–2.24 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.36 (m, 19H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.8, 135.7, 132.7, 131.2, 128.6, 114.7, 94.1, 88.7, 61.0, 51.2, 36.1, 35.4, 31.5, 30.5, 30.3, 28.7, 26.6, 23.4, 22.4, 21.3, 20.5, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C24H34ClNO6: C, 61.60; H, 7.32; Cl, 7.57; N, 2.99. Found: C, 61.71; H, 7.42; Cl, 7.65; N, 3.09. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C24H35ClNO6]+: 468.2147; found: 468.2136.

- (1R*,7S*)-1,7-dimethyl-2,3,5,6-tetraoxa-11-azaspiro[bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane-4,1′-cyclohexane], 3ac. White crystals. Mp = 123–125 °C. Rf = 0.64 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 3.66 (br. s, 1H), 2.97–3.05 (m, 1H), 1.42–2.09 (m, 19H), 1.35 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 110.6, 89.5, 37.7, 34.6, 33.6, 33.3, 32.1, 30.8, 27.4, 27.1, 17.0. Anal. Calcd for C17H27NO4: C, 65.99; H, 8.80; N, 4.53. Found: C, 66.12; H, 8.98; N, 4.65. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C17H28NO4]+: 310.2013; found: 310.2016.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′S*)-1′,7′,8′-trimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3bc. White crystals. Mp = 100–102 °C. Rf = 0.57 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 4.26–3.98 (m, 2H), 3.42 (br. s, 1H), 3.07–2.96 (m, 1H), 2.77–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.06–1.93 (m, 4H), 1.86–1.71 (m, 4H), 1.70–1.51 (m, 8H), 1.47 (s, 3H), 1.40–1.29 (m, 6H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 174.2, 111.1, 93.4, 88.7, 60.8, 46.6, 37.7, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.0, 30.8, 28.6, 27.4, 26.7, 26.5, 21.6, 20.1, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C21H33NO6: C, 63.78; H, 8.41; N, 3.54. Found: C, 63.92; H, 8.52; N, 3.63. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C21H34NO6]+: 396.2381; found: 396.2379.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′S*)-8′-ethyl-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3cc. White crystals. Mp = 131–133 °C. Rf = 0.68 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ:4.30–3.98 (m, 2H). 3.41 (br. s, 1H), 3.10–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.49 (td, J = 14.6, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.11–1.40 (m, 21H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 0.74 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.3, 111.0, 93.8, 88.6, 60.5, 50.7, 37.6, 34.5, 34.4, 33.5, 33.1, 32.9, 30.7, 28.2, 27.3, 26.6, 23.2, 21.1, 19.9, 14.2, 8.6. Anal. Calcd for C22H35NO6: C, 64.52; H, 8.61; N, 3.42. Found: C, 64.61; H, 8.73; N, 3.50. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C22H36NO6]+: 410.2537; found: 410.2528.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′S*)-8′-butyl-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3dc. White crystals. Mp = 107–108 °C. Rf = 0.73 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 4.28–4.13 (m, 1H), 4.11–3.98 (m, 1H), 3.41 (br. s, 1H), 3.11–2.92 (m, 1H), 2.77–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.06– 1.10 (m, 31H), 0.88 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.4, 111.0, 93.8, 88.6, 60.5, 50.3, 37.6, 34.5, 34.4, 33.5, 33.1, 32.9, 30.7, 30.2, 28.4, 27.3, 26.6, 23.1, 21.1, 20.6, 14.2, 14.0. Anal. Calcd for C24H39NO6: C, 65.88; H, 8.98; N, 3.20. Found: C, 65.99; H, 9.11; N, 3.33. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C24H40NO6]+: 438.2850; found: 438.2842.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-(3-ethoxy-3-oxopropyl)-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3ec. White crystals. Mp = 107–109 °C. Rf = 0.37 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 4.00–4.28 (m, 4H), 3.40 (br. s, 1H), 3.07–2.98 (m, 1H), 2.65–2.48 (m, 1H), 2.38–2.25 (m, 1H), 2.18 (td, J = 14.0, 4.6 Hz, 2H), 2.08–1.91 (m, 5H), 1.91–1.45 (m, 15H), 1.35 (s, 3H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.1, 172.7, 111.0, 93.5, 88.5, 60.8, 60.5, 49.8, 37.5, 34.4, 34.4, 33.5, 33.1, 32.9, 30.7, 29.6, 28.2, 27.3, 26.5, 25.6, 21.1, 20.7, 14.19, 14.15. Anal. Calcd for C25H39NO8: C, 62.35; H, 8.16; N, 2.91. Found: C, 62.49; H, 8.30; N, 3.05. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C25H40NO8]+: 482.2748; found: 482.2749.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-allyl-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3fc. White crystals. Mp = 108–109 °C. Rf = 0.48 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 5.62–5.45 (m, 1H), 5.15–4.98 (m, 2H), 4.28–4.00 (m, 2H), 3.42 (br. s, 1H), 3.07–2.98 (m, 1H), 2.83–2.72 (m, 1H), 2.62–2.39 (m, 2H), 2.07–1.93 (m, 4H), 1.91–1.45 (m, 15H), 1.35 (s, 3H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.8, 133.5, 118.3, 111.0, 93.3, 88.5, 60.7, 49.9, 37.5, 35.4, 34.5, 34.4, 33.5, 33.1, 32.9, 30.6, 28.0, 27.3, 26.6, 21.2, 21.0, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C23H35NO6: C, 65.54; H, 8.37; N, 3.32. Found: C, 65.54; H, 8.37; N, 3.32. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C23H36NO6]+: 422.2537; found: 422.2531.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-1′,7′-dimethyl-8′-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3gc. White crystals. Mp = 134–135 °C. Rf = 0.63 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 4.20–4.04 (m, 2H), 3.10 (br. s, 1H), 3.10–2.90 (m, 2H), 2.78–2.66 (m, 1H), 2.59 (td, J = 13.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.07–1.92 (m, 5H), 1.87–1.50 (m, 12H), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 171.9, 111.2, 92.7, 88.6, 80.1, 71.3, 61.2, 49.8, 37.6, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.0, 30.8, 28.4, 27.4, 26.6, 22.1, 21.7, 21.1, 14.3. Anal. Calcd for C23H33NO6: C, 65.85; H, 7.93; N, 3.34. Found: C, 65.99; H, 8.11; N, 3.49. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C23H34NO6]+: 420.2381; found: 420.2378.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-benzyl-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3hc. White crystals. Mp = 163–164 °C. Rf = 0.69 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.34–7.20 (m, 3H), 7.16–7.08 (m, 2H), 4.32–4.00 (m, 2H), 3.49 (br. s, 1H), 3.48 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.17–2.98 (m, 2H), 2.44 (td, J = 14.3, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.10–1.96 (m, 4H), 1.91–1.52 (m, 15H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.1, 137.4, 129.9, 128.4, 126.7, 111.1, 94.0, 88.7, 60.8, 51.3, 37.7, 36.8, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.0, 30.8, 28.8, 27.4, 26.8, 21.3, 20.6, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C27H37NO6: C, 68.77; H, 7.91; N, 2.97. Found: C, 68.88; H, 7.99; N, 3.09. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C27H38NO6]+: 472.2694; found: 472.2674.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-(4-(tert-butyl)benzyl)-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3jc. White crystals. Mp = 135–137 °C. Rf = 0.59 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.24 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 4.29–4.16 (m, 1H), 4.14–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.38 (br. s, 1H), 3.41 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.06–2.96 (m, 2H), 2.44 (td, J = 14.3, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.10–1.52 (m, 19H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 9H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 173.1, 149.4, 134.2, 129.5, 125.3, 111.1, 94.0, 88.7, 60.8, 51.2, 37.7, 36.3, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.0, 31.5, 30.8, 28.8, 27.4, 26.8, 21.4, 20.6, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C31H45NO6: C, 70.56; H, 8.60; N, 2.65. Found: C, 70.71; H, 8.75; N, 2.79. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C31H46NO6]+: 528.3320; found: 528.3316.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3kc. White crystals. Mp = 165–166 °C. Rf = 0.58 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.10–7.00 (m, 2H), 6.98–6.87 (m, 2H), 4.31–4.14 (m, 1H), 4.11–3.96 (m, 1H), 3.51 (br. s, 1H), 3.40 (d, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 3.12–2.93 (m, 2H), 2.41 (td, J = 14.2, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.11–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.8, 161.9 (d, 1JCF = 245.0 Hz), 131.3 (d, 4JCF = 3.4 Hz), 131.2 (d, 3JCF = 7.7 Hz), 115.3 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 111.0, 93.8, 88.5, 60.7, 51.2, 37.5, 35.7, 34.5, 34.4, 33.5, 33.1, 32.9, 30.7, 28.6, 27.3, 26.6, 21.1, 20.3, 14.1. Anal. Calcd for C27H36FNO6: C, 66.24; H, 7.41; F, 3.88; N, 2.86. Found: C, 66.35; H, 7.52; F, 3.99; N, 2.98. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C27H37FNO6]+: 490.2599; found: 490.2585.

- Ethyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3lc. White crystals. Mp = 167–169 °C. Rf = 0.41 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.21 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.30–3.95 (m, 2H), 3.48 (br. s, 1H), 3.41 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H), 3.09–2.92 (m, 2H), 2.42 (td, J = 14.3, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.10–1.50 (m, 19H), 1.46–1.34 (m, 3H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.9, 135.9, 132.6, 131.3, 128.6, 111.1, 93.9, 88.6, 60.9, 51.3, 37.6, 36.0, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.0, 30.8, 28.7, 27.4, 26.7, 21.2, 20.5, 14.2. Anal. Calcd for C27H36ClNO6: C, 64.09; H, 7.17; Cl, 7.01; N, 2.77. Found: C, 64.21; H, 7.30; Cl, 7.19; N, 2.88. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C27H37ClNO6]+: 506.2304; found: 506.2300.

- Allyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-allyl-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3mc. White crystals. Mp = 79–81 °C. Rf = 0.66 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 5.97–5.80 (m, 1H), 5.64–5.44 (m, 1H), 5.37–5.28 (m, 1H), 5.23–5.17 (m, 1H), 5.14–5.00 (m, 2H), 4.66 (dd, J = 13.5, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (dd, J = 13.5, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (br. s, 1H), 3.07–2.97 (m, 1H), 2.79 (dd, J = 14.0, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.64–2.42 (m, 2H), 2.07–1.45 (m, 16H), 1.50 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.6, 133.4, 132.4, 118.6, 117.8, 111.1, 93.5, 88.7, 65.4, 50.3, 37.7, 35.6, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.0, 30.8, 28.1, 27.4, 26.7, 21.3, 21.1. Anal. Calcd for C24H35NO6: C, 66.49; H, 8.14; N, 3.23. Found: C, 66.61; H, 8.22; N, 3.35. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C24H36NO6]+: 434.2537; found: 434.2529.

- Benzyl (1S*,1′R*,2R*,5R*,7′S*,8′R*)-8′-allyl-1′,7′-dimethyl-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetraoxa-11′-azaspiro[adamantane-2,4′-bicyclo [5.3.1]undecane]-8′-carboxylate, 3nc. White crystals. Mp = 148–149 °C. Rf = 0.58 (TLC, PE:EA, 10:1). 1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 7.40–7.28 (m, 5H), 5.61–5.39 (m, 1H), 5.25–4.95 (m, 4H), 3.44 (br. s, 1H), 3.09–2.94 (m, 1H), 2.81 (dd, J = 14.1, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.45–2.65 (m, 2H), 2.07–1.93 (m, 4H), 1.89–1.44 (m, 15H), 1.44 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75.48 MHz, CDCl3), δ: 172.9, 136.3, 133.4, 128.5, 128.0, 127.9, 118.7, 111.1, 93.6, 88.7, 66.7, 50.3, 37.7, 35.7, 34.6, 34.5, 33.6, 33.2, 33.1, 30.8, 28.1, 27.4, 26.7, 21.3, 21.2. Anal. Calcd for C28H37NO6: C, 69.54; H, 7.71; N, 2.90. Found: C, 69.70; H, 7.82; N, 2.99. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M + H]+: calculated for [C28H38NO6]+: 484.2694; found: 484.2683.

3.6. Evaluation of Cytotoxic Activity and Selectivity

3.6.1. Cell Culture

3.6.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

3.6.3. Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA)

3.6.4. Statistics

3.7. Bioassay of Fungicidal Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

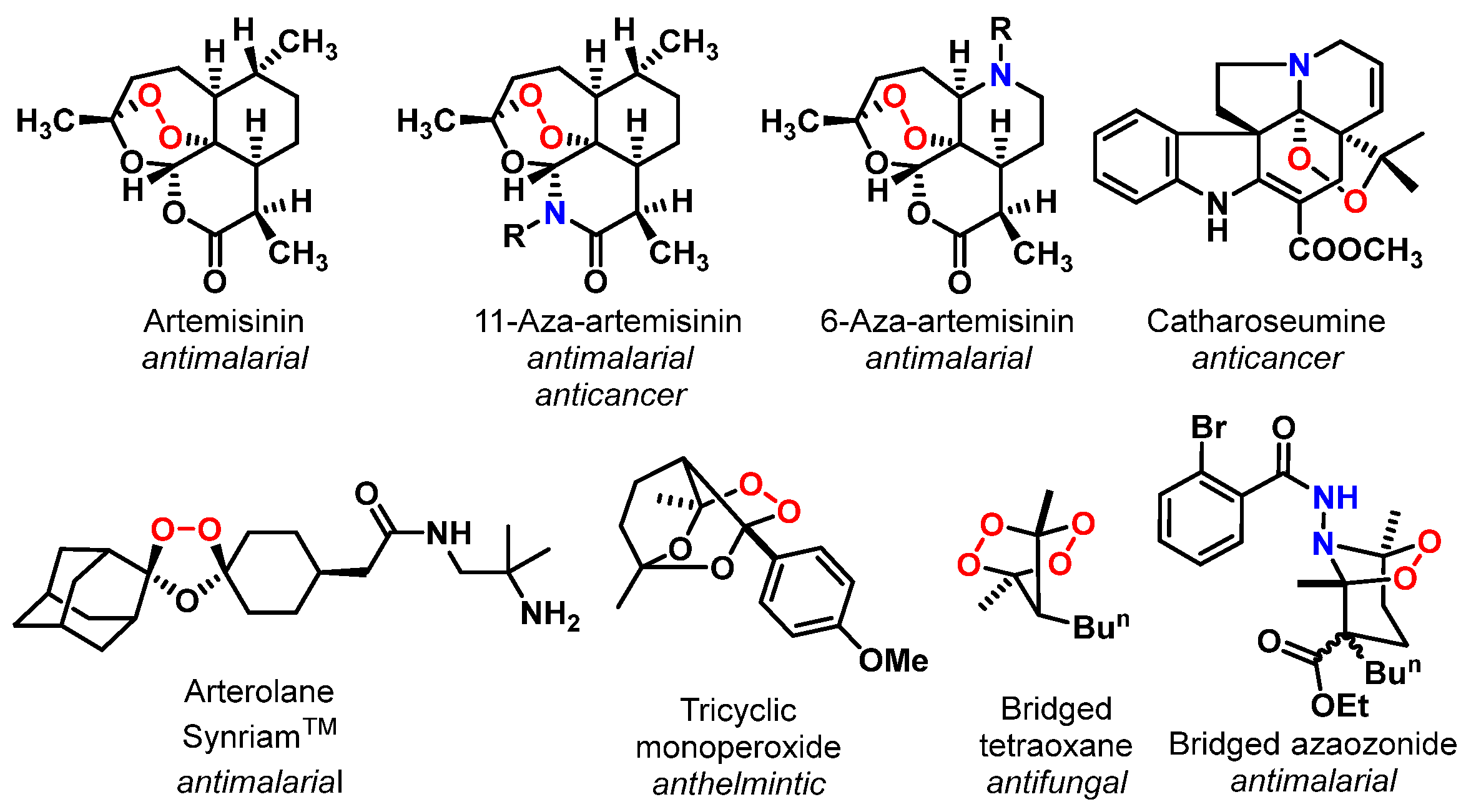

- Giannangelo, C.; Fowkes, F.J.I.; Simpson, J.A.; Charman, S.A.; Creek, D.J. Ozonide Antimalarial Activity in the Context of Artemisinin-Resistant Malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnatak, M.; Hassam, M.; Singh, A.S.; Yadav, D.K.; Singh, C.; Puri, S.K.; Verma, V.P. Novel hydrazone derivatives of N-amino-11-azaartemisinin with high order of antimalarial activity against multidrug-resistant Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis in Swiss mice via intramuscular route. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 58, 128522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biendl, S.; Häberli, C.; Chen, G.; Wang, W.; Zhong, L.; Saunders, J.; Pham, T.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Charman, S.A.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Antischistosomal Activity Profiling and Pharmacokinetics of Ozonide Carboxylic Acids. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, L.I.L.; Pomel, S.; Cojean, S.; Amado, P.S.M.; Loiseau, P.M.; Cristiano, M.L.S. Synthesis and Antileishmanial Activity of 1,2,4,5-Tetraoxanes against Leishmania donovani. Molecules 2020, 25, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coghi, P.; Yaremenko, I.A.; Prommana, P.; Nasim, A.A.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Chen, R.; Radulov, P.S.; Uthaipibull, C.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Wong, V.K.W. N-Substituted Bridged Azaozonides as Promising Antimalarial Agents. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e2500181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, R.P.; Carroll, W.L.; Woerpel, K.A. Five-Membered Ring Peroxide Selectively Initiates Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sun, Z.; Kong, F.; Xiao, J. Artemisinin-derived hybrids and their anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Sharma, V.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Gaikwad, A.N.; Sinha, S.K.; Puri, S.K.; Sharon, A.; Maulik, P.R.; Chaturvedi, V. Stable aricyclic antitubercular ozonides derived from Artemisinin. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4948–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.-W.; Lei, H.-S.; Fan, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, J.; Peng, X.-M.; Xu, X.-R.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C.-H.; Zou, Y.-Y.; et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of dihydroartemisinin–fluoroquinolone conjugates as a novel type of potential antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Radulov, P.S.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Demina, A.A.; Fomenkov, D.I.; Barsukov, D.V.; Subbotina, I.R.; Fleury, F.; Terent’ev, A.O. Catalyst Development for the Synthesis of Ozonides and Tetraoxanes Under Heterogeneous Conditions: Disclosure of an Unprecedented Class of Fungicides for Agricultural Application. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 4734–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.W.; Marousek, G.; Auerochs, S.; Stamminger, T.; Milbradt, J.; Marschall, M. The unique antiviral activity of artesunate is broadly effective against human cytomegaloviruses including therapy-resistant mutants. Antivir. Res. 2011, 92, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, C.; Frohlich, T.; Gruber, L.; Hutterer, C.; Marschall, M.; Voigtlander, C.; Friedrich, O.; Kappes, B.; Efferth, T.; Tsogoeva, S.B. Highly potent artemisinin-derived dimers and trimers: Synthesis and evaluation of their antimalarial, antileukemia and antiviral activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 5452–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T. Beyond malaria: The inhibition of viruses by artemisinin-type compounds. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gilmore, K.; Ramirez, S.; Settels, E.; Gammeltoft, K.A.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Feng, S.; Offersgaard, A.; Trimpert, J.; et al. In vitro efficacy of artemisinin-based treatments against SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Miller, H.; Knox, K.; Kundu, M.; Henrickson, K.J.; Arav-Boger, R. Inhibition of Human Coronaviruses by Antimalarial Peroxides. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrié, L. Chapter Two—Advances in the synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes and 1,2-dioxanes. In Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry; Scriven, E.F.V., Ramsden, C.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 135, pp. 57–146. [Google Scholar]

- Champciaux, B.; Jamey, N.; Figadère, B.; Ferrié, L. Peroxycarbenium-Mediated Asymmetric Synthesis of 1,2-Dioxanes and 1,2-Dioxolanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 3353–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesbaum, K.; Liu, X.; Kassiaris, A.; Scherer, M. Ozonolyses of O-Alkylated Ketoximes in the Presence of Carbonyl Groups: A Facile Access to Ozonides. Liebigs Ann. 1997, 1997, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimova, T.I.; Soldatkina, O.A. Method of Producing 1,2,4-Trioxolanes. RU Patent 2578609, 27 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

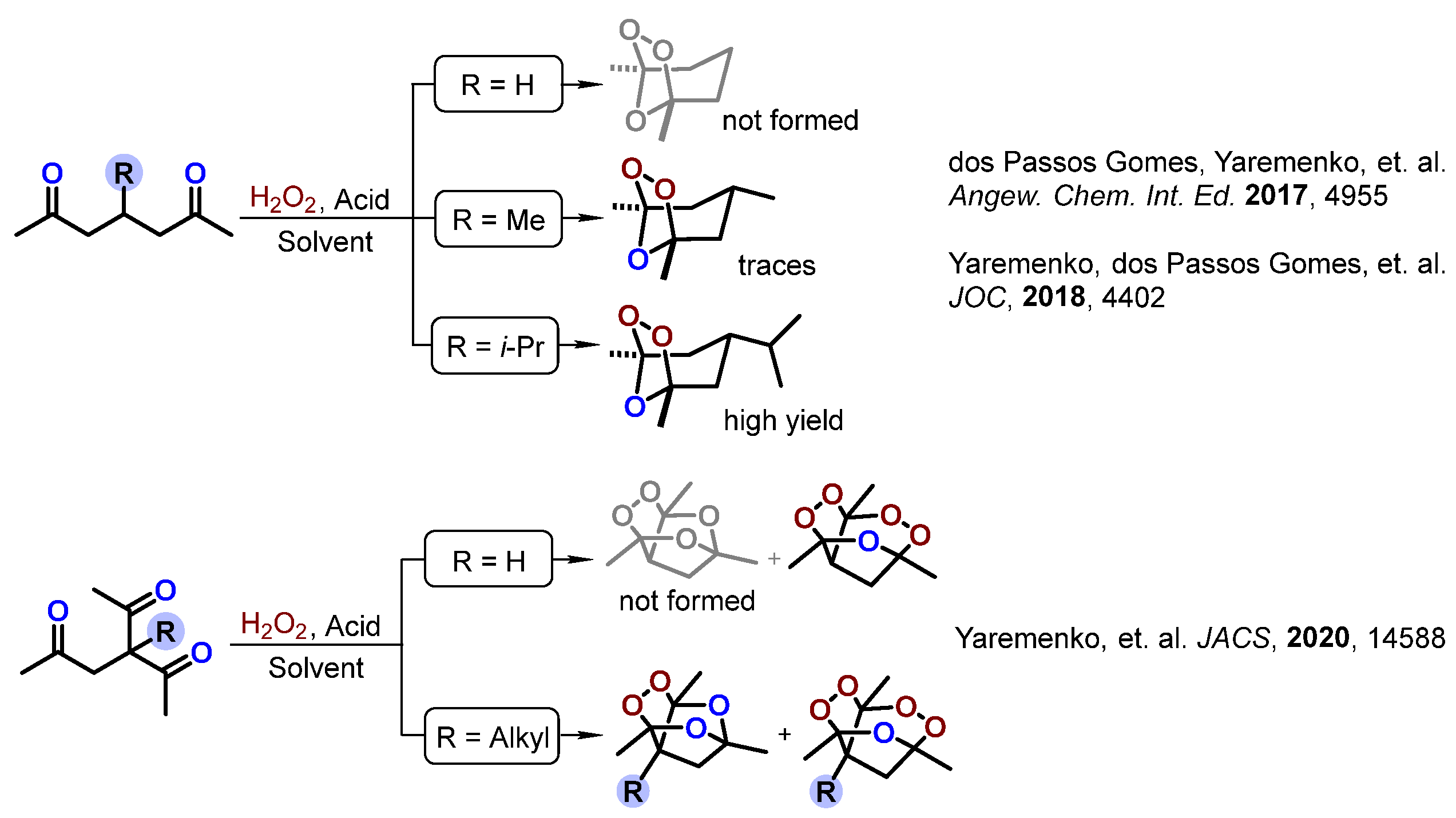

- dos Passos Gomes, G.; Yaremenko, I.A.; Radulov, P.S.; Novikov, R.A.; Chernyshev, V.V.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Nikishin, G.I.; Alabugin, I.V.; Terent’ev, A.O. Stereoelectronic Control in the Ozone-Free Synthesis of Ozonides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4955–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Gomes, G.D.P.; Radulov, P.S.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Vilikotskiy, A.E.; Vil, V.A.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Nikishin, G.I.; Alabugin, I.V.; Terent’ev, A.O. Ozone-Free Synthesis of Ozonides: Assembling Bicyclic Structures from 1,5-Diketones and Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 4402–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorai, P.; Dussault, P.H. Broadly Applicable Synthesis of 1,2,4,5-Tetraoxanes. Org. Lett. 2008, 11, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, P.S.M.; Frija, L.M.T.; Coelho, J.A.S.; O’Neill, P.M.; Cristiano, M.L.S. Synthesis of Non-symmetrical Dispiro-1,2,4,5-Tetraoxanes and Dispiro-1,2,4-Trioxanes Catalyzed by Silica Sulfuric Acid. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 10608–10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonepally, K.R.; Hiruma, T.; Mizoguchi, H.; Ochiai, K.; Suzuki, S.; Oikawa, H.; Ishiyama, A.; Hokari, R.; Iwatsuki, M.; Otoguro, K.; et al. Design and De Novo Synthesis of 6-Aza-artemisinins. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4667–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonepally, K.R.; Takahashi, N.; Matsuoka, N.; Koi, H.; Mizoguchi, H.; Hiruma, T.; Ochiai, K.; Suzuki, S.; Yamagishi, Y.; Oikawa, H.; et al. Rapid and Systematic Exploration of Chemical Space Relevant to Artemisinins: Anti-malarial Activities of Skeletally Diversified Tetracyclic Peroxides and 6-Aza-artemisinins. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 9694–9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, K.; Hassam, M.; Singh, C.; Puri, S.K.; Jat, J.L.; Prakash Verma, V. Novel ether derivatives of 11-azaartemisinins with high order antimalarial activity against multidrug-resistant Plasmodium yoelii in Swiss mice. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 103, 129700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushigoe, Y.; Satake, S.; Masuyama, A.; Nojima, M.; McCullough, K.J. Synthesis of 1,2,4-dioxazolidine derivatives by the ozonolysis of indenes in the presence of primary amines. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1997, 13, 1939–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K.J.; Mori, M.; Tabuchi, T.; Yamakoshi, H.; Kusabayashi, S.; Nojima, M. [3 + 2] Cycloadditions of carbonyl oxides to imines: An alternative approach to the synthesis of 1,2,4-dioxazolidines. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1995, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesbaum, K.; Liu, X.; Henke, H. N-Methoxy-1,2,4-Dioxazolidines by Ozonolysis Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 1086–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-R.; Eun Lee, S.; Sung Huh, T. Syntheses of O-Methylated-1,2,4-dioxazolidines by Ozonolyses of O-Methylated Dioximes. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 1039–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Kazakova, O.B.; Kazakov, D.V.; Yamansarov, E.Y.; Medvedeva, N.I.; Tolstikov, G.A.; Suponitsky, K.Y.; Arkhipov, D.E. Synthesis of triterpenoid-based 1,2,4-trioxolanes and 1,2,4-dioxazolidines by ozonolysis of allobetulin derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 976–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootstra, J.; Mehara, J.; Veenstra, M.J.; Le Cacheux, M.; Oddone, L.E.; Pereverzev, A.Y.; Roithová, J.; Harutyunyan, S.R. Unveiling New Reactivities in Complex Mixtures: Synthesis of Tricyclic Pyridinium Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 5132–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmudiyarova, N.N.; Khatmullina, G.M.; Rakhimov, R.S.; Meshcheryakova, E.S.; Ibragimov, A.G.; Dzhemilev, U.M. The First Example of Catalytic Synthesis of N-Aryl-Substituted Tetraoxazaspiroalkanes. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 3277–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmudiyarova, N.N.; Ishmukhametova, I.R.; Dzhemileva, L.U.; Tyumkina, T.V.; D’yakonov, V.A.; Ibragimov, A.G.; Dzhemilev, U.M. Synthesis and anticancer activity novel dimeric azatriperoxides. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18923–18929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, E.G.E. Reactions of organic peroxides. Part XI. Amino-peroxides from cyclic ketones. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1969, 20, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskii, V.A.; Alekseev, V.I.; Tilichenko, M.N. Aminoperoxidation of 2,2′-methylenedicyclohexanone. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1972, 8, 1551–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumakov, S.A.; Kaminskii, V.A.; Tilichenko, M.N. Hydroacridines and Related-Compounds. 22. Synthesis of Compounds with 2,6-Epidioxipiperidine Structures. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1985, 21, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

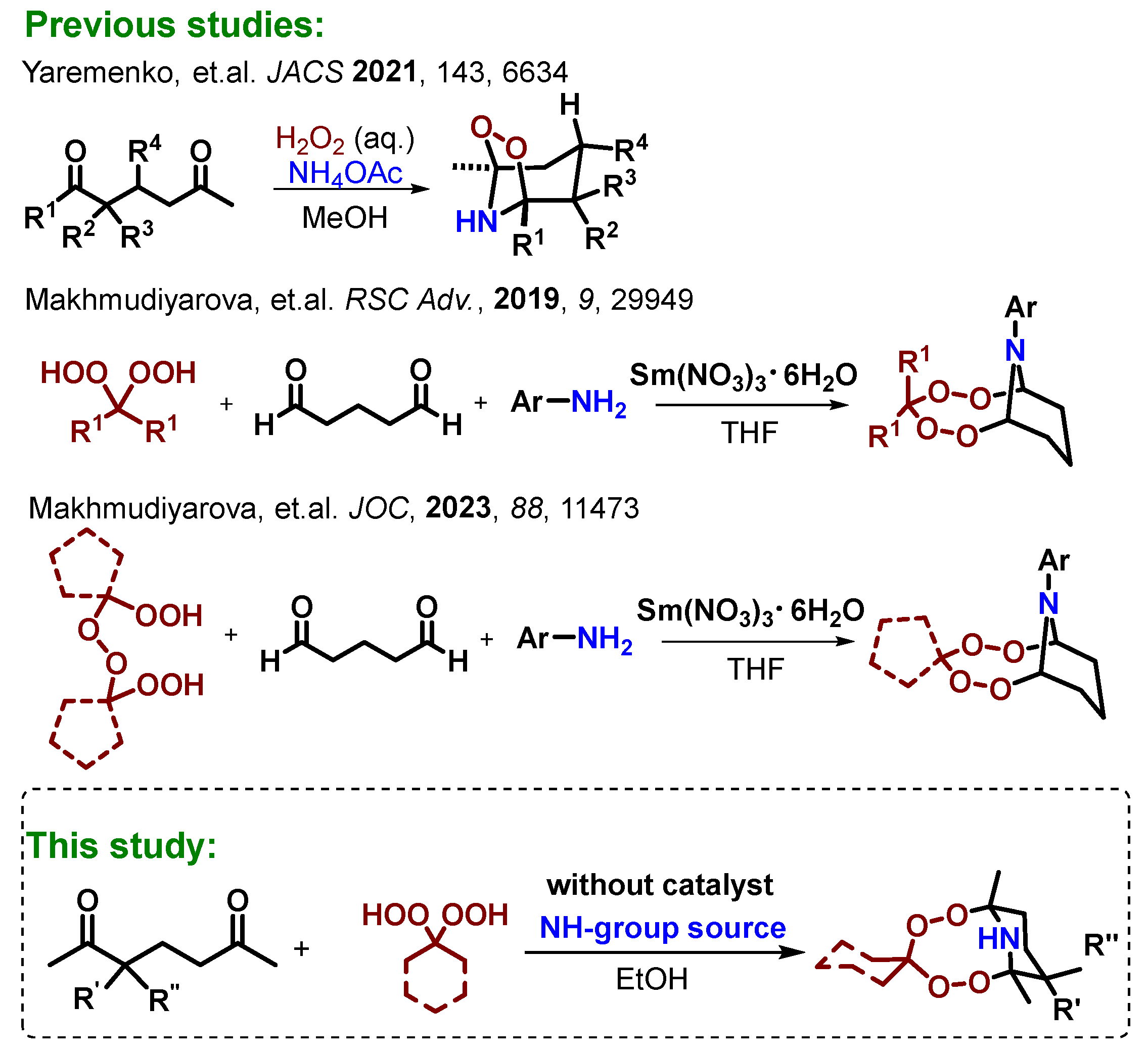

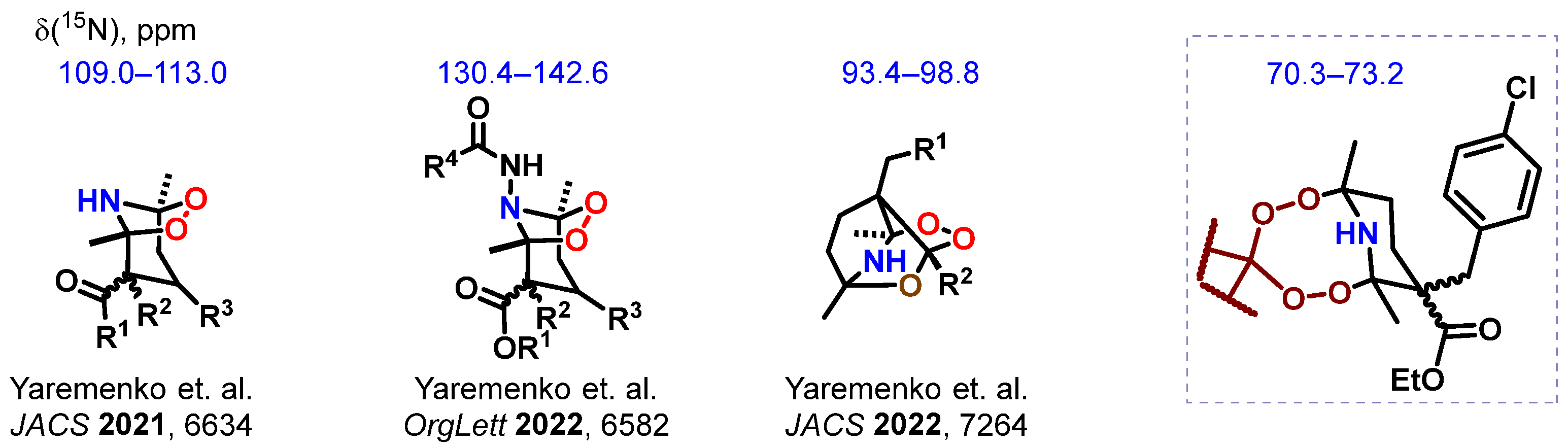

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Radulov, P.S.; Novikov, R.A.; Medvedev, M.G.; Krivoshchapov, N.V.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Alabugin, I.V.; Terent’ev, A.O. Marriage of Peroxides and Nitrogen Heterocycles: Selective Three-Component Assembly, Peroxide-Preserving Rearrangement, and Stereoelectronic Source of Unusual Stability of Bridged Azaozonides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 6634–6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Radulov, P.S.; Novikov, R.A.; Medvedev, M.G.; Krivoshchapov, N.V.; Alabugin, I.V.; Terent’ev, A.O. Cascade Assembly of Bridged N-Substituted Azaozonides: The Counterintuitive Role of Nitrogen Source Nucleophilicity. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 6582–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Radulov, P.S.; Novikov, R.A.; Medvedev, M.G.; Krivoshchapov, N.V.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Alabugin, I.V.; Terent′ev, A.O. Inverse α-Effect as the Ariadne’s Thread on the Way to Tricyclic Aminoperoxides: Avoiding Thermodynamic Traps in the Labyrinth of Possibilities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7264–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmudiyarova, N.N.; Shangaraev, K.R.; Dzhemileva, L.U.; Tyumkina, T.V.; Mescheryakova, E.S.; D’Yakonov, V.A.; Ibragimov, A.G.; Dzhemilev, U.M. New synthesis of tetraoxaspirododecane-diamines and tetraoxazaspirobicycloalkanes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 29949–29958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmudiyarova, N.N.; Ishmukhametova, I.R.; Tyumkina, T.V.; Mescheryakova, E.S.; Dzhemileva, L.; D’yakonov, V.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Dzhemilev, U.M. Multicomponent Assembly of Bicyclic Aza-peroxides Catalyzed by Samarium Complexes and Their Cytotoxic Activity. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 11473–11485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabugin, I.V.; Kuhn, L.; Medvedev, M.G.; Krivoshchapov, N.V.; Vil’, V.A.; Yaremenko, I.A.; Mehaffy, P.; Yarie, M.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Zolfigol, M.A. Stereoelectronic power of oxygen in control of chemical reactivity: The anomeric effect is not alone. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 10253–10345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremenko, I.A.; Radulov, P.S.; Medvedev, M.G.; Krivoshchapov, N.V.; Belyakova, Y.Y.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Ilovaisky, A.I.; Terent′ev, A.O.; Alabugin, I.V. How to Build Rigid Oxygen-Rich Tricyclic Heterocycles from Triketones and Hydrogen Peroxide: Control of Dynamic Covalent Chemistry with Inverse α-Effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14588–14607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodley, C.M.; Amado, P.S.M.; Cristiano, M.L.S.; O’Neill, P.M. Artemisinin inspired synthetic endoperoxide drug candidates: Design, synthesis, and mechanism of action studies. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 3062–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abassi, Y.A.; Xi, B.; Zhang, W.; Ye, P.; Kirstein, S.L.; Gaylord, M.R.; Feinstein, S.C.; Wang, X.; Xu, X. Kinetic Cell-Based Morphological Screening: Prediction of Mechanism of Compound Action and Off-Target Effects. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Ochocka, J.R. Real-time cell analysis system in cytotoxicity applications: Usefulness and comparison with tetrazolium salt assays. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, K.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Strulovici, B.; Zheng, W. Application of Real-Time Cell Electronic Sensing (RT-CES) Technology to Cell-Based Assays. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2004, 2, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulukan, H.; Swaan, P.W. Camptothecins. Drugs 2002, 62, 2039–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terent’ev, A.O.; Platonov, M.M.; Tursina, A.I.; Chernyshev, V.V.; Nikishin, G.I. Synthesis of Cyclic Peroxides Containing the Si-gem-bisperoxide Fragment. 1,2,4,5,7,8-Hexaoxa-3-silonanes as a New Class of Peroxides. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 3169–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.J. New technology for investigating trophoblast function. Placenta 2010, 31, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIITEKhIM. Metodicheskie Rekomendatsii po Opredeleniyu Fungitsidnoi Aktivnosti Novykh Soedinenii [Guidelines for Determination of Fungicidal Activity of New Compounds]; NIITEKhIM: Cherkassy, USSR, 1984; p. 32. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- CrysAlisPro, Version 1.171.41.106a; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction: England, UK, 2021.

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Cryst. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||

| Entry | Mol of 2a/ 1 mol of 1a | NH-Group Source (eq. vs. 1l) | Solvent (mL) | Time, h | Temperature | Isolated Yield of 3la, % |

| 1 [b] | 1.5 | NH3(aq) (5 eq.) | MeOH (2 mL) | 1 | 20–25 °C | 38 |

| 2 [b] | 1.5 | NH3(MeOH) (5 eq.) | MeOH (2 mL) | 1 | 20–25 °C | 31 |

| 3 [b] | 1.5 | NH4OAc (5 eq.) | MeOH (3 mL) | 1 | 20–25 °C | 80 |

| 4 [b] | 1.5 | NH4OAc (5 eq.) | THF (3 mL) | 4 | 20–25 °C | 72 |

| 5 [c] | 1.5 | NH4OAc (3 eq.) | EtOH (3 mL) | 1 | 20–25 °C | 51 |

| 6 [c] | 1.5 | NH4OAc (3 eq.) | EtOH (3 mL) | 2 | 20–25 °C | 71 |

| 7 [c] | 1.5 | NH4OAc (3 eq.) | EtOH (3 mL) | 24 | 20–25 °C | 77 |

| 8 [c] | 1.5 | NH4OAc (3 eq.) | EtOH (3 mL) | 24 | 24 h at 20–25 °C then kept at −22 °C overnight [d] | 88 |

| 9 [c] | 1.5 | HCOONH4 (3 eq.) | EtOH (3 mL) | 24 | 24 h at 20–25 °C then kept at −22 °C overnight [d] | 67 |

| Compd | Jurkat Cells CC50 [µM] ± SD | SI [b] | K562 Cells CC50 [µM] ± SD | SI [c] | A549 Cells CC50 [µM] ± SD | SI [d] | HEK293 Cells CC50 [µM] ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3da | 26.3 ± 3.3 | 17.17 | 33.2 ± 2.8 | 13.61 | 45.0 ± 3.6 | 10.04 | 452.2 ± 13.4 |

| 3ia | 41.9 ± 2.9 | 7.53 | 58.7 ± 4.9 | 5.37 | 87.7 ± 6.2 | 3.59 | 315.2 ± 12.8 |

| 3ka | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 10.42 | 34.2 ± 2.8 | 3.62 | 65.8 ± 5.5 | 1.88 | 123.5 ± 10.5 |

| 3la | 40.7 ± 3.2 | 5.79 | 43.6 ± 4.1 | 5.41 | 56.8 ± 5.2 | 4.15 | 235.9 ± 11.3 |

| 3kb | 29.8 ± 1.9 | 10.76 | 48.4 ± 3.9 | 6.62 | 82.1 ± 7.7 | 3.9 | 320.3 ± 25.3 |

| 3lb | 29.2 ± 1.9 | 14.78 | 47.7 ± 4.8 | 9.05 | 67.2 ± 5.9 | 6.43 | 432.0 ± 15.8 |

| 3bc | 96.9 ± 7.2 | 10.12 | 150.2 ± 10.8 | 6.53 | 176.5 ± 15.7 | 5.56 | 980.5 ± 30.5 |

| 3cc | 22.7 ± 3.9 | 38.54 | 47.6 ± 2.8 | 18.37 | 98.2 ± 7.1 | 8.92 | 875.3 ± 18.9 |

| 3dc | 64.9 ± 5.8 | 13.61 | 78.3 ± 7.1 | 11.24 | 95.0 ± 10.2 | 9.26 | 880.0 ± 25.4 |

| 3ec | 12.9 ± 1.4 | 67.09 | 19.6 ± 2.5 | 44.28 | 48.2 ± 3.7 | 17.98 | 866.1 ± 17.9 |

| 3fc | 13.2 ± 1.1 | 43.86 | 26.1 ± 1.9 | 22.17 | 57.9 ± 4.3 | 10.01 | 579.0 ± 27.2 |

| 3gc | 100.8 ± 9.5 | 9.8 | 154.2 ± 11.3 | 6.41 | 145.4 ± 12.2 | 6.8 | 987.9 ± 28.1 |

| 3hc | 14.6 ± 0.9 | 53.58 | 28.7 ± 1.9 | 27.34 | 62.5 ± 2.3 | 12.54 | 784.4 ± 11.5 |

| 3jc | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 49.27 | 26.0 ± 1.8 | 26.9 | 76.8 ± 8.9 | 9.1 | 698.1 ± 18.9 |

| 3kc | 58.3 ± 4.9 | 13.06 | 98.3 ± 3.8 | 7.74 | 90.0 ± 7.6 | 8.46 | 761.1 ± 18.4 |

| 3lc | 60.5 ± 5.1 | 7.49 | 77.4 ± 6.4 | 5.85 | 99.5 ± 8.2 | 4.55 | 453.3 ± 28.1 |

| 3mc | 17.1 ± 1.7 | 46.38 | 31.3 ± 2.5 | 25.32 | 70.0 ± 5.5 | 11.31 | 791.3 ± 15.3 |

| 3nc | 15.6 ± 2.1 | 54.76 | 34.4 ± 2.3 | 24.75 | 73.2 ± 6.4 | 11.65 | 852.6 ± 18.3 |

| Artemisinin | 83.7 ± 9.4 | 4.78 | 80.4 ± 6.6 | 4.97 | 95.6 ± 8.2 | 4.18 | 399.7 ± 25.4 |

| Camptothecin | 576.7 ± 44.2 | 1.19 | 569.9 ± 40.6 | 1.2 | 499.7 ± 38.9 | 1.37 | 685.8 ± 50.2 |

| Run | Cmpd | Mycelium Growth Inhibition (I), % (C = 30 mg/L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V.i. | R.s. | F.o. | F.m. | B.s. | S.s. | ||

| 1 | 3da | 30 | 35 | 9 | 25 | 30 | 11 |

| 2 | 3ia | 40 | 44 | 9 | 31 | 51 | 18 |

| 3 | 3ka | 22 | 21 | 6 | 20 | 44 | 13 |

| 4 | 3la | 26 | 28 | 15 | 18 | 52 | 16 |

| 5 | 3kb | 26 | 16 | 6 | 25 | 48 | 17 |

| 6 | 3lb | 16 | 35 | 9 | 21 | 48 | 14 |

| 7 | 3dc | 30 | 35 | 9 | 22 | 44 | 13 |

| 8 | 3gc | 18 | 41 | 17 | 33 | 51 | 18 |

| 9 | 3kc | 24 | 16 | 0 | 23 | 34 | 10 |

| 10 | 3lc | 14 | 15 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 7 |

| 11 | Triadimefon | 41 | 43 | 77 | 87 | 44 | 61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belyakova, Y.Y.; Tsykunova, V.E.; Radulov, P.S.; Dzhemileva, L.U.; Novikov, R.A.; Ilovaisky, A.I.; Yaremenko, I.A.; Terent’ev, A.O. One-Pot Synthesis of Aminodiperoxides from 1,5-Diketones, Geminal Bishydroperoxides and Ammonium Acetate. Molecules 2025, 30, 4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244703

Belyakova YY, Tsykunova VE, Radulov PS, Dzhemileva LU, Novikov RA, Ilovaisky AI, Yaremenko IA, Terent’ev AO. One-Pot Synthesis of Aminodiperoxides from 1,5-Diketones, Geminal Bishydroperoxides and Ammonium Acetate. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244703

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelyakova, Yulia Yu., Viktoria E. Tsykunova, Peter S. Radulov, Lilya U. Dzhemileva, Roman A. Novikov, Alexey I. Ilovaisky, Ivan A. Yaremenko, and Alexander O. Terent’ev. 2025. "One-Pot Synthesis of Aminodiperoxides from 1,5-Diketones, Geminal Bishydroperoxides and Ammonium Acetate" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244703

APA StyleBelyakova, Y. Y., Tsykunova, V. E., Radulov, P. S., Dzhemileva, L. U., Novikov, R. A., Ilovaisky, A. I., Yaremenko, I. A., & Terent’ev, A. O. (2025). One-Pot Synthesis of Aminodiperoxides from 1,5-Diketones, Geminal Bishydroperoxides and Ammonium Acetate. Molecules, 30(24), 4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244703